Abstract

The underlying mechanisms of breast cancer cells metastasizing to distant sites are complex and multifactorial. Bone sialoprotein (BSP) and αvβ3 integrin were reported to promote the metastatic progress of breast cancer cells, particularly metastasis to bone. Most theories presume that BSP promotes breast cancer metastasis by binding to αvβ3 integrin. Interestingly, we found the αvβ3 integrin decreased in BSP silenced cells (BSPi), which have weak ability to form bone metastases. However, the relevance of their expression in primary tumor and the way they participate in metastasis are not clear. In this study, we evaluated the relationship between BSP, αvβ3 integrin levels, and the bone metastatic ability of breast cancer cells in patient tissues, and the data indicated that the αvβ3 integrin level is closely correlated to BSP level and metastatic potential. Overexpression of αvβ3 integrin in cancer cells could reverse the effect of BSPi in vitro and promote bone metastasis in a mouse model, whereas knockdown of αvβ3 integrin have effects just like BSPi. Moreover, The Cancer Genome Atlas data and RT‐PCR analysis have also shown that SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B might be involved in this process. Thus, we propose that αvβ3 integrin is one of the downstream factors regulated by BSP in the breast cancer‐bone metastatic cascade.

Keywords: αvβ3 integrin, bone sialoprotein, breast cancer, gene expression, metastasis

Abbreviations

- BRCA

breast invasive carcinoma

- BSP

bone sialoprotein

- BSPi

231BO cells with IBSP gene silenced

- CT

computed tomography

- ER

estrogen receptor

- KCNK2

potassium two pore domain channel subfamily K member 2

- OPN

osteopontin

- PR

progesterone receptor

- PTK2B

protein tyrosine kinase 2β

- SPP1

secreted phosphoprotein 1

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

1. INTRODUCTION

Metastasis is the main cause of death for breast cancer patients. The mechanisms underlying breast cancer cells metastasizing to distant sites are complex and multifactorial, which require the coordinated spatiotemporal expression of oncogenes and antioncogenes. Accumulating data suggest that metastatic dissemination often occurs early during tumor formation.1 Thus, there is great value in learning more about the cell features that are correlated with high potential of metastasis in primary tumor.

Bone sialoprotein, encoded by the IBSP gene, is a phosphorylated and glycosylated protein secreted by bone matrix and cancer cells. Many studies have indicated that high BSP expression correlates with increased tumor grade and predicts a poorer prognosis of patients with breast or prostate cancer, or glioma.2, 3, 4 Bone sialoprotein could modulate cell functions like proliferation, apoptosis, adhesion, migration, angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling.5, 6 Moreover, anti‐BSP Ab was reported to reduce osteolysis while inducing bone formation in a nude rat model.7, 8 The knockdown of BSP caused significant decrease on proliferation, migration, and clone formation in vitro, and inhibited bone metastasis in the mouse model.9, 10 Data have shown that BSP possesses a polyglutamate sequence that mediates binding to hydroxyapatite crystals.11, 12 Bone sialoprotein also contains an integrin binding RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp) sequence, which could mediate protein binding to the cell surface13 and promote interactions between cells and the bone matrix through αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin.14

As an important member of the integrin family, αvβ3 integrin shows a wide range of functions in tumors and is associated with angiogenesis, cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of different cancer types.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Moreover, it is an indicator of increased bone metastasis and decreased patient survival time.21, 22 Decreasing the levels of αv and β3 integrin subunits in cells can suppress cancer metastasis.23 The anti‐αv integrin mAb intetumumab could bind with cell surface proteins important for adhesion, invasion, and angiogenesis in the metastatic cascade.24 Studies on its mechanism showed that αvβ3 integrin could bind with the components of ECM to form focal adhesions.16 Furthermore, β3 integrin is associated with cancer stem cells.25 β3 integrin could cooperate with transforming growth factor‐β to form β3 integrin‐transforming growth factor‐β receptor type II complexes and induce epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) by activating MAPKs in cancer cells.18 Additionally, αvβ3 integrin could facilitate FAKs and activate FAK‐dependent cytokines to promote cell migration and invasion.20 More recently, research showed that tumor exosome integrins prepare a favorable microenvironment at future metastatic sites and mediate nonrandom patterns of metastasis.26 Thus, we propose that new antagonists be explored in the future.

No doubt that the binding of BSP and αvβ3 integrin could contribute to metastasis formation of breast cancer cells, particularly bone metastasis. Study has revealed that αv integrin chain is markedly reduced in BSP(−/−) osteoclasts.27 Expression of BSP but not an integrin‐binding mutant (BSP‐KAE) in tumor cell lines could increase the levels of αv‐containing integrins and the number of mature focal adhesions.28 Our previous study showed that the expression of αvβ3 integrins decreased in the BSP‐silenced cells whereas ectopic BSP expression increased the expression of αvβ3 integrins.9 Due to the important role of BSP and αvβ3 integrin in breast cancer metastasis, future studies are warranted to identify the relationship of their expression in primary sites and the mechanism through which they affect bone metastasis. In this study, we investigated the expression of BSP and αv and β3 integrins in primary cancers, analyzed their mRNA levels in TCGA, and explored their roles in the process of breast cancer bone metastasis by upregulating or downregulating their expression. The results indicate that the BSP‐αvβ3 integrin axis promotes breast cancer cells metastasizing to the bone.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patient samples collection, H&E staining, and immunohistochemistry

Tissues of breast cancer patients with invasive ductal carcinoma were collected in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the General Hospital of Southern Theater Command. Three‐micron thick sections of formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated. For H&E staining, hematoxylin was added for 5 minutes, and eosin for 1 minute. For immunohistochemistry, Abs (Table S1) were applied on tissue sections for 12 hours and incubated at 4°C in a humidity chamber. After treating with the Elivision plus Polymer HRP (Mouse/Rabbit) IHC Kit (kit 9902; MXBR Biotechnologies), the antigen‐Ab binding was detected by DAB. Images were taken using an Olympus BX‐51 fluorescence microscope. Paracancer tissue was used as the negative control tissue and PBS was used instead of primary Ab as the negative control reagent. A semiquantitative scoring method was applied to classify the quantity and intensity of IHC staining of candidate markers. Based on the percentage of positive cells, the quantity score was defined as: 1, 0%‐25%; 2, 26%‐50%; 3, 51%‐75%; and 4, 76%‐100%. The intensity score was defined as: 0, no appreciable staining in the tumor cells; 1, barely appreciable staining; 2, readily appreciable staining; 3, strong staining. A total score were yielded by multiplying quantity and intensity score with a range between 0 and 12. If the total score was 8 or higher, we identified this protein is highly expressed.

The patients’ clinical and pathological data were recorded, including age, sex, tumor size, and TNM stage when the operation was carried out. The ER, PR and cerBb‐2 data were recorded as negative (less than 5% positive cells) or positive (5% or more positive cells) for statistical analysis. The follow‐up medical records of tumor patients were traced until December 19, 2017, meaning that each patient had hospitalization and outpatient data at our hospital for at least 5 years.

2.2. Cells and animals

MDA‐MB‐231 (231) and MDA‐MB‐231BO (231BO) cell lines were generously provided by Dr. Toshiyuki Yoneda29; 231BO has high potential to form bone metastasis. 293T cells were purchased from ATCC. MCF7 and PC3 cells were purchased from the Stem Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The BSPi cells were generated from 231BO in our laboratory. Breast cancer cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone), whereas PC3 cells were cultured in F12 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone), in a humidified culture condition with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Female athymic BALB/c nude mice, age‐matched between 4 and 6 weeks, were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of South Medical University, and housed in a pathogen‐free animal facility.

2.3. Gene overexpression by lentivirus vector

The ORF expression vectors containing ITGAV(NM_002210.3) and ITGB3(NM_000212.2) gene fragments and their negative control vectors were synthesized, and the recombinant lentiviruses were packaged into 293T cells using the Lenti‐Pac HIV expression package kit (GeneCopoeia). After 48 hours, lentiviruses were collected for infection. For each well, 0.5 mL virus suspension was prepared with polybrene at a final concentration of 8 μg/mL. The cells with lentivirus were first incubated at 4°C for 2 hours, then transferred to an incubator at 37°C for 10 hours. Finally, cells were selected by neomycin (600 μg/mL G418) and hygromycin B (800 μg/mL) to obtain the respective overexpressed populations used for subsequent analyses.

2.4. Silencing expression by siRNA transfection

The siRNA targeting human IBSP, ITGAV, and ITGB3 (Table S2) were synthesized by Synbio Technologies. Cells were planted in 24‐well plates with a density of 2.0 × 105 cells/well 24 hours prior to siRNA transfection to ensure a 70%–80% confluence at the time of transfection. Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) was used for the transfection of siRNAs. The effects on mRNA levels were measured at 48 hours after transfection; protein levels and cell characters were measured after 72 hours. Nontargeting siRNA was used as a negative control.

2.5. Western blot analysis

For western blot analysis, proteins on PVDF membranes were incubated with specific Abs (Table S1) at 4°C overnight and secondary Abs at 37°C for 1 hour, and visualized with an ECL detection kit (Millipore). Densitometry of western blotting was undertaken with ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html) and values were normalized to GAPDH.

2.6. Quantitative real‐time PCR and RNA sequencing

Reverse transcription was carried out using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara), and quantitative RT‐PCR was carried out using Bestar SybrGreen qPCR Mastermix (DBI) with primers indicated in Table S3. Data analysis was undertaken using the 2−ΔΔCT method, and all sample values were normalized to the GAPDH expression value.

For RNA sequencing, an Agilent 2100 Bio analyzer (Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit) was used for the total RNA sample QC. Then we undertook RNA sequencing of 231, 231BO, E, and β3 cells using the BGISEQ‐500 platform (BGI). The software SOAPnuke (BGI) was used to filter reads. We mapped clean reads to references using Bowtie2, and then calculated gene expression levels with the software package RSEM for estimating gene and isoform expression levels from RNA‐Seq data. We then calculated the Pearson correlation between all samples using cor, undertook hierarchical clustering between all samples using hclust, carried out principal components analysis (PCA) with all samples using princomp, and drew the diagrams with ggplot2 with functions of R.

2.7. Proliferation assays

Cell proliferation ability was quantified by CCK‐8 (Dojindo) assay. Cells were seeded into a 96‐well plate with 3000 cells per well and incubated at 37°C for 0‐6 days. Thereafter, 10 μL CCK‐8 solution was added to 96‐well plates. After incubation for 2 hours, cell viability was measured by the absorbance at 450 nm.

2.8. Wound healing assay

Confluent cells were scratched with a sterile 200 μL pipette tip to generate a defined scratch wound. We removed the detached cells by washing with PBS 3 times and then incubated the cells with fresh medium with 1% FBS. Images were taken using a Leica DMI4000B microscope at 0 and 24 hours at fixed locations on the plate and compared to the starting position. The wound healing rates were measured using ImageJ software.

2.9. Matrigel invasion assay

Matrigel invasion assay was undertaken using a Transwell 24‐well plate with 8.0 μm polycarbonate membrane (Corning). The inserts were coated with 60 μL basement membrane Matrigel diluted to 1:3 with DMEM, air‐dried and hydrated with 50 μL serum‐free DMEM. Cells at the density of 5 × 104 cells/insert were seeded in serum‐free medium in the upper inserts. Medium with 20% FBS was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. After incubation for 24 hours, the noninvading cells were removed by a cotton swab and the inserts were fixed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes. Filters were photographed and the steps were repeated 3 times.

2.10. Flow cytometry detection of apoptosis

We routinely digested and collected the cells, and then incubated them with Guava Nexin reagent (Millipore) at room temperature for 20 minutes in the dark. The stained cells were detected using Guava easyCyte 5HT system (Merck Millipore), and the percentage of apoptosis detected by flow cytometry was analyzed using GuavaSoft 2.2.7 software.

2.11. Mouse model for breast cancer metastasis

We established the mouse model for breast cancer metastasis by injecting breast cancer cells into their left ventricle as described by Campbell et al.30 Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (3%) and maintained under anesthesia through a nose cone. Breast cancer cells at a density of 2 × 105 cells/100 mL were injected into the left ventricle of anesthetized nude mice. Phosphate‐buffered saline was used as the negative control. After being fed in the pathogen‐free facility for 4 weeks or appearing to develop signs of morbidity, the mice were anesthetized and examined using a Latheta LCT‐200 X‐ray Scanner (Hitachi Aloka Medical) to detect bone lytic lesions. Then the mice were killed and their tissues were excised immediately, including brains, lungs, tibias, and femurs. After formalin‐fixation, the bone tissues were transferred into a decalcification solution (4% EDTA, pH 7.2) for 4 weeks at 37°C and were embedded with paraffin. Other tissues were embedded without decalcification. For histological study, 3 μm sections were stained with H&E. All experiments and procedures were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Southern Theater Command.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were undertaken using SPSS 19.0 software. The results are presented as mean ± SD, with P < .05 considered as statistically significant. For the mice experimental data, we used the Kruskal‐Wallis test to compare the metastatic rates among groups. For patients’ clinical and pathological data, we used Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to study the relationship between BSP and αvβ3 integrin. The protein expression in young (age less than 50 years) and old (age 50 years or older) groups was compared using the Mann‐Whitney test. Then Kruskal‐Wallis tests were applied to study the relationship between the metastatic capacity of breast cancer and protein expression. For TCGA data analysis, breast cancer mRNA expression data of TCGA BRCA was downloaded from TCGA data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). R language package “Hmisc” was used for the correlation analysis of gene expression. The least significant difference (LSD) test was used in multiple comparisons, and P values were corrected by the Bonferroni method.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Expression of BSP and αvβ3 integrin correlates with breast cancer metastases

By searching in the information retrieval system of the General Hospital of Southern Theater Command, we found 270 cases of breast cancer with bone metastases from January 2000 to November 2012. After removing the cases that did not undergo surgery in our hospital, only 32 cases of infiltrative ductal carcinoma combined with bone metastases and complete pathological records were selected for further study. In addition, we chose 10 cases with distant metastasis but not in bone, 11 cases with lymphatic metastasis, and 6 cases with no metastasis for detection and data analysis. All 59 patients with invasive breast ductal carcinoma were female. The oldest was 79 years old, and the youngest was 28. The median age was 50 years. Clinical data, pathological data, and immunohistochemical staining results of these primary tumors were recorded in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pathologic features and immunohistochemical results of breast cancer patients (n = 59)

| Items | Total | ER | PR | cerBb‐2 | Ki‐67 | BSP | αv‐integrin | β3‐integrin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | NC | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | ||

| Age, years | ||||||||||||||||

| <50 | 30 | 11 | 19 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 12 | 2 | 22 | 6 | 4 | 26 | 7 | 23 | 4 | 26 |

| >50 | 29 | 10 | 19 | 12 | 17 | 23 | 6 | 2 | 19 | 8 | 6 | 23 | 6 | 23 | 9 | 20 |

| TNM stage | ||||||||||||||||

| I | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| II | 13 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| III | 20 | 6 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 19 | 3 | 17 | 3 | 17 |

| IV | 25 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 9 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 23 | 3 | 22 | 3 | 22 |

| Metastatic sites | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Lymph node | 11 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 |

| Organs | 10 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 9 |

| Bone | 20 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 18 | 3 | 17 |

| Bone and organs | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 11 |

Abbreviations: BSP, bone sialoprotein; ER, estrogen receptor; High, immunohistochemical staining score ≥8; Low, immunohistochemical staining score <8; NC, not clear; Neg, negative (<5% positive cells); Pos, positive (≥5% positive cells); PR, progesterone receptor.

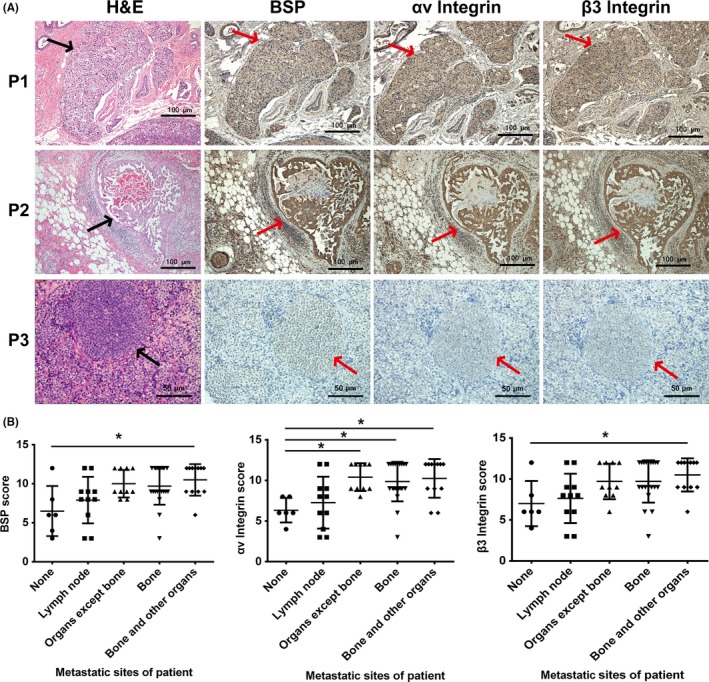

The Spearman correlation analysis of immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1A) showed positive pairwise correlations among BSP, αv integrin, and β3 integrin in clinical specimens of breast infiltrative ductal carcinoma (BSP vs αv integrin: r = 0.890, P < .001; BSP vs β3 integrin: r = 0.949, P < .001; αv integrin vs β3 integrin: r = 0.875, P < .001). Using the Kruskal‐Wallis test, the χ2 and P values of gene expression in patients with different distal metastases were as follows: BSP, χ2 = 14.479, P = .006; αv integrin, χ2 = 14.926, P = .005; and β3 integrin, χ2 = 10.816, P = .029. These results suggest that the levels of BSP, αv integrin, and β3 integrin in primary breast invasive ductal carcinoma are closely related to distant metastasis. In particular, high expression was observed in most of patients with distal organ metastasis, such as patient 1 and patient 2, compared with patient 3 with no distal organ metastasis (Figure 1A). However, there was no significant correlation between their expression and organ‐specific metastasis (Figure 1B). We also analyzed ER, PR, cerBb‐2, and Ki‐67, but no significant correlation was found with organ‐specific metastasis (Table 1). Moreover, no significant relevance was found between expression of these proteins and age.

Figure 1.

Expression of bone sialoprotein (BSP) and αvβ3 integrin in primary tumors of 3 breast cancer patients. A, H&E and immunohistochemical staining of serial sections of formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded in situ breast cancer tissue. Patient 3 (P3), without breast cancer metastasis, showed both low expression of BSP and αvβ3 integrin, whereas P1 and P2 with breast cancer metastasis highly expressed both BSP and αvβ3 integrin. Arrows indicate in situ breast cancer B, Correlation analysis of metastatic sites and BSP scores, αv integrin scores, and β3 integrin scores

3.2. Overexpression of αv or β3 integrin could reverse some effects of IBSP gene silencing

In our previous study, we found that IBSP gene silencing could decrease the level of αvβ3 integrin in bone‐seeking breast cancer cell line 231BO, and inhibit migration, invasion, and bone metastasis in the mouse model.9 A similar phenomenon was observed when analyses were applied to human breast cancer cell line MCF7 and human prostate cancer cell line PC3 (Figure S1).

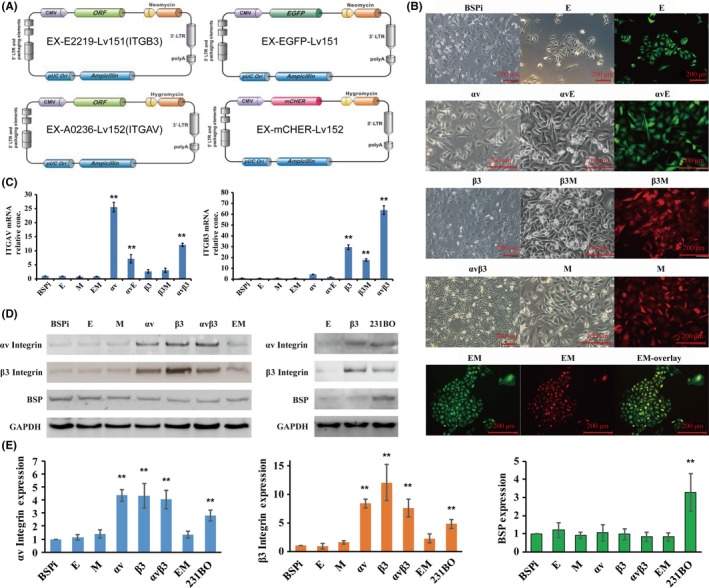

To further study the relationship between BSP and αvβ3 integrin in breast cancer metastasis, we transfected BSPi cells with overexpression vectors (Figure 2A) and obtained 8 kinds of cells (Figure 2B): 231BO‐BSPi‐αv (αv) with αv integrin overexpression, and its control 231BO‐BSPi‐mCHER (M) with red fluorescent protein mcherry expression; 231BO‐BSPi‐β3 (β3) with β3 integrin overexpression, and its control 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP (E) with green fluorescent protein EGFP expression; 231BO‐BSPi‐αvβ3 (αvβ3) with both αv and β3 integrin overexpression, and its control 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP‐mCHER (EM) with both EGFP and mCHER expression; and 231BO‐BSPi‐αv‐EGFP (αvE) and 231BO‐BSPi‐β3‐mCHER (β3M) expressing both integrin and fluorescent protein. Using RT‐PCR, we found that ITGAV mRNA significantly increased in αv, αvE, and αvβ3 cells, and slightly increased in β3 and β3M cells (Figure 2C). Similarly, ITGB3 mRNA significantly increased in β3, β3M, and αvβ3 cells, and slightly increased in αv and αvE cells. The results of western blot revealed that both αv and β3 integrin increased significantly in αv, β3, and αvβ3 cells (Figure 2D,E). Thus, we believe there is a close connection between ITGAV and ITGB3 expression.

Figure 2.

Establishment of αv and β3 integrin‐overexpressing cells. A, Schematic of ITGAV and ITGB3 overexpression vectors. B, Micrograph of cells after transfection. C, RT‐PCR assessment of ITGAV and ITGB3 gene overexpression after transfection. D,E, Western blot assessment of ITGAV and ITGB3 gene overexpression after transfection. GAPDH is the negative control. Quantification was carried out using ImageJ software. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. * P < .05, ** P < .01. αv, 231BO‐BSPi‐αv; αvβ3, 231BO‐BSPi‐αvβ3; αvE, 231BO‐BSPi‐αv‐EGFP; β3, 231BO‐BSPi‐β3; β3M, 231BO‐BSPi‐β3‐mCHER; BSPi, 231BO cells with IBSP gene silenced; E, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP; EM, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP‐mCHER; M, 231BO‐BSPi‐mCHER

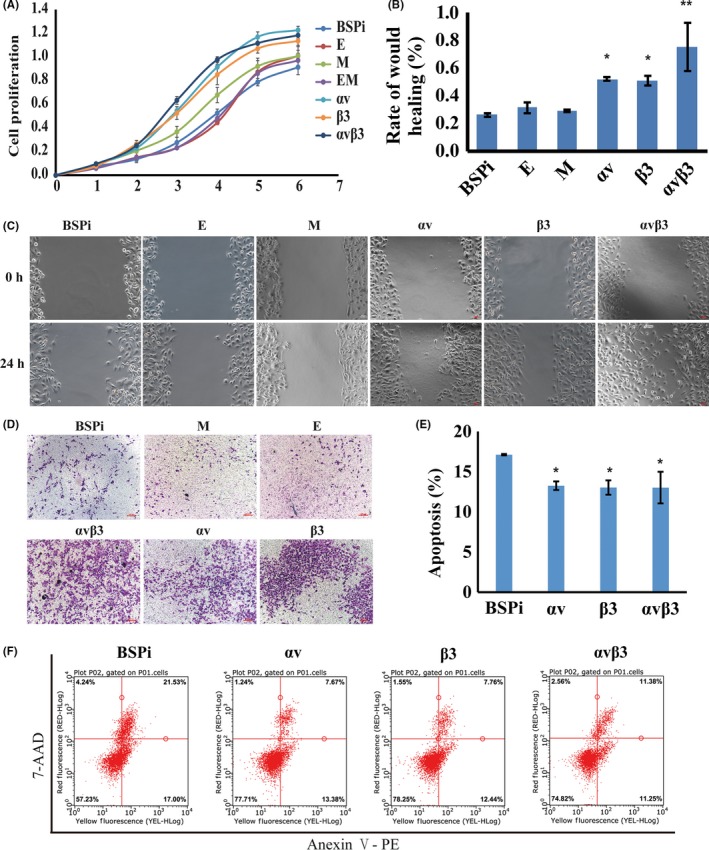

The CCK‐8 detection results revealed that the proliferation rates of αv, β3, and αvβ3 were significantly higher than that of BSPi, E, and EM cells after the third day (P < .05) (Figure 3A). The wound healing speed of αv, β3, and αvβ3 cells was faster than that of other cells at 24 hours (Figure 3B,C). In the Transwell assay, the number of cells that migrated through Matrigel was significantly increased in αv, β3, and αvβ3 groups (Figure 3D). Moreover, cell apoptosis decreased slightly in αv, β3, and αvβ3 groups (Figure 3E,F). All these data suggested that ITGAV or ITGB3 gene overexpression in IBSP gene silenced cells could enhance the proliferation, migration, and invasion activity of breast cancer cells in vitro, and reduce the cell apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Effect of αv and β3 integrin overexpression on proliferation, migration, and invasion of human breast cancer cells in vitro. A, Cell growth curves detected by CCK‐8 assay. B,C, Wound healing assay to detect migration ability. D, Cell invasion ability determined by Transwell assay. E,F, Cell apoptosis detected by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. * P < .05, ** P < .01. αv, 231BO‐BSPi‐αv; αvβ3, 231BO‐BSPi‐αvβ3; β3, 231BO‐BSPi‐β3; BSPI, 231BO cells with IBSP gene silenced; E, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP; EM, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP‐mCHER; M, 231BO‐BSPi‐mCHER

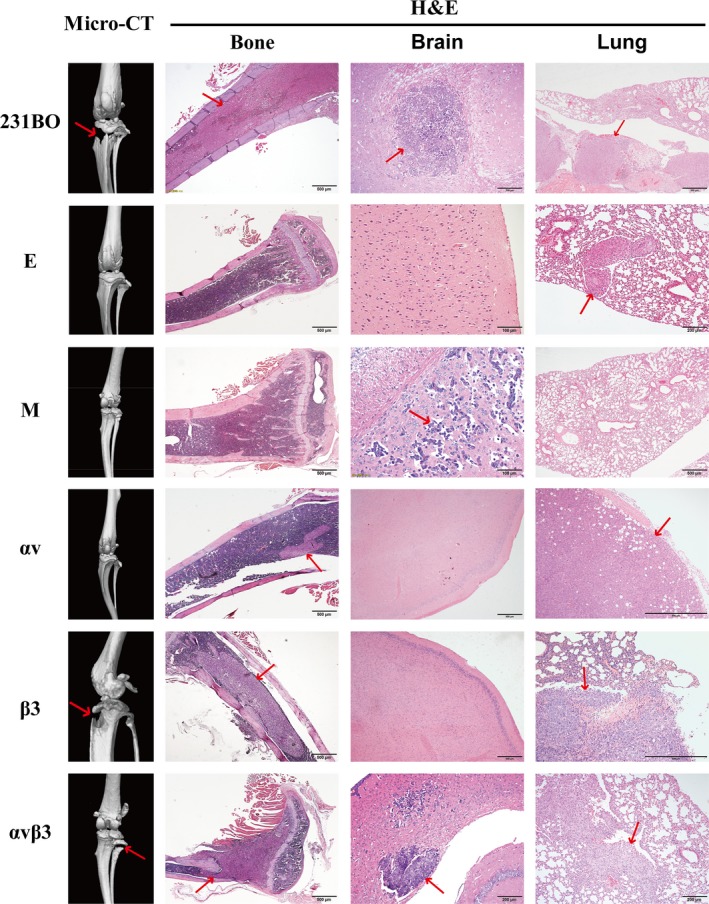

We also established a bone metastatic mouse model by injecting breast cancer cells into the left ventricle. By observing micro‐CT and H&E staining (Figure 4), we found 14 bone metastases, 10 lung metastases, and 3 brain metastases (Table 2). The results confirmed findings from previous studies,9, 29 which showed that 231BO is a bone‐seeking breast cancer cell line, and IBSP gene silencing could decrease its bone metastatic ability. Moreover, cells with high β3 expression (β3, αvβ3, and 231BO) might have greater potential to form bone metastases, although the BSP expression is still low in β3 and αvβ3 cells compared to E and M cells, which have decreased expression of both BSP and β3 integrin. That is to say, ITGB3 gene overexpression might partly reverse the decline of bone metastasis in vivo induced by BSP silencing. However, no significant difference was found in lung metastasis or brain metastasis between these groups.

Figure 4.

Left panels, micro‐computed tomography photographs of legs of mice inoculated with different breast cancer cells. Right panels, H&E staining of tissue slices of brain, lung, and legs. Arrows indicate metastases. αv, 231BO‐BSPi‐αv; αvβ3, 231BO‐BSPi‐αvβ3; β3, 231BO‐BSPi‐β3; BSPI, 231BO cells with IBSP gene silenced; E, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP; EM, 231BO‐BSPi‐EGFP‐mCHER; M, 231BO‐BSPi‐mCHER

Table 2.

Metastatic rate of breast cancer cells in nude mice (n = 42)

| Group | 231BO (n = 6) (%) | E (n = 8) (%) | M (n = 5) (%) | αv (n = 6) (%) | β3 (n = 10) (%) | αvβ3 (n = 7) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone metastasis (P = .016) | 50 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 70 | 43 |

| Lung metastasis (P = .485) | 50 | 25 | 0 | 17 | 30 | 14 |

| Brain metastasis (P = .501) | 17 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

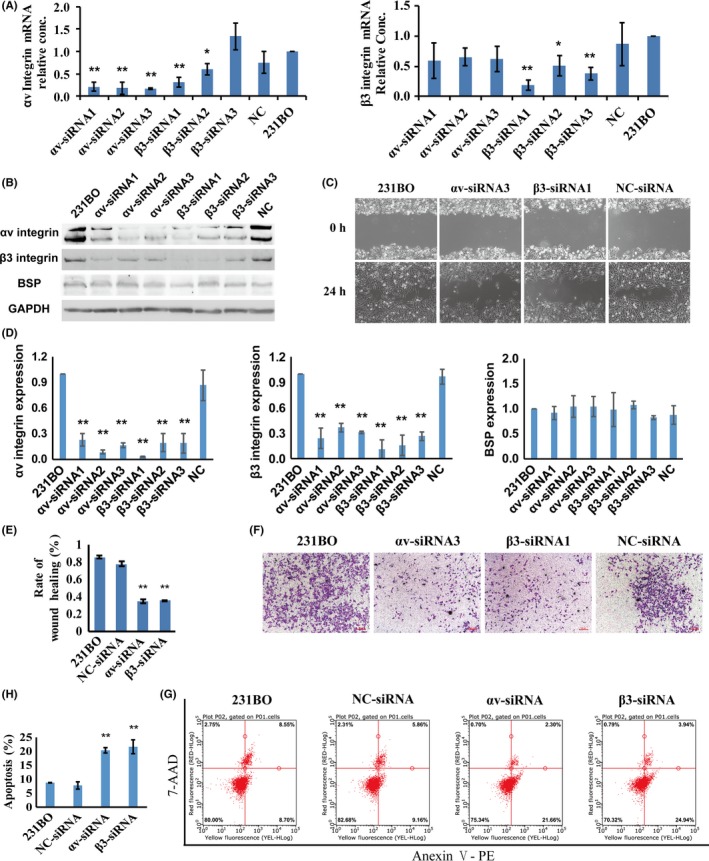

3.3. αv‐siRNA and β3‐siRNA could decrease migration and invasion ability and promote apoptosis of 231BO cells

In order to verify the role of αvβ3 integrin, we designed siRNAs to knock down αv and β3 integrin expression. The results of RT‐PCR showed that αv‐siRNAs decreased the ITGAV mRNA level, and β3‐siRNAs decreased the ITGB3 mRNA level (Figure 5A). The protein levels of both αv and β3 integrin decreased after αv‐siRNA or β3‐siRNA transfection (Figure 5B,D). The migration and invasion ability decreased (Figure 5C,E,F), while cell apoptosis increased (Figure 5G,H), in αv and β3 knockdown cells. All these data indicate that αv and β3 integrin play a very important role in breast cancer bone metastasis.

Figure 5.

αv‐siRNA and β3‐siRNA could decrease the migration and invasion ability, and promote apoptosis, of 231BO breast cancer cells. A, RT‐PCR assessment of ITGAV and ITGB3 gene knockdown by siRNA in 231BO cells. B,D, Western blot assessment of ITGAV and ITGB3 gene knockdown by siRNA in 231BO cells. C,E, Wound healing assay to detect migration ability. F, Cell invasion ability determined by Transwell assay. G,H, Cell apoptosis detected by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. * P < .05, ** P < .01

3.4. Bone sialoprotein‐αvβ3 axis regulates SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B expression

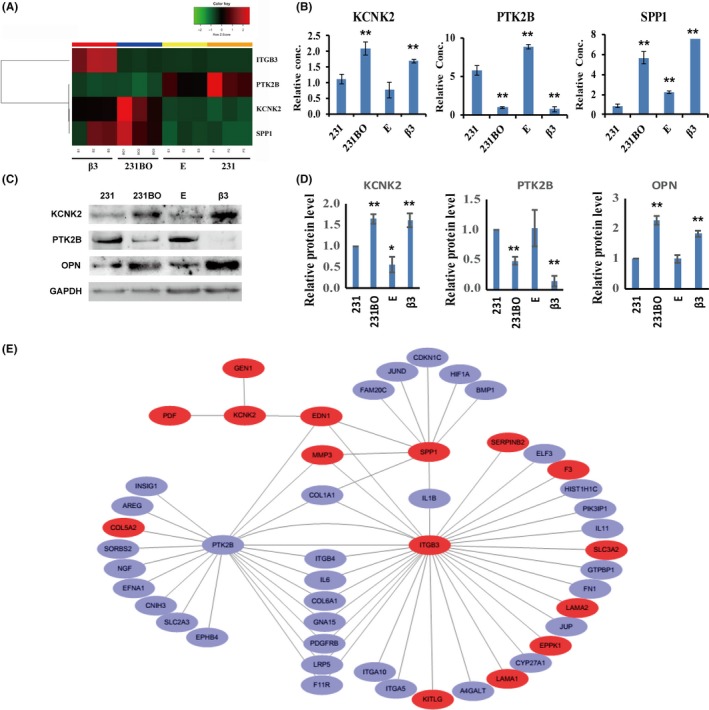

To study the signal pathways between β3 integrin and breast cancer bone metastasis, RNA sequencing was undertaken with MDA‐MB‐231 (231), 231BO, E, and β3 cells. A total of 18 143 genes were detected. The results revealed that 5.2% of genes were modulated in response to BSP silencing and EGFP vector transfection (E vs 231BO), and 1.7% of genes were modulated in response to integrin β3 overexpression (β3 vs E). According to RNA sequencing data, the levels of SPP1 and KCNK2 are upregulated in 231BO and β3 cells, which have strong ability to form bone metastases, while the level of PTK2B is decreased (Figure 6A). These results were verified by RT‐PCR and western blot analyses (Figure 6B‐D). To confirm whether the effect of αvβ3 integrin is of general significance, MCF7 and PC3 cells were selected for validation. The results of RT‐PCR and western blot analysis (Figure S2A‐E) showed that, in both MCF7 and PC3 cells, ITGB3, SPP1, and KCNK2 were upregulated when αv or β3 integrin were overexpressed, and downregulated when αv or β3 integrin were silenced. However, PTK2B showed the opposite effect. Furthermore, αv and β3 integrin have the same effect on cell migration and invasion of MCF7 and PC3 with 231BO cells (Figure S2F,G).

Figure 6.

Results of RNA sequencing. A, Expression of ITGB3,PTK2B,SPP1, and KCNK2 mRNA in breast cancer cells by RNA sequencing. B, Expression of PTK2B,SPP1, and KCNK2 mRNA in breast cancer cells by RT‐PCR. C,D, Protein levels of KCNK2, PTK2B, and osteopontin (OPN; encoded by SPP1 gene) in breast cancer cells by western blot analysis. E, Cluster analysis chart of ITGB3, PTK2B, SPP1, KCNK2 and their relative genes. 231, breast cancer cells MDA‐MB‐231; 231BO, bone‐seeking breast cancer cells MDA‐MB‐231BO; β3, 231BO cells transfected by IBSP‐siRNA and β3 overexpressing vector; E, Control cells of β3 cells, established from 231BO cells after IBSP‐siRNA and EX‐EGFP‐Lv151 vector transfection. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. * P < .05, ** P < .01

Through bioinformatics analysis and a review of published reports, it is suggested that ITGB3, SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B genes could play an important role in promoting the bone metastasis of breast cancer (Figure 6E). The above data imply that SPP1 and KCNK2 might be positively correlated with breast cancer bone metastasis, whereas PTK2B might be negatively correlated with breast cancer bone metastasis.

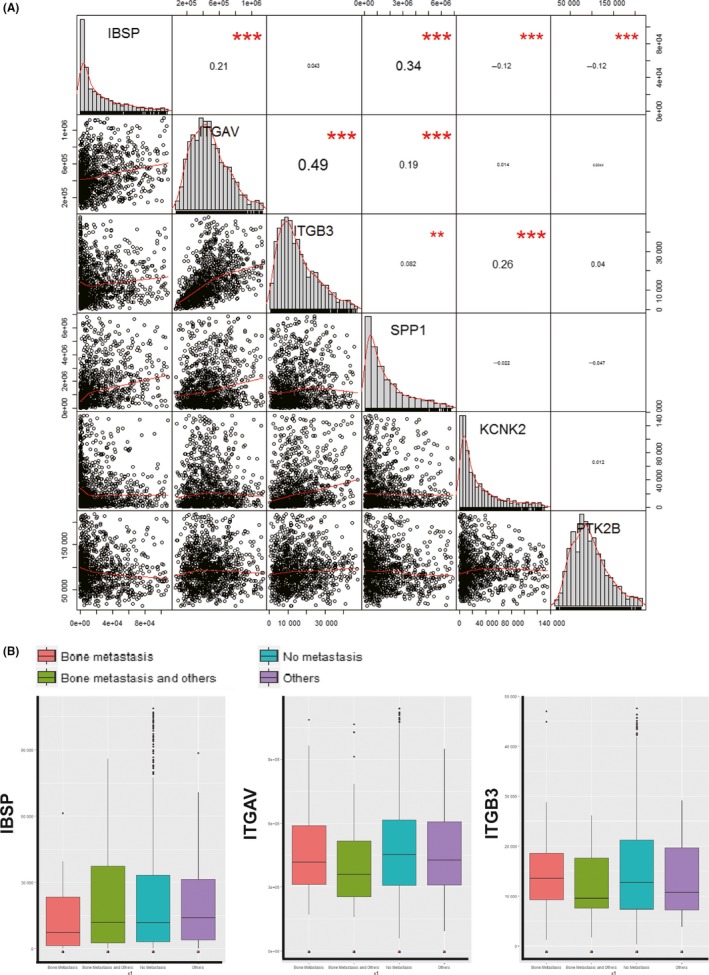

3.5. Gene expression correlation observed in TCGA database

We downloaded the level 3 dataset of TCGA BRCA, which contains a total of 1222 expression data, including 1109 tumor samples and 113 normal samples. Correlation analysis of gene expression was carried out using the R language package “Hmisc”. The result showed that the mRNA level of IBSP was closely related to the levels of ITGAV, SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B in breast cancer samples. Moreover, the ITGB3 level was also closely related to ITGAV, SPP1, and KCNK2, as shown in Figure 7A. These results are consistent with our previous results of immunohistochemical staining of clinical formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded tissue sections and RNA sequencing of the cell lines.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis of gene expression in The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset. A, Correlation analysis of IBSP,ITGAV,ITGB3,SPP1,KCNK2, and PTK2B gene expression. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. B, Relationship between IBSP,ITGAV, and ITGB3 expression and bone metastasis

Among the BRCA samples, there were 79 metastatic samples, including 28 cases with metastases present only in bone or bone marrow, 28 cases with multiple metastases including bone or bone marrow, and 23 cases with metastasis in distant organs. The least significant difference test was used in multiple comparisons, and the P value was corrected by the Bonferroni method. However, there was no significant difference in the mRNA levels of IBSP, ITGAV, or ITGB3 among different groups (Figure 7B).

4. DISCUSSION

Metastasis formation depends on the characteristics of cancer cells and the microenvironment of metastatic sites. Recent studies have reported that cancer cells spread in the early stage of cancer progression,1 so it is important to study the characteristics of cancer cells in situ and explore their bone metastasis potential. Previous studies have shown that BSP expression in primary human breast cancer is associated with bone metastases development.4 Moreover, αvβ3 integrin was abundant in all breast cancer cells in bone metastases. Interestingly, it was only strongly expressed in some primary invasive breast cancers.31 Another study reported that high expression of αvβ3 integrin can promote metastasis in breast cancer.21 Thus, we hypothesized that the level of αvβ3 integrin would be closely related to BSP in primary cancer cells, and their expression would be relevant to the metastatic ability of breast cancer cells.

In this study, we found that BSP was closely related to the expression of αvβ3 integrin. Moreover, their levels in primary breast invasive ductal carcinoma were closely related to distant metastasis. Based on these data, we believe the αvβ3 integrin‐positive and BSP‐positive subclones could be capable of overcoming all barriers during the metastatic process, and be selected to establish distant metastases. Although no significant correlation between their expression and organ‐specific metastasis was observed, we cannot determine whether BSP and αvβ3 integrin play roles in organ selection during metastases formation, because breast cancer patients have a long survival period after surgery, and we cannot track all metastatic records in their lifetime.

With regard to the regulation mechanism, previous studies have suggested that BSP can promote breast cancer migration, invasion, and metastasis by binding to αvβ3 integrin, as αvβ3 integrin showed a broader ability to bind to ligands such as fibronectin, vitronectin, fibrinogen, and thrombospondin.32 In this study, we found that IBSP siRNA decreased the expression of αvβ3 integrin and inhibited the abilities of proliferation, migration, and invasion in MCF7 and PC3 cells, which further proved the result of our previous study.9

In order to further determine the effect of BSP and αvβ3 integrin on the process of bone metastasis, αv and β3 integrin were overexpressed in breast cancer cells, which knocked down BSP activity. The result showed that αvβ3 integrin overexpression could reverse the inhibitory effect of BSPi on tumor bone metastasis. Simultaneously, the abilities of cell migration and invasion decreased significantly in αv and β3 integrin silenced cells. This implied that αvβ3 knockdown could reverse the promoting effect of BSP on breast cancer bone metastasis. Thus, we propose that BSP can regulate bone metastasis by adjusting the expression of αvβ3 integrin as well as through binding to αvβ3 integrin. In the mouse model, inconsistent statistics were observed when bone metastases were detected by H&E staining and micro‐CT. This is because only noticeable osteolytic bone damages could be detected by micro‐CT, and areas of minor damage and metastases in the marrow cavity were missed.

Interestingly, by RNA sequencing, we found cancer cells with high bone metastatic potential showed high level of ITGB3, SPP1, and KCNK2 but low level of PTK2B. In contrast, cancer cells with low bone metastatic potential showed low level of ITGB3, SPP1, and KCNK2 but high level of PTK2B (as the copy number of IBSP is too small, no quantitative analysis of IBSP was carried out). The result also revealed that SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B were up‐ or downregulated with the change of αvβ3 integrin level in MCF7 and PC3 cells.

SPP1 gene encodes OPN, another member of the SIBLING family (as is BSP), which have been reported to be overexpressed in breast cancer and as playing important roles in bone metastasis.33, 34 Similar to BSP, OPN can bind to integrin αvβ3, located on the tumor cell surface, through its RGD motif, to further promote the malignant behavior of tumor cells.35, 36 Research has shown a strong correlation between BSP and OPN in papillary thyroid carcinoma specimens.37 PTK2B, also known as Pyk2, is supposed to be highly expressed in invasive breast cancer and regulates tumor cell invasion and metastasis.38 However, some studies have also shown that Pyk2 exerts tumor‐suppressive effects.39, 40 Therefore, PTK2B could have a dual function in cancer. As a phosphorylated β3 binding partner, Pyk2 could directly bind to the β3 cytoplasmic tail, dependent upon Pyk2‐Tyr‐402 and β3‐Tyr‐747 phosphorylations.41 Thus, it is not surprised that PTK2B is involved in BSP‐αvβ3‐mediated breast cancer bone metastasis. The KCNK2 gene encodes TREK‐1, one of the members of the two pore domain background potassium channel protein family. It has been shown to be overexpressed in many kinds of cancer cells42, 43 and has a significant effect on cell proliferation, apoptosis,44 and cell cycle arrest.45 Moreover, in prostate cancer, TREK‐1 levels were positively associated with Gleason score and T staging. High levels of TREK‐1 expression were related to shorter castration resistance‐free survival.45 Here, we found that ITGB3 has a striking effect on KCNK2 expression, and this might be the way they participate in metastatic regulation.

According to TCGA data, the RNA level of IBSP was closely related to ITGAV, and ITGAV was closely related to ITGB3. However, there was no obvious correlation between these genes and breast cancer metastasis. The possible reasons are outlined below.

Among the 1222 BRCA samples, there were only 79 metastatic samples. If we consider the organ‐specific metastases, the number was even smaller. Many patients were still in the early stage with low degree of malignancy, which was of limited significance for metastatic study.

The samples collected for RNA sequencing might have contained many kinds of cells, including cancer cells, normal breast cells, immune cells, and other components. Therefore, the sequencing results reflect the overall gene level of sample. However, the result of immunohistochemically staining can clearly distinguish the cancer cells with others, so we believe it is more reliable.

The BRCA dataset of TCGA contains multiple types of breast cancer, whereas the immunohistochemically analysis selected only infiltrative ductal carcinoma with a high rate of bone metastasis.

TCGA data were detected at the RNA level, whereas immunohistochemistry was detected at the protein level. We all know that BSP is a highly phosphorylated and glycosylated protein, and αvβ3 integrin is glycosylated as well, undergoing complex modifications after gene transcription and translation. All of these reasons could cause inconsistent results. At least, the above results have demonstrated that the 3 protein levels are closely related to each other, and they might have more complex effects in addition to binding.

For many years, BSP and αvβ3 integrin were considered to be attractive drug targets. Although BSP Abs7, 8, 46, 47 and integrin antagonists48 seem helpful in mouse or rat models, none have been successful in clinical experiments until now. However, antagonism of specific integrin subunits in stringently stratified patient cohorts are emerging as a potential way forward.49 From another perspective, as the specific expression of BSP and αvβ3 integrin is important in invasive primary tumors and bone metastatic sites, they could be used as tumor‐associated antigens to selectively deliver antitumor agents in cancer therapy. We are glad to see that a study has exploited an αvβ6 integrin‐specific peptide to generate a tumor‐targeted photosensitizer, which, when used in photodynamic therapy, resulted in effective ablation of primary lung tumors in mouse models.50

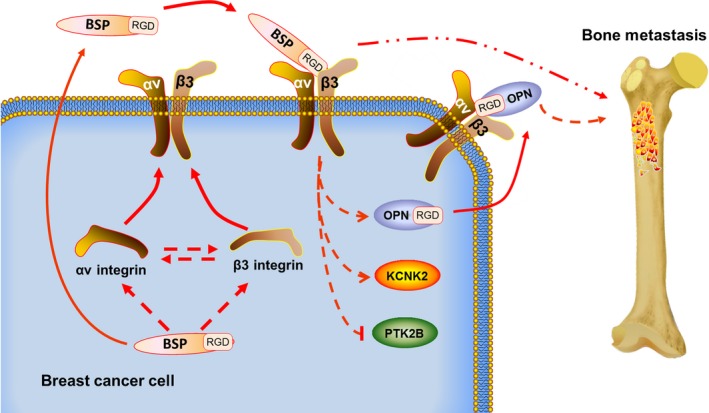

In conclusion, our studies suggest that BSP expression could influence the αvβ3 integrin level in breast cancer cells. The αvβ3 integrin could partly reverse the decreased effect of bone metastasis caused by IBSP gene silencing. In primary breast cancer tissues, the BSP and αv and β3 integrin protein levels were closely related to each other. Cancer cells with high BSP and αv and β3 integrin protein levels might have high potential to form bone metastases. Thus, we believe BSP, together with αv and β3 integrin, regulate breast cancer bone metastasis, and αvβ3 integrin could be one of the downstream factors regulated by BSP. Moreover, SPP1, KCNK2, and PTK2B genes might also take part in this process (Figure 8). Therefore, the BSP‐αvβ3 axis could be a promising target for breast cancer metastatic therapy.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration how bone sialoprotein (BSP) and αvβ3 integrin might promote breast cancer bone metastasis. In breast cancer cells, BSP expression could influence the level of αv and β3 integrin, which in turn promote the expression of each other. Then BSP is released into the extracellular environment, and the αv and β3 integrin are transferred to the membrane, where BSP binds to αvβ3 through its RGD motif. Simultaneously, they could regulate the expression of osteopontin (OPN), KCNK2 and PTK2B. OPN can also binds to αvβ3. All these factors together regulate breast cancer bone metastasis

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81402409), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2015A030313605), and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (B2018144). We also want to thank Nancy Yang at the University of Minnesota for providing English language edits for this manuscript.

Wang L, Song L, Li J, et al. Bone sialoprotein‐αvβ3 integrin axis promotes breast cancer metastasis to the bone. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:3157–3172. 10.1111/cas.14172

Funding information

Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, Grant/Award Number: 2015A030313605; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: No.81402409; Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, Grant/Award Number: B2018144.

Lijie Song is the co‐first author.

Contributor Information

Shuwen Liu, Email: liusw@smu.edu.cn.

Jie Wang, Email: jiew@tom.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hosseini H, Obradović MM, Hoffmann M, et al. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540:552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waltregny D, Bellahcène A, Castronovo V, et al. Prognostic value of bone sialoprotein expression in clinically localized human prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1000‐1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu T, Qin R, Zhou J, et al. High bone sialoprotein (BSP) expression correlates with increased tumor grade and predicts a poorer prognosis of high‐grade glioma patients. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bellahcène A, Kroll M, Liebens F, Castronovo V. Bone sialoprotein expression in primary human breast cancer is associated with bone metastases development. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:665‐670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu B, Guo Z, Lin L, Liu Q. Serum BSP, PSADT, and Spondin‐2 levels in prostate cancer and the diagnostic significance of their ROC curves in bone metastasis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:61‐67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diel IJ, Solomayer E‐F, Seibel MJ, et al. Serum bone sialoprotein in patients with primary breast cancer is a prognostic marker for subsequent bone metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3914‐3919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bäuerle T, Peterschmitt J, Hilbig H, Kiessling F, Armbruster FP, Berger MR. Treatment of bone metastasis induced by MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells with an antibody against bone sialoprotein. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:573‐583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zepp M, Kovacheva M, Altankhuyag M, et al. IDK1 is a rat monoclonal antibody against hypoglycosylated bone sialoprotein with application as biomarker and therapeutic agent in breast cancer skeletal metastasis. J Pathol Clin Res. 2018;4:55‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang J, Wang L, Xia B, Yang C, Lai H, Chen X. BSP gene silencing inhibits migration, invasion, and bone metastasis of MDA‐MB‐231BO human breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kovacheva M, Zepp M, Berger SM, Berger MR. Sustained conditional knockdown reveals intracellular bone sialoprotein as essential for breast cancer skeletal metastasis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris N, Rattray K, Tye C, et al. Functional analysis of bone sialoprotein: identification of the hydroxyapatite‐nucleating and cell‐binding domains by recombinant peptide expression and site‐directed mutagenesis. Bone. 2000;27:795‐802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldberg HA, Warner KJ, Li MC, Hunter GK. Binding of bone sialoprotein, osteopontin and synthetic polypeptides to hydroxyapatite. Connect Tissue Res. 2001;42:25‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wuttke M, Müller S, Nitsche DP, Paulsson M, Hanisch F‐G, Maurer P. Structural characterization of human recombinant and bone‐derived bone sialoprotein functional implications for cell attachment and hydroxyapatite binding. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36839‐36848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sung V, Stubbs Iii J, Fisher L, Aaron A, Thompson EW. Bone sialoprotein supports breast cancer cell adhesion proliferation and migration through differential usage of the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:482‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parvani JG, Galliher‐Beckley AJ, Schiemann BJ, Schiemann WP. Targeted inactivation of β1 integrin induces β3 integrin switching, which drives breast cancer metastasis by TGF‐β. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3449‐3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desgrosellier JS, Barnes LA, Shields DJ, et al. An integrin αvβ 3–c‐Src oncogenic unit promotes anchorage‐independence and tumor progression. Nat Med. 2009;15:1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reynolds LE, Wyder L, Lively JC, et al. Enhanced pathological angiogenesis in mice lacking β 3 integrin or β 3 and β 5 integrins. Nat Med. 2002;8:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. β 3 Integrin and Src facilitate transforming growth factor‐β mediated induction of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seguin L, Kato S, Franovic A, et al. An integrin β 3–KRAS–RalB complex drives tumour stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zheng D‐Q, Woodard AS, Fornaro M, Tallini G, Languino LR. Prostatic carcinoma cell migration via αvβ3 integrin is modulated by a focal adhesion kinase pathway. Can Res. 1999;59:1655‐1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sloan EK, Pouliot N, Stanley KL, et al. Tumor‐specific expression of αvβ3 integrin promotes spontaneous metastasis of breast cancer to bone. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCabe N, De S, Vasanji A, Brainard J, Byzova T. Prostate cancer specific integrin αvβ3 modulates bone metastatic growth and tissue remodeling. Oncogene. 2007;26:6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu H, Radisky DC, Yang D, et al. MYC suppresses cancer metastasis by direct transcriptional silencing of α v and β 3 integrin subunits. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu YJ, Muldoon LL, Gahramanov S, Kraemer DF, Marshall DJ, Neuwelt EA. Targeting αv‐integrins decreased metastasis and increased survival in a nude rat breast cancer brain metastasis model. J Neurooncol. 2012;110:27‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vaillant F, Asselin‐Labat M‐L, Shackleton M, Forrest NC, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. The mammary progenitor marker CD61/β3 integrin identifies cancer stem cells in mouse models of mammary tumorigenesis. Can Res. 2008;68:7711‐7717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoshino A, Costa‐Silva B, Shen T‐L, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boudiffa M, Wade‐Gueye NM, Guignandon A, et al. Bone sialoprotein deficiency impairs osteoclastogenesis and mineral resorption in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2669‐2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gordon JA, Sodek J, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Bone sialoprotein stimulates focal adhesion‐related signaling pathways: role in migration and survival of breast and prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:1118‐1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoneda T, Williams PJ, Hiraga T, Niewolna M, Nishimura R. A bone‐seeking clone exhibits different biological properties from the MDA‐MB‐231 parental human breast cancer cells and a brain‐seeking clone in vivo and in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1486‐1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell JP, Merkel AR, Masood‐Campbell SK, Elefteriou F, Sterling JA. Models of bone metastasis. J Vis Exp. 2012; 4:e4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liapis H, Flath A, Kitazawa S. Integrin alpha V beta 3 expression by bone‐residing breast cancer metastases. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1996;5:127‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901‐3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Small integrin‐binding ligand N‐linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:212‐226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walaszek K, Lower EE, Ziolkowski P, Weber GF. Breast cancer risk in premalignant lesions: osteopontin splice variants indicate prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:1259‐1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anunobi CC, Koli K, Saxena G, Banjo AA, Ogbureke KU. Expression of the SIBLINGs and their MMP partners in human benign and malignant prostate neoplasms. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48038‐48049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pang X, Gong K, Zhang X, Wu S, Cui Y, Qian BZ. Osteopontin as a multifaceted driver of bone metastasis and drug resistance. Pharmacol Res. 2019;144:235‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu G, Guo JJ, Ma ZY, Wang J, Zhou ZW, Wang Y. Correlation between calcification and bone sialoprotein and osteopontin in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2010‐2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Genna A, Lapetina S, Lukic N, et al. Pyk2 and FAK differentially regulate invadopodia formation and function in breast cancer cells. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:375‐395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stanzione R, Picascia A, Chieffi P, et al. Variations of proline‐rich kinase Pyk2 expression correlate with prostate cancer progression. Lab Invest. 2001;81:51‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shen T, Guo Q. Role of Pyk2 in human cancers. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:8172‐8182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Butler B, Blystone SD. Tyrosine phosphorylation of beta3 integrin provides a binding site for Pyk2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14556‐14562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sauter DRP, Sørensen CE, Rapedius M, Brüggemann A, Novak I. pH‐sensitive K+ channel TREK‐1 is a novel target in pancreatic cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:1994‐2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voloshyna I, Besana A, Castillo M, et al. TREK‐1 is a novel molecular target in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1197‐1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Innamaa A, Jackson L, Asher V, et al. Expression and effects of modulation of the K2P potassium channels TREK‐1 (KCNK2) and TREK‐2 (KCNK10) in the normal human ovary and epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:910‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang GM, Wan FN, Qin XJ, et al. Prognostic significance of the TREK‐1 K2P potassium channels in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:18460‐18468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peterschmitt J, Bäuerle T, Berger MR. Effect of zoledronic acid and an antibody against bone sialoprotein II on MDA‐MB‐231 GFP breast cancer cells in vitro and on osteolytic lesions induced in vivo by this cell line in nude rats. Clin Exp Metas. 2007;24:449‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zepp M, Armbruster F, Berger M. Rat monoclonal antibodies against bone sialoprotein II inhibit tumor growth and osteolytic lesions in nude rats induced by MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer. 2010;4:6‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Raab‐Westphal S, Marshall JF, Goodman SL. Integrins as therapeutic targets: successes and cancers. Cancers. 2017;9:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Every step of the way: integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:533‐548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yu X, Gao D, Gao L, et al. Inhibiting metastasis and preventing tumor relapse by triggering host immunity with tumor‐targeted photodynamic therapy using photosensitizer‐loaded functional nanographenes. ACS Nano. 2017;11:10147‐10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials