Abstract

Background:

Delusions affect approximately a third of Alzheimer’s disease(AD) patients and are associated with poor outcomes. Previous studies investigating the neuroanatomical correlates of delusions have yet to reach a consensus, with findings of reduced volume across all the lobes, particularly in frontal regions. The current study examined the grey matter(GM) differences associated with delusions in AD.

Methods:

Using voxel-based morphometry(VBM), we assessed GM for 23 AD patients who developed delusions(AD+D) and 36 comparable AD patients who did not develop delusions(AD-D) at baseline and follow up. ANOVA was used to identify consistent differences between AD+D and AD-D patients across both timepoints(main effect of group), consistent changes from baseline to follow up(main effect of time) and differential changes between AD+D and AD-D over time(interaction of group and time). All data were obtained from the NACC database.

Results:

The AD+D group had consistently lower frontal GM volume, although both groups showed decreased GM in fronto-temporal brain regions over time. An interaction was observed between delusions and longitudinal change, with AD+D patients having significantly elevated GM in predominantly temporal areas at baseline assessment, which had declined to become significantly lower than the AD-D group at follow-up.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that although individuals with and without delusion show long-term GM decreases, there are specific volumetric markers that distinguish patients with delusion from those without, before and after the onset of delusions. Specifically, the decline of GM in temporal areas that were elevated prior to the onset of delusion may be involved in the manifestation of delusions.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, delusion, voxel-based morphometry, imaging, psychosis

Introduction:

Delusions are common in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), affecting an estimated one in three patients over the course of the illness(1). Delusions are associated with worse prognosis, including greater cognitive and functional impairments(2), a more rapid cognitive decline(3), increased caregiver burden(4), and a higher rate of institutional care(5). Despite the high prevalence and the link with adverse outcomes, the pathophysiological and neuroanatomical correlates of delusions are not well established in this patient population. We aimed to better understand the natural progression of AD in patients with delusions, which could potentially inform outcome.

Studies investigating the neuroanatomical markers of delusions in AD have reported variable results. Studies using computed tomography (CT) scans have initially found delusions in AD to be related right frontal lobe degeneration(6). More recent studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has greater tissue contrast, have localized frontal deficits with greater specificity, including the orbitofrontal cortex, inferior and medial frontal gyrus, and precentral gyrus, but also implicated multiple additional regions such as the hippocampus, superior temporal lobule, inferior parietal lobule (IPL), claustrum, insula, occipital lobe, anterior cingulate, and thalamus(6–8). Overall, different findings have been reported across studies, with only a few consistent regions.

There have been very few longitudinal studies looking at the changes over time(9, 10). Rafii and colleagues found that psychotic symptom severity correlated with increased rates of atrophy in the anterior cingulate, entorhinal, lateral frontal, orbitofrontal, and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) over one year(9). However, the sample was somewhat heterogeneous, consisting of patients with MCI and AD, and with broadly defined psychosis consisting of delusion, hallucination, agitation, wandering, or any patients who used anti-psychotic medications. As different psychosis endophenotypes may have different neural mechanisms, the results may not be delusion-specific. Lastly, the subjects were already psychotic at baseline, so the changes over time did not correspond to the development of delusions. In the only other longitudinal study, our group compared pre- and post-delusional MRI scans in patients with MCI at baseline and found decreased grey matter(GM) volumes in the cerebellum and left posterior hemisphere following the onset of delusions(10). However, while 17 patients progressed to AD, 7 remained at the MCI stage at the post-delusional scan. It is possible that the structural changes reflected AD progression rather than the development of delusions, so it is important to compare the GM changes to a control AD group who do not develop psychosis. Overall, the most consistent regions associated with delusions from MRI studies appear to be the frontal cortex (orbitofrontal, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal cortex), parietal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortices without preferences with respect to laterality.

The current study examined the patterns of GM changes associated with the development of delusions, by comparing pre- and post-delusional MRI scans. Using voxel-based morphometry (VBM), GM was assessed for patients with delusions compare to a control group of AD patients who did not develop delusions during the course of follow-up. Analyses included identifying the effects of delusional status and time, as well as their interactions, on GM volume. Understanding the structural brain markers associated with delusions will inform us if abnormalities in specific brain regions may be responsible for delusions.

Methods:

Data Source

Clinical data and MRIs were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database(11). The current data were collected from 29 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) collected between September 2005 and June 2015. T1-weighted magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) MRI sequences acquired from 1.5 tesla scanners were downloaded from the NACC server. All patients enrolled in the study received an in-person clinical evaluation and were followed up annually where possible.

Patients

Participants must have had an AD diagnosis at baseline(12) and have had multiple T1 MRI scans that were each within 6 months of a clinical visit. Delusional participants must have had an MRI both before and after the clinical onset of their delusions, while nondelusional participants must have had MRIs over a similar time span. Individuals with significant neurological comorbidities were excluded. The presence of delusions was determined from the delusional item on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire (NPI-Q) completed by an informant(13). Fifty-nine (59) patients were identified from the database, including twenty-three (23) patients who developed delusions over the course of follow-up and thirty-six (36) patients who did not develop delusions. None of the patients endorsed hallucinatory symptoms at the scan visits. The St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board approved the current study.

MRI estimation of grey matter volume

Analysis of the pre-processed 1.5T structural T1 MR images from the NACC server was conducted using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to assess grey matter tissue. This was done using the FMRIB Software Library VBM protocol (FSLVBM; https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSLVBM) and software developed in-house. This is a widely-used morphometric approach for characterizing differences in grey matter without requiring a priori selection of brain areas of interest. To perform VBM, the brains from all scans were extracted using a semi-automated process: FSL bet2 was used to extract the brains, and each brain was subsequently inspected and manually adjusted in cases of segmentation error. The FSL fast algorithm was then used to segment brain tissue, providing individual grey matter (GM) maps.

A study-specific GM template was created by registering all GM maps to FSL’s 152T1 probabilistic GM template (2mm3 resolution) using the iterative FSLVBM procedure. This produces a reference template that is representative of the study cohort, in order to measure GM deformations relative to the population norm. This consisted of (1) an initial coarse estimate of the template, by performing affine alignment to template with FSL flirt, averaging the transformed GM maps, then re-averaging with flipped left/right orientations to symmetrize the template. This was followed by (2) a more refined estimate of the template, via nonlinear alignment to the affine template using FSL fnirt, averaging the transformed GM maps, then re-averaging with flipped left/right orientations to symmetrize the template.

All GM maps were then aligned to this new template using FSL fnirt, and each voxel GM value was multiplied with the local Jacobian of the transformation, to account for stretch/compression of tissue during co-registration. Finally, a Gaussian smoothing kernel of 4 mm full-width at half maximum (FWHM) was applied to control for minor local variations in cortical structure. A mask of regions with likelihood >0.33 (greater than chance probability, based on a three-tissue mixture model) was then obtained to restrict analyses to gray matter voxels.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Group differences in demographics (age, gender, education, and handedness) were assessed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests (continuous variables) or chi-square (χ2) test of independence (binary variables). In addition, cognitive tests including Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) were compared between groups, at both baseline and follow-up visits, using Mann-Whitney tests. For all tests, significance was set at p<0.05. As the comparisons were used to determine comparability between the two cohorts, multiple comparison corrections were not used to provide a more conservative test. To test for possible interactions of delusion status and time on clinical variables of CDR and MMSE, 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was fitted to each variable following a Box-Cox transform, and F-statistics evaluated for the group × time interaction terms.

Analysis of neuroimaging data

In order to characterize fixed and longitudinal effects of delusional status on GM, a 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was fitted at each brain voxel, analyzing the factors of delusion group (AD+D vs. AD-D) and time (pre vs. post). F-statistic maps were obtained for main effects of group, time, and group × time interaction. Thresholding of F-statistic maps were conducted at a p<0.005 voxelwise, followed by cluster-size adjustment for multiple comparisons at p=0.05, using AFNI 3dFWHMx (https://afni.nimh.nih.gov) to estimate spatial smoothness on the set of GM maps, and 3dClustSim to estimate minimum cluster size. For both main effects and interaction, after testing for a consistent direction of effect, the mean response was plotted, averaged over all significant GM voxels, along with post hoc t-statistics.

Supplemental analyses examined the relationship between GM and clinical covariates of MMSE and CDR. Preliminary testing determined that the fixed-effect factors (delusion group, time) were highly correlated with MMSE and CDR (ρ=0.39 and 0.49 respectively, canonical correlation analyses), and they were therefore not used to control for cognitive effects in the ANOVA model(14). Instead, a General Linear Model was used to regress (1) baseline MMSE and CDR against baseline GM, along with (2) longitudinal change in MMSE and CDR against longitudinal change in GM, and the corresponding t-statistic maps were calculated. These analyses were conducted separately within both delusional and non-delusional groups, thereby avoiding any confounding effects of the task design.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Over the course of follow-up, twenty-three (23) patients developed delusions while thirty-six (36) patients did not. Baseline and follow-up demographic data are summarized in Table 1. The delusional and non-delusional cohorts did not significantly differ in age, time between the scans, gender, number of years of education, handedness, or Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) at the baseline visit, but baseline global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) was significantly higher in the delusional subset. There were no differences on any demographic or clinical data at the follow-up visit between the two cohorts. However based on repeated-measures ANOVA, no significant group × time interactions effects were seen on either MMSE (F(1,57)=0.02, p=0.91) or CDR (F(1,57)=1.18, p=0.282).

Table 1.

Demographic data for delusional and non-delusional cohorts at the baseline scan and at the follow-up scan

| Delusional subset (n=23) | Non-delusional subset (n=36) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-delusion Visit (Dpre) | Post-Delusion visit (Dpost) | Baseline visit (Npre) | Follow-up visit (Npost) | Baseline visit | Follow-up visit | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 78.0 ± 6.1 (61–91; median 79) | 81.3 ± 9.6 (65–92; median 82) | 77.5 ± 9.6 (50–93; median 79.0) | 80.0 ± 9.8 (51–94; median 82.0) | U=392.0, p=0.949 | U=413.5, p=0.994 |

| Change in age between scans | 2.8 ± 1.3 (1–6; median 3) | 2.8 ± 1.9 (0–10; median 2) | U=348.5, p=0.432 | |||

| Days between scans | 1074.8 ± 504.1 | 961.8 ± 651.2 | U=289.0, p=0.141 | |||

| Gender | 19 F; 4 M | 27 F; 9 M | χ2(1, N=59)=0.473, p=0.492 | |||

| Education (mean ± SD) | 12.8 ± 2.8 | 14.2 ± 3.3 | U=324.5, p=0.148 | |||

| Handedness | 21 Right; 1 Left; 1 Ambidextrous | 34 Right; 2 Left | χ2(1, N=59)=0.028, p=0.866 | |||

| MMSE | 23.5 ± 3.9 | 18.09 ± 6.8 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | 20.7 ± 5.7 | U=212 p=0.111 | U=226.5, p=0.078 |

| Global CDR | 0.72 ± 0.31 | 1.25 ± 1.02 | 0.54 ± 0.38 | 0.68 ± 0.40 | U=160.5, p=0.018* | U=239.5, p=0.326 |

Analysis of Neuroimaging data

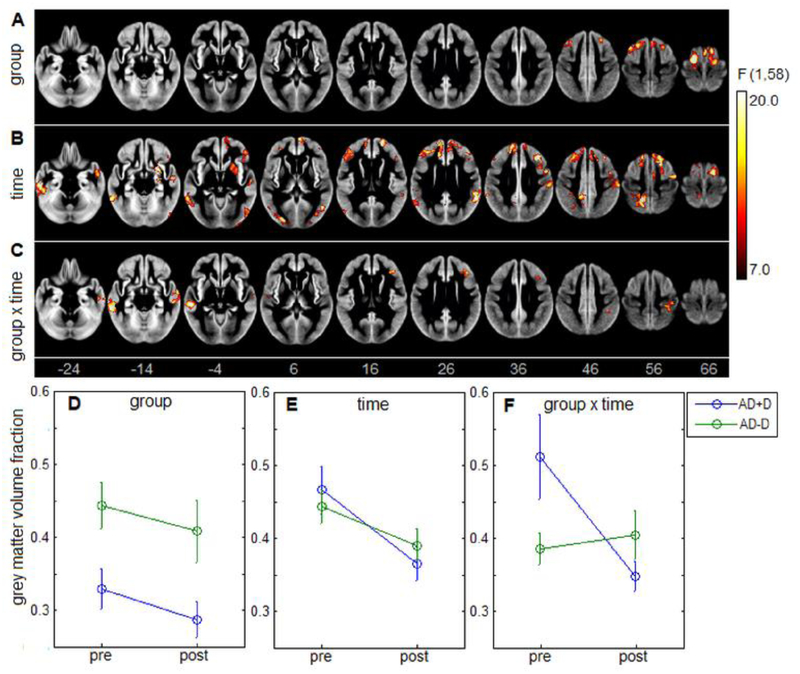

The ANOVA identified significant main effects of delusion group (AD+D vs AD-D), time (pre vs. post), and group × time interaction. Significant brain areas are displayed in Figure 1 A–C, obtained after cluster-size thresholding. The main effect of delusion is depicted Fig. 1A, and is localized frontally, with clusters centered on precentral and middle frontal gyri, along with the supplementary motor area (Table 2). In these areas, post hoc testing found uniformly lower GM volume in AD+D group, with the mean effect plotted in Fig. 1D (mean difference and 95% CI: −0.118, [−0.167, −0.069]; t(57) = −4.86, p<0.001). Hence, individuals with delusion have consistent lower GM volume in these regions at both timepoints.

Figure 1:

results of 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA on for grey matter volume, with maps showing (A) main effect of group (AD+D vs. AD-D), (B) main effect of time (pre vs. post), and (C) group × time interaction. For significant brain areas, the corresponding mean grey matter values are plotted for each group and timepoint, along with normal 95% confidence interval errorbars (D-F).

Table 2:

Significant clusters exhibiting a main effect of group (AD+D vs. AD-D), ordered by decreasing cluster size. Brain regions for center of mass are based on Automated Anatomical Labelling (AAL) atlas and Brodman Areas (BA).

| Cluster | Center of Mass | Brain Region | Clustersize (mm3) | PeakValue F(1,58) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 8 | 62 | Supp Motor Area R / BA=6 | 8904 | 24.72 |

| 2 | −16 | −8 | 68 | Precentral L / BA=6 | 5912 | 37.67 |

| 3 | −28 | 22 | 54 | Frontal Mid L / BA=8 | 3440 | 20.86 |

The main effect of time, shown in Fig. 1B, is considerably more spatially extensive than the effect of group, with clusters throughout the frontal and temporal lobes along with single clusters in the precuneus, occipital lobe, cerebellum and putamen (Table 3). Within these regions, post hoc testing found uniformly decreased GM volume over time, with mean effects shown in Fig. 1E (mean difference and 95% CI: −0.072, [−0.051, −0.092]; t(58)=−6.90, p<0.001). These areas consistently show volumetric decrease over time, irrespective of delusion status.

Table 3:

Significant clusters exhibiting a main effect of time (pre vs. post), ordered by decreasing cluster size

| Cluster | Center of Mass | Brain Region | Clustersize (mm3) | PeakValue F(1,58) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −24 | 38 | 34 | Frontal Sup L / BA=9 | 17944 | 22.88 |

| 2 | 16 | 28 | 48 | Frontal Sup R / BA=32 | 14248 | 36.8 |

| 3 | 46 | 6 | 38 | Precentral R / BA=6 | 10104 | 30.53 |

| 4 | −58 | −34 | −20 | Temporal Inf L / BA=20 | 9280 | 25.82 |

| 5 | −14 | −50 | 50 | Precuneus L | 9128 | 28.27 |

| 6 | −46 | −64 | 18 | Temporal Mid L / BA=39 | 5064 | 20.96 |

| 7 | 52 | −2 | −24 | Temporal Mid R / BA=21 | 4608 | 22.12 |

| 8 | 42 | −76 | 0 | Occipital Inf R / BA=19 | 4536 | 23.94 |

| 9 | 26 | −74 | −46 | Cerebelum 7b R | 3778 | 22.82 |

| 10 | 26 | 6 | −8 | Putamen R / BA=48 | 3774 | 30.27 |

| 11 | 58 | −44 | 24 | Temporal Sup R / BA=42 | 3344 | 30.99 |

| 12 | 10 | 62 | 2 | Frontal Sup Medial R / BA=10 | 2576 | 22.02 |

| 13 | 46 | 36 | −4 | Frontal Inf Orb R / BA=45 | 2392 | 16.18 |

An interaction effect between group and time is depicted in Fig. 1C, with clusters predominantly in middle temporal gyri, but with additional clusters in the inferior frontal and postcentral gyrus (Table 4). For these brain regions, the mean effect is displayed in Fig. 1F. A disordinal interaction is seen, where GM volume is significantly higher for AD+D than AD-D at initial scan (mean and 95% CI: 0.126, [0.071, 0.018]; t(57)=4.58, p<0.001), but becomes significantly lower at follow-up (−0.058, [−0.104, −0.011]; t(57)=−2.48, p=0.016). This effect is due to decreasing cortical volume in the AD+D group (mean and 95% CI: −0.165, [−0.234, −0.095]; t(22)=−4.91, p<0.001) as the AD-D group shows no significant change over time in these regions (mean and 95% CI: 0.019, [−0.016, 0.053]; t(35)=1.10, p=0.277).

Table 4:

Significant clusters exhibiting a group × time interaction effect, ordered by decreasing cluster size

| Cluster | Center of Mass | Brain Region | Clustersize (mm^3) | PeakValue F(1,58) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −58 | −28 | −10 | Temporal Mid L / BA=20 | 5120 | 23.95 |

| 2 | 60 | −14 | −14 | Temporal Mid R / BA=21 | 3352 | 22.88 |

| 3 | 38 | 30 | 26 | Frontal Inf Tri R / BA=45 | 2416 | 22.32 |

| 4 | 36 | −32 | 54 | Postcentral R / BA=3 | 2256 | 16.47 |

Analysis accounting for disease severity

Supplemental analyses tested for a relationship between MMSE and CDR scores and neuroimaging measures of GM, regressing baseline MMSE and CDR against baseline GM, along with the longitudinal change in MMSE and CDR against the longitudinal change in GM. For both delusional and non-delusional groups, no significant effects were observed after adjusting for multiple comparisons via cluster-size thresholding.

Discussion

The current study investigated the associations of delusions, time, as well as their interaction on GM volume in AD patients. Although the delusional group had consistently lower frontal GM volume than non-delusional patients, both delusional and non-delusional groups showed decreased GM volume in fronto-temporal brain regions over time (with an average interval of 2.8 years). Interestingly, there was a significant interaction between delusional status and time, with delusional patients initially at the baseline scan having significantly greater GM volume in predominantly temporal areas, which then showed accelerated atrophy to become significantly lower in volume than the non-delusional group at follow-up. This particularly interesting, given that the examined clinical tests of cognition (i.e., MMSE, CDR) do not show such an interaction effect between delusion status and time. This suggests that the enhanced degree of longitudinal grey matter atrophy in delusional patients may not be captured in standard clinical tests. The findings indicate that accelerated atrophy of temporal regions represents a pattern unique to the delusional group that coincides with the onset of delusional symptoms.

The finding of atrophy in the multiple spatially distributed areas in both groups over time is consistent with typical AD progression(15). The delusional group however, showed accelerated atrophy in the temporal lobes, which suggests that these patients undergo a more rapid disease progression than non-delusional patients. This is consistent with previous studies reporting accelerated cognitive and functional decline associated with psychosis in AD (16, 17). Our study is novel in being the first study to isolate increased temporal atrophy specific to the onset of delusional manifestation.

The association between delusions and fronto-temporal abnormalities corroborates several functional and structural neuroimaging studies showing altered metabolism and decreased volumes in these areas, respectively, in relation to delusions in AD (6, 18, 19). Reduced volume in the frontal lobes of delusional patients has been consistently found across CT studies, and has been demonstrated in several MRI studies(6–8). Within the frontal cortex, MRI studies have localized more specific structures, with the most commonly reported areas being the orbitofrontal cortex(8, 9, 19, 20) and inferior frontal cortex(7, 20, 21). The frontal cortex is responsible for integrating multimodal inputs and internal states in directing behavioural output, especially when the stimuli are ambiguous, which requires selection between alternative interpretive options(22). It is possible that frontal lobe atrophy can cause cues in the environment to be misinterpreted, generating illogical conclusions rather than contextually appropriate responses. Loss of frontal volume is also consistent with the theory of hypofrontality, which posits that frontal deficits that lead to poor insight may be an underlying cause of delusions(23). Poor insight could contribute to the sustainment of these delusions despite contradictory evidence. Atrophy of the temporal lobes could impair memory functions, which could contribute to the evolution of delusional symptoms by crediting non-autobiographical events, such as internal imagery, as memories. Supporting this notion, impaired memory and insight have been found clinically in AD patients with delusions(24, 25).

At the baseline pre-delusional scan, the delusional cohort exhibited higher GM volume particularly in the temporal areas compared to the non-delusional cohort. Increased GM density could represent structural damage, in which a compensatory mechanism is initiated to remodel the cortically damaged regions (26). It is possible that there may be brain reconstruction and compensation at earlier stages, but ultimately atrophies of these areas result in abnormal behavioral symptoms. An alternative explanation could be that subjects with delusions have a lower cognitive reserve than their non-delusional counterparts, given their higher CDR scores despite greater GM volume at baseline (27).

Most of the literature investigating structural abnormalities associated with delusions in AD has compared differences after delusions have manifested, but differences prior to the clinical manifestation of delusions were seldom investigated. In the only study to date looking at baseline differences, Nakaaki and colleagues found that, prior to the onset of delusions, patients who later develop delusions had lower GM volumes in the bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, the right orbitofrontal cortex, bilateral inferior frontal gyrus, the anterior cingulate, and the left insula, but greater GM volumes in the right cerebellum, left lingual gyrus, left inferior temporal gyrus, and left occipital cortex compared to patients who did not develop delusions(20). Similar to the findings of Nakaaki et al., we found greater GM volume in the temporal lobes predating the development of delusions, although we did not find significant differences in other regions found in their study. Nakaaki et al. however, only followed subjects for two years, so it is possible that some of the subjects in the non-delusional group later developed delusions.

There were some limitations to our study. Firstly, we did not separate delusions into subtypes. There is evidence to suggest that delusional subtypes have separate etiologies and neural correlates(6, 28). Unfortunately, the delusional data from NACC is determined using the NPI-Q, which does not distinguish the type of delusions. Secondly, we did not investigate the effect of other factors on GM change, such as medication use (in particular antipsychotic medications), genetics, or comorbid NPS. Thirdly, the majority of our sample consisted of females, which could have introduced a gender bias. The prevalence of AD, as well as psychosis in AD, are higher among females(29), which likely influenced the sample. Whitehead et al. previously found reduced cortical thickness in the left medial orbitofrontal and left superior temporal regions in female AD patients with paranoid delusions, but the effect was not found in male patients(19). Therefore, GM atrophy associated with delusions could affect the genders differently. Separating our analysis by gender wasn’t feasible due to low sample size so we could not make any conclusions regarding gender. However, the delusional and non-delusional groups were comparable in the proportion of females, mitigating any confounds.

The present results employed the FSLVBM protocol and included the generation of a study-specific template before realigning GM maps. To maximize robustness of the group template, the GM maps from all subjects and timepoints were used. However, alternative procedures may yield different results. For example, longitudinal morphometric analyses, whether voxel-based or driven by regions or interest(30), may yield greater sensitivity to longitudinal changes. Different choices of nonlinear registration algorithm may also affect sensitivity to GM atrophy(31). Lastly, the NACC database combines data from several ADCs, the image acquisition protocols and MRI scanners can vary by study center, potentially increasing variability in the data. Estimation therefore may be improved using models that account for site-specific effects. These issues should be examined in more detail in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we investigated the GM markers associated with delusions. The findings support that delusional and non-delusional AD patients have distinct volumetric markers before, and after the onset of delusions. Patients who developed delusions showed increased atrophy of the temporal lobes, which were initially elevated prior to the onset of delusions, compared to patients who did not develop delusions. This specific pattern of atrophy may be a key contributor to the manifestation of delusions.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Tsz Wai Bentley Lo for helping with the data processing.

Affiliation: University of Toronto (campus: Scarborough campus)

*The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD).

Disclosures and Acknowledgments:

This study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [Grant number 313912].

No Disclosures to Report

Footnotes

Previous presentation:

This paper has been presented as an abstract at the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) 2016 annual meeting (March 17–20th, 2016), and at the Canadian Conference on Dementia (CCD) 8th meeting (Oct 1–3, 2015).

References

- 1.Ropacki SA,Jeste DV: Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005; 162:2022–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer CE, Ismail Z,Schweizer TA: Delusions increase functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord 2012; 33:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet RA, Hamilton RL, Lopez OL, et al. : Psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease are not associated with more severe neuropathologic features. Int. Psychogeriatr 2000; 12:547–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer CE, Ismail Z,Schweizer TA: Impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegenerative Disease Management 2012; 2:269–277 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng TW, Chen TF, Yip PK, et al. : Comparison of behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease among institution residents and memory clinic outpatients. Int. Psychogeriatr 2009; 21:1134–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail Z, Nguyen MQ, Fischer CE, et al. : Neuroimaging of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Res. 2012; 202:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ting WK, Fischer CE, Millikin CP, et al. : Grey matter atrophy in mild cognitive impairment / early Alzheimer disease associated with delusions: a voxel-based morphometry study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015; 12:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makovac E, Serra L, Spano B, et al. : Different Patterns of Correlation between Grey and White Matter Integrity Account for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016; 50:591–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafii MS, Taylor CS, Kim HT, et al. : Neuropsychiatric symptoms and regional neocortical atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2014; 29:159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer CE, Ting WK, Millikin CP, et al. : Gray matter atrophy in patients with mild cognitive impairment/Alzheimer’s disease over the course of developing delusions. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016; 31:76–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. : The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord 2007; 21:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. : The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. : The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller GA,Chapman JP: Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J. Abnorm. Psychol 2001; 110:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Migliaccio R, Agosta F, Possin KL, et al. : Mapping the Progression of Atrophy in Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015; 46:351–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emanuel JE, Lopez OL, Houck PR, et al. : Trajectory of cognitive decline as a predictor of psychosis in early Alzheimer disease in the cardiovascular health study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011; 19:160–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters ME, Schwartz S, Han D, et al. : Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and death: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015; 172:460–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sultzer DL, Leskin LP, Melrose RJ, et al. : Neurobiology of delusions, memory, and insight in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014; 22:1346–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehead D, Tunnard C, Hurt C, et al. : Frontotemporal atrophy associated with paranoid delusions in women with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr 2012; 24:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakaaki S, Sato J, Torii K, et al. : Neuroanatomical abnormalities before onset of delusions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a voxel-based morphometry study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013; 9:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruen PD, McGeown WJ, Shanks MF, et al. : Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2008; 131:2455–2463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller EK,Cohen JD: An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 2001; 24:167–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harwood DG, Sultzer DL, Feil D, et al. : Frontal lobe hypometabolism and impaired insight in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005; 13:934–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazui H, Hirono N, Hashimoto M, et al. : Symptoms underlying unawareness of memory impairment in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2006; 19:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppel J, Sunday S, Goldberg TE, et al. : Psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with frontal metabolic impairment and accelerated decline in working memory: findings from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014; 22:698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Cai P, Shi L, et al. : Voxel-based morphometry of the visual-related cortex in primary open angle glaucoma. Curr. Eye Res. 2012; 37:794–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern Y: What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc 2002; 8:448–460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomura K, Kazui H, Wada T, et al. : Classification of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease and their neural correlates. Psychogeriatrics 2012; 12:200–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. : Delusions of Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2003; 18:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu RS, Lemieux L, Bell GS, et al. : A longitudinal study of brain morphometrics using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and difference image analysis. Neuroimage 2003; 20:22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein A, Andersson J, Ardekani BA, et al. : Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. Neuroimage 2009; 46:786–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]