Abstract

The identification and arrest of the Golden State Killer using DNA uploaded to an ancestry database occurred shortly before recruitment for the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) All of Us Study commenced, with a goal of enrolling and collecting DNA, health, and lifestyle information from one million Americans. It also highlighted the need to ensure prospective research participants that their confidentiality will be protected and their materials used appropriately. But there are questions about how well current law protects against these privacy risks. This article is the first to consider comprehensively and simultaneously all the federal and state laws offering protections to participants in genomic research. The literature typically focuses on the federal laws in isolation, questioning the strengths of federal legal protections for genomic research participants provided in the Common Rule, the HIPAA Privacy Rule, or the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Nevertheless, we found significant numbers and surprising variety among state laws that provide greater protections than federal laws, often filling in federal gaps by broadening the applicability of privacy or nondiscrimination standards or by providing important remedies for individuals harmed by breaches. Identifying and explaining the protections these laws provide is significant both to allow prospective participants to accurately weigh the risks of enrolling in these studies and as models for how federal legal protections could be expanded to fill known gaps.

Introduction

GEDmatch, a DNA database and genealogical resource for “amateur and professional researchers and genealogists,”1 played a critical role in law enforcement’s arrest of the notorious “Golden State Killer,” who had eluded police for decades.2 Using DNA collected from crime scenes, police were able to identify relatives of the suspect that ultimately led to the suspect’s identification and arrest.3 In the months following the Golden State Killer arrest, law enforcement has begun to use this technique to identify suspects for other unsolved crimes.4

Despite the clear benefits to law enforcement and to families who have long sought answers to crimes committed years ago, law enforcement’s use of these genealogy databases has raised concerns.5 After all, the people who uploaded their DNA did not do so for this purpose. The publicity over this use of consumers’ DNA led direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies, including well-known companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, to clarify their privacy policies.6

Although the Golden State Killer case did not involve a research database, its implications for research are significant. Indeed, as recruitment for the NIH’s All of Us study commenced, with its goal of enrolling and collecting DNA and other health information from one million Americans, NIH director Francis Collins and project director, Eric Dishman, sought to reassure potential participants that their data would be safe.7 Collins emphasized the NIH’s efforts to protect participants’ confidentiality, including obtaining a Certificate of Confidentiality that protects against subpoenas or other legal demands for research data, as an important mechanism for “getting people comfortable” with sharing their information.8 While the All of Us Study and the Million Veterans Program9 are among the most ambitious research studies in terms of scale and scope, researchers already hold DNA and health data from a large number of Americans.10

Privacy concerns are not limited to DNA databases. In January 2018, Strava, a GPS tracking company, published an interactive map based on data accumulated through fitness trackers and mobile phones, which then revealed classified military and intelligence facilities of the United States and other western countries.11 In March 2018, the New York Times reported that Cambridge Analytica12 had used data involving millions of Facebook users for election analysis.13 These examples illustrate the massive amount of information that may be collected, analyzed, and used, not always in ways individuals intend.14

For research projects like the All of Us study that seek to harness a broad range of data, including DNA, health information, and data from wearable devices or mobile apps, adequately addressing these privacy concerns is critical to earn public trust in the research enterprise. But there are questions about how well current law protects against these privacy risks. The literature is replete with discussion of the limits of the federal laws, including the Common Rule, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and its Privacy Rule, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), that may protect participants of such large-scale, national genomic research studies.15 While state laws that provide greater protections may fill in these gaps, until now, there has been no comprehensive analysis of what those laws provide and how they might work together to protect research participants. We undertook an empirical study how the federal and state laws work together to create a “web of legal protections” and to understand the limits of the web in protecting participant interests in genome research.16 This paper reports key findings from that study.

Like most empirical studies, this article proceeds in four parts. Part I sets forth a framework to describe the potential risks and corresponding legal protections for participants in genomic research, organized conceptually into three stages: research entry, the release of information from research, and unwanted use of research information after release. Part I also summarizes what is known and also what is poorly understood about the nature and substance, as well as existing gaps, within the web of legal protections for participants in genomic research. Part II describes our research methods used in identifying federal and state statutes and regulations that form the web of protections for participants in genomic research. Part III organizes the results of the research, describing the web of protections in four conceptual categories: (a) human subjects research laws, (b) laws specific to genetic information, (c) medical privacy laws, and (d) disability discrimination laws. Of these, the second category of laws specific to genetic information are of particular relevance to participants of genomic research. Part IV synthesizes our research findings and sets forth our discussion of the significance of these findings for participants, researchers, institutional review boards, and policymakers.

I. Background: A Framework for Mapping the Web of Protections

Large-scale genomic research offers unprecedented opportunities to learn more about human health and disease. The technological advances enabling genomic research, however, have also created conditions where genomic data can never be truly anonymized. Despite adherence to data security measures designed to protect participant anonymity, investigators have demonstrated that it is possible to discover the identities of participants based on genomic data that had been considered “de-identified.”17 This unsettling development poses privacy risks to research participants that, if unaddressed, could undermine individuals’ willingness to participate in research.

Good research practice has required that participants’ personal information be kept confidential through technological security measures, such as firewalls or encryption and by limiting use of identifiers, either through coding or, when scientifically feasible, rendering the data anonymous by removing identifiers entirely.18 Indeed, much genetic research has proceeded without consent under regulatory guidance and exceptions that assume that research would present very little risk to participants if the researchers do not have access to or record overt identifiers, such as names, medical record, and social security numbers.19

The assumptions underlying these regulatory exceptions have been challenged by a number of provocative studies that have demonstrated that deidentified genomic data may be re-identified without breaching data security measures.20 In response to the earlier of these studies, the NIH made a number of preemptive modifications to its policy for posting and accessing data contained in its genome-wide association study (GWAS) databases, including removing aggregate genotype data from public access, making them available only through a data access committee process.21 A 2013 study, however, described the ability to deduce individual identities even in the absence of a reference DNA sample, using only free, publicly accessible Internet resources, such as genetic genealogy databases.22 Although the inherent identifiability of genomic data has long been discussed,23 this development adds urgency to the challenge of protecting genomic research participants’ privacy while also ensuring that the data they contribute can be used for the greatest societal good.24

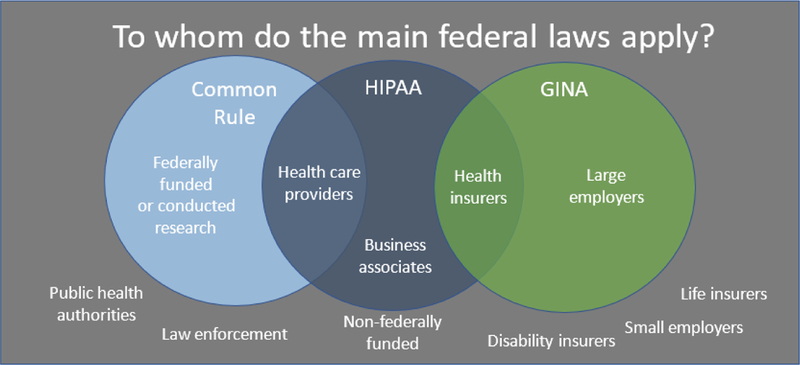

Although several federal laws provide protections to participants in genomic research, these laws also have known gaps. The federal laws include the Common Rule that regulates human subject research conducted or funded by the federal government,25 the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules that established minimum standards for protecting identifiable health information,26 and GINA that prevents large employers and health insurers from discriminating based on genetic information.27 Each of these laws establishes a minimum national standard but they are limited in their scope of protections. Although state laws that fall below these standards are preempted, state laws that exceed these standards must be followed.28 Figure 1 graphically represents some of the primary federal protections and the known gaps in those protections. These will be presented in more detail throughout the paper.

Figure 1.

Together, these federal and state laws that fill in these known gaps work together to provide what we refer to as the “web of legal protections” for research participants.

Nevertheless, the strengths and weaknesses of the cumulative web of protections created by federal and state law are poorly understood by participants and even researchers engaged in genomic research.29 At the same time, large-scale genomic research endeavors like the All of Us study (previously called The Precision Medicine Initiative) and the Million Veteran Program are each seeking to enroll a million individuals and gather genomic, health, and lifestyle data on an unprecedented scale.30 Thus, we undertook this research to develop a fuller understanding of the web of legal protections applicable to this type of large-scale genomic research with the goals of better informing prospective participants about the extent and limitations of these protections and to provide insight into updates to the legal protections that may be needed to adapt to a rapidly evolving research environment.

The range of risks to participants in genomic research and their corresponding legal protections can be organized in a framework that follows the participant’s information through time, starting from the initial research consent to the possible uses of the data were they to be disclosed outside the research enterprise. The first stage in the framework involves protections at study entry found in laws governing human subjects research. The second stage relies on protections against information release out of the research context found in genetic and health information privacy laws. If the information nonetheless escapes the research context, the third stage addresses protections against use of the information by third parties, including laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of genetic or other health information.

At the first stage, the primary research risks are that the participant’s data will be used for research purposes that the participant finds objectionable, such as to develop a commercialized product or in research that could be used in ways that could harm their identity or social group.31 The primary legal protections against this risk of harm are found in laws governing human subjects research. In particular are the Common Rule’s requirement for IRB review to minimize risks to participants (including assessment of confidentiality protections), as well as the requirement of informed consent, which protects participants by allowing them to decline to participate in the research if the risks of participation or the research purposes are objectionable.32 When research data is collected prospectively through interaction with the individual, as in the All of Us study, participants must consent to research participation.33 However, their research data may be used for secondary research studies to which the participant does not specifically consent, through broad consent for future research34 or through exceptions to the regulatory requirements, as described further below.35 Similarly, data collected for clinical or other non-research purposes may be used without consent for research purposes under the same regulatory exceptions.36

At the second stage, the primary risk is that the participant’s data will be released from the research context, either through a permitted or unauthorized disclosure. Such disclosure could result in a tangible harm, such as discrimination based on the information released, but unauthorized disclosure itself can be a dignitary harm stemming from the breach of the promise of confidentiality and the unwanted disclosure of information to others.37 The primary legal protection against the privacy harms of disclosure are privacy laws, in particular the federal HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules and, with respect to compelled disclosures from research, Certificates of Confidentiality. The HIPAA Privacy Rule offers scant protection to participants in genomic research. First, the HIPAA Privacy Rule may not apply to researchers or biobanks if they are not HIPAA “covered entities” or “business associates.”38 Furthermore, the Privacy Rule does not apply if the information has been de-identified under the terms of HIPAA, even if they are re-identifiable as demonstrated above.39 Even if the Privacy and Security Rules were to apply to the researcher or biobank and the participant’s information, there are several exceptions where the data could be disclosed outside the research context without the individual’s authorization.40 Of particular concern are compelled disclosures, where researchers may be subject to a legal demand by a court, administrative tribunal, or law enforcement to disclose an individual’s information pursuant to a court order, subpoena, warrant, or summons.41 Individuals’ information may be disclosed, without their knowledge, to law enforcement if they or a family member are identified as a potential criminal suspect.42 Certificates of Confidentiality, which apply to all NIH-funded research, are legal tools authorized by Congress that provide protection against compelled disclosure of sensitive, identifiable research data “in any Federal, State, or local civil, criminal, administrative, legislative, or other proceeding.”43 Certificates of Confidentiality were developed precisely to protect against compelled disclosure.44 Even with the uncertainty about the strength of its protection, legal counsel have been successful in using its authority to minimize production of research data and crafting protective orders when data are disclosed.45

The protections afforded by HIPAA and Certificates are directed at specific holders of information, covered entities and their business associates and research institutions, respectively.46 However, Certificates permit disclosures mandated by law.47 And the federal Privacy Rule permits disclosure without individual authorization for purposes of government investigation, national security, mandatory reporting obligations, or public health.48 Genetic or genomic data may also be returned to the individual,49 placed in the individual’s health record,50 breached or hacked, which also have implications as to whether and which privacy protections apply. Thus, our research identifies ways in which state laws may fill gaps in privacy protection available to genomic research participants under the federal HIPAA Privacy Rule and Certificates of Confidentiality.

At the third stage, the participant’s genomic and other data has been released outside the research context and there are risks that the information will be used against that individual to limit economic opportunities, such as employment or access to insurance.51 Other risks are that the information can be used for identity theft (including medical identity theft), that the individual will be targeted for unwanted marketing, or suffer embarrassment from having the information made public.52 The primary legal protections against these third-stage risks are laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of genetic, genomic, or other health information, including the federal Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and state laws that fill GINA’s gaps.53 These laws prohibit third parties, such as employers or health insurers, from using genetic or other health information in discriminatory ways.54 Nevertheless, GINA’s protections are limited—GINA only applies to employers with 15 or more employees, and it only applies to health insurers and not to life, disability, or long-term care insurers.55 When they understand GINA’s limits and the possibility of genetic discrimination, prospective participants may actually avoid participating in research based on fears of discrimination in insurance or other opportunities.56 Studies demonstrate that individuals avoid even clinically beneficial genetic tests over fear of misuse.57 Though largely anecdotal, stories of misuse and unauthorized disclosure have understandably raised concerns that such fears will thwart the potential benefits of genomic research.58

Given the known limits of federal legal protections, state laws can play a significant role in filling gaps in legal protections for research participants. But the extent, applicability, and variety of state laws that provide additional protections for genomic information are poorly understood. As stated by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues:

Current U.S. governance and oversight of genetic and genomic data … do not fully protect individuals from the risks associated with sharing their whole genome sequence data and information. In particular, a great degree of variation exists in what protections states afford to their citizens regarding the collection and use of genetic data.59

To address the uncertainty surrounding the patchwork of federal and state laws for acquiring, disclosing, and using genomic information, this project systematically catalogues and analyzes the ways in which state laws may fill known gaps in the federal protections for participants in genomic research. Though often overlooked, these state laws are significant for two reasons. First, they may provide substantive rights and stronger legal protections for participants who are subject to them, which may in turn affect descriptions of these protections and risks in the informed consent process. Second, they may offer models for how federal legal protections could be strengthened. The web of protections for participants in genomic research is what results when we analyze how state laws fill (or do not fill) the known gaps in federal legal baseline. The web of protections, taken together, offers genomic research participants uneven protections and highlights both the shortcomings of the federal laws, as well as a surprisingly robust degree of state action.

II. Methods

To identify laws that make up the “web of legal protections,” we conceptualized several different types of protections afforded by federal and state laws to participants in genomic research. These categories of laws correspond to the sequential framework described above. First, we considered the decision to choose to participate in genomic research and consent to genetic testing by researchers as a protection against the risks of research participation, namely objectionable research uses of the participant’s data. Second, we viewed genetic and health information privacy laws that limit disclosure of information – particularly when coupled with penalties for violation of those obligations – as the next layer of protection after information is obtained in research. The third and final layer of protections were laws that restrict access and use of participants’ information once it is released from the research context, and, thus, guard against third-party uses of the information against the participant’s interests.

Based on this 3-stage conceptualization, we identified several sets of laws that may provide protections to participants in genomic research. For stage one, we identified laws governing human subjects research and informed consent for genetic testing as the primary protections against objectionable research use of the participant’s information. For stage two, we focused on genetic and health information privacy laws as the main protections against the disclosure of data out of the research context. For stage three, we examined genetic discrimination laws and laws against unauthorized use of genetic information as the main protections against use of the data against the individual’s interests by third parties. In each of these sets, there were well-recognized, relevant federal laws.60 These include the federal regulations governing human subjects protections (the Common Rule),61 the HIPAA Privacy Rule,62 Certificates of Confidentiality,63 GINA,64 the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA),65 the Affordable Care Act (ACA).66 As noted in Part I, these federal laws establish a minimum standard, and all of them have known gaps. These laws also provide limited recourse for individuals who are harmed as a result of a breach. For example, an individual who suffers as a result of a breach in violation of HIPAA may bring a complaint to the United States Department of Justice’s Office of Civil Rights, but may not bring an individual claim against the entity who violated their HIPAA obligations.67 Finally, while these federal laws preempt state laws that offer less protection than the federal law does, state provisions that exceed the federal standards must be followed.68 Accordingly, we conducted searches to identify state laws that had provisions that added to the federal protections in some way.

We crafted formal search strategies to identify state laws for inclusion in our datasets.69 These strategies were developed in consultation with our legal librarians to yield comprehensive, relevant search results, using the Boolean and full-text search capabilities available in legal databases, Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis. We searched only for enacted statutes and promulgated regulations in effect between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017. We did not include bills or proposed regulations that were pending at the time of our searches and had not taken effect. Because Westlaw proved to have richer resources for statutory and regulatory research than Lexis-Nexis, our searches were conducted either exclusively in Westlaw or in both Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis; no searches were conducted solely in Lexis-Nexis. In addition to these searches, we used the book browse feature to ensure we had all relevant parts of statute or regulation, as not all sections would contain our search terms. We also compared our results to lists of relevant laws that had been gathered by others to ensure completeness of our datasets.70

We focused our analysis on laws that apply to how and when genetic testing may be conducted, protect the confidentiality of genetic information, and protect against uses of that information.71 Because our research focused on legal protections for participants in genomic research, we searched for laws that would apply to genetic information, tests, and biospecimens, and other health information used and held by researchers and biobanks. We also looked for laws protecting against unwanted use of genetic and other health information by employers, insurers, or “any person” if such information were to be disclosed, breached, hacked, or returned to the participant or their health care provider. There are numerous other laws—such as laws relating to use of genetic information in health care and operations (including licensure requirements of genetic counselors), in paternity or adoption scenarios, intestate succession, or regarding criminal law enforcement DNA databases—that we did not analyze as they are beyond the scope of our research question.72

Research team members worked in pairs to conduct searches and select relevant laws across all 50 states and the District of Columbia for inclusion in the datasets. Initially, each pair conducted searches for their assigned dataset independently and determined whether to include or exclude the law according to defined set of inclusion/exclusion criteria.73 The pair then compared their selections and any disagreements were resolved by discussion. If there were any lingering disagreements, a faculty member would make a final determination. Given the volume of laws we were encountering, we elected to limit the double searching to five states for comparison, with a check for consistency. Each member of the pair continued to review independently the list of search results to identify those laws for inclusion in the dataset and to compare them for agreement. We merged selections and sorted the data in Excel to allow for comparisons of all selections, rather than on a subset of the search results.

Once the searches for and section of relevant laws were complete, we proceeded to coding. We created a coding scheme that would capture both common provisions across the datasets (e.g., right and penalties), and provisions specific to particular datasets. The coding scheme was developed through a collaborative process within the team, during which we defined the different codes. Two independent coders coded each law in the qualitative software program NVivo.74 The research team met regularly to reconcile coding of individual laws and further develop the codebook as coding proceeded. After coding, we compiled summary tables of the relevant coded sections to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the various types of laws analyzed and to identify exemplars of specific kinds of provisions for further exploration. We then used coding reports that contain textual provisions by code, to this deeper exploration of specific types of protections. When necessary, we referred back to the relevant law for context. Any interpretive questions were identified and discussed among the faculty members.

Although we sought to compile a comprehensive picture of the laws relevant to our research questions, there are limitations to our research. We can only provide a snapshot of the laws in place at the times of our searching. Laws may have changed, been repealed, or adopted since our searches. In addition, although we tested and refined our searches based on existing information about relevant laws, it is possible that there are laws that our search terms did not identify. Given our focus on the privacy of genomic or health data held by researchers, laws that might otherwise fall within the broader topics we considered were excluded as not applying to the genomic research context we were studying. Finally, other types of laws that we did not consider may have provisions that expand on the protections we discuss here.

III. Results: The Web of Legal Protections for Participants in Genomic Research

We found substantially more state activity in each of the areas than we expected, and the types of issues these laws address extend beyond those addressed by federal law in unanticipated ways. For example, although the literature tends to refer to only a handful of state laws regulating human subjects research,75 we found that half the states have such laws. In addition, state laws are much more likely than federal laws to provide individuals with legal remedies for violations. Our findings from the different datasets follow.76 The results of the 50-state searches for laws protecting participants in genomic research are organized below under each of the four datasets: (A) human subjects research laws; (B) laws specific to genetic testing and information; (C) medical privacy laws; and (D) disability discrimination laws. In addition, each section includes a brief description of the “baseline” of requirements set forth under applicable federal laws.

A. Human Subjects Research Laws

1. Federal Regulation of Human Subjects Research

The primary federal law addressing human subjects research is the Common Rule.77 It applies to “all research involving human subjects conducted, supported, or otherwise subject to regulation by any Federal department or agency that takes appropriate administrative action to make the policy applicable to such research.”78 The Common Rule generally requires that research studies are reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB), which must, among other things, ensure appropriate consent to research participation, risks are minimized and reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, and selection of subjects is equitable.79

Although the Common Rule requires consideration of confidentiality protections, when applicable, it does not have any specific provisions that protect research data.80 Federal law authorizes protection of sensitive, identifiable research data from compelled disclosure through a mechanism called a “Certificate of Confidentiality.”81 Historically, the Secretary of Health and Human Services’ authority to issue Certificates was discretionary, whether the research was federally funded or not, and researchers had to apply for the protection.82 However, following the enactment of the 21st Century Cures Act, the Secretary must issue Certificate protections to federally funded research.83 In keeping with this change, the NIH will automatically issue a Certificate to any research it funds in which identifiable information is collected.84 At this point, however, researchers who are not NIH-funded must still apply a Certificate of Confidentiality to protect research data from compelled disclosure.85 This requires the researchers or their IRBs to be aware of Certificates and decide to apply. There is also the possibility that researchers who are not federally funded may not receive one, even if they do apply.86 The revised Certificate statute includes a new provision permitting disclosures in compliance with federal, state, and local law (except for compelled disclosures), which may undermine the Certificate’s protections, although a new provision making research data inadmissible as evidence in legal proceedings may mitigate the effects of this exception.87 Importantly, the revised Certificate statute explicitly provides that the protections against compelled disclosure apply to all copies of the data in perpetuity.88 Accordingly, if biospecimens are shared with identifiers, the Certificate’s protections would apply to subsequent studies using the data. A research biobank protected by a Certificate would be obligated to refuse to disclose its data, including biospecimens, even in a case like the Golden State Killer scenario, where law enforcement seeks to solve a serious crime.89

Research that involves prospective collection of biospecimens is subject to the Common Rule’s requirements for IRB review and participant consent.90 Consent provides a mechanism for individuals to decide whether to participate in research after being told of the relevant benefits, risks, and potential harms of participating in the research. Included in the discussion of potential risks and harms is a description of the relevant legal protections that may prevent or mitigate these harms.91 The consent requirement protects participants because it allows an individual who is risk averse, is concerned about a specified risk, or feels particularly susceptible to a harm to choose not to consent and, thus, not to participate.

Under the revised Common Rule, consent requirements for research involving identifiable data, biospecimens, and whole genome sequencing must describe whether identifiers will be removed, whether biospecimens will be used for commercial purposes, whether the individual can expect to share in any profits, and whether clinically actionable results of genetic testing or genomic sequencing will be returned to the individual.92 A corollary to the right to consent to research participation is the right to withdraw.93 In the context of biospecimens research, the right to withdraw might best be conceived of as a right to revoke consent to further use of the biospecimens.94 There may also be some practical constraints on this right, permitting researchers to retain data already collected from the biospecimen and recognizing that it may not be possible to stop use of biospecimens that have been deidentified, whether they have been shared or not.95 Assuming a participant’s data and specimens are collected appropriately pursuant to Common Rule requirements, there is no federal restriction preventing researchers or biobanks from storing and using such research data or specimens indefinitely. Although researchers may promise to destroy data and samples to the extent they can be identified as that participant’s if she withdraws consent, if the participant does not act, consent does not expire.96 The researchers are not obligated to destroy the data and no expiration of consent by operation of law for continued future use of data and samples for research.97

There are several gaps to the application of the Common Rule. First, the Common Rule applies only to “research” involving “human subjects,” as these terms are defined in the regulations.98 Pursuant to Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) guidance,99 research involving only coded specimens does not constitute human subjects research if it meets certain conditions. These conditions include that the specimens were not collected specifically for the proposed research through interaction or intervention with a living individual and the investigator cannot readily ascertain the identity of the individuals whose specimens are used.100 Accordingly, such research is not considered human subjects research and is not subject to the consent and IRB review requirements of the Common Rule. If specimen research is considered human subjects research, it still may be exempt from the Common Rule if it involves existing specimens that are either publicly available or the “information … is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects …. .”101 While the IRB may, but is not required to, review the protocol to ensure it meets with the exemption, consent would not be required.102 Finally, human subjects research that does not fit the exemption for existing specimens may be conducted without consent if the researcher can demonstrate it is eligible for a waiver of the consent requirement.103 Thus, with respect to secondary research with biospecimens, there are three ways that genomic research may be conducted without consent, and two ways that such research may be conducted without IRB review.104

That the Common Rule does not extend to non-federally funded research is another well-recognized gap.105 Although many institutions have voluntarily agreed to apply these regulations to all research conducted at their institutions in their “federalwide assurance,” some institutions have “unchecked the box” so that they are not required to apply the regulations to non-federally funded research.106 Research conducted outside of institutions with a federalwide assurance and without federal funding would fall entirely outside the scope of the Common Rule’s protections.107

Finally, the Common Rule does not provide a right of action nor corresponding remedies for individuals who are harmed as a result of violations of its provisions. While OHRP oversees compliance with the Common Rule and may respond to participant complaints, its enforcement actions are directed at researchers and their institutions.108 Aggrieved individuals may bring state law tort claims, based, in part on the obligations enshrined in the regulations, however, there are many obstacles to a successful claim.109

2. State Regulation of Human Subjects Research

Discussions about human subjects research in the literature almost exclusively focus on the federal regulations,110 with little mention of state human subjects protections laws, and then only a few well-known examples, in particular, California, Maryland, and New York.111 However, we found that five states substantially expand upon the Common Rule’s protections in scope or substance for participants in genomic research, although they do so to a different extent. Other states close gaps in the Common Rule in a more incremental fashion.

There are four states – California,112 Maryland,113 New York,114 and Virginia115 – that have laws that apply to human subjects research when the Common Rule does not, namely to non-federally funded research. However, even under these laws, some of the Common Rule’s gaps pertaining to secondary research persist. For example, California, Virginia, and New York permit secondary research without consent using specimens collected for other, non-research purposes.116 Maryland’s picture is more complex. It adopts the federal definition of “human subject,”117 but also explicitly applies federal Common Rule requirements to “all research using a human subject.”118 On its face, the latter provision seems to prevent research that meets one of the federal Common Rule’s exemptions from avoiding avoid the regulatory requirements. However, the Maryland Attorney General indicated that this was not the intention of the statute.119 Accordingly, if Maryland chooses to follow OHRP guidance that some secondary research with biospecimens is not human subjects research, this statute would not change how biospecimen research is treated.120 Interestingly, New York limits who can conduct human subjects research to “researchers,” which are defined as medical professionals or those who an IRB deems qualified.121 By restricting who may conduct research, New York may further limit the number of human subjects who might otherwise fall outside the federal regulations.

Another approach taken by states expands on the Common Rule by applying broader legal protections to research in particular contexts or populations.122 These laws would apply to genomic research conducted in these settings or populations but would not apply more generally. In contrast, Oregon has specific provisions that apply to genetic research.123 Although Oregon permits holders of genetic information to disclose it without consent for anonymous and coded research, Oregon law requires all genetic research to go to an IRB for “explicit prior approval or an explicit determination that the research is anonymous or otherwise exempt.”124 This is more prescriptive than the federal approach, which recommends, but does not require, that institutions review potentially exempt research to confirm that determination.125 In submitting the research to the IRB, Oregon requires researchers to “disclose to the IRB the intended use of human DNA samples, genetic tests or other genetic information for every proposed research project, even anonymous or otherwise exempt research.”126 There is no exception for federally funded research. This requirement has significant implications, particularly for secondary use studies, as it requires IRB review for secondary research that the Common Rule permits to proceed without IRB review. These choices are deliberate, as Oregon’s law also notes that “these rules set state standards that are in addition to, and not intended to alter, any requirement under the Federal Common Rule or the Federal Privacy Rule.”127 Oregon also imposes obligations on the recipient of a limited data set of genetic information, which may limit secondary research using that data set.128

Although the Common Rule requires IRBs to consider confidentiality protections undertaken by the researcher, it does not have any specific provisions to protect research data, and the Certificate’s protections to not automatically extend to non-NIH funded research.129 A few states fill these gaps by providing additional confidentiality protections to research data.130 Most protective are Arkansas and Oklahoma; their laws protect the research records of subjects in “genetic research studies” from “subpoena or discovery” in civil (not criminal) lawsuits, except when “the information in the records is the basis of the suit.”131 Both of these laws apply broadly to all genetic research approved by an IRB or conducted in accordance with the Common Rule or the FDA regulations.132 Unlike the federal Certificate of Confidentiality, it does not depend on federal funding or require an application. However, because the Arkansas and Oklahoma protections rely on IRB approval or compliance with the federal regulations, they may not apply to secondary research when specimens are not identifiable because such research would not require IRB review under federal requirements. Louisiana provides that identifiable information held by researchers in public universities, medical schools, and colleges is not available for subpoena and is not discoverable.133 This law provides similar protections to the Arkansas and Oklahoma laws, but it is not restricted to genetic research. On the other hand, Louisiana’s law only applies to research conducted at public institutions, a substantial limitation. Kentucky provides that identifiable research information is “confidential” and cannot be disclosed to someone outside the research team without consent, but it does not explicitly address subpoena or discovery.134

Only California and Maryland discuss remedies for violation of human subjects protections obligations. California provides for civil damages, criminal fines, imprisonment, attorney’s fees, and court costs for conducting research without consent.135 A researcher who negligently permits research without consent shall be liable to the subject for a minimum of $500 in damages and a maximum of $10,000, and willful failure to obtain consent is subject to minimum damages of $1,000 and a maximum of $25,000.136 Maryland authorizes the Attorney General to seek injunctive of other relief “to prevent violations” of its human subjects research law.137 It does not discuss remedies for the participants affected by any violations.

3. State genetics laws with implications for human subjects research

Several states require the individual’s written consent to retain genetic materials or information.138 These provisions may be coupled with obligations to destroy samples that could limit future research using the biospecimens. For example, Delaware requires prompt destruction of genetic materials, except if needed for criminal or death investigations or proceedings, a court orders retention, the individual authorizes retention, or for “anonymous” research in which the identity of the individual is not disclosed.139 New Jersey provides that “a DNA sample from an individual who is the subject of a research project shall be destroyed promptly upon the completion of the project or withdrawal of the individual from the project, whichever occurs first, unless the individual or the individual’s representative directs otherwise by informed consent.”140 It also provides:

The DNA sample of an individual from which genetic information has been obtained shall be destroyed promptly upon the specific request of that individual or the individual’s representative, unless: (1) Retention is necessary for purposes of a criminal or death investigation or a criminal or juvenile proceeding; or (2) Retention is authorized by order of a court of competent jurisdiction.141

These laws suggest that that they would prohibit a researcher from deidentifying a specimen and continue to use it for research after withdrawal of consent, as permitted under the federal regulations.142 Texas requires destruction of genetic material after “the purpose for which [it] was obtained is accomplished unless” it was obtained for IRB approved research and retention is either required or authorized by the participant.143

There are some common exceptions to the requirement for consent to retain genetic material. These primarily include: retention for public purposes, such as law enforcement (including criminal DNA databases), paternity determinations, newborn screening, by court order, or otherwise authorized by law.144

Similar to the right to withdraw consent to participate in research, several states explicitly grant individuals the right to revoke an authorization to use or disclose genetic information. Louisiana law not only grants the right to an individual to revoke the authorization before disclosure, but it invalidates the authorization if used for any improper purpose.145 Accordingly, any research use not covered by the original consent would invalidate the authorization and could subject researchers to penalties. Minnesota and Washington also grant the right of revocation.146

Finally, a few states have specific provisions limiting the research use of genetic information, but these are limited to newborn spot specimens.147 While they require researchers to return or destroy unused newborn spot specimens obtained from the state,148 cutting off further secondary uses that might otherwise be permissible, these do not apply to materials originally obtained for research.149

As this section demonstrates, a handful of states have laws that fill in some of the gaps in the federal laws governing human research protections. These include a handful of states that have laws that apply to human subjects research when the federal regulations do not, and one, Oregon, that has specifically requires IRB review for all genetic research, including some genetic research that would be exempt from IRB review under federal law. There are also a few states that have adopted specific confidentiality protections that extend beyond federal requirements. Finally, California provides for remedies, including minimum damages for subjects involved in research without their consent.

B. Laws Regarding Access, Use, and Disclosure of Genetic Information

1. Federal Genetic-Specific Laws

One of the main risks of participating in genomic research is that the genomic information will be released beyond the confines of the research study and be used against the individual.150 The primary federal law addressing access, use, and disclosure of genetic information is GINA. Substantively, GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from requesting or requiring prospective or current employees or insureds to submit genetic information, undergo genetic testing, or reveal whether the individual or family member has undergone genetic testing.151 In this way, GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from accessing a person’s genetic information.152 GINA also limits how employers and health insurers may use and disclose genetic information that they may receive. Employers may not make hiring, termination, promotion, or other adverse employment decisions on the basis of genetic information or the fact that an employee or family member has undergone genetic testing.153 Health insurers may not make underwriting decisions, such as whether to offer coverage or setting premiums, based on genetic information and may not require applicants or enrollees to undergo genetic testing or submit genetic information in connection with enrollment or underwriting.154 This feature of GINA was incorporated into the Affordable Care Act’s federal requirements for health insurance plans, which prohibit making coverage determinations or setting premiums upon genetic information or upon health conditions.155 Finally, GINA extends confidentiality protections to genetic information, defining genetic information as “protected health information” (PHI) under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, discussed below.156 GINA also requires employers to keep any genetic information they may have about employees or applicants in separate, confidential medical file and prohibits disclosure of genetic information except for limited purposes.157

GINA’s protections contain notable gaps. First, the employer provisions of GINA only apply to employers with 15 or more employees and therefore do not apply to the approximately 17 million people (almost 15% of all employees), who work in companies with less than 15 employees.158 Second, GINA’s insurance provisions only apply to health insurers and do not apply to other forms of insurance, such as disability, life, or long-term care insurance. Given the aging population and the importance of these forms of insurance to provide financial security to a large and growing segment of the population (and their familial caregivers), GINA’s inapplicability to these other forms of insurance is a significant gap.159

2. State Genetic-Specific Laws

Every state except Mississippi has a law that addresses genetic testing, privacy, or discrimination in some form.160 Collectively, we refer to these laws as “genetic-specific laws.” In some cases, these laws are coextensive with federal protections under GINA, but we found a number of instances in which states go beyond the federal minimums, closing gaps in protection offered by federal law.

As a threshold question, we had to consider whether state laws that apply to genetic testing or information would apply to analyses conducted for research purposes. We found that these laws rarely explicitly apply to research.161 But they also rarely explicitly exclude research from their reach.162 When we did find genetic testing and information laws that excluded research, the exclusion applied only to research conducted under the Common Rule or FDA regulations.163 A few laws do not explicitly limit their application to clinical purposes, but their use of the term “diagnose” suggests such a limitation.164 These examples provide support for our interpretation that states with broad definitions that neither exclude research from their laws or nor define genetic information in terms of clinical uses may apply to research.165 That some states exclude non-clinical types of genetic testing suggests that other states could exclude research should they desire.166 Thus, unless a state law referencing genetic testing or genetic information specifically excluded research or explicitly limited applicability to clinical or diagnostic contexts, we concluded the law could apply to the genetic tests and information of participants in genomic research. There are two independent reasons for taking a broad view of these laws. First, identifying which genetic mutations are associated with specific diseases or conditions is one of the main purposes of genomic research,167 even if the links are not yet confirmed. Second, in the context of whole genome sequencing, the information generated is likely to include genetic mutations whose associations with disease are known, as well as mutations of unknown significance.168

Using these analytical frameworks, we found states’ legal activity in this category is substantial, both in volume and variety. A number of states have passed laws regulating genetic testing or information in ways that go beyond the federal requirements. Notably, state laws create substantive individual rights to control genetic information or assert claims for damages in the event genetic information is inappropriately used or disclosed. The results of our research into state laws specific to genetic information and testing are organized under the following subcategories: (a) laws requiring consent for genetic testing; (b) laws restricting access to or use of genetic information; (c) laws restricting disclosure of genetic information; and (d) laws creating individual rights regarding one’s own genetic information. The results are discussed in detail below.

a. Laws requiring consent to genetic testing

Ten states require written informed consent for genetic testing.169 This is significant because there is no federal requirement for informed consent for genetic testing. While the Common Rule may require written informed consent for individuals to participate in research, including prospective collection of biospecimens for genomic research, it may not require a separate written consent for secondary research or genetic testing of biospecimens.170 To the extent it applies to the research context at all, the HIPAA Privacy Rule’s authorization requirement does not apply to information that has been de-identified.171 Therefore, there may be instances where researchers genetically test specimens without seeking written informed consent or authorization from the individual. Moreover, because GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from requesting or requiring individuals to undergo genetic testing,172 GINA does not speak to whether written informed consent is required for genetic testing.

Most of the states’ statutes are written broadly to apply to “any person” (or “no person” when written in the negative) and thus include researchers in their scope.173 In these states, researchers would have to obtain individual consent to conduct genetic testing on research specimens even if such research would not have required consent under federal law. Oregon’s law is unique in explicitly addressing consent for genetic research. It permits “anonymous” and “coded” research using specimens or genetic information if the individual consents to the specific research project, consents to genetic research generally, or was notified that her information may be used in such research and did not request that her information not be used.174 Researchers likely prefer the last approach because it sets the default as permitting research use unless the individual objects. Research in choice architecture suggests that people are more likely to choose the default option.175

Some of the state laws requiring written informed consent for genetic testing only apply to physicians or other health care providers and, therefore, may only apply to genomic research if it is conducted by physician-investigators.176 Florida requires consent for genetic testing, without specifying that it must be written,177 although in practice consent is likely done in writing.

Contrary to what is required under federal law, in many states, researchers would need to obtain consent, sometimes specific or written consent, to conduct genetic testing on samples from participants in genomic research. Given how broadly many of these statutes are written, it seems that consent would be required even for secondary research.

b. Laws limiting disclosure of genetic information

The primary federal law regulating the disclosure of health information, including genetic information, is the HIPAA Privacy Rule.178 The HIPAA Privacy Rule includes genetic information in the definition of “health information,”179 but the Privacy Rule is limited by its applicability only to HIPAA covered entities or their business associates.180 The HIPAA Privacy Rule generally requires individual authorization to disclose identifiable health information, but there are several exceptions allowing for disclosure without authorization, such as for law enforcement purposes, pursuant to a court order or subpoena, or to public health or other governmental authorities.181 Significantly for participants in genomic research, the HIPAA Privacy Rule may have limited applicability to researchers or biobanks that gather, store, and use genomic data, particularly if those researchers receive the data directly from the participant rather than from health care provider that is covered by the Privacy Rule.182 To the extent that researchers and biobanks de-identify the information or data such as through the use of codes instead of individual identifiers, the HIPAA Privacy Rule’s protections would not apply.183 Moreover, once genetic data escapes the realm of regulated institutional holders (to the extent they are covered entities or their business associates under HIPAA), either through return of results to the participant, breach, hacking, or permitted disclosure (e.g., subpoena or court order), the information is entirely beyond the reach of HIPAA. As noted above, GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from disclosing genetic information of employees, enrollees, or applicants.184 This is an area where state laws are particularly significant—both in their number and in the substantive ways that states fill the gaps in protection left by GINA and HIPAA.

i. Consent to disclosure of genetic information

As noted above, the HIPAA Privacy Rule may not apply to the researcher, biobank, or any other subsequent holder of a participant’s genetic information. States broaden the privacy protection offered by requiring consent to disclosure beyond HIPAA covered entities. Sixteen states prohibit any person, including corporations and entities, who holds information obtained through genetic testing from disclosing the information without the individual’s consent, although some of these laws also have exceptions.185 For example, Nevada provides “[i]t is unlawful to disclose or to compel a person to disclose the identity of a person who was the subject of a genetic test or to disclose genetic information of that person in a manner that allows identification of the person, without first obtaining the informed consent.”186 These restrictions on disclosure would apply both to researchers and biobanks as well as third parties who may subsequently obtain individuals’ genetic information if it were to escape the confines of research.

In addition to these general prohibitions on disclosure of genetic information without consent applicable to any person, states also restrict specific entities from disclosing genetic information. Fifteen states restrict employers’ disclosure of genetic information.187 Vermont restricts disclosure of genetic information to employers.188 California restricts disclosure by insurers.189

Should genetic information get into the individual’s medical record (such as through automatic placement of genomic information into the medical record or through the return of research results to the participant), Arizona’s and Washington’s statutes provide additional protections by imposing obligations on those seeking to access genetic information from providers through a subpoena or discovery request to provide opportunities to limit disclosures through protective order or other judicial mechanisms.190

ii. Confidentiality protections for genetic information

Numerous states provide confidentiality protections for genetic information that extend beyond the protections offered to health information under federal or state laws regarding privacy of non-genetic health information. To the extent they impose a broad obligation upon holders of genetic information to maintain confidentiality of such information and refrain from disclosure, these state laws fill a gap in the HIPAA Privacy Rule by extending obligations beyond HIPAA covered entities191 to the researcher, the biobank, and any subsequent holder if the genetic data of research participants were to get out from the research context.

In some cases, the confidentiality protection is constructed so broadly that its scope is unclear. Examples include Arizona, Colorado, and Georgia,192 which declare genetic information “confidential” and “privileged” without specifying what that means.193 Several states include general statements that genetic information is confidential and may only be disclosed with consent of the person tested.194 The scope of these laws is unclear because they do not necessarily specify to whom the confidentiality obligation applies.

There are mechanisms, such as mandatory public health reporting requirements, that could allow information held by researchers to be disclosed to government officials. Many states do, however, extend confidentiality protections to genetic information held by government agencies and officials (such as public health departments, newborn screening programs, and disease registries) and may protect such information from state open records requests.195 Such protections may provide some reassurance to research participants. However, there are a myriad of exceptions to confidentiality obligations of state or governmental holders of genetic information.196

Several exceptions include those that participants would likely expect, such as disclosure to the person tested or their legally authorized representative, to medical providers or other medical personnel, for treatment or payment purposes, or when the person tested consents (typically in writing). Some states also allow disclosure to relatives for medical purposes if the person tested is deceased. However, other exceptions might surprise research participants, especially given their breadth. These include disclosures for public health purposes, newborn screening, abuse and neglect reporting, research, law enforcement (including identification of persons), paternity determinations, and to monitor legal compliance. There are also exceptions for quality improvement purposes, such as for peer review, utilization review and quality assurance, for health care operations, or other business operations. Other exceptions include: when the person tested brings a lawsuit or other complaint or genetic information is placed at issue in litigation or pursuant to a court order; as authorized or required by law; for marketing; and for due diligence in sale of business.

iii. Laws against compelled disclosure

The Golden State Killer case highlighted the value of genetic information for law enforcement in the identification of suspects.197 Legal demands for genetic information could also stem from civil cases, such as family law disputes or personal injury matters.198 While genomic research databanks may be particularly attractive for law enforcement or civil legal demands, any holder of genetic information could be subject to a legal demand, and federal laws generally do not shield holders other than researchers from having to comply.

No federal laws protect genetic information generally from compelled disclosure via court order or subpoena, although, as described above, federal law authorizing Certificates of Confidentiality and a handful of state laws may protect some research data from compelled disclosure.199 To the extent the information holder is a covered entity, the HIPAA Privacy Rule permits disclosure of PHI without individual authorization to law enforcement to help identify a suspect or in response to a legal demand, such as a subpoena, court order, or warrant.200 For civil legal demands, the HIPAA Privacy Rule permits disclosure of PHI pursuant to a court order or subpoena without individual authorization if the covered entity receives evidence that there were reasonable efforts to notify the individual about the request to allow the individual to object and to seek a qualified protected order for the information from the court.201

Several states more broadly shield any holders of genetic information from compelled disclosure. Texas protects any person against compelled disclosure of an individual’s genetic information without the individual’s consent.202 Delaware, Illinois, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Oregon also provide broad protections for any holder of genetic information from compelled disclosure,203 but with more exceptions than the Texas law.204 These laws would arguably protect researchers and biobanks from compelled disclosure of genetic information pursuant to a subpoena, but they would also apply to other holders of the information if the information were to be released from the research context, such as through a return of research results to the individual or their physician or through breach or hacking. However, with the exception of Illinois, these laws do not protect researchers and biobanks from disclosing genetic information pursuant to a court order.

Utah’s law allowing for compelled disclosure of genetic information is much more restrictive. Such orders must limit disclosure to the parts “essential to fulfill the objective of the order” and to those persons who need access, as well as including other measures necessary to protect the individual.205 Illinois’ law is unique, declaring genetic information inadmissible in legal proceedings.206 This provision can protect an individual’s information from being used against them, even if the information is somehow disclosed.

In sum, state laws creating confidentiality protections for genetic information are significant in a couple ways. First, this is an area where the gap in federal protection could be significant if the research institution declines to extend HIPAA covered entity status to its researchers and biobanks. Moreover, subsequent holders of genetic information gathered through genomic research are not likely covered by the requirements of HIPAA. Nevertheless, the mere designation of genetic information as “confidential,” without more, may offer few substantive protections to the affected individual, particularly given the numerous exceptions to this general rule. But the second significant finding is that some states extend substantial protections against disclosure by the researchers or indeed any holder of genetic information, however obtained. Perhaps the most important of these are protections against compelled disclosure through subpoena for researchers or any other holder of genetic information.

c. Laws restricting access to or use of genetic information

As discussed above, GINA prohibits health insurers and employers with 15 or more employees from requiring, requesting, or conditioning approval or employment on the submission of genetic information. State laws can go beyond GINA’s requirements by extending the prohibitions on access to smaller employers, other types of insurance, or other non-employer or insurance entities.207 These legal protections are relevant to participants in genomic research because of the potential for genetic information to escape the confines of research use and be accessible to employers, insurers, or others who may have an interest in an individual’s genetic information. The primary ways that genetic information could be accessed from the research context are through inclusion of genomic information in the medical record,208 return of the results of genetic testing to the individual and their health care provider, authorized disclosure such as through subpoena or court order, breach, or hacking.

GINA also prevents the use of genetic information by employers in making employment decisions, including hiring, firing, promotions, and access to other benefits.209 GINA and the ACA prevent health insurers from using genetic information to determine eligibility, benefits, or premiums.210 The gaps in GINA’s protections, described above, limit its applicability to employers with fewer than fifteen employees or other types of insurance providers, such as disability, life, or long-term care insurers. Although the HIPAA Privacy Rule generally requires authorization for use as well as disclosure of individually identifiable health information, it may have limited applicability to researchers, biobanks, and subsequent holders of research participants’ genetic information.211

States impose a variety of limits on analysis or use of genetic materials or information that apply beyond the limits of GINA or the HIPAA Privacy Rule. A few states broadly limit use of genetic information by any person without consent.212 The restrictions that states impose on analysis or use of genetic information are important to protecting research participants from the risk that genetic information generated in research could be used against them in the event that the information escapes the research context.213

To address the concern that genetic information can be used to limit employment, insurance, and other opportunities, states have passed a variety of laws to fill GINA’s gaps by extending prohibitions on use of genetic information to a broader range of employers, other types insurers besides health insurance, and even other contexts.

i. Employment

Seventeen states apply prohibitions on employer access to or use of genetic information where GINA does not because they define employer to include those with less than 15 employees. As Table 1 illustrates, 11 of these applying to employers with only one employee, and the remainder apply to employers with up to five employees (Table 1).214

Table 1.

| Minimum employees to come under state discrimination laws | States |

|---|---|

| 15 | MD |

| 5 | CA, ID |

| 4 | NY |

| 3 | CT |

| 2 | IA, RI |

| 1 | AR, DC, MI, MN, OK, OR, UT, VT, VA, WA, WI |

| Unspecified | NH, SD |

At least two states explicitly prohibit employers from obtaining consent to testing by offering employees a benefit.215 These prohibitions contrast with GINA, which permits limited rewards or penalties in the context of voluntary wellness program.216 Rhode Island, on the other hand, does not allow employees to waive protections with respect to genetic information.217

ii. Insurance

Regarding access, four states go beyond GINA by applying restrictions on use of genetic information to insurance other than health insurance. Vermont prohibits all insurers – specifically including life, disability, and long-term care insurance – from using genetic information for underwriting, providing: “No policy of insurance offered for delivery or issued in this state shall be underwritten or conditioned on the basis of: (1) any requirement or agreement of the individual to undergo genetic testing; or (2) the results of genetic testing of a member of the individual’s family.”218 Colorado and California restrict collection of genetic information by disability insurers, however, California’s law is limited to disability insurance for hospital, medical, and surgical expenses.219 Colorado and Maryland restrict collection of genetic information by long-term care insurers.220

Regarding analysis and use of genetic information by insurers, a few states go beyond GINA and prohibit use of genetic information in disability insurance underwriting outright221 or restrict its use in disability insurance underwriting unless its use is “based on sound actuarial principles or actual or reasonably anticipated claims experience.”222 While the latter approach is less protective, it seems likely to provide some protections to research participants, as much of the genetic information from whole genome sequencing will be of uncertain clinical significance and many conditions are multifactorial and the relationships may not be known.223 Such genetic information is unlikely to provide the kind of actuarial justification to permit their use in underwriting. On the other hand, research involving whole genome sequencing may also generate information that has known clinical significance, and disability insurers would not be restricted from using that information in underwriting. Wyoming prohibits disability insurers from treating genetic information as a preexisting condition in the absence of a diagnosis of a condition related to genetic information.224 While this does not prohibit its use in underwriting, it does provide protection against denial of coverage should a claim arise.

A few states also prohibit use of genetic information225 or limit its use unless it is based in “sound actuarial principles”226 in long term care insurance. Only Vermont prohibits use of genetic information in underwriting for life insurance, although California and Maryland prohibit underwriting based on genetic carrier status.227 A few other states do restrict its use unless such use is based on “sound actuarial practice or actual or reasonably anticipated claim experience.”228

iii. Other

Though GINA’s prohibition on collecting or requesting genetic information does not extend beyond employers or health insurers, we found a number of states that expand prohibitions on use of genetic information beyond GINA to a range of other areas, such as housing, education, and financial transactions.229 Some prohibit discrimination based on genetic information to places of public accommodation, which is an expansive protection to a variety of business that offer services and products to the public.230

Iowa includes genetic information as part of “identification information” for purposes of its identity theft law.231 Vermont explicitly limits putting some genetic specimens into criminal databases. This includes specimens “collected voluntarily,” suggesting that specimens collected with consent for research could not be placed into these databases.232

iv. Exceptions in state laws limiting use of genetic information

There are numerous exceptions to the state law restrictions imposed on analyzing or using genetic information described above.233 These not only may undermine or narrow the protections, but also make it more challenging to describe the protections to participants in genomic research.

For example, states may permit genetic information to be used without individuals’ knowledge or consent for paternity testing, newborn screening, law enforcement purposes, or criminal DNA banking.234 In addition, consistent with GINA (but typically not included in consent forms), states may permit employers to use genetic information for determination of bona fide occupational qualifications, workers’ compensation claims, and worker safety (e.g., to monitor toxic exposures).235

In sum, states extend GINA-type prohibitions on the collection, access, or requesting of genetic information to entities that are not subject to GINA to varying degrees. One-third of states provided GINA-type employment protections to employers with five or fewer employees. Only a few extended protections to non-health insurance and several states extend genetic discrimination protections beyond employment or insurance such as to housing or education, suggesting that affording such protections is possible. One fear often expressed about expanding GINA’s scope is that it would be economically unworkable to extend prohibitions on genetic discrimination to other contexts, including smaller employers, other forms of insurance, educational, or economic opportunities. While empirical study may yet reveal these provisions are largely symbolic and difficult to enforce, the fact that several states have expanded the scope of genetic anti-discrimination may suggest that such expansions are economically feasible.

d. Individual rights created

One of the primary ways states fill in gaps in the federal laws protecting participants in genomic research is to extend broader private rights to the individual. The federal laws offer few legal remedies or enforceable rights for individuals aggrieved by violations of these federal requirements; the Common Rule is silent as to remedies, there is no private right of action (right to sue) under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, although a violation could serve as evidence for a state tort claim,236 and GINA limits recovery.237 The enforcement mechanisms under these federal laws focus on administrative penalties rather than conferring individual causes of action. Thus, perhaps the most significant way that states expand upon the protections offered to participants in genomic research is to provide private rights of action and statutory remedies for violations of state laws limiting access, use, and disclosure of genetic information.

Aside from private enforcement, states may build upon the federal standards by offering individuals more specific rights to access and control their genetic information than offered under federal law, including rights to notification about what is done with the individual’s information, right to access information, right to request the destruction of the individual’s biospecimens or samples, or property rights in one’s genetic information. Given the focus of this project, we have only included laws that are written broadly enough that they could be interpreted to apply to research-related holders of genetic information.

i. Enforcement rights

State laws regarding access, use, or disclosure of genetic information distinguish themselves from their federal counterparts by providing remedies, penalties, or both for violations of their requirements. Twenty-six states create a private right of action for violation of their various genetic-specific laws.238 Eight states make violations of laws regarding genetic information a violation of the state’s unfair or deceptive trade practice statute.239 Unlike the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA),240 which may only be enforced by the FTC,241 most state unfair trade practice laws permit private causes of action, allowing individuals to recover compensatory damages and attorneys’ fees, with some states also providing for punitive damages.242 In contrast, other states only authorize state enforcement of their genetic-specific laws either through the attorney general’s office or through the appropriate state agency.243 Several of these state enforcement provisions impose civil or criminal fines or imprisonment for violations of the state’s genetic-specific laws.244 While state action can be an important mechanism for enforcing these laws and serve as a deterrent, they typically do not compensate individuals whose rights have been violated as civil or criminal fines are paid to the state, not the individual. In addition, where state enforcement is the only mechanism, aggrieved individuals may have no recourse against someone who has violated their rights if the state chooses not to act. Accordingly, a state law provision of a private right of action can be significant.