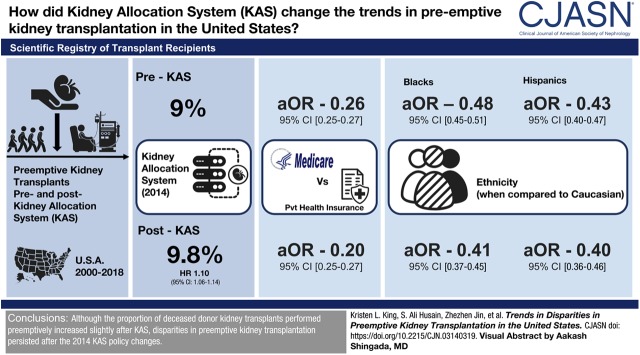

Visual Abstract

Keywords: preemptive kidney transplantation; deceased donor; allocation system; unintended consequences; health policy; adult; humans; female; United States; kidney transplantation; transplant recipients; logistic models; renal dialysis; chronic kidney failure; kidney failure, chronic; tissue donors; HLA antigens; European Continental Ancestry Group; Hispanic Americans; Registries; Medicare; diabetes mellitus; Insurance Coverage; hypertension

Abstract

Background and objectives

Long wait times for deceased donor kidneys and low rates of preemptive wait-listing have limited preemptive transplantation in the United States. We aimed to assess trends in preemptive deceased donor transplantation with the introduction of the new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) in 2014 and identify whether key disparities in preemptive transplantation have changed.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We identified adult deceased donor kidney transplant recipients in the United States from 2000 to 2018 using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Preemptive transplantation was defined as no dialysis before transplant. Associations between recipient, donor, transplant, and policy era characteristics and preemptive transplantation were calculated using logistic regression. To test for modification by KAS policy era, an interaction term between policy era and each characteristic of interest was introduced in bivariate and adjusted models.

Results

The proportion of preemptive transplants increased after implementation of KAS from 9.0% to 9.8%, with 1.10 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.06 to 1.14) times higher odds of preemptive transplantation post-KAS compared with pre-KAS. Preemptive recipients were more likely to be white, older, female, more educated, hold private insurance, and have ESKD cause other than diabetes or hypertension. Policy era significantly modified the association between preemptive transplantation and race, age, insurance status, and Human Leukocyte Antigen zero-mismatch (interaction P<0.05). Medicare patients had a significantly lower odds of preemptive transplantation relative to private insurance holders (pre-KAS adjusted OR, [aOR] 0.26; [95% CI, 0.25 to 0.27], to 0.20 [95% CI, 0.18 to 0.22] post-KAS). Black and Hispanic patients experienced a similar phenomenon (aOR 0.48 [95% CI, 0.45 to 0.51] to 0.41 [95% CI, 0.37 to 0.45] and 0.43 [95% CI, 0.40 to 0.47] to 0.40 [95% CI, 0.36 to 0.46] respectively) compared with white patients.

Conclusions

Although the proportion of deceased donor kidney transplants performed preemptively increased slightly after KAS, disparities in preemptive kidney transplantation persisted after the 2014 KAS policy changes and were exacerbated for racial minorities and Medicare patients.

Introduction

The incidence of ESKD in the United States is steadily rising (1). Although kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for kidney failure, only a minority of eligible patients are currently waitlisted for a transplant. Despite the benefits of preemptive transplantation, including improved outcomes (2–9), fewer complications (6–10), and system-wide economic benefits (8,9), most patients are waitlisted after initiating dialysis. Recently preemptive transplantation accounted for 9%–11% of all deceased donor kidney transplants (5,11), but only 2.5% of patients with incident kidney failure in 2015 received a preemptive transplant as their first form of kidney replacement therapy (1).

Significant racial disparities have been described in kidney transplantation, including preemptive wait-listing, duration of pretransplant dialysis, rates of kidney transplantation, and post-transplant outcomes (12–14). Sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, primary insurance coverage, and education, are also associated with disparities in preemptive wait-listing and transplantation (11,15), likely reflecting known disparities in early access to nephrology care.

The new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) was designed in part to address racial and other disparities in transplantation (16). Recent analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in racial disparities in overall access to deceased donor transplantation (17), largely by providing credit for total ESKD time. This change has the potential unintended consequence of decreasing the sense of urgency for timely referral of patients for wait-listing, especially in regions with long wait times. This change also has the potential for broadly decreasing preemptive deceased donor transplantation by prolonging the average allocation time to transplantation.

The Healthy People 2020 program established national health promotion priorities and objectives. One of several goals for improving outcomes for patients with kidney disease included increasing the proportion of patients with ESKD receiving a preemptive transplant from the baseline of 4% in 2007 (18). Although there appears to be substantial progress made toward certain goals related to kidney disease, the proportion of preemptive transplants being performed after the 2014 introduction of KAS has not been studied previously (19). Given the Healthy People 2020 goal of increasing preemptive transplantation and potential changes in transplantation rates under the new KAS, we aimed to describe who received a deceased donor kidney transplant preemptively and identify whether key disparities in preemptive transplant recipients have changed.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

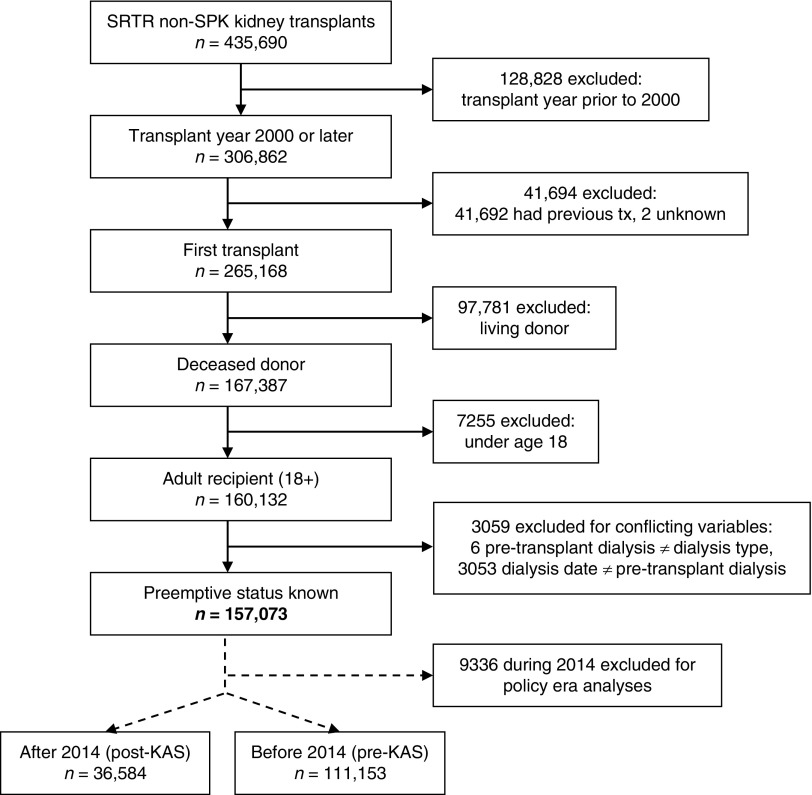

This study used national data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients standard analysis file. We identified all kidney transplants that occurred in the United States between January 1, 2000 and May 31, 2018. All first-time, deceased donor, kidney transplant recipients aged ≥18 years old with no conflicting pretransplant dialysis variables (dialysis date, pretransplant dialysis, dialysis type) and no simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant were included, yielding a cohort of 157,073 patients (Figure 1). The primary outcome of interest was preemptive transplantation, with preemptive recipients defined as those with no dialysis before transplant (n=14,620), and nonpreemptive recipients as those receiving any modality of dialysis before transplant (n=142,453). For analyses comparing associations pre- and post-KAS, transplants occurring during 2014 were excluded to account for a transition period as the new policy was anticipated/implemented. For subgroup analyses by policy era, 111,153 patients received a transplant before 2014 (“pre-KAS”) and 36,584 after 2014 (“post-KAS”).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selecting the study population. SPK, simultaneous pancreas-kidney; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; tx, transplant.

Statistical Analyses

Recipient sociodemographic characteristics, transplant characteristics, donor characteristics, and transplant complications were selected a priori on the basis of previous literature (4,5,11,20) and clinical significance. Recipient sociodemographic characteristics of interest included race/ethnicity, age at transplant, sex, education, and primary insurance payer. Clinical/transplant characteristics analyzed were ESKD cause (GN, diabetes, hypertension, polycystic kidney disease, other/unknown), HLA zero-mismatch, panel-reactive antibody (PRA) sensitization, cold ischemic time, and recipient’s ABO blood type, history of diabetes, history of drug-treated hypertension, and estimated post-transplant survival (EPTS) score at transplant. Donor characteristics of interest were age and Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) score. Transplant complications considered were acute rejection episodes and delayed graft function, defined as requiring dialysis in the first week post-transplant. EPTS and KDPI scores were calculated using the 2015 reference population mapping tables. Missing values for categorical variables were combined into another category if <1% of the sample or made into an “unknown” category if >1%. Cold ischemic time was the only continuous variable with missing values (5.1%). Data analysis was carried out for the full cohort, as well as for subgroups receiving transplants before 2014 (pre-KAS) and after 2014 (post-KAS).

Characteristics were compared between preemptive and nonpreemptive transplant recipients and presented as proportions for categorical variables or the mean±SD for continuous variables. Chi-squared and two-sided t tests were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Associations between recipient/transplant characteristics and preemptive transplantation were examined using bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models. The multivariable logistic regression model was built on the basis of recipient and transplant characteristics that were clinically and statistically significant in the bivariable logistic regression analyses. Transplant year was included to control for trends in preemptive transplantation not accounted for by other covariates. Prespecified interaction terms between characteristics and policy era of the transplant (pre-KAS or post-KAS) were also examined with logistic regression to test for modification by policy era in both the unadjusted and fully adjusted models.

A two-sided α of 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance. All analyses were completed using Stata v15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the “Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.”

Sensitivity Analyses

To evaluate whether the associations between key disparity characteristics and preemptive transplantation were consistent throughout the 3.5 years post-KAS, bivariable associations with preemptive transplantation were calculated via logistic regression for race/ethnicity and insurance, stratified by post-KAS transplant year. To test if there was a change in associations over time since the KAS policy change, additional logistic regression models were fitted with interaction terms between the categorical race/insurance variables and continuous post-KAS transplant date. We performed additional analyses excluding 2015 from the post-KAS cohort compared with a pre-KAS cohort of similar size and time period (2011–2013) to assess whether a bolus effect in 2015 or potential secular changes over the extensive pre-KAS time period biased our findings. We also looked for spillover effects of the KAS policy change on preemptive living donor transplantation by reproducing our main analyses in a similar cohort of recipients of living donor kidney transplants between 2000 and 2018 (n=91,105).

In the absence of zip code level data to determine county income or population characteristics, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis utilizing working status (working for income versus not working because of disability or not working for another reason) and any Medicaid history (defined as documented Medicaid coverage as primary or secondary insurer at the time of listing or at transplantation) as surrogates for socioeconomic status in adjusted and unadjusted models. However, because of changes in data collection over time, working status information was missing for the majority of patients in the pre-KAS era, and secondary insurance coverage was missing for the majority of patients in the post-KAS era.

Results

Characteristics of Preemptive Transplant Recipients, 2000–2018

Among 157,073 deceased donor kidney transplants occurring between 2000 and 2018, 14,620 (9.31%) were preemptive. Preemptive deceased donor transplant recipients were more likely to be white (versus black or Hispanic), older, female, more educated, have private insurance (versus Medicare or Medicaid), and have ESKD cause other than diabetes or hypertension (Table 1). Those with blood type O were less likely to receive a preemptive transplant compared with types A and AB (odds ratios [ORs], 1.44 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.39 to 1.50] and 1.83 [95% CI, 1.71 to 1.96], respectively), but equally likely to receive a preemptive transplant compared with type B (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.11). Among preemptive recipients, 34% had EPTS ≤20% at the time of transplant (compared with 26% of nonpreemptive recipients), and individuals with EPTS ≤20% were more likely to receive their transplant preemptively (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.42 to 1.53).

Table 1.

Characteristics of preemptive versus nonpreemptive deceased donor kidney transplants, 2000–2018

| Characteristic | Total Transplants (n=157,073) | Preemptive (n=14,620) | Nonpreemptive (n=142,453) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 67,424 | 10,075 (15%) | 57,349 (85%) | Reference group |

| Black | 51,709 | 2495 (5%) | 49,214 (95%) | 0.29 (0.28, 0.30) |

| Hispanic | 24,664 | 1204 (5%) | 23,460 (95%) | 0.29 (0.27, 0.31) |

| Other | 13,276 | 846 (6%) | 12,430 (94%) | 0.39 (0.36, 0.42) |

| Age at transplant | ||||

| Yearsa | 157,073 | 55 (±12) | 53 (±13) | 1.20 (1.18, 1.22) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 95,173 | 7820 (8%) | 87,353 (92%) | Reference group |

| Female | 61,900 | 6800 (11%) | 55,100 (89%) | 1.38 (1.33, 1.43) |

| Education level | ||||

| High school or less | 76,336 | 5522 (7%) | 70,814 (93%) | Reference group |

| Post-high school | 63,951 | 7282 (11%) | 56,669 (89%) | 1.65 (1.59, 1.71) |

| Unknown | 16,786 | 1816 (11%) | 14,970 (89%) | 1.56 (1.47, 1.65) |

| Primary payer | ||||

| Private | 41,440 | 8195 (20%) | 33,245 (80%) | Reference group |

| Medicare | 103,350 | 5032 (5%) | 98,318 (95%) | 0.21 (0.20, 0.22) |

| Medicaid | 8278 | 803 (10%) | 7475 (90%) | 0.44 (0.40, 0.47) |

| Other/unknown | 4005 | 590 (15%) | 3415 (85%) | 0.70 (0.64, 0.77) |

| ESKD cause | ||||

| GN | 8053 | 721 (9%) | 7332 (91%) | Reference group |

| Diabetes | 44,203 | 2767 (6%) | 41,436 (94%) | 0.68 (0.62, 0.74) |

| Hypertension | 40,195 | 2407 (6%) | 37,788 (94%) | 0.65 (0.59, 0.71) |

| PCKD | 13,509 | 2264 (17%) | 11,245 (83%) | 2.05 (1.87, 2.24) |

| Other/unknown | 51,113 | 6461 (13%) | 44,652 (87%) | 1.47 (1.36, 1.60) |

| EPTS score at transplant | ||||

| >20% or unknown | 115,477 | 9672 (8%) | 105,805 (92%) | Reference group |

| ≤20% (top 20) | 41,596 | 4948 (12%) | 36,648 (88%) | 1.48 (1.42, 1.53) |

| KDPI score | ||||

| ≤85%/unknown | 140,334 | 13,371 (10%) | 126,963 (90%) | Reference group |

| >85% (high KDPI) | 16,739 | 1249 (7%) | 15,490 (93%) | 0.77 (0.72, 0.81) |

| HLA mismatch | ||||

| Nonzero MM/unknown | 143,166 | 12,498 (9%) | 130,668 (91%) | Reference group |

| Zero HLA mismatch | 13,907 | 2122 (15%) | 11,785 (85%) | 1.88 (1.79, 1.98) |

| PRA sensitization | ||||

| PRA <80% | 110,395 | 9784 (9%) | 100,611 (91%) | Reference group |

| PRA 80%–97% | 6931 | 590 (9%) | 6341 (91%) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) |

| PRA 98%–100% | 3112 | 222 (7%) | 2890 (93%) | 0.79 (0.69, 0.91) |

| Unknown | 36,635 | 4024 (11%) | 32,611 (89%) | 1.27 (1.22, 1.32) |

| ABO blood type | ||||

| O | 70,792 | 5554 (8%) | 65,238 (92%) | Reference group |

| A | 56,698 | 6200 (11%) | 50,498 (89%) | 1.44 (1.39, 1.50) |

| B | 21,170 | 1734 (8%) | 19,436 (92%) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) |

| AB | 8413 | 1132 (13%) | 7281 (87%) | 1.83 (1.71, 1.96) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No or unknown | 100,952 | 10,437 (10%) | 90,515 (90%) | Reference group |

| Yes | 56,121 | 4183 (7%) | 51,938 (93%) | 0.70 (0.67, 0.73) |

| Drug-treated hypertension | ||||

| No | 17,536 | 1946 (11%) | 15,590 (89%) | Reference group |

| Yes | 107,841 | 8658 (8%) | 99,183 (92%) | 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) |

| Unknown | 31,696 | 4016 (13%) | 27,680 (87%) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) |

| Donor age | ||||

| Yearsa | 157,073 | 37 (±16) | 39 (±17) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) |

| Acute rejection episodes | ||||

| No | 123,874 | 12,020 (10%) | 111,854 (90%) | Reference group |

| Yes | 2878 | 177 (6%) | 2701 (94%) | 0.61 (0.52, 0.71) |

| Unknown | 30,321 | 2423 (8%) | 27,898 (92%) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.85) |

| Delayed graft function | ||||

| No/unknown | 116,648 | 13,685 (12%) | 102,963 (88%) | Reference group |

| Yes | 40,425 | 935 (2%) | 39,490 (98%) | 0.18 (0.17, 0.19) |

| Cold ischemic time | ||||

| Hoursb | 157,073 | 17 (±9) | 18 (±9) | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99) |

| Policy era | ||||

| Before 2014 (pre-KAS) | 111,153 | 10,045 (9%) | 101,108 (91%) | Reference group |

| After 2014 (post-KAS) | 36,584 | 3603 (10%) | 32,981 (90%) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) |

| During 2014 | 9336 | 972 (10%) | 8364 (90%) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) |

Values presented are n (row %) or mean (±SD). Odds ratios are for unadjusted odds of preemptive transplant. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease; EPTS, estimated post-transplant survival; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index; HLA, Human Leukocyte Antigen; MM, mismatch; PRA, panel reactive antibody; KAS, Kidney Allocation System.

Odds ratio is for a 10-year increase in age.

Odds ratio is for a 1-hour increase in time.

Patients with hypertension or diabetes had a lower likelihood of receiving a preemptive transplant compared with those without (ORs, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.66 to 0.74] and 0.70 [95% CI, 0.67 to 0.73], respectively). The highest sensitized individuals (PRA 98%–100%) were also less likely to receive preemptive transplants (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.91) compared with those with PRA <80%. Kidneys with KDPI >85% were less likely to be used for a preemptive patient (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.81), whereas those that resulted in HLA zero-mismatch transplants were more likely to be used preemptively (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.79 to 1.98). Preemptive recipients also experienced less delayed graft function (OR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.19) and acute rejection (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.71).

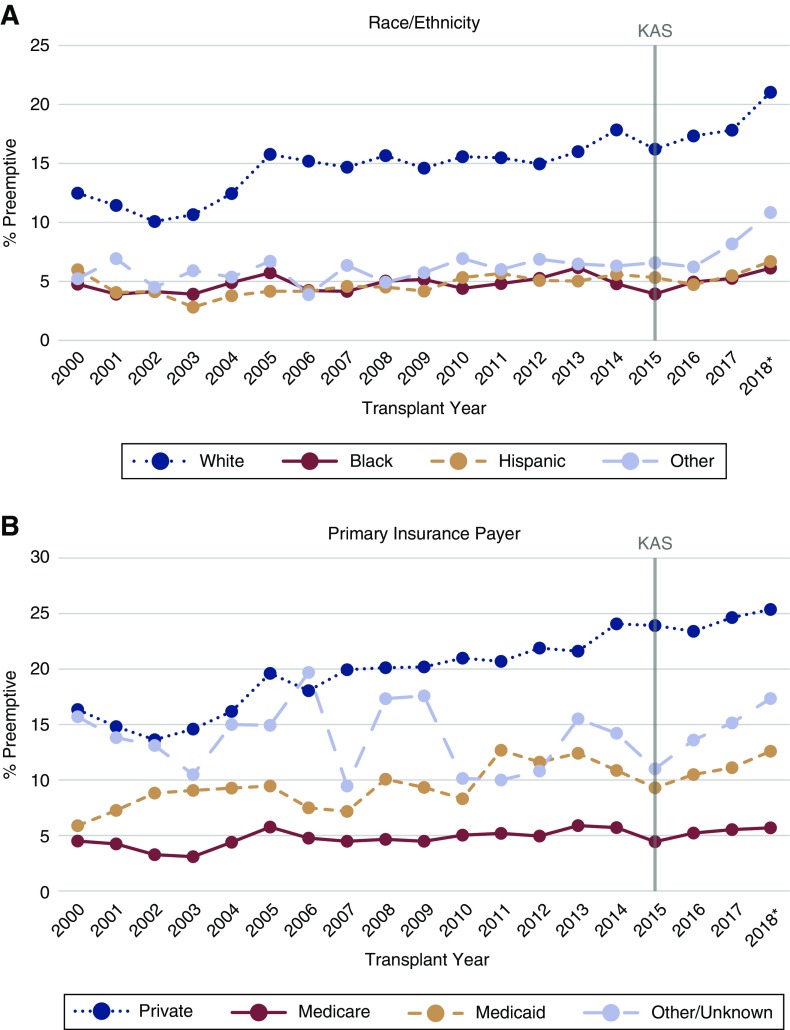

The proportion of deceased donor transplants occurring preemptively during each year of the study period is presented in Figure 2, stratified by race/ethnicity (Figure 2A) and primary insurance payer (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Proportions of deceased donor kidney transplants occurring preemptively over time, by race/ethnicity and primary insurance payer. *2018 data only available through May 31, 2018. KAS, Kidney Allocation System.

Comparing Unadjusted Characteristics before and after KAS

The proportion of preemptive kidney transplants increased slightly after 2014, from 9.0% of all deceased donor transplants to 9.8% (Table 2). This overall difference was largely influenced by a marked increase in the proportion of preemptive transplants among white recipients, although no race or insurance subgroup displayed a lower proportion of preemptive transplants after KAS (Figure 2). Overall, transplants had 1.10 (95% CI, 1.06 to 1.14) times higher odds of occurring preemptively in the post-KAS era compared with the pre-KAS era (Table 1). The unadjusted relationships between likelihood of preemptive deceased donor transplantation and recipient race (black versus white), age, insurance status (Medicare/Medicaid versus private), and HLA mismatch varied significantly (interaction term P<0.05) by policy era (Supplemental Table 1). The unadjusted OR of receiving a transplant preemptively for black patients compared with white patients was lower post-KAS (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.26) compared with pre-KAS (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.33). The OR of preemptive transplantation for patients with Medicare compared with those with private insurance was also lower post-KAS (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.18) than pre-KAS (OR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.23). Recipients with Medicaid became even less likely to receive their transplant preemptively compared with those with private insurance (pre-KAS OR of 0.45 [95% CI, 0.41 to 0.49] to post-KAS OR of 0.37 [95% CI, 0.32 to 0.43]). Although there was a lower unadjusted OR of preemptive transplantation for Hispanic patients compared with white patients, from 0.30 (95% CI, 0.27 to 0.32) pre-KAS to 0.26 (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.30) post-KAS, this change was not statistically significant (interaction term P=0.12).

Table 2.

Characteristics of preemptive deceased donor kidney transplants, pre-KAS (2000–2013) and post-KAS (2015–2018)

| Characteristic | Total Transplants | Preemptive Transplants n (% Preemptive) |

Absolute Difference in % Preemptive or Age (post-KAS - pre-KAS) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) of Preemptive Transplantation | Interaction Term P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-KAS | Post-KAS | Pre-KAS | Post-KAS | Pre-KAS | Post-KAS | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 50,487 | 13,120 | 7072 (14%) | 2322 (18%) | 3.69 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Black | 35,870 | 12,817 | 1721 (5%) | 629 (5%) | 0.11 | 0.48 (0.45, 0.51) | 0.41 (0.37, 0.45) | <0.001a |

| Hispanic | 15,998 | 7073 | 734 (5%) | 381 (5%) | 0.80 | 0.43 (0.40, 0.47) | 0.40 (0.36, 0.46) | 0.04a |

| Other | 8798 | 3574 | 518 (6%) | 271 (8%) | 1.69 | 0.43 (0.39, 0.47) | 0.44 (0.38, 0.51) | 0.99 |

| Age at transplant | ||||||||

| Yearsb | 111,153 | 36,584 | 55 (±12)c | 57 (±12)c | 1.93 | 1.69 (1.64, 1.74) | 2.09 (1.99, 2.20) | <0.001a |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 67,491 | 21,961 | 5392 (8%) | 1880 (9%) | 0.57 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Female | 43,662 | 14,623 | 4653 (11%) | 1723 (12%) | 1.12 | 1.41 (1.35, 1.48) | 1.37 (1.27, 1.48) | 0.52 |

| Education level | ||||||||

| High school or less | 3789 | 18,270 | 3789 (7%) | 1354 (7%) | 0.31 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Post-high school education | 4662 | 17,230 | 4662 (11%) | 2059 (12%) | 0.93 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.25) | 0.57 |

| Unknown | 1594 | 1084 | 1594 (10%) | 190 (18%) | 7.23 | 1.42 (1.33, 1.51) | 1.73 (1.44, 2.09) | 0.01a |

| Primary payer | ||||||||

| Private | 31,946 | 7317 | 5903 (18%) | 1768 (24%) | 5.68 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Medicare | 71,803 | 25,020 | 3370 (5%) | 1289 (5%) | 0.46 | 0.26 (0.25, 0.27) | 0.20 (0.18, 0.22) | <0.001a |

| Medicaid | 5410 | 2426 | 498 (9%) | 257 (11%) | 1.38 | 0.71 (0.64, 0.78) | 0.67 (0.57, 0.78) | 0.12 |

| Other/unknown | 1994 | 1821 | 274 (14%) | 289 (16%) | 2.13 | 0.81 (0.71, 0.93) | 0.62 (0.53, 0.73) | 0.02a |

| ESKD cause | ||||||||

| GN | 6432 | 1251 | 573 (9%) | 112 (9%) | 0.04 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Diabetes | 30,386 | 10,922 | 1890 (6%) | 691 (6%) | 0.11 | 0.62 (0.55, 0.71) | 0.52 (0.40, 0.67) | 0.96 |

| Hypertension | 28,419 | 9420 | 1741 (6%) | 514 (5%) | −0.67 | 0.83 (0.74, 0.92) | 0.73 (0.58, 0.92) | 0.35 |

| PCKD | 9990 | 2746 | 1640 (16%) | 487 (18%) | 1.31 | 1.30 (1.17, 1.45) | 1.32 (1.05, 1.67) | 0.61 |

| Other/unknown | 35,926 | 12,245 | 4201 (12%) | 1799 (15%) | 3.00 | 1.24 (1.12, 1.36) | 1.54 (1.24, 1.91) | 0.08 |

| EPTS score at transplant | ||||||||

| >20% or unknown | 80,910 | 27,237 | 6507 (8%) | 2444 (9%) | 0.93 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| ≤20% (top 20) | 30,243 | 9347 | 3538 (12%) | 1159 (12%) | 0.70 | 3.72 (3.45, 4.01) | 4.69 (4.07, 5.40) | 0.02a |

| KDPI score | ||||||||

| ≤85%/unknown | 98,564 | 33,336 | 9110 (9%) | 3371 (10%) | 0.87 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| >85% (high KDPI) | 12,589 | 3248 | 935 (7%) | 232 (7%) | −0.29 | 0.81 (0.75, 0.87) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.76) | 0.16 |

| HLA mismatch | ||||||||

| Nonzero MM/unknown | 99,194 | 35,237 | 8306 (8%) | 3330 (9%) | 1.08 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Zero mismatch | 11,959 | 1347 | 1739 (15%) | 273 (20%) | 5.73 | 1.47 (1.39, 1.57) | 1.55 (1.33, 1.81) | 0.41 |

| PRA sensitization | ||||||||

| PRA <80% | 100,057 | 2650 | 8845 (9%) | 172 (6%) | −2.35 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| PRA 80%–97% | 6248 | 170 | 529 (8%) | 14 (8%) | −0.23 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | 1.10 (0.59, 2.08) | 0.50 |

| PRA 98%–100% | 2756 | 164 | 192 (7%) | 7 (4%) | −2.70 | 0.73 (0.62, 0.85) | 0.54 (0.24, 1.22) | 0.46 |

| Unknown | 2092 | 33,600 | 479 (23%) | 3410 (10%) | −12.75 | 2.12 (1.89, 2.38) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.46) | <0.001a |

| ABO blood type | ||||||||

| O | 50,025 | 16,560 | 3842 (8%) | 1336 (8%) | 0.39 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| A | 40,448 | 12,873 | 4300 (11%) | 1512 (12%) | 1.12 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.28) | 0.93 |

| B | 14,731 | 5171 | 1131 (8%) | 468 (9%) | 1.37 | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20) | 1.20 (1.06, 1.35) | 0.35 |

| AB | 5949 | 1980 | 772 (13%) | 287 (14%) | 1.51 | 1.62 (1.49, 1.78) | 1.53 (1.31, 1.78) | 0.55 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| No/unknown | 72,410 | 22,865 | 7264 (10%) | 2499 (11%) | 0.90 | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Yes | 38,743 | 13,719 | 2781 (7%) | 1104 (8%) | 0.87 | 1.43 (1.32, 1.55) | 1.67 (1.47, 1.90) | 0.97 |

| Transplant year | ||||||||

| Additional year | 111,153 | 36,584 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.43 | |||

| Total (era row %) | 111,153 | 36,584 | 10,045 (9.0%) | 3603 (9.8%) | 0.81 | |||

Percentages presented in the table are row percentages (% preemptive in each era). “Absolute difference in % preemptive or age” was calculated by subtracting the percentage of transplants occurring preemptively in the pre-KAS era from the percentage occurring preemptively in the post-KAS era, or the pre-KAS mean age from the post-KAS mean age. A positive value indicates a greater proportion of transplants occurred preemptively for this subgroup after implementation of KAS, and a negative value indicates the proportion decreased after KAS. Adjusted model includes all characteristics in this table. P value is for interaction term between policy era and the characteristic. KAS, Kidney Allocation System; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease; EPTS, estimated post-transplant survival; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index; HLA, Human Leukocyte Antigen; MM, mismatch; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Indicates statistical significance at the α = 0.05 level.

Odds ratio is for a 10-year increase in age.

Value presented for age is mean (±SD).

Kidneys with KDPI >85% remained equally less likely to be used preemptively compared with KDPI ≤85% organs across policy eras pre-KAS (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.84) and post-KAS (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.79). The mean KDPI of preemptively transplanted kidneys decreased significantly from 44.14±28.01 pre-KAS to 41.29±26.60 post-KAS (P<0.001), but the mean KDPI for organs used nonpreemptively did not change (48.39±27.88 and 48.33±26.19; P=0.71).

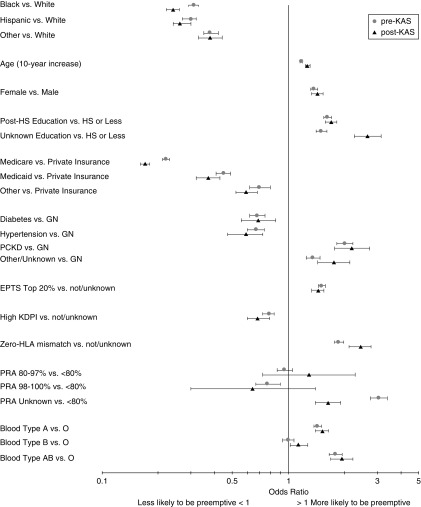

For every decade increase in recipient age, the unadjusted OR of preemptive transplantation increased from 1.17 (95% CI, 1.15 to 1.19) pre-KAS to 1.26 (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.30) post-KAS. Organs resulting in zero HLA-mismatch transplants were even more likely to be used preemptively post-KAS (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 2.12 to 2.79) compared with pre-KAS (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.76 to 1.97). Nonwhite race/ethnicity and insurance (Medicare or Medicaid versus private) had the strongest unadjusted associations with preemptive transplantation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ORs for unadjusted associations with preemptive deceased donor transplantation pre-KAS (2000–2013) and post-KAS (2015–2018). KAS, Kidney Allocation System; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease.

Median waiting time, defined as the time from listing to transplantation, was lower for both preemptive and nonpreemptive recipients immediately after KAS. However, although median waiting time was significantly shorter for recipients of preemptive transplants in both the pre- and post-KAS eras, it steadily increased after KAS for preemptive recipients only (Supplemental Figure 1).

Comparing Adjusted Characteristics before and after KAS

After adjusting for recipient/transplant characteristics in multivariable analysis, significant differences in OR of preemptive deceased donor transplantation by policy era persisted for race (black versus white), insurance status (Medicare versus private), and recipient age (all interaction term P<0.05), but not for HLA zero-mismatch or Medicaid versus private insurance (Table 2). The adjusted associations between preemptive transplantation and sex, education (post-high school versus high school or less), ESKD cause, KDPI, diabetes, and ABO blood type did not vary significantly by policy era. Although there was no significant interaction by policy era on the relationships between preemptive transplantation and EPTS group or Hispanic race (versus white) in the unadjusted models, these interactions became significant in the adjusted model (P=0.02 and P=0.04, respectively).

The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of preemptive transplantation comparing black and white patients was lower post-KAS (0.41; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.45) than pre-KAS (0.48; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.51). Hispanics also had a lower aOR compared with whites post-KAS (0.40; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.46) than pre-KAS (0.43; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.47). The aOR of preemptive transplantation for patients with Medicare (versus private insurance) was 0.20 (95% CI, 0.18 to 0.22) post-KAS and 0.26 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.27) pre-KAS. Increasing recipient age remained significantly associated with preemptive transplantation and became more pronounced post-KAS. For transplants occurring post-KAS, each decade increase in recipient age corresponded with 2.09 (95% CI, 1.99 to 2.20) times higher odds of receiving the transplant preemptively compared with 1.69 (95% CI, 1.64 to 1.74) times higher odds pre-KAS (all interaction term P<0.05).

HLA zero-mismatch transplants remained more likely to be preemptive than nonzero HLA mismatch transplants post-KAS (aOR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.33 to 1.81) with no significant difference by policy era (interaction term P=0.41). Similarly, high KDPI organs remained less likely to be used for preemptive transplants post-KAS (aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.76) with no significant modification by policy era (P=0.16). There was inadequate power to detect an adjusted association between PRA sensitization and likelihood of preemptive transplant after 2014 because of low event counts among the highly sensitized groups and a very high proportion of individuals with unknown PRA (33,600 of 36,584 post-KAS recipients).

Sensitivity Analyses

To evaluate whether the key post-KAS disparities we identified held steady over time, unadjusted ORs were calculated stratifying by post-KAS policy year for likelihood of preemptive transplant by race/ethnicity and primary insurance payer (Table 3). When testing for significant interaction between post-KAS transplant year and race or insurance, all racial and insurance disparities remained consistent across the post-KAS time period. We compared a 2016–2018 post-KAS group (n=26,950) with a 2011–2013 pre-KAS group (n=26,683) and found that after excluding potential bolus effect transplants in 2015, black transplant recipients were even less likely than white transplant recipients to receive their transplant preemptively in the post-KAS era than in the pre-KAS era (unadjusted and adjusted model interaction terms P<0.05). Similarly, transplant recipients with Medicare or Medicaid remained significantly less likely to receive their transplant preemptively compared with recipients with private insurance in the new post-KAS versus pre-KAS era in the unadjusted model (interaction terms P<0.05). In the adjusted model, the measures of association were again lower post-KAS, but the interaction terms between insurance and policy era were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 3.

Unadjusted associations between key disparities and preemptive deceased donor transplantation, stratified by post-KAS year

| Characteristic | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018a | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preemptive (%) | Preemptive (%) | Preemptive (%) | Preemptive (%) | ||

| n=838 (8.70%) | n=1020 (9.49%) | n=1156 (10.17%) | n=589 (12.19%) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Black | 0.21 (0.18, 0.26) | 0.25 (0.21, 0.29) | 0.26 (0.22, 0.30) | 0.25 (0.19, 0.31) | 0.37 |

| Hispanic | 0.29 (0.23, 0.36) | 0.24 (0.19, 0.29) | 0.27 (0.22, 0.33) | 0.27 (0.20, 0.35) | 0.84 |

| Other | 0.36 (0.28, 0.48) | 0.32 (0.24, 0.41) | 0.41 (0.33, 0.51) | 0.46 (0.34, 0.62) | 0.13 |

| Primary payer | |||||

| Private | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Medicare | 0.15 (0.13, 0.17) | 0.18 (0.16, 0.21) | 0.18 (0.16, 0.20) | 0.18 (0.14, 0.22) | 0.20 |

| Medicaid | 0.33 (0.25, 0.43) | 0.38 (0.30, 0.49) | 0.38 (0.30, 0.49) | 0.42 (0.29, 0.62) | 0.38 |

| Other/unknown | 0.39 (0.25, 0.62) | 0.52 (0.35, 0.76) | 0.55 (0.38, 0.78) | 0.62 (0.50, 0.77) | 0.12 |

Preemptive (%) refers to the count of preemptive transplants that occurred during that year, and what percentage of all transplants that year were preemptive. KAS, Kidney Allocation System; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

2018 data only available through May 2018.

P value is for interaction term between categorical characteristic and continuous post-KAS transplant date.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis restricting the extensive pre-KAS time period and excluding potential 2015 bolus effects: unadjusted and adjusted associations with preemptive deceased donor transplantation, before KAS (2011–2013) and after KAS (2016–2018)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-KAS | Post-KAS | P Value | Pre-KAS | Post-KAS | P Value | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Black | 0.31 | (0.28, 0.35) | 0.25 | (0.23, 0.28) | 0.004b | 0.50 | (0.45, 0.57) | 0.42 | (0.37, 0.47) | 0.004b |

| Hispanic | 0.30 | (0.26, 0.35) | 0.26 | (0.23, 0.29) | 0.09 | 0.46 | (0.40, 0.54) | 0.39 | (0.34, 0.45) | 0.10 |

| Other | 0.38 | (0.32, 0.45) | 0.39 | (0.33, 0.45) | 0.84 | 0.40 | (0.33, 0.48) | 0.44 | (0.38, 0.52) | 0.40 |

| Age at transplant | ||||||||||

| Yearsc | 1.26 | (1.22, 1.31) | 1.27 | (1.23, 1.31) | 0.80 | 1.87 | (1.77, 1.98) | 2.16 | (2.04, 2.29) | 0.05b |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Female | 1.51 | (1.40, 1.64) | 1.48 | (1.37, 1.60) | 0.69 | 1.55 | (1.41, 1.69) | 1.43 | (1.31, 1.56) | 0.11 |

| Education level | ||||||||||

| High school or less | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Post-high school education | 1.64 | (1.50, 1.78) | 1.67 | (1.54, 1.82) | 0.70 | 1.22 | (1.11, 1.34) | 1.12 | (1.02, 1.23) | 0.71 |

| Unknown | 1.70 | (1.42, 2.05) | 2.53 | (2.09, 3.06) | 0.004b | 1.51 | (1.23, 1.84) | 1.77 | (1.43, 2.20) | 0.15 |

| Primary payer | ||||||||||

| Private | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Medicare | 0.21 | (0.19, 0.23) | 0.18 | (0.16, 0.20) | 0.02b | 0.24 | (0.21, 0.26) | 0.20 | (0.18, 0.22) | 0.05 |

| Medicaid | 0.51 | (0.43, 0.62) | 0.39 | (0.33, 0.46) | 0.03b | 0.83 | (0.68, 1.02) | 0.71 | (0.60, 0.85) | 0.11 |

| Other/unknown | 0.51 | (0.39, 0.66) | 0.62 | (0.53, 0.71) | 0.22 | 0.57 | (0.44, 0.76) | 0.65 | (0.55, 0.77) | 0.29 |

| ESKD cause | ||||||||||

| GN | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Diabetes | 0.55 | (0.44, 0.67) | 0.68 | (0.54, 0.87) | 0.17 | 0.55 | (0.42, 0.71) | 0.52 | (0.39, 0.69) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension | 0.64 | (0.52, 0.79) | 0.58 | (0.46, 0.75) | 0.59 | 0.76 | (0.61, 0.96) | 0.72 | (0.55, 0.94) | 0.75 |

| PCKD | 1.69 | (1.36, 2.10) | 2.16 | (1.68, 2.77) | 0.15 | 1.12 | (0.88, 1.42) | 1.34 | (1.02, 1.75) | 0.29 |

| Other/unknown | 1.35 | (1.10, 1.65) | 1.78 | (1.41, 2.25) | 0.07 | 1.31 | (1.05, 1.62) | 1.58 | (1.23, 2.03) | 0.22 |

| EPTS score at transplant | ||||||||||

| >20% or unknown | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| ≤20% (top 20) | 1.34 | (1.22, 1.46) | 1.45 | (1.33, 1.58) | 0.20 | 3.43 | (2.93, 4.01) | 4.94 | (4.20, 5.81) | 0.91 |

| KDPI score | ||||||||||

| ≤85%/unknown | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| >85% (high KDPI) | 0.78 | (0.68, 0.90) | 0.70 | (0.60, 0.82) | 0.30 | 0.74 | (0.64, 0.86) | 0.65 | (0.55, 0.78) | 0.48 |

| HLA mismatch | ||||||||||

| Nonzero MM/unknown | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Zero mismatch | 1.83 | (1.60, 2.10) | 2.42 | (2.06, 2.83) | 0.009b | 1.40 | (1.21, 1.63) | 1.64 | (1.37, 1.96) | 0.15 |

| PRA sensitizationd | ||||||||||

| PRA <80% | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| PRA 80%–97% | 1.11 | (0.94, 1.31) | – | – | – | 0.89 | (0.74, 1.07) | – | – | – |

| PRA 98%–100% | 0.63 | (0.45, 0.89) | – | – | – | 0.58 | (0.40, 0.83) | – | – | – |

| Unknown | 1.83 | (1.57, 2.13) | 1.73 | (1.30, 2.28) | 0.72 | 1.34 | (1.13, 1.58) | 1.34 | (0.99, 1.81) | 0.92 |

| ABO blood type | ||||||||||

| O | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| A | 1.55 | (1.41, 1.69) | 1.50 | (1.37, 1.64) | 0.64 | 1.35 | (1.22, 1.48) | 1.17 | (1.06, 1.29) | 0.13 |

| B | 0.98 | (0.85, 1.12) | 1.12 | (0.99, 1.27) | 0.15 | 1.09 | (0.94, 1.26) | 1.20 | (1.04, 1.38) | 0.35 |

| AB | 1.83 | (1.56, 2.15) | 1.86 | (1.58, 2.19) | 0.87 | 1.71 | (1.44, 2.04) | 1.44 | (1.21, 1.73) | 0.27 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||

| No | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||

| Yes | 0.62 | (0.57, 0.68) | 0.71 | (0.65, 0.77) | 0.04b | 1.20 | (1.03, 1.40) | 1.71 | (1.47, 1.98) | 0.009b |

| Transplant year | ||||||||||

| Additional year | 1.03 | (0.98, 1.08) | 1.14 | (1.08, 1.20) | 0.006b | 1.04 | (0.99, 1.10) | 1.04 | (0.98, 1.11) | 0.86 |

P value is for the interaction term between policy era and the characteristic. KAS, Kidney Allocation System; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease; EPTS, estimated post-transplant survival; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index; HLA, Human Leukocyte Antigens; MM, mismatch; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Adjusted model includes all predictors in this table.

Indicates statistical significance at the α = 0.05 level.

OR is for a 10-year increase in age.

Post-KAS PRA analyses could not be performed for this time range because of the extent of missing data.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis including working status and any Medicaid history to further assess the association of socioeconomic status with preemptive transplantation. Although this analysis was limited by a large proportion of missing data (75% missing data for at least one variable used to define these characteristics), recipients who were not working or who had any Medicaid coverage history were associated with lower likelihood of preemptive transplantation (Supplemental Table 2). The addition of these variables to the adjusted model did not meaningfully change the aORs of preemptive transplantation by race, educational status, or other demographic variables (Supplemental Table 3).

Comparison with Preemptive Living Donor Transplantation

The proportion of living donor transplants occurring preemptively steadily increased both before and after KAS implementation, from 27% in 2000 to 39% in 2017 (Supplemental Figure 2). As with deceased donor transplantation, nonwhite race, public insurance, and lower educational attainment were associated with lower likelihood of preemptive living donor transplantation. However, these relationships did not significantly change after KAS implementation in unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

Kidney transplantation is the preferred modality of kidney replacement therapy with the greatest benefit to those who are preemptively transplanted before dialysis initiation (2,4,6,8,21,22). However, significant racial, socioeconomic, and demographic disparities exist for both access to transplantation and likelihood of preemptive transplantation (4,11,12). Although overall racial disparities in deceased donor kidney transplantation have decreased after KAS implementation (17), we identified an unintended exacerbation of significant disparities in preemptive deceased donor transplantation. We found nonwhite race, younger age, male sex, lower educational attainment, and public primary insurer were all associated with lower odds of preemptive transplantation in the post-KAS era. These increased disparities were driven by a greater increase in preemptive transplantation among white patients and those with private health insurance compared with other groups.

The proportion of transplants occurring preemptively among first-time deceased donor recipients increased slightly post-KAS, but this increase was not shared equally among racial groups. Even after adjusting for potential confounders, the disparity in preemptive transplants between blacks or Hispanics compared with whites widened by 21% and 9% (log-scale), respectively, after KAS implementation. Given the post-KAS prioritization for those with the longest dialysis time and previous racial disparities to wait-listing, an initial bolus of black candidates with long dialysis times could have contributed to this finding (23). However, the persistence of this disparity in 2018, several years after the implementation of KAS when the bolus effect has waned, argues against this being a transient phenomenon. Additionally, our sensitivity analysis stratified by post-KAS transplant year did not identify temporal trends. Analysis excluding the potential bolus effect in 2015 reaffirmed the persistence of racial and insurance-based disparities in the post-KAS era. Further studies are needed to understand racial disparities in rates of preemptive transplants as more data post-KAS become available, but minority patients currently remain at a distinct disadvantage in ability to obtain a preemptive transplant.

Minority populations, including blacks and Hispanics, are less likely to receive a transplant (12) despite having a higher burden of ESKD (1). The racial disparity in rates of wait-listing between black and white patients decreased after KAS, but white patients remained more likely to be waitlisted for a deceased donor transplant and overall rates of wait-listing declined (24). Although the decrease in rates of overall wait-listing is another potential unintended consequence of the new allocation calculation under KAS, post-KAS changes in access to transplantation remain unclear—except, perhaps, for the spillover it appears to be having on preemptive transplantation. Potential barriers to equal access to transplantation and preemptive transplantation include inadequate early access to nephrology care, limited education from health providers, and potential bias from clinicians in referring black patients for transplant (25). Additional barriers may include socioeconomic insecurity, unequal geographic distribution of and access to transplant centers, and greater HLA mismatch with deceased donor organs due to disproportionate racial distribution in the donor pool (12). Wait-listing timing among minority populations should also be considered given potentially faster rates of disease progression (26,27) to allow for the possibility of preemptive transplantation and associated benefits. Although not all preemptively wait-listed patients will receive a preemptive transplant, they will all likely experience less time on dialysis before transplantation. Because pretransplant dialysis time is one of the few modifiable factors associated with long-term allograft outcomes (2), strategies promoting preemptive wait-listing will benefit all patients with ESKD. Addressing barriers minority populations face in accessing timely pre-ESKD specialty care and transplant center referral and focusing on improving early education about treatment options will improve earlier wait-listing as well as countering any potential loss of sense of urgency among providers for wait-listing under KAS.

We also found patients without private insurance were significantly less likely to receive a preemptive deceased donor transplant, with a 19% widening in the disparity (log-scale) between Medicare and private insurance holders after KAS. Private insurance holders had five times higher adjusted odds of receiving a transplant preemptively compared with Medicare recipients post-KAS, which is a dramatic increase compared with prior studies (11). We suspect patients’ primary insurance payer could be associated with their access to early specialty care, and early nephrologist care and timing of first discussions about transplantation have been associated with preemptive wait-listing (28). Additionally, although a diagnosis of ESKD provides Medicare eligibility, predialysis CKD alone does not. This differential access to Medicare among preemptive versus nonpreemptive patients may explain some of the observed disparity between patients covered by private insurance versus Medicare. Patients may also find out-of-pocket expenses are a deterrent to transplantation, particularly in the absence of secondary insurance. However, changes in data capture of secondary insurance information for part of the period of interest limited our ability to study this in detail. The relationship between state-level changes in Medicaid eligibility and preemptive transplantation also warrants further study, especially given evidence that states that have implemented Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act have demonstrated an increase in preemptive listing for kidney transplantation (29).

Rates of preemptive deceased donor transplant also differed by ESKD cause and were not significantly modified by policy era. Overall, GN (9% preemptive) and polycystic kidney disease (16%) had higher proportions of preemptive transplant than diabetes (6%) and hypertension (6%), likely reflecting earlier access to nephrology care. Factors associated with early nephrologist referral, such as having a biopsy-proven diagnosis of GN, likely influence timing and decisions for preemptive wait-listing. Strategies to improve preemptive wait-listing and transplantation will require educating primary care physicians around nephrology referral, educating nephrologists about the benefits of preemptive transplantation, improved treatment modality counseling, and simplifying the transplant evaluation process (30).

We corroborated the previous finding that older patients were more likely to receive a deceased donor kidney transplant preemptively (11), but we also found the relationship between age and likelihood of preemptive transplantation became significantly stronger post-KAS for unclear reasons. The quality of kidneys being used for preemptive transplants improved after 2014, and transplants with HLA zero-mismatch remained significantly more likely to occur preemptively. We found that although median waiting time between wait-listing and transplantation was lower for preemptive recipients than nonpreemptive recipients, this difference has recently decreased, driven by a steady increase in median waiting time for preemptive recipients since 2015, as expected. We also found that the proportion of living donor transplants performed preemptively has steadily increased over time both before and after KAS implementation. However, in contrast to deceased donor kidney transplantation, disparities in access to preemptive living donor transplantation did not change after KAS.

Given the benefits of preemptive transplantation for post-transplant outcomes and survival (2–6), disparities in access on the basis of nonclinical, sociodemographic characteristics are particularly troubling for larger goals of health equity. Disparities in key sociodemographic characteristics such as race, age, sex, and education persisted after KAS and should be targeted in policy or clinical practice to work toward equal opportunity for better patient outcomes and quality of life after transplantation.

Although strengths of this study include using a large, nationally representative cohort and being the first-known study looking for changes in preemptive transplantation disparities after KAS, there are limitations. The observational nature of the study risks residual confounding due to characteristics not captured in the registry or included in this study. There were many unknown/missing values for hypertension, PRA, education, and acute rejection episodes that could bias those measures of association. PRA analyses after 2014 suffered from lack of adequate power to draw conclusions because the highest sensitization group (PRA of 98%–100%) of interest clinically and policy-wise contained too few patients post-KAS. As more post-KAS data become available, further studies on the relationship between PRA sensitization and preemptive transplantation should be done. Socioeconomic status may be associated with factors such as access to care and early transplant referral, which would in turn affect the likelihood of preemptive transplantation. Although limitations in our dataset precluded our ability to examine the potential relationship between socioeconomic status on preemptive referral, we recognize this is an important question that needs further study.

In conclusion, significant disparities in preemptive kidney transplantation persist and appear to have been exacerbated after KAS, especially regarding race and insurance, despite an overall increase in the proportion of kidneys transplanted preemptively. Increased disparity between those with private insurance and those without suggests larger health policy issues around equal access to care. Because preemptive transplantation is associated with improved patient and graft outcomes, further efforts to reduce disparities in access on the basis of sociodemographic characteristics are needed to achieve more equitable outcomes for patients with ESKD.

Disclosures

Outside the submitted work, Dr. Mohan reports personal fees from CMS, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Kidney International Reports and other fees from Bravado Health. Dr. Mohan also reports personal and other fees from Angion Pharmaceuticals outside of the submitted work, as well as being a member of their Scientific Advisory Board. Mr. Brennan, Dr. Husain, Dr. Jin, and Ms. King have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Mohan is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK114893 and U01 DK116066). Dr. Husain is supported by the Young Investigator Award from the National Kidney Foundation. The funders did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute as the contractor for the SRTR. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Persistent Disparities in Preemptive Kidney Transplantation,” on pages 1430–1431.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03140319/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Unadjusted associations with preemptive deceased donor kidney transplantation, before and after KAS.

Supplemental Table 2. Sensitivity analysis incorporating additional socioeconomic variables: unadjusted associations with preemptive transplantation, overall, pre-KAS (2000–2013), and post-KAS (2015–2018).

Supplemental Table 3. Sensitivity analysis incorporating additional socioeconomic variables: adjusted associations with preemptive transplantation pre-KAS (2000–2013) and post-KAS (2015–2018).

Supplemental Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted associations with preemptive transplantation among living donor kidney transplant recipients, before and after KAS.

Supplemental Figure 1. Median waiting time between addition to the waitlist or starting dialysis and receiving a deceased donor kidney transplant.

Supplemental Figure 2. Proportion of living and deceased donor kidney transplants occurring preemptively over time, by donor type.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : Incidence, Prevalence, Patient Characteristics, and Treatment Modalities. 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Chapter 1, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B: Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: A paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation 74: 1377–1381, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosio FG, Alamir A, Yim S, Pesavento TE, Falkenhain ME, Henry ML, Elkhammas EA, Davies EA, Bumgardner GL, Ferguson RM: Patient survival after renal transplantation: I. The impact of dialysis pre-transplant. Kidney Int 53: 767–772, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT: Preemptive kidney transplantation: The advantage and the advantaged. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1358–1364, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jay CL, Dean PG, Helmick RA, Stegall MD: Reassessing preemptive kidney transplantation in the United States: Are we making progress? Transplantation 100: 1120–1127, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI: Effect of the use or nonuse of long-term dialysis on the subsequent survival of renal transplants from living donors. N Engl J Med 344: 726–731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malho A, Malheiro J, Fonseca I, Martins LS, Pedroso S, Almeida M, Dias L, Castro Henriques A, Cabrita A: Advantages of kidney transplant precocity in graft long-term survival. Transplant Proc 44: 2344–2347, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis CL: Preemptive transplantation and the transplant first initiative. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 592–597, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedewald JJ, Reese PP: The kidney-first initiative: What is the current status of preemptive transplantation? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 19: 252–256, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI: Dialysis prior to living donor kidney transplantation and rates of acute rejection. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 172–177, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grams ME, Chen BP, Coresh J, Segev DL: Preemptive deceased donor kidney transplantation: Considerations of equity and utility. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 575–582, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee CM, Lertdumrongluk P, Streja E, Park J, Moradi H, Lau WL, Norris KC, Nissenson AR, Amin AN, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Impact of age, race and ethnicity on dialysis patient survival and kidney transplantation disparities. Am J Nephrol 39: 183–194, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi S, Gaynor JJ, Bayers S, Guerra G, Eldefrawy A, Chediak Z, Companioni L, Sageshima J, Chen L, Kupin W, Roth D, Mattiazzi A, Burke GW 3rd, Ciancio G: Disparities among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in time from starting dialysis to kidney transplant waitlisting. Transplantation 95: 309–318, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Braun WE, Shoskes DA, Nurko S, Poggio ED: The relative risk of overall graft loss and acute rejection among African American renal transplant recipients is attenuated with advancing age. Clin Transplant 25: 721–730, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fissell RB, Srinivas T, Fatica R, Nally J, Navaneethan S, Poggio E, Goldfarb D, Schold J: Preemptive renal transplant candidate survival, access to care, and renal function at listing. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3321–3329, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Israni AK, Salkowski N, Gustafson S, Snyder JJ, Friedewald JJ, Formica RN, Wang X, Shteyn E, Cherikh W, Stewart D, Samana CJ, Chung A, Hart A, Kasiske BL: New national allocation policy for deceased donor kidneys in the United States and possible effect on patient outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1842–1848, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melanson TA, Hockenberry JM, Plantinga L, Basu M, Pastan S, Mohan S, Howard DH, Patzer RE: New kidney allocation system associated with increased rates of transplants among Black and Hispanic patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 36: 1078–1085, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP : Healthy People 2020: CKD-13.2. Washington, DC: 2014. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Chronic-Kidney-Disease/objectives#4085. Accessed May 14, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wetmore JB, Liu J, Li S, Hu Y, Peng Y, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ: The healthy people 2020 objectives for kidney disease: How far have we come, and where do we need to go? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 200–209, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaboré R, Haller MC, Harambat J, Heinze G, Leffondré K: Risk prediction models for graft failure in kidney transplantation: A systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32[suppl_2]: ii68–ii76, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier-Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, Rudich SM, Hanson JA, Cibrik DM, Leichtman AB, Kaplan B: Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney Int 58: 1311–1317, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz F, Aronen P, Koskinen PK, Malmström RK, Finne P, Honkanen EO, Sintonen H, Roine RP: Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation: Who benefits the most? 27: 1143–1151, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart DE, Kucheryavaya AY, Klassen DK, Turgeon NA, Formica RN, Aeder MI: Changes in deceased donor kidney transplantation one year after KAS implementation. Am J Transplant 16: 1834–1847, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Melanson TA, Plantinga LC, Basu M, Pastan SO, Mohan S, Howard DH, Hockenberry JM, Garber MD, Patzer RE: Racial/ethnic disparities in waitlisting for deceased donor kidney transplantation 1 year after implementation of the new national kidney allocation system. Am J Transplant 18: 1936–1946, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding K, Mersha TB, Webb FA, Vassalotti JA, Nicholas SB: Current state and future trends to optimize the care of African Americans with end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol 46: 156–164, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG: Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2902–2907, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suarez J, Cohen JB, Potluri V, Yang W, Kaplan DE, Serper M, Shah SP, Reese PP: Racial disparities in nephrology consultation and disease progression among veterans with CKD: An observational cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2563–2573, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Johansen KL: Impact of race on predialysis discussions and kidney transplant preemptive wait-listing. Am J Nephrol 35: 305–311, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harhay MN, McKenna RM, Boyle SM, Ranganna K, Mizrahi LL, Guy S, Malat GE, Xiao G, Reich DJ, Harhay MO: Association between medicaid expansion under the affordable care act and preemptive listings for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1069–1078, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishbane S, Nair V: Opportunities for increasing the rate of preemptive kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1280–1282, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.