Abstract

The B cell survival cytokine BAFF has been linked with the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). BAFF binds distinct BAFF-family surface receptors, including the BAFF-R and transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI). Although originally characterized as a negative regulator of B cell activation, TACI signals are critical for class-switched autoantibody (autoAb) production in BAFF transgenic mice. Consistent with this finding, a subset of transitional splenic B cells upregulate surface TACI expression and contribute to BAFF-driven autoAb. In the current study, we interrogated the B cell signals required for transitional B cell TACI expression and Ab production. Surprisingly, despite established roles for dual BCR and TLR signals in autoAb production in SLE, signals downstream of these receptors exerted distinct impacts on transitional B cell TACI expression and autoAb titers. Whereas loss of BCR signals prevented transitional B cell TACI expression and resulted in loss of serum autoAb across all Ig isotypes, lack of TLR signals exerted a more limited impact restricted to autoAb class-switch recombination without altering transitional B cell TACI expression. Finally, in parallel with the protective effect of TACI deletion, loss of BAFF-R signaling also protected against BAFF-driven autoimmunity. Together, these findings highlight how multiple signaling pathways integrate to promote class-switched autoAb production by transitional B cells, events that likely impact the pathogenesis of SLE and other BAFF-dependent autoimmune diseases.

Increased serum levels of BAFF have been linked with the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). For example, independently-generated murine models of transgenic (Tg) BAFF overexpression exhibit systemic autoimmunity reminiscent of SLE (1–3). In addition, serum BAFF levels are elevated in a subset of lupus patients (4), and a genetic variant within the 3ʹ–untranslated region of TNFSF13B (encoding BAFF) confers an increased risk of SLE by increasing BAFF expression (5). Finally, belimumab, an anti-BAFF mAb, demonstrated clinical benefit in SLE, resulting in this medication becoming the first new lupus therapy to be approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in the modern era (6, 7).

Despite established links between increased BAFF and lupus pathogenesis, the mechanisms underlying autoantibody (autoAb) production in the setting of excess BAFF remain incompletely defined. BAFF and the related TNF-family cytokine a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) impact B cell function by binding distinct B cell surface receptors, including the BAFF-R, transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI), and B cell maturation Ag (8). Soluble BAFF circulates as both homotrimers and 60-subunit multimers, which activate BAFF-R and TACI, respectively. During B cell development, coordinated positive and negative selection mechanisms integrate to establish a mature B cell repertoire that is diverse and yet exhibits reduced self-reactivity. In this context, excess BAFF promotes the survival and maturation of low-affinity self-reactive transitional B cells (9–11). Because BAFF-R is required for mature B cell survival (12), this model implicated BAFF-R as the primary receptor underlying BAFF-driven humoral autoimmunity. In contrast to this idea, independent groups, including our own, recently reported the unexpected finding that TACI deletion abrogates humoral autoimmunity in BAFF-Tg mice (13, 14).

Surprisingly, we also showed that developing transitional B cells are a target of TACI-dependent B cell activation and represent a previously unappreciated source of class-switched autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice (13). Specifically, whereas surface TACI (sTACI) expression is usually limited to mature B cells in wild-type (WT) animals, we observed a marked expansion of sTACI+ splenic B cells within the transitional type 1 (T1) (CD21loCD24hi) and transitional type 2 (T2) (CD21intCD24hi) gates in BAFF-Tg mice. Relative to sTACI− cells, this sTACI+ transitional subset exhibited an activated, proliferative phenotype and expressed both activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and T-bet, factors that, together, are required for class-switch recombination (CSR) to pathogenic IgG2a/c subclasses (15, 16). Using single-cell BCR cloning, we demonstrated that BAFF-Tg sTACI+ transitional B cells exhibit somatic hypermutation (SHM) and are enriched for self-reactivity. Finally, sTACI+ transitional B cells sorted from BAFF-Tg mice spontaneously produced class-switched autoAb ex vivo, implying that transitional B cells likely contribute to BAFF-driven autoAb production.

In the current study, we extend these findings to delineate the key B cell signals underlying this transitional B cell activation pathway. Whereas lack of B cell, Toll-like, and BAFF-R signals resulted in similar protection from immune complex (IC) glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice, these signaling pathways exerted distinct impacts on transitional B cell activation in high-BAFF settings. Together, our combined findings demonstrate that integrated signals are required for transitional B cell sTACI expression, activation, proliferation, and class-switched autoAb production during the pathogenesis of SLE.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (WT), BAFF-Tg (2), Taci−/− (17), Btk−/− (18), Myd88−/− (19), Tlr7−/− (20), Baffr−/− (21), CD21Cre mice (22), and ROSA-YFPfl/fl (23) mice, and relevant murine crosses were bred and maintained in the specific pathogen-free animal facility of Seattle Children’s Research Institute (Seattle, WA). All animal studies were conducted in accordance with Seattle Children’s Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols. Mice were sacrificed at 3–12 mo of age.

Abs

Anti-murine Abs include the following: B220 (RA3–6B2), CD138 (281–2), CD21 (7G6), CD24 (M1/69), CD80 (16–10A1), CD86 (GL1), CD5 (53–7.3), and Blimp1 (5E7) from BD Biosciences; CD19 (ID3), CD44 (IM7), CD21 (7E9), CD23 (B3B4), CD24 (M1/69), and TACI (1A1) from BioLegend; TACI (8F10–3), AA4.1 (AA4.1), and AID (mAID-2) from eBioscience; B220 (RA3–6B2) and IgM (II/41) from Life Technologies; TACI (166010) from R&D Systems; and IgD (11–26) and goat anti-mouse IgM-, IgG-, IgG2c-conjugated, unlabeled, or isotype from SouthernBiotech.

Irradiation reconstitution

Mice were irradiated with 500 cGy of radiation prior to analysis of B cell compartment reconstitution.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting, and in vitro B cell culture

Single-cell splenocytes or peritoneal cells were stained with fluorescence-labeled Abs for flow cytometry analysis, intracellular staining was performed using the BD CytoFix/CytoPerm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD Biosciences), and intranuclear staining was performed using the True-Nuclear Fix/Perm Buffer Set (BioLegend). Data were collected on a LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Cell sorting was performed on CD43 magnetic bead–depleted (Miltenyi Biotec) splenocytes from CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl and CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl.BAFF-Tg mice using a FACSAria II sorter (BD Biosciences) with the following sort gates: follicular mature (FM), CD19+CD24intCD21int. YFP+; marginal zone (MZ), CD19+CD21hiCD23lo.YFP+; and T1 (CD19+CD24hiCD21lo.YFPneg), further subdivided as sTACIlo and sTACIhi. Sorted B cell subsets were cultured in RPMI 1640 at 1 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well plate at 37°C for 72 h prior to collection of supernatant for ELISA analysis.

In vitro stimulation of irradiation/reconstitution splenic transitional B cells

WT mice were irradiated with 500 cGy and allowed to reconstitute their B cell compartment for 13 d. Splenic B cells were isolated by CD43 depletion (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured for 24 h in RPMI 1640 at 0.5 × 106 cells/well in a 96-well plate at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with R848 (50 ng/ml), anti-mouse/IgM/F(abʹ)2 (10 µg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and recombinant murine BAFF (2 µg/ml; R&D Systems). RNA was isolated using an RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). TACI expression was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Super-mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the following primers: β2-microglobulin, 5ʹ-CTTCAGTCGTCAGCATGGCTCG-3ʹ (forward) and 5ʹ-GCAGTTCAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCC-3ʹ(reverse) and Tnfrsf13b, 5ʹ-ACCCCCAGTGTGCAGTAGAG-3ʹ (forward) and 5ʹ-GGAGGTGGAAGTCAGGTCAG-3ʹ (reverse).

4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl/Ficoll immunization

Mice were immunized i.p. with 100 µg of 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP)/Ficoll in PBS (Biosearch Technologies) and were sacrificed at either 3 or 5 d postimmunization. NP-specific B cells were identified with an NP/PE conjugate (Biosearch Technologies).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed by DAPI/Pyronin Y staining as previously described (12). Briefly, splenocytes were stained for surface Abs, then fixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde, and stained with DAPI and Pyronin Y prior to data acquisition.

Measurement of autoAb and ELISAs

Specific autoAb ELISAs were performed using 96-well Nunc-Immuno MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) precoated with Smith/ribonucleoprotein (Sm/RNP) (5 µg/ml, ATR01–10; Arotec Diagnostic). For total serum Abs, plates were precoated with goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG, or IgG2c Abs (1:500 dilution; SouthernBiotech). Plates were blocked with 1% BSA prior to incubation with diluted serum. Specific Abs were detected using goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG, or IgG2c/HRP (1:2000 dilution; SouthernBiotech), and peroxidase reactions were developed using OptEIA TMB substrate (BD Biosciences). Absorbance at 450 nm was read using a SpectraMax 190 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices), and data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

Quantification of albuminuria and serum blood urea nitrogen

Murine urine albumin was measured by indirect competitive ELISA (Albuwell M., Exocell), and urine creatinine was measured using an enzymatic test kit (DZ072B-K; Diazyme Laboratories). Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was measured using a colorimetric method (DetectX Urea Nitrogen Detection kit; Arbor Assays). The protocols for all the kits were followed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Kidney histopathology

Mouse kidneys were frozen in OCT compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five-micrometer sections were fixed in −20°C acetone for 20 min, rehydrated in staining buffer (PBS, 1% goat serum, 1% BSA, and 0.1% Tween 20), and stained with IgG/FITC (Sigma-Aldrich), IgG2c/FITC (SouthernBiotech), or C3/FITC (MP Biomedicals). Images were acquired using a Leica DM6000 B microscope, Leica DFL360 FX camera, and Leica Application Suite X software. For glomerular IC quantification, images were obtained using a constant exposure and scored from 0 to 3 by two independent observers blinded to genotype. Paraffin-embedded sections of kidney were stained with Jones silver methenamine. Images were acquired using a Leica DM6000 B microscope, Leica DFL300 FX camera, and Leica Application Suite X software. Image analyses of glomerular volume and cell counts were conducted using ImageJ.

Statistical evaluation

The p values were calculated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test (GraphPad Software).

Results

Fate mapping demonstrates that TACI+ transitional B cells are a key source of class-switched autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice

The predominant B cell developmental subset contributing to BAFF-mediated autoimmunity is controversial, with both splenic MZ B cells (8) and peritoneal B1b cells (24) hypothesized as the source of BAFF-driven autoAb. In contrast to this model, we reported data supporting the conclusion that transitional B cell subsets produce serum autoAb in high-BAFF settings (13). After generation in the bone marrow (BM), immature B cells enter the bloodstream and progress through transitional developmental stages in the spleen prior to differentiation into mature FM and MZ subsets. Within the splenic compartment, transitional B cells can be subdivided into CD21lo T1 and CD21mid T2 subsets, with both subpopulations expressing higher levels of CD93 (AA4.1) relative to mature B cells (25). Notably, the expanded sTACI+ subset within the T1 CD21loCD24hi and T2 CD21midCD24hi gates in BAFF-Tg mice lacked AA4.1 expression (13). In addition, mouse and human B cells downregulate CD21 expression after activation in autoimmune settings (26–28). Together, these findings raised the question as to whether sTACI+ CD21lo B cells in BAFF-Tg mice might compose a contaminating population of activated mature B cells falling within the transitional gate, rather than a bona fide transitional B cell population.

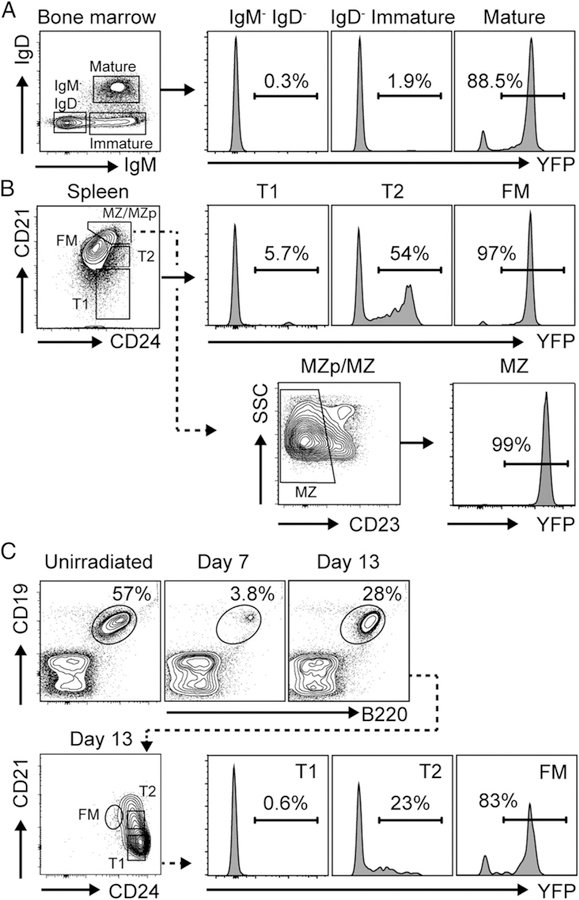

To address this question, we sought an alternate strategy to establish whether transitional B cells can directly produce class-switched autoAb in high-BAFF settings. We crossed CD21Cre mice (22) with the ROSA-YFPfl/fl reporter strain (23) to irreversibly fate-map developing B cells at the T2 stage. As predicted, whereas YFP expression was absent in immature BM B cells, the proportion of splenic B cells exhibiting YFP increased during the transition from T1 to T2 to mature B cell subsets. Specifically, <2% of pre–/pro– and immature BM B cells, ∼5% of T1 B cells, ∼50% of T2 B cells, and >97% of FM and MZ B cells exhibited YFP marking, in keeping with initiation of CD21 expression at the T2 stage (Fig. 1A, 1B) (29). Because peritoneal B cells circulate in the spleen (30), and B1b cells have been implicated as a source for BAFF-driven autoAb production (24), we confirmed that peritoneal B1b cells also express YFP and are thus distinct from splenic YFP−CD21loCD24hi T1 B cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Finally, to confirm that YFP marking in CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl reporter mice occurs as transitional B cells differentiate into the mature B cell compartment, we examined YFP expression in splenic B cell subsets following irradiation reconstitution. As predicted, sublethal irradiation (500 rad) depleted the splenic B cell compartment, which was repopulated by developing transitional B cells by day 13 postirradiation. Importantly, ∼0% of reconstituting T1 B cells expressed YFP, compared with ∼20% of T2 B cells and >80% of mature FM B cells (Fig. 1C). Thus, CD21cre expression faithfully marks developing B cells that have differentiated beyond the T1 stage, suggesting that this reporter strategy could be used to distinguish transitional B cells from activated mature B cell subsets in BAFF-Tg mice.

FIGURE 1.

Fate-mapping strategy to distinguish transitional versus mature B cells. (A) Left, Gating strategy to identify IgM−IgD− pre–/pro–, IgM+IgD− immature, and IgM+IgD+ mature B cells (gated on B220+) in BM of representative CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl mice. Right, YFP expression in indicated BM B cell subsets. (B) Splenic B cell developmental subset gating (top left; gated on CD19+B220+) and histogram showing YFP expression in indicated B cell subsets (top right). Lower panel, Gating of CD23lo MZ B cells within the CD21hiCD24hi MZ precursor (MZp)/MZ gate and histogram showing YFP expression in MZ B cells. (C) YFP expression in splenic B cells from CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl mice after irradiation/reconstitution. Upper left panels, FACS plot (gated on total splenocytes) showing splenic B cell depletion by day 7 postirradiation, with B cell reconstitution at day 13. Lower left panels, B cell developmental subsets following irradiation reconstitution (gated on CD19+B220+). Right, YFP expression in indicated B cell subsets on day 13 postirradiation. (A–C) Number indicates percentage within gate.

Next, we generated CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl.BAFF-Tg mice and compared YFP marking in TACIlo versus TACIhi transitional B cells in the setting of BAFF overexpression. Notably, the majority of sTACI+ T1 B cells in BAFF-Tg mice lacked YFP marking, consistent with an origin within an early transitional B cell subset. Moreover, the proportion of YFP-labeled cells in the BAFF-Tg T1 compartment was equivalent between sTACI+ and sTACI− subsets (Fig. 2A). We previously reported that relative to transitional B cells lacking TACI expression, sTACI+ T1 B cells in BAFF-Tg mice exhibit an activated surface phenotype (13). Importantly, among TACI-expressing T1 B cells in CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl.BAFF-Tg mice, YFP+ and YFP− transitional B cells exhibited a similar increase in cell size (forward scatter/side scatter) and CD44 and CD86 activation marker expression, relative to TACIneg counterparts (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Fate-mapping demonstrating that activated sTACI+CD21lo B cells in BAFF-Tg mice are transitional B cells. (A) YFP expression in sTACI+ versus sTACI− T1 B cells from CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl.BAFF-Tg mouse. Left, FACS plot (gated on CD19+ B cells) showing identification of CD21lo T1 B cells. Middle, Overlaid histograms showing sTACI expression in T1 B cells from WT (gray) and BAFF-Tg (line) CD21cre. ROSA-YFPfl/fl mice. Right, Histogram showing YFP labeling of sTACI+ (upper) versus sTACI− (lower) T1 B cells from representative CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl. BAFF-Tg mouse, confirming similar proportion of YFPneg cells in each T1 subset. Number indicates percentage within gate. (B) Histograms showing size/granularity (based on forward scatter [FSC] and side scatter [SSC]) and expression of surface activation markers (CD44 and CD86) on YFPneg sTACI+ (solid line) and YFPpos sTACI+ (dashed line) T1 B cells from representative CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl.BAFF-Tg mouse. Gray histogram indicates sTACI− T1 B cells. (C) Total IgM, IgG, and IgG2c in culture supernatants from sorted B cell subsets from WT and BAFF-Tg CD21cre.ROSA-YFPfl/fl reporter mice, with transitional subsets gated as YFP− and mature B cells (FM and MZ) gated as YFP+. Data pooled from two independent sorts. Error bars indicate SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test.

To definitively address whether transitional B cells spontaneously produce class-switched Abs in BAFF-Tg mice, we sorted YFP− sTACI+ and sTACI− T1 B cells, as well as YFP+ FM and MZ B cells, for quantification of ex vivo Ig production. Strikingly, in the absence of any additional stimulation, YFP− sTACI+ T1 B cells from BAFF-Tg mice spontaneously produced IgM, IgG, and IgG2c Abs ex vivo (Fig. 2C). Moreover, a subset of these IgG Abs bound the RNA-associated autoantigen Sm/RNP (Supplemental Fig. 1B). In summary, these data confirm that transitional B cells in BAFF-Tg mice upregulate sTACI expression prior to differentiation into the mature B cell compartment and directly contribute to spontaneous BAFF-driven autoAb production.

BCR signals promote transitional B cell TACI expression and autoAb production

Using the Nur77/GFP reporter strain (31) to measure BCR engagement in vivo, we previously observed a correlation between BCR signaling and sTACI expression on BAFF-Tg transitional B cells (13). In addition, sTACI+ transitional B cells in BAFF-Tg mice were enriched for self-reactive BCR specificities (13). These data implicated self-ligand–induced BCR signals in promoting sTACI expression on transitional B cells. However, this hypothesis was not formally tested. For this reason, we examined whether BCR engagement directly promotes transitional B cell TACI expression in vitro and in vivo. To obtain sufficient transitional B cells for in vitro analysis, we sublethally irradiated WT mice and purified splenic B cells at day 13 postirradiation, a time point at which the majority of reconstituting B cells are T1 and T2 B cells (Figs. 1C, 3A). As predicted, IgM cross-linking induced sTACI expression on transitional B cells and increased Tnfrsf13b (encoding TACI) transcript levels (Fig. 3A, 3B). In parallel, we examined whether physiologic BCR engagement in vivo promotes transitional TACI expression after immunization with the T cell–independent Ag NP/Ficoll. In keeping with TACI facilitating T cell–independent Ab responses (17), NP/Ficoll immunization resulted in an expansion of NP-specific T1 B cells exhibiting increased TACI expression. Notably, transitional B cell TACI upregulation was absent in mice deficient in the BCR signaling effector Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) (18), confirming that BCR signals directly regulate transitional B cell TACI expression in vivo (Fig. 3C, 3D).

FIGURE 3.

BCR signals promote transitional B cell activation and autoAb production. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing gating strategy for in vitro stimulation assays. Left panel, CD19+B220+ B cells following CD43 depletion of WT splenocytes at 13 d after sublethal irradiation. Middle panel, The majority of reconstituting B cells are CD21lo/midCD24hi T1/T2 B cells (gate drawn based on unirradiated WT controls [data not shown]). Right panel, Representative histogram of B cell sTACI expression with (black line), or without (gray shaded), anti-IgM (10 µg/ml) stimulation. Number indicates percentage within gate. (B) Percentage of sTACI+ B cells (left) and B cell Tnfrsf13b mRNA transcript expression (right) in media control (white) and anti-IgM–treated (black) transitional B cells. (C) Representative flow plots showing gating of CD19+B220+ B cells (left panel) and CD21loCD24hi T1 B cells (middle panel) after NP/Ficoll immunization. Right panel, Representative contour plots showing expansion of NP+TACI+ T1 B cells in WT, but not Btk−/−, mice at day 5 after NP/Ficoll immunization. Number indicates percentage within gate. (D) Percentage of NP+TACI+ B cells in T1 compartment in WT (black) and Btk−/− (gray) mice on indicated number of days after NP/Ficoll immunization. (E) sTACI expression in T1 B cells from WT, BAFF-Tg, and Btk−/−. BAFF-Tg mice. (F) Percentage of sTACI+ T1 B cells from indicated genotypes. (G) Overlaid flow plots showing side scatter (SSC), CD80, and CD86 expression in T1 B cells from WT (gray), BAFF-Tg (solid line), and Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg (dashed line) mice. (H and I) Representative FACS plots (gated on splenic T1 B cells) showing AID (H) and Blimp-1 (I) expression by sTACI+ T1 B cells from indicated genotypes. Number indicates percentage within gate. (J) Isotype-specific anti-Sm/RNP Ab from 12-wk-old WT (white), BAFF-Tg (black), and Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg (gray) mice. (B, D, F, and J) Error bars indicate SEM. (B) **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 by two-tailed unpaired two-tailed Student t test. (D, F, and J) *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test.

Finally, to test whether BCR signals impact transitional TACI expression during BAFF-driven autoimmunity, we crossed Btk−/− and BAFF-Tg mice. Strikingly, BTK deletion abrogated sTACI upregulation on transitional B cells in BAFF-Tg mice (Fig. 3E, 3F) despite limited impacts on the proportion of transitional B cells in Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg mice (Supplemental Fig. 2). In parallel with lower sTACI levels, T1 B cells from Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg mice also exhibited increased surface IgM expression [consistent with reduced BCR-dependent IgM downregulation following self-ligand engagement (31–33)] and were smaller with reduced CD80 and CD86 activation marker expression (Fig. 3G, Supplemental Fig. 2). Moreover, a subset of sTACI+ T1 B cells from BAFF-Tg mice express AID, which is required for CSR and BLIMP-1 and is necessary for plasma cell differentiation (Fig. 3H, 3I) (16, 34). In keeping with spontaneous class-switched autoAb production being primarily limited to sTACI+ transitional B cells in high-BAFF settings (13), this BAFF-dependent increase in sTACI, activation marker, and AID and BLIMP-1 expression was not observed in mature splenic B cells from BAFF-Tg mice (Supplemental Fig. 3). Strikingly, AID- and BLIMP-1–expressing transitional B cells were absent in Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg mice, findings that correlated with the loss of anti-Sm/RNP autoAb across all isotypes and subclasses (Fig. 3H–J). Although BCR-dependent signals may also facilitate autoAb formation by nontransitional B cell subsets, these data indicate that BCR-dependent signals drive sTACI expression by transitional B cells in vivo, resulting in AID/BLIMP-1 expression and BAFF-mediated, class-switched autoAb production.

Myd88 signals are required for class-switched autoAb formation but not TACI expression

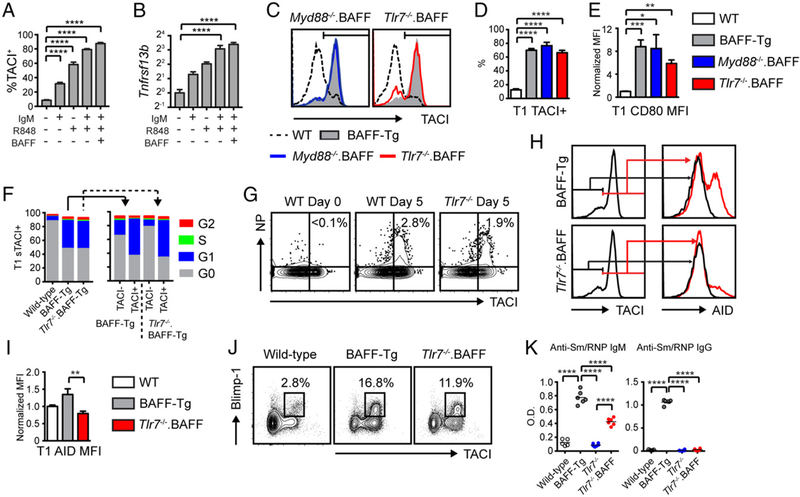

B cell–intrinsic Myd88 signals are required for systemic autoimmunity in BAFF-Tg mice (1), and TLR ligation promotes sTACI expression by peripheral B cells (35). Moreover, TACI directly interacts with Myd88 to facilitate B cell CSR (36), and we previously showed that stimulation of sorted sTACI+ T1 B cells from BAFF-Tg mice with the TLR7 agonist R848 enhances class-switched autoAb production ex vivo (13). Consistent with these data, R848 and BAFF synergized with anti-IgM stimulation to increase sTACI expression and Tnfrsf13b transcript expression on cultured transitional B cells in vitro (Fig. 4A, 4B). Based on these data, we predicted that Myd88 and/or Tlr7 deficiency on the BAFF-Tg background would both abrogate transitional B cell sTACI expression and recapitulate the phenotype of Taci−/−. BAFF-Tg mice. Surprisingly, neither Myd88 nor Tlr7 deletion exerted any impact on transitional B cell sTACI expression (Fig. 4C, 4D). Moreover, sTACI+ transitional B cells from Myd88−/−. BAFF-Tg and Tlr7−/−. BAFF-Tg mice exhibited an activated surface phenotype similar to BAFF-Tg animals (Fig. 4E, Supplemental Fig. 3). Our previous data demonstrated that sTACI+ transitional B cells in BAFF-Tg mice are cycling based on κ-deleting recombination excision circle analysis and Rag2/GFP dilution (13, 37, 38). Notably, an equivalent proportion of sTACI+ T1 B cells in BAFF-Tg and Tlr7−/−. BAFF-Tg animals were actively cycling based on cell cycle analysis using DAPI/Pyronin Y staining (Fig. 4F). Thus, although Myd88-dependent TLR7 signals promote TACI expression in vitro, TLR engagement can be redundant for transitional B cell TACI upregulation and proliferation in vivo. Consistent with these data, NP/Ficoll-immunized Tlr7−/− mice exhibited an equivalent expansion of sTACI+ NP–specific T1 B cells as WT controls, indicating that BCR engagement can be sufficient for transitional B cell TACI expression in vivo (Fig. 4G).

FIGURE 4.

TLR signals promote CSR, but are redundant for transitional B cell TACI expression. (A and B) Percentage of sTACI+ B cells (A) and B cell Tnfrsf13b mRNA transcript expression (B) in transitional B cells stimulated in vitro with indicated combinations of anti-IgM (10 µg/ml), R848 (50 ng/ml), and recombinant murine BAFF (2 µg/ml). (C) sTACI expression in T1 B cells from WT (dashed line), BAFF-Tg (gray), Myd88−/−.BAFF-Tg (blue), and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (D and E) Percentage of T1 B cells expressing sTACI (D) and T1 B cell CD80 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (normalized to WT T1 B cells) (E) in WT (white), BAFF-Tg (gray), Myd88−/−.BAFF-Tg (blue), and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (F) Left, Cell-cycle analysis of T1 B cells from WT, BAFF-Tg (solid line), and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg mice (dashed line). Right, Comparison of cell cycle in sTACI+ versus sTACI− T1 B cells in BAFF-Tg (solid line) and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg mice (dashed line). (G) Representative flow cytometry plots (gated on CD21loCD24hi splenic T1 B cells) showing expansion of NP+TACI+ T1 B cells in WT and Tlr7−/− mice at day 5 after NP/Ficoll immunization. Number indicates percentage within gate. (H) sTACI in T1 B cells (left panels) and intranuclear AID staining in sTACI+ (red line) versus sTACI− (black line) T1 B cells (middle panels) from representative BAFF-Tg (upper) and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg (lower) mice. (I) AID MFI (normalized to WT) in T1 B cells from WT (white), BAFF-Tg (gray), and Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (J) Representative FACS plots (gated on splenic T1 B cells) showing Blimp-1+sTACI+ cells from indicated genotypes. Number indicates percentage within gate. (K) Anti-Sm/RNP IgM and IgG Ab from 12-wk-old WT (white), BAFF-Tg (gray), Tlr7−/− (blue), and Tlr7−/−. BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (A, B, D, E, I, and K) Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test.

Among the Myd88-dependent TLRs, the endosomal receptors TLR7 and TLR9 facilitate the formation of class-switched autoAb targeting RNA- and DNA-associated autoantigens, respectively (39–41). Whereas previous studies have reported high-titer dsDNA autoAb in BAFF-Tg strains, we recently demonstrated that BAFF-Tg sera are primarily enriched for RNA-associated autoAb specificities with relatively low-titer DNA-reactive autoAb, as observed by high-stringency Crithidia luciliae kinetoplast staining (42). Based on these data, we examined whether TLR7 signals in transitional B cells impact their differentiation into Ab-secreting cells (ASCs). Notably, whereas the expression of AID was markedly reduced in TLR7-deficient T1 B cells, a prominent subset of sTACI+ BLIMP-1+ transitional B cells were identified in Tlr7−/−. BAFF-Tg mice (albeit reduced compared with BAFF-Tg controls) (Fig. 4H–J, Supplemental Fig. 3). These data suggested that B cell TLR signals might differentially regulate Ig CSR and ASC differentiation. Consistent with this idea, class-switched IgG and IgG subclass autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice were abrogated by TLR7 deletion. In contrast, although reduced compared with BAFF-Tg animals, Tlr7−/−. BAFF-Tg mice developed unswitched anti-Sm/RNP IgM autoAb that were markedly elevated compared with WT controls (Fig. 4K). Thus, whereas loss of TACI or BCR signals in Taci−/−.BAFF-Tg and Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg mice abrogated both unswitched IgM and class-switched IgG autoAb [Fig. 3J, (13)], deletion of TLR7 exerted a more limited impact on autoAb CSR.

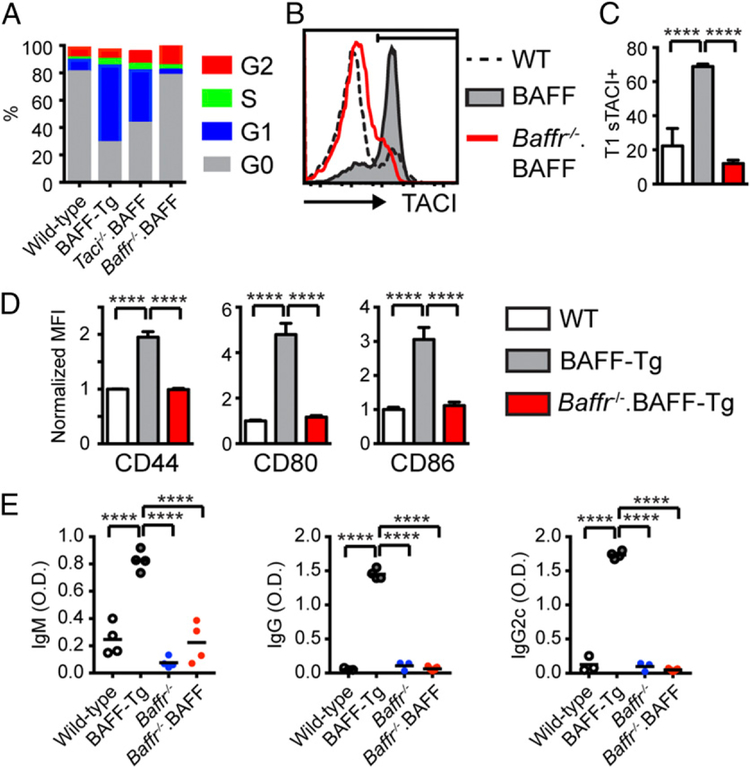

BAFF-R and TACI integrate to mediate transitional B cell activation and autoAb production

We also examined whether other BAFF-family receptors, in addition to TACI, impact the development of humoral autoimmunity in BAFF-Tg mice. Although BAFF-R–dependent B cell survival signals have been implicated in autoimmune pathogenesis by promoting the survival of low-affinity self-reactive B cells (9, 10), Baffr−/− mice exhibit a block in B cell development after the transitional stage (21). Thus, TACI-dependent activation of transitional subsets might result in production of pathogenic autoAb in a BAFF-R–independent manner. To test this hypothesis, we generated Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice. As predicted, BAFF-R deletion resulted in a block in B cell development at the transitional B cell stage (Supplemental Fig. 2). We first examined the impact of TACI or BAFF-R deletion on the in vivo proliferation of transitional B cells from BAFF-Tg mice. Notably, although TACI expression marks a subset of transitional B cells that have entered cell cycle in high-BAFF settings [Fig. 4F, (13)], an increased proportion of transitional B cells from Taci−/−.BAFF-Tg mice were proliferating compared with WT controls (Fig. 5A). In contrast, T1 cells from Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice remained in G0 and failed to enter the cell cycle. Thus, BAFF-R–dependent signals facilitate transitional B cell proliferation in high-BAFF settings, and, by inference, may contribute to autoAb production in BAFF-Tg mice. Consistent with this idea, T1 B cells in Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice failed to upregulate sTACI and exhibited reduced activation marker expression (Fig. 5B–D). Lack of transitional B cell TACI expression also correlated with the loss of anti-Sm/RNP autoAb across Ig isotypes and subclasses in Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg animals (Fig. 5E). In summary, although TACI signals are critical for autoAb formation in BAFF-Tg mice, BAFF-R activation exerts a complementary role in driving breaks in B cell tolerance.

FIGURE 5.

BAFF-R signals facilitate transitional B cell proliferation, activation, and autoAb production. (A) Cell-cycle analysis of T1 B cells from indicated genotypes. (B) sTACI expression in T1 B cells from representative WT (dashed line), BAFF-Tg (gray), and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (C) Percentage of sTACI+ T1 B cells for indicated genotypes. (D) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of surface activation markers CD44, CD80, and CD86 (normalized to WT) in T1 B cells from WT (white), BAFF-Tg (gray), and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (E) Isotype-specific anti-Sm/RNP Ab in 12-wk-old WT (white), BAFF-Tg (gray), Baffr−/− (blue), and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg (red) mice. (C–E) Error bars indicate SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test.

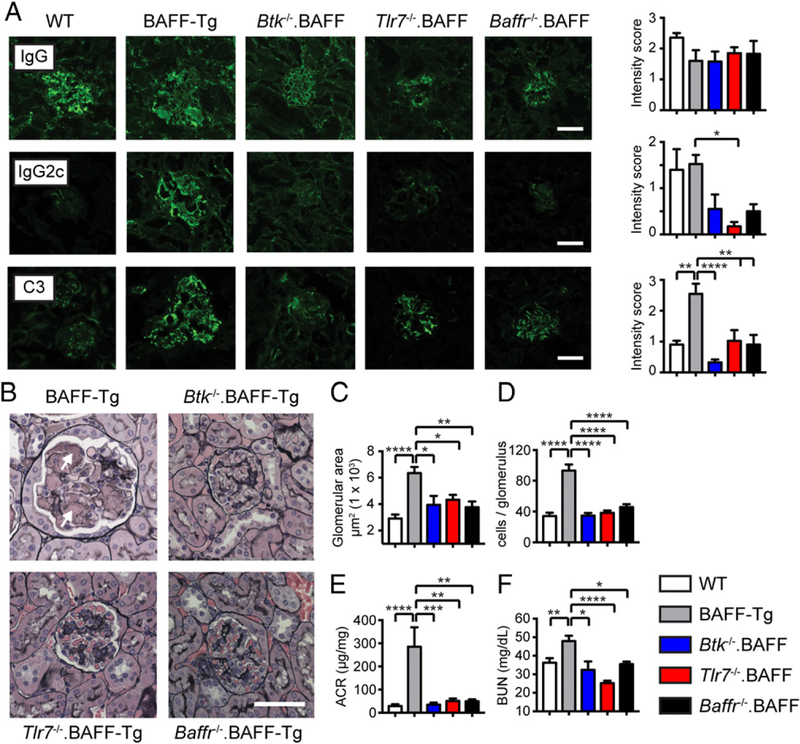

Integrated BCR, TLR7, and BAFF-R signals promote BAFF-driven lupus nephritis

Increased serum BAFF promotes the development of IC glomerulonephritis in murine Tg models (1, 14, 43) and has been linked with the pathogenesis of human lupus nephritis (44). We recently reported that TACI deletion in BAFF-Tg mice provides long-term protection from BAFF-driven nephritis by preventing the formation of endocapillary IC deposits within inflamed glomeruli, findings that correlated with loss of RNA-associated autoAb (42). Based on these data, we predicted that loss of BTK, TLR7, or BAFF-R signals would similarly protect against BAFF-mediated kidney disease. To test this idea, we aged cohorts of WT, BAFF-Tg, Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg, Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg, and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice for quantification of renal inflammation. Whereas glomerular IgG immunofluorescence staining did not distinguish between experimental groups, BAFF-Tg animals exhibited prominent deposition of IgG2c subclass Abs and C3 complement that was markedly reduced in Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg, Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg, and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice (Fig. 6A). In parallel with IC formation, aged BAFF-Tg mice developed severe membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, characterized by glomerular enlargement and cellular infiltration, as well as mesangiolysis, glomerular basement membrane duplication, and the accumulation of dense intra-capillary accumulations of acellular material (Fig. 6B, arrows). As predicted, these pathologic manifestations were absent in Btk−/−. BAFF-Tg, Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg, and Baffr−/−. BAFF-Tg mice, as assessed by computer-assisted quantification of mean glomerular size and cell count per glomerulus (Fig. 6B–D). Finally, because worsening proteinuria and renal dysfunction correlates with increased severity of renal inflammation in human lupus nephritis, we quantified urinary protein excretion and serum BUN levels in aged mice of each genotype. By 10 mo of age, BAFF-Tg animals exhibited marked albuminuria, which was associated with decreased renal function based on serum BUN levels. Importantly, Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg, Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg, and Baffr−/−. BAFF-Tg mice were protected from these clinical manifestations of renal injury, confirming that BTK, TLR7, and BAFF-R signals are each required to drive pathologic humoral autoimmunity in BAFF-Tg mice (Fig. 6E, 6F).

FIGURE 6.

BTK, TLR7, and BAFF-R signals promote progressive IC glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice. (A) Immunofluorescence (IF) staining for glomerular IgG (upper), IgG2c (middle), and C3 (lower). Left panels, Representative images. Right panels, Intensity of glomerular IF staining scored by observers blinded to genotype. Scale bar, 50 µM. (B) Renal histopathology showing marked mesangial expansion, mesangiolysis, and hypercellularity within glomeruli of representative 10-mo-old BAFF-Tg mouse (upper left panel; arrows denote endocapillary deposits). In contrast, glomerular changes were inapparent in age-matched Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg, Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg, and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice. Scale bar, 50 µM. (C and D) Mean glomerular size (C) and mean cell count per glomerulus (D). (E and F) Urine albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) (E) (microgram per milligram) and serum BUN (F). (A and C–F) Data from 10− to 12-mo-old WT (white), BAFF-Tg (red), Btk−/−.BAFF-Tg (black), Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg (blue), and Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg (green) mice (n ≥ 5 per genotype). Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey multiple comparison test.

Discussion

SLE is characterized by the near universal presence of class-switched autoAb targeting nuclear Ags. Although these autoAb likely contribute to the clinical manifestations of SLE, the immune signals underlying initial breaks in B cell tolerance and autoAb production have not been completely defined. In the current study, we describe a new B cell activation pathway in which increased serum BAFF levels directly promote class-switched autoAb production driven by integrated signals downstream of the BCR, the innate pattern-recognition receptor, TLR7 and its signaling effector Myd88, and the BAFF-family receptors BAFF-R and TACI.

Perhaps the most surprising feature of this integrated B cell activation pathway is that it can initiate at the transitional stage of B cell development. Because the surface markers used to define B cell developmental subset change with activation, it has been challenging to determine the specific B cell subset(s) responsible for BAFF-driven autoAb production in vivo. For example, MZ B cells were initially predicted to promote BAFF-driven SLE based on MZ expansion in BAFF-Tg mice, enrichment for autoreactive specificities in this subset, and the accumulation of MZ-like cells within inflamed salivary glands of BAFF-Tg animals (3, 8, 45, 46). However, neither genetic nor surgical splenectomy prevents BAFF-driven autoimmunity (47, 48), suggesting a redundant role for MZ B cells in BAFF-Tg autoAb production. Based, in part, on these observations, peritoneal B1b B cells were recently proposed as the primary B cell subset contributing to BAFF-mediated disease (24). In the current study, we demonstrate that transitional B cells represent a previously neglected source of class-switched autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice. By irreversibly labeling B cells that have expressed the complement receptor CD21 during transitional development, we were able to identify a subset of bona fide T1 B cells that directly contribute to the pool of BAFF-driven ASCs in autoimmunity. Although these data do not preclude roles for other B cell subsets to BAFF-dependent disease, our findings implicate transitional B cells as important contributors to lupus pathogenesis.

Together, our data support a model in which autoreactive B cells exiting the BM first engage self-ligand at the transitional stage. In the setting of increased serum BAFF, we predict that self-antigen–driven BCR signals promote sTACI expression, resulting in engagement of circulating multimeric BAFF complexes and autoAb production, a model consistent with known roles for TACI in driving T cell–independent plasma cell differentiation in both murine (49, 50) and human (51) B cells. Importantly, these events also require integration of signals downstream of the TLR-associated signaling adaptor Myd88 (1). Based on our recent findings that BAFF-Tg mice predominantly produce autoAb targeting RNA-associated, relative to DNA-reactive, specificities (42), we tested the role for TLR7 in driving transitional B cell TACI expression and class-switched autoAb production. Surprisingly, although TLR signals promote B cell TACI expression ex vivo [Fig. 4A, 4B, (1)], neither Myd88 nor Tlr7 deletion impacted sTACI expression on transitional B cells in BAFF-Tg mice. Rather, loss of TLR7 signals specifically abrogated B cell CSR, but exhibited only a minor impact on anti-Sm/RNP IgM autoAb production in Tlr7−/−.BAFF-Tg mice. In contrast, BCR receptor signals promote transitional B cell sTACI expression both in vitro and in vivo, and either Btk or Taci deletion blocked BAFF-driven autoAb across Ig isotypes [Fig. 3F, (13)]. Together, these data indicate that the signaling cascades downstream of BCR, TLR, and TACI ligation exert distinct impacts on autoreactive B cell activation responses in high-BAFF settings.

In addition to the critical role for TACI in BAFF-driven auto-immunity (13, 14), we also demonstrate that BAFF-R signals are necessary for class-switched autoAb production in high-BAFF settings. In this context, we predict that BAFF-R signals likely facilitate breaks in transitional B cell tolerance via parallel, but distinct, mechanisms. First, we predict that BAFF-R signals promote the survival and proliferation of BCR-engaged, autoreactive transitional B cells, expanding the total pool of sTACI+ transitional B cells, producing class-switched autoAb. Second, because BAFF promotes the survival of transitional B cells exhibiting low-affinity autoreactivity (9, 10), BAFF-R signals likely skew the transitional B cell repertoire, resulting in an increased proportion of cells engaging self-ligand and undergoing Btk-dependent sTACI expression. Notably, BAFF-Tg T1 B cells exhibit reduced surface IgM expression in keeping with Ag receptor engagement of self-antigens (31–33), whereas surface IgM is restored to WT levels in Baffr−/−.BAFF-Tg mice (Supplemental Fig. 2). Consistent with this model, using the Nur77/GFP reporter strain (31) crossed onto the BAFF-Tg background, we previously reported an increase in the percentage of T1 B cells exhibiting BCR activation in vivo (13). Although Baffr deletion results in a block in B cell development beyond the T2 stage (21), our model depends on BAFF-R signals impacting B cell survival earlier in development. Whereas initial studies suggested a limited impact on T1 B cell numbers in Baffr−/− mice, subsequent analyses indicated that BAFF-R is first expressed on a subset of immature BM B cells and that BAFF-R signals promote transitional B cell differentiation and survival in competitive settings (52). Thus, these observations lend support to our model wherein BAFF-R signals directly impact T1 B cell biology during autoimmunity.

Notably, integration of all these signaling cascades is required for production of pathogenic class-switched autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice. We recently showed that TACI deletion exerts long-term protection from IC glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice (42). Despite a prevailing model in which dsDNA autoAb drive lupus nephritis, the majority of autoAb in BAFF-Tg mice bound RNA-associated autoantigens, and TACI deletion specifically reduced these anti-RNA specificities. Notably, lack of RNA-associated autoAb correlated with a striking reduction in glomerular endocapillary IC deposits, findings that paralleled long-term protection from BAFF-driven proteinuria and renal dysfunction. In the current study, we extend these findings by showing that Btk, Tlr7, and Baffr deletion similarly protects against BAFF-dependent renal disease. Thus, despite distinct impacts on B cell activation, proliferation, CSR, and plasma cell differentiation, disruption of each signaling pathway (BCR, TACI, TLR7/MyD88, and BAFF-R) is sufficient to prevent the formation of pathogenic RNA-associated autoAb, resulting in loss of glomerular IC depositions and protection from glomerulonephritis. Taken together, these data highlight the importance of class-switched autoAb, including those targeting predominantly RNA-associated autoantigens, in driving glomerular IC formation and the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis.

Importantly, our data do not rule out additional contributions of other B cell subsets to autoAb production in BAFF-Tg mice. However, several lines of evidence indicate that transitional B cells contribute substantially to the autoAb repertoire in BAFF-Tg animals. First, excess BAFF promotes the marked increase in sTACI levels on a subset of activated transitional B cells without impacting TACI or activation marker expression on mature splenic B cells [Supplemental Fig. 3, (13)]. Second, the TACI+ transitional subpopulation in BAFF-Tg mice is enriched for autoreactivity and exhibits evidence of AID-mediated SHM, whereas SHM is rare in TACI+ mature B cell subsets (13). Finally, sorted TACI+ transitional B cells from BAFF-Tg mice, but not other splenic B cell developmental subsets, spontaneously produce class-switched autoAb ex vivo [Fig. 2C, (13)].

These findings raise the question as to why spontaneous autoAb production is not observed by TACI-expressing FM and MZ B cells in BAFF-Tg mice. One potential explanation is that the transitional B cells exhibit broad poly/autoreactivity, resulting in spontaneous activation of autoreactive B cells prior to maturation beyond the transitional stage. Consistent with this hypothesis, using the Nur77/GFP reporter strain (31) crossed onto the BAFF-Tg background, we previously observed higher in vivo BCR signaling by TACI+ transitional B cells relative to mature FM B cells. Alternatively, distinct mechanisms may prevent the dysregulated activation of autoreactive MZ B cells in high-BAFF settings, including Fas-dependent apoptosis following TACI engagement (53). Finally, BAFF-driven activation of autoreactive FM and MZ B cells may promote their differentiation into plasma cells, which lack the surface markers used to define their B cell developmental subset of origin.

Despite these caveats, our study highlights the importance of transitional B cells as a source for BAFF-driven autoAb and defines the cellular signals required for breaks in transitional B cell tolerance. Although studied in this article in the context of autoimmunity, this transitional B cell activation program likely evolved to resist infection. Because transitional B cells are known to undergo rapid activation following TLR stimulation (54), and infectious pathogens can promote local BAFF generation (55), we predict that TACI-dependent activation of transitional B cells promotes rapid, protective Ab responses during specific infectious challenges. However, because transitional B cells also exhibit greater self-reactivity compared with mature B cells (56), this transitional B cell activation pathway likely contributes to the pathogenesis of human SLE and other disorders characterized by increased serum BAFF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: DP3-DK111802 (to D.J.R.), R01AI071163 (to D.J.R.), R21AI123818 (to D.J.R.), and K08AI112993 (to S.W.J.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Children’s Guild Association Endowed Chair in Pediatric Immunology (to D.J.R.), the Benaroya Family Gift Fund (to D.J.R.), the American College of Rheumatology Rheumatology Research Foundation Career Development K Supplement (to S.W.J.), the Arthritis National Research Foundation Eng Tan Scholar Award (to S.W.J.), and by the Arnold Lee Smith Endowed Professorship for Research Faculty Development (to S.W.J.).

Abbreviations used in this article:

- AID

activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- ASC

Ab-secreting cell

- autoAb

autoantibody

- BM

bone marrow

- BTK

Bruton tyrosine kinase

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CSR

class-switch recombination

- FM

follicular mature

- IC

immune complex

- MZ

marginal zone

- NP

4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- Sm/RNP

Smith/ribonucleoprotein

- sTACI

surface TACI

- T1

transitional type 1

- T2

transitional type 2

- TACI

transmembrane activator and CAML interactor

- Tg

transgenic

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Groom JR, Fletcher CA, Walters SN, Grey ST, Watt SV, Sweet MJ, Smyth MJ, Mackay CR, and Mackay F 2007. BAFF and MyD88 signals promote a lupuslike disease independent of T cells. J. Exp. Med 204: 1959–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin AL, Duong B, Skog P, Aït-Azzouzene D, Greaves DR, Scott ML, and Nemazee D 2005. deltaBAFF, a splice isoform of BAFF, opposes full-length BAFF activity in vivo in transgenic mouse models. J. Immunol 175: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, Tschopp J, and Browning JL 1999. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J. Exp. Med 190: 1697–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stohl W, Metyas S, Tan SM, Cheema GS, Oamar B, Xu D, Roschke V, Wu Y, Baker KP, and Hilbert DM 2003. B lymphocyte stimulator over-expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: longitudinal observations. Arthritis Rheum 48: 3475–3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steri M, Orrù V, Idda ML, Pitzalis M, Pala M, Zara I, Sidore C, Faà V, Floris M, Deiana M, et al. 2017. Overexpression of the cytokine BAFF and autoimmunity risk. N. Engl. J. Med 376: 1615–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, Li EK, Thomas M, Kim HY, León MG, et al. ; BLISS-52 Study Group. 2011. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 377: 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzová D, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Schwarting A, Merrill JT, Chatham WW, et al. ; BLISS-76 Study Group. 2011. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 63: 3918–3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay F, and Schneider P 2009. Cracking the BAFF code. Nat. Rev. Immunol 9: 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, Amesbury M, Basten A, Mackay F, and Brink R 2004. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity 20: 785–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesley R, Xu Y, Kalled SL, Hess DM, Schwab SR, Shu HB, and Cyster JG 2004. Reduced competitiveness of autoantigen-engaged B cells due to increased dependence on BAFF. Immunity 20: 441–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hondowicz BD, Alexander ST, Quinn WJ III, Pagán AJ, Metzgar MH, Cancro MP, and Erikson J 2007. The role of BLyS/BLyS receptors in anti-chromatin B cell regulation. Int. Immunol 19: 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson JS, Bixler SA, Qian F, Vora K, Scott ML, Cachero TG, Hession C, Schneider P, Sizing ID, Mullen C, et al. 2001. BAFF-R, a newly identified TNF receptor that specifically interacts with BAFF. Science 293: 2108–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs HM, Thouvenel CD, Leach S, Arkatkar T, Metzler G, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Rawlings DJ, and Jackson SW 2016. Cutting edge: BAFF promotes autoantibody production via TACI-dependent activation of transitional B cells. J. Immunol 196: 3525–3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figgett WA, Deliyanti D, Fairfax KA, Quah PS, Wilkinson-Berka JL, and Mackay F 2015. Deleting the BAFF receptor TACI protects against systemic lupus erythematosus without extensive reduction of B cell numbers. J. Autoimmun 61: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerth AJ, Lin L, and Peng SL 2003. T-bet regulates T-independent IgG2a class switching. Int. Immunol 15: 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, and Honjo T 2000. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell 102: 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Bülow GU, van Deursen JM, and Bram RJ 2001. Regulation of the T-independent humoral response by TACI. Immunity 14: 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan WN, Alt FW, Gerstein RM, Malynn BA, Larsson I, Rathbun G, Davidson L, Müller S, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA, et al. 1995. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity 3: 283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou B, Reizis B, and DeFranco AL 2008. Toll-like receptors activate innate and adaptive immunity by using dendritic cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic mechanisms. Immunity 29: 272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, Iwasaki A, and Flavell RA 2004. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 5598–5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki Y, Casola S, Kutok JL, Rajewsky K, and Schmidt-Supprian M 2004. TNF family member B cell-activating factor (BAFF) receptor-dependent and-independent roles for BAFF in B cell physiology. J. Immunol 173: 2245–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraus M, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky N, and Rajewsky K 2004. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/beta heterodimer. Cell 117: 787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, and Costantini F 2001. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev. Biol 1: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairfax KA, Tsantikos E, Figgett WA, Vincent FB, Quah PS, LePage M, Hibbs ML, and Mackay F 2015. BAFF-driven autoimmunity requires CD19 expression. J. Autoimmun 62: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, and Hardy RR 2001. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J. Immunol 167: 6834–6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K, Kozono Y, Waldschmidt TJ, Berthiaume D, Quigg RJ, Baron A, and Holers VM 1997. Mouse complement receptors type 1 (CR1; CD35) and type 2 (CR2;CD21): expression on normal B cell subpopulations and decreased levels during the development of autoimmunity in MRL/lpr mice. J. Immunol 159: 1557–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandik-Nayak L, Seo SJ, Sokol C, Potts KM, Bui A, and Erikson J 1999. MRL-lpr/lpr mice exhibit a defect in maintaining developmental arrest and follicular exclusion of anti-double-stranded DNA B cells. J. Exp. Med 189: 1799–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson JG, Ratnoff WD, Schur PH, and Fearon DT 1986. Decreased expression of the C3b/C4b receptor (CR1) and the C3d receptor (CR2) on B lymphocytes and of CR1 on neutrophils of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 29: 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Andrews SF, Yu KO, Porcelli SA, and Rawlings DJ 2008. Characterization of a late transitional B cell population highly sensitive to BAFF-mediated homeostatic proliferation. J. Exp. Med 205: 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumgarth N 2011. The double life of a B-1 cell: self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nat. Rev. Immunol 11: 34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zikherman J, Parameswaran R, and Weiss A 2012. Endogenous antigen tunes the responsiveness of naive B cells but not T cells. Nature 489: 160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noviski M, Mueller JL, Satterthwaite A, Garrett-Sinha LA, Brombacher F, and Zikherman J 2018. IgM and IgD B cell receptors differentially respond to endogenous antigens and control B cell fate. Elife 7: e35074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodnow CCJ, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. 1988. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature 334: 676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tellier J, Shi W, Minnich M, Liao Y, Crawford S, Smyth GK, Kallies A, Busslinger M, and Nutt SL 2016. Blimp-1 controls plasma cell function through the regulation of immunoglobulin secretion and the unfolded protein response. Nat. Immunol 17: 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treml LS, Carlesso G, Hoek KL, Stadanlick JE, Kambayashi T, Bram RJ, Cancro MP, and Khan WN 2007. TLR stimulation modifies BLyS receptor expression in follicular and marginal zone B cells. J. Immunol 178: 7531–7539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He B, Santamaria R, Xu W, Cols M, Chen K, Puga I, Shan M, Xiong H, Bussel JB, Chiu A, et al. 2010. The transmembrane activator TACI triggers immunoglobulin class switching by activating B cells through the adaptor MyD88. Nat. Immunol 11: 836–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu W, Nagaoka H, Jankovic M, Misulovin Z, Suh H, Rolink A, Melchers F, Meffre E, and Nussenzweig MC 1999. Continued RAG expression in late stages of B cell development and no apparent re-induction after immunization. Nature 400: 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Zelm MC, Szczepanski T, van der Burg M, and van Dongen JJ 2007. Replication history of B lymphocytes reveals homeostatic proliferation and extensive antigen-induced B cell expansion. J. Exp. Med 204: 645–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, and Shlomchik MJ 2006. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity 25: 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rawlings DJ, Metzler G, Wray-Dutra M, and Jackson SW 2017. Altered B cell signalling in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 17: 421–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson SW, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Khim S, Schwartz MA, Li QZ, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Liggitt D, and Rawlings DJ 2014. Opposing impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 signals on autoantibody repertoire and systemic inflammation. J. Immunol 192: 4525–4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arkatkar T, Jacobs HM, Du SW, Li QZ, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Rawlings DJ, and Jackson SW 2018. TACI deletion protects against progressive murine lupus nephritis induced by BAFF overexpression. Kidney Int 94: 728–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCarthy DD, Kujawa J, Wilson C, Papandile A, Poreci U, Porfilio EA, Ward L, Lawson MA, Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, et al. 2011. Mice overexpressing BAFF develop a commensal flora-dependent, IgA-associated nephropathy. J. Clin. Invest 121: 3991–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dooley MA, Houssiau F, Aranow C, D’Cruz DP, Askanase A, Roth DA, Zhong ZJ, Cooper S, Freimuth WW, and Ginzler EM, BLISS-52 and −76 Study Groups. 2013. Effect of belimumab treatment on renal outcomes: results from the phase 3 belimumab clinical trials in patients with SLE. Lupus 22: 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groom J, Kalled SL, Cutler AH, Olson C, Woodcock SA, Schneider P, Tschopp J, Cachero TG, Batten M, Wheway J, et al. 2002. Association of BAFF/BLyS overexpression and altered B cell differentiation with Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Clin. Invest 109: 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopes-Carvalho T, and Kearney JF 2004. Development and selection of marginal zone B cells. Immunol. Rev 197: 192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fletcher CA, Sutherland AP, Groom JR, Batten ML, Ng LG, Gommerman J, and Mackay F 2006. Development of nephritis but not sialadenitis in autoimmune-prone BAFF transgenic mice lacking marginal zone B cells. Eur. J. Immunol 36: 2504–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fletcher CA, Groom JR, Woehl B, Leung H, Mackay C, and Mackay F 2011. Development of autoimmune nephritis in genetically asplenic and splenectomized BAFF transgenic mice. J. Autoimmun 36: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantchev GT, Cortesão CS, Rebrovich M, Cascalho M, and Bram RJ 2007. TACI is required for efficient plasma cell differentiation in response to T-independent type 2 antigens. J. Immunol 179: 2282–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozcan E, Garibyan L, Lee JJ, Bram RJ, Lam KP, and Geha RS 2009. Transmembrane activator, calcium modulator, and cyclophilin ligand interactor drives plasma cell differentiation in LPS-activated B cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 123: 1277–1286.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia-Carmona Y, Cols M, Ting AT, Radigan L, Yuk FJ, Zhang L, Cerutti A, and Cunningham-Rundles C 2015. Differential induction of plasma cells by isoforms of human TACI. Blood 125: 1749–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rowland SL, Leahy KF, Halverson R, Torres RM, and Pelanda R 2010. BAFF receptor signaling aids the differentiation of immature B cells into transitional B cells following tonic BCR signaling. J. Immunol 185: 4570–4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Figgett WA, Fairfax K, Vincent FB, Le Page MA, Katik I, Deliyanti D, Quah PS, Verma P, Grumont R, Gerondakis S, et al. 2013. The TACI receptor regulates T-cell-independent marginal zone B cell responses through innate activation-induced cell death. Immunity 39: 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueda Y, Liao D, Yang K, Patel A, and Kelsoe G 2007. T-independent activation-induced cytidine deaminase expression, class-switch recombination, and antibody production by immature/transitional 1 B cells. J. Immunol 178: 3593–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacLennan I, and Vinuesa C 2002. Dendritic cells, BAFF, and APRIL: innate players in adaptive antibody responses. Immunity 17: 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, and Nussenzweig MC 2003. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science 301: 1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.