Summary

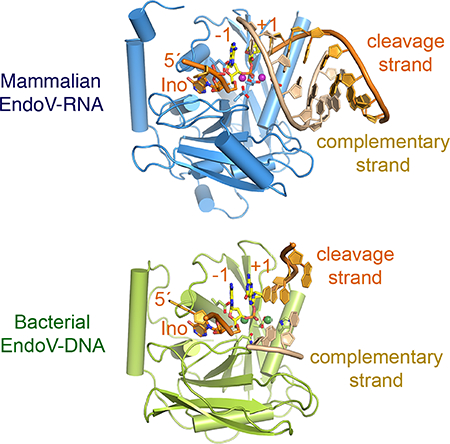

Endonuclease V (EndoV) cleaves the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to a deaminated adenosine (inosine). Although highly conserved, EndoV homologs change substrate preference from DNA in bacteria to RNA in eukaryotes. We have characterized EndoV from six different species and determined crystal structures of human EndoV and three EndoV homologs from bacteria to mouse in complex with inosine-containing DNA/RNA hybrid or dsRNA. Inosine recognition is conserved, but changes in several connecting loops in eukaryotic EndoV confer recognition of 3 ribonucleotides upstream and 7–8 bp of dsRNA downstream of the cleavage site, while bacterial EndoV binds only 2–3 nucleotides flanking the scissile phosphate. In addition to the two canonical metal ions in the active site, a third Mn2+ that coordinates the nucleophilic water appears necessary for product formation. Comparison of EndoV with its homologs RNase H1 and Argonaute reveals the principles by which these enzymes recognize RNA versus DNA.

Keywords: RNase, DNase, ribonucleotide recognition, adenosine deamination, metal ion, catalysis, evolution

eTOC

Wu et al. show that bacterial Endonuclease V (EndoV) cleaves DNA in the presence of an inosine (deaminated adenosine), but eukaryotic EndoV due to insertions in two non-conserved loops cleaves inosine-containing RNA only. A similar DNA-to-RNA evolution also occurs in Argonaute.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Studies of Endonuclease V (EndoV) have led to a succession of surprising discoveries over the last several decades. When initially isolated in 1977, EndoV was shown to have a low hydrolytic activity on a variety of damaged DNAs in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+ at pH 9.5 (Demple and Linn, 1982; Gates and Linn, 1977). It was not until 1997 that EndoV was found to recognize inosine, a product of adenosine deamination caused by hydrolytic or nitrosative reactions and dIMP incorporation during DNA synthesis (Cao, 2013; Weiss, 2001), and specifically cleave the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to inosine in DNA (Guo et al., 1997; Yao et al., 1994). In parallel to glycosylase AlkA in the base-excision repair pathway in E. coli, EndoV provides an alternative means to eliminate inosine. Without repair, persistent inosine, which behaves like guanosine, would lead to dCMP incorporation during DNA synthesis resulting in A to G mutations (Schouten and Weiss, 1999; Weiss, 2008). Crystal structures of Thermotoga maritima EndoV (TmEndoV) in complex with inosine-containing DNA were reported in 2009 and reveal the specific recognition of hypoxanthine (inosine base) and an RNase H1-like active site (Dalhus et al., 2009). The next surprise came in 2013 when human EndoV (HsEndoV), which shares >30% sequence identity with bacterial homologs, was found to cleave single-stranded RNA containing an inosine, but not DNA (Morita et al., 2013; Vik et al., 2013). Since ADAR (adenosine deaminase acting on RNA) and A-to-I RNA editing are prevalent in metazoans (Eisenberg and Levanon, 2018), inosine-specific RNA decay must be necessary. To date the molecular mechanism for the recognition of RNA instead of DNA and the function of EndoV in mammals remain unresolved (Kim et al., 2016; Nawaz et al., 2016a).

Alternative recognition of DNA and RNA has been reported for Argonaute (Ago) proteins in the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway (Swarts et al., 2014). Bacterial and archaeal Ago proteins are able to use a DNA guide to target DNA or RNA cleavage (Sheng et al., 2014), but eukaryotic Ago proteins are exclusively RNA-guided RNA endonucleases (Swarts et al., 2014). It is perhaps not a coincidence that the catalytic domain of Ago (known as a PIWI domain) is homologous to RNase H1, which hydrolyzes the RNA strand in an RNA/DNA hybrid. The active site of EndoV, AgoPIWI and RNase H1 share three highly conserved carboxylates in the sequence Asp-Glu-Asp (DED), which are followed by a less well conserved fourth residue, Asp in most cases (DEDD), but occasionally Asn or His (Cerritelli and Crouch, 2009; Dalhus et al., 2015; Kuhn and Joshua-Tor, 2013; Tadokoro and Kanaya, 2009) (Fig. 1A). In addition, the RNase H1-like fold is common among DNases (Majorek et al., 2014; Yang and Steitz, 1995), including 3′−5′ Exonuclease, HIV-1 integrase, RAG1/2 recombinase, DNA repair endonuclease UvrC, and Holliday-Junction resolvase RuvC. However, Glu as the second catalytic carboxylate exists in only EndoV, Ago and RNase H1. This Glu is found to coordinate both the B-site Mg2+ and the 2′-OH 5′ to the scissile phosphate in RNase H1 and Ago (Nowotny et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009) and likely influences the preference for RNA cleavage instead of DNA. In fact, human EndoV is shown to cleave inosine-containing DNA if there is just one ribonucleotide 5′ to the scissile phosphate (Morita et al., 2013; Vik et al., 2013).

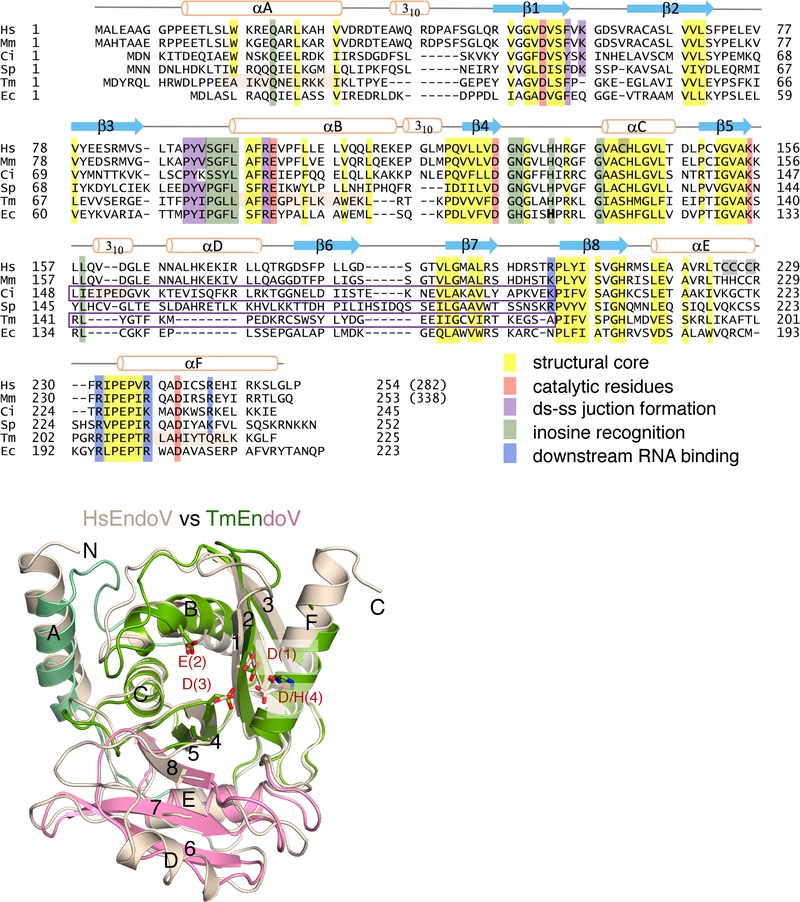

Figure 1.

Comparison of six EndoV from bacteria to humans. (A) Sequence alignment of EndoV from E. coli (Ec, WP_000362388.1), T. maritima (Tm, NP_229661.1), S. pombe (Sp, CAA93810.1), Ciona intestinalis (Ci, XP_026692171.1), mouse (Mm, NP_001158108.1) and human (Hs, NP_775898). Secondary structures and functional roles of conserved residues are marked and highlighted. Helix length that differs from the conserved secondary structure is marked by orange highlight. The four Cys mutated to Ala or Ser in HsEndoV are highlighted in grey. The sequences swapped between TmEndoV and CiEndoV are outlined in purple. (B) Superposition of the apo HsEndoV structure reported here (wheat color) and the previously published TmEndoV structure (PDB: 2W35, colored green and pink). The RNH core and four catalytic carboxylates (D(1), E(2), D(3) and D/H(4)) are highly similar, but HsEndoV has an additional helix αD in the CTI domain and slightly different N- and C-termini.

In the crystal structure of the TmEndoV-DNA product complex only one Mg2+ is found in the active site (Dalhus et al., 2009) rather than two Mg2+ ions as observed with RNase H1 and Ago (Nowotny et al., 2005; Nowotny et al., 2007; Sheng et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2009). This observation raises the question as to whether the catalytic mechanism is conserved among these related enzymes. Recently, by trapping successive steps in DNA synthesis and RNA hydrolysis in crystallo using time-resolved X-ray diffraction, we found that in addition to the canonical two divalent cations, Mg2+ or Mn2+, which interact with and orient the substrate, a transient third divalent cation is required for catalysis (Gao and Yang, 2016; Nakamura et al., 2012; Samara and Yang, 2018). Furthermore, in the RNase H1 reaction, K+ ions also participate in catalysis (Samara and Yang, 2018). Whether additional cations are required for EndoV catalysis is unknown.

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism of EndoV and how it recognizes RNA vs. DNA, we expressed and purified EndoV from E. coli (EcEndoV), T. maritima (TmEndoV), fission yeast S. pombe (SpEndoV), invertebrate Ciona intestinalis (CiEndoV), mouse (MmEndoV) and human (HsEndoV), assayed their binding and cleavage activities on inosine-containing DNA and RNA substrates, and determined crystal structures of HsEndoV alone and Tm, Ci and Mm EndoV in complex with nucleic acid substrates. Finally, we used in crystallo catalysis to capture reaction intermediates of RNA cleavage by MmEndoV. Combining structural and mutagenic approaches, we have delineated the catalytic mechanism of EndoV and how its substrate recognition has evolved.

Results

Increased RNA preference from bacterial to eukaryotic EndoV

To uncover how human EndoV differs from bacterial homologs and prefers RNA substrate, we initially determined the crystal structure of HsEndoV. To improve the solubility of HsEndoV, which has a total of eight Cys residues, we mutated non-conserved Cys residues to Ala or Ser in various combinations and confirmed their endonuclease activity before obtaining a 1.50 Å resolution crystal structure with four Cys residues mutated (C140S/C225S/C226A/C228S) (Fig. 1A–B, Table S1). Except for an extra α-helix (αD) distal to the active site, the HsEndoV structure is highly similar to TmEndoV (Dalhus et al., 2009) (Fig. 1B) and thus uninformative about the preference for RNA versus DNA. This conclusion is corroborated by independently determined human, mouse and E. coli EndoV structures (Nawaz et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015) (Fig. S1A–B).

We then systematically analyzed EndoV from bacteria (Tm), fungi (Sp), invertebrate (Ci) and vertebrates (Mm), and synthesized codon-optimized EndoV genes for expression in E. coli. Together with E. coli (Ec) and human EndoV (Hs), these six proteins were expressed and purified to homogeneity for biochemical and structural characterization (Fig. S1C).

Previous analyses have shown that bacterial and archaeal EndoV cleave single- and double-stranded nucleic acids equally well, but HsEndoV cleaves ssRNA most efficiently (Morita et al., 2013; Vik et al., 2013). In the structures of TmEndoV (Dalhus et al., 2009) obtained in the presence of a DNA duplex, only one DNA strand was retained in the complex. This strand formed a heterologous (mismatched) duplex with the oligonucleotide from a crystallographic symmetry mate, and a monomeric TmEndoV mainly interacts with one strand of DNA. Therefore, we compared EndoV nuclease activity on single-stranded DNA and RNA. Because ribo-inosine phosphoramidite is not commercially available, we used deoxy-inosine exclusively. Oligonucleotides of DNA with a single deoxyinosine (DNA(dI)), DNA with the inosine followed by a ribo-adenosine (DNA(dIrA)), and RNA with a deoxyinosine (RNA(dI)) in an otherwise identical sequence of 18-nt in length were subjected to cleavage by the six EndoV proteins (Fig. 2A).

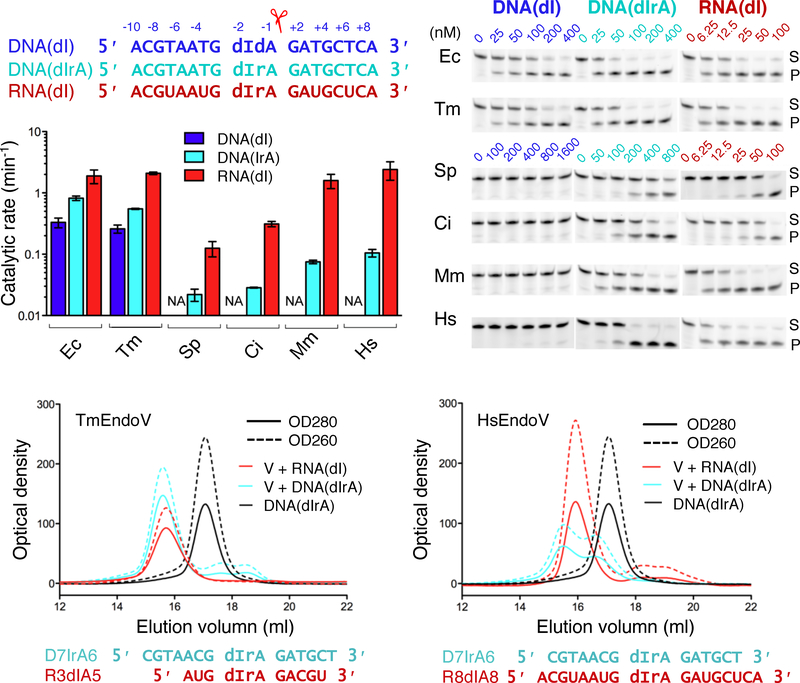

Figure 2.

Characterization of bacterial and eukaryotic EndoV and preference for DNA vs. RNA. (A) DNA and RNA oligo substrates used in EndoV cleavage assays. Nucleotide positions are marked above. (B) Cleavage assays of the three substrates shown in panel A by six EndoV in increasing concentrations. Protein concentrations were adjusted for each assay. The substrate (S) and product (P) bands are marked. (C) Quantification of each EndoV’s nuclease activities on different substrates (B) are in logarithm scale. Error bars are computed based on triplicate measurements. (D, E) Gel filtration analysis. TmEndoV binds DNA with one ribonucleotide (D7IrA6) as well as RNA with a deoxyinosine (R3dIA5) and fully shifts them to form protein complexes (D). HsEndoV binds RNA with a deoxyinosine (R8dIA8) well but only partially binds and shifts a DNA oligo with one ribonucleotide (D7IrA6) (E).

It was immediately clear that only bacterial EndoV cleave DNA(dI), and eukaryotic EndoV, including fungal and invertebrate homologs, do not (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, a single ribonucleotide 3′ to the inosine and 5′ to the scissile phosphate (DNA(dIrA)) improves the cleavage activity of EndoV regardless of bacterial or eukaryotic origin. Additional ribonucleotides in RNA(dI) further improve the EndoV activity of all species. The preference for RNA (with one dI) over DNA (except for one rA) increases through evolutionary time, from ~ 2–3 fold in bacteria (E. coli and T. maritima) to 10–20 fold in eukaryotes (pombe to humans) (Fig. 2C).

We further characterized enzyme-substrate association using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). TmEndoV formed complexes with DNA(dIrA) or RNA(dI) equally well (Fig. 2D). As evident from the TmEndoV-DNA complex structures (Dalhus et al., 2009), dI-containing DNA and RNA oligos of 10 nt in length or longer were fully shifted by TmEndoV (Fig. 2D, S2A). Although all eukaryotic EndoV are able to cleave DNA(dIrA), none fully shift the substrate to form a discrete protein-DNA(dIrA) complex on SEC. In contrast, each eukaryotic EndoV can form stable one-to-one complexes with RNA(dI) (Fig. 2E, S2B). In addition, eukaryotic EndoV, for example CiEndoV, showed length-dependent DNA(dIrA) binding and required at least 15 nts to form enzyme-substrate complexes (Fig. S2C).

Structures of TmEndoV-DNA(dIrA) complexes reveal the ribose effect

Because bacterial TmEndoV cleaves inosine-containing DNA with a ribonucleotide 5′ to the scissile phosphate better than with pure DNA, we investigated the atomic details of protein-DNA(dIrA) interactions. To stall catalysis, we co-crystallized the active-site mutant TmEndoV, D110N or E89Q, with a 12-nt DNA (D4IrA6, 4 nt upstream of dI and 6 nt downstream of rA). These structures were determined by molecular replacement and refined to 1.80 and 1.93 Å, respectively (Fig. 3A–B, S3A; Table S1). The TmEndoV protein can be divided into three structural components; the N-terminal helical extension (αA), the RNH core (β1-β2-β3-αB-β4-αC-β5-αF) and the C-terminal insertion domain (CTI), which consists of three β strands and one or two α helices ((αD)-β6-β7-β8-αE) and is inserted between β5 and αF in the RNH core (Fig. 1B). The entire protein, the inosine, the rA, and the two downstream nucleotides that frame the scissile phosphate superimpose well between the D110N and E89Q TmEndoV complexes and between the complexes with DNA(dIrA) and DNA only (PDB: 2W35 and 2W36) (Fig. 3B, S3A–B)

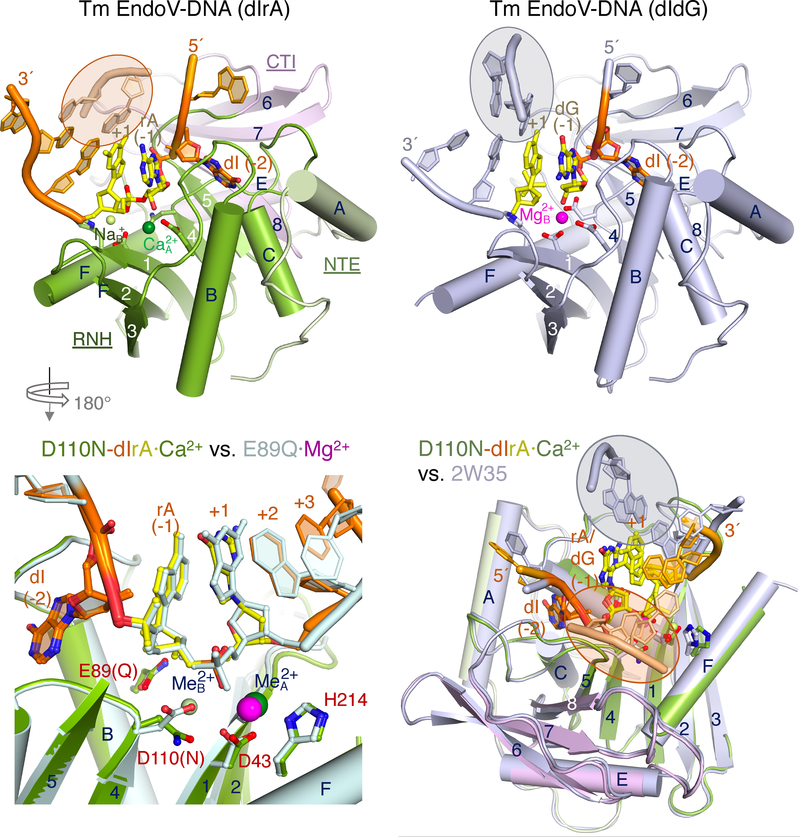

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of D110N and E89Q mutant TmEndoV complexed with DNA(dIrA). (A) Ribbon diagram of the TmEndoV(D110N)-D4IrA6 structure in light green (αA of NTE), green (RNH core), pink (CTI domain), and orange (DNA(dIrA)). Ca2+ and Na+ in the active site are shown as dark and light green spheres, respectively. The scissile phosphate is between yellow rA (−1) and +1 nucleotide. The complementary strand formed by crystallographic symmetry mate is circled in an orange oval. (B) Superposition of the D110N and E89Q active site, viewed from the back of panel A. (C) The published structure of TmEndoV in complex with DNA (2W35) is shown in the same orientation as in panel A. The complementary strand (circled in a grey oval) is also formed by crystallographic symmetry but assumes a different location and orientation from that shown in panel A. (D) Superposition of TmEndoV-DNA (2W35, grey overall except for dI (−2), dGs at −1 and +1) and TmEndoV-DNA(dIrA) structure. The complementary strand downstream of the scissile bond are highlighted in orange (dIrA) and grey ovals (dIdG).

Similar to RNase H1 and Ago (Nowotny et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009), two cations occupied the canonical metal-ion binding sites in TmEndoV (Fig. 3A), Ca2+ in A- and Na+ in B-site (verified by the anomalous signal and coordination geometry). In the E89Q mutant complex without the crucial second Glu that recognizes the ribonucleotide, the scissile phosphate is slightly displaced and the B-site metal ion is absent (Fig. 3B). The single Mg2+ ion detected in the TmEndoV-DNA product complex (PDB: 2W35) is near the canonical B site, and the empty A site is likely due to displacement of the 5′-phosphate product (Fig. S3B). The TmEndoV-DNA substrate complex (PDB: 2W36) (Dalhus et al., 2009) contains the active site D43A mutation, which perturbs both metal-ion binding sites and is thus devoid of all metal ions necessary for catalysis.

Large structural deviations between the DNA(dIrA) and pure DNA substrate in complex with TmEndoV occur outside of the catalytic center. The upstream DNA, which consists of 4 nts in the D110N-D4IrA6 structures simply folds back on itself by base stacking, while in 2W35 (DNA only) the upstream nucleotides form base pairs with a symmetry mate (Fig. S3C–D). In accordance with the finding that 2 or 7 nts preceding dIrA had no effect on enzyme binding (Fig. S2A), only one phosphate immediately 5′ upstream of the dI interacts with TmEndoV and the rest adopt very different structures. Downstream of the scissile phosphate, base pairs are formed between crystal symmetry mates in both structures (Fig. S3C–D), but the resulting duplexes are oriented differently in the dIrA versus all DNA context (Fig. 3A, C). In the presence of an rA the bases in the cleavage strands change orientations, and the complementary strand is rotated by 100° and shifted by 10 Å (Fig. 3D). This difference becomes meaningful when eukaryotic EndoV-DNA complex structures are considered (see below).

Structures of CiEndoV-DNA(dIrA) show contacts with the downstream duplex

We succeeded in crystallizing DNA(dIrA) with invertebrate CiEndoV, both WT (with Ca2+ ions, which support enzyme-substrate complex formation but not the cleavage reaction) and the catalytic inactive D234N variant (replacing the fourth catalytic carboxylate). Initial structures of CiEndoV-DNA (D9IrA7) complexes revealed distorted interactions of substrate with the active site (data not shown). After lengthening the DNA substrate downstream of dIrA to longer than 13 nts, several different co-crystal forms with the scissile phosphate in the active site were obtained. Two representative structures of WT CiEndoV-D9IrA13 and mutant D234N-D4IrA17 complexes, which diffracted X-rays to 3.0 and 2.30 Å, respectively, are described below (Table S1).

The two CiEndoV-DNA(dIrA) structures share common features despite different crystal symmetries and two or four EndoV molecules per asymmetric unit (ASU) (Fig. 4A–B). The 11 nts downstream of dIrA form an imperfectly self-complementary duplex via non-crystallographic symmetry, and each resulting DNA heteroduplex binds two CiEndoV molecules centered on the dIrA recognition motifs that flank the duplex (Fig. 4B, S4A–B). In the WT CiEndoV-D9IrA13 structure, each asymmetric unit contains two such dumbbell-shaped enzyme-substrate complex dimers and thus four EndoV-dIrA complexes. Each WT active site contains two Ca2+ ions and is superimposable with that of the TmEndoV(D110N)-D4IrA6 complex (Fig. 4A, S4C–D). In contrast with TmEndoV, which interacts with two nucleotides downstream of the scissile phosphate (Fig. 3, S3), each CiEndoV molecule contacts 7 bp of the DNA duplex (Fig. 4A–B). L78 (loop linking β7 and β8) and LEF (loop between αE and αF) in the C-terminal insertion domain (CTI) mediate the interaction with the non-cleavage (or complementary) strand in the downstream duplex. The DNA duplex adopts an AB hybrid form with the minor groove wider than canonical B-DNA and basepairs offset from the helical center (Nowotny et al., 2005). Binding of DNA duplex downstream of dIrA by CiEndoV explains the DNA-length dependence of crystallization. Interestingly, the DNA duplexes downstream of the cleavage site in the CiEndoV-DNA(dIrA) structures are similar to the short duplex of dIrA complexed with TmEndoV (Fig. 4A) but not the DNA-only substrate, which suggests that the single ribonucleotide helps orient the scissile phosphate, thus improving the endonuclease activity (Fig. 2B–C).

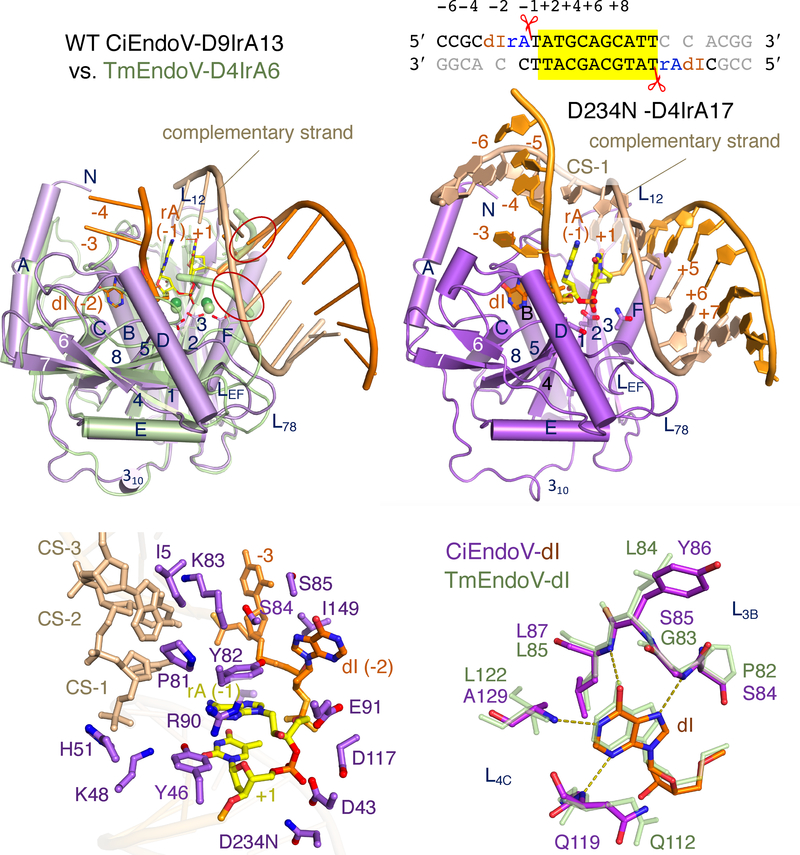

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of CiEndoV-DNA(dIrA) complexes. (A) Structure superposition of WT CiEndo (light purple and orange) and TmEndoV(D110N) (pale green) complexed with DNA(dIrA). Both are completed with two cations in the active site (green spheres). The similarly located cleavage and complementary strand are circled in red. (B) Structure of the D234N CiEndoV-D4IrA17 complex and diagram of D4IrA17 pseudo-duplex (highlighted in yellow). Loops L78 and LEF interact with the complementary strand downstream of the cleavage site. (C) Detailed interactions between CiEndoV and the unpaired duplex around dIrA. The −1 (rA) and +1 (dT) framing the scissile phosphate are highlighted in yellow. (D) A close-up view of the inosine-binding pocket in Ci (purple) and Tm EndoV (pale green). dI is shown as orange and multi-colored sticks.

In the D234N mutant CiEndoV-D4IrA17 structure, the complementary (non-cleavage) strand continues beyond the active site and forms three basepairs with the cleavage strand upstream of dI (−4 to −6) (Fig. 4B, S4A). The upstream portion mainly interacts with the NTE and CTI insertion domains (e.g. I5 and I149) (Fig. 4B–C). The active site is slightly misaligned and devoid of catalytic metal ions, possibly due to the combination of D234N mutation, the stringency of Mg2+ coordination and crystal lattice contacts. Nevertheless, the duplexes surrounding the inosine and cleavage site reveal how a double stranded substrate is bound by EndoV (Fig. 4B). Inosine (denoted as −2 from the cleavage site) and one base on each side of it are unpaired (Fig. 4C). Residues Y46, K48 and H51 on L12 (loop between β1 and β2) and P81, K83 and S84 on L3B (linking β3 and αB) help to maintain the ds-ss junctions surrounding the cleavage site (Fig. 4C). P81, Y82 and R90 (immediately before the catalytic E91) isolate the unpaired rA. Loops L3B (S84 to A88) and L4C (N119 to A129), which are highly conserved in eukaryotes and bacteria, surround the flipped-out inosine and form hydrogen bonds with main-chain amides (Fig. 4D). L3B, which includes the previously identified “wedge” (Dalhus et al., 2009; Nawaz et al., 2016b), performs the same role in deforming the substrate duplex and flipping out the hypoxanthine regardless of whether the wedge is composed of “PYIPGL” (TmEndpV) or “PYVSGF” (eukaryotic EndoV), because only main-chain atoms are involved (Fig. 1A, 4D).

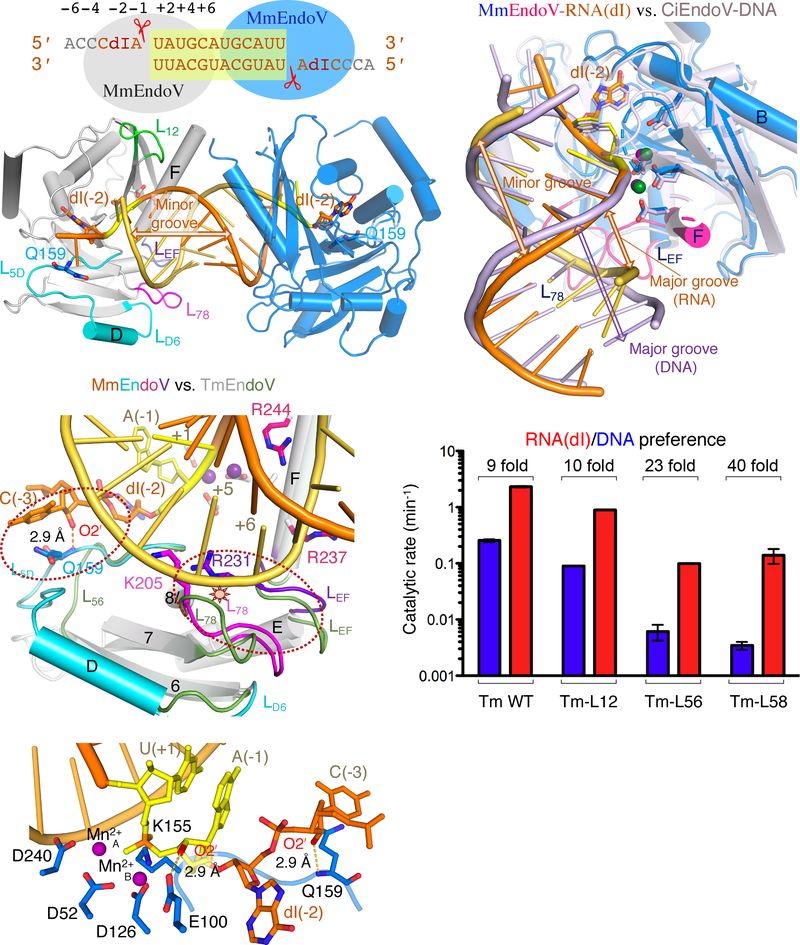

Structure of MmEndoV-RNA(dI) complexes and RNA recognition

Crystals of mouse EndoV (MmEndoV, residues 1–253) complexed with RNA oligos were subsequently grown with varying oligo length. The best crystals, which diffracted X-rays to 1.90 Å resolution (Table S1), were obtained with R9dIA12 (23 nt in length). Similar to the CiEndpV-DNA(dIrA) complexes, the RNA downstream of dIrA forms a 12 bp duplex and each dIrA at the duplex end binds one MmEndoV (Fig. 5A). In contrast to the A-B hybrid form of DNA(dIrA) complexed with CiEndoV, the RNA duplex is entirely A-form and characterized by a wide and shallow minor groove and narrow and deep major groove (Fig. 5A–B). Despite only 40% amino-acid sequence identity, the mouse and ciona EndoV structures superimpose well (rmsd of 0.82 Å over 191 pairs of Cα atoms) (Fig. 5B, S5A). The structure of MmEndoV complexed with RNA(dI) also superimposes remarkably well with the 1.5 Å apo HsEndoV structure (rmsd of 0.69 Å over 202 pairs of Cα atoms) and slightly better than with the apo MmEndoV (PDB: 5AOY) (Fig. S5B–C). The EndoV structures are apparently rigid, and upon substrate binding a few loops (L12, L3B, L4C, L56, and the N- and C-terminus) shift by 2 to 5 Å.

Figure 5.

The MmEndoV-RNA(dI) structure. (A) Diagram of 12 bp RNA duplex (highlighted in yellow) formed by two R9dIA12 oligos (Table S3). The disordered upstream nucleotides are colored grey (3 nts). Two MmEndoV bound to each RNA duplex (orange and yellow) are shown in blue and grey ribbon diagrams. Loops interacting with RNA surrounding dIrA and scissile phosphate are highlighted in different colors in the grey molecule. (B) Superposition of the CiEndoV-DNA(dIrA) (light pink) and MmEndoV-RNA(dI) (multicolor) structures. The protein structure and active site configuration are highly similar, but the DNA and RNA duplex downstream of the scissile phosphate differ. (C) Superimposed TmEndoV (green) and MmEndoV structures differ in loops L56, L78 and LEF. The extended MmEndoV-RNA interface due to lengthened L56 and L78 in MmEndoV are circled in red dashes, and the potential clash with RNA by TmEndoV due to the shorter L78 loop is marked by a red-yellow star. (D) A bar graph representing nuclease activities of mutant TmEndoV (Tm-L12, Tm-L56 and Tm-L58) with loops L12, L56, and L56 to L78 replaced by the equivalent regions of CiEndoV. These mutant TmEndoV have increased cleavage of RNA(dI) over DNA(dI) (Table S3) compared to WT TmEndoV. (E) RNA recognition from the cleavage site by E100 to the −3 (upstream) ribose by Q159. The two nucleotides flanking the scissile phosphate are shown in yellow. The O2′ at −1 and −3 are highlighted in red, and the hydrogen bonds they form with MmEndoV (blue) are shown as dashed line with the distances marked.

Because inosine recognition (by L3B and L4C) and the active site of all EndoV homologs are highly conserved, the RNA specificity of eukaryotic EndoV likely derives from regions outside of the active site that contact substrate. Loops L12, L56 (including the helix αD insertion) and L78, which have different lengths in bacterial and eukaryotic EndoV (Fig. 1A) and undergo conformational changes upon DNA or RNA binding (Fig. 4B, 5A, S5A), are possible determinants of RNA specificity. We replaced these three regions in TmEndoV with sequences from CiEndoV (Fig. 1A, 5C) and assayed their preference for RNA over DNA substrate. Tm-L12 with a 9-aa (loop L12) swap behaved like native TmEndoV (Fig. 5D). In contrast, Tm-L56 with a 34-aa (loop L56) and Tm-L58 with a 60-aa swap (including both loop L56 and L78) (Methods), respectively, exhibit increased preference for RNA compared to WT (Fig. 5D).

Structural superposition of the TmEndoV with the MmEndoV-RNA complex reveals that mouse EndoV gains extended interactions with the RNA duplex both upstream and downstream of dIrA due to insertions in L56 and L78 loops (Fig. 1A, 5C and S5D). In contrast, bacterial EndoV with shorter L56 and L78 has little substrate interactions upstream of the dIrA and would clash with the downstream complementary RNA strand (Fig. 5C). The insertions in L56 and L78 loop occur also in ciona and human (Fig. 1A). In addition, the mainchain amine of Q159 on mouse L56 makes a hydrogen bond with the 2′-OH of the ribonucleotide upstream of dI (Fig. 5E).

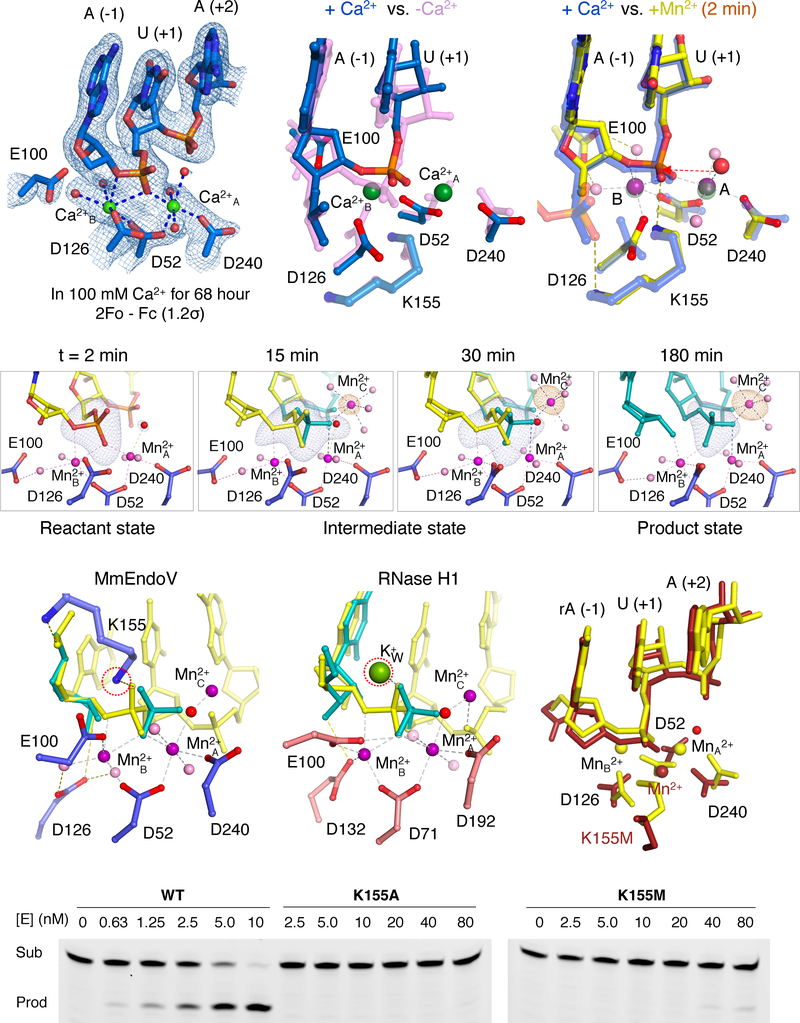

Three Mg2+ in EndoV catalysis

To visualize the chemistry of EndoV catalysis, we used the in crystallo reaction and freeze-and-trap method (Samara et al., 2017) to obtain atomic structures of EndoV reaction intermediates. Among our WT EndoV-substrate complex crystals, only the MmEndoV-RNA(dI) complex showed hydrolysis of a phosphodiester bond in crystallo. The MmEndoV-RNA(dI) co-crystals were grown in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+, which supports nucleic acid binding but not catalysis. Owing to 0.2 M tartrate in the crystallization buffer, which chelates Ca2+, no divalent cation was found in the active site. Ca2+ ions occupying the two canonical binding sites were observed only after soaking crystals in 100 mM Ca2+ and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) for 68 hours (Fig. 6A) and resulted in significant re-alignment in the active site (Fig. 6B). In contrast, soaking in 10 mM Mn2+, which is known for relaxed coordination requirements and its ability to substitute for Mg2+ (Yang et al., 2006), led to both A and B sites being fully occupied by Mn2+ in less than 2 min. Binding of two Mn2+ ions was accompanied by the scissile phosphate moving by 1.4 Å and becoming aligned for hydrolysis (Fig. 6C). Although the two Ca2+ ions were only slightly further apart (4.2 Å) than the two Mn2+ ions (3.9 Å), the catalytic residue D126 is aligned only in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

MmEndoV requires three Mg2+ and K155 for RNA cleavage. (A) The active site configuration with two Ca2+ ions (green sphere) bound. The 2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1.2 σ (blue mesh) is superimposed. (B) Superposition of the active site with (blue) and without Ca2+ ions (pink). The scissile phosphate and downstream duplex move by > 1.4 Å. (C) Superposition of the active site with two Mn2+ (10 mM Mn2+ for 2 min, yellow and multicolor) or Ca2+ (semi-transparent blue). (D) The in crystallo reaction time course of MmEndoV. Fo-Fc map calculated with the scissile phosphate omitted and contoured at 5.5 σ is superimposed with the structural model (yellow substrate, teal product, and blue EndoV). (E) The active site at reaction time of 10 min. (F) The RNase H1 active site with substrate, product, three Mn2+ and K+W bound (PDB: 6DPG). (G) Cleavage assays of R8dIA8 by WT, K155A and K155M mutant MmEndoV. (H) The misaligned K155M active site (after soaking in 10 mM Mn2+ for 100 min, dark red) is superimposed with that of WT (in 10 mM Mn2+ for 2 min, yellow).

RNA hydrolysis by MmEndoV occurred slowly in crystallo compared to in solution. The cleavage product 5′ phosphate was not detectible until 10 min after soaking in 10 mM Mn2+ and increased to 40% by 15 min (Fig. 6D, S6A). The amount of product eventually reached 100% by 180 min (Fig. S6B). During the conversion from substrate to product, little structural change was observed in MmEndoV or the RNA(dIA) substrate. However, a third Mn2+ appeared along with product formation. The identity of the three Mn2+ ions in each EndoV active site were verified by the anomalous diffraction (Fig. S6B). As observed in the RNase H1 and DNA Pol η reactions (Gao and Yang, 2016; Samara and Yang, 2018), the amount of the third Mn2+ increased proportionally with the cleavage product over the reaction time (Fig. 6D, S6C). The in crystallo reactions and involvement of the third divalent cation were observed in both MmEndoV-substrate complexes in each ASU and with 10 mM Mg2+ as well as with Mn2+ (Fig. S6D).

The third Mn2+ (Mn2+C) together with Mn2+A coordinates the nucleophilic water for in-line attack of the scissile phosphate by MmEndoV. As observed in DNA polymerases (η, β and μ) and RNase H1, this third divalent ion does not interact with the enzyme (Freudenthal et al., 2013; Gao and Yang, 2016; Jamsen et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2012; Samara and Yang, 2018). The only macromolecular ligand of Mn2+C is the pro-Rp oxygen 3′ to the scissile phosphate. The remaining five coordination sites are occupied by water molecules, one of which is the nucleophile and becomes a part of the 5′ phosphate product. Substrate assisted catalysis was suggested decades ago (Haruki et al., 2000; Jeltsch et al., 1993), and we visualize here how the EndoV substrate aids its own cleavage by capturing and coordinating the catalytic third divalent cation.

The in crystallo reaction rate catalyzed by MmEndoV is much slower than those by RNase H1 and DNA Pol η, for which reactions were typically complete within 3–5 min (Gao and Yang, 2016; Samara and Yang, 2018), while in solution EndoV is not slower than RNase H1. Among possible reasons, constraints exerted by the shared RNA duplex between two MmEndoV molecules stand out as a hindrance to the necessary movement for substrate to product conversion (Fig. S6E). Crystal lattice contacts may also create an artificial rate-limiting step (see below). Nevertheless, the identical location and coordination of the three Mn2+ ions observed in the MmEndoV and RNase H1 reactions (Samara and Yang, 2018) (Fig. 6E–F) indicates that the third divalent cation is required for the EndoV reaction as is in RNA hydrolysis by RNase H1.

Conserved reaction mechanism of EndoV, RNase H1 and DNA polymerases

In addition to the four carboxylates, the positively charged residues K155 and R244 appear to participate in MmEndoV catalysis. The main-chain amide and sidechain amine of K155 interact with the non-bridging oxygen atoms of the −1 (upstream) and scissile (+1) phosphates, respectively, and may stabilize the scissile phosphate during nucleophilic attack (Fig. 6E). The position of the amine of the K155 sidechain is superimposable with the K+W, which transiently appears with product formation in the RNase H1 reaction (Samara and Yang, 2018) (Fig. 6F). Mutation of K155 to Ala (K155A) reduced the MmEndoV nuclease activity to non-detectible in solution (Fig. 6G), while mutation to Met (K155M) retained ~1% catalytic activity (Fig. 6G). We analyzed in crystallo catalysis of K155M mutant MmEndoV and found a severely misaligned substrate and a single misplaced Mn2+ ion in the active site (Fig. 6H). The K155 sidechain appears critical for substrate alignment and A and B metal-ion binding in addition to neutralizing the highly negatively charged transition state as does the K+W in the RNase H1 reaction.

R244, which is adjacent to the last catalytic carboxylate D240 on helix αF, is conserved in eukaryotic EndoV and interacts with the phosphate backbone across the narrow major groove (Fig. 5C). To test whether it helps align the RNA substrate for cleavage, we made an R244A mutant MmEndoV and observed a 10-fold reduction of catalytic activity in solution (0.22 min−1 compared to 2.46 min−1 of WT). The location of R244 with its effect on catalytic rate is reminiscent of K196 in RNase H1 and R61 in DNA pol η (Gao and Yang, 2016; Samara and Yang, 2018), neither of which alter A and B metal-ion binding, but slow down binding of the third metal ion and the rate of product formation. However, the in crystallo reaction catalyzed by R244A MmEndoV was indistinguishable from that by WT (data not shown). The artificial rate-limiting step created by crystal constraints (Fig. S6E) may have masked the defects of R244A.

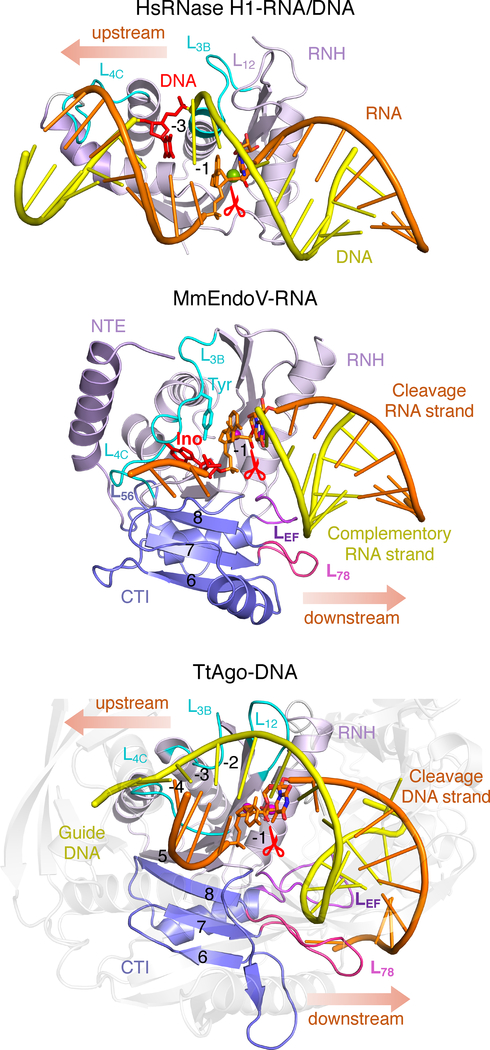

RNA recognition by EndoV, RNase H1 and Ago

Prototypical RNH catalytic domains, which are conserved among EndoV, RNase H1 and Ago (PIWI), generally prefer RNA substrates because the second of four catalytic carboxylates, Glu, interacts with the 2ʹ-OH of a ribose 5ʹ to the scissile phosphate (Fig. 6F). The presence of Glu does not necessitate a ribonucleotide 5ʹ to the scissile phosphate because DNA can adopt the A-form and mimic RNA. In parallel to bacterial EndoV, bacterial and archaeal Ago and PIWI proteins bind and cleave DNA (Wang et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2005). Interestingly, similar to EndoV (Fig. 2A–C), the presence of a ribonucleotide 5ʹ to the scissile phosphate also increases the nuclease activity of T. thermophilus Ago (Wang et al., 2009). Although E. coli EndoV has increased activity with the presence of a ribonucleotide (Fig. 2B), its biological function is clearly to remove inosine in DNA because, in its absence, both persistent inosine and inosine-induced A to G mutations increase (Schouten and Weiss, 1999; Weiss, 2008). Eukaryotic EndoV homologs use the enlarged CTI and Q159 equivalent to reinforce RNA specificity (Fig. 5).

When the conserved RNH domain and homologous active sites of EndoV, RNase H1 and Ago are superimposed (Fig. 7), how these related nucleases select the cleavage and complementary strand (known as the guide strand in Ago) become apparent. Recognition of the complementary DNA by RNase H1, which exclusively cleaves RNA in an RNA/DNA hybrid, is achieved by the discrimination against RNA two nucleotides upstream from the scissile phosphate using loops equivalent to L3B and L4C (Nowotny et al., 2005; Nowotny et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2018) (Fig. 7A). In EndoV L3B and L4C are involved in recognition of the flipped-out inosine (−2) and disrupting base pairs between the cleavage and complementary strands (Fig. 7B). The conserved Tyr on L3B specifically stacks with the −1 base and selects for purine over pyrimidine (Huang et al., 2001). In TtAgo, these two loops along with L12 specifically recognize three upstream deoxyribonucleotides (−2 to −4) on the guide strand by the C2ʹ-endo and narrow minor groove (Fig. 7C). Replacing these deoxyribonucleotides in the guide with ribonucleotides is detrimental to the nuclease activity of TtAgo (Wang et al., 2008). These loops, however, are not conserved in eukaryotic Ago proteins and thus may bind RNA guide instead.

Figure 7.

RNA versus DNA recognition by RNase H1, EndoV and Ago. (A) Recognition of RNA/DNA hybrid by human RNase H1 (PDB: 2QK9). RNase H1 uses loops L12, L3B and L4C (equivalent) to specify for a B-form DNA on the complementary strand three basepairs upstream of the scissile phosphate (−3, shown as red sticks). (B) The equivalent loops in EndoV (MmEndoV as an example) is used to recognize the inosine (Ino) and −1 ribonucleotide upstream of the scissile phosphate on the cleavage strand. However, EndoV has a C-terminal insertion domain (CTI, colored blue). Eukaryotic EndoV (ciona and mouse) use L56 to recognize the ribose upstream from the scissile phosphate (−3), and loops L78 and LEF in CTI to bind the downstream complementary strand, for which RNA is preferred. (C) In the TtAgo-DNA complex structure (PDB: 4NCB) the RNH core (PIWI domain) has both the loops for specifying the upstream guide DNA (complementary to the cleavage strand) and CTI and L78 and LEF to contact the downstream guide DNA or RNA (by eukaryotic Ago).

RNA recognition by ciona and mouse EndoV also occurs 5–7 bps downstream of the scissile phosphate on the complementary strand and is mediated by L78 and LEF of CTI. Small variations in these loops likely underlies evolution of EndoV function from DNA repair in bacteria to RNA editing in eukaryotes (Kuraoka, 2015) (Fig. 5C). CTI is found in all Ago proteins, while absent in RNase H1 (Fig. 7). In the structures of TtAgo and human Ago2 complexes, the downstream DNA and RNA duplexes adopt different conformations, AB hybrid and A-form, respectively, but both contact L78 and LEF equivalents (Fig. S7). In both EndoV and Ago, interactions with the downstream substrate involve phospho-sugar backbones only. The major groove of the RNA bound to MmEndoV is narrower (10 Å, A-form) than that of the DNA bound to CiEndoV (13.5 Å, hybrid form). Depending on the flexibility of L78 and LEF, both forms may be accommodated (Fig. 5B). Likewise, the RNA duplex bound to human Ago2 has a wider minor groove than the DNA duplex bound to TtAgo (Schirle et al., 2015; Sheng et al., 2014) (Fig. S7). The different lengths and sequences of L78, LEF and the adjacent L56 in TtAgo and HsAgo2 rationalize their different substrate preferences.

Discussion

In the structural and biochemical analyses of bacterial and eukaryotic EndoV homologs reported here we have established the structural features underlying the functional division between DNA repair by the bacterial enzymes and RNA processing by eukaryotic homologs. Surprisingly, the seemingly dramatic shift from DNA to RNA recognition is accomplished by subtle changes of variable loops outside of the catalytic center. The recognition motifs that we have identified in EndoV appear applicable to the related Ago and PIWI proteins, which also have the DNA and RNA duality.

With respect to catalytic mechanism, not only are the well-known two-metal ions coordinated by the catalytic carboxylates conserved among RNase H1, EndoV and Ago, but the third transiently bound Mg2+ or Mn2+ that is essential for product formation is also superimposable between RNase H1 and EndoV. In addition, K155 in EndoV and K575 in TtAgo bind the scissile phosphate and appear to function similarly to the K+ in RNase H1. The requirement for three divalent cations in RNA hydrolysis reactions is analogous to the DNA synthesis reactions, but the location of the third divalent cation differs. The third metal ion is associated with the leaving group in the DNA synthesis reactions (Gao and Yang, 2016), but in the hydrolysis reactions of RNase H1 and EndoV (Fig. 6E–F) it coordinates and likely activates the nucleophilic water. This difference is associated with the reversed direction of reactions (synthesis versus hydrolysis) and different nucleophiles (3′-OH versus free water), and may reflect the most energy-costing step in each reaction, which in the DNA synthesis reaction is to break the existing phosphodiester bond and in RNA degradation is to align and activate a nucleophilic water.

STAR Methods

Protein expression and purification

Genes encoding the full-length T. maritime (Tm, 225 residues), S. pombe (Sp, 252 residues) and C. instenalis EndoV (Ci, 245 residues) and the catalytic domain of mouse EndoV (Mm, 1–253 out of 338 residues) were chemically synthesized after codon-optimization for expression in E. coli (GenScript). E. coli nfi gene (encoding the full-length EcEndoV, 223 residues) was cloned from E. coli K-12 strain. These five endoV genes were cloned into a modified pET28a vector with a PreScission instead of Thrombin cleavage site after the His6 tag (Wang and Yang, 2009), either between NcoI and HindIII sites (Tm endoV, without any tag) or between NdeI and HindIII (Ec, Sp, Ci and Mm endoV, with a cleavable N-terminal His6 tag) (Table S2). Mutant forms were generated by PCR using the Quikchange kit (Agilent Genomics) (Table S2). Tm-L12, Tm-L56 and Tm-L58 were constructed by swapping coding regions of P47-L53, S140-S155, and S140-A177 of TmEndoV with S47-V55, S147-N174, and S147-K199 of CiEndoV, respectively. The EndoV proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Agilent Technologies) at 18°C overnight after indu ction with 0.5 mM IPTG. From the full-length WT HsEndoV clone made of pGEX-6p-2 (Morita et al., 2013), cysteine mutants and deletion of C-terminal unstructured region (residues 255–282) were made by PCR using the QuikChange kit (Agilent Genomics) (Table S2). WT, Cys mutant and C-terminal truncated HsEndoV proteins were expressed as described (Morita et al., 2013). Coding regions of all expression vectors were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

For protein purification, the first steps differed. For untagged TmEndoV, the supernatant of cell lysate was heated at 70°C for 2 0 min. After removing denatured proteins by centrifugation, the supernatant was purified over a HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare). For the His-tagged pombe, ciona, T. maritina and mouse EndoV and GST-tag human proteins, HisTrap HP and Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow columns (GE Healthcare) were used in the first step, respectively. Afterwards, the affinity tags were removed by PreScission protease, and every protein was further purified on Heparin HP and Superdex 200 columns (10/300 GL) (GE Healthcare) (Samara et al., 2017). Protease inhibitor tablets (Roche) and freshly made PMSF and Pepstatin were added to each cell lysate, and all purification procedures were carried out at 4°C unless otherwise specified. Purified proteins (Fig. S1C) were concentrated to 2–10 mg/ml in Amicon Ultra-4 filter units (SigmaAldrich) and stored at −25°C in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT and 30% glycerol.

Crystallization

The catalytic domain of HsEndoV (aa 1–254) with four Cys (C140S/C225S/C226A/C228S) was crystallized using 3.6 M sodium acetate as precipitant solution. All EndoV-substrate complex crystals were initially obtained using JCSG Core I suite (Qiagen) and grown by the vapor-diffusion method at 20°C. Protein and substrate were mixed at 1:1.1 to 1:1.2 molar ratio and concentrated to 5–6 mg/ml (protein concentrations determined by the Bradford method). Purified D110N or E89Q mutant TmEndoV protein was mixed with D4IrA6 (Table S3) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM NaCl. Crystals of the D110N mutant complexes were obtained using 0.1 M calcium acetate and 10% (w/v) PEG 3350 as precipitant solution. Crystals of E89Q mutant complexes were obtained using 0.2 M magnesium acetate, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and 15% (w/v) PEG8000 as precipitant solution. Purified WT CiEndoV and 9IrA13 (Table S3) were mixed in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM CaCl2 and 100 mM NaCl. Crystals were obtained using 0.2 M sodium acetate and 20% (w/v) PE3350. Crystals of D234N mutant CiEndoV complexed with D4IrA17 (Table S3) were obtained using 0.2 M potassium fluoride and 20 % (w/v) PEG 3350 as precipitant solution. Soaking of the D234N crystals in a stabilization buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 didn’t result in Mg2+ binding in the active site. Crystals of WT and mutant MmEndoV (aa 1–253) complexed with R9dIrA12 (Table S3) were grown using 0.2 M potassium sodium tartrate and 20–25% (w/v) PEG3350 as precipitant solution. Crystal preparation of in crystallo reactions catalyzed by MmEndoV has been described in detail (Samara et al., 2017). All crystals were flash cooled and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and structure determination

Most of diffraction data were collected at 22-BM with a Mar225 CCD detector (HsEndoV, TmD110N-D4IrA6, and MmEndoV-R9dIA12) or 22-ID with a Rayonix 300HS pixel detector (most of in crystallo reaction time course data) at the Advanced Photon Source at 1.00 Å wavelength. Two datasets were collected using an in-house Rigaku MicroMax-07HF X-ray generator and Saturn A200 CCD detector at 1.54 Å wavelength (CiEndoV-D9IrA13 and CiD234N-D4IrA17). All data were collected at 100 K and processed using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). HsEndoV and TmEndoV-DNA complex structure were solved by molecular replacement using the published TmEndoV structure (PDB 2W35) as a search model and MolRep in CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011). Once these structures were completely built and refined using COOT (Emsley et al., 2010) and PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010), they were used as initial models to solve CiEndoV-DNA and MmEndoV-RNA complex structures (Table S1).

DNA and RNA oligonucleotides

DNA and RNA oligonucleotides for crystallization and nuclease activity assay (see the list in Table S3) were synthesized by IDT and used after exchanging into Tris and EDTA buffer over a NAP-25 column.

EndoV nuclease activity assays

Reactions were carried out in 10 μl reaction buffer (20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 2% glycerol) with 1 μM 6-FAM labeled substrate and specified amount of EndoV at 37°C for 30 min. The stop solution (80% formamide, 20mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue) was added in an equal volume to terminate the reactions. Reaction products were resolved on 20% polyacrylamide − 7.5 M urea gels by electrophoresis in 1×TBE buffer, visualized on a Typhoon Trio (GE Healthcare), and quantified using ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare). Measurements were made in triplicate, based on which error bars were calculated.

Data deposition

All structure coordinates and X-ray diffraction data have been deposited at PDB with accession codes of 6OZE to 6OZS (Table 1, S1, and Key Resources).

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| EndoV | TmD110N-D4IrA6 | CiD234N-D4IrA17 | Mm, no Me2+ | Mm, Mn2+ (2min) | Mm, Mn2+ (30min) | MmK155M, Mn2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB | 6OZF | 6OZI | 6OZJ | 6OZL | 6OZO | 6OZQ |

| Data collection | ||||||

| Space group | P 2 21 21 | P 2 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 63.1, 75.6, 106.4 | 51.1, 81.4, 166.0 | 72.3, 73.6, 154.2 | 73.6, 72.5, 155.8 | 73.6, 72.4,155.6 | 71.2, 73.8, 154.7 |

| α, β, γ (º) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) 1 | 30.0 – 1.80 (1.83–1.80) | 50 – 2.3 (2.34–2.30) | 50 – 2.25 (2.29 – 2.25) | 50.0 – 2.10 (2.14 – 2.10) | 50.0 – 2.25 (2.29 – 2.25) | 50 – 2.15 (2.19 – 2.15) |

| Rsym or Rmerge 1 | 0.090 (0.778) | 0.053 (0.277) | 0.077 (0.542) | 0.117 (0.80) | 0.121 (0.511) | 0.135 (0.430) |

| I/σI) 1 | 15.0 (1.9) | 24.6 (5.5) | 26.3 (4.1) | 15.2 (1.3) | 16.5 (3.0) | 18.2 (2.0) |

| CC1/2 1 | (0.95) | (0.93) | (0.65) | (0.89) | (0.82) | |

| Complete (%) 1 | 99.3 (99.2) | 92.2 (70.6) | 100 (100) | 95.9 (73.1) | 94.1 (66.1) | 96.7 (76.7) |

| No of reflections 1 | 47534 (2329) | 29100 (1104) | 40002 (1944) | 47563 (1777) | 38507 (1330) | 43526 (1689) |

| Redundancy 1 | 4.5 (4.1) | 5.2 (5.2) | 7.3 (7.2) | 5.7 (2.5) | 10.6 (4.6) | 8.9 (3.4) |

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 28.1 – 1.80 | 30.0 – 2.3 | 42.9 – 2.25 | 35.8 – 2.10 | 43.0 – 2.25 | 42.7 – 2.15 |

| No. reflections 2 | 47481 (2334) | 29052 (1403) | 39914 (2026) | 47414 (2364) | 38398 (2016) | 43397 (2130) |

| Rwork / Rfree (%) | 16.7 / 19.8 | 17.4 / 20.1 | 15.6 / 19.4 | 17.6 / 21.1 | 16.8 / 21.1 | 17.4 / 20.9 |

| No. atoms | ||||||

| Protein / NA 3 | 3647 / 462 | 3902 / 753 | 3899 / 630 | 3832 / 650 | 3863 / 950 | 3811 / 630 |

| Water / Solvent | 330 / 33 | 439 / 20 | 368 / 50 | 154 / 42 | 192 / 36 | 132 / 36 |

| R.m.s deviations | ||||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| Bond angle (º) | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.951 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.948 |

| Average B factor | 30.9 | 36.9 | 34.9 | 53.4 | 55.8 | 50.2 |

| Ramachandran | ||||||

| Favored (%) | 98.7 | 97.8 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 96.8 | 97.8 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.3 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.2 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data in the highest resolution shell is shown in the parenthesis.

Number of reflections used in Rfree calculation is shown in the parenthesis

NA stands for nucleic acid

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Bacterial EndoV binds 1 and 2 nucleotides surrounding an inosine and repairs DNA.

Eukaryotic EndoV binds 2–4 and 8 bp RNA before and after an inosine, respectively.

RNA specificity of eukaryotic EndoV is determined by a few flexible loops.

RNA cleavage by mouse EndoV requires a third transiently bound Mg2+ or Mn2+.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to R. Craigie and D. Leahy for critical reading of the manuscript and to L. Tabak for generous support of N.L.S. This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK036144-11) to W.Y. and J.W., the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to N.L.S. (via L. Tabak), Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to I.K. (Grant Number 26650006).

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W (2013). Endonuclease V: an unusual enzyme for repair of DNA deamination. Cell Mol Life Sci 70, 3145–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM, and Crouch RJ (2009). Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J 276, 1494–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalhus B, Alseth I, and Bjoras M (2015). Structural basis for incision at deaminated adenines in DNA and RNA by endonuclease V. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 117, 134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalhus B, Arvai AS, Rosnes I, Olsen OE, Backe PH, Alseth I, Gao H, Cao W, Tainer JA, and Bjoras M (2009). Structures of endonuclease V with DNA reveal initiation of deaminated adenine repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demple B, and Linn S (1982). On the recognition and cleavage mechanism of Escherichia coli endodeoxyribonuclease V, a possible DNA repair enzyme. J Biol Chem 257, 2848–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, and Levanon EY (2018). A-to-I RNA editing - immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal BD, Beard WA, Shock DD, and Wilson SH (2013). Observing a DNA polymerase choose right from wrong. Cell 154, 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, and Yang W (2016). Capture of a third Mg(2)(+) is essential for catalyzing DNA synthesis. Science 352, 1334–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates FT 3rd, and Linn S (1977). Endonuclease V of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 252, 1647–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Ding Y, and Weiss B (1997). nfi, the gene for endonuclease V in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 179, 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruki M, Tsunaka Y, Morikawa M, Iwai S, and Kanaya S (2000). Catalysis by Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI is facilitated by a phosphate group of the substrate. Biochemistry 39, 13939–13944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lu J, Barany F, and Cao W (2001). Multiple cleavage activities of endonuclease V from Thermotoga maritima: recognition and strand nicking mechanism. Biochemistry 40, 8738–8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamsen JA, Beard WA, Pedersen LC, Shock DD, Moon AF, Krahn JM, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, and Wilson SH (2017). Time-lapse crystallography snapshots of a double-strand break repair polymerase in action. Nat Commun 8, 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A, Alves J, Wolfes H, Maass G, and Pingoud A (1993). Substrate-assisted catalysis in the cleavage of DNA by the EcoRI and EcoRV restriction enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 8499–8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Tohashi K, Iwai S, and Kuraoka I (2016). Inosine-specific ribonuclease activity of natural variants of human endonuclease V. FEBS Lett 590, 4354–4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn CD, and Joshua-Tor L (2013). Eukaryotic Argonautes come into focus. Trends Biochem Sci 38, 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka I (2015). Diversity of Endonuclease V: From DNA Repair to RNA Editing. Biomolecules 5, 2194–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majorek KA, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Steczkiewicz K, Muszewska A, Nowotny M, Ginalski K, and Bujnicki JM (2014). The RNase H-like superfamily: new members, comparative structural analysis and evolutionary classification. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 4160–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Shibutani T, Nakanishi N, Nishikura K, Iwai S, and Kuraoka I (2013). Human endonuclease V is a ribonuclease specific for inosine-containing RNA. Nat Commun 4, 2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Zhao Y, Yamagata Y, Hua YJ, and Yang W (2012). Watching DNA polymerase eta make a phosphodiester bond. Nature 487, 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz MS, Vik ES, Berges N, Fladeby C, Bjoras M, Dalhus B, and Alseth I (2016a). Regulation of Human Endonuclease V Activity and Relocalization to Cytoplasmic Stress Granules. J Biol Chem 291, 21786–21801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz MS, Vik ES, Ronander ME, Solvoll AM, Blicher P, Bjoras M, Alseth I, and Dalhus B (2016b). Crystal structure and MD simulation of mouse EndoV reveal wedge motif plasticity in this inosine-specific endonuclease. Sci Rep 6, 24979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, and Yang W (2005). Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell 121, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Ghirlando R, Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ, and Yang W (2007). Structure of human RNase H1 complexed with an RNA/DNA hybrid: insight into HIV reverse transcription. Mol Cell 28, 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, and Minor W (1997). Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara NL, Gao Y, Wu J, and Yang W (2017). Detection of Reaction Intermediates in Mg(2+)-Dependent DNA Synthesis and RNA Degradation by Time-Resolved X-Ray Crystallography. Methods Enzymol 592, 283–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara NL, and Yang W (2018). Cation trafficking propels RNA hydrolysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirle NT, Sheu-Gruttadauria J, Chandradoss SD, Joo C, and MacRae IJ (2015). Water-mediated recognition of t1-adenosine anchors Argonaute2 to microRNA targets. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten KA, and Weiss B (1999). Endonuclease V protects Escherichia coli against specific mutations caused by nitrous acid. Mutat Res 435, 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng G, Zhao H, Wang J, Rao Y, Tian W, Swarts DC, van der Oost J, Patel DJ, and Wang Y (2014). Structure-based cleavage mechanism of Thermus thermophilus Argonaute DNA guide strand-mediated DNA target cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 652–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarts DC, Makarova K, Wang Y, Nakanishi K, Ketting RF, Koonin EV, Patel DJ, and van der Oost J (2014). The evolutionary journey of Argonaute proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro T, and Kanaya S (2009). Ribonuclease H: molecular diversities, substrate binding domains, and catalytic mechanism of the prokaryotic enzymes. FEBS J 276, 1482–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Kim MS, Li H, Wang J, and Yang W (2018). Structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase cleaving RNA in an RNA/DNA hybrid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik ES, Nawaz MS, Strom Andersen P, Fladeby C, Bjoras M, Dalhus B, and Alseth I (2013). Endonuclease V cleaves at inosines in RNA. Nat Commun 4, 2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, and Yang W (2009). Structural insight into translesion synthesis by DNA Pol II. Cell 139, 1279–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juranek S, Li H, Sheng G, Tuschl T, and Patel DJ (2008). Structure of an argonaute silencing complex with a seed-containing guide DNA and target RNA duplex. Nature 456, 921–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juranek S, Li H, Sheng G, Wardle GS, Tuschl T, and Patel DJ (2009). Nucleation, propagation and cleavage of target RNAs in Ago silencing complexes. Nature 461, 754–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B (2001). Endonuclease V of Escherichia coli prevents mutations from nitrosative deamination during nitrate/nitrite respiration. Mutat Res 461, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B (2008). Removal of deoxyinosine from the Escherichia coli chromosome as studied by oligonucleotide transformation. DNA Repair (Amst) 7, 205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, et al. (2011). Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Lee JY, and Nowotny M (2006). Making and breaking nucleic acids: two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol Cell 22, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, and Steitz TA (1995). Recombining the structures of HIV integrase, RuvC and RNase H. Structure 3, 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Hatahet Z, Melamede RJ, and Kow YW (1994). Purification and characterization of a novel deoxyinosine-specific enzyme, deoxyinosine 3’ endonuclease, from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 269, 16260–16268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YR, Pei Y, Ma JB, Kuryavyi V, Zhadina M, Meister G, Chen HY, Dauter Z, Tuschl T, and Patel DJ (2005). Crystal structure of A. aeolicus argonaute, a site-specific DNA-guided endoribonuclease, provides insights into RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage. Mol Cell 19, 405–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Hao Z, Wang Z, Li Q, and Xie W (2014). Structure of human endonuclease V as an inosine-specific ribonuclease. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 70, 2286–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Jia Q, Zhou C, and Xie W (2015). Crystal structure of E. coli endonuclease V, an essential enzyme for deamination repair. Sci Rep 5, 12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.