Abstract

Objectives

China’s recent demographic and social changes might undermine the sustainability of its family-oriented system for elder care. We investigate kin availability among adults aged 45+ in contemporary China, with an emphasis on child gender.

Method

Using nationally representative survey data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (2011), we examine the prevalence and correlates of lacking different kin types and combinations, and we test associations between kin availability and received economic support.

Results

Kinlessness is low in China (less than 2% lack a spouse/partner and children), but kin availability is patterned by gender, age group, and sociodemographic characteristics. More than twice as many older adults have no spouse/partner and no daughter (3.2%) as those who have no spouse/partner and no son (1.4%). Adults without close kin are disadvantaged across health, wealth, and economic support. In contrast to traditional expectations, we find that those with only daughters are more similar to those with mixed sex children, whereas those with only sons are more similar to those without children in receipt of economic support.

Discussion

Access to kin forms the basis of an emergent system of stratification in China, which will be amplified as cohorts with only one child age into older adulthood.

Keywords: Gender, Kinship, Social Network, Social Support

Kin are important sources of social support for older adults. Having kin is strongly associated with the psychological and physical components of healthy aging (Berkman, 1984; Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). Kin are also the primary providers of financial and instrumental assistance that helps aging adults cope with negative life events (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Uchino, 2004). There is a large body of research on social support from living kin, but only recently have researchers begun to examine those without living kin, a population referred to as “the kinless” or “elder orphans” (Carney, Fujiwara, Emmert, Liberman, & Paris, 2016; Margolis & Verdery, 2017; Verdery & Margolis, 2017). To date, research on kinlessness has primarily focused on the United States, where kinless older adults are vulnerable in terms of health and wealth, and increasing in both numbers and percentages of the older adult population, especially among disadvantaged groups. In this article, we explore kin availability in a different and rapidly changing context: China.

The People’s Republic of China contains approximately one quarter of all older adults in the world; it currently has 524.9 million adults at least 45 years old in China out of 2.1 billion globally (United Nations Population Division, 2015). In the coming decades, China is expected to contribute hundreds of millions more older adults to the global aging population (Zeng & Hesketh, 2016; Zeng & Wang, 2014) before its aging population peaks in 2040 (United Nations Population Division, 2015). Besides size, there are other important reasons to study those lacking kin in contemporary China. First, the country has undergone remarkable demographic changes in mortality, fertility, marriage, and migration over the last several decades (Peng, 2011). These changes are causing rapid population aging, shifting the numbers of kin available to its current and future older adults (Verdery, 2017). Second, China’s economy is growing dramatically (Wang & Yao, 2003). Gross-national income per capita increased 10-fold between the 1960s and the 1990s, then increased 10-fold again from 1999 to 2016, bringing nearly 750 million individuals out of poverty (World Bank, 2016). Starting in 1997, a series of substantial pension reforms in China increased coverage of the older adult population; however, coverage remains incomplete, particularly in rural areas (Salditt, Whiteford, & Adema, 2008). Likewise, estimates suggest that the “demographic window” during which China could address its pension problems expires in the present decade (Feng et al., 2011; Salditt et al., 2008). Third, Chinese society has long been, and remains, organized around family life (Li & Chen, 2014; Tao, 1913). In China, children are obligated to support their aging parents, both normatively and legally, and many older adults rely extensively on family support (Salditt et al., 2008). However, there are substantial differences in expectations of support from sons and daughters (Ikels, 1990, 1993; Gui & Ni, 1995), although some evidence suggests that current reality may differ from traditional expectations (Xie & Zhu, 2009). Given the demographic, economic, and social changes in China’s recent history and the importance of the family in this context, it is important to understand how those without family fare.

In this article, we first examine the prevalence of lacking different types and combinations of living close kin by gender and age groups among aging adults in contemporary China. We then examine key demographic and socioeconomic characteristics associated with lacking different combinations of kin. Lastly, we test for differences in received economic support among those lacking different combinations of kin with a particular emphasis on the role played by child gender (i.e., sons compared to daughters).

The Unique Demography of China

The Chinese population has undergone unprecedented demographic change in the past 50 years. Life expectancy at birth rose sharply from 43.4 in the 1960s to over 76 in 2015 (World Bank, 2016). The total fertility rate entered a period of sustained decline around 1960 (United Nations Population Division, 2015), with the largest drops occurring in the early 1970s, before the government introduced its one-child policy in the late 1970s (Attané, 2002). In the 1990s, China’s total fertility rate fell below replacement where it remains to this day (Morgan, Guo, & Hayford, 2009). Even with the repeal of China’s one-child policy in 2015, fertility is only expected to rise modestly (Zeng & Hesketh, 2016). At the same time, childlessness among women in China is low (MPIDR & VID, 2016b), so, although women bear few children on average, few women do not bear children. This pattern is notably different from other low fertility contexts, such as Japan, which tend to have much higher rates of childlessness (MPIDR & VID, 2016a, 2016b). The mean age at first birth for women in China is currently about 25, which it has reached after increasing since the 1960s (MPIDR & VID, 2016a,2016b). China is also quickly urbanizing, with the share residing in urban areas rising from under 20% in 1980 to 56% in 2015 (United Nations Population Division, 2015). Urban areas have long demographically differed from rural areas in China (Lee & Feng, 1999), and their growth might have implications for the continued maintenance of family and gender norms (Xie & Zhu, 2009).

Declining fertility and mortality also interact directly and indirectly with Chinese social norms around gender and marriage to produce changes in the relationship market and kin availability. There is a recent shortage of marriageable women and an excess of marriage-seeking men—a marriage squeeze—that differentially affects men’s and women’s chances of first and subsequent marriages and thus their likelihood of having a spouse or partner in older adulthood (Guilmoto, 2012; Jiang, Attané, & Feldman, 2007). This phenomenon is partially driven by the skewed sex ratio at birth (SRB), which combined with excess female mortality leads to a substantial number of “missing women” (Sen, 1992). In general, Chinese families desire the birth of sons over the birth of daughters, reflecting a long history of son preference in the country (Jiang, Attané, Li, & Feldman 2007; Lee & Feng, 1999). Sex ratio differences are larger in China’s rural areas, where SRBs are more skewed and there is more excess female mortality (Jiang et al., 2007).

Because of China’s unique demographic history, we expect dramatic differences in kin availability by age groups, sex, and type of kin. First, the timing and nature of China’s fertility decline means that adults ages 65 years and above in the 2010s are likely to have multiple children because they had children before the one-child policy, whereas those under age 65 are likely to have had only one child. Those who had only one child are more likely to be without any children in older adulthood because the risks of a child dying have not declined enough to offset the compounded probability of at least one of two or more children surviving. Second, China’s increasingly skewed SRB after 1980 means that people born after 1955 will be much more likely to only have a single son, compared to earlier birth cohorts who are almost equally likely to have borne a son or a daughter, or even earlier birth cohorts who most likely had multiple children of either sex. Third, China’s marriage squeeze likely affects patterns of remarriage among all older adults and first marriage among those at the younger end of older adulthood, making women more likely and men less likely to be (re)married. These sex differences in marriage will also affect the sex-specific probabilities of having children through the proximate determinants, leading to higher rates of lacking a spouse/partner and children among men than women. Last, we expect that there will be urban/rural differences, reflecting the higher fertility, more skewed sex-ratios, and more acute marriage squeezes in rural areas.

Kin Availability in a Family-Oriented Context

Partners and children are the primary source of family support for aging adults in many countries (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010), and these tendencies are especially true in China (Lloyd-Sherlock, 2000). Scholars have remarked on the centrality of the family in Chinese society for over a century: “[i]t is no exaggeration to say that China as a whole consists of families, and nothing else” (Tao, 1913:47). In Chinese society, children are expected to provide support or assistance for their aging parents as a moral obligation, a relational norm that is not subject to negotiation (Hong & Liu, 2000). Notably, Chinese laws on elder support frequently mention the obligation of children and children-in-law (article 11) to support parents before they mention obligations of aging spouses to support one another (article 16), and children and children-in-law remain legally obliged to support aging parents even when parents remarry (article 18). See articles 10–19 in The Law of Protection for the Rights of the Elderly of the People’s Republic of China (1996), available at http://www.china.org.cn/english/government/207403.htm (Accessed September 09, 2017). This norm of kin-based elder support and accompanying laws have led to a dearth of nonfamily care options for the aged (Salditt et al., 2008). Data from 2006 shows that almost half of Chinese older adults in rural areas live with their children (Cai, Giles, O’Keefe, & Wang, 2012:49), and transfers from family account for more than 20% of income for the poorest retirees (Cai, Giles, & Meng, 2006).

Elder care in China is traditionally gendered (Cancian & Oliker, 2000; Zhan & Montgomery, 2003), with the expectation that sons will provide financially for their aging parents and daughters-in-law will provide instrumental care for their in-laws (Gui & Ni, 1995; Ikels, 1990, 1993). Daughters and sons-in-law have not traditionally been considered to be primary care-providers for aging parents in China. However, these traditional patterns may be changing. For example, data from urban China in 1999 shows that married daughters provided more financial support to their parents than married sons (Xie & Zhu, 2009), while data from 2006 in rural China shows that sons provided more financial assistance than daughters do (Lei, 2013). It is an open question whether those with only daughters are effectively childless in terms of receiving support, and whether the pattern is consistent in both rural and urban China in more recent years.

Considering the intersection of China’s recent demography and its gendered norms about social support, it could be that lacking certain types or combinations of kin are important sources of social stratification affecting support available to older adults. First, we expect that those lacking a spouse/partner and children will be broadly disadvantaged, being less likely than those with close kin to receive support from any source. Even if those lacking a spouse/partner and children might rely more heavily on support from friends, distant family members, or other sources, we expect that this support will not compensate for lacking the key familial providers of such support. Second, it is unclear how those with no living spouse/partner and children of only one sex will fare. On the one hand, traditional expectations hold that those with no living spouse/partner and only daughters will be disadvantaged similar to those without a spouse/partner or any children because sons and their wives are expected to provide for parents, while daughters and their husbands are not. However, since sons are less likely to be married today due to the marriage squeeze, this potentially eliminates a key resource, daughters-in-law. On the other hand, traditional expectations may be eroding. It may be that older adults with no spouse/partner and only sons are more similar to the childless than older adults with no spouse/partner and only daughters. Third, the relationship between lacking kin and support might differ by age groups/cohorts and urban/rural status. Traditional patterns of social support might hold for older cohorts or in rural areas, but they may be eroding among younger cohorts or those in urban areas.

Data and Methods

Sample

We use data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a panel survey with a nationally representative sample of Chinese residents ages 45 years and older (see Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss, & Yang, 2014 for an overview of the CHARLS sample). With a multistage area probability sampling design, CHARLS fielded its baseline wave in 2011 with a total response rate of 80.5% (Zhao, Straus, & Yang, 2013). We use data from the baseline wave to construct our key variables of interests, and we incorporate harmonized measures from the Gateway to Global Aging Data website, which enhances comparability to prior studies of kinlessness. Harmonized CHARLS dataset and Codebook, Version B (November, 2015) developed by the Gateway to Global Aging Data, funded by the National Institute on Ageing (R01 AG030153, RC2 AG 036619, 1R03AG043052). For more information, please refer to www.g2aging.org. Our analysis includes respondents ages 45 and above in 2011 (N = 17,224). We compute weighted estimates using person-level weights adjusting for individual and household nonresponse, making the analysis nationally representative of the non-institutionalized population of China ages 45 years and above.

Measures of Lacking Close Kin

We examine whether respondents lack the following kin types: biological parents, biological siblings, spouse/partner, biological children, and all types of children (biological, step, or fostered children). Measures of the availability of spouse/partner and biological children come from the raw CHARLS data, whereas the remaining measures come from the Harmonized CHARLS data. Guided by the importance of child gender and numbers of children in the Chinese context, we also disaggregate measures of whether the respondent has biological sons or biological daughters and the numbers of such children. Next, we examine the prevalence of lacking different combinations of close kin. We begin with those who do not have a spouse/partner and characterize the types of children available to them (no biological children, only son[s], only daughter[s], and children of mixed sex). In further analyses, we examine six mutually exclusive categories of child availability (no biological children, only one son, only sons (two or more), only one daughter, only daughters (two or more), and mixed sex children). We also examine a 12-category model of child availability cross-classified by spouse/partner availability.

Key Correlates of Lacking Kin

We examine the following demographic and socioeconomic characteristics that come from the Harmonized CHARLS files: gender, current residency, educational attainment, marital history, home ownership, work status, and wealth. Current residency (rural vs urban) indicates the region in which the respondent is living at the time of the survey, defined by the National Bureau of Statistics. Educational attainment is categorized as primary education versus secondary education or more. Marital history is measured as ever married (including currently married and separated/divorced/widowed) versus never married. Home ownership captures whether or not the respondent’s household owns the primary residence. Currently working captures whether or not the respondent did any work (including employed paid job/self-employed/unpaid for family business/agricultural work) in the past year. We measure wealth as the reported value of individual checking and savings accounts measured in Yuan; owing to the skew of this variable, we examine wealth quartiles. Other wealth measures in CHARLS have non-ignorable amounts of missing data. We also assess respondent’s living arrangements (alone vs with other people) and two measures of health: dichotomized self-rated health (very good or good vs fair, poor, or very poor) and disability (respondents are defined as disabled if they report at least one difficulty in dressing, eating, bathing, and getting in/out of bed).

To characterize how different combinations of lacking kin affect well-being, we examine received economic support, which measures whether or not the respondent reported receiving monetary support in the past 12 months from any source (including parents, children, grandchildren, and other relatives/friends).

Analytic Approach

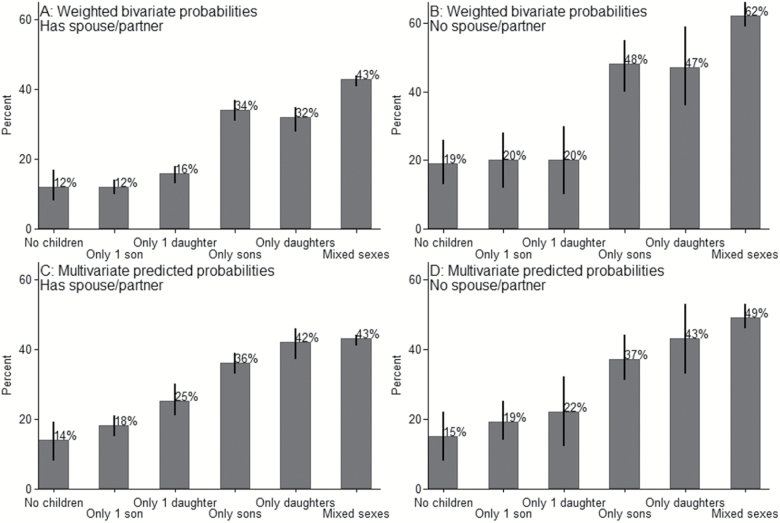

We first describe the prevalence of lacking different types of living close kin in isolation and in combination (Table 1). Next, we examine the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics that are associated with having different, mutually exclusive categories of child availability (none, only son[s], only daughter[s], and children of mixed sexes) among those without a living spouse/partner (Table 2). In this table, we include categories reflecting missing responses for each variable of interest to clarify how data missing-ness correlates with kin availability. Next, we examine how lacking close kin is associated with the receipt of economic support. We estimate multivariate logistic regressions predicting receipt of support by kin availability (Table 3), controlling for respondents’ gender, age group, and all variables in Table 2. We first test the independent effects of availability of different types and numbers of children (six mutually exclusive categories) and spouse/partner availability on receipt of economic support (Model 1). Then, we test a model that cross-classifies the child availability categories by spousal availability through interaction terms that let us examine whether having a spouse changes the patterns (12 mutually exclusive categories) (Model 2). To address rural–urban differences, we also stratify the analysis by urban versus rural residency (Models 3 and 4). We chart the probability of receiving economic support by kin availability, descriptively (Figure 1A and B) and with predicted values from the regression shown in Model 2, Table 3 (Figure 1C and D). All regression models use clustered standard errors by household.

Table 1.

Percentage (SE) Lacking Different Types and Combinations of Close Kin among Adults Ages 45+, CHARLS, 2011 (N = 17,224)

| Ages 45–64 | Ages 65+ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 45+ | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Percent (SE) without each kin type | |||||

| No biological parents | 65.62 (0.58) | 53.07 (1.00) | 56.10 (1.02) | 93.44 (0.62) | 94.57 (0.61) |

| No biological siblings | 10.30 (0.33) | 4.82 (0.46) | 4.82 (0.29) | 22.30 (1.32) | 26.56 (1.18) |

| No partner or spouse | 14.75 (0.41) | 7.54 (0.70) | 8.33 (0.44) | 18.86 (1.13) | 45.25 (1.35) |

| No son (has only daughter(s)) | 14.95 (0.45) | 18.22 (0.84) | 17.34 (0.80) | 8.37 (0.76) | 7.01 (0.69) |

| No daughter (has only son(s)) | 26.06 (0.54) | 30.30 (1.00) | 29.25 (0.94) | 16.53 (1.00) | 16.46 (0.99) |

| No biological children | 3.33 (0.24) | 3.70 (0.30) | 2.16 (0.22) | 5.10 (1.01) | 3.84 (0.97) |

| No children of any type | 2.34 (0.22) | 2.74 (0.25) | 1.43 (0.19) | 3.59 (0.99) | 2.53 (0.95) |

| Percent (SE) lacking combinations of types | |||||

| No spouse/partner and has mixed sex children | 8.80 (0.30) | 2.48 (0.40) | 4.45 (0.31) | 11.81 (0.91) | 32.38 (1.25) |

| No spouse/partner and only son(s) | 3.15 (0.24) | 2.11 (0.52) | 2.09 (0.22) | 3.33 (0.48) | 8.20 (0.76) |

| No spouse/partner and only daughter(s) | 1.40 (0.13) | 0.75 (0.14) | 1.17 (0.16) | 2.10 (0.54) | 2.91 (0.46) |

| No spouse/partner and no biological children | 1.36 (0.11) | 2.10 (0.23) | 0.54 (0.14) | 1.71 (0.30) | 1.35 (0.32) |

| No spouse/partner and no children of any type | 1.25 (0.11) | 1.89 (0.22) | 0.52 (0.14) | 1.78 (0.35) | 1.12 (0.31) |

| No spouse/partner, no children of any type, and no biological parents | 0.92 (0.09) | 1.34 (0.17) | 0.31 (0.10) | 1.73 (0.35) | 0.72 (0.22) |

| No spouse/partner, no children of any type, and no biological siblings | 0.16 (0.04) | 0.15 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.40 (0.20) |

| No spouse/partner, no children of any type, no biological parents, and no biological siblings | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.09) |

| N | 17,224 | 6,094 | 6,514 | 2,303 | 2,311 |

Note: Weighted by person-level weights to be nationally representative of noninstitutionalized adults ages 45 years and above. Two observations are missing for gender information. SE = Standard error.

Table 2.

Percentage (SE) Lacking Different Combinations of Close Kin by Demographic Characteristics, CHARLS Ages 45+, 2011 (N = 17,224)

| No spouse/partner and no biological children | No spouse/partner and only son(s) | No spouse/partner and only daughter(s) | No spouse/partner and has mixed sex children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall percentage | 1.36 (0.11) | 3.15 (0.24) | 1.40 (0.13) | 8.80 (0.30) |

| Current Residency | ||||

| Rural | 1.77 (0.18) | 2.99 (0.22) | 0.99 (0.13) | 9.94 (0.36) |

| Urban | 0.94 (0.14) | 3.30 (0.42) | 1.82 (0.22) | 7.66 (0.48) |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 2.18 (0.23) | 4.12 (0.30) | 1.49 (0.21) | 14.56 (0.53) |

| Secondary or more | 0.74 (0.10) | 2.43 (0.35) | 1.34 (0.15) | 4.50 (0.34) |

| Marital History | ||||

| Ever | 0.37 (0.06) | 3.17 (0.24) | 1.39 (0.13) | 8.87 (0.31) |

| Never | 92.57 (2.77) | 1.46 (1.06) | 3.08 (2.23) | 2.89 (1.42) |

| Living Arrangements | ||||

| With others | 0.70 (0.10) | 2.50 (0.20) | 1.09 (0.11) | 6.57 (0.29) |

| Alone | 11.16 (1.06) | 12.91 (2.07) | 6.01 (1.04) | 42.04 (2.25) |

| Currently Working | ||||

| No | 1.69 (0.22) | 5.37 (0.50) | 2.39 (0.27) | 15.60 (0.68) |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.13) | 1.84 (0.24) | 0.71 (0.09) | 4.80 (0.25) |

| Missing (1.26%) | 1.88 (1.41) | 2.10 (0.87) | 4.84 (2.92) | 5.73 (1.98) |

| Ownership of Primary Residence | ||||

| No | 1.93 (0.37) | 3.83 (1.10) | 1.36 (0.32) | 12.85 (1.39) |

| Yes | 1.29 (0.12) | 3.06 (0.23) | 1.34 (0.13) | 8.25 (0.29) |

| Missing (2.67%) | 0.95 (0.45) | 2.97 (0.82) | 2.95 (1.49) | 8.41 (1.96) |

| Individual Checking and Savings | ||||

| First Quartile | 2.47 (0.35) | 4.14 (0.40) | 1.99 (0.32) | 12.53 (0.82) |

| Second Quartile | 1.46 (0.25) | 2.50 (0.32) | 1.18 (0.21) | 10.42 (0.63) |

| Third Quartile | 0.71 (0.15) | 2.74 (0.37) | 1.05 (0.25) | 6.93 (0.54) |

| Fourth Quartile | 0.82 (0.16) | 2.59 (0.31) | 1.30 (0.20) | 6.21 (0.46) |

| Missing (7.06%) | 1.38 (0.39) | 4.56 (1.71) | 1.50 (0.59) | 7.86 (1.06) |

| Self-rated Health | ||||

| Good or better | 0.93 (0.19) | 3.03 (0.58) | 0.86 (0.18) | 7.03 (0.53) |

| Fair or worse | 1.50 (0.14) | 3.18 (0.25) | 1.53 (0.14) | 9.40 (0.36) |

| Missing (0.72%) | 1.55 (1.14) | 3.58 (1.49) | 5.68 (4.52) | 8.89 (3.41) |

| Disabled | ||||

| No | 1.10 (0.10) | 2.92 (0.26) | 1.17 (0.11) | 7.61 (0.30) |

| Yes | 3.58 (0.66) | 5.07 (0.72) | 2.91 (0.61) | 19.34 (1.29) |

| Missing (1.85%) | 1.00 (0.56) | 3.19 (1.12) | 3.41 (2.12) | 6.87 (1.89) |

Note: Weighted by person-level weights to be nationally representative of noninstitutionalized adults aged 45 years and above. Disability defined as having at least one difficulty in dressing, eating, bathing, and getting in/out of bed. SE = Standard error.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressions Predicting Received Economic Support, CHARLS Ages 45+, 2011

| Receive economic support | Total sample | Urban residents | Rural residents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Category of Kin Availability | ||||

| Mixed sex children | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Only one son | 0.288*** | 0.296*** | 0.331*** | 0.259*** |

| Only sons (two or more) | 0.749*** | 0.768*** | 0.788 | 0.744** |

| Only one daughter | 0.430*** | 0.453*** | 0.412*** | 0.541** |

| Only daughters (two or more) | 0.935 | 0.954 | 0.807 | 1.077 |

| No biological children | 0.205*** | 0.210*** | 0.285*** | 0.164*** |

| No spouse/partner | 1.204** | 1.295** | 1.339* | 1.240* |

| Mixed sex children × No spouse/partner | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Only one son × No spouse/partner | 0.842 | 1.404 | 0.479* | |

| Only sons × No spouse/partner | 0.805 | 0.855 | 0.761 | |

| Only one daughter × No spouse/partner | 0.638 | 0.767 | 0.550 | |

| Only daughters × No spouse/partner | 0.826 | 0.726 | 1.028 | |

| No biological children × No spouse/partner | 0.866 | 1.043 | 0.761 | |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Female | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.985 | 0.987 |

| Ages 65+ (ref: ages 45–64) | 2.029*** | 2.028*** | 1.681*** | 2.244*** |

| Rural residency (ref: urban residency) | 1.392*** | 1.393*** | ||

| Secondary education or more (ref: primary education or less) | 0.681*** | 0.681*** | 0.564*** | 0.762*** |

| Never married (ref: ever married) | 0.700 | 0.734 | 0.516 | 0.879 |

| Lives alone (ref: lives with others) | 1.549*** | 1.550*** | 1.205 | 1.993*** |

| Owns primary residence | 0.641*** | 0.640*** | 0.896 | 0.464*** |

| Currently working | 0.884* | 0.884* | 0.872 | 0.847* |

| Personal savings (ref: first quartile) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Second quartile | 1.269*** | 1.269*** | 1.076 | 1.395*** |

| Third quartile | 1.371*** | 1.371*** | 1.268* | 1.456*** |

| Fourth quartile | 1.175** | 1.176** | 1.057 | 1.290** |

| Self-reported health (ref: good or better) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Fair or worse | 1.231*** | 1.232*** | 1.247** | 1.216** |

| Disabled | 1.220** | 1.220** | 1.356** | 1.155 |

| Constant | 0.705*** | 0.700*** | 0.673* | 1.194 |

| N | 15,514 | 15,514 | 6,059 | 9,455 |

| −2LL | 1,8793.66 | 1,8789.06 | 6,965.43 | 11,718.15 |

Note: Models based on nonmissing values of covariates (i.e., list-wise deletion). In Model 2, Model 3, and Model 4, all interactions are significant as a group (fa.000). Models using multiple imputation estimates show consistent results (not shown).

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Probability of receiving economic support by categories of kin availability, weighted probabilities (panel A and B), and multivariate predicted probabilities (panel C and D), CHARLS ages 45+, 2011.

RESULTS

The top portion of Table 1 presents the percentages of adults ages 45 years and above without each type of close kin. Having a biological parent alive during older age in China is relatively uncommon, with nearly two-thirds (65.6%) lacking living parents. About 10% lack a living biological sibling. Lacking a partner/spouse is moderately high (14.8%). Almost 15% of aging adults in China do not have a son, whereas over a quarter (26.1%) lack a daughter, a pattern consistent with the country’s skewed SRB since the 1980s and excess female mortality. Most aging adults have at least one child, but two percent do not have any children (including biological, step/foster children), and over three percent (3.3%) lack biological children. These rates are consistent with documented low rates of childlessness in China. As for those who lack different combinations of close kin, nearly nine percent lack a spouse/partner but have at least one son and one daughter, 3.2% lack a spouse/partner and have only sons, 1.4% lack a spouse/partner and have only daughters, and 1.4% lack a spouse/partner and have no biological children. It is very uncommon for Chinese aging adults to be without any living close kin. For instance, less than one percent simultaneously lack a spouse/partner, children of any type, and a biological parent at the same time, and only 0.1% simultaneously lacks a spouse/partner, children, biological parents, and biological siblings.

Table 1 also highlights age and sex differences in kin availability. Both men and women aged 65 years and above are more likely to lack biological parents, biological siblings, and a spouse/partner than those aged 45–64 years. The older cohort is also much less likely to have only sons or daughters than the younger cohort, reflecting higher fertility among those who had children before the one-child policy. As for gender differences in kin availability, more men than women lack biological children in the younger age group (3.7% vs 2.2%, t = −4.27, df = 12,527, p < .001), consistent with the marriage squeeze in China, which largely determines childbearing. Women’s greater propensity to marry, however, does not translate into greater likelihoods of having a spouse/partner available because women tend to marry younger and live longer than their husbands/partners. Among respondents 65+, a much higher percentage of women are without a spouse or partner (women 45.3% vs men 18.9%, t = 14.94, df = 4,610, p < .001)). Women and men aged 45–64 years are similarly likely to have no spouse/partner and children of one sex or the other, but women are more likely to have no spouse/partner and mixed sex children and less likely to have no spouse/partner and no children. This tendency is driven by marriage as a proximate determinant on childbearing and the relatively weak role of mortality among the younger cohort. In the older cohort, where mortality is higher, women are more likely to be unpartnered than men. Lower childlessness among women than men prevails, however, making women ages 65 years and above less likely than men at the same ages to be unpartnered and without biological children or children of any type.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of lacking four different combinations of close kin by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Adults lacking a spouse/partner and biological children (first column) are the most disadvantaged, and this type of kinlessness is particularly concentrated among those with less education and wealth, rural residents, the never married and those who live alone, and people in worse health. The prevalence of lacking a spouse/partner and only having children of a single sex is slightly more common in urban China. These groups are not quite as economically disadvantaged as those without a spouse/partner and children, but this type of kin availability is more common among disadvantaged groups in terms of those with less education, who live alone, have less wealth, and worse health. In contrast, the prevalence of lacking a spouse/partner and having mixed sex children is more common in rural China.

Next, we examine how kin availability is associated with the receipt of economic support. For child availability, we use six categories to examine the effects of both the number and gender composition of children on the outcome. Figure 1A and B plot weighted percentages and confidence intervals for receiving support by whether the respondent has a spouse/partner and the sex composition of their children derived from bivariate regressions. Receipt of support is patterned by the availability, number, and gender composition of children. Those without children are least likely to receive any support. Those with multiple children consistently receive more support than those with one, but those with mixed sex children are most likely to receive support than those with children of only one sex. The other important finding is that those without a spouse/partner (Figure 1B) often have a higher probability of support than those with comparable children, but with a spouse/partner (Figure 1A).

These patterns become much clearer in our multivariate findings (Table 3) and when considering the predicted probabilities of support (Figure 1C and D). First, as we hypothesized, compared to those with mixed sex children, adults without any biological children are the most disadvantaged in received economic support (Model 1, OR = 0.205, p < .001), followed by those with only one son (OR = 0.288, p < .001), and those with only one daughter (OR = 0.430, p < .001). Adults with no spouse/partner and no biological children are the most disadvantaged in received economic support with 76.4% lower odds of receiving economic support than those with a spouse/partner and mixed sex children (Model 2, OR: 0.210 × 1.295 × 0.866 = 0.236, p < .001). This group (no spouse/partner and no biological children) has only a .15 probability of receiving economic support (Figure 1D). Even if this group relies on friends or more distant kin, support from these sources does not make up for the lack of close kin. In addition, those with a spouse/partner but no biological children have a similarly low probability (.14) of receiving support, highlighting the paramount importance of support from adult children in China. Second, we find that likelihoods of receiving economic support do not align with traditional expectations regarding child sex. Respondents with no spouse/partner and only one son have 67.7% lower odds of receiving economic support than those with a spouse/partner and mixed sex children (Model 2, OR: 0.296 × 1.295 × 0.842 = 0.323, p < .001), whereas those with no spouse/partner and only one daughter have 62.6% lower odds (Model 2, OR: 0.453 × 1.295 × 0.638 = 0.374, p < .01). Among respondents without a spouse/partner, those with only sons have significantly lower predicted probabilities of receiving economic support than those with mixed sex children (Figure 1D, 0.37 vs 0.49, p < .01; pairwise comparisons), whereas those with only daughters are not disadvantaged (Figure 1D, 0.43 vs 0.49, p = .264). Those with only sons have odds of receiving support that are higher than among the childless but lower than among those with only daughters, showing that perhaps traditional norms about sons and daughter(s)-in-law providing support to older adults are shifting.

Last, Models 3 and 4 (Table 3) stratify our analysis by urban/rural areas. We find broadly consistent patterns in the associations between kin availability and receipt of economic support for urban and rural residents. Those without a spouse/partner and without biological children are most disadvantaged in both rural and urban areas. Older adults with one daughter or multiple daughters are comparatively less disadvantaged than those with one or multiple sons are, and this is especially so among rural residents. Although there are many important differences between urban and rural China, the stratification of older adults’ received economic support by child availability appears to be consistent between both areas in these recent nationally representative data.

DISCUSSION

The Chinese system of social support for older adults is premised on family care, particularly children assisting their aging parents. Traditionally, sons (and their wives) are expected to provide financial and instrumental support. However, recent demographic and social changes may be undermining the sustainability of this care system. We find that there are non-negligible subpopulations without the types of close kin that traditionally provide elder care in China. There are important implications of this shift, affecting the need for institutional care, pensions, and the well-being of older adults. We find that 1.4% of older adults are without a spouse/partner and biological children. Because of China’s size, a small percentage kinless translates to a large number of individuals. Our results suggest that there are approximately 6.35 million individuals in China who simultaneously lack a spouse/partner and children of any type, about 630 thousand of whom also have no biological parents or biological siblings. With its rapidly aging population, we expect that China’s population of kinless older adults will continue to grow.

Our analyses reveal that lacking different types of kin is more concentrated among rural residents, those with limited resources, and those with higher health risks. These older adults might already have limited access to medical services and institutional care because of features of China’s economic organization, and it is likely that being kinless adds another layer of disadvantage. With the limitations of China’s pension system (Salditt et al., 2008) and health care coverage and community-based long-term care still under development (Liu, 2004; Feng et al., 2011; Wu, Carter, Goins, & Cheng, 2005)—all of which tend to be less developed in rural areas—other kinship network members (such as cousins or siblings-in-law) might be the main source of support that is available to older adults without close kin in China.

In contrast to the traditional expectation about gendered support from adult children (Ikels, 1990, 1993; Gui & Ni, 1995), our analyses show that those with no spouse/partner and only sons are more comparatively disadvantaged than those with no spouse/partner and only daughters in the receipt of economic support. In contrast to previous findings using older data from urban China in 1999 (Xie & Zhu, 2009) or from rural and urban China in 2006 (Lei, 2013), we find this pattern in both rural and urban China in a more contemporary survey (2011). Traditional patterns of sons and daughters-in-law providing support for older adults may be changing because of the fact that sons are less likely to be married due to the “marriage squeeze” and also because older adults are increasingly likely to have only one child. Perhaps norms about care for parents are changing because of changes in kin availability. These tendencies point to an emerging system of stratification among the older population built around individual gender and the gender of one’s children. In opposition to traditional gendered expectations, our results suggest that having only sons may be especially problematic for older Chinese, and for men more than women.

Unfortunately, data constraints prevent us from analyzing how the availability of different types of kin is changing over time in China, but we can make some guesses about where things are heading. Kin availability among today’s older adults is primarily shaped by excess female mortality, but future older adults will have children born during periods of much more highly skewed SRBs and lower fertility. The majority of adults ages 45 years and above in 2011 were not in their prime reproductive years during early 1980s, when the reported sex ratio at birth in China started to rise (Guilmoto, 2009). Younger cohorts of older adults will be more likely to have only sons compared to only daughters. In addition, sons of the cohorts currently aging into older adulthood, who tend to marry younger women born during a period of more skewed SRBs, may experience an even larger marriage squeeze than current older adults. As such, more and more older adults will have unmarried sons and thus will miss an important source of social support, daughters-in-law.

Shortly after China’s adoption of its one-child policy, the increasing availability of prenatal sex determination technology throughout the country made it possible for large numbers of families to pursue sex-selective abortions in order to comply with fertility mandates while realizing their son preferences (Bongaarts & Guilmoto, 2015). In the 1980s, China’s SRB started to rise from approximately 105 males born for every 100 females to well over 115 during the 1990s, and to 120 in 2000 (Guilmoto, 2009). Current estimates suggest modest retrenchment, but China’s SRB remains elevated at approximately 115 males born for every 100 females (United Nations Population Division, 2015). Such increases occurred even in spite of various relaxations of the one-child policy for families with daughters and other groups (Gu, Wang, Guo, & Zhang, 2007). These SRB levels are highly skewed and represent substantial deviations from the biologically normal rates of 103–106 males born for every 100 females born (Chahnazarian, 1988), and researchers expect their persistence to constrain population growth and hasten population aging (Attané, 2006). As the Chinese population continues to age, the continuously skewed SRB in recent decades will translate into a higher proportion of older adults lacking daughters. In turn, the greater tendency to receive support from daughters may further amplify ongoing stratification among older adults with only sons and with only daughters. Our results and other work suggests that individuals with only sons are less likely to have support and care in older adulthood, despite needing it more. Policymakers should address the need for welfare support and institutional care among those aging adults without close kin, especially among those with limited resources who reside in rural China.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Population Research Institute (P2CHD041025) and Institute for CyberScience at The Pennsylvania State University, and the Government of Canada - Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MYB-150262) and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (435-2017-0618 and 890-2016-9000). The CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study) is supported by Peking University, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Institute on Aging and the World Bank. The harmonized CHARLS from the Gateway to Global Aging Data is funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG030153, RC2 AG036619, 1R03AG043052).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Z. Zhou conducted the data analysis. Z. Zhou, A. M. Verdery, and R. Margolis planned and wrote the study together.

References

- Attané I. (2002). China’s family planning policy: An overview of its past and future. Studies in Family Planning, 33, 103–113. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attané I. (2006). The demographic impact of a female deficit in china, 2000–2050. Population and Development Review, 32, 755–770. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00149.x [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F. (1984). Assessing the physical health effects of social networks and social support. Annual Review of Public Health, 5, 413–432. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F. Glass T. Brissette I. & Seeman T. E (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 51, 843–857. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J., & Guilmoto C. Z (2015). How many more missing women? Excess female mortality and prenatal sex selection, 1970–2050. Population and Development Review, 41, 241–269. Doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00046.x [Google Scholar]

- Cai F., Giles J., & Meng X (2006). How well do children insure parents against low retirement income? An analysis using survey data from urban China. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 2229–2255. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.03.004 [Google Scholar]

- Cai F., Giles J., O’Keefe P., & Wang D (2012). The elderly and old age support in rural China. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. doi:10.1596/9780821386859_ch03 [Google Scholar]

- Cancian F.M., & Oliker S. J (2000). Caregiving and gender. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carney M. T. Fujiwara J. Emmert B. E. Jr, Liberman T. A. & Paris B (2016). Elder orphans hiding in plain sight: A growing vulnerable population. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2016, 4723250. doi:10.1155/2016/4723250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahnazarian A. (1988). Determinants of the sex ratio at birth: Review of recent literature. Social Biology, 35, 214–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. & Herbert T. B (1996). Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–142. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. Zhan H. J. Feng X. Liu C. Sun M. & Mor V (2011). An industry in the making: The emergence of institutional elder care in urban china. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 738–744. doi:10.1111/j.1532- 5415.2011.03330.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B., Wang F., Guo Z., & Zhang E (2007). China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review 33, 129–148. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00161.x [Google Scholar]

- Gui S. X., & Ni P (1995). The “Filling” theory of economic support for the elderly. Population Research, 19, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Guilmoto C. Z. (2009). The Sex Ratio Transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35, 519–549. doi:10.1111/ j.1728-4457.2009.00295.x [Google Scholar]

- Guilmoto C. Z. (2012). Skewed sex ratios at birth and future marriage squeeze in China and India, 2005-2100. Demography, 49, 77–100. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0083-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J. Smith T. B. & Layton J. B (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., & Liu W (2000). The social psychological perspective of elderly care. In Liu W.T. & Kendig H. (Eds.), Who should care for the elderly?: An east-west value divide. Singapore: Singapore University Press. doi:10.1142/9789812793591_0009 [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Umberson D., & Landis K. R (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001453 [Google Scholar]

- Ikels C. (1990). Family caregivers and the elderly in China. In Biegel D.E. & Blum A. (Eds.), Aging and caregiver: Theory, research, and policy. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ikels C. (1993). Chinese kinship and the state: Shaping of policy for the elderly. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 13, 123–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Attané I., Li S., & Feldman M. W (2007). Son preference and the marriage squeeze in china: An integrated analysis of the first marriage and the remarriage market. In Attané I. & Guilmoto C. Z. (Eds.), Watering the neighbor’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia. Paris: Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography; http://www.cicred.org/Eng/Publications/pdf/BOOK_singapore.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. & Wang F (1999). Malthusian models and Chinese realities: The Chinese demographic system, 1700-2000. Population and Development Review, 25, 33–65. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/172371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L. (2013). Sons, daughters, and intergenerational support in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 45, 26–52. doi:10.2753/CSA2162-0555450302 [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-C., Chen Y.-C (2014). Family change in East Asia. In Treas J., Scott J., Richards M. (Eds.), Wiley-Blackwell companion to the sociology of families (pp. 61–82). Oxford, England: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118374085.ch4 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. (2004). Development of the rural health insurance system in China. Health Policy and Planning, 19, 159–165. doi:10.1093/heapol/czh019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P. (2000). Population ageing in developed and developing regions: Implications for health policy. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 51, 887–895. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R. & Verdery A. M (2017). Older adults without close kin in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72, 688–693. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Vienna Institute of Demography (MPIDR & VID) (2016a). Human Fertility Database Retrieved from www.humanfertility.org

- Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Vienna Institute of Demography (MPIDR & VID) (2016b). Human Fertility Collection Retrieved from www.fertilitydata.org

- Morgan S. P. Zhigang G. & Hayford S. R (2009). China’s below-replacement fertility: Recent trends and future prospects. Population and Development Review, 35, 605–629. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X. (2011). China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science, 333, 581–587. doi:10.1126/science.1209396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salditt F., Whiteford P., & Adema W (2008). Pension reform in China. International Social Security Review, 61, 47–71. doi:10.1111/j.1468-246X.2008.00316.x [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. (1992). Missing women: Social inequality outweighs women’s survival advantage in asia and north africa. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 304, 587–588. doi:10.1136/bmj.304.6827.5871559085 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M. & Giarrusso R (2010). Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72, 1039–1058. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao P. L. K. (1913). The family system in China. The Sociological Review, 6: 47–54. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1913.tb02316.x [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. doi:10.12987/yale/9780300102185.001.0001 [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (2015). World population prospects: The 2015 revision DVD Edition. New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ [Google Scholar]

- Verdery A. M. (2017). “Modeling the future of China’s changing family structure to 2100.”Forthcoming book chapter in Eberstadt, Nicholas (ed.) China’s next big demographic problems: Urbanization and family structure, Washington, DC: The American Enterprise Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery A. M., & Margolis R (2017). Projections of white and black older adults without living kin in the United States, 2015–2060. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 11109–11114. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710341114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., & Yao Y (2003). Sources of China’s economic growth 1952–1999: Incorporating human capital accumulation. China Economic Review, 14, 32–52. doi:10.1016/S1043-951X(02)00084-6 [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2016). World Development Indicators, 2016 Retrieved from http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx (Accessed August 21, 2017).

- Wu B. Carter M. W. Goins R. T. & Cheng C (2005). Emerging services for community-based long-term care in urban China: A systematic analysis of Shanghai’s community-based agencies. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 17, 37–60. doi:10.1300/J031v17n04_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. & Zhu H (2009). Do sons or daughters give more money to parents in urban China?Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 174. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00588.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y. & Hesketh T (2016). The effects of China’s universal two-child policy. Lancet (London, England), 388, 1930–1938. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31405-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., & Wang Z (2014). A policy analysis on challenges and opportunities of population/household aging in China. Population Ageing, 7, 255–281. doi:10.1007/s12062-014-9102-y [Google Scholar]

- Zhan H. J., & Montgomery R. J. V (2003). Gender and elder care in china: The influence of filial piety and structural constraints. Gender and Society, 17, 209–229. doi:10.1177/0891243202250734 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Hu Y. Smith J. P. Strauss J. & Yang G (2014). Cohort profile: The china health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 61–68. doi:10.1093/ije/dys203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Straus J., Yang G., et al. (2013). China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study-2011–2012 National Baseline Users’ Guide. Beijing: Peking University. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.