Abstract

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) measures RNA abundance in a biological sample but does not provide temporal information about the sequenced RNAs. Metabolic labeling can be used to distinguish newly made RNAs from pre-existing RNAs. Mutations induced from chemical recoding of the hydrogen bonding pattern of the metabolic label can reveal which RNAs are new in the context of a sequencing experiment. These nucleotide recoding strategies have been developed for a single uridine analogue, 4-thiouridine (s4U), limiting the scope of these experiments. Here we report the first use of nucleoside recoding with a guanosine analogue, 6-thioguanosine (s6G). Using TimeLapse sequencing (TimeLapse-seq), s6G can be recoded under RNA-friendly oxidative nucleophilic-aromatic substitution conditions to produce adenine analogues (substituted 2-aminoadenosines). We demonstrate the first use of s6G recoding experiments to reveal transcriptome-wide RNA population dynamics.

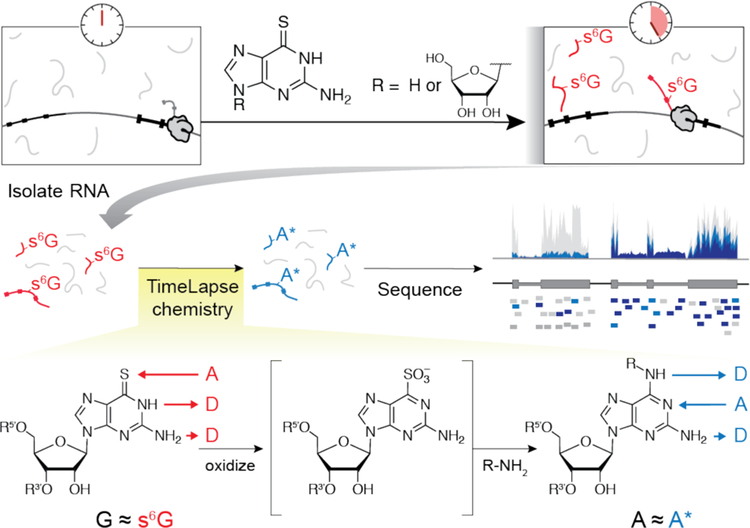

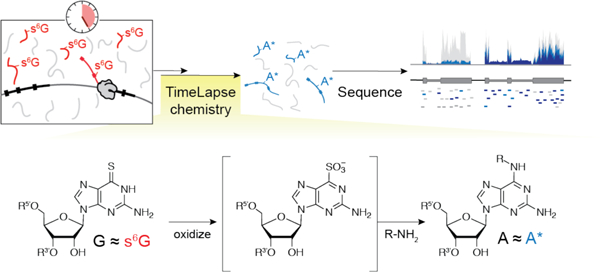

Graphical Abstract

The transcriptome is in constant flux between RNA transcription, processing, and decay, but standard RNA-seq experiments only provide a static snapshot of the cellular RNA levels. Metabolic labeling offers a chemical strategy to distinguish RNAs made over different time periods, but traditionally requires biochemical isolation of the metabolically labeled RNA.1 We and others have developed nucleotide conversion chemistry to study RNA population dynamics transcriptome-wide in an enrichment-free RNA-seq experiment.2–4 In these experiments, living cells are treated with s4U, which is incorporated into newly transcribed RNAs. Total RNA is isolated and either alkylated to produce uridine analogues with a single recoded hydrogen bond (SLAM-seq3) or reacted under oxidative-nucleophilic-aromatic substitution conditions to fully recode s4U into cytosine2 or cytosine analogues (TimeLapse-seq4). After these treatments, newly transcribed RNA can be distinguished from pre-existing RNA by apparent thymidine to cytosine (T-to-C) mutations in sequencing reads, thereby adding a temporal dimension to RNA-seq experiments.

Methods that use nucleotide recoding to study RNA population dynamics are currently limited to a single pyrimidine metabolic label, s4U, making them suboptimal or inappropriate for several applications such as studying the turnover of uridine-tailed RNAs5, pseudouridylated RNAs6, and uridine-poor RNAs. As TimeLapse with s4U is similar to convertible nucleoside chemistry developed to post-synthetically modify oligonucleotides7,8 we were inspired by similar convertible nucleoside approaches that affectively allowed the recoding of purines9. Therefore, we sought to expand the scope of recoding chemistry to a purine nucleotide.

Early studies of metabolic labels suggest several nucleotides can be incorporated into the transcriptome. 10,11 While the most widely used metabolic labels to study RNA population dynamics are uridine analogues, s6G has frequently been employed in photocrosslinking experiments (PAR-CLIP12) and RNA structural studies13. We reasoned that RNA-friendly oxidative-nucleophilic-aromatic substitution (TimeLapse chemistry) that we previously developed for s4U could be extended to recode s6G to 2-aminoadenosine analogues, thereby expanding the toolkit of recodable RNA metabolic labels. Here we report the development of this chemical approach and demonstrate the first use of a guanosine-based metabolic label to measure RNA population dynamics (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Overview of s6G-based TimeLapse-seq to reveal RNA population dynamics.

We hypothesized that the oxidative nucleophilic-aromatic-substitution conditions that we developed for s4U TimeLapse (NaIO4 and 2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine, TFEA)4 could also convert thiolated guanine into N6-substituted analogues of adenine. These conditions were previously optimized to minizmize oxidation of guanine and preserve compatibility with RNA-seq. These reagents led to clean conversion of 6-thioguanine to N6-trifluoroethyl substituted 2,6-diaminopurine by 1H-NMR (see Supporting Information (SI)). We found by a LC-MS time-course that 6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine (s6dG) nucleoside was consumed within 5 min and the corresponding 2-aminoadenosine analogue (hereafter referred to as A*) was produced within 1h (Figure 1A).

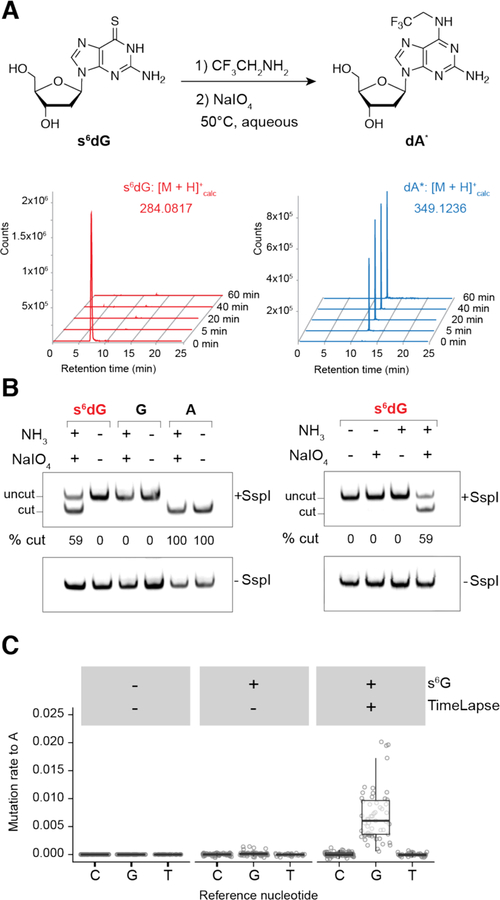

Figure 1.

(A) Extracted ion chromatograms corresponding to masses of of 6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine and 2-amino-6-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine. (B) Restriction digest assay of a DNA duplex containing a single 6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine, treated with 600 mM NH3 and 10 mM NaIO4 for 1 h at 45°C and subsequent digestion by SspI restriction enzyme (AATATT) and analysis by Native-PAGE. (C) Quantification of N to A transitions in ACTB mRNA sequencing reads. K562 cells were treated with 500 µM 6-TG for 1 h. Extracted RNA was treated with 600 mM TFEA and 10 mM NaIO4 for 1 h at 45°C.

From our previous work with s4U, we determined that recoding efficiencies of about 50% or greater are sufficient for monitoring RNA population dynamics.4 To assess the recoding efficiency of s6G in the context of an oligonucleotide, we chose to study a DNA oligonucleotide because of documented challenges incorporating s6G into RNA using prokaryotic RNA polymerases for in vitro transcription.14 We used an in vitro restriction digest assay with a single s6dG positioned at a site that creates an endonuclease restriction site upon successful recoding to dA* and PCR amplification. The majority (~59%) of the nucleotide s6dG was recoded to dA* in the context of a DNA duplex using ammonia in TimeLapse chemistry (Figure 1B). Similar results were obtained using different amines, including TFEA (see SI). These in vitro results led us to test whether we could use s6G to reveal RNA population dynamics of cellular RNAs.

We explored conditions to metabolically label cellular RNAs with s6G. While many photo-crosslinking studies use s6G nucleoside as a metabolic label12, we investigated the incorporation of either s6G nucleoside or 6-thioguanine (6-TG) nucleobase into cellular RNA and found similar incorporation (see SI). Due to the solubility of 6-TG, subsequent experiments were performed using 6-TG treated cells.

To test if we could use nucleotide conversion chemistry with s6G to examine the dynamics of cellular RNAs, we treated human K562 cells with 6-TG. The cells were grown for 1 h to allow time for incorporation of s6G into newly synthesized RNA. We did not observe significant toxicity even after 2 h treatment (see SI), consistent with previous reports for s6G.12 Total RNA was then isolated and subjected to TimeLapse chemistry, followed by targeted reverse transcription (ACTB mRNA, see SI) and next generation sequencing. Sequencing reads were mapped to the target transcript and the mutations of each nucleotide to adenosine were counted. We found that s6G is incorporated into newly transcribed RNA and consverted into A* as inferred from the increase in G-to-A mutations at all G nucleotides that were analyzed (Figure 1C and see SI). This conversion was 6-TG treatment and TimeLapse chemistry-dependent.

Having established the viability of using 6-TG to label cellular RNAs, we tested whether we could use 6-TG with TimeLapse chemistry to reveal RNA population dynamics transcriptome wide. We labeled K562 cells for 4 h, a labeling time optimized for studying the half-lives of mRNAs.1 Next we extracted total RNA from human K562 cells, treated the RNA with TimeLapse chemistry and subjected it to sequencing. Once the reads were mapped to the transcriptome we tested whether the 6-TG treatment substantially impacted RNA levels. Expression analysis revealed that the RNA levels from 6-TG treated cells were highly correlated with the levels from untreated and s4U-treated cells, indicating that the process of metabolic labeling does not substantially impact the transcriptome in the timeframe of the experiment (see SI, s6G vs. s4U Pearson’s r ≥ 0.96; s6G vs. untreated Pearson’s r ≥ 0.95). Analysis of the sequencing reads revealed a notable increase in G-to-A mutations (Figure 2A). The increase in G-to-A mutations tracked with transcript half lives (as determined using traditional s4U TimeLapse-seq), with transcripts that have the shortest half-lives demonstrating the greatest increase in G-to-A mutations (Wilcox test, p < 10−15; Figure 2B). Even transcripts with long half lives had a significant increase in G-to-A mutations upon 6-TG treatment (Wilcox test, p < 10−15). These trends were also apparent when examining individual transcripts (Figure 2C); transcripts with short half lives such as JUN had higher numbers of reads with G-to-A mutations than stable transcripts such as GAPDH (Figure 2C and see SI). As with targeted sequencing, this increase in the G-to-A mutation rate was only found in RNA from cells that had been treated with 6-TG.

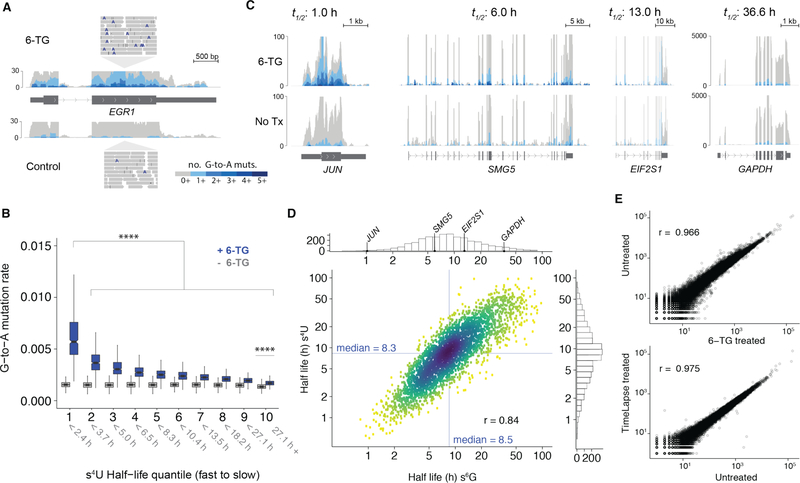

Figure 2.

(A) Metabolic labeling of cellular RNAs leads to G-to-A mutations at sites of s6G in sequencing reads shown for a region of the EGR1 transcript. (B) The distribution of average G-to-A mutation rate for each transcript separated by half life quantile (calculated from validated s4U TimeLapse-seq, 1 = high turnover, 10 = low turnover compared between transcripts from cells treated with 6-TG with identically treated RNA from untreated cells. **** p < 0.0001 based on a two sided Wilcox rank sum test. (C) Genome browser tracks for representative fast (JUN), intermediate (SMG5 and EIF2S1) and slow (GAPDH) turnover transcripts colored by the cumulative number of G-to-A mutations. Gray tracks represent all RNA-seq reads, with blue tracks representing the profile when only reads with the indicated number of G-to-A mutations are considered. (D) Correlation plot comparing transcript half-lives (log10 transformed) calculated using s6G TimeLapse-seq and s4U TimeLapse-seq. Histograms summarize the distribution of half-lives with the example transcripts indicated. The density of points is indicated by color (yellow, low; blue, high). (E) Correlation plots of RNA-seq profile comparing 6-TG versus untreated cells (top) and TimeLapse chemistry treated and untreated RNA (bottom) with Pearson’s correlation coefficient reported on each plot.

Each read from a TimeLapse-seq experiment reports on the mutational content of a single molecule of RNA that is either new (labeled) or pre-existing (unlabeled). We previously developed a statistical analysis of nucleotide recoding data using a binomial distribution to model the read distribution.4 Based on the number of G-to-A mutations in each read, accounting for new reads lost during handling, we calculated the fractions of new RNA that were produced during the treatment for over 4000 transcripts (see SI, Figure 2D). These fractions were reproducible across replicates (Pearson’s r = 0.92, see SI), and correlated well with results using s4U TimeLapse chemistry (Pearson’s r = 0.84, Figure 2D). Assuming simple exponential kinetics, we estimate RNA half-lives using these fractions (Figure 2C and 2D).

We found that known fast turnover transcripts such as transcription factors (e.g. JUN) have significantly shorter half lives than SMG5 or slow turnover transcripts such as GAPDH, consistent with previous reports (Figure 2D).4 Notably, using TimeLapse-seq with 6-TG allows us to estimate the half-lives of uridine-poor transcripts such as CBX4, whose reads have on average 10 uridine nucleotides, but 60 guanosine nucleotides (SI).

These results demonstrate that s6G can be used to monitor transcriptome-wide RNA population dynamics. Specifically, TimeLapse chemistry can be extended beyond s4U and can be applied to recode s6G to cause specific G-to-A mutations in sequencing experiments. While the lower incorporation rates of s6G15 lead to lower mutation rates induced by s6G compared with those induced by s4U (s6G 1.5%, s4U 4.5%), this rate is well above background (0.15% G-to-A mutations in TimeLapse treated or untreated samples without s6G) and allows analysis of the fraction of each transcript that is new. Half lives calculated from s6G TimeLapse-seq correlate well with those determined using s4U TimeLapse-seq (Figure 2D). Similar to s4U TimeLapse-seq, the chemical treatment and metabolic labeling with 6-TG preserve the information of traditional RNA-seq (Figure 2E) while providing insight into RNA population dynamics.

This nucleotide recoding chemistry adds a new technique to the larger set of experiments that use mutations to study nucleic acids including the analysis of epigenetic modifications through bisulfite sequencing16, RNA structure17–19, RNA-protein interactions12,20 and posttranscriptional modifications21. The impact of chemical approaches to reveal nucleic acids biology through mutational analysis continues to increase as sequencing technologies continue to evolve. TimeLapse-seq with s6G expands the power of nucleotide recoding by providing the first determination of RNA half lives using an analogue of guanosine and introduces the potential to analyze multiple timepoints using different metabolic labels in a single RNA-seq experiment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank A. Schepartz and S. Strobel for helpful comments on this manuscript. We thank E. Duffy and Simon lab members for insightful feedback.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by an AHA Predoctoral Fellowship (L.K.), the NIH NIGMS T32GM007223 (J.A.S.); NIH New Innovator Award DP2 HD083992–01 (M.D.S.), and a Searle scholarship (M.D.S.).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

The authors have applied for intellectual property rights for this work.

REFERENCES

- (1).Russo J; Heck AM; Wilusz J; Wilusz CJ. Methods 2017, 120, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Riml C; Amort T; Rieder D; Gasser C; Lusser A; Micura R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56 (43), 13479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Herzog VA; Reichholf B; Neumann T; Rescheneder P; Bhat P; Burkard TR; Wlotzka W; Haeseler von A; Zuber J; Ameres SL. Nat Meth 2017, 539, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Schofield JA; Duffy EE; Kiefer L; Sullivan MC; Simon MD. Nat Meth 2018, 15 (3), 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lee M; Kim B; Kim VN. Cell 2014, 158 (5), 980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gilbert WV; Bell TA; Schaening C. Science 2016, 352 (6292), 1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Harris CM; Zhou L; Strand EA; Harris TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113 (11), 4328. [Google Scholar]

- (8).MacMillan AM; Verdine GL. J. Org. Chem 1990, 55 (24), 5931. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Allerson CR; Chen SL; Verdine GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119 (32), 7423. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Melvin WT; Milne HB; Slater AA; Allen HJ; Keir HM. Eur. J. Biochem 1978, 92 (2), 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Woodford TA; Schlegel R; Pardee AB. Anal. Biochem 1988, 171 (1), 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hafner M; Landthaler M; Burger L; Khorshid M; Hausser J; Berninger P; Rothballer A; Ascano M Jr; Jungkamp A-C; Munschauer M; Ulrich A; Wardle GS; Dewell S; Zavolan M; Tuschl T. Cell 2010, 141 (1), 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Basu S; Rambo RP; Strauss-Soukup J; Cate JH; Ferré-D’Amaré AR; Strobel SA; Doudna JA. Nat. Struct. Biol 1998, 5 (11), 986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Basu S; Strobel SA. Methods 2001, 23 (3), 264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Baltz AG; Munschauer M; Schwanhäusser B; Vasile A; Murakawa Y; Schueler M; Youngs N; Penfold-Brown D; Drew K; Milek M; Wyler E; Bonneau R; Selbach M; Dieterich C; Landthaler M. Molecular Cell 2012, 46 (5), 674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Frommer M; McDonald LE; Millar DS; Collis CM; Watt F; Grigg GW; Molloy PL; Paul CL. PNAS 1992, 89 (5), 1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Siegfried NA; Busan S; Rice GM; Nelson JAE; Weeks KM. Nat Meth 2014, 11 (9), 959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zubradt M; Gupta P; Persad S; Lambowitz AM; Weissman JS; Rouskin S. Nat Meth 2016, 14 (1), 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sexton AN; Wang PY; Rutenberg-Schoenberg M; Simon MD. Biochemistry 2017, 56 (35), 4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).McMahon AC; Rahman R; Jin H; Shen JL; Fieldsend A; Luo W; Rosbash M. Cell 2016, 165 (3), 742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Shu X; Dai Q; Wu T; Bothwell IR; Yue Y; Zhang Z; Cao J; Fei Q; Luo M; He C; Liu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (48), 17213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.