Abstract

Context/objective: The spinal cord injury (SCI) knowledge mobilization network (KMN) is a community of practice formed in 2011 as part of a national best practice implementation (BPI) effort to improve SCI care. This study objective was to determine whether completion and documentation of pain practices could be improved in a neurorehabilitation setting using the KMN implementation approach.

Design: Single site, pre–post intervention study.

Setting: Neurorehabilitation hospital.

Participants: Twenty sequential consenting inpatients with SCI, with retrospective comparative analysis of 50 sequential SCI admissions pre-KMN.

Interventions: A local Site Implementation Team (SIT) was formed to develop an implementation plan, including acceptable timeframes for completion and documentation of four specific pain best practices: (1) pain assessment on admission, (2) development of an Inter-Professional Pain Treatment Plan (IPTP), (3) pain monitoring throughout admission, and (4) a pain discharge plan.

Outcomes: Provider adherences to pain best practices were the primary outcomes. The secondary outcome was patient satisfaction.

Results: Provider adherence for most outcomes exceeded 70% completion within acceptable timeframes, with improvements found for all outcomes as compared to the retrospective cohort. Notably, pain education as part of the IPTP improved from 12% completion to 74%, documenting pain onset from 4.5% to 80% and pain discharge plan from 40% to 74%. Overall, participants were satisfied with their pain management.

Conclusions: Pain best practices were more consistently documented after the KMN implementation. Pain practices in all four areas have now been expanded to all inpatient diagnoses using the same forms and framework created in the implementation process.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Rehabilitation, Implementation, Pain management

Introduction

The reported prevalence of pain in persons with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) ranges between 26 and 96%1 with as many as one-third reporting severe pain levels.2 Over two-thirds of patients who suffer from neuropathic SCI pain do not receive adequate pain relief or management from their current treatments.3 Managing pain in SCI is not an easy task and requires a diverse approach.

A multidisciplinary interprofessional approach to pain management has been shown to be more effective compared to standard methods of SCI pain management.4,5 In addressing an individual’s pain concerns, a multidisciplinary interprofessional approach includes a comprehensive pain management plan created with the patient’s input and shared among healthcare disciplines.5 The plan should span the SCI care continuum from acute care to rehabilitation and include an interdisciplinary discharge plan that aims to manage pain on a long-term basis as the person transitions into the community.

Despite significant progress in knowledge transfer, the translation of research findings into clinical practice remains a challenge.6–8 Prior studies in SCI inpatient rehabilitation demonstrate that simply publishing evidence or guidelines is not sufficient to impact practice.9–11 Strategies to promote uptake and sustainability of new practices has been the focus of implementation science. Specifically, implementation science is ‘the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services’ (p. 1).12 Implementation science provides frameworks to support meaningful implementation of evidence-based practices, which increases the likelihood of sustainable practice change.13–15

The Spinal Cord Injury Knowledge Mobilization Network (SCI KMN) is a community of practice formed in 2011 which includes seven Canadian rehabilitation hospitals. The three main objectives of the SCI KMN are (1) to develop and apply SCI practice resources using implementation science, (2) to strengthen and sustain knowledge mobilization infrastructure and environments, and (3) to contribute to the evidence base. In 2016, the SCI KMN created an implementation guide, adapted from the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) Active Implementation Frameworks.16 A modified Delphi process17 identified and recommended best pain practices for inpatient SCI.

With the support of the SCI KMN, our inpatient rehabilitation program that treats multiple neurological diagnoses (SCCR: Stan Cassidy Centre for Rehabilitation) sought to optimize the uptake of evidence-based pain practices in inpatients with SCI. The SCI KMN implementation framework with four stages (exploration, installation, initial implementation and full implementation) was used to develop and apply pain practices recommended by the SCI KMN.18,19 Four specific pain practices were selected and implemented into the interdisciplinary care of persons with SCI admitted into inpatient rehabilitation using the implementation frameworks. These included (1) an assessment of pain on admission, (2) development of an Interdisciplinary Pain Treatment Plan (IPTP), (3) daily pain intensity monitoring and (4) development of a pain discharge plan.

As a Quality Improvement initiative, the primary purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the implementation framework on provider adherence to pain best practices in the inpatient rehabilitation of persons with SCI. The main objectives were to determine whether the systematic, interdisciplinary management approach would improve the interdisciplinary team’s adherence to pain best practices and patient-reported satisfaction with pain management.

Methods

Implementation methods

A local Site Implementation Team (SIT) was formed upon joining the SCI KMN, with a mandate to be accountable for the implementation and sustainability of the new best practices recommended by the SCI KMN. The SIT was led by a knowledge mobilization specialist who coordinated the implementation activities and consulted with the National KMN team and an implementation science expert. The SIT consisted of clinicians from various disciplines (Nursing, Occupational Therapy, Physiatry, Physiotherapy and Psychology) who assess and treat pain within the adult rehabilitation team.

The SIT met monthly for 15 months prior to implementation to examine what pain practices to adopt (exploration) and how to implement them (installation). The main activities in the installation stage were to describe and define the pain practices selected and to establish measures of provider adherence to the pain practices (see Table 1). Implementation barriers and drivers were explored as part of this stage. Drivers and facilitators of change; ensuring adequate support at all levels of service provision (i.e. social, organizational, and professional), creation of a communication and training plan with providers, and optimization of logistics (e.g. having forms and assessment tools ready and placed on the patient’s medical chart), were addressed. Training was provided to all providers responsible for pain management on the inpatient team through a series of inservices. This included one two-hour session for all providers and an additional one-hour session for nursing.

Table 1. Description of SCI KMN pain practices.

| Pain practice | Activity | Provider adherence measures |

|---|---|---|

| Pain assessment on admission | • Patient history and clinical exam • International SCI Basic Pain Dataset (ISCIBPDS 2.0) |

• Percentage (%) of patients with completed and documented pain assessment within 7 days of admission |

| Interdisciplinary pain treatment plan (IPTP) | • Development of an IPTP at case conference • Review of IPTP with patient by case coordinator once the IPTP is developed • Review and update of IPTP at case conference every two weeks |

Percentage (%) of patients with • IPTP within 14 days of admission • IPTP discussed with patient within 7 days of development of the initial IPTP |

| Pain monitoring & pain education | • Daily monitoring of pain intensity on Numeric Rating Scale (0–10) • Review of patient’s concerns and expectations by the case coordinator within two weeks of admission and reviewed every two weeks thereafter • Education on SCI pain management is provided after the IPTP is developed |

Percentage (%) of patients with • documented daily pain intensity ratings by nursing • documented review of patient concerns and expectations within two weeks of admission • documented pain education within 14 days of the development of the IPTP |

| Pain assessment at discharge | • Patient history and clinical exam • International SCI Basic Pain Dataset (ISCIBPDS 2.0) • Development of a pain discharge plan that is reviewed with the patient |

• Percentage (%) of patients with completed, documented and reviewed pain assessment within 72 h of discharge |

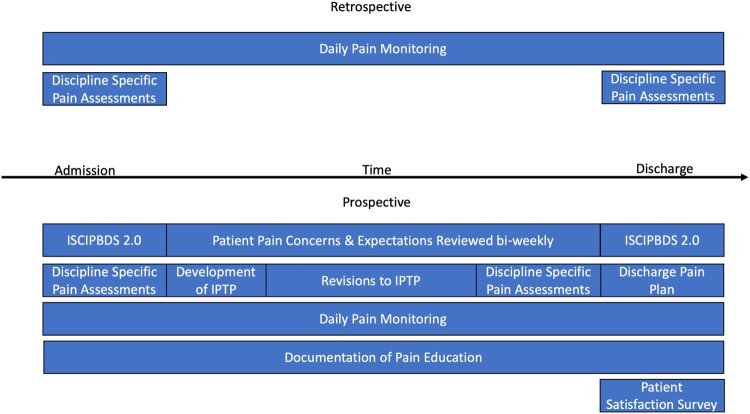

During the initial implementation stage, the SIT was responsible for supporting the practice implementation, measuring provider adherence and collecting the data. Regular chart audits were completed to evaluate the team’s adherence to the practices. The communication plan was initiated to give reminders of practices to be followed, to solicit feedback from providers on the practice implementation and update providers of ongoing results. Posters placed in key provider areas (e.g. nursing station, case conference room, washrooms) informed providers of the four pain practices, and reminded them to complete the pain assessments. Monthly meetings of the adult team are a regular activity of the SCCR and ‘KMN’ was added as a routine agenda item. Throughout the study, providers were given opportunities to offer feedback to the SIT members. Implementation challenges raised by providers were addressed in various ways. Challenges that involved lack of clarity of practices or recall of the expected timeframes for completion of activities were addressed through more frequent reminders or coaching and mentorship by the SIT members. Other logistical or administrative issues (e.g. not finding the forms on the chart) were addressed early in the implementation to improve adherence. Following monthly debriefing and solicitation of feedback from providers, implementation strategies were modified and eventually adopted as standard practice (full implementation; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Comparative timeline of pain implementation framework.

Study design

Prospective and retrospective data were collected as part of this study. Rates of provider adherence to pain practices and patient-reported outcomes were collected prospectively for consenting patients with a diagnosis of a SCI who were 15 years of age and older and admitted for an anticipated minimum of 14 days of interdisciplinary SCI rehabilitation. Informed consent procedures were followed as outlined in the SCCR standard of practice for informed consent. Patients were recruited over a 15-month period. As a comparator group, 50 sequential SCI charts from admissions prior to joining the SCI KMN in August 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Applying the same inclusion criteria as above, data were collected on provider adherence rates as part of the retrospective analysis of pain practices. The retrospective data results were used as part of the study training for providers, highlighting current gaps in. Table 2 summarizes the patient demographics from both prospective and retrospective components of the study.

Table 2. Patient demographics.

| Retrospective (SD) | Prospective (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size N | 50 | 20 |

| Age at admission | 45.38 (17.64) | 44.95 (18.46) |

| % Male | 84% male | 80% |

| Traumatic SCI % | 72% | 85% |

| Length of stay (days) | 64.82 (56.63) | 107.15 (94.45) |

| Pain reported on admission | 86% | 85% |

Outcomes

Rates of provider adherence were measured for each of the four pain best practices by reviewing medical records for patients in both the prospective and retrospective components of the study. Specifically, the rates of completion and documentation within acceptable timeframes were calculated for the (1) assessment of pain on admission, (2) development of an Inter-Professional Pain Treatment Plan (IPTP), (3) monitoring of pain throughout admission, and (4) development of a pain discharge plan.

Assessment of pain on admission was multidisciplinary and included the International Spinal Cord Injury Pain Basic Data Set 2.0 (ISCIPBDS 2.0). The ISCIPBDS 2.0 collects information on patient reported pain levels, rates of pain interference with mood, sleep and day-to-day activities, and number of pain problems. For the top three pain problems, the type (neuropathic, nociceptive, mixed), body area, intensity and date of onset are recorded. Pain assessments were to be completed within 7 days of admission. Patients’ concerns and expectations regarding their pain were identified and documented by the case coordinator. As routine practice at the SCCR, a member of each patients’ interdisciplinary team is designated as that patient’s case coordinator during the admission. Duties of the case coordinator include organizing family conferences, communicating with the patient’s family, reviewing goals with the patient, and charting at weekly case conferences.

Data from the ISCIPBDS 2.0, discipline-specific pain assessments and patient concerns and expectations were then discussed by the interdisciplinary team to develop the IPTP within the first two weeks of admission. The IPTP was divided into pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment plans and then shared with the patient. The interdisciplinary team outlined and documented possible pain education to be provided to the patient.

Monitoring of pain throughout admission was documented by nursing staff, with patients asked to rate their pain levels from 0 to 10 at least once per day. Updates to the IPTP were made as required based throughout admission.

Finally, the pain discharge plan was developed within 7 days of discharge. This included repeated completion of the ISCIPBDS 2.0 and other discipline-specific assessments that informed recommendations for pain management at discharge.

A secondary outcome for the prospective group included a patient satisfaction survey. Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire within the 72 h prior to discharge, using a 0–10 scale. Patients were asked about their satisfaction with the pharmacological approach and non-pharmacological approach to pain management, and their satisfaction with pain education received during the admission.

Results

Adherence rates

Provider adherence rates were calculated as the percentage of patients who had documentation of the pain best practices within the target expected timeframe. Not all outcomes were collected in the retrospective dataset as some practices (e.g. use of specific pain assessments such as the ISCIPBDS 2.0 and formal documentation of an IPTP) were introduced because of the implementation efforts after joining the SCI KMN.

Post-KMN, results of adherence rates for assessment of pain on admission showed a high rate of completion, with 85% of patients having a completed ISCIPBDS 2.0 in the medical record. Similarly, patient concerns and expectations were documented in 74% of patient records while initial discipline-specific assessments were completed and documented 84% of the time.

With the addition of the ISCIPBDS 2.0 as an assessment tool, there were improvements in many aspects of pain documentation. This included an increase in the documentation of pain intensity from 43% in the retrospective dataset to 93% prospectively. Date of pain onset was documented 80% of the time compared to only 4.5% retrospectively. Similarly, the type of pain (either nociceptive or neuropathic) was identified in 100% of patients compared to 50% previously when patients were reported to be in pain.

Provider adherence rates for completion and documentation of the IPTP had a moderate rate of completion at 74%. For patients with documented IPTPs, the plan was discussed within seven days of completion 92% of the time. An increase in formal and documented pain education was noted with rates of provider adherence increasing from 12% in the retrospective dataset to 74% after implementation efforts.

The third component of the pain best practices, daily pain intensity monitoring by nursing, had an overall adherence rate of 67%. Closer examination of these findings showed that daily pain intensity monitoring was more consistent in the first half of the study at 82% and declined to 54% in the second half.

Finally, pain discharge plans were created and documented in the medical record for 74% of patients in the study, which is an increase from a 40% rate in the retrospective dataset. Repeat assessment of pain at discharge using the ISCIPBDS 2.0 had a low adherence rate of 35%. Given the low completion at discharge, formal comparison of ISCIPBDS 2.0 from admission to discharge of patient pain intensity and daily interference were not completed.

Secondary outcome

Patients were asked to complete a satisfaction questionnaire within 72 h prior to discharge, using a 0–10 scale with 0 representing “not at all satisfied” and 10 being “completely satisfied”. Overall, rates of satisfaction were high for the pharmacological approach (mean score of 8/10) and non-pharmacological approach (9.1/10) to pain management. Patients also endorsed high rates of satisfaction with the pain education received during their admission (8.5/10).

Discussion

The findings related to provider adherence are consistent with other studies that support implementation frameworks to improve uptake of best practices in various conditions.4,5 Implementation of pain best practices resulted in improved adherence in most targeted areas in the prospective sample of inpatients with SCI. When compared with the retrospective data, improved rates of adherence were noted for the assessment and documentation of pain on admission, pain education as part of an IPTP, and pain-related discharge plans. There was adequate adherence to the development and documentation of an IPTP, provision of pain education for patients, and review of patient’s expectations and concerns related to their pain.

Despite the implementation efforts, the study highlighted certain key practices that were more difficult to maintain throughout the study period. Daily monitoring of pain was documented more consistently post-KMN compared to retrospective findings, but rates of adherence were slightly lower than targeted. Detailed analysis revealed high adherence rates in the first half of the post-KMN study period and a decline in the second half. The decline in adherence is potentially a result of relatively high staff turnover on nursing units than other disciplines, difficulties in training due to shift work, and inability to attend monthly team meetings. To improve adherence, regular training and mentoring in nursing should be encouraged. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to have individuals in each discipline that are committed and are available to assist other staff members within their discipline. The overall adherence to the development and documentation of the IPTP was lower than desired; though when it was completed, it was done within the targeted timeframe (two weeks of admission). The IPTP results suggest that when the provider successfully began the framework or when there were adequate prompts, the provider could complete it adequately. This finding agrees with the findings of Dismukes 2012, suggesting that increased numbers of prompts and training can improve provider adherence.20 Finally, completion rates of the ISCIPBDS 2.0 at admission were much higher than at discharge. Lower rates of repeat assessment of pain at discharge meant that pain outcomes including intensity, type and interference of pain in daily living could not be compared from admission to discharge.

In keeping with studies that have shown mixed results with implementation practices, this current study demonstrated that certain practices were more easily implemented and sustained. In the context of best practice implementation, multiple barriers that include the organizational, social and professional context of an organization have been described.21–23 Organizational barriers to implementation of practices in SCI, were consistent with findings by Noonan and colleagues, who identified issues in funding and resources. SIT members were full time clinicians; this coupled with limited funding, resulted in longer implementation times.24 Inadequate protected time away from clinical service for providers to learn and implement may have interfered with changes in practice. The social context in which providers’ knowledge and practice routines are already ingrained may have also posed barriers to change. Other studies in the implementation of best practice also identified barriers associated with the professional context.21,22,25 This included clinicians’ attitudes that contribute to confidence in making changes, beliefs about their capabilities, low motivation to change, or role confusion as to who is responsible for the new practice. Though coaching and training in the practices was mandatory for the interdisciplinary team in this study, facilitated by the support of the SCCR administrative leaders, closer supervision and coaching may have led to improved provider adherence.

Discipline-specific versus interdisciplinary practices may also have resulted in different rates of adherence. Practices that involved coordination and engagement from the interdisciplinary team (e.g. pain education, IPTP) were less likely to “fall through the cracks”, perhaps as greater accountability was expected in group discussions such as case conferences. In this study, practices tied to one discipline – such as daily pain intensity monitoring by nursing and discharge pain assessment by physiatry – may involve discipline-specific barriers that need to be explored in more detail. Consistent with this finding, McCluskey and colleagues showed that barriers to implementation differed by discipline.25 Falling provider adherence rates for daily pain intensity monitoring and low adherence to the completion of the ISCIPBDS 2.0 at discharge could possibly have been addressed by more frequent feedback with the interdisciplinary team to keep individuals engaged and invested in the pain best practice outcomes.18 Logistical and administrative challenges, such as impractical form placement, may have also hindered adherence rates.

Other findings reflect an improved assessment of patients’ pain experiences. Information on the patient’s pain type (i.e. nociceptive, neuropathic) and date of onset were documented more frequently following implementation of pain best practices. The improved documentation of pain type and onset presents a clearer picture of patients’ pain experiences, which could ultimately guide treatment interventions. Patients’ self-reported outcomes showed general satisfaction with pain education and interventions received during their inpatient admission.

It is also important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. First, the study has a relatively small number of patients, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study occurred in one setting with its unique set of barriers and implementation drivers. Another limitation of this study is that there were no formal assessments of provider feedback and satisfaction, or drivers and barriers included. The rehabilitation center’s staff treat a variety of neurological injuries and disorders. Implementation of practices to a subset of patients can be challenging for providers who are trying to stay abreast of best practices for multiple diagnoses. The “information overload” as described by Grol and Grimshaw is reflected in competing interests and limited resources/time for quality improvement and knowledge translation initiatives.21 Ultimately, this can interfere with optimal uptake and provider engagement.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the implementation framework used was moderately successful. Further training and coaching is likely to improve the provider adherence to meet the predetermined goals of this study. Additionally, it was found that provider leadership is an important driver to achieve success in the implementation of best practices.

Despite study limitations, the implementation of the pain best practices had additional and unintended benefits that included more frequent interdisciplinary discussion at case conferences and better coordination of pain education by the team, keeping team members accountable and building a general awareness of the patient’s progress in managing his or her pain. Because of the heightened awareness of pain issues, pain practices in all four areas have been expanded to inpatients with all neurological diagnoses using the same forms and framework created through this process. Additionally, inpatient and outpatient pain education groups were started to review basic pain education, non-pharmacological strategies to manage pain, and give group members an opportunity to share common pain experiences.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Conflict of interest None.

Funding Statement

This study received joint funding from the Stan Cassidy Foundation and the New Brunswick Health Research Foundation, and also funded by the Rick Hansen Institute and Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the National SCI KMN team for their assistance with Saagar Walia, Jacquie Brown, Carol Scovil and Anna Kras Dupuis providing helpful mentoring for our local implementation efforts, along with members of our Site Implementation Team: Rebecca Mills, Erica de Passillé, Karen Dickinson, Susan Brophy, and Allison Banks.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Horizon Health Network Research Ethics Board.

References

- 1.Dijkers M, Bryce T, Zanca J.. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(1):13–29. PMID: 19533517. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2008.04.0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddall PJ, Loeser JD.. Pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:63–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice AS, et al. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;2011(152):2204–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H.. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology. 2008;47:670–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guy SD, Mehta S, Harvey D, Lau B, Middleton JW, O’Connell C, et al. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guideline for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: recommendations for model systems of care. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:24–27. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanney SR, Castle-Clarke S, Grant J, Guthrie S, Henshall C, Mestre-Ferrandiz J, et al. How long does biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its translation into products, policy, and practice. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-13-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE.. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J.. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(12):510–20. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns SP, Nelson AL, Bosshart HT, Goetz LL, Harrow JJ, Gerhart KD, et al. Implementation of clinical practice guidelines for prevention of thromboembolism in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28(1):33–42. PMID: 15832902. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2005.11753796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz LL, Nelson AL, Guihan M, Bosshart HT, Harrow JJ, Gerhart KD, et al. Provider adherence to implementation of clinical practice guidelines for neurogenic bowel in adults with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28(5):394–406. PMID: 16869086. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2005.11753839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guihan M, Bosshart HT, Nelson A.. Lessons learned in implementing SCI clinical practice guidelines. SCI Nurs. 2004;21(3):136–42. PMID: 15553056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM.. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogden T, Bjornebekk G, Kjobli J, Patras J, Christiansen T, Taraldsen K, Tollefsen N.. Measurement of implementation components ten years after a nationwide introduction of empirically supported programs–a pilot study. Implement SCI. 2012;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC.. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement SCI. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement SCI. 2015;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F.. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa (FL: ): University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. (FMHI Publication #231). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA.. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Evaluat. 2007;12(10). Available from: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertram RM, Blase KA, Fixsen DL.. Improving programs and outcomes: implementation frameworks and organization change. Res Soc Work Practice. 2015 Jul;25(4):477–87. doi: 10.1177/1049731514537687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown J, Mumme L, Guy S, Kras-Dupuis A, Scovil C, Riopelle R, et al. Informing implementation: a practical guide to implementing new practice as informed by the experiences of thee SCI KMN. Rick Hansen Institute and Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dismukes RK. Prospective memory in workplace and everyday situations. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012 Aug 1;21(4):215–20. doi: 10.1177/0963721412447621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grol R, Grimshaw J.. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geerligs L, Rankin NM, Shepard HL, Butow P.. Hospital-based interventions: a systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation process. Implement Sci. 2018;13:36. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0726-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francke AL, Smit MC, De Veer AJE, Mistiaen P.. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noonan VK, Wolfe DL, Thorogood NP, Park SE, Hsieh JT, Eng JJ.. Knowledge translation and implementation in spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(8):578–87. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCluskey A, Vratsistas-Curto A, Schurr K.. Barriers and enablers to implementing multiple stroke guideline recommendations: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:323. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]