Key Points

Question

How does parent-toddler social reciprocity differ when engaging in tablet-based reading compared with print book reading?

Findings

In this counterbalanced, laboratory-based, within-participants study of 37 parent-toddler dyads, parents and toddlers showed lower social reciprocity with tablet-based books compared with print books as evidenced by greater frequency of solitary body posture, social control, and intrusive behaviors occurring during the reading of tablet-based books.

Meaning

These findings suggest that parents and toddlers may find engaging in shared tablet-based experiences to be challenging.

This laboratory-based, within-participants study examines parent-toddler social reciprocity while reading enhanced and basic tablet-based books compared with print books.

Abstract

Importance

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends parent-child joint engagement with digital media, recent evidence suggests this may be challenging when tablets contain interactive enhancements.

Objective

To examine parent-toddler social reciprocity while reading enhanced (eg, with sound effects, animation) and basic tablet-based books compared with print books.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This within-participants comparison included 37 parent-toddler dyads in a counterbalanced crossover, video-recorded laboratory design at the University of Michigan from May 31 to November 7, 2017. The volunteer sample was recruited from an online research registry and community sites. Dyads included children aged 24 to 36 months with no developmental delay or serious medical condition, parents who were the legal guardians and read English sufficiently for consent, and parents and children without uncorrected hearing or vision impairments. Data were analyzed from October 18, 2017, through April 30, 2018.

Exposures

Reading an enhanced tablet-based book, a basic tablet-based book, and a print book in counterbalanced order for 5 minutes each.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Video recordings were coded continuously for nonverbal aspects of parent-toddler social reciprocity, including body position (child body posture limiting parental book access coded in 10-second intervals), control behaviors (child closing the book, child grabbing the book or tablet, parent or child pivoting their body away from the other), and intrusive behaviors (parent or child pushing the other’s hand away). Coding intracorrelation coefficients were greater than 0.75. Poisson regression was used to compare each outcome by book format.

Results

Among the 37 parent-child dyads, mean (SD) parent age was 33.5 (4.0) years; 30 (81%) were mothers, and 28 (76%) had a 4-year college degree or greater educational attainment. Mean (SD) age of children was 29.2 (4.2) months, 20 (54%) were boys, 21 (57%) were white non-Hispanic, and 6 (16%) were black non-Hispanic. Compared with print books, greater frequency of child body posture limiting parental book access (mean [SD], 7.9 [1.9; P = .01] for enhanced; 8.4 [1.8; P = .006] for basic), child closing the book (mean [SD], 1.2 [0.4; P = .007] for enhanced; 1.2 [0.5; P < .001] for basic), parent pivoting (mean [SD], 0.4 [0.2; P = .05] for enhanced; 0.9 [0.4; P = .004] for basic), child pushing parent’s hand (mean [SD], 0.6 [0.2; P < .001] for enhanced; 0.4 [0.2; P = .002] for basic), and parent pushing child’s hand (mean [SD], 1.7 [0.3; P < .001] for enhanced; 2.4 [0.5; P < .001] for basic) occurred while reading enhanced and basic tablet-based books. Child pivots occurred more frequently while reading basic tablet-based books than print (mean [SD], 1.0 [0.3] vs 0.3 [0.1]; P = .005).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, toddlers and parents engaged in more frequent social control behaviors and less social reciprocity when reading tablet-based vs print books. These findings suggest that toddlers may have difficulty engaging in shared tablet experiences with their parents.

Introduction

Mobile technology ownership and use have grown exponentially in recent years, with an almost ubiquitous presence in the daily lives of families.1,2,3 Among children 8 years and younger, 42% have their own tablet devices and 78% have a tablet device in the home.2 This shift in children’s digital media habits is illustrated by the displacement of the shared experience of television viewing2 by more individual and parallel use of mobile devices.4 The effects of mobile device use on children’s development are not completely understood, although excessive use of digital media has been associated with externalizing behaviors,5 greater risk for developmental delays,6 and poor sleep.7,8 Parents play an important role in moderating these outcomes,9 and prior evidence suggests that young children learn better from screen media (television and interactive apps) when parents view media with their children and help children meaningfully apply new knowledge to their lives.10,11,12,13,14 Therefore, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends time limitations on screen media in addition to parent and child joint media engagement in early childhood to support children’s learning and facilitate parent awareness of the content being viewed.7

However, a growing body of evidence suggests that parent-child social interactions occurring over digital media may not be as robust as interactions in other settings because audiovisual stimuli from digital media may distract from reciprocal dyadic interactions.15,16,17 These “serve-and-return” interactions are characterized by positive contingent engagement and respect for children’s autonomy compared with controlling or intrusive behaviors, which disrupt dyadic engagement.11,18,19 Such interactions can be conceptualized as social reciprocity and provide context for parent-child coregulation, forming the basis for children’s social-emotional and cognitive development.20 Previous studies have shown less parent-infant social reciprocity when dyads play with digital toys, such as a baby laptop, compared with traditional toys and books.21 Observational and laboratory-based studies occurring during mealtime have found that when parents’ attention is engaged with their mobile device, they initiate fewer verbal and nonverbal social bids toward their children,22,23 possibly owing to the visually salient design features that may capture the parent’s attention and reduce their responsiveness toward children.24

In recently published work,25 we found that parent-toddler verbal interactions and collaborative reading behaviors were less frequent when engaging in tablet-based books with and without interactive enhancements (eg, hot spots, sound effects) compared with print books. We surmised that audiovisual distractors and children’s conceptualization of tablets as individually used4 may have led to decreased reading quality, verbal exchanges, and responsiveness, resulting in less social reciprocity.25

Although prior work has characterized parent-child reciprocity during free play,26,27 only 2 studies have considered this construct with a focus on nonverbal behaviors during tablet-based play.15,28 Hiniker and colleagues15 examined differences in play interactions around traditional toys and tablets among 15 preschool-aged children and their parents. Through qualitative analysis, they observed that children often created a solitary space around the tablet that limited parents’ access to it.15 Particularly when playing fast-paced apps, children were less responsive to parent bids, and some parents exhibited intrusive or controlling behaviors (eg, increasing directives and questions, touching the tablet while child was playing). Another study describing parent-child body posture while reading print and tablet-based books28 found that children frequently took a head-down solitary position during tablet-based reading compared with print reading, which limited parents’ ability to view the screen and led to parent “shoulder surfing” to engage in the activity. These studies suggest that design affordances of the tablet (ie, handheld, individually used) or interactive media (ie, high visual salience, positively reinforcing)24,29,30,31 may limit parent-child joint media engagement and that reclusive body posture may be an important indicator of social reciprocity in this context; however, these findings were qualitative and used small samples.15,28

Therefore, this study aimed to examine differences in parent-toddler social reciprocity—defined as nonverbal behaviors such as body position, control, and intrusive behaviors that are parent-child regulatory mismatches that impede reciprocity—during reading of enhanced and basic tablet-based books compared with print books. We chose a book-reading paradigm for examining these aspects of joint media engagement around tablets because social interactions during book reading have been well characterized, and controlling or intrusive behaviors during print book reading have been associated with lower child engagement and more insecure or disorganized attachment relationships.32,33 Manipulating book format (ie, tablet vs print) and interactivity (ie, enhanced vs basic tablet book) allowed tight experimental control to test our hypotheses. We examined toddlers because they may be particularly susceptible to visually salient and behaviorally reinforcing interactive design due to their immature executive functioning.34 This developmental period is also characterized by emerging autonomy and self-direction, which may make shared tablet use more challenging. We hypothesized that parents and children would show lower social reciprocity while reading basic and enhanced tablet-based books compared with print books, characterized by (1) more child solitary body posture, (2) higher frequency of child and parent control behaviors (closing the book, grabbing the book, moving the body with the book), and (3) higher frequency of child and parent intrusive behaviors (hand pushing).

Methods

Study Design

We conducted an experimental laboratory study consisting of video-recorded free play, a reading paradigm that involved a counterbalanced book protocol (each dyad reading 1 enhanced tablet-based, 1 basic tablet-based, and 1 print book), and surveys, with a duration of 75 minutes. This paradigm was chosen because of the well-studied effects of promoting parent-child joint engagement and positive body language behaviors in reading interactions32,35,36 and for tight control over the design affordances of these objects (different levels of enhancements in tablet-based books in addition to comparison with print). After participation, parents were compensated $50. The institutional review board of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, approved this study. Parents provided written informed consent.

Participants

Data were collected from May 31 through November 7, 2017. As previously described,25 we recruited 37 parent-toddler dyads from the University of Michigan online research registry (UMhealthresearch.org) and community-based settings, including pediatrician offices and child-care and community centers. Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) child age of 24 to 36 months, (2) no child developmental delay or serious medical condition, (3) parent ability to read English sufficiently to provide consent, (4) parent as legal or physical custodial guardian, and (5) no uncorrected hearing or vision impairments in the parent or the child.

Procedure

The laboratory approximated a living room, with couches, 3 books in boxes (2 tablet books and 1 print book) placed out of children’s reach, a 1-way mirror, and video cameras. Participants first completed a 5-minute video-recorded free play with nondigital toys, followed by a random counterbalanced, preassigned reading activity of the enhanced tablet-based book, basic tablet-based book, and print book. The reading protocol consisted of a preassigned, random sequential reading activity of an enhanced tablet-based book, basic tablet-based book, and print book occurring in a counterbalanced fashion in 1 of 6 total book format permutations. A total of 6 different book format permutations included (1) enhanced-basic-print, (2) enhanced-print-basic, (3) basic-enhanced-print, (4) basic-print-enhanced, (5) print-basic-enhanced, and (6) print-enhanced-basic. Within each book format permutation, the order of 3 different book titles was counterbalanced, achieving a total of 36 unique permutations. All participants read the same 3 books, but not all books were read in the same format or order across participants. Parents received instructions to complete each book sequentially as prompted for 5 minutes each.

Book Formats

Three Mercer Mayer Little Critter books (Just Grandma and Me, All By Myself, and Just a Mess) were chosen owing to similar length, reading difficulty, and availability in 3 formats. Print books were 8 × 8-inch softcover. Basic and enhanced tablet-based books were preloaded on a 10-inch Samsung Galaxy tablet computer (Galaxy; Samsung). Basic tablet-based book capabilities allowed for swiping to turn pages and tapping illustrations to produce visual appearance of words, without autonarration or sound effects. Enhanced tablet-based books contained audiovisual hot spots with interactive animation and sound effects. Tapping most pictures resulted in appearance and narration of the word (eg, tapping a baseball picture resulted in the appearance and narration of the word baseball). Tapping other pictures or turning a page produced a sound effect (eg, tapping a dog would produce the sound of a dog panting; turning the page to a beach produced sounds of ocean waves). Parents received instruction to select “read it myself” such that the tablet-based book was not narrating the book text; tapping and holding down an individual sentence in the enhanced tablet-based book would narrate that text, but this feature was only briefly used by 2 dyads.

Survey Measures

Parents completed surveys regarding covariates for potential inclusion in statistical models, including demographic information (parent’s age, sex, educational attainment, household income, race/ethnicity, relationship to child, and marital status; child’s age, sex, race/ethnicity, and prematurity) and standardized measures of child language, social-emotional development, and digital media use practices. The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory–Short Form assessed toddler language development using a 100-word validated,37 reliable38 vocabulary checklist generating an age-dependent percentile score for expressive vocabulary (range, 1-99, with higher scores indicating more expressive vocabulary).24

The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment is a validated,39 reliable25 42-item questionnaire screening for child social-emotional problems, with parent-rated items on a 3-point Likert scale generating Problem (range, 0-14, with higher scores indicating more social-emotional problems [Cronbach α = .68]) and Competence (range, 14-22, with higher scores indicating more competence [Cronbach α = .58]) subscales. Standardized questions assessed frequency of digital media use by the child at home (including tablet, smartphone, and electronic book) and parental mediation strategies (instructive, restrictive, and coviewing).40

Coding Parent-Toddler Nonverbal Interactions

Social reciprocity indicators were coded from the videos (Table 1); all intercorrelation coefficients were greater than 0.75. We considered solitary space as an indicator of lower social reciprocity based on previous observations that children adopted solitary postures that excluded parents in tablet-based contexts, reducing the ease of reciprocal serve-and-return interactions.15,28 We coded for the presence of solitary space in 10-second intervals, defined as child body posture limiting ease of parental book access. We coded frequency of child and parent control and intrusive behaviors (counts) across a 5-minute interval based on prior work on dyad nonverbal behaviors (eg, pulling the book away,33 pushing the other’s hand away32) during shared book reading.32,33 Control behaviors included the child closing the book, the child grabbing the book or tablet, and the child or the parent pivoting their body away from the other while holding the book or tablet. Intrusive behaviors included the child or the parent pushing the other’s hand away. The parent closing and grabbing the book or tablet occurred too infrequently to code reliably. The 5-minute free-play session was coded for shared positive affect, which we examined as a potential covariate but was not found to improve model fit. Two undergraduate students blinded to the hypothesis coded the videos for reliability with a Cohen κ of at least 0.70 (20% of videos were double-coded to ensure no coder drift).

Table 1. Coding Scheme.

| Behavior | Coding Definition | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Solitary space | Child creates a space that interfered with a parent’s ability to easily view or access the book | 0.98 |

| Child closing (control behavior) | Child closes the book physically by pressing the home button or escaping out of the book | 0.89 |

| Child grabbing (control behavior) | Child grabs the book | 0.81 |

| Child pivoting (control behavior) | Child turns their body physically away from the parent with the book in hand | 0.79 |

| Parent pivoting (control behavior) | Parent turns their body physically away from the child with the book in hand | 0.86 |

| Child pushing parent hand (intrusive behavior) | Child moves the parent’s hand away from the book | 0.78 |

| Parent pushing child hand (intrusive behavior) | Parent moves the child’s hand away from the book | 0.94 |

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from October 18, 2017, through April 30, 2018. We conducted Poisson regression using the Proc Genmod comparing each behavioral outcome by book format. Given occasional variation in reading duration, total elapsed time was adjusted. All models included a repeated-measures statement to allow within-participants comparison of behavioral outcomes by book format. Covariates in final models with 2-sided P < .05 were included to improve model fit (eg, order of book presentation, parent income, race/ethnicity, child sex, and MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory–Short Form or Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment score). Analyses were completed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

As shown in Table 2, the mean (SD) age of children was 29.2 (4.2) months; of parents, 33.5 (4.0) years. Among the parents, 30 (81%) were mothers and 7 (19%) were fathers, 28 (76%) had a 4-year college degree or greater educational attainment, and 33 (89%) were married. Of the children, 20 (54%) were boys and 17 (46%) were girls, 21 (57%) were white non-Hispanic, 6 (16%) were black non-Hispanic, and 10 (27%) were other race/ethnicity.

Table 2. Participant Characteristics.

| Study Sample | Participant Data (n = 37)a |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | |

| Child, mo | 29.2 (4.2) |

| Parent, y | 33.5 (4.0) |

| Parent relationship to child | |

| Mother | 30 (81) |

| Father | 7 (19) |

| Child sex | |

| Male | 20 (54) |

| Female | 17 (46) |

| Child race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 21 (57) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6 (16) |

| Hispanic or other | 10 (27) |

| Parent educational attainment | |

| Some college courses | 4 (11) |

| 2-y College degree | 5 (14) |

| 4-y College degree | 14 (38) |

| More than 4-y college degree | 14 (38) |

| Parent marital status | |

| Single | 4 (11) |

| Married | 33 (89) |

| Child has used tablet to read a book | |

| Almost never | 23 (62) |

| Rarely | 2 (5) |

| Occasionally | 4 (11) |

| Often | 6 (16) |

| Most of the time | 2 (5) |

| Daily time spent reading books together | |

| None | 8 (22) |

| <30 min | 16 (43) |

| 30 min to 1 h | 9 (24) |

| 1-2 h | 3 (8) |

| 3-4 h | 1 (3) |

| CDI percentile, mean (SD)b | 52.9 (33.4) |

| BITSEA subscale score, mean (SD) | |

| Problemc | 6.7 (3.8) |

| Competenced | 19.1 (2.2) |

| Mediation score, mean (SD) | |

| Instructivee | 15.5 (3.4) |

| Restrictivef | 15.5 (3.1) |

| Coviewg | 15.8 (3.0) |

Abbreviations: BITSEA, Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment; CDI, MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory–Short Form.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of participants. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Scores range from 1 to 99, with higher scores indicating more expressive vocabulary.

Scores range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating more social-emotional problems.

Scores range from 14 to 22, with higher scores indicating more competence.

Scores range from 8 to 20, with higher scores indicating more mediation.

Scores range from 11 to 20, with higher scores indicating more mediation.

Scores range from 7 to 20, with higher scores indicating more mediation.

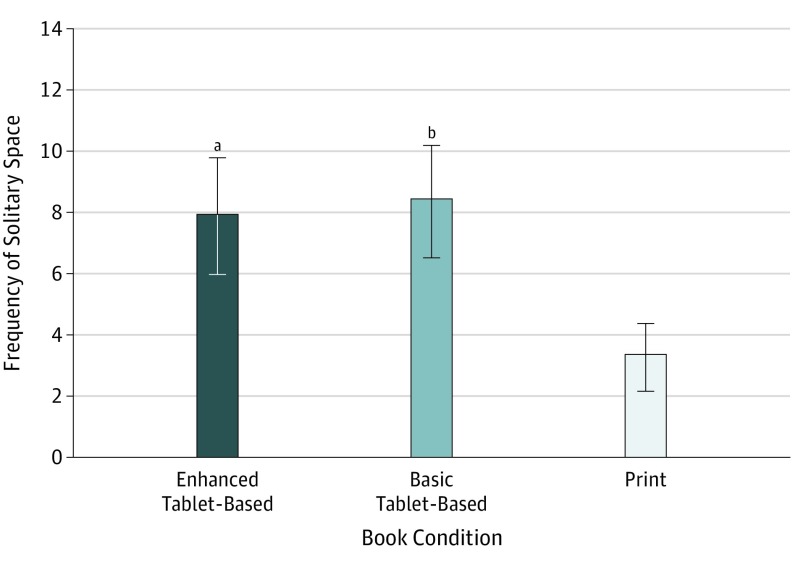

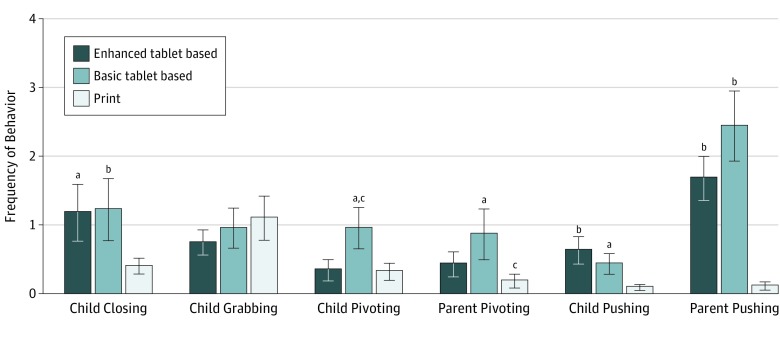

Compared with print books (mean [SD] frequency, 3.3 [1.1]), children demonstrated more solitary space during enhanced (mean [SD] frequency, 7.9 [1.9]; P = .01) and basic (mean [SD] frequency, 8.4 [1.8]; P = .006) tablet-based book conditions (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 2, children generally exhibited more control behaviors over enhanced or basic tablet-based books compared with print books. Compared with when reading print books (mean [SD] 0.4 [0.1]), children exhibited higher frequency of closing the book when reading enhanced (1.2 [0.4]; P = .007) and basic (1.2 [0.5]; P < .001) tablet-based books. There were no differences in book or tablet grabs by book format type. Compared with the basic tablet-based book (mean [SD] frequency, 1.0 [0.3]), children exhibited fewer pivot behaviors with the enhanced tablet-based and print books (mean [SD] frequency for both, 0.3 [0.1]; P = .03 for basic vs enhanced; P =.005 for basic vs print).

Figure 1. Results of Child Solitary Space.

Book conditions include enhanced tablet-based, basic tablet-based, and print. Data are expressed as mean (SD, denoted with error bars).

aP < .05 compared with print book condition.

bP < .01 compared with print book condition.

Figure 2. Results of Child and Parent Discrete Behaviors.

Book conditions include enhanced tablet-based, basic tablet-based, and print. Data are expressed as mean (SD, denoted with error bars).

aP < .01 compared with print book condition.

bP < .001 compared with print book condition.

cP < .05 compared with enhanced tablet-based book condition.

Parents likewise exhibited more control behaviors over tablet-based books compared with print books (see Figure 2). Parents exhibited more pivot behaviors during the enhanced tablet-based book condition (mean [SD] frequency, 0.4 [0.2]; P = .05) or the basic tablet-based book condition (mean [SD] frequency, 0.9 [0.4]; P = .004) compared with print books (mean [SD] frequency, 0.2 [0.1]).

Similarly, intrusive behaviors were greater for children and parents during either tablet-based book condition compared with print. Children exhibited a higher frequency of pushing the parent’s hand away during the enhanced (mean [SD] frequency, 0.6 [0.2]; P < .001) and the basic (mean [SD] frequency, 0.4 [0.2]; P = .002) tablet-based book conditions compared with the print book (mean [SD] frequency, 0.1 [0.04]). Compared with the print book (mean [SD] frequency, 0.06 [0.1]), the parent pushed the child’s hand away more frequently during enhanced (mean [SD] frequency, 1.7 [0.3]; P < .001) and basic (mean [SD] frequency, 2.4 [0.5]; P < .001) tablet-based book conditions.

Discussion

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends coviewing when engaging in mobile devices—including tablets—by parents and young children, little research has examined how interpersonal dynamics might change when interacting over tablets. To address this gap, we used a book-reading paradigm to examine differences in nonverbal social reciprocity while reading tablet-based vs print books. The high frequency of child solitary body posture, parent-child control behaviors, and intrusiveness during tablet-based book reading compared with print suggests that it may be challenging for dyads to engage in shared experiences over tablets because it may interfere with parent-child social reciprocity, particularly during book reading.

One way that tablet design may affect parent-child social reciprocity is by promoting more solitary body orientation in children.15,41 This orientation may reflect the ways in which parents and children use tablets and other mobile devices at home, in a solitary fashion. Domoff and colleagues4 analyzed home audio recordings from 75 families with young children and found that mobile media is often used in parallel rather than shared. Parents have described relishing the independence that children have when using tablets and mobile devices, pride that children are self-sufficient, and the peace afforded by children’s independent tablet use, each of which may be viewed as a benefit.42 Nonetheless, creation of solitary space may inhibit children’s social responsiveness, joint attention, and parental ability to scaffold, which are all important in children’s learning.11,18,32,33,43,44,45

Social reciprocity during parent-child activities lays the groundwork for social competence in future relationships; greater parent-child social reciprocity is associated with greater reciprocity with peers,46 whereas negative reciprocity with parents is associated with greater expressed negative affect with peers.46,47 Importantly, social reciprocity is influenced not just by the qualities of the parent-child dyad but also by affordances of play materials. Previous studies have found that digital toys, such as an infant toy cell phone or infant laptop, may yield lower parent verbalizations and conversational turns than traditional toys or books.21 We found that nonverbal control and intrusive behaviors aimed at managing possession of the tablet were more frequent around tablets than print books. Children closed the book application frequently, possibly to escape the electronic book, to look for other apps, or by accident. This situation interfered with the book reading experience, and parents frequently redirected their children to reopen the book. During tablet-based book conditions, children did not appear to want their parents to touch the tablet and engaged in pivoting and intrusive hand-pushing behaviors to control the tablet. Children may have viewed the tablet as a highly desirable object that may be limited at home and therefore exhibited controlling and intrusive behavior. Another explanation is that children may be accustomed to engaging with tablets independently or may not previously have experience using an electronic book, so it may not feel natural to share it with an adult4; however, adjusting for parent-reported mediation (ie, restricting and coviewing) practices and children’s previous electronic book use did not alter our results. Finally, the child’s attention may be drawn to audiovisual stimuli, making it more challenging to respond to parent bids. The tablet-based books chosen for this study had a relatively low number of enhancements and may not reflect how children would interact with highly gamified apps that are prevalent.31 Nonetheless, our findings are similar to previous results showing that children may have difficulty transitioning away from highly engaging devices.48

We observed a higher frequency of parental control and intrusive behaviors during tablet book conditions, likely in response to child behaviors. Parents were more likely to pivot their body to move the tablet away and gain control of the experience, similar to previous work in toddlers and older children showing that parental mediation strategies tended to be restrictive and reactive.4 Such restriction and behavioral control interactions appeared to detract from rich language exchange around the reading activity, as we found in a prior analysis.25 Parents may have been trying to engage in the reading experience as they would with a traditional book by preventing their child’s tapping and swiping behaviors. Prior work has shown that parental intrusiveness has been associated with negativity and reduced dyadic mutuality among toddlers49 and lower verbal and perceptual cognition among preschoolers.50

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine the social reciprocity and nonverbal indicators toddlers and parents exhibit when interacting around tablets. Strengths include a counterbalanced design that inherently controlled for family characteristics that might influence interactional style. We chose a commercially based book app, so our results are more ecologically valid than previous laboratory-based experiments that created their own electronic books.51,52 Another contribution of this study is objective examination of novel aspects of parent mediation, such as conflicts over device possession and solitary space, that are not reflected in self-reported parent mediation measures.40

Several limitations are worthy of mention. Our sample was small, highly educated, and predominantly married; laboratory-based observation may limit generalizability to the home; and choice of a low-enhancement app may underestimate the influence of interactive enhancements on parent-child behavior. Social reciprocity is just 1 facet of the interaction occurring over tablets. We acknowledge other potential benefits to tablet-based play for older children depending on the educational content of apps used.53,54 Future work should include understanding whether parents exhibit less autonomy support and more control around media use compared with other play and what influence this has on children’s play skills, media use, and social-emotional development over time.

Conclusions

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends coviewing when using mobile devices, doing so may be challenging for parents and toddlers to accomplish owing to tablet design affordances. Tablets increased solitary space, control behaviors, and intrusiveness in toddlers and parents in this study, which may interfere with the types of parent-child play interactions shown to improve executive functioning and self-regulation, such as autonomy support and social reciprocity. Technology designers may wish to consider a design that promotes positive shared experiences (eg, apps facilitating taking turns and collaboration). Pediatric health care professionals may wish to counsel parents that, if it is difficult to engage with children around tablets, they consider making times for shared viewing of other media platforms (eg, movie nights), using apps designed for shared use, and making time for play with traditional toys that encourage social reciprocity.

References

- 1.Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, et al. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1044-1050. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rideout V. The Common Sense census: media use by kids age zero to eight. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-kids-age-zero-to-eight-2017. Published 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- 3.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Generation M2: media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED527859.pdf. Published January 20, 2010. Accessed November 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domoff SE, Radesky JS, Harrison K, Riley H, Lumeng JC, Miller AL. A naturalistic study of child and family screen media and mobile device use. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(2):401-410. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1275-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radesky JS, Silverstein M, Zuckerman B, Christakis DA. Infant self-regulation and early childhood media exposure. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1172-e1178. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madigan S, Browne D, Racine N, Mori C, Tough S. Association between screen time and children’s performance on a developmental screening test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):244-250. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radesky J, Christakis D, Hill D, et al. Media and young minds. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162591. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter B, Rees P, Hale L, Bhattacharjee D, Paradkar MS. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1202-1208. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelsohn AL, Berkule SB, Tomopoulos S, et al. Infant television and video exposure associated with limited parent-child verbal interactions in low socioeconomic status households. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(5):411-417. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vygotsky LS. Zone of proximal development In: Cole M, John-Steiner V, Scribner S, Souberman E, eds. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978:79-91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds, I: aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory: an expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;130(3):201-210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.3.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkorian HL, Choi K, Pempek TA. Toddlers’ word learning from contingent and noncontingent video on touch screens. Child Dev. 2016;87(2):405-413. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkorian HL, Wartella EA, Anderson DR. Media and young children’s learning. Future Child. 2008;18(1):39-61. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Psouni E, Falck A, Boström L, Persson M, Sidén L, Wallin M. Together I can! joint attention boosts 3- to 4-year-olds’ performance in a verbal false-belief test. Child Dev. 2018;90(4):35-50. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiniker A, Lee B, Kientz JA, Radesky JS Let’s play! digital and analog play between preschoolers and parents. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; April 21-26, 2018; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radesky JS, Eisenberg S, Kistin CJ, et al. Overstimulated consumers or next-generation learners? parent tensions about child mobile technology use. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(6):503-508. doi: 10.1370/afm.1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radesky JS, Schumacher J, Zuckerman B. Mobile and interactive media use by young children: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):1-3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocissano L, Slade A, Lynch V. Dyadic synchrony and toddler compliance. Dev Psychol. 1987;23(5):698-704. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sameroff A. Transactional models in early social relations. Hum Development. 1975;18(1-2):65-79. doi: 10.1159/000271476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yogman M, Garner A, Hutchinson J, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Communications and Media . The power of play: a pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20182058. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sosa AV. Association of the type of toy used during play with the quantity and quality of parent-infant communication. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(2):132-137. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radesky J, Miller AL, Rosenblum KL, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, Lumeng JC. Maternal mobile device use during a structured parent-child interaction task. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(2):238-244. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radesky JS, Kistin CJ, Zuckerman B, et al. Patterns of mobile device use by caregivers and children during meals in fast food restaurants. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e843-e849. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogg BJ. A behavior model for persuasive design. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology; April 26-29, 2009; Claremont, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munzer TG, Miller AL, Weeks HM, Kaciroti N, Radesky J. Differences in parent-toddler interactions with electronic versus print books. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20182012. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman R. The relational basis of adolescent adjustment: trajectories of mother-child interactive behaviors from infancy to adolescence shape adolescents’ adaptation. Attach Hum Dev. 2010;12(1-2):173-192. doi: 10.1080/14616730903282472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingersoll B. Teaching imitation to children with autism: a focus on social reciprocity. J Speech Lang Pathol Appl Behav Anal. 2007;2(3):269-277. doi: 10.1037/h0100224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuill N, Martin AF. Curling up with a good e-book: mother-child shared story reading on screen or paper affects embodied interaction and warmth. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1951. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlov PI. Conditioned reflexes: an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Ann Neurosci. 2010;17(3):136-141. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidron B. Disrupted childhood: the cost of persuasive design. https://5rightsfoundation.com/static/5Rights-Disrupted-Childhood.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- 31.Meyer M, Adkins V, Yuan N, Weeks HM, Chang Y-J, Radesky J. Advertising in young children’s apps: a content analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(1):32-39. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bus AG, Belsky J, van Ijzendoom MH, Crnic K. Attachment and bookreading patterns: a study of mothers, fathers, and their toddlers. Early Child Res Q. 1997;12(1):81-98. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(97)90044-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frosch CA, Cox MJ, Goldman BD. Infant-parent attachment and parental and child behavior during parent-toddler storybook interaction. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2001;47(4):445-474. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2001.0022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlson SM, Mandell DJ, Williams L. Executive function and theory of mind: stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Dev Psychol. 2004;40(6):1105-1122. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuckerman B. Promoting early literacy in pediatric practice: twenty years of Reach Out and Read. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1660-1665. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendelsohn AL, Cates CB, Weisleder A, et al. Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dale PS. The validity of a parent report measure of vocabulary and syntax at 24 months. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34(3):565-571. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3403.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordahl-Hansen A, Kaale A, Ulvund S. Inter-rater reliability for the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory: parent and preschool teacher ratings of children with childhood autism. Res Autism Spectrum Disord. 2013;7(11):1391-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karabekiroglu K, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Rodopman-Arman A, Akbas S. The clinical validity and reliability of the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33(4):503-509. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valkenburg PM, Krcmar M, Peeters AL, Marseille NM. Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “instructive mediation,” “restrictive mediation,” and “social coviewing”. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1999;43(1):52-66. doi: 10.1080/08838159909364474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeBruin-Parecki A. Let’s Read Together: Improving Literacy Outcomes With the Adult-Child Interactive Reading Inventory (ACIRI). Baltimore, MD: Brooks Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radesky JS, Kistin C, Eisenberg S, et al. Parent perspectives on their mobile technology use: the excitement and exhaustion of parenting while connected. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37(9):694-701. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss RS. The attachment bond in childhood and adulthood In: Parkes CM, Hinde JS, Marris P, eds. Attachment Across the Life Cycle. Regensburg, Germany: Routledge; 2006:74-84. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. Responsive parenting: establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(4):627-642. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergin C. The parent-child relationship during beginning reading. J Literacy Res. 2001;33(4):681-706. doi: 10.1080/10862960109548129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldman R, Gordon I, Influs M, Gutbir T, Ebstein RP. Parental oxytocin and early caregiving jointly shape children’s oxytocin response and social reciprocity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(7):1154-1162. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim KJ, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Elder GH Jr. Parent-adolescent reciprocity in negative affect and its relation to early adult social development. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(6):775-790. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.6.775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parish-Morris J, Mahajan N, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Collins MF. Once upon a time: parent-child dialogue and storybook reading in the electronic era. Mind Brain Educ. 2013;7(3):200-211. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ispa JM, Fine MA, Halgunseth LC, et al. Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups. Child Dev. 2004;75(6):1613-1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pomerantz EM, Eaton MM. Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: transactional socialization processes. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(2):174-186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strouse GA, Ganea PA. Toddlers’ word learning and transfer from electronic and print books. J Exp Child Psychol. 2017;156:129-142. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strouse GA, Ganea PA. Parent-toddler behavior and language differ when reading electronic and print picture books. Front Psychol. 2017;8:677. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Outhwaite LA, Gulliford A, Pitchford NJ. Closing the gap: efficacy of a tablet intervention to support the development of early mathematical skills in UK primary school children. Comput Educ. 2017;108:43-58. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neumann MM. Young children’s use of touch screen tablets for writing and reading at home: relationships with emergent literacy. Comput Educ. 2016;97:61-68. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]