Abstract

Objective:

To investigate optimal cutoff scores and the effects of normative adjustments on the performance of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) as a screening instrument for Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD-dementia).

Methods:

499 adults 48 to 91 years-old enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and were administered the MoCA during baseline. Participants were classified as either cognitively normal (CN), MCI, or AD-dementia by clinical assessment. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed using raw MoCA scores, education-adjusted MoCA scores, and a regression-based adjustment derived from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center data (NACC). Test performance characteristics were calculated for various cutoffs after each normative correction method.

Results:

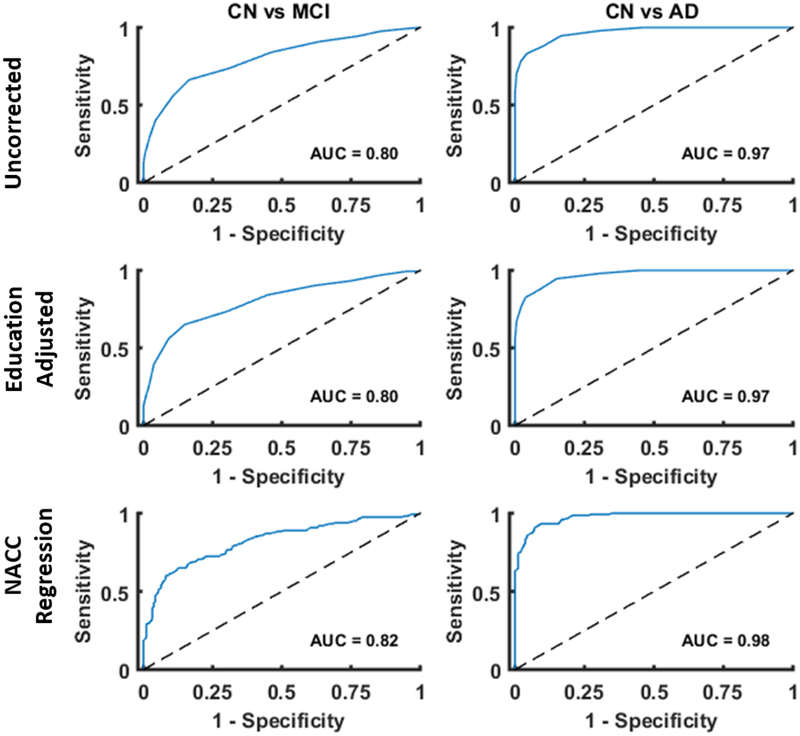

Areas under the curve (AUC) were similar for raw, education-adjusted, and NACC-adjusted MoCA scores, and demonstrated minimal improvement when adjustments of increasing complexity were applied. Youden’s index indicated that the optimal cutoff score may be lower than the established cutoff of 26.

Conclusions:

This study adds to the understanding of how normative adjustments affect the sensitivity and specificity of the MoCA. Suggested corrections based on education alone do not yield improved test characteristics, but small improvements are attained when a regression-based correction that accounts for age, sex, and education is applied. Furthermore, optimal cutoffs for distinguishing CN from MCI or CN from AD-dementia were lower than previously reported. Optimal cutoffs to detect MCI and AD-dementia may vary in different populations, and further study is needed to determine appropriate use of the MoCA as a screening tool.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, MoCA, mild cognitive impairment, ADNI

Objective

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (1) is increasingly used by clinicians and researchers as a brief screening measure to assess cognitive impairment. MoCA scores range from 0 to 30 with lower scores indicating decreased cognitive ability. The MoCA has been described as more sensitive and specific than other screening tools, such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (2) and uses an established cutoff score for Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) of <26 with a 1-point adjustment for years of education (≤12). However, the clinical utility of this cutoff score and of normative adjustments to this threshold is based on limited research.

To date, the MoCA has been used to quantify cognitive changes across a broad spectrum of neurocognitive disorders including studies of MCI and Alzheimer’s disease (2–5), cerebrovascular disease (5–7), Lewy Body disease (8) and Parkinson’s disease (9–13). The MoCA has also been used to predict conversion from MCI to dementia. Julayanont et al. assessed the discriminative ability of the MoCA in predicting conversion from MCI to dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD-dementia) and found that MCI participants with lower MoCA scores at the time of diagnosis were more likely to convert to AD-dementia over an 18-month period (4). Further, the use of the MoCA in an MCI population demonstrated sensitivity to progression with decreased scores over a 3.5-year period, as compared to healthy controls whose scores remained stable (14).

However, recent studies have indicated that the recommended cutoff score of 26 or greater may have relatively low specificity and lead to a large false positive rate of cognitive impairment – regardless of population setting, age, or education (5, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16). A Cochrane review (3) examined the diagnostic accuracy of the MoCA for detecting dementia using the cutoff of 26. The MoCA was reported to have good sensitivity for detecting dementia but with low specificity (a cutoff of 26 would have incorrectly diagnosed ~40% of pooled study participants with dementia). The authors concluded that this cutoff is likely too high and that further research is needed to determine the optimal cutoffs for detecting dementia and its subtypes. Further, the risk for excessive false positives has been echoed in several recent studies including in community samples of African Americans where concerns have been raised about the predictive value and utility of the MoCA in diverse populations (17, 18).

The current study aimed to investigate the effects of normative adjustments on performance of the MoCA and to explore optimal cutoffs when using the MoCA as a screening instrument for MCI and AD-dementia.

Methods

Data used in the preparation of this manuscript were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu) on 9/28/2014. ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For more information, see www.adni-info.org.

At the time of analysis, the ADNI-2 data set contained 499 adults, 48 to 91 years-old, with baseline MoCA data: 188 cognitively normal (CN; excluding subjective memory complaints), 163 MCI (excluding early MCI), and 148 AD-dementia. This phase of the ADNI study was utilized since the MoCA was not administered in previous enrollment periods. The MoCA was administered to all participants as part of a larger cognitive battery during baseline study procedures. Detailed information describing diagnostic criteria can be found at www.adni-info.org. Briefly, CN subjects had no memory complaints, normal memory performance, and absence of impairment in cognition or daily functioning. MCI subjects had a subjective memory concern, abnormal memory performance, and preserved functional performance such that a diagnosis of AD-dementia cannot be made (19). AD-dementia subjects had a subjective memory concern, abnormal memory performance, and functional impairment that met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD-dementia (20). The ADNI database also included early MCI (EMCI) subjects. EMCI subjects had subjective memory concerns, mildly abnormal memory performance, and no functional impairment such that a diagnosis of AD-dementia could not be made. Given that EMCI subjects neither met criteria for MCI or CN and that these subjects do not clearly fit into a diagnostic group, they were excluded from analyses.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating study sites.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used to assess sample characteristics (Table 1). Demographic characteristics were compared across diagnostic groups using Pearson chi-squared or one-way ANOVAs with post-hoc t-tests. The MoCA’s diagnostic accuracy for MCI and AD-dementia subjects was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses. A nonparametric distribution was assumed. ROC analyses were conducted to produce ROC curves for baseline uncorrected MoCA scores. Follow-up ROC analyses were performed using 1) the recommended education adjustment proposed by Nasreddine et al. (1) that consists of adding 1 point to the MoCA total score for individuals with ≤12 years of education and 2) the adjustment derived from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) data, (21) which utilizes a regression equation comprised of MoCA score, age, sex, and education. NACC was developed in 1999 by the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health to assist in the collaborative research of Alzheimer’s disease by maintaining a large database of both clinical and neuropathological data. More detailed information regarding NACC can be found at www.alz.washington.edu.

Table 1:

Participant Demographics

| CN | MCI | AD | df | F or χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 188 | 163 | 148 | – | – | – |

| Age (M±SD) | 73.37 ± 6.26 | 71.99 ± 7.73 | 74.48 ± 8.09 | 2 | 4.51 | 0.011 |

| Sex (% male) | 47.87% | 52.76% | 58.11% | 2 | 3.49 | 0.175 |

| Race (% caucasian) | 88.30% | 93.87% | 91.22% | 10 | 9.74 | 0.464 |

| Education (M±SD) | 16.53 ± 2.56 | 16.50 ± 2.59 | 15.81 ± 2.68 | 2 | 3.82 | 0.023 |

| APOE Genotype (%) | – | – | – | 4 | 59.22 | <0.005 |

| ε4 − | 71.35% | 43.21% | 32.64% | – | – | |

| ε4 + | 25.41% | 40.74% | 47.22% | – | – | |

| ε4/ε4 + | 3.24% | 16.05% | 20.14% | – | – | |

| CDRsb (M±SD) | 0.04 ± .14 | 1.75 ± 1.00 | 4.54 ± 1.68 | 2 | 720.17 | <0.005 |

| MMSE (M±SD) | 29.02 ± 1.26 | 27.58 ± 1.82 | 23.07 ± 2.09 | 2 | 517.16 | <0.005 |

| (min-max) | (24–30) | (24–30) | (19–26) | |||

| MoCA (M±SD) | 25.66 ± 2.37 | 22.20 ± 3.28 | 16.93 ± 4.53 | 2 | 268.51 | <0.005 |

| (min-max) | (19–30) | (14–30) | (4–25) |

CDRsb= Clinical Dementia Rating Scale - Sum of Boxes Score, MMSE= Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment, ANOVA for continuous outcomes presented as mean±standard deviation, chi-square test for categorical outcomes, df= degrees of freedom

The AUC measure represents the mean sensitivity value for all possible values of specificity, with larger AUC indicating better diagnostic accuracy. The optimal cutoff points were explored using the Youden’s index (J=sensitivity+specificity-1). Increasing Youden’s index indicates higher combined sensitivity and specificity (22).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

Participant Characteristics

188 CN, 163 MCI, and 148 AD-dementia participants were administered the MoCA at the baseline visit. Diagnostic groups differed significantly for age, years of education (YOE), and APOE ε4 allele number (Table 1). AD-dementia participants were slightly older on average than CN and MCI participants (Table 1). AD-dementia participants were less educated (M=15.8 YOE, SD=2.68) when compared to CN (M=16.5 YOE, SD=2.56) and MCI (M=16.5 YOE, SD=2.59) participants (Table 1). Less than one-fifth of each participant group had 12 or fewer years of education (10.6% of CN, 13.5% of MCI, and 16.9% of AD-dementia). Across the groups, AD-dementia and MCI participants were more likely to have APOE ε4 alleles (Table 1).

MoCA Performance Characteristics - Raw Scores (without education adjustment)

Distinguishing CN and MCI using Raw MoCA Scores.

The raw MoCA total score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing MCI from CN participants (AUC = 0.80, z=15.66, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.50 indicated that a raw MoCA score of 24 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 2).

Table 2:

MoCA Test Characteristics when Distinguishing CN from MCI at Various Cutoff Scores

| No Correction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| 20 | 18% | 100% | 0.18 | 60.97% |

| 21 | 29% | 98% | 0.27 | 64.67% |

| 22 | 40% | 96% | 0.36 | 66.38% |

| 23 | 56% | 89% | 0.45 | 70.66% |

| 24 | 66% | 84% | 0.5 | 67.81% |

| 25 | 74% | 69% | 0.43 | 62.96% |

| 26 | 84% | 54% | 0.38 | 58.69% |

| Education Correction | ||||

| Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| 20 | 17% | 100% | 0.16 | 60.11% |

| 21 | 26% | 98% | 0.24 | 63.82% |

| 22 | 39% | 96% | 0.36 | 66.95% |

| 23 | 56% | 91% | 0.47 | 71.51% |

| 24 | 65% | 85% | 0.5 | 67.52% |

| 25 | 74% | 70% | 0.43 | 63.82% |

| 26 | 84% | 55% | 0.39 | 59.54% |

| NACC Regression | ||||

| z-Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| −1.5 | 55% | 93% | 0.48 | 75.21% |

| −1.25 | 65% | 87% | 0.52 | 76.92% |

| −1 | 71% | 80% | 0.51 | 75.78% |

| −0.75 | 77% | 69% | 0.45 | 72.36% |

| −0.5 | 84% | 61% | 0.45 | 71.23% |

| −0.25 | 88% | 51% | 0.40 | 68.38% |

| 0 | 90% | 40% | 0.30 | 63.53% |

Distinguishing CN and AD-dementia using Raw MoCA Scores.

The raw MoCA score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing AD-dementia from CN participants (AUC = 0.97, z=60.50, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.79 indicated that a raw MoCA score of 22 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 3).

Table 3:

MoCA Test Characteristics when Distinguishing CN from AD at Various Cutoff Scores

| No Correction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| 20 | 70% | 100% | 0.7 | 85.71% |

| 21 | 78% | 98% | 0.76 | 88.10% |

| 22 | 83% | 96% | 0.79 | 86.61% |

| 23 | 89% | 89% | 0.78 | 85.71% |

| 24 | 95% | 84% | 0.78 | 80.36% |

| 25 | 98% | 69% | 0.67 | 73.21% |

| 26 | 100% | 54% | 0.54 | 64.58% |

| Education Correction | ||||

| Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| 20 | 67% | 100% | 0.66 | 84.23% |

| 21 | 76% | 98% | 0.74 | 87.50% |

| 22 | 82% | 96% | 0.79 | 87.20% |

| 23 | 88% | 91% | 0.79 | 86.31% |

| 24 | 95% | 85% | 0.8 | 80.65% |

| 25 | 98% | 70% | 0.68 | 74.11% |

| 26 | 100% | 55% | 0.55 | 65.48% |

| NACC Regression | ||||

| z-Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Accuracy |

| −2 | 80% | 97% | 0.77 | 89.58% |

| −1.75 | 86% | 96% | 0.82 | 91.37% |

| −1.5 | 89% | 93% | 0.82 | 91.07% |

| −1.25 | 93% | 87% | 0.8 | 89.88% |

| −1 | 98% | 80% | 0.78 | 88.10% |

| −0.75 | 99% | 69% | 0.68 | 82.14% |

| −0.5 | 100% | 61% | 0.61 | 77.68% |

| −0.25 | 100% | 51% | 0.51 | 72.62% |

| 0 | 100% | 40% | 0.4 | 66.37% |

MoCA Performance Characteristics – Education Only Correction

Distinguishing CN and MCI using education-adjusted MoCA Scores.

The education-adjusted MoCA score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing MCI from CN participants (AUC = 0.80, z=15.72, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.50 indicated that an education adjusted MoCA score of 24 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 2).

Distinguishing CN and AD-dementia using education-adjusted MoCA Scores.

The education-adjusted MoCA score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing AD-dementia from CN participants (AUC = 0.97, z=69.22, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.80 indicated that an education adjusted MoCA score of 22 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 3).

MoCA Performance Characteristics - NACC (Age, Sex, and Education) Regression Correction

Distinguishing CN and MCI using NACC regression-corrected MoCA Scores.

The NACC regression corrected MoCA score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing MCI from CN participants (AUC = 0.82, z= 17.06, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.52 indicated that an adjusted MoCA z-score of −1.25 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 2).

Distinguishing CN and AD-dementia using NACC regression-corrected MoCA Scores.

The NACC regression corrected MoCA score performed significantly better than chance when distinguishing AD-dementia from CN participants (AUC = 0.98, z=81.28, p < 0.05). A Youden’s index of 0.82 indicated that an adjusted MoCA z-score of −1.50 was optimal for maximizing test performance (see Table 3).

Conclusions

The proposed MoCA cutoff score of <26 was initially validated to differentiate impaired cognition (MCI or dementia) from normal cognition(1). The suggested correction for educational achievement consisted of adding an extra point to the total score for those individuals with less than or equal to 12 years of education. The MoCA is thought to have superior sensitivity and specificity to distinguish normal cognition from cognitive impairment when compared to other brief mental status exams. This study examined the optimal MoCA cutoff score for identifying cognitive impairment when three different normative adjustments for patient demographics were applied. Consistent with previous research, our analyses suggest that the optimal threshold for classifying cognitive impairment on the MoCA may be lower than originally described (16, 23–26). Specifically, the results indicated that a cutoff of 24 was consistently best at distinguishing normal from abnormal cognition. Our finding is consistent with the results from another study where a threshold score of 24 demonstrated superior predictive value in a population with a high prior probability of cognitive impairment (24).

It is important to emphasize that even the uncorrected MoCA score performed well as a screening instrument for MCI and AD-dementia. No apparent improvements in test characteristics were gained when applying the one-point education correction as has been suggested (1). As mentioned previously, 10.6% of the CN group, 13.5% of the MCI group and 16.9% of the AD-dementia group received the one-point correction. After applying the education correction, the AUCs for distinguishing MCI and AD-dementia remained at 0.80 and 0.97 respectfully. For both uncorrected and education corrected scores, a Youden’s index score of 0.50 suggests a MoCA score of 24 maximizes test performance for distinguishing MCI. Furthermore, a Youden’s index score of 0.80 suggests an education-corrected MoCA score of 22 maximizes test performance in distinguishing AD-dementia.

The NACC regression correction yielded the best improvement in test characteristics. The AUCs for distinguishing MCI and AD-dementia were 0.82 and 0.98 respectfully. A Youden’s index score of 0.52 suggests a MoCA adjusted z-score of −1.25 maximizes test performance for distinguishing MCI from CN and a Youden’s index score of 0.82 suggests an adjusted z-score of −1.50 maximizes test performance for distinguishing AD-dementia from CN. At the optimal cutoff of −1.25, the regression-based correction accurately classified 76.92% of subjects with MCI. Additionally, the optimal cutoff of −1.50 accurately classified 91.07% of subjects with AD-dementia. This regression-based correction takes into account age, sex, and education. For example, a 75-year-old male with 18 years of education will fall at a z-score of −1.36 with a score of 23. Whereas, a 75-year-old male with 8 years of education will fall at a z-score of −1.64 with a score of 19. In both of these instances the individuals are scoring in the mildly impaired range. Thus, very low educational attainment may be particularly important to consider when evaluating the effects of normative adjustments on screening cutoffs. We cannot directly compare z-score cutoffs for the NACC regression (e.g. z-score of −1.5 or −1.25) with those that are adjustments to the total score (e.g., 24 vs. 26). However, these findings suggest that incorporating more demographic variables into MoCA corrections provide for better diagnostic classification.

The generalizability of our findings may be limited by characteristics of the ADNI sample. Specifically, the findings may not apply to non-amnestic subtypes of MCI, or to other dementias. Thus, caution is warranted when applying demographic corrections to the MoCA in diverse populations. For example, similar to the original MoCA sample (1) the ADNI sample consists of individuals with higher educational attainment than the general population. Given this, it is somewhat difficult to ascertain the true benefit of 1-point education correction in this sample. Furthermore, education attainment levels may not always accurately indicate premorbid cognitive and functional abilities (1). For that reason, it is important that clinicians use their best clinical judgment when interpreting the results of the MoCA within patient samples that diverge from the study populations. In contrast to prior research, a strength of the present study is that participants were clinically stratified as CN, MCI, or AD-dementia by clinician judgment, global CDR score and neuropsychological testing. This allows for a more specific examination of the utility of the MoCA for identifying the subtle cognitive impairment seen in patients with MCI.

A weakness of this study is low ethnic diversity in the ADNI sample. However, our findings are consistent with findings from studies with diverse samples (17, 18). Rossetti et al. (2011) found that Caucasian participants achieved a significantly higher MoCA score than other racial groups, which did not accurately reflect differences in daily functioning or diagnosis (16, 23–26). Further, research evaluating the MoCA in clinical and non-clinical populations found that internal consistency for the MoCA is better in clinical samples than in community samples (27). Thus, clinicians should be cautious when applying these norms to racially diverse and community populations. Future research in more diverse population samples is clearly needed to explore how different normative corrections might affect test characteristics of the MoCA score. Although, medical comorbidity is less likely to bias our results since the ADNI sample participants are largely free of unstable medical, neurological, or psychiatric comorbidities, community samples are not free of such comorbidities, limiting the external validity of our results.

Overall, this study indicates that optimal cutoffs to detect MCI and AD-dementia may be lower than previously described. Further, our findings suggest an advantage to incorporating additional demographic variables (sex, age, education), compared to a single cutoff score or one-point education correction, when using a regression-based normative approach. The NACC regression-based correction provided the best performance of the MoCA score in distinguishing MCI and AD-dementia from normal cognition. This finding underscores the importance of developing demographically informed norms for commonly used brief cognitive screening measures such as the MoCA.

However, we emphasize that clinicians should use caution when applying any cutoff scores in diverse populations that do not reflect characteristics of those used in norming samples. Of particular concern is the risk that dementia may be over-diagnosed in individuals with low educational attainment. We caution that although screening measures are very useful in determining which individuals may need further diagnostic workups, such measures should never be used alone to diagnose neurodegenerative disorders. Overall, the need to detect individuals who require further evaluation must be balanced with the desire to prevent over-diagnoses and unnecessary costly workups.

In summary, this study adds to the understanding of how normative adjustments affect the test performance of the MoCA. Suggested corrections based on education alone do not yield improved test characteristics, but small improvements are attained when a regression-based correction that accounts for age, sex, and education is applied. Furthermore, optimal cutoffs for distinguishing CN from MCI or CN from AD-dementia were lower than previously reported. Optimal cutoffs to detect MCI and AD-dementia may vary in different populations and further study is needed to determine appropriate use of the MoCA as a screening tool.

Figure 1. ROC plots of baseline MoCA scores with various normative adjustments applied.

Areas under the curve (AUC) were similar for ROC curves constructed with uncorrected MoCA scores, education adjusted scores, and NACC adjusted scores. There was a slight improvement when adjustments of increasing complexity were applied.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the ADNI participants and study sites for their contributions to the study. The authors report no disclosures. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research &Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. This research paper has been presented at the International Neuropsychological Society 46th annual meeting February 14–17, 2018 in Washington, D.C.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P50-AG047270). APM was supported in part by the K23-AG057794.

Appendix 1: Authors

| Name | Location | Role | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erika A. Pugh, M.A. | Yale University | Author | Design and conceptualized study; analyzed the data; interpreted data; drafted the manuscript for intellectual content |

| Emily C. Kemp, B.S. | Yale University | Author | Design and conceptualized study, interpreted the data; analyzed data, revised the manuscript for intellectual content |

| Christopher H. van Dyck, M.D. | Yale University | Author | Interpreted the data; revised the manuscript for intellectual content |

| Adam P. Mecca, M.D., Ph.D. | Yale University | Author | Design and conceptualized study, interpreted the data; analyzed data, revised the manuscript for intellectual content, study supervision |

| Emily S. Sharp, Ph.D. | Yale University | Design and conceptualized study, interpreted the data; revised the manuscript for intellectual content, study supervision |

References

- 1.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. : The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roalf DR, Moberg PJ, Xie SX, et al. : Comparative accuracies of two common screening instruments for classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging. Alzheimers Dement 2013; 9:529–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis DH, Creavin ST, Yip JL, et al. : Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; CD010775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julayanont P, Tangwongchai S, Hemrungrojn S, et al. : The Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic: A Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Illiterate and Low-Educated Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:2550–2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLennan SN, Mathias JL, Brennan LC, et al. : Validity of the montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) as a screening test for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in a cardiovascular population. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2011; 24:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Y, Venketasubramanian N, Chan BP, et al. : Brief screening tests during acute admission in patients with mild stroke are predictive of vascular cognitive impairment 3–6 months after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83:580–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan HH, Xu J, Teoh HL, et al. : Decline in changing Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores is associated with post-stroke cognitive decline determined by a formal neuropsychological evaluation. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0173291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biundo R, Weis L, Bostantjopoulou S, et al. : MMSE and MoCA in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a multicenter 1-year follow-up study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016; 123:431–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou KL, Lenhart A, Koeppe RA, et al. : Abnormal MoCA and normal range MMSE scores in Parkinson disease without dementia: cognitive and neurochemical correlates. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014; 20:1076–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalrymple-Alford JC, MacAskill MR, Nakas CT, et al. : The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010; 75:1717–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoops S, Nazem S, Siderowf AD, et al. : Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009; 73:1738–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lessig S, Nie D, Xu R, et al. : Changes on brief cognitive instruments over time in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2012; 27:1125–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown DS, Bernstein IH, McClintock SM, et al. : Use of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Alzheimer’s Disease-8 as cognitive screening measures in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 31:264–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan K, Rossetti H, Hynan LS, et al. : Changes in Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scores Over Time. Assessment 2017; 24:772–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Belden CM, et al. : Age- and education-adjusted normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in older adults age 70–99. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2015; 22:755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Cullum CM, et al. : Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology 2011; 77:1272–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sink KM, Craft S, Smith SC, et al. : Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Modified Mini Mental State Examination in African Americans. J Aging Res 2015; 2015:872018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Hynan LS, et al. : Montreal Cognitive Assessment Performance among Community-Dwelling African Americans. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2017; 32:238–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. : Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 2010; 74:201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. : Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirk SD, Mitchell MB, Shaughnessy LW, et al. : A web-based normative calculator for the uniform data set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimers Res Ther 2011; 3:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Youden WJ: Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3:32–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson N, Leach L,Murphy KJ: A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 33:379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damian AM, Jacobson SA, Hentz JG, et al. : The Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the mini-mental state examination as screening instruments for cognitive impairment: item analyses and threshold scores. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2011; 31:126–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freitas S, Simoes MR, Maroco J, et al. : Construct Validity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2012; 18:242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gagnon G, Hansen KT, Woolmore-Goodwin S, et al. : Correcting the MoCA for Education: Effect on Sensitivity. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2014; 40:678–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein IH, Lacritz L, Barlow CE, et al. : Psychometric evaluation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in three diverse samples. Clin Neuropsychol 2011; 25:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request.