Abstract

Background—

Atherosclerosis is driven by synergistic interactions between pathological biomechanical, inflammatory and lipid metabolic factors. Our previous studies demonstrated that absence of caveolin-1 (Cav1)/caveolae in hyperlipidemic mice strongly inhibits atherosclerosis, which was attributed to activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and increased production of nitric oxide (NO), reduced inflammation and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) trafficking.

However, the contribution of eNOS activation and NO production in the athero-protection of Cav1 and the exact mechanisms by which Cav1/caveolae controls the pathogenesis of diet-induced atherosclerosis are still not clear.

Methods—

Triple knockout mouse lacking expression of eNOS, Cav1 and Ldlr were generated to explore the role of NO production in Cav1-dependent atheo-protective function. The effects of Cav1 on lipid trafficking, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and vascular inflammation were studied both in vitro and in vivo using a mouse model of diet-induced atherosclerosis. The expression of Cav1 and distribution of caveolae regulated by flow were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining and transmission electron microscopy.

Results—

We found that absence of Cav1 significantly suppressed atherogenesis in Ldlr−/−eNOS−/− mice, demonstrating that athero-suppression is independent of increased NO production. Instead, we find that absence of Cav1/caveolae inhibited LDL transport across the endothelium, pro-atherogenic fibronectin deposition, and disturbed flow-mediated endothelial cell (EC) inflammation. Consistent with the idea that Cav1/caveolae may play a role in early flow-dependent inflammatory priming, distinct patterns of Cav1 expression and caveolae distribution were observed in athero-prone and athero-resistant areas of the aortic arch even in wild-type mice.

Conclusions—

The above findings support a role for Cav1/caveolae as a central regulator of atherosclerosis that links biomechanical, metabolic and inflammatory pathways independent of endothelial eNOS activation and NO production.

Keywords: Caveolin-1. Caveolae, eNOS, LDL transcytosis, inflammation, atherosclerosis, extracellular matrix, fibronectin

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is a complex vascular disease characterized by the progressive accumulation of lipids, inflammatory cells and fibrous material in the sub-endothelial space of large arteries. Despite advances in prevention and treatment it remains the leading cause of death in developed nations1. Atherosclerotic lesions occur preferentially in areas of arterial curvature or branching where shear stress from blood flow is lower, oscillatory or multi-directional, so-called disturbed flow. These flow patterns act on vascular endothelial cells to activate multiple inflammatory pathways, increased permeability, oxidative stress, NF-κB activity, and expression of receptors and cytokines that recruit leukocytes. Disturbed flow also promotes changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM), inducing fibronectin expression and deposition2 that contributes to endothelial inflammatory signaling. Importantly, inflammatory factors including fibronectin3–5 and other aspects of matrix remodeling increase the infiltration and the retention of ApoB-containing lipoprotein, which are known to be the primary triggering events during atherogenesis6. The transition between athero-resistant and athero-prone endothelium thus involves a constellation of interacting lipid accumulation, inflammation and biomechanical factors.

Previous studies have demonstrated that endothelial Caveolin-1 (Cav1), a membrane protein essential for the formation of caveolae, is critical in atherosclerosis. Deletion of Cav1 in mice results in impaired cholesterol homeostasis, insulin resistance, elevated nitric oxide (NO) production, and defects in cardiopulmonary and vascular function7–9. However, the genetic deletion of Cav1 in the Apoe−/− mice strongly protects against atherosclerotic lesions, despite an elevated hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglycemia. Atheroprotection is endothelial-specific, as re-expression of Cav1 in the endothelium fully recovers atherosclerosis in global Apoe−/−Cav1−/− mice8, 10. Increased production of NO due to de-regulation of eNOS appeared to be the likeliest mechanism for this effect, however, reduced LDL infiltration into the artery wall, reduced expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules and decreased monocyte accumulation in the vessel wall might also contribute to atheroprotection in mice lacking Cav1. However, the exact mechanism by which Cav1 promotes atherosclerosis has not been thoroughly investigated.

Here, we demonstrate that the genetic ablation of eNOS does not influence the extent of atheroprotection observed in Cav1 deficient mice. Instead, Cav1 controls pro-atherogenic responses of endothelial cells to disturbed blood flow, including lipid trafficking, ECM remodeling and inflammatory signaling. In this sense, we show that Cav1 impairs LDL infiltration and endothelial inflammation in athero-susceptible areas of the aortic arch. These effects are mirrored by altered distribution of caveolae in athero-prone regions of arteries in vivo. Notably, we also found that loss of Cav-1 in ECs attenuates fibronectin (FN) accumulation and EC inflammation in atheroprone areas. These effects are observed also in normolipemic mid-aged (6–9 months) WT mice, suggesting that EC deficiency of Cav-1 attenuates vascular inflammation independently of the reduction in LDL transport and retention. Moreover, the significant reduction in FN deposition observed in Cav-1 null mice indicates that absence of Cav-1 will also prevent lipoprotein retention in areas susceptible to atherosclerosis. Overall, these results identify a critical role of Cav1 in atherosclerosis that links shear stress, metabolism and inflammation.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Animal Procedures

Cav1−/−, eNOS−/− and Ldlr−/− mice were obtained from Jackson. Cav1−/−Ldlr−/−, Cav1−/−eNOS−/− and Cav1−/−eNOS−/−Ldlr−/− (TKO) were obtained by breeding Cav1−/−, eNOS−/− and Ldlr−/− mice, all of them on C57BL/6 genetic background. Atherosclerosis was induced by feeding the mice a Western-type diet (WD; #D12108; ResearchDiets, Inc.; New Brunswick, NJ) for 12 weeks. Mice used in all experiments were sex and age matched, kept in individually ventilated cages in pathogen-free. The Institutional Animal Care Use Committee of Yale University approved all the experiments. For some experiments using Pcsk9 adeno-associated virus (AAV8-Pcsk9), AAV8-Pcsk9 was injected i.p (1.0×1011VC) to wild type (WT), Cav1−/−, and Cav1Rec (Cav1−/−CavECTG) mice to promote the degradation of LDLR and increase circulating cholesterol levels. Endothelial specific Cav1 transgenic mice (Cav1ECTG) carrying canine Cav1 transgene under the preproendothelin-1 promoter were backcrossed six generations with F6 generation Cav1−/− mice, as reported previously11. All of the experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee of Yale University School of Medicine.

Human coronary arteries

Primary epicardial arteries were procured from explanted hearts of organ donors and processed within the operating room with minimal ischemic times (<15 min). The subjects had varying degrees of coronary atherosclerosis and artery segments were classified as healthy or diseased by an experienced cardiac surgeon. The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Yale University and the New England Organ Bank.

TIRF-based transcytosis of DiI-LDL

LDL transcytosis by confluent primary human coronary artery endothelial cells was measured by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Briefly, confluent HCAECs seeded on 18 mm coverslips were placed in a cell chamber and treated with 40 μg/ml 1 DiI-LDL and 5 ml NucBlue in cold RPMI 1640 media with HEPES at 4°C for 10 min to allow the DiI-LDL to bind to the apical cell membrane without internalization. Cells were rinsed three times with PBS to wash away unbound DiI-LDL followed by the addition of 500 ml warm RPMI. The chamber was placed on a 37°C live cell imaging stage for 2 min before imaging. TIRF images were acquired on an Olympus Cell TIRF Motorized module mounted on an Olympus IX81 microscope using a 150 objective and 561 nm excitation laser and a penetration depth of B110 nm. In siRNA experiments, the 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole epifluorescent channel was used to randomly select cells for imaging; 15 TIRF videos were taken per condition.

Quantification of LDL transcytosis was performed and has been previously described in detail12. Briefly, a MATLAB algorithm (written by Bryan Heit, Western University, Canada) was used to track individual LDL-containing vesicles as they enter the TIRF field. Vesicles are filtered based on size, circularity and fluorescent intensity above background; vesicles undergoing fusion with the basal membrane are identified by a sudden decrease in fluorescent intensity over two consecutive frames, greater than 2.5 s.d. than the rate of fluorescence decrease of the vesicle over the entire period that the vesicle has been tracked. Confounding by endocytic traffic is excluded by requiring vesicles to be stationary before fusion (that is, docking with the membrane). In control HCAECs, 20–40 exocytosis events are typically captured in 150 frames taken at 6.67 frames per second.

Statistical Analysis

Animal sample size for each study was chosen based on literature documentation of similar well-characterized experiments. The number of animals used in each study is listed in the figure legends. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were used and studies were not blinded to investigators or formally randomized. In vitro experiments were routinely repeated at least three times unless otherwise noted. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Statistical differences were measured using an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Normality was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney) was used when data did not pass the normality test. A value of p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Software Version 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

eNOS deregulation does not mediate atheroprotection by Cav1/caveolae deletion

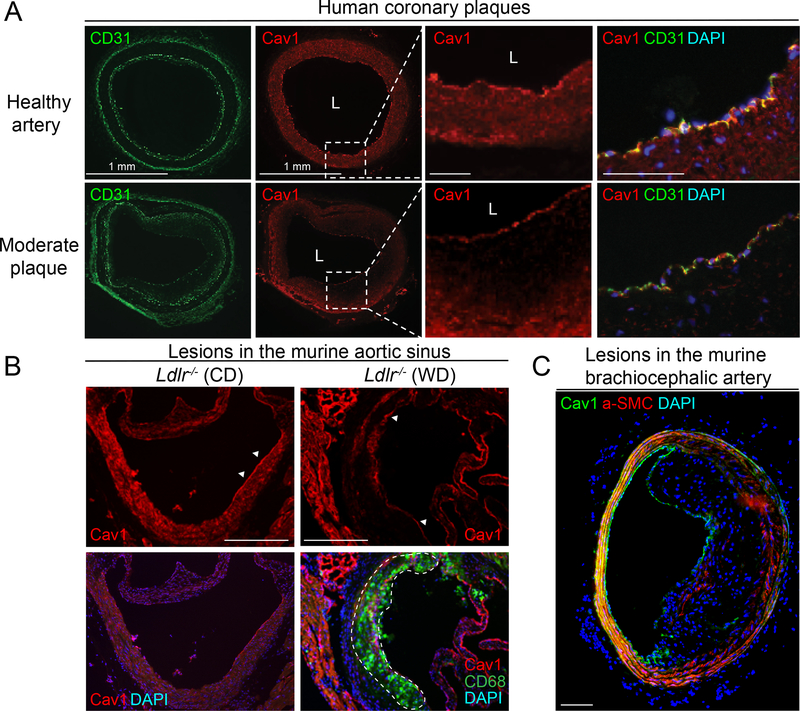

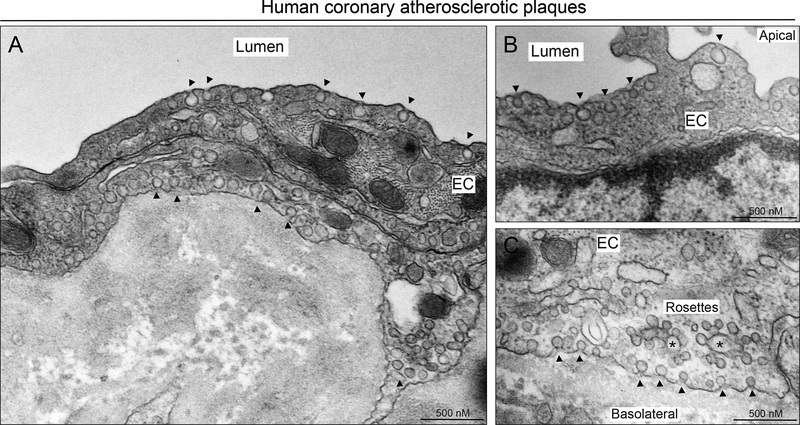

Cav1 is expressed in ECs from human coronary arteries and mouse aortic sinus and brachiocephalic artery (Figure 1). Interestingly, while Cav1 is highly expressed in the endothelium of heathy and atherosclerotic arteries, its expression in VSMC is significantly attenuated in atherosclerotic lesions compared to healthy arteries (Figure 1A). Similarly, Cav1 expression is lost in VSMCs in the media of the mouse aortic sinus (Figure 1B) and brachiocephalic artery (Figure 1C) where the plaque is developed. We further assessed whether the high expression of Cav1 found in EC of human atherosclerotic plaques results in caveolae formation. Thus, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in atherosclerotic lesions isolated from human coronary arteries. The results shown a significant abundance of caveolae in ECs covering the plaques (Figure 2). Interestingly, we observed numerous caveolae structures located in the apical (Figure 2A and 2B) and basolateral site (Figure 2A and 2C) of the endothelium. Additionally, we found intracellular vesicles and other structures known as “caveolae rosettes” in ECs (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Cav1 is highly expressed in the endothelium of human and mouse atherosclerotic plaques.

(A) Representative immunofluorescence analysis of Cav1 and CD31 expression of human coronary arteries. (B-C) Representative immunofluorescence analysis of Cav1, CD68 and a-SMC in mouse aortic sinus (B) and brachiocephalic artery (C). Dashed lines indicate a field that is magnified in the right panel (A) and the atherosclerotic lesion in the aortic sinus (B). White arrows in panel B indicate the expression of Cav-1 in the endothelium of healthy mouse aortic sinus (left panel) and atherosclerotic plaque in the same area (right panel). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 2. Caveolae morphology and localization in the endothelium of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries.

Representative EM image showing different caveolae localization at apical (A, B), intracellular (A) and basolateral side (A, C) of arterial ECs. Arrows indicate classical caveolae localized in apical and basolateral sites of ECs. Stars indicate intracellular fusion of caveolae known as “caveolae rosettes”.

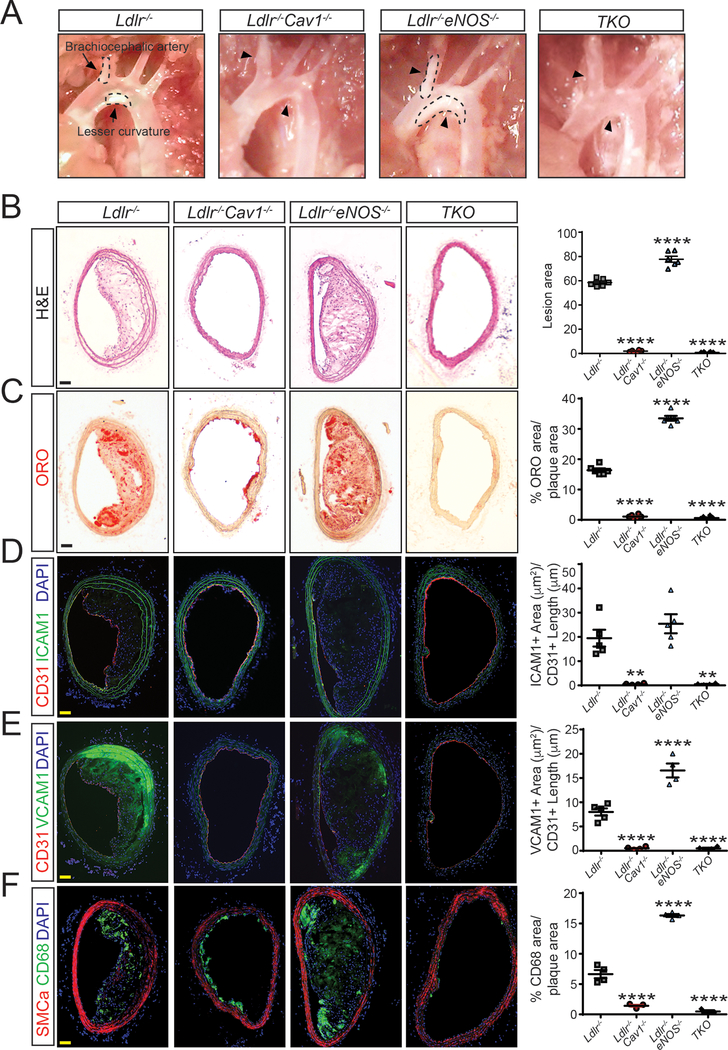

Our previous findings demonstrate that Cav1 expression in ECs regulates the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis.8 Amongst the possible mechanisms by which the deletion of Cav1 would promote atheroprotection, removal of the inhibitory brake of Cav1 on eNOS13, 14 seems most likely given the well-known anti-atherogenic role of NO in regulation of vascular tone, leukocyte activation and thrombosis in vivo15, 16. Therefore, we generated a triple knockout mouse, lacking expression of eNOS, Cav1 and Ldl receptors [Ldlr−/−Cav1−/−eNOS−/− (TKO)]. When analyzed after 12 weeks on a Western-type diet (WD), atherosclerotic plaques were larger in arteries from Ldlr−/−eNOS−/− mice, however, deletion of Cav1 dramatically and equivalently reduced plaque formation in the innominate artery (Figure 3A and B) and in the aortic root (Supplemental Figure 1) with or without eNOS expression, indicating that enhanced eNOS activity is not the major mechanism by which Cav1 deficient mice are athero-resistant.

Figure 3. eNOS deficiency does not influence the atheroprotection observed in mice lacking Cav1 expression.

(A) Representative light microscope pictures of the aortic arches from Ldlr−/−, Ldlr−/−Cav1−/−, Ldlr−/−eNOS−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/−eNOS−/− (TKO) mice fed a WD for 12 weeks. Arrows and dashed lines indicate the atherosclerotic plaques in the brachiocephalic artery and lesser curvature of the aortic arch. (B-F) Representative histological analysis of brachiocephalic arteries isolated from Ldlr−/−, Ldlr−/−Cav1−/−, Ldlr−/−eNOS−/− and TKO mice fed a WD for 12 weeks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (B; H&E), Oil red O (C; ORO), CD31 and ICAM1 (D), CD31 and VCAM1 (E) and SMCα and CD68 (F). Quantification is shown in the right panels and represents the mean ± SEM (n=8 per group). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. ** P<0.01 and **** P<0.0001 versus Ldlr−/− mice. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Lesions were further characterized for neutral lipid deposition and inflammation. Cav1 deletion impaired lipid accumulation (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure 1A), EC activation (Figure 3D and 3E and Supplemental Figure 1B and 1C) and macrophage infiltration (Figure 3F and Supplemental Figure 1D) in the brachiocephalic artery and in the aortic root of Ldlr−/− mice. Moreover, aortic digestion and flow cytometry analysis revealed a significant reduction in macrophages and pro-inflammatory monocytes in aortas from Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice compared to Ldlr−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 2A). The marked reduction of monocyte infiltration in the artery wall observed in Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice was not associated with the number of circulating monocytes, which were elevated in Cav1 deficient mice (Supplemental Figure 2B and 2C). Genetic ablation of Cav1 in Ldlr−/−eNOS−/− mice also completely abolished lipid infiltration and vascular inflammation (Figure 3C–E and Supplemental Figure 1). By contrast, Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− and TKO mice exhibited more severe hyperlipidemia and a modest reduction in body weight (Supplemental Figure 3). Interestingly, body weight (Supplemental Figure 3A), plasma cholesterol (Supplemental Figure 3B) and triglycerides (Supplemental Figure 3C) levels, and lipoprotein profiles (Supplemental Figure 3D and 3E) did not differ between Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice and TKO mice during the progression of atherosclerosis. Thus, effects of Cav1 on plasma lipids cannot account for reduced atherosclerosis in Cav1−/− mice. Collectively, these data identify a major eNOS-independent mechanism by which Cav1 promotes atherosclerosis.

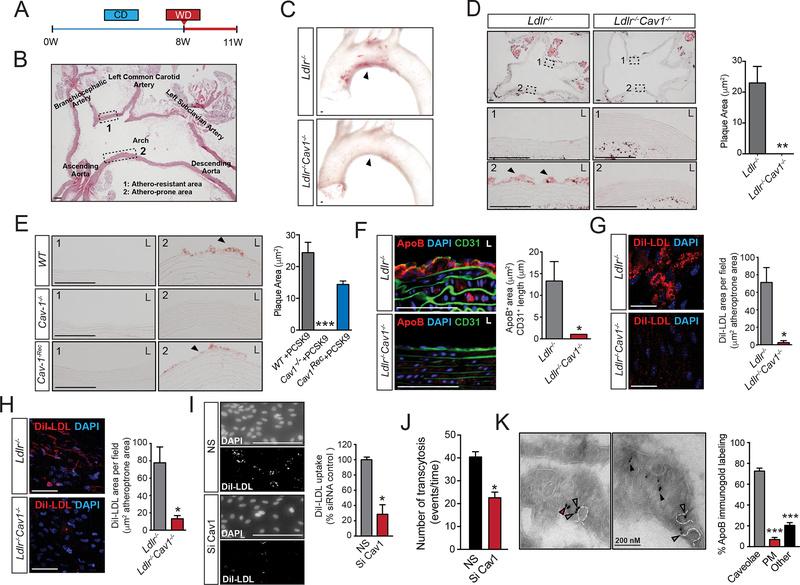

Cav1/caveolae controls LDL infiltration and lipid accumulation in early atherosclerosis

Our previous studies suggested that Cav1/caveolae may affect LDL transport across the endothelium8, 17, 18. Therefore, we assessed LDL infiltration, EC activation and macrophage recruitment in early stages of the disease in Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice. Instead to use Apoe−/− mice as previous studies8, 10, we performed the experiments in Ldlr−/− mice, which start to develop atherosclerotic lesion when they are switched to a Western-type diet (WD). This model allowed us to study the initial events of atherosclerosis and how Cav1 influences atherogenesis in healthy vessels. Briefly, Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice on a chow diet (CD) were switched to a WD for 3 weeks and then examined (Figure 4A). Atherosclerotic plaques initiate in regions of the aorta exhibiting disturbed shear patterns (Figure 4B, area 2 reflecting the lesser curvature of the aortic arch), whereas laminar shear stress (LSS) is known to be atheroprotective (Figure 4B, area 1 reflecting the greater curvature of the aortic arch). Cross sections of the aortic arch were assessed for early lipid infiltration. Notably, absence of Cav1 completely abolished the lesions in the athero-prone region of the aortic arch, a site of preferential lipid infiltration (Figure 4C). Indeed, detailed analysis of Oil-red O (ORO) stained sections showed markedly reduced lipid infiltration in athero-prone areas in the Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice compared with Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 4D). To address cell-type specificity, we next examined Cav1Rec mice that express Cav1 exclusively in the endothelium (Supplemental Figure 4)11. Injection with Pcsk9 adeno-associated virus (Pcks9-Ad) caused significant degradation of hepatic LDLR and induced hypercholesterolemia as expected (Supplemental Figure 5). After 4 weeks on WD, WT-Pcks9-Ad control mice showed substantial lipid infiltration in the athero-prone aortic arch which was completely absent in Cav1−/−-Pcks9-Ad mice (Figure 4E). Importantly, reintroduction of Cav1 in the endothelium restored lipid infiltration to the same extent as control mice (Figure 4E). Lipid staining was negligible in the athero-protective area of all mice (Figure 4D and 4E).

Figure 4. Cav1/caveolae regulate endothelial LDL transport during early stages of atherogenesis.

(A) Experimental protocol used for assessment of early atherosclerosis. (B) Representative image of the cross-sectional analysis of the aortic arch showing the athero-resistant area (#1, greater curvature) and the athero-prone region (#2, lesser curvature). (C) Representative images of whole aortic arch showing the accumulation of neutral lipids (ORO staining) in the athero-resistant and athero-prone areas of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice fed a WD for 3 weeks. (D) Representative images of the cross-sectional analysis of the aortic arch showing the accumulation of neutral lipids (ORO staining) in the athero-resistant (1) and athero-prone areas (2) of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice fed a WD for 3 weeks. L, lumen. Quantification is shown in the right panel and represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.0051) of 3 mice per group. (E) Representative images showing the accumulation of neutral lipids (ORO staining) in the athero-resistant (1) and athero-prone areas (2) of 2 months old WT, Cav1 and CavRec mice injected with Pcks9-Ad and fed a WD for 3 weeks. L, lumen. Quantification is shown in the right panel and represents the mean ± SEM of 3 mice per group. (F) Representative immunostaining analysis of ApoB and CD31 in the lesser curvature of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice fed a WD for 3 weeks (n=4). Quantification is shown in the right panel and represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.0234). (G) Representative en face immunofluorescence analysis of DiI-LDL infiltration in the athero-prone areas of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice i.v. injected with DiI-LDL (300 μg cholesterol) for 30 min. The data are quantified as fluorescence positive area versus total area and represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.016) of 3 mice and 3 fields per mouse. (H) Representative en face immunofluorescence analysis of DiI-LDL infiltration in the lesser curvature of the aortic arch of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice pre-treated with cyclodextrin (5 mM) for 2 h and incubated with DiI-LDL for 30 min. The data are quantified as fluorescence positive area versus total area and represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.01) of 4 mice and 3 fields per mouse. (I) Representative images of HUVECs transfected with non-silencing siRNA (NS) or Cav1 siRNA (Si Cav1) exposed to oscillatory flow and incubated with DiI-LDL (30 μg cholesterol/ml) for 1 h. Quantification is shown in the right panel and represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.028). (J) TIRF–based transcytosis assay showing the number of transcytotic events in HCAECs transfected with non-silencing siRNA, Cav1 siRNA and ATG5 siRNA as indicated, treated with Pcsk9 to eliminate the expression of LDLR and incubated with DiI-LDL. Data represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.039). (K) Representative immuno-electron microscopy images of ApoB in ECs form the lesser curvature of 2 months old Ldlr−/− mice. Quantification of % of ApoB staining in caveolae versus plasma membrane and other intracellular localizations is shown in the right panel and represents the mean ± SEM of 3 mice (average of 15 images per mice). Data presented in D, F, G, H, I and J were analyzed by an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. Data in E and K were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Previous studies established that endothelial caveolae transport macromolecules such as albumin and lipoproteins through the endothelium8, 17, 18. To explore the role of Cav1 in vascular permeability in arteries, we measured in vivo vascular permeability by injecting intravenous (i.v.) Evans blue (EB) and FITC-Albumin into Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice. Our results show that Cav1 deficiency significantly impaired vascular endothelial permeability in vivo, primarily in athero-prone sites of the aortic arch (Supplemental Figure 6A). These results were confirmed by measuring FITC-albumin accumulation in the whole aorta isolated from Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 6B). Given that LDL infiltration into the artery wall is a well-established causative feature during early stages of atherosclerosis, we next stained for ApoB in sections from the athero-prone areas of the aortic arch, to assess early LDL infiltration. ApoB staining was decreased by about 80% in Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− compared to Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 4F). We next injected mice with fluorescently labelled LDL (DiI-LDL) to assess the earliest events. En face analysis of athero-prone areas of the aortic arch showed dramatic reduction of LDL infiltration in the absence of Cav1 (Figure 4G). Consistent with these results, ex vivo treatment of the athero-prone aortic arch from Ldlr−/− mice with the cholesterol chelator, cyclodextrin, a well-known disruptor of lipid rafts and caveolae, impaired LDL infiltration (Figure 4H). These results indicate that Cav1/caveolae regulate the entry of LDL into the vessel wall and vascular permeability, which occurs in areas of disturbed flow. To explore this possibility in vitro we measured DiI-LDL-uptake in HUVECs subject to oscillatory shear stress (OSS) for 16 h. Transfection with siRNA against Cav1 strongly reduced DiI-LDL uptake in HUVEC exposed to OSS (Figure 4I). Thus, in this simplified system where OSS is the only stimulus, Cav1 promotes the endothelial transport of LDL lipoproteins. To further confirm that Cav1 influences LDL transcytosis, we directly assessed transcytotic events using total internal reflectance microscopy (TIRF) to analyze docking, fusion and transcytosis of LDL in human coronary arterial endothelial cells (HCAEC). As expected by the significant reduction in LDL uptake observed in Cav1 deficient ECs, silencing Cav1 in HCAEC markedly attenuated LDL transcytosis in vitro (Figure 4J). Finally, electron microscopy analysis of the endothelium in the athero-prone area of the aortic arch of Ldlr−/− mice showed the presence of ApoB-containing lipoproteins predominantly in caveolae-like vesicles (Figure 4K). Taken together, these results point out the specific role of Cav1/Caveolae in lipid transport and vascular permeability in vivo underlying atherogenesis.

Caveolae deficiency increases flow velocity in athero-prone and athero-resistant regions of the aortic arch in mice

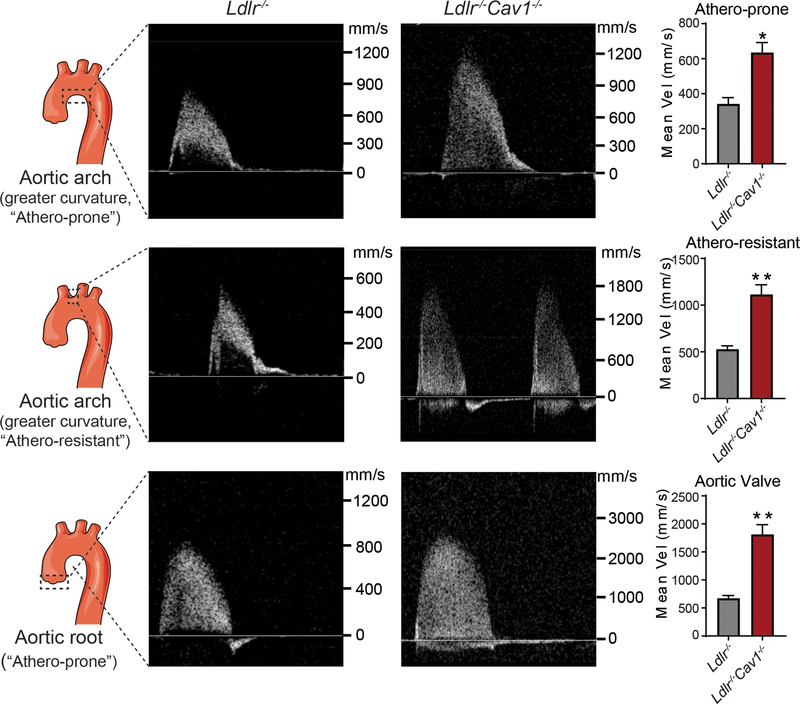

GWAS have established strong associations of variants near CAV1 gene with electrophysiological (ECG) measures/cardiac-conduction abnormalities.19–21 Similarly, Cav-1 deficient mice develop cardiac hypertrophy and pulmonary hypertension.11, 22 Since these cardiac abnormalities might influence flow dynamics in the aorta that could affect lipoprotein transport and retention in the artery wall, we assessed cardiac function and blood flow dynamics at the athero-prone and athero-resistant sites of aorta and aortic valves in 2-months-old Ldlr−/− and Cav1−/−Ldlr−/− mice by serial echo. The results showed that loss of Cav1 does not affect the cardiac function, but leads to cardiac hypertrophy (Table S1), which is consistent with previous reports in mice and human patients.11, 22 In comparison with Ldlr−/− mice, we observed an increase in flow velocity in both “athero-prone” and “athero-resistant” sites of aorta in Cav1−/−Ldlr−/− mice compared to Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 5 and Table S2). The increased flow velocity was also confirmed in the aortic valve of Cav1−/−Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 5 and Table S2).

Figure 5. Flow velocity analysis of athero-prone and athero-resistant sites of aortic arch and valve in Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice.

Age-matched (two months old) male mice were used to assess the blood flow dynamics at the “athero-prone” and “athero-resistant” sites of aorta and aortic valves in Ldlr−/− and Cav1−/−Ldlr−/− mice by serial echo. Quantification of mean velocity is shown in the right panels and represents the mean ± SEM (n=3 per group, P=0.0122 for athero-prone, p=0.0059 for athero-resistant and p=0.0034 for aortic valve). Data were analyzed by an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01 compared to Ldlr−/− group.

Cav1/caveolae promotes fibronectin deposition and inflammation in athero-prone areas of the aorta

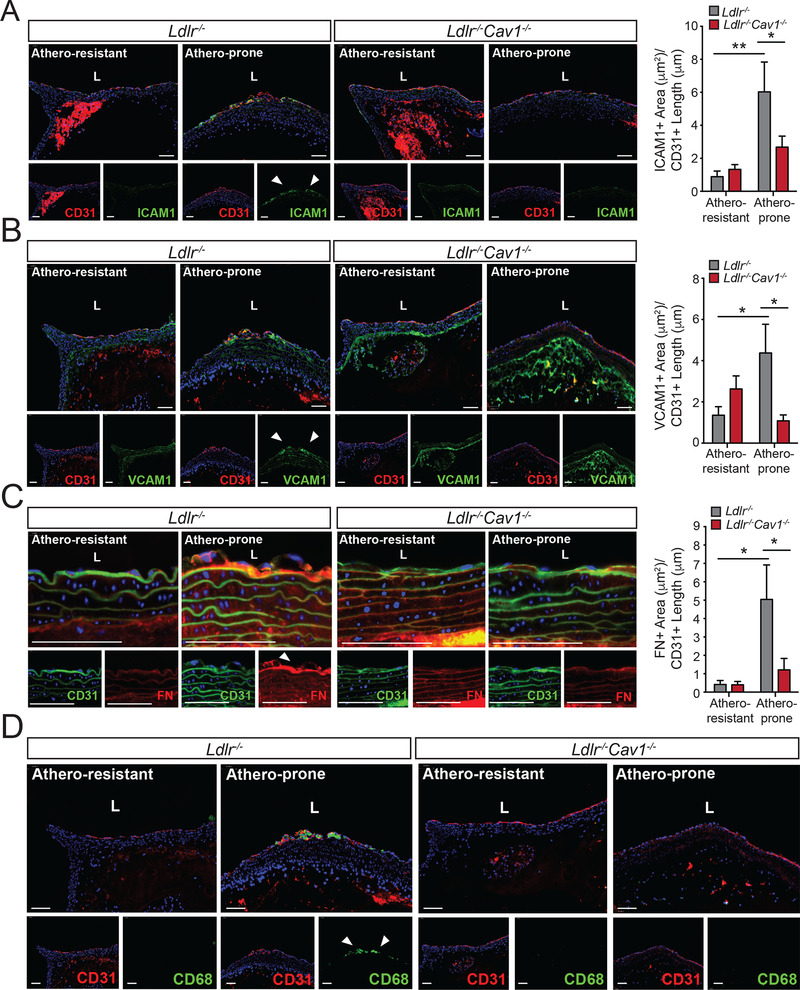

Previous reports have shown that the diminished atherosclerosis observed in mice lacking Cav1 correlated with reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the whole aorta8. To assess whether inflammation of vascular endothelium is a major mechanism mediates these effects, we assayed endothelial ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression during early atherosclerosis. Analysis of Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice revealed a significant reduction in both adhesion molecules in athero-prone regions of the aorta in mice lacking Cav1 (Figure 6A and B). Extracellular matrix remodeling, including fibronectin (FN) expression and deposition, occurs at and enhances inflammatory signaling within preferred sites of atherosclerosis2. Importantly, staining for FN revealed that Cav1/caveolae deletion significantly reduced FN deposition which occurred in aortic athero-prone areas (Figure 6C). The decrease in FN deposition observed in the arteries isolated from Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice compared to Ldlr−/− mice was independent of circulating FN levels, which was similar in both groups of mice (Supplemental Figure 7A). These effects correlated with reduced infiltration of macrophages in the aorta of Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice (Figure 6D). Re-introduction of Cav1 into ECs fully rescued the accumulation of FN (Supplemental Figure 7B), VCAM1 and ICAM1 expression (Supplemental Figure 7C and D) and macrophage infiltration in the aorta (Supplemental Figure 7E), further demonstrating endothelial specificity.

Figure 6. Absence of Cav1 attenuates vascular inflammation and macrophage infiltration in athero-prone regions of the aortic arch.

(A-C) Representative immunofluorescence analysis of athero-prone and athero-resistant areas from of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice stained with ICAM1 and CD31 (A), VCAM1 and CD31 (B) and FN and CD31 (C). Quantifications are shown in right panels and represent the mean ± SEM (n=5–7 mice per group) of ICAM1, VCAM1 and FN positive area normalize per CD31+ length. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of CD68 staining in the athero-prone areas of 2 months old Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice fed a WD for 3 weeks. Data presented in A, B and C were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. Scale bar: 100 μm.

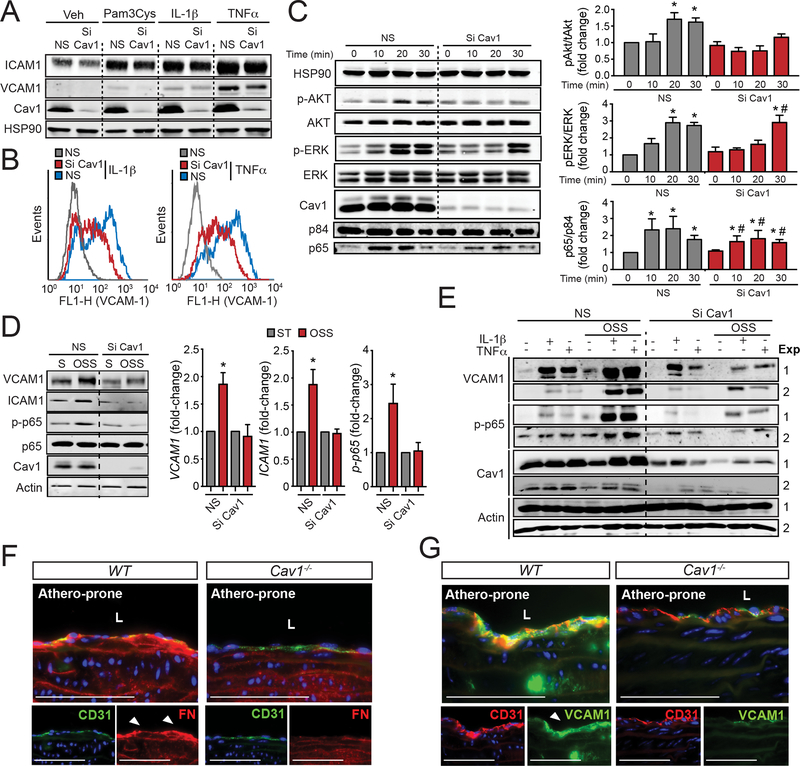

We next assessed whether Cav1/caveolae influence EC activation in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) in response to TLR stimulation and pro-inflammatory cytokines. To this end, HAECs transfected with non-targeting siRNA control (NS) or Cav1 siRNA (Si Cav1) were treated with Pam3Cys, a TLR ligand, IL-1β or TNFα. The results shown that Cav1 knockdown attenuates ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression in EC treated with Pam3Cys, IL-1β and TNFα (Figure 7A and B). In agreement with these observations, AKT and ERK phosphorylation were also reduced in Cav1 deficient ECs in response to IL-1β (Figure 7C, quantified in right panels) and TNFα (data not shown). Similarly, NFkB activation assayed by p65 nuclear translocation was significantly reduced after Cav1 knockdown (Figure 7C, quantified in right panels).

Figure 7. Loss of Cav1 impairs cytokine and oscillatory shear stress- induced EC inflammation.

(A) Representative Western Blot analysis of ICAM1, VCAM1 and Cav1 expression in HAECs transfected with non-silencing siRNA (NS) or Cav1 siRNA (Si Cav1) and treated with Pam3Cys (TLR2 ligand, 10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL) and TNFα (10 ng/mL) for 8 h. HSP90 was used as a loading control. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of VCAM1 and ICAM1 membrane expression in HAECs transfected with NS or Si Cav1 and treated with, IL-1β (10 ng/mL, left panel) and TNFα (10 ng/mL, right panel) for 8 h. (C) Time course analysis of p-AKT (Ser473), AKT, p-ERK, ERK, Cav1 and HSP90 (loading control) expression in HAECs transfected with NS or Si Cav1 and treated with, IL-1β (10 ng/mL, left panel) for 0, 10, 20 and 30 min. Nuclear translocation of p65 is shown in the bottom panel. P84 was used as a nuclear marker. Right panels show the quantification (mean ± SEM of n=3 independent experiments). (D) Representative Western Blot analysis of VCAM1, ICAM1, p-p65, p65, Cav1 and actin in HUVECs transfected with NS or Si Cav1 in static (S) or exposed to oscillatory shear stress (OSS; 1±3 dyne/cm2) for 24 h. Graphs in the right show quantification analysis and data represents mean ± SEM of n=3 independent experiments. (E) Representative Western Blots analysis of VCAM1, p-p65, Cav1 and actin in HUVECs transfected with non-silencing siRNA or Cav1 siRNA exposed or not to OSS for 24 h and treated with IL-1β (12,5 pg/mL) and TNFα (0.12 ng/mL) for 8 h. (F and G) Representative immunofluorescence images of FN and CD31 (F) and VCAM1 and CD31 (G) in the lesser curvature of 6 months old WT mice. Data presented in C and D were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. * indicates P < 0.05 compared with NS at time 0 or static conditions, and # indicates P < 0.05 compared to Si Cav1 at time 0. Scale bar: 100 μm.

We next examined responses to OSS as a model of disturbed flow which mimics athero-prone conditions in the aorta. Our results showed that ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression and p65 phosphorylation that were induced by OSS, were strongly attenuated by Cav1 silencing (Figure 7D, quantified in right panels). OSS sensitization of ECs to inflammatory cytokines, so-called inflammatory priming, is thought to be a major mechanism promoting atherogenesis23. While Cav1 knockdown moderately reduced direct EC responses to IL-1β and TNFα, it completely inhibited the synergy between OSS and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Figure 7E). Next, to determine the specific contribution of Cav1 in regulating inflammation by OSS in vivo in absence of hyperlipidemia, we assessed FN accumulation and VCAM1 expression in 6-month old WT and Cav1−/− mice. The accumulation of FN (Figure 7F) and VCAM1 expression (Figure 7G in athero-prone regions of WT mice were markedly reduced in absence of Cav1. These results demonstrate that Cav1 influences endothelial inflammatory activation in general, but most critically in atheroprone regions of the vessel wall.

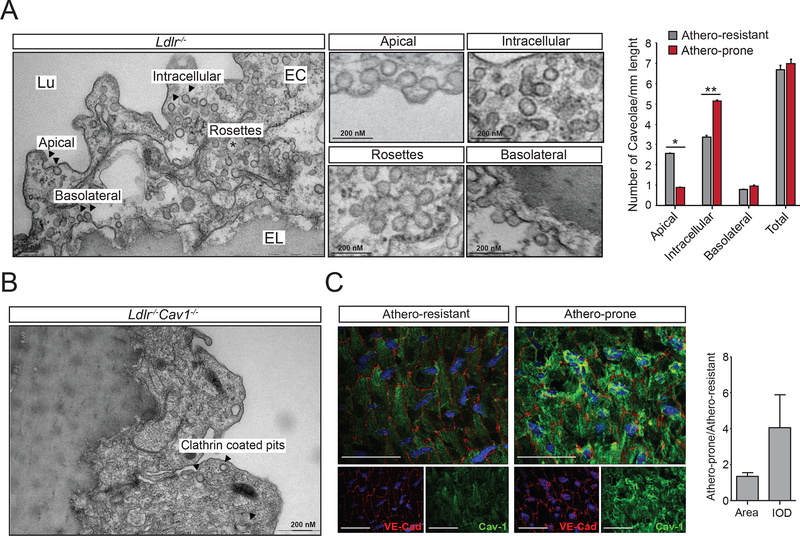

Cav1 levels and caveolae morphology are altered in athero-prone regions of the aortic arch

Finally, we investigated whether caveolae morphology and expression is altered in pro-atherogenic regions of the artery wall. To this end, we analyzed morphologically defined caveolae by TEM, assessing images of complete perimeters of multiple ECs from two different areas of the aortic arch. Interestingly, ECs in the lower curvature or athero-prone sites showed fewer apical caveolae than in the upper curvature or athero-resistant area, whereas intracellular vesicles (caveolae) were significantly more abundant in ECs in the lower compared to the upper curvature (Figure 8A, quantified in right panel). Basolateral and rosette structures appeared unchanged. Neither apical, basolateral and internal vesicles were detected in ECs from Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− (Figure 8B). Additionally, en face examination of Cav1 expression in the aortic arch showed higher Cav1 levels in athero-prone areas compared to athero-protected regions (Figure 8C, quantified in right panel). These relevant observations suggest that changes in Cav1 expression and/or caveolae cellular distribution might explain why specific areas of the aorta subjected to disturb flow and different mechanical tension are more susceptible to develop atherosclerotic lesions.

Figure 8. Shear stress and mechanical forces influence caveolae morphology in athero-prone and athero-resistant areas of the aortic arch.

(A) Representative EM image of aortic EC showing different caveolae localization (apical, intracellular, rosettes and basolateral). Magnified images are shown in the middle panels. Quantification of caveolae in endothelial cells from the athero-resistant and athero-prone areas of the aortic arch in Ldlr−/− mice (n=3) as number of morphologically defined caveolae per micrometer of endothelial plasma membrane length (average of 20 images per mice). Data represents the mean ± SEM (P=0.0357 for Apical and P=0.0038 for Intracellular). (B) Representative EM image of aortic EC from Ldlr−/−Cav1−/− mice lacking caveolae. Arrows indicate clathrin-coated pits vesicles (c) En face immunostaining of VE-Cad and Cav1 in ECs from the athero-resistant (left panel) and athero-prone (right panel). Graph in the right shows the quantification analysis and represents the relative florescence of Cav1 staining in the athero-prone area versus athero-resistant area (n=3 mice each group of mice and 3 segments per mouse). Data presented in A were analyzed by an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. *P<0.05 and ** indicates P<0.01. Scale bar in C: 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

The major conclusion of this study is that Cav1 deletion suppresses atherosclerosis likely by attenuating LDL transcytosis, FN deposition and vascular inflammation, but not through increased NO production (Supplemental Figure 8). This result was unexpected since previous studies pointed to increase NO production as the major mechanism by which Cav1 deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis13, 24. Although previous studies showed that Cav1 is involved in lipid transport and homeostasis, whether Cav1 determines endothelial susceptibility to lipid accumulation in specific aortic regions exposed to disturbed blood flow during early stages of atherosclerosis has received less attention. To determine how Cav1 controls lipoprotein influx and retention in the artery wall, we assessed LDL transport and retention, EC activation and monocyte/macrophage accumulation at the initial steps of atherosclerosis. Our results show that LDL accumulation is prominent in athero-prone areas (lesser curvature of aortic arch), and that these lesions are completely abolished in the Cav1 deficient mice. Moreover, loss of Cav1 significantly reduces sub-endothelial staining of ApoB in the athero-prone regions of the aortic arch. Of note, our EM studies also demonstrate that caveolae in aortic ECs transport ApoB-containing lipoproteins. In agreement with these findings, transport of fluorescence labelled LDL is significantly impaired in Cav1−/− mice.

Previous studies have shown that genetic variations near to CAV1 locus are associated with heart morphology and cardiac-conduction alterations that could have an effect in blood flow dynamics, thus affecting the LDL infiltration in the arterial wall.19–21 Here, we show that absence of Cav1 increases flow velocity in the aortic arch and valve, suggesting that this flow alteration could indeed influence LDL transport and retention in the arterial wall, which might affect the interpretation of our data. However, the relationship between flow velocity and atherogenesis is complex and not fully understood. In this regard, there are a number of studies that have shown that increased flow velocity is associated with increased LDL uptake ex vivo and in vitro.25, 26 Despite the higher velocity found in the athero-prone, athero-resistant regions in the aortic arch and the aortic valve of Cav1 deficient mice, we still observed a significant decrease in LDL infiltration. In addition to the potential confounding effects of altered blood flow dynamics in regulating lipoprotein transport in the artery wall, Cav1−/− mice develop dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and lipodystrophy.27–30 Notwithstanding, absence of Cav1 protects against proatherogenic lipoprotein infiltration during the initiation of atherosclerosis. Moreover, our studies assessing LDL trafficking were performed in 2-months old male mice. At this age, Cav1 deficient mice do not develop obesity, insulin resistance and lipodystrophy,27 ruling out the potential effects of this metabolic abnormalities in aortic lipoprotein transport and the origination of atherosclerotic plaques.

Besides LDL transcytosis, caveolae might also mediate the transport of HDL across the endothelium and regulate the reverse cholesterol transport, a multi-step process resulting in the movement of cholesterol from the artery to the liver.31 While caveolin-regulated HDL trafficking in the artery wall might influence the progression and regression of atherosclerosis, it is unlikely that could play a major role in our study since we found that absence of caveolae in the endothelium attenuates the atherogenesis. Moreover, recent studies have also demonstrated that the SR-BI-regulated HDL transcytosis in microvascular ECs is independent of caveolae. 32 Further studies will be important to define the molecular mechanism that controls the transcytosis of HDL in and out of the arterial wall and whether caveolae regulates this process.

In addition to reduced LDL transport/retention, absence of Cav1 in ECs might attenuate inflammation via at least 3 additional mechanisms: 1) Mislocalization of pro-inflammatory cytokine receptors in lipid rafts/caveolae5, 33; 2) Reducing FN deposition in the aorta and 3) Impairing disturb flow-mediated EC inflammation and inflammatory priming. While the absence of Cav1/caveolae was predicted to attenuate LDL infiltration and TNFα- and IL1β-induced EC activation, the changes in ECM remodeling and flow-mediated EC inflammation were unexpected. Notably, we found that absence of Cav1 in ECs markedly alters subendothelial basement membrane composition, reducing the accumulation of FN. Interestingly, deposition of FN in the intima of the athero-prone regions alters integrin downstream signaling to promote EC inflammatory response and atherosclerosis. Indeed, several studies reported that both genetic and pharmacological strategies to reduce FN in atherosclerotic-prone regions attenuates atherosclerosis3, 34, 35. Altering downstream integrin signaling also inhibits atherosclerosis4. Our data demonstrate that specific re-introduction of Cav1 in EC normalize FN deposition and EC activation to a similar extent observed in WT mice, suggesting that ECM remodeling in the Cav1 deficient mice is mediated by the impact of Cav1/caveolae loss in ECs. The molecular mechanism by which Cav1 expression influences FN deposition in athero-prone regions might be associated to the pro-fibrotic effect TGFβ activation which requires Cav1 for signaling.36 Moreover, Cav1/caveolae have been also shown to regulate FN internalization and degradation and more recently with the secretion of FN via exosome-regulated process.37 Additional studies will be required to define the specific mechanism by which EC Cav1/caveolae controls ECM changes in athero-prone areas during the progression of atherosclerosis but it is likely that a combination of the processes described above might contribute to the alteration in ECM composition observed in Cav1 deficient mice. Moreover, we also found that absence of Cav1 in ECs expose to disturbed flow impairs the activation of NFkB signaling pathway and attenuates the OSS-primed inflammatory response to pro-atherogenic cytokines including TNFα and IL1β. Together, these observations suggest that Cav1 may influence vascular inflammation, independently of its effect in regulating lipoprotein transport across the endothelium during atherogenesis. In agreement to these findings, Lutgens and colleagues demonstrated that absence of Cav1 attenuates the progression of atherosclerosis by hampering leukocyte influx into the artery wall.38

Previous reports in cultured cells have shown the role of caveolae as a mechanism to buffer mechanical stress39, 40. Interestingly, the number of caveolae are remarkably increased in ECs that are cultured under laminar shear stress (LSS) compared with static conditions41–44. Yu and colleagues have shown that Cav1 in EC plays an important role mechanotransduction and remodeling of blood vessels45. Here, we prove by quantitative analysis the existence of significant differences in the pattern of subcellular redistribution of caveolae in the athero-prone versus the athero-protective area of the aortic arch. While the mechanism behind this observation remains unclear, these findings likely suggest that differences in hemodynamics and mechanical forces might influence caveolae morphology in different location of the aortic endothelium. In addition, it has been reported that caveolae and Cav1 move toward the upstream edge of ECs in vitro and are associated with sites of Ca2+ wave initiation42 and conversely, shear stress triggers an increase in caveolae density at the luminal face41, consistent with a relocalization of caveolae and a role for Cav1 in the regulation of the EC in response to altered shear stress. This is particularly interesting in the context of atherogenesis, and describes an intriguing scenario where anatomically determined altered hemodynamics might regulate endothelial caveolae redistribution throughout the aortic endothelium. This unique feature of caveolae localization can impact lipid infiltration and inflammation in the athero-prone regions, thereby promoting atherosclerosis. In summary, our study provides convincing evidences of how Cav1/caveolae controls the progression of atherosclerosis and elucidate novel fundamental mechanism that initiate the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

The atheroprotection observed in mice lacking Caveolin-1 is independent of eNOS activation and NO production.

Endothelial Cav1 controls lipoprotein infiltration and vascular inflammation in early stage atherosclerotic lesions.

Endothelial Cav1 promotes pro-atherogenic matrix deposition leading to endothelial cell activation in athero-prone regions of the aorta.

Athero-prone regions of the aorta are characterized by increased intracellular and basolateral caveolae distribution in ECs compared to athero-resistant areas.

What are the clinical implications?

This study shed light on the pathophysiological role of Cav1 in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases as key regulator that links shear stress, metabolism and inflammation.

Suppression of Cav1 expression in ECs might prevent the progression and promote the regression of atherosclerosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Nathan L. Price for helpful comments and manuscript editing.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35HL135820 to CF-H; R01HL105945 to YS; F32DK10348902 to NP; and R01HL75092 to MAS), the American Heart Association (16EIA27550005 to CF-H; 16GRNT26420047 to YS, 17SDG33110002 to NR, ”James and Donna Dickenson-Sublett Award for the Advancement of Cardiovascular Research”, SDG23000025.” to CMR), the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence in Cardiovascular Research, MicroRNA-based Therapeutic Strategies in Vascular Disease (to CF-H and WCS), Plan Estatal de Investigación y Técnica y de Innovación 2013–2016, Spain (SAF2015–70747-R to MAL) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (G-16–00013521) and a Canada Research Chair (both to WLL).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glass CK and Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feaver RE, Gelfand BD, Wang C, Schwartz MA and Blackman BR. Atheroprone hemodynamics regulate fibronectin deposition to create positive feedback that sustains endothelial inflammation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1703–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orr AW, Sanders JM, Bevard M, Coleman E, Sarembock IJ and Schwartz MA. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yun S, Budatha M, Dahlman JE, Coon BG, Cameron RT, Langer R, Anderson DG, Baillie G and Schwartz MA. Interaction between integrin alpha5 and PDE4D regulates endothelial inflammatory signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1043–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurdagul A Jr, Green J, Albert P, McInnis MC, Mazar AP and Orr AW. alpha5beta1 integrin signaling mediates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced inflammation and early atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1362–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr AW, Hahn C, Blackman BR and Schwartz MA. p21-activated kinase signaling regulates oxidant-dependent NF-kappa B activation by flow. Circ Res. 2008;103:671–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen AW, Razani B, Wang XB, Combs TP, Williams TM, Scherer PE and Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1-deficient mice show insulin resistance and defective insulin receptor protein expression in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C222–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, Suarez Y, Rahner C, Davalos A, Lasuncion MA and Sessa WC. Genetic evidence supporting a critical role of endothelial caveolin-1 during the progression of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank PG, Cheung MW, Pavlides S, Llaverias G, Park DS and Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 and regulation of cellular cholesterol homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank PG, Lee H, Park DS, Tandon NN, Scherer PE and Lisanti MP. Genetic ablation of caveolin-1 confers protection against atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata T, Lin MI, Huang Y, Yu J, Bauer PM, Giordano FJ and Sessa WC. Reexpression of caveolin-1 in endothelium rescues the vascular, cardiac, and pulmonary defects in global caveolin-1 knockout mice. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2373–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong SM, Sugiyama MG, Fung KY, Gao Y, Wang C, Levy AS, Azizi P, Roufaiel M, Zhu SN, Neculai D, Yin C, Bolz SS, Seidah NG, Cybulsky MI, Heit B and Lee WL. A novel assay uncovers an unexpected role for SR-BI in LDL transcytosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;108:268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernatchez P, Sharma A, Bauer PM, Marin E and Sessa WC. A noninhibitory mutant of the caveolin-1 scaffolding domain enhances eNOS-derived NO synthesis and vasodilation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3747–3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernatchez PN, Bauer PM, Yu J, Prendergast JS, He P and Sessa WC. Dissecting the molecular control of endothelial NO synthase by caveolin-1 using cell-permeable peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:761–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowles JW, Reddick RL, Jennette JC, Shesely EG, Smithies O and Maeda N. Enhanced atherosclerosis and kidney dysfunction in eNOS(−/−)Apoe(−/−) mice are ameliorated by enalapril treatment. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhlencordt PJ, Gyurko R, Han F, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Aretz TH, Hajjar R, Picard MH and Huang PL. Accelerated atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm formation, and ischemic heart disease in apolipoprotein E/endothelial nitric oxide synthase double-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;104:448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank PG, Pavlides S and Lisanti MP. Caveolae and transcytosis in endothelial cells: role in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schubert W, Frank PG, Razani B, Park DS, Chow CW and Lisanti MP. Caveolae-deficient endothelial cells show defects in the uptake and transport of albumin in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48619–48622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Wang X, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wang D, Tan C, Fa J, Zhang R, Wang F, Xu C, Huang Y, Li S, Yin D, Xiong X, Li X, Chen Q, Tu X, Yang Y, Xia Y, Xu C and Wang QK. Genomic variant in CAV1 increases susceptibility to coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm H, Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Thorleifsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Stefansdottir H, Gudjonsson SA, Jonasdottir A, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Nyrnes A, Wilsgaard T, Hald EM, Hveem K, Stoltenberg C, Lochen ML, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U and Stefansson K. Several common variants modulate heart rate, PR interval and QRS duration. Nat Genet. 2010;42:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Albert CM, Glazer NL, Ritchie MD, Smith AV, Arking DE, Muller-Nurasyid M, Krijthe BP, Lubitz SA, Bis JC, Chung MK, Dorr M, Ozaki K, Roberts JD, Smith JG, Pfeufer A, Sinner MF, Lohman K, Ding J, Smith NL, Smith JD, Rienstra M, Rice KM, Van Wagoner DR, Magnani JW, Wakili R, Clauss S, Rotter JI, Steinbeck G, Launer LJ, Davies RW, Borkovich M, Harris TB, Lin H, Volker U, Volzke H, Milan DJ, Hofman A, Boerwinkle E, Chen LY, Soliman EZ, Voight BF, Li G, Chakravarti A, Kubo M, Tedrow UB, Rose LM, Ridker PM, Conen D, Tsunoda T, Furukawa T, Sotoodehnia N, Xu S, Kamatani N, Levy D, Nakamura Y, Parvez B, Mahida S, Furie KL, Rosand J, Muhammad R, Psaty BM, Meitinger T, Perz S, Wichmann HE, Witteman JC, Kao WH, Kathiresan S, Roden DM, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, McKnight B, Sjogren M, Newman AB, Liu Y, Gollob MH, Melander O, Tanaka T, Stricker BH, Felix SB, Alonso A, Darbar D, Barnard J, Chasman DI, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Gudnason V and Kaab S. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2012;44:670–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao YY, Liu Y, Stan RV, Fan L, Gu Y, Dalton N, Chu PH, Peterson K, Ross J Jr and Chien KR. Defects in caveolin-1 cause dilated cardiomyopathy and pulmonary hypertension in knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11375–11380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Baker BM, Chen CS and Schwartz MA. Endothelial cell sensing of flow direction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2130–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trane AE, Pavlov D, Sharma A, Saqib U, Lau K, van Petegem F, Minshall RD, Roman LJ and Bernatchez PN. Deciphering the binding of caveolin-1 to client protein endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS): scaffolding subdomain identification, interaction modeling, and biological significance. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:13273–13283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warty VS, Calvo WJ, Berceli SA, Pham SM, Durham SJ, Tanksale SK, Klein EC, Herman IM and Borovetz HS. Hemodynamics alter arterial low-density lipoprotein metabolism. J Vasc Surg. 1989;10:392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang H, Fan Y, Sun A and Deng X. Compositional or charge density modification of the endothelial glycocalyx accelerates flow-dependent concentration polarization of low-density lipoproteins. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razani B, Combs TP, Wang XB, Frank PG, Park DS, Russell RG, Li M, Tang B, Jelicks LA, Scherer PE and Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1-deficient mice are lean, resistant to diet-induced obesity, and show hypertriglyceridemia with adipocyte abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8635–8647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briand N, Le Lay S, Sessa WC, Ferre P and Dugail I. Distinct roles of endothelial and adipocyte caveolin-1 in macrophage infiltration and adipose tissue metabolic activity. Diabetes. 2011;60:448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank PG, Pavlides S, Cheung MW, Daumer K and Lisanti MP. Role of caveolin-1 in the regulation of lipoprotein metabolism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, Davalos A, Prendergast J and Sessa WC. Endothelial-specific overexpression of caveolin-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:998–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuchel M and Rader DJ. Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation. 2006;113:2548–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fung KY, Wang C, Nyegaard S, Heit B, Fairn GD and Lee WL. SR-BI Mediated Transcytosis of HDL in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Is Independent of Caveolin, Clathrin, and PDZK1. Front Physiol. 2017;8:841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Alessio A, Al-Lamki RS, Bradley JR and Pober JS. Caveolae participate in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and internalization in a human endothelial cell line. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1273–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohwedder I, Montanez E, Beckmann K, Bengtsson E, Duner P, Nilsson J, Soehnlein O and Fassler R. Plasma fibronectin deficiency impedes atherosclerosis progression and fibrous cap formation. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:564–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan MH, Sun Z, Opitz SL, Schmidt TE, Peters JH and George EL. Deletion of the alternatively spliced fibronectin EIIIA domain in mice reduces atherosclerosis. Blood. 2004;104:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng F, Zhang B, Wu D, Ingram AJ, Gao B and Krepinsky JC. TGFbeta-induced RhoA activation and fibronectin production in mesangial cells require caveolae. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas Albacete-Albacete IN-L, Juan Antonio Lopez, Ines Martin-Padura, Astudillo Alma M., Michael Van-Der-Heyden, Jesus Balsinde, Gertraud Orend, Jesus Vazquez, Miguel Angel del Pozo. ECM deposition is driven by caveolin1-dependent regulation of exosomal biogenesis and cargo sorting. BioRxiv 405506 [Preprint]. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engel D, Beckers L, Wijnands E, Seijkens T, Lievens D, Drechsler M, Gerdes N, Soehnlein O, Daemen MJ, Stan RV, Biessen EA and Lutgens E. Caveolin-1 deficiency decreases atherosclerosis by hampering leukocyte influx into the arterial wall and generating a regulatory T-cell response. FASEB J. 2011;25:3838–3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha B, Koster D, Ruez R, Gonnord P, Bastiani M, Abankwa D, Stan RV, Butler-Browne G, Vedie B, Johannes L, Morone N, Parton RG, Raposo G, Sens P, Lamaze C and Nassoy P. Cells respond to mechanical stress by rapid disassembly of caveolae. Cell. 2011;144:402–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeow I, Howard G, Chadwick J, Mendoza-Topaz C, Hansen CG, Nichols BJ and Shvets E. EHD Proteins Cooperate to Generate Caveolar Clusters and to Maintain Caveolae during Repeated Mechanical Stress. Curr Biol. 2017;27:2951–2962 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyd NL, Park H, Yi H, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Sykes M and Jo H. Chronic shear induces caveolae formation and alters ERK and Akt responses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1113–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isshiki M, Ying YS, Fujita T and Anderson RG. A molecular sensor detects signal transduction from caveolae in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43389–43398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzo V, Morton C, DePaola N, Schnitzer JE and Davies PF. Recruitment of endothelial caveolae into mechanotransduction pathways by flow conditioning in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1720–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun RJ, Muller S, Stoltz JF and Wang X. Shear stress induces caveolin-1 translocation in cultured endothelial cells. Eur Biophys J. 2002;30:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J, Bergaya S, Murata T, Alp IF, Bauer MP, Lin MI, Drab M, Kurzchalia TV, Stan RV and Sessa WC. Direct evidence for the role of caveolin-1 and caveolae in mechanotransduction and remodeling of blood vessels. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1284–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.