Abstract

Growth plasticity is a key mechanism by which plants adapt to the ever‐changing environmental conditions. Since growth is a high‐energy‐demanding and irreversible process, it is expected to be regulated by the integration of endogenous energy status as well as environmental conditions. Here, we show that trehalose‐6‐phosphate (T6P) functions as a sugar signaling molecule that coordinates thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth with endogenous sugar availability. We found that the loss of T6P SYNTHASE 1 (TPS1) in Arabidopsis thaliana impaired high‐temperature‐mediated hypocotyl growth. Consistently, the activity of PIF4, a transcription factor that positively regulates hypocotyl growth, was compromised in the tps1 mutant. We further show that, in the tps1 mutant, a sugar signaling kinase KIN10 directly phosphorylates and destabilizes PIF4. T6P inhibits KIN10 activity in a GRIK‐dependent manner, allowing PIF4 to promote hypocotyl growth at high temperatures. Together, our results demonstrate that T6P determines thermoresponsive growth through the KIN10‐PIF4 signaling module. Such regulation of PIF4 by T6P integrates the temperature‐signaling pathway with the endogenous sugar status, thus optimizing plant growth response to environmental stresses.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, PIF4, thermomorphogenesis, TPS1, trehalose‐6‐phosphate

Subject Categories: Development & Differentiation, Metabolism, Plant Biology

Introduction

Plants use the energy of light to fix carbon dioxide into high‐energy carbon molecules, sugars, via photosynthesis. In plant cells, the photosynthesized sugars are used to generate energy through respiration and as metabolic intermediates for building up biomass. Sugars also function as signaling molecules to regulate gene expression and physiological responses 1. Thus, sugars are needed for optimal growth and development of plants. An imbalance between growth and endogenous sugar availability causes sugar starvation, which suppresses growth and triggers autophagy and senescence 2. Moreover, prolonged sugar starvation leads to plant death. To prevent such energy stresses associated with sugar depletion, plants regulate their growth by the coordinated integration of an endogenous sugar‐sensing pathway and a growth‐regulation signaling pathway.

One of the main traits involved in plant adaptation to surrounding environmental conditions is growth and development plasticity. To adapt to an elevation in ambient temperatures, Arabidopsis seedlings promote elongation of hypocotyls and petioles, hyponastic leaf growth, and reduce leaf thickness 3, 4. These high‐temperature‐induced morphological changes are collectively called thermomorphogenesis 4. Thermomorphogenesis is considered to enhance leaf cooling capacity by improving transpiration efficiency, thereby increasing survival under heat stress 5.

A bHLH transcription factor PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) is a key positive regulator of thermomorphogenesis 6. PIF4 gene expression is transcriptionally activated in response to increased ambient temperatures 6, 7. PIF4 directly binds and activates growth‐promoting hormone auxin and brassinosteroid biosynthetic genes and other genes that are responsible for the cell elongation at high ambient temperatures 8, 9, 10, 11. The resulting PIF4‐mediated transcriptional reprogramming induces thermomorphogenesis including elongated hypocotyl growth. In addition to the high temperatures, other environmental factors also can be integrated onto PIF4 activity and affect thermomorphogenesis. For instance, it was reported that a red/far‐red light receptor phyB directly interacts with PIF4 and induces the phosphorylation of PIF4 in a red light‐dependent manner 12, 13. Phosphorylated PIF4 is then poly‐ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded through 26S proteasome 13. The interaction with the light‐activated phyB also prevents PIF4 from binding to the promoters of its target genes 14. Recently, it was shown that the amount of active phyB is decreased at high temperatures 15, 16, which may result in increased PIF4 activity, thereby triggering thermomorphogenesis. In addition, a blue light receptor CRY1 directly interacts with PIF4 under blue light 17. The interaction with CRY1 prevents PIF4 from binding to its target promoters 17. As a result, the high‐temperature‐dependent hypocotyl growth is suppressed under blue light. UV‐B light perceived by UVR8 receptor also attenuates the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth by reducing PIF4 abundance and activity 18.

Thermomorphogenesis is also dependent on endogenous factors. Two classes of plant hormones, brassinosteroids (BRs) and gibberellic acids (GAs), are necessary for PIF4 activity and thus for thermomorphogenesis. In the BR signaling pathway, a GSK3‐like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes PIF4 protein 19. The BR‐activated transcription factors BZR1 and BES1 heterodimerize with PIF4, activating the expression of genes involved in plant growth 8, 9. In addition, it was recently shown that BZR1 directly activates PIF4 transcription 20. BRs are required for thermomorphogenesis to inhibit BIN2 and to activate BZR1. It was shown that the nuclear localization of BZR1 is increased at high temperatures 20; this finding implicates that BR signaling upstream of BZR1 is potentiated at elevated temperatures. In the GA‐signaling pathway, the negative regulator DELLAs inhibit PIF4 binding to the target gene promoters, thereby suppressing thermomorphogenesis 21, 22, 23. GA may revert the DELLAs‐mediated repression of PIF4 activity by inducing the degradation of DELLAs 22.

The regulation of PIF4 activity by the integration of multiple environmental and endogenous signaling pathways ensures the optimal growth response to environmental changes. Thermomorphogenesis, including the promotion of hypocotyl/petiole growth, is an energy‐demanding process that needs to be regulated by endogenous sugar availability as well as by ambient temperatures to prevent sugar depletion. However, how thermomorphogenesis is regulated by the sugar signaling pathway has not been studied yet.

In the sugar signaling pathway, trehalose‐6‐phosphate (T6P), an intermediate of trehalose biosynthesis, acts as a signaling molecule 24. In this study, we examined whether T6P functions as a signaling molecule that coordinately regulates thermomorphogenesis with sugar availability. We found that T6P is required for the high‐temperature promotion of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Thermoresponsive growth in a T6P‐deficient mutant was restored by the inhibition of the evolutionarily conserved SNF1‐related protein kinase 1 (SnRK1) KIN10. We further found that KIN10 phosphorylates and destabilizes PIF4 through 26S proteasome‐mediated degradation. Therefore, our results provide evidence of a new signaling module, T6P‐KIN10‐PIF4, by which endogenous sugar availability is integrated into the regulation of thermoresponsive growth.

Results

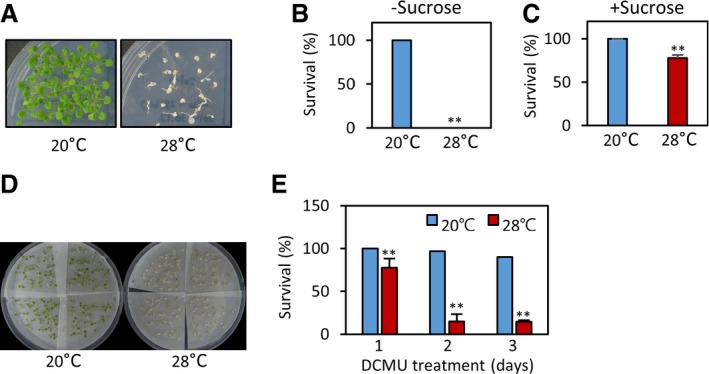

Plants are more sensitive to sugar starvation at high temperatures

To examine whether the sensitivity to sugar starvation is dependent on ambient temperatures, we determined the survival rates of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings subjected to sugar starvation at different temperatures (20 and 28°C). To induce sugar starvation, 1‐week‐old light‐grown seedlings were shifted to darkness for 7 days and then allowed to recover under light for another 7 days. While seedlings were found to be tolerant to the darkness‐induced sugar starvation at 20°C, most seedlings did not recover after darkness treatment at 28°C (Fig EV1A and B). Exogenously supplied sucrose dramatically increased the survival rates of the seedlings (Fig EV1C), suggesting that sugar starvation is responsible for darkness‐induced damage. To further confirm this observation, we induced sugar starvation by treating seedlings with 3‐(3,4‐dichlorophenyl)‐1,1‐dimethylurea (DCMU), which inhibits photosynthesis by blocking photosystem II (PSII) electron transport. In accordance with the above‐mentioned observation, seedlings were more sensitive to DCMU treatment at 28°C than at 20°C (Fig EV1D and E). These results indicate that sugar starvation is more detrimental to plants at high temperatures.

Figure EV1. Plants are more sensitive to sugar starvation at high temperatures.

-

A, BSurvival rates of wild‐type seedlings after prolonged dark treatment. One‐week‐old light‐grown seedlings grown on the medium containing no sucrose were incubated in the dark for 7 days at different temperatures (20 or 28°C). Seedling survival rates (%) were scored after 7 days of recovery under white light at 20°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (A). **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3).

-

CExogenously supplied sucrose increases the survival rates of seedlings after prolonged dark treatment. One‐week‐old light‐grown seedlings grown on the medium containing 3% sucrose were incubated in the dark for 7 days at different temperatures (20 or 28°C). Seedling survival rates (%) were scored after 7 days of recovery under white light at 20°C. **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3).

-

D, ESurvival rates of wild‐type seedlings after DCMU treatment. One‐week‐old light‐grown seedlings were transferred to medium containing DCMU and incubated for 1 to 3 days at different temperatures (20 or 28°C). Seedling survival rates (%) were scored after 7 days of recovery under white light at 20°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (D). Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test).

Sucrose is required for the high‐temperature‐induced hypocotyl growth

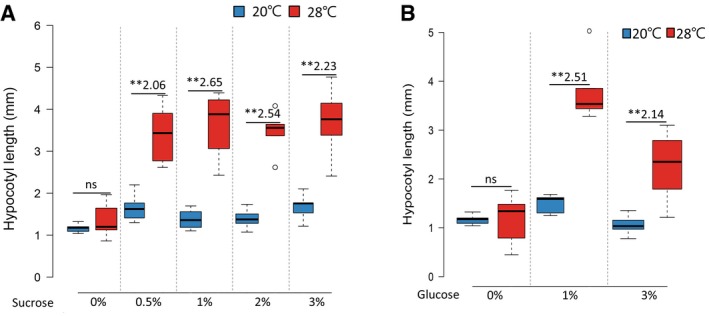

Thermomorphogenesis is an energy‐demanding and irreversible process. Given that A. thaliana plants demonstrated greater sensitivity to sugar deficiency at high temperatures, morphological changes induced by high temperatures are expected to depend on endogenous sugar availability. To examine whether thermomorphogenesis is dependent on endogenous sugar status, we measured the hypocotyl growth response to a temperature increase in A. thaliana wild‐type and suc2 mutant seedlings (Salk_038124). SUC2 is a sucrose transporter responsible for the transport of photosynthesized sucrose from source leaf tissues to sink tissues such as hypocotyls and roots. Therefore, sink tissues including hypocotyls are deficient in sucrose in the suc2 mutant. As reported before 3, the lengths of hypocotyls were significantly increased after exposure to high temperature (28°C) in wild‐type seedlings (Fig 1A). In contrast, hypocotyl growth was almost insensitive to high‐temperature exposure in the suc2 mutant (Fig 1A), suggesting that the high‐temperature‐induced hypocotyl growth is a sucrose‐dependent response. To confirm that the thermo‐insensitive hypocotyl growth in the suc2 mutant was a consequence of sugar deficiency in hypocotyls, we examined whether exogenously supplied sucrose or glucose restores thermo‐sensitivity in the suc2 mutant. In support of our hypothesis, the hypocotyl growth responses to high temperatures in the suc2 mutant were partially restored when the growth medium contained sucrose or glucose (Figs 1A and EV2A and B). These results demonstrate that sugar is required for thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth.

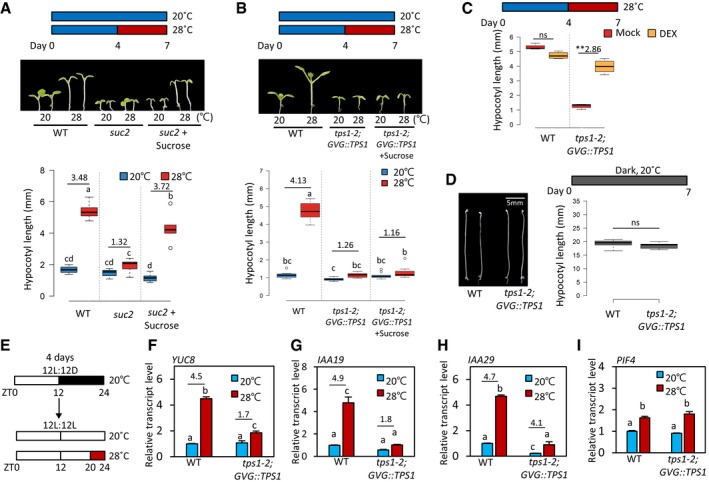

Figure 1. TPS1 is required for high‐temperature‐induced hypocotyl growth.

-

AHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and suc2 seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. The seedlings were grown on the medium with or without 3% sucrose. Representative seedlings are shown in the upper panel. Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n = 10). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). In the box plots (A–D), the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

-

BHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings grown under the same growth conditions as (A). Representative seedlings are shown in the upper panel. Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n > 10). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C).

-

CHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. The seedlings were grown on the medium containing either mock or 20 μM of dexamethasone (DEX). ns, not significant (Student's t‐test P ≥ 0.05; n > 10). **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test); n > 10. Number indicates the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (Dex/Mock).

-

DHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings grown in the dark at 20°C for 7 days. Representative seedlings are shown in the left panel. ns, not significant (Student's t‐test P ≥ 0.05; n > 10).

-

EDiagram showing plant growth conditions used for the qRT–PCR analyses in (F‐I). Seedlings were maintained under 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycles at 20°C for 4 days and then transferred to continuous light on the 5th day. The growth temperature was increased to 28°C or kept at 20°C for 4 h at Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 20‐24 before harvesting for total RNA extraction.

-

F–IThe qRT–PCR analyses of the transcript levels of YUC8, IAA19, IAA29, and PIF4. Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to those of PP2A and presented as values relative to those of wild‐type seedlings at 20°C. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). Different letters above each bar indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05). Numbers indicate the ratio of transcript levels in seedlings grown at two different temperatures (28°C/20°C).

Figure EV2. Thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth of the suc2 mutant is restored by exogenously supplied sucrose or glucose.

-

A, BHypocotyl lengths of suc2 seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. The seedlings were grown on the medium containing various concentrations of sucrose or glucose. ns, not significant (Student's t‐test P ≥ 0.05; n = 8). **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test); n = 8. Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Trehalose‐6‐phosphate synthase 1 is required for thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth

In plants, cellular sucrose content is monitored by a sucrose‐sensing signaling pathway to coordinate growth and development with sucrose availability. It was previously shown that trehalose‐6‐phosphate (T6P) concentration in plant cells is proportional to that of sucrose and that T6P functions as a sugar signaling molecule that regulates the transition to flowering and other developmental processes in Arabidopsis 24, 25. To examine whether T6P functions as a signaling molecule in the regulation of the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth as well, we determined the thermo‐sensitivity of hypocotyl growth in plants deficient in T6P due to a mutation in the TPS1 gene. TPS1 encodes trehalose‐6‐phosphate synthase, an enzyme that catalyzes the biosynthesis of T6P from glucose‐6‐phosphate and uridine diphosphate (UDP)‐glucose 26. Since the tps1 null mutants (including tps1‐2) are embryonic lethal 26, we analyzed tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 plants, in which TPS1 expression can be induced by dexamethasone (DEX) application during early embryo development, allowing the tps1‐2 embryo lethality to be rescued 27. The DEX‐rescued tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seeds were able to germinate and establish seedling development in the absence of further DEX treatment. We confirmed that the level of TPS1 transcript in tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings was still much lower than that in the wild type (Fig EV3A). Assuming that the decrease in TPS1 transcript is accompanied by a decrease in TPS1 protein, the activity of TPS1 in tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings would be lower than that in the wild type, which allows us to examine the effects of impaired TPS1 activity on the hypocotyl growth response to high temperatures.

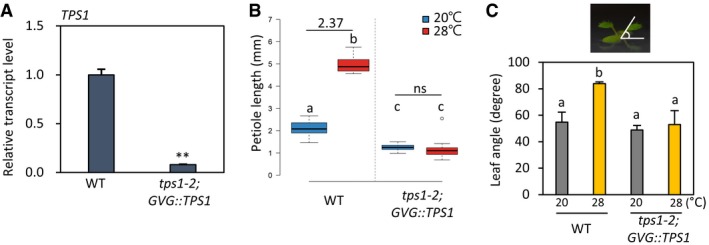

Figure EV3. TPS1 is required for thermomorphogenesis.

- The wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings were grown at 20°C for 7 days (without any DEX treatment) and harvested for total RNA extraction. The relative transcript levels of TPS1 were measured by qRT–PCR. Transcript levels of TPS1 were normalized to those of PP2A and presented as values relative to those of wild‐type seedlings. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01 (Student's t‐test).

- Petiole lengths of the first true leaves in wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 14 days or at 20°C for 7 days followed by 7 days at 28°C. Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n ≥ 20). Numbers indicate the ratio of petiole lengths (28°C/20°C). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

- Leaf elevation angle measurements of plants grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 11 days or at 20°C for 7 days followed by 4 days at 28°C. Different letters above each bar indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n = 10). Error bars indicate SD (n = 10).

Hypocotyl growth in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant was much less promoted by the exposure to a temperature of 28°C than in the wild type (Fig 1B), similarly to that observed for the suc2 mutant (Fig 1A). In addition to hypocotyl growth, the responses of petiole growth and leaf hyponasty were also impaired in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant (Fig EV3B and C). The short hypocotyls of tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings were restored by DEX application (Fig 1C), indicating that the loss of TPS1 function is responsible for the thermo‐insensitive hypocotyl growth phenotype of this mutant. Interestingly, the hypocotyl length of the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant was similar to that of the wild type in the dark (Fig 1D), suggesting that the short hypocotyls of tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings exposed to high temperatures were not the result of a general growth defect caused by the lack of TPS1 activity. Therefore, TPS1 appears to specifically mediate the high‐temperature‐induced hypocotyl growth. On the other hand, while the thermo‐sensitivity of the suc2 mutant was restored by exogenously supplied sucrose (Fig 1A), the hypocotyl growth response to high temperatures was not significantly affected by sucrose application in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant (Fig 1B). These results suggest that T6P may function as a signaling molecule rather than as an energy source for the sugar regulation of the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth.

To identify the molecular mechanisms by which TPS1 regulates the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth, we measured the transcriptional responses of PIF4 target genes (YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29) to high‐temperature exposure because the thermoresponsive growth is highly dependent on the activation of PIF4 (Fig EV4A and B) 6, 9, 11. For this, the light/dark‐entrained seedlings were exposed to 28°C during Zeitgeber time 20–24 (Fig 1E) because PIF4 and its target genes are highly responsive to high temperatures in this time frame 28. Consistent with the thermo‐insensitive hypocotyl growth phenotype already described (Fig 1B), a much lower increase in the transcript levels of the PIF4 target genes was observed after 4‐h high‐temperature exposure in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant compared to the wild type (Fig 1F–H). Since the thermo‐induction of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 expression is mediated by PIF4, it was likely that PIF4 level or its transcriptional activity was reduced in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant. However, the transcript levels of PIF4 at both 20 and 28°C in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant were not significantly different from those observed in wild‐type plants (Fig 1I), suggesting that TPS1 regulates PIF4 protein post‐transcriptionally.

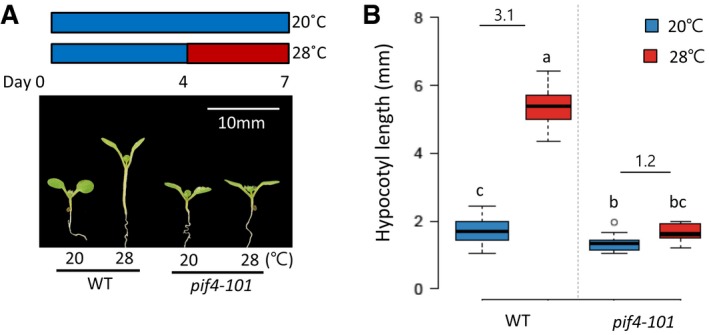

Figure EV4. Hypocotyl lengths of the wild‐type and pif4 mutant seedlings grown at two different temperatures.

-

A, BHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and pif4‐101 seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (A). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n > 15). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

The stability of PIF4 protein is dependent on trehalose‐6‐phosphate synthase 1

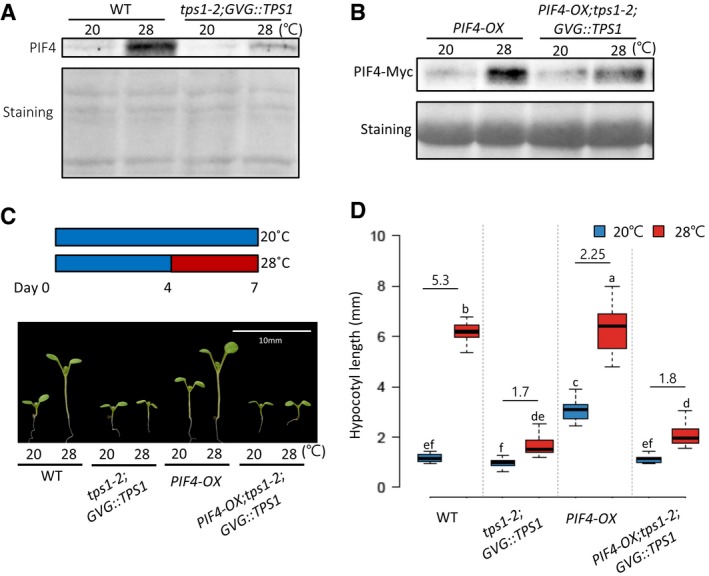

We next determined whether tps1 mutation alters the level of PIF4 protein. In wild‐type plants, endogenous PIF4 protein level was significantly increased by high‐temperature exposure (Fig 2A), consistent with the upregulation of PIF4 mRNA (Fig 1I). Although PIF4 mRNA was similarly increased by high‐temperature exposure in wild‐type and tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant seedlings (Fig 1I), PIF4 protein level was much lower in the latter (Fig 2A), suggesting that the PIF4 protein stability may be reduced in the absence of TPS1 activity. To further confirm the role of TPS1 in the regulation of PIF4 protein stability, we determined the level of PIF4‐Myc protein driven by a constitutive active promoter (35S) in a wild‐type (PIF4‐OX) or in a tps1‐2 mutant (PIF4‐OX;tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1) background. The level of PIF4‐Myc protein under the control of the constitutive promoter was higher in the PIF4‐OX plants grown at 28°C than in those grown at 20°C, indicating that PIF4 protein is stabilized at high temperatures (Fig 2B). The level of PIF4‐Myc protein was lower in PIF4‐OX;tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 plants compared to PIF4‐OX plants at both temperatures, with more significant difference observed at 28°C (Fig 2B). Unexpectedly, the overexpression of PIF4 could not revert the hypocotyl growth of the tps1‐2 mutant (Fig 2C and D), altogether suggesting that TPS1 is required for PIF4 stabilization at higher temperatures and that the impaired responses to high temperatures in the tps1‐2 mutant are at least partly due to the reduced PIF4 protein.

Figure 2. The stability of PIF4 protein is dependent on TPS1.

-

AWestern blotting with anti‐PIF4 antibody shows that PIF4 protein levels are decreased in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutants compared to wild‐type plants. Seedlings were maintained under 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycles at 20°C for 4 days and then transferred under continuous light on the 5th day. The growth temperature was increased to 28°C or kept at 20°C for 4 h at ZT 20‐24 before harvesting for total protein extraction. Equal loading of samples is shown by Ponceau S staining.

-

BWestern blotting showing the levels of PIF4‐Myc protein in PIF4‐OX and PIF4‐OX;tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seedlings. Total protein was extracted from the seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. Western blotting was probed using an anti‐Myc antibody. Ponceau S staining is shown for equal loading.

-

C, DHypocotyl lengths in seedlings of different genotypes. Seedlings were grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (C). Numbers in (D) indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n > 12). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

KIN10 mediates the trehalose 6‐phosphate regulation of thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth

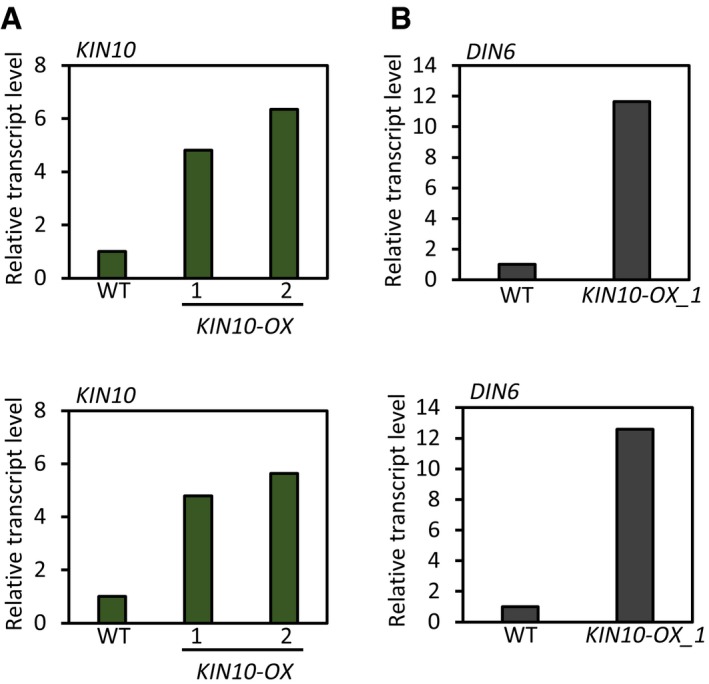

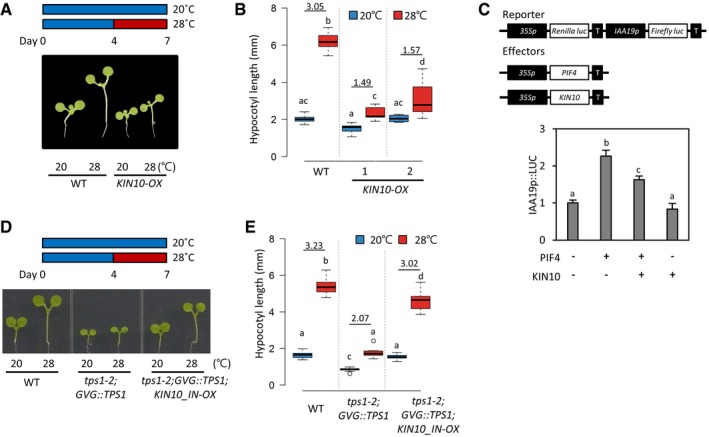

In plants, cellular sugar starvation triggers a global gene expression reprogramming, which is mediated by the evolutionary conserved energy‐sensing protein kinase SNF1‐RELATED KINASE1 (SnRK1) complex 1. The SnRK1 complex is composed of a catalytic subunit (α) and two regulatory subunits (β, γ). In Arabidopsis, KIN10, the catalytic subunit of the SnRK1 complex, is a central regulator of sugar starvation responses 1, 29. It was reported that the kinase activity of KIN10 is repressed by T6P 30. Therefore, it is likely that KIN10 mediates the TPS1 regulation of thermomorphogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we generated transgenic plants overexpressing KIN10 (KIN10‐OX) and analyzed the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth of the KIN10‐OX plants. The qRT–PCR analysis shows that KIN10 is indeed overexpressed in KIN10‐OXs (Fig EV5A). We further confirmed that the overexpressed KIN10 is functional by measuring the transcript levels of a KIN10‐induced gene, DIN6 (Fig EV5B) 29, 31. While hypocotyl lengths in the wild‐type seedlings were about threefold increased after high‐temperature (28°C) exposure (Fig 3A and B), hypocotyl lengths in the KIN10‐OX seedlings were increased by < twofold (Fig 3A and B), indicating that KIN10 suppresses the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth. To further ascertain whether this KIN10‐mediated regulation of thermoresponsive growth occurs through the modulation of PIF4 activity, we carried out transient gene expression assays using Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. In line with previous reports 9, we found that PIF4 increased the IAA19 promoter activity by more than twofold (Fig 3C). However, co‐transfection with KIN10 significantly repressed this process (Fig 3C), suggesting that KIN10 inhibits PIF4 function.

Figure EV5. qRT–PCR analyses of KIN10 and DIN6 in KIN10‐OX transgenic plants.

-

A, BSeedlings were grown under continuous white light for 6 days and harvested for total RNA extraction. Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to those of PP2A and presented as values relative to those of wild‐type seedlings. The results of two independent experiments are shown.

Figure 3. KIN10 mediates the T6P regulation of thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth.

-

A, BHypocotyl lengths of wild‐type and KIN10‐OX seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (A). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n > 15). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

-

CTransient gene expression assays. The reporter vector containing 35S::Renilla luciferase and IAA19p::Firefly luciferase was co‐transfected with 35S::PIF4 and 35S::KIN10 into Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. The activity of Firefly luciferase under the control of IAA19 promoter was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). Different letters above each bar indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05). T, 35S terminator.

-

D, EHypocotyl lengths of seedlings grown under continuous white light at 20°C for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by 3 days at 28°C. Representative seedlings are shown in (D). Numbers indicate the ratio of hypocotyl lengths (28°C/20°C). Different letters above each box indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n > 15). In the box plots, the thick lines indicate median values, the lower and upper ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ends of the whiskers are set at 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Given that KIN10 represses the thermoresponsive growth and its kinase activity is repressed by T6P 30, the thermo‐insensitive phenotype in the tps1 mutant is likely to be caused by the highly activated KIN10 under the T6P‐deficient conditions. To genetically confirm this possibility, we inactivated KIN10 in the tps1‐2 mutant by overexpressing ATP‐binding site‐mutated KIN10 (KIN10_IN) (tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1;KIN10_IN‐OX), which is driven by the 35SC4PPDK promoter 31, and measured the hypocotyl growth response to high temperatures. The overexpression of KIN10_IN was shown to inhibit the activities of endogenous KIN10 and KIN11 31, probably by competing with them for binding to the regulatory subunits (β, γ). In the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant, the hypocotyl growth was much less promoted by high temperature than in wild‐type plants (Fig 3D and E). However, the impairment of the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant was largely restored by the overexpression of KIN10_IN (Fig 3D and E), suggesting that the highly activated KIN10 is responsible for the impairment of the thermoresponsive growth in the tps1 mutant. Taken together, these results provide good evidence that KIN10 mediates the T6P regulation of thermomorphogenesis.

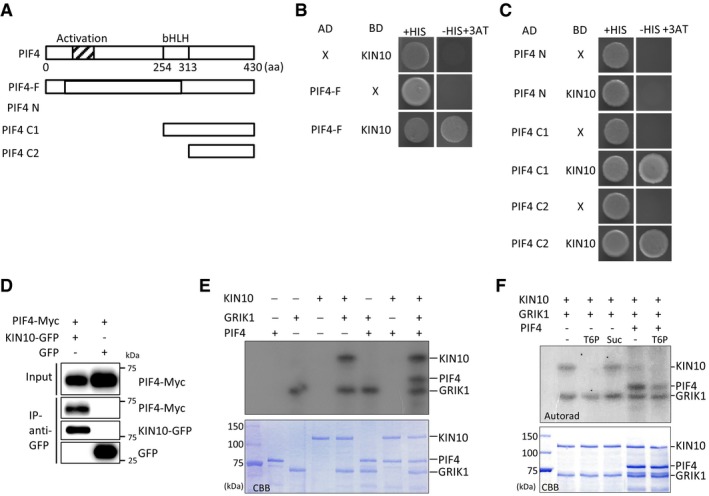

KIN10 directly interacts with and phosphorylates PIF4

We next asked whether KIN10 directly interacts with PIF4 to repress its transcriptional activity. For this, we first performed yeast two‐hybrid assays. Yeast cells expressing both AD‐PIF4 (PIF4 fused to a Gal4 activation domain) and BD‐KIN10 (KIN10 fused to a Gal4‐binding domain) grew well on the selection medium lacking histidine, whereas yeast cells expressing either AD‐PIF4 (with BD) or BD‐KIN10 (with AD) were not able to grow in the absence of histidine, indicating that KIN10 directly interacts with PIF4 (Fig 4A and B). Yeast two‐hybrid assays with N‐ or C‐terminal truncated PIF4 further revealed that PIF4 C‐terminus including the bHLH domain (amino acids 254–430) is required for the interaction with KIN10 (Fig 4A and C). To further confirm KIN10‐PIF4 interaction in planta, we performed co‐immunoprecipitation assays using Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. Figure 4D shows that PIF4‐Myc was immunoprecipitated by anti‐GFP antibody only when it was co‐transfected with KIN10‐GFP, confirming that KIN10 interacts with PIF4 in planta.

Figure 4. KIN10 directly interacts with and phosphorylates PIF4.

-

ABox diagram of various fragments of PIF4 used in (B, C).

-

B, CYeast two‐hybrid assays showing the direct interaction between PIF4 and KIN10. Yeast clones were grown on the synthetic dropout medium with histidine (+HIS) or without histidine (−HIS) plus 25 mM of 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT).

-

DCo‐IP assays showing the interaction between PIF4 and KIN10 in vivo. Protein extracts from protoplasts expressing PIF4‐Myc and KIN10‐GFP (or GFP) were immunoprecipitated with anti‐GFP antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody.

-

EGRIK1‐activated KIN10 phosphorylates PIF4. In vitro phosphorylation assays were performed at 30°C for 30 min using 1 μg of purified recombinant proteins (KIN10, GRIK1, or PIF4). 32P‐labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography. CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue‐stained gel.

-

FT6P inhibits PIF4 phosphorylation by KIN10. This assay was performed with 1 μg of each protein at 30°C for 30 min in the presence of 1 mM T6P or sucrose (Suc).

KIN10 is the catalytic subunit of SnRK1 kinase complex. Thus, we examined whether KIN10 phosphorylates PIF4 by in vitro kinase assays. Since the kinase activity of KIN10 is dependent on GEMINIVIRUS REP‐INTERACTING KINASE (GRIK)1‐mediated phosphorylation of its activation loop 32, we included GRIK1 in these assays. Consistent with the results of a previous study 32, KIN10 was phosphorylated by GRIK1 (Fig 4E). While PIF4 was not phosphorylated by KIN10 nor GRIK1 when added separately, PIF4 phosphorylation was only detected in the presence of both KIN10 and GRIK1 (Fig 4E). The phosphorylation of PIF4 was dependent on the concentration of KIN10 and the reaction time (Appendix Fig S1), indicating that GRIK1‐activated KIN10 phosphorylates PIF4. It was shown that T6P inhibits the association of GRIK1 and KIN10, attenuating the GRIK1‐mediated phosphorylation and activation of KIN10 33. Indeed, KIN10 phosphorylation by GRIK1 was severely reduced by T6P, but not by sucrose (Fig 4F). In addition, PIF4 phosphorylation was also reduced in the presence of T6P (Fig 4F), indicating that T6P inhibits the KIN10‐mediated PIF4 phosphorylation.

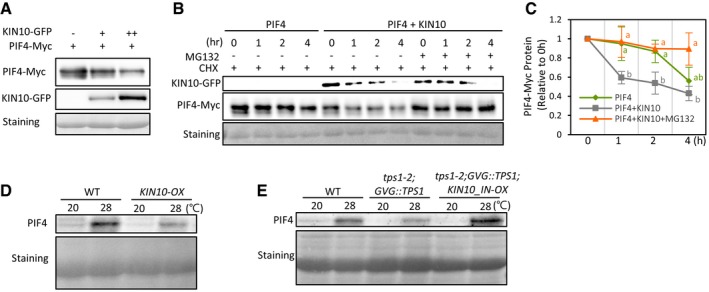

KIN10 decreases the stability of PIF4 through proteasomal degradation

The phosphorylation of PIF4 is highly associated with its stability. In this regard, it was previously shown that PIF4 stability diminishes by both phyB‐ and BIN2‐induced phosphorylation 13, 19. Therefore, it is highly probable that the KIN10‐mediated PIF4 phosphorylation could also alter PIF4 stability. Indeed, we observed that the level of PIF4‐Myc was significantly diminished when it was co‐expressed with KIN10‐GFP in the co‐immunoprecipitation assays for KIN10‐PIF4 interaction (Fig 4D). Notably, the level of PIF4‐Myc was negatively correlated with the level of KIN10‐GFP in mesophyll protoplasts (Fig 5A). In contrast, the level of GFP was not reduced by co‐expressed KIN10 (Appendix Fig S2), indicating that the reduction of PIF4 protein is not attributable to the negative effects of KIN10 on the general translation rates. To examine whether the reduced amount of PIF4 protein results from the destabilization of PIF4 protein, we determined the time course of PIF4‐Myc protein levels after de novo protein synthesis was inhibited by cycloheximide (CHX). In CHX experiments, the degradation of PIF4‐Myc protein was accelerated by co‐transfection with KIN10‐GFP (Fig 5B and C, and Appendix Fig S3), indicating that KIN10 decreases the stability of PIF4 protein. The reduced PIF4‐Myc stability was partially restored by the 26S proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig 5B and C, and Appendix Fig S3). These results indicate that the KIN10‐induced phosphorylation indeed decreases the stability of PIF4 protein through the 26S proteasome‐mediated degradation. In accordance with this notion, endogenous PIF4 protein level was lower in KIN10‐OX plants grown at 28°C than in wild‐type plants grown under the same conditions (Fig 5D). Moreover, the level of endogenous PIF4 protein in the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant was increased by the overexpression of KIN10_IN (tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1;KIN10_IN‐OX) (Fig 5E), which is consistent with the finding of more elongated hypocotyls in tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1;KIN10_IN‐OX plants as compared to tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 plants (Fig 3D and E). Since KIN10_IN is a kinase‐inactive form of KIN10 31, these results suggest the KIN10‐mediated phosphorylation facilitates the degradation of PIF4 protein, being this mechanism at least partly responsible for the impaired thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth observed in the tps1 mutant.

Figure 5. KIN10 decreases the stability of PIF4 through proteasomal degradation.

-

AThe levels of PIF4‐Myc are negatively correlated with the levels of KIN10‐GFP. Total proteins were extracted from mesophyll protoplasts transfected with different amounts of KIN10‐GFP and PIF4‐Myc and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody. Ponceau S staining is shown for equal loading.

-

B, CKIN10 reduces the stability of PIF4 through 26S proteasome‐mediated degradation. Transfected mesophyll protoplasts were pre‐treated with or without 20 μM MG132 for 4 h and then incubated in the presence of 100 μM cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time. Total protein was extracted from the protoplasts and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody. Ponceau S staining is shown for equal protein loading. Representative Western blots are shown in (B). Similar results were obtained from two other independent experiments (Appendix Fig S3). Quantification of relative PIF4‐Myc levels is shown in (C). PIF4‐Myc levels are presented as values relative to those at 0 h. In (C), different letters above each point indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey's HSD; P < 0.05; n = 3). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3).

-

D, EWestern blotting showing endogenous PIF4 protein levels in the seedlings grown in the same conditions as in Fig 3A. Total protein extracted from the seedlings was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti‐PIF4 antibody. Ponceau S staining shows equal protein loading.

Discussion

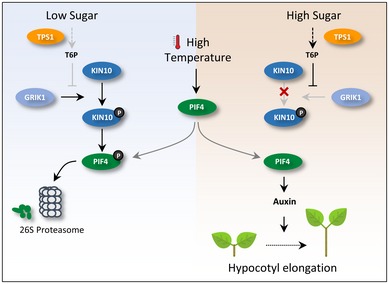

To prevent sugar starvation, energy‐demanding processes like growth and development must be coordinately regulated by endogenous sugar availability. The integration of sugar availability with growth regulation in plants is mediated by T6P, a very low‐abundant sugar whose cellular level is proportional to that of sucrose 34. In this study, we show that sugar availability determines the response of hypocotyl growth to high temperatures through the T6P‐dependent pathway that controls the stability of the temperature‐regulated transcription factor PIF4. Our results further demonstrate that an evolutionarily conserved energy‐sensing kinase, SnRK1, mediates the T6P‐regulation of the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth (Fig 6).

Figure 6. A Model for the regulation of thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth by the T6P‐KIN10‐PIF4 signaling module.

Under low‐sugar conditions, KIN10 is activated by GRIK1 and phosphorylates PIF4. The phosphorylation induces the degradation of PIF4 through 26S proteasome, suppressing PIF4‐mediated thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth. An increase in sucrose results in a rise in T6P. T6P inhibits the GRIK1‐mediated KIN10 activation, which allows an increase in PIF4 protein in response to high temperatures. The increased PIF4 induces hypocotyl elongation by activating auxin signaling.

Our study provides robust evidence supporting the hypothesis that sugar availability regulates high‐temperature‐mediated hypocotyl growth through the T6P‐signaling pathway. First, the thermoresponsive growth was impaired in the T6P‐deficient mutant, tps1, in which the thermo‐sensitivity was not restored by exogenous sucrose application. Second, the impairment of the thermoresponsive growth in the tps1 mutant was restored by the inactivation of the SnRK1 kinase KIN10, whose catalytic activity is increased in the absence of T6P. Additionally, the overexpression of KIN10 suppressed the thermoresponsive growth. Third, KIN10 phosphorylates PIF4 in a GRIK1‐dependent manner and T6P inhibits the KIN10 phosphorylation of PIF4. Fourth, KIN10 destabilizes PIF4 protein through 26S proteasome‐mediated degradation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that an endogenous sugar signal is integrated into the temperature‐dependent growth regulation through the T6P‐KIN10‐PIF4 signaling module.

Thermomorphogenesis, including elongation of hypocotyls and petioles, is one of the adaptive responses to alleviate high‐temperature‐induced stresses in plants 5. However, plants are likely to experience sugar deficiency more often at high temperatures because maintenance respiration rate increases continuously with temperature and photosynthesis efficiency is decreased at sub‐optimal high temperatures 35, 36. Moreover, our results revealed that Arabidopsis plants are more sensitive to sugar starvation at elevated temperatures. Therefore, thermomorphogenesis, which is a high‐energy‐demanding and irreversible process that occurs at high temperatures, should be controlled by the integration of multiple signals including endogenous sugar availability to prevent sugar starvation. In this sense, the regulation of thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth by the T6P‐KIN10‐PIF4 signaling module ensures that this mechanism will be induced only when sugar levels in plant cells are sufficient to support such adaptive growth responses.

PIF4 integrates a wide range of signaling pathways to optimize plant growth 7. Given that the stability of PIF4 protein is dependent on T6P, it is likely that other growth responses, as well as thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth, are also impaired in the tps1 mutant. The slightly shorter hypocotyls of tps1 mutants compared with those of the wild type at 20°C support the possible pleiotropic effects of T6P in growth responses. Indeed, a previous study showed that T6P and KIN10 are involved in sucrose‐induced hypocotyl growth under short photoperiod conditions 37. The sucrose‐induced hypocotyl growth requires PIF factors (PIF4 and PIF5) 38, 39. Consistent with the positive roles of these PIFs in hypocotyl growth, the stability of PIF5 is increased by sucrose 38. Given the high sequence similarity between PIF4 and PIF5 proteins, it is highly probable that T6P‐KIN10 regulates the stability of both PIF4 and PIF5. Indeed, PIF5 also interacted with KIN10 in yeast two‐hybrid assays (Appendix Fig S4), suggesting that the T6P‐KIN10 pathway could mediate the sucrose regulation of hypocotyl growth through PIF4 and PIF5.

It has been shown that sucrose‐induced hypocotyl growth is also dependent on the BR‐activated transcription factor BZR1 40. BZR1 is a positive regulator of hypocotyl growth in the BR signaling pathway. Sucrose stabilizes BZR1 through the target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway, thereby promoting hypocotyl growth 40. The activity of BZR1 is also required for the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth 9, 20. At high temperatures, BZR1 is activated and directly increases PIF4 transcript level 20. Additionally, BZR1 interacts with PIF4, and they cooperatively promote hypocotyl growth 9. Therefore, it is possible that sugar levels impact on the regulation of the thermoresponsive hypocotyl growth through the TOR‐BZR1 signaling pathway as well as through the T6P‐KIN10‐PIF4 signaling pathway. Since BZR1 and PIF4 are interdependent in the regulation of hypocotyl growth 9, both the activation of TOR and the T6P‐mediated inhibition of KIN10 might be necessary for thermomorphogenesis.

PIF4 is phosphorylated by the light‐activated phytochrome signal and the brassinosteroid‐repressed GSK3‐like kinase BIN2 19. The light‐induced phosphorylation destabilizes PIF4 stability through the proteasome‐mediated degradation 13. Recently, the light‐induced phosphorylation was also shown to prevent PIF4 from binding to its target promoters 14. BIN2‐mediated phosphorylation destabilizes PIF4 protein 19. Our study shows that KIN10‐mediated phosphorylation also reduces the stability of PIF4. Thus, it appears that multiple signals are integrated to regulate plant growth by influencing the phosphorylation status of PIF4. The degree of PIF4 phosphorylation may account for the fine‐tuning of the PIF4 activity form multiple endogenous and environmental signals. It is possible that different signals could phosphorylate the same residues in PIF4 for proteasomal degradation. The residues phosphorylated by BIN2 have been identified: T160, S164, and S168 19. It was reported that the substitution of these residues to alanines significantly increased the stability of PIF4 19. Whether these residues are also phosphorylated by light or by KIN10 should be determined in future studies.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown in a greenhouse with light/dark cycles at 22–24°C for general growth and seed harvesting. All the A. thaliana plants used in this study belonged to the Col‐0 ecotype background. The full‐length KIN10 coding sequence (At3g01090.2) was cloned into the gateway‐compatible vector pX‐YFP to obtain transgenic plants overexpressing KIN10 (KIN10‐OX). Gene‐specific primers are listed in Appendix Table S1. The seeds of the tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 mutant were kindly provided by Markus Schmid 25. The tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 plants were treated with 1 μM DEX to promote flowering and produce viable seeds. The KIN10_IN‐OX seeds were kindly provided by Sang‐Dong Yoo 31. The PIF4‐OX were described previously 9. tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1;KIN10_IN‐OX was generated by crossing tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 and KIN10_IN‐OX 31. Transposon insertion in tps1‐2 was confirmed by PCR‐based genotyping using primers TPS1_1 st _intron F, EnRB544_F, and tps471u_R (Appendix Table S1). Homozygosity of GVG::TPS1 was confirmed by segregation analysis of hygromycin resistance. T‐DNA insertion for KIN10_IN‐OX was confirmed by PCR‐based genotyping using primers 35SF and KIN10_R (Appendix Table S1). PIF4‐OX;tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 was generated by crossing tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 and PIF4‐OX 9. T‐DNA insertion for PIF4‐OX was confirmed by PCR‐based genotyping using primers 35SF and PIF4_R (Appendix Table S1).

Hypocotyl length measurement

Seeds sterilized using 70% (v/v) ethanol and 0.01% (v/v) Triton X‐100 were plated on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (PhytoTechnology Laboratories) supplemented with 0.75% phytoagar. After 3 days of incubation at 4°C, the plates were placed under a white light for 6 h to promote seed germination and incubated at 20°C under continuous white light conditions (light intensity: 30 μmol/m2/s) for 7 days or at 20°C for 4 days followed by incubation at 28°C for 3 days. Seedlings (n > 10) were photographed, and hypocotyl lengths were measured by using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Quantitative real‐time PCR gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the seedlings grown in the indicated conditions using the MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer's instructions. M‐MLV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for cDNA synthesis. Quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT–PCR) was performed using the CFX96 Real‐Time PCR detection system (Bio‐Rad) and the EvaGreen master mix (Solgent). Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to that of the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2a (PP2A) gene and were shown relative to the transcript levels in the wild type. The qRT–PCR experiments were carried out in three biological replicates, each with more than 50 seedlings. Gene‐specific primers are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted with 2× protein extraction buffer (125 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue, with β‐mercaptoethanol added to 10% before use). A Western blot analysis was performed to determine endogenous PIF4 levels as well as PIF4‐Myc and KIN10‐GFP protein levels, using anti‐PIF4 antibody (Agrisera, AS16 3157), anti‐Myc antibody (1:5,000 dilution, Cell Signaling), and anti‐GFP antibody (1:5,000 dilution, Clontech), respectively.

Transient gene expression assays

Isolated Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts were transfected with a total of 20 μg of DNA and incubated overnight. Protoplasts were harvested by centrifugation and lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega). Firefly and Renilla (as an internal standard) luciferase activities were measured by using a dual‐luciferase reporter kit (Promega).

Co‐IP assays

For co‐IP assays using Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts, isolated mesophyll protoplasts were transfected with a total of 20 μg of DNA (35S::PIF4‐Myc and 35S::KIN10‐GFP) and incubated overnight. Total proteins were extracted from transfected protoplasts using the IP buffer (50 mM Tris–Cl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 75 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X‐100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1× protease inhibitor). After centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was incubated for 1 h with anti‐green fluorescent protein (GFP; A11122, 5 μg, Thermo Fisher Scientific) immobilized on magnetic beads (Dynabeads™ Protein G, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The beads were then washed for three times with the IP buffer, and the eluted samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti‐Myc and anti‐GFP antibodies.

Yeast two‐hybrid assays

To detect PIF4 interaction with KIN10, the various fragments of PIF4 complementary DNA were subcloned into the gateway‐compatible vectors pGADT7 or pGBKT7 (Clontech) using the yeast reporter strain AH109. The yeast clones were grown on the synthetic dropout medium with histidine (+His) or without histidine (−His), containing 5 or 25 mM of 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole.

Starvation assays

To induce sugar starvation, 1‐week‐old plants were incubated either in the dark for 6 days or on the medium containing 20 μM of 3‐(3, 4‐dichlorophenyl)‐1,1‐dimethylurea (DCMU), photosynthesis inhibitor, for 1 to 3 days under white light. DCMU was purchased from TOKYO Chem. Co. (Tokyo, Japan). After darkness or DCMU treatment, seedlings were allowed to recover at 20°C. After 7 days, plant survival rates were scored. Starvation assays were performed using three or four biological replicates, each with 30 seedlings.

In vitro phosphorylation assays

Recombinant proteins of GRIK1, KIN10, and PIF4 were expressed and purified from E. coli. PIF4 and GRIK1 were subcloned into pGEX 4T vector (GE Healthcare) with glutathione S‐transferase and streptavidin affinity tags fused to their N‐ and C‐termini, respectively, as previously reported 41. KIN10 was subcloned into pCOLD TF vector (TaKaRa) that has a histidine affinity‐tag and trigger factor chaperone at N‐termini. Gene‐specific primers for these clonings are listed in Appendix Table S1. In vitro phosphorylation assay was performed with GRIK1 and KIN10, as previously described 32, 33, and also by including PIF4. Briefly, a 30 μl assay was performed at 30°C for 30 min with 1 μg of purified recombinant proteins (KIN10, GRIK1, or PIF4) in a reaction buffer: 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 200 μM ATP containing 10 μCi of [γ‐32P] ATP. Proteins were then resolved on SDS‐polyacrylamide gels and dried under vacuum before autoradiography by exposing on X‐ray films. To verify the proteins loaded, Coomassie Blue protein staining was performed before drying. For the phosphorylation assays with supplement of T6P or sucrose, each T6P and sucrose (the final concentration of 1 mM) was added to the reaction mixture containing KIN10 and incubated on ice for 30 min, before GRIK1 and PIF4 were added to the reaction.

Author contributions

GH, SK, J‐IK, and EO conceived the study and designed the experiments. GH, SK, J‐YC, IP, and EO carried out the experiments. EO and J‐IK supervised the work. GH, SK, J‐IK, and EO wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File

Acknowledgements

We thank Markus Schmid for providing tps1‐2;GVG::TPS1 seeds, Christian Fankhauser for providing pif4‐101 seeds, and Sang‐Dong Yoo for providing KIN10_IN‐OX seeds. This research was supported by grants from Basic Research Lab Program (grant no. NRF‐2017R1A4A1015620) and Basic Science Research Program (grant nos. NRF‐2016R1C1B2008821 and 2017R1A2B4010349) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Next‐Generation BioGreen 21 Program from Rural Development Administration (RDA), Republic of Korea (grant no. PJ01314801), and a Korea University Grant.

EMBO Reports (2019) 20: e47828

References

- 1. Rolland F, Baena‐Gonzalez E, Sheen J (2006) Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 675–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu SM (1999) Cellular and genetic responses of plants to sugar starvation. Plant Physiol 121: 687–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gray WM, Ostin A, Sandberg G, Romano CP, Estelle M (1998) High temperature promotes auxin‐mediated hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7197–7202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quint M, Delker C, Franklin KA, Wigge PA, Halliday KJ, Zanten M (2016) Molecular and genetic control of plant thermomorphogenesis. Nat Plants 2: 15190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crawford AJ, McLachlan DH, Hetherington AM, Franklin KA (2012) High temperature exposure increases plant cooling capacity. Curr Biol 22: R396–R397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koini MA, Alvey L, Allen T, Tilley CA, Harberd NP, Whitelam GC, Franklin KA (2009) High temperature‐mediated adaptations in plant architecture require the bHLH transcription factor PIF4. Curr Biol 19: 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi H, Oh E (2016) PIF4 integrates multiple environmental and hormonal signals for plant growth regulation in Arabidopsis . Mol Cells 39: 587–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinez C, Espinosa‐Ruiz A, de Lucas M, Bernardo‐Garcia S, Franco‐Zorrilla JM, Prat S (2018) PIF4‐induced BR synthesis is critical to diurnal and thermomorphogenic growth. EMBO J 37: e99552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oh E, Zhu JY, Wang ZY (2012) Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat Cell Biol 14: 802–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Franklin KA, Lee SH, Patel D, Kumar SV, Spartz AK, Gu C, Ye S, Yu P, Breen G, Cohen JD et al (2011) Phytochrome‐interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 20231–20235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun J, Qi L, Li Y, Chu J, Li C (2012) PIF4‐mediated activation of YUCCA8 expression integrates temperature into the auxin pathway in regulating Arabidopsis hypocotyl growth. PLoS Genet 8: e1002594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huq E, Quail PH (2002) PIF4, a phytochrome‐interacting bHLH factor, functions as a negative regulator of phytochrome B signaling in Arabidopsis . EMBO J 21: 2441–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lorrain S, Allen T, Duek PD, Whitelam GC, Fankhauser C (2008) Phytochrome‐mediated inhibition of shade avoidance involves degradation of growth‐promoting bHLH transcription factors. Plant J 53: 312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park E, Kim Y, Choi G (2018) Phytochrome B requires PIF degradation and sequestration to induce light responses across a wide range of light conditions. Plant Cell 30: 1277–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Legris M, Klose C, Burgie ES, Rojas CC, Neme M, Hiltbrunner A, Wigge PA, Schafer E, Vierstra RD, Casal JJ (2016) Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis . Science 354: 897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jung JH, Domijan M, Klose C, Biswas S, Ezer D, Gao M, Khattak AK, Box MS, Charoensawan V, Cortijo S et al (2016) Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis . Science 354: 886–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma D, Li X, Guo Y, Chu J, Fang S, Yan C, Noel JP, Liu H (2016) Cryptochrome 1 interacts with PIF4 to regulate high temperature‐mediated hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 224–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayes S, Sharma A, Fraser DP, Trevisan M, Cragg‐Barber CK, Tavridou E, Fankhauser C, Jenkins GI, Franklin KA (2017) UV‐B perceived by the UVR8 photoreceptor inhibits plant thermomorphogenesis. Curr Biol 27: 120–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernardo‐Garcia S, de Lucas M, Martinez C, Espinosa‐Ruiz A, Daviere JM, Prat S (2014) BR‐dependent phosphorylation modulates PIF4 transcriptional activity and shapes diurnal hypocotyl growth. Genes Dev 28: 1681–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ibanez C, Delker C, Martinez C, Burstenbinder K, Janitza P, Lippmann R, Ludwig W, Sun H, James GV, Klecker M et al (2018) Brassinosteroids dominate hormonal regulation of plant thermomorphogenesis via BZR1. Curr Biol 28: 303–310 e303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feng S, Martinez C, Gusmaroli G, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang F, Chen L, Yu L, Iglesias‐Pedraz JM, Kircher S et al (2008) Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451: 475–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Lucas M, Daviere JM, Rodriguez‐Falcon M, Pontin M, Iglesias‐Pedraz JM, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Blazquez MA, Titarenko E, Prat S (2008) A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451: 480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stavang JA, Gallego‐Bartolome J, Gomez MD, Yoshida S, Asami T, Olsen JE, Garcia‐Martinez JL, Alabadi D, Blazquez MA (2009) Hormonal regulation of temperature‐induced growth in Arabidopsis . Plant J 60: 589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Figueroa CM, Lunn JE (2016) A tale of two sugars: trehalose 6‐phosphate and sucrose. Plant Physiol 172: 7–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wahl V, Ponnu J, Schlereth A, Arrivault S, Langenecker T, Franke A, Feil R, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Schmid M (2013) Regulation of flowering by trehalose‐6‐phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana . Science 339: 704–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eastmond PJ, van Dijken AJH, Spielman M, Kerr A, Tissier AF, Dickinson HG, Jones JDG, Smeekens SC, Graham IA (2002) Trehalose‐6‐phosphate synthase 1, which catalyses the first step in trehalose synthesis, is essential for Arabidopsis embryo maturation. Plant J 29: 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Dijken AJH, Schluepmann H, Smeekens SCM (2004) Arabidopsis trehalose‐6‐phosphate synthase 1 is essential for normal vegetative growth and transition to flowering. Plant Physiol 135: 969–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu JY, Oh E, Wang T, Wang ZY (2016) TOC1‐PIF4 interaction mediates the circadian gating of thermoresponsive growth in Arabidopsis . Nat Commun 7: 13692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baena‐Gonzalez E, Rolland F, Thevelein JM, Sheen J (2007) A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448: 938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang YH, Primavesi LF, Jhurreea D, Andralojc PJ, Mitchell RAC, Powers SJ, Schluepmann H, Delatte T, Wingler A, Paul MJ (2009) Inhibition of SNF1‐related protein kinase1 activity and regulation of metabolic pathways by trehalose‐6‐phosphate. Plant Physiol 149: 1860–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cho YH, Hong JW, Kim EC, Yoo SD (2012) Regulatory functions of SnRK1 in stress‐responsive gene expression and in plant growth and development. Plant Physiol 158: 1955–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen W, Reyes MI, Hanley‐Bowdoin L (2009) Arabidopsis protein kinases GRIK1 and GRIK2 specifically activate SnRK1 by phosphorylating its activation loop. Plant Physiol 150: 996–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhai Z, Keereetaweep J, Liu H, Feil R, Lunn JE, Shanklin J (2018) Trehalose 6‐phosphate positively regulates fatty acid synthesis by stabilizing wrinkled1. Plant Cell 30: 2616–2627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lunn JE, Feil R, Hendriks JH, Gibon Y, Morcuende R, Osuna D, Scheible WR, Carillo P, Hajirezaei MR, Stitt M (2006) Sugar‐induced increases in trehalose 6‐phosphate are correlated with redox activation of ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase and higher rates of starch synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana . Biochem J 397: 139–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berry J, Bjorkman O (1980) Photosynthetic response and adaptation to temperature in higher‐plants. Annu Rev Plant Phys 31: 491–543 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huntingford C, Atkin OK, Martinez‐de la Torre A, Mercado LM, Heskel MA, Harper AB, Bloomfield KJ, O'Sullivan OS, Reich PB, Wythers KR et al (2017) Implications of improved representations of plant respiration in a changing climate. Nat Commun 8: 1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Simon NML, Kusakina J, Fernandez‐Lopez A, Chembath A, Belbin FE, Dodd AN (2018) The energy‐signaling Hub SnRK1 is important for sucrose‐induced hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol 176: 1299–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart JL, Maloof JN, Nemhauser JL (2011) PIF genes mediate the effect of sucrose on seedling growth dynamics. PLoS ONE 6: e19894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu ZJ, Zhang YQ, Liu RZ, Hao HL, Wang Z, Bi YR (2011) Phytochrome interacting factors (PIFs) are essential regulators for sucrose‐induced hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis . J Plant Physiol 168: 1771–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang Z, Zhu JY, Roh J, Marchive C, Kim SK, Meyer C, Sun Y, Wang W, Wang ZY (2016) TOR signaling promotes accumulation of BZR1 to balance growth with carbon availability in Arabidopsis . Curr Biol 26: 1854–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shin AY, Han YJ, Baek A, Ahn T, Kim SY, Nguyen TS, Son M, Lee KW, Shen Y, Song PS et al (2016) Evidence that phytochrome functions as a protein kinase in plant light signalling. Nat Commun 7: 11545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File