Abstract

Background

The inclusion of patient preferences (PP) in the medical product life cycle is a topic of growing interest to stakeholders such as academics, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies, reimbursement agencies, industry, patients, physicians and regulators. This review aimed to understand the potential roles, reasons for using PP and the expectations, concerns and requirements associated with PP in industry processes, regulatory benefit-risk assessment (BRA) and marketing authorization (MA), and HTA and reimbursement decision-making.

Methods

A systematic review of peer-reviewed and grey literature published between January 2011 and March 2018 was performed. Consulted databases were EconLit, Embase, Guidelines International Network, PsycINFO and PubMed. A two-step strategy was used to select literature. Literature was analyzed using NVivo (QSR international).

Results

From 1015 initially identified documents, 72 were included. Most were written from an academic perspective (61%) and focused on PP in BRA/MA and/or HTA/reimbursement (73%). Using PP to improve understanding of patients’ valuations of treatment outcomes, patients’ benefit-risk trade-offs and preference heterogeneity were roles identified in all three decision-making contexts. Reasons for using PP relate to the unique insights and position of patients and the positive effect of including PP on the quality of the decision-making process. Concerns shared across decision-making contexts included methodological questions concerning the validity, reliability and cognitive burden of preference methods. In order to use PP, general, operational and quality requirements were identified, including recognition of the importance of PP and ensuring patient understanding in PP studies.

Conclusions

Despite the array of opportunities and added value of using PP throughout the different steps of the MPLC identified in this review, their inclusion in decision-making is hampered by methodological challenges and lack of specific guidance on how to tackle these challenges when undertaking PP studies. To support the development of such guidance, more best practice PP studies and PP studies investigating the methodological issues identified in this review are critically needed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12911-019-0875-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Patient preferences, Drug development, Drug evaluation, Decision-making, Stakeholders, Drug life cycle, Marketing authorization, Health technology assessment, Reimbursement

Background

Increasingly, the patient's perspective is considered essential on all levels of decision-making throughout the lifecycle of drugs and medical devices (i.e. the medical product life cycle (MPLC)) [1, 2]. This is demonstrated by a growth of literature on the roles of patients’ perspectives in drug and medical device development [3–5], regulatory benefit-risk assessment (BRA), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) [6–9] and clinical practice guideline development [10, 11]. The term ‘medical product’ will be used hereafter as an umbrella term for drugs (or human medicinal products) and medical devices as defined by the European Commission [12, 13] and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [14].

A particular area of interest is the measurement and use of patient preferences (PP) [15, 16]. Although no unique definition exists for PP across research fields and disciplines [17–20], the FDA refers to PP by defining patient preference information as “qualitative or quantitative assessments of the relative desirability or acceptability to patients of specified alternatives or choices among outcomes or other attributes1 that differ among alternative health interventions” [14]. PP can be investigated through qualitative and/or quantitative methods [19]. While qualitative methods (e.g. interviews) generate information about patient experiences and perspectives, quantitative methods (e.g. discrete choice experiments) collect numerical data [21].

Despite broad interest in the measurement and application of PP, a comprehensive overview of their specific roles and reasons to use them and the expectations, concerns and requirements regarding their use in the different decision-making contexts of the MPLC is lacking. This literature review attempts to address this gap by providing an overview of their potential roles, and reasons for using PP, as well as the expectations, requirements and concerns related to their use in the following decision-making contexts of the MPLC: i) industry processes, ii) regulatory BRA and marketing authorization (MA), and iii) HTA and reimbursement. Insights of this review show opportunities and challenges for the use of PP in decision-making by all stakeholders involved in these decision-making contexts, thereby paving the way for patient-centric decision-making throughout the MPLC.

Methods

Review context

This study was conducted as part of the Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle (PREFER) project, a five-year project that received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) 2 Joint Undertaking. PREFER aims to establish recommendations to guide industry, regulatory authorities and HTA/reimbursement bodies on how and when to include PP [22, 23]. While PP are gaining attention, their use in decision-making remains limited [2]. One of the first steps towards recommendations about PP was therefore to understand what hampers their current use (i.e. the challenges for their use) and what potential decisions and steps of the MPLC PP may inform (i.e. the opportunities). These questions formed the basis of the review questions.

Review questions and search strategy

The review was guided by the following review questions, pertaining both to the preference method itself and the application of PP to decision-making: i) what roles do PP have to play in the MPLC and what are reasons to use them? (desires), ii) what is expected to happen when PP are used in the MPLC? (expectations), iii) what concerns arise for the use of PP in the MPLC? (concerns) and iv) what is needed in order to use PP in the MPLC? (requirements). Search queries were developed based upon the review questions and consisted of Medical Subject Headings terms and free text words (Additional file 1). A preliminary scoping exercise with the initially developed search queries revealed that a large part of the literature retrieved focused on the use of PP in individual treatment decision-making and/or on the use of PP in the context of monitoring and biomarkers, both of which do not form the focus of this review. Therefore, a concept related to shared decision-making, monitoring and biomarkers was combined to the search query via ‘NOT’. A research librarian from Erasmus Rotterdam University conducted the search between January 2011 and March 2018 (so that included documents reflect contemporary issues related to PP) and in the following databases: EconLit, Embase, Guidelines International Network, PsycINFO and PubMed. Peer-reviewed publications were also identified through hand searching and snowballing. All PREFER collaborators were asked to share other relevant publicly available literature (grey literature, e.g. regulatory documents or HTA reports).

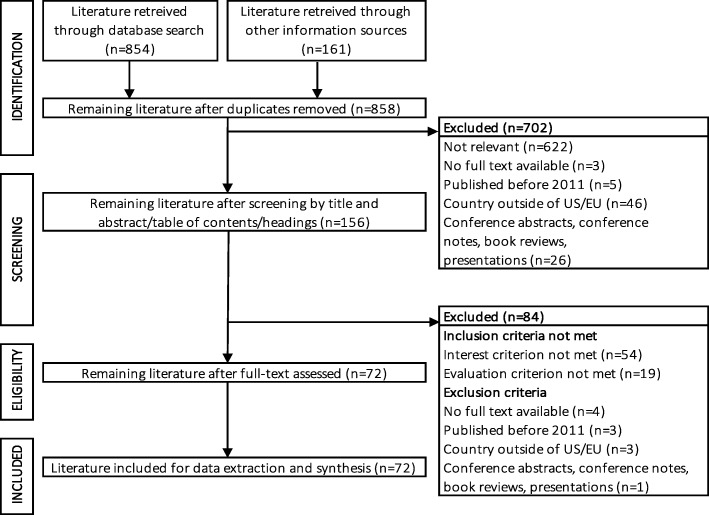

A two-step screening strategy was used (Fig. 1). First, title and abstract of peer-reviewed publications and the table of contents or headings of grey literature were screened for relevance to the review questions and exclusion criteria by three researchers (RJ, EvO, CW). Each document was independently screened by two researchers and disagreements were resolved by discussion. Second, full texts were screened to the in- and exclusion criteria by one researcher (RJ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the process of identifying and selecting documents for this review. Initially, 1015 documents were retrieved. From 858 non-duplicate documents, 702 were excluded, based on a screening of their title and abstract, table of contents or headings against their relevance to the review questions and exclusion criteria. An additional 84 documents were excluded after full text review against the in- and exclusion criteria, resulting in a total of 72 documents included for analysis

Selection criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: i) literature types regulatory documents, HTA reports, project reports and workshop reports (grey literature), (systematic) reviews, original research articles (e.g. published PP studies) and perspective articles (white literature), ii) perspective: literature describing the view of at least one of the following stakeholders was included: academics, HTA/reimbursement bodies, pharmaceutical or medical device industry, patients, caregivers and patient organizations, physicians and regulatory authorities, iii) interest: included literature had to describe the use of a preference method in the MPLC. Literature describing only the use of preference methods in the context of individual treatment decision-making or clinical practice guideline development were excluded, iv) evaluation: only literature describing at least one of the proposed review questions was found eligible. The following exclusion criteria were applied: i) non-English, ii) no full text available, iii) published before 2011 (so that included documents reflect contemporary issues related to PP), iv) non-EU or non-US (in view of the scope of this study) and v) conference abstracts, conference notes, book reviews and presentations.

Data analysis

The following steps were undertaken by one researcher (RJ) to analyze included literature: i) information on the literature type, stakeholder perspective and decision-making context was extracted (Table 1, Additional file 2), ii) a coding tree was developed to code the text (Additional file 3), iii) text was coded using the NVivo PRO 11 software (QSR international), iv) tables were developed based upon the structure of the coding tree using Microsoft Excel and these tables were subsequently used to describe literature per review question. Examples of PP studies included in the review were added to illustrate the findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included literature

| Characteristics of included documents (n = 72) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Literature type | ||

| Original research | 23 | 32 |

| Review | 17 | 24 |

| Perspective article | 11 | 15 |

| Project report | 7 | 10 |

| Systematic review | 4 | 6 |

| Workshop report | 3 | 4 |

| Regulatory document | 2 | 3 |

| HTA report | 2 | 3 |

| Other | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Main decision-making context described | ||

| BRA/MA | 25 | 35 |

| HTA/reimbursement | 15 | 21 |

| BRA/MA + HTA/reimbursement | 12 | 17 |

| IPDM | 5 | 7 |

| ITD + BRA/MA | 3 | 4 |

| IPDM + HTA/reimbursement + BRA/MA | 3 | 4 |

| IPDM + BRA/MA | 4 | 6 |

| ITD + BRA/MA + HTA/reimbursement | 2 | 3 |

| BRA/MA + HTA/reimbursement + ITD + CPG | 1 | 1 |

| HTA/reimbursement + IPDM | 1 | 1 |

| HTA/reimbursement + CPG | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Stakeholder perspective | ||

| Academic | 44 | 61 |

| Regulatory authority | 8 | 11 |

| Industry/CRO | 7 | 10 |

| HTA body | 3 | 4 |

| Patient organization | 3 | 4 |

| Other | 7 | 10 |

Number and percentage of included documents per literature type, main decision-making context described and stakeholder perspective (bold font). Each document was assigned to a stakeholder perspective: for primary research articles, (systematic) reviews and perspective articles, the affiliation cited of the first author was used to assign a stakeholder perspective. For regulatory documents, the regulatory authority perspective was assigned. HTA reports were assigned to the HTA body perspective. For project reports, since those are written from multiple stakeholder perspectives, they could not be assigned to a specific stakeholder perspective. HTA Health Technology Assessment, BRA benefit-risk assessment, MA marketing authorization, IPDM industry processes and decision-making, CPG clinical practice guideline development, ITD individual treatment decision-making, CRO contract research organization

Results

The initial search identified 1015 documents. Seventy-two documents were included (Fig. 1, Additional file 2). Most were: i) original research (32%) or reviews (24%), ii) focused on PP in BRA/MA decision-making (35%), HTA/reimbursement (21%) or both (17%) and iii) written from an academic perspective (61%) (Table 1).

1. What roles do PP have to play in the MPLC and what are reasons to use them? (desires)

The potential roles of PP in the MPLC can be categorized into industry processes, regulatory BRA/MA and HTA and reimbursement (Table 2). Reasons for using PP include reasons related to the unique insights and position of patients and reasons related to the positive effect of including PP on the quality of the decision-making process (Table 3). Following the rationale that knowing how patients value treatment benefits and risks is essential because only patients know what it is like to live with their disease, and the idea that patients and regulators may value benefits and risks differently (Table 3), Ho et al. conducted a first PP study to inform regulatory BRA of medical devices for obese patients [45]. The authors incorporated the attribute weights resulting from the study in a tool that informs BRA for the approval of new medical devices; FDA reviewers could then compare efficacy results from clinical trials with the minimum benefit (i.e. weight loss) required as indicated by the tool [45]. Although the study was specifically designed to inform regulatory MA of new devices, they state that their results could also guide clinical trial design and post-approval decisions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Potential roles of PP in the MPLC

| 1. Potential roles of PP in industry processes | |

| 1.1 Early development | |

| • Informing ‘go/no-go’ decisions (e.g. internal prioritization portfolio decisions) [24] | |

| • Informing resource allocation decisions among multiple diseases [24] | |

| • Defining areas of unmet medical need [14, 16, 24] | |

| • Influencing which medical product will be developed [24] | |

| • Informing the design of a target product profile [14, 19, 27–29] | |

| 1.2 Clinical trial design | |

| • Quantifying how clinical outcomes, benefits and risks are perceived [14, 19, 30–34] | |

| • Indicating which clinical endpoints are of highest importance to patients [14, 31–33, 35] | |

| • Indicating which endpoints should (not) be considered [31] | |

| • Informing enrollment criteria and sample populations [19, 31, 33] | |

| • Informing clinical trial sample size [27] | |

| • Calculating acceptable levels of uncertainty (significance level and power) [36] | |

| • Analyzing clinical trials [14, 19] | |

| • Defining subgroups with different benefit-risk trade-offs [19, 24, 37] | |

| 1.3 Product labelling [14, 19, 37] | |

| 1.4 Post-marketing | |

| • Subgroup PP information for suggesting new markets for present indications [37] | |

| • Subgroup PP information for pointing to specific treatment opportunities [37] | |

| • Informing new innovations [14] | |

| • Redesigning and improving existing products [14, 19] | |

| • Informing expanded indications or populations [14] | |

| • Informing risk assessments underlying product recalls [19] | |

| • Optimizing promotional materials [19] | |

| 1.5 Pharmacovigilance activities [19, 38, 39] | |

| • Planning and evaluating BRAs and risk management [39] | |

| 2. Potential roles of PP in BRA/MA | |

| • Highlighting patients’ needs for treatment [25, 26] | |

| • Highlighting differences in views between patients and decision-makers [19, 24, 40–42] | |

| • Highlighting situations with need for transparent communication about decision [42] | |

| • Providing quantitative measures of how patients view their choices [24] | |

| • Weighing (clinical) outcomes and attributes [14, 19, 25, 30, 34, 37, 38, 40, 43–48] | |

| • Identifying most relevant outcomes to patients [14, 19, 24, 26, 37, 48, 49] | |

| • Identifying outcomes with less perceived meaning [50] | |

| • Providing insights into patient perspectives on other aspects of treatment (e.g. dosing) [34] | |

| • Indicating patient benefit-risk trade-offs [18, 19, 24, 26, 34, 37, 38, 45, 47, 49, 51] | |

| • Indicating whether patients are likely to use therapy if approved [41] | |

| • Indicating how patients compare benefits and risks between treatment options [24] | |

| • Indicating how patients weigh benefits and risks as the disease progresses [24] | |

| • Enabling quantitative benefit-risk modelling in complex cases [19, 36, 37] | |

| • Providing information on uncertainty tolerance [24, 49] | |

| • Understanding patient heterogeneity [14, 19, 24, 37, 40, 42, 45, 52, 53] | |

| • Tailoring MA decision based on subgroups with homogeneous preferences [14, 37, 42, 45] | |

| 3. Potential roles of PP in HTA/reimbursement | |

| • Indicating patients’ preferred treatments/technologies/healthcare services [54–57] | |

| • Indicating patients’ preferred health states (quality of life) [52] | |

| • Indicating patients’ preferred mode of administration [52, 56] | |

| • Indicating patients’ preferred clinical outcomes (including benefits/risks) [30, 50, 52] | |

| • Highlighting potential differences in views between patients and decision-makers [40] | |

| • Selecting, prioritizing or weighing endpoints and criteria [15, 18, 30, 44, 47, 50, 58] | |

| • Highlighting the value of a treatment when the QALY is considered too narrow [59] | |

| • Examining relative benefit-risk trade-offs [44, 54] | |

| • Estimating willingness to pay or willingness to accept compensation [54] | |

| • Predicting uptake rates [54] | |

| • Indicating the general acceptability of a technology to patients [19, 56, 60] | |

| • Providing input for economic evaluations (e.g. cost-utility analyses) [30, 47, 50, 53, 54, 61] | |

| • Contributing to prioritization of topics for HTA [30] | |

| • Identifying heterogeneity and segments of the patient population [52, 53] | |

| • Tailoring reimbursement decisions based upon preference heterogeneity [52] |

Potential roles of PP in the MPLC grouped per decision-making context (bold and underlined font). PP patient preferences, HTA Health Technology Assessment, BRA benefit-risk assessment, MA marketing authorization, MPLC medical product life cycle, QALY Quality Adjusted Life Years

Table 3.

Reasons for using PP in the MPLC

| 1. Reasons related to the unique insights of patients | |

| • Patients have experiential knowledge of disease and treatment [16, 24, 38, 43, 54, 60, 62] | |

| • Decision-makers and patients might have differing preferences [19, 40, 44, 58, 63] | |

| • It challenges the opinions on the importance of endpoints [30, 52] | |

| 2. Reasons related to the unique position of patients | |

| • Patients are the ultimate beneficiaries/end-consumers of healthcare [25, 31] | |

| • Patients are directly affected by the decision [38, 43, 53, 54, 60, 62] | |

| • Patients’ lives are affected by whether their concerns were considered [64] | |

| • Patient benefit is an objective of providing healthcare services [64] | |

| 3. Reasons related to the positive effect on quality of the decision-making process | |

| • It enables judging the consistency of decisions with patient values [64] | |

| • It enables a more patient-centered decision-making [19, 36, 40, 52, 53, 58] | |

| • It allows evidence-based consideration of patient perspectives [24, 36, 38, 40, 43, 45, 52, 58, 64, 65] | |

| • It ensures patient needs are better met [25, 53, 64] | |

| • Measurements of clinical effects usually do not sufficiently capture PP [38, 64] | |

| • It facilitates integration of patient concerns into decision-making [66] | |

| • It increases the effectiveness of patient involvement strategies [62] | |

| • It solves the issue of which patients to involve directly in decision-making [38] | |

| • It may be more representative than direct patient involvement [24, 25, 38, 40, 43, 58, 60, 62, 67, 68] | |

| • It is required for the implementation of evidence-based medicine [64] |

Reasons for using PP grouped into reasons related to the unique insights and position of patients and reasons related to the positive effect of including PP on decision-making (bold and underlined font). PP patient preferences, MPLC medical product life cycle

2. What is expected to happen when PP are used in the MPLC? (expectations)

A range of expectations were identified in the literature review. Using PP for defining treatment attributes is expected to deliver improved health outcomes for patients [14]. PP for the selection of clinical endpoint selection is expected to: i) increase the willingness of participants to enroll in and complete a clinical trial, thereby accelerating clinical development [14, 32], ii) provide more meaningful results to future patients and iii) improve the adherence of this population with the medical product once being marketed [33, 69]. Chow et al. [33] quantified the importance of clinical trial endpoints used in cardiovascular clinical trials according to patients. They expect that, should these endpoints be selected in cardiovascular clinical trials, results from such trials would be perceived with greater validity by those reviewing the trial data [33].

Use of PP in BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement is expected to result in: i) a higher quality decision by better alignment between the decision and patients’ values and unmet needs [25, 38, 45, 64], ii) greater legitimacy or accountability of the decision as result of taking into account clinical, social and ethical aspects of medical products that may not be considered by a professional panel of decision-makers [25], iii) an increased understanding and acceptance of the decision by the public and stakeholders because preferences of those affected by the decision were considered [25, 38, 63, 70], iv) more public trust in the decision-making process [71], and v) an increased collection of PP [64]. Finally, incorporating PP information on subgroups for whom a specific treatment will produce more benefit could increase the effectiveness and efficiency of medical products [65].

3. What concerns arise for the use of PP in the MPLC? (concerns)

Concerns related to using PP in the MPLC can be categorized into three types: i) general concerns (broad issues applicable to all decision-making contexts of the MPLC, e.g., lack of familiarity with preference methods among stakeholders), ii) methodological concerns (those related to measuring PP, applicable to all decision-making contexts of the MPLC, e.g., low reliability of PP studies) and iii) concerns specifically related to BRA/MA and/or HTA/reimbursement (issues related to PP specifically for a certain decision-making context, e.g., lack of clarity about how to align PP with the Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) measure in HTA/reimbursement) (Table 4).The German HTA Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) piloted the preference method Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) for the identification, weighting and prioritization of outcomes for the treatment of depression [74]. While concluding that the attribute weights resulting from their PP study could both guide industry decisions on clinical trial endpoint selection and HTA processes when prioritizing outcomes, they report methodological concerns such as correlating attributes and question the representativeness of the study population and transferability of the results to the entire patient population [74] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Concerns related to PP in MPLC

| 1. General concerns related to PP in industry, BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement | |

| • Lack of clarity and (regulatory) guidance about: | |

| ○ Definition of PP, hampering communication between stakeholders [1, 62] | |

| ○ Under what conditions to measure/use PP [1, 19] | |

| ○ For which medical product to collect PP [19, 27, 37] | |

| ○ When to conduct a PP study: before, during or after clinical development [19, 27, 37] | |

| ○ What preference method to use [19, 40, 72] | |

| ○ Which attributes to select in a PP study [19, 30, 50] | |

| ○ How to assure validity in a PP study [19, 38] | |

| ○ Whose preferences to measure (e.g. required disease experience) [19, 27, 44, 54, 73] | |

| ○ How to deal with preference heterogeneity [54] | |

| ○ Which stakeholder should collect PP [38] | |

| ○ Who is responsible for PP results and potential biases in results [38] | |

| •Lack of familiarity among stakeholders with preference methods [16, 19, 24, 34] | |

| •Lack of patients’ knowledge and capability of expressing preferences [62] | |

| 2. Methodological concerns related to PP in industry, BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement | |

| • Low validity and reliability of preference methods [19, 25, 43] | |

| • Overlap in interpretation of attributes and interacting/overlapping attributes [30, 35, 50] | |

| • Tension between methodologically strong methods and their cognitive burden [18, 48] | |

| • Risk of neglecting of patient heterogeneity in PP studies [40, 52, 58] | |

| • Elicited PP are constructed and shaped by how information is presented [62] | |

| • Elicited PP are influenced by external factors [62] | |

| • Heuristics, inert or flexible preferences and measurement errors [19, 24, 27, 38, 48] | |

| • Challenge of communicating the quantitative health information to patients [14] | |

| • Innumeracy of the participants [38, 43] | |

| • Respondents not taking time to complete the survey of the PP study [35] | |

| • Lack of understanding among respondents [35] | |

| • Question framing in preference surveys [55] | |

| • Difficulty of balancing between understandability and accuracy of questions [55] | |

| • Ensuring representativeness of the sample [27, 50, 55] | |

| 3. Concerns specifically related to PP in BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement | |

| • Lack of clarity about: | |

| ○ How PP will be used and reviewed by decision-makers [19, 24, 38] | |

| ○ How to submit PP for BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement [24, 53] | |

| ○ Standards for measuring PP for informing BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement [24, 72] | |

| 4. Concerns specifically related to PP in HTA/reimbursement | |

| • Lack of clarity about: | |

| ○ Measuring patient preferences versus public preferences [54, 59, 62] | |

| ○ Measuring PP for health aspects or also for non-health aspects [1] | |

| ○ Incorporating PP in economic evaluations or not [1] | |

| ○ Using quantitative and/or qualitative PP in reimbursement decisions [1, 59] | |

| ○ Where and how to incorporate PP in current procedures [1, 18, 62] | |

| ○ How to align PP with the traditional QALY calculation [62] | |

| ○ How to conduct a systematic review on PP studies for informing HTA [60] | |

| ○ What weight PP should receive versus other decision criteria [1, 62] | |

| • Current recommendation of HTA agencies (e.g. the UK, the Netherlands) to use generic measures, whereas PP elicited via PP studies are often condition-specific [59] | |

| • Current use of cost-utility analysis, which does not require quantitative PP beyond health state utilities [59] | |

| • Low generalizability of PP study results when characteristics of healthcare system are being valued as these characteristics are often system-, country- or culture-specific [55, 62] | |

| • Time, funding and staff required for incorporating PP in HTA/reimbursement [1] |

Concerns related to using PP in the MPLC grouped according to their nature and the decision-making context they apply to: general concerns, methodological concerns and concerns specifically related to BRA/MA and/or HTA/reimbursement (bold and underlined font). PP patient preferences, HTA Health Technology Assessment, BRA benefit-risk assessment, MA marketing authorization, MPLC medical product life cycle, QALY Quality Adjusted Life Years

4. What is needed in order to use PP in the MPLC? (requirements)

Requirements related to using PP across the different decision-making contexts of the MPLC can be categorized into: i) general requirements (broad aspects that are needed to measure and use PP, e.g. guidance on PP studies), ii) operational requirements (non-methodological prerequisites related to the execution of PP studies, e.g. regarding the timing of a PP study) and iii) quality requirements (prerequisites that increase the quality of the PP study, e.g. study objectivity) (Table 5). Based on their experience from quantifying benefit-risk preferences among rare disease patients and caregivers, Morel et al. [51] conclude that while researchers of novel medical products for rare diseases should be encouraged to invest in use of preference methods, specific regulatory guidance is needed to acknowledge the importance of PP and to state when in the MPLC preference methods should be used (Table 5).

Table 5.

Requirements related to PP in the MPLC

| 1. General requirements | |

| • Recognition of the value of PP among stakeholders [24, 25, 39, 51, 59, 64] | |

| • Consensus on the role of PP in decision-making [1, 62] | |

| • More familiarity among stakeholders with PP studies [19, 34, 48, 66, 70, 72] | |

| • More educated researchers in preference research [53] | |

| • Resources to evaluate PP [1, 48] | |

| • Taxonomic work for PP research [1, 60] | |

| • Guidance on: | |

| ○ When during development to measure PP [1, 34, 51] | |

| ○ Which preference method to use in which circumstance [1, 40, 44, 56, 72] | |

| ○ Whose preferences to measure (e.g. required disease experience) [1, 19, 44] | |

| ○ Sample size [37] | |

| ○ Good research practice and quality criteria for PP studies [1, 19, 38, 43, 44, 62] | |

| ○ How to ensure validity of a PP study [75] | |

| ○ How to report about PP studies [44] | |

| • Further research to: | |

| ○ Validate and test preference methods [37, 44, 46, 66, 76] | |

| ○ Identify methods for integrating clinical evidence in PP study analysis [50, 56] | |

| ○ Investigate methodological issues (e.g. hindsight bias) [62] | |

| ○ Compare the performance of different methods in a given situation [37] | |

| ○ Determine impact of changing list of attributes with any given method [37] | |

| ○ Explore statistical methods to detect preference heterogeneity [77] | |

| ○ Guide the development of newer methods for eliciting PP [76] | |

| ○ Assess comprehension differences by participants between methods [76] | |

| ○ Assess impact of the level of previous education on PP [33] | |

| ○ Quantify the effect of the attribute descriptions on elicited PP [78] | |

| 2. Operational requirements | |

| • Requirements related to timing of PP study: | |

| ○ Decision depends on level of information of the treatments’ key risks [19] | |

| ○ Timing needs to be decided by sponsor [19] | |

| ○ During marketing phase to assess long-term side effects and burden [1] | |

| • Requirements related to dealing with PP study results: | |

| ○ Stakeholders should be prepared for disappointing PP study results [24] | |

| ○ PP study results should be provided to patient community and public [24] | |

| ○ Presentation of PP study results should be tailored to the audience [79] | |

| ○ PP study results should be described transparently [56, 75] | |

| 3. Quality requirements | |

| • General requirements regarding design, set-up and conduct of PP studies: | |

| ○ Selected research question should be answerable with PP study [75] | |

| ○ Study objectivity throughout PP study [24] | |

| ○ Independent design as design can influence analysis outcomes [25] | |

| ○ Extensive and forward planning [19, 27, 48] | |

| ○ Determination of objectives and attributes before design [24] | |

| ○ Design based on prior literature and preference information [19] | |

| ○ Clear definition of the patient sample and characteristics [19, 24, 49] | |

| ○ Training partners on methodology, objectives and expectations of study [79] | |

| ○ Good communication and documentation of changes to study plans [79] | |

| ○ Methodological expertise when designing and executing a PP study [24, 70] | |

| ○ Multi-stakeholder partnerships (patients, academics, industry) [24, 37, 79] | |

| ○ Interaction between decision-makers and industry in design [14, 19, 24] | |

| ○ Involvement of patients, caregivers and patient organizations [24, 42, 49, 51] | |

| ○ Application of ‘good science’ principles [1, 19, 24, 51] | |

| ○ Consideration of patient heterogeneity and cognitive burden [14, 40, 58, 75] | |

| ○ Consideration of internal and external validity [75] | |

| ○ Administration of survey by trained researchers [14] | |

| ○ Provision of tutorial for participants if self-administered survey is used [14] | |

| ○ Training of participants in elicitation tasks [40] | |

| ○ Ensuring participants’ understanding of aim and how results will be used [40] | |

| ○ Consideration of low level of health numeracy in general population [43] | |

| • Sample requirements: | |

| ○ Sample should be heterogeneous (large samples, setting quotas) [19, 49, 75] | |

| ○ Sample should be representative of population of interest [14, 19] | |

| ○ If not possible to elicit from patients, include proxies [19, 34] | |

| ○ Sample ideally is clinical trial population [71] | |

| ○ Sample ideally is broader population than clinical trial population [41] | |

| ○ Patient should be the focus, not health care professional [14] | |

| ○ Sample should be representative of affected patients [56] | |

| ○ Sample should be representative of target population [75] | |

| ○ Sample that can yield reliable results should be drawn [24] | |

| ○ PP should come from the same population as data of effectiveness [1] | |

| ○ Both patients in remission as well as patients in recovery should be included [50] | |

| ○ Sampling should consider sociodemographic and disease characteristics [50, 61] | |

| • Sample size requirements: | |

| ○ Adequate size so that results are generalizable to population of interest [14] | |

| ○ Sufficient size to generate acceptably robust results [24] | |

| ○ If subgroups: sufficient number in each subgroup [14] | |

| • PP results requirements: | |

| ○ Type of PP (qualitative vs quantitative) depends on stage and decision-making context of MPLC [1, 14, 16, 19, 60] | |

| ○ Type of PP should be determined by research question [19] | |

| ○ Clinical data should be collected and used to augment PP data [42, 43] | |

| ○ Patient’s willingness and unwillingness to accept risks should be measured [14] | |

| • Preference method requirements: | |

| ○ Method should be selected based on factors [1, 19, 40, 44, 76, 80] | |

| ○ Method should adhere to utility theory [18, 76] | |

| ○ Method should account for patient-relevant attributes/outcome measures [18] | |

| ○ Methods should be easy and simple for patients to understand [18] | |

| • Requirements regarding attribute selection: | |

| ○ Research question should guide attribute and level selection [75] | |

| ○ Attributes should be broader than clinical attributes to elicit meaningful trade-offs [41] | |

| ○ Attributes should be patient-centered to investigate meaningful attributes [49] | |

| ○ Attributes should come from existing clinical trials [50, 81] | |

| ○ Selection by literature, qualitative study, asking group of medical experts or decision-makers [19] | |

| ○ Patient representatives, patients and experts should inform selection [50, 62] | |

| ○ Attributes should not overlap [30, 35, 50] | |

| • Requirements regarding survey instrument: | |

| ○ Survey should be developed with input from multiple stakeholders [24] | |

| ○ Survey should be piloted [24, 40] | |

| ○ Survey should include screening questions, informed consent provisions, background information, training and definitions, testing, survey questions, follow-up survey questions [24] | |

| ○ Benefit descriptions and effectiveness measures should be carefully defined [78] | |

| ○ Patients should understand objective of the elicitation tasks and how data will be used [40] | |

| ○ Questions have to be asked in an open and understandable way [18, 56, 75] | |

| ○ For choice-based preference measures, options should: | |

| ■ Be clearly described [56] | |

| ■ Have realistic advantages and disadvantages [56] | |

| ■ Be communicated to patients together with their characteristics [80] | |

| • Requirements regarding the analysis: | |

| ○ Interpretation of results should consider the mode of sampling [68] | |

| ○ Interpretation of study results should be validated with patients [40] | |

| ○ Results should be considered with preferences from other stakeholders (clinicians, decision-makers) [68] | |

| ○ Appropriate stakeholders should interpret analysis [79] | |

| ○ Sources of uncertainty should be reported through confidence interval and/or standard error [14] | |

| ○ Written agreements about intellectual property and data use are needed [24] |

Requirements related to using PP in the MPLC grouped according to their type and nature: general requirements, operational requirements and quality requirements (bold and underlined font). PP patient preferences, MPLC medical product life cycle

Discussion

Using a systematic approach, this review identified the potential roles and reasons to use PP (desires), as well as the expectations, concerns and requirements regarding their use across industry processes, BRA/MA, and HTA/reimbursement decision-making.

The three potential roles that were identified in all three decision-making contexts involved the use of PP to increase understanding of: i) how patients value (clinical) outcomes of a medical product, ii) how patients make the trade-off between benefits and risks and iii) how preferences may differ across patient subgroups (preference heterogeneity). This finding raises the question of whether a single PP study with the primary objectives of investigating these three issues could inform all three decision-making contexts and address the needs respectively, of industry, HTA/reimbursement and regulatory BRA/MA stakeholders. One could for example imagine a PP study consisting of: i) a qualitative phase, where patients are asked openly about what their needs are regarding treatment for their disease and what treatment attributes they find important, and ii) a quantitative phase, where patients are asked to choose between hypothetical treatment options that differ in how they perform on these treatment attributes. Both the results from the qualitative phase as well as the selected attributes and attribute weights derived from the quantitative phase could assist industry in: i) developing a medical product that targeted patient needs and the attributes that patients found most important and ii) subsequently selecting those clinical trial endpoints based upon the attributes patients indicated as most relevant. The selected attributes and the attribute values from the quantitative phase could also be used by regulators and HTA/reimbursement decision-makers to assess the clinical relevance of the outcomes of a medical product being evaluated for MA and reimbursement for the disease of the included patients in the PP study. Furthermore, the attribute values could be used to calculate the minimum required benefit (the minimum benefit respondents expect in order to tolerate a specific level of risk) and the maximum acceptable risk (the maximum risk respondents are willing to tolerate for a given benefit). This minimum required benefit could be used as a reference by regulatory and HTA/reimbursement decision-makers, to evaluate whether or not the clinical benefit of the medical product, as demonstrated in clinical trials exceeds this value, i.e. whether patients would accept the risks of the product under evaluation in return for its benefits. If these calculations indicated that a subgroup of patients accepted the risks in exchange for the benefit, this could inform regulators and HTA/reimbursement decision-makers on the marketing authorization or reimbursement for that subset of patients respectively. These preferred outcomes could also be incorporated in a novel patient relevant outcome (PRO) instrument as, for example, explained by Evers et al. [32], that could be used during clinical trials to evaluate how the medical product in clinical development performed on these PROs. Results from such a hypothetical clinical trial could then inform: i) regulators and HTA decision-makers regarding the performance of that medical product in terms of those PROs as observed during clinical development and ii) the developer of that medical product on how to redesign and improve the medical product in subsequent development. After the MA and reimbursement decision, the PRO instrument could be used to assess how the medical product performs on these PROs outside the clinical trial environment. This information could then inform industry on product redesign and regulatory and HTA/reimbursement stakeholders on continuation of MA and reimbursement. Finally, if these PRO measurements indicate that the medical product only performs well for a subset of patients outside the clinical trial environment this could inform continuation of MA and reimbursement for that subset of patients only.

Despite the array of potential opportunities for the use of PP in the MPLC listed in Table 2, there are few published examples of the actual use of PP study results in industry, regulatory and HTA decisions [45, 82]. As highlighted in Tables 4 and 5, a number of concerns and gaps need to be addressed in order to advance the measurement and use of PP in these decisions. More specifically, efforts need to focus on providing and encouraging: i) recognition of the importance of including PP in industry, regulatory and HTA decisions, ii) guidance on when and how to measure PP aiming to inform these stakeholder decisions and iii) increased familiarity with performing and evaluating PP studies. To promote the development of guidance, more best practice PP studies and more PP studies investigating the methodological concerns this review identified are needed on such questions as: i) how to select, apply and validate different preference methods, ii) how to choose a representative sample in order to satisfy the needs of different stakeholders and iii) how to increase understanding of the reliability and cognitive burden of different preference methods.

Although efforts to address methodological issues are crucial, they are not sufficient alone. Efforts are also needed to address how results from a PP study could be incorporated and aligned with current decision-making processes. More clarity on how results from PP studies would be used in regulatory and HTA decisions together with guidance on how such studies should be conducted could motivate stakeholders to conduct and submit a PP study (Table 5). Table 5 highlights additional concerns regarding the use of PP in HTA/reimbursement. Among the multiple ways in which PP could inform HTA/reimbursement (Table 2), the potential role of PP to inform QALY calculations in countries with publicly funded healthcare is under ongoing debate. As in these countries, HTA guides the allocation of public resources (including but not limited to patients only), it is unclear whether public versus patient preferences should be used. Incorporation of PP in HTA/reimbursement bodies of such countries would therefore not only require solving methodological questions, but also structural and political discussions on the current HTA process in those countries.

This review identified numerous operational and quality requirements involved in performing and evaluating PP studies (Table 5), including: i) ensuring a transparent description of PP study and results when communicating about the study, ii) applying the principles of ‘good science’ when conducting a PP study, iii) paying attention to the heterogeneity of PP and cognitive challenges of preference methods, iv) ensuring patient understanding of the questions asked in the PP study and v) ensuring a representative and diverse sample.

Remarkably, only 18% of the included documents focused on the use of PP in industry processes, leading to sparse results on the use PP in industry processes. As a result, further research is warranted regarding the use of PP for industry purposes, e.g. by consulting sources other than the peer-reviewed literature, including those sources that use qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups. It was beyond the scope and aim of this review to: i) explain reasons why certain concerns or requirements exist and ii) grade the results (e.g. the identified concerns and requirements) into a hierarchy indicating their importance. Therefore, research aiming to address these issues could complement the current review, e.g. by using qualitative methods to explain the reasoning behind certain issues or differences or by using quantitative methods aimed at ranking and prioritizing the identified requirements and concerns. No literature was found that described the patient’s, caregiver’s, reimbursement agency’s or (practicing) physician’s perspective, which may have led toward a more methodological and scientific result. Therefore, research aiming to assess the perspectives of these different stakeholder groups on the measurement and the use of PP in the MPLC would complement the current review.

The main strengths of this review are its comprehensiveness and novelty in using a systematic approach to search and identify literature relevant to this topic; to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review that provides an overview of the specific roles and the expectations, concerns and requirements associated with using PP in different decision-making contexts across the MPLC and for different stakeholders, including industry, BRA/MA, and HTA/reimbursement. This review also has limitations. The selection criteria led to the exclusion of: i) literature focused only on PP within individual treatment decision-making, ii) non-English literature, iii) literature from outside the US/EU and iv) literature that did not explicitly mention the use of preference methods. These criteria might have resulted in the exclusion of literature dealing with issues relevant to this review. Further, the broad time span of included literature may be viewed as a limitation since the described concerns and requirements mentioned in earlier published work might at this time already be (partially) resolved and therefore this information might not be as accurate as more recently published studies. During coding, it was sometimes unclear to what specific decision-making context a particular piece of text pertained or whether a particular piece of text needed to be coded as a: i) desire or expectation or ii) concern or a need. This difficulty resulted in this text being coded into multiple domains, which in turn led to some of the results being repeated.

Conclusions

This review highlights the numerous opportunities for using PP in industry, BRA/MA and HTA/reimbursement decisions, from early development decisions through pharmacovigilance activities and post-marketing decisions. However, exploiting the full potential of PP in these decision-making contexts is currently hampered by remaining methodological challenges and lack of specific (regulatory) guidance on how to address these challenges when designing and performing PP studies aiming to inform decisions. To support the development of such guidance, more best practice PP studies and PP studies investigating these methodological issues are critically needed.

Additional files

Search queries (DOCX 98 kb)

Included literature (DOCX 193 kb)

Coding tree (DOCX 96 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone within and outside of the PREFER consortium for contributing to this review; thank you to those that sent documents for inclusion in the review and to those that reviewed the protocol and search queries. Thank you to Thomas Vandendriessche from KU Leuven for helping defining the review questions and search query. Thank you to Judith Gulpers from Erasmus University Rotterdam for helping refining and running the search queries. A special thank you to Professor Karin Hannes from the KU Leuven for sharing her methodological expertise regarding systematic reviews and for providing input on the structure of this review. Thank you to the reviewers for their time and valuable suggestions.

Disclaimer

This text and its contents reflects the PREFER project’s view and not the view of IMI, the European Union or EFPIA.

Abbreviations

- AHP

Analytical Hierarchy Process

- BRA

Benefit-risk assessment

- CPG

Clinical practice guideline development

- CRO

Contract research organization

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- HTA

Health Technology Assessment

- IMI

Innovative Medicines Initiative

- IPDM

Industry processes and decision-making

- IQWiG

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care

- ITD

Individual treatment decision-making

- MA

Marketing authorization

- MPLC

Medical product life cycle

- PP

Patient preferences

- PREFER

Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle

- PRO

Patient relevant outcome

- QALY

Quality Adjusted Life Years

Authors’ contributions

RJ, IH, EvO, CW, SH, JK, JJ, AC, SS, HS, MS, BL, IC, EdBG and JV contributed to the protocol design of this study and/or the acquisition of the data. RJ, EvO and CW developed the search query. RJ, EvO and CW selected the documents. RJ wrote the manuscript and IH and JV were involved in the further refinement of the main text, figure and tables. RJ, IH, EvO, CW, SH, JK, JJ, AC, SS, HS, MS, BL, IC, EdBG and JV reviewed the study findings, read and approved the final version before submission.

Funding

This study is part of the PREFER project. PREFER is a five-year project that has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No 115966. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA. The Innovative Medicines Initiative had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Dr. Veldwijk, Dr. de Bekker-Grob, Dr. Simoens, Dr. Stevens, Dr. Ciaglia have nothing to disclose. Ms. Janssens, Dr. Huys, Ms. van Overbeeke, Ms. Whichello and Dr. Cleemput report grants from the EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative [2] Joint Undertaking, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Juhaeri is an employee of Sanofi, a bio-pharmaceutical company. He owns Sanofi stock option and restricted shares and he has investments that may include stocks of other bio-pharmaceutical companies at certain points in time. Dr. Harding reports other from Takeda International - UK Branch, outside the submitted work. Dr. Küblers’ work was funded by CSL Behring. Dr. Smith is an employee of Amgen, Inc. and owns stock in Amgen, AbbVie, and Abbott. Dr. Levitan is an employee of Janssen Research and Development, LLC. Dr. Levitan is a stockholder in Johnson & Johnson, Baxter International, Inc., Pharmaceutical Holders Trust, and Zimmer Holdings, Inc. Dr. Levitan also owns stock in a variety of companies that at times include other pharmaceutical and health care-related companies.

Footnotes

Synonyms for attributes in literature are “characteristics”, “features”, “objects” or “criteria”.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rosanne Janssens and Isabelle Huys are joint first author.

Contributor Information

Rosanne Janssens, Email: rosanne.janssens@kuleuven.be.

Isabelle Huys, Email: isabelle.huys@kuleuven.be.

Eline van Overbeeke, Email: eline.vanoverbeeke@kuleuven.be.

Chiara Whichello, Email: whichello@eshpm.eur.nl.

Sarah Harding, Email: sarah.harding@takeda.com.

Jürgen Kübler, Email: juergen.kuebler@qscicon.com.

Juhaeri Juhaeri, Email: juhaeri.Juhaeri@sanofi.com.

Antonio Ciaglia, Email: antonio.ciaglia@gmail.com.

Steven Simoens, Email: steven.simoens@kuleuven.be.

Hilde Stevens, Email: hstevens@i3health.eu.

Meredith Smith, Email: mersmith@amgen.com.

Bennett Levitan, Email: blevitan@its.jnj.com.

Irina Cleemput, Email: irina.Cleemput@kce.fgov.be.

Esther de Bekker-Grob, Email: debekker-grob@eshpm.eur.nl.

Jorien Veldwijk, Email: veldwijk@eshpm.eur.nl.

References

- 1.Utens C, Dirksen C, van der Weijden T, Joore MA. How to integrate research evidence on patient preferences in pharmaceutical coverage decisions and clinical practice guidelines: a qualitative study among Dutch stakeholders. Health Policy. 2015;120(1):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Overbeeke E, Whichello C, Janssens R, Veldwijk J, Cleemput I, Simoens S, et al. Factors and situations influencing the value of patient preference studies along the medical product lifecycle: a literature review. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons S, Starling B, Mullan-Jensen C, Tham SG, Warner K, Wever K. What do pharmaceutical industry professionals in Europe believe about involving patients and the public in research and development of medicines? a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008928. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe MM, Blaser DA, Cone L, Arcona S, Ko J, Sasane R, et al. Increasing patient involvement in drug development. Value Health. 2016;19(6):869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crocker JC, Boylan AM, Bostock J, Locock L. Is it worth it? Patient and public views on the impact of their involvement in health research and its assessment: a UK-based qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20(3):519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Christiaens W, Kohn L, Léonard C, Denis A, Daue F, Cleemput I. Models for citizen and patient involvement in health care policy - Part I: exploration of their feasibility and acceptability. Health Services Research (HSR) Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abelson J, Wagner F, DeJean D, Boesveld S, Gauvin FP, Bean S, et al. Public and patient involvement in health technology assessment: A framework for action. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2016;32(4):256–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bilvick Tai BW, Bae YH, Le QA. A systematic review of health economic evaluation studies using the patient’s perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon D, Stafinski T. Role of patient and public participation in health technology assessment and coverage decisions. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(1):75–89. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng EK, Hicks LK. Value based care and patient-centered care: divergent or complementary? Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(4):303–310. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schunemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 10. Integrating values and consumer involvement. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The european parliament and the council of the european union. Directive 2001/83/ec of the european parliament and of the council of 6 november 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use. 2001.

- 13.The council of the european communities. Council directive 93/42/eec of 14 june 1993 concerning medical devices. 1993.

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Classification of Products as Drugs and Devices & Additional Product Classification Issues: Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20993. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/media/80384/download.

- 15.Mühlbacher AC, Juhnke C, Beyer AR, Garner S. Patient-focused benefit-risk analysis to inform regulatory decisions: the European union perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson FR, Zhou M. Patient preferences in regulatory benefit-risk assessments: a US perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, Purnell TS, Bridges JF. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(10):877–892. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weernink MGM, Janus SIM, van Til JA, Raisch DW, van Manen JG, Ijzerman MJ. A systematic review to identify the use of preference elicitation methods in healthcare decision making. Pharm Med. 2014;28(4):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC). Patient centered benefit-risk project report: a framework for incorporating information on patient preferences regarding benefit and risk into regulatory assessments of new medical technology: Medical Device Innovation Consortium; 2015. Available from: http://mdic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/MDIC_PCBR_Framework_Proof5_Web.pdf.

- 20.Dirksen CD, Utens CM, Joore MA, van Barneveld TA, Boer B, Dreesens DH, et al. Integrating evidence on patient preferences in healthcare policy decisions: protocol of the patient-VIP study. Implement Sci. 2013;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soekhai V, Whichello C, Levitan B, Veldwijk J, Pinto CA, Donkers B, et al. Methods for exploring and eliciting patient preferences in the medical product lifecycle: a literature review. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(7):1324–31. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.About PREFER: Uppsala University, Sweden; 2016 [updated 2016-12-14 13:30:48+0100. Available from: http://www.imi-prefer.eu/about/.

- 23.de Bekker-Grob EW, Berlin C, Levitan B, Raza K, Christoforidi K, Cleemput I, et al. Giving Patients’ Preferences a Voice in Medical Treatment Life Cycle: The PREFER Public-Private Project. Patient. 2017;10(3):263-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Selig WKD. Key considerations for developing & integrating patient perspectives in drug development: examination of the duchenne case study: Biotechnology Innovation Organization and Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy; 2016. Available from: https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/BIO_PPMD_Paper_2016.pdf.

- 25.van Til JA, Ijzerman MJ. Why should regulators consider using patient preferences in benefit-risk assessment? PharmacoEconomics. 2014;32(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bridges JFP, Paly VF, Barker E, Kervitsky D. Identifying the benefits and risks of emerging treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Patient. 2014;8(1):85–92. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh K. Incorporating Patient Preferences into Product Development and Value Communication: Why, When and How? The Evidence Forum: A Discourse on Value. 2016. pp. 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart KD, Johnston JA, Matza LS, Curtis SE, Havel HA, Sweetana SA, et al. Preference for pharmaceutical formulation and treatment process attributes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1385–1399. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S101821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mühlbacher A, Bethge S. What matters in type 2 diabetes mellitus oral treatment? A discrete choice experiment to evaluate patient preferences. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(9):1125–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10198-015-0750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danner M, Hummel JM, Volz F, Van Manen JG, Wiegard B, Dintsios CM, et al. Integrating patients' views into health technology assessment: analytic hierarchy process (AHP) as a method to elicit patient preferences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(4):369–375. doi: 10.1017/S0266462311000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choice-based Conjoint Analysis – pilot project to identify, weight, and prioritize multiple attributes in the indication “hepatitis C”. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2014. Report No.: GA10–03. [PubMed]

- 32.Evers P, Greene L, Ricciardi M. The importance of early access to medicines for patients suffering from rare diseases. Regul Rapporteur. 2016;13:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow RD, Wankhedkar KP, Mete M. Patients' preferences for selection of endpoints in cardiovascular clinical trials. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives. 2014;4(1):10.3402/jchimp.v4.22643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Smith MY, Hammad TA, Metcalf M, Levitan B, Noel R, Wolka AM, et al. Patient engagement at a tipping point—the need for cultural change across patient, sponsor, and regulator stakeholders: insights from the DIA conference, “patient engagement in benefit risk assessment throughout the life cycle of medical products”. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50(5):546–553. doi: 10.1177/2168479016662902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamuli E, Torgerson D, Northgraves M, Ronaldson S, Cherry L. Identifying the primary outcome for a randomised controlled trial in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of a discrete choice experiment. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10:57. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhuri SE, Ho MP, Irony T, Sheldon M, Lo AW. Patient-centered clinical trials. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(2):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho M, Saha A, McCleary KK, Levitan B, Christopher S, Zandlo K, et al. A Framework for incorporating patient preferences regarding benefits and risks into regulatory assessment of medical technologies. Value Health. 2016;19(6):746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egbrink MO, Ijzerman M. The value of quantitative patient preferences in regulatory benefit-risk assessment. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2014;2:22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Smith MY, Benattia I. The Patient’s voice in pharmacovigilance: pragmatic approaches to building a patient-centric drug safety organization. Drug Saf. 2016;39(9):779–785. doi: 10.1007/s40264-016-0426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marsh K, Caro JJ, Zaiser E, Heywood J, Hamed A. Patient-centered decision making: lessons from multi-criteria decision analysis for quantifying patient preferences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollin IL, Peay HL, Apkon SD, Bridges JFP. Patient-centered benefit-risk assessment in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle & nerve. 2017;55(5):626–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Postmus D, Mavris M, Hillege HL, Salmonson T, Ryll B, Plate A, et al. Incorporating patient preferences into drug development and regulatory decision making: results from a quantitative pilot study with cancer patients, carers, and regulators. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(5):548–554. doi: 10.1002/cpt.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hauber AB, Fairchild AO, Reed Johnson F. Quantifying benefit-risk preferences for medical interventions: an overview of a growing empirical literature. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(4):319–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A. Making good decisions in healthcare with multi-criteria decision analysis: the use, current research and future development of MCDA. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(1):29–40. doi: 10.1007/s40258-015-0203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho MP, Gonzalez JM, Lerner HP, Neuland CY, Whang JM, McMurry-Heath M, et al. Incorporating patient-preference evidence into regulatory decision making. Surgical endoscopy. 2015;29(10):2984–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.The patient’s voice in the evaluation of medicines. European Medicines Agency, Stakeholders and Communication Division; 2013. Report No.: EMA/607864/2013.

- 47.Mühlbacher AC, Bridges JF, Bethge S, Dintsios CM, Schwalm A, Gerber-Grote A, et al. Preferences for antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(2):155–165. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes D, Waddingham EAJ, Mt-Isa S, Goginsky A, Chan E, Downey G, et al. Recommendations for the methodology and visualisation techniques to be used in the assessment of benefit and risk of medicines. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peay HL, Hollin I, Fischer R, Bridges JF. A community-engaged approach to quantifying caregiver preferences for the benefits and risks of emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hummel MJM, Volz F, Van Manen JG, Danner M, Dintsios CM, Ijzerman MJ, et al. Using the analytic hierarchy process to elicit patient preferences: prioritizing multiple outcome measures of antidepressant drug treatment. Patient. 2012;5(4):225–237. doi: 10.1007/BF03262495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morel T, Ayme S, Cassiman D, Simoens S, Morgan M, Vandebroek M. Quantifying benefit-risk preferences for new medicines in rare disease patients and caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muhlbacher AC. Patient-centric HTA: different strokes for different folks. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2015;15(4):591–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Craig BM, Lancsar E, Muhlbacher AC, Brown DS, Ostermann J. Health preference research: an overview. Patient. 2017;10(4):507–510. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mott DJ, Najafzadeh M. Whose preferences should be elicited for use in health-care decision-making? a case study using anticoagulant therapy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(1):33–39. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1115722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Avila M, Becerra V, Guedea F, Suarez JF, Fernandez P, Macias V, et al. Estimating preferences for treatments in patients with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutknecht M, Schaarschmidt ML, Herrlein O, Augustin M. A systematic review on methods used to evaluate patient preferences in psoriasis treatments. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2016;30(9):1454–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Martin-Fernandez J, Polentinos-Castro E, del Cura-Gonzalez MI, Ariza-Cardiel G, Abraira V, Gil-LaCruz AI, et al. Willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life year: an evaluation of attitudes towards risk and preferences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:287. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marsh K, Caro JJ, Hamed A, Zaiser E. Amplifying each patient’s voice: a systematic review of multi-criteria decision analyses involving patients. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):155–162. doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mott DJ. Incorporating quantitative patient preference data into healthcare decision making processes: is HTA falling behind? Patient. 2018;11:249–252. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brooker AS, Carcone S, Witteman W, Krahn M. Quantitative patient preference evidence for health technology assessment: a case study. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):290–300. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy AN, Madhavan SS, Lloyd A. A discrete choice experiment to elicit patient willingness to pay for attributes of treatment-induced symptom relief in comorbid. Insomnia. Manag Care. 2015;24(4):42–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dirksen CD. The use of research evidence on patient preferences in health care decision-making: issues, controversies and moving forward. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(6):785–794. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.948852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mol PG, Arnardottir AH, Straus SM, de Graeff PA, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Quik EH, et al. Understanding drug preferences, different perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(6):978–987. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muhlbacher AC, Johnson FR. Giving Patients a Meaningful Voice in European Health Technology Assessments: The Role of Health Preference Research. Patient. 2017;10(4):527–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Kievit W, Tummers M, Van Hoorn R, Booth A, Mozygemba K, Refolo P, et al. Taking patient heterogeneity and preferences into account in health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(5):562–569. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Irony T, Ho M, Christopher S, Levitan B. Incorporating patient preferences into medical device benefit-risk assessments. Stat Biopharmaceutical Res. 2016;8(3):230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eichler HG, Bloechl-Daum B, Brasseur D, Breckenridge A, Leufkens H, Raine J, et al. The risks of risk aversion in drug regulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(12):907–916. doi: 10.1038/nrd4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Janssen IM, Scheibler F, Gerhardus A. Importance of hemodialysis-related outcomes: comparison of ratings by a self-help group, clinicians, and health technology assessment authors with those by a large reference group of patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2491–2500. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S122319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Collison KA, Patel P, Preece AF, Stanford RH, Sharma RK, Feldman G. A randomized clinical trial comparing the ELLIPTA and HandiHaler dry powder inhalers in patients with COPD: inhaler-specific attributes and overall patient preference. COPD: J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;15(1):46–50. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2017.1400000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hockley K, Ashby D, Das S, Hallgreen C, Mt-Isa S, Waddingham E, et al. Patient and Public Involvement Report: Recommendations for Patient and Public Involvement in the assessment of benefit and risk of medicines. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eichler HG, Abadie E, Baker M, Rasi G. Fifty years after thalidomide; what role for drug regulators? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(5):731–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson FR, Beusterien K, Ozdemir S, Wilson L. Giving patients a meaningful voice in United States regulatory decision making: the role for health preference research. Patient. 2017;10(4):523–526. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0250-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patient-Perspective Value Framework (PPVF): Draft Methodology. Avalere and Milken Institute, FasterCures; 2016.

- 74.Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) – pilot project to elicit patient preferences in the indication “depression”. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2013. [PubMed]

- 75.Janssen EM, Marshall DA, Hauber AB, Bridges JFP. Improving the quality of discrete-choice experiments in health: how can we assess validity and reliability? Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2017;17(6):531–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Tervonen T, Gelhorn H, Sri Bhashyam S, Poon JL, Gries KS, Rentz A, et al. MCDA swing weighting and discrete choice experiments for elicitation of patient benefit-risk preferences: a critical assessment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(12):1483–1491. doi: 10.1002/pds.4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Janssen EM, Longo DR, Bardsley JK, Bridges JF. Education and patient preferences for treating type 2 diabetes: a stratified discrete-choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1729–1736. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S139471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.von Arx LB, Johnson FR, Morkbak MR, Kjaer T. Be careful what you ask for: effects of benefit descriptions on diabetes Patients' benefit-risk tradeoff preferences. Value Health. 2017;20(4):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wolka AM, Fairchild AO, Reed SD, Anglin G, Johnson FR, Siegel M, et al. Effective partnering in conducting benefit-risk patient preference studies: perspectives from a patient advocacy organization, a pharmaceutical company, and academic stated-preference researchers. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Wolka AM, Fairchild AO, Reed SD, Anglin G, Johnson FR, Siegel M, et al. Effective Partnering in Conducting Benefit-Risk Patient Preference Studies: Perspectives From a Patient Advocacy Organization, a Pharmaceutical Company, and Academic Stated-Preference Researchers. Therapeutic innovation & regulatory science. 2018;52(4):507–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Patient involvement in the HTA decision-making process. Innovative Medicines Initiative, European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI); 2016.

- 82.Rummel M, Kim TM, Aversa F, Brugger W, Capochiani E, Plenteda C, et al. Preference for subcutaneous or intravenous administration of rituximab among patients with untreated CD20+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or follicular lymphoma: results from a prospective, randomized, open-label, crossover study (PrefMab). Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2017;28(4):836–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search queries (DOCX 98 kb)

Included literature (DOCX 193 kb)

Coding tree (DOCX 96 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.