Pathophysiology of Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is crucially important neurological emergency with high societal impact of >1 million deaths worldwide each year.1–3 The pathophysiology of intracerebral hemorrhage can be considered to occur in ≤2 conceptual phases. In the first phase, there is immediate cellular injury in the hemorrhage core because of the acute bleed and early hemorrhagic expansion. The final hemorrhagic volume after the period of hemorrhagic expansion and the location are of hemorrhage are strong predictors of outcome.4,5 Prevention of hemorrhagic expansion can be achieved,6 but doing so does not improve outcome. The second conceptual phase of brain hemorrhage is the persistent hematoma phase characterized by progressive damage to perihematomal tissue caused by mass effect, excitotoxic edema, and progressive neurotoxicity resulting from iron, thrombin, blood breakdown products, free radical formation, protease activation and inflammation, and hyperglycolysis.7–12 The evolutionary damage to the perihematomal tissue is complex and involves multiple mechanisms that are presumed to be linked to the presence of the mass of collected blood and progressive edema. Animal models demonstrate that persistence of the hematoma in brain tissue results in progressive brain edema, metabolic distress, and potentially other mechanisms, which result in long-term disability. We hypothesize that in humans, early removal of the hemorrhage from the parenchyma will result in avoidance or mitigation of these secondary insults and result in substantially enhanced neurological recovery.

Surgery for ICH

The effectiveness of craniotomy in the treatment of ICH remains controversial, despite having been evaluated during the past 4 decades. To date, ≤7 randomized trials of surgical intervention have been completed and published in the English language (Table).13–19 Results of individual trials have generally failed to demonstrate improvement in outcome in surgically treated patients.

Table.

Randomized Surgical Trials for Intracerebral Hemorrhage

| Author | Intervention | Year | N, Surgery | N, Medical | Timing, h | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McKissock et al13 | Craniotomy | 1961 | 89 | 91 | 72 | None |

| Juvela et al14 | Craniotomy | 1989 | 26 | 26 | 48 | None |

| Batjer et al15 | Craniotomy | 1990 | 8 | 9 | 24 | None |

| Morgenstern et al16 | Craniotomy | 1998 | 17 | 17 | 12 | None |

| Auer et al17 | Endoscopic | 1989 | 50 | 50 | 48 | Positive |

| Zuccarello et al18 | Crani/Stereo | 1999 | 9 | 11 | 24 | None |

| Mendelow et al19 | Craniotomy | 2005 | 503 | 530 | 24 | Neutral |

Interestingly, the 1 positive trial used a minimally invasive surgical approach. A variety of factors have been addressed that may explain the lack of greater efficacy for invasive surgical evacuation of ICH in prior trials, including late timing of surgery beyond a therapeutic window, inadequately powered sample size, incomplete evacuation, primary damage of the hemorrhage, recurrent bleeding in the immediate postoperative period, persistent intraventricular hemorrhage. However, the type of surgical technique and the damage induced by the operative procedure itself has not been adequately investigated.

The Surgical Trial in Intracererbral Hemorrhage (STICH) trial has offered promise for the effect of limited surgery on the basis of the observation that evacuation of surface hematomas seems to result in improved outcome. However, conventional open evacuation surgery did not improve outcome in the overall STICH cohort. STICH II is a randomized controlled trial of 600 patients that was designed as an open craniotomy trial for lobar hematomas that are based or near the cortex with no intraventricular component. Thus, it tests a form of less invasive craniotomy. STICH II data are expected in the spring of 2013. Many questions were raised by STICH I and II, including whether open surgery creates new traumatic brain injury, if open surgery results in near-complete hematoma evacuation, and whether recurrent bleeding after surgery negates the potential benefits of hematoma volume reduction. Comparison of STICH I and II will provide some of these answers. However, these questions are best answered through the use of minimally invasive surgery performed in a prospective fashion with serial imaging to determine the adequacy of hematoma evacuation, surgical induced injury, and recurrence of bleeding.16

Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery for Hemorrhage Evacuation

Minimally invasive surgery generally refers to the concept of creating minimal trauma to normal appearing tissue during the process of removing the hematoma. This stands in distinction from the open craniotomy in which a large bone flap is created; the brain is exposed, retracted, and manipulated to inspect the site of bleeding and suction blood from multiple areas. Two main types of minimally invasive surgery have been attempted for hematoma removal. The first is endoscopic evacuation of the hematoma. In endoscopic evacuation, a small burr hole is created, and an endoscope measuring from 5 to 8 mm diameter is inserted through normal brain tissue into the hematoma. Suction and irrigation are applied to remove the hematoma. The brain is then visualized via the endoscope to determine the site of bleeding and to determine the amount of ICH evacuated. Auer et al17 reported the first randomized trial of endoscopic-guided hemorrhage evacuation. This trial of 100 patients demonstrated a trend toward decreased morbidity and mortality in the surgical arm, particularly in younger patients with subcortical hematomas. Patients were randomized to stereotactic-guided endoscopic evacuation or medical therapy within 24 hours of symptom onset. The investigators found that, at 6 months, 40% of surgically treated patients had no or minimal disability compared with 25% of patients in the medically treated group (P<0.01). This encouraging predecessor trial using first-generation endoscopic technology without the aid of computed tomography guidance indicates that endoscopic surgical evacuation offers promise as a means to maximize hematoma evacuation while minimizing damage to normal tissue. A preliminary single-center randomized controlled study of frameless stereotactically guided endoscopic evacuation trial was performed, which demonstrated the safety of early hematoma evacuation with resultant reduction in hematoma volume by 80%12 in comparison to a 78% growth in hematoma by 48 hours.

The second main type of minimally invasive surgery for brain hemorrhage is stereotactic aspiration and thrombolysis. This technique involves using image guidance to place a catheter into the main body of the hematoma and aspirate blood. A catheter is left in the body of the hematoma, and during the course of several days, repeated small doses of thrombolytics (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator) are instilled via the catheter into the brain to clear the blood slowly during the course of 72 to 96 hours. Several studies demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.12,16,18,20–26 In these studies, hematoma evacuation seems to occur slowly, and result in reduction in hematoma volume, brain edema, and midline shift. However, these studies have been nonrandomized and questions on safety of thrombolysis, chemical toxicity of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator, and effects on outcome remain at this time.

Randomized Controlled Trials in Minimally Invasive Surgery for ICH

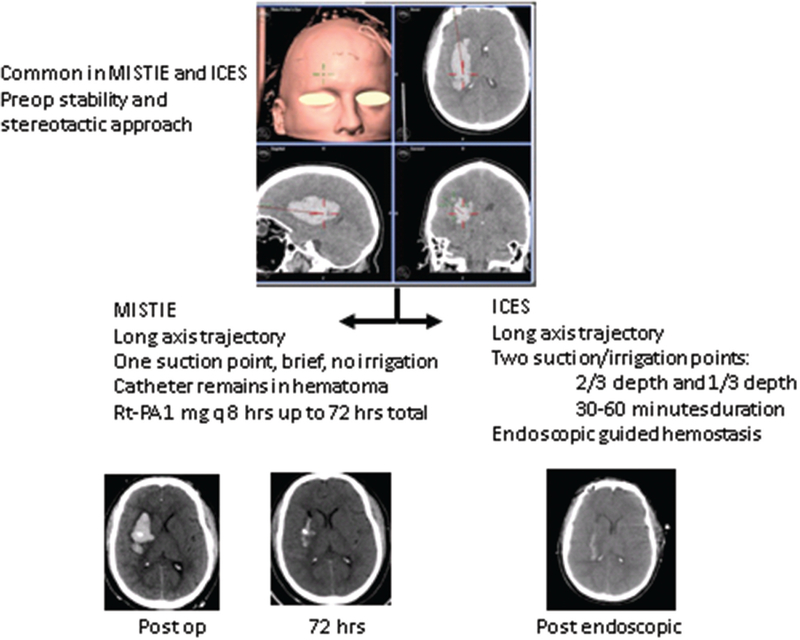

The National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has funded 2 randomized controlled studies of minimally invasive surgery for ICH. The first is entitled the Minimally Invasive Surgery Thrombolysis Plus Recombinant Tissue-type Plasminogen Activator for ICH Evacuation (MISTIE)27 and the second is entitled Intraoperative Computed Tomography–guided Endoscopic Surgery (ICES) for ICH. The studies are coordinated through an executive committee and designed to be cooperative in nature and make use of identical inclusion and exclusion criteria, timing of surgery, and medical treatment protocols. A total of 35 centers are participating in MISTIE and an additional nonoverlapping 8 centers are participating in ICES. The main data coordinating center for both studies in Johns Hopkins Brain Injury Outcomes Center and the 2 surgical coordinating centers are the University of Cincinnati (MISTIE) and the University of California, Los Angeles (ICES). The studies are designed to demonstrate safety of early minimally invasive surgical evacuation of ICH within 48 hours of hemorrhage onset as compared with best medical management. The surgical entry window, stereotactic approach, and fundamental presurgical safety imaging (computed tomography angiography) are the same in both studies (Figure). Novel surgical, such as the eyebrow approach, is being used to create novel surgical trajectories that theoretically try to avoid creating new damage by traversing the corticospinal tracts.28 The studies are jointly monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board. The outcome measures are exactly the same and consist of 90, 180, 365 days assessment of modified Rankin Outcome. The safety end points include mortality, surgical mortality, surgical-related repeat bleeding, and surgical-related infection.

Figure.

The minimally invasive surgical approach for minimally invasive surgery thrombolysis plus recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for intracerebral hemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE) and intraoperative computed tomography (CT)–guided endoscopic surgery (ICES). Top, The preoperative screening, imaging, and intraoperative image guidance is similar in both studies. The trajectory along the longest axis of the hematoma is shown, in this case the supraorbital approach. Middle, Highlights of the MISTIE and ICES procedures. Note that MISTIE uses repeat doses of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) through a catheter that is left in place, whereas ICES does not. Bottom, CT images of postoperative appearance in MISTIE (hematoma remains with catheter in center) followed by gradual resolution of the ICH. CT image of postoperative appearance in ICES showing >80% hematoma removal.

For both the MISTIE and the ICES studies, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized below: inclusion criteria: spontaneous, supratentorial, primary ICH within 48 hours from onset, men or women, aged 18 to 89 years, inclusive, written informed consent ICH volume >20 cc, Glasgow Coma Score >5, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score >5. The exclusion criteria are: ICH secondary to: cervicocephalic aneurysm, intracranial arteriovenous malformation, intracranial tumor, trauma, hemorrhagic transformation of an ischemic infarction, isolated intraventricular hemorrhage, Glasgow Coma Score <5, nonreversible coagulopathy, significant prior disability (premorbid modified Rankin Scale, ≥2), known allergy to MR contrast agent, participation in any clinical treatment trial within prior 30 days. The medical management is uniform in both studies.

To date, both studies have reached completion of enrollment of subjects but are in the follow-up phase.

Open Questions about Surgical Evacuation of ICH

There are many open questions about the process of surgical evacuation of ICH. (1) The optimal timing of hematoma evacuation remains unclear. We have chosen a time window of 48 hours to optimize the safety of the procedures and to permit stability of the hematoma. In this way, the hemorrhagic expansion process has stabilized, and we avoid confounding the potential benefits of surgery with the negative effects of recurrent bleeding.6,16 Testing ultra early surgery would require prothrombotic hemostatic agents or ultra early blood pressure control. (2) The optimal time to maximum clot removal remains unclear. The MISTIE procedure is a gradual process of hematoma volume reduction >72 hours, whereas the ICES procedure is a rapid process of hematoma volume reduction >1 hour. It is unclear if 1 approach is superior. (3) The optimal hematoma location for surgery remains unclear, but may be better after bleeding has stopped in the 24- to 72-hour time window.16,29 There may be brain regions that are better adaptable to 1 minimally invasive technique.(4) Selection of candidates who are likely to respond to minimally invasive surgery remains unclear. The predictors of poor outcome without surgery include hemorrhage location, but it is not clear that these predictors hold true once surgery has been performed (as is suggested by preliminary ICES and MISITE data). Preliminary reports of these studies suggest that 180-day prognosis is associated with residual size of the postsurgical hematoma.16,27

Conclusions

ICH is a devastating illness for which preliminary data from surgical trials indicate that surgery may be helpful. To date, this premise remains unproven. Ongoing trials, including STICH II, MISTIE, and ICES, are attempting to determine the potential for surgical efficacy for limited craniotomy and image guide minimally invasive surgical removal using thrombolysis or endoscopic evacuation. Preliminary results seem promising.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the clinical trial expertise of Karen Lane, Amanda Bistran-Hall, Courtney Real, and the entire Brain Injury Outcomes center.

Disclosures

Drs Vespa, Martin, Awad, Zuccarrelo, and Hanley have received funding from the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Dr Vespa is consultant for Edge Pharmaceutical. Dr Martin is a consultant for Zoll. Dr Hanley receives medical legal consultation fees.

Contributor Information

Paul M. Vespa, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, CA.

Neil Martin, Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, CA.

Mario Zuccarello, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH.

Issam Awad, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Daniel F. Hanley, Department of Neurology, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1.Sacco S, Marini C, Toni D, Olivieri L, Carolei A. Incidence and 10-year survival of intracerebral hemorrhage in a population-based registry. Stroke. 2009;40:394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344: 1450–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, et al. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Incidence and time course. Stroke. 1996;27:1783–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, Broderick J, Davis S, Diringer MN, et al. ; FAST Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2127–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebel JM Jr, Jauch EC, Brott TG, Khoury J, Sauerbeck L, Salisbury S, et al. Natural history of perihematomal edema in patients with hyperacute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33:2631–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KR, Kawai N, Kim S, Sagher O, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of edema formation after intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of thrombin on cerebral blood flow, blood-brain barrier permeability, and cell survival in a rat model. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim-Han JS, Kopp SJ, Dugan LL, Diringer MN. Perihematomal mitochondrial dysfunction after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:2457–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Powers WJ. Transient focal increase in perihematomal glucose metabolism after acute human intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1638–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller CM, Vespa PM, McArthur DL, Hirt D, Etchepare M. Frameless stereotactic aspiration and thrombolysis of deep intracerebral hemorrhage is associated with reduced levels of extracellular cerebral glutamate and unchanged lactate pyruvate ratios. Neurocrit Care. 2007;6:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKissock W, Richardson A, Taylor J. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage: a controlled trial of surgical and conservative treatment. Lancet 1961;2:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juvela S, Heiskanen O, Poranen A, Valtonen S, Kuurne T, Kaste M, et al. The treatment of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. A prospective randomized trial of surgical and conservative treatment. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batjer HH, Reisch JS, Allen BC, Plaizier LJ, Su CJ. Failure of surgery to improve outcome in hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage. A prospective randomized trial. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1103–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgenstern LB, Demchuk AM, Kim DH, Frankowski RF, Grotta JC. Rebleeding leads to poor outcome in ultra-early craniotomy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56:1294–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auer LM, Deinsberger W, Niederkorn K, Gell G, Kleinert R, Schneider G, et al. Endoscopic surgery versus medical treatment for spontaneous intracerebral hematoma: a randomized study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuccarello M, Brott T, Derex L, Kothari R, Sauerbeck L, Tew J, et al. Early surgical treatment for supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: a randomized feasibility study. Stroke. 1999;30:1833–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM, Hope DT, et al. ; STICH Investigators. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niizuma H, Otsuki T, Johkura H, Nakazato N, Suzuki J. CT-guided stereotactic aspiration of intracerebral hematoma—result of a hematomalysis method using urokinase. Appl Neurophysiol. 1985;48:427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaller C, Rodhe V, Meyer B et al. Stereotactive puncture and lysis of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage using recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator. Neurosurgery 1995;36:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohde V, Rohde I, Thiex R, Ince A, Jung A, Dückers G, et al. Fibrinolysis therapy achieved with tissue plasminogen activator and aspiration of the liquefied clot after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: rapid reduction in hematoma volume but intensification of delayed edema formation. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:954–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vespa P, McArthur D, Miller C, O’Phelan K, Frazee J, Kidwell C, et al. Frameless stereotactic aspiration and thrombolysis of deep intracerebral hemorrhage is associated with reduction of hemorrhage volume and neurological improvement. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett RJ, Hussain R, Coplin WM, Berry S, Keyl PM, Hanley DF, et al. Frameless stereotactic aspiration and thrombolysis of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2005;3:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho DY, Chen CC, Chang CS, Lee WY, Tso M. Endoscopic surgery for spontaneous basal ganglia hemorrhage: comparing endoscopic surgery, stereotactic aspiration, and craniotomy in noncomatose patients. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:547–55; discussion 555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishihara T, Morita A, Teraoka A, Kirino T. Endoscopy-guided removal of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: comparison with computer tomography-guided stereotactic evacuation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley DF, et al. MISTIE Phase II results: Safety, efficacy, and surgical performance. Available at: AHA ISC Stroke Conference 2012. http://my.americanheart.org/professional/Sessions/InternationalStrokeConference/ScienceNews/ISC-2012-Late-Breaking-Science-Oral-Abstracts_UCM_435384_Article.jsp. Accessed February 2, 2013.

- 28.Dye JA, Dusick JR, Lee DJ, Gonzalez NR, Martin NA. Frontal bur hole through an eyebrow incision for image-guided endoscopic evacuation of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiner T, Vincent C, Morris S, Davis S, Vallejo-Torres L, Christensen MC. Neurosurgical outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage: results of the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke Trial (FAST). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]