Abstract

Mutations in the cardiac thin filament (TF) have highly variable effects on the regulatory function of the cardiac sarcomere. Understanding the molecular-level dysfunction elicited by TF mutations is crucial to elucidate cardiac disease mechanisms. The hypertrophic cardiomyopathy–causing cardiac troponin T (cTnT) mutation Δ160Glu (Δ160E) is located in a putative “hinge” adjacent to an unstructured linker connecting domains TNT1 and TNT2. Currently, no high-resolution structure exists for this region, limiting significantly our ability to understand its role in myofilament activation and the molecular mechanism of mutation-induced dysfunction. Previous regulated in vitro motility data have indicated mutation-induced impairment of weak actomyosin interactions. We hypothesized that cTnT-Δ160E repositions the flexible linker, altering weak actomyosin electrostatic binding and acting as a biophysical trigger for impaired contractility and the observed remodeling. Using time-resolved FRET and an all-atom TF model, here we first defined the WT structure of the cTnT-linker region and then identified Δ160E mutation-induced positional changes. Our results suggest that the WT linker runs alongside the C terminus of tropomyosin. The Δ160E-induced structural changes moved the linker closer to the tropomyosin C terminus, an effect that was more pronounced in the presence of myosin subfragment (S1) heads, supporting previous findings. Our in silico model fully supported this result, indicating a mutation-induced decrease in linker flexibility. Our findings provide a framework for understanding basic pathogenic mechanisms that drive severe clinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotypes and for identifying structural targets for intervention that can be tested in silico and in vitro.

Keywords: molecular dynamics, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), allosteric regulation, cardiomyopathy, mutant, troponin, allostery, cardiac thin filament, heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, muscle contraction

Introduction

HCM3 is the most common genetic cardiac disorder, with a prevalence of at least 0.2% in the general population (1), and is a leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young adults (2). Up to 11% of HCM is caused by mutations in cardiac troponin T (cTnT) (3, 4), a sarcomeric protein that anchors the cardiac ternary troponin (cTn) complex to tropomyosin (Tm) (5). cTnT modulates calcium-induced activation of the cardiac TF, leading to highly regulated contraction of the myocardium (5). Moreover, cTnT plays a crucial role in cardiac myofibrillogenesis (6, 7). Early proteolytic studies demonstrated that cTnT comprises two functional domains: the Tm-binding TNT1 domain and the calcium-sensitive TNT2 domain, which binds cardiac troponin I (cTnI), cardiac troponin C (cTnC), and Tm (8, 9). A long (∼50-amino acid (aa)) flexible linker connecting the TNT1 and TNT2 domains (Fig. 1A) is essential for transmitting the calcium-induced conformational changes from the C-terminal end of cTnT to the N terminus. CD studies suggested that the TNT1 domain and the proximal linker region have an α-helical character (10); however, the structural details of these functionally important domains were unknown because of their absence from the crystal structure of the human cTn core (11) and cryo-EM reconstruction of the cardiac TF (12). This limited structural information on the cTnT linker region greatly impairs our ability to understand the mechanism of TF activation and molecular pathogenesis of HCM induced by mutations in this region.

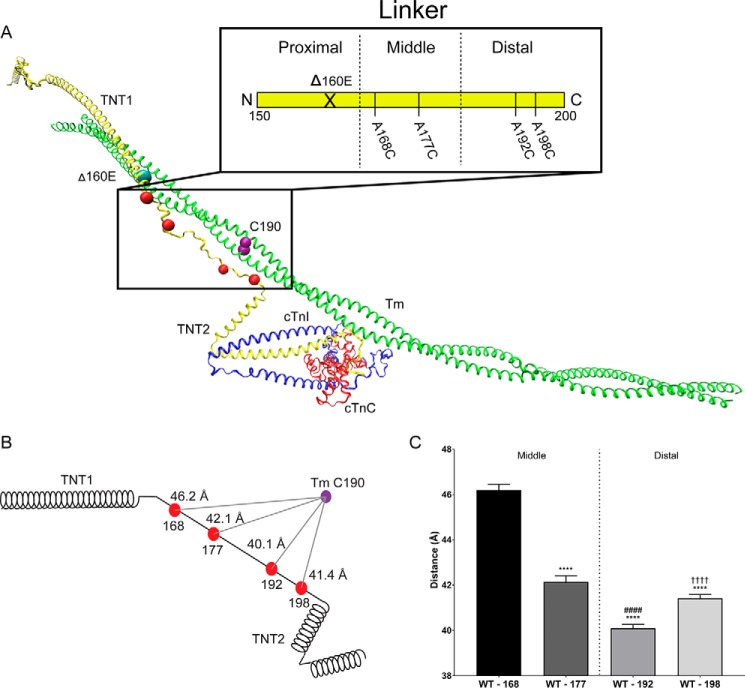

Figure 1.

Average position of the WT-cTnT linker region. A, atomistic model of human cardiac thin filament components: troponin complex (cTnT, yellow; cTnI, blue; cTnC, red) and a single Tm dimer (green) with the position of the Δ160E mutation (cyan bead), FRET donor attachment sites (red beads), and FRET acceptor attachment site (purple bead). Inset, schematic of cTnT-Linker divided into three hypothetical regions (proximal, middle, and distal) for simplicity. F-actin was removed for clarity. B, schematic representation of cTnT including the donor (red beads) and acceptor (purple) sites. The distances reported reflect the average distance (across calcium and myosin S1 status) of the linker region relative to Tm Cys-190 (Table 1). C, bar graph of the average position of each linker residue separated into the middle and distal regions. The reported statistics are the results of a one-way ANOVA with Sidak correction. ****, p < 0.0001 versus A168C; ####, p < 0.0001 versus A177C; ††††, p < 0.0001 versus A192C.

The majority of HCM-linked cTnT mutations reside within or flanking the TNT1 domain (13). TNT1 mutations cluster at the N- and C-terminal regions with two of the known mutational hot spots occurring at residues 92 (R92Q, R92L, R92W (2, 4, 14–20)) and 160–163 (Δ160E, E163R, E163K (2, 4, 14, 21–28)). Although TNT1 N-terminal mutations affect Tm–TNT1 binding affinity and the stability of the Tm overlap region, the C-terminal mutations have no direct effect on the Tm-dependent properties of cTnT (10, 29). Interestingly, the Δ160E mutation, a single in-frame deletion of glutamic acid 160 (also referred to as 163), is associated with an especially poor prognosis (2, 21, 24, 25). It is therefore unclear how a mutation located in the calcium-insensitive region of cTnT can cause such severe, highly penetrant disease. Several research groups have attempted to unravel the underlying biochemistry and biophysics of TNT1 C-terminal mutation, but no consensus has been reached (29–31). We previously investigated the functional effects of the Δ160E mutation in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo (13, 32–36). Regulated in vitro motility assay studies revealed a mutation-specific disruption of weak electrostatic actomyosin binding, which correlated to unique, progressive cardiac remodeling in vivo (32). Given these clinical and experimental observations, we aim to determine the earliest structural perturbation that could elicit these downstream affects. In the current study, we investigate the structural and dynamic alterations at the molecular level using TR-FRET and molecular dynamics simulation of the cardiac TF. We hypothesized that the Δ160E mutation changes the position of the adjacent cTnT flexible linker, impairing weak electrostatic actomyosin binding and acting as the biophysical trigger for the observed cardiac remodeling.

The goal of this study is 2-fold: 1) to gain high-resolution insight into the position of the WT cTnT linker with respect to the C terminus of Tm and 2) to identify Δ160E-induced positional changes using TR-FRET in a fully reconstituted cardiac TF. To this end, selected residues within the linker were sequentially cysteine-substituted and labeled with the energy donor IAEDANS (37). The energy acceptor DABMI was attached to cysteine 190 of Tm (Tm Cys-190), and TR-FRET measurements were obtained for WT and mutant thin filaments in different biochemical conditions (± calcium and ± myosin subfragment 1 (S1)) to probe for changes in weak actomyosin interactions in surrogates of the nucleotide-unbound “blocked,” “closed,” and “open” states (38–40). Molecular dynamics was used to predict the effects of the Δ160E mutation on the position and the flexibility of the cTnT linker region, and these data were correlated with our structural results. We present evidence that the position and the flexibility of the cTnT linker region are differentially affected in the presence of the Δ160E mutation. These studies, for the first time, provided information regarding the structural dynamics of the cTnT linker in both myofilament activation and disease.

Results

To gain insight into the structural role of linker region in TF activation and HCM pathogenesis, we performed TR-FRET between selected IAEDANS-labeled cysteine-substituted residues within the cTnT linker region (A168C, A177C, A192C, and S198C) and DABMI-labeled Tm Cys-190 (Fig. 1A) in fully reconstituted WT or mutant thin filaments under different biochemical conditions (−Ca/−S1, +Ca/−S1, or +Ca/+S1). The selected donor attachment sites, along the middle and distal linker, allowed us to triangulate the position of the linker along its length with respect to Tm. An NADH-coupled ATPase assay demonstrated that cysteine substitutions at these sites, without attached probes, result in normal TF function (Fig. S1). Our choice of Cys-190, the only endogenous cysteine in Tm, as a reference point for the linker's position was to minimize any structural/functional effects that might be caused by cysteine substitution of other Tm residues. Tm Cys-190 has been used extensively in previous FRET studies of the thin filament (37, 41, 42). To simplify FRET analysis, it is often assumed that the two Cys-190 residues at the C terminus of Tm are equidistant to donor or acceptor attachment sites on other proteins (in this case, IAEDANS-labeled residues within the linker region). It is unlikely that our TR-FRET measurements were confounded by the presence of Tm Cys-190 residues on the neighboring thin filament because they are outside the range of the Förster distance of the used FRET probes (the R0 for IAEDANS and DABMI was ∼40 Å). Analysis of R0 was performed as previously described in the literature (37), but no significant differences between different experimental sites were found for this experimental setup (data not shown).

Organization of the cTnT linker region in the WT thin filament

Using IAEDANS and DABMI as FRET probes (Förster distance (R0) = ∼40 Å (43)), we were able to gain insight into the organization of the middle and distal portions of the linker domain, which comprise ∼60% of the linker sequence with respect to a specific reference point (Cys-190) on the C terminus of Tm (Fig. 1A, inset). We found that in the WT cardiac TF, the average position of the linker is such that the distal region (residues A192C and S198C) is closer to the C terminus of Tm than the middle region (residues A168C and A177C), with A192C lying the closest to Tm (Fig. 1, B and C). The distances, averaged across biochemical conditions, of the WT cardiac TF linker, were 46.2 ± 1.1, 42.1 ± 1.4, 40.1 ± 0.9, and 41.4 ± 0.9 Å (A168C, A177C, A192C, and A198C, respectively) (Table 1). The purpose of averaging across biochemical conditions is to determine, when biochemical conditions are not considered statistically as a factor within the ANOVA, whether there were any over-riding effects of the Δ160E mutation on linker position (Figs. 1, A–C, and 2, A–C). The organization of the linker region inferred from TR-FRET distances were in agreement with the hypothetical representation of the cTnT linker in the TF model (Fig. 1A), and a recent EM reconstruction study, demonstrating the position of the TNT tail alongside Tm (44). However, this 3D reconstruction was a snapshot of a low-resolution TF in only the relaxed state (−calcium). Our studies, provided high-resolution atomic-level structural information on the linker region in a fully reconstituted cardiac TF under various biochemical conditions (± calcium, ± S1, ± Δ160E mutation).

Table 1.

Average position of the WT–cTnT linker

WT and Δ160E FRET distances (Å) ± S.D. averaged across calcium and myosin S1 status at each site (A169C, A177C, A192C, and A198C) with respect to Tm Cys-190. The results of one-way ANOVA with Sidak correction of average distances between sites (within genotype) and average distance change (between genotypes) are included.

| cTnT–A168C | cTnT–A177C | cTnT–A192C | cTnT–A198C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 46.2 ± 1.1 | 42.1 ± 1.4a | 40.1 ± 0.9a,b | 41.4 ± 0.9a,c |

| Δ160E | 44.9 ± 1.3d | 40.9 ± 1.3d | 40.1 ± 0.6 | 40.4 ± 0.7e |

ap < 0.0001 versus WT cTnT A168C.

b p < 0.0001 versus WT cTnT A177C.

c p < 0.0001 versus WT cTnT A192C.

dp < 0.005 versus WT.

e p < 0.01 versus WT.

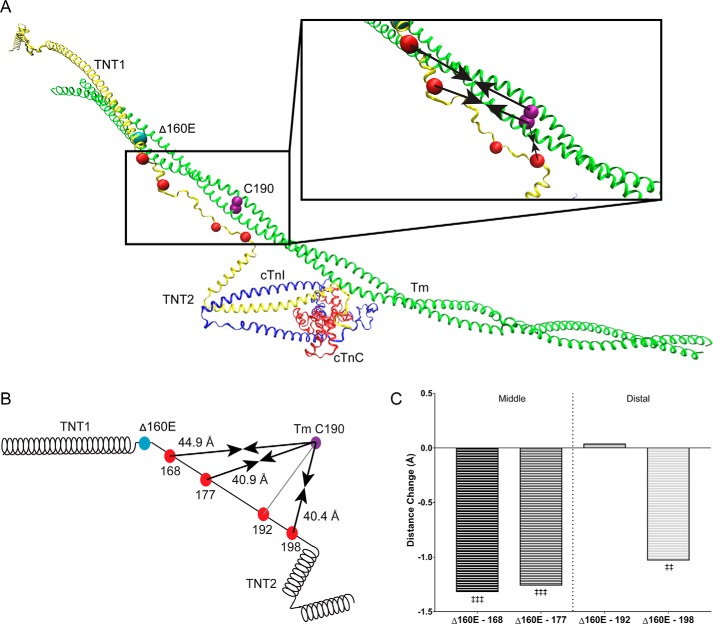

Figure 2.

Average position of the Δ160E-cTnT linker region. A, atomistic model of human cardiac thin filament components: troponin complex (cTnT, yellow; cTnI, blue; cTnC, red) and a single Tm dimer (green) with the position of the Δ160E mutation (cyan bead), FRET donor attachment sites (red beads), and FRET acceptor attachment site (purple bead). Inset, enlarged linker region. Black arrows indicate the change in the average distance between the donor and acceptor sites; arrows pointing inward indicate a decrease in distance. B, schematic representation of cTnT including the donor (red beads), acceptor (purple) sites, and arrows indicating the distance change caused by Δ160E. The distances reported reflect the average distance change (across calcium and myosin S1 status) of the Δ160E-linker region relative to Tm Cys-190 (Table 1). C, bar graph of the average distance change of each linker residue compared with WT separated into the middle and distal regions. The reported statistics are the results of a one-way ANOVA with Sidak correction. ‡‡, p < 0.01 versus WT; ‡‡‡, p < 0.005 versus average WT position.

Effect of calcium and myosin S1 on the WT linker region

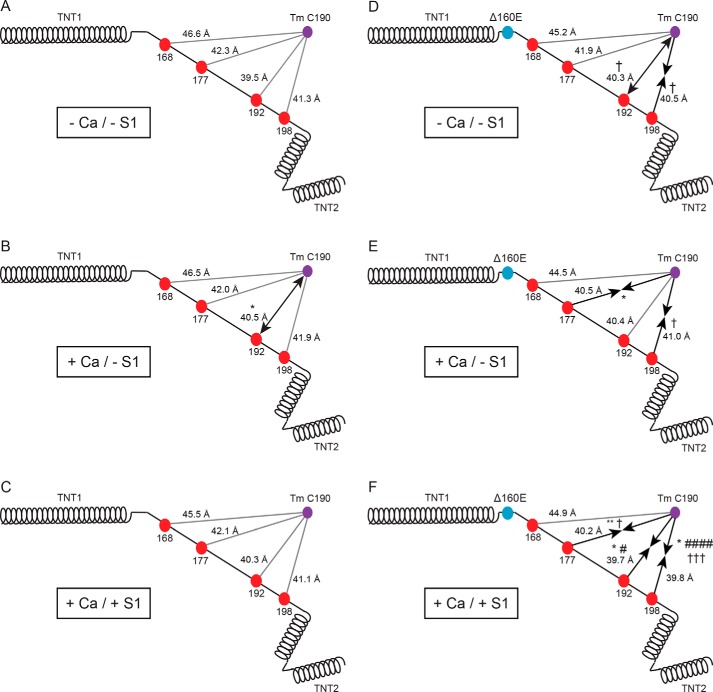

Our study design allowed us to probe the biophysical effect of calcium and nucleotide-unbound myosin S1 on the linker region (−Ca/−S1, +Ca/−S1, and +Ca/+S1) to mimic the blocked, closed, and open states, respectively. Notably, in each biochemical condition tested, there was little change in the position of the linker relative to Tm Cys-190 (Fig. 3, A–C). In order of increasingly distal residues (A168C, A177C, A192C, and A198C), the −Ca/−S1 condition distances from Tm Cys-190 were 46.6 ± 1.2, 42.3 ± 0.8, 39.5 ± 0.8, and 41.3 ± 0.8 Å (Table 2). With the addition of calcium (+Ca/−S1), the only statistically significant movement that occurred was an increase in distance of 1 Å at A192C (Fig. 3B and Table 2). A two-way ANOVA confirmed that there was no main effect of adding calcium at any of the sites in the WT linker region (see Table 4).

Figure 3.

Linker position with varying biochemical conditions. A–C, schematic representation of WT cTnT including the donor (red beads) and acceptor (purple beads) sites in the −Ca/−S1 (A), +Ca/−S1 (B), and +Ca/+S1 (C) biochemical conditions. D–F, schematic representation of Δ160E cTnT including the donor (red beads) and acceptor (purple beads) sites in the −Ca/−S1 (D), +Ca/−S1 (E), and +Ca/+S1 (F) biochemical conditions. Black arrows represent the direction of significant changes in distance; ←→ represents an increase in distance, →← represents a decrease in distance, and solid lines indicate no change. The statistics reported are the result of two-way ANOVA with Sidak correction of distances between three biochemical conditions (within genotype) and result of three-way ANOVA with Sidak correction of distances versus WT (between genotypes, within biochemical condition). Distances (means ± S.D.) measured under each condition can be found in Table 2. *, p < 0.05 versus −Ca/−S1 (within genotype); **, p < 0.01 versus −Ca/−S1 (within genotype); †, p < 0.05 versus WT (within biochemical condition); #, p < 0.05 versus +Ca/−S1 (within genotype); ####, p < 0.0001 versus +Ca/−S1 (within genotype); †††, p < 0.005 versus WT (within biochemical conditions).

Table 2.

TR-FRET distances in response to ±calcium and ±myosin S1

WT and Δ160E FRET distances ± S.D. in each of the three surrogate states. −Ca/−S1 indicates blocked, +Ca/−S1 indicates closed, and +Ca/+S1 indicates open. The results of two-way ANOVA with Sidak correction of distances between three states (within genotype) and the results of three-way ANOVA with Sidak correction of distances versus WT (between genotypes, within states) are shown.

| −Ca/−S1 |

+Ca/−S1 |

+Ca/+S1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Δ160E | WT | Δ160E | WT | Δ160E | |

| cTnT–A168C | 46.6 ± 1.2 | 45.2 ± 1.1 | 46.5 ± 1.1 | 44.5 ± 0.7 | 45.5 ± 0.8 | 44.9 ± 2.0 |

| cTnT–A177C | 42.3 ± 0.8 | 41.9 ± 0.9 | 42.0 ± 1.8 | 40.5 ± 1.5a | 42.1 ± 1.5 | 40.2 ± 0.7b,c |

| cTnT–A192C | 39.5 ± 0.8 | 40.3 ± 0.6c | 40.5 ± 1.0a | 40.4 ± 0.5 | 40.3 ± 0.4 | 39.7 ± 0.5a,d |

| cTnT–A198C | 41.3 ± 0.8 | 40.5 ± 0.3c | 41.9 ± 0.9 | 41.0 ± 0.5c | 41.1 ± 0.8 | 39.8 ± 0.6a,e,f |

ap < 0.05 versus −Ca/−S1 (within genotype).

bp < 0.01 versus −Ca/−S1 (within genotype).

c p < 0.05 versus WT (within state).

d p < 0.05 versus +Ca/−S1 (within genotype).

e p < 0.0001 versus +Ca/−S1 (within genotype).

f p < 0.005 versus WT (within state).

Table 4.

Result of two-way ANOVA main and interaction effects

For each genotype the main (calcium and myosin S1) and interaction effects are reported. NS, not significant.

| Main effect |

Interaction effect |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | S1 | Calcium × S1 | |

| WT | |||

| cTnT–A168C | NS | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A177C | NS | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A192C | NS | p = 0.06 | a |

| cTnT–A198C | NS | NS | NS |

| Δ160E | |||

| cTnT–A168C | NS | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A177C | b | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A192C | NS | c | NS |

| cTnT–A198C | NS | b | b |

ap < 0.01.

b p < 0.005.

c p < 0.005.

Nucleotide-unbound S1 was incorporated in our TR-FRET system to test the effect of strong myosin binding on the linker's position (+Ca/+S1). Although no longer a statistically significant increase compared with −Ca/−S1 at A192C, a significant interaction of myosin and calcium was found (see Tables 2 and 4). The distances in the +Ca/+S1 condition were 45.5 ± 0.8, 42.1 ± 1.5, 40.3 ± 0.4, and 41.1 ± 0.8 Å (Table 2). We found no other effect of S1 on the linker except at A192C in the distal region, where there was an interaction effect (calcium × S1) and a trending main effect of S1 (see Table 4). Although this finding is not direct evidence for S1 binding at the C-terminal end of the linker's distal region, the fact that the interaction with calcium and the trending main effect of S1 are limited to the distal region of the linker is interesting. It has been proposed that multiple myosin heads can bind per thin filament regulatory unit (∼3.9 S1: 7 actin monomers) (45). Thus, the possibility that at least one of the myosin heads bind near the cTn core domain is not to be excluded if myosin does bind to actin within the linker domain.

Organization of the cTnT linker region in the Δ160E thin filament

The Δ160E mutation induced a significant change in the position of the cTnT linker domain. The average effect of the Δ160E mutation was to shift the linker closer to Tm Cys-190, except at A192C, with an average decrease in distance between the FRET pairs of ∼1 Å compared with WT (Fig. 2, A–C). The distances, averaged across biochemical conditions (−Ca/−S1, +Ca/−S1, and +Ca/+S1) of the Δ160E TF linker were 44.9 ± 1.3, 40.9 ± 1.3, 40.1 ± 0.6, and 40.4 ± 0.7 Å (A168C, A177C, A192C, and A198C, respectively) (Table 1). Additionally, in agreement with the one-way ANOVA results on average distance, a three-way ANOVA main effect indicated a significant effect of genotype at all FRET pairs aside from A192C (Table 3). Notably, although there was no main effect of genotype found at A192C, an interaction of genotype and S1 and a trending effect of genotype and calcium was observed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Result of three-way ANOVA main and interaction effects

Pertinent main and interaction effects are reported where calcium status and/or myosin S1 status are averaged. Our experimental design excluded three-way main and interaction effects that averaged genotypes (calcium, myosin S1, myosin S1 × calcium) and the three-way interaction. NS, not significant.

| Main effect |

Interaction effect |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Genotype - S1 | Genotype × calcium | |

| cTnT–A168C | a | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A177C | b | NS | NS |

| cTnT–A192C | NS | a | p = 0.057 |

| cTnT–A198C | b | NS | NS |

ap < 0.01.

b p < 0.0001.

Effect of calcium and myosin on the Δ160E linker region

The position of the Δ160E thin filament linker was assessed, under differing biochemical conditions (−Ca/−S1, +Ca/−S1, and +Ca/+S1). The distances, in order of increasingly distal residues, from Tm Cys-190 of the Δ160E linker in the −Ca/−S1 condition were 45.2 ± 1.1, 41.9 ± 0.9, 40.3 ± 0.6, and 40.5 ± 0.3 Å (Table 2). In the −Ca/−S1 condition, the mutation induced significant structural changes at the distal end of the linker, where A192C increased distance and A198C decreased distance compared with WT (Fig. 3D). Of note, the mutationally induced change at A192C was similar to the effect of adding calcium to the WT linker and was the only instance of an increase in distance between any residues and Tm Cys-190 (Fig. 3, B and D).

The biophysical effect of the Δ160E mutation on the linker was assessed at maximally activating calcium. The distances, in the aforementioned order, for the +Ca/−S1 condition were 44.5 ± 0.7, 40.5 ± 1.5, 40.4 ± 0.5, and 41.0 ± 0.5 Å (Table 2). Although the addition of calcium had very little effect on the WT linker, the mutation decreased the distance at A198C versus WT in the +Ca/−S1 condition (Fig. 3E). Additionally, it abolished the calcium-induced increase in distance at A192C seen in WT filaments and decreased the distance of the middle region (A177C) compared with −Ca/−S1 (Fig. 3E).

To mimic the effect of strong binding of myosin to actin on the Δ160E linker distance, nucleotide-unbound myosin S1 heads were added at maximally activating calcium +Ca/+S1. The distances in the +Ca/+S1 condition (from A168C to A198C) were 44.9 ± 2.0, 40.2 ± 0.7, 39.7 ± 0.5, and 39.8 ± 0.6 Å (Table 2). In the +Ca/+S1 condition, there were significant decreases in distance of 1–2 Å at all sites except A168C, adjacent to the hinge, versus the WT linker as well as between conditions (versus −Ca/−S1 or +Ca/−S1) within the Δ160E linker (Fig. 3F). Specifically, at A177C, A192C, and A198C, there was a significant decrease in distance compared with Δ160E −Ca/−S1; at A192C and A198C, there was a significant decrease in distance compared with Δ160E +Ca/−S1; and at A177C and A198C, there was a significant decrease in distance compared with WT +Ca/+S1 (Fig. 3F). To gain additional resolution, the main and interaction effects of calcium and myosin on the Δ160E linker were assessed via two-way ANOVA (Table 4). In agreement with the reported FRET distances, main effects of calcium (at A177C) and myosin (at A192C and A198C) were found in the middle and distal linker, as well as an interaction effect at A198C (Table 4). Notably, although the +Ca/+S1 condition had no effect on the WT linker, the effect on the middle and distal regions (A177C, A192C, and A198C) in the presence of Δ160E was significant.

Molecular dynamics simulation of the WT and Δ160E linker region

To better understand the molecular causes of the observed experimental results (changes in FRET pair distance), we performed all atom molecular dynamics simulations on our recently published explicitly solvated model of the cardiac thin filament (46). The goal is to understand the molecular cause of the overall structural rearrangement found via the TR-FRET experiments.

The Δ160E-induced displacement of the cTnT linker was confirmed by the in silico model (Fig. 4A). Because the deletion occurs in a region with four contiguous glutamic acids (in fact some papers refer to the same clinical condition as being Δ163), there is no way to distinguish which actual amino acid is deleted. To ensure that our results were not contingent on a specific choice, we reprepared structures for the 160, 161, and 162 positions following our previously published methods and also described under “Experimental procedures.” The structures are fully minimized and equilibrated. We detected minimal differences in the starting structure given the random seed choice for the simulations. This is illustrated in Fig. S2, which contains the structures of the Δ160, Δ161, and Δ162 mutations following minimization and equilibration. Although not directly overlaid, they are clearly quite similar for all three of the deletions. To further investigate this issue, we performed dynamics simulations for the Δ162 mutation, and we compare it with that of Δ160. (We choose a single extra mutation because of the time required for the simulations.) This is shown in the supplementary information as Fig. S3. The average of the structures generated by the dynamics performed in the same way as the previous simulations reported for Δ160 clearly show the two mutations behave similarly. One cannot expect perfect overlap in two simulations of even the exact same mutation if performed with differing seeds, and these two results are within the variability expected for any single mutation.

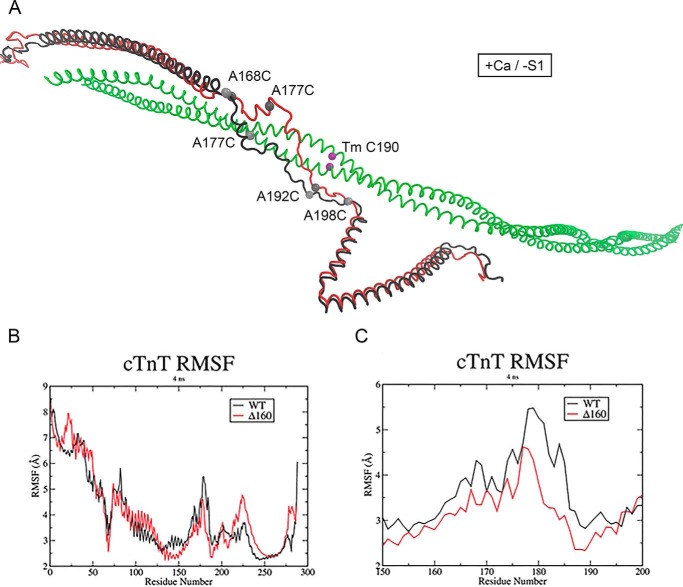

Figure 4.

Average in silico structure of the thin filament linker. A, WT (black) and Δ160E cTnT (red) in the +Ca/−S1 conditions. Acceptor site on tropomyosin (green) shown in purple, and donor sites on cTnT are shown in gray. B, RMSF analysis for cardiac troponin T. C, RMSF analysis of the cTnT linker region, cTnT residues 150–200, in the +Ca/−S1 conditions. WT and Δ160E RMSF are in black and red, respectively.

As illustrated in the average structures of WT and mutant cTnT (Δ160E; Fig. 4A), WT cTnT is purely α-helical at the N-terminal side of the mutation site. It then proceeds to a short unstructured linker to another short α-helical region before entering the long unstructured region. It does this in an essentially linear fashion. In the mutant protein, the loss of residue 160 causes a change in orientation of the short unstructured region, which in turn causes repositioning of the short α-helical section. Because the core domain is massive, this change “stretches” the unstructured region and brings it in closer proximity to Tm. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of cTnT demonstrated that the deletion of E160 from the TNT1 C-terminal hinge reduces the flexibility of the linker region (Fig. 4, B and C). The unidirectional shift of almost the entire middle and distal regions of the mutant linker closer to C terminus of Tm and the associated rigidity could impose steric hindrance on actin-myosin interaction by directly concealing weak myosin-binding sites on actin. In addition, the effect of Δ160E mutation extended beyond the linker region to the N- and C-terminal ends of cTnT. The average in silico structure demonstrated that both the TNT1 and TNT2 domains in the WT and mutant proteins were out of register (Fig. 4A).

Discussion

Tight regulation of cardiac muscle contraction depends on the precise function of thin filament proteins. The regulated movement of Tm along actin during thin filament activation has been well-established (47–49). However, the regulatory role of cTnT, including its interaction with Tm and F-actin, is poorly understood because of lack of high-resolution structural information on the TNT tail region, which comprises ∼70% of the cTnT sequence (11, 12, 44). The inherent flexibility of the TNT1 domain (approximately aa 70–157) and the cTnT linker (approximately aa 158–202) led to their exclusion from the calcium-activated crystal structure of human cTnT and subsequent EM studies (11, 12). In 2014, the 3D organization of the TNT1 domain on a native relaxed cardiac TF was published (44). Although this was a significant advance in our understanding, the structural details of the cTnT linker domain were not fully resolved (∼ 25 Å). The cTnT linker region structurally and functionally connects the TNT2 domain to the TNT1 domain and translates rising intracellular calcium levels to a sliding motion of the thick and thin filaments. The importance of the linker region is highlighted by its evolutionary conservation and the severity of the HCM causing-mutations within (34). The uniqueness of the primary sequence of the linker region complicates 3D structure prediction (32). Thus, prior to dissecting the molecular mechanism underlying the Δ160E mutation, we first attempted to gain a high-resolution insight into the structure of the cTnT linker under varying biochemical conditions (from weak to strongly bound: −Ca/−S1, +Ca/−S1, and +Ca/+S1), as surrogate states of the WT TF.

In agreement with the EM reconstruction of the position of the TNT tail alongside Tm, our in silico and in vitro results suggest that the position of the WT linker is along Tm, where the hinge turns the linker, and more distal linker residues lie closer to the Tm C terminus (Fig. 1A) (12). Interestingly, there was little to no effect of altering biochemical conditions on the position of the linker. These data could indicate that the flexible linker region is highly tolerant to changing biochemical conditions such that it maintains the relative position of the Tn core throughout the cardiac cross-bridge cycle. Notably, the only significant effects on distance are isolated to residue A192C in any of the tested conditions. We report an increase in distance at A192C in the +Ca/−S1 condition (Fig. 3, A–C) as compared with the −Ca/−S1 condition. Additionally, when we probed for main and interaction effects via two-way ANOVA, the only significant or trending significant effects were isolated to A192C in the presence of nucleotide-unbound myosin S1 heads (Table 4). Although not direct evidence, together these data suggest that a myosin-binding site could exist near the distal cTnT linker and that the addition of calcium initiates the necessary structural rearrangements for “priming” the linker for myosin binding.

It has been shown that the addition of calcium changes the regulatory N-terminal lobe of cTnC such that it exposes a buried hydrophobic patch, which favors the interaction with the switch peptide of cTnI (50). This interaction results in a series of conformational changes that release the mobile domain of cTnI and the neighboring inhibitory peptide from actin and subsequently moves Tm from the blocked to the closed to the open state (38, 51–53). Our findings suggest that the calcium-induced allosteric changes are transmitted to Tm via regulated displacement of the flexible cTnT linker region in the TF, such that the relative position of the core domain is maintained. The end result is formation of force-producing cross-bridges and muscle contraction. Our findings are consistent with a 3D EM reconstruction-based model proposed by the Lehman group (44). This model suggests that during relaxation, the TNT tail and Tm are held in the blocked position by the cTnI mobile domain, but this constraint is released upon calcium activation. The calcium-induced shift in the position of the distal linker at A192C is potentially a consequence of relieving the inhibitory effect of the cTnI mobile domain. The TR-FRET and EM reconstruction findings imply increased linker flexibility during activation. However, the effect of calcium on the flexibility of the cTnT linker could not be predicted computationally because a calcium-off (relaxed) model is not available to serve as a reference for the current calcium-on model.

The Δ160E mutation is located in a putative α-helical hinge (approximately aa 158–166) at the C terminus of TNT1 immediately adjacent to the unstructured linker domain (Fig. 2, A and B) (32). Mutations in the TNT1 N-terminal domain have been shown to affect cTnT-Tm binding; however, TNT1 C-terminal mutations (including the Δ160E mutation) have no effect on the Tm-dependent functions of TNT1, such as promoting actin–Tm binding and Tm head-to-tail overlap stability (10, 29). Previous studies have shown that the progressive remodeling associated with the Δ160E mutation (33) is likely the result of impaired calcium-dependent transition toward the closed state of TF activation (32). We hypothesized that the deletion of glutamic acid 160 changes the position of the cTnT linker region in the TF, which ultimately impairs weak electrostatic actomyosin binding. The hypothesis was based on earlier work proposing a change in the rotational orientation of residues in the α-helical Tm-binding TNT1 domain in response to 160E deletion (30). Moreover, dynamic simulation of the Δ160E mutation suggested that this mutation tightens the helix at the C terminus of TNT1, which increases the rigidity of the TNT1 domain and pulls on the linker (54).

Our results inform directly on how the Δ160E mutation likely causes dysfunction. The repositioning of the linker, closer to Tm on average with additive decreases in distance to Tm with changing biochemical conditions, could certainly affect the Tm-dependent properties of cTnT. It has been previously shown that TNT1 C-terminal mutations have no effect on the Tm–TNT1 binding affinity and the stability of the Tm overlap region (29). That study, however, utilized an isolated 100-aa-long fragment of cTnT, whereas the current study used a full-length cTnT in a reconstituted cardiac TF. The troponin core domain is relatively stationary with respect to actin, and the IT arm (which includes the coiled-coil portions of cTnI and cTnT) region of the core is a rigid stable structure that moves as a single unit (55). Our WT TR-FRET data fully support this, because the WT linker moved minimally with changing biochemical condition, thus maintaining the relative position of the core throughout contraction. We acknowledge a limitation of our study is that the orientation of the probes could affect our reported distances; thus the changes in distance are likely more relevant than the absolute values. However, a subtle change in the orientation of the TNT2 region can have significant effects on the structure and function of the core domain and hence TF activation. Previous studies demonstrated that subtle changes in local structure can result in the propagation of long-distance effects (54, 55). The structural effects reported here are yet another example of effect at a distance from mutation paradigm that is prevalent in thin filament-linked HCM.

The average position of the Δ160E linker indicates that it lies ∼1 Å closer to Tm along its length, except at residue A192C where its average position is unchanged (Fig. 2C). Of note, A192C is the residue that lies closest to Tm in the WT TF. Thus, the mutation is bringing the entire linker significantly closer to Tm. These decreases in distance between the two proteins are exacerbated in the face of changing biochemical conditions, suggesting a less flexible, or tolerant, linker (Fig. 3, D–F). These data match well with our computational results that suggest decreased linker flexibility. Indeed, unlike the WT thin filaments studied, TR-FRET on Δ160E in the +Ca/−S1 condition revealed significant decreases in distance with no increase at site A192C, which represented the only statistically significant movement of the WT linker. This loss of an increased distance of A192C upon addition of calcium is likely due to the mutation increasing the distance at that site from baseline (−Ca/−S1), a change that is then maintained upon adding calcium (Fig. 3, D and E). Thus, the effect of the mutation could be putting the TF proteins in an unfavorable position at baseline, thereby minimizing the structural effects of the addition of calcium at the onset of contraction.

Our studies of the incorporation of nucleotide-unbound myosin S1 heads into the reconstituted cardiac TF show that the effect of the Δ160E mutation on the separation between the middle and distal region of the linker and the C terminus of Tm was most pronounced in the presence of S1 (+Ca/+S1). In this condition all of the residues, except A168C proximal to the mutation, had significant decreases in their distance to Tm compared across biochemical conditions and genotype. Such changes in distance could explain the impaired weak myosin binding demonstrated in the regulated in vitro motility study (32). As previously mentioned, multiple myosin heads can bind per TF unit not necessarily limited to the core domain (45, 56). Thus, a disruption in the normal increase in distance (A192C) upon addition of calcium in WT thin filaments and a decrease in distance (A177C, A192C, and A198C) along the middle and distal linker when S1 is present could impair TF access for myosin binding. Of note, weak and rigor binding could be independent from each other to some extent. We previously reported that that disruption of weak myosin binding by the Δ160E mutation does not inhibit rigor binding (32). In addition, it has been reported that some of the weak myosin-binding sites on actin are not used in rigor binding (47). Information about the distance changes in other myosin S1 states (e.g. nucleotide-bound) could further support these observations. More insight into S1 binding in WT and mutant thin filaments could not be obtained computationally, because the TF model is devoid of S1.

In summary, we employed an integrative in vitro, in silico approach to provide high-resolution structural insights into a structurally and functionally crucial region of cTnT under physiological and pathological conditions. We presented evidence that the linker region, whose position is relatively stable regardless of biochemical condition, is repositioned differentially in thin filaments containing the Δ160E mutation. Furthermore we have shown that this effect is more pronounced in the presence of myosin S1 heads at the distal end, supportive of a myosin-binding site. The repositioning of the linker in the calcium-activated (+Ca/−S1) and mutant thin filaments is associated with increased and decreased flexibility, respectively. Together, these data could indicate that the “stretching” of the linker in response to the loss of residue Glu-160 reduces its flexibility such that changes in biochemical condition are transmitted to the core. These effects reposition the linker in a sterically unfavorable manner that alters the regulatory capacity of the TF. These findings provide a new framework for understanding the basic mechanisms of how mutations drive TF dysfunction in HCM and points the way to identifying structural targets for intervention that can be tested via both in silico and in vitro approaches.

Experimental procedures

Site-directed mutagenesis

Δ160E mutation was introduced into human cTnT (hcTnT) cDNA subcloned into pET3D expression vector. To execute TR-FRET experiments, single-cysteine variants (A168C, A177C, A192C, and S198C) were generated from WT and Δ160E hcTnT protein clones using QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The identity of each clone was verified by the University of Arizona Genetics Core via direct DNA sequencing.

Human cTnT, cTnI, cTnC, and Tm purification

All clones were provided by J. D. Potter (University of Miami). Recombinant hcTnT clones were transformed into Rosetta (DE3) competent cells (Novagen, EMD, Millipore), whereas WT hcTnI, WT hcTnC and Ala–Ser α-Tm cDNA in pET3D vectors were transformed into BL21 (DE3) cells (Agilent Technologies). To express hcTnI, hcTnC, and Tm protein, LB-ampicillin agar plates were streaked with transformed BL21 cells. 2 liters of overnight express TB medium with ampicillin was inoculated with 1–2 ml of LB-ampicillin starter culture and grown at 37 °C overnight with shaking. To express hcTnT, TB medium was substituted with ZYP medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast, 0.5% (w/v) glycerol, 0.05% glucose, and 0.2% lactose) and supplemented with 5% 20× P-buffer (1 m Na2HPO4, 1 m KH2PO4, 0.5 m (NH4)2SO4),1 mm MgSO4, and ampicillin. Bacterial cells were centrifuged at 2204 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. For hcTnT, the bacterial pellet was resuspended in S-Sepharose buffer (6 m urea, 50 mm Tris, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.0) and then sonicated on ice for 30 s × 10 with 2-min pauses using an Ultrasonic cell disruptor, Microson XL-2000 (Misonix). All remaining steps were done at 4 °C, unless otherwise noted. Following centrifugation (23,281 × g for 30 min), the collected supernatant was loaded on SP-Sepharose column (Sigma; packed in a Bio-Rad Econo-Column with a 100-ml bed volume) pre-equilibrated with at least 1 liter of S-Sepharose buffer. The loaded column was washed with 1–1.5 liters of S-Sepharose buffer prior to eluting hcTnT protein with a linear gradient of 0–0.6 m KCl in S-Sepharose. Pure hcTnT fractions were determined via Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel, pooled, and dialyzed overnight against 2 × 2 liters of Q-Sepharose buffer (6 m urea, 20 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 0.3 mm DTT, pH 7.8). Dialyzed protein was loaded on a pre-equilibrated Q-Sepharose column (Sigma; packed in a Bio-Rad Econo-Column with a 100-ml bed volume), washed, and eluted with 0–0.5 m NaCl in Q-Sepharose buffer. Finally, pure hcTnT fractions were pooled and stored at −80 °C.

hcTnC was purified on Q-Sepharose column as previously described and eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.6 m KCl. Pooled pure fractions were dialyzed against 2 × 2 liters of phenyl-Sepharose buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.5). Dialyzed protein was loaded at room temperature onto a phenyl-Sepharose column (Sigma; packed in a Bio-Rad Econo-Column with a 100-ml bed volume) pre-equilibrated with phenyl-Sepharose buffer A + 0.5 m (NH4)2SO4. After washing the column with the same buffer, hcTnC was eluted with phenyl-Sepharose buffer C (50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.5 m (NH4)2SO4, pH 7.5), and pure fractions were stored at −80 °C.

hcTnI was purified on an SP-Sepharose column and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–0.6 m KCl. Pure fractions were dialyzed against 2 × 2 liters of TnC affinity buffer (50 mm Tris, 2 mm CaCl2, 0.5 m NaCl, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.5). Dialyzed hcTnI was then purified using pre-equilibrated TnC affinity column prepared by the manufacturer's protocol for conjugating proteins to a cyanogen bromide–activated Sepharose 4B gel (Sigma) and packed in an Econo-Column (Bio-Rad). The column was washed with two or three column volumes of TnC affinity buffer, and the protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0 mm EDTA, 0 m urea to 3 mm EDTA, and 6 m urea. Pure fractions were pooled and stored at −80 °C.

Ala–Ser α Tm in pET3D vector was overexpressed in BL21 cells and purified through a series of acid/base cuts as follows: Tm bacterial pellet suspension in double-distilled H2O was briefly digested with 0.01% lysozyme at room temperature. The mixture was kept on ice for 1 h followed by 10 min at −80 °C. After adding solid NaCl to 1 m final concentration, the suspension was sonicated for 3 min three times, with 3-min interval between each pulse, followed by centrifugation at 30,996 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. The collected supernatant was boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at 23,281 × g for 20 min at 4 °C after reaching room temperature. To precipitate Tm, Tris base (pH 5.2) was added to the clarified supernatant to a final concentration of 20 mm, and the pH was slowly adjusted to 4.6. Next, the sample was centrifuged at 23,281 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the resulting protein pellet was dissolved in 1 m KCl by adjusting the mixture to pH 7–8. The suspended pellet was then clarified by centrifugation at 23,281 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The Tm precipitation and suspension procedure was repeated three or four times or until the protein was clear and free of DNA contamination.

hcTnT and Tm labeling

To prepare for labeling, 1–2 mg/ml proteins were dialyzed three times for 6–8 h against labeling buffer (3 m urea buffer (20 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8, 0.15 m KCl, pH 7.4) for Tm and 6 m urea buffer (50 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8, 0.15 m KCl, pH 7.4) for cTnT) with 50 μm DTT. cTnT and Tm were labeled with 15-fold molar excess IAEDANS (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 30 min and 60-fold molar excess DABMI (Setareh Biotech) for 2 h, respectively. The dyes were dissolved in dimethylformamide and added dropwise, while slowly stirring the proteins at room temperature. The labeling reaction was continued overnight at 4 °C and then terminated with 3–5 mm DTT. To remove excess dye, labeled proteins were centrifuged at 23,281 × g for at least 45 min at 4 °C, followed by dialysis against labeling buffer with 1 mm DTT. The concentrations of labeled proteins were determined spectroscopically (DU®730 Life Science UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter)) using a molar extinction coefficient of 5,900 m−1 cm−1 at 340 nm for IAEDANS. An extinction coefficient of 49,600 m−1 cm−1 at 460 nm was used for DABMI because of the dimeric nature of Tm. Labeling ratio for all proteins was >80%.

Actin and myosin purification

All experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arizona. Steps of actin and myosin purification from rabbit skeletal muscles were performed at 4 °C unless otherwise noted. To purify actin, acetone powder was prepared from minced muscle by extracting proteins with three volumes of Guba-Straub solution (0.3 m KCl, 0.1 m KH2PO4, 0.05 m K2HPO4, pH 6.5) for 20 min with gentle stirring. After brief centrifugation, the residue was resuspended in five volumes of 0.4% NaHCO3, 0.1 mm Ca2+ solution, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min prior to vacuum filtration. The resulting residue was resuspended in equivalent volumes of 10 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm Na2CO3, 0.1 mm Ca2+ solution with gentle stirring for 10 min, diluted with 10 volumes of room temperature H2O, and filtered immediately. The collected residue was resuspended in two volumes of cold acetone and stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The filtered residue was subjected to acetone treatment four times and allowed to dry overnight at room temperature prior to storing at −80 °C.

To generate F-actin, actin acetone powder was extracted for 30 min twice using buffer A (10 mm Tris, 0.2 mm CaCl2, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.2 mm DTT, pH 8.0). The filtered and clarified supernatant was polymerized with 0.05 m KCl followed by 2 mm MgCl2 for 1 h at room temperature. Next, solid KCl was gradually added to a final concentration of 0.6 m to slowly stirring actin over a period of 1.5 h at 4 °C. The polymerized actin was then centrifuged at 23,281 × g for 8 h, and the pellet was completely homogenized and dialyzed in buffer A (24 h three times) to depolymerize into G-actin. G-actin was then clarified by centrifugation and finally polymerized with 0.05 m KCl followed by 2 mm MgCl2 for 1 h at room temperature.

Myosin was purified from rabbit skeletal muscle as previously described (57) and then stored in a 50% glycerol solution at −20 °C. S1 from the chymotryptic digestion of myosin was prepared as follows. First, myosin glycerol stock was mixed with 9× volume ice-cold BED solution (0.1 mm NaHCO3, 0.1 mm EGTA, and 1 mm DTT) and incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifuging the mixture (23,281 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), the pellet was completely dissolved in CT-S1 solution (120 mm NaCl, 20 mm NaPO4,1 mm EDTA, pH 7) to a final concentration of 15 mg/ml using a 25 °C water bath. The suspended pellet was then diluted with 1 mg/ml chymotrypsin in 1 mm HCl solution to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Chymotryptic digestion was stopped after 10–15 min with stop solution (BED + 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and the resulting mixture was incubated on ice for 40–45 min. To remove light meromyosin and undigested myosin, the ice-cold solution was centrifuged (for 40 min at 23,281 × g at 4 °C), and the collected supernatant was dialyzed against working buffer overnight at 4 °C. S1 is stored at 4 °C on ice for use in TR-FRET experiments up to 1 week.

Recombinant cTn complex and thin filament reconstitution

IAEDANS-cTnT, cTnC and cTnI were individually dialyzed against 6 m urea solution (6 m urea, 0.5 m KCl, 50 mm MOPS, 1.25 mm MgCl2, 1.25 mm CaCl2, 1.5 m DTT, pH 7) prior to mixing at a molar ratio of 1:1.2:1.2, respectively. To fold the proteins into a Tn complex, the mixture was sequentially dialyzed against solutions containing 50 mm MOPS, 1.25 mm MgCl2, 1.25 mm CaCl2, 1.5 mm DTT, pH 7, and 1) 6 m urea + 0.5 m KCl; 2) 4 m urea + 0.5 m KCl; 3) 2 m urea + 0.5 m KCl; or 4) 0 m urea + 0.5 m KCl. Tn complex, Tm (unlabeled, DABMI-labeled), and F-actin were then individually dialyzed in 0 m urea, 0.4 m KCl solution and reconstituted into thin filament at a molar ratio of 1:1:7.5. Finally, the filaments were then dialyzed 6–8 h twice against working buffer (0.15 m KCl, 50 mm MOPS, 5 mm NTA, 2 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.0) and diluted in the same buffer to a final concentration of 1 μm. Nucleotide-unbound S1 was added to reconstituted thin filaments at 3 S1:7 actin molar ratio.

Thin filament reconstitutions, TF −Ca/−S1 and TF −Ca/+S1, were prepared three times, and each N represents a sample prepared from one of these reconstitutions. The samples were prepared in this fashion to maintain the correct cTn:Tm:actin:S1 ratios. Baseline FRET measurements were taken from each of these preparations, calcium was added (to a free concentration of 1 mm), and measurements were retaken on the same samples now TF +Ca/−S1 and TF +Ca/+S1.

Steady-state NADH-coupled ATPase activity

Steady-state heavy meromyosin activities were measured in reconstituted cardiac TFs with either WT or cysteine-substituted cTnT (A168C, A177C, A192C, and A198C) by a NADH-coupled assay. This assay functions based on the coupling of ATP hydrolysis to ATP regeneration via the oxidation of NADH. This protocol was adapted from other work (58, 59). Briefly, thin filaments were reconstituted as described above in the following ratios: 4 μm F-actin, 0.8 μm Tn, 0.7 μm Tm, and 1 μm heavy meromyosin in low ionic strength ATPase buffer (10 mm KCl, 4 mm MgCl2, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6). Each reaction also contained 2 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.3 mm NADH, 38 units/ml pyruvate kinase, and 50 units/ml lactate dehydrogenase, comprising the regeneration system. ATPase activity was initiated upon addition of 2 mm Mg2+-ATP to the solution. The reactions were carried out at room temperature, and the absorbance of NADH at 340 nm (A340) was monitored over a maximum of 20 min in a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter DU730). ATP hydrolysis rates for individual trials were calculated from the negative slopes of the decrease in A340 divided by the extinction coefficient for NADH (6,220 m−1 cm−1) to yield units of moles ATP per minute. Rates for each mutation as well as for controls were calculated either in the presence of 50 μm calcium or in the absence of calcium (1 mm EGTA). Fold change of ATPase rates from baseline (− calcium) to calcium-saturated filaments were reported. Fig. S1 shows the means ± S.E. of the fold change (− calcium) for each of the cysteine substitutes compared with WT cTnT.

Time-resolved FRET measurements

TR-FRET measurements were acquired using methods previously described in the literature (37). The following is a brief recap of the experimental setup and analysis. ISS ChronosBH system equipped with 340-nm LED source. The LED signal was passed through a 340-nm bandpass filter to excite the sample. The emission light was passed through a 390-nm-long pass filter and collected with a Hamamatsu H7422 detector. The pulse repetition rate was 10 MHz. The system was set to 10 °C and cooled with a Julabo cooling system. To acquire an instrument response function, the emission from a dilute ludox solution was acquired through a 340-nm band pass filter. The data were analyzed using FargoFit, a global analysis software developed by Igor Negrashov (60). The donor only decay is fit to a sum of exponentials (Equation 1), with n as the number of exponentials, Ai as a constant, t as time, and τDi as a decay constant of each exponential.

| (Eq. 1) |

It is then assumed that decay rate of each of these exponentials is increased in response to a nearby acceptor, with R0 being the distance at 50% energy transfer (Equation 2).

| (Eq. 2) |

The model used was derived from Kimura-Sakiyama et al. (42). This model takes into account three populations in the fluorescent decay: 1) a portion of the sample where the donor is not undergoing FRET, 2) a portion of the sample undergoing FRET with an acceptor on one of the Tm monomers, and 3) a third population undergoing FRET with acceptors attached to both Tm monomers. This model was used earlier to determine FRET between a donor on TnT and acceptors on Tm, similar to this system (42). TR-FRET measurements of donor only and donor acceptor were performed ± calcium and ± S1 (n = 6–12). Fig. S4 shows representative fluorescence decay for WT cTnT A168C-Tm Cys-190 under different biochemical conditions.

Statistical Analysis

All values are reported as means ± S.D., unless otherwise noted. The data were analyzed using three-way, two-way, and one-way ANOVA with Sidak (three- and two-way), and Tukey (one-way) correction for multiple comparisons (MCs). To avoid confounding our data interpretation, statistical analysis was performed as follows: to analyze the overall position of the linker (regardless of biochemical condition, for each genotype separately) a one-way ANOVA was performed. Within the one-way ANOVA, MCs were used to determine whether average Δ160E linker distances were different from WT. To analyze the effect of biochemical condition on the linker position, a two-way ANOVA was utilized for WT and Δ160E separately. Within the two-way ANOVA, MCs were used to determine the effects at each residue under each condition. Finally, to analyze the effect of the Δ160E mutation at each residue under all conditions, a three-way ANOVA was utilized. Here, for simplicity, the only MCs used were to compare WT to Δ160E. Statistical significance of the physiologically relevant main (genotype, calcium, and myosin) and interaction (genotype × myosin, genotype × calcium, and calcium × myosin) effects, determined prior to analysis, are reported in Tables 3 and 4 for the three- and two-way ANOVAs, respectively. Statistical significance reported in all other tables are the result of MC. In addition to Sidak and Tukey correction, no more than four MCs were made to test hypotheses to control the false discovery rate. All analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism, version 7.03 (2018). A level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation of the improved TF model was performed by Williams et al. (46). The WT and Δ160 models were created in the same manner as our previous model (46). In particular, mutations are introduced in the following way: all simulations begin from a low-temperature, fully docked model of the cardiac thin filament. To incorporate a deletion mutation at residue i in the structure, the atomic coordinates for residue i are deleted with the backbone nitrogen of residue i − 1 being bonded to the backbone carboxyl carbon of residue i + 1. This irregular backbone bond, as well as any other possible changes in secondary structure, is resolved through unconstrained minimization runs and unconstrained heating and equilibration runs at the desired temperature. In this work, the overlap region of Tm was altered to conform to the most recently available structural information (37, 61). This was deemed crucial because this region is directly involved in the studies described.

The molecular dynamics were calculated using NAMD2.9 (62) with the CHARMM27 force field parameters (63). The Δ160 model was created from the WT model exactly as detailed by Williams et al. (46), who we reported on the effects of mutations at the 92 position of cTnT. All choices for heating, equilibration, and run times are the same as we have published previously. The WT and Δ160 models were minimized for 5000 steps. Periodic boundary positions were utilized with the cell size of the originally created box held fixed. The wrapAll feature was turned on. The particle-mesh Ewald method of calculating long-range electrostatic interactions was used, whereas the Van der Waals interactions were cut off at 12 Å. The particle-mesh Ewald grid spacing was set to 1.0 Å, and the tolerance was set to 10−6. The SHAKE algorithm was utilized to constrain the hydrogen lengths with a tolerance of 1.0–8 Å. The models were then heated to 300 K by increasing the temperature 1 K every 1 ps. The heating lasted for 310 ps to ensure the average temperature of the system reached 300 K. The models were equilibrated for 690 ps in an isothermal–isobaric ensemble. The Langevin piston was used to maintain the pressure at 1 aTm, whereas the Langevin temperature control maintained 300 K. Each production run is started from the equilibrated structures with random velocities with a 2-fs time step and previous settings.

The RMSF of the cTnT was calculated by the RMSF program of VMD1.92 (64). The RMSF for each production run is calculated for the positions of the Cα for each residue. The results were then averaged to produce one value for each residue. The average structure was created utilizing the average structure program of the trajectory_smooth script of the VMD Script Library. The trajectories for each production run were averaged before averaging the averaged structures.

To validate the use of WT thin filament models as valid comparisons to cysteine-substituted systems, we also performed a molecular dynamics simulation on an all-FRET pair. Both RMSF for the entire cTnT subunit and actual FRET pair distances were monitored, and the results are given in the supplementary information (Fig. S5 and S6). The results show that the cysteine mutants yield both data within the envelope of fluctuations of the WT and so do not affect the conclusions of the study.

Author contributions

S. A., M. T. M., S. D. S., and J. C. T. conceptualization; S. A., M. L. L., M. T. M., M. M. K., and A. P. B. data curation; S. A., M. L. L., M. T. M., and M. M. K. formal analysis; S. A. validation; S. A., M. L. L., M. T. M., M. M. K., and A. P. B. investigation; S. A., M. L. L., M. T. M., M. M. K., A. P. B., and J. C. T. methodology; S. A., M. L. L., M. T. M., S. D. S., and J. C. T. writing-original draft; S. A., S. D. S., and J. C. T. project administration; S. A., M. L. L., M. M. K., S. D. S., and J. C. T. writing-review and editing; M. L. L. visualization; S. D. S. and J. C. T. supervision; S. D. S. and J. C. T. funding acquisition; J. C. T. resources; J. C. T. software.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL075619 (to J. C. T. and S. D. S.) and Gootter Foundation support (to J. C. T.). We also acknowledge funding from Kuwait University faculty of Medicine (to S. A.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S6.

- HCM

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- cTn

- cardiac ternary troponin

- cTnT

- cardiac troponin T

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- TF

- thin filament

- TR

- time-resolved

- Tm

- tropomyosin

- cTnI

- cardiac troponin I

- cTnC

- cardiac troponin C

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- RMSF

- root-mean-square fluctuation

- hcTnT

- human cTnT

- S1

- myosin subfragment 1

- MC

- multiple comparison

- IAEDANS

- 5-((((2-iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino)napthelene-1-sulfonic acid

- DABMI

- 4-dimethylaminophenylazophenyl-4′-maleimide.

References

- 1. Maron B. J., and Maron M. S. (2013) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 381, 242–255 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alcalai R., Seidman J. G., and Seidman C. E. (2008) Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from bench to the clinics. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 19, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kimura A. (2015) Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alfares A. A., Kelly M. A., McDermott G., Funke B. H., Lebo M. S., Baxter S. B., Shen J., McLaughlin H. M., Clark E. H., Babb L. J., Cox S. W., DePalma S. R., Ho C. Y., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E., et al. (2015) Results of clinical genetic testing of 2,912 probands with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: expanded panels offer limited additional sensitivity. Genet. Med. 17, 880–888 10.1038/gim.2014.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Homsher E., Kim B., Bobkova A., and Tobacman L. S. (1996) Calcium regulation of thin filament movement in an in vitro motility assay. Biophys. J. 70, 1881–1892 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79753-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sehnert A. J., Huq A., Weinstein B. M., Walker C., Fishman M., and Stainier D. Y. (2002) Cardiac troponin T is essential in sarcomere assembly and cardiac contractility. Nat. Genet. 31, 106–110 10.1038/ng875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nishii K., Morimoto S., Minakami R., Miyano Y., Hashizume K., Ohta M., Zhan D. Y., Lu Q. W., and Shibata Y. (2008) Targeted disruption of the cardiac troponin T gene causes sarcomere disassembly and defects in heartbeat within the early mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 322, 65–73 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schaertl S., Lehrer S. S., and Geeves M. A. (1995) Separation and characterization of the two functional regions of troponin involved in muscle thin filament regulation. Biochemistry 34, 15890–15894 10.1021/bi00049a003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takeda S., Kobayashi T., Taniguchi H., Hayashi H., and Maéda Y. (1997) Structural and functional domains of the troponin complex revealed by limited digestion. Eur. J. Biochem. 246, 611–617 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harada K., and Potter J. D. (2004) Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations from different functional regions of troponin T result in different effects on the pH and Ca2+ sensitivity of cardiac muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14488–14495 10.1074/jbc.M309355200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takeda S., Yamashita A., Maeda K., and Maéda Y. (2003) Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca2+-saturated form. Nature 424, 35–41 10.1038/nature01780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pirani A., Vinogradova M. V., Curmi P. M., King W. A., Fletterick R. J., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Xu C., Hatch V., and Lehman W. (2006) An atomic model of the thin filament in the relaxed and Ca2+-activated states. J. Mol. Biol. 357, 707–717 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandra M., Tschirgi M. L., and Tardiff J. C. (2005) Increase in tension-dependent ATP consumption induced by cardiac troponin T mutation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H2112–H2119 10.1152/ajpheart.00571.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coppini R., Ho C. Y., Ashley E., Day S., Ferrantini C., Girolami F., Tomberli B., Bardi S., Torricelli F., Cecchi F., Mugelli A., Poggesi C., Tardiff J., and Olivotto I. (2014) Clinical phenotype and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with thin-filament gene mutations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 2589–2600 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anan R., Greve G., Thierfelder L., Watkins H., McKenna W. J., Solomon S., Vecchio C., Shono H., Nakao S., and Tanaka H. (1994) Prognostic implications of novel β cardiac myosin heavy chain gene mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 280–285 10.1172/JCI116957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fujino N., Shimizu M., Ino H., Okeie K., Yamaguchi M., Yasuda T., Kokado H., and Mabuchi H. (2001) Cardiac troponin T Arg92Trp mutation and progression from hypertrophic to dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin. Cardiol. 24, 397–402 10.1002/clc.4960240510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Driest S. L., Ellsworth E. G., Ommen S. R., Tajik A. J., Gersh B. J., and Ackerman M. J. (2003) Prevalence and spectrum of thin filament mutations in an outpatient referral population with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 108, 445–451 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080896.52003.DF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ackerman M. J., VanDriest S. L., Ommen S. R., Will M. L., Nishimura R. A., Tajik A. J., and Gersh B. J. (2002) Prevalence and age-dependence of malignant mutations in the β-myosin heavy chain and troponin T genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive outpatient perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39, 2042–2048 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01900-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Varnava A. M., Elliott P. M., Baboonian C., Davison F., Davies M. J., and McKenna W. J. (2001) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: histopathological features of sudden death in cardiac troponin T disease. Circulation 104, 1380–1384 10.1161/hc3701.095952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moolman-Smook J. C., De Lange W. J., Bruwer E. C., Brink P. A., and Corfield V. A. (1999) The origins of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in two South African subpopulations: a unique profile of both independent and founder events. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 1308–1320 10.1086/302623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watkins H., McKenna W. J., Thierfelder L., Suk H. J., Anan R., O'Donoghue A., Spirito P., Matsumori A., Moravec C. S., and Seidman J. G. (1995) Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and α-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 1058–1064 10.1056/NEJM199504203321603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Otsuka H., Arimura T., Abe T., Kawai H., Aizawa Y., Kubo T., Kitaoka H., Nakamura H., Nakamura K., Okamoto H., Ichida F., Ayusawa M., Nunoda S., Isobe M., Matsuzaki M., et al. (2012) Prevalence and distribution of sarcomeric gene mutations in Japanese patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. J. 76, 453–461 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koga Y., Toshima H., Kimura A., Harada H., Koyanagi T., Nishi H., Nakata M., and Imaizumi T. (1996) Clinical manifestations of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with mutations in the cardiac β-myosin heavy chain gene or cardiac troponin T gene. J. Card. Fail. 2, S97–S103 10.1016/S1071-9164(96)80064-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Torricelli F., Girolami F., Olivotto I., Passerini I., Frusconi S., Vargiu D., Richard P., and Cecchi F. (2003) Prevalence and clinical profile of troponin T mutations among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in tuscany. Am. J. Cardiol. 92, 1358–1362 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Capek P., and Skvor J. (2006) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: molecular genetic analysis of exons 9 and 11 of the TNNT2 gene in Czech patients. Methods Inf. Med. 45, 169–172 10.1055/s-0038-1634062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Millat G., Bouvagnet P., Chevalier P., Dauphin C., Jouk P. S., Da Costa A., Prieur F., Bresson J. L., Faivre L., Eicher J. C., Chassaing N., Crehalet H., Porcher R., Rodriguez-Lafrasse C., and Rousson R. (2010) Prevalence and spectrum of mutations in a cohort of 192 unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 53, 261–267 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pasquale F., Syrris P., Kaski J. P., Mogensen J., McKenna W. J., and Elliott P. (2012) Long-term outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the cardiac troponin T gene. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 5, 10–17 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.959973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richard P., Charron P., Carrier L., Ledeuil C., Cheav T., Pichereau C., Benaiche A., Isnard R., Dubourg O., Burban M., Gueffet J. P., Millaire A., Desnos M., Schwartz K., Hainque B., et al. (2003) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation 107, 2227–2232 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palm T., Graboski S., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E., and Greenfield N. J. (2001) Disease-causing mutations in cardiac troponin T: identification of a critical tropomyosin-binding region. Biophys. J. 81, 2827–2837 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75924-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harada K., Takahashi-Yanaga F., Minakami R., Morimoto S., and Ohtsuki I. (2000) Functional consequences of the deletion mutation deltaGlu160 in human cardiac troponin T. J. Biochem. 127, 263–268 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sweeney H. L., Feng H. S., Yang Z., and Watkins H. (1998) Functional analyses of troponin T mutations that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: insights into disease pathogenesis and troponin function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14406–14410 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore R. K., Abdullah S., and Tardiff J. C. (2014) Allosteric effects of cardiac troponin TNT1 mutations on actomyosin binding: a novel pathogenic mechanism for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 552–553, 21–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moore R. K., Grinspan L. T., Jimenez J., Guinto P. J., Ertz-Berger B., and Tardiff J. C. (2013) HCM-linked 160E cardiac troponin T mutation causes unique progressive structural and molecular ventricular remodeling in transgenic mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 58, 188–198 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jimenez J., and Tardiff J. C. (2011) Abnormal heart rate regulation in murine hearts with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related cardiac troponin T mutations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H627–H635 10.1152/ajpheart.00247.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crocini C., Ferrantini C., Scardigli M., Coppini R., Mazzoni L., Lazzeri E., Pioner J. M., Scellini B., Guo A., Song L. S., Yan P., Loew L. M., Tardiff J., Tesi C., et al. (2016) Novel insights on the relationship between T-tubular defects and contractile dysfunction in a mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 91, 42–51 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haim T. E., Dowell C., Diamanti T., Scheuer J., and Tardiff J. C. (2007) Independent FHC-related cardiac troponin T mutations exhibit specific alterations in myocellular contractility and calcium kinetics. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 42, 1098–1110 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.03.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McConnell M., Tal Grinspan L., Williams M. R., Lynn M. L., Schwartz B. A., Fass O. Z., Schwartz S. D., and Tardiff J. C. (2017) Clinically divergent mutation effects on the structure and function of the human cardiac tropomyosin overlap. Biochemistry 56, 3403–3413 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McKillop D. F., and Geeves M. A. (1993) Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 65, 693–701 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mijailovich S. M., Nedic D., Svicevic M., Stojanovic B., Walklate J., Ujfalusi Z., and Geeves M. A. (2017) Modeling the actin·myosin ATPase cross-bridge cycle for skeletal and cardiac muscle myosin isoforms. Biophys. J. 112, 984–996 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin S. H., Harzelrig J. B., and Cheung H. C. (1993) Transient kinetics of the interaction of actin with myosin subfragment-1 in the absence of nucleotide. Biophys. J. 65, 1433–1444 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81209-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miki M., Miura T., Sano K., Kimura H., Kondo H., Ishida H., and Maéda Y. (1998) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between points on tropomyosin and actin in skeletal muscle thin filaments: does tropomyosin move? J. Biochem. 123, 1104–1111 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimura-Sakiyama C., Ueno Y., Wakabayashi K., and Miki M. (2008) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between residues on troponin and tropomyosin in the reconstituted thin filament: modeling the troponin-tropomyosin complex. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 80–91 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tao T., Lamkin M., and Lehrer S. S. (1983) Excitation energy transfer studies of the proximity between tropomyosin and actin in reconstituted skeletal muscle thin filaments. Biochemistry 22, 3059–3066 10.1021/bi00282a006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang S., Barbu-Tudoran L., Orzechowski M., Craig R., Trinick J., White H., and Lehman W. (2014) Three-dimensional organization of troponin on cardiac muscle thin filaments in the relaxed state. Biophys. J. 106, 855–864 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gordon A. M., Homsher E., and Regnier M. (2000) Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 80, 853–924 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williams M. R., Lehman S. J., Tardiff J. C., and Schwartz S. D. (2016) Atomic resolution probe for allostery in the regulatory thin filament. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 3257–3262 10.1073/pnas.1519541113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vibert P., Craig R., and Lehman W. (1997) Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 266, 8–14 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lehman W., and Craig R. (2008) Tropomyosin and the steric mechanism of muscle regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 644, 95–109 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu C., Craig R., Tobacman L., Horowitz R., and Lehman W. (1999) Tropomyosin positions in regulated thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Biophys. J. 77, 985–992 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76949-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hwang P. M., Cai F., Pineda-Sanabria S. E., Corson D. C., and Sykes B. D. (2014) The cardiac-specific N-terminal region of troponin I positions the regulatory domain of troponin C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14412–14417 10.1073/pnas.1410775111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Geeves M. A., and Holmes K. C. (1999) Structural mechanism of muscle contraction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 687–728 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dong W. J., An J., Xing J., and Cheung H. C. (2006) Structural transition of the inhibitory region of troponin I within the regulated cardiac thin filament. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 456, 135–142 10.1016/j.abb.2006.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Poole K. J., Lorenz M., Evans G., Rosenbaum G., Pirani A., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Lehman W., and Holmes K. C. (2006) A comparison of muscle thin filament models obtained from electron microscopy reconstructions and low-angle X-ray fibre diagrams from non-overlap muscle. J. Struct. Biol. 155, 273–284 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Manning E. P., Tardiff J. C., and Schwartz S. D. (2012) Molecular effects of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related mutations in the TNT1 domain of cTnT. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 54–66 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Manning E. P., Tardiff J. C., and Schwartz S. D. (2011) A model of calcium activation of the cardiac thin filament. Biochemistry 50, 7405–7413 10.1021/bi200506k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gordon A. M., Regnier M., and Homsher E. (2001) Skeletal and cardiac muscle contractile activation: tropomyosin “rocks and rolls.” News Physiol. Sci. 16, 49–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Margossian S. S., and Lowey S. (1982) Preparation of myosin and its subfragments from rabbit skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol. 85, 55–71 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ueda K., Kimura-Sakiyama C., Aihara T., Miki M., and Arata T. (2011) Interaction sites of tropomyosin in muscle thin filament as identified by site-directed spin-labeling. Biophys. J. 100, 2432–2439 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Matsuo N., Nagata Y., Nakamura J., and Yamamoto T. (2002) Coupling of calcium transport with ATP hydrolysis in scallop sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biochem. 131, 375–381 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kast D., Espinoza-Fonseca L. M., Yi C., and Thomas D. D. (2010) Phosphorylation-induced structural changes in smooth muscle myosin regulatory light chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8207–8212 10.1073/pnas.1001941107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Orzechowski M., Li X. E., Fischer S., and Lehman W. (2014) An atomic model of the tropomyosin cable on F-actin. Biophys. J. 107, 694–699 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., and Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. MacKerell A. D. Jr., Banavali N., and Foloppe N. (2000) Development and current status of the CHARMM force field for nucleic acids. Biopolymers 56, 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.