Abstract

Besides the memory impairment, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is often complicated by neuropsychiatric symptoms also known as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, which occur in one-third of patients at an early stage of the disease. Although the relationship between depressive disorders and AD is debated, the question if depression is a prodromal symptom preceding cognitive deficits or an independent risk factor for AD is still unclear. Moreover, there is growing evidence reporting that conventional antidepressants are not effective in depression associated with AD and, therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the neurobiological mechanism underlying the resistance to the antidepressants. Another important question that remains to be addressed is whether the antidepressant treatment is able to modulate the levels of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), which is a key pathological hallmark in AD. The present review summarizes the present knowledge on the link between depression and AD with a focus on the resistance of antidepressant therapies in AD patients. Finally, we have briefly outlined the preclinical and clinical evidences behind the possible mechanisms by which antidepressants modulate Aβ pathology. To our opinion, understanding the cellular processes that regulate Aβ levels may provide greater insight into the disease pathogenesis and might be helpful in designing novel selective and effective therapy against depression in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, depression, amyloid-β peptide, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia in western countries, corresponding to about 60% of the cases while vascular dementia is the second, with 20% of all the cases (Kalaria et al., 2008; Rizzi et al., 2014). According to World Alzheimer’s report 2018, 50 million people worldwide are living with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to more than 150 million by 2050 (https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2018).

Memory dysfunction is a symptomatic feature of AD, which is characterized pathologically by amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) deposition and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (Querfurth and LaFerla, 2010; Tramutola et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2019).

Besides the memory impairment, AD is often complicated by neuropsychiatric symptoms also known as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), which occur in one-third of patients at an early stage of the disease (Assal and Cummings, 2002). In particular, BPSD in AD patients include among others, hallucination, sleep disorder, depression and anxiety, appetite disorder, and hyperactivity (Aalten et al., 2007; Bellanti et al., 2017). This comorbidity complicates diagnosis, influences treatment strategies, outcomes and finally quality of life, and affects individuals and caregivers (Modrego, 2010).

Studies from clinical settings have suggested that the prevalence of a “major depressive episode” in AD patients is 20–25%, with other depressive syndromes, including minor depression affecting an additional 20–30% of patients (Pearlson et al., 1990; Assal and Cummings, 2002; Shim and Yang, 2006; Richard et al., 2013; Leong, 2014). AD patients with major depression show a greater and faster cognitive impairment compared to non-depressed patients (Milwain and Nagy, 2005) and, surprisingly, neuritic plaques and NFTs are more evident in the cerebral parenchyma of AD patients with comorbid depression than non-depressed AD patients (Rapp et al., 2008).

Although the link between depressive disorder and AD is debated, the question whether depression is a prodromal symptom or an independent risk factor for AD still remains unresolved. Moreover, there is growing evidence in the literature that conventional antidepressants are not effective in depression accompanied by AD (Pomara and Sidtis, 2007) and, therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the neurobiological mechanism underlying the resistance to the antidepressants.

Hence, we examined the possible link between depression and AD, and we focused on the resistance of antidepressant therapies in dementia. Subsequently, we explored probable mechanisms by which antidepressants modulate Aβ pathology. The latter evidence may be helpful in designing novel selective and effective therapy against depression in AD.

Relationship Between Depression and AD: Prodromal Symptom or Risk Factor?

To date, converging evidence suggests that depression may represent a risk factor for the development of AD (Steffens et al., 1997; Modrego and Ferrández, 2004; Bartolini et al., 2005; Ownby et al., 2006), mostly when depressive symptoms occur more than 10 years before the onset of AD (Speck et al., 1995). To this regard, a systematic meta-analysis study evaluated whether observed risk for developing AD was related to the interval between diagnosis of depression and AD (Ownby et al., 2006). The authors found that there was a positive correlation between this interval and the risk of developing AD, suggesting that, rather than a prodrome, depression can be considered as a risk factor for AD. This study reported that patients with a history of depression were more prone to be affected by AD later in life (Ownby et al., 2006).

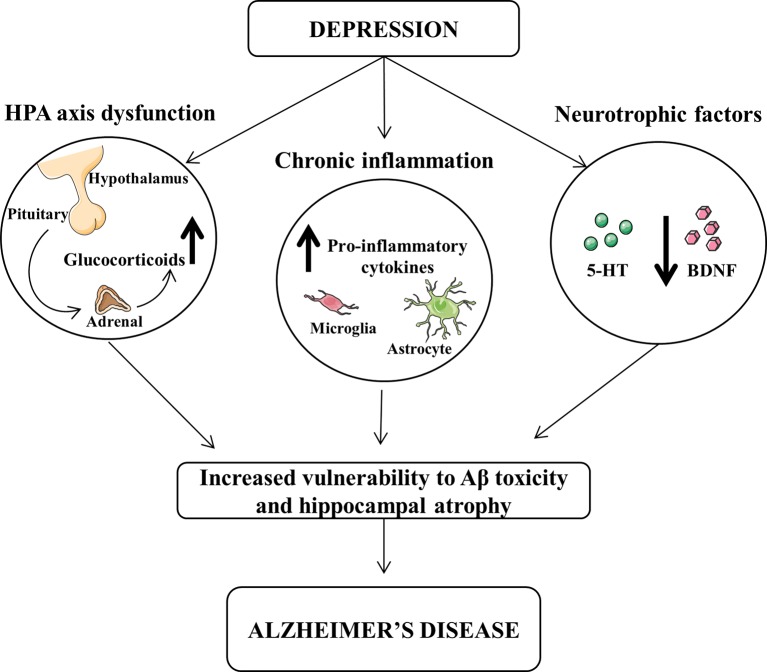

Several hypotheses could be proposed for this interpretation and summarized in Figure 1 . High cortisol levels or hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation has been associated to depression symptoms and alteration of learning and memory (Swaab et al., 2005). Corticosteroid receptors are particularly abundant in the hippocampus, which is one of the main brain regions affected by AD pathology, and their excessive stimulation may be detrimental leading to neuronal death through an apoptotic mechanism (Sapolsky, 2000; Lee et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Dysfunction of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and decrease of neurotrophic factors and chronic inflammation exert a central role in the pathophysiology of both depression and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The increased levels of glucocorticoids and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as the reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and serotonin (5-HT) may lead to an increased vulnerability of β-amyloid toxicity and hippocampal atrophy, thus favoring the progression from depression to AD.

It has been demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokines play an important role in the expression of the clinical symptoms of depression in AD patients. In particular, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 are increased during depression, as well as associated with cognitive impairment (Parissis et al., 2004; Suarez et al., 2004; Wuwongse et al., 2010).

Moreover, neurotrophic factors have a protective action against toxic agents, which may induce neurodegeneration. Chronic treatment with antidepressants up-regulate the expression of neurotrophic factors increasing hippocampal neurogenesis (Mattson, 2004).

The elevation of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as the reduction of neurotrophic factors, may lead to alterations in the monoaminergic neurotransmitters, which are downregulated in either depression or AD (Reinikainen et al., 1990; Romano et al., 2014). To this regard, it has been demonstrated that depressed patients affected by AD show neuronal degeneration in locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei, both brain regions implicated in depression (Zubenko et al., 1990). Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that reduced levels of brain serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine occur in depression, and antidepressants lead to an increase of both neurotransmitter activities in the brain (Chen and Skolnick, 2007). Yet, similar neurotransmitter alterations are also present in AD, as we have also demonstrated in an animal model of AD (Reinikainen et al., 1990; Romano et al., 2014).

Although many treatment options are available, several clinical trials suggest that antidepressants for the treatment of depression in AD patients appear ineffective (Pomara and Sidtis, 2007; Sepehry et al., 2012). To this regard, the results of the completed United States NIMH-funded, large-scale STAR*D effectiveness trial reported a remission rate of only 70% after 12 months with up to four treatment steps (Insel and Wang, 2009). In general, the tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) are less prescribed to AD patients with depression due to their serious cardiac and anticholinergic side effects (Raji and Brady, 2001; Banerjee et al., 2013), while the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most prescribed drugs although evidence for their efficacy in this population is controversial (Nyth et al., 1992; Katonaet al., 1998).

To date, no medication has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of depressive symptoms in AD. Some of the evidence found in geriatric population has demonstrated that antidepressant therapy can improve the depression after 4–6 weeks of treatment (Wilson et al., 2001). However, its efficacy and safety remain inconclusive in individuals with AD, and it can be a challenging task to evaluate the role and mechanisms of antidepressants in subjects with AD (Leong, 2014; Lozupone et al., 2018). Numerous mechanisms underlying resistance to antidepressants in patients with AD have been hypothesized (for review, see Lozupone et al., 2018). In upcoming future, for developing specific and effective therapy against depression in AD, studies investigating compounds targeting alternative signal transduction pathways are warranted.

Antidepressant Treatments Modulate Aβ Levels

Postmortem analyses of brain patients and studies on transgenic animal models have demonstrated that the major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are the extracellular deposits of Aβ plaques abundant mainly in the cortex and hippocampus (Oakley et al., 2006; Oddo et al., 2006; LaFerla et al., 2007; Cassano et al., 2011; Gatta et al., 2016). Moreover, numerous preclinical studies have firmly demonstrated that the accumulation of intracellular Aβ precedes extracellular plaque formation (Oakley et al., 2006; Oddo et al., 2006; LaFerla et al., 2007). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that intraneuronal Aβ levels decrease as extracellular plaques accumulate.

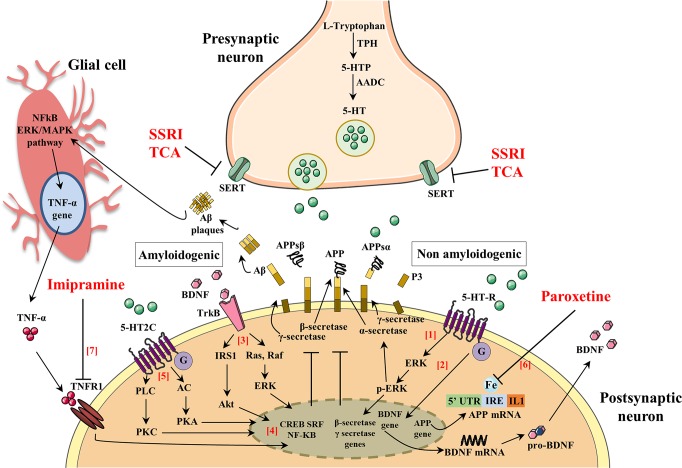

A number of pathogenic mechanisms triggering the neurodegenerative phenomena and leading to neuronal death have been described. Among them, a crucial role seems to be played by inflammation (Bronzuoli et al., 2018; Scuderi et al., 2018; Bronzuoli et al., 2019), oxidative damage (Reddy et al., 2009; Serviddio et al., 2011; Cassano et al., 2012; Cassano et al., 2016; Giudetti et al., 2018), iron deregulation (Adlard and Bush, 2006), and cholesterol metabolism (Stefani and Liguri, 2009; Barone et al., 2016). Therefore, novel therapeutical strategies aim to interfere with those pathogenic mechanisms at an early stage of the disease in order to stop/slow down the neurodegenerative process. For this reason, they have been termed “disease-modifying” drugs and should be administered to patients many years before the appearance of the first AD symptoms (Morris and Price, 2001). Consequently, if anti-Aβ therapies may be used for years or decades, then very safe compounds will likely be necessary. To this regard, SSRIs are good candidates for this purpose since their side effects are generally well tolerated, even with chronic use. In support to such hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that SSRIs reduce risk of AD in depressed individuals (Kessing et al., 2009). Therefore, individuals with a history of chronic use of antidepressant drug use may have reduced Aβ plaques and, as a result, a reduced risk of AD. Nevertheless, although this hypothesis has been postulated, it is still matter of debate whether antidepressant treatment rises or declines the level of Aβ in the brain. To this purpose, many researchers have investigated whether the activation of 5-HT receptors can regulate Aβ metabolism. Figure 2 and Table 1 summarize the molecular mechanisms by which antidepressant drugs may induce a reduction of the Aβ levels.

Figure 2.

The activation of serotonin receptors (5-HT-R) initiates a signaling cascade that leads to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK). Once activated, p-ERK increases α-secretase activity and reduces β- and γ-secretase cleavage of APP (1). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and serotonin (5-HT) regulate synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuronal survival. The activation of 5-HT-R stimulates the expression of BDNF, which in turn enhances the growth and survival of 5-HT neurons (2). BDNF binds to its high-affinity tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) resulting in the recruitment of proteins that activate two different signal transduction cascades: (i) insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3K), and protein kinase B (Akt) and (ii) Ras, Raf, and extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK) (3). BDNF signaling pathways activate one or more transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes encoding proteins. Such transcription factors include cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB), serum response factor (SRF), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) that exert an inhibitory action in the amyloidogenic pathways (4). 5-HT binds 5-HT-2C resulting in the recruitment of proteins that activate two different signal transduction cascades: (i) adenylate cyclase (AC), cAMP, and protein kinase A (PKA) and (ii) phospholipase C (PLC), diacylglycerol (DAG), and protein kinase C (PKC) (5). The 5-HT signaling pathway activates one or more transcription factors that regulate expression of genes encoding proteins (CREB, SRF, and NF-kB) leading to an inhibitory action in the amyloidogenic pathways (4). The 5’-untranslated region (5’UTR) of the APP mRNA is a key regulatory sequence that determines the amount of intracellular APP holoprotein present in brain-derived cells in response to interleukin-1 (IL-1) and iron (IRE). Paroxetine acts as an intracellular iron chelator to limit the translation of APP holoprotein guided by sequences of untranslated APP mRNA 5’UTR regions (6). Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) signaling, through tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), mainly results in activation of the transcription factors NF-kB and induces pro-inflammatory effects that exacerbate neuroinflammation and secondary neuronal damage. Imipramine blocks TNF-α/TNFR1 signaling and prevents the appearance of cognitive deficits in AD and Aβ formation (7).

Table 1.

Effect of antidepressant drugs on Aβ production.

| PRECLINICAL STUDIES: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant drugs | Subjects | Effects and mechanisms involved | References |

| Fluoxetine, desvenlafaxine, citalopram (SSRIs) | PS1APP transgenic mice | ↓ Aβ levels ↓ Aβ plaques in the cortex and hippocampus ↓ ERK signaling ↑ α-Secretase activity |

Cirrito et al., 2011 |

| Paroxetine (SSRI) | 3×TgAD mice | ↓ Aβ levels ↓ APP production ↓ 5-HT reuptake ↑ BDNF expression |

Nelson et al., 2007

Mattson, 2004 |

| Paroxetine (SSRI) | TgCRND8 mice | ↓ Aβ levels in the cortex ↓ APP holoprotein translation driven by APP mRNA 5′ untranslated region sequences |

Tucker et al., 2005 and Tucker et al., 2006 |

| Paroxetine (SSRI) | Neuroblastoma cells (SY5Y) | ↓ APP holoprotein translation driven by APP mRNA 5′ untranslated region sequences | Morse et al., 2004 |

| Imipramine (TCA) | Rat primary basal forebrain cultures | ↑ APP secretion ↑ PKC level |

Pákáski et al., 2005 |

| Citalopram (SSRI) | Rat primary basal forebrain cultures | ↑ APP secretion = PKC level |

Pákáski et al., 2005 |

| Imipramine (TCA) | Swiss mice after intracerebroventricular injection of Aβ25-35 | ↓ Aβ levels in the frontal cortex ↓ TNF-α level |

Chavant et al., 2010 |

| HUMAN STUDIES: | |||

| Antidepressant drugs | Subjects | Effects | References |

| SSRI TCA Trazodone Venlafaxine (SNRI) Bupropion Mirtazapine (NaSSA) |

Plasma of elderly depressed patients | = Aβ42 levels ↓ Aβ40 levels |

Sun et al., 2007 |

| Paroxetine (SSRI) Nortriptyline (TCA) |

Plasma of elderly patients with late-life major depression | = Aβ42 levels ↑ Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio |

Pomara et al., 2006 |

| Conventional antidepressants | Plasma of young patients affected by major depressive disorder | = Aβ levels ↑ Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio |

Kita et al., 2009 |

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; NASSA, noradrenaline and specific serotonergic antidepressant.

Interestingly, in a preclinical study, it has been demonstrated that extracellular Aβ levels were decreased by 25% following the acute administration of several SSRI antidepressant drugs (fluoxetine, desvenlafaxine, and citalopram) and that chronic treatment with citalopram caused a 50% reduction Aβ plaques in the cortex and hippocampus of a mouse model of AD (Cirrito et al., 2011). In this study, authors demonstrated that SSRI can modulate APP processing through the activation of extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, which has been shown to suppress Aβ production in vitro and in vivo by increasing α-secretase cleavage of APP (Kim et al., 2006; Kojro et al., 2006). Once activated, ERK is able to phosphorylate specific effector proteins modulating a wide range of responses within the cytoplasm and the nucleus altering, in turn, the transcription of a wide range of genes (Kim et al., 2006; Kojro et al., 2006). Therefore, authors showed that a reduction of Aβ levels in a mouse model of AD was obtained after both acute and chronic citalopram treatments through an increase of α-secretase activity (Cirrito et al., 2011). These and many other findings suggest that the activation of 5-HT receptors by SSRI may have an “upstream” role within the amyloid cascade that may modulate the proteases involved in Aβ production itself.

Moreover, SSRI treatment showed similar effect in a triple transgenic murine model of AD (3×Tg-AD), which harbors three mutant human genes (APPswe, PS1M146V, and tauP301L) and exhibited a depressive-like phenotype with deficits of monoaminergic neurotransmissions (Oddo et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2007; Romano et al., 2014; Scuderi et al., 2018; Barone et al., 2019; Cassano et al., 2019). Nelson and colleagues reported that pre-symptomatic treatment with the antidepressant paroxetine reduces Aβ pathology in the hippocampus and improves cognitive performance in the 3×TgAD mice (Nelson et al., 2007). In particular, 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice were treated for 5 months with a dose of paroxetine that inhibits 5-HT reuptake and ameliorates behavioral deficits in mouse models of anxiety and depression (Cryan et al., 2004; Goeldner et al., 2005). Taking together these results and considering the safe profile of paroxetine after chronic treatment also in elderly patients, the authors suggested that paroxetine might be a valuable therapeutic option for depressed human subjects with early AD symptoms.

The beneficial effects of paroxetine seem to be mediated by the inhibition of 5-HT reuptake resulting in both enhanced serotonergic signaling and upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression (Mattson, 2004). Preclinical and clinical studies have highlighted that there is a tight interplay between SSRI treatment and BDNF expression. In particular, results from animal studies have demonstrated that paroxetine elevates both 5-HT and BDNF in huntingtin mutant mice reducing the onset and progression of the disease (Duan et al., 2004), as well as BDNF expression was increased in both hippocampus and cortex after its chronic administration in rodents (Nibuya et al., 1995; Nibuya et al., 1996). Moreover, antidepressant effects were observed when BDNF was directly injected into the rodent hippocampus (Siuciak et al., 1997; Shirayama et al., 2002). Furthermore, in human studies, it has been shown that (i) AD patients showed low levels of both 5-HT (Gottfries, 1990) and BDNF (Hock et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2005) in the hippocampus and cortex, and that (ii) antidepressants were able to increase also BDNF levels (Chen et al., 2001; Dwivedi et al., 2003).

Besides BDNF and 5-HT, antidepressant drugs may exert their effects also via different pathways. In fact, paroxetine seems to target APP gene expression through the 5’-untranslated region (5’UTR) of the precursor transcript suppressing translation of the APP protein (Morse et al., 2004; Tucker et al., 2005). The 5’UTR of the transcript encoding the APP (APP 5’UTR) is an important regulatory sequence that regulates the amount of intracellular APP holoprotein present in neuron cells in response to interleukin-1 (IL-1) (acute box-domain) (Rogers et al., 1999) and iron (Rogers et al., 2002). Within the 5’UTR of the APP transcript is present an Iron-responsive Element (IRE type II), which is a RNA stem loop that controls cellular iron homeostasis and is located immediately upstream of an IL-1 responsive acute box domain (Rogers et al., 2002). Therefore, the authors suggest that paroxetine may act as a chelator of intracellular iron to consequently limit APP holoprotein translation driven by APP mRNA 5’UTR sequences (Morse et al., 2004; Tucker et al., 2005). Treating 3-month-old TgCRND8 mice with paroxetine for 3 months, the authors found that paroxetine reduced the soluble and insoluble Aβ levels in the cortex of TgCRND8 transgenic mice (Tucker et al., 2005; Tucker et al., 2006). Moreover, Morse and colleagues have demonstrated that paroxetine significantly reduced the levels of APP in the neuroblastoma cells (SY5Y), whereas equivalent levels of APP-like protein 1 (APLP-1) were unchanged. As IRE sequences were absence in the 5’UTR of the APLP-1 transcript, paroxetine did not affect its levels (Morse et al., 2004).

Antidepressants seem to modulate also the expression of protein kinase C (PKC), which is a key signal transduction factor in the stimulation of APP secretion induced by the activation of 5-HT2C receptors (Nitsch et al., 1996; Arjona et al., 2002). To this regard, Pákáski and colleagues investigated in vitro whether the TCA imipramine and the SSRI citalopram were able to modulate the PKC levels in rat primary basal forebrain cultures leading to an increased release of APP (Pákáski et al., 2005). The authors found that both imipramine and citalopram significantly increase the APP secretion (3.2- or 3.4-fold, respectively), although imipramine caused a more rapid and long-lasting APP secretion compared to citalopram. These results were accompanied by a consistent increase of PKC level after imipramine treatment while no significant effects were observed after citalopram treatment. This difference may be due to the different mechanism in monoamine uptake between antidepressants. In fact, after chronic treatment with SSRI fluoxetine, the activity of PKC was suppressed in the cortex and hippocampus of rodents (Mann et al., 1995), whereas while an increased PKC activity in rabbit and human platelets was reported after TCA administration (Morishita and Aoki, 2002). These results highlighted the primary role of antidepressants on the APP metabolism, although further investigations need to be performed in order to clarify the different profile between TCA and SSRI.

Preclinical and clinical evidences support a central role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of AD and depression (Tan et al., 1999; Dantzer et al., 2008). Human studies have demonstrated that the proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, and IL-1β are significantly increased in depressed subjects, as well as in the brain and plasma of AD patients (Dantzer et al., 2008). A crucial role of inflammation in the AD pathogenesis was further demonstrated by higher expression of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) in AD brain (Li et al., 2004). Moreover, the deletion of TNFR1 causes a reduction of both Aβ production and microglia activation as well as ameliorates the cognitive deficits in APP23 mice (He et al., 2007). TNF-α signaling through TNFR1 activates the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 and induces pro-inflammatory effects that further exacerbate neuroinflammation leading to neuronal death (Probert, 2015). Thus, the use of specific pharmacological agents that counteract TNF-α/TNFR1 signaling may be a promising therapeutic strategy to reduce the cognitive alterations and Aβ formation. To this regard, Chavant and colleagues investigated the effects of TCA imipramine on the TNF-α expression and APP metabolism using a model of Aβ25–35 intracerebroventricular infusion in mice (Chavant et al., 2010). Previous reports have demonstrated that intracerebroventricular injection of Aβ25–35 peptide induced alterations of spatial and working memory and enhanced the levels of APP and TNF-α in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of mice (Maurice et al., 1996; Lu et al., 2009). Chavant and colleagues found that imipramine prevented the Aβ25–35-induced deficits of both long- and short-term memories and significantly reduced the intracellular Aβ immunoreactivity in the frontal cortex counteracting the TNF-α increase induced by the Aβ25–35 intracerebroventricular injection (Chavant et al., 2010). Thus, these results support the claim that imipramine may be a potential candidate for the treatment of AD because of its intrinsic property to inhibit TNF-α. Overall, the preclinical studies showed a reduction of Aβ pathology after antidepressants treatment.

Differently, human studies did not show a clear-cut effect of antidepressants on Aβ metabolism. To this regard, Sun and colleagues reported that elderly depressed patients had lower plasma Aβ42 levels than those without depression, and such difference was not modified after antidepressant treatment with SSRI, TCA, trazodone, and all others including venlafaxine, bupropion, and mirtazapine (Sun et al., 2007). Conversely, antidepressants were able to reduce the plasma Aβ40 levels in depressed patients, although any significant difference was observed before treatment between subjects with depression and those without depression (Sun et al., 2007). Similarly, Pomara and colleagues confirmed that plasma Aβ42 levels were not affected by either paroxetine or nortriptyline, although the authors reported for the first time an elevation in plasma Aβ42 levels and the Aβ42/40 ratio in elderly patients with late-life major depression (Pomara et al., 2006). Finally, Kita and colleagues reported that Aβ42 was slightly increased also in young patients affected by major depressive disorder suggesting that Aβ42 alteration may be detrimental even in young depressed population. Moreover, the latter study confirmed that the pharmacological treatment with conventional antidepressants did not affect Aβ plasma concentrations (Kita et al., 2009).

Unfortunately, all data from clinical studies are quite mixed, and the results are difficult to interpret, due to different study methods, heterogeneous patient populations, variability in outcome measures, and concomitant treatments. Thus, more studies need to be done in order to establish whether AD patients with depression show increased or decreased plasma Aβ levels and whether these individuals may benefit from antidepressant treatments.

Conclusion

The present review provides evidence that depression is associated with an increased risk of AD, and although many treatment options are available, several clinical trials suggest that conventional antidepressants are ineffective for the treatment of depression in AD patients. Moreover, results from human investigations do not give a clear picture on whether antidepressants are able to clearly modulate the Aβ production and eventually slow down the accumulation of the Aβ42 into the cerebral parenchyma. This calls for a critical analysis of the current trials on the efficacy of antidepressants, as a treatment option. In fact, although many studies have filled some of the gaps, conflicting and inconclusive results continue to represent a challenge for physicians. Moreover, depression in AD comorbidity represents a big challenge in term of correct identification and evaluation of symptoms, also because late-life depression occurs in a complex medical and psychosocial context. To this regard, the functional neuroimaging approach may contribute elucidating both the brain structure and function specifically affected in both pathologies.

This review pulls together evidence that justifies the therapeutical inefficacy of antidepressants in AD patients and promotes further research in order to design novel selective and effective therapy against depression in AD.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the writing, design and preparation of figures. The senior authors TC and SG have carried out coordination of efforts.

Funding

This article was published with a contribution from 5 x 1000 IRPEF funds in favour of the University of Foggia, in memory of Gianluca Montel.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MP declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors SC, AC, AR, SG to the handling editor.

References

- Aalten P., Verhey F. R., Boziki M., Bullock R., Byrne E. J., Camus V., et al. (2007). Neuropsychiatric syndromes in dementia. Results from the European Alzheimer disease. Consortium: part I. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 24, 457–463. 10.1159/000110738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlard P. A., Bush A. I. (2006). Metals and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 10, 145–163. 10.3233/JAD-2006-102-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjona A. A., Pooler A. M., Lee R. K., Wurtman R. J. (2002). Effect of a 5-HT(2C) serotonin agonist, dexnorfenfluramine, on amyloid precursor protein metabolism in guinea pigs. Brain Res. 27, 135–140. 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assal F., Cummings J. L. (2002). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 15, 445–450. 10.1097/00019052-200208000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Hellier J., Romeo R., Dewey M., Knapp M., Ballard C., et al. (2013). Study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia: the HTA-SADD trial—a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sertraline and mirtazapine. Health Technol. Assess. 17, 1–166. 10.3310/hta17070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone E., Di Domenico F., Cassano T., Arena A., Tramutola A., Lavecchia M. A., et al. (2016). Impairment of biliverdin reductase-A promotes brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer disease: a new paradigm. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 91, 127–142. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone E., Tramutola A., Triani F., Calcagnini S., Di Domenico F., Ripoli C., et al. (2019). Biliverdin reductase-A mediates the beneficial effects of intranasal insulin in Alzheimer disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 2922–2943. 10.1007/s12035-018-1231-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini M., Coccia M., Luzzi S., Provinciali L., Ceravolo M. G. (2005). Motivational symptoms of depression mask preclinical Alzheimer’s disease in elderly subjects. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 19, 31–36. 10.1159/000080968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanti F., Iannelli G., Blonda M., Tamborra R., Villani R., Romano A., et al. (2017). Alterations of clock gene RNA expression in brain regions of a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 59, 615–631. 10.3233/JAD-160942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronzuoli M. R., Facchinetti R., Steardo L., Jr., Romano A., Stecca C., Passarella S., et al. (2018). Palmitoylethanolamide dampens reactive astrogliosis and improves neuronal trophic support in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease: In vitro and in vivo evidence. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 4720532. 10.1155/2018/4720532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronzuoli M. R., Facchinetti R., Valenza M., Cassano T., Steardo L., Scuderi C. (2019). Astrocyte function is affected by aging and not Alzheimer’s disease: a preliminary investigation in hippocampi of 3xTg-AD mice. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 644. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano T., Romano A., Macheda T., Colangeli R., Cimmino C. S., Petrella A., et al. (2011). Olfactory memory is impaired in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Behav. Brain Res. 224, 408–412. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano T., Serviddio G., Gaetani S., Romano A., Dipasquale P., Cianci S., et al. (2012). Glutamatergic alterations and mitochondrial impairment in a murine model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 33 (1121), e1–12. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano T., Pace L., Bedse G., Lavecchia A. M., De Marco F., Gaetani S., et al. (2016). Glutamate and mitochondria: two prominent players in the oxidative stress-induced neurodegeneration. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13, 185–197. 10.2174/1567205013666151218132725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano T., Magini A., Giovagnoli S., Polchi A., Calcagnini S., Pace L., et al. (2019). Early intrathecal infusion of everolimus restores cognitive function and mood in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 311, 88–105. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavant F., Deguil J., Pain S., Ingrand I., Milin S., Fauconneau B., et al. (2010). Imipramine, in part through tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition, prevents cognitive decline and beta-amyloid accumulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332, 505–514. 10.1124/jpet.109.162164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Dowlatshahi D., MacQueen G. M., Wang J. F., Young L. T. (2001). Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol. Psychiatry. 50, 260–265. 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Skolnick P. (2007). Triple uptake inhibitors: therapeutic potential in depression and beyond. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 16, 1365–1377. 10.1517/13543784.16.9.1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito J. R., Disabato B. M., Restivo J. L., Verges D. K., Goebel W. D., Sathyan A., et al. (2011). Serotonin signaling is associated with lower amyloid-β levels and plaques in transgenic mice and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 14968–14973. 10.1073/pnas.1107411108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan J. F., O’Leary O. F., Jin S. H., Friedland J. C., Ouyang M., Hirsch B. R., et al. (2004). Norepinephrine-deficient mice lack responses to antidepressant drugs, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 8186–8191. 10.1073/pnas.0401080101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O’Connor J. C., Freund G. G., Johnson R. W., Kelley K. W. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 46–56. 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W., Guo Z., Jiang H., Ladenheim B., Xu X., Cadet J. L., et al. (2004). Paroxetine retards disease onset and progression in Huntingtin mutant mice. Ann. Neurol. 55, 590–594. 10.1002/ana.20075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y., Rao J. S., Rizavi H. S., Kotowski J., Conley R. R., Roberts R. C., et al. (2003). Abnormal expression and functional characteristics of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 273–282. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta E., Lefebvre T., Gaetani S., dos Santos M., Marrocco J., Mir A. M., et al. (2016). Evidence for an imbalance between tau O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in the hippocampus of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 105, 186–197. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudetti A. M., Salzet M., Cassano T. (2018). Oxidative stress in aging brain: nutritional and pharmacological interventions for neurodegenerative disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 3416028. 10.1155/2018/3416028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeldner F. O., Pigatto G., Ribeiro A. F., Machado H. B., Boerngen-Lacerda R. (2005). Influence of fluoxetine and paroxetine in behavioral sensitization induced by ethanol in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 82, 388–396. 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfries C. G. (1990). Disturbance of the 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in brains from patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. J. Neural. Transm. Suppl. 30, 33–43. 10.1007/978-3-7091-3345-3_4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- He P., Zhong Z., Lindholm K., Berning L., Lee W., Lemere C., et al. (2007). Deletion of tumor necrosis factor death receptor inhibits amyloid beta generation and prevents learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s mice. J. Cell Biol. 178, 829–841. 10.1083/jcb.200705042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock C., Heese K., Hulette C., Rosenberg C., Otten U. (2000). Region-specific neurotrophin imbalances in Alzheimer disease: decreased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and increased levels of nerve growth factor in hippocampus and cortical areas. Arch. Neurol. 57, 846–851. 10.1001/archneur.57.6.846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T. R., Wang P. S. (2009). The STAR*D trial: revealing the need for better treatments. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 1466–1467. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.11.1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria R. N., Maestre G. E., Arizaga R., Friedland R. P., Galasko D., Hall K., et al. (2008). Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 7, 812–826. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona C. L., Hunter B. N., Bray J. (1998). A double-blind comparison of the efficacy and safely of paroxetine and imipramine in the treatment of depression with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 13, 100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing L. V., Søndergård L., Forman J. L., Andersen P. K. (2009). Antidepressants and dementia. J. Affect. Disord. 117, 24–29. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Park H. J., Hong H. S., Baik E. J., Jung M. W., Mook-Jung I. (2006). ERK1/2 is an endogenous negative regulator of the gamma-secretase activity. FASEB J. 20, 157–159. 10.1096/fj.05-4055fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita Y., Baba H., Maeshima H., Nakano Y., Suzuki T., Arai H. (2009). Serum amyloid beta protein in young and elderly depression: a pilot study. Psychogeriatrics 9, 180–185. 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojro E., Postina R., Buro C., Meiringer C., Gehrig-Burger K., Fahrenholz F. (2006). The neuropeptide PACAP promotes the alpha-secretase pathway for processing the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. FASEB J. 20, 512–514. 10.1096/fj.05-4812fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla F. M., Green K. N., Oddo S. (2007). Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 499–509. 10.1038/nrn2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. L., Ogle W. O., Sapolsky R. M. (2002). Stress and depression: possible links to neuron death in the hippocampus. Bipolar Disord. 4, 117–128. 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Fukumoto H., Orne J., Klucken J., Raju S., Vanderburg C. R., et al. (2005). Decreased levels of BDNF protein in Alzheimer temporal cortex are independent of BDNF polymorphisms. Exp. Neurol. 194, 91–96. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong C. (2014). Antidepressants for depression in patients with dementia: a review of the literature. Consult. Pharm. 29, 254–263. 10.4140/TCP.n.2014.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Yang L., Lindholm K., Konishi Y., Yue X., Hampel H., et al. (2004). Tumor necrosis factor death receptor signaling cascade is required for amyloid-beta protein-induced neuron death. J. Neurosci. 24, 1760–1771. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4580-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone M., La Montagna M., D’Urso F., Piccininni C., Sardone R., Dibello V., et al. (2018). Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of depression in patients with alzheimer’s disease: a treatment-resistant depressive disorder. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 19, 823–842. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1471136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P., Mamiya T., Lu L. L., Mouri A., Niwa M., Hiramatsu M., et al. (2009). Silibinin attenuates amyloid beta(25-35) peptide-induced memory impairments: implication of inducible nitric-oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 319–326. 10.1124/jpet.109.155069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C. D., Vu T. B., Hrdina P. D. (1995). Protein kinase C in rat brain cortex and hippocampus: effect of repeated administration of fluoxetine and desipramine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 115, 595–600. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14973.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M. P. (2004). Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 430, 631–639. 10.1038/nature02621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T., Lockhart B. P., Privat A. (1996). Amnesia induced in mice by centrally administered beta-amyloid peptides involves cholinergic dysfunction. Brain Res. 706, 181–193. 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milwain E. J., Nagy Z. (2005). Depressive symptoms increase the likelihood of cognitive impairment in elderly people with subclinical Alzheimer pathology. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 19, 46–50. 10.1159/000080971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrego P. J., Ferrández J. (2004). Depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of developing dementia of Alzheimer type: a prospective cohort study. Arch. Neurol. 61, 1290–1293. 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrego P. J. (2010). Depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21, 1077–1087. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita S., Aoki S. (2002). Effects of tricyclic antidepressants on protein kinase C activity in rabbit and human platelets in vivo. J. Affect. Disord. 70, 329–332. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. C., Price J. L. (2001). Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 17, 101–118. 10.1385/JMN:17:2:101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse L. J., Payton S. M., Cuny G. D., Rogers J. T. (2004). FDA-preapproved drugs targeted to the translational regulation and processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Mol. Neurosci. 24, 129–136. 10.1385/JMN:24:1:129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. L., Guo Z., Halagappa V. M., Pearson M., Gray A. J., Matsuoka Y., et al. (2007). Prophylactic treatment with paroxetine ameliorates behavioral deficits and retards the development of amyloid and tau pathologies in 3xTgAD mice. Exp. Neurol. 205, 166–176. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M., Morinobu S., Duman R. S. (1995). Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J. Neurosci. 15, 7539–7547. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M., Nestler E. J., Duman R. S. (1996). Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 16, 2365–2372. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02365.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch R. M., Deng M., Growdon J. H., Wurtman R. J. (1996). Serotonin 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors stimulate amyloid precursor protein ectodomain secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4188–4194. 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyth A. L., Gottfries C. G., Lyby K., Smedegaard-Andersen L., Gylding-Sabroe J., Kristensen M., et al. (1992). A controlled multicenter clinical study of citalopram and placebo in elderly depressed patients with and without concomitant dementia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 86, 138–145. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H., Cole S. L., Logan S., Maus E., Shao P., Craft J., et al. (2006). Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 26, 10129–10140. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J. D., Murphy M. P., Golde T. E., Kayed R., et al. (2003). Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron 39, 409–421. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00434-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S., Caccamo A., Smith I. F., Green K. N., LaFerla F. M. (2006). A dynamic relationship between intracellular and extracellular pools of Abeta. Am. J. Pathol. 168, 184–194. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ownby R. L., Crocco E., Acevedo A., John V., Loewenstein D. (2006). Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 530–538. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pákáski M., Bjelik A., Hugyecz M., Kása P., Janka Z., Kálmán J. (2005). Imipramine and citalopram facilitate amyloid precursor protein secretion in vitro. Neurochem. Int. 47, 190–195. 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parissis J. T., Adamopoulos S., Rigas A., Kostakis G., Karatzas D., Venetsanou K., et al. (2004). Comparison of circulating proinflammatory cytokines and soluble apoptosis mediators in patients with chronic heart failure with versus without symptoms of depression. Am. J. Cardiol. 94, 1326–1328. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlson G. D., Ross C. A., Lohr W. D., Rovner B. W., Chase G. A., Folstein M. F. (1990). Association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 147, 452–456. 10.1176/ajp.147.4.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara N., Doraiswamy P. M., Willoughby L. M., Roth A. E., Mulsant B. H., Sidtis J. J., et al. (2006). Elevation in plasma Abeta42 in geriatric depression: a pilot study. Neurochem. Res. 31, 341–349. 10.1007/s11064-005-9029-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara N., Sidtis J. (2007). Possible therapeutic implication of Abeta disturbances in depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 22, 931–932. 10.1002/gps.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert L. (2015). TNF and its receptors in the CNS: The essential, the desirable and the deleterious effects. Neuroscience 302, 2–22. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth H. W., LaFerla F. M. (2010). Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 329–344. 10.1056/NEJMra0909142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji M. A., Brady S. R. (2001). Mirtazapine for treatment of depression and comorbidities in Alzheimer disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 35, 1024–1027. 10.1345/aph.10371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp M. A., Schnaider-Beeri M., Purohit D. P., Perl D. P., Haroutunian V., Sano M. (2008). Increased neurofibrillary tangles in patients with Alzheimer disease with comorbid depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16, 168–174. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816029ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V. P., Zhu X., Perry G., Smith M. A. (2009). Oxidative stress in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 16, 763–774. 10.3233/JAD-2009-1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinikainen K. J., Soininen H., Riekkinen P. J. (1990). Neurotransmitter changes in Alzheimer’s disease: implications to diagnostics and therapy. J. Neurosci. Res. 27, 576–586. 10.1002/jnr.490270419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard E., Reitz C., Honig L. H., Schupf N., Tang M. X., Manly J. J., et al. (2013). Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 70, 374–382. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi L., Rosset I., Roriz-Cruz M. (2014). Global epidemiology of dementia: Alzheimer’s and vascular types. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 908915. 10.1155/2014/908915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. T., Leiter L. M., McPhee J., Cahill C. M., Zhan S. S., Potter H., et al. (1999). Translation of the alzheimer amyloid precursor protein mRNA is up-regulated by interleukin-1 through 5’-untranslated region sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6421–6431. 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. T., Randall J. D., Cahill C. M., Eder P. S., Huang X., Gunshin H., et al. (2002). An iron-responsive element type II in the 5’-untranslated region of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein transcript. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45518–45528. 10.1074/jbc.M207435200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A., Pace L., Tempesta B., Lavecchia A. M., Macheda T., Bedse G., et al. (2014). Depressive-like behavior is paired to monoaminergic alteration in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18, pyu020. 10.1093/ijnp/pyu020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R. M. (2000). Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 925–935. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi C., Bronzuoli M. R., Facchinetti R., Pace L., Ferraro L., Broad K. D., et al. (2018). Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide rescues learning and memory impairments in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by exerting anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 32. 10.1038/s41398-017-0076-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepehry A. A., Lee P. E., Hsiung G. Y., Beattie B. L., Jacova C. (2012). Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease with comorbid depression: a meta-analysis of depression and cognitive outcomes. Drugs Aging 29, 793–806. 10.1007/s40266-012-0012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serviddio G., Romano A. D., Cassano T., Bellanti F., Altomare E., Vendemiale G. (2011). Principles and therapeutic relevance for targeting mitochondria in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 17, 2036–2055. 10.2174/138161211796904740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N., Tramutola A., Lanzillotta C., Arena A., Blarzino C., Cassano T., et al. (2019). Loss of biliverdin reductase-A favors Tau hyper-phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 125, 176–189. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim Y. S., Yang D. W. (2006). Depression as prognostic factor: 6 months follow-up in a geriatric institution. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 43, 277–283. 10.1016/j.archger.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y., Chen A. C., Nakagawa S., Russell D. S., Duman R. S. (2002). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression. J. Neurosci. 22, 3251–3261. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03251.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak J. A., Lewis D. R., Wiegand S. J., Lindsay R. M. (1997). Antidepressant-like effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 56, 131–137. 10.1016/S0091-3057(96)00169-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck C. E., Kukull W. A., Brenner D. E., Bowen J. D., McCormick W. C., Teri L., et al. (1995). History of depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiology 6, 366–369. 10.1097/00001648-199507000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani M., Liguri G. (2009). Cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease: unresolved questions. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 6, 15–29. 10.2174/156720509787313899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens D. C., Plassman B. L., Helms M. J., Welsh-Bohmer K. A., Saunders A. M., Breitner J. C. (1997). A twin study of late-onset depression and apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 41, 851–856. 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00247-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez E. C., Lewis J. G., Krishnan R. R., Young K. H. (2004). Enhanced expression of cytokines and chemokines by blood monocytes to in vitro lipopolysaccharide stimulation are associated with hostility and severity of depressive symptoms in healthy women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 1119–1128. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Mwamburi D. M., Bungay K., Prasad J., Yee J., Lin Y. M., et al. (2007). Depression, antidepressants, and plasma amyloid beta (Beta) peptides in those elderly who do not have cardiovascular disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 62, 1413–1417. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaab D. F., Bao A. M., Lucassen P. J. (2005). The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res. Rev. 4, 141–194. 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Town T., Paris D., Mori T., Suo Z., Crawford F., et al. (1999). Microglial activation resulting from CD40-CD40L interaction after beta-amyloid stimulation. Science 286, 2352–2355. 10.1126/science.286.5448.2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramutola A., Sharma N., Barone E., Lanzillotta C., Castellani A., Iavarone F., et al. (2018). Proteomic identification of altered protein O-GlcNAcylation in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1864, 3309–3321. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S., Ahl M., Bush A., Westaway D., Huang X., Rogers J. T. (2005). Pilot study of the reducing effect on amyloidosis in vivo by three FDA pre-approved drugs via the Alzheimer’s APP 5’ untranslated region. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2, 249–254. 10.2174/1567205053585855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S., Ahl M., Cho H. H., Bandyopadhyay S., Cuny G. D., Bush A. I., et al. (2006). RNA therapeutics directed to the non coding regions of APP mRNA, in vivo anti-amyloid efficacy of paroxetine, erythromycin, and N-acetyl cysteine. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 221–227. 10.2174/156720506777632835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Mottram P., Sivanranthan A., Nightingale A. (2001). Antidepressant versus placebo for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, CD000561. 10.1002/14651858.CD000561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuwongse S., Chang R. C., Law A. C. (2010). The putative neurodegenerative links between depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 91, 362–375. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko G. S., Moossy J., Kopp U. (1990). Neurochemical correlates of major depression in primary dementia. Arch. Neurol. 47, 209–214 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530020117023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]