Significance

In recent years, systematic research efforts have led to the preclinical development of antibody-based therapeutics that confer potent antiviral activity against Ebola virus (EBOV). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against virus pathogens depend on their interaction with specialized leukocyte receptors (Fcγ receptors [FcγRs]) to confer antiviral functions. FcγR engagement by IgG antibodies induces leukocyte activation and mediates pleiotropic effector functions to control virus infection. Here, we examined the contribution of FcγR engagement to the antibody-mediated protection against EBOV infection in unique animal models of EBOV infection. Our findings suggest that anti-EBOV antibodies exhibit differential requirements for FcγR engagement to confer protection from EBOV infection, guiding the design of optimized antibody-based therapeutics with maximal protective efficacy.

Keywords: antibodies, effector function, immunoglobulin, Fc receptors, immunotherapy

Abstract

Ebola virus (EBOV) continues to pose significant threats to global public health, requiring ongoing development of multiple strategies for disease control. To date, numerous monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target the EBOV glycoprotein (GP) have demonstrated potent protective activity in animal disease models and are thus promising candidates for the control of EBOV. However, recent work in a variety of virus diseases has highlighted the importance of coupling Fab neutralization with Fc effector activity for effective antibody-mediated protection. To determine the contribution of Fc effector activity to the protective function of mAbs to EBOV GP, we selected anti-GP mAbs targeting representative, protective epitopes and characterized their Fc receptor (FcγR) dependence in vivo in FcγR humanized mouse challenge models of EBOV disease. In contrast to previous studies, we find that anti-GP mAbs exhibited differential requirements for FcγR engagement in mediating their protective activity independent of their distance from the viral membrane. Anti-GP mAbs targeting membrane proximal epitopes or the GP mucin domain do not rely on Fc–FcγR interactions to confer activity, whereas antibodies against the GP chalice bowl and the fusion loop require FcγR engagement for optimal in vivo antiviral activity. This complexity of antibody-mediated protection from EBOV disease highlights the structural constraints of FcγR binding for specific viral epitopes and has important implications for the development of mAb-based immunotherapeutics with optimal potency and efficacy.

During the widespread Ebola epidemic in 2014, affecting multiple West Africa countries over its 3-y course, more than 11,000 deaths from Ebola virus (EBOV) disease were recorded from a total of almost 30,000 cases (1). Although EBOV disease is currently contained in several of the affected countries and no new cases are being reported, the possibility for new outbreaks in the future remains high. Indeed, recent reports from the Democratic Republic of Congo indicate that an EBOV outbreak is currently unfolding in the eastern part of the country. Since August 2018, 1,000 new EBOV disease cases have been reported, accounting for more than 600 deaths. Without drastic measures to halt its spread, the current EBOV outbreak could soon escape control, with casualties reaching unprecedented levels.

The high mortality rate of EBOV disease as well as the ease of EBOV transmission within human populations have prompted the research community to focus on the development of therapeutic strategies to control EBOV infection. Indeed, systematic research efforts, which intensified in the aftermath of the 2014 Ebola epidemic, have led to the isolation, characterization, and preclinical development of antibody-based therapeutics that confer potent antiviral activity against EBOV (2–8). For example, ZMapp, an experimental therapeutic comprising 3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)—2G4, 4G7, and c13C6—that target distinct nonoverlapping epitopes on the EBOV envelope glycoprotein (GP), fully protected nonhuman primates (NHPs) from lethal EBOV challenge (4). In view of these encouraging preclinical efficacy data, ZMapp was also used as a treatment option in humans to control EBOV disease during the 2014 outbreak (9). These findings suggest that GP represents a key target to limit EBOV infection and have set a paradigm for the use of anti-GP mAbs as therapeutic modalities against EBOV disease. Over the past few years, hundreds of new mAbs against diverse antigenic sites on EBOV GP have been isolated from survivors of the last outbreak (10–18). Many of these mAbs exhibit potent neutralizing activity against EBOV and have demonstrated potent prophylactic and therapeutic activity in small animal and NHP models of EBOV infection, supporting their potential clinical use to control human EBOV disease (11, 12, 16, 19).

The capacity of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody to confer antiviral activity in vivo is the result of the coordinated activity of its 2 functional domains: (1) the Fab domain, which mediates highly specific antigenic recognition to prevent viral entry, fusion, or release; and (2) the Fc domain, which modulates the functional activity of effector leukocytes by engaging Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) expressed on their surface (20, 21). Fc–FcγR interactions mediate numerous effector functions to control viral infection, including the opsonization and clearance of viral particles by innate FcγR-expressing leukocytes, including neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages; the elimination of virus-infected cells through cytotoxic and phagocytic mechanisms by natural killer cells and macrophages, respectively; and the induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses through dendritic cell FcγR engagement (22–24). The importance of Fc–FcγR interactions in the antibody-mediated protection against infection has been established since the 1980s (reviewed in ref. 21), and substantial evidence from diverse viral pathogens, including influenza and HIV-1, supports a critical role for the Fc domain function in the IgG-mediated antiviral activity (25–29). Mechanistic studies using mAbs against these pathogens have previously dissected the requirements for FcγR engagement to achieve maximal in vivo protective activity, thereby guiding the development of mAbs with improved therapeutic efficacy through modulation of their Fc domain function (26, 27, 29).

In the context of EBOV, studies using anti-GP mAbs have previously suggested that Fc-mediated functions likely contribute to their in vivo protective activity, supported by the description of nonneutralizing anti-GP mAbs with the capacity to confer protection from infection in animal models (4, 8, 30, 31). These studies challenge the notion that the in vitro neutralization activity of anti-GP mAbs will predict their in vivo therapeutic efficacy and support that the selection of mAbs that would advance into clinical development for potential use in future EBOV outbreaks not be based solely on their neutralization activity but should include their capacity to engage and activate the appropriate FcγR pathways. While recent reports (32, 33) recognize the significance of Fc-mediated effector functions as a parameter of protection, the inconsistent results and inappropriate experimental models fail to provide a systematic characterization of the FcγR-mediated mechanisms by which anti-GP mAbs confer antiviral activity. For example, in an attempt to identify the correlates of antibody-mediated protection against EBOV infection, an international collaborative effort from the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Immunotherapeutic Consortium assembled a large collection of mAbs (168) that target diverse antigenic sites on the EBOV GP (32). These mAbs were evaluated in vitro for their epitope specificity, neutralization potency, and Fc effector function as well as for their in vivo protective activity in mouse models of EBOV infection (32, 33). Not surprisingly, studies on the Fc effector activity revealed substantial heterogeneity in the effector responses among the tested mAbs. However, it is doubtful whether such heterogeneity in the Fc effector function truly reflects the differential epitope specificities and neutralization potency of the anti-GP mAbs. It is more likely attributed to the diverse origin of the tested mAbs, as the panel consisted of both human (102) and murine (66) mAbs, as well as different IgG subclasses within each species. As a result of this heterogeneity, the antibodies intrinsically have vastly different FcγR binding profiles to the human FcR-expressing cells used in the reported assays independent of their Fab binding specificities (20, 34). Such differences more likely explain the heterogeneous Fc effector responses that were observed. Similarly, previous attempts to identify the precise mAb epitopes on EBOV GP that activate FcγR pathways to mediate antiviral activity resulted in contradictory findings, stemming primarily from the use of unmatched in vitro systems or in vivo models, which albeit their widespread use, do not reflect the unique diversity of human FcγRs (15). Thus, appropriate in vivo studies have not been reported, and it is still unknown, based on those reports, whether anti-GP mAbs that target diverse antigenic sites on GP exhibit differential requirements for Fc–FcγR interactions to mediate in vivo protection from EBOV infection.

In this study, we selected a representative panel of human anti-GP mAbs that had been previously isolated from EBOV disease survivors (18) and examined the contribution of Fc effector function to their in vivo protective activity in mouse models of EBOV infection using mice deficient in murine FcγRs and exclusively expressing the human receptors, thereby recapitulating the complexity of the human system (35). This approach overcomes the significant interspecies differences in the FcγR structure, distribution, expression, and function between humans and mice. Indeed, compared with humans, mammalian species, like mice and NHPs, express a limited set of FcγRs, which exhibits a vastly distinct expression profile and different affinities for human IgG antibodies (36).

Systematic analysis of the in vivo potency of the various anti-GP mAbs in FcγR humanized mice revealed that specific mAbs confer antiviral activity independent of their Fc domain function, whereas others relied on Fc–FcγR interactions for their capacity to protect against EBOV infection. These specificities were not correlated with epitope distance from the viral membrane, a finding consistent with similar studies performed with the influenza HA protein (26, 29) and HIV gp160 (27), supporting a more complex model of Fab interactions influencing Fc accessibility for FcγRs. These findings reveal that anti-GP mAbs exhibit differential requirements for FcγR engagement to confer in vivo protection from EBOV infection, guiding the design of Fc-engineered mAbs with maximal therapeutic efficacy through Fc optimization to engage and activate appropriate FcγR-mediated signaling pathways.

Results

Generation and Characterization of Anti-EBOV GP mAbs with Differential FcγR Affinity.

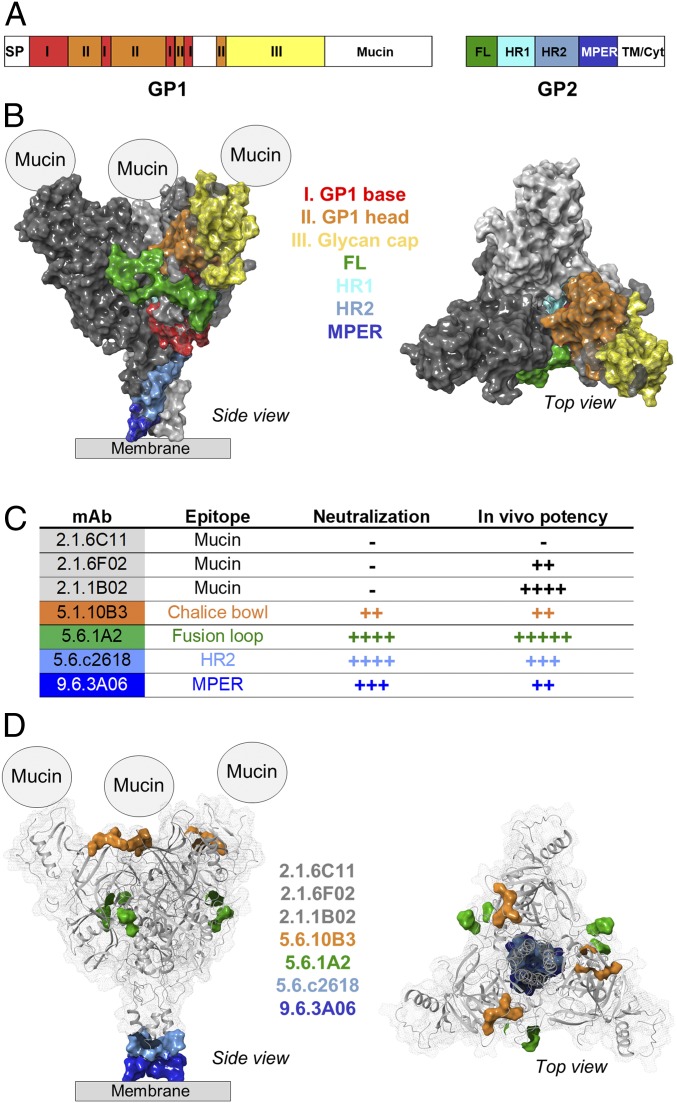

The EBOV GP trimer comprises 3 heterodimeric units of GP1 and GP2 domains, which mediate viral attachment and fusion, respectively (Fig. 1 A and B). Systematic analysis of the B-cell responses against EBOV infection in survivors of the 2014 West African Ebola disease outbreak in previous studies led to the isolation of numerous mAbs that target various epitopes on GP1 and GP2 and exhibit potent protective activity against EBOV infection (10, 11, 13, 18, 37). To study the FcγR-mediated pathways that contribute to the protective activity of anti-EBOV GP mAbs, we selected a representative panel of human mAbs against GP1 and GP2 as summarized in Fig. 1C. These human IgG1 mAbs target distinct epitopes on EBOV GP, including (1) the mucin domain (2.1.6C11, 2.1.6F02, and 2.1.1B02 mAbs); (2) the chalice bowl (5.1.10B3), which comprises the interface of the GP1 head and glycan cap and is involved in viral attachment; (3) the fusion loop (5.6.1A2), a domain on GP2 that participates in viral fusion; and (4) epitopes on the membrane proximal region of the EBOV GP, including the HR2 domain (5.6.c2618) and the MPER region (9.6.3A06). The selected mAbs exhibited differential in vitro neutralization activity and in vivo potency to protect mice against lethal EBOV challenge. Additionally, recent mutational analyses have identified the specific epitopes that these mAbs recognize (depicted in Fig. 1D) (18).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the EBOV GP structure and epitope specificities of the selected anti-GP mAbs. EBOV GP is organized into a trimeric structure, with each monomer comprising a heterodimer of GP1 and GP2 subunits. (A) Schematic representation of the functional domains of GP1 and GP2 subunits. (B) Structure of the GP trimer (Protein Data Bank ID code 5JQ3) depicting the organization of the monomers (light and dark gray) as well as the various domains of GP1 and GP2. For the study of the mechanisms of IgG-mediated protection against EBOV infection, a panel of mAbs from Ebola survivors was selected. These mAbs target distinct epitopes on the GP trimer and exhibit differential neutralization activity (−, >100 μg/mL; ++, <20 μg/mL; +++, <0.2 μg/mL; ++++, <0.1 μg/mL PRNT50) and in vivo protective activity (−, nonprotective; ++, >200 μg; +++, >50 μg; ++++, >20 μg; +++++, >5 μg to achieve >50% survival) as assessed in a mouse model of EBOV infection. Overview of the functional properties (C) of the selected mAbs and mapping of their targeting epitopes (D). Mucin domains are missing from available crystal structures, and the precise epitopes for antimucin mAbs have not been determined.

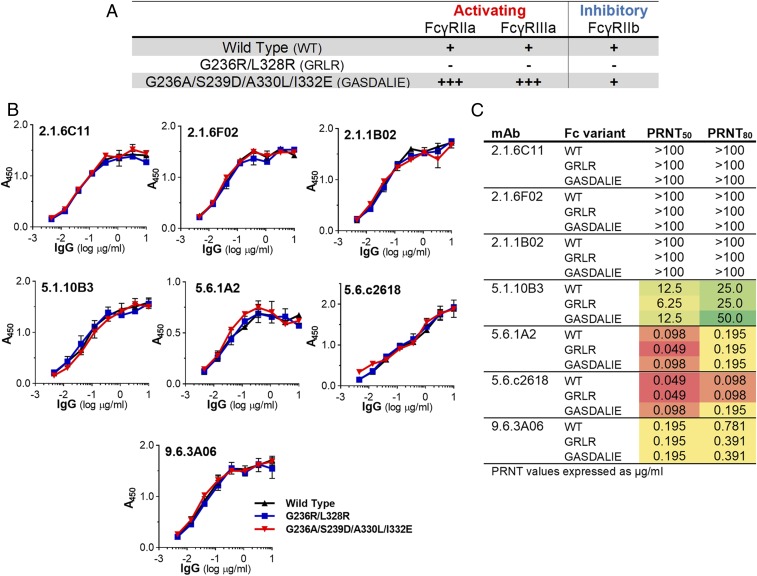

To determine whether the protective activity of anti-EBOV GP mAbs depends on Fc–FcγR interactions, we generated human IgG1 Fc domain variants with diminished (G236R/L328R [GRLR]) or enhanced (G236A/S239D/A330L/I332E [GASDALIE]) affinities for human FcγRs (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S1). Comparison of the in vivo activity of these Fc domain variants represents a robust approach for the systematic characterization of the Fc effector mechanisms that contribute to the function of protective IgG antibodies (25–28, 38, 39). Wild-type human IgG1 and Fc domain variants (GRLR or GASDALIE) of the selected anti-EBOV GP mAbs were expressed in mammalian cells and characterized for their antigenic specificity (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2) to ensure that any changes in their Fc domains do not impact their Fab-mediated activities. Additionally, we evaluated the in vitro neutralization activities of anti-EBOV GP mAb Fc domain variants in standardized plaque reduction neutralization assays (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). As expected, the antigenic specificity and neutralization potency was comparable among the different Fc domain variants of anti-EBOV GP mAbs, despite their differential capacity to engage human FcγRs (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Generation and characterization of Fc domain variants of anti-GP mAbs. To determine the contribution of Fc effector function to their protective activity against EBOV infection, anti-GP mAbs were expressed as Fc domain variants with differential affinity for the various human FcγR classes. (A) Overview of the FcγR binding profiles of the different Fc domain variants (affinity values are presented in SI Appendix, Table S1) (−, no binding; +, baseline binding; +++, >10-fold over baseline). (B) Anti-GP mAb Fc variants were characterized for their epitope specificity by ELISA using recombinant GP (strain Zaire/Mayinga). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2 show experiments using GP from different EBOV strains. (C) Neutralization activity of Fc domain variants of anti-GP mAbs was quantified by plaque reduction neutralization assays, and neutralization titers (in micrograms per milliliter; PRNT50 and PRNT80 indicate 50 or 80% inhibitory concentration, respectively) were determined. Results represent the mean of >1 experiment performed in duplicates (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). WT, wild type.

Minimal Contribution of Fc Effector Function to the Protective Activity of Antimucin mAbs.

To determine the role of the Fc domain function of antimucin mAbs during the IgG-mediated protection against EBOV infection, we evaluated the activity of Fc domain variants of antimucin mAbs in a mouse model of EBOV infection. In contrast to studies that commonly use attenuated EBOV strains or EBOV pseudoviruses to assess the in vivo activity of anti-EBOV mAbs, we selected an experimental system that utilizes fully virulent EBOV strains, which induce pathological manifestations comparable with those observed in humans on EBOV infection. This model, which has been extensively used by several groups for the study of EBOV infection in vivo (10, 18, 37, 40–46), involves the use of fully virulent, mouse-adapted EBOV strains that have been previously generated by passaging EBOV to progressively older suckling mice (47). To overcome the substantial interspecies differences between humans and mice in the FcγR expression pattern among effector leukocytes as well as their affinity for human IgG antibodies, EBOV challenge studies were performed in FcγR humanized mice (35), a fully immunocompetent mouse strain that expresses all human FcγR classes in lieu of their mouse counterparts and exhibits an FcγR expression pattern identical to that observed among human effector leukocytes (35, 39, 48). EBOV infection of FcγR humanized mice was accomplished by the inoculation of mouse-adapted EBOV (100 plaque forming units [pfu] intraperitoneally), and disease severity was monitored over a 3-wk period.

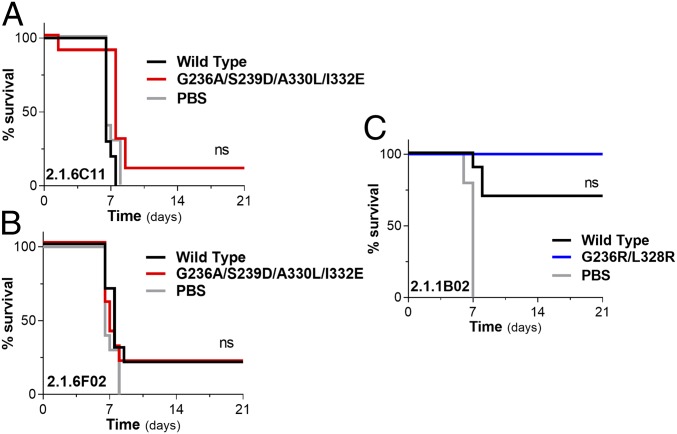

To investigate the role of FcγR-mediated pathways in the function of antimucin mAbs, we selected 3 mAbs—2.1.6C11, 2.1.6F02, and 2.1.1B02—that exhibited variable in vivo potency, despite their minimal in vitro neutralization activity (50% plaque reduction neutralization titer [PRNT50] > 100 μg/mL) (Figs. 1C and 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C). Titration studies using increasing amounts of 2.1.6C11 revealed that, even at high doses (500 μg intraperitoneally 1 d before challenge), this mAb failed to rescue mice from lethal EBOV challenge (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). To determine the basis for the low potency of this antibody, we compared the in vivo protective activity of 2.1.6C11 expressed as either wild-type human IgG1 (baseline human FcγR affinity) or an Fc variant with enhanced affinity for activating human FcγRs and improved cytotoxic activity (GASDALIE) (Fig. 2A). Despite its increased FcγR affinity, the 2.1.6C11 GASDALIE variant exhibited marginally improved in vivo potency and failed to protect mice against EBOV infection (Fig. 3A). Similarly, we observed no significant improvement in the in vivo protective activity for the GASDALIE variant of another antimucin mAb (2.1.6F02), which in contrast to 2.1.6C11, exhibits moderate in vivo potency, despite its poor neutralization activity (Fig. 3B). Finally, we evaluated a highly potent antimucin mAb (2.1.1B02), which like 2.1.6C11 and 2.1.6F02, exhibited poor in vitro neutralization activity and determined whether its in vivo activity resulted from productive FcγR interactions. Based on the results from dose-titration studies (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C), we selected the lowest dose at which wild-type human IgG1 2.1.1B02 exhibits optimal protection (100 μg) and compared its activity with the 2.1.1B02 GRLR variant, which exhibits diminished binding to all FcγR classes. Comparison of the in vivo potency of 2.1.1B02 Fc domain variants revealed comparable activity between wild-type IgG1 and Fcnull (GRLR) variants (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these findings from 3 antimucin mAbs with variable in vivo potency revealed that Fc–FcγR interactions have no role in the in vivo activity of mAbs that target the mucin domain of GP and suggest that the variable potency of these antibodies results from epitope specificity and not Fc-mediated effector activity.

Fig. 3.

Protective antimucin mAbs mediate antiviral activity independent of Fc–FcγR interactions. The in vivo protective activity of antimucin mAb Fc variants with differential FcγR binding affinity was evaluated in FcγR humanized mice to determine the contribution of Fc domain function to their antiviral activity. Evaluation of the in vivo antiviral activity of Fc domain variants of the antimucin mAbs 2.1.6C11 (A) and 2.1.6F02 (B) expressed as either wild-type human IgG1 or the GASDALIE Fc variant, which exhibits improved affinity for activating FcγRs. (C) Comparison of the protective activity of 2.1.1B02 mAb Fc variants (wild type: baseline FcγR binding; GRLR: diminished FcγR binding). mAbs (200 μg for 2.1.6C11 and 2.1.6F02; 100 μg for 2.1.1B02) were administered intraperitoneally 1 d prior to lethal challenge of FcγR humanized mice with 100 pfu mouse-adapted EBOV, and survival was monitored for 3 wk; n = 10 per experimental group. Log rank (Mantel–Cox) test. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C shows mAb dose titration studies. ns, not significant.

Anti-GP mAbs Targeting Membrane Proximal Epitopes Do Not Rely on Fc–FcγR Interactions for In Vivo Antiviral Activity.

Studies on the Fc effector function of IgG antibodies against influenza hemagglutinin (HA) have previously determined that strain-specific mAbs against the globular head domain mediate antiviral activity independent of Fc–FcγR interactions, whereas those that target the stem region of the HA rely on Fc effector activity to mediate protection against influenza infection (26, 49, 50). However, not all antihead HA antibodies are FcγR independent; head epitopes that confer broad specificity against a variety of strains display FcγR dependence (29), arguing against a simple model of head vs. stalk FcγR dependence. Mechanistic studies revealed that the capacity of anti-HA antibodies to engage FcγRs and confer Fc effector functions is largely determined by the more complex fine structure of the HA trimer and the specific epitope that is targeted, which thus influences interactions with FcγR-expressing effector leukocytes (49, 50). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that, in the context of anti-GP mAbs, the structural organization of the GP trimer determines their capacity to engage FcγRs as previously reported for influenza HA. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the in vivo protective activity of 2 anti-GP mAbs, 5.6.c2618 and 9.6.3A06, which target the HR2 and MPER regions of GP2, respectively (Fig. 1D). We compared the capacity of Fc domain variants of these mAbs with either diminished (GRLR) or enhanced (GASDALIE) affinity for human FcγRs to protect FcγR humanized mice against lethal EBOV challenge. Since in initial dose-titration studies, the HR2 mAb 5.6.c2618 potently protected mice against EBOV infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D), we assessed whether Fc–FcγR interactions contribute to its antiviral function by comparing the in vivo protective activity of wild-type human IgG1 with the Fcnull variant (GRLR), which exhibits diminished binding to all FcγRs. Mice treated with the Fcnull variant (GRLR) of 5.6.c2618 demonstrated comparable survival compared with the wild-type human IgG1-treated ones, suggesting that the in vivo antiviral activity of the 5.6.c2618 mAb is not dependent on FcγR-mediated pathways (Fig. 4A). Similarly, when we assessed the in vivo protective activity of the MPER mAb 9.6.3A06, we observed that Fc engineering for enhanced FcγR affinity failed to improve its antiviral potency, with wild-type IgG1 and GASDALIE variants of 9.6.3A06 exhibiting comparable activity (Fig. 4B). These findings are in contrast to observations made for the MPER epitopes of HIV gp160 (21) and challenge the simplistic model that the membrane proximity of the targeted epitopes determines the requirements for FcγR pathways for the antiviral activity of anti-GP mAbs, as mAbs targeting either membrane-distal (antimucin) or proximal (anti–HR-2, anti-MPER) epitopes have the capacity to mediate in vivo protective activity independent of Fc–FcγR interactions.

Fig. 4.

Fc effector function does not contribute to the protective activity of mAbs targeting the membrane proximal region of EBOV GP. To assess whether mAbs targeting the HR2 (5.6.c2618) or the MPER domains (9.6.3A06) of EBOV GP rely on Fc–FcγR interactions for their in vivo antiviral function, Fc domain variants of these mAbs with either diminished (GRLR) or enhanced (GASDALIE) affinity for the various human FcγRs were generated, and their protective activity was evaluated in FcγR humanized mice following lethal challenge with mouse-adapted EBOV (100 pfu 1 d post-mAb administration; 150 μg intraperitoneally). Protective activity of 5.6.c2618 (A) and 9.6.3A06 (B) was compared between wild-type human IgG1 and Fc variants to assess for FcγR dependence; n = 10 per experimental group. Log rank (Mantel–Cox) test. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 D and E shows mAb dose titration studies. ns, not significant.

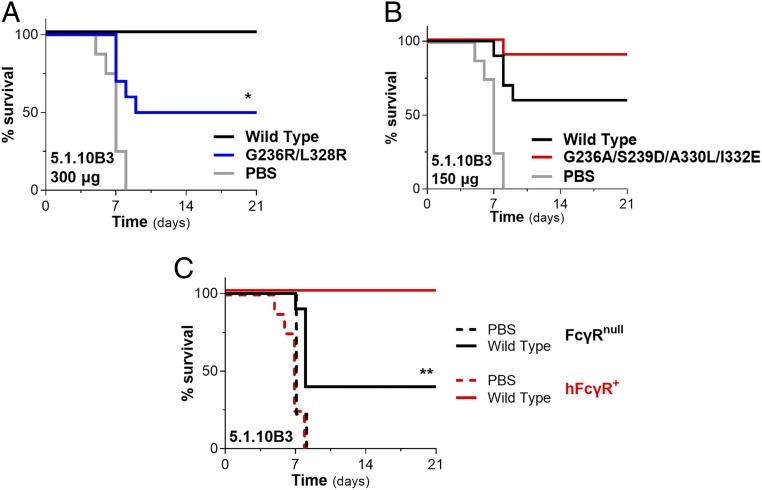

Antibodies Against the GP Chalice Bowl Require FcγR Engagement for Optimal In Vivo Antiviral Activity.

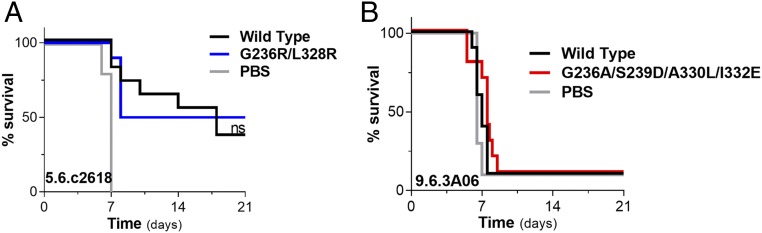

Extending our analysis to additional anti-GP mAbs, we next evaluated the in vivo protective activity of the 5.1.10B3 mAb, which targets the GP chalice bowl, a region on GP1 that participates in viral attachment to host cells (Fig. 1D). When we compared the capacity of wild-type human IgG1 and Fcnull (GRLR) variants of 5.1.10B3 to protect FcγR humanized mice against lethal challenge with mouse-adapted EBOV, we observed significant reduction in the in vivo potency for the GRLR variant compared to its wild-type human IgG1 counterpart, suggesting a role for Fc–FcγR interactions in the antiviral activity of 5.1.10B3 mAb (Fig. 5A). Based on this finding, we next determined whether engineering of the Fc domain for enhanced FcγR affinity also results in improved in vivo potency. Using an mAb dose at which wild-type human IgG1 confers suboptimal activity (150 μg), we evaluated the protective activity of the GASDALIE variant of 5.1.10B3. Compared with wild-type human IgG1-treated mice, treatment with the GASDALIE variant resulted in improved survival, consistent with a role for FcγR engagement in the antiviral activity of the 5.1.10B3 mAb (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Antibodies against the GP chalice bowl require FcγR engagement for in vivo antiviral activity. The capacity of the anti-GP mAb 5.1.10B3, which targets the chalice bowl region of GP1 (GP1 head/glycan cap interface) to protect against EBOV infection, was evaluated in FcγR humanized (hFcγR+) mice. Titration studies established the optimal and suboptimal mAb dose required for protection (SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). (A) Comparison of the in vivo protective activity of 5.1.10B3 wild-type human IgG1 and Fc variant (GRLR) with diminished FcγR binding affinity. mAb (300 μg) was administered intraperitoneally 1 d prior to challenge with mouse-adapted EBOV. (B) Using a suboptimal mAb dose (150 μg), the antiviral potency of 5.1.10B3 expressed as either wild-type human IgG1 or Fc engineered (GASDALIE variant) for enhanced FcγR affinity was evaluated in vivo. (C) Follow-up experiments to confirm the contribution of Fc–FcγR interactions to the in vivo protective activity of the 5.1.10B3 mAb were performed using mouse strains deficient for FcγRs. The antiviral activity of 5.1.10B3 (wild-type human IgG1; 300 μg) was evaluated in FcγR-deficient (FcγRnull) and hFcγR+ mice; n = 9 to 10 per experimental group. Log rank (Mantel–Cox) test. *P = 0.0113 wild type vs. GRLR; **P = 0.0046 wild-type 5.1.10B3-treated FcγRnull vs. hFcγR+ mice.

To provide additional evidence on the requirements of FcγR pathways for the in vivo potency of the 5.1.10B3 mAb, follow-up experiments were performed in mouse strains deficient in all classes of FcγRs (FcγRnull) (35). Compared with FcγR humanized mice, FcγRnull mice exhibited comparable susceptibility to EBOV infection (Fig. 5C). However, when we assessed the capacity of 5.1.10B3 mAb (wild-type human IgG1; 300 μg) to protect against EBOV infection, we observed impaired potency in the FcγRnull mice compared with FcγR humanized mice (Fig. 5C). In summary, these findings support a clear role for Fc effector activity in modulating the antiviral function of protective mAbs that target the GP chalice bowl.

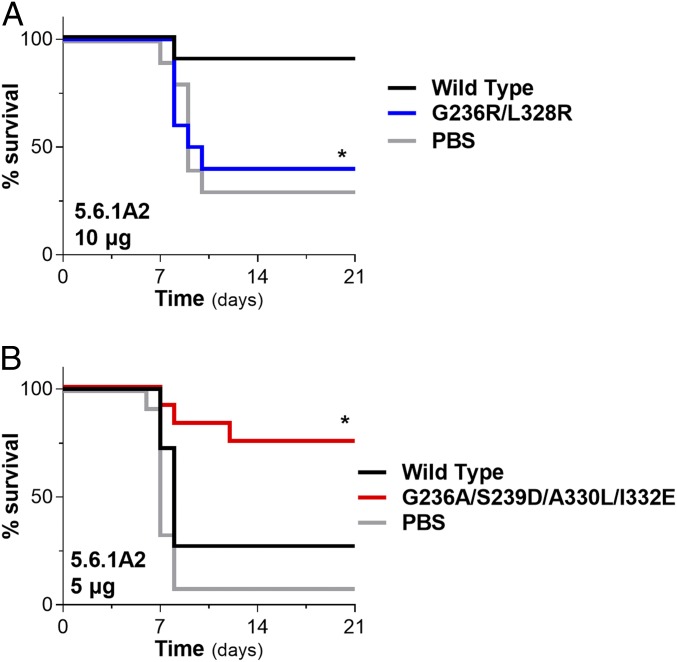

Neutralizing Anti-GP Fusion Loop mAbs Depend on Fc–FcγR Interactions to Confer Antiviral Activity.

A key region on the GP trimer is the fusion loop located at the GP2 subunit (Fig. 1 A and B). Antibodies against the fusion loop often exhibit potent neutralizing activity, highlighting the significance of this epitope during the EBOV infection of target cells. To assess whether the neutralizing antifusion loop mAb 5.6.1A2 relies on Fc effector function to mediate protective activity, we compared the in vivo potency of Fc domain variants of 5.6.1A2 with either diminished (GRLR) or enhanced (GASDALIE) affinity for FcγRs. Compared with wild-type human IgG1, which exhibited potent protective activity, the GRLR variant of 5.6.1A2 failed to protect mice from EBOV infection, suggesting that Fc–FcγR interactions are critical for the antiviral function of this mAbs (Fig. 6A). Likewise, when we assessed the in vivo potency of 5.6.1A6 at a suboptimal dose (5 μg; determined based on dose titration studies [SI Appendix, Fig. S4G]), we observed that, while wild-type human IgG1 provided minimal protection against EBOV infection, the GASDALIE variant of 5.6.1A2 exhibited improved antiviral activity, reflecting the capacity of this Fc variant to engage human activating FcγRs with increased affinity (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these findings suggest that the in vivo protective activity of the antifusion loop mAb 5.6.1A2 is dependent on Fc–FcγR interactions and that engineering of the Fc domain for enhanced FcγR affinity results in improved in vivo potency.

Fig. 6.

The in vivo protective activity of neutralizing anti-GP fusion loop mAbs is dependent on Fc effector function. To assess whether Fc effector functions contribute to the in vivo antiviral activity of the antifusion loop mAb 5.6.1A2, Fc domain variants with diminished (GRLR) or enhanced (GASDALIE) FcγR binding affinity were evaluated in a mouse model of EBOV infection. (A) Comparison of the protective activity of wild-type and Fcnull (GRLR) variants of 5.6.1A2 (10 μg intraperitoneally 1 d prior to EBOV infection [100 pfu] of FcγR humanized mice). *P = 0.023 wild type vs. GRLR. (B) Wild-type human IgG1 and Fc-engineered variants (GASDALIE) for enhanced FcγR affinity were evaluated at a suboptimal dose (5 μg; based on mAb titration studies) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4G); n = 10 to 12 per experimental group. Log rank (Mantel–Cox) test. *P = 0.0214 wild type vs. GASDALIE.

Discussion

For several viral pathogens, the in vitro neutralizing activity of antibodies is commonly used to predict their capacity to protect in vivo; however, an ever-increasing body of experimental data supports a more nuanced model, in which Fc-dependent mechanisms, along with the Fab-mediated neutralization, synergize to mediate antiviral protection as evidenced by recent studies on the function of antibodies against influenza and HIV-1 (20, 26–28, 49, 51). Early studies on the function of mAbs against EBOV provided substantial evidence to support that the neutralization activity of these mAbs poorly correlated with their in vivo potency. For example, components of the ZMapp mAb mixture include nonneutralizing mAbs, which are critical for the ZMapp-mediated protection against infection (4). Additionally, both neutralizing and nonneutralizing mAbs have been shown to confer protection against EBOV infection in animal models of EBOV disease (4, 8, 11, 13, 18), whereas KZ52, one of the first neutralizing anti-EBOV mAbs isolated, exhibited poorly protective activity in NHPs, despite its potent in vitro neutralization activity (52). In preparation for future EBOV outbreaks, the development of novel mAb-based therapeutics is necessary; therefore, there is a critical need for a comprehensive understanding of the exact antibody features that are associated with protection to guide the selection and optimization of novel therapeutic mAbs with superior potency.

Studies on the role of the Fc domain function in the protective activity of antiviral IgG antibodies necessitate the use of well-defined experimental systems to overcome the inherent complexity of the pleiotropic antiviral functions that IgG antibodies mediate in vivo to protect the host from infection. For example, while in vitro assays are commonly used for the high-throughput screening of the Fc function of mAbs, they fail to recapitulate the diversity of the FcγR-expressing effector leukocyte populations present in in vivo conditions. Likewise, in vitro cytotoxicity and phagocytosis assays do not take into account a significant component of the function of antiviral mAbs, which is the Fab-mediated neutralization. As a result, there is often discrepancy between the in vitro effector function and the in vivo protective activity, which has also been reported for anti-GP mAbs (16). Even in vivo experimental systems present significant limitations stemming from the substantial interspecies differences in the structure and function of FcγRs between humans and other mammalian species that are commonly used as EBOV disease models and include mice, ferrets, guinea pigs, and NHPs (36). Indeed, several key properties of human FcγRs, relating to the expression pattern among effector leukocytes, their signaling activity, and affinity for human IgG antibodies, are unique to humans and are not found in mammalian species commonly used in biomedical research. Therefore, the study of the Fc domain function of human IgG antibodies can only be accomplished under species-matched conditions using animal strains that express the full array of human FcγRs. Lastly, since the in vivo protective activity of antiviral mAbs represents the outcome of the functions mediated by both the Fab and the Fc domains, the activity of these mAbs needs to be evaluated over a wide dosing range to determine the precise contribution of the Fc domain function. Indeed, at high mAb doses, the Fab-mediated neutralizing activity is expected to be dominant, masking the contribution of the Fc effector function to the mAb antiviral activity.

By taking into account all of these limitations, this study performed a comprehensive evaluation of the in vivo protective activity of anti-GP mAbs and determined the requirements for Fc–FcγR interactions in the mAb-mediated antiviral function. We carefully selected a panel of mAbs that target representative epitopes on the GP trimer and determined the contribution of FcγR-mediated pathways to their antiviral function using FcγR humanized mice and well-characterized Fc domain variants with differential FcγR binding affinity. These studies revealed that mAbs against specific epitopes, namely the chalice bowl and the fusion loop on GP1 and GP2, respectively, require FcγR engagement to mediate protective activity. In contrast, neutralizing antibodies against membrane-proximal epitopes, including the HR2 and the MPER, showed minimal FcγR dependence, likely conferring their antiviral activity through viral neutralization mechanisms. Likewise, when we assessed 3 different antimucin mAbs with variable in vivo protective activity, we observed that these mAbs did not require FcγR engagement for their antiviral function. Interestingly, since all of the antimucin mAbs that we tested were nonneutralizing, the precise mechanisms by which these mAbs confer protection in vivo remain unclear. It is likely that nonneutralizing antimucin mAbs control viral replication through mechanisms that cannot be replicated in the experimental setting of the in vitro neutralization assay. Alternatively, complement-mediated pathways could be proposed as a potential mechanism for their antiviral function; however, this assumption is rather unlikely, as the Fc domain variants tested in this study (GRLR and GASDALIE) exhibit minimal C1q binding affinity and cannot activate complement (27, 53, 54). Overall, our analysis revealed differential requirements for FcγR engagement for anti-GP mAbs to mediate antiviral activity in vivo. Such requirements did not correlate with the in vitro neutralization potency or the location of the epitope targeted by these mAbs, especially in relation to the proximity of these epitopes to the viral membrane. Although the precise mechanisms that account for the observed differences in the requirements for FcγR engagement of anti-Ebola GP mAbs to confer in vivo protective antiviral function remain unknown, it is likely that steric hindrance of mAbs that target specific epitopes on GP might limit accessibility of their Fc domains to FcγRs, thereby exhibiting reduced capacity to engage and activate FcγR pathways: a phenomenon previously described for antiinfluenza mAbs that target the globular head domain (26, 49).

Previous studies on the Fc effector function of anti-GP mAbs suggested membrane proximity of the targeted epitopes as a major determinant for these mAbs to engage FcγRs and mediate Fc effector functions (15, 32). This assumption was based on studies on antiinfluenza HA mAbs, which reported that, while mAbs that target the membrane-proximal stem domain of HA exhibit potent Fc effector function, those against the membrane-distant HA globular head have limited capacity to engage FcγRs: a phenomenon attributed to steric hindrance of the Fc domain and the intrinsic structure and function of the HA trimer (26, 49, 50). However, in formulating this model, the authors failed to take into the account that the observations that they evaluated related only to strain-specific, antihead antibodies; head epitopes that result in broad protection were FcγR dependent (29), revealing that the specific structure of the bound antibody was significant in its ability to engage FcγRs and not its distance from the membrane.

In the context of anti-EBOV GP mAbs, recent studies reported conflicting findings: one study concluded that maximal Fc effector function is mapped to epitopes farthest from the viral membrane (32), whereas others demonstrated that mAbs against the membrane-proximal regions, but not against the glycan cap, were capable of mediating Fc effector function (15). Such discrepancy, which likely reflects the inherent limitations of the in vitro assays used to assess Fc effector function of anti-GP mAbs, suggests that membrane proximity per se cannot predict the capacity of anti-GP mAbs to mediate Fc effector functions. Since the envelope proteins from different viral pathogens feature unique structural and functional characteristics that likely influence Fc effector function, results from one viral system cannot be extrapolated to other viruses and used to propose a generalized mechanism on the determinants that regulate IgG function across diverse pathogens. Like any viral pathogen, EBOV is characterized by a unique set of features, and as this study revealed, protective anti-GP mAbs confer antiviral activity with differential requirements for FcγR engagement. Indeed, our findings support that the Fab and Fc domains of anti-GP mAbs contribute differentially to their in vivo protective activity. Since our studies were limited to single antibodies in a monovalent formulation, follow-up studies are necessary to dissect the role of Fc effector function of multivalent formulations comprising oligoclonal mAb combinations (12). Therefore, prior to clinical development, comprehensive evaluation of the Fc effector function is warranted for any therapeutic mAb candidate or mAb combinations to assess for FcγR dependency and determine which specific FcγRs are essential for its antiviral function. These studies would allow the rational selection of Fc domain variants with altered affinity for specific FcγRs and optimized effector function, leading to the development of mAbs with superior clinical efficacy and enhanced therapeutic potency.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Anti-GP mAbs.

Plasmids containing the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of the selected anti-GP mAbs were obtained from Carl Davis, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, and they were subcloned to mammalian expression vectors (Abvec) encompassing the constant region of the human IgG1 heavy chain or the human κ light chain. Fc domain variants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using specific primers based on the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit II (Agilent Technologies). Plasmid sequences were validated by direct sequencing (Genewiz). Antibodies were generated by transient transfection of 293T cells following previously described protocols (55). Briefly, heavy- and light-chain expression plasmids were cotransfected to 293T cells, and recombinant IgG antibodies were purified from cell-free supernatants by affinity purification using Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). Purified proteins were dialyzed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sterile filtered (0.22 μm). Purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomasie blue staining and was estimated to be >90%. Endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) contamination was quantified by the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay, and levels were <0.005 EU/mg.

Anti-EBOV GP Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

For GP-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), recombinant soluble EBOV GP (strains Zaire/Mayinga, Kissidougou-C15, or ManoRiver-G3686.1; Sinobiological) was immobilized (2 μg/mL) into high-binding 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc), and following overnight incubation at 4 °C, plates were blocked with PBS + 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin for 2 h. After blocking, plates were incubated for 1 h with IgG antibodies, and plate-bound IgG was detected by horseradish-peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Fcγ specific; Jackson Immunoresearch). Plates were developed using the 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine 2-component peroxidase substrate 2 kit (KPL), and reactions were stopped with the addition of 1 M phosphoric acid. Absorbance at 450 nm was immediately recorded using a SpectraMax Plus spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices), and background absorbance from negative control samples was subtracted.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis of FcγR Affinity.

All experiments were performed with a Biacore T200 SPR system (Biacore; GE Healthcare) at 25 °C in HBS-EP+ buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.005% [vol/vol] surfactant P20). Recombinant protein G (GE Healthcare) was immobilized at 2,000 RU on a CM5 biosensor chop using amine coupling chemistry at pH 4.5. IgG antibodies (10 μg/mL) were captured on the protein G surface, and recombinant soluble human FcγR ectodomains (Sinobiological) were injected to the flow cells at 30 μL/min, with the concentration ranging from 2,000 to 7.8 nM (1:2 successive dilutions). Association time was 120 s followed by a 300-s dissociation step. At the end of each cycle, sensor surface was regenerated with a glycine HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 2.0; 50 μL/min, 30 s). Background binding to blank immobilized flow cells was subtracted, and affinity constants were calculated using BIAcore T200 evaluation software (GE Healthcare) using the 1:1 Langmuir binding model.

Neutralization Assay.

The in vitro neutralization potency of anti-GP mAbs was assessed in plaque reduction assays as previously described (10). Briefly, mAbs were serially diluted in complete Minimal Essential Medium (MEM) (MEM supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1× antibiotic–antimycotic). EBOV was incubated with the diluted mAb for 1 h at 37 °C. The antibody–virus mixture was subsequently added to duplicate 6-well plates with 90 to 95% confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle rocking. Following infection, the cell monolayer was overlaid with 0.5% agarose in complete MEM medium, and plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 7 d. Cells were then stained with 4 to 5% neutral red (18 to 24 h at 37 °C), and plaques were quantified. PRNT50 and PRNT80 titers were determined as the IgG concentration (micrograms per milliliter) at which a 50 or 80% reduction, respectively, in the number of plaques was observed compared with control wells (no IgG added).

In Vivo Model of EBOV Infection.

All mouse experiments were performed in compliance with federal laws and institutional guidelines and have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). Research was conducted under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, Public Health Service policy, and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facility where this research was conducted is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (56). The protective activity of anti-EBOV GP mAbs was evaluated in a mouse model of EBOV infection previously developed at the USAMRIID and involved the use of mouse-adapted EBOV strains, which were generated by serial passaging EBOV (Zaire) in progressively older suckling mice (47). For mAb titration studies, female C57BL/6 6- to 8-wk-old mice (Charles River) were injected intraperitoneally with anti-GP mAbs (diluted in PBS), and 1 d later, mice were infected with 100 pfu mouse-adapted EBOV (administered intraperitoneally). For studies evaluating the role of human FcγRs in the mAb-mediated protection against EBOV infection, female adult (6- to 10-wk-old) FcγR humanized or FcγRnull mice (deficient for all FcγR classes [35]) were used, and mAb treatment and infection were performed as described above. Mice were monitored daily for 15 to 21 d postinfection to assess disease severity, and mortality was recorded.

Statistical Analysis.

Results from multiple experiments are presented as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 software (Graphpad), and P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. For in vivo protection experiments, survival rates were analyzed with the log rank (Mantel–Cox) test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Smith, E. Lam, P. Bartel, and H. Lee (Rockefeller University) as well as A. Piper, J. Shamblin, A. Kimmel, and T. Sprague (USAMRIID) for excellent technical help and C. Davis (Emory University) for providing the plasmids encoding the anti-GP mAbs and information on their epitope specificities. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the US Army. We acknowledge support from the Rockefeller University. These studies were supported by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Contract W31P4Q-14-1-0010.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1911842116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Baseler L., Chertow D. S., Johnson K. M., Feldmann H., Morens D. M., The pathogenesis of Ebola virus disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 12, 387–418 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dias J. M., et al. , A shared structural solution for neutralizing ebolaviruses. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1424–1427 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audet J., et al. , Molecular characterization of the monoclonal antibodies composing ZMAb: A protective cocktail against Ebola virus. Sci. Rep. 4, 6881 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu X., et al. , Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb. Sci. Rep. 3, 3365 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marzi A., et al. , Protective efficacy of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in a nonhuman primate model of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. PLoS One 7, e36192 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shedlock D. J., et al. , Antibody-mediated neutralization of Ebola virus can occur by two distinct mechanisms. Virology 401, 228–235 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J. E., et al. , Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 454, 177–182 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson J. A., et al. , Epitopes involved in antibody-mediated protection from Ebola virus. Science 287, 1664–1666 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey R. T., Jr, et al. ; PREVAIL II Writing Group; Multi-National PREVAIL II Study Team , A randomized, controlled trial of ZMapp for Ebola virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1448–1456 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornholdt Z. A., et al. , Isolation of potent neutralizing antibodies from a survivor of the 2014 Ebola virus outbreak. Science 351, 1078–1083 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corti D., et al. , Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody. Science 351, 1339–1342 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wec A. Z., et al. , Development of a human antibody cocktail that deploys multiple functions to confer pan-ebolavirus protection. Cell Host Microbe 25, 39–48.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wec A. Z., et al. , Antibodies from a human survivor define sites of vulnerability for broad protection against ebolaviruses. Cell 169, 878–890.e15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wec A. Z., et al. , A “Trojan horse” bispecific-antibody strategy for broad protection against ebolaviruses. Science 354, 350–354 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilinykh P. A., et al. , Asymmetric antiviral effects of ebolavirus antibodies targeting glycoprotein stem and glycan cap. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007204 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilchuk P., et al. , Multifunctional pan-ebolavirus antibody recognizes a site of broad vulnerability on the ebolavirus glycoprotein. Immunity 49, 363–374.e10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flyak A. I., et al. , Broadly neutralizing antibodies from human survivors target a conserved site in the Ebola virus glycoprotein HR2-MPER region. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 670–677 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis C. W., et al. , Longitudinal analysis of the human B cell response to Ebola virus infection. Cell 177, 1566–1582.e17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bornholdt Z. A., et al. , A two-antibody pan-ebolavirus cocktail confers broad therapeutic protection in ferrets and nonhuman primates. Cell Host Microbe 25, 49–58.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bournazos S., Wang T. T., Dahan R., Maamary J., Ravetch J. V., Signaling by antibodies: Recent progress. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 285–311 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bournazos S., DiLillo D. J., Ravetch J. V., The role of Fc-FcγR interactions in IgG-mediated microbial neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1361–1369 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bournazos S., Ravetch J. V., Fcγ receptor pathways during active and passive immunization. Immunol. Rev. 268, 88–103 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura Y., et al. , Early antibody therapy can induce long-lasting immunity to SHIV. Nature 543, 559–563 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura Y., Martin M. A., Of mice, macaques, and men: Broadly neutralizing antibody immunotherapy for HIV-1. Cell Host Microbe 22, 207–216 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu C. L., et al. , Enhanced clearance of HIV-1-infected cells by broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 in vivo. Science 352, 1001–1004 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiLillo D. J., Tan G. S., Palese P., Ravetch J. V., Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat. Med. 20, 143–151 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bournazos S., et al. , Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies require Fc effector functions for in vivo activity. Cell 158, 1243–1253 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halper-Stromberg A., et al. , Broadly neutralizing antibodies and viral inducers decrease rebound from HIV-1 latent reservoirs in humanized mice. Cell 158, 989–999 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiLillo D. J., Palese P., Wilson P. C., Ravetch J. V., Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 605–610 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettitt J., et al. , Therapeutic intervention of Ebola virus infection in rhesus macaques with the MB-003 monoclonal antibody cocktail. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 199ra113 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olinger G. G., Jr, et al. , Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18030–18035 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saphire E. O., et al. ; Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Immunotherapeutic Consortium , Systematic analysis of monoclonal antibodies against Ebola virus GP defines features that contribute to protection. Cell 174, 938–952.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunn B. M., et al. , A role for Fc function in therapeutic monoclonal antibody-mediated protection against Ebola virus. Cell Host Microbe 24, 221–233.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V., Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science 310, 1510–1512 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith P., DiLillo D. J., Bournazos S., Li F., Ravetch J. V., Mouse model recapitulating human Fcγ receptor structural and functional diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6181–6186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bournazos S., IgG Fc receptors: Evolutionary considerations. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 10.1007/82_2019_149 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson L. E., et al. , Early human B cell response to Ebola virus in four U.S. survivors of infection. J. Virol. 93, e01439-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bournazos S., Chow S. K., Abboud N., Casadevall A., Ravetch J. V., Human IgG Fc domain engineering enhances antitoxin neutralizing antibody activity. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 725–729 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiLillo D. J., Ravetch J. V., Differential Fc-receptor engagement drives an anti-tumor vaccinal effect. Cell 161, 1035–1045 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dyall J., et al. , Identification of combinations of approved drugs with synergistic activity against Ebola virus in cell cultures. J. Infect. Dis. 218 (suppl. 5), S672–S678 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrews C. D., et al. , In Vivo production of monoclonal antibodies by gene transfer via electroporation protects against lethal influenza and Ebola infections. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 7, 74–82 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cong Y., et al. , Evaluation of the activity of lamivudine and zidovudine against Ebola virus. PLoS One 11, e0166318 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holtsberg F. W., et al. , Pan-ebolavirus and pan-filovirus mouse monoclonal antibodies: Protection against Ebola and Sudan viruses. J. Virol. 90, 266–278 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keck Z. Y., et al. , Macaque monoclonal antibodies targeting novel conserved epitopes within filovirus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 90, 279–291 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansen L. M., et al. , A screen of approved drugs and molecular probes identifies therapeutics with anti-Ebola virus activity. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 290ra89 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Honnold S. P., et al. , Second generation inactivated eastern equine encephalitis virus vaccine candidates protect mice against a lethal aerosol challenge. PLoS One 9, e104708 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bray M., Davis K., Geisbert T., Schmaljohn C., Huggins J., A mouse model for evaluation of prophylaxis and therapy of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 179 (suppl. 1), S248–S258 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bournazos S., DiLillo D. J., Ravetch J. V., Humanized mice to study FcγR function. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 382, 237–248 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leon P. E., et al. , Optimal activation of Fc-mediated effector functions by influenza virus hemagglutinin antibodies requires two points of contact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E5944–E5951 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He W., et al. , Epitope specificity plays a critical role in regulating antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11931–11936 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He W., et al. , Alveolar macrophages are critical for broadly-reactive antibody-mediated protection against influenza A virus in mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 846 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oswald W. B., et al. , Neutralizing antibody fails to impact the course of Ebola virus infection in monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 3, e9 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton H. M., et al. , Fc-engineered anti-CD40 antibody enhances multiple effector functions and exhibits potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against hematologic malignancies. Blood 116, 3004–3012 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pietzsch J., et al. , A mouse model for HIV-1 entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15859–15864 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bournazos S., Gazumyan A., Seaman M. S., Nussenzweig M. C., Ravetch J. V., Bispecific anti-HIV-1 antibodies with enhanced breadth and potency. Cell 165, 1609–1620 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Research Council , Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, ed. 8, 2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.