Abstract

Precision and personalized medicine is gaining importance in modern clinical medicine, as it aims to improve diagnostic precision and to reduce consequent therapeutic failures. In this regard, prior to use in human trials, animal models can help evaluate novel imaging approaches and therapeutic strategies and can help discover new biomarkers. Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women worldwide, accounting for 25% of cases of all cancers and is responsible for approximately 500,000 deaths per year. Thus, it is important to identify accurate biomarkers for precise stratification of affected patients and for early detection of responsiveness to the selected therapeutic protocol. This review aims to summarize the latest advancements in preclinical molecular imaging in breast cancer mouse models. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging remains one of the most common preclinical techniques used to evaluate biomarker expression in vivo, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly diffusion-weighted (DW) sequences, has been demonstrated as capable of distinguishing responders from nonresponders for both conventional and innovative chemo- and immune-therapies with high sensitivity and in a noninvasive manner. The ability to customize therapies is desirable, as this will enable early detection of diseases and tailoring of treatments to individual patient profiles. Animal models remain irreplaceable in the effort to understand the molecular mechanisms and patterns of oncologic diseases.

1. Introduction

Precision or personalized medicine is becoming increasingly important in the fields of biomedical and clinical research. These two terms, personalized medicine and precision medicine, have been used interchangeably, although they describe different aspects of a common problem. Nonetheless, the shared aim of both personalized and precision medicine is to obtain an early and accurate diagnosis, predict disease evolution and therapy response, and reduce occurrence of therapeutic failures [1–5].

Preclinical imaging of animal models represents an invaluable tool in studying the etiopathogenesis of and therapeutic responses in various human pathologies [6]. In particular, molecular imaging techniques are important because they can be used to assess biological processes at the cellular and molecular levels, enabling detection of disease in very early or presymptomatic stages, and to estimate the efficacy of novel therapies, such as personalized, targeted, and combinational therapies [2, 7, 8]. The ability to study the same animal model of human disease using different techniques, i.e., with a multimodal approach, constitutes an additional advantage for both diagnosis and therapy. Preclinical imaging allows longitudinal studies to be conducted noninvasively and in real time. All these features lead to a reduction in the number of animals required for experimentation, as well as in the cost of biomedical research and drug development, while providing statistically relevant results [9, 10]. Preclinical molecular imaging has been applied for neurological, cardiovascular, and oncologic diseases; however, it particularly has great potential for use in personalized cancer therapy, enabling the study of biological processes and therapy response in individual patients [11]. The assessment of biological properties of tumors, such as metabolism, proliferation, hypoxia, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and gene and receptor expression, contributes to the realization of precision medicine [12, 13], owing to the possibility of monitoring physio-pathological processes in vivo, detecting therapeutic responses, identifying nonresponders at an early stage, and enabling the switch to novel therapeutic approaches [14, 15].

This review aims to report the latest advances in precision medicine obtained with the application of molecular imaging techniques in mouse models of breast cancer. The techniques, tracers, and models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the molecular preclinical imaging techniques used with regard to personalized medicine. The columns define the techniques, tracers, and cell lines used to model human breast cancer, specific receptor targets, and therapies.

| Imaging | Tracer | Cell line | Receptor | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342 | MDA-MB-361 | HER2 | 17-DMAG | [16, 17] |

| MCF7 | |||||

| MDA-MB-468 | |||||

| MCF7/clone18 | |||||

| BT474 | |||||

| PET | 18F-FBEM-HER2:342 | BT474 | HER2 | Trastuzumab | [18] |

| NIR PET |

700 Annexin-V | BT474-AZ MMTV/HER2 | HER2 | Trastuzumab | [19] |

| 18F-FDG | |||||

| 18F-FLT | |||||

| MRI (DW–DCE) |

BT474 | HER2 | Trastuzumab | [20] | |

| HR6 | |||||

| PET–MRI | 18F-FLT | BT474 | HER2 | Trastuzumab | [21] |

| HR6 | |||||

| NIR PET |

700 Annexin-V | MMTV/HER2+ | HER2 | Trastuzumab Rapamycin |

[22] |

| 18F-FDG | |||||

| NIR | QD-PEG | SKBR-3 | HER2 | [23] | |

| QD-4D5scFv | |||||

| HFUS | Anti-VEGFR2-MBs | 67NR | VEGFR2 | [24] | |

| PET | 18F-FES | SSM2 | ERα–PR | Fulvestrant | [25] |

| 18F-FFNP | SSM3 |

2. Breast Cancer Mouse Models

The most common oncologic animal models, i.e., those utilizing a xenograft, are based on the subcutaneous injection of human-derived cell lines in immunodeficient mice. However, these models are not always representative of the overall heterogeneity detectable in naturally occurring cancers and may thus lack predictive value [26]. Hence, models that more closely mirror the heterogeneity of human tumors are necessary for more efficient drug development, i.e., the use of transgenic or patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDX) models [14, 27–30]. These models summarize the biological characteristics of the original disease, thus having much stronger predictive value for the clinical outcome [26, 31]. In any case, mouse models allow the mechanisms of drug resistance to be studied, enabling patient stratification and assignment of nonresponders to novel, and potentially more effective, therapies [26, 31].

2.1. Breast Cancer Subcategories

Personalized medicine for breast cancer could be considerably advantageous in terms of healthcare and socioeconomic impact because breast cancer is the second most diffuse as well as the second most common oncologic cause of death [15]. In precision medicine for breast cancer, the peculiar molecular characteristics of different cancer subtypes may help the stratification of patients, as well as the development and evolution of novel therapeutic strategies. Molecular subtypes can be distinct, for example, on the basis of their hormone receptor status. Luminal breast cancers are typically hormone receptor-positive, whereas tumors expressing the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) are usually hormone receptor-negative [14, 15]. The third main subtype, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), represents a diverse group of tumors and is characterized by the absence of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors. Specific interventions for this type of tumor are difficult owing to a high level of heterogeneity within this subtype and owing to the absence of well-defined molecular targets [29, 32].

The HER2, also called the avian erythroblastosis oncogene B (ErbB2), is a transmembrane receptor, which is included in the epidermal growth factor receptor family of tyrosine kinases. It predefines pathways that promote various cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, and antiapoptotic functions [18]. The HER2 is associated with high-grade breast tumors, and its overexpression is considered a marker of aggressiveness and malignancy, as well as an index of resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Analysis of HER2 expression is important for monitoring treatment response and efficacy, particularly with regard to trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the HER2, inhibiting the growth of tumor cells and decreasing HER2 expression [23, 33, 34].

Estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and progesterone receptor (PR) are expressed in most human breast cancers and are important therapeutic targets. Hence, there is a need to identify ERα-positive (ERα+)/PR-positive (PR+) tumors, which will likely respond to specific hormonal therapy [25].

Besides these main subcategories, with respect to precision medicine, other receptors expressed in tumor tissues in general, as well as specifically in breast cancer, should be considered. Among such receptors, the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) has been used as a target for precision diagnostic imaging as well for precision therapy. The VEGFR2 is highly expressed during early tumor development, and its expression is linked to the onset of neoangiogenesis [35].

3. Positron Emission Tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear medicine imaging technique, which can be used to investigate metabolic processes in the body. Positron-emitting (ß+) isotopes can be linked to various substances, e.g., 18 fluorine (18F) to 2-deoxy-2-(18F)-fluoro-d-glucose (FDG) for glucose metabolism, and their solutions are injected intravenously in patients as well as in animals prior to image acquisition at specific time points or dynamically over time. The system detects pairs of photons in the gamma-ray spectrum of 511 keV, which are produced by the annihilation reaction between ß+ emitted by the radioisotope and electrons present in the surrounding medium. Different types of radioactive tracers exist, and their selection depends on the pathology/metabolic process being studied. The aforementioned radiotracer, 18F-FDG, which measures glucose metabolism, is the most commonly used radiopharmaceutical in oncology. However, other radiotracers are used to quantify other cellular processes, for example, cell proliferation can be measured with 18F-fluoro-3′-deoxy-3′-L-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), which is a substrate of the thymidine-kinase-1 during the S-phase of mitosis [36], or 18F-fluoro-misonidazole (18F-FMISO), which is a specific radiotracer to study hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment [37]. Moreover, positron-emitting isotopes can be used for biodistribution studies of novel drugs [38].

3.1. Precision Imaging

The possibility of in vivo quantification of HER2 receptors was assessed using preclinical PET imaging with 3.7–4.4 MBq of N-2-(4-18F-fluorobenzamido)ethylmaleimide–18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody molecule. The tracer was administered to female athymic nude mice bearing xenografts from human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-361, MCF7, MDA-MB-468, MCF7/clone18, or BT474. These cell lines showed five different levels of HER2 expression, as demonstrated ex vivo by immunohistochemistry: (1) BT474, very high; (2) MCF7/clone18, high; (3) MDA-MB-361, medium; (4) MCF7, very low, and (5) MDA-MB-468, negative. The results showed that 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody rapidly accumulated in HER2-positive tumors and was just as rapidly eliminated from the blood and normal tissues. Indeed, significant differences in the uptake of the radiolabeled affibody were recorded between tumor and normal tissues and among different breast cancer cell lines (BT474 and MCF7/clone18 showed high uptake, MCF7 and MDA-MB-361 showed a very low uptake, and MDA-MB-468 tumors showed no uptake). These results suggest that the 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody molecule can be used to quantify HER2 expression in vivo [16, 17].

3.2. Therapy Response and Detection of Responders vs. Nonresponders

17-(Dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG) is an inhibitor of heat shock protein (Hsp) 90, which is known to decrease HER2 expression. The PET acquisitions with 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody were performed before and after treatment with four doses of 17-DMAG. The effect of the 17-DMAG treatment on HER2 expression was compared between mice bearing BT474 and MCF7/clone18, and a lower level was found in MCF7/clone18. These results suggest that 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody can be used not only to quantify the HER2 expression in vivo but also to monitor its variations in response to therapeutic interventions [16, 17].

Similarly, the HER2 expression levels were evaluated in breast xenografts mouse models, in response to trastuzumab. For PET scans, animals were injected with 3.7–6.7 MBq of 18F-FBEM-HER2:342-Affibody via the lateral tail vein and were scanned before the treatment, at 48 h and 2 weeks after the beginning of therapy. At each time point, the tracer uptake in the tumor lesion was quantified and the results were normalized to baseline. The analysis indicated a clear decrease in radiotracer uptake as soon as after the first administration of trastuzumab in the treated mice compared to controls, most likely as a result of the reduction in HER2 levels. The reduction in 18F-FBEM-HER2:342-Affibody uptake was thus considered a proof of the antitumor activity of trastuzumab. However, there were differences in the radiotracer uptake at the end of the treatment responses, probably due to a heterogeneous response to the lower dosage. These findings were confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis, which showed a high heterogeneity in receptor expression between individual samples. Moreover, immunohistochemistry showed a stronger reduction in HER2 expression in lesions with higher vessel counts, the latter probably being responsible for better delivery of trastuzumab [18].

The efficacy of trastuzumab was further assessed and predicted through the correlation of molecular imaging biomarkers of apoptosis, glucose metabolism, and cell proliferation and tumor regression, in responsive and nonresponsive tumor-bearing cohorts, in two mouse models of breast cancer overexpressing HER2. In the first model, mammary tumors from mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)/HER2 transgenic female mice were transplanted into immunocompetent syngeneic FVB female mice. In the second model, nude athymic female mice were injected s.c. with human breast carcinoma cell lines. All mice were then treated with trastuzumab. Tumor glucose metabolism was assessed with 18F-FDG PET and cellular proliferation with 18F-FLT PET. Tumor cell apoptosis was assessed with an optical imaging tracer based on near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent 700-Annexin V; it will be discussed in the dedicated section. Animals were imaged weekly before and within 24 h of administration of trastuzumab, up to 3 weeks or until complete tumor regression was observed. The 18F-FLT PET imaging accurately predicted trastuzumab response in BT474 xenografts, but not in MMTV/HER2 tumors, which showed a moderate uptake even in regression. In both preclinical models, the uptake of 18F-FDG was not affected by trastuzumab treatment. Therefore, such imaging biomarkers were suitable for detecting early response and predicting treatment outcome, as well for evaluating new molecular targeted therapies in breast cancer [19].

The sensitivity of 18F-FLT in differentiating trastuzumab-sensitive and -resistant HER2 overexpressing xenografts has been assessed in a mouse xenograft model. Female athymic mice were implanted with trastuzumab-sensitive (BT474) or trastuzumab-resistant (HR6) cell lines. Mice were grouped into four cohorts: trastuzumab-treated BT474 and HR6 and the relative vehicle-treated control groups. The therapy included two treatments administered immediately after imaging at baseline and on day 3; the imaging acquisitions were repeated the day after each treatment. Longitudinal tumor volume was measured from T2-weighted MRI using a 7-T scanner, and mice were then injected i.v. with 293 ± 7.00 μCi of 18F-FLT for PET imaging. The tumor to muscle ratio (T : M) was used to compare 18F-FLT uptake in the tumors before and after treatment. The final results revealed the ability of 18F-FLT PET in distinguishing treated from untreated BT474-bearing mice. In contrast, because no differences were detected between treated and untreated HR6-bearing mice, these xenografts could be used to model clinical “nonresponders.” In this perspective, a significant difference in T : M was observed between trastuzumab-sensitive and -resistant cohorts after two treatments. Nonetheless, differences in tumor volume detected by MRI appeared as soon as 18F-FLT uptake differences [21].

In a similar study, the combined use of trastuzumab and rapamycin, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, was examined in inducing regression of HER2-positive mouse mammary tumors in vivo. The mTOR serine/threonine kinase complex (mTORC1) is a major effector in the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) pathway, which is linked with trastuzumab resistance, making it a possible therapeutic target. Tumors from MMTV/HER2 transgenic female mice were transplanted in immunocompetent syngeneic wild-type FVB females, and mice were imaged for tumor cell death and glucose metabolism. The former was studied using NIR700-Annexin V, and the results are discussed in the dedicated section; the latter was studied using 18F-FDG PET. Treatment groups were constituted by vehicle (PBS), trastuzumab, rapamycin, or trastuzumab-rapamycin combination at the same dosages every other day. The combination treatment induced a decrease in 18F-FDG tumor uptake on day 7, which has been considered being linked to cell death, as confirmed by fluorescence imaging [22].

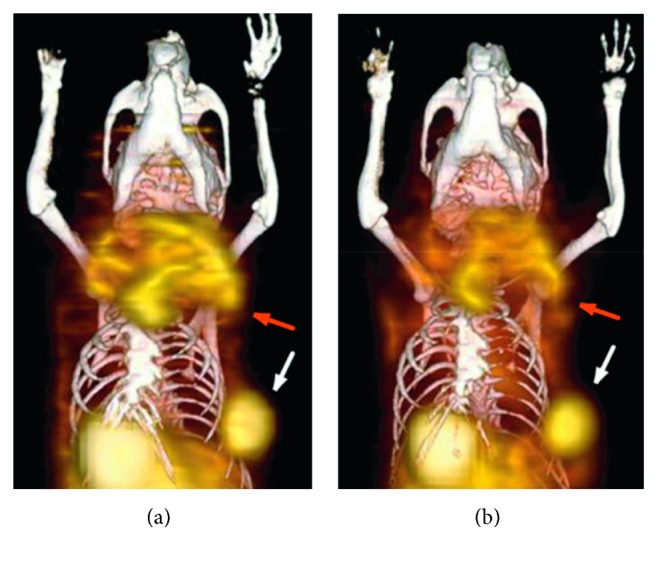

Changes in the expression of tumor steroid hormone receptor after endocrine therapy might be used as predictors of treatment efficacy. In a preclinical model of human luminal breast cancer, intact female wild-type (129S6/SvEv) mice were injected s.c. with either SSM2 (spontaneous signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-deficient (STAT1–/–) mammary) or SSM3 tumor cell lines, derived from primary STAT1–/– spontaneous tumors, into the right thoracic mammary fat pad. Small-animal PET/CT was performed using 18F-fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) for ERα imaging, 18F-fluoro furanyl norprogesterone (18F-FFNP) for PR imaging, and 18F-FDG for glucose uptake. Mice were injected in the tail vein with 11.1 MBq (300 μCi) of 18F-FDG, 11.1 MBq (300 μCi) of 18F-FFNP, or 5.55 MBq (150 μCi) of 18F-FES on separate imaging days. Moreover, mice underwent scans one hour after a radiotracer injection (Figure 1). Image analysis was performed based on T : M. Baseline radiotracer uptake confirmed previous immunohistochemical evaluations, with SSM3 tumors displaying the highest T : M for both 18F-FES and 18F-FFNP, and the SSM2, intermediate values. Hormonal treatment involved the administration of fulvestrant, a pure ER antagonist exhibiting competitive inhibition of receptor binding with estradiol, as well as proteasome-mediated degradation of ER. Control mice were treated with sunflower oil (vehicle). In SSM3, fulvestrant reduced uptake of both 18F-FES and 18F-FFNP, confirming reduced PR proteins levels and ER degradation; reduced 18F-FDG was detected as well. Tumor growth resulted interruption compared to control mice, confirming estrogen signaling inhibition. In SSM2 tumors, 18F-FFNP uptake resulted unexpectedly unchanged, whereas 18F-FES uptake was reduced as for SSM3. Thus, the growth of these tumors as well as their 18F-FDG uptake was unaffected; hence, such a cell line can be used to model “nonresponders.” Based on these results, 18F-FFNP PET can distinguish responders from nonresponders during hormonal therapy targeting ERα, with responders showing marked reduction in the uptake of this radiotracer. Moreover, such changes can be detected as early as three to four days after the initiation of fulvestrant therapy [25].

Figure 1.

Female STAT1–/– mice imaged with small-animal PET/CT using 18F-FES (a) and 18F-FFNP (b). Coronal 3-dimensional fused small-animal PET/CT images show a primary tumor in the left upper thoracic fat pad (red arrow) and a smaller tumor in the left lower thoracic fat pad (white arrow) (adapted from original research published in JNM. [25] © SNMMI).

3.3. Potential Clinical Applications: PET

The major clinical applications of PET-CT include the detection and differentiation of primary breast lesions, lymph node staging, metastasis detection, and monitoring of the response to chemotherapy. Among radiotracers, 18F-FDG is the most commonly used, and it has been shown to be useful for monitoring the effects of chemotherapy and for identifying nonresponders to avoid ineffective chemotherapy. However, its limited sensitivity for small lesions makes 18F-FDG-PET unsuitable for the exclusion of early-stage disease [39–41].

Hence, more sensible and specific tracers for both diagnosis and therapy follow-up are needed. 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody seems to represent a noninvasive option for obtaining real-time information on changes in HER2 expression that facilitates patient selection for anti-HER2 therapy, such as 17-DMAG or trastuzumab treatment, and would result in optimal dose adjustment and treatment schedule for individual patients, as well as in the prediction of tumor response [16–18].

In the clinical field, 18F-FLT is not considered an ideal tracer for tumor detection and staging; however, it has been used as a marker for cellular proliferation. Thus, 18F-FLT- PET imaging could be used as an early biomarker of tumor response to therapy; it might be included among the techniques that can identify nonresponders earlier, and it might be considered an accurate predictor of long-term clinical outcomes [19, 21, 22, 42–45].

Finally, 18F-FFNP PET can distinguish responders from nonresponders during hormonal therapy targeting ERα; hence, it may represent a candidate for early stratification of patients receiving endocrine therapy [25]. Further preclinical as well as clinical trials would be needed to confirm the aforementioned hypotheses on both therapeutic and diagnostic strategies.

4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an advanced clinical and research technique for morphological, structural, and functional imaging. It allows noninvasive evaluation of soft tissues in multiple planes (both two- and three-dimensional imaging) [46, 47]. The physical principle of MRI is the magnetic field, the so-called magnetic moment, of the hydrogen proton, which is present in a very large amount within the body in the form of water. Such a magnetic moment can be manipulated and deflected, longitudinal and transversal magnetization, with external magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses, and the return to the equilibrium state produces a signal recorded and converted to an image by the MR system [48]. The contrast in the final image depends on the intrinsic chemical structure of the tissues imaged (i.e., proton density) and on the recovery time of magnetization of such protons. The latter, obtained with the application of a frequency pulse, induce changes in proton spin. The recovery time to get the initial state is known as T1 and T2 relaxation. T1 relaxation, or spin-lattice relaxation, depends on the interaction of nuclei with external surroundings; it is the time, in milliseconds, required to recover 63% of the longitudinal magnetization. T2 relaxation, or spin-spin relaxation, is produced by random interactions with similar nuclei; it is the time, in milliseconds, required to reduce the transverse magnetization to 37% of its initial value [48]. Based on weighting on T1 and T2 relaxation, many sequences can be developed, aiming to reveal both evident and subtle structural and physiopathological changes.

4.1. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Imaging

Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging is a perfusion MRI application, based on T1-weighted (T1-w) acquisition, for the assessment of microcirculation and, eventually, antiangiogenic treatment responses [49]. The T1-w sequence used is characterized by high temporal resolution, and it is dynamically performed before, during, and after an intravenous injection of gadolinium-based contrast agents. Such agents reduce the T1 of tissues, which is captured by the scanner as an increased signal intensity. Postprocessing allows extracting semiquantitative and quantitative parameters, which reflect the tumor's vascularization status and permeability [50–52]. Semiquantitative parameters are maximal contrast enhancement (Cpeak, % base), time to peak (TTP, 289 s), speed of contrast uptake (wash-in, % base/min), and clearance rate of the contrast material (wash-290 out, % base/min) [53]. These parameters are either automatically obtained with acquisition software by placing a region of interest (ROI) on the lesion or through in-house scripts developed for processing software such as BioMAP (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Massachusetts, USA), or ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, NIH, USA) [53–55].

Quantitative measurements, derived from the analysis of multicompartmental pharmacokinetic models, estimate contrast kinetic parameters, such as Ktrans (volume transfer constant); ve (volume fraction of extracellular, extravascular space, EES); and Kep (exchange rate constant), which is the Ktrans/ve ratio. The most used compartmental pharmacokinetic models are the generalized kinetic model, also called the Tofts model, Brix model, and shutter-speed model. In particular, the first requires the quantification of the contrast agent concentration by arterial input function (AIF), which is subsequently used in the Tofts mathematical model to calculate the aforementioned quantitative parameters. There are different ways of estimating AIF; for instance, direct sampling of AIF is possible with arterial blood sampling, but it is considered invasive for patients and very challenging in small rodents. Another way is AIF estimation based on MR images (image-derived AIF), which is noninvasive, but it is time consuming in postprocessing; it can only be performed by placing ROIs on large vessels, such as the aorta, and higher doses of contrast agents are required [56]. The AIF can also be calculated by evaluating the contrast agent concentration in reference tissues; for instance, by placing an ROI on thigh muscles, whose perfusion rate, extraction fraction, and extracellular volume are known [57]. However, the most common method remains the population-based AIF drawn from scientific literature [56]. The Brix model estimates the kinetic parameters directly from relative signal intensity curves, which allows reducing errors, particularly in murine models, from image-derived AIF. Due to its physicochemical properties, contrast agents fail to enter the cells, but act only in the EES. However, both Tofts and Brix models assume that the water flux through cells is so rapid that the contrast agent acts on all water protons. In contrast, the shutter-speed model rejects this hypothesis [58, 59]. Indeed, it uses a new parameter, τi, that evaluates how long water protons rest inside the cell, thus quantifying the MR effects on longitudinal magnetization (for all mathematical functions, refer to [59]).

4.2. Diffusion Weighted Imaging

Diffusion is the property of molecules to move inside a system, in relation to physicochemical properties of the surroundings. Free water molecules move without a preferential direction (i.e., the Brownian motion). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is an MRI approach to detect water's random movements inside tissues. When pathological insults change the tissues structure and their biological characteristics, DWI sequences can detect such changes and give significant and early diagnostic indications, particularly in oncology but also in vascular pathologies (e.g., stroke) [60]. The “factor b” or b-value depends on the timing and spacing of the gradients used to generate diffusion images. To obtain valid DW acquisitions, multiple b-values are used, and depending on their higher or lower values, different information can be obtained [61–63]. DWI acquisitions can be elaborated with mathematical algorithms to obtain parametric maps, such as apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps; the ADC map allows determining the reduction of water molecule diffusion caused by cell membranes, thus estimating the cellularity of tissues. For example, the ADC map shows lower intensity in tumor tissues, characterized by a higher cellularity, than in normal tissues [51]. Various mathematical models have been developed to highlight the different properties of diffusion of water molecules when they are inside a complex system, such as human tissues. Currently, the most used way of calculating ADC maps is the Gaussian mono-exponential mathematical model, which is based on the hypothesis that water molecules move freely between body tissues and their displacement follows a Gaussian distribution. However, it is known that the mono-exponential model is not appropriate for evaluating ADC in many tissues [64]. Consequently, different models have been used, such as the intravoxel incoherent motion model (IVIM) and non-Gaussian compartmentalized and noncompartmentalized models, to evaluate ADC as well as the features of other tissues. The IVIM model, using low b-values (i.e., 0–50 s/mm2), can include the contribution of microvasculature to the image signal. Compartmentalized models divide voxels in compartments to evaluate the features of the main tumor tissue (i.e., intracellular, interstitial, and intravascular water). In contrast, noncompartmentalized models, such as kurtosis and stretched exponential model, include in the model parameters the possible compartments without assuming a specific number and consider both spatial heterogeneity and temporal heterogeneity (i.e., the temporal and spatial displacement of water molecules in a given tissue) [63].

4.3. Therapy Response and Detection of Responders vs. Nonresponders

Using the experimental design described in the PET chapter, DW and DCE-MRI sequences were tested for their capacity in measuring the antiproliferative and antivascular effects of trastuzumab and for their sensitivity in identifying responsiveness in HER2+ breast cancer xenograft models. Briefly, female athymic mice were implanted with trastuzumab-sensitive (BT474) or trastuzumab-resistant (HR6) cell lines. Mice were grouped into four cohorts: trastuzumab-treated BT474 and HR6 and the relative vehicle-treated controls. The therapy included two treatments administered immediately after imaging at baseline and on day 3; the imaging acquisitions were repeated the day after each treatment. Tumor volume was measured from T2-weighted images; DW images were acquired using a standard pulsed gradient spin-echo sequence, and DCE T1-weighted images were acquired using a spoiled gradient echo sequence with an i.v. bolus of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-DTPA. Differences in tumor volume were not detectable until the last imaging session, when smaller tumor volumes were revealed in BT474-treated compared to the control group, in HR6-treated compared to the control group, and in BT474-treated compared to the HR6-treated group. In summary, changes in the ADC (Figure 2) and Ktrans (Figure 3(a)) allowed the differentiation between responders and nonresponders late in the therapeutic protocol, whereas the ve of DCE was more sensitive in the early detection of responsiveness (Figure 3(b)), revealing it before tumor size changes [20].

Figure 2.

Diffusion-weighted (DW) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) parametric maps of a representative mouse from each cohort. The columns indicate baseline, day 1, and day 4 posttreatment, whereas each row indicates each of the four experimental groups. Regions with noticeably increased ADC values are observed within the center of the treated and control HR6 cohorts (reprinted from [20], copyright with permission from © 2014 Neoplasia Press, Inc., published by Elsevier Inc.).

Figure 3.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parametric maps. In (a) Ktrans and in (b) ve of a representative mouse from each group. The Ktrans parametric maps reveal enhancement along the periphery with increasing trends in the BT474-treated group. The Ktrans parametric maps remain fairly consistent in HR6-treated groups, while the BT474 and HR6 control groups slightly decrease over time. The ve parametric maps reveal variations within all the observed tumors, with increased levels in the treated groups compared to the control groups (reprinted from [20], copyright with permission from © 2014 Neoplasia Press, Inc., published by Elsevier Inc.).

4.4. Potential Clinical Applications: MRI

The MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality for detecting breast cancer in clinical settings. In this field, MRI is indicated for screening because it is able to detect breast cancer when it is still occult clinically, mammographically, and ultrasonographically. In addition, breast MRI is used to monitor the response to neoadjuvant treatments and to evaluate the integrity of the implants [65]. The DCE and DWI are additional MRI techniques with a strong potential for reducing false-positive diagnosis and unnecessary biopsies. Such sequences improve early assessment, monitoring, and prediction of tumor response to therapy and allow the evaluation of residual tumors [66, 67].

The preclinical study discussed in this manuscript highlighted the ability of DCE and DWI to determine the antiproliferative and antivascular effects of trastuzumab in HER2+ breast cancer xenografts. The results revealed that changes in ADC and Ktrans could distinguish responders from nonresponders, albeit late, whereas the ve of DCE showed a timely detection of responsiveness to a therapeutic protocol [20]. Thus, such sequences might be directly applied in clinical trials to confirm the reported results.

5. High-Frequency Ultrasonography (HFUS)

High-frequency ultrasonography (HFUS) is a noninvasive, cost-effective imaging technique, which can provide real-time images with high spatial resolution [24]. It is based, just as traditional ultrasonography, on the piezoelectric effect of some natural elements, such as quartz, that generate ultrasound (US) wave trains. Such ultrasonic waves travel through soft tissue and they are, in part or fully, reflected back. The distance that the US wave has to cover back and forth, as well as the amount of US wave reflected, are detected and processed by dedicated systems to reconstruct a grayscale, two-dimensional image (brightness or B-mode). The physical-chemical structure of soft tissues encountered by the US wave, in particular their acoustic impedance, determine their US features (i.e., echogenicity), thus allowing fine structural evaluation of soft tissues. In contrast, bones, as well as air, do not allow further transmission of US; the former because it absorbs all US, the latter because it reflects them all. Thanks to technological advancements, HFUS now allows studying small laboratory animals with excellent spatial resolution, but by sacrificing the depth of penetration (which is inversely proportional to US waves' frequency). All clinical applications are available in preclinical US systems, such as motion (M-) mode and tissue-Doppler for cardiologic application and spectral-, power-, and color-Doppler for vascular evaluation [68]. Moreover, US probes' motorization allows for three-dimensional acquisitions [69]. In clinical applications, probes' frequencies are in the range of 2 and 15 MHz. In contrast, small imaging studies adopt probes with frequencies of 20 MHz up to 70 MHz, for the analysis of superficial structures, when very high spatial resolution is needed [70]. The HFUS provides morphologic images of organs and lesions, and it allows longitudinal monitoring of treatment response, in terms of factors such as cytoreduction and vascularization changes.

Microbubbles (MBs) contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) improves the visualization and increases the physio-anatomical information on tumor vascularity and angiogenesis. The enhancing effect produced by MBs occurs thanks to their gaseous nuclei, which reflect most of the US wave, resulting in hyperechogenicity, thus causing a very high contrast compared to the tissues' background [71]. In particular, MB-based ultrasonographic contrast agents (UCAs) have been developed to specifically target tumor vasculature via conjugated peptides and antibodies. Among these, the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) has been used as a target for UCAs [35, 72, 73] because it plays an important role as a regulator of angiogenesis in tumor vasculature (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

In vivo contrast-enhanced high-frequency ultrasonography with antivascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) labeled microbubbles in a xenograft mouse model of breast cancer. The green bar on the left is a colorimetric scale for the specific ultrasonographic contrast agent signal intensity (courtesy of Mancini M., Greco A., unpublished).

5.1. Tumor Response

Many therapeutic agents have been developed to inhibit the functions of the VEGFR2 receptor. Thus, the use of anti-VEGFR2 UCAs would allow not only the detection of this receptor in tumors, but also its quantification in longitudinal follow-up as a measure of response to therapy. To investigate a mouse model of murine breast cancer, MBs conjugated to anti-VEGFR2 were injected into the tail vein. The UCA was allowed to circulate for 4 minutes, a time sufficient for the binding of targeted MBs and the washout of the free circulating ones. Mice were then evaluated in vivo with a HFUS system, with the acquisition of two sets of images, before and after the application of a high-power ultrasonic destruction sequence (20 cycles, 10 MHz, mechanical index of 0.59). The difference in video intensity between the pre- and post-destruction images was measured, providing a semiquantitative measure of the retention level of the UCA in the tumor. The retention of anti-VEGFR2 MBs, measured as explained, was significantly higher compared to the nontargeted UCA. These results validated the use of molecular ultrasonography for in vivo detection and quantification of VEGFR2 expression in breast cancer models and for the evaluation and longitudinal monitoring of new antiangiogenic drug efficacy [24].

5.2. Potential Clinical Applications: HFUS

Ultrasonography is already among the first-line imaging modalities in the clinical setting for many organs, such as the mammary gland, ovaries, and pancreas, for the early detection, molecular profiling, angiogenesis level evaluation, and monitoring of tumors [74–76]. From a translational perspective, HFUS devices have been used successfully for clinical applications, e.g., to study the anterior segments of the eye and the skin [77]. Multiple preclinical studies have shown that US molecular imaging is a versatile, safe, and accurate tool for the evaluation of therapies and for theranostic applications. Indeed, US imaging in combination with MBs may allow better assessment of treatment regimens and the differentiation of responders from nonresponders, and it may also be useful for minimizing drug doses in a treatment protocol [75, 76]. The translation of the CEUS imaging approaches into clinical applications may be easily achievable, since ultrasonography and CEUS are already available and often used in the clinical field [78]. There are several clinical applications of this method, including the assessment of inflammation, such as in inflammatory bowel disease, or transient myocardial ischemia and atherosclerosis.

Among the UCAs, BR55 was the first targeted VEGFR2 contrast agent introduced as a clinical grade. The BR55 is a gas core of a mixture of perfluorobutane and nitrogen used to visualize the expression levels of the molecular marker VEGFR2 to evaluate angiogenesis in various tumor types including breast cancer. Following extensive validation in various preclinical animal models, BR55 was successfully used to monitor the effects of antiangiogenic drugs. Further, targeted UCAs should be developed and tested to refine clinical applications of ultrasonography and to support the development of novel chemotherapeutic agents [35, 76].

6. Optical Imaging

Optical Imaging includes various preclinical imaging techniques based on the detection of light, i.e., photons, at different wavelengths produced by bioluminescence, i.e., light-emitting molecules oxidized by luciferases; fluorescence, i.e., fluorophores excited by laser beam; and photoacoustic, i.e., excitation of either endogenous or exogenous molecules by a laser beam [79]. The choice of the technique depends on the processes in study, e.g., bioluminescence is usually adopted as a surrogate for tumor growth [80]. In contrast, fluorescence is used to study biodistribution as well as physiologic and pathologic processes at the cellular and molecular level [81]. Finally, the photoacoustic effect is best used for the evaluation of microcirculation and hemoglobin oxidation status in tissues [82].

In the context of this review, among the other optical imaging techniques, only fluorescence imaging has been considered. For in-depth preclinical bioluminescence and photoacoustic applications, readers might refer to other recently published reviews [83–85]. As mentioned earlier, the use of fluorescence imaging allows visualizing, noninvasively and without the use of ionizing radiations, and biological processes at the molecular level (Figure 5; [32]), including those influencing tumor behavior and response to drugs [23, 32].

Figure 5.

In vivo fluorescence molecular imaging of breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) xenografts. Tracking of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells labeled with a NIR fluorophore, pretreated with a nuclease-resistant aptamer (Gint4.T) or scrambled aptamer (Scr) (reprinted from [32], copyright with permission from CC by NC 4.0).

Fluorescence imaging can be performed either in two dimensions (fluorescence reflectance imaging, FRI) or in three dimensions (fluorescence molecular tomography, FMT). Both the acquisition modes are based on the ability of a particular exogenous substance, known as fluorophores, to emit light of well-known wavelength once excited by a laser beam of proper wavelength. A digital charge-coupled device camera detects such light, and it transmits the signal to a workstation for image processing. The main difference between FRI and FMT is depth of penetration, with the former allowing only for superficial fluorescence detection and the latter allowing for high-sensitivity quantification of the molecules studied [86]. Moreover, to overcome the low penetration depth of fluorescence in the visible wavelength, current devices work in the NIR wavelength, i.e., usually between 600 and 900 nm for the emission spectrum [87].

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor nanoparticles that work as traditional fluorophores, but with far greater photostability and brightness. Moreover, their excitation can lead to emission of different “colors,” i.e., different wavelengths. As for other nanoparticles, QDs can be decorated for targeted imaging, thus enhancing their specificity, or for lengthening their circulation half-life [88, 89].

6.1. Diagnosis and Tumor Response

As described before, the NIR700-Annexin V optical imaging probe has been demonstrated as a molecular biomarker of tumor cell apoptosis in two studies. In both studies, this approach was helpful, in association with PET imaging, for detecting early response and predicting treatment outcome [19, 22].

In particular, mammary tumors from MMTV/HER2 transgenic female mice were transplanted into immunocompetent syngeneic FVB, and nude athymic female mice were injected s.c. with human breast carcinoma cell lines and then treated with trastuzumab. Animals were imaged weekly before and within 24 h of administration of trastuzumab, up to 3 weeks or until complete tumor regression was observed. The results suggested that molecular imaging of apoptosis might accurately predict trastuzumab-induced regression of both MMTV/HER2 transgenic mouse mammary tumors and BT474 xenografts, as witnessed by the higher accumulation of NIR700-Annexin V in the tumor xenografts [19].

In a similar study, tumors from MMTV/HER2 transgenic female mice were transplanted in immunocompetent syngeneic wild-type FVB females, and mice were imaged for tumor cell death, with NIR700-Annexin V. As described above, groups were treated with vehicle (PBS), trastuzumab, rapamycin, or trastuzumab-rapamycin combination every other day. The results showed that single-agent treatments did not alter tumor NIR700-Annexin V uptake compared to vehicle treatment, but their combination significantly increased absolute tumor fluorescence: hence, demonstrating an early induction of tumor cell death [22].

The NIR-QDs have been developed and have become advanced preclinical contrast agents for efficient tumor imaging [23]. Generally, nanoparticles can be transported and accumulated in the tumor through passive and/or active mechanisms. In passive targeting, nanoparticles accumulate in the tumor through the enhanced permeability and retention effect, which is linked to the structural peculiarities of tumor tissue and is widely used by most anticancer drugs. The active targeting takes advantage of peculiar receptors expressed by neoplastic tissues, to which the targeting moieties bind specifically. Fluorescent QDs were evaluated in a HER2/neu-positive breast cancer model using both passive and active targeting. For passive tumor targeting, 705 nontargeted QDs coated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) were used as contrast agents, whereas 705 ITK carboxyl QD were bound to anti-HER2/neu 4D5scFv antibodies (QD-4D5scFv) for active tumor targeting. In vivo whole-body fluorescence imaging was used to analyze the accumulation of the probes (QD-PEG and QD-4D5scFv) at the tumor site. The maximum difference between QD-PEG and QD-4D5scFv signals was registered 3 hours after i.v. injection, with a 1.5-fold increase. Overall, these data have shown that both passive and active deliveries allow successful imaging of tumors, but QD-4D5scFv fluorescent signal was considerably stronger than that of QD-PEG. Therefore, the choice of passive or active targeting strategy depends on the objectives of the study. Passive tumor targeting was the method of choice to anatomically identify the malignant process. However, the advantage of active tumor targeting is in the ability to analyze both the location of the tumor and its molecular profile. The molecular characteristics might then be used in selecting the right antineoplastic agents and, eventually, in correcting the planned therapeutic strategy [23].

6.2. Potential Clinical Applications: Optical Imaging

Optical imaging includes very sensitive, easy to manage, and relatively cost-effective modalities, with short acquisition times that allow the visualization of physio-pathological processes in vivo with high specificity and in real time [90]. The disadvantages derive from the diffusion, the absorption, and the wavelength of light used, which influence the image resolution and the depth of penetration in the tissues, and consequently the ability to obtain quantitative data [91]. Penetration depth is not a crucial aspect in mice due to their small size, and indeed optical imaging techniques are already suitable for preclinical research. However, optical imaging cannot yet be translated into clinical practice, but the molecular markers discovered with such techniques might be translated [91]. In preclinical research, these modalities have been applied to monitor gene expression and to study toxicology, viral infection, tumor growth, and metastases in real time. In particular, the ability to visualize and quantify blood vessel development in metastases, or to evaluate HER2 expression in vivo and monitor therapy response, makes optical imaging a promising tool to study angiogenesis and carcinogenesis and in choosing effective treatments as an alternative to nuclear medicine techniques [92–94]. The potential clinical translation of fluorescence imaging might be directly possible when penetration depth is not an issue, for example, in endoscopic setup, for intraoperative assessment of surgical margins in specific organs and for superficial breast imaging.

The NIR optical imaging is not yet approved for routine clinical use; however, some studies have revealed its ability to distinguish benign from malignant breast lesions in humans, with the use of NIR optical spectroscopy alone and in combination with MRI [95, 96]. The NIR-QDs can be visualized in deep tissues, and this feature may be suitable for the guided administration of chemotherapeutic agents for the evaluation of micrometastasis sites and for performing an adequate tumor resection in surgery [97, 98]. The QDs have been used in many animal models for molecular imaging of cancer with different targets. However, the main drawback in their clinical translatability is the toxicity of their cadmium core. Hence, a paramount step to enable clinical translation is to determine QD toxicity and reduce their doses and the development of a new generation of cadmium-free QDs [99].

7. Improving Molecular Imaging Clinical Translatability

In vivo molecular imaging still has great potential to contribute to biomedical research, particularly in the preclinical setting, but it is also becoming a useful tool for translational research, helping to understand several features at the molecular, cellular, and organic level. Usually, for clinical translation, a key role of in vivo imaging is drug development: understanding drug mechanism of action, possible patient stratification into responders and nonresponders, and to predict the effectiveness of therapy or to recognize early resistance [100]. Various studies with the techniques mentioned in this manuscript have to be performed in clinical trials, before they can be reliably used for patient care, particularly in the oncology field. For example, DCE-MRI enables the evaluation of tumor neo-vascularization, which is useful for early identification of treatment failures, allowing rapid implementation of second-line therapy [101]. In addition, conventional breast DCE-MRI has been demonstrated in clinical studies to enable early identification of tumor response in patients with breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). The accurate assessment of the response to NAC treatment before surgery offers the possibility of avoiding unnecessary, mutilating procedures [102, 103]. Implementing the use of PET in preliminary breast cancer studies may support clinical decision-making through monitoring receptor expression during treatment, aiming at developing personalized treatment strategies and/or predicting prognosis [104]. Interesting results, for example, were collected on sensitivity and specificity of PET in identifying NAC responders in TNBC mouse models [105]. The translation of novel radiotracers for precision imaging would improve the clinical management and outcome of patients affected, in particular TNBC patients, who rely upon a limited number of therapeutic opportunities with poor prognosis [105]. Furthermore, CEUS using targeted VEGFR2 MBs has been evaluated in clinical settings, and is considered as an additional screening modality, other than mammography and conventional ultrasonography, to improve diagnostic accuracy for early detection of breast cancer or even for its precursor lesions. Such an approach, with the other cited imaging technologies, may improve the ability to visualize the molecular characteristics of breast cancer in each patient, with high sensitivity and specificity, improving all the phases of patient management [73].

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Personalized medicine is still in a developing stage. The customization of therapies represents a desirable future, in which diseases are detected earlier and treatments are tailored to the profile of individual patients. Preclinical molecular imaging may be one of the keys for rapid advancement in this field. Its ability to characterize molecular features of different histotypes and to discriminate responders from nonresponders could empower the translational utility of mouse models. From this perspective, the use of PDX in testing therapeutic responses would represent a real-time personalization for individual patients, even if such models may lack recapitulation of the human tumor microenvironment, as well as immune response. Their disadvantages could be related to long bureaucratic times, expensive costs, ethical considerations, and experimental failures, but animal models remain an irreplaceable tool to improve and better comprehend molecular mechanisms and patterns of oncologic diseases.

Abbreviations

- (17-DMAG):

17-(dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- 18F-FBEM-HER2:

342:18F-fluorobenzamidoethylmaleimide

- 18F-FBEM-ZHER2:

342:N-2-4-18F-fluorobenzamidoethylmaleimide

- 18F-FDG:

2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-d-glucose

- 18F-FES:

18F-fluoroestradiol

- 18F-FFNP:

18F-fluoro furanyl norprogesterone

- 18F-FLT:

18F-fluoro-3-deoxythymidine

- 18F-FMISO:

18F-fluoro-misonidazole

- ADC:

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- AIF:

Arterial input function

- CEUS:

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography

- Cpeak:

Maximal contrast enhancement

- DCE:

Dynamic contrast-enhanced

- DW:

Diffusion-weighted

- EES:

Extracellular, extravascular space

- ERα:

Estrogen receptor-α

- ErbB2:

Avian erythroblastosis oncogene B

- FRI:

Fluorescence reflectance imaging

- FMT:

Fluorescence molecular tomography

- HFUS:

High-frequency ultrasound

- HER2:

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- Hsp 90:

Heat shock protein 90

- i.p:

Intraperitoneal

- i.v.:

Intravenous

- IVIM:

Intravoxel incoherent motion model

- Kep:

Exchange rate constant

- Ktrans:

Volume transfer constant

- MBs:

Microbubbles

- MMTV:

Mouse mammary tumor virus

- MRI:

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mTOR:

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- mTORC1:

Serine/threonine kinase complex

- NAC:

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- NIR:

Near-infrared

- PBS:

Phosphate buffered saline

- PDX:

Patient-derived tumor xenograft

- PEG:

Polyethyleneglycol

- PET:

Positron emission tomography

- PI3K:

Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase

- PR:

Progesterone receptor

- s.c.:

Subcutaneously

- QDs:

quantum dots

- ROI:

Region of interest

- SSM2:

Spontaneous signal STAT1–/– mammary

- STAT1–/–:

Spontaneous signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-deficient

- TNBC:

Triple negative breast cancer

- TTP:

Time to peak

- UCAs:

Ultrasonographic contrast agents

- ve:

Volume fraction of EES

- VEGFR2:

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Society of Radiology. Medical imaging in personalised medicine: a white paper of the research committee of the European Society of Radiology (ESR) Insights Into Imaging. 2011;2(6):621–630. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jameson J. L., Longo D. L. Precision medicine—personalized, problematic, and promising. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(23):2229–2234. doi: 10.1056/nejmsb1503104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdes R., Jr., Yin D. Fundamentals of pharmacogenetics in personalized, precision medicine. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2016;36(3):447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z.-G., Zhang L., Zhao W.-J. Definition and application of precision medicine. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2016;19(5):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Jong M., Essers J., Van Weerden W. M. Imaging preclinical tumour models: improving translational power. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(7):481–493. doi: 10.1038/nrc3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massoud T. F., Gambhir S. S. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes & Development. 2003;17(5):545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Incoronato M., Aiello M., Infante T., et al. Radiogenomic analysis of oncological data: a technical survey. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(4):p. 805. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai W., Rao J., Sanjiv S., Gambhir S. S., Chen X. How molecular imaging is speeding up antiangiogenic drug development. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2006;5(11):2624–2633. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-06-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan D., Lanza G. M., Wickline S. A., Caruthers S. D. Nanomedicine: perspective and promises with ligand-directed molecular imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 2009;70(2):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehlerding E. B., Cai W. Harnessing the power of molecular imaging for precision medicine. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57(2):171–172. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.166199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penet M.-F., Krishnamachary B., Chen Z., Jin J., Bhujwalla Z. M. Molecular Imaging of the tumor microenvironment for precision medicine and theranostics. Advances in Cancer Research. 2014;124:235–256. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-411638-2.00007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf G., Abolmaali N. Preclinical molecular imaging using PET and MRI. Molecular Imaging in Oncology. 2013;187:257–310. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10853-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonçalves A., Bertucci F., Guille A., et al. Targeted NGS, array-CGH, and patient-derived tumor xenografts for precision medicine in advanced breast cancer: a single-center prospective study. Oncotarget. 2016;7(48):79428–79441. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning H. C., Buck J. R., Cook R. S. Mouse models of breast cancer: platforms for discovering precision imaging diagnostics and future cancer medicine. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57(1):60S–68S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.157917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer-Marek G., Kiesewetter D. O., Martiniova L., Jagoda E., Lee S. B., Capala J. [18F]FBEM-ZHER2:342-Affibody molecule-a new molecular tracer for in vivo monitoring of HER2 expression by positron emission tomography. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2008;35(5):1008–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0658-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer-Marek G., Kiesewetter D. O., Capala J. Changes in HER2 expression in breast cancer xenografts after therapy can be quantified using PET and 18F-labeled affibody molecules. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50(7):1131–1139. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer-Marek G., Gijsen M., Kiesewetter D. O., et al. Potential of PET to predict the response to trastuzumab treatment in an ErbB2-positive human xenograft tumor model. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(4):629–637. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah C., Miller T. W., Wyatt S. K., et al. Imaging biomarkers predict response to anti-HER2 (ErbB2) therapy in preclinical models of breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(14):4712–4721. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-08-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whisenant J. G., Sorace A. G., McIntyre J. O., et al. Evaluating treatment response using DW-MRI and DCE-MRI in trastuzumab responsive and resistant HER2-overexpressing human breast cancer xenografts. Translational Oncology. 2014;7(6):768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whisenant J. G., McIntyre J. O., Peterson T. E., et al. Utility of [18F]FLT-PET to assess treatment response in trastuzumab-resistant and trastuzumab-sensitive HER2-overexpressing human breast cancer xenografts. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2015;17(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller T. W., Forbes J. T., Shah C., et al. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin is required for optimal antitumor effect of HER2 inhibitors against HER2-overexpressing cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(23):7266–7276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-09-1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balalaeva I. V., Zdobnova T. A., Krutova I. V., Brilkina A. A., Lebedenko E. N., Deyev S. M. Passive and active targeting of quantum dots for whole-body fluorescence imaging of breast cancer xenografts. Journal of Biophotonics. 2012;5(11-12):860–867. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201200080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D. J., Lyshchik A., Huamani J., Hallahan D. E., Fleischer A. C. Relationship between retention of a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)-Targeted ultrasonographic contrast agent and the level of VEGFR2 expression in an in vivo breast cancer model. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2008;27(6):855–866. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler A. M., Chan S. R., Sharp T. L., et al. Small-animal pet of steroid hormone receptors predicts tumor response to endocrine therapy using a preclinical model of breast cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(7):1119–1126. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.103465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidalgo M., Amant F., Biankin A. V., et al. Patient-derived xenograft models: an emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4(9):998–1013. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-14-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J. I., Decker S., Zaharevitz D., et al. Relationships between drug activity in NCI preclinical in vitro and in vivo models and early clinical trials. British Journal of Cancer. 2001;84(10):1424–1431. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel V. C., Marchionni L., Hierman J. S., et al. A primary xenograft model of small-cell lung cancer reveals irreversible changes in gene expression imposed by culture in vitro. Cancer Research. 2009;69(8):3364–3373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann B. D., Bauer J. A., Chen X., et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(7):2750–2767. doi: 10.1172/jci45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeRose Y. S., Gligorich K. M., Wang G., et al. Patient-derived models of human breast cancer: protocols for in vitro and in vivo applications in tumor biology and translational medicine. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. 2013;14 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1423s60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hidalgo M., Bruckheimer E., Rajeshkumar N. V., et al. A pilot clinical study of treatment guided by personalized tumorgrafts in patients with advanced cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2011;10(8):1311–1316. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-11-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camorani S., Hill B. S., Fontanella R., et al. Inhibition of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells homing towards triple-negative breast cancer microenvironment using an anti-PDGFRβ aptamer. Theranostics. 2017;7(14):3595–3607. doi: 10.7150/thno.18974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theriault R. L., Carlson R. W., Allred C., et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2013. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013;11(7):753–761. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gradishar W. J., Anderson B. O., Balassanian R., et al. NCCN guidelines insights: breast cancer, version 1.2017. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2017;15(4):433–451. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bzyl J., Palmowski M., Rix A., et al. The high angiogenic activity in very early breast cancer enables reliable imaging with VEGFR2-targeted microbubbles (BR55) European Radiology. 2013;23(2):468–475. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2594-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miele E., Spinelli G., Tomao F., et al. Positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers in oncology—utility of 18f-fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG)-PET in the management of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;27(1):p. 52. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Z., Li X.-F., Zou H., Sun X., Shen B. 18F-fluoromisonidazole in tumor hypoxia imaging. Oncotarget. 2017;8(55):94969–94979. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brady F., Luthra S., Brown G., et al. Radiolabelled tracers and anticancer drugs for assessment of therapeutic efficacy using PET. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2001;7(18):1863–1892. doi: 10.2174/1381612013396907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoh C. K., Schiepers C. 18-FDG imaging in breast cancer. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 1999;29(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(99)80029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avril N., Rosé C. A., Schelling M., et al. Breast imaging with positron emission tomography and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose: use and limitations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(20):3495–3502. doi: 10.1200/jco.2000.18.20.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García García-Esquinas M. A., Arrazola García J., García-Sáenz J. A., et al. Predictive value of PET-CT for pathological response in stages II and III breast cancer patients following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel. Revista Española de Medicina Nuclear e Imagen Molecular (English Edition) 2014;33(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smyczek-Gargya B., Fersis N., Dittmann H., et al. PET with [18F]fluorothymidine for imaging of primary breast cancer: a pilot study. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2004;31(5):720–724. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Been L. B., Elsinga P. H., de Vries J., et al. Positron emission tomography in patients with breast cancer using 18F-3′-deoxy-3′-fluoro-l-thymidine (18F-FLT)-a pilot study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 2006;32(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pio B. S., Park C. K., Pietras R., et al. Usefulness of 3′-[F-18]Fluoro-3′-deoxythymidine with positron emission tomography in predicting breast cancer response to therapy. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2006;8(1):36–42. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Contractor K. B., Kenny L. M., Stebbing J., et al. [18F]-3′Deoxy-3′-Fluorothymidine positron emission tomography and breast cancer response to docetaxel. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(24):7664–7672. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bammer R., Skare S., Newbould R., et al. Foundations of advanced magnetic resonance imaging. Neurotherapeutics. 2005;2(2):167–196. doi: 10.1007/bf03206665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buxton R. B. The physics of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Reports on Progress in Physics. 2013;76(9) doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/76/9/096601.096601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seeger L. L., Leanne L. Physical principles of magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1989;244:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Y., Cho G., Suh J.-Y., et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for monitoring antiangiogenic treatment: determination of accurate and reliable perfusion parameters in a longitudinal study of a mouse xenograft model. Korean Journal of Radiology. 2013;14(4):589–596. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heyerdahl H., Røe K., Brevik E. M., Dahle J. Modifications in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging parameters after α-particle-emitting 227Th-trastuzumab therapy of HER2-expressing ovarian cancer xenografts. International Journal of Radiation Oncology ∗ Biology ∗ Physics. 2013;87(1):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnes S. L., Sorace A. G., Whisenant J. G., McIntyre J. O., Kang H., Yankeelov T. E. DCE- and DW-MRI as early imaging biomarkers of treatment response in a preclinical model of triple negative breast cancer. NMR in Biomedicine. 2017;30(11) doi: 10.1002/nbm.3799.e3799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taxt T., Reed R. K., Pavlin T., Rygh C. B., Andersen E., Jiřík R. Semi-parametric arterial input functions for quantitative dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in mice. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2018;46:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S. H., Choi M. S., Kim M. J., Kim Y. H., Cho S. H. Role of semi-quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging in characterization and grading of prostate cancer. European Journal of Radiology. 2017;94:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isebaert S., De Keyzer F., Haustermans K., et al. Evaluation of semi-quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI parameters for prostate cancer in correlation to whole-mount histopathology. European Journal of Radiology. 2012;81(3):e217–e222. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khalifa F., Soliman A., El-Baz A., et al. Models and methods for analyzing DCE-MRI: a review. Medical Physics. 2014;41(12):p. 124301. doi: 10.1118/1.4898202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woolf D. K., Taylor N. J., Makris A., et al. Arterial input functions in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: which model performs best when assessing breast cancer response? The British Journal of Radiology. 2016;89(1063) doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150961.20150961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kovar D. A., Lewis M., Karczmar G. S. A new method for imaging perfusion and contrast extraction fraction: input functions derived from reference tissues. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1998;8(5):1126–1134. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Inglese M., Cavaliere C., Monti S., et al. A multi-parametric PET/MRI study of breast cancer: evaluation of DCE-MRI pharmacokinetic models and correlation with diffusion and functional parameters. NMR in Biomedicine. 2019;32(1) doi: 10.1002/nbm.4026.e4026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Litjens G. J. S., Helesen M., Buurman J., ter Haar Romeny B. M. Pharmacokinetic models in clinical practice: what model to use for DCE-MRI of the breast?. Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro; April 2010; Rotterdam, Netherlands. IEEE; pp. 185–188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chilla G. S., Tan C. H., Xu C., Poh C. L. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging and its recent trend—a survey. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 2015;5(3):407–422. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.03.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burdette J. H., Durden D. D., Elster A. D., Yen Y.-F. High b-value diffusion-weighted MRI of normal brain. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 2001;25(4):515–519. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stejskal E. O., Tanner J. E. Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1965;42(1):288–292. doi: 10.1063/1.1695690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang L., Zhou X. J. Diffusion MRI of cancer: from low to high b-values. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2019;49(1):23–40. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng Q., Shi F., Zhang J., Ling C., Dong F., Jiang B. A modified tri-exponential model for multi-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging: a method to detect the strictly diffusion-limited compartment in brain. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2018;12:p. 102. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenwood H. I., Freimanis R. I., Carpentier B. M., Joe B. N. Clinical breast magnetic resonance imaging: technique, indications, and future applications. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 2018;39(1):45–59. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petralia G., Bonello L., Priolo F., Summers P., Bellomi M. Breast MR with special focus on DW-MRI and DCE-MRI. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11(1):76–90. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2011.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Partridge S. C., McDonald E. S. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the breast protocol optimization, interpretation, and clinical applications. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America. 2013;21(3):601–624. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cootney R. W. Ultrasound imaging: principles and applications in rodent research. ILAR Journal. 2001;42(3):233–247. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rix A., Lederle W., Siepmann M., et al. Evaluation of high frequency ultrasound methods and contrast agents for characterising tumor response to anti-angiogenic treatment. European Journal of Radiology. 2012;81(10):2710–2716. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shung K. K. High frequency ultrasonic imaging. Journal of Medical Ultrasound. 2009;17(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0929-6441(09)60012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deshpande N., Needles A., Willmann J. K. Molecular ultrasound imaging: current status and future directions. Clinical Radiology. 2010;65(7):567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deshpande N., Ren Y., Foygel K., Rosenberg J., Willmann J. K. Tumor angiogenic marker expression levels during tumor growth: longitudinal assessment with molecularly targeted microbubbles and US imaging. Radiology. 2011;258(3):804–811. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bachawal S. V., Jensen K. C., Lutz A. M., et al. Earlier detection of breast cancer with ultrasound molecular imaging in a transgenic mouse model. Cancer Research. 2013;73(6):1689–1698. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Korpanty G., Carbon J. G., Grayburn P. A., Fleming J. B., Brekken R. A. Monitoring response to anticancer therapy by targeting microbubbles to tumor vasculature. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(1):323–330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-06-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kiessling F., Fokong S., Koczera P., Lederle W., Lammers T. Ultrasound microbubbles for molecular diagnosis, therapy, and theranostics. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(3):345–348. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abou-Elkacem L., Bachawal S. V., Willmann J. K. Ultrasound molecular imaging: moving toward clinical translation. European Journal of Radiology. 2015;84(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shung K. K., Cannata J., Zhou Q., Lee J. High frequency ultrasound: a new frontier for ultrasound. Proceedings of the 2009 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; September 2009; Minneapolis, MN, USA. IEEE; pp. 1953–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Willmann J. K., Paulmurugan R., Chen K., et al. US imaging of tumor angiogenesis with microbubbles targeted to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 in mice. Radiology. 2008;246(2):508–518. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arridge S. R., Schweiger M. Image reconstruction in optical tomography. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 1997;352(1354):717–726. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greco A., Auletta L., Orlandella F., et al. Preclinical imaging for the study of mouse models of thyroid cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(12):p. 2731. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vasquez K. O., Casavant C., Peterson J. D. Quantitative whole body biodistribution of fluorescent-labeled agents by non-invasive tomographic imaging. PLoS One. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020594.e20594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia J., Yao J., Wang L. H. V. Photoacoustic tomography: principles and advances. Progress in Electromagnetics Research. 2014;147:1–22. doi: 10.2528/pier14032303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu T., Close D., Handagama W., Marr E., Sayler G., Ripp S. The expanding toolbox of in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Frontiers in Oncology. 2016;6:p. 150. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Manni I., de Latouliere L., Gurtner A., Piaggio G. Transgenic animal models to visualize cancer-related cellular processes by bioluminescence imaging. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2019;10:p. 235. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gargiulo S., Albanese S., Mancini M. State-of-the-Art preclinical photoacoustic imaging in oncology: recent advances in cancer theranostics. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging. 2019;2019:24. doi: 10.1155/2019/5080267.5080267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]