Abstract

As the United States continues to diversify, we review research on both the benefits and challenges of diversity in developmental science. Taking a “contact in context” approach, we focus on the ways that structural and interpersonal diversity influence ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes from early childhood to adolescence. We also consider the ways in which a child’s own ethnicity/race may shape diversity experiences and outcomes over time. Although we review both the benefits and challenges of moving toward diversity, we offer this review with the ultimate goal of optimizing benefits and minimizing challenges. We offer a conceptual model of “contact in context” that integrates diversity at multiple levels, child ethnicity/race, and developmental changes over time. We conclude with recommendations for future research including: development of more nuanced measures that incorporate multiple levels of diversity, time, and child’s ethnicity/race.

Keywords: diversity, development, paradox

The changing demographic landscape, visible national protests, and the election of the first African American president followed by the election of a president with strikingly divergent viewpoints and policies have highlighted racial tensions in the United States. At the same time, the United States is moving towards greater ethnic/racial diversity in the coming decades. Recent and projected demographic changes in the United States’ landscape have been attributed to immigration, higher rates of exogamy, and an increase in multiracial births (Lee & Bean, 2010). The United States census has been instrumental in documenting demographic shifts; for example, beginning in the 2000 census individuals were able to indicate more than one race. Ethnic/racial minority (ERM) citizens are projected to outnumber White citizens by the mid-21st century. For some, more diversity is a welcome change; and for others, it is not.

Recognizing that this demographic shift brings accompanying challenges for organizations and individuals, institutions of higher education and multinational corporations have established offices and appointments focused on diversity and inclusion with the goal of increasing, embracing, and celebrating diversity. The operating assumption is that diversity is beneficial for the health and functioning of the institution and its members; and that one way to achieve this is to facilitate interactions across different backgrounds. There are, without doubt, clear and significant benefits of creating more diverse and inclusive institutions (Gurin, Dey, Hurtado & Gurin, 2002; Smith & Schonfeld, 2000). For example, more diverse teams have been found to arrive at better solutions for complex problems (Cox, Lobel & McLeod, 1991). However, as with any endeavor, there are also a host of challenges (Jones & Dovidio, 2018).

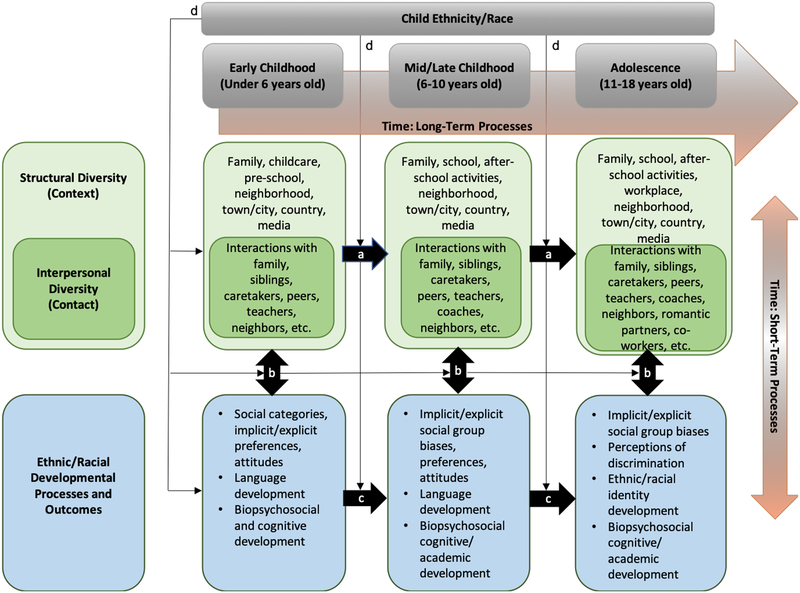

In the spirit of having a balanced discussion, and with the ultimate goal of maximizing the benefits of the country’s movement towards more diversity, as developmental scientists, we consider both the opportunities and challenges of ethnic/racial diversity for developmental outcomes for developing youth. We embark on this discussion first by considering theories of development and diversity, and research investigating the impact of diversity on developmental outcomes beginning in infancy and early childhood when children first demonstrate an understanding of social groups, followed by parallel work in mid/late childhood and adolescence. Based on the review of previous work, we present a conceptual model (Figure 1) that integrates and extends the existing findings from early childhood to adolescence. Our goal is to present a balanced and integrated review of the current state of developmental science as it relates to diversity science to identify both areas where diversity is associated with strengths as well as challenges and to provide constructive guidance for future research, policies, and programs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model considering the Benefits and Challenges of Diversity as “Contact in Context”: Over Time and Development

Theories of Development and Diversity

Human development occurs in a social, cultural and physical context. To appreciate the role of diversity in human development, it is important to consider the synergy between the person and the context. Perhaps one of the most widely used models to articulate the role of context in development is Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory in which the developing person occupies a focal point surrounded by concentric circles and enveloping layers of context (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Recently, Bronfenbrenner’s model was revised to highlight the proximal influence of culture on human development (Vélez-Agosto, Soto-Crespo, Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, Vega-Molina & García Coll, 2017). In this revised model, culture permeates every layer of context, and is indistinguishable from context itself. These developmental models have important implications for understanding contextual influences on the developing child, but they also highlight the dynamic nature of diversity. Diversity is not simply an attribute that exists or fails to exist, it is a psychological experience that results from the interaction of an individual in context. Diversity experiences do not exist outside of, or around a person, rather they are a resultant product of an interaction between person and context. This conceptualization underscores the subjective nature of diversity. Consider for example two children (i.e., Child A and Child B) in the same objective 2nd grade classroom context; each child may have different subjective experiences of diversity depending on individual differences in past diversity experiences, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, gender, language skills, and other sociodemographic characteristics. Diversity experiences will also depend upon one’s numerical minority/majority status. If Child A is in the numerical ethnic/racial minority in the classroom, that child’s experience of diversity will be qualitatively different from Child B who is a member of the majority. Further, both children will have a markedly different experience if there is no clear majority group in the classroom.

In addition to ecological theory, Allport’s (1954) contact hypothesis (i.e., intergroup contact theory) is also relevant to thinking about how diversity is related to developmental outcomes. According to contact theory, as diversity increases, interpersonal contact between members of different groups also increases. Further, contact under a certain set of conditions has the potential to improve intergroup relations and reduce prejudice. Namely, the quality of contact may be more important than the quantity. Quality is evaluated based on all groups having equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation, support of authorities, and informal interactions. Unfortunately, these conditions are not always probable, realistic, or valued; in which case, contact has the potential to result in adverse outcomes. For example, contact without common goals may result in increased competition and feelings of group threat resulting in self-segregation, isolation, discrimination, and insularity. Group-threat dynamics can highlight the negative potential of low-quality contact (Lee & Bean, 2010), a possible challenge to increasing diversity.

Bringing together elements of cultural ecological theory and contact hypothesis, we propose the “contact in context” as a guiding framework for considering the benefits and challenges of diversity. Recognizing that diversity presents itself at multiple levels, we organize our discussion according to contexts embedded in the cultural microsystems model (Jones & Dovidio, 2018; Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017). We focus on structural and interpersonal layers of the microsystem through which diversity impacts developmental outcomes. In addition, we also consider how a child’s ethnicity/race may impact diversity experiences. Throughout the paper, we aim to give equal weight to the ways in which the movement towards more intergroup contact can result in positive as well as more detrimental effects on human development. Given the United States is already on a journey towards increasing diversity, we present this discussion in the spirit of maximizing benefits and minimizing challenges. Of note, with the purpose of providing a comprehensive review, our discussions include research in the United States and non-United States countries, which likely have different ethnic/racial histories, climate, and contexts. In our review, areas of commonality and divergence between United States and non-United States research are discussed.

Infancy and Early Childhood (Under age 6)

Children start to make sense of their social worlds in infancy and early childhood (Carpendale & Lewis, 2015; Harris, 2006). Young children develop concepts of social categories, distinguish in- and out-group members, and show preferences for ethnic/racial groups (Aboud, 2008; Bigler & Liben, 2007; Hailey & Olson, 2013; Killen, Mulvey & Hitti, 2013; Spears Brown & Bigler, 2005). An emerging, yet limited, literature has examined how social contexts shape children’s ethnic/racial attitudes. Separating structural and interpersonal levels, we review ethnic/racial preferences, learning processes, and social development. We end the section with a consideration of how children’s ethnicity/race may impact diversity experiences across these domains.

Structural.

Ethnic/racial preferences.

Children start to develop implicit ethnic/racial preferences in infancy; infants as young as three months old show looking-time preferences and better recognition for same-race faces (Kelly et al., 2005). These preferences become more concrete and evident in the preschool years as children begin to use race as a social category to understand people and social relationships (Hailey & Olson, 2013; Raabe & Beelmann, 2011). For example, Kindzler and Spelke (2011) found that while 10-month-old infants and 2.5-year-old children in the United States did not exhibit preferences in taking or giving toys to same-versus other-race children, 5-year-old children show a clear preference for same-race children. As such, early to middle childhood has been characterized as a developmental stage when explicit same-race preferences are most evident (Hailey & Olson, 2013).

These same-race preferences are likely shaped, in part, by young children’s greater exposure to same-race others; suggesting that ethnic/racial diversity in the larger social environment may neutralize young children’s same-race preferences through increased exposure to other ethnic/racial groups. For example, while Black infants in ethnically/racially homogenous environments (i.e., Black families) show preferences for same-race faces, Black infants raised in Black and White environments and families did not exhibit differential looking time for Black versus White faces (Bar-Haim, Ziv, Lamy & Hodes, 2006). Similarly, compared to 3- to 5-year-old Anglo-British children from all White or majority White kindergartens, those from racially mixed kindergartens did not favor White in-group members (Rutland, Cameron, Milne & McGeorge, 2005), suggesting similarities between American and European youth. Yet, some research also suggests that while exposure to ethnic/racial diversity likely promotes children’s understanding of race as a social category, these social experiences may not translate into more balanced preferences for same-versus other-race children. Specifically, in the United States, 3- to 6-year-old children from ethnically/racially diverse environments (i.e., neighborhood, childcare setting) were more likely than their peers from less diverse environments to encode ethnicity/race in their social interactions; however, children did not differ in their social preferences for same-versus other-race children (Weisman, Johnson & Shutts, 2015).

Learning Process.

Young children’s experiences with diversity also impact their learning processes. Children are selective about the information they deem relevant (Henderson, Sabbagh & Woodward, 2013), and they use various clues to help determine the relevance of information they receive (Wood, Kendal & Flynn, 2013). One of these clues is the language and accent of others around them. Infants (as young as 19-months) and young children are more receptive to learning from adults who speak the same language or share the same accent (Buttelmann, Zmyj, Daum & Carpenter, 2013; Howard, Henderson, Carrazza & Woodward, 2015; Kinzler, Corriveau & Harris, 2011), a preference which may be shaped by children’s exposure to linguistic diversity in their social environment. For example, 19-month-old infants who live in more linguistically-diverse neighborhoods are better able to learn from foreign speakers compared to infants who live in linguistically-homogeneous neighborhoods (Howard, Carrazza & Woodward, 2014). Through exposure to linguistically diverse individuals, children learn that diverse speakers are competent and reliable sources of knowledge (Howard et al., 2014). Linguistic diversity may also increase children’s liking or comfort with foreign speakers, facilitating learning (Howard et al., 2014). Taken together, the evidence suggests a positive effect of diversity in promoting children’s openness to learn from diverse linguistic and ethnic/racial groups.

Social Development.

In addition to ethnic/racial preferences, diversity may also impact young children’s social development. In a nationally representative sample of 3-year-old children in the Netherlands, ERM children showed more behavioral and emotional problems compared to their majority peers; a discrepancy that was greatest in the least diverse neighborhoods (Flink et al., 2013). While research in this area is extremely limited, this European study hints at a protective effect of neighborhood diversity for ERM children’s socioemotional outcomes in a predominantly White context.

Interpersonal.

Ethnic/racial preferences.

The impact of interpersonal diversity, or intergroup contact, is limited compared to structural diversity, possibly due to limited opportunities for interpersonal interactions outside of the family. The research suggests that intergroup contact may promote infants’ encoding of other-race individuals. White infants who were previously not able to discriminate between novel and familiarized Asian faces become able to do so after a three-week daily exposure of Asian females (Anzures et al., 2012; Heron-Delaney et al., 2011). Intergroup contact may also promote young children’s understanding of race as a social category, yet how understanding is related to ethnic/racial preferences is complex. For example, 5-year-old White American girls who had more contact with Black individuals exhibit greater same-race preferences (Kurtz-Costes, DeFreitas, Halle & Kinlaw, 2011). It is possible that while cross-race contact facilitates children’s understanding and use of race as a social category, intergroup experience may result in greater in-group favoritism when children are first learning about racial categories (Bigler & Liben, 2007).

Child ethnicity/race.

Children’s own ethnicity/race matters for understanding the impact of diversity on developmental outcomes. When constructing social categories of race, children not only develop preferences for same-versus cross-race groups, but also high-versus low-status groups. These preferences have implications in contexts such as the United States where there are clear hierarchies between ethnic/racial groups. The research reviewed above focuses on White children, a group with high social status. In contrast, children from relatively lower status groups (e.g., Black, Latinx) often exhibit preferences for high-status out-groups such as Whites (Hailey & Olson, 2013). Moreover, ethnicity/race may be more salient for ERM children whose parents are more likely to engage in parental ethnic/racial socialization (Caughy, O’Campo, Randolph, Nickerson, 2002; Hughes & Chen, 1999; Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson & Spicer, 2006). As such, the impact of diversity on developmental outcomes likely varies between White and ERM children.

Middle and Late Childhood (6 to 10 Years Old)

As children enter formal schooling, they start to have more frequent, consistent, and complex social interactions outside the family (Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003; Hartup, 1996; Rubin, Bukowski & Parker, 1998). As such, more research has investigated how diversity impacts children’s developmental and educational outcomes in middle and late childhood. Organized by structural and interpersonal contexts, we review ethnic/racial attitudes, academic, and social outcomes; and we also consider the influence of child ethnicity/race.

Structural.

Ethnic/racial Attitudes.

Children’s understanding of social categories and norms around equity and prejudice continue to develop in middle and late childhood (Apfelbaum, Sommers, Norton, 2008; Bigler & Liben, 2007; Rutland, Killen & Abrams, 2010) and explicit attitudes towards different ethnic/racial groups become more egalitarian over time (Hailey & Olson, 2013). Meta-analytic work within and outside of the United States shows that children’s ethnic/racial and national-origin prejudice peaks in middle childhood (5–7 years old) and decreases in late childhood (8–10 years old; Raabe & Beelmann, 2011). However, children’s implicit attitudes (i.e., preferences for in-groups and groups of high social status) remain relatively stable (Dunham, Baron & Banaji, 2008; Newheiser & Olson, 2012). At the structural level, school and classroom diversity is associated with decreased racial bias, likely because children have more opportunities for contact with other ethnic/racial groups and cross-race friendships (Killen, Clark Kelly, Richardson, Crystal & Ruck, 2010). Children in diverse schools are less likely to use stereotypes to understand social interactions and more likely to view racial exclusion as wrong, compared to those in low diversity schools (Killen et al., 2010). School diversity also affects children’s bias on more indirect or implicit measures. When asked to interpret ambiguous situations, White children attending low diversity schools displayed racial bias, whereas White and Black children attending more diverse schools did not show the same bias (McGlothlin & Killen, 2010).

Academic Outcomes.

The impact of diversity on student achievement has received the most extensive attention. Since Brown v. Board of Education, desegregating schools has been a central goal and topic of educational policies. The driving force to desegregate educational settings is tied to social justice and equity, with the purpose of providing ethnic/racial minority students equal resources and opportunities to learn (Antonio et al., 2004; Gurin et al., 2003; Tam & Bassett, 2004). Yet, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, American schools are more segregated than they have been in the past (Orfield & Lee, 2007; Reardon, Yun & Eitle, 2000). Understanding how diversity and segregation influence youth outcomes is still an important goal of this research.

Due to a historical focus on segregation, early research focused primarily on how a lack of diversity, operationalized as school segregation or the proportion of ERM students, is associated with poor academic outcomes (Ward Schofield & Hausmann, 2004). Meta-analytic work synthesizing studies within and outside of the United States over the past 20 years shows that segregation, (i.e., higher concentrations of African American students, Latinx students, or minority students in general), has a small negative effect on academic achievement among K-12 students (Mickelson, Bottia & Lambert, 2013; Van Ewijk & Sleegers, 2010a). Segregated schools are disadvantaged on multiple dimensions, including limited social resources, poorer quality teaching, and less emphasis on achievement (Antonio et al., 2004; Gurin, Dey, Gurin & Hurtado, 2003; Tam & Bassett, 2004). In contrast, integrated and diverse schools provide more equitable educational opportunities for ERM students yielding more promising academic outcomes. Most recently, Sean Reardon (2016) analyzed standardized achievement tests for every public school district in the United States from 2009–2012 for children in grades 3–8 and found that school ethnic/racial segregation was predictive of Black-White achievement gaps, adjusting for neighborhood-level effects; however, exposure to low-income classmates seems to be driving the school segregation effect.

Building on the school desegregation literature, recent research has started to use indicators of ethnic/racial composition that more closely capture diversity and heterogeneity, such as the Simpson’s index of diversity (Budescu & Budescu, 2012). This line of work has highlighted the academic benefits of diversity and some nuances of these benefits, a pattern observed in both United States and European national data. For example, using data from the nationally representative sample in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K:1998–99), Benner and Crosnoe found that school-level ethnic/racial diversity promotes children’s standardized test scores (Benner & Crosnoe, 2011). Moreover, by considering diversity in conjunction with proportion of same-race peers at school, this research suggests that the benefits of diversity on children’s academic outcomes are most evident when children have more same-race peers at school or in the classrooms (Benner & Crosnoe, 2011). Similarly, using data from a nationally representative sample of elementary students in Germany, Rjosk et al. (2017) found that classroom ethnic/racial diversity was positively associated with students’ math achievement scores after accounting for the proportion of minority students in the classroom.

Why might diversity be associated with improved academic outcomes? One possible mechanism may be through “disequilibrium” (Piaget & Mussen, 1983); whereby contact with ethnically/racially diverse peers exposes children to diverse perspectives, values, attitudes, and behaviors that may challenge their existing knowledge structure. In response, children think and learn differently, and are better able to reconcile discrepancies – a process that promotes intellectual growth (Benner & Crosnoe, 2011; Gurin et al., 2003). Diversity may also lubricate social relationships such as home-school connections that are critical for promoting children’s academic outcomes. Among national data from ECLS-K, Benner and Yan (2015) observed that diversity, in combination with a critical mass of same-race students in classrooms, promoted parental involvement, which in turn, was associated with higher student reading scores.

Social Outcomes.

In contrast to the academic benefits associated with school diversity, how school diversity contributes to children’s social relationships is less clear. For example, students in diverse schools were more likely to predict that racial exclusion would occur (Killen et al., 2010). A Dutch study shows that children in diverse schools are more likely to engage in bullying behaviors (as a victim, bully, or bully-victim) regardless of the child’s own majority and minority status (Jansen et al., 2016). Post-hoc analyses show that children’s bullying behaviors peak in moderately diverse schools and decrease in more diverse schools (Jansen et al., 2016). We observe a similar pattern in adolescent samples in the United States, where intergroup peer relationships are most problematic in moderately diverse settings (Moody, 2001). Some of the challenges associated with structural-level diversity is that it does not take into account the child’s own ethnicity/race. For example, a child may attend a school with high structural ethnic/racial diversity, however, the child may have no same-race peers in the school. In this case, “diversity” may not confer developmental protection since it appears that the benefits of diversity may be in part driven by same-race others; indeed, research in both United States and Europe has identified a positive link between same-race representations and students’ school belonging (Benner & Crosnoe, 2011; Rjosk et al., 2017). For example, students in diverse schools who have access to a critical mass of same-race peers were most likely to have optimal developmental outcomes (Benner & Crosnoe, 2011).

Interpersonal.

Ethnic/racial Attitudes.

At a more proximal level, consistent with contact theory (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), children’s contact with ethnic/racial groups and cross-race friendships are associated with lower levels of prejudice (see a meta-analytic study: Tropp & Prenovost, 2008). This association tends to be stronger when intergroup contact occurs under optimal conditions involving equal status, common goals, cooperation, and support from institutional authorities (Tropp & Prenovost, 2008). Intergroup contact also influences children’s moral reasoning regarding race-based social exclusion (Killen, 2007). In the United States, Children who have greater intergroup contact (e.g., cross-race friendships in classrooms, neighborhood, and community, interracial interactions on school projects, and diversity in school and neighborhoods) are more likely to report that race-based exclusions are wrong (Crystal, Killen & Ruck, 2008) and less likely to report that they did not know how to respond (Ruck, Park, Killen & Crystal, 2011). These patterns were observed among 4th, 7th and 10th graders and for both majority and ERM students (Crystal et al., 2008). Further, longitudinal data in Europe also documents a reciprocal relation between cross-race friendships and intergroup attitudes, for children from both majority and minority groups (Feddes, Noack & Rutland, 2009; Jugert, Noack & Rutland, 2011).

Social Outcomes.

How diversity at the interpersonal level impacts children’s socioemotional outcomes is more complex. Research suggests that cross-race contact is linked to children’s social competence. Across ethnic/racial groups, children who had cross-race friendships are more likely to be viewed by teachers and peers as being more competent (i.e., greater sociability, empathy, and leadership) compared to children who did not have a cross-race friend (Hunter & Elias, 1999; Kawabata & Crick, 2008). Due to the cross-sectional data, the directionality of contact and social competence link is indeterminable. While cross-race friendships may provide a context in which children can develop sensitivity and understanding of peers from diverse groups (Aboud & Levy, 2000; Kawabata & Crick, 2008), it is equally possible that socially competent children are more capable of making friends from different backgrounds (Aboud & Levy, 2000).

How diversity and cross-race friendships influence children’s social relationships is less clear. On the one hand, longitudinal data has found that across ethnic/racial groups, children who have cross-race friendships show decreased victimization over time (Kawabata & Crick, 2008). The benefits of cross-race friendships on decreased victimization and increased social support are also most evident in ethnically/racially diverse classrooms (Kawabata & Crick, 2008). Yet, research has also identified some challenges associated with cross-race friendships: for both White and Black children in the United States, while those with more integrated social relationships are more accepted by cross-race classmates, they are also less accepted by same-race classmates (Wilson & Rodkin, 2011; 2013), indicating that social integration may confer greater acceptance by other ethnic/racial groups at the cost of same-race relationships.

Child ethnicity/race.

Although studies have documented salutary effects of interracial contact and diversity for the ethnic/racial attitudes of children from diverse ethnic/racial groups, this relation may be weaker for ERM children. While White majority children with more cross-race friendships showed more positive evaluations of outgroup members and lower levels of prejudice, no significant relation between cross-race friendships and ethnic/racial attitudes were observed among ERM children in cross-sectional (Aboud, 2003) and longitudinal data (Feddes et al., 2009). At the classroom level, White children who were from linguistically or racially diverse classrooms showed more positive evaluations of ERM groups compared to White children from linguistically and racially homogenous classrooms; however, Latinx children’s evaluations of other ERM groups did not vary by classroom diversity (Tropp & Prenovost, 2008).

Similarly, although the social benefits of diversity and cross-race friendships are observed for children from diverse ethnic/racial groups in some research (e.g., Kawabata & Crick, 2008), these benefits tend to be less evident for ERMs in other work. In contrast to White children who enjoy the social benefits of having at least one cross-race friend, Black children with at least one cross-race friend are rated as less popular, prosocial and less of a leader by their peers, compared to Black children who do not have a cross-race friend, even when they are in the majority in their classroom (Lease & Blake, 2005). White children who are socially segregated are perceived as less popular among both same- and cross-race peers, while Black children who are socially segregated are perceived as more popular among both same- and cross-race peers. This suggests decreased popularity among Black children who are more socially integrated (i.e., have cross-race friends; Wilson & Rodkin, 2011; 2013) and highlights the need to consider children’s own ethnicity/race and social status when investigating the impact of diversity on social adjustment and peer relationships.

Adolescence (10 to 18 Years Old)

Adolescence is a time when children enter and interact with more complex social environments (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). At the same time, they are actively constructing a sense of identity including how ethnicity/race might be incorporated it into their sense of self (Phinney & Chavira, 1992). Adolescents spend increasingly more time outside of family settings, and their social interactions and relationships take on added significance during this developmental period (Brown & Larson, 2009; Knoll, Magis-Weinberg, Speekenbrink & Blakemore, 2015). Ethnicity/race takes on a new-found salience during adolescence. While research continues to investigate how diversity impacts adolescents’ ethnic/racial attitudes, academic outcomes, and socioemotional adjustment, ethnic/racial identity becomes an important developmental domain, especially in the United States where ethnic/racial discrimination and identity are extensively investigated (Yip et al., under review). We also observe more research investigating the affective dimensions of adjustment (e.g., school belonging, loneliness). At the end of the section, we consider how adolescent ethnicity/race impacts diversity experiences.

Structural.

Ethnic/racial Attitudes.

Diversity in peer groups and schools is associated with improved intergroup attitudes. In an ethnically/racially diverse sample of adolescents, Juvonen et al., (2017) found that adolescents in diverse schools reported more fair and equal treatment from teachers and lower out-group distance. The benefits of school diversity on ethnic/racial attitudes were most evident among adolescents in ethnically/racially diverse classrooms (Juvonen et al., 2017). A more perplexing pattern emerges when we examine ethnic/racial attitudes at the group level or interracial relationships. While individuals tend to report improved ethnic/racial attitudes in diverse settings, interracial relationships do not necessarily follow the same pattern. Nationally representative data from the Add Health study in the United States finds a curvilinear relation between school diversity and peer network segregation, such that segregation is most evident in moderately diverse schools (Moody, 2001). Studies in both United States and Europe show that greater school, classroom, and neighborhood diversity is also associated with a decreased tendency to form cross-race friendships (Munniksma, Scheepers, Stark & Tolsma, 2017) and poorer interracial climate (Benner & Graham, 2013; Benner, Graham & Mistry, 2008). Ironically, school diversity has also been observed to increase both interracial friendliness and interracial conflict (Goldsmith, 2004).

Ethnic/Racial Identity.

Exploring and finding meaning related to one’s ethnicity/race is a key developmental task for ERM adolescents (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). While the development of ethnic/racial identity is closely tied to contact with same-race others and representations of same-race others in the larger social environment (Graham, Munniksma & Juvonen, 2014; Syed, Juang & Svensson, 2018; White, Knight, Jensen & Gonzales, 2017), diversity may promote ethnic/racial identity development due to the increased salience of ethnicity/race in diverse settings (Moody, 2001). For example, school diversity is associated with meaningful shifts in adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity in middle school in the United States (Nishina, Bellmore, Witkow & Nylund-Gibson, 2010). Adolescents who are the numeric majority at school use the same ethnic identification label over time, while African American and Latinx adolescents who are the numeric minority or at diverse schools were more likely to switch to an ethnic/racial identification consistent with the school context (e.g., African American to multiethnic; Nishina et al., 2010).

While ethnic/racial identity has been conceptualized as a developmental asset (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), how school diversity is related to ethnic/racial identity development may involve both positive and negative processes (Yip, Douglass & Shelton, 2013). On the one hand, contextual diversity creates opportunities for both same- and cross-race contact, prompting adolescents to seek meaning of their ethnicity/race, and promoting ethnic/racial identity development (Yip, Seaton & Sellers, 2010). On the other hand, contextual diversity may also increase discrimination, which also promotes ethnic/racial identity development (i.e., rejection-identification hypothesis; Branscombe, Schmitt & Harvey, 1999; Cheon & Yip, under review; Gonzales-Backen et al., 2018; Zeiders et al., 2017). Consistent with the negative association between diversity and school racial climate (Benner & Graham, 2013; Moody, 2001), Black adolescents report greater discrimination with more diverse peers at school (Seaton, Yip & Sellers, 2009).

Academic Outcomes.

Like middle and late childhood, research in adolescence has also highlighted the academic benefits of diverse educational settings. Meta-analytic work shows that desegregating minority-concentrated schools is associated with a small positive effect on academic achievement among K-12 students (Mickelson et al., 2013; Van Ewijk & Sleegers, 2010b). Similarly, high school diversity has a longitudinal and positive effect on college educational outcomes (Tam & Bassett, 2004). Yet, school diversity may also bring academic challenges. As adolescents make transitions from middle to high school, they navigate a more complex social and academic environment, including more diverse peers (Benner, 2011). While school transitions entail a range of academic and socioemotional changes (Benner & Graham, 2009), an increase in school diversity functions as yet another factor to contribute to students’ adjustment. Students who transition to a more diverse high schools show less disruption in feelings of school belonging, but a greater decrease in GPA (Benner & Graham, 2009) and declining attendance (Benner & Wang, 2014). When investigating perceptions of school climate and feelings of belonging, diversity also poses challenges. Some research suggests that school diversity is negatively associated with students’ perceptions of academic climate (Benner et al., 2008). Yet, other research using nationally-representative data finds that school belongingness is better predicted by the proportion of same-ethnic peers as opposed to the diversity of the student body (Benner & Wang, 2014, 2015). Together, these findings underscore a focus on affective features of academic outcomes and the contributions of same-ethnic peers for feelings of belongingness.

Socioemotional Outcomes.

Research on the impact of ethnic/racial diversity on children’s socioemotional outcomes has primarily focused on feelings of vulnerability. For adolescents from diverse ethnic/racial groups, diverse schools and classrooms confer safety, less peer victimization, and less loneliness (Juvonen et al., 2017; Juvonen, Nishina & Graham, 2006). Socioemotional benefits have also been identified for adolescents with more cross-race friendships (Graham et al., 2014). Diverse settings may balance power across ethnic/racial groups, leading to less vulnerability (Juvonen et al., 2017). These benefits are evident for children who are from both majority and minority groups.

Diversity has also been considered as a developmental context that influences the importance of ethnic/racial processes for adolescents’ socioemotional outcomes; and this literature has observed both benefits and challenges. Examining daily associations between discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black adolescents, Seaton and Douglass (2014) identified a buffering effect of diversity such that the discrimination-stress link was evident for adolescents attending schools that are either Black or White majority, but not for adolescents attending schools where there was no clear majority group. Diversity has also been observed to buffer the effects of discrimination on Black adolescents’ life satisfaction (Seaton & Yip, 2009). In contrast, discrimination had a stronger negative effect on Black adolescents’ self-esteem in diverse schools and neighborhoods, indicating an aggravating effect of diversity (Seaton & Yip, 2009). Similarly, daily intragroup contact did not decrease anxiety for adolescents who transitioned to a diverse high school, since learning to navigate a new and diverse setting may override positive in-group experiences (Douglass, Yip & Shelton, 2014).

Beyond the moderating effects of diversity, research has rarely investigated the direct associations between diversity and other socioemotional outcomes. Informed by research that has documented a negative impact of diversity on adolescents’ intergroup relations, perceptions of school climate, and discrimination (Benner et al., 2008; Moody, 2001; Seaton & Yip, 2009), future research is needed to understand whether diversity may pose challenges on adolescents’ socioemotional outcomes such as self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and anxiety.

Interpersonal.

Ethnic/racial Attitudes.

At the proximal level, intergroup contact is associated with more positive intergroup attitudes. Across ethnic/racial groups, adolescents who have more contact with diverse groups are more likely to condemn race-based exclusion as wrong and less likely to report not knowing how to respond (Crystal et al., 2008; Ruck et al., 2011). Longitudinal research conducted in Europe has also identified a bidirectional relation between intergroup contact/cross-race friendships and adolescents’ positive ethnic/racial attitudes (e.g., lower prejudice, more positive outgroups attitudes; Binder et al., 2009; Hewstone & Swart, 2011), and more intergroup contact is associated with increases in intergroup tolerance over time (Wölfer, Schmid, Hewstone & Zalk, 2016). Peer group diversity is also associated with improved intergroup attitudes. Using fMRI technology to investigate adolescents’ responses to ERM faces, Telzer et al. (2013) found that both Black and White adolescents in the United States who report greater peer diversity showed attenuated amygdala response to Black faces, indicating reduced salience of race. Longitudinal data also suggest that more frequent and better quality intergroup contact at the neighborhood level (i.e., average intergroup contact within the same neighborhood) is associated with less increase in intergroup bias among adolescents (Merrilees et al., 2018).

Multiple mechanisms may be underlying the association between diverse contact and ethnic/racial attitudes. In line with theoretical work (Kenworthy, Turner, Hewstone & Voci, 2005), greater intergroup contact is associated with reduced prejudice and better intergroup attitudes through reduced intergroup anxiety and increased empathy (Binder et al., 2009; Swart, Hewstone, Christ & Voci, 2011). The effect of intergroup contact on attitudes could also be explained by perceived social norms regarding intergroup contact (Ata, Bastian & Lusher, 2009; Tezanos-Pinto, Bratt & Brown, 2010). Greater intergroup contact is associated with perceived support for intergroup contact from parents and peers, as well as perceived fairness in media representations of other ethnic/racial groups, further promoting adolescents’ intergroup attitudes (Ata et al., 2009; Tezanos-Pinto et al., 2010).

Ethnic/Racial Identity.

Intergroup contact is a critical factor for adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity development. Yet, the meaning of contact may look different depending on diversity in the larger context. For Black adolescents in diverse versus homogenous schools, same-race contact and friendships were associated with ethnic/racial identity stability, whereas other-race contact and friendships were associated with identity change (Yip et al., 2010). For Asian American adolescents in diverse schools, contact with same-ethnic others today promoted positive ethnic group feelings the following day; this relation, however, was not significant for adolescents attending predominantly Asian schools (Yip, Douglass & Shelton, 2013). Therefore, how adolescents feel about their ethnic/racial identity seems to depend upon the context in which contact occurs.

Academic Outcomes.

Recent daily diary research has supported the educational benefits of contact with diverse peers. Similar to structural diversity, intergroup contact seems to benefit academic achievement but not academic attitudes. For example, using daily diary data of middle school adolescents from diverse ethnic/racial groups, Lewis et al. (2018) found that daily cross-race peer interactions were associated with higher educational expectations by teachers and higher GPAs, but not students’ feelings towards school. Perhaps similar to work touting the social cognitive benefits of diversity for college students (Gurin, 1999), daily contact with other race peers may also confer academic benefits at earlier points in the developmental lifespan.

Child ethnicity/race.

Despite the positive effects of diverse contact on adolescents’ ethnic/racial attitudes, adolescent characteristics (e.g., majority/minority status) also contribute nuance to this relation. As in middle and late childhood, studies among European adolescents show that the effect of contact on ethnic/racial attitudes tends to be weaker among ERM adolescents (Binder et al., 2009). The mediating mechanism of intergroup anxiety which links contact to attitudes, is also weaker among ERM adolescents (Binder et al., 2009). Moreover, the salutary effect of contact on increases in intergroup tolerance is more evident in adolescence, whereas the positive effect of intergroup tolerance on less steep decreases in intergroup contact over time was more evident in young adulthood (Wölfer et al., 2016). Finally, interventions employing intergroup contact to reduce prejudice among Finnish adolescents finds positive effects among younger participants, while greater contact unexpectedly increased intergroup anxiety among older participants (Liebkind, Mähönen, Solares, Solheim & Jasinskaja-Lahti, 2014).

Conceptual Model Considering the Benefits and Challenges of Diversity as “Contact in Context”: Over Time and Development

Building off of and extending the current literature, we propose a conceptual model (Figure 1) to consider both the benefits and challenges of diversity. This model depicts how diversity experiences from early childhood to adolescence take the form of “contact in context” over time. Our conceptual model builds upon ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998), contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), and cultural microsystems model (Jones & Dovidio, 2018; Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017) reviewed earlier. The conceptual model synthesizes five integrative premises:

1. Diversity as “contact in context.”

Developing youth are exposed to diversity through contact (i.e., interpersonal diversity) in context (i.e., structural diversity). Interpersonal diversity refers to the frequency and degree of contact and interpersonal interactions with same or different ethnic/racial group others at varying degrees of proximity, including family members, neighbors, peers, teachers, romantic partners, and strangers. Interpersonal diversity is typically assessed with daily diary or experience sampling approaches (Binder et al., 2009; Cole & Yip, 2008; Yip, Douglass & Shelton, 2013) or may also be assessed by observational or survey research methods asking youths about their typical interactions (Ruck, Park, Killen & Crystal, 2011; Tropp & Prenovost, 2008). On the other hand, structural diversity is less dynamic and more descriptive, and refers to the ethnic/racial composition in a particular context or setting. Structural diversity is often measured using static indicators such as Simpson’s diversity index, which calculates the probability of two randomly selected children being from different ethnic/racial background. Certainly, structural diversity is necessary at some level to allow for interactions reflecting interpersonal diversity. However, structural diversity alone is not sufficient for interpersonal diversity. While there is more research on the developmental influence of structural diversity, with the advent of technological and methodological innovations, developmental scientists have new tools for assessing diversity at the interpersonal level. We propose a combination of the two levels of analysis (i.e., interpersonal and structural), conceptualized as “contact in context,” that conjointly influence the developing child.

2. Diversity as “contact in context” changes across development (Figure 1, Path a).

Conceptualizing diversity experiences as “contact in context” allows developmental scholars to consider how diversity experiences differ with age. Considering structural diversity alone, as a static feature of the environment, misses important developmental changes in youth’s social worlds. For example, in early childhood, when family, child care contexts, preschool, and media settings are the primary contexts for socialization, children may only be exposed to diversity in these contexts. However, as youth transition to middle and late childhood, formal education and after-school settings become more developmentally salient. As such, interpersonal diversity in the form of interactions with peers and teachers take on more influential socializing roles. During adolescence, youth’s social circle continues to broaden and relationships with romantic partners, and even co-workers will begin to contribute to expanding interpersonal diversity experiences. Moreover, school transitions (i.e., elementary to middle, middle to high school) or family relocations may also offer opportunities for changes in structural and interpersonal diversity experiences. This conceptual model provides a guiding framework for considering how diversity is related to youth development over time. For example, how do diversity experiences and changes, operationalized as “contact in context” (i.e., frequency, degree, or rate of change), influence children’s development over time? Is there a critical or sensitive period in which diversity experiences and changes have more impact on children’s development? Do the patterns and trajectories of development depend on changes in diversity experiences? Besides child’s ethnicity/race, what other individual difference factors might moderate the association between diversity experiences and youth development?

3. Diversity as “contact in contexts” is reciprocally associated with children’s ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes (Figure 1, Path b).

Diversity experiences contribute to factors that account for children’s ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes. As evidenced in our review, these processes and outcomes encompass a broad range of domains including cognition and language development, racial/ethnic attitudes, identity, social relationships, and education. At the same time, ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes also influence children’s perception of both interpersonal and structural diversity. For example, children’s ability to distinguish social categories, preferences for certain social groups, language development (e.g., mono vs. multilingual), and ethnic/racial identity may all contribute to how much they are able or willing to process or engage with their surrounding structural and interpersonal diversity. Moreover, diversity conceptualized as “contact in context” may have differential effects on different dimensions of ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes. For example, while diversity experience may be beneficial to some aspects of development (e.g., increased cognitive flexibility), it may act as a threat to other aspects (e.g., increased ethnic/racial discrimination), highlighting the need for both independent and interactive assessments of developmental dimensions. Finally, these processes occur in the context of time within each individual and developmental period. In order to account for these, the examination of relatively short-term processes (e.g., moment-to-moment, day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year) within-individual and within-developmental period considerations and analyses are necessary.

4. Ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes change over time (Figure 1, Path c).

Because earlier experiences cumulatively serve as the developmental foundation for subsequent experiences and development, it is also important to consider how earlier ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes change over time across developmental periods. Ethnic/racial development mirrors overall human development. For example, from early childhood to mid/late childhood, children develop broad social categories which are then infused with increasingly sophisticated implicit/explicit social group biases. Even if the current diversity experiences are objectively similar, how each child perceives both the interpersonal and structural diversity may vary depending on their unique developmental histories. Therefore, we suggest that these processes need to be examined across developmental periods with a focus on changes over time.

5. All processes and outcomes must consider the child’s ethnicity/race.

Although a social construction, children’s ethnicity/race shapes their development (Garcia Coll, Crnic, Lamberty, Wasik, Jenkins, Garcia & McAdoo, 1996; Spencer, Dupree & Hartmann, 1997). A child’s ethnicity/race shapes both how the child interacts with their diversity contexts as well as how the diversity contexts interact with the developing child. For example, both Black and White students benefit academically when they have a same-race teacher (Egalite, Kisida & Winters, 2015). At the same time, research has found that Black youth are more harshly disciplined in the classroom, particularly by White teachers (Downey & Pribesh, 2004). Therefore, the child’s ethnicity/race has the potential to motivate the ethnic/racial developmental processes and outcomes through interpersonal and structural diversity. Assessing “contact in context” allows developmental scientists to unpack similarities and differences in developmental experiences as the same child ventures across contexts in which the child may be in the numerical minority, while being in the numerical majority in other contexts. In line with community psychology’s focus on behavior and activity settings, the developing child’s engagement with social settings is considered to be the primary pathway through which culture influences child development (Barker & Schoggen, 1973; Gallimore, Goldenberg & Weisner, 1993). Further, because ethnicity/race is socially constructed, it is important to acknowledge that a child’s self-selected ethnicity/race may differ from that ascribed by others (e.g., teachers, peers, census), these potential differences and how the differences may chance over time should be considered. In order to account for how the child’s ethnicity/race is related to developmental processes and outcomes, we recommend the assessment of between-person effects across ethnic/racial groups to complement the aforementioned within-person processes.

Conclusions, Recommendations, and Future Directions

There are benefits and costs to moving towards diversity. As the United States continues to diversify, how can developmental scientists employ our science to maximize the benefits while acknowledging and minimizing the costs? We highlight a few recurring themes here. One of these is that to best understand the developmental impact of diversity, we need to move towards better measurement and conceptualization of the static and dynamic ways in which diversity presents itself in the daily lives of children. As scientists move closer to more dynamic, nuanced, and situationally-specific measurements of diversity, we can better approximate the lived experiences of diversity for all children including a focus on the quantity and quality of intergroup contact (Shelton & Richeson, 2006), historical relations (Kiang, Tseng & Yip, 2016), while also considering the ethnicity/race of the individuals in the interaction (Jones & Dovidio, 2018). Contact in context – we cannot study diversity as a static feature of the setting but must consider it to be repeated, dynamic, and proximal interactions of the developing child (and associated characteristics) in context. Consider for example, Latinx Student A who attends a Black/Latinx school as compared to Latinx Student B in White/Latinx school; in both cases, the Simpson’s diversity index would indicate identical levels of diversity but the experiences of diversity in each is qualitatively different. Or consider the Asian student in a predominantly White school who has primarily White friends versus primarily Asian friends. The current state of the science does not yet include tools or theories for considering these levels of nuance.

Moreover, another notable gap in the measurement of diversity is that there is currently no measure that integrates a description of structural (or interpersonal) diversity, that simultaneously considers the ethnicity/race of the developing child. As discussed in the section focused on structural diversity and academic outcomes, current descriptions of diversity tell us nothing about the representation of same-race others in a child’s setting. Research in social psychology points to the academic detriments of solo/token status (Sekaquaptewa & Thompson, 2003) which can undermine any benefits conferred by structural diversity. As such, in order for developmental scientists to make more progress understanding the true benefits and challenges of diversity, it is imperative that we develop new multi-level measurement tools to capture the complexity of integrating the child’s ethnicity/race, the frequency and quality of daily interpersonal interactions, and structural diversity. Diversity and its experience are inherently multi-level, considering the interaction of multiple levels of analysis is imperative for developing recommendations for how to optimize the benefits of intergroup contact. Although developmental theory recognizes that contexts and diversity experiences within these contexts are dynamic and ever-changing, the measurement of diversity remains largely static (i.e., diversity indices are not able to model real-time changes in either evenness or richness). The current measurement of diversity largely overlooks the ways in which experiences of diversity can change from one moment to the next and how repeated exposure to diversity experiences is related to youth development over time. As such, our hope is that future investigations will be able to model more dynamic changes in diversity to better reflect everyday diversity experiences.

Another theme is to consider the perspective and the ethnicity/race of those engaged in intergroup contact. Research shows that the same interaction can be perceived in vastly different ways depending on the background of the respondent (Shelton & Richeson, 2006). In defining what diversity is, it is imperative to consider the perceptions of the persons in question. It is difficult to define “diversity” without qualifying, for whom? As evidenced in Craig and Richeson (2017), reactions to diversity itself depends on the ethnicity/race of the audience. Therefore, it is imperative that scholars systematically investigate the role of individual differences in diversity experiences. For example, more studies need to consider the interactions of individual and various levels (i.e., structural, interpersonal interactions) of contexts beyond adolescence (e.g., neighborhood, geographic regions, family relationships, media/online interactions), considering developmental (e.g., ethnic/racial identity processes, places of socialization, career and relationship choices), and intersecting individual characteristics (e.g., gender, sexual identification, personality traits, socioeconomic status, statistical majority/minority status). Moreover, whereas most of the previous studies compared ethnic/racial differences between Whites and ERMs, dynamics between minority groups must also be considered (Jones & Dovidio, 2018), as ERM groups display different attitudes toward other ERM groups under different circumstances (Craig & Richeson, 2017). Lastly, based on ecological systems theory, we propose that these interactions be placed within both short-term and long-term timeframes as well as the sociohistorical context as young adulthood is still marked by flexibility in modes of thinking and identity that are generated through active person-environment interactions.

Finally, it is important to underscore that we cannot maximize the benefits of diversity by simply throwing people of different backgrounds into the same context. We must actively engage in fostering quality interactions, lasting and meaningful relationships, and mutual respect. This may be why some research finds that “moderate” levels of diversity are associated with poorer outcomes. Diversity is more than richness – the number of groups in a designated context. It is also more than evenness – the relative distribution of groups in the context. When applied to social science, and human interactions, diversity must acquire a psychological and qualitative component. Diversity is about how individuals feel, grow, and learn from intergroup interactions starting in childhood and throughout the lifespan. Research on social norms provides a glimpse into how developmental scholars may begin to maximize diversity for youth outcomes (Ata, Bastian & Lusher, 2009). For example, among middle school students in 56 schools in the United States, Paluck and colleagues (2016) found that an anti-conflict intervention focused on key students in a school’s social network changed social norms about peer conflict and resulted in increased dialogue around conflict and a decline in school disciplinary incidents. Further, the potential to influence social norms does not stop in adolescence; research conducted in Rwanda found that media representations of intergroup conflict influenced beliefs about social norms related to intermarriage and diversity (Paluck, 2009). Together, this research shows that beliefs about interpersonal social norms within school- and national-level contexts are malleable from adolescence to adulthood. Applied to diversity science, this research suggests that changing children’s beliefs about social norms (i.e., intervening at the interpersonal level) may be an avenue for maximizing the benefits of structural diversity.

Although we have organized this paper into developmental categories; development itself is not categorical. Instead, development is cumulative and prior circumstances shape current experiences. As evidenced in Douglass et al (2014), past experiences of ethnic/racial diversity informed present-day experiences of intergroup contact. Extrapolating this to other developmental processes and outcomes, it is important for future work to also consider how past diversity experiences shape current experiences. In addition, attempting to review literature that encompasses early childhood through adolescence, it is also important to acknowledge the role of agency. From infancy to adolescence, agency increases over time and children gain agency as they move through developmental phases. As such, it is important to consider the role of agency in choosing one’s exposure to diversity. For example, adolescents may choose with whom to sit during lunch or recess (i.e., interpersonal diversity), or young adults may choose an institution of higher education based on diversity characteristics (i.e., structural diversity).

Why should developmental scientists consider both the benefits and challenges of diversity? Because the United States is moving towards increasing diversity, and diversity will either result in increased integration and unity, or more insularity and segregation. Despite applying scientifically defensible and rigorous methods to our science, how scientists articulate and situate our research questions is not value-free (Hall, Yip & Zárate, 2016). Recognizing and acknowledging the lenses that scientists bring to bear on their research will move us closer to having more balanced knowledge around issues that are inherently value-laden. Developmental and diversity sciences have the potential to inform pathways to maximize the benefits and minimize the challenges of demographic diversity for the United States and its youth.

Contributor Information

Tiffany Yip, Fordham University.

Yuen Mi Cheon, Fordham University.

Yijie Wang, Michigan State University.

References

- Aboud FE (2003). The formation of in-group favoritism and out-group prejudice in young children: Are they distinct attitudes? Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE (2008). A social-cognitive developmental theory of prejudice Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child, 5571. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE, & Levy SR (2000). Interventions to reduce prejudice and discrimination in children and adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW (1954). The nature of prejudice. [Google Scholar]

- Amir Y (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological bulletin, 71(5), 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonio AL, Chang MJ, Hakuta K, Kenny DA, Levin S, & Milem JF (2004). Effects of racial diversity on complex thinking in college students. Psychological Science, 15(8), 507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzures G, Wheeler A, Quinn PC, Pascalis O, Slater AM, Heron-Delaney M, … Lee K (2012). Brief daily exposures to Asian females reverses perceptual narrowing for Asian faces in Caucasian infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112(4), 484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfelbaum EP, Sommers SR, & Norton MI (2008). Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ata A, Bastian B, & Lusher D (2009). Intergroup contact in context: The mediating role of social norms and group-based perceptions on the contact–prejudice link. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(6), 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Syed M, & Radmacher K (2008). On the intersection of personal and social identities: Introduction and evidence from a longitudinal study of emerging adults. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2008(120), 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Ziv T, Lamy D, & Hodes RM (2006). Nature and nurture in own-race face processing. Psychological Science, 17(2), 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak MEM, & Levin A (2002). Outside of the corporate mainstream and excluded from the work community: A study of diversity, job satisfaction and well-being. Community, Work & Family, 5(2), 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Barker RC, & Schoggen P (1973). Qualities of community life. [Google Scholar]

- Baron JN, & Bielby WT (1980). Bringing the firms back in: Stratification, segmentation, and the organization of work. American sociological review, 737–765. [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD (2011). The transition to high school: Current knowledge, future directions. Educational psychology review, 23(3), 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Crosnoe R (2011). The racial/ethnic composition of elementary schools and young children’s academic and socioemotional functioning. American Educational Research Journal, 48(3), 621–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child development, 80(2), 356–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S, & Mistry RS (2008). Discerning direct and mediated effects of ecological structures and processes on adolescents’ educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Wang Y (2014). Demographic marginalization, social integration, and adolescents’ educational success. Journal of youth and adolescence, 43(10), 1611–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Wang Y (2015). Adolescent substance use: The role of demographic marginalization and socioemotional distress. Developmental Psychology, 51(8), 1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Yan N (2015). Classroom race/ethnic composition, family-school connections, and the transition to school. Applied developmental science, 19(3), 127–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SM, & Hunter JS (1985). A Measure of Success: The WILL Program Four Years Later. Journal of the National Association of Women Deans, Administrators, and Counselors, 48(2), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, & Liben LS (2007). Developmental intergroup theory explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(3), 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Binder J, Zagefka H, Brown R, Funke F, Kessler T, Mummendey A, … Leyens J-P (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond MA, Punnett L, Pyle JL, Cazeca D, & Cooperman M (2004). Gendered work conditions, health, and work outcomes. Journal of occupational health psychology, 9(1), 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman NA (2010). College diversity experiences and cognitive development: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 80(1), 4–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman NA (2011). Promoting participation in a diverse democracy: A meta-analysis of college diversity experiences and civic engagement. Review of Educational Research, 81(1), 29–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman NA (2013). How much diversity is enough? The curvilinear relationship between college diversity interactions and first-year student outcomes. Research in Higher education, 54(8), 874–894. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey RD (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (Eds.). (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. Hoboken, NJ,US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Larson J (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence Handbook of adolescent psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Budescu DV, & Budescu M (2012). How to measure diversity when you must. Psychological methods, 17(2), 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttelmann D, Zmyj N, Daum M, & Carpenter M (2013). Selective imitation of in-group over out-group members in 14-month-old infants. Child development, 84(2), 422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D (1971). The Attraction Paradigm, New: York: Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale JI, & Lewis C (2015). The development of social understanding Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, O’Campo PJ, Randolph SM, & Nickerson K (2002). The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child development, 73(5), 1611–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MJ, Astin AW, & Kim D (2004). Cross-racial interaction among undergraduates: Some consequences, causes, and patterns. Research in Higher education, 45(5), 529–553. [Google Scholar]

- Chang MJ, Denson N, Saenz V, & Misa K (2006). The educational benefits of sustaining cross-racial interaction among undergraduates. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(3), 430–455. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon YM & Yip T (under review). Longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and discrimination among diverse adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Chickering A (1971). Culural sophistication and college experience. Educational Record, 52, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cokley K (2002). The impact of college racial composition on African American students’ academic self-concept: A replication and extension. Journal of Negro Education, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Cole D, & Zhou J (2014). Do diversity experiences help college students become more civically minded? Applying Banks’ multicultural education framework. Innovative Higher Education, 39(2), 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Cox TH, Lobel SA, & McLeod PL (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of management journal, 34(4), 827–847. [Google Scholar]

- Craig MA, & Richeson JA (2017). Hispanic population growth engenders conservative shift among non-Hispanic racial minorities. Social Psychological and Personality Science, [Google Scholar]

- Crystal DS, Killen M, & Ruck M (2008). It is who you know that counts: Intergroup contact and judgments about race-based exclusion. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 51–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K, Tropp LR, Aron A, Pettigrew TF, & Wright SC (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), 332–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner J, & Dalege J (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent–child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological bulletin, 139(6), 1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson N, & Chang MJ (2009). Racial diversity matters: The impact of diversity-related student engagement and institutional context. American Educational Research Journal, 46(2), 322–353. [Google Scholar]

- Denson N, & Zhang S (2010). The impact of student experiences with diversity on developing graduate attributes. Studies in Higher Education, 35(5), 529–543. [Google Scholar]

- Dodder RA, & Ogle NJ (1979). Increased Tolerance and Reference Group Shifts: A Test in the College Environment. Educational Research Quarterly, 4(3), 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty D (1992). A practice-centered model of organizational renewal through product innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, Yip T, & Shelton JN (2014). Intragroup contact and anxiety among ethnic minority adolescents: Considering ethnic identity and school diversity transitions. Journal of youth and adolescence, 43(10), 1628–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover TL, Major B, & Kaiser CR (2016). Members of high-status groups are threatened by pro-diversity organizational messages. Journal of experimental social psychology, 62, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, & Pribesh S (2004). When race matters: Teachers’ evaluations of students’ classroom behavior. Sociology of Education, 77(4), 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2008). The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 12(7), 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egalite AJ, Kisida B, & Winters MA (2015). Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 45, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ely RJ, & Thomas DA (2001). Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative science quarterly, 46(2), 229–273. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg ME, & Hurtado S (2011). Developing pluralistic skills and dispositions in college: Examining racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(4), 416–443. [Google Scholar]

- Enyeart Smith TM, Wessel MT, & Polacek GN (2017). Perceptions of Cultural Competency and Acceptance among College Students: Implications for Diversity Awareness in Higher Education. ABNF Journal, 28(2). [Google Scholar]

- Estlund C (2003). Working together: How workplace bonds strengthen a diverse democracy: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feddes AR, Noack P, & Rutland A (2009). Direct and extended friendship effects on minority and majority children’s interethnic attitudes: A longitudinal study. Child development, 80(2), 377–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, & Fenton RE (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 29(6), 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Flink IJ, Prins RG, Mackenbach JJ, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, … Raat H (2013). Neighborhood ethnic diversity and behavioral and emotional problems in 3 year olds: Results from the Generation R study. PloS one, 8(8), e70070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore R, Goldenberg CN, & Weisner TS (1993). The social construction and subjective reality of activity settings: Implications for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(4), 537–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child development, 67(5), 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Smith ME, & Brownell CA (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. Journal of school psychology, 41(4), 235–284. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith PA (2004). Schools’ role in shaping race relations: Evidence on friendliness and conflict. Social Problems, 51(4), 587–612. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Backen MA, Meca A, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Córdova D, Soto DW, … & Schwartz SJ (2018). Examining the temporal order of ethnic identity and perceived discrimination among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 54 (5), 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson NC, Panter AT, Daye CE, Allen WF, & Wightman LF (2009). The effects of educational diversity in a national sample of law students: Fitting multilevel latent variable models in data with categorical indicators. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(3), 305–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Munniksma A, & Juvonen J (2014). Psychosocial benefits of cross-ethnic friendships in urban middle schools. Child development, 85(2), 469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S, & Wormley WM (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of management journal, 33(1), 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP (1997). Biodiversity and ecosystem function: the debate deepens. Science, 277(5330), 1260–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin P (1999). Selections from the compelling need for diversity in higher education, expert reports in defense of the University of Michigan. Equity & Excellence, 32(2), 36–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin P, Dey E, Hurtado S, & Gurin G (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard educational review, 72(3), 330–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin P, Nagda BRA, & Lopez GE (2004). The benefits of diversity in education for democratic citizenship. Journal of social issues, 60(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin PY, Dey EL, Gurin G, & Hurtado S (2003). How Does Racial/Ethnic Diversity Promote Education? The Western Journal of Black Studies, 27(1), 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo RA, & Dickson MW (1996). Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annual review of psychology, 47(1), 307–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey SE, & Olson KR (2013). A social psychologist’s guide to the development of racial attitudes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(7), 457–469. [Google Scholar]

- Hall AR, Nishina A, & Lewis JA (2017). Discrimination, friendship diversity, and STEM-related outcomes for incoming ethnic minority college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Yip T, & Zárate MA (2016). On becoming multicultural in a monocultural research world: A conceptual approach to studying ethnocultural diversity. American Psychologist, 71(1), 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]