Abstract

In 2008, Ecuador underwent a major health reform with the aim of universal coverage. Little is known about the implementation of the reform and its perceived effects in rural parts of the country. The aim of this study was to explore the perceived effects of the 2008 health reform implementation, on rural primary health care services and financial access of the rural poor. A qualitative study using focus group discussions was conducted in a rural region in Ecuador, involving health staff, local health committee members, village leaders, and community health workers. Qualitative content analysis focusing on the manifest content was applied. Three categories emerged from the texts: (1) the prereform situation, which was described as difficult in terms of financial access and quality of care; (2) the reform process, which was perceived as top-down and lacking in communication by the involved actors; lack of interest among the population was reported; (3) the effects of the reform, which were mainly perceived as positive. However, testimonies about understaffing, drug shortages, and access problems for those living furthest away from the health units show that the reform has not fully achieved its intended effects. New problems are a challenging health information system and people without genuine care needs overusing the health services. The results indicate that the Ecuadorean reform has improved rural primary health care services. Still, the reform faces challenges that need continued attention to secure its current achievements and advance the health system further.

Keywords: health care reform, health services accessibility, qualitative research, rural health services, universal coverage

What do we already know about this topic?

Statistics concerning the 2008 Ecuadorian health reform, establishing universal health coverage, indicate that inhabitants in the poorer income quintiles financially benefited from the reform, but that there are still substantial costs involved, mainly for the purchase of pharmaceuticals and private medical consultations.

How does your research contribute to the field?

Little is known how the implementation of the health reform was actually perceived by the population it is intended to serve, in remote and rural areas of the country.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

In accordance with the theories in the Walt and Gilson model for health policy analysis, which besides the content of the health policy being analyzed also acknowledges the historical context in which a reform takes place and incorporates the process, the qualitative design of the study embeds for a deeper understanding of importance for the implementation of health care in a typical low- and middle-income country rural context.

Introduction

Universally accessible primary health care (PHC) was formally created with the declaration of Alma-Ata in 19781 and is now a crucial part of any health system. It is an approach to the achievement of both the sustainable development goals and Universal Health Coverage (UHC).2 The latter is defined as all people having access to needed health services without the risk of severe financial consequences.3 In Latin America, coverage-oriented reforms are being carried out to achieve UHC.4

For low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), the existence of health care systems based on UHC and the provision of reasonably accessible health care for remote, poor, marginalized, or for other reasons vulnerable populations has been found to be as crucial as challenging. Although abolition of user fees for health care services, sometimes also including free medicines, has been applied, examples from, for instance, Kenya and Uganda indicate that unofficial fees tend to replace the official ones after their abolition.5-8 Also, insufficient accessibility to UHC supported health care providers may force patients to seek other alternatives, although possibly resulting in catastrophic expenditure for the individual patient.9,10 Another important issue is the access to medicines, for which several studies have shown that abolition of user fees, especially when including drug expenditures, led to impaired access to drugs in general,6,11-12 whereas only a few studies have shown the opposite. Lack of sufficient knowledge and information of health care services in the population and among affected stakeholders is also described as an important obstacle to care in after implementation of UHC reforms.11-13

A recent Cochrane review of financial arrangements for health systems in low-income countries found that such studies rarely reported social outcomes, equity impacts, or undesirable effects.14 Another recent review of relevance for this study concluded that there is moderate evidence that new health insurance schemes in LMIC improve the health of the insured.15 Both reviews point to the importance of studies of implementation of health reforms and financing systems, such as our study.

Ecuador is the smallest of the Andean countries. In 2017, this multiethnic country had 16 million inhabitants, 13.2% of the urban population lived below the national poverty line, whereas the proportion in rural areas was 39.3%.16 Ecuador’s health system is characterized by multiple providers in the public and private sector, with little institutional coordination, a typical situation in Latin America.17,18 The two main public providers are the Ministry of Public Health (MPH) and the Ecuadorean Social Security Institute (Instituto Ecuatoriano de Seguridad Social [IESS]). Both are operating parallel systems of PHC (sub)centers, district, and regional hospitals. The rural population, mainly farmers, can enroll voluntarily in the Farmer’s Social Security (Seguro Social Campesino [SSC]), which is part of the IESS.

The country’s constitution from 1998 stated that “health is a right that must be guaranteed, promoted, and protected, and access to services must be uninterrupted.”19 This was basically not put into place,20 and health service coverage and quality were deficient.9,21 In the first decade of the 21st century, user fees and contributions to public health insurance increased,18,22 except for maternity and child care which was free due to legislation.18,23 However, Daniels et al.24 found evidence that some users were charged even for these services. In 2000, out-of-pocket health expenditure caused 11% of the nonpoor population to fall below the national poverty line for at least 3 months, and 57% of the total health revenue in 2004 was due to out-of-pocket expenditure.20

After the election of a new government in 2006, a constitutional reform, clearly aiming for UHC, took place in 2008. A groundbreaking change related to health was represented by article 362, which abolished user fees for governmental health services. Other articles in the constitution state the right to comprehensive health care based on PHC and that delivery of services shall be governed by principles of equity, quality, and efficiency.25

The reform defined a catchment population for health services and aimed to provide Universal Health Coverage with primary health centers and hospital services. Through renovation and construction, the reform put 47 hospitals and 74 health centers into operation, thereby increasing the use of health services by 300% between 2007 and 2016.26 The reform also introduced a capitation model for calculating financial needs of the facilities and merged all public funds for health services into one major fund, Fonde Nacional de Salud Ecuatoriano (FONSE).11 The reform set a very ambitious agenda but is been hampered by legal, political, and operational constraints.27

As user fees were removed and medicines and materials given for free, more health workers were deployed to rural centers, more supplies were frequently provided to the periphery, more control of health workers’ work presence was initiated, and the health information system was adjusted.9

Concerning the policy of free services since 2008, data have shown that the poorer income quintiles financially benefited from the reform, but that there are still substantial costs involved, mainly for the purchase of pharmaceuticals and private medical consultations.9

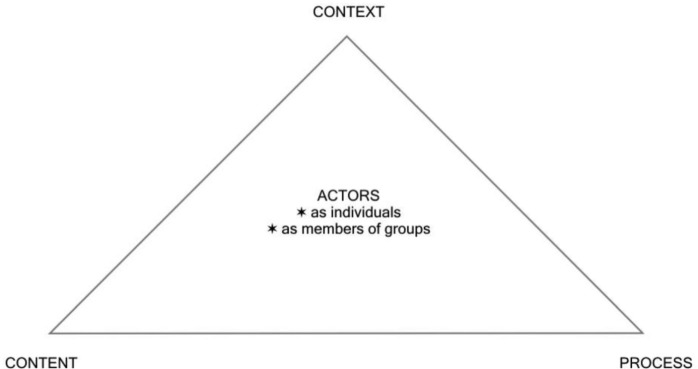

To analyze the highly complex process of health reform, different theories and frameworks have been proposed.28 One of these is Walt and Gilson’s model for health policy analysis (Figure 1).29 It acknowledges the historical context in which a reform takes place and incorporates the process as well as the actors in the analysis of the reform process, and as such it has been considered appropriate for the present study.

Figure 1.

Walt and Gilson’s health policy analysis model.

This study was carried out at an early stage of Ecuador’s health reform and at that time little was known on how the reform process was perceived by the community including patients, their families, and staff delivering health services. Still, it remains little known how health and well-being in rural Ecuador have been affected by the reform. A recent publication on the reform states that data on service quality are lacking.30

The aim of the present study was to explore how the implementation of the health reform was perceived by rural stakeholders and how they felt that rural PHC services, and in particular access to services for the rural poor, was affected.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in 2010 in a rural rainforest region in the northwestern lowland province of Esmeraldas in Ecuador. This is a population excluded from mainstream social, economic, cultural, or political life and can thus be defined as marginalized. The number of inhabitants was a few years earlier estimated to be around 5000.31 There are 30 scattered communities in the region. The central village is La Y de la Laguna (La Y) which has bus connection with the town Quinindé, about an hour’s drive away. The majority of this population are mestizo, some are African Ecuadorean. Official governance in the region is weak and basic infrastructure lacking. Traveling was, at the time of the study, mostly done by foot or mule on dirt tracks and could take up to 10 hours from the central village to the remotest settlements. The majority of the population in the area is poor and most inhabitants live of subsistence farming. At the edge of the region, a PHC subcenter from the SSC offered limited services to those 30% of the population who were insured.32 Furthermore, the region contained a MPH health post, staffed by an auxiliary nurse, and a PHC subcenter in the central village, which was run in a public-private partnership between a local health committee, the MPH, and an Ecuadorean nongovernmental organization (NGO). At the time of the study, the PHC subcenter was staffed by a doctor, a dentist, and a nurse on a yearly rotation under the medicatura rural program, a compulsory governmental program, whereby first-year physicians and other health professionals are sent to understaffed rural areas.33 Secondary care was provided in a district hospital 30 km away.

Study Design and Data Collection

A qualitative study was conducted using focus group discussions (FGDs), following standards described by Krueger and Casey.34,35 A collective tradition in the population, to deal with issues such as health care and other social issues through meetings and discussions, made FGDs appropriate.

Four FGDs were conducted with the health staff from the two MPH health units in the region, members of the local health committee board (the health committee), village leaders, and the region’s community health workers (CHWs). The participants acquired knowledge on the health reform either as patients or through contact with former patients as a result of their role in their communities. Health staff contributed with professional insights. All staff from the health units and all members of the health committee were invited. For each of the other two FGDs, inhabitants from nearby and far-off villages (in relation to the PHC subcenter) as well as females and males were grouped separately. Participants were chosen randomly from the 4 subgroups described above to have representation of all 4 qualities. A personal letter from the main author, delivered a few weeks before the scheduled FGD, invited all individuals. Confirmation was not always possible, given the lack of phones and the difficult geography. Of the 34 individuals invited, 28 participated in the FGDs. The ones who did not participate either had other duties or did not reply (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the FDG Participants.

| FGD | Invited (n) | Participants (M/F) (n) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health staff | 7 | 6 (4/2) | Paid staff: 2 medical doctors and 1 dentist (sent by the MoH from outside the region), 1 nurse, 1 laboratory technician, 1 auxiliary nurse (all living in the study region). 1 invitee abstained due to other duties. |

| Health committee | 7 | 5 (4/1) | Volunteers: 1 participant arriving 20 minutes before the end of the FGD. 1 invitee abstained due to other duties. 1 invitee did not reply |

| Village leaders | 10 | 8 (6/2) | Volunteers: 3 participants from villages distant to the PHC (2 women, 1 man), 5 from villages closer to the PHC (5 men). 2 invitees did not reply. |

| CHWs | 10 | 9 (4/5) | Volunteers: 4 participants from villages distant to the PHC (3 women, 1 man), 5 from villages closer to the PHC (2 women, 3 men). 1 invitee did not reply. |

Note. FGD = focus group discussion; CHW = community health worker; PHC = primary health care; M = male; F= female.

An introduction and question guide informed by literature35,36 and discussed between the authors was developed in Spanish. The introduction explained the aims of the research, the FGD, and practical issues. The question guide began with 2 introductory questions concerning when the participants first heard about the reform and what they knew about the reform before it was set in motion. The key question concerned the changes brought to the region by the reform and was illustrated by a hypothetical patient case, a 15-year-old named Juan with an infected leg wound, whose family did not currently have any money. The participants discussed what would have happened to Juan before the reform and after the reform. Finally, the participants were asked to give advice or suggestions to the Minister of Health.

The FGDs took place in a meeting room in the region’s PHC subcenter and were held in Spanish. The main author served as moderator in all FGDs. A foreign physician with good language skills assisted with practical details, observed interactions and nonverbal communication, and took notes. With the participants’ permission, the FGDs were digitally recorded. The discussions lasted between 101 and 140 minutes. Directly after the discussions, the moderator and the assistant checked the recording for completeness and discussed what could be learned from the FGD experience. Verbatim transcription was done by a native speaker and the transcription was cross-checked by the main author. As the aim was to collect data from different groups in the population, a predefined number of FGDs was performed and the issue of saturation was not applicable. Formal member check was not performed. Participants were given the possibility to provide feedback on the findings in a meeting in which the preliminary results were presented.

The main author is a cofounder of the PHC subcenter in the study region and involved with a NGO supporting it technically and financially. This does not imply any obstacle in this study as his role in the region is neutral regarding governmental health reform. Access to the study population would have been extremely difficult without the personal link to the region’s inhabitants. Distrust in outsiders, national as well as international, is widespread in the region due to uncertainty of landownership and the marginalization of the population.

Analysis

Qualitative content analysis according to Graneheim and Lundman was used to analyze the data.36 This method was found appropriate as it accounts for understanding and cooperation between the researcher and the participants. The method allows a certain degree of interpretation when approaching the text, however mainly the manifest content was included.36 Categories and subcategories were allowed to emerge in an inductive way from the texts. The texts were read and reread by the main author and meaning units, ie, constellations of words or statements that relate to the same central meaning, were identified. They were cross-checked and discussed with one of the coauthors (S.C.). The meaning units were then condensed and coded and the codes were sorted into categories and subcategories. To increase confirmability and ultimately also credibility, this entire process was discussed and adjusted with one of the coauthors (S.C.) until consensus was reached.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was received from the bioethics committee of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Oficio-CBE-001-2013). Written approval was granted by the NGO Fundación Naturaleza Humana Ecuador and the Farmers’ Health Committee for the El Páramo Region. Participation was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured and written informed consent was received from all participants before the FGDs.

Results

The results are presented according to categories and subcategories displayed in Table 2. Citations are provided to support the results. Additional information, to enhance understanding, appear in brackets.

Table 2.

Categories and Subcategories Emerging From the Analysis.

| CATEGORIES | Prereform situation | Reform process | Effects of the reform |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUBCATEGORIES | • Poor access and quality of PHC | • Obstacles in communication • Poor implementation of reform |

• Increased demand for health care services • Improved medical attendance • Increased administration • Financial effects for the population |

Note. PHC = primary health care.

Prereform Situation

Poor access and quality of PHC

The situation before the reform was described to be bad and nobody wished to return to the old system. It was mentioned that the prereform system lacked human resources, specialists, and medicines. Trust in the district hospital and the next level of care was low. Hospitals were perceived to be quite empty of patients because of the costs involved. In the FGD with village leaders, it was stated, “What they could have done, only waiting until he dies there [at home] or maybe someone would have mercy to give him a hand [with the money]” (Village leaders, participant 1). However, the PHC subcenter could at times have a high patient load, and patients had a good chance of being seen by a doctor. Even unpaid attendance to patients who had no money occurred. In general, demand for health services was lower compared with the postreform situation because of the costs involved. Free vaccinations and drugs existed in the child care program, but in the FGD with health committee members the free maternity program was seriously criticized:

When the [contraceptive] pill was there, ten patients came and they [the MPH] gave you for eight, they didn’t give you full stock. What a shame you have to buy it, and when she didn’t have the money she got pregnant. (Health committee, participant 1)

Reform Process

Obstacles in communication about the reform

The participants raised the issue of lack of communication from the government about the reform, and health staff also described a lack of democracy and decision-making powers. All had heard something about the changes but perceived this information to be deficient. It was mentioned that the government provided more information than previous governments, but the population lacked interest. Furthermore, access to radio and television was low. A village leader mentioned that the previous constitution was almost unknown to themselves and the general population: “We have almost no knowledge about the civil rights as Ecuadoreans, because we don’t know much about what law is. So, we do not penetrate the laws much and always leave it to the others, this is the disinformation.” Another village leader commented on knowledge about the new system: “They [the village population] are more or less forty to fifty percent informed that the medicines and the attendance is free of charge” (Village leaders, participant 1).

Preconceptions in the population were also found to complicate the communication about the services brought by the reform. Staff stated that people believed that paid attendance is of higher quality than free attendance. According to one participant in the health committee group, people believed that public hospitals were badly equipped and have no good doctors. Another member in that group said that free MPH drugs are thought not to be correctly constituted and that their quality is unreliable.

Poor implementation of reform

Health staff lamented about poor implementation of the reform, which caused conflicts when some households were reached while others were not aware of the services available. It was also perceived as a problem that information about the doctor’s absence at the PHC subcenter, and dates of arrival of vaccines and other utilities, did not reach the village population. Changes were perceived to be small and coming slowly. Village leaders claimed that the reform was implemented to the extent possible, but that some parts were not implemented due to irresponsible officials and neglect. Community health workers claimed that the government did not anticipate the increased demand for health services after the reform.

Effects of the Reform

Increased demand for health care services

After the reform, more patients were seeking care at the MPH health units and hospitals. This was linked to free services but could not always be met by available resources. The increasing influx of patients caused a high workload. Due to the heavy patient load, only a fraction could be seen during the day. A CHW stated in the FGD that “one has to be in the hospital at three o’clock in the morning to get an appointment” (CHWs, participant 1). A village leader stated,

I say there haven’t been changes, because the people of my community have come like three times, some pregnant ladies, and lately, the fourth time, they got attended . . . the fourth time they vaccinated them, therefore I say that there are no changes. (Village leaders, participant 2)

The high patient load caused a relative lack of drugs and shortage of appointments, leading to rivalry between patients as a CHW explained: “More people are coming and the coverage of the hospitals for more patients is lacking. And this is also happening here [in the health subcenter]” (CHWs, participant 2). Those who were unlucky at the PHC subcenter sought care elsewhere in the MPH system, the SSC or a private clinic or did not receive care. Staff mentioned that some people wanted free medicines without being sick.

All groups stated that there were more free drugs and materials in the MPH system after the reform, but that medicines and vaccines were not always available and that equipment needed better maintenance. In a FGD with village leaders it was stated,

Well, it’s free up to where the medicine exists for the disease. Because sometimes certain kinds of medicines are too few or for a rare disease there is no medicine. They give you the prescription so that you get [buy] it in a pharmacy. (Village leaders, participant 3)

Village leaders discussed this in detail and attributed the situation to lack of coordination by administrators, neglect by hospital and province directors, missed placement of orders from doctors, lack of population data, and patients coming to use services although they lived outside the region. All groups stated unanimously that more drugs and more equipment were needed.

In all FGDs, participants discussed a lack of staff due to training, free days, sickness, and a high workload. They complained about the lack of a permanent doctor who knows the patients. On the contrary, staff stated there were PHC (sub)centers without doctors and situations where one doctor had to work in several centers to try to provide cover. Village leaders felt that staff at times lacked professionalism.

Improved medical attendance

In most FGDs, it was agreed that the population received more care and better attendance after the reform was implemented. Health programs for certain population groups; the possibility of home visits for emergency patients; improvements in diagnostics, obstetric care, and dentistry; and a sharper focus on preventive services were mentioned as improvements. Evaluation of PHC (sub)centers by the MPH and supervision of the doctor’s presence were seen positively. More respect from health professionals toward traditional birth attendants and CHWs was perceived. It was appreciated that the population now had the right to officially denounce problems. Attitudes of PHC subcenter staff were perceived to be good and the regular evaluation of doctors was seen positively. Staff and village leaders said that there were no gender differences in case management.

Increased administration

All groups except the CHWs mentioned that the requirements for documentation had increased. This caused a high workload for the staff, time loss, long waiting time for patients, and sometimes even meant that patients were not attended to. Health staff lamented, “We have to struggle a lot in filling in the papers” (MPH staff, participant 1). Another staff member added,

One poses a questionnaire of questions . . . and people having left the nursery . . . “why are you asking me so many questions” [for example, on demography and medical background when enrolling a patient in a certain medical program] . . . without having a clear concept why this information is wanted. (MPH staff, participant 2)

The patient perspective was illustrated by a statement in the FGD with the health committee: “The doctor filling in the papers, filling in, filling in . . . , I see my record card, four patients before me, I get desperate . . . because now he won’t attend me” (Health committee, participant 2). On the contrary, health committee members valued the improved supervision linked to documentation.

Satisfaction among patients and staff

A general view on the reform was expressed by a health staff member: “Well, to be a patient now would be very difficult, but I would like to be a patient of the actual reform” (MPH staff, participant 3). Patients were satisfied when the doctor was present and attendance was free. All participants claimed that it was better to be a patient in postreform times. Trust in the PHC subcenter and in public hospitals increased after the reform. A CHW stated, “In my [village] they [the inhabitants] like the attendance” (CHWs, participant 3).

Staff and patients were dissatisfied with extensive documentation and staff were sorry for patients who had to wait. Staff expressed dissatisfaction with understaffing, lack of materials, low salaries, their own low status, and the low status of the PHC subcenter.

Financial effects for the population

In all FGDs, it was stated that drugs, medical, and dental services were free of charge when available. Failing this, sometimes people had to obtain prescribed drugs for charge, either locally or outside the region as a statement from a staff member illustrates: “There were patients with hypertensive crisis and there was no medicine and it was in the pharmacy [for charge]” (MPH staff, participant 4). Sale of free medicines, which is prohibited, was said to occur, although it was not clear whether the participants based this on hard evidence or on rumors. Queues at the public hospitals led patients to choose private clinics. How treatment failure at a public health unit can result in high costs is exemplified by the following statement from a health committee member: “Some pills that didn’t have the effect to cure the infection . . . and the man was paying around three hundred dollars, he carries [the debt] until now, because he had to take the girl to the private doctor” (Health committee, participant 3).

Improved financial access for the poor, who would usually seek care at MPH health units, was highlighted. Better off inhabitants preferred private providers, avoiding waiting time and extensive documentation. When costs were (thought to be) incurred, poor patients sometimes stayed away from the PHC subcenter. Alternatively, they had to sell their animals or get help from friends to be able to afford the services. If this was not possible and the PHC doctor was absent, (emergency) patients were not attended to and then had difficulties getting to a hospital. Those living in remote villages were mentioned having problems to get an appointment at the PHC subcenter or hospital as a CHW explained: “Yes, there is a lot of competition, the people queue in the break of dawn, . . . all those from the countryside who live far away, no matter what, have to look for a private doctor” (CHWs, participant 4).

Discussion

We explored how Ecuador’s 2008 health reform and its implementation was perceived by rural local stakeholders, and how the reform was perceived to affect performance of rural PHC and financial access for the poor. Walt and Gilson’s29 policy analysis model (figure 1) was used as a framework for the interpretation of findings, addressing context, process, and content of the health reform and its implementation, to be discussed accordingly. In the model, both patients (as users of health care services) and health workers (as providers of health care services) were viewed as actors influencing the interactions between the model axes.

Context

The context in which the reform took place can be broken down into the local situation, the current political situation, and the historical context. The prereform local situation of health services in the study region was unanimously perceived as poor and undesirable by all study participants. This forms the baseline for the interpretation of changes generated by the reform. The political context of the reform was shaped by substantial political changes implemented by a left-leaning government shortly after having been elected. The findings of this study suggest that many people were not familiar with the Ecuadorean constitution from 1998, which may partly explain their lack of interest in the actual reform. Disappointment with earlier promises of reforms that were never implemented may have contributed to this, as pointed out by De Paepe et al.37 In addition, other factors that may have influenced the findings, such as the population, the epidemiological situation, and the physical environment, had not changed substantially from a few years before the reform until this study took place.

Process

Decision making was perceived to be top-down without community or health staff involvement, which also has been reported from reforms elsewhere.5,38 Furthermore, insufficient information and communication with stakeholders and the population concerning the reform process was perceived in rural Ecuador as well as in several African countries.11,13 As health systems develop, governments must represent the interests of the entire population and hence should make efforts to reach all in reform processes in line with the principles of universal health coverage.3 At the same time, the population needs to have an interest in upcoming developments. This study found that interest to be limited, maybe related to the fact that the health policy introduced in 1998 remained largely unimplemented. Indications were found that even several years after the 2008 reform, some people did not seek governmental health services, merely because they were unaware of the reduced costs. Others, who knew about the reform, abstained from seeking care because they expected charges. The government’s responsibility to properly and continuously inform all citizens about their reforms cannot be overemphasized.3,38 Some of the confusion expressed could probably have been avoided by better coordination and communication from those responsible for implementation of the reform. Despite this, the findings suggested that trust in the public health system was slowly returning.

Content

Our study shows that the health services were free of charge, indicating that a major aim of the reform content was achieved. This is not always the case after fee abolition reforms, as shown by the experiences from Kenya.6 In other contexts, unofficial fees have replaced official ones after their abolition,5,7 a phenomenon however not reflected in the present study. The limited number of daily patient appointments and drugs put limitations on free services in rural Ecuador. This is in line with findings from a comparison between prereform and postreform national statistical data.9 Thus, out-of-pocket expenditure existed, despite the abolition of fees, when patients were forced to use private services or purchase drugs when they were unavailable in the public system. This type of expenditure was found to be an important feature of health financing also in postreform Uganda.8 Abolition of user fee policies should thus not be confused with a no-cost health care system. In Ecuador, those living far from a MPH health unit seemed to have a lower likelihood of receiving free MPH services than those living closer, a phenomenon seen also for other services, such as educational services during childhood.39 Unavailable or overcrowded services either left patients unattended or they turned to other providers. If insured at the SSC, people may have gotten treatment there. If not, private providers were the only option. This choice could involve catastrophic expenditure, as shown earlier,9,10 and by the example in the results section. A modification of the system, for example, to allow for reserved days or appointments for those living far away, is desirable to give them an equal chance of being seen by a public provider.

An important finding was the intermittent absence of staff and lack of drugs, indicating potential nonadherence to the aim of the reform to provide good quality health services for the health and well-being of all. In 2016, similar findings were reported from a study in the capital Quito.9 Reasons for these problems are multifactorial. The problem of irregular reform implementation has previously been reported from other countries.5,38 In addition, challenges like the lack of preparedness for increased health service demand, further complicated the situation in postreform Ecuador.

The findings of this study suggest that access to medicines improved post reform, even though drug shortages were reported. Similar developments were seen after the Ugandan reform in 2001.13,40 This is in contrast to other studies on abolition of user fees, when access to drugs generally decreased.11,6,12 Perceived reasons for drug shortages were supply problems due to failures in communication and coordination and increased demand. Similar findings have been reported from Mexico, Uganda, and Niger.12,13,41

Participants expressed concern about the extensive health information system, which reduced the time for patient care and even left some patients unattended. Patients felt annoyed by the many questions that had to be documented and some were said to avoid the public system if they could afford to do so. The staff were also troubled by the high administrative workload and the dissatisfied patients that they lamented not having enough time to attend to. These results are in line with qualitative findings in an urban setting.9 Similarly, less time for patients arose after health reforms in other Latin American countries.42 Documentation of health services is important, but when both patients and staff are overburdened with administrative work, policy makers need to reconsider the information systems. Simplified, smart, and easy to handle health information systems are urgently needed, in Ecuador and elsewhere.

Nevertheless, the effects of the reform on service quality, availability, and accessibility were mainly described as positive or moving in the right direction. This agrees with Guerra Villavicencio’s9 investigation from postreform Ecuador and experiences from similar reforms elsewhere.19,5,43 However, efforts must be made to reach and maintain the entire content of the health reform, to preserve the slowly returning trust in the public health system, documented in this study.

Actors

Health staff perceived a much higher level of changes caused by the reform than other groups, certainly related to their daily work in the changing system. In the postreform system, even healthy people are reported to attend health services, because they may get something for free, a phenomenon known as moral hazard.44 It leads to overcrowding of services by healthy individuals and decreases the likelihood of people in need getting seen by a health worker; and carries the risk of healthy individuals receiving unnecessary treatments.

Methodological Considerations

This study has some limitations that may have influenced the findings. Participants other than staff may have had difficulties distinguishing between governmental and nongovernmental services at the PHC subcenter. H Junior staff may have felt intimidated to freely express their opinions as senior staff was present. However, due to the limited number of staff, homogenous focus groups were not possible. Further insights on the topic could have been gained by also including patients. The risk of bias due to the main author’s role in the study region as described above was believed to be minor and is outweighed by the possibility to gain access to the involved individuals, which would otherwise most likely not have been possible.

Even though the present study has been carried out several years ago, its findings give insights in the perceived quality of rural health services. Furthermore, they are likely to be transferable to similar marginalized settings in postreform Ecuador and to other countries with similar conditions.

Conclusion

The findings from this study contribute to the ongoing debate on UHC policies in LMIC. Qualitative evaluations of UHC implementations from rural areas are rare, and the findings of this investigation may contribute to the advancement of global universal health coverage.

The top-down approach applied during the process of the Ecuadorean health reform, with insufficient communication to the implementers in the field, posed a problem. However, the health services examined in this study seemed to be moving toward the established aim of the reform related to PHC. Free attendance, improved quality, and increased trust in the system were the major perceived effects of the reform. Nonetheless, ongoing problems such as overcrowding of the system by healthy individuals were reported. The health information system was a burden on the staff and meant that some patients could not be attended to as they should have been. Such shortcomings need to be seriously addressed to further improve health and well-being and ensure the trustworthiness of the reform.

In conclusion, the results indicate that the Ecuadorean reform has improved rural PHC services, although facing challenges that need continued attention to secure its current achievements and advance the health system further.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nongovernmental organization Fundación Naturaleza Humana Ecuador for local support, and the La Y health subcenter staff and Dr. Michael von Schickfus for help with the focus groups and valuable comments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.E. made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article and gave final approval of the version to be published. S.C. and M.F. made substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article and gave final approval of the version to be published. T.F., A.C.B., and B.C.F. made substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data and revising the article critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics and Consent: Ethical approval was received from the bioethics committee of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Oficio-CBE-001-2013). Written approval was granted by the NGO Fundación Naturaleza Humana Ecuador and the Farmers’ Health Committee for the El Páramo Region. Participation was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured and written informed consent was received from all participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.E. was funded through the Centre for General Practice and Primary Health Care, County Council of Östergötland, Sweden, and a research grant through the Director of Studies Office, County Council of Östergötland, Sweden. All other authors received their normal salaries.

ORCID iD: Magnus Falk  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6688-3860

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6688-3860

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care September 6-12 Alma-Ata, USSR: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A, Palu T. Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the sustainable development goals. BMC Med. 2015;29(13):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carrin G, Mathauer I, Xu K, Evans DB. Universal coverage of health services: tailoring its implementation. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):857-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagstaff A, Dmytraczenko T, Almeida G, et al. Assessing Latin America’s progress toward achieving universal health coverage. Health Aff. 2015;34(10):1704-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ridde V, Morestin F. A scoping review of the literature on the abolition of user fees in health care services in Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chuma J, Musimbi J, Okungu V, et al. Reducing user fees for primary health care in Kenya: policy on paper or policy in practice? Int J Equity Health. 2009;8(8):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mubyazi GM, Bloch P, Magnussen P, et al. Women’s experiences and views about costs of seeking malaria chemoprevention and other antenatal services: a qualitative study from two districts in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2010;17(9):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basaza RK, Criel B, VanderStuyft P. Community health insurance amidst abolition of user fees in Uganda: the view from policy makers and health service managers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;4(10):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerra Villavicencio DP. Efectos de la política de gratuidad de los servicios Salud del MSP en el Ecuador. Periodo 2007-2014 [Effects of a Policy of Free Health Care Services by MSP in Ecuador. Period 2007-2014] [master’s thesis], Quito, Ecuador: Universidad San Francisco de Quito; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;12(362):111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilkinson D, Gouws E, Sach M, Karim SS. Effect of removing user fees on attendance for curative and preventive primary health care services in rural South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(7):665-671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morestin F, Ridde V. The Abolition of User Fees for Health Services in Africa: Lessons From the Literature. Montréal, Québec, Canada: Université De Montréal; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nabyonga-Orem J, Karamagi H, Atuyambe L, Bagenda F, Okuonzi SA, Walker O. Maintaining quality of health services after abolition of user fees: a Uganda case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;9(8):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiysonge CS, Paulsen E, Lewin S, et al. Financial arrangements for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erlangga D, Suhrcke M, Ali S, Bloor K. The impact of public health insurance on health care utilisation, financial protection and health status in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0219731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). Reporte de Pobreza y Desigualdad [Poverty and Inequality Report]. Quito, Ecuador: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muntaner C, Salazar RM, Rueda S, Armada F. Challenging the neoliberal trend: the Venezuelan health care reform alternative. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(6):I19-I24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pan American Health Organization. Health Systems Profile. Ecuador. Monitoring and Analysis of the Change and Reform Process. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pan American Health Organization. Health in the Americas: Ecuador. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baeza CC, Packard TG. Beyond Survival: Protecting Households From Health Shocks in Latin America. Washington, DC: Stanford University Press and the World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Figueroa Pico DCE. Demografía y epidemiología históricas en Ecuador (2002 - 2011) [Historic Demography and Epidemiology in Ecuador] [dissertation], Murcia, Spain: Universidad de Murcia; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vos R, Cuesta J, Léon M, et al. Reaching the Millennium Development Goal for Child Mortality: Improving Equity and Efficiency in Ecuador’s Health Budget (Working paper Series No. 411). The Hague, The Netherlands: ORPAS —Institute of Social Studies; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiriboga SR. Incremental health system reform policy—Ecuador’s law for the provision of free maternity and child care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32(2):80-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Daniels N, Flores W, Pannarunothai S, et al. An evidence-based approach to benchmarking the fairness of health-sector reform in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:534-540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Asamblea Constituyente. Constitución de la Républica del Ecuador [Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador]. Washington, DC: Asamblea Constituyente; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Espinosa V, Acunã C, de la Torre D., et al. La reforma en salud del Ecuador. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:1-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Villacrés T, Mena AC. Mecanismos de pago y géstion de recursos financieros para la consolidación del Sistema de Salud de Ecuador. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;40(2):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, Murray SF, Brugha R, Gilson L. “Doing” health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):308-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9(4):353-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Torres I, López-Cevallos DF. ¿Reforma de salud en Ecuador como modelo de éxito? Crítica al número especial de la Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública [Health reform in Ecuador as a successful model? Critique of the special issue of the Pan American Journal of Public Health]. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ordoñez Llanos G. Inequities and effective coverage: review of a community health programme in Esmeraldas, Ecuador [master’s thesis], Amsterdam, The Netherlands: University of Amsterdam; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eckhardt M, Forsberg BC, Wolf D, et al. Feasibility of community-based health insurance in rural tropical Ecuador. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;29(3):177-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cavender A, Alban M. Compulsory medical service in Ecuador: the physician’s perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(12):1937-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;11(358):483-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DePaepe P, EcheverriaTapia R, AguilarSantacruz E, Unger JP. Ecuador’s silent health reform. Int J Health Serv. 2012;42(2):219-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. James C, Hanson K, McPake B, et al. To retain or remove user fees? Reflections on the current debate in low- and middle-income countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2006;5(3):137-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paxson C, Schady N. Does money matter? The effects of cash transfers on child development in rural Ecuador. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2010;59(1):187-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burnham GM, Pariyo G, Galiwango E, Wabwire-Mangen F. Discontinuation of cost sharing in Uganda. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(3):187-195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Homedes N, Ugalde A. Twenty-five years of convoluted health reforms in Mexico. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ugalde A, Homedes N. Las reformas neoliberales del sector de salud: déficit gerencial y alienación del recurso humano en América Latina [Neoliberal reforms in the health care sector: managerial deficit and alienation of human resources in Latin America]. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17(3):202-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vargas I, Vázquez ML, Jané E. Equidad y reformas de los sistemas de salud en Latinoamérica [Equity and reforms of health care systems in Latin America]. Cad Saude Publica. 2002;18(4):927-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ekman B. Community-based health insurance in low-income countries: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(5):249-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]