Abstract

Background and Purpose

Mibefradil, a T‐type Ca2+ channel blocker, has been investigated for treating solid tumours. However, its underlying mechanisms are still unclear. Here, we have investigated the pharmacological actions of mibefradil on Orai store‐operated Ca2+ channels.

Experimental Approach

Human Orai1‐3 cDNAs in tetracycline‐regulated pcDNA4/TO vectors were transfected into HEK293 T‐REx cells with stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) stable expression. The Orai currents were recorded by whole‐cell and excised‐membrane patch clamp. Ca2+ influx or release was measured by Fura‐PE3/AM. Cell growth and death were monitored by WST‐1, LDH assays and flow cytometry.

Key Results

Mibefradil inhibited Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 currents dose‐dependently. The IC50 for Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 channels was 52.6, 14.1, and 3.8 μM respectively. Outside‐out patch demonstrated that perfusion of 10‐μM mibefradil to the extracellular surface completely blocked Orai3 currents and single channel activity evoked by 2‐APB. Intracellular application of mibefradil did not alter Orai3 channel activity. Mibefradil at higher concentrations (>50 μM) inhibited Ca2+ release but had no effect on cytosolic STIM1 translocation evoked by thapsigargin. Inhibition on Orai channels by mibefradil was structure‐related, as other T‐type Ca2+ channel blockers with different structures, such as ethosuximide and ML218, had no or minimal effects on Orai channels. Moreover, mibefradil inhibited cell proliferation, induced apoptosis, and arrested cell cycle progression.

Conclusions and Implications

Mibefradil is a potent cell surface blocker of Orai channels, demonstrating a new pharmacological action of this compound in regulating cell growth and death, which could be relevant to its anti‐cancer activity.

Abbreviations

- 2‐APB

2‐aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- CRAC

Ca2+‐release activated Ca2+

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- HAECs

human aortic endothelial cells

- SOCE

store‐operated Ca2+ entry

- STIM1

stromal interaction molecule 1

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

- TIRF

total internal reflection fluorescence

- VGCC

voltage‐gated calcium channel

What is already known

Mibefradil is a T‐type channel blocker and has been repurposed as an anti‐cancer drug.

Orai proteins are store‐operated Ca2+ channels and can regulate cell growth and death.

What this study adds

Mibefradil is a potent inhibitor of Orai channels.

Mibefradil acts on the extracellular surface of cells and regulates their proliferation and apoptosis.

What is the clinical significance

Our findings provide new pharmacological activities for this classic T‐type channel blocker.

Inhibition of Orai channels and store‐operated Ca2+ entry could explain the anti‐cancer actions of mibefradil.

1. INTRODUCTION

Orai channels have been regarded as the molecular fingerprints of Ca2+‐release activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels, the highly Ca2+ selective store‐operated channels (Feske et al., 2006; Prakriya et al., 2006). The channels can be activated by the depletion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores via the activation of GPCR and/or protein tyrosine kinase ‐coupled receptors. Orai channels are widely expressed in many cell types and highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (Trebak, 2012) and proximal tubular cells (Zeng et al., 2017). There are three isoforms of Orai channels, referred to as Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3. Loss‐of‐function mutation of Orai1 channels caused immune deficiency (Feske et al., 2006) and dysfunction of thrombus formation (Bergmeier et al., 2009; Braun et al., 2009). Inhibition of Orai1 channels enhances diabetic proteinuria (Zeng et al., 2017). Therefore, these channels may act as potential therapeutic targets for immune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetic complications.

Mibefradil, also known as Ro 40‐5967 (Bezprozvanny & Tsien, 1995), is a tetralol derivative chemically distinct from other calcium channel antagonists. It is a potent T‐type voltage‐gated calcium channel (VGCC) blocker with a high selectivity over L‐type VGCC (10‐ to 15‐fold preference for T‐type over L‐type; Martin, Lee, Cribbs, Perez‐Reyes, & Hanck, 2000; Mishra & Hermsmeyer, 1994). It blocks all three subtypes of T‐type channel, that is, Cav3.1, Cav3.2, and Cav3.3 channels, with an IC50 of 5.8–7.2 μM (Alexander et al., 2017). Mibefradil was initially developed as a cardiovascular drug and used in clinic with the trade name Posicor® to treat hypertension and angina (Lee et al., 2002), but withdrawn from the market by Hoffmann‐La Roche in 1998 because of drug interactions with liver enzymes (SoRelle, 1998). Recently, mibefradil has been repurposed as a targeted treatment for solid tumours and its unwanted drug–drug interactions have been minimized by short‐term dose exposure (Holdhoff et al., 2017). Mibefradil is currently in a phase Ib clinical trial with the National Cancer Institute Adult Brain Tumour Consortium (Holdhoff et al., 2017). The mechanism of anti‐cancer therapy was thought to be via the blockade of Ca2+ influx through T‐type channels, but it is still unclear how the T‐type channels in non‐excitable cancer cells can be activated and thus exert anti‐tumour effects.

As Orai channels are regulated by many hormones and growth factors via GPCRs, and VGCC may have a functional interaction with Orai /stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1; Wang et al., 2010), and additionally Ca2+ influx via store‐operated channels is critical for cell proliferation and apoptosis (Abdullaev et al., 2008), we have therefore hypothesized that the T‐type channel blocker mibefradil may have effects beyond acting on T‐type channels. Here, we have examined the effect of mibefradil on Orai channels using inducible HEK293 T‐REx cells, overexpressing these channel proteins and STIM1, and found that mibefradil was a potent inhibitor of Orai channels.

2. METHODS

2.1. Cell culture and transfection

Human Orai channels (GenBank accession number: Orai1, NM_032790; Orai2, NM_032831; Orai3, NM_152288) in pcDNA4/TO tetracycline (Tet)‐regulatory vector tagged with fluorescent report genes (mCherry– Orai1, mCherry– Orai2, and monomeric cyan fluorescent protein– Orai3) were transfected into HEK‐293 T‐REx cells (RRID:CVCL_D585, Invitrogen, UK). The human STIM1 (accession number: NM_001277961) tagged with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein at the C‐terminus (STIM1–EYFP) was stably co‐expressed in the cells with Orai channels. The detailed procedures for transfection have been described previously (Zeng, Chen, & Xu, 2012). The cells with stable expression of STIM1–EYFP and inducible Orai channels were used in the study. The functional expression of ORAIs and STIM1 in the transfected cells have been characterized in our previous reports (Daskoulidou et al., 2015; Zeng et al., 2017; Zeng, Chen, Daskoulidou, & Xu, 2014). The cells were seeded onto coverslips in culture dishes, and expression of Orai channels was induced by 1 μg·ml−1 tetracycline for 24–72 hr before electrophysiological recording or Ca2+ imaging. The non‐induced cells (without addition of Tet) or non‐transfected HEK‐293 T‐REx cells were used as controls. HEK‐293 T‐REx cells were grown in DMEM‐F12 medium (Invitrogen, UK) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 units·ml−1 penicillin, and 100 μg·ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C under 95% air and 5% CO2 and seeded on coverslips prior to experiments. Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were purchased from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany), and endothelial cells EA.hy926, a permanent cell line derived from HUVECs, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; ATCC Cat# CRL‐2922, RRID:CVCL_3901; Middlesex, UK). Endothelial cells were cultured in endothelial cell medium (PromoCell, Germany) supplemented with 2% FCS, 0.1 ng·ml−1 recombinant human epidermal growth factor, and 1 ng·ml−1 basic FGF. HAECs at Passages 2–3 were used for the experiment. The human proximal tubular cell line (HK‐2) was purchased from LGC standards (ATCC Cat# CRL‐2190, RRID:CVCL_0302, UK). HK‐2 cells were maintained in DMEM/F‐12 medium with 5‐mM glucose and supplemented with 10% FCS, 10‐mM HEPES, and antibiotics. All the cultured cells were maintained at 37°C under 95% air and 5% CO2.

2.2. Electrophysiology

The procedure for whole‐cell clamp is similar to that described in our previous reports (Xu et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2017). Briefly, the electrical signal was amplified with an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier and controlled with pClamp software 10. A 1‐s ramp voltage protocol from −100 to +100 mV was applied at a frequency of 0.2 Hz from a holding potential of 0 mV. Signals were sampled at 3 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. The glass microelectrode with a resistance of 3–5 MΩ was used. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 145 Cs‐methanesulfonate, 10 BAPTA, 8 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH). Same pipette solution was used for outside‐out patches. The standard bath solution contained (mM) 130 NaCl, 5 KCl, 8 D‐glucose, 10 HEPES, 1.2 MgCl2, and 1.5 CaCl2. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Some experiments were performed using a divalent cation free solution, containing (mM): 150 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10 D‐glucose, 10 EDTA, and 10 tetraethylammonium chloride. For single channel recordings, the current was sampled at 10 kHz. The experiments were performed at room temperature (25°C).

2.3. Ca2+ measurement and live cell imaging

Cells were preincubated with 2‐μM Fura‐PE3/AM at 37°C for 30 min in Ca2+‐free bath solution (composition, mM: 130 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 8 D‐glucose, and 0.4 EGTA), followed by a 20‐min wash period in the standard bath solution at room temperature. The ratio of Ca2+ dye fluorescence (F340/F380) was measured using FlexStation 3 (Molecular Device, USA). Control groups were set in parallel in the 96‐well plate. For STIM1 translocation experiments, the procedure was as described by Zeng et al., (2012). The stably transfected STIM1–EYFP cells were seeded on 13‐mm glass coverslips and cultured for 24–48 hr. Live cell images for EYFP fluorescence were captured using a microscope equipped with a Nikon Plan Fluor ×100/1.30 oil objective. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy was performed in some experiments using a Nikon CFI Apochromat TIRF objective (× 100, 1.49 NA) and sCMOS camera (ORCA‐Flash4.0 V2, Hamamatsu, Japan) as we describe previously (Zeng et al., 2017). Colocalization analysis was performed with NIS‐Elements AR v4.30 (Nikon). The images were analysed with the NIS‐Elements software (Version 3.2, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). All the experiments were performed at room temperature.

2.4. Cell proliferation and cell death assays

Cell proliferation was determined using a water‐soluble tetrazolium‐1 (WST‐1) assay in which tetrazolium salts are cleaved by mitochondrial dehydrogenase to form formazan in viable cells. For necrotic cell death, the activity of cytosolic LDH released into the culture medium was determined using a Cytotoxicity Detection Kit. The procedures for WST‐1 and LDH assays have been described (Xu et al., 2008). The absorbance for WST‐1 assays and LDH assays were measured using a spectrophotometer.

2.5. Fluorescence‐activated cell sorting

The HK‐2 cells were seeded in a 6‐cm petri dish at a confluence of 5,000 cells per ml and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C for 24 hr. The cells were pretreated with different concentrations of mibefradil for 24‐hr, then trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA, and centrifuged twice for washing with PBS in FACS tubes at 300 g for 5 min. The propidium iodide (10 μg·ml−1) was added to all the tubes and incubated for 15 min before mounting for FACS detection. The cell cycle was analysed using CellQuest software.

2.6. Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. In this study, “n” refers to independent experiments where recombinant channel expression was induced by the addition of tetracycline for 24–72 hr to cells maintained on separate coverslips. We consider electrophysiological recordings derived from these separate dishes to constitute independent experiments, as is typical in ion channel experiments. The experiments are not blinded and randomized, but controlled studies. Experimenter treated the cells with tetracycline to induce gene expression as a positive transfected group and cells without treatment as a negative control. Self‐controlled design was used to test drug effect through comparison of before and after drug applications. The unblinded experimental data were analysed in an identical manner for all conditions to eliminate possible operator bias. Mean data were compared using paired t test for the results before and after treatment in experiments without blinding or ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc analysis for comparing more than two groups. For all ANOVAs, post hoc tests were only applied when F achieved P < .05 and there was no significant variance inhomogeneity. P < .05 was taken to indicate significant differences between group means.

2.7. Materials

All general salts and reagents were from Sigma (UK). Mibefradil dihydrochloride hydrate, 2‐aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2‐APB), tetracycline, thapsigargin, ethosuximide, and WST‐1 and LDH assay kits were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. ML218 was purchased from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel). Fura‐PE3/AM was purchased from Invitrogen (UK). Fura‐PE3/AM (1 mM) and 2‐APB (100 mM) were made up as stock solutions in 100% DMSO. Mibefradil was prepared as 10‐mM stock solution in H2O.

2.8. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander et al., 2017). VGCC

3. RESULTS

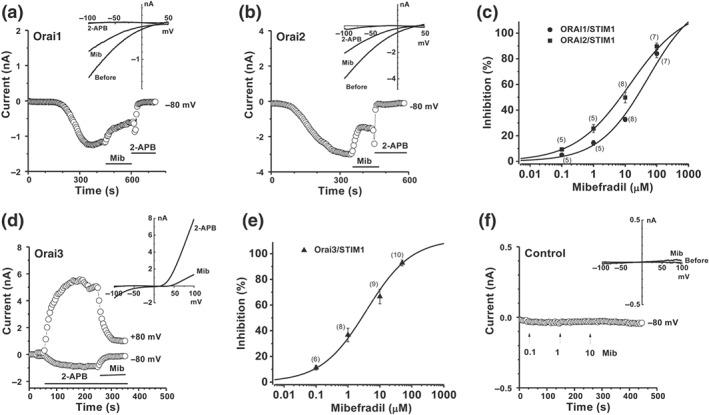

3.1. Orai channels were inhibited by mibefradil

The expression of human Orai 1‐3 channels tagged with mCherry and STIM1–EYFP in HEK‐293 T‐REx cells was induced by tetracycline and confirmed by their plasma membrane localization as described previously (Daskoulidou et al., 2015; Zeng et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2017). The whole‐cell current was recorded by patch clamp after 24‐ to 72‐hr induction of gene expression. The currents of Orai1 and Orai2 channels were activated by thapsigargin (1 μM) with an inwardly rectifying current–voltage curve (Figure 1), which is similar to our previous reports (Zeng et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2017). The thapsigargin‐evoked currents achieved maximum within about 5 min after the formation of whole‐cell patch configuration (Figure 1a,b). Mibefradil inhibited Orai1 and Orai2 currents in a concentration‐dependent manner with an IC50 of 52.6 and 14.1 μM respectively (Figure 1c). For Orai3 channels, 2‐APB (100 μM) was used as a channel activator and the IC50 of mibefradil was 3.8 μM (Figure 1d,e), suggesting that mibefradil was a more potent blocker of Orai3 channels. In the non‐induced HEK‐293 T‐REx cells, mibefradil had no significant effect on the endogenous currents (Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

Mibefradil inhibits Orai channels. (a) Orai1 current in the stable cells overexpressing mCherry– Orai1/STIM1–EYFP in the presence of thapsigargin (TG; 1 μM) in the pipette solution and the effect of mibefradil (Mib, 10 μM). (b) Orai2 current in the cells overexpressing mCherry– Orai2/STIM1–EYFP in the presence of thapsigargin (TG; 1 μM) and the effect of mibefradil (10 μM). (c) Concentration‐response curves for mibefradil on the Orai1 and Orai2 channels with an EC50 of 52.6 and 14.1 μM respectively. (d) Orai3 current in the stable cells overexpressing CFP‐ Orai3 /STIM1–EYFP was induced by 2‐APB (100 μM). Mibefradil (10 μM) inhibited the Orai3 current. (e) Concentration‐response curve for mibefradil on Orai3 channels with an EC50 of 3.8 μM. (f) Cells without induction of gene expression by tetracycline (Control). The IV curves were shown as insets after leak subtraction. The n numbers are shown in parentheses

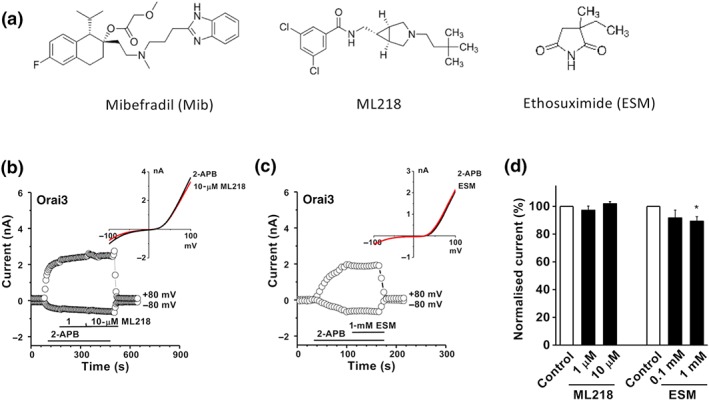

In order to explore the possibility of class effect due to T‐type channel inhibition, the non‐selective T‐type channel blockers, ML218 and ethosuximide, with differing chemical structures were used (Figure 2a). ML218 at 1 and 10 μM, concentrations known to nearly abolish the T‐type channel current (Xiang et al., 2011), had no significant effects on Orai3 channels (Figure 2b). Ethosuximide has an EC50 of 0.6 mM for T‐type channels (Gomora, Daud, Weiergraber, & Perez‐Reyes, 2001), but a higher concentration of ethosuximide (1 mM) only showed a small inhibition (Figure 2c,d), suggesting that Orai3 channels were not sensitive to either compound. Therefore, the inhibition of Orai1 channels appeared to be specific to mibefradil, rather than an indirect, class effect of T‐type channel inhibition.

Figure 2.

Effect of T‐type Ca2+ channel blockers, ML218 and ethosuximide. (a) Structure of mibefradil, ML218, and ethosuximide (ESM). (b) Effect of ML218 on Orai3 channel current. (c) Effects of ethosuximide (1 mM) on Orai3 channels. (d) Normalized data showing the effects of ML218 and ethosuximide on Orai3 channels (n = 5 for each ML218‐treated group; and n = 5 for 1‐mM ethosuximide‐treated group). *P < .05, significantly different from control

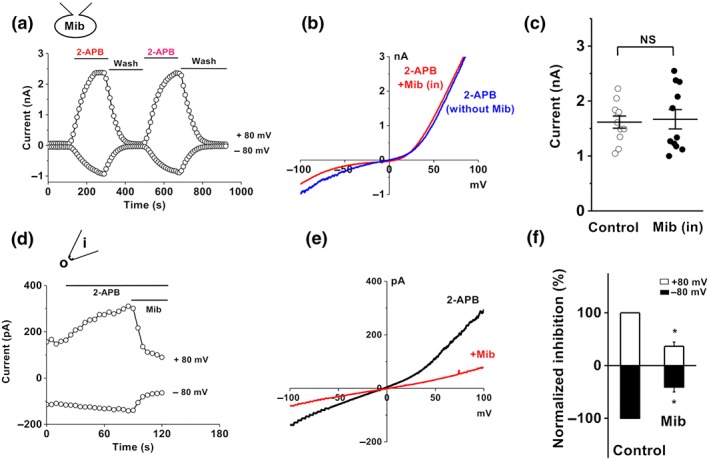

3.2. Extracellular effects of mibefradil on Orai3 channels

The cellular action site for mibefradil was determined for Orai3 channels. The higher concentration of mibefradil (100 μM) was used in the pipette solution to see whether the activation of Orai3 current could be prevented. After whole‐cell configuration was formed for 5 min, 2‐APB (100 μM) was added to the bath solution. Subsequent intracellular application of mibefradil failed to prevent the Orai3 channel current evoked by 2‐APB, which could be repeatedly activated by 2‐APB after washout (Figure 3a–c), suggesting that the site of action for mibefradil on Orai3 channels was located on the external surface of the transmembrane domains.

Figure 3.

Extracellular effect of mibefradil on Orai3 channels. (a) Whole‐cell patch was recorded in cells with Orai3 channels, using pipette solution containing 100‐μM mibefradil (Mib). 2‐APB (100 μM) was added in the bath solution. (b) Example IV curves for 2‐APB‐activated Orai3 current with mibefradil (Mib in) or without mibefradil (without Mib) in the pipette solution. (c) Mean data for 2‐APB activated current recorded with pipette solutions with or without mibefradil (Control; n = 11 for each group). (d) Example of outside‐out patches showing the effect of mibefradil (10 μM). (e) IV curve for outside‐out patch in (d). (f) Normalized mean data for the outside‐out patch current inhibited by mibefradil (10 μM; n = 5), *P < .05, significantly different from control

To further confirm their extracellular effects, outside‐out patch experiments were performed on the cells overexpressing Orai3 /STIM1. Mibefradil (10 μM) significantly inhibited the Orai3 current in these outside‐out patches (Figure 3d–f).

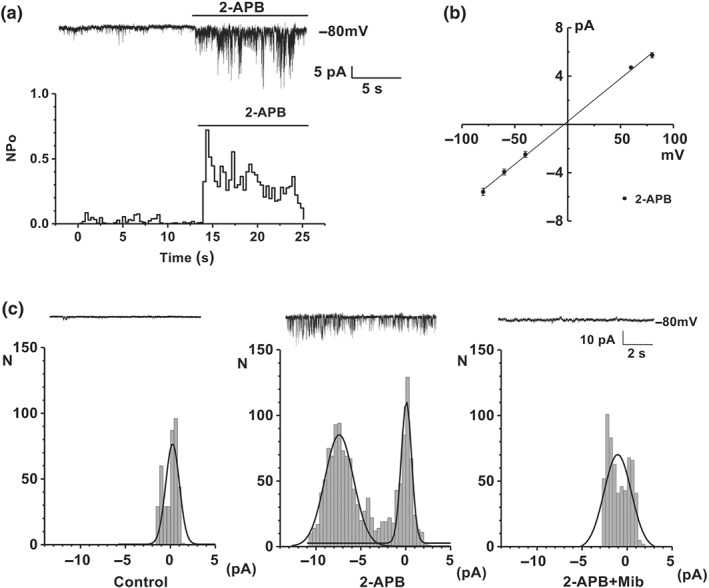

3.3. Single channel activity of Orai3 channels was inhibited by mibefradil

Outside‐out membrane patches were also used to explore the effect of mibefradil on Orai3 channel activity. Unitary events were detected after perfusion with 2‐APB (100 μM) in the tetracycline‐induced Orai3‐STIM1 cells. A typical time series plot for single channel open probability was markedly increased by 2‐APB (Figure 4a). The slope conductance for ORAI3 channel evoked by 2‐APB was calculated based on the average single channel current amplitude at each voltage step, and the value was 71.0 ± 1.4 pS (n = 11; Figure 4b). The amplitude histograms show that the unitary current events of Orai3 channels evoked by 2‐APB were nearly abolished by mibefradil (Figure 4c), suggesting the direct inhibition of mibefradil on Orai3 channels.

Figure 4.

Single channel activity of Orai3 channels and the effect of mibefradil. (a) Original outside‐out patch recording showing single channel activity of Orai3 channels was induced by 2‐APB (100 μM) in tetracycline‐induced Orai3/STIM1 cells. Time‐series plot for single channel open probability (NPo), showing the activation by bath‐applied 2‐APB. (b) Mean unitary current sizes for 2‐APB‐evoked single channel events plotted against voltage. The mean slope conductance, fitted by straight lines, was 71.0 ± 1.4 pS (n = 11 cells). (c) Typical outside‐out patch traces and amplitude histograms for control (no 2‐APB), 2‐APB (100 μM), and 2‐APB (100 μM) plus mibefradil (10 μM) groups

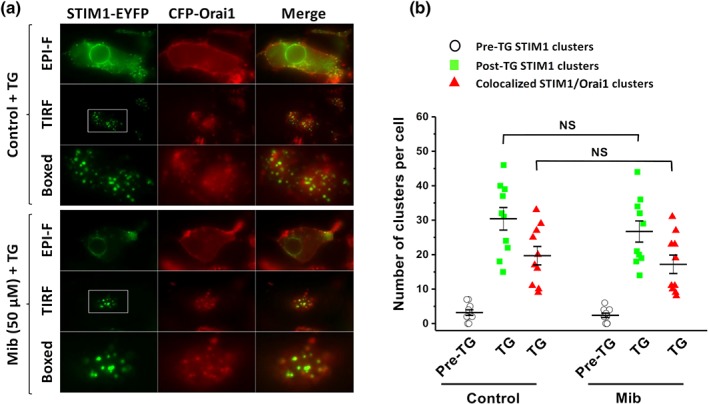

3.4. No effect of mibefradil on STIM1 translocation

The clustering and movement of cytosolic STIM1 onto the subplasma membrane is a critical process for Orai and STIM1 interaction and Orai channel opening, and this translocation offers a new target for Orai hannel modulation (Zeng et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2014). Therefore, we examined the effect of mibefradil on STIM1 movement. The subplasmalemmal translocation and clustering of STIM1 was induced by depletion of ER Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin in the HEK293 cells stably expressing STIM1 tagged with EYFP and determined by TIRF microscopy, rather than epi‐fluorescence images. Pretreatment with mibefradil did not affect STIM1–EYFP clustering, cytosolic translocation, and colocalization with Orai channels near the subplasmalemmal membrane (Figure 5, also see Figure S1), suggesting that mibefradil did not affect the STIM1 clustering and translocation in these cells.

Figure 5.

STIM1 subplasmalemmal translocation and STIM1/Orai1 clustering after Ca2+ store depletion in the stable transfected STIM1–EYFP/CFP‐Orai1 cells and the effect of mibefradil (Mib). (a) Thapsigargin (TG; 1 μM) induced STIM1/Orai1 puncta formation at the plasma membrane. Both TIRF and EPI‐F images were sampled and the subplasmalemmal STIM1 clusters (puncta) and colocalization with Orai1 were analysed. The boxed areas were enlarged in the corresponding panels. (b) Cells pretreated with mibefradil (50 μM) or without mibefradil (Control) and then added with thapsigargin (1 μM). The data are pooled from five independent experiments and 10 images for each group were analysed (n = 10; NS, non‐significant)

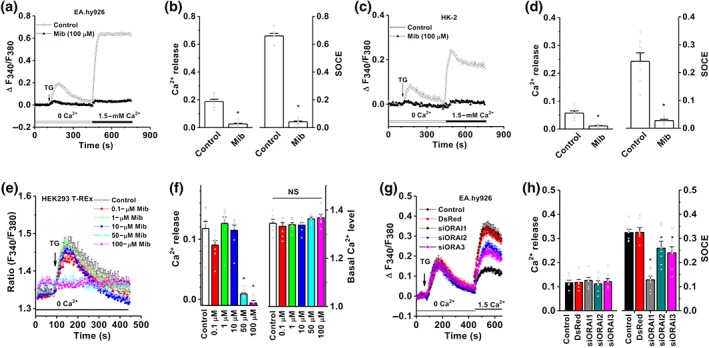

3.5. Effects of mibefradil on ER Ca2+ release and store‐operated Ca2+ entry

The effects of mibefradil on Ca2+ release were examined in the EA.hy926 cells, HK‐2 cells, and HEK‐293 T‐REx cells. The thapsigargin‐induced ER Ca2+ release was significantly inhibited by high concentrations of mibefradil (100 μM) in EA.hy926 cells and HK‐2 cells (Figure 6a–d). Similar inhibitory effects on Ca2+ release was seen in HEK‐293 T‐REx cells; however, lower concentrations of mibefradil (0.1–10 μM) had no significant effect on Ca2+ release, and there were no significant effects on basal intracellular Ca2+ level (Figure 6e,f). The inhibitory effect of mibefradil on ER Ca2+ release seemed to be unrelated to the Orai channels, because transfection of Orai siRNAs significantly reduced store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), but had no influence on ER Ca2+ release (Figure 6g,h). Similar siRNA result was observed in the HK‐2 cells as we described previously (Zeng et al., 2017). These results suggest that other mechanisms could be involved in the inhibition of ER Ca2+ release by mibefradil. As expected, mibefradil nearly abolished the SOCE in both EA.hy926 cells and HK‐2 cells (Figure 6a–d).

Figure 6.

ER Ca2+ release and SOCE inhibited by mibefradil and silencing of SOCE by Orai siRNAs. (a) Vascular endothelial cells EA.hy926 were loaded with Fura‐PE3/AM, and the ER Ca2+ release was induced by 1‐μM thapsigargin (TG). The fluorescence at a ratio of F340/380 was monitored in the group with or without pretreatment with mibefradil. The SOCE was evoked by refilling 1.5‐mM Ca2+ in the bath solution. (b) Mean data were measured at the peak of Ca2+ release or peak of SOCE (n = 8). (c) ER Ca2+ release and SOCE in HK‐2 cells. (d) Mean data for HK‐2 cells (n = 8). (e) Effects of mibefradil at different concentrations on ER Ca2+ release in HEK‐293 T‐REx cells. (f) Mean data for the effect on Ca2+ release and basal Ca2+ level (n = 8). (g) After transfection with Orai siRNAs (siOrai1, siOrai2, and siOrai3) and the control report fluorescence protein (DsRed) for 48 hr, ER Ca2+ release and SOCE were detected by FlexStation 3. (h) Mean ± SEM data for the groups of control (sham transfection); a red fluorescent protein report gene (DsRed); and Orai1‐3 siRNAs (n = 8 for each group). *P < .05, significantly different from control

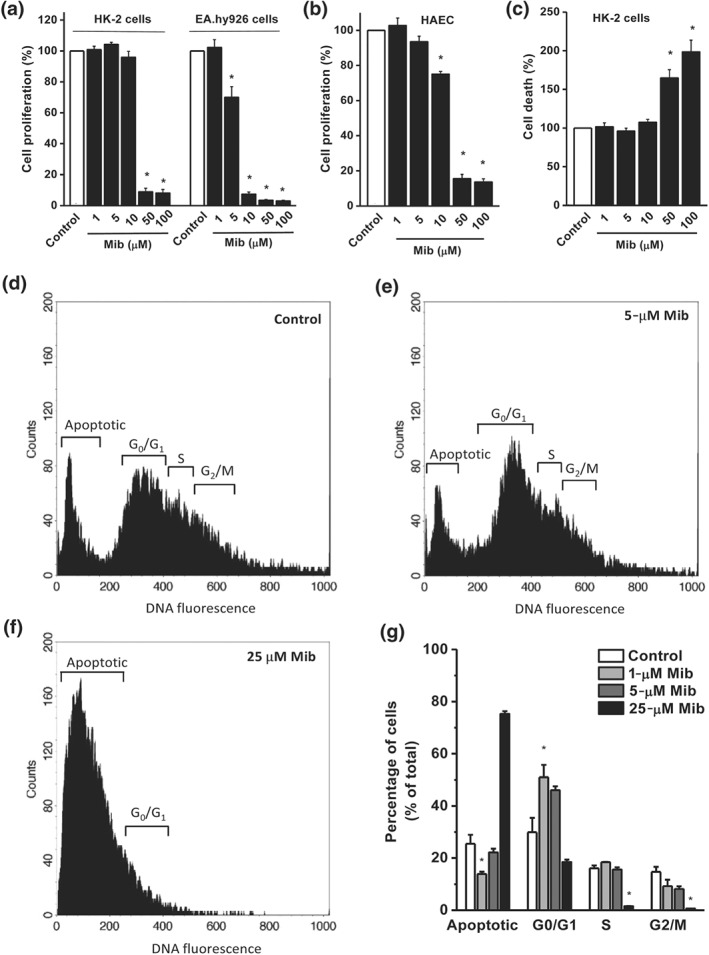

3.6. Effect of mibefradil on cell proliferation and cell death

Anti‐tumour effects have been demonstrated for mibefradil (Haverstick, Heady, Macdonald, & Gray, 2000; Santoni, Santoni, & Nabissi, 2012) and we, therefore, tested the effects of mibefradil on cell proliferation and cell death using in vitro cell models. Mibefradil significantly inhibited the proliferation of two immortalized cell lines (HK‐2 and EA.hy926 cells) and the primary cultures of normal HAECs. The EC50 values for anti‐proliferation for HK‐2, EA.hy926, and HAEC were 28.2, 5.9, and 14.2 μM respectively (Figure 7a,b), suggesting that the inhibition of proliferation in endothelial cells is more sensitive to mibefradil than that in HK‐2 cells, which could be due to higher expression level of Orai channels in endothelial cells (Figure S2). Mibefradil also significantly induced cell death as assayed by LDH release (Figure 7c). The effect of mibefradil on cell cycle was examined using flow cytometry. Lower concentrations of mibefradil (1, 5 μM) increased the percentage of cells at G0/G1 but at high concentrations decreased the percentage of cells at S phase and G2/M phase (Figure 7d–g).

Figure 7.

Effect of mibefradil on cell proliferation and cell death. The cell proliferation was monitored by WST‐1 assay, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm with a reference at 650 nm. (a) Effect of mibefradil on the cell proliferation of HK‐2 cells and EA.hy926 cells (n = 8 for each group). (b) Effect on human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs; n = 8). (c) HK‐2 cell death was detected by LDH release assay (n = 8). (d–f) Effect of mibefradil on cell cycle. Cells were stained with propidium iodide, and the percentage of propidium iodide ‐labelled cells at different cell cycle stage was determined by FACS analysis. A representative FACS histogram for vehicle (d, Control) and mibefradil (5, 25 μM) for (e,f). (g) Mean ± SEM data from independent experiments (n = 6). *P < .05, significantly different from control

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we have found that Orai channels are blocked by mibefradil. The blocking effect is concentration‐dependent and reversible. The action site is located on the extracellular cell surface. High concentrations of mibefradil not only reduce SOCE but also inhibit Ca2+ release from ER. Mibefradil also significantly inhibited cell proliferation and promoted cell apoptosis by arresting the progression of the cell cycle from G1/G0 to S phase, and to G2/M phase. These findings provide a new pharmacological profile for mibefradil, which is commonly used as a blocker of T‐type Ca2+ channels and has recently been repurposed as an anti‐cancer drug.

Orai channels are the main components of SOCE in the endothelial cells and HK‐2 cells, which has been demonstrated by gene silencing using Orai siRNAs in this study and our previous report (Zeng et al., 2017). Mibefradil at high concentrations almost abolished the SOCE in the two cell types tested. Effect on Orai subtypes has been compared using an inducible overexpressing system, and mibefradil is a more potent blocker of Orai3 channels than of Orai1 and Orai2 channels. The EC50 for Orai channel blockade is similar to the EC50 for blocking T‐type Ca2+ channels (Alexander et al., 2017), suggesting that the inhibition of SOCE is one of the main mechanisms of action for the compound. Mibefradil seems to be more effective against the overexpressed T‐type Ca2+ channels than the native T‐type Ca2+ channels, such as T channel isoforms α1G, α1H, and α1I, all with an EC50 around 1 μM (Martin et al., 2000). As inhibition of SOCE or Orai channels has been demonstrated as anti‐proliferative in several types of normal and cancer cells (Konig et al., 2013; Umemura et al., 2014; Vaeth et al., 2017), the anti‐cancer effect of mibefradil could be explained at least in part due to the block of Orai channels, rather than the block of T‐type Ca2+ channels, although the T‐type channels are highly expressed in some types of cancer and have been regarded as possible therapeutic targets for regulating cancer cell growth and death (Zhang et al., 2017).

We have explored the site of action of mibefradil using outside‐out patch and whole‐cell patch with intracellular drug application. Mibefradil inhibited the Orai3 current and abolished the single channel open probability, when applied extracellularly, suggesting that Orai channels show a druggable target on the external surface of the cell. The slope conductance of 2‐APB‐activated Orai3 channels was 71 pS in this study, a value much larger than the chord conductance estimated at a holding potential of −100 mV by noise analysis method in divalent‐free solution (Yamashita & Prakriya, 2014). This discrepancy could be due to the differences of bath solution and/or 2‐APB concentration. However, direct single channel event detection using step voltage protocol in this study is clearer and more accurate than the noise analysis method. In addition, mibefradil had no effect on cytosolic STIM1 clustering and movement, suggesting that the block by mibefradil is on the channel protein itself. The ER Ca2+ release is an initial step in the activation of Orai channels and then causes SOCE; Mibefradil at lower concentrations (<10 μM) has no significant effect on ER Ca2+ release, which is consistent with the report on calcium transient and spontaneous rhythmic calcium oscillations (Lowie, Wang, White, & Huizinga, 2011). However, the inhibition of Ca2+ release by mibefradil was significant at high concentrations, which could be a mechanism of its cytotoxicity. We have also analysed the basal intracellular Ca2+ level and mibefradil seems to have no significant effects on the basal Ca2+ level in our acute in vitro Ca2+ detection using Flexstation.

The effect of mibefradil on cell proliferation and death was investigated in this study. Mibefradil potently inhibited the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells (HAECs and EA.hy926 cells). This result is in accordance with the reports on calf pulmonary artery endothelial cells (Nilius et al., 1997), rat microvascular endothelial cells (Manolopoulos et al., 2000), human pulmonary smooth muscle cells (Rodman et al., 2005), and some cell lines (U87, N1E‐115, and COS7; Panner & Wurster, 2006). Orai channels are highly expressed in human proximal tubular cells and are involved in the protein reabsorption (Zeng et al., 2017), while T‐type Ca2+ channel could play a role in calcium reabsorption (Leclerc, Brunette, & Couchourel, 2004). We found that high concentrations of mibefradil (>25 μM) cause apoptosis of proximal tubular cells, suggesting that mibefradil may impair kidney function. We have also observed the effect of mibefradil on the cell cycle. Mibefradil treatment increased the HK‐2 cell numbers at G0/G1 phase and decreased the cell numbers in G2/M, suggesting the cell cycle progressing from G1 to S, and G2 to M phase is arrested. This finding is similar to the reports on ovarian cancer cells (Dziegielewska et al., 2016) and Jurkat cells (Huang, Lu, Wu, Ouyang, & Chen, 2015), which could be related to Ca2+ signalling in the initiation of DNA synthesis (G1 to S phase) and mitosis (G2 to M phase; Panner & Wurster, 2006). However, high concentrations of mibefradil (i.e., more than 25 μM) could show non‐specific cytotoxicity by stimulating apoptosis and reducing the cell population at G0/G1 phase, as more specific tools to inhibit Ca2+ permeable channels, such as siRNAs, mainly increase the cell population at G2/M phase, rather than reduce the cell numbers at G2/M phase (Cai et al., 2009; Zeng, Yuan, Yang, Atkin, & Xu, 2013). The significant inhibition of Ca2+ release by high concentrations of mibefradil should impair intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and thus change cell viability. Several studies have demonstrated the critical roles of Orai channels and STIMs in apoptosis, and cancer migration and metastasis (Faouzi et al., 2011; Jardin & Rosado, 2016; Tanwar & Motiani, 2018). We have shown potent inhibition of Orai channels by mibefradil in this study, for example, the EC50 of 3.8 μM for ORAI3. It is therefore reasonable to speculate that the anti‐tumour effect of mibefradil could also be mediated by inhibition of Orai channels, when high doses are used for cancer therapy (150–350 mg·day−1, ClinicalTrials ID: NCT02202993) and the maximum plasma concentration may achieve several μg per litre (Holdhoff et al., 2017; Welker, Wiltshire, & Bullingham, 1998).

Apart from the inhibition of Orai channels, mibefradil also inhibits K+ channels, such as Kv10.1 channels (Gomez‐Lagunas, Carrillo, Pardo, & Stuhmer, 2017), ATP‐activated K + channels (Gomora, Enyeart, & Enyeart, 1999), and two P domain potassium channels (Czirjak & Enyedi, 2006); and Ca2+‐activated Cl − channels (Nilius et al., 1997). It has also been demonstrated to activate TRPM7 channels but the effective concentration is much higher with an EC50 of 53 μM (Schafer et al., 2016). Mibefradil had no effects on TRPM3, TRPV1, and TRPA1 channels, suggesting that mibefradil has some selectivity between cation channels. We have also examined other T‐channel blockers, such as ML218 and ethosuximide, with different chemical structures. The two compounds have no or small effect on Orai channels , suggesting that the blocking effect of mibefradil on these channels is specific for its chemical structure and unrelated to a class effect of T‐type Ca2+ channel blockade.

In conclusion, our data suggest a new pharmacological profile for mibefradil, which acts as a pan inhibitor for Orai channels. The specific action site for mibefradil on Orai channels is accessible via the extracellular surface, which could be developed as a new target for compound screening or future potential anti‐proliferative drug development.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.L. performed the cell culture, Ca2+ measurement, and patch clamp and analysed the data. H.N.R. performed the outside‐out patch clamp and contributed part of whole‐cell recording data. G.L.C. performed the patch clamp. T.H. performed Ca2+ measurement. N.Z. and R.S. performed the cell growth and death experiments. P.L. and B.Z. performed the STIM1–EYFP movement experiment. S.Z.X initiated the project, generated the ideas and research funds, led the project, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for Design & Analysis, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1.

STIM1 subplasmalemmal translocation and clustering after Ca2+ store depletion in the stable transfected STIM1–EYFP cells and the effect of mibefradil (Mib). (A) Thapsigargin (TG: 1 μM) induced STIM1 puncta formation at the plasma membrane. The arrow indicates the subplasmalemmal STIM1 clusters (puncta). (B) Cells pretreated with mibefradil (50 μM) and then added with thapsigargin (1 μM). The upper enlarged photos are the boxed area shown in the lower panels. (C) Cells treated with mibefradil (50 μM) for 10 min alone and compared with control. The upper enlarged photos are the boxed area shown in the lower panels. All images were taken by an epi‐fluorescence microscopy with Z‐stack imaging. The perimeter plasma membrane with Z‐section in the middle of a cell was analysed. (D) The number of STIM1 puncta per cell induced by thapsigargin (TG) for 10 min and the effect of mibefradil (50 μM) (n = 104, 77, 86, and 94 for control, TG (1 μM), mibefradil (50 μM), and TG (1 μM) + mibefradil (50 μM), respectively). The mean ± SEM data are pooled from 5 independent experiments and presented with individual data points. *P < 0.05 compared with control, n.s., non‐significant.

Figure S2. Comparison of mRNA expression of ORAI1–3 in EA.hy926 and HK‐2 cells. The mRNA level was quantified by real‐time PCR. The primer set and experimental procedures were detailed in our previous report (Daskoulidou et al., 2015). β‐Actin was used for relative quantification and triplicate reactions were set for each sample detection. *P < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement 115974. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA with JDRF (to S.Z.X.). P.L. received National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600381) and the scholarship from China Scholarship Council as a visiting scholar to Hull York Medical School. T.H. received University PhD studentship.

Li P, Rubaiy HN, Chen G‐L, et al. Mibefradil, a T‐type Ca2+ channel blocker also blocks Orai channels by action at the extracellular surface. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;114:3845–3856. 10.1111/bph.14788

REFERENCES

- Abdullaev, I. F. , Bisaillon, J. M. , Potier, M. , Gonzalez, J. C. , Motiani, R. K. , & Trebak, M. (2008). Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store‐operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circulation Research, 103, 1289–1299. 10.1161/01.RES.0000338496.95579.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. , Striessnig, J. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Voltage‐gated ion channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(Suppl 1), S160–S194. 10.1111/bph.13884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier, W. , Oh‐Hora, M. , McCarl, C. A. , Roden, R. C. , Bray, P. F. , & Feske, S. (2009). R93W mutation in Orai1 causes impaired calcium influx in platelets. Blood, 113, 675–678. 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny, I. , & Tsien, R. W. (1995). Voltage‐dependent blockade of diverse types of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by the Ca2+ channel antagonist mibefradil (Ro 40‐5967). Molecular Pharmacology, 48, 540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, A. , Varga‐Szabo, D. , Kleinschnitz, C. , Pleines, I. , Bender, M. , Austinat, M. , … Nieswandt, B. (2009). Orai1 (CRACM1) is the platelet SOC channel and essential for pathological thrombus formation. Blood, 113, 2056–2063. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, R. , Ding, X. , Zhou, K. , Shi, Y. , Ge, R. , Ren, G. , … Wang, Y. (2009). Blockade of TRPC6 channels induced G2/M phase arrest and suppressed growth in human gastric cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer, 125, 2281–2287. 10.1002/ijc.24551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Alexander, S. , Cirino, G. , Docherty, J. R. , George, C. H. , Giembycz, M. A. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 987–993. 10.1111/bph.14153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirjak, G. , & Enyedi, P. (2006). Zinc and mercuric ions distinguish TRESK from the other two‐pore‐domain K+ channels. Molecular Pharmacology, 69, 1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskoulidou, N. , Zeng, B. , Berglund, L. M. , Jiang, H. , Chen, G. L. , Kotova, O. , … Xu, S. Z. (2015). High glucose enhances store‐operated calcium entry by upregulating ORAI/STIM via calcineurin‐NFAT signalling. Journal of Molecular Medicine (Berlin, Germany), 93, 511–521. 10.1007/s00109-014-1234-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziegielewska, B. , Casarez, E. V. , Yang, W. Z. , Gray, L. S. , Dziegielewski, J. , & Slack‐Davis, J. K. (2016). T‐type Ca2+ channel inhibition sensitizes ovarian cancer to carboplatin. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 15, 460–470. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faouzi, M. , Hague, F. , Potier, M. , Ahidouch, A. , Sevestre, H. , & Ouadid‐Ahidouch, H. (2011). Down‐regulation of Orai3 arrests cell‐cycle progression and induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells but not in normal breast epithelial cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 226, 542–551. 10.1002/jcp.22363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske, S. , Gwack, Y. , Prakriya, M. , Srikanth, S. , Puppel, S. H. , Tanasa, B. , … Rao, A. (2006). A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature, 441, 179–185. 10.1038/nature04702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez‐Lagunas, F. , Carrillo, E. , Pardo, L. A. , & Stuhmer, W. (2017). Gating modulation of the tumor‐related Kv10.1 Channel by mibefradil. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 232, 2019–2032. 10.1002/jcp.25448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomora, J. C. , Daud, A. N. , Weiergraber, M. , & Perez‐Reyes, E. (2001). Block of cloned human T‐type calcium channels by succinimide antiepileptic drugs. Molecular Pharmacology, 60, 1121–1132. 10.1124/mol.60.5.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomora, J. C. , Enyeart, J. A. , & Enyeart, J. J. (1999). Mibefradil potently blocks ATP‐activated K(+) channels in adrenal cells. Molecular Pharmacology, 56, 1192–1197. 10.1124/mol.56.6.1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverstick, D. M. , Heady, T. N. , Macdonald, T. L. , & Gray, L. S. (2000). Inhibition of human prostate cancer proliferation in vitro and in a mouse model by a compound synthesized to block Ca2+ entry. Cancer Research, 60, 1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdhoff, M. , Ye, X. , Supko, J. G. , Nabors, L. B. , Desai, A. S. , Walbert, T. , … Schiff, D. (2017). Timed sequential therapy of the selective T‐type calcium channel blocker mibefradil and temozolomide in patients with recurrent high‐grade gliomas. Neuro‐Oncology, 19, 845–852. 10.1093/neuonc/nox020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. , Lu, C. , Wu, Y. , Ouyang, S. , & Chen, Y. (2015). T‐type calcium channel antagonists, mibefradil and NNC‐55‐0396 inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell apoptosis in leukemia cell lines. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 34, 54 10.1186/s13046-015-0171-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin, I. , & Rosado, J. A. (2016). STIM and calcium channel complexes in cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1863, 1418–1426. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig, S. , Browne, S. , Doleschal, B. , Schernthaner, M. , Poteser, M. , Machler, H. , … Groschner, K. (2013). Inhibition of Orai1‐mediated Ca(2+) entry is a key mechanism of the antiproliferative action of sirolimus in human arterial smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 305, H1646–H1657. 10.1152/ajpheart.00365.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc, M. , Brunette, M. G. , & Couchourel, D. (2004). Aldosterone enhances renal calcium reabsorption by two types of channels. Kidney International, 66, 242–250. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00725.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. S. , Goodman, S. , Dean, D. M. , Lenis, J. , Ma, P. , Gervais, P. B. , … PRIDE Investigators (2002). Randomized comparison of T‐type versus L‐type calcium‐channel blockade on exercise duration in stable angina: Results of the Posicor Reduction of Ischemia During Exercise (PRIDE) trial. American Heart Journal, 144, 60–67. 10.1067/mhj.2002.122869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, B. J. , Wang, X. Y. , White, E. J. , & Huizinga, J. D. (2011). On the origin of rhythmic calcium transients in the ICC‐MP of the mouse small intestine. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 301, G835–G845. 10.1152/ajpgi.00077.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolopoulos, V. G. , Liekens, S. , Koolwijk, P. , Voets, T. , Peters, E. , Droogmans, G. , … Nilius, B. (2000). Inhibition of angiogenesis by blockers of volume‐regulated anion channels. General Pharmacology, 34, 107–116. 10.1016/S0306-3623(00)00052-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. L. , Lee, J. H. , Cribbs, L. L. , Perez‐Reyes, E. , & Hanck, D. A. (2000). Mibefradil block of cloned T‐type calcium channels. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 295, 302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S. K. , & Hermsmeyer, K. (1994). Selective inhibition of T‐type Ca2+ channels by Ro 40‐5967. Circulation Research, 75, 144–148. 10.1161/01.RES.75.1.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius, B. , Prenen, J. , Kamouchi, M. , Viana, F. , Voets, T. , & Droogmans, G. (1997). Inhibition by mibefradil, a novel calcium channel antagonist, of Ca(2+)‐ and volume‐activated Cl‐ channels in macrovascular endothelial cells. British Journal of Pharmacology, 121, 547–555. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panner, A. , & Wurster, R. D. (2006). T‐type calcium channels and tumor proliferation. Cell Calcium, 40, 253–259. 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M. , Feske, S. , Gwack, Y. , Srikanth, S. , Rao, A. , & Hogan, P. G. (2006). Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature, 443, 230–233. 10.1038/nature05122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodman, D. M. , Reese, K. , Harral, J. , Fouty, B. , Wu, S. , West, J. , … Cribbs, L. (2005). Low‐voltage‐activated (T‐type) calcium channels control proliferation of human pulmonary artery myocytes. Circulation Research, 96, 864–872. 10.1161/01.RES.0000163066.07472.ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni, G. , Santoni, M. , & Nabissi, M. (2012). Functional role of T‐type calcium channels in tumour growth and progression: Prospective in cancer therapy. British Journal of Pharmacology, 166, 1244–1246. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01908.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, S. , Ferioli, S. , Hofmann, T. , Zierler, S. , Gudermann, T. , & Chubanov, V. (2016). Mibefradil represents a new class of benzimidazole TRPM7 channel agonists. Pflügers Archiv, 468, 623–634. 10.1007/s00424-015-1772-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SoRelle, R. (1998). Withdrawal of Posicor from market. Circulation, 98, 831–832. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.9.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar, J. , & Motiani, R. K. (2018). Role of SOCE architects STIM and Orai proteins in cell death. Cell Calcium, 69, 19–27. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak, M. (2012). STIM/Orai signalling complexes in vascular smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology, 590, 4201–4208. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura, M. , Baljinnyam, E. , Feske, S. , De Lorenzo, M. S. , Xie, L. H. , Feng, X. , … Iwatsubo, K. (2014). Store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) regulates melanoma proliferation and cell migration. PLoS ONE, 9, e89292 10.1371/journal.pone.0089292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth, M. , Maus, M. , Klein‐Hessling, S. , Freinkman, E. , Yang, J. , Eckstein, M. , … Feske, S. (2017). Store‐operated Ca(2+) entry controls clonal expansion of T cells through metabolic reprogramming. Immunity, 47, 664–679 e666. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Deng, X. , Mancarella, S. , Hendron, E. , Eguchi, S. , Soboloff, J. , … Gill, D. L. (2010). The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science, 330, 105–109. 10.1126/science.1191086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker, H. A. , Wiltshire, H. , & Bullingham, R. (1998). Clinical pharmacokinetics of mibefradil. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 35, 405–423. 10.2165/00003088-199835060-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z. , Thompson, A. D. , Brogan, J. T. , Schulte, M. L. , Melancon, B. J. , Mi, D. , … Lindsley, C. W. (2011). The discovery and characterization of ML218: A novel, centrally active T‐type calcium channel inhibitor with robust effects in STN neurons and in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2, 730–742. 10.1021/cn200090z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Z. , Zeng, B. , Daskoulidou, N. , Chen, G. L. , Atkin, S. L. , & Lukhele, B. (2012). Activation of TRPC cationic channels by mercurial compounds confers the cytotoxicity of mercury exposure. Toxicological Sciences, 125, 56–68. 10.1093/toxsci/kfr268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Z. , Zhong, W. , Watson, N. M. , Dickerson, E. , Wake, J. D. , Lindow, S. W. , … Atkin, S. L. (2008). Fluvastatin reduces oxidative damage in human vascular endothelial cells by upregulating Bcl‐2. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 6, 692–700. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, M. , & Prakriya, M. (2014). Divergence of Ca(2+) selectivity and equilibrium Ca(2+) blockade in a Ca(2+) release‐activated Ca(2+) channel. The Journal of General Physiology, 143, 325–343. 10.1085/jgp.201311108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B. , Chen, G. L. , Daskoulidou, N. , & Xu, S. Z. (2014). The ryanodine receptor agonist 4‐chloro‐3‐ethylphenol blocks ORAI store‐operated channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171, 1250–1259. 10.1111/bph.12528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B. , Chen, G. L. , Garcia‐Vaz, E. , Bhandari, S. , Daskoulidou, N. , Berglund, L. M. , … Xu, S. Z. (2017). ORAI channels are critical for receptor‐mediated endocytosis of albumin. Nature Communications, 8, 1920 10.1038/s41467-017-02094-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B. , Chen, G. L. , & Xu, S. Z. (2012). Store‐independent pathways for cytosolic STIM1 clustering in the regulation of store‐operated Ca(2+) influx. Biochemical Pharmacology, 84, 1024–1035. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B. , Yuan, C. , Yang, X. , Atkin, S. L. , & Xu, S. Z. (2013). TRPC channels and their splice variants are essential for promoting human ovarian cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Current Cancer Drug Targets, 13, 103–116. 10.2174/156800913804486629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Cruickshanks, N. , Yuan, F. , Wang, B. , Pahuski, M. , Wulfkuhle, J. , … Abounader, R. (2017). Targetable T‐type calcium channels drive glioblastoma. Cancer Research, 77, 3479–3490. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.

STIM1 subplasmalemmal translocation and clustering after Ca2+ store depletion in the stable transfected STIM1–EYFP cells and the effect of mibefradil (Mib). (A) Thapsigargin (TG: 1 μM) induced STIM1 puncta formation at the plasma membrane. The arrow indicates the subplasmalemmal STIM1 clusters (puncta). (B) Cells pretreated with mibefradil (50 μM) and then added with thapsigargin (1 μM). The upper enlarged photos are the boxed area shown in the lower panels. (C) Cells treated with mibefradil (50 μM) for 10 min alone and compared with control. The upper enlarged photos are the boxed area shown in the lower panels. All images were taken by an epi‐fluorescence microscopy with Z‐stack imaging. The perimeter plasma membrane with Z‐section in the middle of a cell was analysed. (D) The number of STIM1 puncta per cell induced by thapsigargin (TG) for 10 min and the effect of mibefradil (50 μM) (n = 104, 77, 86, and 94 for control, TG (1 μM), mibefradil (50 μM), and TG (1 μM) + mibefradil (50 μM), respectively). The mean ± SEM data are pooled from 5 independent experiments and presented with individual data points. *P < 0.05 compared with control, n.s., non‐significant.

Figure S2. Comparison of mRNA expression of ORAI1–3 in EA.hy926 and HK‐2 cells. The mRNA level was quantified by real‐time PCR. The primer set and experimental procedures were detailed in our previous report (Daskoulidou et al., 2015). β‐Actin was used for relative quantification and triplicate reactions were set for each sample detection. *P < 0.05.