Visual Abstract

Keywords: advanced glycation end-product; cardiovascular mortality; renal transplantation; oxidative stress; endothelial dysfunction; humans; area under curve; ROC curve; Glycation End Products, Advanced; confidence interval; Transplantation, Homologous; kidney transplantation; allografts; kidney diseases; kidney disease; fibrosis; biopsy; kidney biopsy; magnetic resonance imaging; hypoxia; glomerulonephritis; oxygen; cardiovascular disease; cohort studies

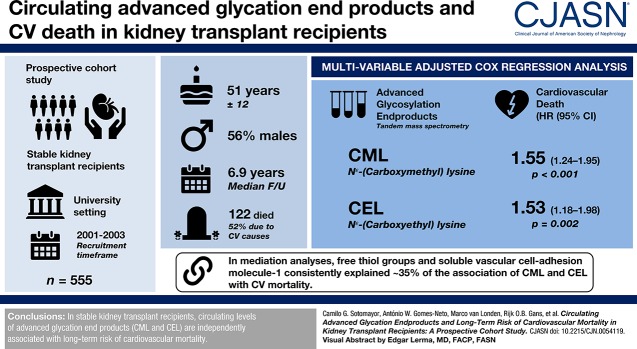

Abstract

Background and objectives

In kidney transplant recipients, elevated circulating advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) are the result of increased formation and decreased kidney clearance. AGEs trigger several intracellular mechanisms that ultimately yield excess cardiovascular disease. We hypothesized that, in stable kidney transplant recipients, circulating AGEs are associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality, and that such a relationship is mediated by inflammatory, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction biomarkers.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Prospective cohort study of stable kidney transplant recipients recruited between 2001 and 2003 in a university setting. We performed multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analyses to assess the association of AGEs (i.e., Nε-[Carboxymethyl]lysine (CML) and Nε-[Carboxyethyl]lysine (CEL), measured by tandem mass spectrometry) with cardiovascular mortality. Mediation analyses were performed according to Preacher and Hayes’s procedure.

Results

We included 555 kidney transplant recipients (age 51±12 years, 56% men). During a median follow-up of 6.9 years, 122 kidney transplant recipients died (52% deaths were due to cardiovascular causes). CML and CEL concentrations were directly associated with cardiovascular mortality (respectively, hazard ratio, 1.55; 95% confidence interval, 1.24 to 1.95; P<0.001; and hazard ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval 1.18 to 1.98; P=0.002), independent of age, diabetes, smoking status, body mass index, eGFR and proteinuria. Further adjustments, including cardiovascular history, did not materially change these findings. In mediation analyses, free thiol groups and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 consistently explained approximately 35% of the association of CML and CEL with cardiovascular mortality.

Conclusions

In stable kidney transplant recipients, circulating levels of AGEs are independently associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2019_09_17_CJN00540119.mp3

Introduction

Short-term outcomes of kidney transplantation have markedly improved over recent decades. However, ensuring favorable long-term outcomes has been a greater challenge. Despite progressive improvements in 1-year survival rates, kidney transplant recipients are at particularly high risk of premature mortality because of cardiovascular disease (1). Traditional cardiovascular risk factors, however, do not suffice to account for the excess of cardiovascular disease in stable kidney transplant recipients (2,3).

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are a heterogeneous group of compounds derived from nonenzymatic glycation of amino acids, lipids, and nucleic acids in the presence of sugars, through a complex sequence of reactions referred to as the Maillard reaction (4). Elevated circulating AGEs are the result of both enhanced formation in diseases associated with high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress, and decreased kidney clearance, such as in CKD (5). Upon binding to AGE-specific receptor (RAGE), AGEs activate several signaling pathways that further amplify inflammatory and oxidative stress responses, and regulate the transcription of adhesion molecules (6). AGE-RAGE‒mediated endothelial dysfunction in patients with CKD has been proposed to at least partly explain subsequent cardiovascular disease and excess of cardiovascular mortality, independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (7–9).

In patients with ESKD, clinical studies have shown the adverse cardiovascular and survival effects of AGEs (10,11). In kidney transplant recipients, the hypothesis that AGEs play a role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease may be supported by evidence that connects indirect and nonspecific measurements of AGEs with risk factors of cardiovascular disease (12,13). A strong body of evidence on the general theory of circulating AGE pathology supports its pivotal role in the initiation and progression of cardiovascular disease, which, in turn, is the leading individual cause of premature mortality after a successful kidney transplantation. To date, however, no study has assessed whether specific circulating concentrations of AGEs in stable kidney transplant recipients may be prospectively associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality.

Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine (CML), one of the best-characterized AGEs and one of the most abundant in humans, is a major AGE that can be formed on proteins by both glycation and lipid peroxidation pathways (14). Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL) is a homolog of CML, formed by the reaction of methylglyoxal with lysine residues in proteins (15). By binding to RAGE, these two main glycation free adducts in patients with CKD stimulate inflammation, oxidative stress, and lead to endothelial dysfunction through induction of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in endothelial cells (16,17).

We therefore conducted this study to identify independent determinants of circulating concentrations of the AGEs CML and CEL, in the particular setting of stable kidney transplant recipients; and evaluate whether circulating CML and CEL concentrations are associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality in stable kidney transplant recipients. Furthermore, we sought to test whether the aforementioned potential association is mediated by inflammatory, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction biomarkers. In secondary analyses we aimed to study the association of circulating CML and CEL with long-term risk of all-cause mortality.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

In this prospective cohort study, all adult kidney transplant recipients with a functioning graft ≥1 year, without known or apparent systemic illnesses (i.e., malignancies, opportunistic infections), who visited the outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Groningen (The Netherlands) between August 2001 and July 2003, were considered eligible to participate. A total of 606 out of 847 kidney transplant recipients provided written informed consent. The group that did not provide informed consent was comparable with the group that did provide informed consent with respect to age, sex, body mass index, serum creatinine, and proteinuria (18). Patients missing CML or CEL measurements were excluded from the analyses, resulting in 555 kidney transplant recipients, of whom data are presented here. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Medical Ethical Committee 01/039) and conducted in accordance with Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. The cohort study is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (TransplantLines Insulin Resistance and Inflammation Biobank and Cohort Study, identifier NCT03272854). Full details on the study design have been previously reported (19).

The primary end point was cardiovascular mortality. Information on the cause of death was derived from patients’ medical records and was assessed by a nephrologist. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death, and coded according to a previously specified list of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (codes 410–447) as described previously (20). The secondary end point was all-cause mortality. Follow-up was performed for a median of 6.9 (interquartile range [IQR], 6.2–7.2) years. Collection of these data are ensured by the continuous surveillance system of the outpatient clinic of our university hospital, in which patients visit the outpatient clinic with declining frequency, in accordance with the guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation (2). General practitioners or referring nephrologists were contacted if the status of a patient was unknown. No patients were lost to follow-up.

Data Collection

Medical history and medication use were extracted from the Groningen Kidney Transplant Database. Cardiovascular history was considered positive if participants had a previous myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, or cerebrovascular accident. Lifestyle, smoking status, and alcohol use were obtained using a self-report questionnaire at inclusion. Physical activity was estimated by using metabolic equivalents of task (21). eGFR was calculated applying the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation (22). The measurement of clinical and laboratory parameters has been described in detail (23). To create a biobank and perform extensive laboratory phenotyping, including AGE measurements, blood samples were drawn at inclusion at baseline, in the morning after an 8- to 12-hour overnight fast. Plasma and urine creatinine concentrations were determined using a modified version of the Jaffé method (MEGA AU510; Merck Diagnostica). This method is not traceable by isotope dilution mass spectrometry and therefore not standardized; use of it usually results in an overestimation of serum creatinine, and therefore an underestimation of the GFR (24). Derivatized CML and CEL were directly analyzed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography (Acquity UPLC; Waters, Milford, MA) as detailed in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), STATA 14.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX), and R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data are expressed as mean±SD for normally distributed variables, and as median (IQR) for skewed variables. Categorical data are expressed as n (percentage). Hazard ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals. In all analyses, a two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Age-, sex-, and eGFR-adjusted linear regression analyses were performed to examine the association of baseline characteristics with circulating CML and CEL. Standardized β coefficients represent the difference (in SD) in CML or CEL per 1 SD increment in continuous characteristics or for categorical characteristics the difference (in SD) in CML or CEL compared with the implied reference group. Residuals were checked for normality and natural log-transformed when appropriate. To study in an integrated manner what baseline variables were independently associated with and were determinants of circulating CML and CEL, we performed forward selection of baseline characteristics according to preceding multivariable linear regression analyses (P value for inclusion <0.2), followed by stepwise backward multivariable linear regression analyses (P value for exclusion <0.05). CML and CEL were, respectively, precluded for the analyses of determinants of circulating CEL and CML; thus, overall R2 of the final models were calculated without inclusion of these variables.

To study the prospective association of CML and CEL with outcomes, Cox proportional-hazards regression models were fitted to the data, and Schoenfeld residuals were calculated to assess whether proportionality assumptions were satisfied. A variance inflation factor <5 indicates no evidence for collinearity. We first performed unadjusted Cox regression analyses, followed by multivariable models built with a hierarchical and, subsequently, additive methodological approach to limit the number of covariates to approximately 7–10 per event (25). Thus, major clinical conditions and laboratory parameters that may influence augmented formation (diabetes, smoking status, inflammation), circulating versus tissue compartmental distribution (body mass index), and kidney clearance of circulating AGEs (eGFR as a continuous variable and proteinuria) were entered into the first multivariable model (model 1) (8,26–30). Model 1 was then considered the primary multivariable model upon which additional adjustments were subsequently performed according to preceding stepwise backward linear regression analyses. In model 2, we additionally adjusted for prior cardiovascular history and significantly associated cardiovascular covariates. Finally, we additionally adjusted for significantly associated covariates in relation to lifestyle and glucose homeostasis (model 3), and kidney transplant and immunosuppressive therapy (model 4). Power calculations showed that the minimum detectable hazard ratio on the basis of an assumption of 80% power and two-sided α significance of 0.05 was 1.43 for cardiovascular mortality, and 1.29 for all-cause mortality. In order to account for noncardiovascular mortality when assessing cardiovascular mortality, we also performed cause-specific hazard models. In each of these models, the events (i.e., cardiovascular mortality and noncardiovascular mortality) are treated as censored observations (31). Potential heterogeneity on cardiovascular mortality by age, sex, body mass index, eGFR, diabetes, and HDL cholesterol were tested by fitting models containing both main effects and their cross product terms. Pinteraction<0.05 was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity. To examine whether the potential association of AGEs with cardiovascular mortality is mediated by inflammatory, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction biomarkers, we performed mediation analyses with the method described by Preacher and Hayes (32,33), which is on the basis of logistic regression. These analyses allow for testing significance and magnitude of mediation (Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Appendix 2) (32,33). Finally, because kidney transplantation aims to restore eGFR, and thus it is thought to decrease AGE levels, we aimed to additionally assess whether a potential association between eGFR and survival outcomes would be mediated by AGE levels.

In sensitivity analyses, we examined the robustness of our primary findings by means of Cox regression analyses with adjustment for time-updated eGFR, serum creatinine instead of eGFR, and eGFR according to the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine-cystatin C equation (34).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 555 kidney transplant recipients (mean age 51±12 years old; 56% men) were included at a median of 6.0 (IQR, 2.6–11.6) years after transplantation. CML and CEL concentrations were 374±110 and 224±70 ng/ml, respectively. Additional baseline characteristics and their age-, sex- and eGFR-adjusted association with circulating CML and CEL, as well as results of stepwise backward multivariable linear regression analyses, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 555 kidney transplant recipients and associations of these characteristics with circulating CML and CEL

| Baseline Characteristics | All Patients | CML, ng/ml | CEL, ng/ml | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regressiona | Backward Linear Regressionb | Linear Regressiona | Backward Linear Regressionb | ||

| Std. βf | Std. βf | Std. βf | Std. βf | ||

| CML, ng/ml, mean (SD) | 374 (110) | ― | ― | 50c | ― |

| CEL, ng/ml, mean (SD) | 224 (70) | 0.50c | ― | ― | ― |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 51 (12) | −0.02 | −0.01 | ||

| Sex, male, n (%) | 310 (56) | 0.07d | e | 0.09g | e |

| White ethnicity, n (%) | 537 (97) | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.0 (4.3) | −0.18c | ‒0.19c | ‒0.06d | −0.11c |

| Waist circumference, cm, mean (SD)h | 97 (14) | ‒0.17f | e | −0.04 | |

| Kidney allograft function | |||||

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2, mean (SD) | 47 (16) | ‒0.47c | ‒0.47c | −0.50c | ‒0.49c |

| Proteinuria ≥0.5 g/24 h, n (%)i | 152 (27) | ‒0.05 | −0.02 | ||

| Cardiovascular history | |||||

| History of cardiovascular diseasej | 73 (13) | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 153 (23) | 0.03 | −0.03 | ||

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 90 (10) | ‒0.11c | ‒0.10g | ‒0.09g | e |

| Use of antihypertensives, n (%) | 485 (87) | ‒0.06d | e | −0.02 | |

| Use of ACE inhibitor or ARB, n (%) | 187 (34) | 0.01 | 0.10c | 0.09g | |

| Use of β-blockers, n (%) | 344 (62) | ‒0.03 | −0.01 | ||

| Use of calcium antagonists, n (%) | 212 (38) | 0.02 | ‒0.03 | ||

| Lifestyle | |||||

| Current or former smoker, n (%)i | 358 (65) | ‒0.05 | ‒0.07d | e | |

| Alcohol use, n (%)k | 285 (51) | ‒0.12c | ‒0.08g | ‒0.13c | e |

| 1‒7 U/wk, n (%) | 206 (37) | ‒0.09g | e | ‒0.08g | e |

| >7 U/wk, n (%) | 79 (14) | ‒0.03 | ‒0.05d | e | |

| Physical activity, MET min/d, median (IQR)l | 234 (54‒607) | ‒0.04 | 0.004 | ||

| Diabetes and glucose homeostasis | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 96 (17) | 0.01 | 0.06d | e | |

| HbA1C, %, mean (SD)h | 6.5 (1.1) | 0.01 | 0.05d | e | |

| Insulin, µU/ml, median (IQR) | 11 (8‒16) | ‒0.06d | e | 0.06d | e |

| HOMA-IR, score, median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.6‒3.5) | ‒0.03 | 0.08g | 0.11c | |

| Laboratory measurements | |||||

| hs-CRP, mg/l, median (IQR) | 1.9 (0.8‒4.8) | ‒0.10c | ‒0.14c | ‒0.07d | −0.08g |

| Thiol, µmol/l, median (IQR)m | 107 (61‒155) | ‒0.08d | ‒0.09g | 0.01 | |

| sVCAM-1, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 967 (777‒1196) | 0.08g | 0.11c | 0.08g | 0.11c |

| Lipids | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 217 (42) | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 42 (13) | 0.01 | ‒0.01 | ||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 137 (38) | 0.03 | ‒0.03 | ||

| Triglycerides, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 169 (125‒236) | ‒0.04 | 0.09g | e | |

| Kidney transplant and immunosuppressive therapy | |||||

| Dialysis vintage, mo, median (IQR) | 27 (13‒48) | 0.06d | e | 0.08g | 0.09g |

| Time since transplantation, yr, median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.6‒11.6) | 0.05d | e | 0.12c | e |

| Donor type (living), n (%) | 78 (14) | ‒0.04 | ‒0.05d | e | |

| Use of calcineurin inhibitor, n (%) | 438 (79) | ‒0.01 | ‒0.07d | e | |

| Use of proliferation inhibitor, n (%) | 409 (74) | ‒0.07d | ‒0.09g | ‒0.12c | ‒0.10c |

| Cumulative prednisolone, grams, median (IQR) | 20 (9‒37) | 0.06d | e | 0.14c | 0.12c |

CML, Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine; CEL, Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine; Std., standardized; ―, not applicable; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; IQR, interquartile range; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; sVCAM, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Linear regression analysis; adjusted for age, sex, and eGFR.

Stepwise backward linear regression analysis; for inclusion and exclusion in this analysis, P values were set at 0.2 and 0.05, respectively.

P<0.01.

P<0.2.

Excluded from the final model.

Coefficients represent the difference (in SD) in CML or CEL per 1 SD increment in continuous characteristics or for categorical characteristics the difference (in SD) in CML or CEL compared with the implied reference group.

P<0.05.

Data available in 554 patients.

Data available in 553 patients.

Data available in 551 patients.

Data available in 550 patients.

Data available in 503 patients.

Data available in 497 patients.

Prospective Analyses

At 6.9 (IQR, 6.2–7.2) years of follow-up, 122 (22%) kidney transplant recipients died, of which 63 (52%) deaths were due to cardiovascular causes. In univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses, CML and CEL were associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Table 2). Competing risks analyses showed that AGEs were consistently associated with cardiovascular mortality, but not with the competing event noncardiovascular mortality (Supplemental Table 1). We observed no heterogeneity on cardiovascular mortality by age, sex, body mass index, eGFR, diabetes, and HDL cholesterol (Pinteraction>0.05; Supplemental Table 2). We did not find any indication that collinearity had led to artificially inflated confidence intervals in this study.

Table 2.

Association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in 555 kidney transplant recipients

| Models | CML Concentration, | CEL Concentration, | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per 1‒SD Increment | per 1‒SD Increment | |||||

| aHR | 95% CI | P Value | bHR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.50 | 1.23 to 1.82 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.13 to 1.66 | 0.001 |

| Model 1 | 1.55 | 1.24 to 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 1.18 to 1.98 | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | 1.55 | 1.23 to 1.96 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.18 to 2.04 | 0.002 |

| Model 3 | 1.53 | 1.21 to 1.93 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 1.18 to 2.00 | 0.001 |

| Model 4 | 1.56 | 1.23 to 1.97 | <0.001 | 1.46 | 1.12 to 1.91 | 0.005 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.31 | 1.12 to 1.55 | 0.001 | 1.31 | 1.13 to 1.52 | <0.001 |

| Model 1 | 1.24 | 1.02 to 1.50 | 0.03 | 1.32 | 1.08 to 1.61 | 0.006 |

| Model 2 | 1.23 | 1.01 to 1.50 | 0.04 | 1.34 | 1.09 to 1.64 | 0.006 |

| Model 3 | 1.22 | 1.01 to 1.48 | 0.04 | 1.33 | 1.09 to 1.62 | 0.005 |

| Model 4 | 1.24 | 1.02 to 1.50 | 0.03 | 1.31 | 1.07 to 1.60 | 0.01 |

Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses were performed to assess the association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular (n=63) and all-cause (n=122) mortality. Multivariable-adjusted model 1 included adjustment for age, body mass index, history of diabetes, smoking status, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, eGFR, and proteinuria. CML, Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine; CEL, Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Additional adjustment was performed for cardiovascular history and diastolic BP (model 2), alcohol use (model 3), and use of proliferation inhibitor (model 4).

Additional adjustment was performed for cardiovascular history and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme or angiotensin II receptor blocker (model 2), homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (model 3), and dialysis vintage, use of proliferation inhibitor and cumulative prednisolone dose (model 4).

Mediation Analyses

Free thiol groups and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (but not high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) were significant mediators of the association of CML and CEL with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). In additional mediation analyses we found that CML or CEL explain approximately 60% of the inverse association between eGFR and cardiovascular mortality, and approximately 35% of the inverse association between eGFR and all-cause mortality. The latter, however, likely is mainly driven by the effect on death due to cardiovascular causes, as AGEs did not mediate the association with noncardiovascular mortality (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation analysis of CML and CEL with cardiovascular mortality through hs-CRP, thiols, and sVCAM-1

| Predictor | Potential Mediator | Effect (Path)a | Coefficient (95% CI, bc)b | Proportion Mediated (95% CI, bc)bc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CML | hs-CRP | Indirect effect (ab path) | −0.01 (–0.04 to <0.001) | Not mediated |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.26) | |||

| Thiol | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.06) | 20% (9% to 61%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.17 (0.06 to 0.29) | |||

| sVCAM-1 | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.02 (0.003 to 0.08) | 17% (1% to 39%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | |||

| CEL | hs-CRP | Indirect effect (ab path) | −0.007 (–0.03 to 0.005) | Not mediated |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.23) | |||

| Thiol | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.02 (0.003 to 0.04) | 12% (6% to 36%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.16 (0.08 to 0.26) | |||

| sVCAM-1 | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.03 (0.006 to 0.07) | 21% (2% to 40%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.22) |

CML, Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine; CEL, Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; sVCAM-1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Bc, bias corrected.

The coefficients of the indirect ab path and the total ab+c’ path are standardized for the SD of the potential mediators, circulating CML and CEL concentrations and cardiovascular mortality.

95% CIs for the indirect and total effects, and proportion mediated were bias-corrected after running 2000 bootstrap samples.

The size of the significant mediated effect is calculated as the standardized indirect effect divided by the standardized total effect multiplied by 100.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis of CML and CEL with all-cause mortality through hs-CRP, thiols, and sVCAM-1

| Predictor | Potential Mediator | Effect (Path)a | Coefficient (95% CI, bc)b | Proportion Mediatedc (95% CI, bc)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CML | hs-CRP | Indirect effect (ab path) | −0.01 (–0.03 to 0.002) | Not mediated |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.21) | |||

| Thiol | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.03 (0.009 to 0.05) | 22% (3% to 89%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.22) | |||

| sVCAM-1 | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.03 (0.005 to 0.08) | 26% (4% to 74%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.11 (0.01 to 0.20) | |||

| CEL | hs-CRP | Indirect effect (ab path) | −0.006 (–0.02 to 0.006) | Not mediated |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.23) | |||

| Thiol | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.02 (0.003 to 0.04) | 9% (1% to 27%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.25) | |||

| sVCAM-1 | Indirect effect (ab path) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.07) | 21% (7% to 45%) | |

| Total effect (ab+c’ path) | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.23) |

CML, Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine; CEL, Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; sVCAM-1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Bc, bias corrected.

The coefficients of the indirect ab path and the total ab+c’ path are standardized for the SD of the potential mediators, circulating CML and CEL concentrations and all-cause mortality.

95% CIs for the indirect and total effects, and proportion mediated were bias-corrected after running 2000 bootstrap samples.

The size of the significant mediated effect is calculated as the standardized indirect effect divided by the standardized total effect multiplied by 100.

Sensitivity Analyses

Primary findings remained materially unchanged in multiple sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Tables 4–6).

Discussion

In a large cohort of stable kidney transplant recipients, this study shows that eGFR is the most important independent determinant of circulating CML and CEL concentrations, and that both these AGEs are prospectively associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality, but not with noncardiovascular mortality. Furthermore, this study provides relevant data that may support a substantial mediation effect through oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction biomarkers, which underlines the general theory of AGE pathology. Independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, we show that AGEs significantly contribute to excess premature cardiovascular mortality in stable kidney transplant recipients, and our results may support the notion that through induction of oxidative stress and expression of endothelial dysfunction biomarkers, AGE-RAGE–mediated activation of intracellular mechanisms underlie, at least to a considerable extent, the inverse association between AGEs and long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality. Finally, we show that all these findings can be further extended to a broader outcome, i.e., long-term all-cause mortality of stable kidney transplant recipients.

Because AGEs are mainly excreted by the kidneys, circulating AGE concentrations are strongly dependent of eGFR. Indeed, on the basis that kidney transplantation aims to restore eGFR, it is thought to decrease circulating AGE concentrations. Nevertheless, AGEs remain higher than normal and disproportionally high according to eGFR, which suggests that other factors, such as enhanced oxidative stress, may influence AGE formation in the particular setting of kidney transplant recipients (35). The existence of a strong relationship between the so-called advanced oxidation protein products and AGEs led to the concept of carbonyl stress, where oxidation acts in the formation of AGEs. Upon binding to RAGE, AGEs activate several signaling pathways, including NF-κB, that further amplify inflammatory and oxidative stress responses, and regulate the transcription of adhesion molecules (6). The endothelium is perhaps one of the major sources of reactive oxygen species, but is also the major target of such agents. Our data are in agreement with the hypothesis that AGE-RAGE interaction induces vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression (6,36–38), which may influence vascular remodeling in transplant vasculopathy. Furthermore, the involvement of AGE in cardiovascular disease has been linked to arterial stiffness, accelerated coronary atherosclerosis, cardiac remodeling, and ventricular dysfunction (8,39–41). Independently of eGFR, proteinuria, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, our results provide evidence that may support the concept that AGEs are nontraditional risk factors that play a substantial role in the underlying mechanisms leading to excess cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD, and extend these findings to a novel patient setting (i.e., kidney transplant recipients) by providing prospective data, and direct and specific measurement of two major circulating AGEs.

Of note, in our study, diabetes and hemoglobin A1C are not the most important driving forces behind AGE levels, which is consistent with existing evidence that the strongest association of circulating levels of AGEs is with uremia irrespective of the presence or absence of diabetes (42–44). Next, beyond eGFR, we found a particularly strong and consistent inverse association between body mass index and circulating CML and CEL concentrations. Previous studies have shown that circulating CML concentrations are decreased in obesity and inversely related to fat mass, suggesting that obesity represents a main determinant for the decline of circulating CML concentrations (35,45,46). A recent study yielded biologic plausibility, by demonstrating in humans and in an in vitro model of adipogenesis, that circulating CML is inversely associated with central obesity and inflammation, in agreement with our findings (47). Like central obesity, kidney transplantation is characterized by greater levels of long-term, ongoing, low-grade inflammation that, through a RAGE-mediated trapping of CML in adipose tissue, inversely relates to circulating concentrations of CML. The aforementioned and further complex interactions between C-reactive protein and cardiovascular disease may also help us to understand the lack of significant mediation through high-sensitivity C-reactive protein reported here (48).

Agents that aim to inhibit the formation of AGEs offer an intriguing opportunity to counteract their pathologic effects. Indeed, several pharmacologic treatment strategies targeting the AGE-RAGE system, i.e., antioxidants, reactive carbonyl scavengers, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, and aldose reductase inhibitors (reviewed in Stinghen et al. [8]), as well as AGE breakers (reviewed in Susic et al. [49]), have been studied in vitro and in vivo, and associated with improved cardiovascular end points. To date, however, there is a critical lack of clinical trials using anti-AGE therapies in kidney transplant recipients. Our results warrant further studies to investigate whether AGE-targeted strategies may offer interventional pathways to reduce the excess of cardiovascular disease after kidney transplantation and decrease the burden or premature cardiovascular mortality in successful kidney transplant recipients.

Remarkably, to our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate the association of AGEs with cardiovascular and/or overall survival end points in stable kidney transplant recipients, while previous studies have been limited to link AGEs with cardiovascular risk factors. Furthermore, our analyses relied on data from direct and specific measurements of two major circulating AGEs. Of note, previous evidence has also been limited to the use of skin autofluorescence readings (10–13). It is critical to take into account that the current understanding of AGEs indicates that most AGEs are not fluorescent. Fluorescence wavelength used to measure AGEs is not specific, as fluorescence represents group reactivity and so does not provide quantitative information on concentrations of individual compounds. In addition to AGEs, other substances such as lipofuscin and ceroid can be detected using the same excitation and emission wavelengths (50). Thereby, we cannot completely exclude the influence of other uremic toxins or skin fluorophores on skin auto fluorescence measurements.

We performed a prospective cohort study in a large sample size of stable kidney transplant recipients, who were closely monitored during a considerable follow-up period by regular check-up in the outpatient clinic, granting complete end point evaluation without loss to follow-up. Furthermore, data were extensively collected, which allowed for adjustment of several potential confounders, among which were kidney transplant–specific and traditional cardiovascular risk factors. On the other hand, limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, creatinine was measured according to the Jaffé method, which is not traceable by isotope dilution mass spectrometry and therefore not standardized. Its use usually results in an overestimation of serum creatinine, and therefore an underestimation of the GFR. Of note, however, multiple sensitivity analyses with adjustment for time-updated eGFR, serum creatinine instead of eGFR, and eGFR calculated with incorporation of cystatin C according to the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine-cystatin C equation, support the robustness of our findings. Second, because of the relatively wide range of transplant vintage at the time of recruitment, healthy survivor bias could be present. Third, because of its observational design, our study does not allow hard conclusions on causality, and reversed causation or residual confounding, including in mediation analyses, may occur. Fourth, we were limited by the number of events to specifically investigate the association of AGEs with different specific cardiovascular causes of death. Finally, cardiovascular complications or interventions were not documented; therefore, we were unable to assess the association of AGE with nonfatal cardiovascular events, and analyses on such data could have added power to further support that AGEs act through cardiovascular disease to lead to a higher mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Nevertheless, our results show, for the first time, a prospective association of circulating concentrations of the AGEs CML and CEL with the hard end point long-term cardiovascular mortality in stable kidney transplant recipients, which is currently the leading individual cause of long-term mortality in this population, thus emphasizing the need for future studies in which such analyses are performed. Of note, to the best of our knowledge, current reference values for CML and CEL have not been established. Given our findings, standardized assays for CML and CEL, with reference values, are warranted. Finally, the population of this study consisted predominantly of white patients, which calls for prudence when extrapolating these results to different populations.

In conclusion, eGFR is the most important independent determinant of circulating CML and CEL, and both these major AGEs are independently associated with long-term risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. In the successful post-kidney transplant setting, circulating AGEs significantly contribute to premature cardiovascular mortality in stable kidney transplant recipients, independently of eGFR, proteinuria, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This study provides relevant data that may support the notion that, through induction of oxidative stress and expression of endothelial dysfunction biomarkers, AGE-RAGE–mediated activation of intracellular mechanisms underlie, to a considerable extent, the association of AGEs with long-term risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in successful kidney transplant recipients. Further studies are warranted to evaluate whether assessment of these AGEs may be helpful to monitor stable kidney transplant recipients, assess prognosis, and tailor existing treatment.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study is based on data of the TransplantLines Insulin Resistance and Inflammation (TxL-IRI) cohort (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03272854), which was funded by the Dutch Kidney Foundation (grant C00.1877). Dr. Sotomayor is supported by a doctorate studies grant from Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (F 72190118).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00540119/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) and Nε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL) measurement.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Mediation analysis.

Supplemental Table 1. Competing risk analyses of the association of AGEs with cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in 555 kidney transplant recipients.

Supplemental Table 2. Heterogeneity analyses on the association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular mortality.

Supplemental Table 3. Mediation analysis of eGFR with cardiovascular, all-cause mortality, and noncardiovascular mortality through CML and CEL.

Supplemental Table 4. Sensitivity analyses: association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in 555 kidney transplant recipients, with time-updated eGFR.

Supplemental Table 5. Sensitivity analyses: association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in 555 kidney transplant recipients, with adjustment for serum creatinine instead of eGFR.

Supplemental Table 6. Sensitivity analyses: association of circulating CML and CEL with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in 555 kidney transplant recipients, with adjustment for eGFR calculated according to the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine-cystatin equation.

Supplemental Figure 1. Mediation analysis on the association of advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) with cardiovascular mortality.

References

- 1.Jardine AG, Gaston RS, Fellstrom BC, Holdaas H: Prevention of cardiovascular disease in adult recipients of kidney transplants. Lancet 378: 1419–1427, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasiske BL, Vazquez MA, Harmon WE, Brown RS, Danovitch GM, Gaston RS, Roth D, Scandling JD, Singer GG: Recommendations for the outpatient surveillance of renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 11[Suppl 15]: S1–S86, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver SA, Huang M, Nash MM, Prasad GV: Framingham risk score and novel cardiovascular risk factors underpredict major adverse cardiac events in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 92: 183–189, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maillard LC: Action of amino acids on sugars. Formation of melanoidins in a methodical way. Compt Rend 154: 66–68, 1912 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HB, Yu MR, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Ha H: Reactive oxygen species-regulated signaling pathways in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[Suppl 3]: S241–S245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan SD, Schmidt AM, Anderson GM, Zhang J, Brett J, Zou YS, Pinsky D, Stern D: Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins. J Biol Chem 269: 9889–9897, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linden E, Cai W, He JC, Xue C, Li Z, Winston J, Vlassara H, Uribarri J: Endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease results from advanced glycation end products (AGE)-mediated inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase through RAGE activation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 691–698, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stinghen AE, Massy ZA, Vlassara H, Striker GE, Boullier A: Uremic toxicity of advanced glycation end products in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 354–370, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stam F, van Guldener C, Becker A, Dekker JM, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CD: Endothelial dysfunction contributes to renal function-associated cardiovascular mortality in a population with mild renal insufficiency: The Hoorn study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 537–545, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meerwaldt R, Hartog JW, Graaff R, Huisman RJ, Links TP, den Hollander NC, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, Navis G, Gans RO, Smit AJ: Skin autofluorescence, a measure of cumulative metabolic stress and advanced glycation end products, predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3687–3693, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner Z, Molnár M, Molnár GA, Tamaskó M, Laczy B, Wagner L, Csiky B, Heidland A, Nagy J, Wittmann I: Serum carboxymethyllysine predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 294–300, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartog JW, de Vries AP, Bakker SJ, Graaff R, van Son WJ, van der Heide JJ, Gans RO, Wolffenbuttel BH, de Jong PE, Smit AJ: Risk factors for chronic transplant dysfunction and cardiovascular disease are related to accumulation of advanced glycation end-products in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2263–2269, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calviño J, Cigarran S, Gonzalez-Tabares L, Menendez N, Latorre J, Cillero S, Millan B, Cobelo C, Sanjurjo-Amado A, Quispe J, Garcia-Enriquez A, Carrero JJ: Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) estimated by skin autofluorescence are related with cardiovascular risk in renal transplant. PLoS One 13: e0201118, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu MX, Requena JR, Jenkins AJ, Lyons TJ, Baynes JW, Thorpe SR: The advanced glycation end product, Nepsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine, is a product of both lipid peroxidation and glycoxidation reactions. J Biol Chem 271: 9982–9986, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glomb MA, Monnier VM: Mechanism of protein modification by glyoxal and glycolaldehyde, reactive intermediates of the Maillard reaction. J Biol Chem 270: 10017–10026, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulanger E, Wautier MP, Wautier JL, Boval B, Panis Y, Wernert N, Danze PM, Dequiedt P: AGEs bind to mesothelial cells via RAGE and stimulate VCAM-1 expression. Kidney Int 61: 148–156, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glorieux G, Helling R, Henle T, Brunet P, Deppisch R, Lameire N, Vanholder R: In vitro evidence for immune activating effect of specific AGE structures retained in uremia. Kidney Int 66: 1873–1880, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oterdoom LH, van Ree RM, de Vries APJ, Gansevoort RT, Schouten JP, van Son WJ, Homan van der Heide JJ, Navis G, de Jong PE, Gans RO, Bakker SJ: Urinary creatinine excretion reflecting muscle mass is a predictor of mortality and graft loss in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 86: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Annema W, Dikkers A, de Boer JF, Dullaart RP, Sanders JS, Bakker SJ, Tietge UJ: HDL cholesterol efflux predicts graft failure in renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 595–603, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keyzer CA, de Borst MH, van den Berg E, Jahnen-Dechent W, Arampatzis S, Farese S, Bergmann IP, Floege J, Navis G, Bakker SJ, van Goor H, Eisenberger U, Pasch A: Calcification propensity and survival among renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 239–248, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rexrode KM, Willett WC, Manson JE: Physical activity and risk of stroke in women. JAMA 283: 2961–2967, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Berg E, Pasch A, Westendorp WH, Navis G, Brink EJ, Gans RO, van Goor H, Bakker SJ: Urinary sulfur metabolites associate with a favorable cardiovascular risk profile and survival benefit in renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1303–1312, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panteghini M; IFCC Scientific Division : Enzymatic assays for creatinine: Time for action. Clin Chem Lab Med 46: 567–572, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE: Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol 165: 710–718, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkelmayer WC, Lorenz M, Kramar R, Födinger M, Hörl WH, Sunder-Plassmann G: C-reactive protein and body mass index independently predict mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 4: 1148–1154, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abedini S, Holme I, März W, Weihrauch G, Fellström B, Jardine A, Cole E, Maes B, Neumayer HH, Grønhagen-Riska C, Ambühl P, Holdaas H; ALERT study group : Inflammation in renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1246–1254, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semba RD, Nicklett EJ, Ferrucci L: Does accumulation of advanced glycation end products contribute to the aging phenotype? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 963–975, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallipattu SK, He JC, Uribarri J: Role of advanced glycation endproducts and potential therapeutic interventions in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 25: 529–538, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaens KHJ, Ferreira I, van de Waarenburg MPH, van Greevenbroek MM, van der Kallen CJH, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Rensen SS, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG: Protein-Bound plasma Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine is inversely associated with central obesity and inflammation and significantly explain a part of the central obesity-related increase in inflammation: The Hoorn and CODAM studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 2707–2713, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ: When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2670–2677, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF: SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 36: 717–731, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes A: Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76: 408–420, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS; CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebeková K, Podracká L, Blazícek P, Syrová D, Heidland A, Schinzel R: Plasma levels of advanced glycation end products in children with renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 16: 1105–1112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt AM, Hori O, Brett J, Yan SD, Wautier JL, Stern D: Cellular receptors for advanced glycation end products. Implications for induction of oxidant stress and cellular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of vascular lesions. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 1521–1528, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt AM, Hori O, Chen JX, Li JF, Crandall J, Zhang J, Cao R, Yan SD, Brett J, Stern D: Advanced glycation endproducts interacting with their endothelial receptor induce expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in cultured human endothelial cells and in mice. A potential mechanism for the accelerated vasculopathy of diabetes. J Clin Invest 96: 1395–1403, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ardehali A, Laks H, Drinkwater DC, Ziv E, Drake TA: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is induced on vascular endothelia and medial smooth muscle cells in experimental cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Circulation 92: 450–456, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Zalewski A, Liu Y, Mazurek T, Cowan S, Martin JL, Hofmann SM, Vlassara H, Shi Y: Diabetes-induced oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation in porcine coronary arteries. Circulation 108: 472–478, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakata N, Imanaga Y, Meng J, Tachikawa Y, Takebayashi S, Nagai R, Horiuchi S: Increased advanced glycation end products in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with end-stage renal disease. Atherosclerosis 142: 67–77, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Liu K, Wang Z, Liu C, Han Z, Tao J, Lu P, Wang J, Wu B, Huang Z, Yin C, Gu M, Tan R: Advanced glycation end products accelerate arteriosclerosis after renal transplantation through the AGE/RAGE/ILK pathway. Exp Mol Pathol 99: 312–319, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odetti P, Fogarty J, Sell DR, Monnier VM: Chromatographic quantitation of plasma and erythrocyte pentosidine in diabetic and uremic subjects. Diabetes 41: 153–159, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monnier VM, Sell DR, Nagaraj RH, Miyata S, Grandhee S, Odetti P, Ibrahim SA: Maillard reaction-mediated molecular damage to extracellular matrix and other tissue proteins in diabetes, aging, and uremia. Diabetes 41[Suppl 2]: 36–41, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyata T, Ueda Y, Shinzato T, Iida Y, Tanaka S, Kurokawa K, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Maeda K: Accumulation of albumin-linked and free-form pentosidine in the circulation of uremic patients with end-stage renal failure: Renal implications in the pathophysiology of pentosidine. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1198–1206, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sebeková K, Krivošíková Z, Gajdoš M: Total plasma Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine and sRAGE levels are inversely associated with a number of metabolic syndrome risk factors in non-diabetic young-to-middle-aged medication-free subjects. Clin Chem Lab Med 52: 139–149, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semba RD, Arab L, Sun K, Nicklett EJ, Ferrucci L: Fat mass is inversely associated with serum carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, in adults. J Nutr 141: 1726–1730, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaens KHJ, Goossens GH, Niessen PM, van Greevenbroek MM, van der Kallen CJH, Niessen HW, Rensen SS, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Blaak EE, van Zandvoort MA, Bierhaus A, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG: Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine-receptor for advanced glycation end product axis is a key modulator of obesity-induced dysregulation of adipokine expression and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 1199–1208, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poon PY, Szeto CC, Kwan BC, Chow KM, Li PK: Relationship between CRP polymorphism and cardiovascular events in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 304–309, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Susic D, Varagic J, Ahn J, Frohlich ED: Crosslink breakers: A new approach to cardiovascular therapy. Curr Opin Cardiol 19: 336–340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin D: Biochemical basis of lipofuscin, ceroid, and age pigment-like fluorophores. Free Radic Biol Med 21: 871–888, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.