Abstract

Background:

LGBTQ older adults are a demographically diverse and growing population. In an earlier 25-year review of the literature on sexual orientation and aging we identified four waves of research that addressed dispelling negative stereotypes, psychosocial adjustment to aging, identity development, and social and community-based support in the lives of LGBTQ older adults.

Objectives:

The current review was designed to develop an evidence base for the field of LGBTQ aging, as well as to assess the strengths and limitation of the existing research and to articulate a blueprint for future research.

Methods:

Using a life course framework, we applied a systematic narrative analysis of existing research on LGBTQ aging. The review included 66 empirical peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2009 and 2015 focusing on LGBTQ adults age 50 and older as well as those including age-based comparisons of those 50 and older and younger counterparts.

Results:

Since the prior review, the field has grown rapidly as evident by the number of articles reviewed. Several findings were salient, including the increased application of theory (with critical theories most often used), and more varied research designs and methods. A new wave of research on the health and well-being of LGBTQ older adults was identified. Yet, there were few studies addressing the oldest in the community, bisexuals, non-binary older adults, older adults of color, and those living in poverty.

Conclusions:

Highlighting the interplay of rainbow like colors, Iridescent Life Course highlights queering and transforming the life course, encompassing intersectionality and fluidity over time. Such an approach emphasizes the differing configurations of risks and resources, legacies of historical trauma, and inequities and opportunities in representation and capital. More depth rather than breadth, as well as multi-level and longitudinal studies and global initiatives are imperative.

Keywords: LGBTQ, Aging, Review, Life course, Queering, Trans-forming

Introduction

Mirroring rapid changes in state and federal policies related to same-sex marriage, there has been a significant increase in public attention to LGBTQ issues. Between 2001 and 2016, public support in the U.S. for same-sex marriage grew steadily from 35% to 55% [1], culminating in the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court decision mandating the constitutional right to marry for same-sex couples in the U.S. Despite increasingly positive societal discourse regarding LGBTQ people, those in older adulthood remain largely invisible. The Institute of Medicine [2] identified LGBTQ older adults as an underserved and understudied population, calling for more research to address their distinct needs.

The proportion of older adults continues to grow faster than any other segment of the population worldwide, and the U.S. is no exception, with the 65-and-older population expected to more than double in size from 40.2 to 88.5 million between 2010 and 2050 [3]. The older adult population is also increasingly diverse by race and ethnicity [4], as well as by sexual and gender identities [5]. Individuals who openly self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, and/or queer (LGBTQ) are estimated to comprise 2.4% of the U.S. older adult population or 2.7 million individuals, increasing to more than 5 million by 2060; when taking into consideration same-sex behavior, attractions, and romantic relationships, this number more than doubles to over 5 million today and more than 20 million older adults by 2060 [5].

An earlier 25-year review of existing research on sexual orientation and aging [6] analyzed 58 articles published between 1984 and 2008. The review assessed literature corresponding to the dimensions of the life course perspective as explicated by Elder [7]. Based on the analysis using life course theory, the review identified four key themes in the LGBTQ aging-related research, illustrating the evolution of the field. The first wave of research dispelled myths and negative stereotypes of sexual minority older adults as lonely, isolated, and having poor mental health, illuminating similarities between lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults and their heterosexual counterparts. A second wave emphasized psychosocial adjustment to aging, while the third focused on identity development and recognized the shifting historical and social contexts. The fourth wave emphasized sexual minority adults’ social relationships and community-based needs and support.

The two primary life course themes in the existing literature base at the time were the interplay of lives with historical times and social relationships. Existing studies explored how lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults’ experiences intersected with the broader historical and social context in which they lived, including how experiences of prejudice affected their aging, identity, and service utilization. This early research also sought to understand the importance of linked lives and social interactions, including the importance of families of choice, legally-defined family members, and social and community support networks. The review identified the life course tenets of timing of lives and agency as significantly underdeveloped and requiring further study.

In this paper, we examine articles published since the previous review to provide an evidence base for this growing field. Given recent changes in the growing empirical literature, we also expanded the population of interest to include queer-identified and trans* older adults. By synthesizing research findings across 66 articles published between 2009 and 2015 that focus on older LGBTQ adults and aging, we examine the key life course themes in the literature, as well as the theoretical and substantive, and methodological limitations and strengths in the literature base. By assessing the extent to and ways in which knowledge in the field has been advanced, as well as existing gaps in the research, we outline an Iridescent Life Course framework with a blueprint for future research.

Methodology

Like prior gerontological literature reviews [8, 6], we used a narrative systematic approach to structure an analysis and comparison of the studies as opposed to a meta-analytic method. The application of a meta-analytic approach is limited in fields that are underdeveloped and made up of a wide range of disciplinary and methodological approaches. In contrast, the narrative approach provides the foundation to assess comparability and divergence in findings as well as the relative strengths and limitations across studies despite the wide range of methods used.

This review included peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2009 and 2015 focusing on LGBTQ adults age 50 and older as well as those including age-based comparisons of those 50 and older with younger counterparts. As in the previous review, articles must have been written in English and include original empirical findings published in a peer-review journal with four or more study participants. A Boolean phrase search was applied to the following databases: PsychInfo, Sociological Abstracts, and Medline PLUS. Multiple search terms were included from the following areas: sexuality, sexual minorities, sexual identities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, trans * and gender. These search terms were then combined with aging-related terms: aging, older adults, elder, and gerontology (See Table 1). Articles that focused specifically on HIV/AIDS were excluded, since that body of literature has been the focus of several recent reviews among both older adults [9, 10] and the broader population [11, 12, 13].

Table 1:

Literature Review Search Terms

| Sexuality and gender-related |

Sexuality | Sexual Minority | Sexual Identities | Trans* | Gender Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sexual orientation | sexual minority | homosexual | transgender | gender queer | |

| sexual attraction | sexual minorities | non-heterosexual | trans | gender identity | |

| sexual behavior | sexual minority men | bisexual | transgendered | gender expression | |

| sexual preference | sexual minority | lesbian | transgenders | gender non-binary | |

| sexual identity | women | gay | gender non-conforming | ||

| homosexuality | queer | ||||

| bisexuality | gender expansive | ||||

| gender diverse | |||||

| AND | |||||

| Aging-related | aging | ||||

| older adults | |||||

| elder | |||||

| gerontology | |||||

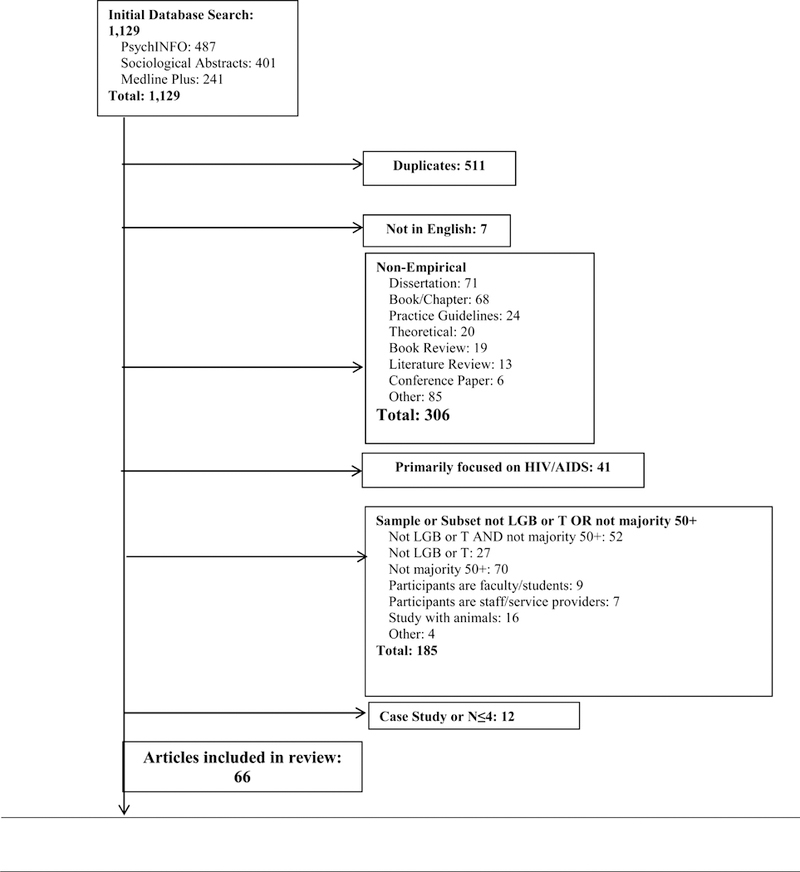

Figure 1 represents a flow chart of the search process, with a final sample of 66 articles. Two articles included findings from multiple studies; therefore, while 66 articles were included, study design and sample characteristics are reported from a total of 70 studies. One-hundred and eighty-four (184) articles were excluded based on sample ineligibility (e.g. did not include LGBTQ adults over age 50). Articles were systematically reviewed by two graduate students and coded by study type, research design and method, theory, population definition, sample characteristics, salient findings, and limitations. See Table 2 for an overview of the articles included in the review.

Figure 1:

Search Flow Diagram

Table 2:

Summary of Review by Article (listed alphabetically by author)

| Author(s), Year |

Sample | Design/Recruitment | Theoretical/ Conceptual |

Salient findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almack, Seymour, & Bellamy 2010 |

N= 15 SO: Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (percentage not specified) Sex/gender: Men (66.7%) and women (33.3%) Age: 50+ (93.3%), <49 (6.7%) Race/ethnicity: All White British Setting: South England |

Design: Focus groups Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used:None |

Findings: Focused on end of life care and bereavement among “non-traditional” social networks; friends were treated as chosen family and family was divided into those one does or does not have a close or supportive relationship with; family configurations changed with age; participants were concerned that social networks will shrink with age. |

| Averett, Yoon, and Jenkins 2012 |

N= 456 SO: Not explicitly specified, sample referred to as lesbian Sex/gender: Female (98%) Age: 51–86 (Mean = 62.9) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic Caucasian (86.9%) Setting: multi-state U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Sexual fluidity |

Findings: Summarized identity and sexual orientation, romantic/sexual relationships, erotic fantasies, current and past relationships with women and men, sexual activity, age-based comparisons, and same-sex marriage preferences. Findings indicated a strong identification with being a lesbian and fluidity in romantic and sexual relationships and 96.7% said same-sex marriage should be legal. |

| Averett, Yoon, and Jenkins 2011 |

N= 456 SO: Lesbian (91.3%), bisexual (3.7%), gay (2.7%), other (2.7%) Sex/gender: Female (98%) Age: 51–86 (Mean=63.1) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic Caucasian (86.9%), bi-or multiracial (5.1%), African American (3.3%), Hispanic/Latina (1.5%), API (.5%) Setting: multi-state U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Summarized demographics, sexual identity and orientation, current and past relationships, social life, health, service use, and experiences with discrimination; more than 60.5% were currently in an emotional, romantic or sexual relationship with a woman; more than 75% reported good or excellent physical health; more than 30% reported sexual identity-related discrimination in employment, family, and social relationships. |

| Brennan-Ing, Porter, Seidel, and Karpiak 2014 |

N= 239 SO: Gay (75.7%) and bisexual (24.3%) Sex/gender: All men Age: 50+ (Mean= 56.4) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (41.9%), Hispanic/Latino (30.2%), Non-Hispanic Black (27.9%) Setting: New York City |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Data from Research on Older Adults with HIV (ROAH), procedures not specified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Compared demographics and HIV-risk behaviors between HIV positive bisexual and gay men; bisexual men more likely to be racial minorities and had lower level of education; gay men were more likely to engaged in unprotected sex, partly explained by their higher use of poppers and erectile dysfunction drugs. |

| Brennan-Ing, Seidel, Larson and Karpiak 2014 |

N= 210 SO: Gay or lesbian (80.1%), bisexual (13.6%), queer (3.4%), questioning (1.5%), heterosexual (1.5%) Sex/gender: Male (70.5%), female (23.7%), transgender or intersex (5.8%) Age: 54+ (Mean=59.5) Race/ethnicity: Caucasian/White (61.7%), Black (32.0%), Hispanic (3.9%), other (1.5%), API (.5%), Al/AN (.5%) Setting: Chicago area |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Hierarchical Compensatory Theory Other theory used: None Methodology: Grounded theory (applied to open-ended questions) |

Findings: Describes demographic makeup and the formal and informal service needs, met or unmet, and services received; despite reporting an average of 3 health conditions, 75% rated their overall health to be good or excellent; women reported having larger social networks than men; most common unmet needs were for “housing, economic supports, help with entitlements” and “opportunities for socialization.” |

| Brennan-Ing, Seidel, London, Cahill, and Karpiak 2014 |

N= 155 SO: Gay or lesbian (55%), heterosexual (30%), bisexual (15%) Sex/gender: Men (78%), women (22%) Age: 50+ (Mean=55.5) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (34%), Non-Hispanic Black (33%), Hispanic/Latino (33%) Setting: New York City area |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Anderson Model of service utilization Other theory used: Hierarchical Compensatory Theory |

Findings: Participants “exhibit high rates of age-associated illnesses” earlier than expected, reporting an average of 3 or more conditions in addition to HIV; more than 50% classified as moderately or severely depressed; social networks were tenuous, limited, and cannot provide all needed supports. |

| Che, Siemens, Fejtek, and Wassersug 2013 |

N= 402 SO and sex/gender: Lesbian women (84.6%), gay men (15.4%) Age: 18+ Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: Canada (39.4%), U.S. (18.5%), UK (18.2%), Australia (11.5%), New Zealand (7.9%), other (4.4%) |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Canadian lesbians were more likely than American lesbians to hold hands in public; 51.5% hold hands often or very often; 41.5% had been verbally accosted while holding hands in public; 26.0% of participants deemed handholding to be a political act. |

| Cook-Daniels and Munson 2010* |

N

(by study)= 70; 56; 272 SO: Heterosexual, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, celibate, pansexual, omnisexual, queer, gay male, questioning (percent not specified) Sex/gender: MTF, TFM, cisgender male, cisgender female (percent not specified) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity (by sample): White (84%), multiracial (6%); White (79%), multiracial or African American (10%); not specified Setting: multi-state U.S. (6 international participants) |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, organization |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Three studies described experiences with sexual assault, elder abuse, and sexuality among older transgender individuals; of those who responded to a question regarding whether they had received unwanted sexual touch (44) 64% said “yes”; among those who said “yes” 66% know the perpetrator and 55% felt their abuser’s perception of their gender presentation or expression was a contributing factor; more than half did not report the incident; 64.8% had experienced psychological or emotional abuse. |

| Croghan, Moone, and Olson 2014 |

N= 495 SO: Lesbian (46.7%), gay (38.7%), bisexual (9.0%), queer or other (5.3%) Sex/gender: Cisgender (90.1%), transgender (9.9%) Age: 48+ Race/ethnicity: Non-Latino White (93.2%) Setting: Twin Cities Metro area Hispanic (18%) |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Focused on demographic profile and social relationships of participants; 59.5% were partnered or married and 39.1% were single; 50.7% lived with a partner or spouse and 39.5% lived alone; 35.4% had children; 63.7% reported family of origin was very or extremely accepting of them as an LGBT person; 22.2% were acting as a caregiver; 78.3% had an available caregiver. |

| Czaja et al. 2016 |

N= 124 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (74.2%), lesbian women (25.8%) Age: 50–89 (Mean= 65.7) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (72%),Hispanic (18%) Setting: South Florida |

Design: Focus groups Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Almost three quarters had been or were currently an informal caregiver; focus groups focused on aging-related concerns, barriers to accessing care or services, and caregiving experiences; gay men reported fears around discrimination, coming out, isolation, and lack of support; lesbians feared discrimination, coming out, and legal and financial issues; Hispanic gay men feared discrimination, financial issues, and a lack of awareness of their needs among service providers. |

| Emlet, Fredriksen- Goldsen, and Kim 2013 |

N= 226 SO: Gay (92.9%), bisexual (6.2%), other (.9%) Sex/gender: All Male Age: 50–86 (Mean=63.0%) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (77.3%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations, participants limited to men living with HIV |

Stated framework: Resilience theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: “[C]omorbidity, limitations in activities, and victimization [were] significant risk factors” for poor physical and mental health-related quality of life; social support and self-efficacy were protective for mental health-related quality of life and self efficacy was protective for physical health-related quality of life. |

| Erosheva, Kim, Emlet, and Fredriksen-Goldsen 2015 |

N= 1,913 SO and sex/gender: Gay cisgender men (59.0%), lesbian cisgender women (27.7%), transgender men and women (7.0%), bisexual cisgender men and women (4.9%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet, organizations |

Stated framework: Social capital theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: Global social network size was positively associated with “being female, transgender identity, employment, higher income, having a partner or child, identity disclosure to a neighbor, engagement in religious activities, and service use”; network diversity was positively associated with being younger, female, transgender, disclosure to a friend, religious activity, and service use. |

| Fabbre 2014 |

N= 22 interviews and 170 hours of observation SO: Not specified Sex/gender: All MtF transgender Age: 50–82 Race/ethnicity: European American (81.8%), African American (13.6%), Asian American (4.5%) Setting: Chicago area |

Design: Interviews and participant observation Recruitment: Flyers, internet, snowball |

Stated framework: Existential and queer time Other theory used: Life course perspective |

Findings: Participants described having only so much “time left” to live as one’s authentic self in the future and past “time served” conforming to social expectations based on their previously perceived or assigned gender. |

| Fabbre 2015 |

N= 22 and 170 hours of observation SO: Not reported Sex/gender: All MtF transgender Age: 50–82 Race/ethnicity: European American (81.8%), African American (13.6%), Asian American (4.5%) Setting: Chicago area |

Design: Interviews and participant observation Recruitment: Flyers, internet, snowball |

Stated framework: Queer theory Other theory used: Successful aging |

Findings: Transgender older adults experienced challenges to their gender identity that may be reconceptualized as queer “failures” or negotiating “success on new terms.” |

| Fokkema and Kuyper 2009 |

N= 3,681 SO and sex/gender: Heterosexual women (47.9%), heterosexual men (46.2%), sexual minority men (2.3%), sexual minority women (1.8%) Age: 55–89 Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: Netherlands |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Combines data from the Gay Autumn Survey recruited through organizations, internet, publications and NESTOR Survey, a stratified population-based sample |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Minority stress |

Findings: LGB older adults reported higher levels of loneliness and were less socially embedded than heterosexual counterparts; LGB older adults were also more likely to have experienced divorce, be childless, or have less contact with their children than heterosexuals. |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen, Cook-Daniels et al. 2013 |

N= 2,546 SO: Not stated Sex/gender: Transgender (6.8%), men (62.8%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (86.5%), Hispanic (4.4%), African American (3.5%), Native American (1.9%), API (1.6%), other (1.3%), multiracial (.7%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Resilience theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: Transgender older adults were at higher risk of experiencing “poor physical health, disability, depressive symptomatology, and perceived stress”; gender identity had a significant indirect effect on health outcomes via “fear of accessing services, lack of physical activity, internalized stigma, victimization, and lack of social support. |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet et al. 2012 |

N= 2,439 SO: and sex/gender: Gay men (59.6%), lesbian women (31.6%), bisexual women (2.4%), bisexual men (2.7%) Age: 50+ (Mean=67) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (87.1%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Resilience theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: Lifetime victimization, financial barriers to health care, obesity, and low physical activity were positively associated with poor general health, disability, and depression among LGB older adults; internalized stigma was positively associated with disability and depression; protective factors included social support and social network size. |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim 2015 |

N= 172,628 SO: Heterosexual (97%), gay or lesbian (2%), bisexual (1%), other (.2%) Sex/gender: Women (51%), men (49%) Age: 18+ Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (82.0%), Hispanic (7.9%), API (3.9%), African American (1.8%), multiracial (2.9%), American Indian (1.2%), other (.3%) Setting: Washington state |

Design: Telephone survey Recruitment: Data from Washington state Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), procedures not specified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Older adults showed higher non-response rates to sexual orientation measures, but non-response rates have decreased over time; in 2010, 1.2% of older adults responded “don’t know”/”not sure” and 1.55% refused to answer sexual orientation measures. |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim et al. 2015 |

N= 2,463 SO: Gay or lesbian (93%), bisexual (7%) Sex/gender: Transgender (4%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: White (86%), other (5%), Hispanic (4%), African American (3%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Resilience framework Other theory used: Successful aging |

Findings: Physical and mental health-related quality of life were positively associated with social support, social network size, physical and leisure activities, substance nonuse, employment, income, and being male; outcomes were negatively associated with discrimination and chronic conditions; the impact of discrimination was particularly salient among the oldest age group (80+). |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim et al. 2013 |

N= 96,992 SO and sex/gender: Women (58,319) and among women: Lesbian (1.0%), bisexual (.5%); Men (37,820) and among men: Gay (1.3%), bisexual (.5%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: White (~90% across all sexual orientation and gender subgroups) Setting: Washington state |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Washington state Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), procedures not specified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Life course |

Findings: Compared to heterosexuals, LGB older adults were at higher risk of disability, poor mental health, smoking and excessive drinking; lesbians and bisexual women were at higher risk of cardiovascular disease and obesity and gay and bisexual men were at higher risk of poor physical health and living alone compared to heterosexuals; lesbians reported higher rates of excessive drinking than bisexual women; bisexual men reported higher rates of diabetes and lower rates of HIV testing than gay men. |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim,Muraco andMincer 2009 |

N= 72 (36 caregiving dyads, demographics provided for caregiving recipients, followed by caregivers) SO: Gay or lesbian (66.7%), bisexual (33.3%); Gay orlesbian (60.0%), heterosexual (20.0%), bisexual(17.1%), other (2.9%) Sex/gender: Male (58.3%), female (41.7%); Male(69.4%), female (30.6%) Age: 50+; 18+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (51.4%), AfricanAmerican (20.0%), multiethnic (17.1%), Hispanic(8.6%), American Indian (2.9%); Caucasian(50.0%), African American (30.6%), multiethnic(13.8%), Asian (2.8%), American Indian (2.8%) Setting: Washington State |

Design: Interviews Recruitment:Organizations |

Stated framework: Resilience Framework Other theory used: Stress and coping theory |

Findings: Experiences of discrimination were associated withdepression among both care recipients and caregivers;relationship quality moderated the impact of discriminationon depression. |

| Gabrielson2011 |

N= 10 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All women Age: 55+ Race/ethnicity: White (90%), African American(10%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Allparticipantsinvolved indevelopment of aCCRC specializing inLGBT care |

Stated framework: Conceptual Framework developed by Ayres (2000) combines expectations, explanations, and strategies in a process of meaning making Methodological Influences: Case- oriented analysis and narrative analysis |

Findings: Past negative experiences with homophobia anddiscrimination were widespread in the contexts of family,workplace, and health care; positive experiences of findingLGBT community emphasized the importance of a sharedidentity and support; participants had explored their optionsfor their own aging such as caring for family members orcreating their own LGBT aging community and expresseddissatisfaction with currently available options. |

| Gabrielson, Holston, and Dyck 2014 |

N= 53 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All women Age: 55–80 (Mean=63.3) Race/ethnicity: All White Setting: Midwest U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment:Organizations,snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Pilot tested the Lubben Social Network Scale-Revised(LSNS-R) with a lesbian sample and minor modifications; findings indicated that the tool may not be reliable amongthis population due to the importance and distinctiveness offamilies of choice among older lesbians. |

| Gardner, de Vries, and Mockus 2013 |

N= 569 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (70.5%), lesbianwomen (17.7%), straight woman (7.0%), bisexualmen (2.4%), bisexual women (1.1%), transgendermale-to-female (.2%), straight men (1.1%) Age: 21+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (87%) Setting: Riverside County, California |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Events,organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used:None |

Findings: About one third of midlife and older gay men and lesbians reported fear of disclosing their sexual orientation and discomfort using mainstream senior services; lesbiansreported more fear and discomfort than gay men; olderlesbians and gay men reported more fear and discomfortthan younger individuals. |

| Gonzales and Henning-Smith 2014 |

N= 256,585 Couple type and sex/gender: Men in opposite-sexmarriages (51.4%), women in opposite-sexmarriages (44.8%), men in opposite-sexunmarried couples (2.1%), women in opposite-sex unmarried couples (1.7%), men in same-sexcouples (.3%), women in same-sex couples (.2%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: White (80% or more) Setting: National sample of U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Datafrom NationalHealth InterviewSurvey (NHIS),procedures notspecified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Conceptual discussion of discrimination and resilience |

Findings: Both men and women in same-sex relationshipswere less likely to report poor or fair health compared tothose in opposite-sex relationships; compared to those inopposite-sex marriages, both men and women in same-sexrelationships reported fewer chronic conditions, but higherlevels of psychological distress; men and women in same-sexrelationships also experienced favorable demographiccharacteristics as they were younger on average, more likelyto be college graduates, and had higher incomes. |

| Grigorovich 2014 |

N= 16 SO: Lesbian (43.8%), gay (25%), lesbian/queer(12.5%), lesbian/queer/dyke (6.3%), bisexual(6.3%), woman loving woman (6.3%) Sex/gender: All women Age: 55–72 (63.9) Race/ethnicity: White European (75%), Aboriginal(18.8%), women of color (6.3%) Setting: Ontario, Canada |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,organizations,snowball,participants musthave experiencedhome care inOntario orattempted toaccess theseservices in theprevious 5 years |

Stated framework: Feminist political economy Other theory used: None |

Findings: Common reasons for requiring home care services(HCS) included experiencing chronic pain, fatigue, conditionsthat limited everyday activities, issues or impairment withmobility, memory, vision, and hearing; participants gainedaccess to HCS through a health care professional (typicallyfollowing a hospital stay) or by contacting a community-careprovider directly; medical treatment was more immediatelysupplied than personal and housekeeping assistance; delayssometimes led to participants choosing not to set upservices; assessment of need was based on function and didnot account for other key factors; participants were not surehow to work within the system to get what they needed;additional informal assistance was often limited due tostrained family relations or a lack of children. |

| Grigorovich 2015 |

N= 16 SO: Lesbian (43.8%), gay (25%), lesbian/queer(12.5%), lesbian/queer/dyke (6.3%), bisexual(6.3%), woman loving woman (6.3%) Sex/gender: All women Age: 55–72 (Mean=64) Race/ethnicity: White European (75%), Aboriginal(18.8%), women of color (6.3%) Setting: Ontario, Canada |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,internet,organizations, snowball, participants musthave experiencedhome care inOntario orattempted toaccess theseservices in theprevious 5 years |

Stated framework: Feminist ethics of care perspective Other theory used: None |

Findings: Participants defined quality in-home care as beingresponsive and attentive to needs, involving them in theirown care process and decision-making, demonstratingrespect and care, and being comfortable with andknowledgeable about the needs of sexually diverse clients. |

| Grossman etal. 2014 |

N= 113 SO: Lesbian or gay (90.3%), bisexual (9.3%) Sex/gender: Men (67.3%), women (26.5%),transgender women (5.3%), transgender men(.9%) Age: 60–88 (Mean=72) Race/ethnicity: European/Caucasian/White(84.0%), African American/Black (5.3%), other(5.3%), Latino/Latina/Hispanic (4.0%), mixed race(.9%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: In relationships with caregivers, 22.1% of carerecipients had experienced at least one type of harm, 11.5%were exposed to more than one type, and 25.7% reportedthey know another LGB older adult who had experienced atleast one type of harm; 62.8% reported experiencing self-neglect, which negatively impacted psychological health. |

| Hostetler 2012* |

N= 136 (mixed-gender sample=60; gay mensample=76) SO: Gay or lesbian (91.9%), bisexual (2.7%), same-gender loving (.7%) Sex/gender: Male (53.3%) Age: 35+ (Mean=51.1; Mean= 53.9) Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (68.3%), AfricanAmerican (20%), Latino/a (10%), and AsianAmerican (1.7%); Caucasian (69.1%), AfricanAmerican (17%), Latino/a (9.6%), Asian American(4.3%) Setting: Large Midwestern city |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,organizations,publications |

Stated framework: Perceived control Other theory used: Life course perspective, person-environment approach |

Findings: Men had higher rates of aging concerns thanwomen; in both samples, perceived control was significantlynegatively associated with aging concerns; unexpectedly,community involvement was positively associated withaging concerns. |

| Hughes 2009 |

N= 371 SO: Gay (54.9%), lesbian (28.9%), bisexual (6.5%),queer (6.5%) Sex/gender: Transgender male-to-female (2.9%),transgender female-to-male (.7%) Age: 25 and under (16.4%) and over 25 (83.6%) Race/ethnicity: Australian Anglo-saxon (80.6%), culturally and linguistically diverse (5.9%), Aboriginal (3.2%) Setting: Australia |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Datafrom theQueenslandAssociation for Health Communities survey (QHAC),flyers, internet,organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Younger adults (<26 years) were more likely to beconcerned about being alone and older adults (66 and older)were more likely to be concerned about a lack of LGBT-friendly accommodations, loss of mobility, and declines inmental health or cognitive abilities; lesbians were moreconcerned about a lack of LGBT-specific services and lack ofrecognition for same-sex partners compared to gay menwho were more concerned about aging alone. |

| Jenkins Morales, Edmundson, Averett, and Yoon 2014 |

N= 55 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All women Age: 55–82 Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (81.8%), Latino (3.6%), Native American (1.8%), multiracial (1.8%) Setting: Not specified |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Disenfranchised grief |

Findings: Examined experiences of bereavement among olderlesbians; 76% reported experiencing an emotional barrier todealing with the death of a partner; common themesinclude disenfranchised grief, loneliness or isolation, anddiscriminatory experiences in legal, financial, and health carerealms. |

| Jenkins Morales, Kinget al. 2014 |

N= 151 SO: Gay (49.0%), lesbian (36.4%), bisexual (7.3%),multiple labels (7.3%) Sex/gender: Male (47.7%), female (45.7%), MtF(3.3%), FtM (.6%) Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (91.3%), multiracial(2.7%), American Indian (2.0%), other (2.0%),African American (1.3%), Asian (.7%) Setting: Greater St. Louis area |

Design: Survey Recruitment:Internet,organizations,publications,snowball |

Stated framework: Minority stress model Other theory used: None |

Findings: Compared Baby Boomer (78.1%) and SilentGeneration (21.9%) cohorts; Baby Boomers perceived morebarriers to healthcare and legal services, felt less safe intheir neighborhoods, had experienced more verbalharassment, and had fewer legal documents in place. |

| Jessup and Dibble 2012 |

N= 371 SO: Heterosexual (79.0%), lesbian or gay (15.9%),bisexual (4.0%) Sex/gender: Female (67.4%) Age: 55+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (72.0%) Setting: San Francisco area |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Compared mental health and substance use issuesacross cohorts and sexual identities; youngest age group(55–64) reported significantly more problems with substanceuse, PTSD, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts thanthose 65 and older; bisexuals reported more issues withdepression, anxiety, and suicidality than heterosexuals,lesbians, and gay men; mental health and substance usetreatment program use was low among all groups. |

| Kelly-Campbell and Atcherson 2012 |

N= 163 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (30.7%), heterosexualmen (28.2%), heterosexual women (20.9%),lesbian women (14.7%), bisexual men (3.1%),bisexual women (2.5%), gay women (1.8%) Age: 18+ Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Flyers,internet,organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Examined quality of life among LGB and heterosexualadults with hearing impairments; LGB individuals reportedgreater perceived impacts of their hearing loss on theiremotional lives and quality of life; among both LGB andheterosexual individuals, those who were partnered ormarried reported fewer impacts of their hearing loss ontheir quality of life. |

| Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen 2014 |

N= 2,444 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (60.0%), lesbianwomen (32.9%), bisexual women (3.6%), bisexualmen (3.4%) Age: 50+ (Mean=66.7) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (86.8%), other(5.5%), Hispanic (4.3%), Non-Hispanic AfricanAmerican (3.5%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Loneliness model Other theory used: None |

Findings: 55.5% of the sample were living alone; 36.9% livedwith a partner or spouse; 7.6% lived with someone otherthan a partner or spouse; gay and bisexual men were morelikely to live alone than lesbians and bisexual women; Non-Hispanic White participants were more likely to live with aspouse or partner than people of color; living arrangementwas significantly associated with loneliness where thoseliving with a partner or spouse reported the lowest levels ofloneliness. |

| Kong 2012 |

N= 14 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 60+ Race/ethnicity: All Chinese Setting: Hong Kong |

Design: Oral historiesand focus groups Recruitment: Notspecified,participants musthave lived in HongKong for 40+ years |

Stated framework: Post-structuralist conception of power/resistance Other theory used: Queer theory, geographies of sexuality |

Findings: Family homes fostered heteronormativeassumptions; early homosexual experiences largely carriedout in secret; public spaces were co-opted for seeking out agay scene and to find willing partners through the use ofcode words; many felt pressured to marry women as theyaged; some married women and some stayed single. |

| Kushner, Neville, and Adams 2013 |

N= 12 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 65–81 Race/ethnicity: All White and of European descent Setting: New Zealand |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,organizations |

Stated framework and

methodology: Critical gerontological approach Other theory used: None |

Findings: Themes acknowledge the pervasiveness ofhomophobia in participants’ lives; every participant hadbeen in a relationship with a man, but all but one werecurrently single; challenges to finding a partner includedlimited opportunities to find a companion, the participants’own age or perception of their own attractiveness;participants reported future care concerns including beingforced into the closet or out of one’s own home and lack ofaccepting and compassionate care. |

| Kuyper and Fokkema2010 |

N= 161 SO: Homosexual (78.1%), bisexual (21.9%) Sex/gender: Men (~60%), women (~40%) Age: 55–85 (Mean=64.6) Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: Netherlands |

Design: Survey Recruitment:Internet,organizations,publications |

Stated framework: Minority stress model Other theory used: None |

Findings: Having a partner and extensiveness of social networkwere negatively associated with loneliness; LGB socialnetworks were more protective than general socialnetworks; discrimination and expected prejudice werepositively associated with loneliness; different kinds ofloneliness (general, emotional, and social) were impacted bydifferent factors. |

| Lee and Quam 2013 |

N= 1,201 SO: Bisexual (37.5%), gay (31.8%), lesbian (31.4%),heterosexual (4%) Sex/gender: Male (53.8%), female (46.2%), sexdifferent from assigned at birth (10.1%) Age: 45–64 Race/ethnicity: White (78.6%), AfricanAmerican/Black (8.3%), Hispanic (6.1%), other(6.0%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Secondary dataanalysis |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Compared individuals living in urban (43.1%) andrural (14.6%) locations; those in urban areas reported higherlevels of outness and self-rated importance of LGBT identity;groups were similar on guardedness toward the sexualidentity among parents, bosses/supervisors, and health careproviders; rural participants were more guarded amongfriends, siblings, neighbors, coworkers, and religiouscommunity members. |

| Lyons, Pitt, and Grierson2013 |

N= 840 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 40–78 Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: Australia |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Internet |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Men in their 60’s had more friends and were morelikely to feel supported by their friends than those in their40’s and 50’s; men age 60 and older were more likely to livealone and had the highest self-esteem. |

| MetLife Mature Market Institute 2010 |

N= 1,000 SO/gender: Gay (52%), lesbian (33%),bisexual (15%) Age: 40–61 Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment:Procedures notspecified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: One quarter reported having cared for a familymember or friend in the past 6 months and proportions ofcaregiving were similar across men and women; one fifthwere not sure who would care for them if the need arose;most frequent aging-related fears included outliving theirincome, being dependent on others, and experiencingdiscrimination in later life. |

| Muraco and Fredriksen-Goldsen 2014 |

N= 72 (36 caregiving dyads, demographics arereported for care recipients, followed bycaregivers) SO: Gay or lesbian (67%), bisexual (33%); Gay orlesbian (63%), heterosexual (20%), bisexual (17%) Sex/gender: Not specified Age: 50+; 18+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (~50%) African American(20%), multiethnic (17%), Latino (9%), NativeAmerican (3%); Caucasian (~50%), AfricanAmerican (31%), multiethnic (13%), Asian (3%),Native American (3%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment:Organizations |

Stated framework: Exchange theory and Communal relationships theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: Many care recipients reported having a mentalhealth condition (66.6%), arthritis (44.0%), high bloodpressure (37.5%), and diabetes (31.5%); 38% of caregiverswere providing 20 hours per week of care or more;partnered care recipients reported positive experiences ofexpressions of love and commitment from their caregivers;when asked for their worst experiences the most commonresponse was that there was no worst experience. |

| Neville, Kushner, and Adams 2015 |

N= 12 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 65–81 Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: New Zealand |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Events |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Analyzed coming out narratives of older gay men inwhich three common narratives or themes were identified:1) early gay experiences often included experimentingsexually with other men before identifying as gay, 2) thiswas followed by a period of trying not to be gay or trying tohave relationships with women for many interviewees, and 3) acceptance marks a period of time when they acceptedtheir identity as a gay or same-sex attracted men. |

| Orel 2014* |

N (by study)= 26; 1,150; 49 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (50%), lesbianwomen (38.5%), bisexual women (11.5%);Lesbian or bisexual women (64%), gay men(36%); Lesbian women (63.3%), bisexual women(14.3%), gay men (22.4%) Age: 65–84; 64–88; 40–79 Race/ethnicity: European American (65.4%),African American (23.1%), Latino/a (7.7%), AsianAmerican (3.8%); Non-Hispanic White (91%),African American (8%), Latino (2%); Caucasian(85.7%), African American (10.2%), other (2.0%) Setting: Midwest U.S. and Texas state |

Design: Focus group;needs assessmentsurvey (with open-ended questions);interviews Recruitment:Organizations,snowball |

Stated framework: Life course perspective (specifically applied to 3rd study) Other theory used: None |

Findings: Key areas of needed services identified include:medical/health care, legal, institutional or housing, spiritual,family, mental health, and social services; in interviews, LGBgrandparents reported that their relationship withgrandchildren was mediated by their adult children and theyacknowledged the need for and challenge to forming an LGBgrandparent identity, the centrality of their sexualorientation to the grandparent-grandchild relationship, andthe impact of homonegativity on the relationship. |

| Parslow and Hegarty 2013 |

N= 7 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All women Age: 48–62 Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: UK |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Minority stress and caregiving stress Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: Four themes were revealed in interviews withlesbians providing care to older relatives: feelings of dutyand obligation in providing care, loss of lesbian identity, thechallenge of maintaining connections with lesbiancommunities, and the importance of boundary settingbetween caregiving and the rest of one’s life. |

| Pilkey 2014 |

N= 11 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 50+ Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: London area |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Datafrom a larger study,flyers, internet,snowball |

Stated framework: Queer theory Other theory used: Social constructionism |

Findings: Interviews revealed ways in which gay men resistheteronormativity in their homes; the most common formof resistance was displaying homoerotic artwork which canbe varied from explicit to more hidden or understated; lesscommon resistive displays included music collections,decorating styles, rainbow-themed items, and photos ofsame-sex partners; others did not display items that calledattention to their sexuality because they did not feel theneed for outright resistance in what had become a relativelyaccepting society; both can be seen as means of resistance,by either putting homosexuality on display or by normalizinghomosexuality. |

| Porter, Ronneberg, and Witten 2013 |

N= 289 SO: Heterosexual (32.5%), gay (32.5%), bisexual(28.0%), lesbian (17.0%), asexual (9.0%) Sex/gender: All transgender Age: 51+ Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (92.0%) Setting: International |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Datafrom the TransMetropolitan LifeSurvey (TMLS) |

Stated framework: Successful aging Other theory used: None |

Findings: 73.4% felt that they were aging successfully; 29.4%reported having a disability; 34.6% were chronically ill;93.7% were somewhat or mostly out about their genderidentity, but outness varied by context; being Non-HispanicWhite, highly educated, and having a high income predictedsuccessful aging, but religious affiliation did not. |

| Putney 2014 |

N= 12 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All women Age: 65–80 (Mean=71) Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (91.7%), Caucasian andNative American (8.3%) setting:U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment:Snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Psychological well-being Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: Eleven participants described their feeling towardtheir pets as “love”; 10 described pets’ affection as non-judgmental or unconditional; 9 described the challenges ofowning a pet including financial strain, managing healthissues, and finding care for them. |

| Rosenfeld 2009 |

N= 28 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (50%), lesbianwomen (50%) Age: 64–89 (Mean=72.5) Race/ethnicity: White (78.7%), Latino/a (14.3%),African American (7.1%) Setting: Los Angeles area |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Datafrom a largerqualitative study,organizations,snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Intersectionality, queer theory Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: All informants reported instances of trying to pass asheterosexual including strategies such as not sharing biographical information, policing one’s body and dress, and avoiding being seen with non-passing homosexuals; individuals who brought attention to their sexuality were described as putting others and themselves at risk. |

| Rowan and Butler 2014 |

N= 20 SO: All lesbians Sex/gender: All women Age: 50–70 (57.6%) Race/ethnicity: White (95%) and African American(5%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Snowball |

Stated framework: Narrative gerontology Other theory used: Phenomenology |

Findings: Participants described receiving support and aid from partners, family members, and friends during recoveryfrom alcoholism and attaining sobriety; 60% described goingthrough formal treatment and 75% described theimportance of 12-step recovery programs; lesbian peers andprofessionals offered a particularly important kind ofsupport as mentors; all participants evidenced resiliency infacing adverse situations related to aging, alcoholism, andtheir sexual identity. |

| Sagie 2015 |

N= 209 SO and sex/gender: Gay men (68.4%), lesbianwomen (31.6%) Age: 56–80 (Mean=62.9) Race/ethnicity: Not specified Setting: Israel |

Design: Interview Recruitment:Organizations |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None | Findings: Participants reported a “medium-high” level ofsubjective well-being; physical and mental health, hope, andcommunity availability of services were significant predictorsof subjective well-being. |

| Simpson 2013 |

N= 27 interviewees and 20 hours of observation SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 39+ Race/ethnicity: White British (88.9%), mixed-race(3.7%), oriental (3.7%), Irish European (3.7%) Setting: Manchester area |

Design: Interviews, participant observation in barsand clubs Recruitment:Organizations, snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Ageing capital (informed by Bourdieu’s social capital) |

Findings: Three primary themes included: alienation fromqueer community as an aging man, growing ambivalencetoward the gay scene, and finding agency with age. |

| Siverskog 2014 |

N= 6 SO: Not specified Sex/gender: 2 transsexual women, 1 genderqueer,1 has kept transgender identity on the down lowin later life, 1 identifies as a man but has femalegender expression full time, 1 identifies as a man with a transsexual background (assigned female at birth) Age: 62–78 Race/ethnicity: Not stated Setting: Sweden |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Flyers,organizations, snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: Themes included intersections of age and genderover the life course (impact of historical context), lack ofawareness or knowledge of transgender issues in varioussocial contexts, and the impact of previous experiences withaccessing health care and social services. |

| Slevin and Linneman 2010 |

N= 10 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 60–85 Race/ethnicity: All White Setting: New York City area |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Data from a larger qualitative study, snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Intersectionality, embodied masculinity |

Findings: Themes include aging and acceptance of self and body, constructing and managing identities, achieving masculinity, disapproval or distancing from feminine expression, and ageism in gay communities. |

| Stanley and Duong 2015 |

N= 5,138 SO: Lesbian, gay, bisexual (4.1%), heterosexual (95.9%) Sex/gender: Female (61.2%) Age: 50–98 (Mean=65.3) Race/ethnicity: Non-white (48.5%) Setting: New York City |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Data from NYC Community Health Survey, procedures not specified |

Stated framework: Minority stress model Other theory used: None |

Findings: Among LGB older adults, 23.9% reported receiving counseling and 23.4% reported taking psychiatric medication in the last year; LGB respondents were significantly more likely to have received counseling and psychiatric medications than heterosexuals and this association was not mediated by psychological distress, alcohol use, or poor general medical health. |

| Stein, Beckerman, and Sherman 2010 |

N= 16 SO and Sex/gender: Gay men (75%), lesbian women (25%) Age: 60–84 Race/ethnicity: White (87.5%), African American (12.5%) Setting: New York City (75%), New Jersey (25%) |

Design: Focus groups Recruitment: Recruited from one long-term care facility and one community-based setting |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Participants feared being rejected, neglected, not accepted or respected by healthcare providers, especially personal care aides; they preferred gay-friendly care and feared having to go back into the closet if placed in mainstream facility; suggestions include staff training and gay-specific or gay-friendly living options. |

| Sullivan 2014 |

N= 38 SO: Gay (57.9%), lesbian (28.9%), bisexual (5.3%) Sex/gender: Men (60.5%), women (39.5%), transgender (7.9%) Age: 51–85 (Mean=71) Race/ethnicity: White (86.8%), African American (5.3%), Latino/a (5.3%), White Middle Eastern (2.6%) Setting: California state |

Design: Focus groups Recruitment: Recruited from 3 existing LGBT senior living communities |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Socioemotional selectivity theory Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: Emphasized the need for acceptance, inclusivity, and diversity; participants chose to live in an LGBT-specific community to feel accepted, because they knew other residents, and they perceived comfort and safety; they chose not to live in a mainstream community out of fear of isolation and social rejection. |

| Valenti and Katz 2014 |

N= 76 (17 interviews) SO: Lesbian (72.4%), gay (13.2%), queer (6.7%), bisexual (6.6%), heterosexual (1.3%) Sex/gender: All women Age: 35–91 (Median age of interviewees=66) Race/ethnicity: White (59%), African American/Black (13%), Latino/a (18%), Native American (3%) Setting: multi-state U.S. |

Design: Survey and interviews Recruitment: Flyers, internet, organizations, snowball |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Survey respondents who were acting as a caregiver were asked to participate in follow-up interviews; four themes emerged in open-ended questions including the need for: supportive and knowledgeable health care workers, recognition of same-sex partners and their rights, sensitivity training, and accepting environments; interviews revealed past negative experiences with staff. |

| Van Wagenen, Driskell, and Bradford 2013 |

N= 22 SO: Gay or lesbian (90.9%), bisexual (4.5%), heterosexual (4.5%) Sex/gender: Male (50%), female (50%) Age: 60–80 Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (82%), African American (18%) Setting: Boston Metropolitan area |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Snowball |

Stated framework: Successful aging Other theory used: None Methodology: Grounded theory |

Findings: Findings were coded into four domains: physical health, mental health, emotional state, and social engagement; based on these domains, four gradations of success emerged; few participants experienced “traditional success” or absence of issues in all domains, but several exhibited coping with challenges through “surviving and thriving” or “working at it” with very few “ailing.” |

| Wight et al. 2015 |

N= 312 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 48–78 (Mean=60.7) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (90.4%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) and Aging Stress and Health among Gay Men Study (ASH-GM), procedures not specified |

Stated framework: Social stress process Other theory used: Concept of internalized gay ageism |

Findings: Findings indicate that internalized gay ageism can reliably be measured among older gay men and can be differentiated from perceived ageism and internalized homophobia; internalized ageism was positively associated with depressive symptomology and this association was not moderated by one’s sense of mattering. |

| Wight, LeBlanc, Meyer, and Harig 2012 |

N= 202 SO: All gay Sex/gender: All men Age: 44–75 (Mean=56.9) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (87.1%) Setting: Los Angeles area |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), procedures not specified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Minority stress |

Findings: Positive affect was negatively associated with felt stigma, concerns about independence, financial concerns, and being employed full time; positive affect was positively associated with having a same-sex legal spouse (but not an unmarried partner), mastery, emotional support, and self- rated health; depressive symptoms were positively associated with stigma, HIV bereavements, and independence concerns; depressive symptoms were negatively associated with self-rated health, same-sex domestic partnership, same-sex marriage, mastery, and older age. |

| Williams and Fredriksen- Goldsen 2014 |

N= 2,150 SO: Gay or lesbian (96.9%), bisexual (5.1%) Sex/gender: Male (64.8%), female (35.2%) Age: 50–95 (Mean=66.8) Race/ethnicity: White (87.4%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Organizations |

Stated framework: Social integration theory Other theory used: None |

Findings: Partnered individuals were significantly younger, more likely to be female and Non-Hispanic White, and had higher educational and class status than those who were single; having a same-sex partner was significantly associated with better self-reported health and fewer depressive symptoms; relationship duration did not significantly influence association between partnership and health. |

| Witten 2014 |

N= 1,963 SO: Bisexual (18%), lesbian (14%), other (9%), pansexual (8%), gay (7%), refused to label (6%), asexual (4%), questioning (4%), celibate (3%), omnisexual (1%) Sex/gender: All identify with trans, including: feminine, androgynous, gender queer, gender bender, transgender, third gender, transman 13%, transwoman, transblended, two spirit, and questioning Age: 18+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (85%), Other (4%), Hispanic (3%), Multiracial (3%), Black (2%), Asian (2%), First Nations (1%) Setting: International, U.S. (81%), Canada (9%), Australia (1%), Sweden (1%), United Kingdom (1%), other (7%) |

Design: Survey (with open-ended questions) Recruitment: Transgender Metlife Survey (TMLS), snowball sample |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Intersectionality |

Findings: Summarized end-of-life care concerns, spiritual affiliations, challenges related to chronic illness and disability, and comparisons by age group; 30.1% reported having a chronic illness and 27.1% reported having a disability with no significant differences by age; younger individuals were less likely to have a pension or retirement plan; more than half of respondents were moderately or extremely concerned about losing independence as they aged. |

| Witten 2015 |

N= 276 SO: All lesbian Sex/gender: All participants identified as trans, including: feminine (73.2%), other identities (14.1%), transgender/third gender (9.8%), and masculine (2.7%) Age: 18+ Race/ethnicity: Caucasian (93.8%), Hispanic (1.8%) Setting: International, U.S. (89.4%), Canada (6.2%), Thailand (1.8%), Australia (.9%), Sweden (.9%), Mexico (.9%) |

Design: Survey Recruitment: Transgender Metlife Survey (TMS), snowball sample |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: None |

Findings: Summarized demographic characteristics, pension and retirement planning, social relationships, end-of-life preparation and concerns about aging and end-of-life care; 61.0% had a retirement plan; 51.3% were in a committed relationship, 31.5% were single, and 11.7% were separated/divorced; 47.8% had completed a will, 39.8% had completed a living will, and 38.1% had a durable power of attorney. |

| Woody 2014 |

N= 15 SO and Sex/gender: Lesbian females (73.3%), gay males (26.7%) Age: 58–72 (Median=64) Race/ethnicity: African American (53.3%), Black (26.7%), Caribbean African American (6.7%), biracial (Caucasian and African American, 6.7%), multiracial (Native American, Black American, and Caucasian , 6.7%) Setting: U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Internet, organizations |

Stated framework: Black feminist theory Other theory used: Minority stress Methodology: Phenomenological Model |

Findings: Themes included a sense of alienation from the African American community, deliberate concealment of one’s sexual identity and orientation, aversion to LGBT labels, perceived discrimination and alienation from organized religion, feelings of grief and loss related to aging, isolation, and fear of financial and physical dependence. |

| Woody 2015 |

N= 15 SO: 57–72 Sex/gender: All lesbian Age: All women Race/ethnicity: All African American or Black Setting: U.S. |

Design: Interviews Recruitment: Not specified |

Stated framework: None Other theory used: Minority stress |

Findings: Themes included invisibility, alienation and loss within the African American community, by any other name (hesitation to use the terms “lesbian” or “queer”), safety concerns, isolation, experiences of minority stress, and resilience. |

Note: In demographic characteristics summary, “API” refers to Asian/Pacific Islander; “AI/AN” refers to American Indian/Alaskan Native; “cisgender” refers to non-transgender individuals.

Denotes articles that report findings from more than one study.

All authors analyzed each dimension across the full range of articles. Sample characteristics, study design, recruitment procedures, and methods were compiled across articles to analyze representation of various populations and common strengths and limitations in terms of sampling procedures and methods applied. Theories were organized into substantive and methodological theories to assess what number of articles applied a theoretical framework or theoretical concepts, which revealed the extent of theory used across articles and common theoretical concepts represented. Salient findings were analyzed next to assess the topical domain areas represented in the field and how they corresponded to the four existing dimensions of the life course perspective, which enabled a comparison of how trends in the field and areas of focus had shifted over time.

Study Design and Sample Characteristics

All studies were cross-sectional. More than half (56.3%) used quantitative methods, 39.4% used qualitative methods, and three studies applied mixed methods. Data collection included surveys (56.3%), interviews (35.2%), and focus groups (7.0%, n=5). Three studies also used participant observation in addition to interviews [14, 15, 16]. A majority of studies relied on community-based samples (85.1%) with 4.5% utilizing population-based representative data (n=3) [17, 18, 19]. Most of the studies incorporated multiple types of recruitment, most commonly outreach via health, social, and other community-based service organizations or businesses (54.8%), snowball sampling (27.4%), internet/social media (23.3%), flyers and publications such as newsletters and newspapers (20.5%). Two studies used public venues or events. The recruitment process was not described for 23.3% studies. Secondary data analyses were used in 18.9% of studies.

Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 256,585 participants, with a median size of 151 participants. Most studies (71.2%) included only participants age 50 and older, 16.9% had participants age 60 and older, and 5.6% had participants age 65 and older. Participants younger than 50 were included in 21.1% of studies, which incorporated age-based comparisons. While the majority of the studies reported on a U.S. sample (73.2%), four studies reported on international samples [20, 21, 22, 23]. Twenty-one percent (21.1%) had samples exclusively from outside the U.S., including Australia [24, 25], Canada [26, 27], Hong Kong [28], Israel [29], Netherlands [30, 31], New Zealand [32, 33], Sweden [34], and U.K. [35, 36, 37, 16].

The population of interest varied in definition and measurement across studies. The most common aspect of sexuality identified for study in the articles was sexual orientation, although this was often measured with a single sexual identity question. The most common response categories were lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual or straight. Less frequent responses included “homosexual” in place of or in addition to gay and lesbian (reported in 8.1%, n=6), “queer” (8.1%, n=6), “questioning” (5.4%, n=5), and three reported “pansexual/omnisexual.” Three studies used “celibate/asexual” (4.1%), two used “dyke” and “woman loving woman” [26, 27], and one used “same-gender-loving” [38]. Three studies reported on sexual behavior, primarily “men who have sex with men” [39, 40, 41].

A majority of studies included participants across multiple sexual identities (69.0%), most often lesbian-, gay-, and bisexual-identified older adults (28.2%), followed by 9.9% including only lesbian- and gay-identified individuals (n=7), and 14.1% comparing with heterosexuals. Eighteen studies included a single sexual identity group, including 12.7% with gay men only and 12.7% with lesbians only. While 51.4% of studies included bisexuals, no studies had only bisexuals. Four studies did not report the sexual orientation or identity of the participants, but instead referred to the population of interest as sexual and/or gender minorities or members of “same-sex” couples.

Gender and gender identity was assessed through a variety of means. Approximately 10% (9.9%, n=7) of the studies included only trans*-identified participants, with an additional 19.7% including some trans participants. The most common terms used to assess trans identities were transgender (18.3%), MTF (male to female) (8.1%, n=6), and FTM (female to male) (4.2%, n=3). In two studies, a broader range of terms were used to refer to gender identity and expression, including “transsexual”, “gender queer”, “gender bender”, “trans-blended”, “third gender”, “cisgender”, “cismale”, “cisfemale”, “masculine”, “feminine”, “two spirits”, and “androgynous.” Some studies included women only (15.5%) or men only (15.5). Other studies used sex, gender, and/or sexual identity-related terms interchangeably. For instance, one study assessed sex as being “male” or “female,” but referred to the participants as “men” or “women.” Another assessed trans* individuals via a sexual identity question. Only one study included intersex participants.

Most samples were made up of a majority of White/Northern European/Caucasian (hereafter referred to as “White”) participants, with 5.6% of samples including only White participants (n=4). Among the studies, 34.8% included African American/Black participants, 31.8% Hispanic/Latino/a, 21.2% Asian/Pacific Islanders, 19.7% Native Americans/Indigenous and 16.7% others. About one-quarter (25.8%) had multi-racial participants. Nearly 12% (11.3%) of samples were 90% or more White and another 28.1% were 80% or more White. Two studies reported findings from African American or Black participants only and one sample included only Chinese participants. The race/ethnicity of participants was not reported in 19.2% of studies, more than half of which were conducted outside of the U.S.

Theories Applied

A conceptual framework was identified in 43.9% of articles. Five key theoretical frameworks appeared, including critical (12.1%, n=8), ecological/socio-cultural (7.5%, n=5), resilience (7.5%, n=5), stress (6.0%, n=4), and positive aging (4.5%, n=3) theories. Methodological theories were utilized in 10.0% (n=7) of the studies. An additional 16.4% of articles provided conceptual framing of key concepts but were not identified as a theoretical framework for the study.

Critical theories (10.6%, n=8) were applied to analyze the ways in which aging is socially constructed through relations of power [42]. As applied, these theories provided a critique of dominant or traditional ways of knowing, challenged common assumptions, examined intersectional identities, and centered the experiences of older adults who are marginalized. Six used ecological and socio-cultural frameworks, such as Hierarchical Compensatory Theory [48] and the Anderson Model of service use [49] that were applied to studies on formal and informal service needs and use. A resilience framework was used in five studies [41, 57, 60, 61, 62] to investigate social determinants and risk and protective factors and their relationship to aging, health, and well-being. As articulated within the tradition of positive psychology, successful aging was utilized in three articles to analyze positive aging-related outcomes among LGBT older adults [15, 21, 63]. Stress-related theories were used to assess experiences such as loneliness, poor mental health, and service needs [31, 52, 53, 54]. A life-course perspective was explicitly applied in two articles examining lifespan and life course development [38, 55], with several others referencing the “life course” as a key concept, but not as an overall framework [56, 14, 18, 57, 58, 34, 59, 22].

Two specific methodological theories were used. Grounded theory was used in 10.6% (n=7) of articles to assess meaning and generation of theory through analysis of qualitative data [34, 36, 48, 59, 63, 64, 65]. Narrative gerontology was used to explore the experiences of older lesbians in attaining sobriety [58]. See Table 3 types of theory utilized in the studies.

Table 3:

Theoretical Perspectives by Theory Type and Authors

| Theory Type (total N) | Conceptual Framework | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Substantive Theories (29) | ||

| Critical (8) | Queer Theory and Existential Time | Fabbre (2014) |

| Queer Theory | Fabbre (2015), Pilkey (2014) | |

| Feminist Political Economy | Grigorovich (2014) | |

| Feminist Ethics of Care | Grigorovich (2015) | |

| Black Feminist Theory | Woody (2014) | |

| Critical Gerontology | Kushner, Neville, & Adams (2013) | |

| Post-Structuralist conception of power/resistance | Kong (2012) | |

| Ecological and Socio-cultural (5) | Social Capital | Erosheva, Kim, Emlet, and Fredriksen-Goldsen (2015) |

| Social Integration | Williams and Fredriksen-Goldsen (2014) | |

| Exchange Theory and Theory of Communal Relationships | Muraco and Fredriksen-Goldsen (2014) | |

| Loneliness Model | Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen (2014) | |

| Hierarchical Compensatory Theory | Brennan-Ing, Seidel, Larson and Karpiak (2014) | |

| Resilience (5) | Resilience Framework | Emlet, Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim (2013), Fredriksen-Goldsen, Cook-Daniels et al. (2013), Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet et al. (2012), Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim et al. (2015), Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Muraco, and Mincer (2009) |

| Stress-Related (4) | Minority Stress Model | Jenkins Morales, King et al. (2014), Kuyper and Fokkema (2010), Stanley and Duong (2015) |

| Social Stress Process | Wight et al. (2015) | |

| Positive Aging (3) | Successful Aging | Fabbre (2015), Porter, Ronnenberg and Witten (2013), Van Wagenen, Driskell and Bradford (2013) |

| Other (4) | Life Course Perspective | Fabbre (2014), Orel (2014) |

| Meaning Making | Gabrielson (2011) | |

| Perceived Control | Hostetler (2012) | |

| Methodological Theories (8) | ||

| Grounded Theory | Brennan-Ing, Seidel, Larson and Karpiak (2014), Parslow and Hegarty (2013), Putney (2014), Rosenfeld (2009), Siverskog (2014), Sullivan (2014), Van Wagenen, Driskell and Bradford (2013) | |

| Narrative Gerontology | Rowan and Butler (2014) | |

Key Themes

In the next section, the systematic review of findings is organized according to the four key domains of the life course, including the interplay of lives with historical times, social relationships, timing of lives, and agency.

Interplay of Lives and Historical Times

Consistent with a life course perspective, the interplay of lives and historical times accounts for the contexts within which LGBTQ older adults have lived. The trauma and adverse experiences that LGBTQ older adults encountered because of being perceived as LGBTQ was the most common theme in this domain, with existing research focused primarily on discrimination (15% of studies) and victimization (12%). These studies reported on the frequency [39, 57, 52] and consequences [61, 62, 57] of such adverse experiences.

While none of the population-based research studies assessed the prevalence of such traumatic and adverse experiences, a large community-based study reported an average of 6.5 incidents of victimization and/or discrimination over the life course [57]. Transgender older adults compared to non-transgender counterparts had the highest rates of victimization and discrimination, with reports ranging from 57% [39] to 69% of the participants [60]. Rates of lifetime discrimination and victimization were associated with poorer physical health [57, 61], disability [57, 61], chronic illness [60], depression [57, 61] and lower mental health-related quality of life [41].

Rates of victimization and discrimination of LGBTQ older adults differed by demographic characteristics; higher rates were associated with being transgender [62], being male [52], and lower socio-economic status [66]. Other adverse experiences included ageism and alienation within gay communities [16, 67] as well as heterosexism in faith-based communities [43, 68]. Qualitative studies documented LGBTQ older adults’ experiences and concerns of discrimination, mistreatment, and neglect in service settings such as in-home care, workplaces, and health care settings [69, 27, 32, 70, 59].

Internalized stigma, having negative views of one’s own sexual or gender identities, was most often conceptualized as resulting from the historical context of LGBTQ older adults’ lives. For example, four studies reported findings related to internalized stigma, which was associated with higher rates of depression and disability [62], loneliness [47], poor physical health [61], and poor quality of life [41]. Internalized gay ageism among older gay men was associated with higher rates of depression [54].

Other types of adverse experiences were reported that were not directly linked in the literature to historical times. For example, elder abuse and neglect were reported, but less frequently than LGBTQ-related victimization and discrimination. Among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults age 60 and older who attended community-based social and recreational programs, 22.1% reported having experienced at least one type of abuse from their caregiver, with 11.5% reporting more than one type [71]. The most common types of abuse were emotional, verbal, physical, and neglect. In a study of transgender older adults, two-thirds reported having received unwanted sexual touch, with 55% reporting such abuse was related to their perceived gender expression or presentation [72].

Adverse experiences and lack of access to resources over one’s lifetime can exacerbate inequalities and result in cumulative disadvantage [73], with multiple consequences in later life. A new theme that emerged in the recent LGBTQ aging-related literature was health, including physical health, mental health, health behaviors, and health-related quality of life and well-being. Much of this research addressed poor health, although some studies found that LGBTQ older adults reported good mental health [39, 71], physical health [62, 61, 57], and quality of life [57]. Yet there was mounting evidence that LGBTQ older adults experienced health disparities with higher rates of poor general health, disability, functional impairment and psychological distress than heterosexuals of similar age [18, 62]. While health disparities were evident across the LGBTQ groups, those identified at elevated risk included transgender [62], bisexual [61, 74], lesbian [61], and unemployed [75] older adults, and those needing caregiving assistance [60]. Among gay men, one-third reported having a diagnosis of HIV [75], and the progression of HIV to AIDS and comorbidities were negatively associated with quality of life [41]. Findings related to age were mixed. In one large community-based sample, quality of life was highest among the middle age group (65–79) and similar among the younger (50–64) and oldest (80+) groups [57], but another study found that the youngest participants (55–64) reported the highest rates of anxiety and PTSD [74]. The oldest LGBTQ adults reported the most chronic conditions and lowest physical health-related quality of life [57, 47].

Adverse health behaviors, including the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit substance use [40, 61, 74, 53] and at-risk sexual behavior [40], were another common focus identified in the literature that did not align directly with life course theory. In terms of demographic differences, lesbian, gay, and bisexual men and women, compared to heterosexuals, were at elevated risk of excessive drinking [18]. Among men, bisexuals were less likely to have engaged in unprotected sexual activity but more likely to be smokers compared to gay men [40]. For trans older adults, physical activity was negatively associated with rates of poor physical health, disability, and depression and anxiety; trans older adults reported less engagement in physical activity than non-transgender sexual minorities [62]. There was also evidence that substance use was related to sexual risk behavior; for example, among older gay and bisexual men living with HIV, unprotected sex was not predicted by past or current alcohol use but was associated with current and lifetime use of crystal meth, cocaine, and club drugs (e.g. GHB, ketamine, Ecstasy) [40]. Fewer studies considered positive health behaviors, although a few assessed physical and leisure activities [62, 61, 57], which were associated with better quality of life and lower rates of depression [61, 57].