ABSTRACT

Protein synthesis is tightly regulated, and its dysregulation can contribute to the pathology of various diseases, including cancer. Increased or selective translation of mRNAs can promote cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and tumor expansion. Translational control is one of the most important means for cells to quickly adapt to environmental stresses. Adaptive translation involves various alternative mechanisms of translation initiation. Upstream open reading frames (uORFs) serve as a major regulator of stress-responsive translational control. Since recent advances in omics technologies including ribo-seq have expanded our knowledge of translation, we discuss emerging mechanisms for uORF-mediated translation regulation and its impact on cancer cell biology. A better understanding of dysregulated translational control of uORFs in cancer would facilitate the development of new strategies for cancer therapy.

KEYWORDS: Translational control, translation initiation, upstream open reading frame, cell stress, cancer

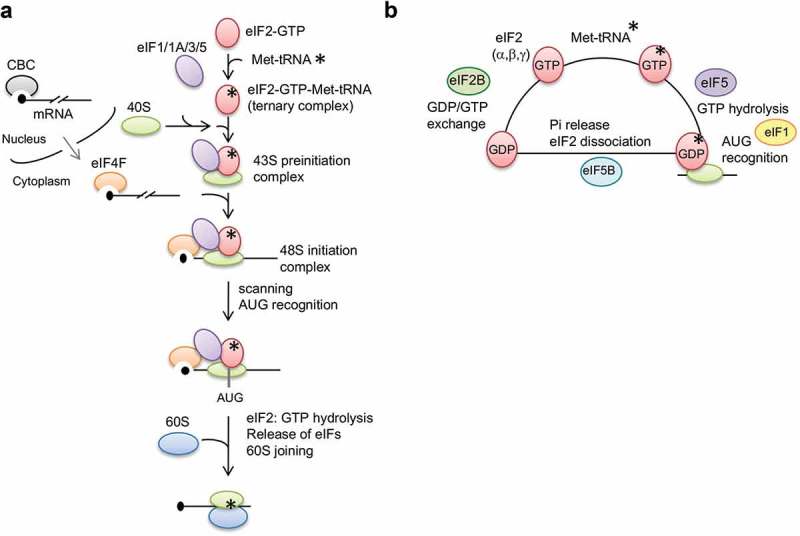

A brief overview of translation initiation

Translational control has a significant impact on cellular proteomes and is important for a myriad of eukaryotic cellular functions, particularly the regulation of cell proliferation and cellular homeostasis. Translation initiation is a rate-limiting and multi-step process involving a large number of initiation factors (Figure 1a). During transcription, the nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC), consisting of CBP80 and CBP20, binds the cap structure (m7GpppN) of precursor mRNAs and subsequently escorts the mature mRNAs from the nucleoplasm to the cytoplasm [1]. CBC-bound mRNA undergoes a pioneer round of translation, in which premature stop codon-containing transcripts can be identified and degraded by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) surveillance pathway [2]. Subsequently, the exchange of the CBC for eIF4E takes place through the binding of the nuclear transport receptor importin-β to the CBC-importin-α complex [1]. The cap-bound eIF4E, in conjunction with the RNA helicase eIF4A and scaffold protein eIF4G, forms the eIF4F complex. eIF4G circularizes the mRNA via its interaction with the cytoplasmic poly(A) binding protein (PABPC1) at the poly(A) tail. Meanwhile, the 40S ribosomal subunit associates with several initiation factors, including eIF1, eIF1A, eIF5 and the multicomponent eIF3 complex, followed by the joining of the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi ternary complex. Then, eIF2-GTP transfers Met-tRNAi to the 40S subunit [3,4]. The resulting 43S pre-initiation complex is subsequently loaded onto the 5ʹ end of eIF4F-bound mRNA to form the 48S initiation complex, which initiates the 5ʹ-to-3ʹ scanning of the 40S subunit toward the initiation codon. eIF4A unwinds cap-proximal regions of the mRNA to allow ribosomal scanning for the start codon. Upon recognition of the start codon, hydrolysis of eIF2-bound GTP induces dissociation of translation initiation factors and triggers the joining of the 60S subunit. eIF2 cycling between its GTP- and GDP-bound states is central to translation initiation and involves translation factors eIF2B and eIF5, which function with eIF2-GDP and the ternary complex respectively [5] (Figure 1b). eIF5B-GTP also promotes subunit joining, and GTP hydrolysis generates a translation elongation-competent 80S ribosome [6].

Figure 1.

Eukaryotic mRNA translation initiation and initiation factors.

(a) A schematic diagram of canonical translational initiation. The mature mRNA is remodeled from the CBC-bound to eIF4-bound form for steady state translation after being exported to the cytoplasm. eIF2-GTP and Met-tRNAi form the ternary complex (TC). Subsequently, the 40S ribosomal subunit joins the TC to form the 43S preinitation complex (PIC), which is assisted by eIF1/1A/3/5. The 43S PIC is loaded onto eIF4F-bound mRNA to form the 48S initiation complex, which initiates the scanning process. Recognition of AUG stimulates GTP hydrolysis, release of eIFs and joining of 60S for elongation. (b) A schematic diagram of TC cycling. eIF2 consisting of three subunits (α, β and γ) exhibits higher affinity for Met-tRNAi in the GTP-bound state than in the GDP-bound state. eIF5 stimulates the GTPase activity of eIF2 and eIF1 gates inorganic phosphate (Pi) release to ensure fidelity of AUG recognition. eIF5B accelerates the release of eIF2-GDP, which is then recycled to the GTP form by the nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B.

In addition to canonical translation initiation factors, many regulatory factors participate in translational control at the initiation step; some of them may act through cis-elements such as secondary structures or modified nucleotides in the 5ʹ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNAs [7]. In general, secondary structural elements suppress translation by preventing the loading or scanning of the pre-initiation complex [8]. Some of the DEAD/H-box RNA helicases, such as DDX3 and DHX9/29/36, function to resolve structured elements or G-quadruplexes in the 5ʹ UTR and hence facilitate 40S ribosome scanning [9–11]. A number of the trans-acting factors can promote the translation of IRES-bearing transcripts in a cap-independent manner under stress conditions, which inactivate eIF4E [12]. Besides structured elements, upstream open reading frames (uORFs), although a barrier to downstream translation in non-stressed cells, particularly provide a means to rapidly optimize protein production in response to stress [13–15]. Here we review recent advances in uORF-mediated translational control and its physiological and pathological implications in cancer.

Translation regulation and dysregulation in cancer

Increased global and gene-specific translation

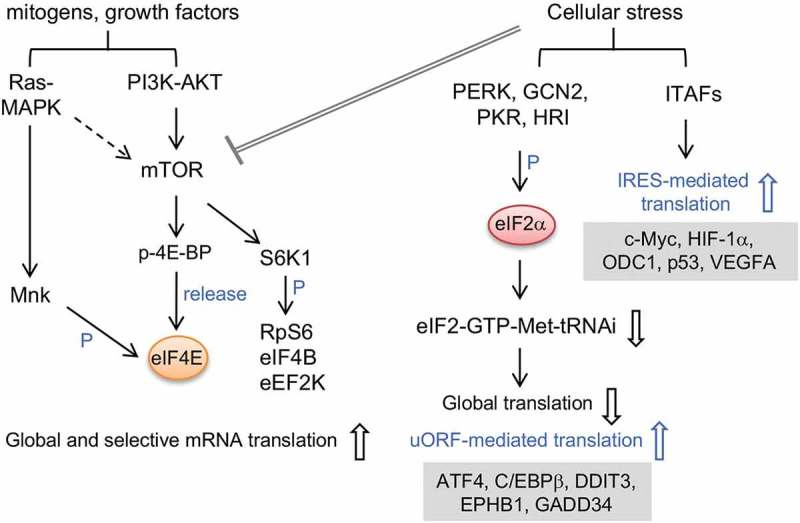

Protein synthesis is dynamically modulated in response to an ever-changing extracellular environment. Cancer cells have increased demands for protein synthesis to support rapid cell growth and division [7,16]. Mitogens or growth factors modulate translation initiation essentially via activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 and Ras-MAPK pathways, and in turn stimulate cap-dependent mRNA translation [17] (Figure 2). eIF4E is a rate-limiting factor for translation initiation and also a major target for translational control. Activated mTORC1 phosphorylates 4E-BP, the inhibitory partner of eIF4E, leading to 4E-BP dissociation from eIF4E and hence activation of translation. However, eIF4E also exhibits substrate specificity, by which it facilitates the translation of a cohort of oncogenic transcripts that govern cell proliferation or function in response to reactive oxygen species [18,19]. The cellular level of eIF4E is frequently elevated in human malignancies, supporting its oncogenic potential. Moreover, MNK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF4E also increases the translation of mRNAs encoding cell-survival and invasion factors, and thus it promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis [16,20]. mTORC1 also activates S6K1 (p70), which phosphorylates a number of translation factors including the ribosomal S6 protein (RpS6), eIF4B and eEF2K. Phosphorylated eIF4B enhances the processivity of eIF4A [21,22] and also promotes the translation of mRNAs related to cell proliferation and survival [23]. mTORC1 signaling augments the translation of a set of 5ʹ terminal oligopyrimidine tract-containing mRNAs encoding ribosomal proteins, translation factors, and a number of pre-invasion factors, indicating a role for mTORC1 in tumorigenesis [24,25]. In addition, the mTORC1/4E-BP pathway activates the translation of mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins and hence modulates energy homeostasis in cancer [26]. In conclusion, oncogenic signaling pathways enhance translation via multiple pathways.

Figure 2.

Signaling pathways that modulate translation.

Mitogens or growth factors activate the Ras-MAPK and/or mTOR pathways that target several translation factors or regulators, leading to translational activation of mRNAs involved in metabolism and cell growth. Cellular stress induces eIF2α phosphorylation, which reduces the availability of the ternary complex eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi and therefore suppresses global translation. On the other hand, eIF2α phosphorylation increases the translation of uORF-containing mRNAs that are required for metabolic adaptation. Under cell stress, ITAFs activate IRES-mediated translation to produce proteins for cell-fate decisions. Cell stress may also directly or indirectly inhibit mTOR, leading to translation suppression. Several genes that undergo uORF- or IRES-regulated translation under stressed conditions are listed. P: phosphorylation.

Cell stress-induced adaptive translation via different mechanisms

Cancer cells encounter various cellular stresses during tumorigenesis. In general, cell stress attenuates global translation and yet selectively activates alternative translation mechanisms. Cell stresses suppress translation via multiple pathways. mTORC1 is downregulated in response to cell stress such as prolonged hypoxia or nutrient limitation, so that 4E-BPs remain hypophosphorylated; this prevents eIF4F complex formation and reduces the rate of translation initiation [27,28]. In addition, several stress-response kinases induce phosphorylation of eIF2α on serine 51 [27,28]. Phosphorylated eIF2α inhibits the GTP/GDP exchange activity of eIF2B, thus preventing the recycling of eIF2. Consequently, the limited abundance of the ternary complex reduces global translation [29] (Figure 2). Cell stresses also compromise translation elongation by modulating the activity of the upstream kinases of eEF2K, resulting in phosphorylation and inactivation of the elongation factor eEF2 [28,30]. Nevertheless, translation of selective sets of mRNAs can be activated in stressed cells via different mechanisms (Figure 2 and see below).

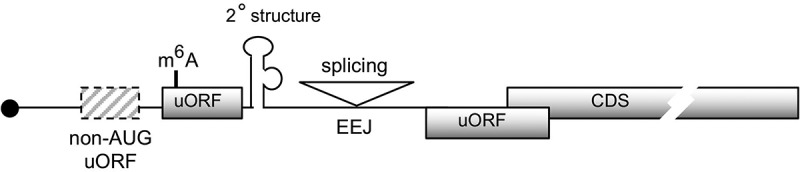

A variety of cis-elements are responsible for stress-regulated translation (Figure 3). One of the major mechanisms is IRES-driven translation. IRESs are structured elements in mRNAs of various viruses and also in cellular mRNAs encoding cell cycle, apoptotic and stress responsive factors [31,32]. IRES-interacting trans-acting factors (ITAFs) recruits the 40S ribosome subunit to these mRNAs and thus reduces their requirement for cap-dependent initiation. A decreased level of two ITAFs, namely translational control protein 80 (TCP80) and RNA helicase A, in malignant cells compromises IRES-mediated translation of p53 mRNA in response to DNA damage, leading to tumorigenesis [33]. uORFs are another major type of regulatory elements responsible for stress-regulated translation; the details will be discussed below. miRNAs can also modulate translation in response to nutrient conditions. For example, miR-122 suppresses the translation of the cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1 mRNA via binding to its 3ʹ UTR; under nutrient-limited conditions, the RNA binding protein HuR liberates miR-122 to enable translation [34]. Recent findings have unveiled the role of RNA modifications in stress-induced translation [35,36]. An N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in the 5ʹ UTR recruits the eIF3-40S ribosomal complex and hence renders translation cap-independent [35]. Moreover, YTH domain-containing m6A readers can increase the stability and translation of m6A-modified mRNAs [37]. The existence of multiple cis-regulatory elements in the 5ʹ UTR of certain mRNAs, such as CAT-1, implies complex and dynamic regulatory mechanisms of translation.

Figure 3.

cis-elements influence uORF-mediated translational control.

Graphic shows several cis-elements identified recently by systematic Ribo-seq and bioinformatics studies. Among these cis-elements, 2º (secondary) structures, m6A modification and exon-exon junction (EEJ) may impede ribosome scanning and hence facilitate recognition of uORF start codons. non-AUG uORFs exist, particularly with a higher prevalence in neuroblastoma transcripts. Initiation codon context affects the translation activity of uORF.

The impact of uORFs on translation

Recent bioinformatics studies revealed that ~50% of human transcripts have at least one uORF that fully resides within the 5ʹ UTR or partially overlaps with the main coding sequence (CDS) [13,38,39]. A recent genome-wide ribo-seq analysis revealed that uORFs, in a manner similar to miRNAs, act as potent regulators of both translation initiation and mRNA level [38,40]. uORF-mediated translational control primarily regulates stress-responsive gene expression, which is important for cell-fate determination under stress. Under normal cellular conditions, uORFs suppress the translation of the downstream main CDS by 30–80% [41]. Ribosomes may stall or dissociate from the mRNA during translation of uORFs [15,38,42]. The suppressive capacity of uORFs on CDS translation is influenced by several factors such as the number and length of the uORFs, the distance between a uORF and the downstream CDS, and uORF start codon and its context [43]. These uORF features may have combinatorial effects on CDS translation repressiveness [44]. Moreover, translation of uORFs may titrate translation initiation complexes, dissociate the ribosome from the mRNA following termination of the uORF, or downregulate uORF-containing mRNAs via NMD [15,38,42].

Under stress conditions, a low abundance of the eIF2·GTP-Met-tRNAMet ternary complex may allow scanning ribosomes to bypass inhibitory uORFs and reinitiate translation at the main CDS of certain stress-responsive transcripts such as ATF4 [45] (Figure 4a). Some uORFs may have a positive role in the translation of the downstream CDS. For example, uORF1 of yeast GCN4, the ATF4 homolog, promotes scanning and reinitiation of the 40S ribosomal subunit after translation termination by retaining eIF3a on ribosomes [46,47]. Moreover, uORFs may direct the selection of the initiation site of the main CDS to generate different protein isoforms [15]. This can be exemplified by CEBPB, which encodes three isoforms of the transcription factor C/EBPβ through differential utilization of translation initiation sites [48] (Figure 4b). The shortest isoform LIP counteracts tumor suppressive activities and promotes tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis [49]. The isoform ratio also determines additional biological outcomes, such as liver regeneration and immune response [50]. mTOR signaling or stress pathways enhances LIP production by promoting reinitiation at the downstream AUG [48,51]. Targeted disruption of the uORF AUG abolishes LIP expression, indicating that LIP expression depends on the presence of the uORF [52]. Thus, uORF-mediated translation may balance the expression of protein isoforms and hence determine cell fate in response to environmental changes.

Figure 4.

uORF-mediated translational control of ATF4 and CEBPB.

(a) In unstressed cells, plentiful eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNA allows uORF translation. Translation of the CDS-overlapping uORF causes ribosome dissociation from the ATF4 mRNA, thus reducing ATF4 production. Under stress conditions, the reduced availability of the ternary complex results in leaky scanning of the 40S ribosome subunit, and therefore bypasses the uORF and allows ATF4 translation. Additional positive or negative factors for ATF4 production described in the text are depicted in the boxes. (b) A uORF is involved in the translational control of the C/EBPβ isoforms. Without stimuli, lower mTOR activity reduces the activity of the translation machinery, resulting in leaky scanning over the uORF and thus producing the long isoform LAP. While mTOR is activated, enhanced translation activity directs reinitiation at the downstream AUG and thus produces the truncated isoform LIP. The positive regulators of LIP, CUGBP1 and SBDS, are not described in the text.

Dysregulation of uORF-mediated translational control may contribute to disease pathogenesis [13]. A recent report indicated that loss-of-uORF mutations induce translational activation of proto-oncogenes (see details below) [53]. Therefore, it is necessary to have a better understanding of uORF-mediated translational regulation.

Regulation of uORF-mediated translational control by cis-elements

Besides the aforementioned aspects of uORFs that have been reviewed elsewhere, here we discuss several recently discovered cis-elements that influence uORF translation efficiency and fidelity (Figure 3).

Primary sequence

Nucleotide sequences surrounding the initiation codon may influence the binding of translation initiation factors, ribosomal proteins or rRNAs and thus determine initiation efficiency [54–56]. A recent analysis of the impact of upstream translation initiation sites (uTISs) on translation efficiency and repressiveness indicated that the majority of uTIS contexts render weak translation of uORFs under selective pressure, indicating that uORFs in general act as regulatory rather than constitutive suppression elements. A uORF with a suboptimal context may benefit leaky scanning and hence allow main CDS translation when the activity of eIF2 is compromised during stress [13,15,38]. The observation that optimizing the AUG context of DDIT3 and GADD34 uORFs decreased CDS translation and stress response [57,58] supports the above assumption.

Secondary structures

Besides primary sequences, secondary structures in the 5ʹ UTR also influence initiation codon recognition [59]. Recent findings indicated that RNA helicases can modulate structure-assisted RNA translation (namely START) [60]. Inactivation of yeast Ded1, a homolog of mammalian DDX3, induces translation initiation at near-cognate initiation codons that are proximal to mRNA structure, suggesting that Ded1 prevents the use of RNA structure-assisted noncanonical initiation codons [61]. DDX3 is able to activate the translation of mRNAs that contain secondary structures or uORFs [62–65]. Therefore, whether there are structured elements located nearby DDX3-sensitive uORFs remains to be systematically determined. Genome-wide identification of uTIS and annotated translation initiation sites (aTIS) using a translation initiation sequencing analysis also revealed that active uTISs are frequently followed by stable RNA structures [66], suggesting that secondary structures promote the translation of uORFs, leading to CDS suppression. Another analysis, however, indicated that a secondary structure downstream of uTIS has the potential to directly suppress CDS translation [44]. Moreover, a G-quadruplex structure in the 5ʹ UTR also substantially suppresses translation [67]. A recent report showed that expansion of G4C2 repeats in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia-associated C9ORF72 may form G-quadruplexes. However, this type of G-quadruplex structure activates upstream noncanonical start codons, thus producing toxic dipeptide repeat-containing polypeptides [68]. Therefore, G-quadruplex structures may also influence uORF-mediated translation.

The RNA modification m6a

m6A is the most prevalent internal modification in mRNA. m6A in the 5ʹ UTR may modulate translation via different mechanisms. As described above, eIF3 or m6A readers such as YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 may directly bind m6A to promote translation. Additionally, m6A may enhance the usage of noncanonical start codons and uORF-mediated translational control [36,69,70]. More notably, m6A located downstream of uTISs, e.g., as in RNA secondary structures, may impede ribosome scanning and therefore promote the translation of uORFs [70]. Demethylation of m6A in the CDS-overlapping uORF of ATF4 is required for full activation of ATF4 translation under stressed conditions, which can occur in a phospho-eIF2α-independent manner (Figure 4a). Therefore, m6A in this uORF may restrict ATF4 production under normal conditions. Moreover, m6A may activate usage of noncanonical start codons during amino acid starvation [70]. Because cellular stresses may redistribute m6A in mRNAs [70–72], the physiological impact of m6A-modulated uORF translation remains as an interesting topic.

The exon-exon junction

Approximately one-third of human transcripts harbor introns in their 5ʹ UTRs [73]. Analysis of multiple Ribo-seq data recently revealed a negative effect of exon-exon junctions in 5ʹ UTRs (leader EEJs) on translation efficiency [74]. mRNAs with both leader EEJ and uTIS have not only the lowest efficiency of CDS translation but also higher ribosome occupancy in the 5ʹ UTR [74], indicating that leader EEJs may promote uORF translation. The multi-protein exon junction complex (EJC) is deposited upstream of EEJs upon splicing. Plausibly, the EJC in the 5ʹ UTR acts as an obstacle for scanning ribosomes and therefore enhances uTIS recognition. Alternatively, the EJC may recruit eIF3 or S6K1 to target SKAR to activate adjacent uTISs [75–77]. Recent findings revealed that the modification N1-methyladenosine (m1A) is enriched in the 5ʹ end of mRNAs, in particular downstream of the first EEJ [74,78]. Therefore, it remains an intriguing issue as to how m1A regulates the translation of uORFs and whether it functions coordinately with the EJC in translational control.

Non-AUG uORFs

Recent studies have unveiled a substantial number of non-AUG uORFs [79]. Non-AUG initiation codons appear to be predominant in uORFs of neuroblastoma transcripts and, intriguingly, exhibit translation efficiencies similar to AUG [80]. Met-tRNAiMet can be used as the initiator for non-AUG translation [81]. Besides eIF2, two alternative initiator tRNA binding eIFs, i.e., eIF2A and eIF2D, can deliver Met-tRNAiMet and even non-Met-tRNA to initiate non-AUG start codons, particularly in a GTP-independent manner [82–85]. An eIF2A-initiated non-AUG uORF is essential for the translation of GRP78 mRNAs under cell stress [82]. Another report has implicated a role of eIF2A-initiated non-AUG uORF in initiation and progression of squamous cell carcinoma [85]. Moreover, alternative usage of start codons may impact proteomes, and hence have detrimental effects on cell physiology [86]. In addition, the eIF5-mimic protein (5MP) suppresses non-AUG translation by competing with eIF5 for eIF2 [87]. Therefore, alternative translation initiators or regulators modulate the efficiency of non-AUG uORF activation, which hence impacts main CDS translation. Utilization of non-AUG initiation can also be influenced by the start-codon sequence context or mRNA secondary structures. As described above, Ded1 inactivation enhances secondary structure-assisted non-AUG translation initiation in yeast [61]. Whether mammalian RNA helicases also play a role similar to that of Ded1 needs to be tested.

Regulation of uORF-mediated translational control by trans-acting factors

In addition to stress-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α, here we discuss additional factors that influence uORF-mediated translation and the underlying mechanisms.

Cap-binding complexes

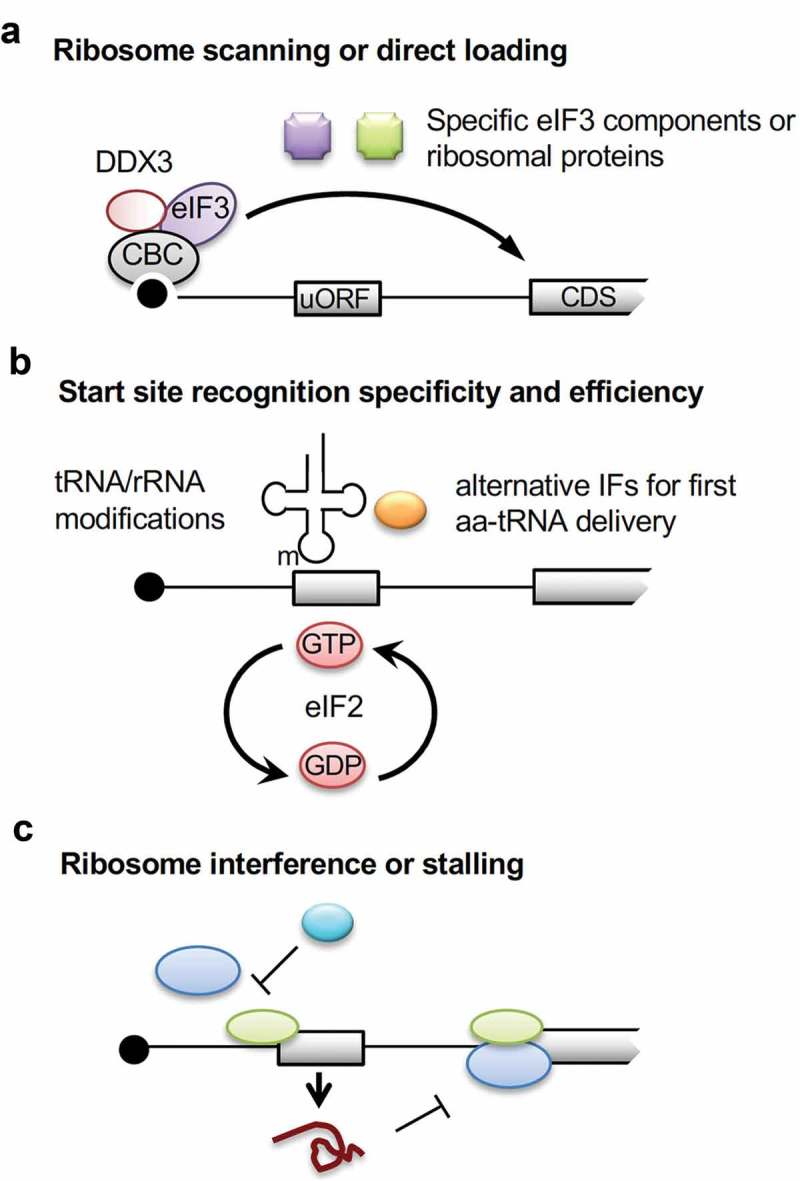

uORF-mediated translational control essentially plays a role in rapid and reversible changes in protein production upon cell stress; however, it can also be influenced by mTOR signaling [88,89]. mTOR depletion reduces the level of ATF4 (Figure 4a). mTOR-mediated translation of ATF4 mRNA requires 4E-BPs, suggesting that release of eIF4E from 4E-BPs is important for ATF4 translation. The mTOR/4E-BP pathway also regulates uORF-modulated translation of the CEBPB mRNA [90]. However, the cellular response to different stressors renders differential dependence of eIF4E phosphorylation on the translation of uORF-containing mRNAs [91]. Moreover, eIF4E knockdown does not significantly affect ATF4 levels in certain cancer cell lines [65], suggesting that additional mTOR-regulated factors also contribute to ATF4 translation. In those cell lines, DDX3 in conjunction with the nuclear CBC and the eIF3 complex promotes the translation of ATF4 and several other related uORF-containing mRNAs [65] (Figure 5a). Perhaps the use of the CBC rather than eIF4E leads to a greater tendency for leaky scanning. It would be interesting to investigate whether eIF4E and the CBC are differentially involved in uORF-mRNA translation or regulate translation under different cellular conditions.

Figure 5.

Advanced mechanisms of uORF-mediated translational control.

(a) In the presence of a high level of DDX3, the nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC) that remains on uORF-containing mRNAs recruits the eIF3 or its subunits for preferential translation of CDS. Alternatively, specific eIF3 or ribosomal subunits may participate in translational regulation of uORF-containing mRNAs. (b) Modification of tRNA/rRNA or usage of alternative initiation factors such as eIF2A and eIF2D to deliver the first aminoacyl (aa)-tRNA may alter the specificity and/or efficiency of start site recognition and therefore modulate uORF-mediated translational control. (c) Several initiation factors such as eIF3, eIF5B and eIF6 modulate uORF-mediated translation possibly via regulating the kinetics of ribosomal subunit joining. uORF-encoding peptides may stall ribosomes and prevent translation of downstream CDS (bottom panel).

eIF3

eIF3 is the largest initiation complex in mammalian cells, consisting of 12 core subunits. The eIF3 complex is essential for the formation of both the 43S preinitiation and 48S initiation complex through interaction with eIF4F and the 40S ribosomal subunit, respectively [92]. In budding yeast, eIF3 remains associated with translating ribosomes during uORF translation and facilitates reinitiation of the post-termination complex at downstream AUGs [93,94]. In plants, the eIF3h subunit promotes reinitiation of uORF-containing mRNAs [95]. TOR-activated S6K1 can phosphorylate eIF3h, which then enables polysome loading to uORF-containing mRNAs [96]. In mammalian cells, eIF3 subunits preferentially associate with a set of uTIS-enriched mRNAs [65,97]. In oral cancer cells, eIF3a, g, h, i but not eIF3l are essential for DDX3-activated ATF4 translation [65]. Therefore, it is possible that eIF3 subcomplexes conduct uORF mRNA translation or that certain eIF3 subunits recruit specific initiation/trans factors for translational regulation (Figure 5a).

eIFs that modulate eIF2 cycling

After eIF2-GTP delivers the initiator Met-tRNAi to the ribosomal P-site, the GTPase activating protein eIF5 promotes GTP hydrolysis and phosphate release as well as eIF2 dissociation from the ribosome. To recycle eIF2, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B promotes eIF5 dissociation from GDP-bound eIF2 and facilitates GTP/GDP exchange [15,98] (Figure 1b). Disruption of eIF2 activity or recycling impacts uORF-mediated translation control (Figure 5b). For example, mutations of eIF2B that impair ternary complex formation derepress uORF-containing GCN4 translation [99]. A recent study showed that eIF2γ mutations, which are linked to MEHMO syndrome, a subgroup of syndromic X-linked mental retardation, also activate the translation of GCN4 and ATF4 [100]. On the other hand, an eIF2β mutation that impairs eIF5-mediated GDP dissociation from eIF2 abrogates GCN4 translation during amino acid starvation [101,102]. Consistent with these findings, disruption of eIF5 activities also suppresses GCN4 translation likely via activating an upstream AUG or UUG start codon [102]. Additionally, eIF1 contributes to stringent start-site selection by blocking phosphate release from eIF2 at non-AUG codons or AUGs in a suboptimal context. Depletion of eIF1 results in upregulation of ATF4 owing to attenuated uORF translation [103]. Together, the dynamic GTP/GDP status of eIF2 is critical for start-site recognition and contributes significantly to uORF-mediated translational regulation. Finally, a recent report indicated that the GTPase eIF5B acts as a surrogate of eIF2 under hypoxic conditions and is required for the ATF4-mediated stress response as well as expression of key factors that function in metabolic adaptation [104], suggesting that multiple translation initiation pathways exist for stress responses (Figure 4A).

Factors with anti-ribosomal subunit joining activity

The joining of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits is certainly the key step of translation. eIF6 is involved in 60S ribosome maturation and it also prevents premature 40S-60S joining, which may enhance the incidence of leaky 40S ribosome subunit scanning. eIF6 promotes ATF4 translation and also preferentially activates downstream start-site usage within the CEBPB mRNA, generating the oncogenic LIP isoform [105] (Figure 4B). Hence upregulation of eIF6 in various types of cancers promotes tumorigenesis [106]. Analogously, it has been proposed that eIF3 on the 40S subunit also has an anti-joining function [107] (Figure 5c). Several of the eIF3 subunits are indeed required for ATF4 mRNA translation [65]. Perhaps eIF3 favors initiation at the main CDS through its anti-joining function. Finally, mutations of certain yeast ribosomal proteins cause delayed 60S joining and therefore render the 40S subunit prone to skipping uORFs [108,109].

Additional factors with potential involvement in uORF-mediated translation regulation

Heterogeneity of the translation machinery

As described above, uORF-mediated translation control can be modulated by alternative translation factors in cancer, such as eIF2A and eIF5B [82,104]. Recent studies revealed the existence of heterogeneous ribosomes, eIF4F complexes, and eIF3 complexes [110,111]. Moreover, leaderless mRNAs can be translated by direct 80S binding or in an eIF2 and eIF4F independent manner [112]. Specialized ribosomes lacking specific core ribosomal proteins or containing ribosomal protein paralogs may contribute to selective mRNA translation. For example, ribosomal protein RPL10A is possibly involved in the translation of certain IRES-containing viral and cellular transcripts [113]. DNA damage induces the binding of RPL26 to the 5ʹ UTR of p53 mRNA and hence promotes its translation [114]. More notably, mutations of certain ribosomal proteins specifically alter translation of uORF-containing mRNAs [108,115–117]. Therefore, it would be interesting to know whether any ribosomal protein is involved in uORF-mediated translational control under normal or stress conditions or in cancer cells. Like eIF2A, eIF2D can facilitate initiation at non-AUG codons [86] (Figure 5b). A recent report revealed that co-deletion of the yeast eIF2D (Tma64) and a ribosome recycling factor (Tma20 or Tma22) results in translation reinitiation at downstream AUG codons after translation termination and hence promotes translation of uORF-containing reporters [118]. Moreover, eIF2D knockout altered ribosome profiling reads in uORFs of GCN4, suggesting a regulatory role for eIF2D in translation of uORF-containing mRNAs [119]. Whether cell stress or oncogenic signaling modulates the activity of these factors and hence influences uORF activation or CDS translation remains to be investigated.

rRNA/tRNA modifications

Various modifications in tRNA and rRNA may widely impact translation [120] (Figure 5b). In bacteria, N4-methylation at C1402 of 23S rRNA, a residue in the P-site, contributes to decoding fidelity [121]. Defective methylation of C1402 activates non-AUG initiation and decreases the rate of UGA read-through. A recent report shows that m6A4220 modification in human 28S rRNA influences global translation and cell proliferation. The m6A methyltransferase ZCCHC4 responsible for m6A4220 modification is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma tumors. Thus, dysregulation of rRNA modifications correlates with cancer [122]. Besides base modifications, an increase of fibrillarin-mediated 2ʹ-O-methylation of rRNAs results in compromised translational fidelity and selective IRES-dependent translation in p53-inactivated cancer cells [123]. Modification of tRNAs also impacts their functional diversity. In yeast, sulfur deficiency reduces wobble uridine (U34) thiolation of tRNAs and hence influences translational capacity and metabolic homeostasis [124], implying that tRNA modification changes under environmental stress or nutrient limited conditions in cancer may trigger translational reprogramming. In humans, modification of the wobble uridine of tRNA, i.e., 5-methoxycarbonyl-methyl-2-thiouridine (mcm5s2), expands its decoding capacity, and hence increases HIF1α production. The PI3K-mTORC2 pathway promotes mcm5s2 modification in certain cancers [125]. It is also noteworthy that defective in U34 modifying enzymes differentially modulates the translation of a set of mRNAs presumably through their uORFs in yeast [126]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that rRNA/tRNA modifications may impact the expression of oncogenic or stress proteins via modulating the translation capacity of uORFs.

uORF-encoded polypeptides

uORFs may encode polypeptides that modulate translation or have other cellular functions (Figure 5c). In fungi, a uORF-encoded arginine attenuator peptide causes translation stalling by interfering with the peptidyltransferase center in response to arginine [127]. Recently, a combination of ribo-seq, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, and computational studies revealed a tremendous number of small ORF-encoded peptides from a variety of RNA species in mammalian cells [128,129]. uORF-encoded peptides may in cis cause ribosome stalling or limit ribosomal access to the CDS or act in trans to suppress translation in a cell-free system, although the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated [130]. Notably, a recent report revealed that uORF-encoded peptides can act as ligands for the major histocompatibility complex class I and thus elicit T-cell responses [82]. Therefore, widespread uORFs may play a role in shaping the immune response to cancer via producing short peptides.

Pathological implications of uORF-mediated translation control in cancer

Oncogenes are enriched for uORFs [131,132]. Dysregulation of uORF-mediated translational control of oncogenic mRNAs may contribute to the pathophysiology of cancer. uORF-mediated inhibition of the translation of HER2 mRNA, which encodes an epidermal growth factor receptor, is derepressed in breast cancer [133]. Inactivation of uORF increases the truncated isoforms of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ that are respectively associated with acute myeloid leukemia and breast cancer [52]. Genetic mutations in uORFs influence uORF translation capacity. A systematic search for cancer-associated mutations of uORFs recently identified ~400 such mutations [53]. For example, loss-of-function uORF mutations in EPHB1, which encodes an EPH-related tyrosine kinase, and MAP2K6, which encodes a kinase involved in the MAP kinase pathway, are associated with tumorigenesis [53]. A 4-base deletion in the uORF of CDKN1B encoding the Cdk inhibitor p27 lengthens this uORF and whereby downregulates p27 levels in cancer [134]. Therefore, gain- or loss-of-function of uORF may activate oncogenes or inactivate tumor suppressors, respectively, and hence promotes cancer progression. Besides, altered expression levels or activity of trans-acting factors or disrupted signaling pathways in cancer can also affect uORF-mediated translation [43]. Upregulation of DDX3 in head-and neck squamous carcinomas increases ATF4 mRNA translation and hence promotes metastasis [65]. Heterozygous deletion of eIF6 represses the translation of uORF-containing mRNAs and therefore prevents oncogene-induced tumor formation [105,107,135]. A recent report shows that cellular magnesium levels modulate the translation of uORF-containing mRNAs encoding the PTP4A-family protein phosphatase via the AMPK/mTORC2 pathway [136]. Thus, uORF-mediated translational control can influence bioenergetics of cancer cells in response to environmental cues.

Conclusion and perspectives

uORF-mediated control contributes profoundly to the translation of cancer-related and stress-response transcripts. However, a myriad of unresolved issues remain such as how uORFs modulate protein synthesis in response to various signaling pathways and functions coordinately with adjacent uORFs or other cis-regulatory elements. Moreover, additional issues are just beginning to emerge, such as how non-AUG uORFs, noncanonical translation factors, and RNA modifications impact uORF-mediated control. As described above, the expression of ATF4 and LIP has been implicated in cellular stress response and cancer. Therapeutic inactivation of these oncogenic factors may reduce tumor growth and metastasis and overcome resistance to chemotherapy. One strategy is to reduce ATF4 translation by using pharmacological agents to inhibit upstream eIF2α kinases or target phospho-eIF2α signaling [137]. A combination of eIF6 ablation and mTOR inhibition may suppress LIP expression in cancer [138]. Also notably, a recent report revealed that the MYC oncogene enhances the translation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) mRNA through bypassing uORF-mediated translation repression, and hence Myc overproduction promotes immune escape of tumors. Inhibition of eIF4E phosphorylation downregulates PD-L1 production and thus provides a potential new immunotherapeutic strategy [139]. Therefore, targeting factors in pathways underlying the mechanisms of uORF-mediated translation would benefit cancer therapy.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica [IBMS-CRC107-P03].

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| C/EBPβ | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β |

| CUGBP1 | CUG repeat RNA binding protein 1 |

| DDIT3 | DNA damage inducible transcript 3 |

| eEF2K | eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase |

| EPHB1 | EPH receptor B1 |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| GADD3 | growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein |

| GCN2 | general control nonderepressible 2 |

| HRI | heme-regulated eIF2α kinase |

| LAP | liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein |

| LIP | liver-enriched transcriptional inhibitory protein |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEHMO | Mental retardation, epileptic seizures, hypogenitalism, microcephaly and obesity |

| MNK | MAPK-interacting kinases |

| mTORC1/2 | mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1/2 |

| ODC1 | ornithine decarboxylase 1 |

| PERK | protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKR | RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR |

| PTP4A | Protein tyrosine phosphatase Type IV A |

| SBDS | The Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein |

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| YTH | YT521-B homology |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, grant IBMS-CRC107-P03.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Sato H, Maquat LE.. Remodeling of the pioneer translation initiation complex involves translation and the karyopherin importin beta. Genes Dev. 2009;23(21):2537–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ishigaki Y, Li X, Serin G, et al. Evidence for a pioneer round of mRNA translation: mRNAs subject to nonsense-mediated decay in mammalian cells are bound by CBP80 and CBP20. Cell. 2001;106(5):607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hershey JW, Sonenberg N, Mathews MB. Principles of translational control: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(12):a011528-a011528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hinnebusch AG. The scanning mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83779–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hinnebusch AG. Structural insights into the mechanism of scanning and start codon recognition in Eukaryotic translation initiation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42(8):589–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pestova TV, Lomakin IB, Lee JH, et al. The joining of ribosomal subunits in eukaryotes requires eIF5B. Nature. 2000;403(6767):332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Truitt ML, Ruggero D. New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(5):288–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Curran JA, Weiss B. What is the impact of mRNA 5ʹ TL heterogeneity on translational start site selection and the mammalian cellular phenotype? Front Genet. 2016;7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pisareva VP, Pisarev AV, Komar AA, et al. Translation initiation on mammalian mRNAs with structured 5ʹUTRs requires DExH-box protein DHX29. Cell. 2008;135(7):1237–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Soto-Rifo R, Rubilar PS, Limousin T, et al. DEAD-box protein DDX3 associates with eIF4F to promote translation of selected mRNAs. Embo J. 2012;31(18):3745–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Murat P, Marsico G, Herdy B, et al. RNA G-quadruplexes at upstream open reading frames cause DHX36- and DHX9-dependent translation of human mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fitzgerald KD, Semler BL. Bridging IRES elements in mRNAs to the eukaryotic translation apparatus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789(9–10):518–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wethmar K, Smink JJ, Leutz A. Upstream open reading frames: molecular switches in (patho)physiology. Bioessays. 2010;32(10):885–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Somers J, Poyry T, Willis AE. A perspective on mammalian upstream open reading frame function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(8):1690–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Young SK, Wek RC. Upstream open reading frames differentially regulate gene-specific translation in the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(33):16927–16935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Robichaud N, Sonenberg N, Ruggero D, et al. Translational control in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;a032896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N. mRNA translation and energy metabolism in cancer: the role of the MAPK and mTORC1 pathways. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76355–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Culjkovic B, Topisirovic I, Skrabanek L, et al. eIF4E is a central node of an RNA regulon that governs cellular proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(3):415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Truitt ML, Conn CS, Shi Z, et al. Differential requirements for eIF4E dose in normal development and cancer. Cell. 2015;162(1):59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Furic L, Rong L, Larsson O, et al. eIF4E phosphorylation promotes tumorigenesis and is associated with prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(32):14134–14139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, et al. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005;123(4):569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Andreou AZ, Harms U, Klostermeier D. eIF4B stimulates eIF4A ATPase and unwinding activities by direct interaction through its 7-repeats region. RNA Biol. 2017;14(1):113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shahbazian D, Parsyan A, Petroulakis E, et al. eIF4B controls survival and proliferation and is regulated by proto-oncogenic signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(20):4106–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, et al. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 2012;485(7396):109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485(7396):55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Morita M, Gravel SP, Chenard V, et al. mTORC1 controls mitochondrial activity and biogenesis through 4E-BP-dependent translational regulation. Cell Metab. 2013;18(5):698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu B, Qian SB. Translational reprogramming in cellular stress response. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5(3):301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kenney JW, Moore CE, Wang X, et al. Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase, an unusual enzyme with multiple roles. Adv Biol Regul. 2014;5515–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Patel J, McLeod LE, Vries RG, et al. Cellular stresses profoundly inhibit protein synthesis and modulate the states of phosphorylation of multiple translation factors. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(12):3076–3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Komar AA, Hatzoglou M. Cellular IRES-mediated translation: the war of ITAFs in pathophysiological states. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(2):229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Leppek K, Das R, Barna M. Functional 5ʹ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(3):158–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Halaby MJ, Harris BR, Miskimins WK, et al. Deregulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated p53 translation in cancer cells with defective p53 response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(23):4006–4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, et al. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125(6):1111–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, et al. 5ʹ UTR m(6)A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163(4):999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Powers EN, Brar GA. m(6)A and eIF2alpha- team up to tackle ATF4 translation during stress. Mol Cell. 2018;69(4):537–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, et al. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526(7574):591–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Johnstone TG, Bazzini AA, Giraldez AJ. Upstream ORFs are prevalent translational repressors in vertebrates. Embo J. 2016;35(7):706–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McGillivray P, Ault R, Pawashe M, et al. A comprehensive catalog of predicted functional upstream open reading frames in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(7):3326–3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wethmar K, Barbosa-Silva A, Andrade-Navarro MA, et al. uORFdb–a comprehensive literature database on eukaryotic uORF biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Databaseissue):D60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, Mootha VK. Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(18):7507–7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wethmar K. The regulatory potential of upstream open reading frames in eukaryotic gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5(6):765–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barbosa C, Peixeiro I, Romao L. Gene expression regulation by upstream open reading frames and human disease. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chew GL, Pauli A, Schier AF. Conservation of uORF repressiveness and sequence features in mouse, human and zebrafish. Nat Commun. 2016;711663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(1):27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Szamecz B, Rutkai E, Cuchalova L, et al. eIF3a cooperates with sequences 5ʹ of uORF1 to promote resumption of scanning by post-termination ribosomes for reinitiation on GCN4 mRNA. Genes Dev. 2008;22(17):2414–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Munzarova V, Panek J, Gunisova S, et al. Translation reinitiation relies on the interaction between eIF3a/TIF32 and progressively folded cis-acting mRNA elements preceding short uORFs. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(7):e1002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Calkhoven CF, Muller C, Leutz A. Translational control of C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta isoform expression. Genes Dev. 2000;14(15):1920–1932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zahnow CA, Cardiff RD, Laucirica R, et al. A role for CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta-liver-enriched inhibitory protein in mammary epithelial cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2001;61(1):261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Luft FC. C/EBPbeta LIP induces a tumor menagerie making it an oncogene. J Mol Med (Berl). 2015;93(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chiribau CB, Gaccioli F, Huang CC, et al. Molecular symbiosis of CHOP and C/EBP beta isoform LIP contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(14):3722–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wethmar K, Begay V, Smink JJ, et al. C/EBPbetaDeltauORF mice–a genetic model for uORF-mediated translational control in mammals. Genes Dev. 2010;24(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schulz J, Mah N, Neuenschwander M, et al. Loss-of-function uORF mutations in human malignancies. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Noderer WL, Flockhart RJ, Bhaduri A, et al. Quantitative analysis of mammalian translation initiation sites by FACS-seq. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Grzegorski SJ, Chiari EF, Robbins A, et al. Natural variability of Kozak sequences correlates with function in a zebrafish model. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pisarev AV, Kolupaeva VG, Pisareva VP, et al. Specific functional interactions of nucleotides at key −3 and +4 positions flanking the initiation codon with components of the mammalian 48S translation initiation complex. Genes Dev. 2006;20(5):624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Palam LR, Baird TD, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):10939–10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Young SK, Willy JA, Wu C, et al. Ribosome reinitiation directs gene-specific translation and regulates the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(47):28257–28271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kozak M. Downstream secondary structure facilitates recognition of initiator codons by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(21):8301–8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Eriani G, Martin F. START: structure-assisted RNA translation. RNA Biol. 2018;15(9):1250–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Guenther UP, Weinberg DE, Zubradt MM, et al. The helicase Ded1p controls use of near-cognate translation initiation codons in 5ʹ UTRs. Nature. 2018;559(7712):130–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lai MC, Chang WC, Shieh SY, et al. DDX3 regulates cell growth through translational control of cyclin E1. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(22):5444–5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chen HH, Yu HI, Cho WC, et al. DDX3 modulates cell adhesion and motility and cancer cell metastasis via Rac1-mediated signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2015;34(21):2790–2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chen HH, Yu HI, Tarn WY. DDX3 modulates neurite development via translationally activating an RNA regulon involved in Rac1 activation. J Neurosci. 2016;36(38):9792–9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chen HH, Yu HI, Yang MH, et al. DDX3 activates CBC-eIF3-mediated translation of uORF-containing oncogenic mRNAs to promote metastasis in HNSCC. Cancer Res. 2018;78(16):4512–4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lee S, Liu B, Lee S, et al. Global mapping of translation initiation sites in mammalian cells at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(37):E2424–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Rhodes D, Lipps HJ. G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(18):8627–8637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tabet R, Schaeffer L, Freyermuth F, et al. CUG initiation and frameshifting enable production of dipeptide repeat proteins from ALS/FTD C9ORF72 transcripts. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Coots RA, Liu XM, Mao Y, et al. m(6)A Facilitates eIF4F-Independent mRNA Translation. Mol Cell. 2017;68(3):504–514 e507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhou J, Wan J, Shu XE, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine guides mRNA alternative translation during integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2018;69(4):636–647 e637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Anders M, Chelysheva I, Goebel I, et al. Dynamic m(6)A methylation facilitates mRNA triaging to stress granules. Life Sci Alliance. 2018;1(4):e201800113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Engel M, Eggert C, Kaplick PM, et al. The role of m(6)A/m-RNA methylation in stress response regulation. Neuron. 2018;99(2):389–403 e389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Cenik C, Derti A, Mellor JC, et al. Genome-wide functional analysis of human 5ʹ untranslated region introns. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lim CS, T. Wardell SJ, Kleffmann T, et al. The exon-intron gene structure upstream of the initiation codon predicts translation efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(9):4575–4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chazal PE, Daguenet E, Wendling C, et al. EJC core component MLN51 interacts with eIF3 and activates translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):5903–5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Maquat LE, Tarn WY, Isken O. The pioneer round of translation: features and functions. Cell. 2010;142(3):368–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Le Hir H, Sauliere J, Wang Z. The exon junction complex as a node of post-transcriptional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zhang C, Jia G. Reversible RNA Modification N(1)-methyladenosine (m(1)A) in mRNA and tRNA. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2018;16(3):155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Kochetov AV, Prayaga PD, Volkova OA, et al. Hidden coding potential of eukaryotic genomes: nonAUG started ORFs. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2013;31(1):103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Rodriguez CM, Chun SY, Mills RE, et al. Translation of upstream open reading frames in a model of neuronal differentiation. bioRxiv. 2018. DOI: 10.1101/412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Peabody DS. Translation initiation at non-AUG triplets in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(9):5031–5035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Starck SR, Tsai JC, Chen K, et al. Translation from the 5ʹ untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response. Science. 2016;351(6272):aad3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Starck SR, Jiang V, Pavon-Eternod M, et al. Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science. 2012;336(6089):1719–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Liang H, He S, Yang J, et al. PTENalpha, a PTEN isoform translated through alternative initiation, regulates mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. Cell Metab. 2014;19(5):836–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Sendoel A, Dunn JG, Rodriguez EH, et al. Translation from unconventional 5ʹ start sites drives tumour initiation. Nature. 2017;541(7638):494–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Kearse MG, Wilusz JE. Non-AUG translation: a new start for protein synthesis in eukaryotes. Genes Dev. 2017;31(17):1717–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Tang L, Morris J, Wan J, et al. Competition between translation initiation factor eIF5 and its mimic protein 5MP determines non-AUG initiation rate genome-wide. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(20):11941–11953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Park Y, Reyna-Neyra A, Philippe L, et al. mTORC1 balances cellular amino acid supply with demand for protein synthesis through post-transcriptional control of ATF4. Cell Rep. 2017;19(6):1083–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Ben-Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult SJH, Asara JM, Manning BD mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science. 2016;351(6274):728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Zidek LM, Ackermann T, Hartleben G, et al. Deficiency in mTORC1-controlled C/EBPbeta-mRNA translation improves metabolic health in mice. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(8):1022–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chen YJ, Tan BC, Cheng YY, et al. Differential regulation of CHOP translation by phosphorylated eIF4E under stress conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(3):764–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Valasek LS, Zeman J, Wagner S, et al. Embraced by eIF3: structural and functional insights into the roles of eIF3 across the translation cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(19):10948–10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Mohammad MP, Munzarova Pondelickova V, Zeman J, et al. In vivo evidence that eIF3 stays bound to ribosomes elongating and terminating on short upstream ORFs to promote reinitiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(5):2658–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Hronova V, Mohammad MP, Wagner S, et al. Does eIF3 promote reinitiation after translation of short upstream ORFs also in mammalian cells? RNA Biol. 2017;14(12):1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Roy B, Vaughn JN, Kim BH, et al. The h subunit of eIF3 promotes reinitiation competence during translation of mRNAs harboring upstream open reading frames. RNA. 2010;16(4):748–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Schepetilnikov M, Dimitrova M, Mancera-Martinez E, et al. TOR and S6K1 promote translation reinitiation of uORF-containing mRNAs via phosphorylation of eIF3h. Embo J. 2013;32(8):1087–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lee AS, Kranzusch PJ, Cate JH. eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature. 2015;522(7554):111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Pavitt GD. Regulation of translation initiation factor eIF2B at the hub of the integrated stress response. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9(6):e1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59407–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Young-Baird SK, Shin BS, Dever TE. MEHMO syndrome mutation EIF2S3-I259M impairs initiator Met-tRNAiMet binding to eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47(2):855–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Jennings MD, Kershaw CJ, White C, et al. eIF2beta is critical for eIF5-mediated GDP-dissociation inhibitor activity and translational control. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(20):9698–9709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Antony AC, Alone PV. Defect in the GTPase activating protein (GAP) function of eIF5 causes repression of GCN4 translation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(4):1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Fijalkowska D, Verbruggen S, Ndah E, et al. eIF1 modulates the recognition of suboptimal translation initiation sites and steers gene expression via uORFs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(13):7997–8013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ho JJD, Balukoff NC, Cervantes G, et al. Oxygen-sensitive remodeling of central carbon metabolism by Archaic eIF5B. Cell Rep. 2018;22(1):17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Brina D, Miluzio A, Ricciardi S, et al. eIF6 coordinates insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism by coupling translation to transcription. Nat Commun. 2015;68261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Zhu W, Li GX, Chen HL, et al. The role of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 6 in tumors. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Brina D, Grosso S, Miluzio A, et al. Translational control by 80S formation and 60S availability: the central role of eIF6, a rate limiting factor in cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(20):3441–3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Steffen KK, MacKay VL, Kerr EO, et al. Yeast life span extension by depletion of 60s ribosomal subunits is mediated by Gcn4. Cell. 2008;133(2):292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Martin-Marcos P, Hinnebusch AG, Tamame M. Ribosomal protein L33 is required for ribosome biogenesis, subunit joining, and repression of GCN4 translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(17):5968–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Ho JJD, Lee S. A cap for every occasion: alternative eIF4F complexes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41(10):821–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Briggs JW, Dinman JD. Subtractional heterogeneity: a crucial step toward defining specialized ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2017;67(1):3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Akulich KA, Andreev DE, Terenin IM, et al. Four translation initiation pathways employed by the leaderless mRNA in eukaryotes. Sci Rep. 2016;637905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Shi Z, Fujii K, Kovary KM, et al. Heterogeneous ribosomes preferentially translate distinct subpools of mRNAs genome-wide. Mol Cell. 2017;67(1):71–83 e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Dai MS, Shi D, Jin Y, et al. Regulation of the MDM2-p53 pathway by ribosomal protein L11 involves a post-ubiquitination mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(34):24304–24313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Zhou F, Roy B, von Arnim AG. Translation reinitiation and development are compromised in similar ways by mutations in translation initiation factor eIF3h and the ribosomal protein RPL24. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].von Arnim AG, Jia Q, Vaughn JN. Regulation of plant translation by upstream open reading frames. Plant Sci. 2014;2141–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Kakehi J, Kawano E, Yoshimoto K, et al. Mutations in ribosomal proteins, RPL4 and RACK1, suppress the phenotype of a thermospermine-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0117309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Young DJ, Makeeva DS, Zhang F, et al. Tma64/eIF2D, Tma20/MCT-1, and Tma22/DENR recycle post-termination 40S subunits in vivo. Mol Cell. 2018;71(5):761–774 e765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Makeeva DS, Lando AS, Anisimova A, et al. Translatome and transcriptome analysis of TMA20 (MCT-1) and TMA64 (eIF2D) knockout yeast strains. Data Brief. 2019;23:103701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Sloan KE, Warda AS, Sharma S, et al. Tuning the ribosome: the influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2017;14(9):1138–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Kimura S, Suzuki T. Fine-tuning of the ribosomal decoding center by conserved methyl-modifications in the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Ma H, Wang X, Cai J, et al. N(6-)Methyladenosine methyltransferase ZCCHC4 mediates ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(1):88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Marcel V, Ghayad SE, Belin S, et al. p53 acts as a safeguard of translational control by regulating fibrillarin and rRNA methylation in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(3):318–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Laxman S, Sutter BM, Wu X, et al. Sulfur amino acids regulate translational capacity and metabolic homeostasis through modulation of tRNA thiolation. Cell. 2013;154(2):416–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Rapino F, Delaunay S, Rambow F, et al. Codon-specific translation reprogramming promotes resistance to targeted therapy. Nature. 2018;558(7711):605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Chou HJ, Donnard E, Gustafsson HT, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis of roles for tRNA modifications in translational regulation. Mol Cell. 2017;68(5):978–992 e974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Wei J, Wu C, Sachs MS. The arginine attenuator peptide interferes with the ribosome peptidyl transferase center. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(13):2396–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Plaza S, Menschaert G, Payre F. In search of lost small peptides. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33391–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Ji Z, Song R, Regev A, et al. Many lncRNAs, 5ʹUTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. Elife. 2015;4e08890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Cabrera-Quio LE, Herberg S, Pauli A. Decoding sORF translation - from small proteins to gene regulation. RNA Biol. 2016;13(11):1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Kozak M. An analysis of 5ʹ-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(20):8125–8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Ye Y, Liang Y, Yu Q, et al. Analysis of human upstream open reading frames and impact on gene expression. Hum Genet. 2015;134(6):605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Mehta A, Trotta CR, Peltz SW. Derepression of the Her-2 uORF is mediated by a novel post-transcriptional control mechanism in cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2006;20(8):939–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Occhi G, Regazzo D, Trivellin G, et al. A novel mutation in the upstream open reading frame of the CDKN1B gene causes a MEN4 phenotype. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(3):e1003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Miluzio A, Beugnet A, Grosso S, et al. Impairment of cytoplasmic eIF6 activity restricts lymphomagenesis and tumor progression without affecting normal growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(6):765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Hardy S, Kostantin E, Wang SJ, et al. Magnesium-sensitive upstream ORF controls PRL phosphatase expression to mediate energy metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(8):2925–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Singleton DC, Harris AL. Targeting the ATF4 pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(12):1189–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Smink JJ, Begay V, Schoenmaker T, et al. Transcription factor C/EBPbeta isoform ratio regulates osteoclastogenesis through MafB. Embo J. 2009;28(12):1769–1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Xu Y, Poggio M, Jin HY, et al. Translation control of the immune checkpoint in cancer and its therapeutic targeting. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]