Abstract

Delivery technologies for the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system often require viral vectors, which pose safety concerns for therapeutic genome editing1. Alternatively, cationic liposomal components or polymers can be used to encapsulate multiple CRISPR components into large particles (typically >100 nm diameter); however, such systems are limited by variability in loading of the cargo. Here, we report the design of customizable synthetic nanoparticles for the delivery of Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), enabling controlled stoichiometry of CRISPR components and limiting possible safety concerns in vivo. We describe the synthesis of a thin glutathione (GSH)-cleavable covalently-crosslinked polymer coating, called a nanocapsule (NC), around a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex between a Cas9 nuclease and a sgRNA. The NC is synthesized by acrylate-based polymerization, has a hydrodynamic diameter of 25 nm, and can be customized via facile surface modification. NCs efficiently generate targeted gene edits in vitro without any apparent cytotoxicity. Furthermore, NCs produce robust gene editing in vivo in murine retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tissue and skeletal muscle following local administration. This customizable NC nanoplatform efficiently delivers CRISPR RNP complexes for in vitro and in vivo somatic gene editing.

Cas9 RNP is an attractive nonviral formulation for CRISPR-mediated gene editing due to its quick DNA cleavage activity, low off-target effects1, 2, low risk of insertional mutagenesis, and ease of production3. Furthermore, RNPs do not rely on transcriptional or translational cellular machinery for precise enzymatic gene editing activity, nor carry any long nucleic acids or viral based approaches that could integrate into the genome. However, existing nonviral strategies for the delivery of Cas9 RNP face a number of challenges4, 5, 6, 7, such as high cytotoxicity, poor in vivo stability, large particle sizes, lack of specific tissue/cell-targeting abilities, variable loading of the RNP cargo, and potential immunogenicity. These challenges limit the application of RNPs for gene editing in vitro, and especially in vivo where chemically-defined stable and off-the-shelf formulations could be critical for translational somatic gene editing applications1.

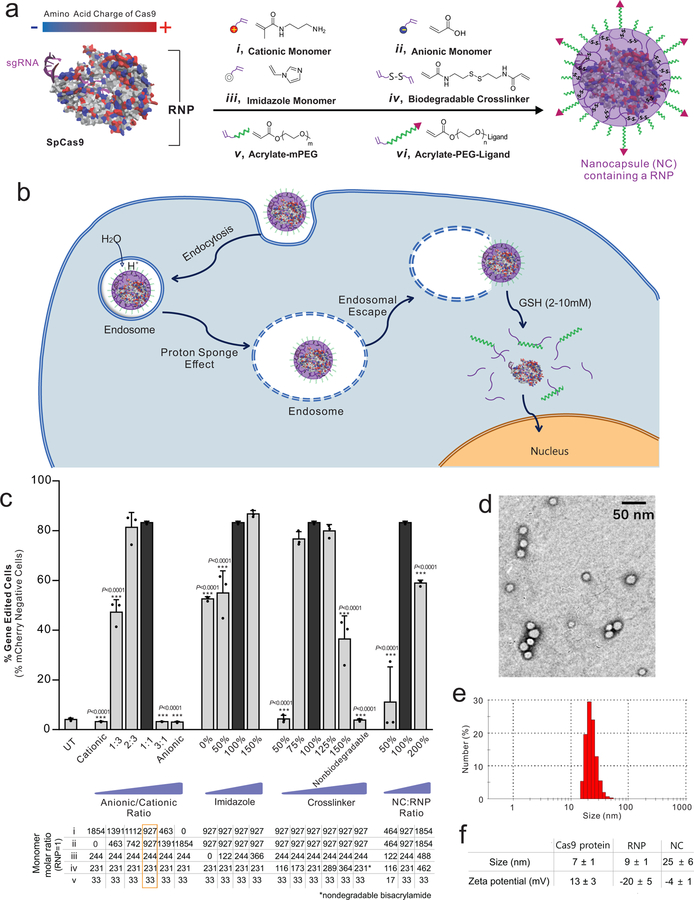

We sought to develop a customizable and efficient nanoplatform to deliver Cas9 RNP complexes for both in vitro and in vivo applications. Our design criteria include: high RNP loading content; small nanoparticle sizes; controllable stoichiometry; excellent stability; endosomal escape capability; efficient RNP release once inside the cytosol; and, amenability to surface modifications. As shown in Fig. 1a, because the RNP exhibits heterogeneous surface charges on the Cas9 protein and sgRNA5, we posited that a mixture of cationic and anionic acrylate monomers (i and ii, respectively) could form a coating around the RNP through electrostatic interactions. An imidazole-containing monomer (iii), GSH-degradable crosslinker (iv), acrylate mPEG (v), and acrylate PEG conjugated ligands (vi) can also be attracted to the surface of the RNP complex via hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions8, 9. After monomer coating, subsequent in situ free-radical polymerization8, 9, 10 was initiated to form a covalently linked, yet glutathione (GSH)-cleavable NC around RNP. The integration of the imidazole-containing acrylate monomer can facilitate endosomal escape of the NCs owing to the proton sponge effect of imidazole groups11. NCs were crosslinked with a GSH-cleavable linker, N,N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine, which can be degraded in GSH-rich environments such as the cytosol (2–10 mM12, 13), thereby enabling the release of RNPs within the cytosol (Fig. 1b). The RNPs can then enter the nucleus, which may be further facilitated by nuclear localization signals (NLSs) fused to the recombinant Cas9 protein14. The outer water-soluble PEG shell adds flexibility to conjugate functional moieties, such as targeting ligands, cell penetrating peptides (CPPs), or imaging probes.

Figure 1 |. Design, synthesis, and optimization of nanocapsules (NCs).

a, Sp.Cas9 has a heterogeneous surface charge due to both positive and negative amino acids residues, as well as the negatively charged sgRNA. A schematic illustration for the formation of the covalently-crosslinked, yet intracellularly biodegradable, NC for the delivery of the Cas9 RNP complex prepared by in situ free radical polymerization. b, A schematic depiction of the proposed mechanism of the cellular uptake of NCs and the subcellular release of RNP. c, Optimizing the formulation of the NCs in vitro using mCherry-expressing HEK 293 cells. HEK 293 cells were treated with various formulations of the NCs with an sgRNA targeting mCherry for six days. The loss of mCherry fluorescence was measured via flow cytometry to assay editing efficiency. Formulations investigated are listed below. The optimal NC formulation is highlighted by a black bar and its composition is shown in the orange square. To simplify reading the chart, the parameters being optimized (i.e., imidazole, crosslinker, and NC:RNP ratio) are shown relative to the value of the same component in the optimal formulation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). d, Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of NCs. Experiments were repeated three times. e, Dynamic light scattering (DLS) plots of NCs. Experiments were repeated three times. f, Summary of the size and zeta potential of Cas9 protein, Cas9 RNP, and NC. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). Statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To find optimal monomer stoichiometry for efficient cellular transfection, the amounts of various monomers were adjusted systematically as summarized in Fig. 1c. Several critical factors were investigated, including the anionic/cationic monomer ratio, the amounts of the imidazole-containing monomer and crosslinker, and the mass ratio between the NC and RNP. The functionality of NCs with different formulations were tested on a human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line with an H2B-mCherry transgene (red fluorescence localized to each nucleus)15, 16. Using a suitable sgRNA targeting the mCherry transgene, successful gene editing results in a loss of red fluorescence that is easily detectable through flow cytometry.

It is essential to use both cationic and anionic monomers due to the heterogeneous charge distribution of RNP (Fig. 1c). Pure cationic or anionic monomer formulations exhibited negligible gene editing, likely due to incomplete coating of the RNP. The ratios of anionic and cationic monomers also affected the gene editing efficiency. The formulation containing a mixture of cationic and anionic monomers at an anionic/cationic ratio of 1:1 (the optimal formulation) exhibited the highest gene editing levels (Fig. 1c). The amounts of the imidazole monomer and biodegradable crosslinker were also critical for efficient gene editing (Fig. 1c). Without imidazole-containing monomers, NCs induced relatively low levels of gene editing. Higher editing efficiencies were achieved with increases in imidazole-containing monomers. Also, at a low crosslinker amount, no gene editing was observed, likely due to unsuccessful formation of NCs. With sufficient amounts of crosslinker, similar gene editing capabilities were detected, suggesting a minimum required threshold for crosslinker to successfully form NCs. Higher crosslinker concentrations caused a reduction in gene editing efficiency. Furthermore, NCs formed by a non-biodegradable crosslinker (bisacrylamide) showed no editing, indicating that NCs must be biodegradable in order to produce gene edits. The mass ratios between the NC and RNP impacted gene editing efficiencies, as sufficient acrylate monomers are needed to form a polymer coating around RNP. NCs with a low NC:RNP ratio (50% of the optimal formulation) exhibited gene editing efficiencies barely above the baseline (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, excessive polymer coating over RNP (200% of the optimal formulation) also reduced the editing efficiency, likely attributed to the fact that NCs with a thicker polymeric shell require a longer time to fully degrade and release RNP to function. Collectively, the critical range for functional encapsulation of RNPs was determined after systematically titrating all key components, and the optimal NC formulation (referred to as NC subsequently) was selected for further study. The RNP loading level of the optimal NC was 40%. Fig. 1d shows a transmission electron microscope image of uniformly sized NCs with an average diameter of 16 nm. The average hydrodynamic diameter of NCs was 25 nm measured by dynamic light scattering (Fig. 1e). The zeta potential of NCs was relatively neutral (i.e., –4 mV), indicating that the net negative charge of the RNP was masked by the NC (Fig. 1f).

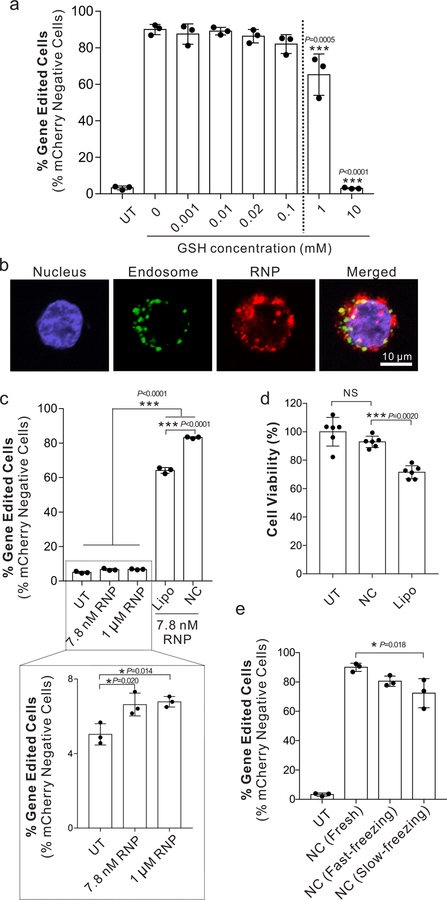

The stability of NCs before cell internalization is critical for successful genome editing. Although the GSH-degradable NCs are expected to remain stable in the extracellular spaces and circulation (GSH concentration: 0.001–0.02 mM)12, 13, their stability was systematically tested because the degradability of disulfide bonds in different polymers can differ17. To determine at which GSH concentration NCs remain stable and functional, cell culture media containing different concentrations of GSH were used during NC treatment. The gene editing efficiency of NCs did not change at a GSH concentration of 0.1 mM or lower, indicating that NCs were stable and functional at a GSH concentration at least up to 0.1 mM (Fig. 2a). At a GSH concentration of 1 mM or higher, the gene editing efficiency decreased, suggesting that NCs were disrupted before cell internalization. This also implies that NCs are GSH-responsive and RNP cargo can be efficiently released from NCs in the GSH-rich cytosol (2–10 mM).

Figure 2 |. Stability, uptake, and toxicity characteristics of NCs within human cells in vitro.

a, Stability and responsiveness study of NCs with different concentrations of GSH. Gene editing efficiencies of NCs in GSH-containing media were tested in mCherry-HEK cells with an sgRNA targeting mCherry. The loss of mCherry fluorescence was measured six days after transfection via flow cytometry to assay editing efficiency. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). b, Intracellular distribution of NCs in HEK cells using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) 6 hours after transfection. The sgRNA was covalently labeled with the ATTO-550 fluorophore (red signal) to track its intracellular location. Cells were stained with LysoTracker Green DND-26 and DAPI for endosomes/lysosomes and nuclei, respectively. Scale bar: 10 μm. Experiments were repeated three times. c, Gene editing in mCherry-HEK293 cells with unencapsulated RNP, optimized Lipofectamine 2000 system (i.e., Lipo), or NC. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). d, Cell viability measured by an MTT assay after treatment with Lipo and NCs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 6). e, Editing efficiency of NCs after lyophilization. Treatments included freshly prepared NCs [i.e., NC (Fresh)], NCs lyophilized after a fast-freezing process [i.e., NC (Fast-freezing lyophilization)], or NCs lyophilized after a slow freezing process (i.e., NC (Slow-freezing lyophilization)). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). Statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We examined the subcellular localization of the RNP cargo in HEK cells in vitro. As shown in Fig. 2b, after 6 h incubation, most of RNP (red fluorescence) and endosomes (green fluorescence) were not overlapping, indicating that RNPs were capable of escaping from the endosomes.

We then compared the in vitro gene editing functionality of NCs with Lipofectamine-based delivery vehicles, (e.g., Lipofectamine 2000 and Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX), the state-of-the-art, commercially available transfection agents for RNP delivery. Lipofectamine delivery systems were also systemically optimized (Fig. S1), where Lipofectamine 2000 with 0.75 μl per well in the 96-well plate exhibited the highest gene editing efficiency, which was used for the following study (denoted as Lipo). Unencapsulated RNP treatment was included since RNP itself shows some cell penetrating capability, likely conferred by the positively-charged NLSs18. Compared to the untreated control, RNP alone induced only 1.6 ± 0.5% editing above the background levels, which was significantly lower than that delivered by either Lipo (i.e., 60.1 ± 1.7 %), or NC (i.e., 79.1 ± 0.6 %), where NCs exhibited the highest editing efficiency (Fig. 2c). Moreover, NCs did not cause apparent cytotoxicity in HEK cells (<6% cell death), while consistent with other studies, Lipo exhibited significant cytotoxicity when it was used to deliver the same amount of RNP (i.e., ~25% cell death, Fig. 2d). Importantly, NCs could be freeze-dried and reconstituted at high concentrations (~5 μg/μL) while retaining potency (>90%), unlike many liposomal delivery agents that lose stability upon freeze-drying19 (Fig. 2e and Fig. S1).

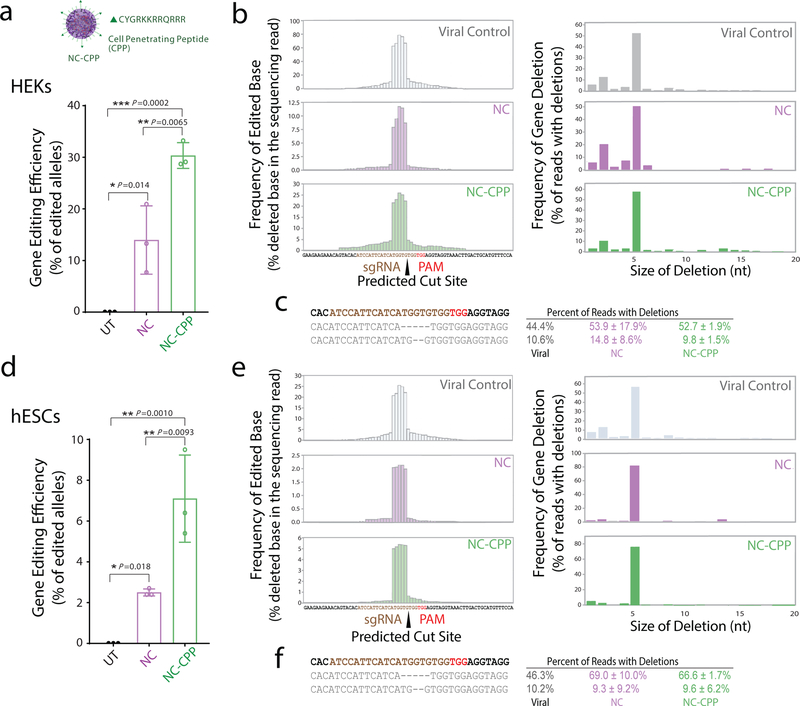

To demonstrate the versatility of NC surface modification, we first functionalized NCs with CPPs (i.e., NC-CPP, Fig. 3a), which are known to enhance the cellular uptake efficiency of nanoparticles. CPPs (or the targeting ligand, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), used in the following in vivo experiments) were incorporated onto the distal ends of a higher molecular weight PEG (i.e., 2 kDa). The use of longer PEGs could potentially reduce the steric hindrance from the surrounding mPEG segments (i.e., 480 Da), allowing for better targeting or penetrating capabilities20. Detailed polymer and NC characterizations are shown in the Supplementary Information (Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S1). As expected, CPP conjugation on NCs significantly enhanced (~1.5 fold) their level of cellular uptake (Fig. S4). Moreover, when loaded with RNP targeting the endogenous APP gene, NC-CPP enhanced editing efficiency in HEK cells as well as human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), a notoriously hard-to-transfect cell type (Fig. 3). Deep sequencing of the on-target region around APP revealed high-efficiency editing at this endogenous locus. In HEKs, NC-CPP increased editing efficiency two-fold (Fig. 3a), while in hESCs, NC-CPP increased editing efficiency approximately three-fold (Fig. 3d). The deletion spectra (Fig. 3b–e) for both cell types contained a 5 base deletion as a frequent editing outcome in all of the samples, consistent with a previous report using this sgRNA sequence21. Together, these in vitro results demonstrate that decoration of the NC can enhance genome editing at an endogenous, therapeutically relevant locus without changing the types of edits produced by Cas9.

Figure 3 |. Decoration of NCs with targeting ligands increases on-target genome editing efficiency in vitro within human cell lines.

a, Deep sequencing of human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells transfected with NCs containing a Cas9 RNP with an sgRNA targeting the endogenous APP locus. NCs were decorated with cell-penetrating peptides (NC-CPP). Targeted PCR amplification around the on-target site reveals high on-target editing by NCs. Percent of sequencing reads with a genomic edit are plotted compared to an untransfected control sample (UT). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). b, Deletion spectra for reads with deleted bases are shown for every base proximal to the sgRNA target. Viral control refers to previously characterized spectrum for this sgRNA in HEK cells from Sun et al.21 Figures on the right show the size of deletions in the edited sequencing reads. c, Frequencies of major reads with deletions in HEK cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). d, Deep sequencing of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) transfected with NCs containing a Cas9 RNP with an sgRNA targeting the endogenous APP locus. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). e, Deletion spectra and size of deletions in hESCs as noted in b. f, Frequencies of major reads with deletions in hESC cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n= 3). Statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

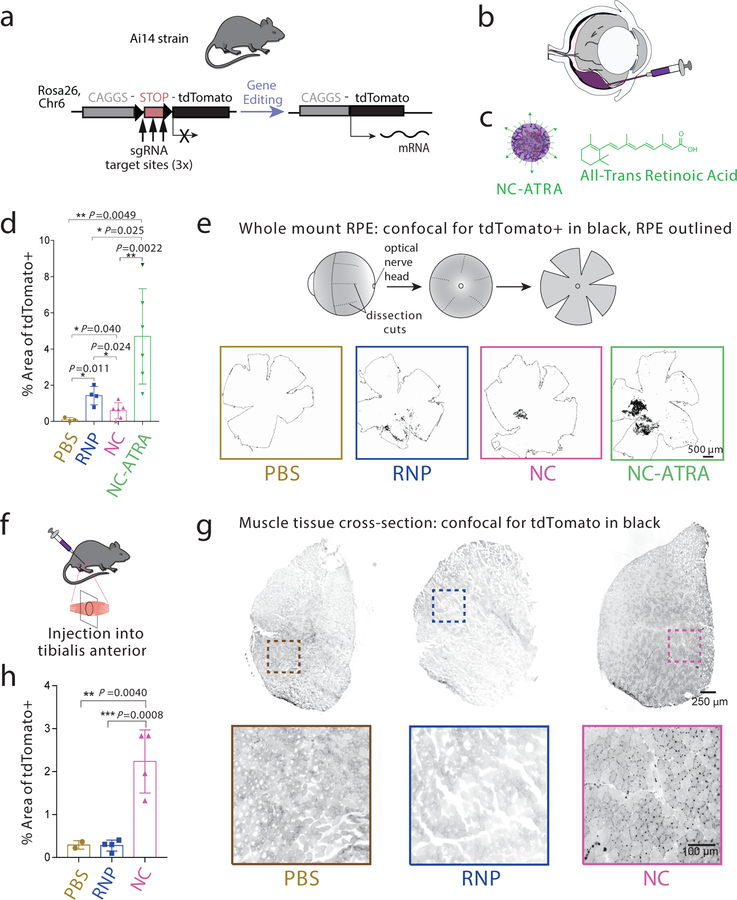

Gene editing using NCs was finally evaluated in vivo in the eyes and muscles of transgenic Ai14 mice (Fig. 4). All cells within Ai14 mice contain a stop cassette, comprised of three sv40 polyA transcription terminators, preventing expression of a constitutive tdTomato fluorescent reporter. tdTomato expression can be induced via excision of the sv40 polyA genetic elements (Fig. 4a). Successful gene editing can therefore be easily evaluated through fluorescence18. First, we evaluated gene editing within the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) because over two million people worldwide are affected by monogenic diseases of the eye22, and several somatic gene editing strategies are being developed for subretinal delivery23. We tested whether surface modification of the NC could affect its gene editing performance within RPE. NCs were decorated with ATRA (i.e., NC-ATRA). ATRA binds to the inter-photoreceptor retinoid-binding protein, a major protein in the inter-photoreceptor matrix that selectively transports 11-cis-retinal to photoreceptor outer segments and all-trans-retinol to the RPE24. Mice were subretinally injected with a PBS vehicle, RNP alone, NC, or NC-ATRA (Fig. 4b, c). Successful subretinal injection was indicated by a bleb formation immediately next to the RPE (Fig. S5). Twelve days post injection, enucleated eyes were whole-mounted to evaluate gene editing globally over the entire RPE tissue (Fig. 4d, e). In contrast to the in vitro results in HEKs as discussed previously and the in vivo results in muscle cells to be discussed later, where RNP alone did not induce any genome editing, unencapsulated RNP was able to induce genome editing in RPEs. This may be attributed to the inherent function of this tissue as a transport epithelium: RPE cells are involved in the movement of nutrients and waste products through bidirectional passive and active pathways25, 26. The subretinal space is a tight space that ensures fluid absorption from retina to choroid directionthrough the RPE layer for retina reattachment following subretinal injections, and further RPE cells are among the most actively phagocytic cells found in the body27, 28. NCs also exhibited considerable gene editing, and NC-ATRA induced significantly higher editing efficiency than other groups (Figs 4d, e). Second, we tested the activity of NCs in muscle tissue via intramuscular administration in the same mouse model (Fig. 4f). As shown in Fig. 4g and 4h, unencapsulated RNP failed to induce any genome editing in muscles, while NCs induced robust gene editing. Interestingly, strong tdTomato signals were identified in the cells within the basal lamina between muscle fibers. Because muscle satellite cells—quiescent mononucleated myogenic cells in adult muscle—are present in this region, we performed immunohistochemistry to co-stain with Pax7 (a muscle satellite cell marker) and tdTomato (RFP) in the muscle sections. Overlapping signals of Pax7 and RFP in NC-injected muscle (Fig. S6) indicated that Pax7-positive satellite cells expressed tdTomato protein. Collectively, these results demonstrated that NC formulations could produce gene edits in vivo, the extent of which can be further modulated by surface functionalization.

Figure 4 |. NCs can induce efficient genome editing in vivo within Ai14 reporter mice.

a, Schematic of the tdTomato locus within the Ai14 mouse strain. A STOP cassette consisting of three SV40 polyA sequences prevents transcription of the downstream red fluorescent protein variant, tdTomato (left). When cells are edited by CRISPR/Cas9 to excise the STOP cassette via cut sites present in each of the repeats, they will express tdTomato (right). b, Schematic of the subretinal injection of genome editors to target the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) cells. c, Illustration of NC-ATRA. d, Genome editing efficiency as quantified by percent of area of whole RPE with genome editing reporter (tdTomato+). PBS (n=3), RNP (n=4), NC (n=6), or NC-ATRA (n=6). Data are presented as mean ± SD. e, Schematic of whole mount RPE preparation and representative images of tdTomato+ signal (black) 12 d after subretinal injection. The whole RPE layer is outlined. Experiments were repeated three times. f, Schematic of intramuscular injection of genome editors. g, Representative images of the muscle tissues 12 days after intramuscular injection of either PBS, RNP, or NC. Experiments were repeated three times. h, Gene editing efficiency as quantified by percent of area of whole muscle tissue with genome editing reporter (tdTomato+). n=4 for all conditions except PBS (n=2). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Our approach accommodates the charge heterogeneity of Cas9 RNP (~9 nm in diameter) to form covalently-linked stable, yet biodegradable, NCs. NCs were formed by coating RNPs using a mixture of monomers with distinct functions as described above. The RNP serves as the core/scaffold for the formation of the NC. The acrylate monomers are attracted to the RNP surface either electrostatically or via van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding for subsequent polymerization, resulting in nearly monodispersed NCs with an average size of 16 nm in the dried state. This chemically defined strategy, therefore, has a fixed stoichiometry between the NC and RNP that constitutes a predictable formulation that is considerably smaller than other nonviral Cas9 delivery strategies.

The monomeric precursors of NCs allow for easy fine-tuning of the ratios and amounts of monomers to control endosomal escape and cytosol release of RNP from NCs, as well as the conjugation of functional moieties. This customizability is a key advantage over lipid-based29 and protein-engineering30-based methods which may be less flexible. NCs also retain their biological functions after freeze-drying, thereby allowing for long-term storage and transport. Furthermore, employing protein engineering to facilitate delivery may alter Cas9-sgRNA interactions and interfere with proper RNP function as described previously30. Our NC delivery system demonstrated robust gene editing outcomes and lower cytotoxicity. Finally, the NC delivery system also induced efficient gene editing in vivo, highlighting its versatility via surface modification. Due to the small size, modularity, and low cytotoxicity of NCs, we anticipate that NCs could be further tailored to efficiently deliver gene editing machinery to a multitude of cell lines in vitro and many tissues in vivo for somatic gene editing applications.

Methods

Materials:

Acrylic acid (AA), N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA), acrylate PEG (APEG; 480 Da), bisacrylamide (BAA), 1-vinylimidazole (VI), and ammonium persulfate (APS) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Fitchburg, WI, USA). Acrylate PEG-NH2 (APEG-NH2; 2 kDa) was acquired from JenKem Technology (Allen, TX, USA). 4-Imidazolecarboxylic acid, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), N-(3-aminopropyl)methacrylamide hydrochloride (APMA), and N,N’-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BACA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Acrylate PEG-Mal (APEG-Mal; 2 kDa) was purchased from Creative PEGWorks (Chapel Hill, NC). Cell penetrating peptide (CPP), TAT-Cys (CYGRKKRRQRRR), was synthesized by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ).

Cell Culture:

The human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line was maintained on gelatin-A coated plates at passage 10–50 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-Glutamine, and 50 U/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin. WA09 hESCs (WiCell, Madison, WI) were maintained in mTESR medium on Matrigel (WiCell) coated tissue culture polystyrene plates (BD Falcon). hESCs were passaged every 3–4 days at a 1:6 ratio using Versene solution (Life Technologies). H2B-mCherry transgenic lines were generated as previously reported31 through CRISPR-mediated insertion of an AAV-CAGGS-EGFP plasmid (Addgene #22212), modified to express Histone 2B-mCherry, at the AAVS1 safe harbor locus using gRNA AAVS1-T2 (Addgene #41818). All cells were maintained at 37 ºC and 5% CO2. Cell lines were kept mCherry positive through puromycin selection or fluorescence assisted cell sorting (FACS) on a BD FACS Aria.

sgRNAs In Vitro Transcription:

A DNA double stranded template of a truncated T7 promoter and desired sgRNA sequence was formed through overlap PCR using Q5 high fidelity polymerase (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s protocols and was placed in the thermocycler for 35 cycles of 98 ºC for 5 s, 52 ºC for 10 s, and 72 ºC for 15 s, with a final extension period of 72 ºC for 10 min. PCR products were then incubated overnight at 37ºC in a HiScribe T7 in vitro transcription reaction (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting RNA was purified using a MEGAclear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (Thermo Fisher). sgRNA concentration was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher). The sgRNA sequences used were (with PAM site): mCherry:GGAGCCGTACATGAACTGAGGGG; APP: ATCCATTCATCATGGTGGTGG; tdTomato: AAGTAAAACCTCTACAAATGTGG.

Preparation of nanocapsules (NCs):

Sodium bicarbonate buffer (10 mM, pH = 9.0) was freshly prepared and degassed using the freeze–pump–thaw method for 3 cycles. sNLS-Cas9-sNLS protein (Aldevron, Madison, WI) was combined with sgRNA at a 1:1 molar ratio and allowed to complex for 5 minutes with gentle mixing. AA, APMA, VI, and APEG were accurately weighed and dissolved in degassed sodium bicarbonate buffer (2 mg/ml). VI, APS, and TMEDA were accurately weighed and dissolved in degassed sodium bicarbonate buffer (1 mg/ml). Cas9 RNP complex was diluted to 0.12 mg/mL in sodium bicarbonate buffer in a nitrogen atmosphere. Monomer solutions were added into the above solution under stirring in the order of AA, APMA, and VI at 5-minute intervals. In each 5-minute interval, the solution was degassed by vacuum pump for 3 minutes and refluxed with nitrogen. After another 5 min, the crosslinker, BACA, was added, followed by the addition of ammonium persulfate. The mixture was degassed for 5 min, and the polymerization reaction was immediately initiated by the addition of TMEDA. After 65 min of polymerization under a nitrogen atmosphere, the APEG was added. The reaction was resumed for another 30 min. Finally, unreacted monomers and initiators were removed by dialysis in 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 7.4). The molar ratio of AA/APMA/VI/BACA/APEG (i/ii/iii/iv/v) used for the optimal formulation was 927/927/244/231/33. The molar ratio of RNP:APS: TMEDA was kept at 1:1:1.

For the preparation of NCs conjugated with CPP (i.e., NC-CPP), we first prepared acrylate PEG-CPP (APEG-CPP) by reacting APEG-Mal and TAT-Cys through an SH-Mal reaction in an aqueous solution at a pH of 7.4. Then, the NC-CPP was prepared following a similar protocol as described above with the molar ratio of AA/APMA/VI/BACA/APEG-CPP at 927/927/244/231/33.

For the preparation of NCs conjugated with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) (i.e., NC-ATRA), acrylate PEG-ATRA (APEG-ATRA) was first prepared by reacting APEG-NHS and ATRA through amidization. Briefly, APEG-NHS (1.0 mg), ATRA (0.18 mg), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (0.11 mg), and N-hydroxysuccinimide (0.10 mg) were dissolved in PBS (3 mL; pH 7.4). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Subsequently, it was dialyzed against DI water for 48 h to remove impurities. The polymer, APEG-ATRA, was obtained by lyophilization. Then, the NC-ATRA was prepared following the similar protocol as described above with the molar ratio of AA/APMA/VI/BACA/APEG/APEG-ATRA at 927/927/244/231/33.

The dried NCs were prepared using either a fast or slow freezing process before lyophilization. For the fast freezing process, NC solutions were frozen rapidly using liquid nitrogen and were then dried using a lyophilizer. For the slow freezing process, NC solutions were frozen using a Mr. Frosty™ Freezing Container at a cooling rate of −1°C/minute (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fitchburg, WI) and were then dried using a lyophilizer.

Characterization:

The sizes and morphologies of Cas9 RNP NCs were studied by dynamic light scattering (DLS, ZetaSizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, USA) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F30 TWIN 300 KV, E.A. Fischione Instruments, Inc. USA). Zeta potentials were measured by ZetaSizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, USA). The RNP loading level and efficiency of NC were determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Assaying RNP Delivery:

Cells were seeded in 96 well plates in 100 μl of media one day prior to transfection. On the day of transfection, unencapsulated RNP, NC-RNP or Lipofectamine-based RNP complexes (including Lipofectamine 2000/RNP and Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX/RNP) were added to the cells for transfection of RNPs according to manufacturer instructions (e.g., 0.2–0.75 µl/well of Lipofectamine 2000 and 0.3 µl/well of Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX). At day 6, cells were collected for flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II) and assayed for mCherry expression. Flow analysis was performed using FlowJo software. For HEK 293s, 7.8 nM RNP was used per well. To examine the activity of unencapsulated RNP, a high dose (1 μM) of RNP was also tested.

For experiments involving APP targeting, cells were cultured in 24 well plates at 50,000 cells/well. 6.25 nM RNP were used to transfect HEK 293 cells, while 25 nM RNP were used to transfect human embryonic stem cells (hESCs).

To study the stability of the RNP NCs in the presence of GSH, the gene editing efficiency of NCs under different GSH concentrations was tested. The experiments were carried out under similar conditions as described above using GSH-containing media, instead. The GSH concentration investigated ranged from 0 to 20 mM.

Genomic analysis:

DNA was isolated from cells using DNA QuickExtract (Epicentre, Madison, WI) following treatment by 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and centrifugation. QuickExtract solution was incubated at 65 ºC for 15 min, 68 ºC for 15 min, and then 98 ºC for 10 min. Genomic PCR was performed following manufacturer’s instructions using Q5 High fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and ~500 ng of genomic DNA. Products were then purified using AMPure XP magnetic bead purification kit (Beckman Coulter) and quantified using a Nanodrop2000 or Qubit (Thermo Fisher). For deep sequencing of the APP locus, genomic DNA was amplified using the following primers: TGTCATAGCGACAGTGATCGT and AGCTAAGCCTAATTCTCTCATAGTC. Samples were pooled and run on an Illumina Miniseq with read length of 150bp. Deep sequencing data was analyzed using the Cas-Analyzer software32.

Intracellular Trafficking:

HEK 293 cells were seeded at a density of ~40,000 cells/well one day prior to transfection in 1 µm 2 well culture chambers (Ibidi). NCs were formed with Atto-550 fluorescently tagged tracrRNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) combined with crRNA and added to cells at 1 μg/well for transfection. After 6 h incubation, cells were stained with LysoTracker Green DND-26 and DAPI for endosomes/lysosomes and nuclei, respectively. Cells were imaged using an Eclipse TI epifluorescent microscope (Nikon) and as AR1 confocal microscope (Nikon). Image analysis was performed using CellProfiler. For flow cytometric analysis, HEK 293 cells were seeded in 96 well plates and dissociated after 4 hours, followed by flow cytometry on an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences).

MTT Assay:

HEK 293 cells were seeded in 96 well plates (17,500 cells/well) in 100 μl of media one day prior to transfection. On the day of transfection, NC, RNP/Lipofectamine 2000 (0.2–0.75 µl/well), or RNP/Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX (0.3 µl/well) were added to the cells. After two day of incubation, a standard MTT assay was performed by aspirating the treatment media, adding 25 μL of the medium containing 0.5mg/mL MTT agent, and incubating at 37 °C for 4 h. Thereafter, the medium was aspirated and 75 μL of DMSO was added to each well. The plates were then measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer (Quant, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT), and the average absorbance and percent of cell viability relative to the control (pure medium) were calculated.

Subretinal Injection:

For mice studies, Ai14 mice (obtained from Jackson Labs) were used to assay gene editing efficiency in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). All RNPs were formed with sgRNA targeted for excision of SV40 polyA blocks22 (target sequence: AAGTAAAACCTCTACAAATG). As previously described, mice were maintained under tightly controlled temperature (23 ± 5 °C), humidity (40–50%) and light/dark (12/12 h) cycle conditions in 200 lux light environment. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg), xylazine (16 mg/kg) and acepromazine (5 mg/kg) cocktail. Prior to the sub-retinal injection, the cornea was anesthetized with a drop of 0.5% proparacaine HCl and the pupil was dilated with 1.0% tropicamide ophthalmic solution (Bausch & Lomb Incorporated, Rochester, NY). Thermal stability was maintained by placing mice on a temperature-regulated heating pad during the injection and for recovery purposes. All surgical manipulations were carried out under a surgical microscope (AmScope, Irvine, CA). 2 μL of solution containing either RNP alone, NC, or NC-ATRA, at the concentration of 8 μg RNP was injected into the sub-retinal space using the UMP3 ultramicro pump fitted with a NanoFil syringe, and the RPE-KIT (all from World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) equipped with 34 gauge beveled needle. Successful administration was confirmed by bleb formation (Fig. S5). The tip of the needle remained in the bleb for 10 s after bleb formation, when it was gently withdrawn. A solution (2 μL) of PBS vehicle was also injected into the sub-retinal space of the contralateral eye to serve as a control.

To assess tdTomato expression generated by successful gene editing, the mice were sacrificed, and eyes were collected 12 days after injection. Enucleated eyes from the sacrificed mice were rinsed twice with PBS, a puncture was made at ora serrata with an 18 gauge needle and the eyes were opened along the corneal incisions. The lens was then carefully removed. The eye cup was flattened making incisions radially to the center giving the final “starfish” appearance. The retina was then separated gently from the RPE layer. The separated RPE and retina were flat mounted on the cover-glass slide and were imaged with NIS-Elements using a Nikon C2 confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Mellville, NY). 561 nm Diode Lasers for red excitation was used to evaluate the tdTomato expression in the RPE layer and images were captured by Low Noise PMT C2 detectors in a Plan Apo VC 20X/0.75, 1 mm WD lens. ImageJ (NIH) was used for image analysis to measure the tdTomato positive areas in relevant ROIs (masked to RPE areas from brightfield images).

Intramuscular injection:

All treatments (PBS, RNP, and NC) were administered to adult mice via the tibialis anterior (TA, 8–10 μL per muscle) using a 33-gauge needle with a Hamilton syringe. Twelve days after the injection, TA muscles were harvested and flash-frozen in super-cooled isopentane. TA muscles were then sectioned at 20 µm using a cryostat and placed on glass slides. After mounting a slide glass, muscle sections were observed with by using a Keyence BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope (Osaka, Japan) to visualize tdTomato fluorescence. For quantification of fluorescence signals, three sections per muscle were selected from the similar locations in the TA muscle. The relative intensity of tdTomato-positive signal was densitometrically evaluated using NIH ImageJ software.

For immunohistochemistry, the muscle sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline, and then incubated with primary antibodies for overnight. The following primary antibodies were used to probe for muscle satellite cells and tdTomato, respectively: anti-Pax7 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and anti-RFP (rabbit polyclonal, Rockland Immunochemical Inc., Limerick PA). The primary antibodies were then detected by fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies. All images were optimized by using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope with a digital camera (DS-QiIMC, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the James Thomson lab for the use of their BD FACSCanto II, and the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center for providing facilities and services. We thank Aldevron for supplying reagents and technical support. We are grateful to Prof. Qiang Chang who provided us with the Ai14 tdTomato transgenic mice used for initial evaluation. We acknowledge the generous financial support from the National Institute for Health (UG3 TR002659-01, R01EY024995, 1R35GM119644, R01NS091540, R01HL143469, and R01 HL129785), the National Science Foundation (CBET-1350178 and CBET-1645123), the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, and the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery. The authors would also like to acknowledge financial support from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

G.C., A.A.A., Y.W., R.X., K.S., and S.G. have filed a patent application on this work.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permission information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to KS and SG.

Data Availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Yin H, Kauffman KJ & Anderson DG Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 387–399 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J et al. Efficient delivery of nuclease proteins for genome editing in human stem cells and primary cells. Nat. Protoc 10, 1842–1859 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L, He Z, Wei X, Gao G & Wei Y Challenges in CRISPR/CAS9 delivery: potential roles of nonviral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther 26, 452–462 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mout R, Ray M, Lee YW, Scaletti F & Rotello VM In vivo delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for therapeutic gene editing: progress and challenges. Bioconjugate Chem 28, 880–884 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HX et al. CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for disease modeling and therapy: challenges and opportunities for nonviral delivery. Chem. Rev 117, 9874–9906 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Hu S & Chen X Non-viral delivery systems for CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing: Challenges and opportunities. Biomaterials 171, 207–218 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rui Y, Wilson DR & Green JJ Non-viral delivery to enable genome editing. Trends Biotechnol 37, 281–293 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu Z et al. Protein nanocapsule weaved with enzymatically degradable polymeric network. Nano Lett 9, 4533–4538 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M et al. Clickable protein nanocapsules for targeted delivery of recombinant p53 protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 15319–15325 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan M, et al. A novel intracellular protein delivery platform based on single-protein nanocapsules. Nat. Nanotechnol 5, 48–53 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putnam D, Gentry CA, Pack DW & Langer R Polymer-based gene delivery with low cytotoxicity by a unique balance of side-chain termini. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1200–1205 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng F, Cheng R, Deng C & Zhong Z Intracellular drug release nanosystems. Mater. Today 15, 436–442 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F et al. PKM2 methylation by CARM1 activates aerobic glycolysis to promote tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 19, 1358–1370 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mout R et al. Direct cytosolic delivery of CRISPR/Cas9-ribonucleoprotein for efficient gene editing. ACS Nano 11, 2452–2458 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson-Stevermer J et al. High-content analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 6, 109–120 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson-Stevermer J et al. Assembly of CRISPR ribonucleoproteins with biotinylated oligonucleotides via an RNA aptamer for precise gene editing. Nat. Commun 8, 1711 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elzes MR, Akeroyd N, Engbersen JF & Paulusse JM Disulfide-functional poly (amido amine)s with tunable degradability for gene delivery. J. Control. Release 244, 357–365 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staahl BT et al. Efficient genome editing in the mouse brain by local delivery of engineered Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Biotechnol 35, 431–434 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payton NM, Wempe MF & Xu Y Anchordoquy TJ. Long-term storage of lyophilized liposomal formulations. J. Pharm. Sci 103, 3869–3878 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen G et al. Multi-functional self-fluorescent unimolecular micelles for tumor-targeted drug delivery and bioimaging. Biomaterials 47, 41–50 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of APP C-terminus attenuates β-cleavage and promotes α-cleavage. Nat. Commun 10, 53 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger W, Kloeckener-Gruissem B & Neidhardt J The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res 29, 335–375 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeder ML et al. Development of a gene-editing approach to restore vision loss in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10. Nat. Med 25, 229–233 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun D et al. Targeted multifunctional lipid ECO plasmid DNA nanoparticles as efficient non-viral gene therapy for leber’s congenital amaurosis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 7, 42–52 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmor MF Control of subretinal fluid: experimental and clinical studies. Eye 4, 340–344 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss O The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol. Rev 85, 845–881 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao Y & Finnemann SC Analysis of photoreceptor outer segment phagocytosis by RPE cells in culture. Retinal Degeneration Springer, pp 285–295 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzoni F, Mao Y & Finnemann SC Advanced Analysis of Photoreceptor Outer Segment Phagocytosis by RPE Cells in Culture. Retinal Degeneration Springer, 2019, pp 95–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steyer B et al. High content analysis platform for optimization of lipid mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery strategies in human cells. Acta Biomater 34, 143–158 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuris JA et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 33, 73–80 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harkness T et al. High-content imaging with micropatterned multiwell plates reveals influence of cell geometry and cytoskeleton on chromatin dynamics. Biotechnol. J 10, 1555–1567 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J, Lim K, Kim JS & Bae S Cas-analyzer: an online tool for assessing genome editing results using NGS data. Bioinformatics 33, 286–288 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.