Abstract

Objective

High doses of sodium salicylate (SS) are known to induce tinnitus, general hyperexcitability in the central auditory system, and to cause mild hearing loss. We used the auditory brainstem response (ABR) to assess the effects of SS on auditory sensitivity and temporal processing in the auditory nerve and brainstem.

Design

ABRs were evoked using tone burst stimuli varying in frequency and intensity with presentation rates from 11/sec to 81/sec. ABRs were recorded and analyzed prior to and after SS treatment in each animal, and peak 1 and peak 4 amplitudes and latencies were determined along with minimal response threshold.

Study Sample

Nine young adult CBA/CaJ mice were used in a longitudinal within-subject design.

Results

No measurable effects of presentation rate were found on ABR threshold prior to SS; however, following SS administration increasing stimulus rates lowered ABR thresholds by as much as 10 dB and compressed the peak amplitude by intensity level functions.

Conclusions

These results suggest that SS alters temporal integration and compressive nonlinearity, and that varying the stimulus rate of the ABR may prove to be a useful diagnostic tool in the study of hearing disorders that involve hyperexcitability.

Keywords: Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR), sodium salicylate, tinnitus, temporal integration, adaptation

Introduction

Systemic administration of sodium salicylate (SS) is known to provide an efficient and predictable method to induce general excitability in the central auditory system and peripheral hearing loss for both animal models and humans. It has also been shown to induce the tinnitus percept and has been used in the search for objective measures of how tinnitus affects auditory processing. In human patients, tinnitus is reported as a symptom and is therefore difficult to assess, especially when studying the effectiveness of new treatments, leading to the search for a robust objective test. SS-induced auditory perception causes no permanent morphological change to inner hair cell neurologic structures, and has several unique effects on both the central and peripheral auditory systems including a mechanism of action via arachidonic acid-mediated increase in NDMA channel opening (Cazals, 2000). Due to these unique mechanisms of altered auditory perception including the associated central hyperactivity, the continued investigation of the effects of SS on objective hearing measurements is valuable. This method of tinnitus induction has been widely used because of its reliability and its history in numerous behavioral tests of tinnitus using rodents (Yang et al., 2007; Turner & Parrish, 2008; Lobarinas et al., 2011; Lowe & Walton, 2015). The main objective of the present study was to assess the effect of SS-induced changes in hearing on temporal processing in the auditory nerve and midbrain of CBA/CaJ mice.

SS has acute ototoxic properties when administered in large doses, and human subjects have reported auditory changes including tinnitus, loss of absolute acoustic sensitivity, and alterations of perceived sounds (Cazals, 2000). In the peripheral system, salicylate has been found to suppress cochlear amplification by occupying the binding sites of the protein prestin (Liberman et al., 2002). This leads to a reduction in hair cell electromotility and increased thresholds throughout the hearing range, as well as deficits in temporal processing ability (Liberman, Gao et al., 2002; Deng et al., 2010). Other studies have demonstrated a salicylate-induced abolishment of distortion product otoacoustic emissions and have attributed resultant hearing loss to outer hair cell dysfunction (McFadden & Plattsmier, 1984; Long & Tubis, 1988; Kujawa et al., 1994; Zheng et al., 2000; Oliver et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Guitton et al., 2003). Increased spontaneous activity in the auditory nerve in response to salicylate has also been observed (Evans & Borerwe, 1982; Stypulkowski, 1990; Guitton, Caston et al., 2003). SS-induced changes to the central auditory system include permanent damage to the peripheral nervous system (Deng et al., 2013), alterations to firing rates in the medial geniculate (Basta et al., 2008), increased evoked responses to high intensity stimuli in the auditory cortex (Sun, Lu et al., 2009; Deng, Lu et al., 2010; Stolzberg et al., 2011; Stolzberg et al., 2012), increased spontaneous activity in the inferior colliculus (Jastreboff & Sasaki, 1986; Chen & Jastreboff, 1995; Manabe et al., 1997; Guitton, Caston et al., 2003), and depression of GABA signaling in the auditory midbrain and cortex (Moore & Moore, 1987; Sun, Lu et al., 2009; Stolzberg, Chrostowski et al., 2012). Based on these and other studies, it is believed that SS affects auditory pathways by causing propagation of abnormal signals through these pathways and their misinterpretation at higher processing centers (Guitton, Caston et al., 2003). While the specific mechanisms by which salicylate affects the auditory system are not entirely understood, its ability to reliably induce tinnitus and sensorineural hearing loss make it ideal for studies of auditory impairment (Sheppard, Hayes et al., 2014). The ABR provides a physiological measure of the caudal auditory pathway, specifically neural activity from the auditory nerve to the midbrain. The neural generators of the rodent ABR originate from structures caudal to the auditory midbrain. Specifically, peak 1 (P1) of the ABR can be attributed to the auditory nerve (Willott, 2001), while peak 4 (P4) is thought to originate from the lateral lemniscus (Zhou et al., 2006), and corresponds to wave V of the ABR in humans (Gu et al., 2012). Prior studies have shown that salicylate reduces responses from the auditory nerve as measured by P1 and the compound action potential, while increasing evoked responses in the cochlear nucleus (P2 of the ABR), inferior colliculus, and higher auditory structures (Sun, Lu et al., 2009; Stolzberg, Chen et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013; Lowe & Walton, 2015). The ABR is also a key diagnostic tool in the audiological test battery that can be used to assess both peripheral sensitivity and retrocochlear function, and has been implicated as a potential diagnostic indicator of tinnitus (Gu, Herrmann et al., 2012; Lowe & Walton, 2015).

Auditory thresholds have been shown to improve when longer duration test stimuli are used, a process referred to as temporal integration (Plack & Skeels, 2007; Sheppard, Hayes et al., 2014). Temporal integration is affected by tinnitus in human subjects, causing shorter duration signals or faster presentation rates to be more detectable than in non-tinnitus subjects (Pedersen, 1974; McFadden & Plattsmier, 1983; McFadden et al., 1984). However, the effects of increasing stimulus rate using stimuli that span the audiometric range on ABR thresholds before and after the induction of tinnitus or administration of SS has, to our knowledge, never been assessed. In addition, the ABR can measure gross indices of temporal resolution in the periphery and brainstem by increasing the stimulus rate or through the use of forward masking paradigms (Burkard, 1994; Walton et al., 1999). In humans, bats, rats, and gerbils, it has been found that an increase in the stimulus presentation rate alters the response waveform by decreasing peak amplitude and increasing latency (Suzuki et al., 1986; Donaldson & Rubel, 1990; Overbeck & Church, 1992; Chen & Jen, 1994). However, studies that have varied stimulus rate and measured ABR thresholds have produced variable results. These thresholds were unchanged following increases in stimulus rate in both gerbil and human studies (Donaldson & Rubel, 1990; Hyde et al., 2008), while responses from big brown bats andrats exhibited an increase in ABR threshold, which the authors attributed to the neuron’s inability to recover with a shorter inter-stimulus interval (Overbeck & Church, 1992; Chen & Jen, 1994). In a gerbil model, maturational changes were shown in the ABR with an increased stimulus rate, whereby neonates showed larger amplitude reductions in waves I and IV, and latency increases in wave IV compared to adult animals for higher rates (Donaldson & Rubel, 1990). Increases in stimulus rate have also been shown to aid in the diagnosis of neural pathology, such as the presence of acoustic neuromas and suspected multiple sclerosis (Pratt et al., 1981; Jacobson et al., 1987). In both cases, it was found that higher stimulus rates produced a smaller wave V in the presence of the pathology, and so were more efficient at detecting synaptic desynchronization or blockage in the central auditory pathway (Pratt, Ben-David et al., 1981; Jacobson, Murray et al., 1987).

The main objective of the present study was to investigate how SS alters temporal processing as assessed by increasing stimulus presentation rate on the ABR elicited by tone bursts of different frequencies. We focused on peak I and 4 of the mouse ABR in order to assess the effects of SS on temporal processing in the auditory nerve and midbrain of young CBA/CaJ mice. To evaluate the effects of SS-induced hearing changes on the ABR we measured shifts in ABR thresholds, peak amplitudes, and peak latencies as a function of presentation rate. While this study did not measure behavioral manifestations of the tinnitus percept, previous work with the same mouse strain, SS administration, and ABR method found significant correlations between behavioral gap detection deficits (an indicator of the presence of tinnitus) and changes in a hyperexcitability index of the ABR for 16 kHz stimuli (Lowe & Walton, 2015). Therefore, some discussion of the effects of SS induced tinnitus is included, as previous work has shown potential for the SS-induced changes to be related to this disorder.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Nine young adult CBA/CaJ mice (mixed sex), aged 2–4 months old (young adult), were used longitudinally as both control and treated animals. Mice were housed 3–4 per cage with littermates in Sealsafe Plus GM500 cages connected to an Aero70 Techniplast Smart Flow system (West Chester, PA). The animal housing cages were maintained under a 12-hour light cycle at constant temperature and humidity, and food pellets and water were made available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida (IACUC #M3847).

ABR Recordings

ABR recordings were collected following an identical procedure used in a previous study (Lowe & Walton, 2015), and details of the data collection are reproduced here for clarity. Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ketamine (120 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Subjects were monitored during each trial through respiration and whisker movement, and supplemental doses of ketamine were administered when needed. All experiments were conducted in less than two hours, a time period for which ketamine/xylazine was not shown to significantly alter ABR morphology in gerbils (Lima et al., 2012). Normothermia was maintained at 37°C using a feedback-controlled heating pad (Physitemp TCAT2-LV Controller, Clifton, NJ).

Stimuli and recordings were generated digitally and controlled using a TDT RZ6 Multi-I/O Processor and the accompanying BioSig/SigGen software. Acoustic signals were played through a multi-field (MF1) magnetic speaker (TDT, Alachua, FL) with a total harmonic distortion <= 1% from 1 kHz to 50 kHz, centered 0° azimuth in regards to the animal at a distance of 10 cm from the ear pinna. The signals were calibrated using a Larsen Davis preamplifier, model 2221, with a 1/4” microphone and a Larson Davis CAL200 Precision Acoustic Calibrator (PCB Piezotronics, Inc., Depew, NY).

ABR recordings were acquired using a TDT RA4LI low-impedance digital head stage and RA4PA Medusa preamp. The active (noninverting) electrode was inserted at the vertex, with the reference (inverting) electrode located below the left ear, and the ground electrode below the right ear. The responses were amplified (20x), filtered (100 Hz - 5 kHz), and averaged using BioSig software and the System III hardware (TDT) data-acquisition system. A total of 256 responses were replicated and averaged for each waveform, and muscle artifacts exceeding 7 uV were rejected from the averaged response. All recordings took place in a soundproof booth lined with echo-attenuating acoustic foam.

Rate-dependent ABR threshold determination: baseline and SS

The purpose of this study was to determine how increasing stimulus rate affects both ABR threshold and response morphology following SS administration. Measurements were taken for both pre-SS and post-SS conditions, to determine the effect of rate on the ABR detection of central processing. Each mouse was tested using a high-resolution threshold protocol for 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32 kHz tone bursts. Tone bursts were presented at 80 dB and decreased in 5 dB steps at high intensities, and then the step size was reduced to 2–3 dB upon reaching lower intensities. The duration of the tone burst stimulation was 5 ms with a 1 ms slope. Each set of frequencies was tested at stimulus rates of 11, 31, 41, 51, and 81 per second, and ABR thresholds for each frequency were determined as the lowest intensity where a replicable wave was identified. The high-resolution (2–3 dB) steps were presented at higher intensities after SS treatment, as SS is known to raise rodent ABR thresholds (Sun, Lu et al., 2009; Liu & Chen, 2015; Lowe & Walton, 2015).

ABRs were acquired both before and 1–2 hours following i.p. injection of 250 mg/kg (concentration: 25 mg/ml 0.9% saline) SS, with each trial occurring on separate days. This timing is supported by Jastreboff et al. (1986), who found that following i.p. injection of SS, the maximum levels in blood serum occurred after 1.5 h, while the maximum levels in the perilymph and spinal fluid reached maximum levels within 2–4 hours (Jastreboff et al., 1986).

Data processing and statistical analysis

For each ABR, peak to trough amplitudes were measured, and latencies computed as the time elapsed between the stimulus onset and each analyzed peak. These measurements were automated using custom designed MATLAB software, visually confirmed by experimenter inspection, and corrected if necessary to ensure that the chosen peak was the last point before the negative slope, consistent with a fundamental method described by Hall (Hall, 2007). After analysis the duplicate recordings for each signal parameter were averaged for each animal before further analytical analysis within GraphPad Prism version 6.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). This analysis compared ABR thresholds for each overall waveform response, as well as the ABR threshold measurements for the individual peaks, P1 and P4. These data, along with amplitude and latency measurements, were compiled and compared for baseline and SS conditions. Grand averages were generated by cropping each waveform at the onset and offset of P1 and P5, respectively, and then aligning P1 of each waveform before averaging, with the thickness of the line indicating standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistics

The statistical analyses and graphs were created using GraphPad, with graphed results presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc multiple comparisons correction were used to evaluate the effects between intensity and presentation rate for both the baseline and SS conditions. These statistical comparisons were used to determine the influence of rate on peak amplitudes, and how this is altered by SS-induced central hyperactivity. Linear regression analysis was performed on the ABR threshold versus presentation rate data sets, to determine if slopes were significantly different from zero, an indication that presentation rate affects the threshold. For all tests, differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Presentation Rate Effects on ABR Threshold Pre- and Post-SS

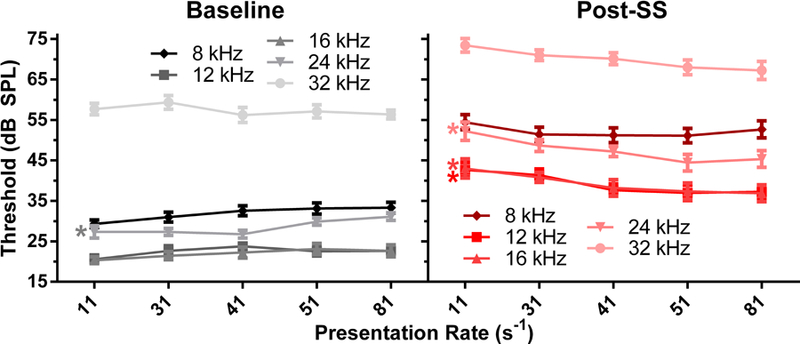

ABR thresholds were found to be stable as a function of rate (i.e. no significant effect) for baseline (pre-SS) measurements, which is consistent with previous findings in both gerbils and humans (Donaldson & Rubel, 1990; Hyde, Sininger et al., 2008). However, following SS administration, a significant effect of stimulus rate on ABR threshold was found for all stimuli frequencies except 8 kHz. Figure 1 shows the comparison between baseline and post-SS minimal response thresholds for all test frequencies. Following SS administration, a threshold shift of 20–25 dB was observed for the 11/sec rate, consistent with literature. As stimulus rate was increased, thresholds systematically decreased (improved) for the post-SS condition; there was a negative correlation, which was significant with linear regression for 12 kHz [p=0.0133], 16 kHz [p =0.0216], 24 kHz [p =0.0077], and 32 kHz [p =0.0079]. The ABR threshold improvements between 11 Hz and 81 Hz averaged 5–10 dB SPL.

Figure 1.

Baseline (left panel, black) and post-SS (right panel, red) thresholds as a function of stimulus rate, where darker colors indicate lower frequencies. The * denotes a significant difference in the slope from zero using linear regression. Thresholds following salicylate were significantly decreased with increasing presentation rate, while baseline measurements showed either no change or a rate-induced increase. Note that there is high overlap in the pre- and post-SS thresholds for 12 and 16 kHz.

Presentation Rate Effects on Amplitude Pre- and Post-SS

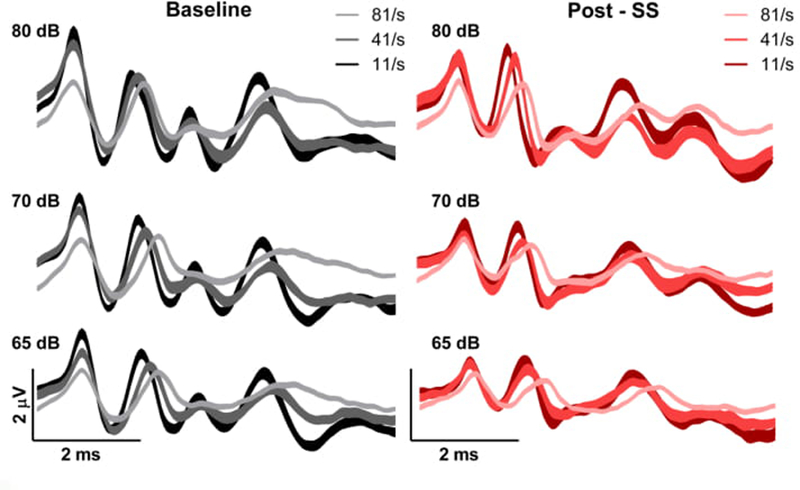

Grand averaged ABR waveforms (Figure 2) were computed for all mice in response to the 12 kHz stimuli, to allow for the visualization of changes in response morphology with manipulations of intensity (80, 70 and 60 dB SPL) and rate (11, 41 and 81/sec).

Figure 2.

Grand averages of the ABR waveforms in response to the 12 kHz frequency at high intensities for baseline (left panels, black) and post-SS (right panels, red). The darker colors indicate a lower stimulus presentation rate.

We found that there were distinct effects on each of the baseline ABR peaks that were dependent on both rate and intensity, with the largest effect of rate observed for P4. Increasing stimulus rate to 81/sec decreased P1 amplitude, independent of intensity, and following SS administration this effect was diminished. For P4, increases in stimulus rate prolonged latency and broadened P4 in the pre-SS condition, consistent with the idea that increased synaptic jitter can affect later components of the ABR. These effects were also observed post-SS. Finally, larger inter-peak latency changes were also seen as the stimulus intensity was lowered.

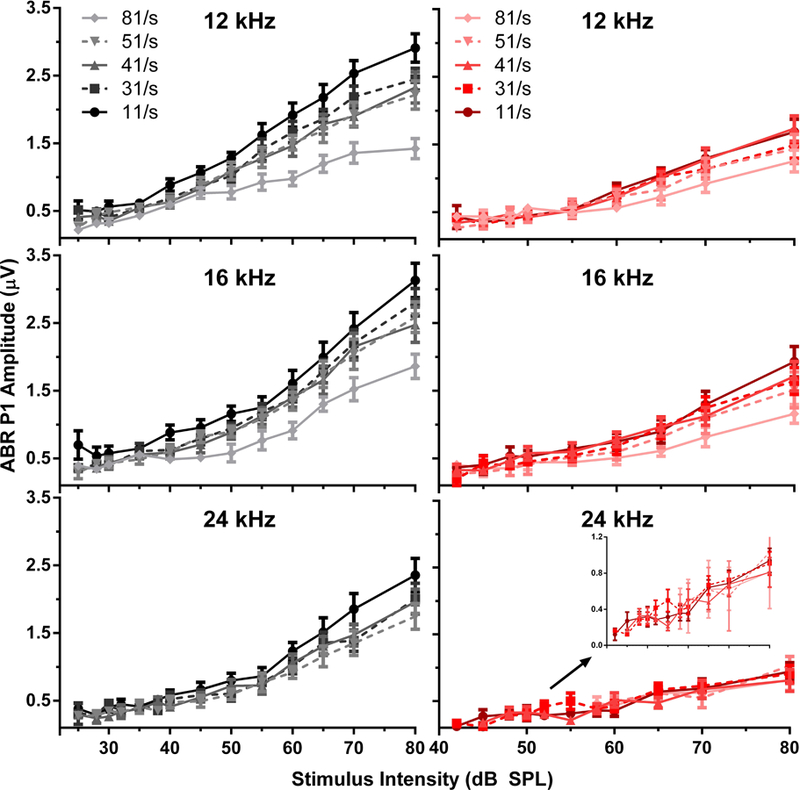

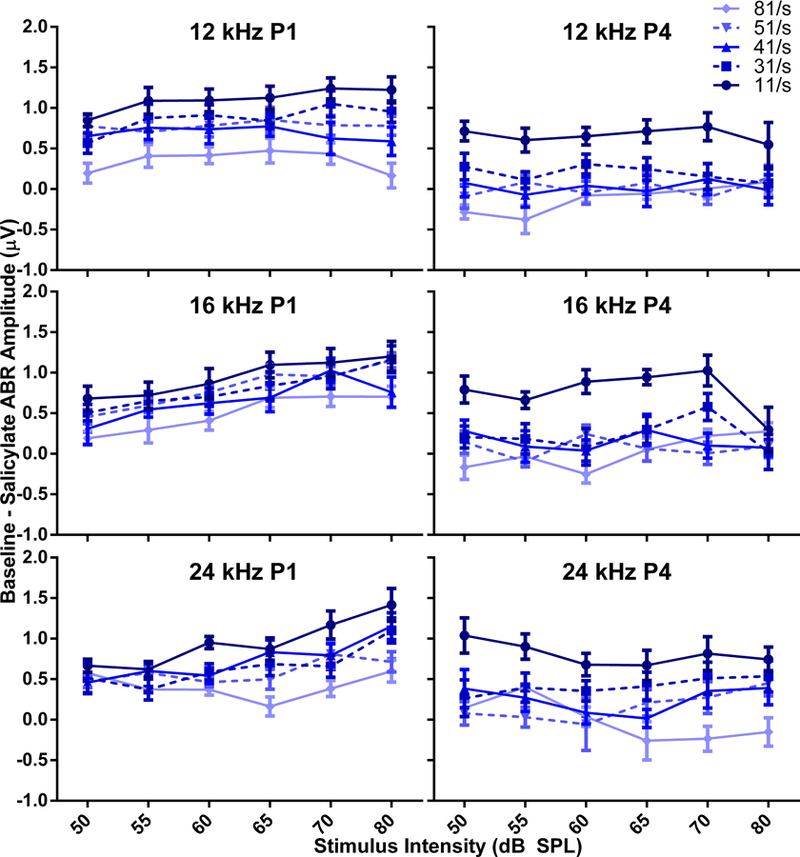

The effects of rate, intensity, and SS on the mean P1 amplitudes pre-SS (left column) and post-SS (right) are shown in Figure 3 and illustrate that the rate x amplitude x intensity functions are compressed following SS administration. Pre-SS, P1 amplitude decreased with increasing rates, and after SS administration, the higher amplitudes seen with lower rates were reduced to comparable levels of those seen at higher rates. The compression of the amplitude function with increasing rate was observed regardless of the stimulus frequency, consistent with a global disruption across the tonotopic axis.

Figure 3.

Peak 1 amplitudes for the baseline (left panels, black) and post-SS (right panels, red) conditions. The darker colors indicate a lower stimulus presentation rate. The inset in the bottom right panel depicts an enlarged view of the peak amplitudes for 24 kHz. Following SS-induced tinnitus, there was a reduced effect of stimulus rate in comparison to the baseline condition.

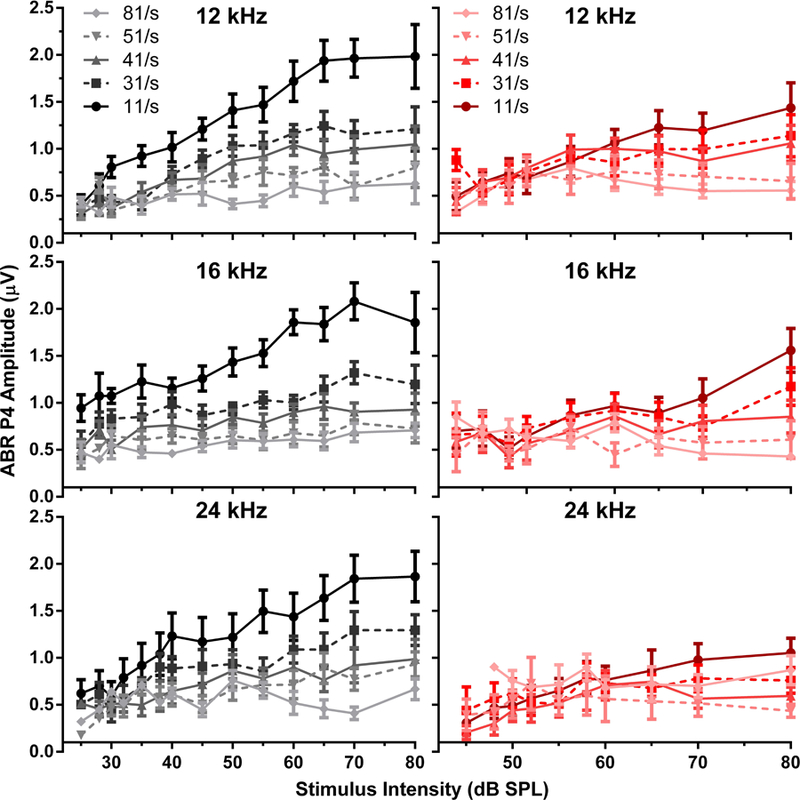

As shown in Figure 4, the effect of increasing rate on mean P4 amplitude also generated a systematic decrease in amplitude with increasing rate prior to SS, with the greatest rate effects occurring for highest intensity stimuli. P4 amplitudes from mice following SS also showed compression of peak amplitude, but the effect was smaller than that seen in P1. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of ANOVA and post hoc testing, and indicate significant differences in mean amplitudes for the higher intensities between rates at baseline versus post-SS. The 32 kHz frequency is not shown in these tables due to insufficient data following SS administration, this was the result of poor waveform morphology due to high thresholds which confounded peak analysis. The lowest intensity that was significantly different from 11/s is shown for each frequency and rate. These differences were significant for intensities between 50 and 80 dB for P1, and between 28 and 65 dB for P4, with an overall effect of rate observed at all tested frequencies. Post-SS, rate differences were only seen at higher intensities, between 70–80 dB for P1 and 65–80 dB for P4. The post-SS panels in Figures 3 and 4 illustrate this effect of rate following SS induction with increasing intensities, as compared to baseline – SS conditions induced a decrease in P1 and P4 amplitudes.

Figure 4.

Peak 4 amplitudes for the baseline (left panels, black) and post-SS (right panels, red) conditions. The darker colors indicate a lower stimulus presentation rate. Following SS-induced tinnitus, there was a reduced effect of stimulus rate in comparison to the baseline condition.

Table 1:

The ANOVA and post-hoc p-values comparing P1 mean amplitudes between the 11/s stimulus rate and higher presentation rates, where the intensity (in dB) in the post hoc cells indicates the lowest level where there was a significant difference. NS indicates no significance.

| Peak 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| 8 kHz | 12 kHz | 16 kHz | 24 kHz | |

| 31/s | 60 dB, p=0.0344 | 80 dB, p=0.0314 | NS | 70 dB, p=0.0198 |

| 41/s | 55 dB, p=0.0330 | 60 dB, p=0.0357 | 80 dB, p=0.0036 | NS |

| 51/s | 60 dB, p=0.0095 | 65 dB, p=0.0201 | 80 dB, p=0.0219 | 70 dB, p=0.0104 |

| 81/s | 50 dB, p=0.0062 | 50 dB, p=0.0155 | 50 dB, p=0.0127 | 60 dB, p=0.0056 |

| Overall ANOVA | F (4, 241) = 66.50 | F (4, 383) = 31.98 | F (4, 391) = 18.39 | F (4, 374) = 7.496 |

| p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Post-SS | ||||

| 31/s | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 41/s | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 51/s | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 81/s | 80 dB, p=0.0158 | NS | 70 dB, p=0.0415 | NS |

| Overall ANOVA | F (4, 136) = 4.530 | NS | F (4, 240) = 2.742 | NS |

| p=0.0018 | p=0.0293 | |||

Table 2:

The ANOVA and post-hoc p-values between the 11/s stimulus rate and higher presentation rates are shown for the amplitude of peak 4, where the intensity (in dB) in the post hoc cells indicates the lowest level where there was a significant difference. NS indicates no significance.

| Peak 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| 8 kHz | 12 kHz | 16 kHz | 24 kHz | |

| 31/s | 65 dB, p=0.0010 | 60 dB, p=0.0169 | 50 dB, p=0.0167 | 55 dB, p=0.0155 |

| 41/s | 60 dB, p=0.0377 | 45 dB, p=0.0256 | 30 dB, p=0.0068 | 55 dB, p=0.0051 |

| 51/s | 60 dB, p=0.0271 | 40 dB, p=0.0422 | 28 dB, p=0.0161 | 40 dB, p=0.0183 |

| 81/s | 55 dB, p=0.0145 | 45 dB, p=0.0151 | 28 dB, p=0.0043 | 55 dB, p=0.0018 |

| Overall ANOVA | F (4, 193) = 42.10 | F (4, 356) = 48.77 | F (4, 378) = 86.41 | F (4, 363) = 24.12 |

| p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | |

| Post-SS | ||||

| 31/s | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 41/s | NS | NS | 80 dB, p=0.0020 | NS |

| 51/s | 80 dB, p=0.0199 | 80 dB, p=0.0012 | 80 dB, p<0.0001 | 80 dB, p=0.0208 |

| 81/s | 75 dB, p=0.0404 | 65 dB, p=0.0125 | 70 dB, p=0.0131 | NS |

| Overall ANOVA | F (4, 249) = 3.937 | F (4, 284) = 6.350 | F (4, 266) = 5.602 | F (4, 155) = 3.472 |

| p=0.0041 | p<0.0001 | p=0.0002 | p=0.0095 | |

Amplitude by rate functions were calculated as a percentage of the amplitude at 11/s for P1 and P4, and the data is shown in Table 3. The P4/P1 ratio would be equal to one if there was no effect of altering the stimulus rate, less than one if increases in rate reduced the amplitude, and greater than one if higher rates increased amplitudes. Two-way ANOVAs show comparisons for the mean amplitude proportions for rate and frequency. P4 ratios were significantly affected by treatment as compared to P1. This indicates that there is a greater effect of both rate and SS in the central versus peripheral portion of the auditory system. Figure 5 illustrates the difference in amplitude for each rate between baseline and treatment for P1 and P4.

Table 3:

Two-way ANOVA values are shown for comparisons between the mean amplitude ratio for 12, 16 and 24 kHz for each stimulus rate compared to the 11/s ABR presentation for peak 1 (top) and peak 4 (bottom) amplitudes.

| Peak 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 kHz | 16 kHz | 24 kHz | |

| 31/s | NS | NS | F (1, 75) = 17.78 |

| p < 0.0001 | |||

| 41/s | F (1, 82) = 22.32 | F (1, 79) = 7.533 | NS |

| p < 0.0001 | p = 0.0075 | ||

| 51/s | F (1, 81) = 7.697 | NS | F (1, 66) = 20.34 |

| p = 0.0069 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| 81/s | F (1, 80) = 36.61 | F (1, 79) = 6.515 | F (1, 57) = 7.252 |

| p < 0.0001 | p = 0.0126 | p = 0.0093 | |

| Peak 4 | |||

| 31/s | F (1, 84) = 13.10 | F (1, 84) = 13.34 | NS |

| p = 0.0005 | p = 0.0005 | ||

| 41/s | F (1, 84) = 20.57 | F (1, 84) = 11.85 | F (1, 72) = 14.79 |

| p < 0.0001 | p = 0.0009 | p = 0.0003 | |

| 51/s | F (1, 84) = 25.38 | F (1, 78) = 30.84 | F (1, 64) = 26.02 |

| p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | |

| 81/s | F (1, 74) = 35.43 | F (1, 76) = 20.08 | F (1, 54) = 11.52 |

| p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.0013 | |

Figure 5.

The amplitude difference between baseline and post-SS conditions for peaks 1 (left panels) and 4 (right panels), where darker colors indicate lower presentation rates. Both P1 and P4 were decreased in amplitude after treatment as compared to baseline values at all presentation rates.

Presentation Rate Effects on Latency Pre- and Post-SS

The latencies of both peaks were stable following SS administration, with only the 81 Hz rate demonstrating a slightly prolonged latency at baseline and post-SS for P4. The overall effect of rate on latencies in the baseline responses indicated a general prolongation in latency when stimuli presentation rates were increased, especially at the lower intensities. These results were analyzed via 2-way ANOVAs comparing pre-SS and post-SS effects on peak latency. For P1 latency, significant differences were found at baseline for 12 kHz [F (4, 393) = 14.86, p < 0.0001], 16 kHz [F (4, 391) = 6.770, p < 0.0001], and 24 kHz [F (4, 374) = 18.07, p < 0.0001], and following treatment for 12 kHz [F (4, 271) = 2.548, p = 0.0397] and 24 kHz [F (4, 158) = 7.024, p < 0.0001]. For P4 latency, significant differences were found at baseline for 8 kHz [F (4, 191) = 7.552, p < 0.0001] 12 kHz [F (4, 364) = 58.38, p < 0.0001], 16 kHz [F (4, 373) = 90.57, p < 0.0001], and 24 kHz [F (4, 261) = 46.34, p < 0.0001], and following treatment for 8 kHz [F (4, 264) = 32.81, p < 0.0001], 12 kHz [F (4, 237) = 21.26, p < 0.0001], 16 kHz [F (4, 250) = 38.92, p < 0.0001], and 24 kHz [F (4, 153) = 33.29, p < 0.0001]. Consistent with previous studies, increasing the stimulus rate altered ABR peak latencies in a systematic fashion, and latencies were not grossly altered by administration of SS.

In summary, increasing presentation rate was found to decrease waveform amplitude and increase peak latency. Prior to SS administration, presentation rate had no significant effect on the measured minimum threshold. Following SS administration, a negative correlation between threshold and rate was observed, where an increased rate produced decreasing (improving) thresholds. SS was also seen to influence peak 4 amplitude around the tinnitus frequency, with a greater drop in amplitude observed at the lower rates with treatment when compared to the baseline measurements.

Discussion

Increasing stimulus rate following the administration of SS resulted in improved ABR thresholds and compression of the peak amplitude by level functions. The most interesting finding was that while ABR thresholds remained stable as stimulus rate increased for baseline measures, thresholds following SS improved by 5.7 to 6.9 dB, depending on stimulus frequency. This was due to a decrease in amplitude at the lower rates following SS as compared to baseline, leading to a compression of the rate by amplitude functions.

There were no measurable rate effects on ABR threshold at baseline testing, which agree with studies on gerbils showing no significant differences in ABR minimal response threshold with increases in rate (Donaldson & Rubel, 1990; Burkard, 1994). However, several human studies have exhibited a decrease in perceptual thresholds with increasing rate for short duration stimuli used to evoke the ABR (Zerlin & Naunton, 1975; Yost & Klein, 1979; Stapells et al., 1982), including a study by Yost and Klein where they observed a ~6 dB improvement in behavioral thresholds for 2 kHz tone bursts which was attributed to the shorter interval between stimuli presentation causing a temporal summation (Yost & Klein, 1979). Under SS conditions in the present study, a decrease in ABR threshold with increasing rate was observed and was significant with linear regression for all frequencies except for 8 kHz. The lack of an effect at 8 kHz is similar to other studies that have shown major changes in auditory testing only for frequencies near the induced tinnitus percept, which has been reported to be 16 kHz (Boettcher et al., 1989; Turner et al., 2006; Yang, Lobarinas et al., 2007; Lowe & Walton, 2015).

Alterations in temporal integration may be one possible mechanism behind the decrease in ABR threshold with increasing stimulus rate following SS administration, along with the elimination of the rate-induced decrements in P1 and P4 amplitude. A study of the ventral cochlear nucleus (CN) of mice has shown that the depolarization threshold has a specific time window in which depolarization can initiate an action potential, limiting the time window of temporal summation in several CN cell types (McGinley & Oertel, 2006). This depolarization window allows for the individual perception of tone bursts with slower presentation rates using separate action potentials, and the summation of those presentation rates that exceed this window. As a key ignition center for the generation of tinnitus, the CN could influence upstream targets, such as the generators of P4 (Zhang & Kaltenbach, 1998; Kaltenbach, 2006). Therefore, a broader temporal integration window that could integrate neural activity would result in decreased thresholds with increased stimulus rate. In human subjects, tinnitus induced by SS has been shown to smooth the audiograms of hearing impaired listeners by only inducing hearing loss in regions unaffected by a pre-existing focal hearing loss, resulting in the improved hearing thresholds in tonotopic regions of pre-existing hearing loss (Myers et al., 1965; McFadden & Plattsmier, 1983). The slope of the temporal integration curve has been previously shown in humans to be reduced by tinnitus, causing shorter duration signals, or faster presentation rates, to be more detectable than in baseline conditions (Pedersen, 1974; McFadden & Plattsmier, 1983; McFadden, Plattsmier et al., 1984). Temporal gap detection was also found to be impaired as compared to normal listeners following SS administration and the concomitant sensorineural hearing loss (McFadden, Plattsmier et al., 1984). This could potentially be explained by a broadening of critical bands in the tinnitus condition, which would allow briefer stimuli to become more perceptible (Bonding, 1979; McFadden & Plattsmier, 1983). As the rate of presentation increased, animals with tinnitus would presumably show impaired temporal integration, causing individual stimuli presented at high rates to merge and be processed as a longer duration signal. This could lead to better signal detection and a lower ABR threshold in the treatment group of mice. This would also account for the lack of a reduction in peak amplitudes due to increasing stimulus rates following SS-induced hearing changes as compared to the baseline condition, where rate had a significant effect.

The observed ABR threshold decreases with increasing rate following SS could also be attributed to the known neural hyperactivity associated with tinnitus. SS has been shown to induce neural hyperactivity in the auditory central nervous system in humans, altering cortex tonotopy and resulting in enhanced mid-frequency neural activity at the tinnitus frequency region (Chen, Stolzberg et al., 2013). A trigger for this hyperactivity has been postulated to be the cochlear nucleus, where it has been reliably observed after tinnitus induction in both the dorsal (Kaltenbach et al., 2005) and ventral subdivisions (Gu, Herrmann et al., 2012). Several other studies have noted that dorsal cochlear nucleus activity levels might directly correlate to the presence and modulation of tinnitus. This is thought to be attributed to shifts in excitation and inhibition, which results in a synaptic plasticity that triggers local circuitry alterations and can then initiate hyperexcitability in neurons within the inferior colliculus (Kaltenbach et al., 2004; Kaltenbach, Zhang et al., 2005; Sun, Lu et al., 2009; Manzoor et al., 2013). Since SS is known to induce hearing loss and reductions in peripheral output, any maintenance of response amplitude from generators in the central auditory system is due to an increase in neuronal drive. This tinnitus-related hyperexcitability could contribute to trends seen in ABR threshold and amplitude in this study, due to the increases in driven rate amplifying responses to only the higher presentation rates under tinnitus conditions. Limitations to these conclusions could be that the observed changes may be due to other effects of SS-induced maladaptive changes, including hyperacusis. It is also important to note that low doses of SS have been shown to have a protective effect on ototoxicity, possibly through the influence on genes related to cell survival and salicylate’s function as a free radical scavenger (Sha et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2011). Therefore, it is possible that SS has diverging effects throughout the auditory system, even at high doses, which might play a role in these findings.

While determining the effect of stimulus rate on ABR measures is important for the standardization of ABR testing across laboratories, a secondary goal of this study was the determination of the effect of rate changes during SS-induced tinnitus, and the possible use of these altered rate paradigms in diagnosis and therapeutics testing. A study by Pratt previously found increased presentation rates to be useful in the diagnosis of acoustic tumors (Pratt, Ben-David et al., 1981), while Jacobsen illustrated their efficacy in the detection of multiple sclerosis (Jacobson, Murray et al., 1987). Our lab has also shown that the ABR may be useful as an objective measure of tinnitus (Lowe & Walton, 2015). The altered threshold following treatment supports this conclusion and suggests potential in the study of ABR threshold determination in tinnitus evaluation and pharmaceutical development. This study may also prove useful in other areas besides measuring the physiological correlates of tinnitus, such as in the phenotyping of mice. The ABR is currently being used for the identification of hearing impairments in mouse mutants (Hardisty-Hughes et al., 2010), and adding modifications in stimulus protocols such as changes in presentation rate may be useful in examining more specific auditory pathway degradations such as temporal processing deficits. These results point to the potential of additional experimentation to examine ABR-based diagnosis of various other neural impairments, to investigate whether rate variation could be a reliable general measure for brain abnormality.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. XiaoXia Zhu for her assistance with animal care and Dr. Adam Dziorny for contributions to the analysis software. We would also like to thank Dr. James Willott for his critique of the manuscript and Dr. Shannon Salvog for copy editing.

Funding Details

This work was supported by NIH Grants P01 AG009524 from the National Institute on Aging, USA.

Abbreviations

- ABR

Auditory brainstem response

- SS

Sodium salicylate

- CN

cochlear nucleus

- P1

peak 1

- P2

peak 2

- P4

peak 4

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

There are no actual or perceived conflicts for the authors of this manuscript with regards to funding source agencies, NIH or others, for the research reported in this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Basta D, Goetze R & Ernst A 2008. Effects of salicylate application on the spontaneous activity in brain slices of the mouse cochlear nucleus, medial geniculate body and primary auditory cortex. Hearing research, 240, 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA, Bancroft BR, Salvi RJ & Henderson D 1989. Effects of sodium salicylate on evoked-response measures of hearing. Hearing research, 42, 129–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonding P 1979. Critical bandwidth in patients with a hearing loss induced by salicylates. Audiology : official organ of the International Society of Audiology, 18, 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkard R 1994. Gerbil brain-stem auditory-evoked responses to maximum length sequences. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95, 2126–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazals Y 2000. Auditory sensori-neural alterations induced by salicylate. Progress in neurobiology, 62, 583–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazals Y 2000. Auditory sensori-neural alterations induced by salicylate. Progress in neurobiology, 62, 583–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G-D & Jastreboff PJ 1995. Salicylate-induced abnormal activity in the inferior colliculus of rats. Hearing research, 82, 158–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GD, Stolzberg D, Lobarinas E, Sun W, Ding D, et al. 2013. Salicylate-induced cochlear impairments, cortical hyperactivity and re-tuning, and tinnitus. Hearing research, 295, 100–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QC & Jen PH 1994. Pulse repetition rate increases the minimum threshold and latency of auditory neurons. Brain research, 654, 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang WG, Zha DJ, Qiu JH, Wang JL, et al. 2007. Aspirin attenuates gentamicin ototoxicity: from the laboratory to the clinic. Hearing research, 226, 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng A, Lu J & Sun W 2010. Temporal processing in inferior colliculus and auditory cortex affected by high doses of salicylate. Brain research, 1344, 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Ding D, Su J, Manohar S & Salvi R 2013. Salicylate selectively kills cochlear spiral ganglion neurons by paradoxically up-regulating superoxide. Neurotoxicity research, 24, 307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson GS & Rubel EW 1990. Effects of stimulus repetition rate on ABR threshold, amplitude and latency in neonatal and adult Mongolian gerbils. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, 77, 458–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E & Borerwe T 1982. Ototoxic effects of salicylates on the responses of single cochlear nerve fibres and on cochlear potentials. British journal of audiology, 16, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JW, Herrmann BS, Levine RA & Melcher JR 2012. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials suggest a role for the ventral cochlear nucleus in tinnitus. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO, 13, 819–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton MJ, Caston J, Ruel J, Johnson RM, Pujol R, et al. 2003. Salicylate induces tinnitus through activation of cochlear NMDA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 3944–3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW 2007. New handbook of auditory evoked responses: Boston: : Pearson, c2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hardisty-Hughes RE, Parker A & Brown SD 2010. A hearing and vestibular phenotyping pipeline to identify mouse mutants with hearing impairment. Nature protocols, 5, 177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M, Sininger Y & Don M 2008. Objective Detection and Analysis of Auditory Brainstem Response: An Historical Perspective. Seminars in Hearing, 19, 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JT, Murray TJ & Deppe U 1987. The effects of ABR stimulus repetition rate in multiple sclerosis. Ear and hearing, 8, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Hansen R, Sasaki PG & Sasaki CT 1986. Differential uptake of salicylate in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and perilymph. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery, 112, 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ & Sasaki CT 1986. Salicylate‐induced changes in spontaneous activity of single units in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 80, 1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA 2006. The dorsal cochlear nucleus as a participant in the auditory, attentional and emotional components of tinnitus. Hearing research, 216–217, 224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zacharek MA, Zhang J & Frederick S 2004. Activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of hamsters previously tested for tinnitus following intense tone exposure. Neuroscience letters, 355, 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J & Finlayson P 2005. Tinnitus as a plastic phenomenon and its possible neural underpinnings in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hearing research, 206, 200–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Glattke TJ, Fallon M & Bobbin RP 1994. A nicotinic-like receptor mediates suppression of distortion product otoacoustic emissions by contralateral sound. Hearing research, 74, 122–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jia S, et al. 2002. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature, 419, 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima JP, Ariga S, Velasco I & Schochat E 2012. Effect of the ketamine/xylazine anesthetic on the auditory brainstem response of adult gerbils. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas, 45, 1244–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XP & Chen L 2015. Forward acoustic masking enhances the auditory brainstem response in a diotic, but not dichotic, paradigm in salicylate-induced tinnitus. Hearing research, 323, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobarinas E, Dalby-Brown W, Stolzberg D, Mirza NR, Allman BL, et al. 2011. Effects of the potassium ion channel modulators BMS-204352 Maxipost and its R-enantiomer on salicylate-induced tinnitus in rats. Physiology & behavior, 104, 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GR & Tubis A 1988. Modification of spontaneous and evoked otoacoustic emissions and associated psychoacoustic microstructure by aspirin consumption. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 84, 1343–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe AS & Walton JP 2015. Alterations in peripheral and central components of the auditory brainstem response: a neural assay of tinnitus. PloS one, 10, e0117228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y, Yoshida S, Saito H & Oka H 1997. Effects of lidocaine on salicylate-induced discharge of neurons in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. Hearing research, 103, 192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor NF, Gao Y, Licari F & Kaltenbach JA 2013. Comparison and contrast of noise-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and inferior colliculus. Hearing research, 295, 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D & Plattsmier H 1984. Aspirin abolishes spontaneous oto‐acoustic emissions. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 76, 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D & Plattsmier HS 1983. Aspirin can potentiate the temporary hearing loss induced by intense sounds. Hearing research, 9, 295–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D, Plattsmier HS & Pasanen EG 1984. Aspirin-induced hearing loss as a model of sensorineural hearing loss. Hearing research, 16, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley MJ & Oertel D 2006. Rate thresholds determine the precision of temporal integration in principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hearing research, 216–217, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK & Moore RY 1987. Glutamic acid decarboxylase-like immunoreactivity in brainstem auditory nuclei of the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology, 260, 157–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Klinke R, Arnold W & Oestreicher E 2003. Auditory nerve fibre responses to salicylate revisited. Hearing research, 183, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers EN, Bernstein JM & Fostiropolous G 1965. Salicylate Ototoxicity. New England Journal of Medicine, 273, 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D, He DZ, Klöcker N, Ludwig J, Schulte U, et al. 2001. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science, 292, 2340–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeck GW & Church MW 1992. Effects of tone burst frequency and intensity on the auditory brainstem response (ABR) from albino and pigmented rats. Hearing research, 59, 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB 1974. Brief-tone audiometry in persons treated with salicylate. Audiology : official organ of the International Society of Audiology, 13, 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plack CJ & Skeels V 2007. Temporal integration and compression near absolute threshold in normal and impaired ears. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 122, 2236–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt H, Ben-David Y, Peled R, Podoshin L & Scharf B 1981. Auditory brain stem evoked potentials: clinical promise of increasing stimulus rate. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, 51, 80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puel J-L, Ruel J, Guitton M, Wang J & Pujol R 2002. The inner hair cell synaptic complex: physiology, pharmacology and new therapeutic strategies. Audiology and Neurotology, 7, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puel JL, d’Aldin C, Ruel J, Ladrech S & Pujol R 1997. Synaptic repair mechanisms responsible for functional recovery in various cochlear pathologies. Acta oto-laryngologica, 117, 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puel JL, Ruel J, Guitton M, Wang J & Pujol R 2002. The inner hair cell synaptic complex: physiology, pharmacology and new therapeutic strategies. Audiology & neuro-otology, 7, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol R & Puel JL 1999. Excitotoxicity, synaptic repair, and functional recovery in the mammalian cochlea: a review of recent findings. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 884, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha SH, Qiu JH & Schacht J 2006. Aspirin to prevent gentamicin-induced hearing loss. The New England journal of medicine, 354, 1856–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard A, Hayes SH, Chen GD, Ralli M & Salvi R 2014. Review of salicylate-induced hearing loss, neurotoxicity, tinnitus and neuropathophysiology. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale, 34, 79–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapells DR, Picton TW & Smith AD 1982. Normal hearing thresholds for clicks. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 72, 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzberg D, Chen GD, Allman BL & Salvi RJ 2011. Salicylate-induced peripheral auditory changes and tonotopic reorganization of auditory cortex. Neuroscience, 180, 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzberg D, Chrostowski M, Salvi RJ & Allman BL 2012. Intracortical circuits amplify sound-evoked activity in primary auditory cortex following systemic injection of salicylate in the rat. Journal of neurophysiology, 108, 200–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stypulkowski PH 1990. Mechanisms of salicylate ototoxicity. Hearing research, 46, 113–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Lu J, Stolzberg D, Gray L, Deng A, et al. 2009. Salicylate increases the gain of the central auditory system. Neuroscience, 159, 325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kobayashi K & Takagi N 1986. Effects of stimulus repetition rate on slow and fast components of auditory brain-stem responses. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, 65, 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA, Parrish JL, Myers K, et al. 2006. Gap detection deficits in rats with tinnitus: a potential novel screening tool. Behavioral neuroscience, 120, 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG & Parrish J 2008. Gap detection methods for assessing salicylate-induced tinnitus and hyperacusis in rats. American journal of audiology, 17, S185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton J, Orlando M & Burkard R 1999. Auditory brainstem response forward-masking recovery functions in older humans with normal hearing. Hearing research, 127, 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF 2001. Handbook of Mouse Auditory Research: From Behavior to Molecular Biology: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Talaska AE & Schacht J 2011. New developments in aminoglycoside therapy and ototoxicity. Hearing research, 281, 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Lobarinas E, Zhang L, Turner J, Stolzberg D, et al. 2007. Salicylate induced tinnitus: behavioral measures and neural activity in auditory cortex of awake rats. Hearing research, 226, 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA & Klein AJ 1979. Thresholds of filtered transients. Audiology : official organ of the International Society of Audiology, 18, 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerlin S & Naunton RF 1975. Physical and auditory specifications of third-octave clicks. Audiology : official organ of the International Society of Audiology, 14, 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS & Kaltenbach JA 1998. Increases in spontaneous activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat following exposure to high-intensity sound. Neuroscience letters, 250, 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PC, Keleshian AM & Sachs F 2001. Voltage-induced membrane movement. Nature, 413, 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Shen W, He DZ, Long KB, Madison LD, et al. 2000. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature, 405, 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Jen PH, Seburn KL, Frankel WN & Zheng QY 2006. Auditory brainstem responses in 10 inbred strains of mice. Brain research, 1091, 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]