Abstract

Cancer immunotherapy is emerging as a promising treatment modality that suppress and eliminate tumor by re-activating and maintaining the tumor-immune cycle, and further enhancing the body’s anti-tumor immune response. Despite the impressive therapeutic potential of immunotherapy approaches such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and tumor vaccines in pre-clinical and clinical applications, the effective response is limited by insufficient accumulation in tumor tissues and severe side-effects. Recent years have witnessed the rise of nanotechnology as a solution to improve these technical weaknesses based on its inherent biophysical properties and multifunctional modifying potential. In this review, we summarized and discussed the current status of nanoparticle-enhanced cancer immunotherapy strategies, including intensified delivery of tumor vaccines and immune adjuvants, immune checkpoint inhibitor vehicles, targeting capacity to tumor-draining lymph nodes and immune cells, triggered releasing and regulating specific tumor microenvironments, and adoptive cell therapy enhancement effects.

Introduction

1. Basics of immunotherapy and tumor microenvironment

The immune system acts as the “police force” to protect the organism from foreign invaders including bacteria, germs, viruses and parasites. The recognition and eradicating of the foreign invaders rely on precise cooperation of two components of the immune system: the innate and adaptive immunity. The innate immunity acts as the first-line of defense through rapid activation of granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils and mastocytes) and phagocytes (macrophagocytes and dendritic cells), which recognize general molecular patterns on pathogens or danger signals derived from inflammation, infection and tissue damage.1, 2 The adaptive immunity functions by recognizing specific antigens (specificity) instead of the general molecular patterns, and it is capable to response rapidly to pathogens or antigens that has encountered before (memory).3 These characteristics are implemented by random rearrangement of massive sequences in gene cassettes encoding the antigen recognition receptor complex that locates on the surface of lymphocytes. Huge variations of T-cell and B-cell receptors (TCR, BCR) for antigens with theoretically limitless specificities of T-cells and B-cells can be generated by this random rearrangement. The immune system launches a series of essential activities after the initial encounter with pathogens, which include rapid recruitment of non-antigen-specific innate immune cells, activation of humoral immune responses, pathogen processing and presentation by antigen presenting cells (APCs) to T-cell and B-cell lymphocytes, following by a more time-consuming and elaborate activation and expansion of antigen-specific lymphocytes, and finally lead to clearance of pathogens.4, 5 The sequential implement of the innate and adaptive immunity could also leave pools of longeval memory lymphocytes that are specific to the invading antigen that can respond much quicker at the subsequent encounters with the same pathogen.

Cancer can be regarded as a genetic disease that involves genes with key roles in cell proliferation and differentiation, which gives the cells ability to proliferate out of control and invade to regional or distant regions.6 The immune system is also responsible for recognizing and destroying the aberrant cells, and prevents the occurrence or development of cancer, which requires the immune cells to have the ability to effectively recognize cancer versus normal cells.7, 8 Mature T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes are actually the remaining cells that have passed the negative clonal selection during their development in thymus and bone marrow, in which lymphocytes expressing high affinity antigen receptors to self-antigens are eliminated. Although the negative clonal selection process reduces the harm of autoimmunity to the body, it also eliminates the cell clones having the specificity that could potentially target and resist cancer cells. As a result, the minority proteins encoded by chromosomal aberrations or synthesized through altered post-translational modifications that are exclusively to tumor cells, also named tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), become the crucial subject for immune cells to recognize cancer cells.9, 10 In some cases, the immunogenic TAAs could be normal self-proteins that are not expressed in differentiated cells or only expressed at low level, but expressed or overexpressed in cancer cells.

Rapid growth of tumor is often accompanied with vast tumor cell death due to hypoxia or accumulation of gene mutation, which will lead to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and TAAs.11 The DAMPs can stimulate and recruit phagocytes and APCs, which process and present TAA-derived peptides to tumor-specific lymphocytes through major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The activated CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes specifically recognize and eliminate the cancer cells through TCR-mediated recognition of TAA epitopes displayed by tumor MHC-Ⅰ molecule or through the combination of NKG2D receptor on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and NKG2D ligands expressed on tumor cells. Activated CD4+ T-lymphocytes generate cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon-γ that are able to inhibit tumor growth while also upregulate MHC-Ⅰ expression on tumor cells, thus assisting the targetly recognition by TAA-specific CD-8+ T-lymphocytes.12 (Figure 1)

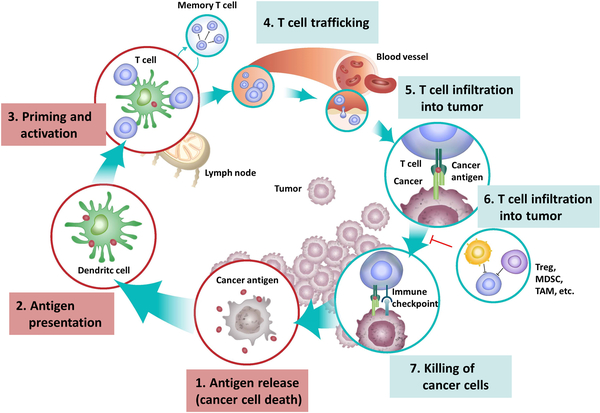

Figure 1.

The cancer-immunity cycle that involves exposure or release of tumor antigens, tumor antigen processing and presentation by APCs, priming and activation of effective immune cells and formation of memory cells, trafficking and infiltration of T cells to tumor tissues, and the recognition and killing of tumor cells. Figure from reference 10 with permission obtained.

Immune system activation towards cancer cells leads to a competition wherein immune cells inhibit and fast cellular proliferation and mutation foster tumor growth, but the formation of a detectable tumor is often the result of the failure of body immunity to tumor cells. If the immunity could not eradicate all the tumor cells at the beginning, it usually forms a selective force to tumor cell clones that can alter the composition of tumor, and gradually leave and promote the growth of tumor cell colons with the least immunogenicity. Ultimately, the immunoediting effect often give rise to the most invasive and uncontrolled tumors formed by the most insensitive cells.13 Tumor cells have the several mechanisms that assist in evading from being detected and eliminated by the immune system:

-

(1)

Downregulation of MHC-Ⅰ on tumor cells as consequence of mutations of MHC genes or molecules involved in TAA antigen processing and presentation can reduce immunogenicity of tumor cells and evade cytotoxic T-lymphocyte mediated lysis.14

-

(2)

Tumor cells could suppress immunity by expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) that binds to the negative co-stimulator programmed death (PD)-1 on lymphocyte’s membrane, or by secreting immunosuppression cytokines that suppress the activation and differentiation of APCs and lymphocytes, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.15, 16

-

(3)

Tumor cells could resist cytotoxic T-lymphocyte mediated killing effects by expressing granzyme serine proteases to inhibit the perforin/granzyme pathway that mediates tumor cell lysis, and decoy receptors for cell death including soluble Fas, osteoprotegerin and decoy receptor-3, 4. In addition, increased expression of oncogenic and antiapoptotic molecules such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) also resist T-lymphocytes mediated lysis.17

-

(4)

Immunoregulatory cells with immunosuppressive effects, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells and M2 type tumor-associated macrophages, could be recruited by tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which could produce immunosuppressive cytokines, and also secrete vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases that favor tumor angiogenesis for tumor growth and invasion.18, 19

-

(5)

A physical barrier around the tumor could be generated by tumor cells through secreting series of molecules such as collagen, thus forming an immune privilege area and preventing the lymphocytes and APCs from entering tumor area.20

2. Introduction of nanotechnology in cancer immunotherapy

On the basis of these mechanisms, numerous novel molecular drugs aiming to enhance immunity against tumor cells have been rising in the past decade, and exhibited considerable progresses in both lab experiments and clinic treatments.21–23 However, only limited portion of the immunotherapeutic molecules could encounter and interact with the targets, as the majority will be eliminated by renal clearance, impeded by metabolism during the blood circulation or cannot penetrate biological barriers and successfully reach the target site.24, 25 Under the circumstance, nanoparticles are utilized as suitable vehicles for immunotherapeutic molecules to counteract the pharmacokinetic shortages. Due to the inherent property, nanoparticle could passively enrich within tumor tissue because of the immature tumor vasculature and damaged lymphatic drainage, which is also known as the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect.26 The first generation nanoparticles principally depended on the EPR effect to enrich in tumor tissues, but the treatment effects varied among different types of cancer mainly because of variances in the tumor vascular structure and permeability.27 Similarly, effects of the passive enriched nanoparticles on metastatic tumor lesions were often insufficient also due to the different vascular beds of metastatic lesions.28 To overcome this limitation, positive target ability is equipped through modification of the nanoparticles with tumor-specific antibodies, and cellular uptake is also intensified, thus enhancing treatment efficacy and lowering off-target side-effects.29

Proper selection and construction of the nanoparticle structure in the aspects of size, shape, coated ligands, loading method, zeta potential, hydrophilicity, elasticity and biocompatibility lead to suitable nano-vehicles for immunotherapeutic molecules, which generally ought to have prolonged biological half-life period, protect payloads during circulation, penetrate through barriers or have target effects, controlled release payloads under specific microenvironments, and have low biotoxicity. Nanoparticles less than 5 nm in diameter trend to be excreted through renal filtration, and nanoparticle with diameter larger than 200 nm could be rapidly eliminated in spleen due to the size of inter-endothelial slits30, thus the diameter ranged from 5 to 200 nm is the optimal size for nanoparticles. The shape of nanoparticles should also be elaborated as different shapes process different characteristics. For instance, worm-like nanoparticles exhibit preferable fluid dynamics compared with rod-, fingerprint-shaped or spherical nanoparticles31; spherical nanoparticles are less likely to be accumulated in spleen, but flat cylindrical nanoparticles had the most retention in the organs of liver, lung and spleen.32 Nanoparticles with slight negative charge had significantly lower retention in organs and had prolonged circulation half-lifetime, but positive surface charge could assist the adherence to anionic cellular membrane and is more advantageous in inducing cellular internalization.33, 34 Structural stability in blood circulation is another critical aspect, which is needed to take caution especially for nanoparticles like polymeric micelles, as they are often not able to maintain the structural integrity well in the rapid bloodstream and will cause declines in delivery efficiency.35 Special designs including intensified structure stability or environment-triggered releasing strategy are needed for these nanoparticles to achieve preferable transportation ability. Collectively, appropriate design of nanoparticles in accordance with the experimental purposes facilitates in optimizing the delivery efficiency and therapeutic effects of payloads.

Nanoparticles have been widely researched to be incorporated into tumor immunotherapy in the recent years based on its inherent biophysical properties and multitudinous modifying potential, with tremendous progresses been made in preclinical and clinical trials. However, there are few reviews summarizing the advances in the fast-updating research area. In this review, we summarized and discussed the current status of nanoparticle-enhanced cancer immunotherapy strategies in the aspects of intensified delivery of tumor vaccines and immune adjuvants, ICIs vehicles, targeting capacity to tumor-draining lymph nodes and immune cells, triggered releasing and regulating specific tumor microenvironments, and adoptive cell therapy enhancement effects.

Delivery of tumor vaccines by nanoparticles for tumor immunotherapy

Immune escape is often caused by the loss of valid TAAs processing and presentation by immune cells, hence the additional provision of specific tumor antigens to immune cells could stimulate and enhance anti-tumor immune process.36, 37 Traditionally, most of the antigens are purified cytomembrane proteins, peptides, polysaccharides, or the DNA or RNA encoding these tumor antigens, which have medium reactogenicity but generally weak immunogenicity due to insufficient exogenous immune-provoking components. The emergence of whole-cell antitumor vaccines not only imported multiple tumor-specific antigens but also enhance the antitumor immunoreaction. Accompanied by advanced delivery methods of nanoparticles that could precisely load the antitumor vaccines to targeted lymph nodes or immunocytes, the effects have been amplified in the recent years.

Table 1 summarized the basic characteristics of recent studies focusing on the antitumor vaccine delivery by nanoparticles, and the therapeutic effects are listed in Table 2.38–51 By the form of payloads, it could be classified into three categories: tumor specific antigen delivery, immune bio-adjuvant delivery and co-delivery of antigen and adjuvant. In order to generate antitumor immunity in experiments, ovalbumin (OVA) was most selected as the model tumor antigen due to its exogeneity, easy feasibility and suitable immunogenicity. OVA was conjugated as payloads to various types of nanoparticles, including silica nanoparticles38, liposomes42, 47, 49, gold nanoparticles41, alginate nanoparticles43 and polymeric nanoparticles46, and injected to mice bearing OVA-expressing melanoma, lymphoma or thymoma-bearing animal models. Compared with single delivery of antigen, conjugated delivery of antigen-nanoparticle compounds induced significantly stronger antigen-specific antibody responses and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses accompanied with increased levels of antigen-specific IgG, interferon-γ and specific types of interleukins, inhibiting tumor growth and prolonging survival of mice (Table 2). On the other hand, delivery of multiple antigens instead of only single OVA may further enhance the anti-tumor immunoreaction. Zhang et al conjugated two tumor specific peptides and one immunoadjuvant with layered double hydroxide nanoparticles and found a significantly stronger inhibition effects to melanoma compared with single antigen-delivering nanoparticles.40

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of recent studies focusing on the antitumor vaccine delivery by nanoparticles

| Studies | Nanoparticles | Size | Shape | Balanced surface charge |

Payload | Experimental subject |

Tumor model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu et al.30 | Organosilica NP | 200 nm | Sphere | Not Given | Encapsulated: OVA and TLR agonist (CpG) | C57BL/6 mice | Murine B16-OVA melanoma |

| Yan et al.31 | Layered double hydroxide NP and nanosheet | 109.2nm (NP), 176.8 nm (nanosheet) | Flat cylindrical and sheet | Not given | Coated: OVA and CpG | C57BL/6 mice | Murine E.G7-OVA T-lymphoma |

| Zhang et al.32 | Layered double hydroxide NP | 108.4 nm | Flat cylindrical | +39.0 mV | Coated: Neo-epitopes and CpG | C57BL/6 mice | Murine B16F10 melanoma |

| Yata et al.33 | Gold NP | 50 nm | Not Given | Not Given | Coated: CpG DNA | C57BL/6 mice | Murine E.G7-OVA T-lymphoma |

| Thomas et al.34 | Liposome | 81–103/121–160 nm | Sphere | −6~−8 /+4~+6 mV | Coated: OVA | BALB/c, C57BL/6 mice | N/A |

| Zhang et al.(2)35 | Alginate NP | 310 nm | Sphere | −45.6 mV | Coated: OVA | BALB/c, C57BL/6 mice | Murine E.G7-OVA T-lymphoma |

| Sokolova et al.36 | LCP | 275 nm | Sphere | +20 mV | Coated: TRL ligand | BALB/c, C57BL/6 mice | N/A |

| Liu et al.37 | LCP | 58 nm | Sphere | +38 mV | Encapsulated: anti-CTLA-4 antibody and mRNA encoding tumor antigen MUC | BALB/c mice | Murine TNBC 4T1 mammary carcinoma |

| Pearson et al.38 | PLGA | 72.2–656 nm | Sphere | −56.0~−31.5 mV | Coated/Encapsulated: OVA and PLP | SJL/J and C57BL/6 mice | N/A |

| Verbeke et al.39 | Cationic liposome | 160 nm | Sphere | +50 mV | Encapsulated: MPLA and mRNA encoding OVA | C57BL/6 mice | N/A |

| Takahashi et al.40 | Carbonate apatite NP | 30–40 nm | Sphere | Not given | Encapsulated: CpG and ODN | C57BL/6 mice | N/A |

| Yoshizaki et al.41 | Cationic liposome | 88–110 nm | Sphere | −65~−60/−11~−19 mV | Coated: TRX, CpG DNA; Encapsulated: OVA, CpG DNA | C57BL/6 mice | Murine E.G7-OVA T-lymphoma |

| Liang et al.42 | Liposome | 80–100 nm | Sphere | Not Given | Encapsulated: mRNA encoding hemagglutinin | Not Given | N/A |

| Xu et al.43 | TMC complex | 150 nm | Sphere | +28 mV | Encapsulated: PTX and DNA encoding (GM-CSF)-Fc | BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice | HeLa and B16 melanoma cells |

Abbreviations: CpG, cytosine phosphorothioste-guanine; DC, dendritic cell; LCP, Lipid-calcium-phosphate; MPLA, monophosphoryl lipid A; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; PLGA, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); PLP, proteolipid peptides; PTX, paclitaxel; TMC, trimethylchitosan; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TRX, 3,5-didodecyloxybenzamidine.

Table 2.

Therapeutic effects of recent studies focusing on the antitumor vaccine delivery by nanoparticles

| Studies | Therapeutic effects |

|---|---|

| Lu et al.30 | • APC’s cellular uptake of both OVA and CpG was significantly enhanced in organosilica NP-encapsulated form than the free form. • OVA-and CpG-Organosilica NP induced cellular endosome escape for antigen cross-presentation. • OVA-and CpG-Organosilica NP decreased GSH level and increase ROS level in vitro and in vivo, facilitating CTL proliferation, reducing tumor growth and prolonged survival in melanoma mice model. |

| Yan et al.31 | • Nanomaterials induced much stronger humoral and cell-medicated immune responses, evidenced by higher levels of IgG1, IgG2a and interferon-γ. • LDH nanosheets showed higher activity to promote specific antibody response than LDH NPs but with a similar cell mediated immune response. • Nanomaterials inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in vivo. |

| Zhang et al.32 | • LDH-NP induced significantly higher CTL activity and inhibited melanoma growth in vivo. |

| Yata et al.33 | • Gold NP increased tumor-associated antigen-specific IgG and interferon-γ expression in vivo. • Gold NP significantly delayed tumor growth and extended the survival of mice. |

| Thomas et al.34 | • Mice immunized with OVA delivered by NP produced much higher antibody titers than those without NP. • 80 nm anionic nanoliposome is the most efficient type in eliciting higher humoral and cellular immune response. |

| Zhang et al. (2)35 | • Alginate NPs facilitated OVA uptake and its cytosolic release in DC, and also enhanced the expression of surface co-stimulatory molecules of the DC. • Alginate NPs enhanced in vivo trafficking of OVA to draining lymph nodes and strengthened cross presentation of OVA to T cell hybridoma. • Alginate NPs induced major CTL response and the inhibition of tumor growth in vivo. |

| Sokolova et al.36 | • NP with Anti-146 could target the liver by intravenous injection. • The expression of IFN-α/β, TNF-α, IL-6 and IP-10 in hepatocytes, NPCs and LSECs was significantly increased by NP. |

| Liu et al.37 | • Nanoliposome targeted to mannose receptors on DCs, led to tumor antigen expression and induced a strong, antigen-specific CTL response against tumor cells. • Co-encapsulated anti-CTLA-4 antibody significantly enhanced the anti-tumor immune response compared to the mRNA alone-NPs. |

| Pearson et al.38 | • Immune cells’ cellular interaction induced by 80 nm PLGA NP was significantly lower than the 400 nm PLGA NP. • CD25 expression on T cells was particle size independent. • Induction of Tregs was particle size and concentration dependent. |

| Verbeke et al.39 | • Liposome induced high antigen expression and effective antigen-specific T cell immunity in vivo without provoking a type I IFN response. |

| Takahashi et al.40 | • CA nanoparticles containing CpG ODNs induced significant IFN-α production by mouse dendritic cells and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. • NP enhanced the production of interleukin-12 and IFN-γ. • Treatment with NP resulted in higher cytokine production in draining lymph nodes, and induced higher antigen-specific antibody responses and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in vivo in an interleukin-12-and type-I IFN-dependent manner. |

| Yoshizaki et al.41 | • Liposome promoted cytokine production from DCs and expression of co-stimulatory molecules in vitro. • Liposome induced antigen-specific immune responses, inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in vivo. |

| Liang et al.42 | • Nanoliposome induced rapid and local infiltration of neutrophils, monocytes and DCs to the site of administration and draining lymph nodes. • APCs efficiently internalized nanoliposomes, translated the encapsulated mRNA and upregulated key co-stimulatory receptors including CD80 and CD86. • Nanoliposome resulted in priming of H10-specific CD4+ T cells exclusively in draining lymph nodes, and induced type-1 IFN-polarized innate immune response. |

| Xu et al.43 | • Nano-complex enhanced intracellular uptake of DCs, upregulated the costimulatory molecules of CD80 and CD86, promoted promoted the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, reduced the generation of immunosuppressive FoxP3+ Treg cells. • Nano-complex has a synergistic effect on the maturation and function of DCs, increased immune stimulation and reduced immune escape, inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in vivo. |

Abbreviations: APC, antigen presenting cell; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; DC, dendritic cell; LDH, Layered double hydroxide; NPs, nanoparticles; OVA, ovalbumin; Tregs, Regulatory T cells.

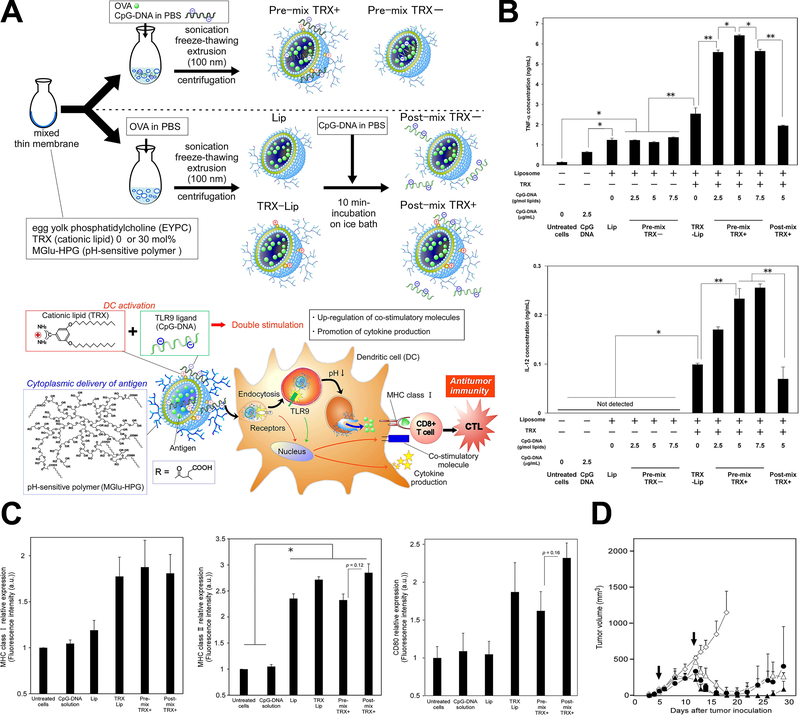

Genetic antigens could also be the payload of nanoparticles to simulate immunity against cancer. After delivered intracellularly, tumor specific antigens or immune adjuvants encoded by the genetic vaccine could be formed through transcription and translation, and continuously stimulate immune system to generate long-term immunity.49 (Figure 2) It also has the advantages of easy manufacturing and preserving, strong cellular immunity stimulating, cross-immunity inducing and promising immunogenicity. Recent studies exhibited efficiency of the anti-tumor genetic vaccines in inducing both antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response, humoral immune response and tumor suppression effects.41, 45, 47, 49, 50 However, its safety concerns should still be noted for the possibility of genomic instability caused by the integration into genome of the host cell, and the immunologic tolerance of the immune system after long-term overexpression of the encoded antigens.

Figure 2.

Genetic tumor nanovaccine enhanced immunotherapy. (A) Synthesis process and working mechanism of the nanoliposome. (B) Enhanced secretion of TNF-α and IL-12 after treatment. (C) Increased MHC-Ⅰ, MHC-Ⅱ and CD80 expression after treatment. (D) In vivo anti-tumor effects of the genetic liposome nanovaccine. Figures from reference 49 with permission obtained.

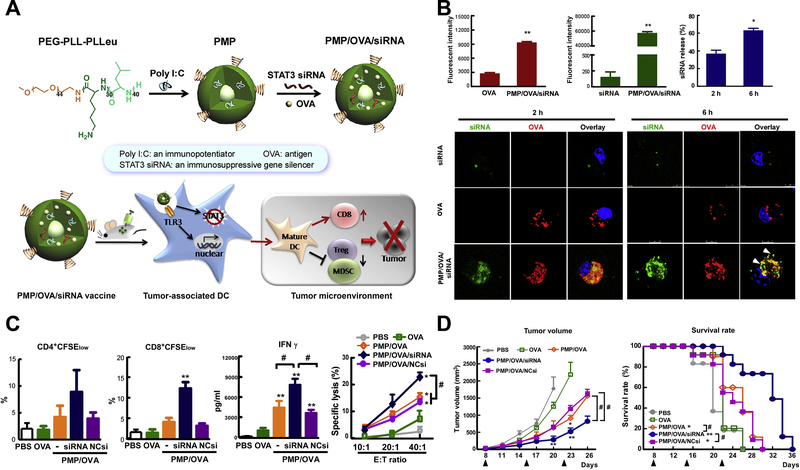

Bio-adjuvants of cancer vaccine are usually ligands to pattern recognition receptors, including toll-like receptor (TLR), C-type lectin receptor, NOD-like receptor and RIG-like receptor, which could assist the innate immune response, facilitate polarization of naive T lymphocytes to T helper cells, and accordingly induce the adaptive immunity.52–54 TCR agonists are the most studied immune adjuvant integrated to nanoparticles, and it showed significantly higher immune activation effects than the free soluble form. The co-delivery of adjuvant with antigen within the same nano-system achieved even better results, mainly through mechanisms of enhancing the immunogenicity of weak antigens, reducing the required amount of antigen for effective immune stimulation, and preserving payloads from biolysis. Among the studies, several types of TLR agonists (for example, CpG (TLR9 agonist) and MPLA (TLR4 agonist)) were usually simultaneously conjugated to nanoparticles accompanied with another TAA to realize stronger effects, as multiple TLRs were generally required to be stimulated by pathogens to further increase the levels of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines.55 In addition, the co-delivery of immune bio-adjuvants with immunosuppressive pathway inhibitors could also significantly suppress the proliferation of immunosuppressive cells and synergistically enhance the tumor-specific cellular immune response.56 (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Tumor-specific cellular immune response induced by tumor nanovaccine co-delivering bio-adjuvant and immunosuppressive pathway inhibitor. (A) Synthesis and working mechanism of the co-delivery nanovaccine. (B) Enhanced cellular uptake and intracellular localization of siRNA and tumor antigen (OVA) in mouse bone marrow dendritic cells. (C) Increased tumor antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation, IFN-γ production and CTL response by the nanovaccine. (D) The anti-tumor effects of the co-delivery nanovaccine and survival curves of tumor-bearing mice. Figures from reference 56 with permission obtained.

The whole cell antitumor vaccine is mainly generated from two sources, whole tumor cell membrane or tumor cell lysates. Different from individual tumor specific antigen, the whole cell antitumor vaccine contains full range of epitopes and could induce multivalent immune response.57, 58 Several groups fabricated core-shell PLGA nanostructures coated with cancer cell membrane antigens, and formed a robust platform towards multi-antigenic immune responses. For instance, Yang et al loaded PLGA nanoparticle with TLR7 agonist and an immunomodulator imiquimod, and then coated the compound with cancer cell membrane to form an immune-adjuvant whole cell antitumor nanovaccine. In combination with checkpoint blockade therapy, the nanovaccine significantly activated anti-tumor immune cells and exhibited outstanding therapeutic efficacy against established tumor lesions.59 Lysates of resected tumor tissues were also conjugated to nanoparticles with immune adjuvants in other studies to direct immune responses against cancer.60, 61 In addition, clay nanoparticles with antigens loaded was found to be able to form subcutaneous nodules with loose structure at the site of injection, which acted as a depot for sustained antigens release and immune cells recruit, and induced continuous immune stimulation and memory T-cell proliferation for up to 35 days.62 Anther strategy to develop whole cell antitumor vaccine by nanoparticle is to generate the TAAs in situ, which means the generation of tumor cell lysates from damaged or dying cancer cells. It has been proved that the TAAs could be generated in situ after chemotherapy63 or radiotherapy64, and more importantly, combined with photothermal therapy (PTT) or photodynamic therapy (PDT), specific nanoparticle platforms developed by Chen65 and Xu et al66 were shown to have the ability to significantly further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of PTT and PDT, reinforce tumor cell destruction and the subsequent TAAs generation in situ, thus inducing strong antitumor immunity to inhibit the development of original and metastatic tumor lesions.

Nanoparticles delivering immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors emerge as the hot-spot in tumor immunotherapy recently. PD-1 is one of the most important immune checkpoint molecules which is overexpressed on activated T lymphocytes and has a tight correlation with tumor-associated immune suppression. In normal situation, combination of PD-1 and PD-L1 can transmit inhibitory signals and reduce the proliferation of CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes, and PD-1 can also control the accumulation of antigen-specific T cells in lymph nodes by regulating the bcl-2 gene, thus protecting normal tissue from attacking under autoimmunity.67–69 However, tumor cells could also escape from immune attack by overexpressing the PD-L1. Similarly, CTLA-4 could induce T-lymphocytes to be non-reactive and negatively regulate immune response after its incorporation with B7 expressed on activated APCs.70, 71 The immune checkpoint inhibitors including anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies have entered into clinical treatments and showed impressive curative effects, however, the efficacy is still limited by the relative low rate of treatment response and high incidence of side-effects. Therefore, nanoparticles are considered for the delivery of these drugs in a targeted and sustainable-releasing pattern, thus reducing treatment dose and decreasing side-effects.

Among the studies developing nanoparticles for delivery of immune checkpoint inhibitors, although a variance in the nanoparticle types and sizes existed, the conjugation could enhance the immune response against tumor and decrease side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors,72–78 which is mainly due to the accumulation of nanoparticles and the sustained releasing of inhibitors in the tumor tissue, as proven by Meir et al. that the amount of inhibitor accumulation within tumor tissues was linearly correlated with the intensity of immune response against cancer.79 Furthermore, as the anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA4 treatment have been proven to have a synergistic treatment effect due to the different mechanisms, Chae et al. constructed a nano-system delivering both of the inhibitors, and found a significantly slower tumor growth rate and longer survival of mice in the combined treatment group than either of the individual drug group.80

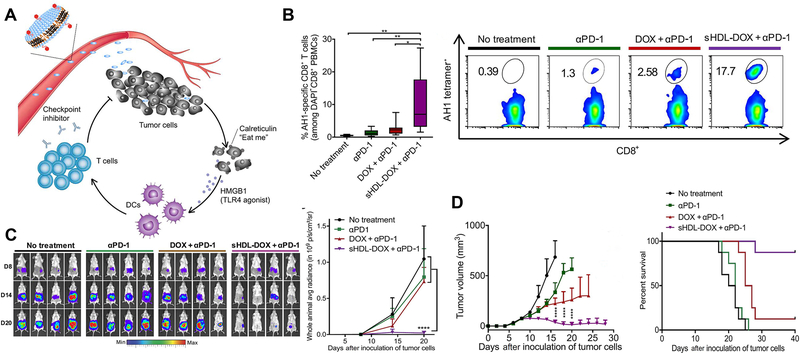

In addition, there are studies combining the nanoparticle conjugated-immune checkpoint inhibitors with other treatment methods to further intensify therapeutic effects. Kuai et al integrated lipid-doxorubicin (DOX) and anti-PD-1 antibody with synthetic high-density lipoprotein (sHDL) to form pH-responsive nanoparticles.81 The prolonged circulation enables adequate intratumoral delivery, followed by internalization by tumor cells and pH-related release of payloads in the endosomes and lysosomes. Released DOX killed tumor cells, and induced immunogenic cell death and release of danger signals, recruiting APCs to phagocytose the immunogenically dying tumor cells. The immune response would be further enhanced accompanied with the anti-PD-1 antibodies, leading to elimination of tumors and prevention of tumor relapse. As a result, the sHDL-DOX+anti-PD-1 nanoparticles significantly induced antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell response, suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival than the free DOX+anti-PD-1 treatment or the single anti-PD-1 treatment. (Figure 4) Similar results were also found by Wang et al when PD-L1 siRNA coated nanoparticles were integrated with photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy that the combined nanoystem efficiently stimulate immune response and silenced immune resistance, inhibiting tumor growth and preventing recurrence.82

Figure 4.

Elimination of tumor by chemoimmunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitor-conjugated nanoparticle. (A) Schematic of immune checkpoint inhibitor-combined nanoparticles for chemo-immunotherapy. (B) Percentage of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells after treatment and the corresponding scatterplots. (C) Whole-animal in vivo imaging of tumor after treatment and quantification of the bioluminescence signal. (D) Tumor growth and survival curves after treatment. Figures from reference 81 with permission obtained.

Another established negative feedback protein that suppresses immune response and assists tumor cell proliferation is indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which mediates the degradation of tryptophan to kynurenine and other metabolites, thus leading to intracellular accumulation, inducing cell cycle arrest and death of effector T lymphocytes, and promoting regulatory T cell proliferation with the immunosuppressive effects.83, 84 Sun et al. coated the IDO inhibitor NLG919 and DOX to a redox-responsive immunostimulatory polymeric prodrug carrier. The nanosystem generated greater accumulation of NLG and DOX in tumor tissue than other organs, promoted apoptosis of breast and prostate cancer cells, and formed a more significant immunoactivation effects compared with free DOX, liposomal DOX or free NLG groups.85 Other similar studies are also in consistent with the reported results.86, 87

Targeted delivery of nanoparticles to lymph nodes and immune cells

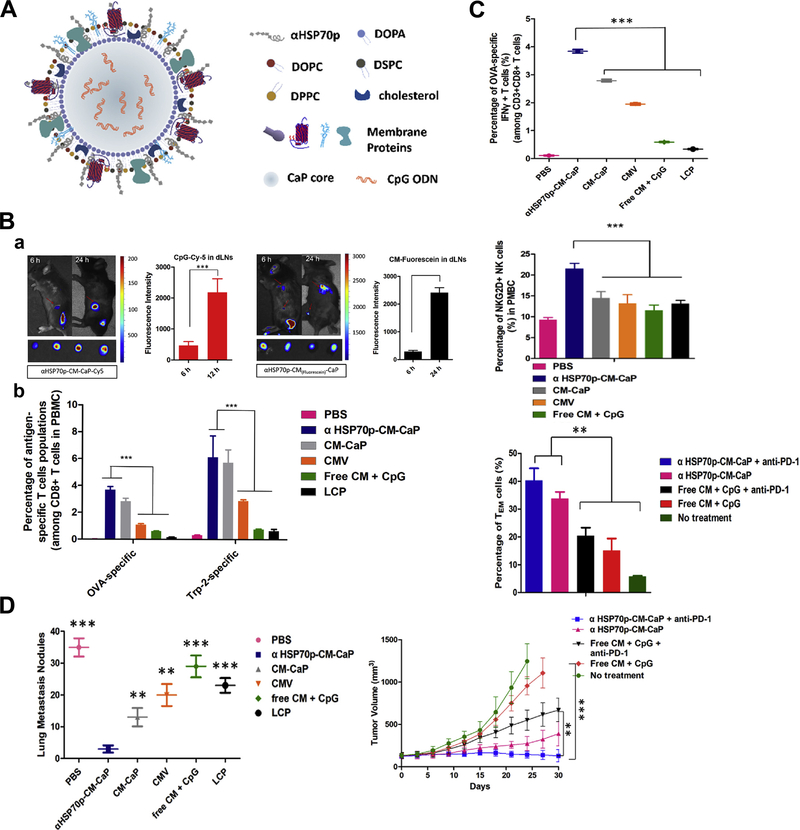

Tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs), which majorly constitute of tumor specific T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes and APCs, locate along the tumor-draining lymphatic channels.88, 89 TDLN plays a crucial role in cellular and humoral immunity against cancer as it is antigen-encountered through drainage of TAAs, but it is often immune-suppressed.90–92 As nanoparticle has the potential for efficient draining and retention in TDLN because of its size and particular structure which resembles pathogens, its potential effects to intensify activation and proliferation of APCs in TDLN as the immuno-stimulatory agents have been studied by recent experiments. Jeanbart et al coated both adjuvant and TAA to form a nanosystem, and delivered it to TDLN and non-TDLN of tumor-bearing mice.93 They found that the nanosystem delivered to TDLN induced substantially stronger cytotoxic CD8+ T-lymphocyte response both locally and systemically than the non-TDLN group, leading to tumor regression and longer survival period. Nanoparticle coupling both adjuvant and antigen is necessary for the effective TDLN stimulation, and this delivering method could dramatically enhance the antigen presentation process of TDLN APCs, thus increasing the therapeutic efficacy. Similar results were also found by Kang et al that nanoparticles co-delivering tumor membrane antigens, DAMPs signal-augmenting element α-helix HSP70 functional peptide (αHSP70p) and CpG exhibited efficient TDLN trafficking, inducing not only tumor-specific T-lymphocyte response, but also nature killer cells’ immune stimulation and effector memory T cells’ proliferation (Figure 5).94 The distinguishing between the metastatic TDLN, the TDLN that has been colonized by metastatic tumor cells, and non-metastatic TDLN is very important for surgical resection and prognosis evaluation, and Cao et al found folate receptor-targeted trimodal polymer nanoparticle was efficient for the rapid and precise diagnosis of lymph node metastasis in vivo.95 The folate-functionalized nanoparticle was coated with PFBT, NIR775 and DTPA-BSA (Gd) for the near-infrared, photoacoustic and magnetic resonance imaging. The results showed the nanoparticle rapidly accumulated in metastatic lymph nodes, which could effectively detect and distinguish metastatic lymph nodes at 1h post-injection, and had excellent potential in real-time image-guided surgery.

Figure 5.

Tumor draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) targeted nanoparticle boosts tumor-specific T-lymphocyte response, nature killer cells’ immune stimulation and effector memory T cells’ proliferation. (A) Structure of the TDLNs targeted nanoparticle that enables co-delivery of three elements including tumor cell membrane proteins, adjuvant CpG and an a-helix peptide modified HSP70p. (B) Prolonged antigen delivery in TDLNs and multi-epitope T cells priming in vivo: a. Fluorescence showing nanoparticle accumulation in the TDLNs and the corresponding fluorescence intensity; b. Quantitative analysis of the frequency of the nanoparticle positive CD8α+ T cells in the TDLNs after treatment. (C) The nanoparticle activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, NKG2D+ NK cells, and induced effector memory T cells proliferation in vivo. (D) Elimination of primary and secondary tumor by the nanoparticle. Figures from reference 94 with permission obtained.

Besides the TDLN, nanoparticles are also designed to target different types of immune cells, among which the DC is the most targeted cell as its prominent role in antigen processing and presentation. The DCs target is implemented by integrating ligands that combine to the membrane receptors on DCs, including the mannose, CD40, CD11c, DEC205 and DC-SIGN receptors. Studies found that the DC-targeted nanosystem could reinforce the endocytosis of DCs compared with the free form without nanoparticles.96–100 Wang et al conjugated mannose on the lipid-calcium-phosphate nanoparticles and found improved DC engulfment in the targeting-delivered group.101 As a result, the co-encapsulated PD-L1 siRNA resulted in down-regulation of PD-L1 in DCs that presented tumor antigens, further significantly prompted T cell activation and proliferation, and exhibited profound inhibitory effect on tumor growth and metastasis. Similar results were reported in another study by Liu et al.102 In addition, targeting different molecules on DC seemed to have different DC stimulation efficacy. Cruz et al observed a small but significantly enhanced internalization of CD40-targeted nanoparticle in comparison to CD11c or DEC-205 targeted nanoparticle, however, all the three targeted methods showed similar capacity to prime cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and subsequently induced tumor cell lysis.103 Different subsets of DCs had diverse specific functions and antigen presentation abilities based on types of immune responses and pathogens, however, no studies have been done concerning the immunity stimulation effects achieved by nanoparticles targeting the different subsets of DCs.

T-lymphocytes could also be targeted by the nanoparticles. Schmid et al targeted CD8+ T-lymphocytes using PD-1 antibody after removing the Fc fragments and combing to PLGA nanoparticle.104 Meanwhile, inhibitor of TGF-β which assist in immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment maintenance and immune adjuvants TLR7/8 agonists were also coated by the nanoparticle. The PD-1 positive T-lymphocytes were successfully targeted in blood and tumor tissue, and the TGF-β inhibitors and TLR7/8 agonists enhanced the immune responses, sensitized tumor to subsequent anti-PD-1 treatment and raised the proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T-lymphocytes, converting a “cold” tumor into a “hot” tumor, and extended the survival of mice in comparison to non-targeting compounds. In addition, they also found that by loading the drugs into targeted particles, the dose required decreased to less than one-tenth of the standard dose, thus mitigating potential toxicity.

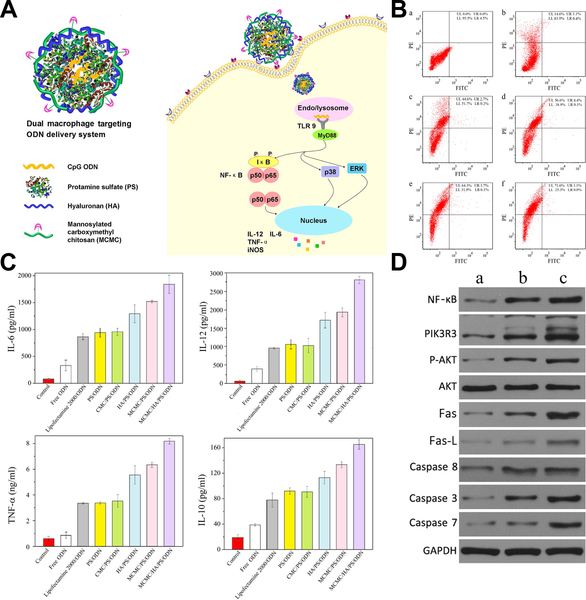

He et al developed a macrophage dual-targeted CpG-loading nanoparticle realized by mannosylated carboxymethyl chitosan (MCMC) and hyaluronan (HA), which resulted in a considerable shift of macrophages to activated M1 types and a significantly enhanced secretion of proinflammotory cytokines.105 Besides, the nanosystem also activated NF-κB and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signal pathways and induced Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer models (Figure 6). Cross-linking of B-lymphocyte receptors is the initiation of B-cell proliferation and differentiation to plasma cells secreting specific antibodies. In another study, biodegradable calcium phosphate nanoparticles decorated with model antigen hen egg lysozyme were preferentially bound and internalized by the tumor antigen specific B-lymphocytes, subsequently enhanced the surface expression of B-cell activation markers, and induced high humoral immunity, which was found to be approximately 100-fold more efficient in the activation of B-cells than the soluble form of tumor antigen.106

Figure 6.

Macrophage dual-targeted nanoparticle for overcoming cancer-associated immunosuppression. (A) Structure of the dual-targeting delivery system inducing immunological stimulation in macrophages. (B) Flow cytometry showing shift of macrophage to activated M1 type that marked by CD80 (a. without treatment, and treated by b. naked nanoparticle, c. nontargeting system, d. mono-targeting system with HA, e. mono-targeting system with MCMC, and f. dual-targeting system with HA and MCMC. (C) Enhanced cytokines secretion of macrophage after being treated. (D) Western blot analysis showing activated NF-κB, PI3K/Akt and Fas/FasL signaling pathways after treatment (a. without treatment, b. treated by naked nanoparticle, and c. treated by dual-targeting system). Figures from reference 105 with permission obtained.

Nanoparticles influencing tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy enhancement

Tumor microenvironment refers to the surrounding complex scaffold around tumor cells, which is composed of extracellular matrix, various signaling molecules, blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts and bone marine-derived inflammatory cells.107 Tumor cells were closely related to the surrounding microenvironment, by releasing cellular signaling molecules and interact with immune and other related cells, tumor can influence the microenvironment to further promote the angiogenesis and induce immune tolerance.108, 109 It has been reported that the extracellular matrix within the tumor microenvironment could play inhibitory roles to the adaptive anti-tumor immune response by inhibiting tumor specific T-lymphocytes proliferation through type I collagen ligation of LAIR receptors, and T-lymphocytes activation from its naive state.110 In addition, the abnormal tumor microenvironment could also provide critical biochemical and biomechanical cues to direct tumor cell growth, survival, proliferation and migration, and suppress anti-tumor immunity function through suppressive cytokines releasing, cellular interaction, hypoxia condition, and hemodynamic obstruction of immunocytes.111, 112 Thus, the regulation of the abnormal tumor microenvironment could largely relieve the inhibitory effects on the anti-tumor immunity and further increase therapeutic effects of immunotherapy. On the other hand, the tumor-specific stimuli in the abnormal tumor microenvironment including hypoxia, specific protease or proteins, and abnormal extracellular pH condition could also be utilized to give nanoparticles the special conditions to accumulate and orientating-release of payloads, thus achieving the regulation of tumor microenvironment and enhancement of immunotherapy effects.

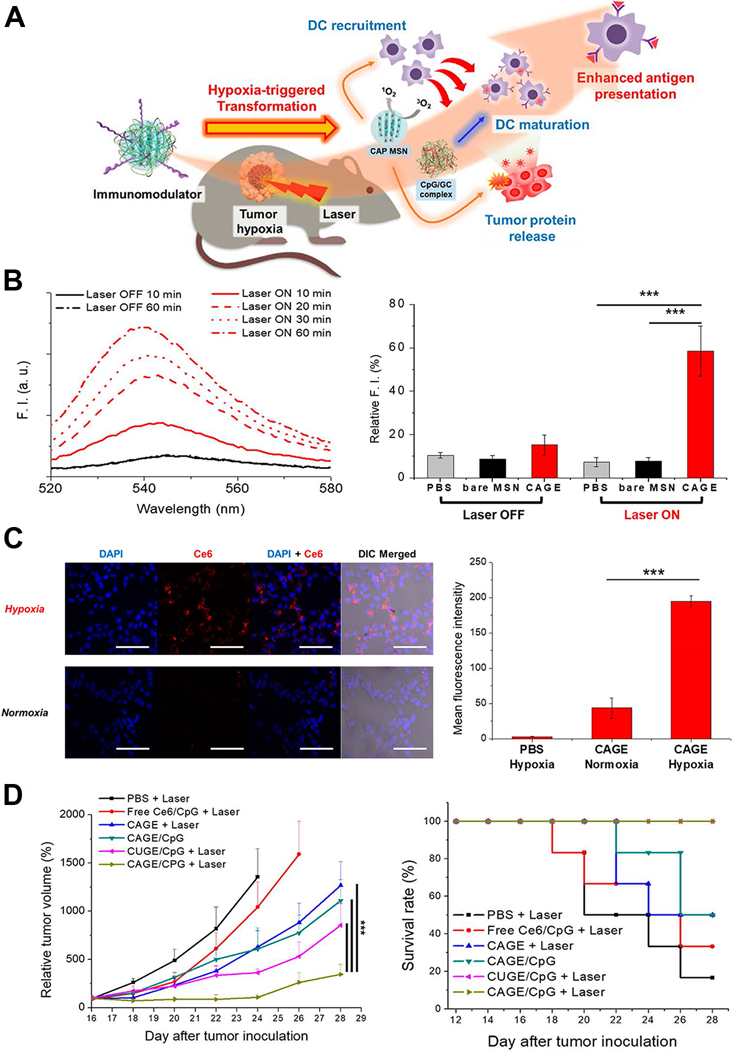

Hypoxia was a common utilized tumor-specific condition for nanoparticle design with hypoxia-responsive chemical constructions coated, as the hypoxia in tightly associated with immune suppressive tumor microenvironment and it is also a rare condition in normal tissues.113–115 The hypoxia environment could induce the polarization of macrophages from the immunosupportive M1 type to immunosuppressive M2 type, and was also responsible for recruitment of abundant regulatory T cells and releasing of immunosuppressive cytokines.116, 117 Im et al developed a photodynamic agent Chlorin e6 (Ce6)-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticle with azobenzene used as the hypoxia-sensitive feasible cross-linker, which is also coated with CpG/GC complex as the immune adjuvants.118 When the nanoparticles reached a hypoxic region within tumor tissue, the azobenzene cross-linkers were cleaved, and silica-core and CpG/GC complex were released, leading to delivery of CpG for DCs engulfment and activation. The authors also generate photodynamic therapy to induce both tumor cell death and recruit DCs to facilitate the release of tumor associated antigens and the uptake of DCs. (Figure 7) The nanoparticles combined with photodynamic therapy significantly enhanced the anti-tumor immune response and inhibited tumor growth in vivo. Yang et al produced hollow manganese dioxide nanoparticles coated with PEG, Ce6 and DOX, which could be dissociated under reduced pH microenvironment, hence releasing therapeutic drugs and meanwhile causing degradation of endogenous hydrogen peroxide to relieve intratumoral hypoxia.119 A remarkable synergistic effect of the nanoparticle with photodynamic therapy was achieved through intensifying the anti-tumor immune responses. Moreover, the additional combination of the therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors led to the ablation of distant tumor metastasis.

Figure 7.

Hypoxia microenvironment-triggered transforming nanoparticles for cancer immunotherapy via photodynamically enhanced antigen presentation. (A) Schematic illustration of working mechanism of the hypoxia-triggered transforming nanoparticle combined with photodynamic therapy. (B) Photoresponsive generation of singlet oxygen and the release profile of tumor proteins. (C) Hypoxia-responsive internalization of the nanoparticles into cells under hypoxic or normoxic conditions and the corresponding fluorescence intensity. (D) In vivo inhibition of tumor growth by the nanosystem and the survival curves. Figures from reference 118 with permission obtained.

The abnormal tumor vasculature featured with heterogenous vessel diameter, tortuosity and distribution, and insufficient blood and oxygen supply, is closely correlated with hypoxia, reduced pH and immune suppressive features within the tumor microenvironment.120 As a result, normalization of tumor vasculature could be a way to enhance anti-tumor immunity.121 Accompanied with oral treatment of Erlotinib, an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Chen et al found the tumor uptake of immunostimulatory drug-loaded nanoparticles was significantly increased, and the combined therapy dramatically relieved hypoxia status and alter the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment into immunosupportive in three types of tumor models.122 The combined treatment also increased the tumor retention of anti-PD-L1 antibody, thus further inhibiting tumor growth and enhancing the treatment efficacy of anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. On the other hand, the inhibition of copper trafficking could also have antiangiogenesis effects, as copper was required for the secretion of several angiogenic factors and stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation.123, 124 Zhou et al used copper chelating coil-comb block copolymer, which has strong copper-chelating ability, to compose nanoparticle and conjugated it with TLR7/8 agonists and an immunomodulator Resiquimod.125 The nanoparticle exhibited accelerated releases in reduced pH tumor microenvironment, displayed targeting ability and dramatically suppressed tumor growth in primary breast tumor and lung metastasis lesions, demonstrating considerable anti-tumor immune enhancement effects.

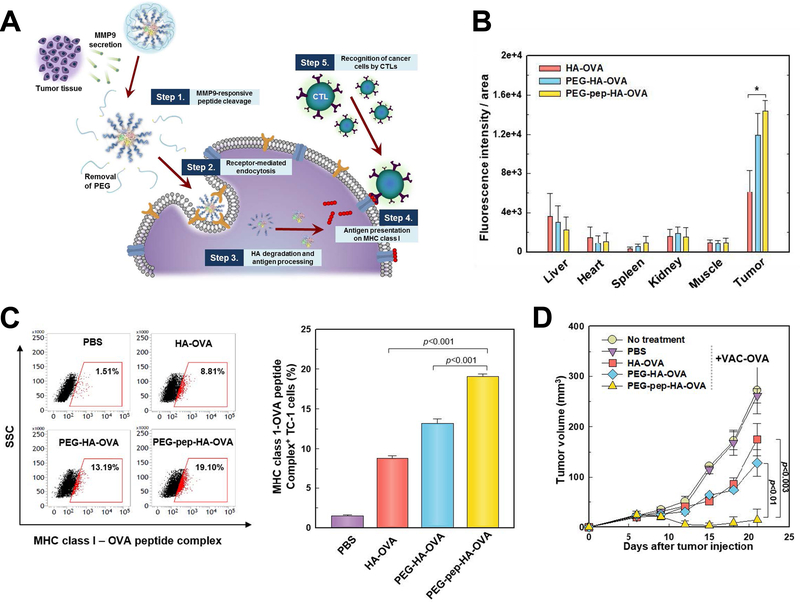

The relevant microenvironmental characteristics to differentiate malignancy from normal tissues also included specific enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), which functioned in degrading extracellular matrix and assisted in carcinogenesis, tumor progression and metastasis, and its level is also found to be proportional to the malignancy of cancer.126–128 As a result, MMPs were harnessed as the key to trigger fragmentation of nanostructures and the release of payloads. Shin et al used MMP9-cleabable linker to trigger the detachment of PEG corona in the tumor tissue, and this method significantly enhanced CD44 receptor-mediated endocytosis of nanoparticles, facilitated antigen presentation and inhibited tumor growth.129 (Figure 8) In another study, CpG DNA and anti-PD1 antibody were controlled released from nanoparticles in tumor tissue through MMP9-dissociation method, and subsequently considerable immune responses were induced, and the risk of tumor relapse and metastasis after primary tumor resection was significantly reduced.130

Figure 8.

MMP9 responsive nanoparticle in enhancing cancer immunotherapy. (A) Schematic illustration depicting working mechanism of the MMP9 responsive polymeric nanoparticle. (B) MMP9 responsive polymeric nanoparticle effectively accumulated in tumor tissue after systemic administration. (C) In vivo OVA antigen presentation in tumor cells after nanoparticle treatment. (D) In vivo therapeutic efficacy of the nanoparticle in tumor bearing mice. Figures from reference 129 with permission obtained.

In addition, redox-sensitive-based delivery strategy was often utilized as an effective way to controlled release drugs into the tumor microenvironment. Generally, the nanoparticles contained redox-responsive disulfide bonds that could be degraded by intracellular glutathione. Along with reduction of the disulfide bonds, antigens could be released from the nanoparticle carrier and be cross-presented to induce cellular immunity.131, 132 Xu et al developed a redox-responsive nanoparticle platform and found it had satisfactory features of long blood circulation, high tumor accumulation, fast payloads releasing, and effective therapeutic effects.133 Wang et al combined cell-penetrating peptides and redox-responsive disulfide bond cross-linking to designed peptide carriers to form antigen delivery nanoparticles.134 The results showed the redox-responsive nanoparticles could significantly induce antigen-specific immune response by significantly increasing IgG titer and levels of cytokines including INF-γ, IL-12, IL-4, and IL-10, simulating splenocyte proliferation and APCs maturation, and could also enhance the immune memory function.

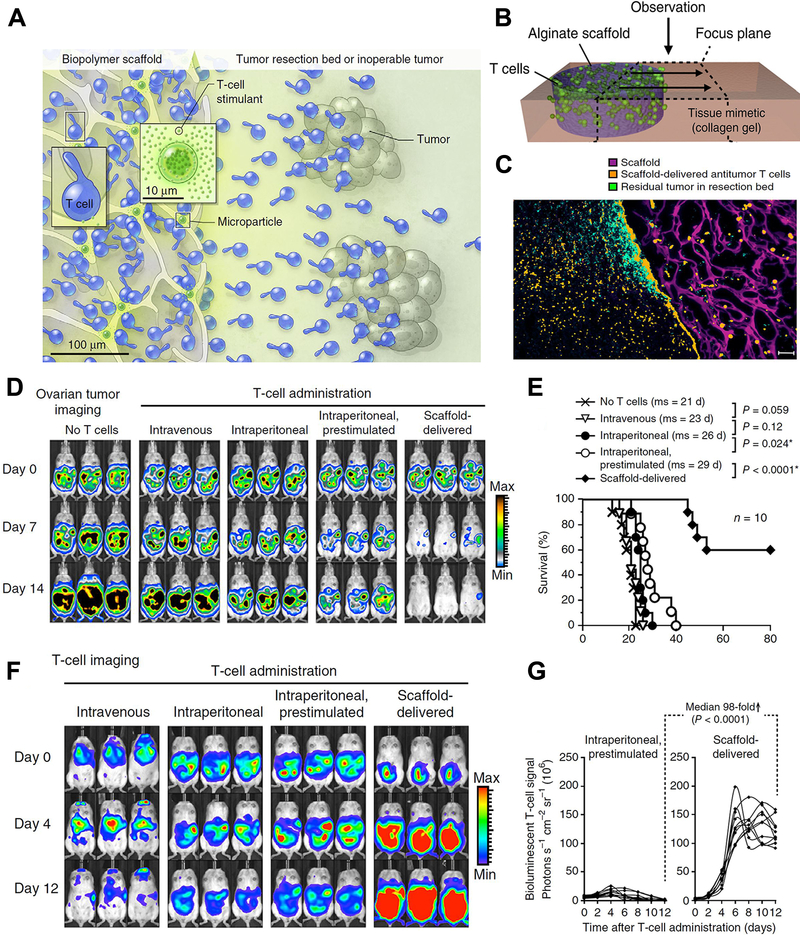

Nanoparticles in enhancing adoptive cell therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is a crucial part of cancer immunotherapy, in which tumor-specific lymphocytes are isolated either from peripheral blood or tumor biopsies in patients, and then selected to recognize specific tumor antigens, or alternatively, polyclonal peripheral T-cells are artificially gene-modified to process desired tumor-targeting ligands. Then the cells are stimulated and expanded ex vivo, and finally infused back into patients.135–137 However, the therapeutic effects of ACT are impaired by insufficient ex vivo proliferation, inefficient trafficking of infused lymphocytes, and inadequate T-cell activity in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment due to immunosuppressive chemokines and abnormal tumor vasculature.138, 139 Accompanied with specific designed nanoparticles, these limitations of ACT could be significantly altered. Targeting the lymphocytes with nanoliposomes conjugated with inhibitor of TGF-β, an important immunosuppressive chemokine, prior to adoptive therapy could dramatically activate T-cell proliferation ex vivo and induced tumor regression after refusion.140 Stephan et al developed poly-alginate microporous scaffolds which loaded with proliferated T cells and VEGF antibody. After placing the scaffolds in tumor resection sites or close to inoperable tumors, the polymer could act as reservoir for T-cell propagating and releasing, and the VEGF antibody could normalize tumor vasculature, assisting in T-cell infiltration and altering immunosuppressive microenvironment. As a result, the polymer successively supported tumor-targeting T-lymphocytes throughout tumor resection beds and the draining lymph nodes, and inhibited tumor relapse, whereas the conventional delivery modalities or injection of tumor-targeting lymphocytes have limited therapeutic effects.141 (Figure 9)

Figure 9.

Nanostructured polyporous scaffold implants enhanced efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy. (A, B) Schematic diagram of the T cell-loaded scaffold surgically situated at a tumor site. Stimulatory microspheres incorporated into the device triggered cell expansion and promoted their egress into surrounding tissue. (C) Histological analysis of the scaffold and surrounding tissue 3 days after tumor-specific T cells (Orange) were embedded in the scaffold (Purple) and implanted into the tumor resection cavity. (D) Serial in vivo bioluminescence imaging of tumors. (E) Survival curves of tumor bearing mice following T-cell adoptive therapy. (F) In vivo bioluminescent imaging of T cells expressing luciferase. (G) Luciferase signal intensities after T-cell transfer, every line represented one animal and each dot reflected the whole animal photon count. Figures from reference 141 with permission obtained.

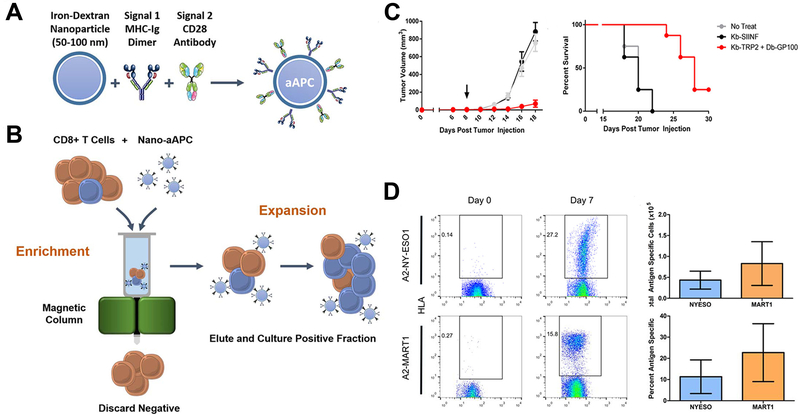

Nanoparticles could also act on the ex vivo T-cell proliferation to the required quality, and reduce the time interval between cell acquiring and infusion. Integrin of T-lymphocytes had a crucial role in sustaining the immunological synapse with APCs through its binding to intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and the formation of immunological synapse led to reorganization of the cytoskeleton, which facilitate clustering and prevent migration of T-cells.142–144 Cuasch et al created a nanoparticle that cross-linked with peptides derived from fibronectin, an integrin signaling activator, and found it was significantly more efficient in stimulating T-cells proliferation and increasing the expansion rate compared with nonfunctionalized nanoparticle.145 Perica et al integrated paramagnetic iron-dextran nanoparticle with MHC-Ig dimer as the signal 1 and CD28 antibody as the signal 2 to form an artificial APC.146 The nano-artificial APCs could selectively bind to antigen-specific T-lymphocytes rare naive precursors, and retained in a magnetic column, thus achieving cell enrichment, followed by activating of the selected T-cells leading to rapid proliferation and expansion. The enrichment and expansion processes resulted in greater than 1000-fold proliferation of mouse and human antigen-specific T-lymphocytes in one week. The nano-artificial APCs could not only enhance T-cell proliferation in vivo culture but also after adoptive transfer, leading to robust T-cell response. (Figure 10)

Figure 10.

Enrichment and expansion with nano-artificial APCs for adoptive cell immunotherapy. (A) Nano-artificial APCs are synthesized by coupling MHC-Ig dimer (Signal 1) and anti-CD28 antibody (Signal 2) to a 50–100 nm iron-dextran nanoparticle. (B) Schematic of magnetic enrichment. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (blue) bound to the nano-artificial APC are retained in a magnetic column in the enrichment step, while non-cognate (orange) cells are less likely to bind. Enriched T cells are then activated by the nano-artificial APC and proliferate in the expansion step. (C) Nano-artificial APCs enriched and expanded lymphocytes inhibited melanoma growth after adoptive transfer. (D) Enrichment and expansion with the nano-artificial APC functionalized with human HLA-A2 and induced robust expansion against the tumor antigens. Figures from reference 146 with permission obtained.

Conclusion, Challenges and Perspective

Nanoparticle combined immunotherapy is at the initial stage of exploitation, but tremendous potential of the approach could be clearly witnessed. Compound nanoparticles have been developed in researches as vehicles for concerted delivery of tumor antigens as vaccination and/or immune stimulatory adjuvants to DCs or other professional APCs. Nanoparticles carrying whole-cell tumor vaccines have multiple antigen immunity and could potentially stimulate cellular and humoral immune responses. Generally, in comparison with the traditional, non-nanoparticle combined tumor antigen vaccines, the nanoparticle loaded approaches could induce significantly stronger antigen-specific antibody responses and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against cancer cells and efficaciously inhibited tumor growth. Based on the inherent physical properties of nanoparticles or the conjugation with targeted ligands, targeting transportation of tumor antigens or adjuvants to TDLNs or specific immune cells such as DCs, T-lymphocytes and macrophages could be realized, thus further enhancing the immune stimulatory effects. In addition, combination of the compound nanoparticles with molecules of immune checkpoint inhibitor or photodynamic therapy could complement with each other and more efficiently suppress tumor proliferation at the primary and metastatic sites. Nanoparticles with specific features could also controlled release payloads in response to typical conditions in tumor microenvironment including hypoxia, specific protease and decreased pH condition, and further alter the immunosuppressive microenvironment into immunosupportive features. Adoptive cell therapy could also be supported by nanoparticle approaches in the aspects of enhancing ex vivo T-cell proliferation, recovering abnormal microenvironment, and intensifying the trafficking and activity of infused lymphocytes.

Despite the impressive benefits of nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy, there are still challenges that need to be treated with caution and investigated in future studies. At first, the delivery ability of nanoparticles to the intended tissues or organs still needs to be strengthened. Currently, nanoparticles can only deliver a small portion of the administrated payloads to the intended locations even with targeted ligands coated, which leads to the loss of delivered drugs and systemic cytotoxicity due to normal cell uptake of the nanoparticles. According to Harrington et al’ study including 17 patients with different types of locally advanced cancers, only less than 4% of the total administrated dose could be accumulated in tumor tissues using pegylated liposome as the delivery method.28 In addition, considerable heterogeneity of uptake both between different tumor types and between different patients with the same tumor type was also observed, mainly caused by the various tumor vascular conditions.28 Similarly, because of the poor vascularization, small metastatic lesions, especially the micro-metastases, and the core of large tumors where usually exists hazardous dormant cancer cells generally have ineffective nanoparticle accumulation. Other nanoparticles uptaken by normal cells can cause toxicity including oxidative stress, pulmonary inflammation, and disfunction of cells and organs through mechanisms of redox cycling, free radical formation and hydrophobic interaction.147, 148

For the nanoparticles delivering payloads to the immune organs and cells, as they need to be transported in blood circulation and lymph vessels before reaching the targeted sites, the structural and colloidal stability is crucial to grantee their final drainage into the immune organs and present payloads to immune cells.40 Unstable nanoparticles may form micrometer-sized aggregates that could plug capillary bed of distal organs and cause serious complications to patients. Another challenge is how to efficiently regulate components within the whole immune system by the nanoparticles to optimize the enhancement effects on anti-tumor immunity. The innate and adaptive immune system works in a network, but currently, little is known about how the other immune components in the immune network are affected to influence the whole anti-tumor immunity when the intended component is regulated by the administrated nanoparticles. Future efforts are still needed to investigate the inter-regulation mechanisms of immune components to maximize treatment effects of the nanoparticles.

Potential immunogenicity of nanoparticles is another crucial concern towards progresses in clinical translations. In fact, the utilization of nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy is based on the immunogenicity or the immune adjuvant effects of nanoparticles or the attached peptides, proteins or antibody fragments, but it could be detrimental if immune response against un-intended components is activated. Nanoparticles can be antigenic themselves, and if the nanoparticles are recognized as foreign substances and opsonized by plasma protein, complement pathway will be activated, resulting in rapid phagocytosis and clearance in liver and spleen. Complete activation of immune response against nanoparticles may lead to serious complications including allergic reactions, hemolysis, thrombogenesis, and even disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).149, 150 More importantly, when nanoparticles are applied in enhancing anti-tumor immunity, immune checkpoint inhibitors are often conjugated to the nanoparticles or systematically administrated to form an syncretistic treatment effects. However, one major risk of the immune checkpoint inhibitors is that the drugs can induce serious autoimmune diseases. As a consequence, the simultaneously administrated nanoparticles for future clinical translations should be developed in weak antigenicity with strictly controlled dose used, and the patients should be observed with caution as they are theoretically in higher risks of the complications.

Collectively, clinical application of the nanoparticles combined immunotherapy needs the optimization of nanostructures to overcome the several existing disadvantages including the insufficient targeted delivery capacity, systemic cytotoxicity due to normal cell’s engulfment and the potential immunogenicity, and it will be crucial to ascertain the optimal physical and chemical properties of the nanoparticles in future investigations. It has been shown that the diameter of nanoparticles less than 100 nm displayed the most suitable surface chemistries, which could enable long-distance transportation within immune organs, strengthening internalization by immune cells, but other characteristics including the surface charge, shape, elasticity, hydrophilicity, ligands, and loading methods of encapsulating or conjugating payloads are still need to be researched and determined to further improve the pharmacokinetics, toxicity, biocompatibility and biodistribution of the nanoparticles.

Only a small proportion of patient could achieve satisfactory survival after receiving one modality of immunotherapy, and there is a growing common view that combination of tumor vaccines with immune checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive T-cell therapy or tumor microenvironment regulatory treatments could form synergistic effects on inhibiting primary and abscopal tumor lesions. As a consequence, developing pleuripotent nanoparticles that integrate the multiple immunotherapy ingredients with targeted delivering and triggered releasing ability may could potentially attain comprehensive anti-tumor immunity enhancement and improved treatment effects. With further advances of nanotechnology and deeper understanding of interactions between nanomaterials and immune system, the nanomedicine combined immunotherapy could be further consummated to achieve more effective therapeutic benefits.

Acknowledgment:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff in the Krishnan Lab at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for the valuable suggestions on the manuscript. The manuscript is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Translational Cancer Nanotechnology Postdoctoral Fellowship grant T32CA196561.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mora J, Mertens C, Meier JK, Fuhrmann DC, Brune B and Jung M, Cells, 2019, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD and Smyth MJ, Annu Rev Immunol, 2011, 29, 235–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith HJ, McCaw TR, Londono AI, Katre AA, Meza-Perez S, Yang ES, Forero A, Buchsbaum DJ, Randall TD, Straughn JM Jr., Norian LA and Arend RC, Cancer, 2018, 124, 4657–4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakasone ES, Hurvitz SA and McCann KE, Drugs Context, 2018, 7, 212520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougan M and Dranoff G, Annu Rev Immunol, 2009, 27, 83–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D and Weinberg RA, Cell, 2011, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marquez-Rodas I, Aznar MA, Calles A and Melero I, Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 25, 1127–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Yao C, Ding L, Li C, Wang J, Wu M and Lei Y, J Biomed Nanotechnol, 2017, 13, 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kieber-Emmons T, Monzavi-Karbassi B, Hutchins LF, Pennisi A and Makhoul I, Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2017, 13, 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, Nam GH, Kim GB, Kim YK and Kim IS, Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2019, DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotfi R, Eisenbacher J, Solgi G, Fuchs K, Yildiz T, Nienhaus C, Rojewski MT and Schrezenmeier H, Eur J Immunol, 2011, 41, 2021–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen DS and Mellman I, Immunity, 2013, 39, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashireva LA, Perelmuter VM, Manskikh VN, Denisov EV, Savelieva OE, Kaygorodova EV and Zavyalova MV, Biochemistry (Mosc), 2017, 82, 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarafdar A, Hopcroft LE, Gallipoli P, Pellicano F, Cassels J, Hair A, Korfi K, Jorgensen HG, Vetrie D, Holyoake TL and Michie AM, Blood, 2017, 129, 199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guirgis HM, J Immunother Cancer, 2018, 6, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs JF, Idema AJ, Bol KF, Nierkens S, Grauer OM, Wesseling P, Grotenhuis JA, Hoogerbrugge PM, de Vries IJ and Adema GJ, Neuro Oncol, 2009, 11, 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha P, Clements VK, Miller S and Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2005, 54, 1137–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrilovich DI and Nagaraj S, Nat Rev Immunol, 2009, 9, 162–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goswami KK, Ghosh T, Ghosh S, Sarkar M, Bose A and Baral R, Cell Immunol, 2017, 316, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickup MW, Mouw JK and Weaver VM, EMBO Rep, 2014, 15, 1243–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott PA, Hodi FS and Robert C, Clin Cancer Res, 2013, 19, 5300–5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, Khan N, Wang Z, Boyce L and Korenstein D, BMJ, 2018, 360, k793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu R, Forget MA, Chacon J, Bernatchez C, Haymaker C, Chen JQ, Hwu P and Radvanyi LG, Cancer J, 2012, 18, 160–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsuiki N, Schwab C and Grimbacher B, Immunol Rev, 2019, 287, 33–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribas A and Wolchok JD, Science (New York, N.Y.), 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cha JM, You DG, Choi EJ, Park SJ, Um W, Jeon J, Kim K, Kwon IC, Park JC, Kim HR and Park JH, J Biomed Nanotechnol, 2016, 12, 1724–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S, McLean JW, Thurston G, Roberge S, Jain RK and McDonald DM, Am J Pathol, 2000, 156, 1363–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington KJ, Mohammadtaghi S, Uster PS, Glass D, Peters AM, Vile RG and Stewart JS, Clin Cancer Res, 2001, 7, 243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasir JK and Labhasetwar V, Technol Cancer Res Treat, 2005, 4, 363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petros RA and DeSimone JM, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2010, 9, 615–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Wang D, Fu Q, Liu D, Ma Y, Racette K, He Z and Liu F, Mol Pharm, 2014, 11, 3766–3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanco E, Shen H and Ferrari M, Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33, 941–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjaminsen RV, Mattebjerg MA, Henriksen JR, Moghimi SM and Andresen TL, Mol Ther, 2013, 21, 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan YY, Mao CQ, Du XJ, Du JZ, Wang F and Wang J, Adv Mater, 2012, 24, 5476–5480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu J, Owen SC and Shoichet MS, Macromolecules, 2011, 44, 6002–6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terry S, Savagner P, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Mahjoubi L, Saintigny P, Thiery J and Chouaib S, Mol Oncol, 2017, 11, 824–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beatty G and Gladney W, Clin Cancer Res, 2015, 21, 687–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Y, Yang Y, Gu Z, Zhang J, Song H, Xiang G and Yu C, Biomaterials, 2018, 175, 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan S, Gu W, Zhang B, Rolfe BE and Xu ZP, Dalton Trans, 2018, 47, 2956–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang LX, Xie XX, Liu DQ, Xu ZP and Liu RT, Biomaterials, 2018, 174, 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yata T, Takahashi Y, Tan M, Nakatsuji H, Ohtsuki S, Murakami T, Imahori H, Umeki Y, Shiomi T, Takakura Y and Nishikawa M, Biomaterials, 2017, 146, 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Courant T, Bayon E, Reynaud-Dougier HL, Villiers C, Menneteau M, Marche PN and Navarro FP, Biomaterials, 2017, 136, 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang C, Shi G, Zhang J, Song H, Niu J, Shi S, Huang P, Wang Y, Wang W, Li C and Kong D, J Control Release, 2017, 256, 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sokolova V, Shi Z, Huang S, Du Y, Kopp M, Frede A, Knuschke T, Buer J, Yang D, Wu J, Westendorf AM and Epple M, Acta Biomater, 2017, 64, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu L, Wang Y, Miao L, Liu Q, Musetti S, Li J and Huang L, Mol Ther, 2018, 26, 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson RM, Casey LM, Hughes KR, Wang LZ, North MG, Getts DR, Miller SD and Shea LD, Mol Ther, 2017, 25, 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verbeke R, Lentacker I, Wayteck L, Breckpot K, Van Bockstal M, Descamps B, Vanhove C, De Smedt SC and Dewitte H, J Control Release, 2017, 266, 287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi H, Misato K, Aoshi T, Yamamoto Y, Kubota Y, Wu X, Kuroda E, Ishii KJ, Yamamoto H and Yoshioka Y, Front Immunol, 2018, 9, 783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshizaki Y, Yuba E, Sakaguchi N, Koiwai K, Harada A and Kono K, Biomaterials, 2017, 141, 272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang X, Duan J, Li X, Zhu X, Chen Y, Wang X, Sun H, Kong D, Li C and Yang J, Nanoscale, 2018, 10, 9489–9503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu M, Chen Y, Banerjee P, Zong L and Jiang L, AAPS PharmSciTech, 2017, 18, 2618–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long W, Wang J, Yang J, Wu H, Wang J, Mu X, He H, Liu Q, Sun YM, Wang H and Zhang XD, J Biomed Nanotechnol, 2019, 15, 62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zom G, Willems M, Khan S, van der Sluis T, Kleinovink J, Camps M, van der Marel G, Filippov D, Melief C and Ossendorp F, J Immunother Cancer, 2018, 6, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seliger B, Massa C, Rini B, Ko J and Finke J, Trends Mol Med, 2010, 16, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ebrahimian M, Hashemi M, Maleki M, Hashemitabar G, Abnous K, Ramezani M and Haghparast A, Front Immunol, 2017, 8, 1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo Z, Wang C, Yi H, Li P, Pan H, Liu L, Cai L and Ma Y, Biomaterials, 2015, 38, 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexander AN, Huelsmeyer MK, Mitzey A, Dubielzig RR, Kurzman ID, Macewen EG and Vail DM, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2006, 55, 433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen M, Xiang R, Wen Y, Xu G, Wang C, Luo S, Yin T, Wei X, Shao B, Liu N, Guo F, Li M, Zhang S, Li M, Ren K, Wang Y and Wei Y, Sci Rep, 2015, 5, 14421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang R, Xu J, Xu L, Sun X, Chen Q, Zhao Y, Peng R and Liu Z, ACS Nano, 2018, 12, 5121–5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fang RH, Hu CM, Luk BT, Gao W, Copp JA, Tai Y, O’Connor DE and Zhang L, Nano Lett, 2014, 14, 2181–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kroll AV, Fang RH, Jiang Y, Zhou J, Wei X, Yu CL, Gao J, Luk BT, Dehaini D, Gao W and Zhang L, Adv Mater, 2017, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen W, Zuo H, Li B, Duan C, Rolfe B, Zhang B, Mahony TJ and Xu ZP, Small, 2018, 14, e1704465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hodge JW, Garnett CT, Farsaci B, Palena C, Tsang KY, Ferrone S and Gameiro SR, Int J Cancer, 2013, 133, 624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Formenti SC and Demaria S, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012, 84, 879–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Q, Xu L, Liang C, Wang C, Peng R and Liu Z, Nat Commun, 2016, 7, 13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu J, Xu L, Wang C, Yang R, Zhuang Q, Han X, Dong Z, Zhu W, Peng R and Liu Z, ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 4463–4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boussiotis VA, N Engl J Med, 2016, 375, 1767–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim JM and Chen DS, Ann Oncol, 2016, 27, 1492–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santini FC and Hellmann MD, Cancer J, 2018, 24, 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu Y and Zheng P, Trends Immunol, 2018, 39, 953–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Callahan MK and Wolchok JD, Semin Oncol, 2015, 42, 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng N, Watkins-Schulz R, Junkins RD, David CN, Johnson BM, Montgomery SA, Peine KJ, Darr DB, Yuan H, McKinnon KP, Liu Q, Miao L, Huang L, Bachelder EM, Ainslie KM and Ting JP, JCI Insight, 2018, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu W, Wang Y, Zhu J, Jin L, Liu B, Xia K, Wang J, Gao J, Liang C and Tao H, Biomaterials, 2019, 192, 128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu Y, Gu W, Li L, Chen C and Xu ZP, Nanomaterials (Basel), 2019, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu Y, Gu W, Li J, Chen C and Xu ZP, Nanomedicine (Lond), 2019, 14, 955–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang C, Ye Y, Hochu GM, Sadeghifar H and Gu Z, Nano Lett, 2016, 16, 2334–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y, Fang M, Zhang J, Wang J, Song Y, Shi J, Li W, Wu G, Ren J, Wang Z, Zou W and Wang L, Oncoimmunology, 2016, 5, e1074374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao P, Atanackovic D, Dong S, Yagita H, He X and Chen M, Mol Pharm, 2017, 14, 1494–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meir R, Shamalov K, Sadan T, Motiei M, Yaari G, Cohen CJ and Popovtzer R, ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 11127–11134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chae YK, Arya A, Iams W, Cruz MR, Chandra S, Choi J and Giles F, J Immunother Cancer, 2018, 6, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kuai R, Yuan WM, Son S, Nam J, Xu Y, Fan YC, Schwendeman A and Moon JJ, Sci Ad, 2018, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang D, Wang T, Liu J, Yu H, Jiao S, Feng B, Zhou F, Fu Y, Yin Q, Zhang P, Zhang Z, Zhou Z and Li Y, Nano Lett, 2016, 16, 5503–5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lob S, Konigsrainer A, Rammensee HG, Opelz G and Terness P, Nat Rev Cancer, 2009, 9, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sheridan C, Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33, 321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun JJ, Chen YC, Huang YX, Zhao WC, Liu YH, Venkataramanan R, Lu BF and Li S, Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2017, 38, 823–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang N, Wang Z, Xu Z, Chen X and Zhu G, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2018, 57, 3426–3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen Y, Xia R, Huang Y, Zhao W, Li J, Zhang X, Wang P, Venkataramanan R, Fan J, Xie W, Ma X, Lu B and Li S, Nat Commun, 2016, 7, 13443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takahashi A, Kono K, Ichihara F, Sugai H, Amemiya H, Iizuka H, Fujii H and Matsumoto Y, Int J Cancer, 2003, 104, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carriere V, Colisson R, Jiguet-Jiglaire C, Bellard E, Bouche G, Al Saati T, Amalric F, Girard JP and M’Rini C, Cancer Res, 2005, 65, 11639–11648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Munn DH and Mellor AL, Immunol. Rev, 2006, 213, 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Imai K, Minamiya Y, Koyota S, Ito M, Saito H, Sato Y, Motoyama S, Sugiyama T and Ogawa J, J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2012, 31, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Habenicht LM, Albershardt TC, Iritani BM and Ruddell A, Oncoimmunology, 2016, 5, e1204505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jeanbart L, Ballester M, de Titta A, Corthesy P, Romero P, Hubbell JA and Swartz MA, Cancer Immunol Res, 2014, 2, 436–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kang T, Huang Y, Zhu Q, Cheng H, Pei Y, Feng J, Xu M, Jiang G, Song Q, Jiang T, Chen H, Gao X and Chen J, Biomaterials, 2018, 164, 80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cao FW, Guo YX, Li Y, Tang SY, Yang YD, Yang H and Xiong LQ, Adv Funct Mater, 2018, 28. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cho NH, Cheong TC, Min JH, Wu JH, Lee SJ, Kim D, Yang JS, Kim S, Kim YK and Seong SY, Nat Nanotechnol, 2011, 6, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sehgal K, Ragheb R, Fahmy TM, Dhodapkar MV and Dhodapkar KM, J Immunol, 2014, 193, 2297–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang TZ, Stadmiller SS, Staskevicius E and Champion JA, Biomater Sci, 2017, 5, 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liang R, Xie J, Li J, Wang K, Liu L, Gao Y, Hussain M, Shen G, Zhu J and Tao J, Biomaterials, 2017, 149, 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang C, Zhang J, Shi G, Song H, Shi S, Zhang X, Huang P, Wang Z, Wang W, Wang C, Kong D and Li C, Mol Pharm, 2017, 14, 1760–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Y, Zhang L, Xu Z, Miao L and Huang L, Mol Ther, 2018, 26, 420–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu Q, Zhu H, Liu Y, Musetti S and Huang L, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2018, 67, 299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cruz LJ, Rosalia RA, Kleinovink JW, Rueda F, Lowik CW and Ossendorp F, J Control Release, 2014, 192, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]