Abstract

Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study is the first federally funded study addressing aging among LGBTQ older adults throughout the United States. This article examines the evolution of this landmark study and explores the well-being of LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older (n = 200), the most underrepresented group in the field. Based on the Iridescent Life Course, we examined the diverse, intersectional nature of LGBTQ older adults’ lives, finding high levels of education and poverty. Microaggressions were negatively associated with quality-of-life and positively associated with poor physical and mental health; the inverse relationship was found with mastery. When the oldest encountered risks, it resulted in greater vulnerability. This longitudinal study is assessing trajectories in aging over time using qualitative, quantitative, and biological data and testing evidence-based culturally responsive interventions for LGBTQ older adults. Research with LGBTQ oldest adults is much needed before their stories are lost to time.

Keywords: LGBTQ, oldest old, resilient, well-being, health

Introduction

Age, sexuality, and gender intersect with cultural context as well as historical and generational influences. In the United States, the population of adults aged 65 years and older is projected to more than double from 46 million in 2016 to 98 million by 2060 (Mather, Jacobsen, & Pollard, 2015; U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). With the shifting demographics and the aging of the population in the United States, those 80 years and older are the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The older adult population in the United States is also becoming more diverse by race/ethnicity and sexuality and gender. Three percent of U.S. adults aged 50 years and older self-identity as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender on public health surveys, representing about three million adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). When also considering same-sex sexual behavior, romantic relationships and diverse, and nonbinary genders, the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adults aged 50 years and older doubles to more than 6% of the population. Given the fast growth of older adults, LGBTQ adults will account for more than 20 million older adults in the United States by 2060 (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017).

History of Federal Support for LGBTQ Aging Research: The Shifting Landscape

The field of LGBTQ aging had been relatively slow to develop in part because of the lack of available data and resources to pursue such research. Until recently in the United States, sexual orientation and gender identity and expression measures were rarely included in public health and aging studies, and when included, they were often only asked of younger adults, with age-based restrictions excluding older adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2015). Assumptions were often made that sexual orientation and gender identity and expression questions were too sensitive or controversial for older adults, and that these populations were too hard to reach, recruit, or retain in studies, all of which stymied progress in the field (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2015). Yet, our early studies found that older adults do respond to sexual orientation and gender expressions measures in aging and public health studies. In one public survey of adults, including those aged 65 years and older, a sexual identity question had a 98% response rate, which was more than 10% higher than the household income question (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2015). Based on such evidence, public health and aging surveys in the United States are increasingly including sexual and gender identity measures.

Concomitantly, public funding for LGBTQ aging research has been relatively scarce. In 1999, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Mental Health funded an early qualitative and quantitative research project that we developed to identify key risk and protective factors predicting the aging and well-being of sexual and gender diverse older adults living with HIV and their caregivers (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Muraco, & Mincer, 2009). Based on this preliminary work, in 2009, the U.S. NIH and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) funded Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS), the first large scale (R01) national study of LGBTQ older adults across all U.S. census divisions. This study gathered both self-administered quantitative survey data and objective data (including biomarkers and functional and cognitive assessments) as well as qualitative in-depth interview data of life events and experiences. See Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim, 2017 and Age-Pride.org for additional information.

In 2013, we received continuation funding from NIH/NIA for an additional 5 years to launch the longitudinal study, which has maintained a high retention rate of 96.5% over 5 years. Recently, we received funding for an additional 5 years (2019–2023) to continue the longitudinal study to assess trajectories in aging of LGBTQ midlife and older adults over time and to harmonize with other types of data, such as administrative health records. In addition, based in part on findings from the longitudinal study, we recently were funded by NIH/NIA to develop and test the first intervention addressing the needs of LGBTQ older adults living with memory loss and their caregivers (Aging with Pride: IDEA[Innovations in Dementia Empowerment and Action]; R01). Based on the mounting evidence of health disparities across all ages of LGBTQ populations, the U.S. NIH recently launched the Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office.

The Iridescent Life Course

To investigate the inequities and resilience of LGBTQ older adults, Aging with Pride: NHAS developed the Health Equity Promotion Model framework (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Simoni, et al., 2014) to examine the range of factors and social determinants (e.g., life course, environmental, structural, psychological, social, behavioral, and biological) accounting for variations in aging, well-being, and health over time across this population. While many studies have investigated how coping processes result in poor mental health for LGBTQ adults (Meyer, 2003), fewer studies have utilized life course perspectives to investigate the lives of LGBTQ people.

To more fully capture the possibilities of the growing field of aging in historically disadvantaged and marginalized populations, we use the Iridescent Life Course (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, & Muraco, 2019), much like iridescent properties encompassing the interplay of light and environment creating dynamic and fluid representations as perceived from different angles and perspectives over time. This perspective accounts both for the similarities in the life course across populations, such as historical times, social relationships, timing of lives, and agency (Elder, 1994), as well as considers those factors that are distinct to historically disadvantaged populations, such as LGBTQ older adults.

The Iridescent Life Course, for example, illuminates the intersectionality of demographic characteristics and the social construction and power dynamics within the interplay of history, cultural location and meaning, and structural location affecting LGBTQ older adults. Mirroring rapid shifts in public opinion, in 2015 the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges mandated the constitutional right to marry for same-sex couples. Yet in the United States there are no federal-level protections against discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodation by sexual orientation or gender identity and expression (Human Rights Campaign, 2019a), and fewer than half of the United States have state-level protections (Human Rights Campaign, 2019b).

In our earlier studies, Aging with Pride: NHAS investigated such inequities and documented significant health disparities such as higher rates of disability, poor general health, and mental distress as well as some adverse health behaviors (e.g., smoking and excessive drinking) among sexual minority older adults as compared with heterosexuals of similar age (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco, & Hoy-Ellis, 2013). Our recent research found significantly higher rates of 9 out of 12 chronic conditions and multimorbidity among sexual minority older adults compared with heterosexuals of similar age (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Shiu, & Bryan, 2017).

Despite such risks, Aging with Pride: NHAS has consistently found that most LGBTQ older adults are aging well and have good quality of life (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Shiu, Goldsen, & Emlet, 2015). A primary focus of the Aging with Pride: NHAS study has been to understand both the challenges as well as the resilience and resources of LGBTQ older adults and their families and communities. Several of our studies illustrated the vast diversity in aging within this population, including differences by gender identity and expression (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Cook-Daniels, et al., 2014), people of color (Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2012), women (Bryan, Kim, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017), bisexuals (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Shiu, Bryan, Goldsen, & Kim, 2017), and age cohorts (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015). Yet, in most public discourse and research, LGBTQ older adults remains largely invisible and underserved, especially those oldest in these communities.

The Iridescent Life Course illustrates the ways that the oldest experience unique challenges and strengths due to distinct historical and social contexts. The LGBTQ oldest adults in the United States came of age during periods when there was pervasive silence about sexual and gender identities, and same-sex sexual behavior was severely stigmatized and criminalized and gender roles were more strictly proscribed, prior to the civil rights, women’s and gay liberation movements.

Gerontological research has differentiated age and cohort effects, with early work (Johnson & Barer, 1979; Riley, 1984) and more contemporary research (Riley, 2001) distinguishing the oldest old (often defined as age 80 years and older (World Health Organization, 2001), from their younger counterparts. The oldest in the United States are characterized by a higher proportion of women, as well as lower education, higher levels of comorbidity and physical and cognitive limitations, and long-term widowhood (Smith et al., 2002). Studies on the well-being of the oldest in the general population have placed emphasis on their quality of life, given the general decline in physical functioning at advanced age (Ailshire & Crimmins, 2011).

The goal of this article is to better understand the experiences and needs of those aged 80 years and older, likely the most invisible and underresearched group globally in existing LGBTQ international aging research. In this article, we will investigate the following research questions: What are the demographic characteristics and historical, environmental, social, and behavioral factors predicting the quality of life and physical (physical impairment) and mental (depression) health of LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older? Is there an interaction effect by age on these study outcomes?

Methods

Aging with Pride: NHAS, as the first federally funded national longitudinal study of LGBTQ adults aged 50 years and older in the United States (N = 2,450), began collecting data in 2010 for the foundational cross-sectional study, and in 2014 for the longitudinal study, followed by subsequent biannual data collection. This study utilizes the 2014 data from participants aged 80 years and older (n = 200).

Individuals who self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, trans or gender nonbinary, or engaged in same-sex sexual behavior, had a romantic relationship with, or attraction to, someone of the same sex or gender were included in the study. The age range of 50 years and older for the initial study was used to assess aging, health, and well-being trajectories over time since pattern of health deterioration emerges earlier, especially within disadvantaged communities (House, Lantz, & Herd, 2005). The sampling goal of 2,450 for this study was determined in part based on power analyses and projected attrition rates by age cohort, gender, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, and geographic location, with an aim to reflect the heterogeneity of the LGBTQ population and minimize noncoverage bias.

Recruitment for the study occurred nationally through collaborations with 17 community-based agency contact lists, considering geographic concentration of LGBTQ populations (Gates, 2015) and racial and ethnic minorities (Kastanis & Gates, 2013a, 2013b). To increase coverage of the hidden within hidden segments of the population including the oldest, women, and racial or ethnic minority communities, we also employed social network clustering chain-referral utilizing reciprocal connections within communities (Walters, 2011). Through these methods, this study secured one of the most demographically diverse samples of LGBTQ older adults reported.

Study participants completed a self-administered survey, available in either English or Spanish, which took approximately 40 to 60 minutes. Fifty-five percent of the participants chose to complete mail-in surveys and 45% online. Each participant received a $20 incentive for their time. The final sample size of 2,450 for the longitudinal study included 1,092 participants aged 50 to 64 years (born 1950–1964), 1,158 participants aged 65 to 79 years (born 1935–1949), and 200 participants aged 80 years and older (born 1916–1934). In addition to the survey data, 300 in-person interviews were conducted across four metropolitan areas (with the most demographic diversity) and we collected in-depth information on life experiences; physical, functional, and cognitive assessments; and biological data through noninvasive dried blood spot collection. The study measures are summarized in Table 1. See Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim (2017) for a detailed description of the methods used in this study.

Table 1.

Description of Measures.

| Variables | Items or description |

|---|---|

| Study outcomes | |

| Quality of life | “How would you rate your quality of life” (1 = very poor to 5 = very good) from the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF; Bonomi, Patrick, Bushnell, & Martin, 2000; World Health Organization, 2004) |

| Physical impairment | Mean scores of eight items assessing physical functioning defined as difficulty with lower and upper extremity performance (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). items include walking a quarter of a mile or standing on your feet for about 2 hours or sitting for about 2 hours: 0 = no difficulty to 4 = extremely difficulty or cannot do; α =.90. |

| Depression | Summed scores of 10 items of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D 10; Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994): 0 = less than one day to 3 = five to seven days; Range = 0 – 30; α =.85 |

| Historical or environmental | |

| Lifetime discrimination and victimization | Summed scores of the frequencies of experiencing five types of discrimination (e.g., employment, housing, health care) and nine types of victimization (e.g., verbal and physical threat, verbal, physical, and sexual assault) during the lifetime as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity or expression (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). 0 = never to 3 = three or more times; Range = 0 to 42 |

| Microaggressions | Mean scores of eight items assessing frequency of experiences (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017) of brief and commonplace daily indignities, intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile and negative attitude or judgment (Sue et al., 2007), including “People say to you that they are tired of hearing about the homosexual or transgender agenda”: 0 = never to 5 = almost every day; α =.85 |

| Psychological | |

| Identity stigma | Mean scores of four items assessing negative attitudes and feelings toward their sexual or gender identity, including feeling ashamed of oneself for one’s sexual or gender identity: 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree; α =.83 |

| Identity disclosure | Self-report on their level of visibility with respect to their sexual or gender identity: 1 = never told anyone to 10 = told everyone |

| Mastery | Mean scores of a 4-item mastery scale (Lachman & Weaver, 1998), including “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me”: 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree; α =.84 |

| Social | |

| Social support | Mean scores of the abbreviated 4-item scale (Gjesfjeld, Greeno, & Kim, 2008) of MOS-Social Support Scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), assessing the frequencies that differing types of support were available to them (e.g., “Someone to help with daily chores if you were sick”): 0 = never to 4 = very often; α =.86 |

| Social isolation | Mean scores of three items from the UCLA Loneliness scale (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004), including “How often do you feel isolated from others?”: 0 = never to 4 = very often; α =.89 |

| Living alone | A single question asking whether participants currently lived alone: 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Behavioral | |

| Substance use | A combined measure of binge drinking (four or more drinks at any drinking occasion for the past 30 days; National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2004), current smoking (at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime and currently smoking; Jamal et al., 2015), or illicit drug use (whether they have used drugs other than those required for medical reasons during the past 12 months; Smith, Schmidt, Allensworth-Davies, & Saitz, 2010). Affirmative response to one or more of the three items was considered substance use. |

| Physical activity | Moderate or vigorous activities for more than 150 minutes in total per week, as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015): 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Background characteristics | Age (years; M = 83.85, S.D. = 3.61), sexual identity (gay or lesbian vs. other), gender identity (transgender or gender diverse or non-binary vs. cisgender), gender (women vs. men vs. other), race or ethnicity (non-Hispanic Whites vs. people of color), income (living at or below 200% of federal poverty level (FPL) vs. >200% FPL), education (high school or less vs. some college or college graduate vs. graduate or professional degree), employment (Employed full- or part-time vs. not currently employed) |

To analyze the data, we utilized Stata/SE 14.2, and we applied survey weights to reduce bias from nonprobability sampling, derived from a two-step postsurvey adjustment approach utilizing external probability sample data as benchmarks (Lee & Valliant, 2009). In terms of analyses, we conducted descriptive statistics by estimating percentage distributions and means for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, and their 95% confidence intervals. We did not report estimates when a numerator was 12 or less (Van Belle, 2002), or when a relative standard error (i.e., the ratio of the standard error of an estimate to that estimate) exceeded 0.3, the common criterion of nonreporting unreliable estimates in major data reporting systems. Next, to examine predictors of the study outcomes, we performed ordinary least squares regression analyses. Linear predictions of the study outcomes were made by entering the historical and environmental, psychological, social, and behavioral factors, controlling for background characteristics (age, gender, race or ethnicity, education, and income). In addition, we tested moderating effects of age for significant predictors of study outcomes in order to understand whether the significant effects apply to all ages of 80 years and older. We entered interaction terms (age X a significant predictor) in the corresponding ordinary least squares regression analysis. Significant interactions were further probed by examining the differing relationships according to age using three age parameters: (a) the youngest age in the sample (age 80 years), the mean age (age 84 years), and 1 standard deviation ( = 6.47) above the mean age (age 90 years).

Findings

Table 2 illustrates the demographic characteristics of the LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older. About 70% identified as lesbian or gay , and 31.4% as other diverse sexual identities. About 66.5% were men. Eleven participants aged 80 years and older identified as transgender or gender diverse or nonbinary. Fifteen percent (15.3%) of the LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older were people of color. Nearly 28.7% had some college education or college degree, and an additional 44.3% earned graduate or professional degree. About 39.8% were living at or below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). More than 7% (7.24%) of those aged 80 years and older were working.

Table 2.

Background Characteristics of LGBTQ Adults Aged 80 Years and Older, Unweighted (n = 200).

| Unweighted n | %a | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual identity | |||

| Gay or Lesbian | 175 | 68.61 | [54.08, 80.23] |

| Other | 25 | 31.39 | [19.77, 45.92] |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 48 | 29.11 | [18.66, 42.37] |

| Men | 146 | 66.53 | [53.45, 77.49] |

| Gender identity | |||

| Trans or diverse or nonbinaryb | 11 | – | – |

| Cisgender | 189 | 86.68 | [69.46, 94.90] |

| Race or ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 175 | 84.75 | [68.70, 93.36] |

| People of color | 23 | 15.25 | [6.64, 31.30] |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 20 | 27.01 | [16.89, 40.25] |

| Some college or college degree | 84 | 28.67 | [21.50, 37.09] |

| Graduate or professional degree | 94 | 44.32 | [33.47, 55.75] |

| Income | |||

| ≤200% FPL | 76 | 39.77 | [29.27, 51.31] |

| >200% FPL | 123 | 60.23 | [48.69, 70.73] |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 19 | 7.24 | [4.30, 11.93] |

| Not employed | 178 | 92.76 | [88.07, 95.70] |

Note. FPL = federal poverty level; CI = confidence interval.

Survey weights were applied.

The estimate of transgender, gender diverse, or nonbinary is not reported in the table due to a high relative standard error (46.47%) and a small numerator size (n = 11).

Table 3 presents the distributions of the study outcomes and predictor variables. The mean frequency of experiencing lifetime discrimination and victimization was 3.47 incidents. The most common types of lifetime discrimination and victimization experienced by LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older, included being verbally insulted (39.9%), being threatened with physical violence (29.6%), and being threatened that someone would disclose their sexual or gender identity (23.1%). The mean degree of microaggressions was 0.87. Nearly 80% reported they had experienced at least one microaggression, two or more times in the past year. The most common microaggressions experienced were exposure to people referring to sexual orientation or gender identity as a “lifestyle choice” (49.2%), media portraying LGBT stereotypes (47.7%), people using derogatory terms to refer to LGBT people in one’s presence (24.3%), discussion of the homosexual or transgender agenda (23.6%), and people claiming they understood the participants since they had a LGBTQ friend (24.3%).

Table 3.

Distributions in Historical and Environmental, Psychological, Social, Behavioral, and Outcome Variables Among LGBTQ Adults Aged 80 Years and Older, Unweighted (n = 200).

| Mean or % | 95% CIs | |

|---|---|---|

| Historical and environmental | ||

| Lifetime discrimination and victimization, M (range: 0–42) | 3.47 | [2.69, 4.25] |

| Microaggressions, M (range: 0 – 5) | 0.87 | [0.71, 1.02] |

| Psychological | ||

| Identity stigma, M (range: 1–6) | 1.88 | [1.56, 2.19] |

| Identity disclosure, M (range: 1–10) | 6.83 | [6.09, 7.57] |

| Mastery, M (range: 1–6) | 4.23 | [4.02, 4.44] |

| Social | ||

| Social support, M (range: 0–4) | 2.71 | [2.46, 2.95] |

| Social isolation, M (range: 0–4) | 1.27 | [1.05, 1.49] |

| Living alone, % | 54.75 | [43.18, 65.82] |

| Behavioral | ||

| Substance use, % | 18.79 | [12.38, 27.48] |

| Physical activity, % | 79.68 | [70.59, 86.50] |

| Outcomes | ||

| Quality of life, M (range: 1–5) | 4.15 | [3.98, 4.32] |

| Physical impairment, M (range: 0–4) | 1.30 | [1.09, 1.51] |

| Depression, M (range: 0–30) | 6.48 | [5.31, 7.65] |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Survey weights were applied.

The mean score of identity stigma was relatively low at 1.88, with a moderate identity disclosure score (M = 6.83). The participants on average had high to moderate levels of mastery (M = 4.23). The mean level of social support availability was higher than moderate (M = 2.71). At least 50% reported the availability of some type of support, if needed. The mean level of social isolation was 1.27; nearly half experienced lack of companionship (47.5%); felt left out (46.1%) or isolated from others (35.9%). The majority (54.8%) were living alone. Nearly one in five (18.8%) reported substance use (smoking, excessive drinking, or drug use for nonmedical reasons). Nearly 8 out of 10 (79.7%) were involved in moderate or vigorous activities as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The level of quality of life was relatively good (M = 4.15, 95% CI: [3.98, 4.32]). The mean physical impairment score (1.30) indicated mild to moderate difficulties in physical functioning. The depression score among the participants aged 80 years and older was 6.48, with about 21.6% having a score of 10 or higher indicating a significant likelihood of clinical depression (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994).

Table 4 presents the significant predictors of the study outcomes. Higher quality of life was positively associated with mastery, and significantly negatively associated with microaggressions, social isolation, and living at or below 200% FPL. Physical impairment was significantly associated with more microaggressions, higher identity stigma, older age, being a women, and living at or below 200% of FPL; mastery was negatively associated with physical impairment. Depression was significantly positively associated with microaggressions and higher levels of social isolation. In contrast, higher levels of mastery and physical activity were associated with lower rates of depression. One year increase in age led to 0.18 point increase in depression, and non-Hispanic Whites were more depressed by 2.12 points than people of color.

Table 4.

Risk and Promoting Factors Predicting Health Outcomes Among LGBTQ Adults Aged 80 Years and Older, Unweighted (n = 200).

| Quality of life |

Physical impairment |

Depression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CIs | B | 95% CIs | B | 95% CIs | |

| Historical and environmental | ||||||

| Lifetime discrimination and victimization | 0.00 | [−0.02, 0.02] | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.05 | [−0.17, 0.74] |

| Microaggressions | −0.16* | [−0.29, −0.04] | 0.39* | [0.07, 0.70] | 1.09* | [0.02, 2.16] |

| Psychological | ||||||

| Identity stigma | −0.03 | [−0.15, 0.09] | 0.25* | [0.06, 0.45] | 0.46 | [−0.19, 1.12] |

| Identity disclosure | −0.00 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.04 | [−0.00, 0.09] | 0.14 | [−0.16, 0.44] |

| Mastery | 0.26*** | [0.12, 0.39] | −0.16* | [−0.28, −0.03] | −1.30** | [−2.08, −0.53] |

| Social | ||||||

| Live alone | 0.08 | [−0.12, 0.28] | 0.18 | [−0.06, 0.42] | 0.28 | [−1.22, 1.78] |

| Loneliness | −0.24*** | [−0.35, −0.14] | 0.03 | [−0.11, 0.17] | 1.39*** | [0.66, 2.13] |

| Social support | 0.03 | [−0.09, 0.15] | 0.09 | [−0.09, 0.25] | −0.38 | [−1.22, 0.47] |

| Behavioral | ||||||

| Substance use | 0.05 | [−0.15, 0.25] | −0.06 | [−0.39, 0.27] | −0.11 | [−1.42, 1.39] |

| Physical activity | 0.20 | [−0.04, 0.45] | −0.20 | [−0.52, 0.12] | −1.96* | [−3.45, −0.47] |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] | 0.05** | [0.02, 0.08] | 0.18* | [0.01, 0.35] |

| Women | 0.18 | [−0.05, 0.42] | 0.57** | [0.18, 0.95] | 0.62 | [−0.63, 1.86] |

| People of color | 0.05 | [−0.19, 0.29] | 0.23 | [−0.15, 0.60] | −2.12** | [−3.43, −0.80] |

| Education (ref: Graduate or professional degree) | ||||||

| Some college | −0.12 | [−0.35, 0.11] | 0.18 | [−0.08, 0.44] | 0.95 | [−0.27. 2.16] |

| High school or less | −0.01 | [−0.30, 0.28] | 0.06 | [−0.34, 0.45] | 0.18 | [−1.52, 1.89] |

| Income, ≤200% FPL | −0.26* | [−0.47, −0.06] | 0.34** | [0.13, 0.55] | 0.70 | [−0.64, 2.05] |

Note. CI = confidence interval; FPL = federal poverty level.

Survey weights were applied. Adjusted for age, gender, race or ethnicity, education, and income.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

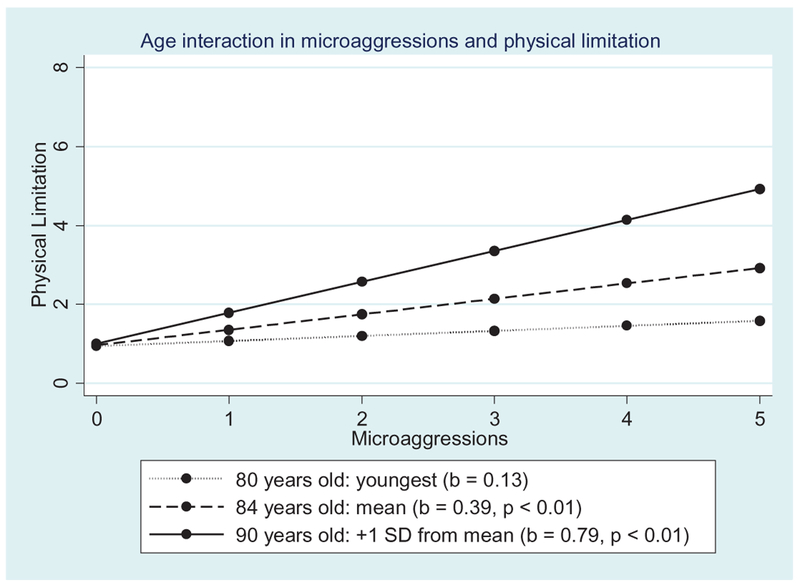

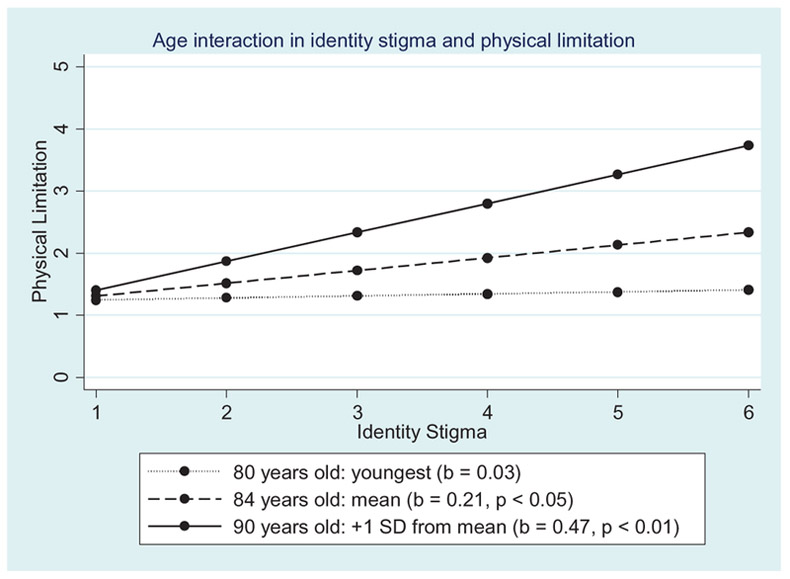

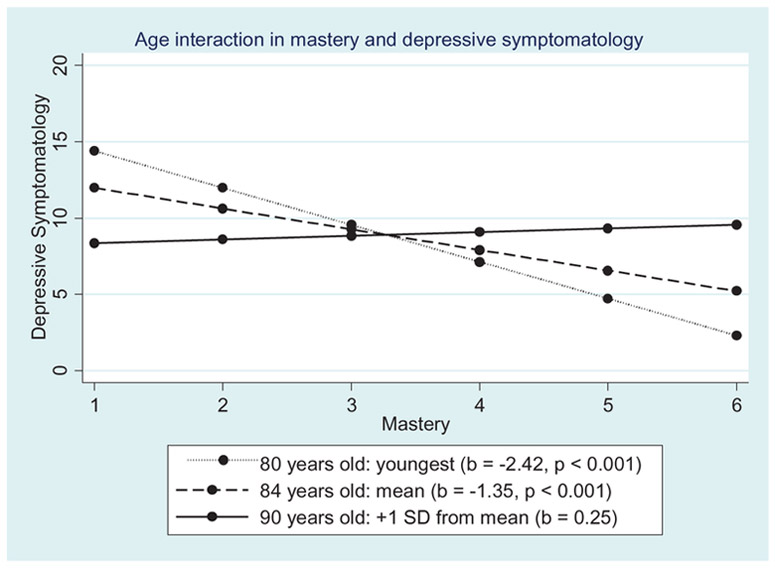

Interaction analyses indicated that the negative effects of microaggressions and identity stigma on physical impairment were moderated by age, such that the negative effect of microaggressions and identity stigma exacerbated physical impairment as age increased beyond the mean. Figure 1 illustrates the differing patterns across three age groups of older adults aged 80 years and older. There was no association between microaggressions and physical impairment for those aged 80 years, the youngest in this study, but microaggressions were linked with more physical impairment at age 84 years, the mean age of the study population, and age 90 years, 1 standard deviation above the mean. The moderating effect of age in the relationship between identity stigma and physical impairment was the same as the relationship between microaggressions and physical impairment. Figure 2 shows no association between identity stigma and physical impairment at age 80 years, but identity stigma was associated with physical impairment at age 84 years and at age 90 years. The relationship between mastery and depression was also moderated by age in that the protective effect of mastery on depression decreases as age increases. As shown in Figure 3, depression decreased as mastery increased among those aged 80 years and those aged 84 years, but depression was not associated with mastery for those aged 90 years. There were no significant interactions with age among the predictors of quality of life.

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of age on the association between microaggressions and physical impairment.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of age on the association between identity stigma and physical impairment.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of age on the association between mastery and depression.

Discussion

LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older are the surviving pioneers in this population, yet there is an alarming dearth of research on their life experiences and quality of life. Aging with Pride: NHAS was designed to be inclusive of such hard-to-reach populations, with specific sampling goals stratified by key demographics, including age cohort (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). This study is the first to comprehensively examine a national sample of LGBTQ oldest adults and to assess their quality of life and physical and mental health.

Given the important intersecting demographic factors influencing the lives of LGBTQ older adults, the Iridescent Life Course poses important questions regarding the utility and potential overuse of “LGBTQ” as an umbrella term, given the intersectional nature of the diverse communities in this population. We observed, for example, unique intersectional demographic differences consistent with the Iridescent Life Course among LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older. Compared with those of similar age in the general population, we found that the LGBTQ oldest adults were more than twice as likely to have a college or advanced degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016) and nearly twice as likely to be working (Van Dam, 2018). High levels of educational attainment among LGBTQ older adults have been found in previous studies (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). More than 70% have attained more than a high school education, yet about 40% were living at or below 200% FPL. Thus education may not be as protective for LGBTQ older adults in achieving economic security as other older adult populations.

Consistent with a previous study (Robert et al., 2009), poverty rather than education was found to be more strongly associated with quality of life as well as physical impairment in this study. Most LGBTQ older adults in the U.S. report experiencing disadvantages and discrimination in work environments (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Bryan, et al., 2017), which foster long-term economic inequities and may result in an elevated need for full-time employment among the oldest LGBTQ adults. Some LGBTQ elders may choose to remain working to stay engaged in their communities. Such demographic differences deserve more research to understand the motivations as well as the potential constricting opportunities experienced by the oldest adults in this population.

Interestingly, we found that the majority of the LGBTQ older adults aged 80 years and older participating in the study were men, whereas the population of women is much larger in the general population (Werner, 2011). While many LGBTQ aging studies have primarily men in their samples, this is not the case with the full Aging with Pride: NHAS study since we stratified the sample by gender, resulting in a relatively equal proportion of women. Further research is needed to examine if gender differences in life expectancy or premature mortality differ by sexual orientation. Studies have found that disability at all ages is a key risk factor for sexual minority women compared with heterosexual women (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). As the results of the regression analyses in study found, being a woman and older age were associated with higher physical impairment, which are well-known predictors of mortality (Hirvensalo, Rantanen, & Heikkinen, 2000; Inouye et al., 1998). Or it may be that lesbian and bisexual women aged 80 years and older were especially hidden and we were unable to secure them in the stratified sample.

Studies on the well-being of the oldest in the general population have placed emphasis on their quality of life, given the general decline in physical functioning at advanced age (Brett et al., 2012; Femia et al., 2001). A nationally representative study in the United States found that among the oldest, life satisfaction did not decline as age advanced older than 80 years as opposed to physical impairment (Ailshire & Crimmins, 2011), indicating that life satisfaction is an important factor associated with longevity (Smith et al., 2002; Yi & Vaupel, 2002). Despite profound histories of marginalization given the historical context of their lives, the oldest LGBTQ adults in this study displayed resilience and, like older adults in general, reported relatively high quality of the life. On average, LGBTQ adults 80 years and older are survivors, reporting higher than moderate levels of mastery. Furthermore, mastery, as a potentially modifiable factor, predicted higher quality of life and lower scores of depression and physical impairment.

Illuminating the Iridescent Life Course reflects the power dynamics and social constructions inherent in the representation and lived lives of marginalized LGBTQ oldest adults; this study found that about 80% of the oldest LGBTQ adults had experienced on-going microaggressions, which significantly predicted lower quality of life, and more physical impairment and depression. Experiences of marginalization have been documented as significant risk factors of mental and physical health among LGBTQ older adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Bryan, Shiu, & Emlet, 2017). Yet, the findings in this study suggest for the oldest LGBTQ adults, the insidious, on-going and traumatic nature of microaggressions is a stronger predictor of quality of life and health than lifetime experiences of discrimination and victimization. Microaggressions, such as LGBTQ stereotyping in mass media and microinvalidation and insult (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017; Woodford, Chonody, Kulick, Brennan, & Renn, 2015), may be unavoidable, despite the concealment of one’s identity.

Preventing microaggressions requires attention to the structural and cultural context as identified in the Iridescent Life Course, which requires upstream and system-level interventions necessary to thwart the biases and disrespectful public discourse that LGBTQ older adults encounter. For example, despite the fact that many LGBTQ older adults report experiences of marginalization, few aging and health services have programs and policies inclusive of LGBTQ older adults and LGBTQ older adults themselves often report experiencing biases rather than welcoming environments in the health and aging services (Brotman, Ryan, & Cormier, 2003; Porter & Krinsky, 2013).

The results of the interaction effects by age illustrate the vulnerability of the oldest among those aged 80 years and older. The robust effect of microaggressions predicting the study outcomes was exacerbated as age increased. With increased age and concomitant fragility, the ongoing confrontation of bias through microaggressions may place undue stress, increasing a sense of vulnerability and lack of safety for LGBTQ oldest adults. This pattern was also evident in the interaction of age with identity stigma and physical impairment. Although mastery was an important protective factor associated with quality of life and the other outcomes, the positive effect of mastery in relation to mental health decreased as age increased. Perhaps in very late life, the increasing sense of vulnerability among LGBTQ older adults reduces the shielding nature of mastery and other such factors related to resilience that might have served a protective function in earlier life.

Given the historical oppressive times in which the oldest LGBTQ adults came of age, they reported relatively moderate levels of discrimination and victimization, and about one quarter had been threatened to be “outed” with their identities disclosed against their will, increasing their vulnerability in the hostile environments. During these historical times, LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older were resourceful and adaptively found ways to protect themselves, often concealing their identities, as they lived their lives. While the oldest LGBTQ adults likely maintained their anonymity and hid their sexuality or gender identities to protect them from vulnerability, higher identity stigma, independently predicted adverse outcomes in the study.

While older adults in general, particularly the oldest population, are more likely to live alone (Mather et al., 2015), LGBTQ older adults may be at a greater risk of living alone, loneliness, and social isolation (Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016). And, many do not have access to a safety net to assist them if a major illness or disability occurs. This is a critical concern since population-based studies have found higher rates of disparities in multiple chronic conditions among LGBTQ older adults compared with the older adult population at large (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). The findings in this article suggest that social isolation rather than living alone or availability of social support is a stronger predictor of lower quality of life and depression for this age-group. Furthermore, identity stigma seems to have come with a high cost—for example, leaving them at greater risk of social isolation, especially in old age, when they are at risk of losing their age-based support system and may need to rely on others. LGBTQ older adults have rated social events and support groups as the most needed services as they age (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011), which should be considered for intervention development aimed at reducing social isolation and stigma among at-risk LGBTQ oldest adults.

Nearly one fifth of the LGBTQ oldest adults were engaged in substance use (e.g., smoking, excessive drinking, or drug use for nonmedical reasons), which is a well-known risk factor for LGBTQ people, as well as mental and physical health problems and poor quality of life among older adults in general (Adrian & Barry, 2003). Whereas previous studies (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015) suggest the negative impact of substance use on health-related quality of life in later life, this study found that substance use was not associated with quality of life or health outcomes among the oldest LGBTQ adults. Further research is warranted to examine if substance use created premature mortality (Darke, Degenhardt, & Mattick, 2006; Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004) for some LGBTQ older adults that are not in this study.

The oldest, as survivors, may be the most physically and mentally resilient among the LGBTQ older adults. Likely one of the most important health-promoting factors evidenced among the LGBTQ oldest adults in this study, like others in the general population (Stessman, Hammerman-Rozenberg, Cohen, Ein-Mor, & Jacobs, 2009), was the high level of physical activity. Nearly 80% of the oldest LGBTQ adults were engaged in regular physical activities, which are notably higher than the general population (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). Increasing access to interventions that promote physical activities in these underserved populations may be especially helpful in reducing psychological distress and depression.

Next Steps

The worldwide burgeoning of the older adult population allows us to explore the variations and shared experiences in aging over the life course across differing cultures. The Iridescent Life Course highlights the rapidly changing social context and raises important generational issues for future study. Yet, to date, most research has ignored heterogeneity within LGBTQ communities. Exploring variations and similarities across the life course within intersecting multiple social and structural positions are posed to foster a deeper understanding of life course trajectories among LGBTQ people, including the oldest. Additional investigation of the consequences of divergent representations across differing contexts and societies and the interaction with individual, interpersonal, social, and structural opportunities and barriers are much needed.

While the findings in this study highlight the distinct needs and potential vulnerabilities of those 80 years and older, they also illustrate that most are aging well with relatively high quality of life. Additional work is needed to continue to reach those at greatest risk as well as to understand the strengths and mechanisms that are associated with well-being in later life. During the next phase of Aging with Pride: NHAS, we are utilizing a longitudinal design to understand trajectories in the lives of LGBTQ older adults over time and to investigate the similarities and differences among subpopulations in these communities. Analyzing key predictors of health and well-being, identified in our cross-sectional work (such as lifetime victimization and discrimination, macroaggressions, identity management, social relations, health behaviors, stress, and intersecting demographic characteristics), provides an important opportunity to examine both between- and within-individual changes in aging, well-being, and health over time.

By directly extending our cross-sectional research, our goal is to identify temporal relationships and explanatory mechanisms that predict variability in quality of life and aging over time. We are also supplementing the survey data with biological and administrative health data as well as functional and cognitive assessments to more fully assess the interrelationships between risk and protective factors as well as the influence of cohort, generational shifts, and demographic differences (e.g., gender and race/ethnicity) on changes in well-being over time. Through analysis of in-depth qualitative data, we will also more fully investigate the Iridescent Life Course of LGBTQ older adults across time.

Although cross-sectional data cannot adequately distinguish cohort and age effects, it is imperative to bring greater attention to the heterogeneity within LGBTQ aging and to examine the distinct experiences of the surviving oldest group, those aged 80 years and older. A longitudinal study will be particularly beneficial to adjust for survival bias when examining the aging, well-being, and health of the oldest LGBTQ adults. Furthermore, birth cohort effect and age effect can be distinguished when longitudinal data are accumulated over time. Although the influence of cohort heterogeneity in social and economic environments on well-being, health, and mortality in later life have been investigated in the general population (Lynch, 2003; Willson, Shuey, & Elder, 2007; Yang, 2007; Yang & Lee, 2009), such effects on the LGBTQ population have not yet been considered. Because characteristics by cohort can be confounded with real-time age changes, the longitudinal study will allow us to investigate how cohort effect and age effect differentially influence changes in well-being, health, and longevity.

A primary goal of this research since its onset is to use the information gained to generate innovative solutions by developing and testing evidence-based interventions and programs, as well as to promote prevention of adverse outcomes among LGBTQ older adults. While to date, we know that LGBTQ older adults are a health disparate population, it is critical to continue to secure the information needed on how best to reduce inequities in resilient yet at-risk population. Identifying the temporal and causal order of modifiable mechanisms is necessary as a first step to design tailored interventions to improve quality of life and health of LGBTQ older adults.

Efforts designed to gather the experiences and histories of the LGBTQ oldest adults are needed so stories of their lives and experiences are not lost to future generations. As we move forward in LGBTQ aging research, it is critical that we shed light on the oldest, who are the surviving pioneers in this population, balancing and attending to both positive and negative factors influencing their aging, well-being, and health. Such work will require attention to both resilience and risk in these communities. Efforts to address their needs will be best supported through fostering on-going partnerships between research, aging and health services, and the families and communities within which LGBTQ older adults age and live.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG026526 (K. I. Fredriksen Goldsen, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Karen Fredriksen Goldsen, PhD, is a professor and Director of Healthy Generations at the University of Washington. Dr. Goldsen is a nationally and internationally recognized scholar addressing equity and the intersections of aging, health, and well-being in resilient, at-risk communities. She is Principal Investigator of Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NIH/NIA, R01), the first national longitudinal study of LGBTQ midlife and older adult health assessing trajectories; Aging with Pride: IDEA (Innovations in Dementia Empowerment and Action) (NIH/NIA, R01) the first federally-funded study of cognitive impairment in LGBTQ communities; Socially Isolated Older Adults Living with Dementia (P30); Sexual and Gender Minority Health Disparities; and Investigator of Rainbow Ageing: The 1st National Survey of the Health and Well-Being of LGBTI Older Australians. Dr. Goldsen is the author of more than 100 publications, three books, and numerous invitational presentations including U.S. White House conferences and Congressional Briefings. Her research has been cited by the New York Times, U.S. News & World Report, NBC News, Washington Post, and more than 50 international news outlets.

Hyun-Jun Kim, PhD, is a Research Scientist at the School of Social Work, University of Washington, serving as Project Director and co-investigator of Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) and Aging with Pride: Innovations in Dementia Empowerment and Action (IDEA). His research interests include health disparities in historically disadvantaged older adult communities and the role of human agency and social relationships in the interplay of well-being, health-related quality of life, physical, mental, and cognitive health, multiple identities (particularly sexual orientation and race and ethnicity), and cultural resources. He is a Fellow of the Gerontological Society of America and has been recognized for his contributions advancing aging and health research.

Hyunzee Jung, PhD, is a Research Scientist with Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). Her research interests center on adversities facing stigmatized populations and resilience among sexual and gender minorities and other socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Her primary method of analysis is longitudinal quantitative analyses, including trajectories over life course.

Jayn Goldsen is the Research Project Manager for Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) at the University of Washington School of Social Work. She has over 30 years of experience in successful Center leadership and project management and has published in leading peer-reviewed journals. The focus of her scholarship includes personal relationships and well-being among LGBT older adults.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

References

- Ailshire JA & Crimmins EM (2011). Psycholotical factors associated with longevity in the United States: age differences between the old and oldest-old in the health and retirement study. Journal of Aging Research, 2011. Article ID 530534. doi: 10.4061/2011/530534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian M, & Barry SJ (2003). Physical and mental health problems associated with the use of alcohol and drugs. Substance Use Misuse, 38(11–13), 1575–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, & Martin M (2000). Validation of the United States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00123-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, & Cormier R (2003). The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 192–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett CE, Gow AJ, Corley J, Pattie A, Starr JM, & Deary IJ (2012). Psychosocial factors and health ad determinants of quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Quality of Life Research, 21(3), 505–516. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9951-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AEB, Kim H-J, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Factors associated with high-risk alcohol consumption among LGB older adults: The roles of gender, social support, perceived stress, discrimination, and stigma. The Gerontologist 57(S1), S95–S104. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Physical activity: How much physical activity do older adults need? Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/older_adults/

- Darke S, Degenhardt L, & Mattick R (2006). Mortality amongst illicit drug users In Mortality amongst illicit drug users: Epidemiology, causes and intervention (pp. 20–41). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511543692.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr., (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspective on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Femia EE, Zarit SH, & Johansson B (2001). The disablement process is very late life: A study of the oldest -old in Sweden. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 56(1), P12–P23. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.1.P12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Bryan AE, Jen S, Goldsen J, Kim HJ, & Muraco A (2017). The unfolding of LGBT lives: Key events associated with health and well-being in later life. The Gerontologist, 57(suppl 1), S15–S29. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim H-J, Erosheva EA, Emlet CA, Hoy-Ellis CP, … Muraco A (2014). Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: An at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist, 54(3), 488–500. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, & Muraco A (2019). Iridescent Life Course: Review of LGBTQ aging research and blueprint for the future. Gerontology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1159/000493559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Kim H-J (2015). Count me in: Response to sexual orientation measures among older adults. Research on Aging, 37(5), 464–480. doi: 10.1177/0164027514542109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Kim H-J (2017). The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults—An introduction to Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, Sexuality and Gender Study. The Gerontologist, 57(S1), S1–S14. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, Muraco A, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Bryan AE, Shiu C, & Emlet CA (2017). The cascading effects of marginalization and pathways of resilience in attaining good health among LGBT older adults. Gerontologist, 57(suppl 1), S72–S83. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Emlet CA, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Hoy-Ellis CP, … Petry H (2011). The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Muraco A, & Mincer S (2009). Chronically ill midlife and older lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals and their informal caregivers: The impact of the social context. Journal of Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 6(4), 52–64. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2009.6.4.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Shiu C, & Bryan AE (2017). Chronic health conditions and key health indicators among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older US adults, 2013-2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8),1332–1338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Shiu C, Goldsen J, & Emlet CA (2015). Successful aging among LGBT older adults—Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. The Gerontologist, 55(1), 154–168. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Shiu C, Bryan AEB, Goldsen J, & Kim H-J (2017). Health equity and aging of bisexual older adults: Pathways of risk and resilience. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 72(3), 468–478. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim H-J, Lehavot K, Walters KL, Yang J, … Muraco A (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. doi: 10.1037/ort0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ (2015). Comparing LGBT rankings by metro area: 1990 to 2014. Los Angeles, CA: Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Comparing-LGBT-Rankings-by-Metro-Area-1990-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gjesfjeld C, Greeno C, & Kim K (2008). A confirmatory factor analysis of an abbreviated social support instrument: The MOS-SSS. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(3), 231–237. doi: 10.1177/1049731507309830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, & Heikkinen E (2000). Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(5), 493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Lantz PM, & Herd P (2005). Continuity and change in the social stratification of aging and health over the life course: Evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal study from 1986 to 200/2002 (Americans’ Changing Lives Study). Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Waite L, Hawkley L, & Cacioppo J (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys—Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574∣ 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. (2019a). Federal legislation. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/resources/federal-legislation

- Human Rights Campaign. (2019b). State maps of laws & policies. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/state-maps

- Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, & Concato J (1998). Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA, 279(15), 1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, Babb SD, Caraballo RS, Singh T, … King BA (2015). Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005-2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(44), 1233–1240. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C & Barer B (1979). Life beyond 85 years – The aura of survivorship. Springer Publishing Company, New York, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kastanis A, & Gates GJ (2013a). LGBT African-American individuals and African-American same-sex couples. Los Angeles, CA: Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/lgbt-african-american-oct-2013/ [Google Scholar]

- Kastanis A, & Gates GJ (2013b). LGBT Latino/a individuals and Latino/a same-sex couples. Los Angeles, CA: Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/lgbt-latino-oct-2013/ [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-J, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2012). Hispanic lesbians and bisexual women at heightened risk for [corrected] health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1), e9–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-J, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2016). Living arrangement and loneliness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 548–558. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, & Weaver SL (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 763–773. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, & Valliant R (2009). Estimation for volunteer panel web surveys using propensity score adjustment and calibration adjustment. Sociological Methods & Research, 37(3), 319–343. doi: 10.1177/0049124108329643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM (2003). Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: A hierarchical approach. Demography, 40(2), 309–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Jacobsen LA, & Pollard KM (2015). Aging in the United States. Population Bulletin, 70(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, & Gerberding JL (2004). Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA, 291(10), 1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2004). NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter, 3, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Porter KE, & Krinsky L (2013). Do LGBT aging trainings effectuate positive change in mainstream elder service providers? Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 197–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley MW Men, women, and the lengthening life course In Rossi Alice S., (ed.) Gender and the lifecourse, New York: Aldine Publishing Co., 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Riley J (2001). Rising life expectancy: A global history. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA, Cherepanov D, Palta M, Dunham NC, Feeny D, & Fryback DG (2009). Socioeconomic status and age variations in health-related quality of life: Results from the National Health Measurement Study. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(3), 378–389. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, & Stewart AL (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Borchelt M, Maler H & Jopp D (2002). Health and well-being in the young old and oldest old. Journal of Social Issues, 58(4), 715–732. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, & Saitz R (2010). A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(13), 1155–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stessman J, Hammerman-Rozenberg R, Cohen A, Ein-Mor E, & Jacobs JM (2009). Physical activity, function, and longevity among the very old. Archives of Internal Medicine, 16, 1476–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). Census/library/publication demographics. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). 2017 National population projections tables. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

- Van Belle G (2002). Statistical rules of thumb. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam A (2018). A record number of folks age 85 and older are working. Here’s what they’re doing. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/07/05/a-record-number-of-folks-age-85-and-older-are-working-heres-what-theyre-doing/?utm_term=.2dced36822e9

- Walters KL (2011). Predicting CBPR success: Lessons learned from the HONOR Project. Hilton Head, SC: American Academy of Health Behavior [Google Scholar]

- Werner C (2011). The older population: 2010, census briefs (Report C2010BR-09). U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Willson A, Shuey K, & Elder G (2007). Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1886–1924. doi: 10.1086/512712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford MR, Chonody JM, Kulick A, Brennan DJ, & Renn K (2015). The LGBQ microaggressions on campus scale: A scale development and validation study. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(12), 1660–1687. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1078205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2001). Men ageing and health: Achieving health across the life span. 01WHO/NMH/NPH 01.2. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66941/WHO_NMH_NPH_01.2.pdf;jsessionid=84178523A863DCA5F71DFD7C5C3F09C4?sequence=1

- World Health Organization. (2004). The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)—BREF. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/en/english_whoqol.pdf

- Yang Y (2007). Is old age depressing? Growth trajectories and cohort variations in late-life depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(1), 16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, & Lee L (2009). Sex and race disparities in health: Cohort variations in life course patterns. Social Forces, 87(4), 2093–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z & Vaupel JW (2002). Functional capacity and self-evaluation of health and life of oldest old in China. Journal of Social Issues, 58(4), 733–748. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]