Abstract

Background

Thoracic bioreactance (TB), a noninvasive method for the measurement of cardiac output (CO), shows good test-retest reliability in healthy adults examined under research and resting conditions.

Objective

In this study, we evaluate the test-retest reliability of CO and cardiac power (CPO) output assessment during exercise assessed by TB in healthy adults under routine clinical conditions.

Methods

25 test persons performed a symptom-limited graded cycling test in an outpatient office on two different days separated by one week. Cardiorespiratory (power output, VO2peak) and hemodynamic parameters (heart rate, stroke volume, CO, mean arterial pressure, CPO) were measured at rest and continuously under exercise using a spiroergometric system and bioreactance cardiograph (NICOM, Cheetah Medical).

Results

After 8 participants were excluded due to measurement errors (outliers), there was no systematic bias in all parameters under all conditions (effect size: 0.2-0.6). We found that all noninvasively measured CO showed acceptable test-retest-reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.59-0.98; typical error: 0.3-1.8). Moreover, peak CPO showed better reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.80-0.85; effect size: 0.9-1.1) then the TB CO, thanks only to the superior reliability of MAP (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.59-0.98; effect size: 0.3-1.8).

Conclusion

Our findings preclude the clinical use of TB in healthy subject population when outliers are not identified.

Keywords: Cardiac Output; Cardiography, Impedance/methods; Exercise; Exercise Test/methods; Echocardiography/methods; Reproducibility of Results; Adult

Introduction

Cardiac output (CO) is an important physiological surrogate parameter, reflecting the hemodynamic demands of the organism. CO measuring has a wide application spectrum1 and can provide information on hemodynamic status in patients2 as well as athletes.3 In chronic heart failure, CO is decreased and patients suffer from exercise intolerance.4,5 In contrast, the athlete's heart shows structural and functional adaptations due to training6 resulting in a higher CO.7 Interestingly altered cardiac structure and function do not predict exercise intolerance8,9 or CO response3 in both cases. Thus, cardiopulmonary exercise testing is necessary and peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) is measured to determine exercise capacity.10,11 But, estimation of VO2 is influenced by several non-cardiac factors,4,12 and can, therefore, be misleading.9,13,14 Furthermore, CO cannot be accurately predicted from cardiopulmonary exercise testing.4,15

However, to evaluate hemodynamic status, catheter-based measuring (i.e., Fick method, thermodilution method) is considered as the clinical standard.16,17 Since such invasive methods are associated with high risk, their applicability is restricted.18,19 Therefore, noninvasive measuring methods (i.e., transoesophageal echocardiography, lithium dilution CO, pulse contour CO, partial CO2 rebreathing, thoracic electrical bioimpedance) were developed.17 Of the noninvasive measuring methods, especially the thoracic electrical bioimpedance was frequently used in clinical studies and evaluated for its reliability.20 However, thoracic bioreactance (TB) is a further promising technology to noninvasively monitor CO.21 TB is based on the measurement of blood flow-related phase shifts of transthoracic electric signals to monitor noninvasively and continuously CO. Therefore theoretically, TB is superior to other methods22,23 and has been used in several clinical settings.21,23-25 But, before TB can be adopted for clinical and performance decision making, test's quality criteria, as the test-retest reliability, must be fulfilled.

Jones et al.26 tested the test-retest reliability in a healthy study population. 22 healthy adults performed twice a symptom-limited exercise test. Standard cardiorespiratory data were measured via spiroergometry and the hemodynamic response was monitored via TB using the NICOM® system. The authors state that TB allows good test-retest reliability for hemodynamic measurement at rest as well as under submaximal and maximal exertion. This particular study was the first to confirm that TB might be a feasible test method. Noteworthy, the study was performed under tightly controlled research conditions. Overall, three visits were necessary to determine individual cardiorespiratory capability and to perform both exercise tests. Furthermore, to exclude confounders, certain inclusion criteria had to be fulfilled (e.g., non-smokers, empty stomach for > 2 h, no vigorous exercise 24 h before testing, no alcohol or caffeine consumption). Such scientific testing conditions are often difficult to guarantee in daily clinical routine. Thus, it remains unclear, if TB is an appropriate examination procedure not only in a research setting but also in daily clinical routine.

Contrary to CO based on heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV), cardiac power output (CPO) indicates the overall function of the heart.27 CPO is the product of the CO and mean arterial pressure (MAP) and therefore is a measure of cardiac pumping.28 Peak cardiac power output (CPOpeak), the CPO achieved during maximal stress, is a major determinant of exercise intolerance and performance in cardiac patients and healthy persons, respectively.29,30

Worth mentioning, CPO measuring can improve medical management31,32 and risk stratification33-35 in cardiac patients. In chronic heart failure, CPO is a powerful and independent predictor of survival outcome.35 CPO also reflects cardiovascular adaptions and training status in athletes.6 In fact, compared to non-athletes,36 CPO is higher in athletes.3,37 Thus, CPO might be an additive performance diagnostic parameter, which could help to guide training modalities.37,38 Like other established measures of exercise capacity, CPO cannot be predicted from resting cardiac parameters.3

Under this background, the aims of the present study were: 1) to evaluate the test-retest reliability of TB in healthy adults during the daily clinical routine, and 2) to assess the relationships between CPO and resting measures of cardiac structure and function as well as traditional cardiopulmonary exercise parameters. Here, we applied a progressive statistic approach to provide thresholds above which effects might be meaningful and to present CO and CPO values that may be used as reference values in future studies.

Methods

Participants

In the study, 25 test persons were included into the study. All participants had no history of cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases, no cardioactive medication, a blood pressure of ≤ 140/90 mmHg, a body mass index < 25, a normal electrocardiogram, and a normal echocardiogram at the time of inclusion.

Study design

This study is a prospective non-interventional diagnostic single-center study. Participants were recruited in a cardiologic and internal medicine facility. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Witten/Herdecke and written informed consent was obtained. A standard echocardiogram was performed to exclude structural heart diseases and to investigate the relationships between established echocardiographic parameters and cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic values. Heart size, wall thickness, systolic, and diastolic function were all in physiological limits. All participants underwent two cardiopulmonary exercise tests separated by on week. During testing, TB using the NICOMTM device was applied.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed to assess cardiac structure and function using a standard ultrasound system (Vivid 7, General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). A complete transthoracic study was performed, including 2D, M-mode, spectral, and color Doppler techniques according to current recommendations and guidelines.39,40 Standard parameters were: interventricular septal wall thickness in diastole, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole, and fractional shortening. Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured by means of modified biplane Simpson's method. Doppler tissue imaging was performed at the junction of the septal and lateral mitral annulus in apical 4-chamber view to determine peak mitral annular velocity during early filling (E`) and the ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity (V).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

A symptom-limited incremental exercise test was performed in a seated position on a cycling ergometer (ec-3000, customed GmbH, Germany). The tests were performed by trained personal. After 5 min of rest, participants started at 0 W and the workload increased every 2 min by 25 W (standard WHO protocol). HR, blood pressure on the right arm using a sphygmomanometer, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram were obtained at rest and each stage as well as for 3 min post-exercise. The respiratory gas analysis was performed using a spiroergometry system (Cortex Metalyzer® 3B, Leipzig, Germany, software Metasoft studio 5.1.2 SR1). Ventilatory oxygen consumption and standard gas exchange data were measured breath-by-breath and averaged over 30 s. The following standard parameters were measured: Time to exhaustion, maximum workload, ventilatory anaerobic threshold (VAT) and peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak). The anaerobic threshold was determined using the V-slope method.41 The submaximal load was determined as the second last completed incremental. VO2peak was defined as the highest VO2 observed during testing.

Thoracic bioreactance

TB (NICOM®, Cheetah Medical, Portland, Oregon, USA) was added for noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring during rest and exercise. The examination was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, as described previously.2,21,42 Table 1 shows the parameters that were calculated by the Cheetah NICOM® system. The NICOM® system uses four sensors applied to the right and left sides of the chest. Each sensor consists of an outer transmitting electrode and an inner receiving electrode. The outer electrodes transmit a low amplitude alternating electrical current with a frequency of 75 kHz to the thoracic cavity. The electrical properties of the thorax cyclically change due to the pulsatile volume of blood ejected from the heart. The pulsatile blood flow in the large thoracic arteries causes time delays (phase shifts) between the applied alternating electrical current and the thoracic voltage measured by the inner electrodes. Based on the measured phase shift the maximum aortic flow (dX/dtmax) and the ventricular ejection time (time from aortic valve opening to aortic valve closure, VET) were measured. Finally, the SV was obtained as SV = DX/DT × VET. Thereon, the CO, and finally the CPO, was derived.43 The SV data were measured beat-by-beat and averaged over 60 s.

Table 1.

Parameters calculated by the Cheetah NICOM® system

| Parameter | Equation | measuring unit |

|---|---|---|

| Stroke Volume (SV) | ml/beat | |

| Stroke Volume Index | ml/m2/beat | |

| Cardiac Output (CO) | l/min | |

| Cardiac Index (CI) | l/min/m2 | |

| Mean arterial pressure (MAP) | mmHg | |

| Total Peripheral Resistance | dynes x sec/cm5 | |

| Total Peripheral Resistance Index | dynes x sec/cm5/m2 |

HR: heart rate; BSA: body surface area; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

Statistical analysis

In a first step, participants were excluded from statistical analyses due to measurement errors (outliers), which were defined as ≥mean ± twofold pooled standard deviation.44

The test-retest reliability of cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic parameters was analyzed by (1) the difference in means to detect systematic bias, (2) intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) to examine the relative reliability, and (3) typical error (TE) of measurements to quantify the absolute reliability.45 To examine the difference in means, a progressive statistical approach using magnitude-based inferences for practical significance were computed.46 Compared to traditional null-hypothesis testing, that is influenced by the sample size, magnitude-based inferences ground an analysis, how big the observed effect is, and if the effect is lower, similar, or higher than the smallest worthwhile difference (SWD).46 Therefore, means and 90% confidence intervals (CIs) was computed first. Then, the disposition of the mean differences in relation to the SDWs were investigated. While the SDW for the maximal workload was calculated from the pooled standard deviation multiplied by 0.2, the SWD for all other physiological variables were calculated from the pooled standard deviations multiplied by 0.6, because it is well known that physiological variables showed a clearly higher spontaneous variability than biomechanical measures.47 Finally, the likelihoods for test 2 showing “true” higher, similar, or lower values than test 1 were determined and qualitatively described using the following probabilistic scale: <1%, most unlikely; 1 to <5%, very unlikely; 5 to <25%, unlikely; 25 to <75%, possibly; 75 to <95%, likely; 95 to <99%, very likely, and ≥99%, most likely. If the likelihoods for having both higher and lower values were ≥5%, the differences were described as unclear. Otherwise, the differences were interpreted according to the observed likelihoods. To clarify the meaningfulness of the differences, standardized differences labeled as effect sizes (ESs) were calculated and interpreted accordingly: 0.2 to <0.6, small; 0.6 to <1.2, moderate; 1.2 to <2.0, large; 2.0 to <4.0, very large; and ≥4.0, extreme large. To express the relative reliability, ICCS and 90% CIs were computed. The coefficients were described as follows: <0.20, very low; 0.20 to <0.50, low; 0.50 to <0.75, moderate; 0.75 to <0.90, high; 0.90 to <0.99, very high; and ≥0.99, extremely high. To quantify the absolute reliability, TEs and 90% CIs were calculated. The meaningfulness of the TEs was expressed via standardization for which the aforementioned scale for standardized differences was applied.47

The relationships between the CPO and measures of cardiac structure and function as well as traditional cardiopulmonary exercise parameters were investigated using Pearson correlation coefficients (r) that were interpreted accordingly: <0.1, trivial; 0.1 to <0.3, small, 0.3 to <0.5, moderate; 0.5 to <0.7, large; 0.7 to <0.9, very large; 0.9 to 1.0, almost perfect. 47 Lastly, common variances from coefficients of determinations (R2) were computed. Thereby, a cutting-off value of 50% was defined to clarify, if two variables are dependent or independent from each other.48

Results

25 participants completed both exercise tests. 17 participants (10 male, 7 female) were finally included. 8 participants were excluded due to measurement errors (outliers). Anthropometric, echocardiographic, and spiroergometric data of the participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Anthropometric, echocardiographic, and maximal exercise characteristics of the participants (male: n = 10; female: n = 7)

| Variable | Mean ± 90% CI |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46 ± 1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9 ± 0.9 |

| IVSd (mm) | 9.6 ± 0.5 |

| LVed (mm) | 46.9 ± 1.8 |

| PLWd (mm) | 9.9 ± 0.5 |

| FS (%) | 26.9 ± 2.0 |

| EF (%) | 66.0 ± 2.2 |

| E´ (cm/s) | 9.9 ± 1.1 |

| E/E´ | 8.5 ± 1.3 |

| Tlim (min:s) | 19:42 ± 4:39 |

| Pmax (W) | 187 ± 23 |

| VO2peak (ml/min/kg) | 33 ± 4 |

| VAT (%VO2peak) | 60.7 ± 4.0 |

CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; IVSd: interventricular septal diastole; LVed: left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; PLWd: left ventricular posterior wall thickness; FS: fractional shortening; EF: ejection fraction; E': peak mitral annular velocity during early filling; E/E`: ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity; Tlim: time to exhaustion; Pmax: maximum workload; VO2peak: peak oxygen uptake; VAT: ventilatory anaerobic threshold.

Reliability

Data concerning systematic bias are presented in Table 3. It shows the differences in means between test 1 and test 2 for all hemodynamic and cardiopulmonary parameters measured at rest and during submaximal and peak exercise conditions. For all parameters, there were unclear to very likely trivial differences with small to moderate ESs (ES: 0.2-0.6).

Table 3.

Changes in means of the resting, submaximal and maximal hemodynamic and cardiorespiratory characteristics

| Variable | Test 1 |

Test 2 |

Bias |

SWD | Likelihood (%) for Bias beeing higher/trivial/lower than SWD | ES ± 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± 90% CI | Mean ± 90% CI | Mean ± 90% CI | ||||

| Rest | ||||||

| CPO (W) | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.1 | 11.3/77.4/11.3 (unclear) | 0.2 ± 0.3 (small) |

| CO (l/min) | 5.61 ± 0.30 | 6.04 ± 0.31 | +0.43 ± 0.19 | 0.47 | 43.6/56.4/0.0 (possibly trivial) | 0.6 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| SV (ml) | 83 ± 6 | 87 ± 7 | +4 ± 3 | 10 | 13.2/86.2/0.6 (likely trivial) | 0.3 ± 0.2 (small) |

| HR (1/min) | 71 ± 4 | 74 ± 5 | +3 ± 2 | 7 | 15.1/84.4/0.5 (likely trivial) | 0.3 ± 0.2 (small) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 96 ± 4 | 92 ± 4 | -4 ± 3 | 6 | 8.5/53/38.5 (unclear) | 0.2 ± 0.2 (small) |

| Submaximal | ||||||

| CPO (W) | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | -0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.7 | 9.1/89.9/1.0 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.3 (small) |

| CO (l/min) | 13.95 ± 1.23 | 13.66 ± 1.04 | -0.29 ± 1.07 | 1.77 | 1.6/92.5/5.9 (likely trivial) | 0.1 ± 0.5 (small) |

| SV (ml) | 100 ± 7 | 100 ± 8 | -1 ± 6 | 12 | 2.9/94.2/2.9 (likely trivial) | 0.1 ± 0.4 (small) |

| HR (1/min) | 133 ± 10 | 131 ± 10 | -3 ± 2 | 15 | 2.4/91.1/6.5 (likely trivial) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (small) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 115 ± 6 | 112 ± 6 | -3 ± 1 | 9 | 0.8/90.7/8.5 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.1 (small) |

| Maximal | ||||||

| CPO (W) | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | -0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.7 | 11.3/87.0/1.7 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.3 (small) |

| CO (l/min) | 16.09 ± 1.31 | 15.51 ± 1.28 | -0.58 ± 1.01 | 2.01 | 1.0/89.9/9.1 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.4 (small) |

| SV (ml) | 98 ± 9 | 95 ± 10 | -3 ± 7 | 14 | 1.7/90.1/8.2 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.4 (small) |

| HR (1/min) | 164 ± 7 | 161 ± 7 | -3 ± 3 | 11 | 1.0/89.9/9.1 (likely trivial) | 0.2 ± 0.2 (small) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 123 ± 6 | 122 ± 6 | -1 ± 4 | 9 | 1.8/94.2/4.0 (likely trivial) | 0.1 ± 0.3 (small) |

| P (W) | 187 ± 23 | 190 ± 25 | +3 ± 6 | 38 | 3.2/95.0/1.8 (very likely trivial) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (small) |

| VO2 (l/min) | 2.40 ± 0.27 | 2.39 ± 0.29 | -0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.43 | 3.1/93.2/3.7 (likely trivial) | 0.0 ± 0.1 (small) |

CI: confidence interval; SWD: smallest worthwhile differences; ES: effect size; CPO: cardiac power output; CO: cardiac output; SV: stroke volume; HR: heart rate; MAP: mean aterial pressure; P: workload; VO2: oxygen uptake.

Table 4 summarizes the relative and absolute reliability expressed by ICCs and TEs, respectively, for all measured parameters. The ICCS ranged from moderate (ICC: 0.59) to very high (ICC: 0.98), whereas the TEs ranged from small (ES: 0.3) to large (ES: 1.8). CPO demonstrated superior relative and absolute reliability under all measurement conditions (ICC: 0.80-0.85; ES: 0.9-1.1) than its underlying parameters (ICC: 0.59-0.98; ES: 0.3-1.8).

Table 4.

Relative (ICC) and absolute reliability (TE) of the resting, submaximal, and maximal cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic characteristics

| Variable | Relative Reliability | Absolute Reliability (SI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICC ± 90% CI | TE ± 90% CI | ES ± 90% CI | |

| Rest | |||

| CPO (W) | 0.80 ± 0.16 (high) | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| CO (l/min) | 0.83 ± 0.14 (high) | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 1.0 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| SV (ml) | 0.92 ± 0.07 (very high) | 5 ± 1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 (moderate) |

| HR (1/min) | 0.91 ± 0.08 (very high) | 4 ± 1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 (moderate) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0.91 ± 0.08 (very high) | 6 ± 2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 (moderate) |

| Submaximal | |||

| CPO (W) | 0.85 ± 0.13 (high) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| CO (l/min) | 0.59 ± 0.28 (moderate) | 1.89 ± 0.60 | 1.8 ± 0.6 (large) |

| SV (ml) | 0.75 ± 0.19 (high) | 10 ± 3 | 1.2 ± 0.4(large) |

| HR (1/min) | 0.97 ± 0.03 (very high) | 4 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 (small) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0.98 ± 0.02 (very high) | 2 ± 1 | 0.3 ± 0.1(small) |

| Maximal | |||

| CPO (W) | 0.82 ± 0.15 (high) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| CO (l/min) | 0.73 ± 0.20 (moderate) | 1.78 ± 0.57 | 1.3 ± 0.4 (large) |

| SV (ml) | 0.75 ± 0.19 (high) | 12 ± 4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 (large) |

| HR (1/min) | 0.91 ± 0.08 (very high) | 6 ± 2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 (moderate) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0.82 ± 0.15 (high) | 6 ± 2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 (moderate) |

| P (W) | 0.97 ± 0.03 (very high) | 11.2 ± 3.6 | 0.4 ± 0.1 (small) |

| VO2 (l/min) | 0.97 ± 0.03 (very high) | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.1 (small) |

ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; CI: confidence interval; TE: typical error; ES: effect size; CV: coefficient of variation; CPO: cardiac power output; CO: cardiac output; SV: stroke volume; HR: heart rate; MAP: mean arterial pressure; P: workload; VO2: oxygen uptake.

Relationships

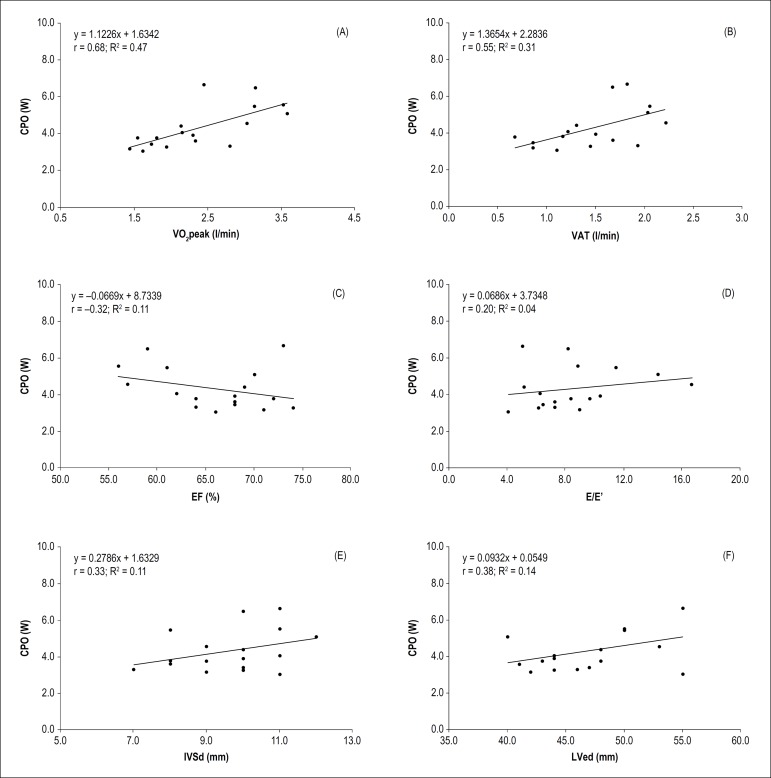

Figure 1 shows the relationships between echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure and function, traditional cardiopulmonary exercise parameters, and peak CPO. The peak CPO correlated moderately with VO2peak (Figure 1A: r = 0.68; R2= 0.47) and VAT (Figure 1B: r = 0.55; R2= 0.31), but only small with left ventricular wall thickness (Figure 1E: r = 0.33; R2= 0.11), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (Figure 1F: r = 0.38; R2= 0.14), and systolic (Figure 1C: r = -0.32; R2= 0.11) as well as trivial with diastolic function (Figure 1D: r = 0.20; R2= 0.04).

Figure 1.

Relationships between the CPO and established cardiorespiratory and echocardiographic characteristics. CPO: cardiac power output; VO2peak: peak oxygen uptake; VAT: ventilatory anaerobic threshold; EF: ejection fraction; E/E‘: ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity; r: Pearson correlation coefficient; R2: coefficient of determination.

Discussion

Our main findings were: (1) there were no systematic bias for all measured parameters during all conditions, (2) all noninvasively measured hemodynamic parameters showed small to large test-retest-reliability, whereas the CPOpeak demonstrated a superior reliability than its underlying parameters, and (3) CPO was independent of measures of cardiac structure and function as well as traditional cardiopulmonary exercise parameters.

Our first finding was that there was no systematic bias during all examination conditions. These outcomes are in line with further studies, investigating hemodynamic and cardiopulmonary exercise parameters.26,49 Overall, in our study, systematic bias due to learning, subject motivation, and fatiguing effects as well as errors in calibration procedures can be excluded.45,50 This assumption supports our research design.

The second major finding was that all noninvasively measured hemodynamic parameters showed an acceptable test-retest reliability during rest, submaximal, and maximal exertion. Jones et al.26 first showed a good test-retest reliability of TB in a healthy population at rest as well as during submaximal and maximal exertion. However, acceptable test-retest reliability was impacted by the fact that we have previously excluded a significant number of outliers (n = 8) due to measurement errors. It is further noteworthy that the reliability of our TB measurements was to some degree inferior compared to a previous study in which the reliability of a comparable technology (beat by beat signal morphology impedance cardiography) to evaluate the hemodynamic response was assessed.20 One possible explanation for the differences may be that we investigated the reliability under less standardized conditions, another one could be related to significant technological differences.

Overall, when outliers are excluded, TB can be considered as an appropriate technology to not only assess hemodynamic status in a research setting but also in everyday practice.

The central task of the heart is to produce a sufficient CO and maintain an adequate MAP. Therefore, cardiac performance can be best explained by CPO, because it takes both the flow- and pressure-generating capacities of the heart into account.29

In chronic heart failure, the application of hemodynamic measuring to standard cardiopulmonary exercise testing may help to explain the underlying mechanism of exercise intolerance with impact on clinical decision making,31 therapy planning, and performance32 as well as risk stratification.51 Chomsky et al.31 showed that CO respond to exercise is a strong predictor of mortality in cardiac transplantation candidates. In addition, Lang et al.35 demonstrated CPO as the most powerful and independent predictor of survival chronic heart failure outcome in patients with chronic heart failure and that may enhance the prognostic power of traditional cardiopulmonary exercise testing.

In sports medicine, monitoring of the training status is essential to guide the training process. Training leads to significant structural and functional changes of the cardiovascular system.6 In a randomized cross-over study, Marshall et al.38 assessed the effect of moderate exercise training on cardiac performance in non-athletic adults. Due to training, the CPOpeak increased by 16%, whereas the CPO at rest remained unchanged. In highly trained endurance athletes, Schlader et al.37 found double CPOpeak values compared to non-athletes. These results have been confirmed by Klasnja et al.3 in football and basketball players.

In our study, the CPOpeak showed superior reliability than the underlying physiological single parameters. However, it should be noted that the reliability of the CPO was potentially influenced by the reliability of the MAP (which was higher) rather than that of the SV and CO (which were lower). Thus, CPO measuring by TB seems to be feasible due to its surrogate character. It is, however, important to mention that we have averaged all our beat-by-beat measured TB data, including the CPO, over 60 s, which might have also artificially improved our statistical outcomes. The reason for our data processing method was that we aimed to investigate the global cardiac performance. Such a data processing proceed is of course inadequately, when aiming to assess transient cardiac abnormalities during exercise like ischemia. Since the beat-by-beat reliability of our TB based measures remains unknown, we recommend other impedance-based technologies, which offer a reliable beat-by-beat analysis of hemodynamic parameters during exercise.20

The third major finding was that CPO was found to be independent of cardiac structure and function at rest as well as to traditional cardiopulmonary exercise parameters. Klasnja et al.3 previously demonstrated a weak correlation between CPOpeak and resting parameters of left ventricular morphology and function.3 We also did not find a strong relation between CPOpeak and echocardiographic findings at rest. Our findings show once again that resting parameters cannot be used to estimate maximal cardiovascular performance.

For the first time driven by our progressive statistics,47 we report the SWDs for all investigated TB parameters. From a practical point of view, the provided thresholds can be used as a framework to judge in healthy adults, whether observed differences in the analyzed parameters should be interpreted or not in a daily medical routine. Further, it is promising to use these thresholds as cutting-off values for minimal required effects detected by longitudinal or cross-sectional studies using the here investigated TB measures in the future. For example, in healthy adults, the calculated SWD of the CPO was 0.7 W, meaning that longitudinal or cross-sectional differences should only be interpreted, when this cut-off value is exceeded.

The major limitation of our study is the high dropout rate (n=8). However, to detect outliers, we objectively defined them as those values, which were greater than the pooled standard deviation. Based on this approach and our recruited healthy adults, it can be assumed that the detected outliers had not a physiological cause. Contrary, it is more likely that the identified outliers had rather an underlying technical reason. Therefore, further improvements in TB, for example, regarding the application and quality of electrodes are required. Consequently, technical errors must be executed by proprietary algorithms, before valid decisions are possible. When taken these aspects together, our findings indicate that TB can only be considered as a reliable technology for measuring hemodynamic parameters after outliers have been excluded.

Conclusion

In conclusion, at this stage, our results preclude the clinical use of TB in healthy subject population when outliers are not identified even if a previous study seem to show its possible application in a strictly controlled research setting.

Footnotes

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by Bayer Pharma.

Study Association

This article is part of the thesis of Doctoral submitted by Christian Kiefer, from University Hospital Witten/Herdecke.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Witten/Herdecke under the protocol number 131/2914. All the procedures in this study were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, updated in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Coll MT, Dinh W; Acquisition of data: Coll MT, Kiefer C, Dinh W; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Hoppe MW, Dinh W; Statistical analysis: Hoppe MW; Obtaining financing: Krahn T, Mondritzki T, Dinh W; Writing of the manuscript: Coll MT, Hoppe MW, Boehme P, Dinh W; Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Coll MT, Boehme P, Krahn T, Kiefer C, Kramer F, Mondritzki T, Pirez P.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jhanji S, Dawson J, Pearse RM. Cardiac output monitoring: basic science and clinical application. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(2):172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers J, Gujja P, Neelagaru S, Burkhoff D. Cardiac output and cardiopulmonary responses to exercise in heart failure: application of a new bio-reactance device. J Card Fail. 2007;13(8):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klasnja AV, Jakovljevic DG, Barak OF, Popadic Gacesa JZ, Lukac DD, Grujic NG. Cardiac power output and its response to exercise in athletes and non-athletes. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2013;33(3):201–205. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers J, Froelicher VF. Hemodynamic determinants of exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):377–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan MJ, Knight JD, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Relation between central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: Muscle blood flow is reduced with maintenance of arterial perfusion pressure. Circulation. 1989;80(4):769–781. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovacs R, Baggish AL. Cardiovascular adaptation in athletes. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rerych SK, Scholz PM, Sabiston DC, Jr., Jones RH. Effects of exercise training on left ventricular function in normal subjects: a longitudinal study by radionuclide angiography. Am J Cardiol. 1980;45(2):244–252. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franciosa JA, Park M, Levine TB. Lack of correlation between exercise capacity and indexes of resting left ventricular performance in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1981;47(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JR, Rayos G, Yeoh TK, Gothard P, Bak K. Dissociation between exertional symptoms and circulatory function in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92(1):47–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers J. Applications of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the management of cardiovascular and pulmonary disease. Int J Sports Med. 2005 Feb;26(Suppl 1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang CC, Agostoni P, Mancini DM. Prognostic significance and measurement of exercise-derived hemodynamic variables in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;13(8):672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becklake MR, Frank H, Dagenais GR, Ostiguy GL, Guzman CA. Influence of age and sex on exercise cardiac output. J Appl Physiol. 1965;20(5):938–947. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1965.20.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JR, Rayos G, Yeoh TK, Gothard P. Dissociation between peak exercise oxygen consumption and hemodynamic dysfunction in potential heart transplant candidates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(2):429–435. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)80018-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicoletti I, Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Franceschini L, Brighetti G, Pilati M, et al. Skeletal muscle abnormalities in chronic heart failure patients: relation to exercise capacity and therapeutic implications. Congest Heart Fail. 2003;9(3):148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lund-Johansen P. The dye dilution method for measurement of cardiac output. Eur Heart J. 1990 Dec;11(Suppl I):6–12. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/11.suppl_i.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warburton DE, Haykowsky MJ, Quinney HA, Humen DP, Teo KK. Reliability and validity of measures of cardiac output during incremental to maximal aerobic exercise. Part II: Novel techniques and new advances. Sports Med. 1999;27(4):241–260. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandham JD, Hull RD, Brant RF, Knox L, Pineo GF, Doig CJ, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):5–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey S, Stevens K, Harrison D, Young D, Brampton W, McCabe C, et al. An evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in patient management in intensive care: a systematic review and a randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(29):iii-iv, ix-xi. doi: 10.3310/hta10290. 1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon N, Abbiss CR, Maiorana AJ, Marstron KJ, Peiffer JJ. Intrarater reliability and agreement of the physioflow bioimpedance cardiography device during rest, moderate and high-intensive exercise. Kinesiology. 2018;50(1 Suppl 1):140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurer MM, Burkhoff D, Maybaum S, Franco V, Vittorio TJ, Williams P, et al. A multicenter study of noninvasive cardiac output by bioreactance during symptom-limited exercise. J Card Fail. 2009;15(8):689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keren H, Burkhoff D, Squara P. Evaluation of a noninvasive continuous cardiac output monitoring system based on thoracic bioreactance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(1):H583–H589. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00195.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakovljevic DG, Moore S, Hallsworth K, Fattakhova G, Thoma C, Trenell MI. Comparison of cardiac output determined by bioimpedance and bioreactance methods at rest and during exercise. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26(2):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s10877-012-9334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marik PE, Levitov A, Young A, Andrews L. The use of bioreactance and carotid Doppler to determine volume responsiveness and blood flow redistribution following passive leg raising in hemodynamically unstable patients. Chest. 2013;143(2):364–370. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott A, Hull JH, Nunan D, Jakovljevic DG, Brodie D, Ansley L. Application of bioreactance for cardiac output assessment during exercise in healthy individuals. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(5):945–951. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones TW, Houghton D, Cassidy S, MacGowan GA, Trenell MI, Jakovljevic DG. Bioreactance is a reliable method for estimating cardiac output at rest and during exercise. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(3):386–391. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan LB. Evaluation of cardiac dysfunction, cardiac reserve and inotropic response. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67(Suppl 1):S10–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotter G, Williams SG, Vered Z, Tan LB. Role of cardiac power in heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2003;18(3):215–222. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan LB. Clinical and research implications of new concepts in the assessment of cardiac pumping performance in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1987;21(8):615–622. doi: 10.1093/cvr/21.8.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooke GA, Marshall P, al-Timman JK, Wright DJ, Riley R, Hainsworth R, et al. Physiological cardiac reserve: development of a non-invasive method and first estimates in man. Heart. 1998;79(3):289–294. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chomsky DB, Lang CC, Rayos GH, Shyr Y, Yeoh TK, Pierson 3rd RN, et al. Hemodynamic exercise testing. A valuable tool in the selection of cardiac transplantation candidates. Circulation. 1996;94(12):3176–3183. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson JR, Groves J, Rayos G. Circulatory status and response to cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1996;94(7):1567–1572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grodin JL, Mullens W, Dupont M, Wu Y, Taylor DO, Starling RC, et al. Prognostic role of cardiac power index in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(7):689–696. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams SG, Cooke GA, Wright DJ, Parsons WJ, Riley RL, Marshall P, et al. Peak exercise cardiac power output; a direct indicator of cardiac function strongly predictive of prognosis in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(16):1496–1503. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang CC, Karlin P, Haythe J, Lim TK, Mancini DM. Peak cardiac power output, measured noninvasively, is a powerful predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(1):33–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.798611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bromley PD, Hodges LD, Brodie DA. Physiological range of peak cardiac power output in healthy adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2006;26(4):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2006.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlader ZJ, Mundel T, Barnes MJ, Hodges LD. Peak cardiac power output in healthy, trained men. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2010;30(6):480–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall P, Al-Timman J, Riley R, Wright J, Williams S, Hainsworth R, et al. Randomized controlled trial of home-based exercise training to evaluate cardiac functional gains. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101(5):477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evangelista A, Gaudio C, De Castro S, Faletra F, Nesser HJ, Kuvin JT, et al. Three-dimensional echocardiography--state-of-the-art. Indian Heart J. 2008;60(3 Suppl C):C3–C9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoppe MW, Sperlich B, Baumgart C, Janssen M, Freiwald J. Reliability of selected parameters of cycling ergospirometry from the powercube-ergo respiratory gas analyser. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2015;29(3):173–179. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raval NY, Squara P, Cleman M, Yalamanchili K, Winklmaier M, Burkhoff D. Multicenter evaluation of noninvasive cardiac output measurement by bioreactance technique. J Clin Monit Comput. 2008;22(2):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10877-008-9112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, Menon V, Slater JN, Webb JG, et al. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(2):340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vickery WM, Dascombe BJ, Baker JD, Higham DG, Spratford WA, Duffield R. Accuracy and reliability of GPS devices for measurement of sports-specific movement patterns related to cricket, tennis, and field-based team sports. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(6):1697–1705. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000;30(1):1–15. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batterham AM, Hopkins WG. Making meaningful inferences about magnitudes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2006;1(1):50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hopkins WG, Marshall SW, Batterham AM, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(1):3–13. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas JR, Nelson JK, Silverman SJ. Research methods in physical activity. Champaign: Human Kinectcs; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squara P, Denjean D, Estagnasie P, Brusset A, Dib JC, Dubois C. Noninvasive cardiac output monitoring (NICOM): a clinical validation. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(7):1191–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26(4):217–238. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metra M, Faggiano P, D'Aloia A, Nodari S, Gualeni A, Raccagni D, et al. Use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing with hemodynamic monitoring in the prognostic assessment of ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(4):943–950. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00672-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]