Key Points

Question

What is the explanation for multiple uveal melanomas arising in the same eye?

Findings

In this case series, 4 patients were found to have unilateral multifocal uveal melanomas without ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis. In all cases, the initial and subsequent tumors exhibited class 2 gene expression profiles and identical driver mutations.

Meaning

Cases of unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma in the absence of melanocytosis may represent intraocular metastasis, which may be associated with increased risk for systemic metastasis.

This clinical case series evaluates the pathogenesis of unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma in 4 affected individuals.

Abstract

Importance

There has been speculation on the pathogenesis of unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma, but there remains no convincing explanation. Genetic analysis suggests that unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma may represent intraocular metastasis with increased risk of systemic metastasis.

Objective

To evaluate the pathogenesis of unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This clinical case series was conducted in tertiary academic ocular oncology referral centers and included patients with unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Gene expression and mutation profiling of tumor samples.

Results

Four patients (all male; age range, 54-77 years) who were diagnosed with uveal melanoma were treated with plaque brachytherapy, and subsequently developed a second discrete uveal melanoma in the same eye were included. None demonstrated ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis. All 8 tumors available for analysis exhibited class 2 gene expression profiles. In all 4 cases, the initial and subsequent tumors were available for targeted DNA sequencing and identical driver mutations were present in both tumors. Data were collected from September 2015 to August 2018.

Conclusions and Relevance

Unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma in the absence of ocular melanocytosis appears to occur preferentially in tumors with the class 2 gene expression profile and a BRCA1-associated protein 1 gene (BAP1) mutation. The presence of identical BAP1 mutations in multiple tumors in the same eye in the absence of a germline BAP1 mutation suggests intraocular metastasis rather than independent primary tumors. These findings indicate that the first site of metastasis can be within the eye itself and suggest that patients with unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma may be at increased risk of systemic metastasis.

Introduction

Uveal melanoma usually presents as a solitary unifocal tumor. Bilateral uveal melanoma is rare, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1 in 50 million.1 Unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma may be even more rare.2 Most reported cases have occurred in the context of ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis, a predisposing factor for uveal melanoma.3,4 In previously reported cases of multifocal uveal melanoma without such predisposing conditions or germline mutations,2,5,6,7,8,9,10 it was unclear whether the second tumor represented a second independent primary tumor or an intraocular metastasis from the first tumor. Here, we address this question with genetic analysis in 4 cases.

Report of Cases

This was a retrospective case series conducted with University of Miami institutional review board approval. Each patient provided written informed consent. Data were collected from September 2015 to August 2018.

Four patients (all male; age range, 54-77 years) with uveal melanoma were treated with iodine 125 plaque radiotherapy and subsequently developed distinct uveal melanomas in the same eye. None of the patients had a predisposing risk factor for uveal melanoma, such as ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis, neurofibromatosis type 1, or a family history suggesting BRCA1-associated protein 1 gene (BAP1) familial cancer syndrome.11 For all 4 individuals, the diagnosis of uveal melanoma was confirmed by cytologic testing. Mutations were determined using the DecisionDX-UM-Seq (Castle Biosciences Inc) uveal melanoma–targeted sequencing panel on tumor DNA obtained from a 27-gauge fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or at enucleation.

Germline BAP1 mutation testing results were negative. The possibility that any of these cases represented intraocular metastasis from a nonocular primary melanoma was unlikely, since all patients had negative results of systemic workup, and all tumors contained uveal melanoma–specific mutations.

Case 1

This patient had an inferonasal pigmented choroidal mass (15 × 14 × 3.5 mm) (Figure 1A). The patient underwent FNAB and iodine 125 plaque radiotherapy. The tumor was found to be a mixed spindle-epithelioid uveal melanoma, and gene expression profiling (GEP) revealed a class 2 tumor. Sequencing revealed an oncogenic mutation in the G protein subunit alpha Q gene (GNAQ) p.Q209L and a deletion in the BAP1 p.R207fs (Table and Figure 2). The tumor regressed satisfactorily, but 20 months later, 3 new noncontiguous peripheral choroidal tumors arose in the superonasal periphery (Figure 1B). Enucleation was performed, and histopathology confirmed 4 distinct mixed–cell type uveal melanomas without evidence of microscopic connection between tumors. One of the subsequent tumors revealed GNAQ and BAP1 mutations identical to the initial tumor. Thirty-two months after the initial plaque radiotherapy, biopsy-confirmed hepatic metastasis was detected. Five months after this, the patient remained alive.

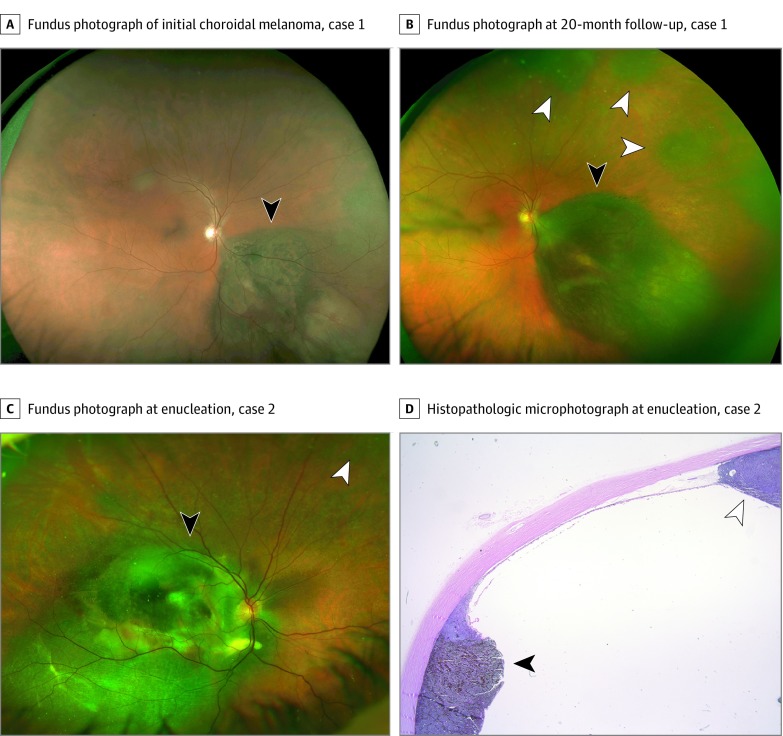

Figure 1. Patients 1 and 2 With Multifocal Uveal Melanoma.

Fundus photographs of case 1 at presentation of the initial choroidal melanoma (black arrowhead) (A and B) and at the detection of 3 distinct choroidal melanocytic tumors (white arrowheads) 20 months after plaque radiotherapy (B). Fundus photograph (C) and histopathologic photomicrograph (D) of case 2 at the time of enucleation, illustrating the original tumor treated by plaque radiotherapy (black arrowheads), and the subsequent noncontiguous tumor (white arrowheads).

Table. Summary of Clinical Information.

| Feature | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First tumora | ||||

| Largest diameter, mm | 15 | 10 | 15 | 11 |

| Thickness, mm | 3.5 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 7.8 |

| Vitreous dispersion of melanoma cells at presentation | No | No | No | Localized |

| Postradiation recurrence | No | Yes | No | No |

| Second tumorb | ||||

| Treatment | Enucleation | Enucleation | Transpupillary thermotherapy cryotherapy | Enucleation |

| Time measurements | ||||

| To detection, moc | 20 | 18 | 21 | 43 |

| To metastasis, moc | 32 | 25 | NA | NA |

| To overall follow-up, moc | 37 | 25 | 26 | 48 |

| Disposition | ||||

| Last status | Alive with metastasis | Dead of metastasis | Alive without metastasis | Alive without metastasis |

| Genes mutated in first and subsequent tumors | GNAQ Q209L, BAP1 R207fs | GNA11 Q209L | GNAQ Q209L, BAP1 R244fs | GNA11 Q209L, BAP1 E198fs |

Abbreviations: BAP1, BRCA1-associated protein 1; GNA11, guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-11; GNAQ, G protein subunit alpha Q; NA, not applicable.

In all cases, first tumors did not have ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis or ciliary body involvement; all were treated with plaque radiotherapy.

In all cases, second tumors were found to have class 2 tumors on gene expression profiling.

The starting point for all time measurements is the initial primary tumor treatment.

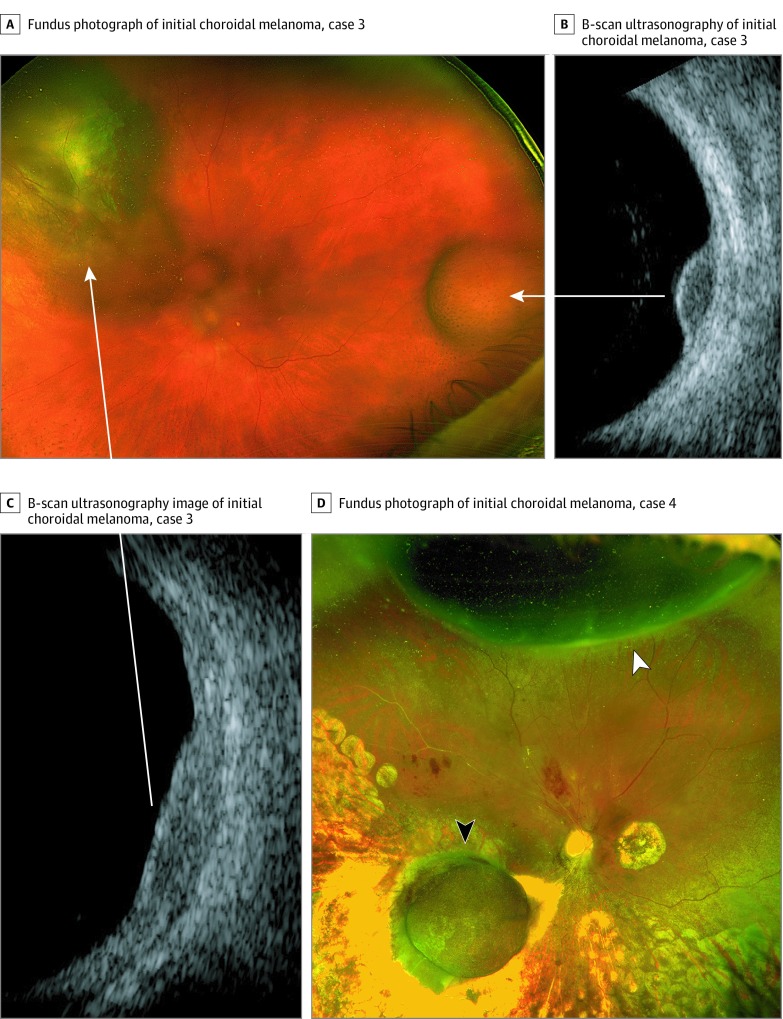

Figure 2. Patients 3 and 4 With Multifocal Uveal Melanoma.

Fundus photograph (A) and B-scan ultrasonographic images of case 3 (B and C), showing the initial juxtapapillary choroidal melanoma that was treated by plaque radiotherapy (left arrow) and the subsequent discrete choroidal melanoma arising in the temporal periphery (right arrow) 21 months after plaque radiotherapy. Arrows indicate ultrasonographic images corresponding to each tumor. Fundus photograph of case 4 (D) showing the original choroidal melanoma along the inferotemporal arcade, which was treated by plaque radiotherapy (black arrowhead), and the subsequent noncontiguous melanoma arising in the superior periphery (white arrowhead).

Case 2

The patient had a pigmented choroidal mass in the right macula (12 × 10 × 2.3 mm). Enucleation was refused, and the patient was treated with iodine 125 plaque radiotherapy with supplemental transpupillary thermotherapy, which is commonly performed in this setting to reduce the risk of local recurrence.12 Fine-needle aspiration biopsy revealed a mixed spindle and epithelioid cell melanoma with a class 2 GEP, the guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-11 gene (GNA11) mutation (p.Q209L), and no detectable BAP1 mutation (Table and Figure 2). The tumor initially regressed, but 15 months later, it regrew to 16 × 14 × 3.6 mm, at which time a second discrete ciliochoroidal tumor was noted in the superonasal periphery (Figure 1C). The eye was enucleated, and histopathologic testing confirmed that the 2 tumors were noncontiguous. The initial tumor was a spindle melanoma, and the second was a spindle-epithelioid melanoma (Figure 1D). The second tumor was class 2, with a GNA11 mutation identical to the first tumor (Table and Figure 2) and no detectable BAP1 mutation. The patient died of metastatic melanoma 25 months after initial plaque treatment.

Case 3

This patient had a superonasal pigmented choroidal tumor (15 × 13 × 3.9 mm) in the left eye with inferior exudative retinal detachment. Treatment with iodine 125 plaque radiotherapy and FNAB revealed spindle-epithelioid melanoma, a class 2 GEP, a GNA11 mutation (p.Q209L), and a BAP1 mutation (p.R244fs) (Table and Figure 2). The tumor regressed, and retinal detachment resolved within 6 months. Twenty months later, a second pigmented choroidal mass (7 × 6 × 2.4 mm) developed on the opposite side of the fundus in the temporal periphery (Figure 1E). Fine-needle aspiration biopsy revealed spindle-epithelioid melanoma, class 2 GEP, and GNA11 and BAP1 mutations identical to the first tumor. Transpupillary thermotherapy and cryotherapy successfully induced tumor regression, and the patient remained free of metastasis through 26 months of follow-up.

Case 4

This patient had a pigmented choroidal tumor along the inferotemporal vascular arcade in the right eye (11 × 11 × 7.8 mm). After undergoing iodine 125 plaque radiotherapy and FNAB, which revealed class 2 GEP, GNA11 mutation (p.Q209L), and BAP1 mutation (p.E198fs) (Table and Figure 2), the patient underwent vitrectomy to remove pigmented vitreous cells, which were found to be melanoma cells on cytopathologic examination. The tumor regressed appropriately, but a separate pigmented ciliochoroidal tumor developed 43 months later in the superior periphery (12.0 × 7.0 × 7.1 mm) (Figure 1F). The tumor was not located near the previous sclerotomy sites. Enucleation was performed, and histopathologic examination confirmed no connection between the 2 tumors. The second tumor was class 2 and harbored GNA11 and BAP1 mutations identical to those of the original tumor. The patient remained free of metastasis through 48 months of follow-up since initial treatment.

Discussion

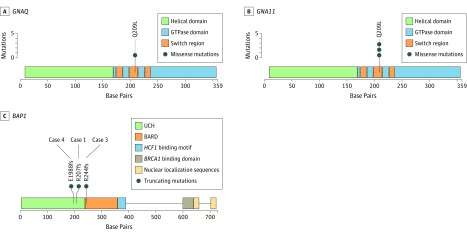

Unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma in the absence of predisposing conditions is a rare but well-attested entity.2,5,6,7,8,9,10 Numerous explanations have been offered, including genetic predisposition and independent primary tumors. In a recent report4 of a patient with ocular melanocytosis, the first tumor was class 1A and the second tumor class 2, possibly representing 2 separate de novo uveal melanomas; this is plausible, given the predisposing condition. In the cases in this study that lacked an identifiable predisposing condition, mutational analysis provided evidence for intraocular metastasis from a primary tumor to a second noncontiguous intraocular location. In all 4 cases, the tumors from a given eye contained the same GNAQ11209 mutation (Figure 3). Considering the relative frequency of each specific GNAQ11 mutation in primary uveal melanoma,15 the odds of any 1 of them arising twice in the same eye ranged from 1 in 5 to 1 in 47. Even more improbable would be the same BAP1 mutation arising independently in the same eye, since these mutations are mostly unique.16 These findings are analogous to those used to confirm intrahepatic metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma.17 As expected for tumors capable of intraocular metastasis, all included cases exhibited the metastasizing class 2 GEP. Although 2 patients have not yet developed systemic metastasis, this is not unexpected, since metastasis is a stochastic, time-dependent process, such that intraocular and distant metastasis would not necessarily occur simultaneously. There was no evidence that biopsy of the first tumor was responsible for intraocular tumor dissemination in any of the cases.

Figure 3. Distribution of Mutations in GNAQ, GNA11, and BAP1 Identified in the 4 Cases Reported.

BAP1 indicates BRCA1-associated protein 1 gene; BARD, BRCA1-associated RING domain; GNA11, guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-11 gene; GNAQ, G protein subunit alpha Q gene; GTPase, guanosine triphosphatase; and UCH, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase catalytic domain. Plots were generated using trackViewer,13 and domain information was populated based on default MutationMapper14 annotations combined with a literature review.

Conclusions

Unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma can arise in the absence of predisposing conditions and may result from intraocular metastasis. Since all of the cases in this study were class 2 tumors, this finding may indicate an elevated risk of systemic metastasis. Patients with this finding may benefit from increased metastatic surveillance.

References

- 1.Shammas HF, Watzke RC. Bilateral choroidal melanomas: case report and incidence. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(4):617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Völcker HE, Naumann GO. Multicentric primary malignant melanomas of the choroid: two separate malignant melanomas of the choroid and two uveal naevi in one eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62(6):408-413. doi: 10.1136/bjo.62.6.408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabates FN, Yamashita T. Congenital melanosis oculi complicated by two independent malignant melanomas of the choroid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;77(6):801-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser T, Thomas AS, Materin MA. Successive uveal melanomas with different gene expression profiles in an eye with ocular melanocytosis. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4(4):236-239. doi: 10.1159/000484937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen DA, Moulton GN. A case of multiple malignant melanomas in one eye. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1953;57(1):107-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon RA, Mullaney J. Multiple malignant melanomata of the uveal tract in one eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51(10):707-711. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.10.707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holck DE, Dutton JJ, Pendergast SD, Klintworth GK. Double choroidal malignant melanoma in an eye with apparent clinical regression. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(5):441-448. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(97)00136-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal EZ, Pe’er J. Multifocal choroidal malignant melanoma: at least 3 melanomas in one eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(2):255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dithmar S, Völcker HE, Grossniklaus HE. Multifocal intraocular malignant melanoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(7):1345-1348. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00722-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prager AJ, Habib LA, Busam KJ, Marr BP. Two uveal melanomas in one eye: a choroidal nevus giving rise to a melanoma in an eye with a separate large choroidal melanoma. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4(6):355-358. doi: 10.1159/000486682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walpole S, Pritchard AL, Cebulla CM, et al. Comprehensive study of the clinical phenotype of germline BAP1 variant-carrying families worldwide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1328-1341. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badiyan SN, Rao RC, Apicelli AJ, et al. Outcomes of iodine-125 plaque brachytherapy for uveal melanoma with intraoperative ultrasonography and supplemental transpupillary thermotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(4):801-805. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong J. jianhong/trackViewer. https://github.com/jianhong/trackViewer. Published August 7, 2019. Accessed August 29, 2019.

- 14.cBioPortal/mutation-mapper. https://github.com/cBioPortal/mutation-mapper. Published December 30, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2019.

- 15.Field MG, Durante MA, Anbunathan H, et al. Punctuated evolution of canonical genomic aberrations in uveal melanoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02428-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330(6009):1410-1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta M, Ueno M, Fujimoto A, et al. Whole genome sequencing discriminates hepatocellular carcinoma with intrahepatic metastasis from multi-centric tumors. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):363-373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]