Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of extended half-life, full-length, pegylated recombinant factor VIII rurioctocog alfa pegol [BAX 855, ADYNOVATE (USA)/ADYNOVI (Europe); Baxalta US Inc., a Takeda company, Lexington, MA, USA] was investigated in previously treated Korean patients with severe hemophilia A (HA).

Methods

A post hoc data analysis from the international, multicenter, phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE study of rurioctocog alfa pegol in patients with severe HA (NCT01736475) determined annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) and rates of adverse events (AEs) in Korean patients treated in this study.

Results

All 10 enrolled Korean patients receiving rurioctocog alfa pegol (9 prophylaxis, 1 on-demand) completed the study [median (range) age, 28.0 (12–50) yr; weight, 64.8 (45–90) kg; 8 patients had ≥1 target joint at screening]. Median (range) ABR was 1.9 (0.0–14.5) for patients on prophylaxis and 62.2 for the patient receiving on-demand treatment. The hemostatic efficacy of rurioctocog alfa pegol was rated “excellent” or “good” and only single infusions were required per bleeding episode. ABRs improved in most patients compared with prestudy values. No dose adjustments were required for prophylaxis, and the dosing frequency was reduced in 8 patients, compared with their previous prophylaxis regimen. No serious AEs were reported; all 9 nonserious AEs (in 3 patients) were mild in severity and unrelated to the study treatment.

Conclusion

This post hoc analysis of a small group of Korean patients with severe HA indicated that rurioctocog alfa pegol was effective, and no serious AEs were observed. For most patients, the dosing frequency was also reduced compared with their previous regimen.

Keywords: Hemophilia A, Factor VIII, Rurioctocog alfa pegol, BAX 855, Post hoc analysis

INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A (HA) is a rare, recessive, X-linked, congenital bleeding disorder caused by deficient or defective coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) [1]. This deficiency leads to excessive bleeding following trauma or injury and spontaneous bleeding episodes, primarily in the joints, muscles, and soft tissues [1,2]. Although HA affects all racial and ethnic groups [3], severe HA (<1% of normal FVIII activity) [4] seems to affect a larger proportion of Korean patients [5]. Data from the Korean Hemophilia Foundation Registry reported that 68% of Korean patients have severe HA [5], in contrast to a prevalence range of ~35–55% for severe HA reported in other countries [5,6,7,8,9].

Currently, the management of severe HA involves regular and long-term administration of FVIII products (commonly referred to as prophylactic FVIII replacement therapy) to reduce the number of bleeding episodes [2]. Primary prophylaxis is designed to maintain trough FVIII levels >1% to prevent frequent joint-related bleeding episodes and the development of chronic arthropathy, a condition that is known to drastically reduce the quality of life of patients with HA [10,11].

Prophylactic treatment of HA is often performed with the administration of third-generation recombinant FVIII (rFVIII) products, which, in contrast to plasma-derived concentrates, do not contain any human or animal proteins [12]. Conventional rFVIII products have a standard half-life of ~10–14 hours [13,14,15,16], and consequently, patients require frequent infusions every other day or 3 days per week to maintain their trough FVIII levels [17]. Frequent intravenous infusions of FVIII products are a known barrier to treatment adherence; thus, rFVIII molecules with extended half-lives may improve treatment adherence by reducing dosing frequency [12,18].

Rurioctocog alfa pegol [BAX 855, ADYNOVATE (USA)/ADYNOVI (Europe); Baxalta US Inc., a Takeda company, Lexington, MA, USA] is a third-generation rFVIII with a modified polyethylene glycol component that increases the half-life rFVIII by 1.4–1.5-fold versus standard half-life rFVIII [19,20]. The international, multicenter, open-label phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE study (NCT01736475) showed that prophylactic rurioctocog alfa pegol treatment was effective in previously treated patients with severe HA, reducing the annualized bleeding rate (ABR) by 90% (relative to the on-demand treatment group), with ~60% of patients achieving an interval of ≥5 months between joint bleeding episodes [20]. No FVIII inhibitory antibodies or other safety signals were observed during the study [20].

In this study, a post hoc analysis of the phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE clinical trial was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of prophylactic and on-demand treatment with rurioctocog alfa pegol in Korean patients with severe HA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The international, multicenter, open-label, phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE study (NCT01736475) was conducted between January 2013 and July 2014 to assess the efficacy and safety of rurioctocog alfa pegol in previously treated patients with severe HA. The study was approved by the independent review board at each participating site and was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation. All patients signed the written informed consent for inclusion in the study, and independent data monitoring committees monitored patient safety throughout the study [20]. Full methodology for the study has been reported previously [20].

Consenting patients enrolled in PROLONG-ATE were aged 12–65 years, with FVIII clotting activity of <1%, for which they must have received previous treatment with plasma-derived FVIII or rFVIII products for ≥150 exposure days. Eligible patients had no detectable FVIII inhibitory antibodies at screening or a history of FVIII inhibitory antibodies at any time before screening and no inherited or acquired hemostatic defects other than HA [20]. At baseline, the number of target joints (i.e., a single joint with ≥3 spontaneous bleeding episodes in any consecutive 6-month period) was recorded.

Patients were assigned to receive standard doses of treatment on the basis of their prestudy FVIII treatment regimen, receiving either on-demand rurioctocog alfa pegol (10 to 60±5 IU/kg) or prophylactic rurioctocog alfa pegol (45±5 IU/kg, twice weekly). Doses of rurioctocog alfa pegol for the treatment of bleeding episodes were adjusted on the basis of bleeding severity as follows: mild bleeding episode (10 to 20±5 IU/kg), repeat infusions every 12 to 24 hours for at least 1 day, until the bleeding episode is resolved or healing is achieved; moderate bleeding episode (15 to 30±5 IU/kg), repeat infusions every 12 to 24 hours for 3 days or more until the pain and acute disability/incapacity are resolved; and severe bleeding episode (30 to 60±5 IU/kg). In the case of life-threatening bleeding episodes a dose of 80±5 IU/kg may be considered, and infusions should be repeated every 8 to 12 hours until the bleeding episode/threat is resolved. Prophylactic rurioctocog alfa pegol treatment was administered for ≥50 exposure days or for 6 months ±2 weeks, while on-demand treatment was given for 6 months ±2 weeks [20]. Dose adjustment for prophylactic treatment (from 45±5 IU/kg to 60 IU/kg) could be administered to patients meeting ≥1 of the following criteria: ≥2 spontaneous bleeding episodes in the same target joint within any 2-month period during the study, ≥1 spontaneous bleeding episode in a nontarget joint within any 2-month period, and an FVIII trough level of <1% together with an assessment of a patient's increased risk of bleeding by the study investigator.

Patients were provided eDiaries, wherein they reported their infusion records, bleeding episodes, response to treatment, adverse events (AEs), concomitant medications, and PROs. Bleeding severity was rated by patients as “mild”, “moderate”, or “severe” based on provided guidelines. Severity was defined as “mild”, little or no pain, little or no change in the range of motion of the affected joint, and mild restriction of mobility and activity; “moderate”, mild or moderate pain, some decrease in range of movement of the affected joint, and moderate decrease in mobility and activity; and “severe”, significant pain, substantial decrease in the range of motion of the affected joint, incapacity, and life-threatening.

Outcome measures

The primary efficacy outcome measure was ABR, calculated as the number of bleeding episodes divided by the observation period in years. Secondary outcome measures (as described previously) [20] included the weight-adjusted total dose of rurioctocog alfa pegol, the number of rurioctocog alfa pegol infusions to treat bleeding episodes, and the hemostatic efficacy for the treatment of bleeding episodes measured 24 hours post infusion, assessed using the following 4-point rating scale:

Excellent: Full relief of pain and cessation of objective signs of bleeding after a single infusion and no additional infusion required for the control of bleeding (except to maintain hemostasis).

Good: Definite pain relief and/or improvement in the signs of bleeding after a single infusion and possibly required >1 infusion for complete resolution.

Fair: Probable and/or slight relief of pain and slight improvement in the signs of bleeding after a single infusion and required >1 infusion for complete resolution.

None: No improvement or condition worsened.

Safety outcome measures included the percentage of patients with serious AEs (SAEs) and nonserious AEs occurring from first exposure to rurioctocog alfa pegol until the end of the study and were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 17.0).

Statistical analysis

Safety and efficacy data from this post hoc analysis were reported by treatment regimen using descriptive statistics. The primary endpoint of ABR was evaluated using a general linear model framework, accounting for the fixed effect of study arm, age at baseline as a continuous covariate, and the follow-up time (in years) as an offset. Ratios between study arm means (95% confidence interval) will be estimatedwithin this model.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

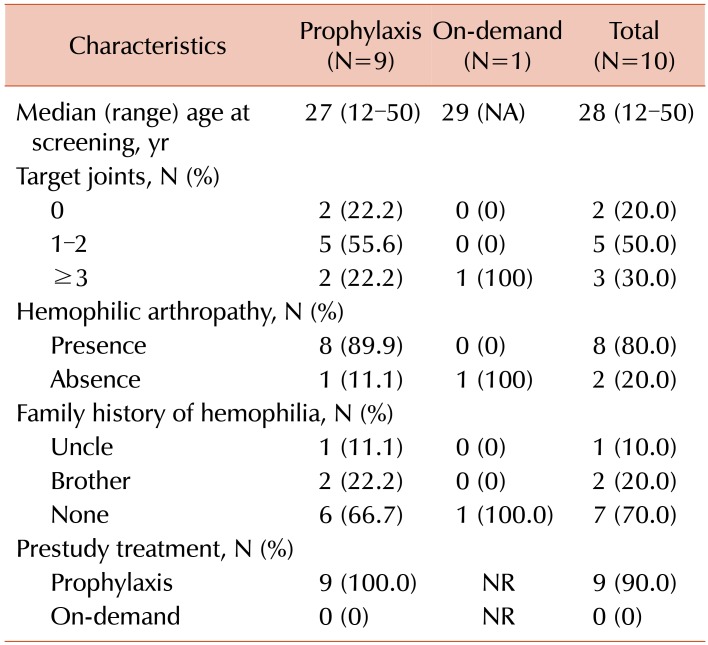

The Korean subgroup of the PROLONG-ATE study comprised 10 patients, where 9 received rurioctocog alfa pegol as prophylaxis and 1 as on-demand treatment, consistent with their previous treatment regimen. The median (range) patient age was 28 (12–50) years (Table 1). Hemophilic arthropathy was present in 8 of 10 patients. Five of the 10 Korean patients had 1–2 target joints, and the remaining 3 patients had ≥3 target joints (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) observation period was 6.38 (0.34) months for patients receiving prophylaxis (N=9) and 5.98 months for the single patient receiving on-demand treatment.

Table 1. Demographics of Korean patients with severe hemophilia A.

Hemophilia gene mutation was unknown for all 10 Korean study patients.

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

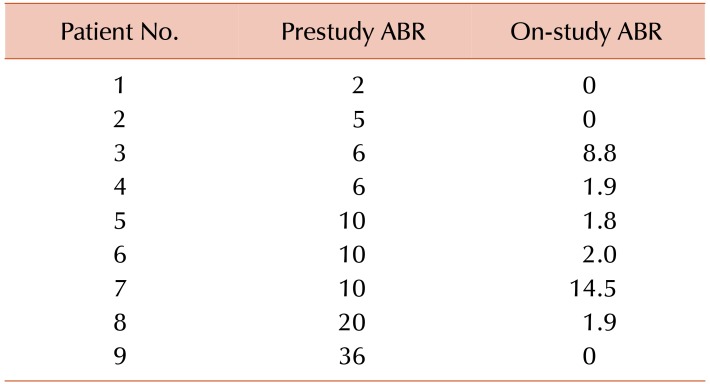

There was a wide range of prestudy ABRs reported among the 9 Korean patients receiving prophylaxis before study entry, ranging from 2 to 36 (Table 2). The prestudy ABR for the single patient receiving on-demand treatment during the study was 36.

Table 2. Comparison of on-study annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) with prestudy ABRs in 9 patients with severe hemophilia A receiving prophylaxis with rurioctocog alfa pegol.

Abbreviation: ABR, annualized bleeding rate.

Regarding the administration of rurioctocog alfa pegol during the study, the median (range) dose used per prophylactic infusion was 39.3 (37.0–46.2) IU/kg. A median (range) of 2.0 (2.0–2.0) prophylactic infusions were administered per week, with a median (range) interval of 3.5 (3.5–3.6) days between infusions.

Efficacy

The median (range) ABR was 1.9 (0.0–14.5) (mean±SD, 3.4±5.0) for the 9 Korean patients who received prophylaxis with rurioctocog alfa pegol (Table 2). The on-study ABR for the single Korean patient receiving on-demand rurioctocog alfa pegol was 62.2.

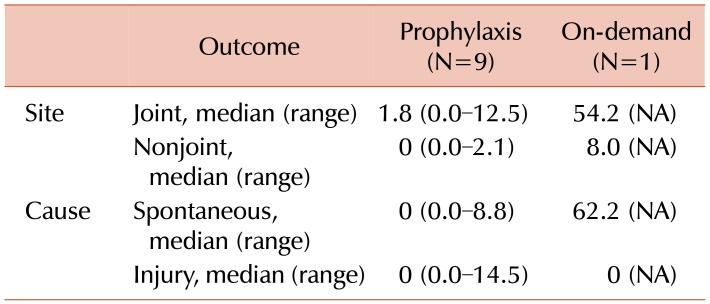

Most Korean patients receiving prophylaxis had lower ABRs during the study compared to prestudy ABRs (Table 2). Among the 9 Korean patients on prophylaxis, the observed frequency of bleeding was higher in joints than in nonjoints, and traumatic bleeding episodes were more frequent than spontaneous bleeding episodes (Table 3). Moreover, patient 7 (Table 2), with an on-study ABR of 14.5 (prestudy ABR, 10), had 2 target joints (right ankle and right elbow) episodes at screening and, subsequently, 8 injury-related bleeding episodes to the right ankle and skin (and no spontaneous bleeding episodes). Patient 3 (Table 2), with an on-study ABR of 8.8 (prestudy ABR, 6), had 3 target joints at screening (left ankle, right ankle, right knee) and, subsequently, 9 spontaneous bleeding episodes to the left ankle (N=3), right ankle (N=1), hip (N=4), and elbow (N=1) with no traumatic bleeding episodes.

Table 3. On-study annualized bleeding rate by bleeding site and cause.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The single patient receiving on-demand treatment also experienced the highest frequency of joint bleeding (ABR, 54.2) and spontaneous bleeding (ABR, 62.2). This patient had 4 target joints at baseline, and joint bleeding was more frequent than nonjoint bleeding (ABR, 8.0) during the study; no traumatic bleeding episodes were reported for this patient (Table 3).

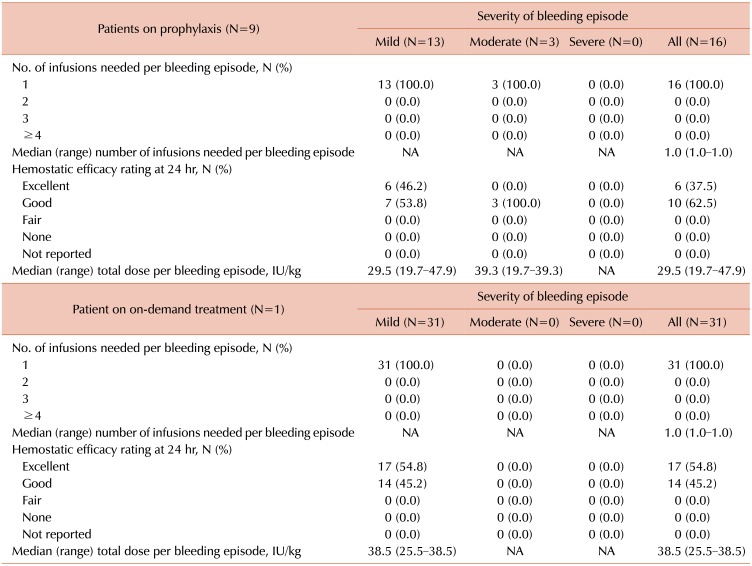

Patients experienced 47 bleeding episodes during the study (44 mild and 3 moderate in severity; Table 4). Of these, 31 bleeding episodes were experienced by the patient receiving on-demand treatment (all 31 bleeding episodes were mild in spontaneous bleeding episodes (Table 3). Moreover, patient 7 (Table 2), with an on-study ABR of 14.5 (prestudy ABR, 10), had 2 target joints (right ankle and right elbow) episodes at screening and, subsequently, 8 injury-related bleeding episodes to the right ankle and skin (and no spontaneous bleeding episodes). Patient 3 (Table 2), with an on-study ABR of 8.8 (prestudy ABR, 6), had 3 target joints at screening (left ankle, right ankle, right knee) and, subsequently, 9 spontaneous bleeding episodes to the left ankle (N=3), right ankle (N=1), hip (N=4), and elbow (N=1) with no traumatic bleeding episodes.

Table 4. Characteristics of bleeding episodes in patients receiving prophylaxis and on-demand treatment with rurioctocog alfa pegol.

Severity of bleeding episodes was defined as “mild,” little or no pain, little or no change in the range of motion of the affected joint, and mild restriction of mobility and activity; “moderate,” mild or moderate pain, some decrease in range of movement of the affected joint, and moderate decrease in mobility and activity; and “severe,” significant pain, substantial decrease in the range of motion of the affected joint, incapacity, and life-threatening.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The single patient receiving on-demand treatment also experienced the highest frequency of joint bleeding (ABR, 54.2) and spontaneous bleeding (ABR, 62.2). This patient had 4 target joints at baseline, and joint bleeding was more frequent than nonjoint bleeding (ABR, 8.0) during the study; no traumatic bleeding episodes were reported for this patient (Table 3).

Patients experienced 47 bleeding episodes during the study (44 mild and 3 moderate in severity; Table 4). Of these, 31 bleeding episodes were experienced by the patient receiving on-demand treatment (all 31 bleeding episodes were mild in severity), and 16 bleeding episodes were experienced by patients on prophylaxis (most of these, 13/16, were mild, and 3/16 were moderate in severity). No severe bleeding episodes were reported (Table 4). All patients receiving either prophylaxis or on-demand rurioctocog alfa pegol regimens required a single infusion to treat a bleeding episode. Hemostatic efficacy was rated as either “excellent” or “good” for all bleeding episodes experienced by patients receiving either prophylaxis or on-demand rurioctocog alfa pegol regimens (Table 4). The median (range) total dose of rurioctocog alfa pegol per bleeding episode was 29.5 (19.7–47.9) IU/kg for patients in the prophylaxis group and 38.5 (25.5–38.5) IU/kg for the patient receiving on-demand treatment (Table 4).

Dosing frequency

Among the 9 patients on a prophylactic regimen before the study, 8 experienced a reduction in the frequency of dosing during the study. During the study, the frequency of prophylactic dosing was reduced during the study by ≥30% in 3 patients and by <10% in 5 patients compared with prestudy dosing. No dose adjustments were required for prophylactic treatment during the study.

Safety

None of the patients in this post hoc analysis experienced SAEs during the study, and none tested positive for inhibitory antibodies to FVIII. Overall, 9 nonserious AEs were reported in 3 patients. These were abdominal pain, diarrhea, toothache, nasopharyngitis (2 events), rhinitis, cough, nasal edema, and oropharyngeal pain. All nonserious AEs were mild in severity and were considered to be unrelated to the study treatment.

DISCUSSION

This post hoc analysis of data from the phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE study evaluating the safety and efficacy of rurioctocog alfa pegol in patients with severe HA indicated that prophylactic and on-demand treatment with rurioctocog alfa pegol were effective, with no treatment-related safety signals observed in the subgroup of 10 Korean patients analyzed. Most patients achieved an improvement in ABRs during the study compared with pretreatment ABRs. For all bleeding episodes experienced by patients receiving prophylactic or on-demand regimens, the hemostatic efficacy of rurioctocog alfa pegol was rated as “excellent” or “good,” and only single infusions were required per bleeding episode. No SAEs were reported by this patient subgroup during the study, and all 9 nonserious AEs observed were considered to be unrelated to the study treatment. There were also no FVIII inhibitory antibodies detected.

The efficacy and safety results for this patient subgroup were broadly consistent with those reported for the overall study population, where the median (range) on-study ABRs were reported as 1.9 (0.0–59.6) in the 120 patients receiving rurioctocog alfa pegol prophylaxis and 41.5 (12.9–67.9) in the 17 patients receiving on-demand rurioctocog alfa pegol treatment. Additionally, 96.1% of bleeding episodes treated with rurioctocog alfa pegol had hemostatic efficacy ratings of “excellent” or “good” [20]. Furthermore, no patient in the PROLONG-ATE study reported an SAE or AE that was considered to be related to the study treatment [20].

The reduced frequency of prophylactic dosing relative to prestudy prophylactic regimens noted in most of the Korean patients analyzed was similarly experienced by the majority of patients in the PROLONG-ATE study, where 70.4% reported receiving ≥1 fewer prophylactic infusions per week when receiving rurioctocog alfa pegol during the study (median of 1.96 prophylactic rurioctocog alfa pegol infusions per wk). The majority of bleeding episodes in the PROLONG-ATE study (95.9%) were treated with 1 or 2 rurioctocog alfa pegol infusions [20].

Notwithstanding the limitations of this post hoc data analysis in a relatively small number of Korean patients from an open-label clinical trial, these data are still of value in evaluating the efficacy and safety profile of rurioctocog alfa pegol for prophylaxis and on-demand treatment of bleeding episodes in this cohort of Korean patients aged 12–50 years with severe HA, in which 8 out of 10 patients had target joints at baseline.

Consistent with the findings reported for the overall PROLONG-ATE study population, most Korean patients experienced a reduction in the frequency of prophylactic dosing and did not require dosing adjustments. Both of these observations support twice-weekly administration of rurioctocog alfa pegol to effectively prevent and treat bleeding episodes in these patients. This could offer potential advantages in terms of patient management and treatment adherence relative to standard half-life rFVIII products, which require a more frequent prophylactic dosing schedule in these patients [17].

In conclusion, the results of this post hoc analysis of data from Korean patients participating in the international, multicenter, open-label, phase 2/3 PROLONG-ATE study are in agreement with the previously reported efficacy and safety profile of rurioctocog alfa for prophylactic and on-demand treatment of bleeding episodes in patients with severe HA and provide useful insights into its use in the wider population of Korean patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Isobel Lever, Ph.D., employee of Excel Medical Affairs (Southport, CT, USA) and was funded by Baxalta US Inc., Lexington, MA, USA, a member of the Takeda group of companies.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Baxalta US Inc., Lexington, MA, USA, and Baxalta Innovations GmbH, Vienna, Austria, members of the Takeda group of companies.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: CWY, HJB, SKP, YSP, and H-JS have no conflicts of interest to declare. WE is an employee of Baxalta Innovations GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. ST is an employee of Baxalta US Inc., a member of the Takeda group of companies, and a Takeda stock owner.

References

- 1.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias-from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1773–1779. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19:e1–e47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. What is hemophilia? Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [March 13, 2019]. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hemophilia/facts.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Federation of Hemophilia. Severity of hemophilia. Quebec, Canada: World Federation of Hemophilia; 2012. [March 13, 2019]. https://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=643. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Kim SK, Park SK, Yoo KY, Hwang TJ, Choi YM. Korea Hemophilia Foundation registry trends 1991–2012: patient registry, demographics, health services utilization. Haemophilia. 2015;21:e479–e480. doi: 10.1111/hae.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plug I, Van Der Bom JG, Peters M, et al. Mortality and causes of death in patients with hemophilia, 1992–2001: a prospective cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallden C, Nilsson D, Sall T, Lind-Hallden C, Liden AC, Ljung R. Origin of Swedish hemophilia A mutations. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2503–2511. doi: 10.1111/jth.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darby SC, Kan SW, Spooner RJ, et al. Mortality rates, life expectancy, and causes of death in people with hemophilia A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood. 2007;110:815–825. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Federation of Hemophilia. Report on the Annual Global Survey 2016. Quebec, Canada: World Federation of Hemophilia; 2017. [March 13, 2019]. http://www1.wfh.org/publications/files/pdf-1690.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:535–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi EJ. Management of hemophilia in Korea: the past, present, and future. Blood Res. 2014;49:144–145. doi: 10.5045/br.2014.49.3.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieuw K. Many factor VIII products available in the treatment of hemophilia A: an embarrassment of riches? J Blood Med. 2017;8:67–73. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S103796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björkman S, Folkesson A, Jonsson S. Pharmacokinetics and dose requirements of factor VIII over the age range 3–74 years: a population analysis based on 50 patients with long-term prophylactic treatment for haemophilia A. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:989–998. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Björkman S, Berntorp E. Pharmacokinetics of coagulation factors: clinical relevance for patients with haemophilia. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:815–832. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White GC, 2nd, Courter S, Bray GL, Lee M, Gomperts ED. A multicenter study of recombinant factor VIII (Recombinate) in previously treated patients with hemophilia A. The Recombinate Previously Treated Patient Study Group. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:660–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Björkman S. Prophylactic dosing of factor VIII and factor IX from a clinical pharmacokinetic perspective. Haemophilia. 2003;9:101–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.9.s1.4.x. discussion 109-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogami K, Shima M, Fukutake K, et al. Efficacy and safety of full-length pegylated recombinant factor VIII with extended half-life in previously treated patients with hemophilia A: comparison of data between the general and Japanese study populations. Int J Hematol. 2017;106:704–710. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornburg CD, Duncan NA. Treatment adherence in hemophilia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1677–1686. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S139851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: Adynovate, antihemophilic factor (recombinant), PEGylated lyophilized powder for solution for intravenous injection. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2016. [March 13, 2019,]. https://www.fda.gov/media/94470/download. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konkle BA, Stasyshyn O, Chowdary P, et al. Pegylated, full-length, recombinant factor VIII for prophylactic and on-demand treatment of severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2015;126:1078–1085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-630897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]