Abstract

The financial impact of cancer treatment among adolescents and young adults (AYAs, 15–39 years) is deep and long lasting. Compared with other age groups, because of their life stage, AYAs are particularly vulnerable to the adverse economic effects of cancer treatment, also known as financial toxicity. Clinical manifestations of cancer-related financial toxicity include interrupted work and income loss, accumulated debt, treatment nonadherence, avoidance of medical care, and social isolation. Effective clinical interventions should include efforts to increase financial self-efficacy as well as direct support. Measures that are valid, reliable, multidimensional, and age-appropriate are needed to study and address financial toxicity in the AYA population.

Keywords: adolescent and young adult oncology, AYA, cancer, financial impact, financial toxicity, outcomes research, psychosocial, quality of life, supportive care

1 |. INTRODUCTION

More than a decade has passed since the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Progress Review Group published its landmark report, “Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer.”1 Calling attention to outcome disparities and unmet needs of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer (AYAs being defined by the US NCI as patients 15–39 years of age), “Closing the Gap” identified several factors inhibiting progress in this population. Listed first among those is a financial factor, namely limited health insurance and its adverse impact on access to care. At the time “Closing the Gap” was published in 2006, AYAs had a lower level of health insurance coverage than any other group of Americans.2 Especially affected were those in their early to mid-twenties, of whom approximately 30% were uninsured, due to gaps in coverage created by both federal and private health insurance program restrictions.3,4 Several other important financial issues were identified in “Closing the Gap,” including high levels of health-related debt; substantial out-of-pocket costs not covered by insurance; future non insurability, coverage restrictions, and excessive premiums; and limited employment opportunities.1 Now, more than 10 years on, how are AYAs with cancer faring from a financial perspective?

The answer is as mixed as it is incomplete. On the one hand, in 2010 the US Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA), offering hope of expanded health insurance and access to care for millions of Americans, including AYAs with cancer. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, only 2 years after ACA passage over 3 million young adults had gained health insurance coverage, consisting almost entirely of those 19–25 years of age.5 According to the Commonwealth Fund, in the first year of the ACA an estimated 13.7 million young adults stayed on or joined their parents’ health plans, for almost half of whom it would not have been possible without the ACA.6 On the other hand, health insurance coverage under the ACA is highly variable by state. For example, US Census Survey data indicate that while in California the proportion of uninsured in the general population decreased from 25% to 10% between 2011 and 2017, in Texas it decreased only from 34% to 24%, still twice the national average of 12% uninsured.7 Among AYAs with cancer, a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study documented that 83.5% of 18–25 year olds had health insurance before the ACA, which increased to 85.4% after implementation of the ACA, although the insured rate actually dropped from 83.4% to 82.9% among those aged 26–29 years.8 Even within California, among AYAs with cancer aged 22–29 years improved insurance coverage post ACA was greatest among Whites and Asians in high-income neighborhoods.9

At the patient level, there are several financial implications of cancer diagnosis and treatment that are pertinent, regardless of insurance status. Moreover, insurance coverage is highly variable with respect to type and comprehensiveness. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the financial impact of cancer among AYAs. Because financial consequences of cancer can be considered a form of treatment-related toxicity that has only recently begun to be fully appreciated, we include discussion of how this adverse effect may be defined, measured, and graded.

2 |. DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Adolescence and young adulthood is normally a time of growth, opportunity, and achieving important developmental milestones, which include separating from parents, exploring romantic relationships, connecting with peers, and pursuing educational and vocational opportunities. Consequently, cancer is particularly disruptive for AYAs. As discussed further below, financial hardships likely vary by developmental stage for adolescents (ages 15–19 years), emerging adults (ages 20–25 years), and young adults (ages 26–39 years).

Adolescents resemble the pediatric population, as they are similarly dependent on parents or guardians for financial support. Although these youngest AYAs may be somewhat “insulated” from the experience of financial hardship, their families are not. Increased family financial burden includes work disruptions for the parent and out-of-pocket expenses (e.g., transportation, child care, and food).10 These expenses are estimated to represent one-third of after-tax family income based upon a Canadian study11 and an annual income loss of over 40% for over half of families with lower incomes in one US-based study.12

The term “emerging adulthood” was coined to capture a distinct developmental phase extending from the late teens through the twenties.13 This phase represents a prolonged period of independent role exploration involving love, work, and worldview. Emerging adults are financially “in transition” and are at risk for deleterious financial effects of cancer. Disrupted higher education or career goals can compromise AYA earning potential.14 By undermining both financial and personal independence, these forces may result in the “failure to launch” phenomenon of some AYAs.

Compared with emerging adults, AYAs over approximately 30 years of age exhibit the most potential for financial stability and independence. They are more likely to have initiated their career, own a home, be married or in long-term partnerships, have children, and have more extensive social support networks. Their financial burden is centered on returning to work to preserve income, providing for dependents, and paying their mortgage and/or other debt while covering their medical expenses.15

Few studies have captured the financial issues experienced by AYAs across the developmental age strata, but the cross-sectional NCI AYA HOPE study reported on life experiences of AYAs recently diagnosed with cancer (n = 524). Negative financial impacts of cancer were reported by 69.5% and 64.9%, respectively, of the 21 to 29-year-old and 30 to 39-year-old subgroups, compared with 51.4% of 15–20years olds (P < 0.01). Among domains having a negative impact, finance was ranked first in the older cohorts and third in the youngest cohort (behind “feelings about the appearance of your body” and “plans for having children”).16 This underscores both the salience and variability of financial hardship among AYA subgroups.

3 |. FINANCIAL TOXICITY

3.1 |. Terminology

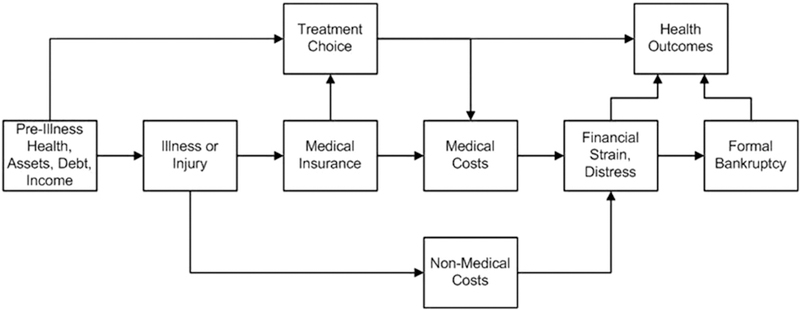

Several terms are used somewhat interchangeably to describe the financial experience of AYAs with cancer. Although several of these terms overlap (e.g., financial burden, financial distress, financial hardship, and financial toxicity), important nuances bear delineating (summarized in Table 1). In addition, the financial experience of AYAs with cancer is multifactorial and may result in far-reaching, adverse outcomes. A comprehensive conceptual framework of cancer and financial distress (Figure 1) is included in NCI’s Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment PDQ-Health Professional Version.17 This framework incorporates pre- and post cancer diagnosis risk factors that contribute to financial distress and health outcomes and incorporates material conditions (e.g., out-of-pocket medical expenses, medical debt, and loss of income) and psychological responses to cancer-related financial burden. Similarly,Tucker-Seeley and Yabroff18 have proposed a multidimensional framework of financial well-being that is informed by the health disparities literature19 and includes three key components—material resources to cover out-of-pocket costs, psychological responses to the financial consequences of cancer diagnosis and treatment, and behavioral strategies used to cope with the cancer care costs. Importantly, they note that the measures used to address these concepts vary considerably and lack specificity across the cancer care continuum or utility for assessing the same experience for patients and their families.

TABLE 1.

Common approaches to conceptualizing financial aspects of cancer care

| Terms | Definitions | References |

|---|---|---|

| Financial burden | A relatively objective measure of personal financial status, defined as the ratio of total out-of-pocket spending on health-related costs (medical and nonmedical expenses) to total household income | 68–71 |

| Financial distress | A subjective measure of the impact of financial burden on patient well-being; captures the affective experience and reflects the extent of worry, anxiety, or anguish about financial burden, experienced or anticipated | 72,73 |

| Financial hardship | Difficulty one might experience in attempting to secure financial resources; can be expressed in domains such as finances, health, and food (eg, difficulty paying bills, ongoing financial stress, medication reduction to reduce cost, food insecurity) | 1,36 |

| Financial toxicity | The adverse economic consequences to patients resulting from treatments and disease; conveys the harmful personal financial burden faced by patients receiving cancer treatment. Implicit is the notion that financial toxicity may be reduced through informed decision making about tests, procedures, and therapies that align with patients’ priorities and financial resources. | 24,28,29,31 |

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of cancer and financial toxicity. Image from the National Cancer Institute’s Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment (PDQ)–Health Professional Version (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-hp-pdq#cit/section_1.16)

3.2 |. Measures and grading systems

Currently, no gold standard exists for measuring the financial experiences of patients with cancer, including AYAs. Studies of cancer-related financial hardship have used a variety of measures including single-item indicators and multi-item measures, some of which are used primarily in the general population, and others that are cancer specific. The InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale20 is an eight-item self-report measure of current, subjective financial distress/financial well-being in the general population but is not currently validated in patients with cancer. Other approaches from the general population have used multiple indicators from large-scale national surveys. For example, Tucker-Seeley et al21 used 12 indicators from the Health & Retirement Study to assess the following aspects of financial hardship: (1) financial satisfaction, (2) making ends meet, (3) financial strain, (4) financial shortage, (5) move to a worse residence, (6) unemployment status, (7) job security, (8) receipt of unemployment income, (9) perceived income adequacy, (10) food security, (11) cost-related reduction in medication adherence, and (12) change in perceived socio-economic status.

Cancer-specific measures of financial hardship relating to AYAs are relatively sparse. The Cancer Self-Administered Questionnaire (CSAQ) is a survey developed through collaborative efforts of the NCI, American Cancer Society, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, LiveSTRONG, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to address knowledge gaps in cancer survivorship. The following four questions from the CSAQ address cancer-related financial problems: (1) Have you or anyone in your family had to borrow money or go into debt? (2) Have you or a family member made any other financial sacrifices? (3) Have you ever worried about paying large medical bills? (4) Have you been unable to cover the cost of medical care visits?22 Even briefer is the single item from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-Q30 which asks, “Has your physical condition or medical treatment caused you financial difficulties?”23 A more psychometrically robust but relatively brief measure of financial hardship is the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity measure, an 11-item self-report measure of the financial impact of illness.24 Recent psychometric testing has supported the internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity of the scale.25 Although the validation sample included 51 participants who were 50 years or less in age, there was no specific focus on AYAs. The issue of financial hardship, again not focused specifically on AYAs, is included in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Supplement.26 A similar perspective is taken in the NCI’s PDQ on financial toxicity and cancer treatment.17 The St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study has examined material, psychological, and coping or behavioral domains of financial hardship in adult survivors of cancer in childhood.27

Inasmuch as patients are informed about the biomedical toxicity of anticancer treatments, Ubel et al28 have advocated for full disclosure of the financial costs of treatment. Khera29 has proposed a graduated, standardized nomenclature for financial toxicity that parallels the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events30 (Table 2). Zafar31 has highlighted the clinical impact of financial toxicity by suggesting the link between extreme financial distress and worse mortality results from a combination of three factors—overall poorer well-being, impaired health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and suboptimal quality of care.

TABLE 2.

Grading financial toxicity as an adverse event

| Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.030 |

Prototype for Grading Financial Toxicity29 | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Mild; asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Lifestyle modification (deferral of large purchases or reduced spending on vacation and leisure activities) because of medical expenditure; use of charity grants/fundraising/copayment program mechanisms to meet costs of care |

| Grade 2 | Moderate; minimal, local, or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental activities of daily living | Temporary loss of employment resulting from medical treatment; need to sell stocks/investments for medical expenditure; use of savings accounts, disability income, or retirement funds for medical expenditure |

| Grade 3 | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care activities of daily living | Need to mortgage/refinance home to pay medical bills; permanent loss of job as a result of medical treatment; current debts > household income; inability to pay for necessities such as food or utilities |

| Grade 4 | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Need to sell home to pay for medical bills; declaration of bankruptcy because of medical treatment; need to stop treatment because of financial burden; consideration of suicide because of financial burden of care |

| Grade 5 | Death related to adverse event |

Given the degree to which adolescents and some emerging adults are insulated or “buffered” from the financial impact of their cancer care by their parents, it is important to consider the parental experience. The Survey about Caring for Children with Cancer32 included seven items used to evaluate the financial impact of child illness—annual family income, degree of financial hardship, missed work, estimated lost income, delayed large discretionary purchases (furniture, car), liquidated assets or incurring of debt to pay medical bills, and fundraising efforts. Although to date this measure has been focused on pediatric cancer,12 its utility may extend to the families of AYAs.

An NCI-sponsored State of the Science meeting on AYA Oncology in 2013 identified the need for “valid, reliable, developmentally relevant, and psychometrically robust measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL), overall and by subdomain...that cross the age spectrum and allow for studies of the full AYA age range.”33 The same qualities are needed in new measures of financial hardship in AYAs that can be used longitudinally and account for both the patient and family perspectives.

4 |. CLINICAL AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS

Cancer-related financial hardship is disproportionately greater among AYAs than among other age groups.14,22,34 AYAs with cancer may have no insurance or inadequate insurance coverage (often referred to as under-insurance or high out-of-pocket medical costs due to higher copays, co-insurances, and deductibles) and/or limited financial assets, and experience significant work interruption, leading to greater financial strain during and after treatment.14,15,35 An estimated productivity loss for adult survivors of AYA cancer was $4 564 compared with $2 314 (in 2010 dollars) for adults without a cancer history, underscoring the long-term financial burden on AYA survivors.22 Interestingly, despite the appearance of greater potential for financial independence, the impact of cancer appears to be more severe in AYAs 30–39 years old compared with younger AYAs, perhaps owing to the increased likelihood of dependent children and home ownership.15 Medical expenses were also greater for older AYAs and were four times greater in the oldest (ages 36–39) compared with the youngest (ages 19–21) quintile of AYAs who were applicants to The SamFund (a national nonprofit that provides direct financial assistance for AYA cancer survivors).15

Even with the advent of the ACA, employment-based health insurance is the primary source of insurance among AYAs. For this reason, work disruptions can jeopardize access to insurance and, combined with reduced earnings, lead to greater material and psychological financial hardship.36 A lack of health insurance can lead to challenges obtaining care for AYAs.37,38 Moreover, young adults39 who were uninsured or had Medicaid coverage were more likely to have advanced-stage disease and increased risk of death from cancer compared with young adults with private insurance.39,40 In a National Cancer Data Base study of 285 448 AYAs aged 15–39 years, noninsured status was associated with distant-stage disease at diagnosis for several cancers, including those amenable to early detection (melanoma, thyroid, breast, and genitourinary).41

A study investigating financial toxicity found that adult patients with cancer sometimes forego optimal cancer treatment in order to save money, including not taking prescription medications, not attending some oncology appointments, and/or turning down recommended procedures or tests.42 This is particularly concerning for AYAs who not only are at greater risk for financial burden but also demonstrate higher rates of cancer treatment nonadherence.43,44 A previous study found that survivors of AYA cancer were more likely to report not taking or taking less of a prescribed medication or delaying a medication refill to save costs in the previous year (23.8%) compared with a control group of peers without cancer (14.3%).45 There were higher rates of medication nonadherence for survivors without health insurance or who had public insurance compared with private insurance. Survivors of AYA cancer were also more likely to be unable to afford their medications, request less expensive medications, and substitute less costly alternative therapies for medications.45 Similarly, Kirchhoff et al38 found that a higher proportion of long-term survivors of AYA cancer (ages 20–39 years) reported cost-related avoidance of medical care in the past year compared with a control group of peers without cancer (21% vs 11%, respectively). Noninsurance among those who avoided medical care was more common for AYA survivors than controls (76% vs 48%); among AYA survivors, noninsurance was highest for those <30 years of age compared with older survivors (44% vs 26%, respectively).38 Results from the AYA HOPE study indicate that a lack of health insurance is not only a barrier to receiving medical care for AYA cancer survivors37 but is also associated with worse HRQOL.36

Patients with cancer also may change their lifestyle, such as spending less on food, clothing, and/or leisure activities due to the financial burden of cancer treatment.42 Social relationships and developing a social identity are critical developmental elements of adolescence and young adulthood; AYAs may be less likely to participate in social activities to defray costs due to cancer treatment, which, in turn, may lead to a negative impact on coping, mood, and overall QOL. In addition to social isolation, younger AYAs may depend on increased financial and/or practical support from parents/guardians or significant others, leading to a loss of autonomy and control.The link between treatment-related financial burden and poor quality of life has been supported in a few adult cancer studies.22,46 Family financial hardship in pediatric cancer treatment is associated with increased family and parental distress and burden on parental relationships.10 Research is needed to better understand the impact of financial toxicity on HRQOL and distress levels across the AYA cancer care continuum.

5 |. ADDRESSING FINANCIAL TOXICITY

Longitudinal assessment of financial burden for all AYA patients with cancer from diagnosis through survivorship care is a crucial first step towards identifying and addressing their financial needs. In pediatric oncology, assessment of family financial hardship is a standard of psychosocial care.10 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has supportive care guidelines for AYAs with cancer (version 2.2018)47 that recommend an assessment of availability, security, and risk of losing health insurance; risk of financial loss or hardship, including bankruptcy; and practical concerns and needs such as child care, transportation, and housing. More psychometrically robust measures are essential to assess the AYA experience of financial hardship across the continuum of care and across the developmental age range. Financial hardship can be captured as a multidimensional construct encompassing three domains (material, psychosocial, and behavioral)48 and can be most informative when the parent or family perspective is also included,10,49 especially for the youngest AYAs. Even though AYAs consider financial issues as one of their most important HRQOL concerns,50 none of the most common AYA measures of HRQOL51–53 capture this important experience while also spanning the full developmental age range. It would be valuable to include financial toxicity as a patient-reported outcome (PRO) in cancer clinical trials to complement measures of HRQOL and efforts are underway to develop and validate psychometrically robust PROs that are specifically tailored to the experiences of AYAs with cancer.54,55

Additionally, research on interventions or strategies to address financial toxicity is lacking, despite AYAs with cancer identifying financial burden as a salient concern.56 Many AYAs and their caregivers report unmet information needs related to financial support.57,58 The complexity of financial burden and its impact on health outcomes warrants a multifaceted intervention approach. Francoeur59 proposed the following three financial intervention approaches for patients with cancer and their families: (1) provide education about cost-saving financial methods and decision making; (2) improve and expand referrals to financial assistance programs and community resources; and (3) enhance coping and adaptation strategies to manage financial stress (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Financial interventions for AYAs with cancer

| Financial Intervention Approaches | Examples of Financial Resources, Services, and Programs |

|

|---|---|---|

| Education | • Provider-patient communication about cancer treatment costs |

Triage Cancer & The SamFund’s Cancer Finances: A Toolkit for Navigating Finances After Cancer |

| • Patient financial health literacy tools | (https://cancerfinances.org) | |

| Supportive care | • Health insurance counseling | Consults/Referrals |

| • Financial assistance programs to address medical | • Oncology social worker | |

| expenses and practical needs (transportation, child care, housing) |

• Patient navigator | |

| • Educational and/or vocational counseling or support services |

• Financial counselor | |

| Financial assistance programs | ||

| • Governmental/public assistance programs or | ||

| disability benefits (Medicaid, Supplemental Security | ||

| Income, Social Security Disability Insurance) | ||

| • Nonprofit or philanthropic organizations (The | ||

| SamFund grants, www.thesamfund.org) | ||

| Educational and vocational programs | ||

| • Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, a federal-state | ||

| program that provides job training, career | ||

| counseling, employment services, and/or college | ||

| assistance for individuals with disabilities, including | ||

| cancer | ||

| • College or university disability programs for | ||

| educational support and accommodations | ||

| • Cancer and Careers (www.cancerandcareers.org), | ||

| online employment information and resources | ||

| Coping and | • Financial self-efficacy or self-management strategies | Consults/Referrals |

| adaptation | • Cognitive-behavioral strategies to manage financial | • Financial counselor |

| distress | • Psychosocial provider | |

| • Peer or social support | Strategies | |

| • Meditation, mindfulness, and other stress management strategies |

||

| Online support programs | ||

| • Stupid Cancer (stupidcancer.org) | ||

| • CancerCare (www.cancercare.org) | ||

| • Imerman Angels (https://imermanangels.org) | ||

| • LIVESTRONG (https://livestrong.org) |

Improved patient-provider communication is essential to educate patients with cancer about the costs of cancer treatment.31,42 The American Society of Clinical Oncology Cost of Cancer Care Task Force framework statement60 identified the need for shared decision making about the cost of cancer care and the benefit of provider- and patient-centered educational tools to foster effective communication about costs and various treatment options. Tucker-Seeley and Yabroff have noted that oncologist communication and patient health literacy are key components of any intervention designed to reduce the financial hardship of cancer care for families.18 Financial education toolkits (Table 3) help to improve financial health literacy and empower AYAs to initiate conversations with their oncology provider about the costs of cancer care and make informed decisions about treatment options, management of finances, and associated lifestyle changes.

Referrals to developmentally appropriate supportive care resources and services during and after treatment have been recommended as a critical element for improving the quality of life and quality of cancer care for AYAs (Table 3).61 All AYA patients with cancer should see an oncology social worker, patient navigator, and/or financial counselor to assist them with obtaining and securing health care insurance, especially at diagnosis and transition to survivorship care. However, health insurance may not be enough to reduce their financial burden due to increasing treatment-related out-of-pocket expenses such as high insurance copays, co-insurances, and deductibles.14 AYAs should also be made aware of financial assistance programs and resources to address their medical expenses and practical needs. Qualitative findings from a study that investigated patient-navigator needs and preferences for AYA patients with cancer during and after treatment highlighted the need for health insurance, child care, and financial support. Differences emerged among the developmental subgroups: adolescents (15–18 years) were interested in educational assistance and information about how health insurance works; emerging adults (19–25 years) and young adults (26–39 years) wanted a review of medical bills, detailed information about health insurance payments, and financial assistance for living expenses; and young adults additionally wanted financial assistance for treatment-related expenses.62 A novel pilot feasibility study of a financial navigation program has been reported recently to reduce anxiety about the costs of cancer care in older adult patients with cancer,63 which could have relevance for AYAs. Educational and vocational counseling services and programs are also important to address interruptions in college or employment/career, which have both a direct and indirect impact on financial burden for AYAs with cancer.14 Importantly, the NCCN has recommended that these financial assistance resources and programs be included in all AYA survivorship care plans.47

The financial impact of excessive cancer treatment costs may not be completely resolved through financial assistance programs and resources. Interventions that target coping or self-management strategies (Table 3) may have complementary and more durable value. Such interventions may focus on teaching or strengthening cognitive-behavioral strategies that build AYA confidence in managing financial problems related to cancer treatment and cope with financially-related stressors (financial self-efficacy). Self-management strategies may also enhance AYAs’ ability to seek social or peer support, which has a heightened importance for this age group64,65 and may serve to buffer the impact of financial toxicity. Research is needed to develop interventions for reducing cancer-related financial toxicity in AYAs at various life stages.

On a systems level, long-term solutions for improvement of financial toxicity for all patients with cancer in the United States may lie in health care policy changes targeting increasing pharmaceutical and out-of-pocket health insurance costs.31 Drug costs for patients are disproportionately high in developing nations.66 The World Health Organization has championed the concept of universal health coverage, defined as all people and communities being able to use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health services they need without creating financial hardship for themselves.67 Although this approach would address many cost-related access barriers facing AYAs, significant economic and political challenges make its widespread adoption unlikely in the near term.

6 |. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

As part of a growing emphasis on long-term health outcomes after cancer, financial toxicity is receiving increased attention in AYA oncology. In the clinical setting, providers of all types—including physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and care navigators—need to be cognizant of the financial impact of cancer. Although addressing this issue represents standard of care in pediatric oncology, financial hardship and risk are more complex among AYAs due to their highly variable insurance coverage and changing needs across the age spectrum. Much of the currently available research concerning the financial impact of AYA cancer involves self-reported or registry-based data. Prospective research is needed to define accurately and longitudinally the changing financial effects of cancer in AYAs, coupled with increased attention to the development of psychometrically robust, developmentally appropriate, multidimensional measures and grading scales that account for both the patient and family perspective.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

Funding for this study was provided, in whole or in part, by National Cancer Institute (R01CA218398–01,John M.Salsman; U10 CA098543, David R. Freyer) and the Children’s OncologyGroup/Aflac Foundation (David R. Freyer).

Abbreviations:

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- AYA

adolescent and young adult

- CSAQ

Cancer Self-Administered Questionnaire

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- PRO

patient-reported outcome

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, LIVESTRONG™ Young Adult Alliance. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. 2006. http://planning.cancer.gov/library/AYA0_PRG_Report_2006_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 6,2008.

- 2.White PH. Access to health care: health insurance considerations for young adults with special health care needs/disabilities. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2008: with special feature on the health of young adults. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics (US) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodean J Health insurance coverage of young adults aged 19 to 25: 2008, 2009, and 2011. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommers BD. Number of young adults gaining insurance due to the Affordable Care Act nowtops 3 million. ASPE Issue Brief; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, Doty MM. Young, uninsured, and in debt: why young adults lack health insurance and how the Affordable Care Act is helping. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;14:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commonwealth Fund. Health care coverage and access in your state. October 2, 2018. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/health-care-coverage-and-access-your-state.

- 8.Parsons HM, Schmidt S, Tenner LL, Bang H, Keegan TH. Early impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Acton insurance among young adults with cancer: analysis of the dependent insurance provision. Cancer. 2016;122:1766–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez EM, Keegan TH, Johnston EE, et al. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act dependent coverage expansion: disparities in impact among young adult oncology patients. Cancer. 2018;124:110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):S619–S631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr R, Furlong W, Horsman J, Feeny D, Torrance G, Weitzman S. The monetary costs of childhood cancer to the families of patients. Int J Oncol. 1996;8:933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy GP Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landwehr MS, Watson SE, Macpherson CF, Novak KA, Johnson RH. The cost of cancer: a retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Med. 2016;5:863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ financial toxicity and cancer treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Updated December 13, 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-hp-pdq. Accessed December 15,2018. [PMID: 27583328]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartley M Health Inequality: An Introduction to Concepts, Theories and Methods. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17 https://www.afcpe.org/assets/pdf/vol1714.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker-Seeley RD, Marshall G, Yang F. Hardship among older adults in the HRS: exploring measurement differences across socio-demographic characteristics. RaceSoc Probl. 2016;8:222–230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122:283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrumentfor use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123:476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, et al. Determinants and consequences of financial hardship among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018. 10.1093/jnci/djy120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khera N. Reporting and grading financial toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3337–3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: (CTCAE) Version 5.0. 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5×11.pdf.

- 31.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Kang T, et al. Psychological distress in parents of children with advanced cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:537–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith AW, Seibel NL, Lewis DR, et al. Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: an update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer. 2016;122:988–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AW, Parsons HM, Kent EE, et al. Unmet support service needs and health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer: the AYA HOPE study. Front Oncol. 2013;3:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker KS, Ambrose K, Arvey SR, et al. Financial and work related impact of cancer in young adult (YA) survivors. Paper presented at ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. JClin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keegan TH, Tao L, DeRouen MC, et al. Medical care in adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: what are the biggest access-related barriers? J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirchhoff AC, Lyles CR, Fluchel M, Wright J, LeisenringW. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5964–5972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg AR, Kroon L, Chen L, Li CI, Jones B. Insurance status and risk of cancer mortality among adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2015;121:1279–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aizer AA, Falit B, Mendu ML, et al. Cancer-specific outcomes among young adults without health insurance. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2025–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robbins AS, Lerro CC, Barr RD. Insurance status and distant-stage disease at diagnosis among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer aged 15 to 39 years: National Cancer Data Base, 2004 through 2010. Cancer. 2014;120:1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butow P, Palmer S, Pai A, Goodenough B, Luckett T, King M. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4800–4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes N, Stark D. The management of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;67:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul S, Avila JC, Mehta HB, Rodriguez AM, Kuo YF, Kirchhoff AC. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123:2726–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, Version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:66–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hard-ships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bona K, London WB, Guo D, Frank DA, Wolfe J. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salsman J, Snyder M,Zebrack B, Reeve B, Chen E. Measuring quality of life in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: a PROMISing solution? Ann BehavMed. 2016;50(Suppl 1):1–335. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Bogue MK, et al. The Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life instrument: reliability and validity of the Adolescent Form. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4692–4698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Wu E, et al. The Minneapolis-ManchesterQuality of Life instrument: reliability and validity of the Youth Form. J Pediatr. 2004;145:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). EORTC quality of life questionnaires: adolescents and young adults. https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/aya/. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 55.Salsman JM. Optimizing health related quality of life measurement in adolescent and young adult oncology: a promising solution. https://maps.cancer.gov/overview/DCCPSGrants/abstract.jsp?applId=9507780&term=CA218398. Accessed December 15, 2018. 5R01CA218398.

- 56.Kent EE, Parry C, Montoya MJ, Sender LS, Morris RA, Anton-Culver H. “You’re too young for this”: adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:260–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy MC, McNeil R, Drew S, Orme L, Sawyer SM. Information needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and their parent-carers. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1655–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Francoeur RB. Reformulating financial problems and interventions to improve psychosocial and functional outcomes in cancer patients and their families. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2001;19:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zebrack B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S. Quality cancer care for adolescents and young adults: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4862–4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pannier ST, Warner EL, Fowler B, Fair D, Salmon SK, Kirchhoff AC. Age-specific patient navigation preferences among adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2017. 10.1007/s13187-017-1294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:2329–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Warner EL, Kent EE, Trevino KM, Parsons HM, Zebrack BJ, Kirchhoff AC. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2016;122:1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldstein DA, Clark J, Tu Y, et al. A global comparison of the cost of patented cancer drugs in relation to global differences in wealth. Onco- target. 2017;8:71548–71555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization. Universal health coverage and health financing. 2018. https://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/.

- 68.de Souza JA, Wong Y-N. Financial distress in cancer patients. JMed Person. 2013;11 10.1007/s12682-013-0152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Oncologist. 2015;20:1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barbaret C, Brosse C, Rhondali W, et al. Financial distress in patients with advanced cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gordon LG, Walker SM, Mervin MC, et al. Financial toxicity: a potential side effect of prostate cancer treatment among Australian men. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26 10.1111/ecc.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient attitudes regarding the cost of illness in cancer care. Oncologist. 2015;20:1199–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marshall GL, Tucker-Seeley R. The association between hardship and self-rated health: does the choice of indicator matter? Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]