Abstract

Background

The extensive phenotypic heterogeneity of monogenic diseases can be largely traced to intragenic variation; however, recent advances in clinical detection and gene sequencing have uncovered the emerging role of non-allelic variation (i.e. genetic trans-modifiers) in shaping disease phenotypes. Identifying these associations are not only of significant diagnostic value, but also scientific insight into the expanded molecular etiology of rare diseases. This reports describes the discordant clinical manifestation of a family segregating mutations in ABCA4 and PROM1.

Methods

Three patients across a two generation family underwent multimodal imaging and functional testing of the retina including color photography, fundus autofluorescence (AF), spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and full-field electroretinography (ffERG). Genetic characterization was carried out by direct Sanger and whole exome sequencing.

Results

Clinical examination revealed similar retinal degenerative phenotypes in the proband and her mother. Despite being younger, the proband’s phenotype was more advanced and exhibited additional features related to Stargardt disease not found in the mother. Whole exome sequencing identified a pathogenic missense variant in PROM1, c.400C>T, p.(Arg134Cys), as the underlying cause of retinal disease in both the proband and mother. Sequencing of the ABCA4 locus uncovered a single disease-causing variant, c.5714+5G>A in the daughter segregating from the father who, surprisingly, also exhibited very subtle disease changes associated with STGD1 despite being a heterozygous carrier.

Conclusions

Harboring an additional heterozygous ABCA4 mutation increases severity and confers STGD1-like features in patients with PROM1 disease which provides supporting evidence for their shared pathophysiology and potential treatment prospects.

Keywords: PROM1, ABCA4, modifier, cone-rod dystrophy, family

Introduction

Individual monogenic disorders are relatively rare occurrences although together they comprise a substantial fraction of disease in the general population (RetNet, https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/; accessed May 2019). Genotype-phenotype correlations are fundamental to the practice of precision genomic medicine; however, the vast number of disease-associated genes and even more extensive spectrum of respective phenotypes have created longstanding challenges for both clinicians and scientists. Moreover, phenotypic variability can be further shaped by the presence of non-allelic variation (i.e. genetic trans-modifiers) that can alter diagnostic features or influence the severity of the underlying condition.(1) Identifying putative genetic modifiers of a disease broadens our understanding of its pathophysiology, treatment prospects and management of patients in the clinic.

This report describes the variable phenotypic manifestation of a patient and her mother who are affected by dominant maculopathy. The daughter’s phenotype was significantly more advanced and exhibited additional features pathognomonic to Stargardt disease (STGD1, MIM# 248200) not found in the mother. Sequencing of ABCA4 in the family uncovered only a single known disease-causing variant in the daughter, c.5714+5G>A,(2) which segregated from her father who, surprisingly also exhibited very subtle disease changes associated with STGD1. Subsequent whole exome sequencing identified a novel variant in PROM1 (MIM# 604365) as the primary underlying cause of maculopathy in both the mother and daughter; however, the daughter’s phenotype is consequently modified and augmented by the heterozygous ABCA4 variant. This case illustrates the manner and degree to which a single ABCA4 allele can influence the phenotype of PROM1 macular dystrophy and furthers our understanding their shared pathophysiology.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Clinical Examination

Each study subject was consented before participating in the study under the institutional review board protocol #AAAI9906 approved by the institutional review board at Columbia University (New York, NY, USA). The study adhered to tenets set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient underwent a complete ophthalmic examination, including slit-lamp and dilated fundus examinations. Vision was assessed by the measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA; Snellen), while further structural assessments were made on color fundus photographs taken with a FF450plus Fundus Camera (Carl Zeiss Meditec). Autofluorescence (AF) images and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans were acquired with a Spectralis HRA+OCT (Heidelberg Engineering) and full-field electroretinogram (ffERG) was recorded a Diagnosys Espion Electrophysiology System (Diagnosys) in accordance with standard techniques recommended by the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV).(3)

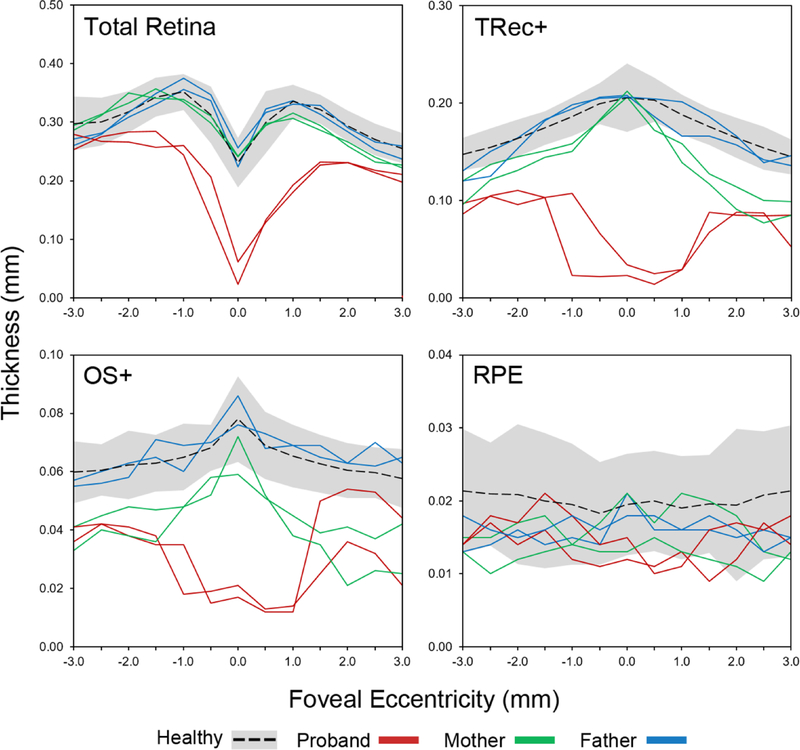

Retinal Thickness Analysis

The thickness of the total retina, total receptor+ (TREC+), outer segment+ (OS+) and RPE layers were manually measured using the caliper tool in the HEYEX software (Heidelberg Engineering) in both eyes each of family member and compared to the mean ± 2 standard deviations (SD) of 25 eyes of 25 healthy subjects (mean age, 47.5 years; range, 13.5–84.4 years). TREC+ is defined as the distance between Bruch’s membrane (BM) to the border of the outer plexiform/inner nuclear layer; OS+ is defined as the distance between BM and the ellipsoid zone. Measurements were carried out on horizontal SD-OCT scans (high-resolution, 9mm) at 0.5 mm intervals up to 3 mm along the the nasal and temporal axes (17 positions total).

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood lymphocytes. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and variant calling were performed at the Columbia Institute for Genomic Medicine (IGM). Exome sequence was captured using SeqCap EZ Exome v3. Raw sequence data was quality-filtered with CASAVA (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA), and aligned to Human Reference Genome build hg19; duplicates were removed with Dynamic Read Analysis for Genomics (Edico Genome, San Diego, CA) and variant calling was done according to best practices outlines in Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK v3.6) with variant selection using Variant quality Score Recalibration using HapMap v3.3, dbSNP, and 1000 genomes. Proband was sequenced to a mean coverage of 78X. To find possible disease causing variants, the variants were filtered by allele frequency with the gnomAD database (MAF ≤ 0.005), pathogenicity (known, or PolyPhen not benign), and consequence (missense, frameshift, splice donor/acceptor variants, and stop loss/gain), resulting in 946 variants. These variants were further filtered for genes associated with retinal disease (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/). All identified variants were analyzed using Alamut software version 2.2 (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France). Functional annotation of variants was carried out with ANNOVAR(4) using pathogenicity scores of MCAP,(5) REVEL,(6) Eigen,(7) CADD(8) and DANN.(9) As a general guideline, pathogenic consequences are predicted for variants with scores over 0.025 for MCAP, 0.5 for REVEL, 0.5 for Eigen, 20 for CADD and 0.97 for DANN.

Results

Clinical Findings

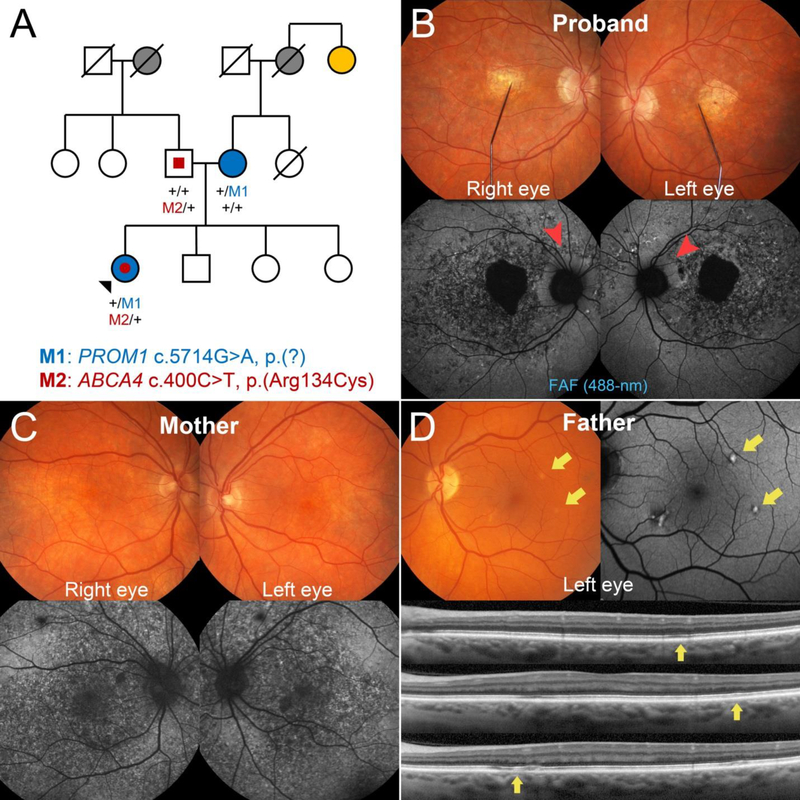

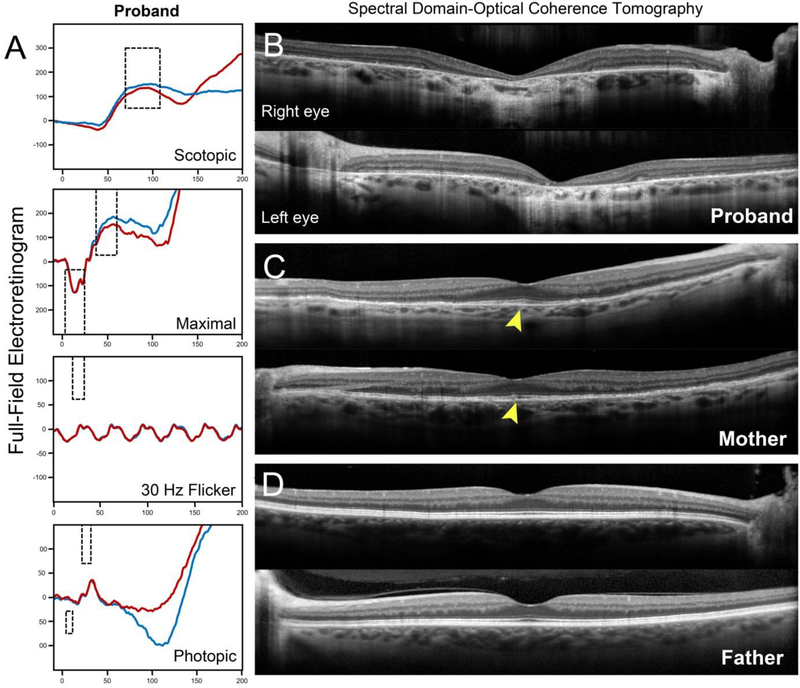

A 34-year-old Caucasian woman of German (paternal) and Czech-Hungarian (maternal) descent presented to the clinic with a referring diagnosis of retinal degeneration. The patient reported noticing symptoms of central vision loss within the last decade and was recently diagnosed with Stargardt disease. Systemic history was unremarkable with the exception of episodic herpes simplex virus. A bi-parental history of glaucoma as well as AMD and pattern dystrophy on the maternal side was noted (Figure 1A). Visual acuity was 20/200 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye after correcting for moderate refractive error (−6.5 −0.25 × 50 right eye; −6.25 −0.25 × 190 left eye). Intro-ocular pressures (IOP) were 12 mmHg and optic cup-to-disk ratios 0.2 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable. Dilated fundus examination found granular mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and well-delineated lesions of chorioretinal atrophy in both eyes (Figure 1B). Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging confirmed the presence of bright granular deposition corresponding to the RPE mottling observed on fundoscopy. Peripapillary sparing of disease changes around the optic nerve, a pathognomonic feature of ABCA4,(10) was noted in both eyes (Figure 1B, red arrowheads). Full-field electroretinogram (ffERG) testing revealed normal rod function. Decreases in 30 Hz flicker and single flash cone response amplitudes indicate generalized dysfunction of cones across the retina (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Pedigree and retinal imaging of the disease phenotypes segregating in a family harboring disease-causing mutations in PROM1 and ABCA4. (A) Three generation pedigree denoting the presence of ocular disease and reported histories are shown including glaucoma (gray-filled), age-related macular degeneration (yellow-filled), macular dystrophy (blue-filled) and ABCA4-related features (red-filled). Represented PROM1 (top) and ABCA4 (bottom) genotypes are provided for the proband (black arrowhead) and her father and mother. M1 and M2 denote the PROM1 and ABCA4 variants while “+” denotes a wild-type allele. Squares are men, circles are women and diagonal lines denote a deceased individual. (B) Fundus photograph with fixation needle and corresponding fundus autofluorescence (FAF) images illustrating RPE mottling, severe chorioretinal atrophy and disease-sparing of the peripapillary regions (red arrowheads) in the 34-year-old patient (proband) harboring both heterozygous PROM1 and ABCA4 mutations. (C) The affected mother, who harbors the PROM1 mutation, exhibits only a maculopathy associated with the RPE mottling phenotype. (D) Distinct autofluorescent, pisciform flecks were found in the left eye of the father from whom the ABCA4 mutation segregated. Each fleck corresponded to faint, intermittent disruption of the RPE and EZ bands (yellow arrows) on spectral domain-optical coherence tomography.

Figure 2:

(A) Full-field electroretinogram testing results of the proband revealed normal rod dysfunction. Decreases in 30 Hz flicker and single flash cone cone amplitudes indicate generalized dysfunction of cones across the retina in the right (blue trace) and left (red trace) eyes. Macular spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans through the fovea in the proband, affected mother and father. (B) Chorioretinal atrophy in the central macula of the proband is indicated by severe retinal thinning and hypertransmission of the SD-OCT signal into the choroid. (C) Diffuse loss of outer retinal layers is visible in the affected mother, however, relative sparing at the fovea can be observed (yellow arrowheads). (D) No disease changes are apparent in foveal scans of the father.

Examination of the 64-year-old mother confirmed the presence of retinal disease (Figure 1C). Both eyes were mildly hyperopic (+2.5 −0.5 × 50 right eye; +3.0 −0.5 × 150 left eye) with normal IOP. She reported no significant history of central vision loss but noted reduced visual sensitivity at night. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in both eyes which was consistent with spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) findings that showed sparing of the outer retinal layers in the fovea in both eyes (Figure 2). Regions of diffuse “paving-stone” degeneration was observed bilaterally in the far periphery. FAF imaging revealed an identical pattern of granular deposition observed in the daughter. Despite being older, the disease phenotype of the mother was markedly less advanced than the daughter and notably, she did not exhibit peripapillary sparing. No generalized cone or rod dysfunction was noted on ffERG testing. Although the father was also reportedly unaffected and BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes, several distinct pisciform-shaped flecks around the parafoveal macula were unexpectedly discovered upon examination (Figure 1D). The flecks were autofluorescent on FAF imaging and corresponded to intermittent irregularities of the RPE and ellipsoid zone bands on SD-OCT. A comparison of disease features in all three cases is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics in a Family Segregating PROM1 and ABCA4 Mutations

| Patient | Clinical Features | ABCA4-associated disease features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macular RPE mottling | Chorioretinal atrophy | Foveal sparing | ffERG | Pisciform flecks | Peripapillary sparing | |

| Proband | + | + | − | Decreased | N/A | + |

| Mother | + | − | + | Normal | N/A | − |

| Father | − | − | − | N/A | + | N/A |

Thickness of the retina and outer retinal layers were assessed on horizontal SD-OCT scans in the family and compared to respective thicknesses ± 2 SD of healthy individuals/eyes (n = 25) (Figure 3). While the father’s retinal layers were relatively normal, the mother exhibited moderate and uniform thinning of the photoreceptor-attributable layers, TREC+ and OS+. The proband exhibited further generalized thinning throughout all retinal layers, particularly across regions of the central macula corresponding to chorioretinal atrophy.

Figure 3:

Assessment of total retinal, total receptor+ (TREC+), outer segment+ (OS+) and RPE thickness along horizontal spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT)scans of both eyes in the proband (red), affected mother (green) and father (blue) as compared to 25 healthy individuals/eyes. Black dotted lines are the mean thickness values of healthy eyes ± 2 standard deviations represented by the gray shaded area. Thicknesses were plot as a function of eccentricity from the fovea, 3 mm in the nasal (+values) and temporal (-values) directions. TREC+ is defined as the distance between Bruch’s membrane (BM) to the border of the outer plexiform/inner nuclear layer; OS+ is defined as the distance between BM and the anterior boundary of the ellipsoid zone band.

Genetic Analysis

No pathogenic variants were found in the mother after sequencing of the PRPH2 gene. A known variant (ENST00000370225*, c.5714+5G>A. p.(?); rs61751407), previously associated with skipping of exon 40,(2) segregating from the father was found in the proband following sequencing of the ABCA4 locus (Figure 1A). Copy number variant (CNV) analysis of ABCA4 did not reveal further variation explaining the disease. Whole exome sequencing in the mother identified 946 variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of ≤0.005. Within this group, 18 heterozygous variants were in genes associated with retinal disease (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/) (Table 2). A variant (4:16035036G>A, ENST00000510224*, c.400C>T, p.(Arg134Cys); rs768526003) in exon 4 of the PROM1 gene was found segregating in both the proband and mother (Figure 1). The variant is very rare in the general population with the minor allele frequency of 0.00002009 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/4–16035036-G-A; accessed May 2019). The variant was unanimously predicted to be likely pathogenic: M-CAP = 0.142, REVEL = 0.770, Eigen = 0.877, DANN = 1.00 and CADD13 = 35.0. No other variant had a consensus prediction of pathogenicity and/or clinically fit the phenotype of the mother and proband.

Table 2:

Genetic and functional summary of rare variants in genes associated with retinal disease identified from whole exome sequencing in the affected mother of the proband.

| Gene | Genomic location | HGVS cDNA | HGNS protein | Variant type | Variant effect | RefSNP | MAF | M-CAP | REVEL | Eigen | DANN | CADD13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALMS1 | Chr 2:73679765 | c.6108G>T | p.Lys2036Asn | Substitution | missense | - | - | 0.008 | 0.048 | −0.145 | 1.00 | 25.1 |

| CEP19 | Chr 3:196434746 | c.63G>A | p.Pro21Pro | Substitution | synonymous | rs116167439 | 8.73E-03 | - | - | 0.537 | 0.85 | 12.3 |

| PROM1 | Chr 4:16035036 | c.400C>T | p.Arg134Cys | Substitution | missense | rs768526003 | 2.01E-05 | 0.142 | 0.770 | 0.877 | 1.00 | 35.0 |

| EYS | Chr 6:64694397 | c.6934C>A | p.Leu2312Ile | Substitution | missense | rs564315274 | - | 0.124 | 0.247 | −0.139 | 0.99 | 20.3 |

| PEX7 | Chr 6:137151137 | c.340–8T>G | p.? | Substitution | splice region | - | - | - | - | −0.217 | 0.41 | - |

| RP9 | Chr 7:33134847 | c.664delT | p.Ter222fs | Deletion | frameshift | rs553265417 | 7.39E-03 | - | - | - | - | - |

| OPN1SW | Chr 7:128415506 | c.339G>C | p.Leu113Leu | Substitution | synonymous | rs755460627 | 1.42E-05 | - | - | 0.933 | 0.60 | - |

| INVS | Chr 9:102866809 | c.6C>G | p.Asn2Lys | Substitution | missense | - | - | 0.010 | 0.069 | −0.930 | 0.96 | 13.6 |

| INVS | Chr 9:102866833 | c.30T>C | p.Ala10Ala | Substitution | synonymous | - | - | - | - | 0.814 | 0.58 | - |

| PCDH15 | Chr 10:55566702 | c.4692G>A | p.Thr1564Thr | Substitution | synonymous | rs148772706 | 2.58E-03 | - | - | −0.684 | 0.32 | - |

| PCDH15 | Chr 10:55663054 | c.3450C>A | p.Ile1150Ile | Substitution | synonymous | rs146374856 | 4.67E-04 | - | - | 1.234 | 0.76 | 13.0 |

| PDE6C | Chr 10:95400694 | c.1755G>T | p.Lys585Asn | Substitution | missense | rs45522236 | 6.40E-03 | - | 0.374 | −0.149 | 1.00 | 25.7 |

| ROM1 | Chr 11:62381825 | c.686G>A | p.Arg229His | Substitution | missense | rs150168119 | 3.72E-03 | - | 0.185 | −0.837 | 0.99 | 10.7 |

| CEP164 | Chr 11:117280526 | c.3941A>C | p.Tyr1314Ser | Substitution | missense | rs746926558 | 4.22E-04 | 0.060 | 0.087 | −0.897 | 0.46 | - |

| TTC8 | Chr 14:89337945 | c.1150C>T | p.Leu384Leu | Substitution | synonymous | - | 3.98E-06 | - | 0.103 | 0.403 | 0.75 | 13.7 |

| CDH3 | Chr 16:68712772 | c.654C>T | p.Asp218Asp | Substitution | synonymous | rs763136509 | 4.60E-05 | - | - | 0.370 | 0.50 | 12.1 |

| PITPNM3 | Chr 17:6381945 | c.699C>T | p.Val233Val | Substitution | synonymous | rs149964592 | 7.53E-03 | - | - | −0.291 | 0.75 | - |

| CA4 | Chr 17:58234045 | c.237A>C | p.Gln79His | Substitution | missense | - | - | 0.022 | 0.089 | −1.395 | 0.81 | - |

Prediction scores highlighted in red are above the pathogenicity threshold: >0.025 for MCAP, >0.5 for REVEL, >0.5 for Eigen, >20 for CADD and >0.97 for DANN.

Abbreviations: HGVS, human genome variation society; RefSNP, reference SNPs; MAF, minor allele frequency (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

Discussion

The pathogenic effect of ABCA4 alleles beyond the context of STGD1(11) has long been a topic of fervent investigation. ABCA4 encodes a photoreceptor-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter responsible for “flipping” N-retinyl-phosphatidylethanolamine across the outer segment disc membrane following its production during phototransduction. Dysfunction of this process results in accumulation of phototoxic bisretinoids of lipofuscin, including A2E, in the RPE which is the primary effector of retinal degeneration in STGD1.(12) Although the cellular role of ABCA4 appears to be functionally autonomous, accumulation of lipofuscin does occur in RPE over time in otherwise healthy individuals leading to speculation that bisretinoid toxicity may contribute to the pathophysiology of other conditions, particularly age-related diseases. Indeed, the presence of certain heterozygous ABCA4 variants have been statistically associated with an increased risk of AMD.(13–18) The effect of ABCA4 alleles, including common synonymous variants, on susceptibility to chloroquine- or hydroxychloroquine-induced retinopathy, a condition that shares both mechanistic and, at times, phenotypic overlap with STGD1,(19) have also been investigated although results remain contradictory.(20, 21)

The precise physiological role of PROM1 in the retina remains unknown. The PROM1 protein is localized to photoreceptor outer segments and complete loss of its function in Prom1−/−mice results in disrupted disc morphogenesis.(22, 23) The spectrum of PROM1-associated retinopathy ranges from autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa to varying dominant maculopathies including STGD1-like phenotypes: cone-rod dystrophy 12 (MIM# 612657), macular dystrophy 2 (MIM# 608051) and STGD4 (MIM# 603786). More important, however, is the finding that Prom1−/− mice also exhibit significant downregulation of Rdh12 and Abca4, both of which are directly responsible for the reduction of vitamin A-derived all-trans-retinol. Accumulation of A2E/lipofuscin may thus be a downstream event of PROM1 deficiency and the additive effect of a highly deleterious ABCA4 mutation, could result in a more severe and STGD1-like phenotype as observed in the presented patient (RPE mottling, significant retinal thinning, peripapillary sparing and chorioretinal atrophy) compared to her mother (RPE mottling only).

Unequivocally attributing the STGD1-like flecks in the fundus of the father (Figure 1) to the ABCA4 mutation he harbors is beyond the scope of this study. Moderate A2E/lipofuscin accumulation in heterozygous Abca4+/− mice along with disease changes in the outer retina have been observed.(24–26) Surprisingly, however, neither increased lipofuscin (488-nm) nor significant retinal disease (with the exception of similarly-appearing flecks in a few individuals) could be clinically detected in a large cohort of heterozygous parents and siblings of affected patients harboring known disease-causing ABCA4 mutations.(27) This case therefore reaffirms that monoallelic variation in ABCA4 is not sufficient for disease, however, certain mutations may cause mild, late-onset manifestations of STGD1 sub-phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Eye Institute/NIH EY028203 and EY019007 (Core Support for Vision Research), NY Community Trust – Frederick J. and Theresa Dow Wallace Fund and unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of the paper.

References

- 1.Meyer KJ, Anderson MG. Genetic modifiers as relevant biological variables of eye disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(R1):R58–R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sangermano R, Khan M, Cornelis SS, Richelle V, Albert S, Garanto A, et al. ABCA4 midigenes reveal the full splice spectrum of all reported noncanonical splice site variants in Stargardt disease. Genome Res. 2018;28(1):100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCulloch DL, Marmor MF, Brigell MG, Hamilton R, Holder GE, Tzekov R, et al. ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2015;130(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, Guturu H, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48(12):1581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, et al. REVEL: An Ensemble Method for Predicting the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense Variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(4):877–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ionita-Laza I, McCallum K, Xu B, Buxbaum JD. A spectral approach integrating functional genomic annotations for coding and noncoding variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):310–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quang D, Chen Y, Xie X. DANN: a deep learning approach for annotating the pathogenicity of genetic variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(5):761–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, Sumaroka A, Schwartz SB, Roman MI, et al. ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations spare structure and function of the human parapapillary retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allikmets R, Singh N, Sun H, Shroyer NF, Hutchinson A, Chidambaram A, et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;15(3):236–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K, Blonska A, Ghosh SK, Ueda K, et al. The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31(2):121–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone EM, Webster AR, Vandenburgh K, Streb LM, Hockey RR, Lotery AJ, et al. Allelic variation in ABCR associated with Stargardt disease but not age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 1998;20(4):328–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera A, White K, Stohr H, Steiner K, Hemmrich N, Grimm T, et al. A comprehensive survey of sequence variation in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene in Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(4):800–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allikmets R. Further evidence for an association of ABCR alleles with age-related macular degeneration. The International ABCR Screening Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(2):487–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritsche LG, Igl W, Bailey JN, Grassmann F, Sengupta S, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):134–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allikmets R, Shroyer NF, Singh N, Seddon JM, Lewis RA, Bernstein PS, et al. Mutation of the Stargardt disease gene (ABCR) in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 1997;277(5333):1805–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritsche LG, Fleckenstein M, Fiebig BS, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Bindewald-Wittich A, Keilhauer CN, et al. A subgroup of age-related macular degeneration is associated with mono-allelic sequence variants in the ABCA4 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):2112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noupuu K, Lee W, Zernant J, Greenstein VC, Tsang S, Allikmets R. Recessive Stargardt disease phenocopying hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(5):865–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shroyer NF, Lewis RA, Lupski JR. Analysis of the ABCR (ABCA4) gene in 4-aminoquinoline retinopathy: is retinal toxicity by chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine related to Stargardt disease? Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(6):761–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grassmann F, Bergholz R, Mandl J, Jagle H, Ruether K, Weber BH. Common synonymous variants in ABCA4 are protective for chloroquine induced maculopathy (toxic maculopathy). BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zacchigna S, Oh H, Wilsch-Brauninger M, Missol-Kolka E, Jaszai J, Jansen S, et al. Loss of the cholesterol-binding protein prominin-1/CD133 causes disk dysmorphogenesis and photoreceptor degeneration. J Neurosci. 2009;29(7):2297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z, Chen Y, Lillo C, Chien J, Yu Z, Michaelides M, et al. Mutant prominin 1 found in patients with macular degeneration disrupts photoreceptor disk morphogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(8):2908–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sparrow JR, Blonska A, Flynn E, Duncker T, Greenberg JP, Secondi R, et al. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in mice: correlation with HPLC quantitation of RPE lipofuscin and measurement of retina outer nuclear layer thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(4):2812–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu L, Nagasaki T, Sparrow JR. Photoreceptor cell degeneration in Abcr (−/−) mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:533–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mata NL, Tzekov RT, Liu X, Weng J, Birch DG, Travis GH. Delayed dark-adaptation and lipofuscin accumulation in abcr+/− mice: implications for involvement of ABCR in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(8):1685–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncker T, Stein GE, Lee W, Tsang SH, Zernant J, Bearelly S, et al. Quantitative Fundus Autofluorescence and Optical Coherence Tomography in ABCA4 Carriers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(12):7274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]