Abstract

Background

Appropriate plant architecture can improve the amount of cotton boll opening and allow increased planting density, thus increasing the level of cotton mechanical harvesting and cotton yields. The internodes of cotton fruiting branches are an important part of cotton plant architecture. Thus, studying the molecular mechanism of internode elongation in cotton fruiting branches is highly important.

Results

In this study, we selected internodes of cotton fruiting branches at three different stages from two cultivars whose internode lengths differed significantly. A total of 76,331 genes were detected by transcriptome sequencing. By KEGG pathway analysis, we found that DEGs were significantly enriched in the plant hormone signal transduction pathway. The transcriptional data and qRT-PCR results showed that members of the GH3 gene family, which are involved in auxin signal transduction, and CKX enzymes, which can reduce the level of CKs, were highly expressed in the cultivar XLZ77, which has relatively short internodes. Genes related to ethylene synthase (ACS), EIN2/3 and ERF in the ethylene signal transduction pathway and genes related to JAR1, COI1 and MYC2 in the JA signal transduction pathway were also highly expressed in XLZ77. Plant hormone determination results showed that the IAA and CK contents significantly decreased in cultivar XLZ77 compared with those in cultivar L28, while the ACC (the precursor of ethylene) and JA contents significantly increased. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the GO categories associated with promoting cell elongation, such as cell division, the cell cycle process and cell wall organization, were significantly enriched, and related genes were highly expressed in L28. However, genes related to the sphingolipid metabolic process and lignin biosynthetic process, whose expression can affect cell elongation, were highly expressed in XLZ77. In addition, 2067 TFs were differentially expressed. The WRKY, ERF and bHLH TF families were the top three largest families whose members were active in the two varieties, and the expression levels of most of the genes encoding these TFs were upregulated in XLZ77.

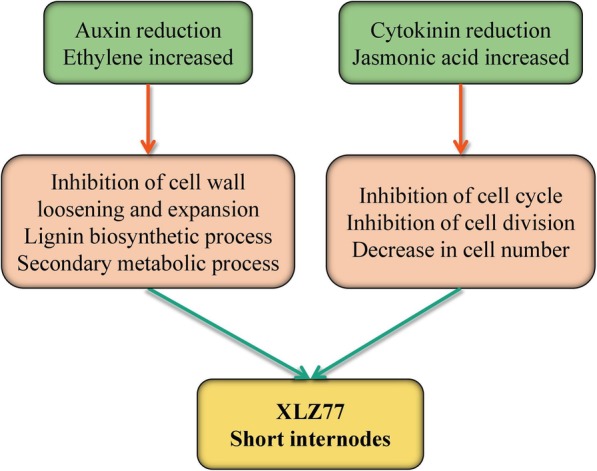

Conclusions

Auxin and CK are positive regulators of internode elongation in cotton branches. In contrast, ethylene and JA may act as negative regulators of internode elongation in cotton branches. Furthermore, the WRKY, ERF and bHLH TFs were identified as important inhibitors of internode elongation in cotton. In XLZ77(a short-internode variety), the mass synthesis of ethylene and amino acid conjugation of auxin led to the inhibition of plant cell elongation, while an increase in JA content and degradation of CKs led to a slow rate of cell division, which eventually resulted in a phenotype that presented relatively short internodes on the fruiting branches. The results of this study not only provide gene resources for the genetic improvement of cotton plant architecture but also lay a foundation for improved understanding of the molecular mechanism of the internode elongation of cotton branches.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-019-2011-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cotton, Plant architecture, RNA-Seq, Internode elongation, Plant hormone, TFs

Background

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is grown worldwide and is an important fiber crop [1]. Appropriately increasing the planting density of cotton plants represents an effective method for increasing cotton yields. However, broad and loose cotton plant architecture has become the key factor limiting increased cotton planting density. Therefore, appropriate plant architecture and colony structure are important for the cultivation of high-yielding cotton.

Plant architecture is a comprehensive representation of plant morphology and structure, physiological and ecological functions, etc. Plant architecture is a key determinant of light reception, photosynthate production, and nutrient partitioning and plays an important role in crop yield, product quality, and cultivation management [2]. In higher plants, formation of plant architecture also encompasses plant morphology-related organs throughout the whole growth and development of the plants, especially the formation, shape and location of the branches, leaves and flowers [3]. Overall, cotton plant architecture comprises several growth components, such as the height of the main stem, both the number and length of the fruiting branches and roots, the internode length of both the main stem and fruiting branches, and the distribution of cotton bolls throughout the whole plant, as well as the cotton growth structure and boll formation. The effects of plant architecture on lint yield are especially important [4]. Architecture can significantly affect the light distribution within and penetration into a crop canopy and thus can alter plant growth, biomass partitioning, boll distribution, and yield potential [5].

Plant hormones such as auxin, gibberellins (GAs), brassinolide and cytokinins (CKs) play important roles in the process of plant type formation; specifically, these hormones play important roles in the process of plant dwarfing, stem-leaf angle determination, and lobulation, while ethylene (ET) and abscisic acid (ABA) exert many inhibitory effects [6, 7]. Plant height is determined by several developmental factors; specifically, stem elongation due to cell division and expansion (EXP) of both the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and the intermediate meristem play decisive roles. Stem elongation is controlled by several hormones, including GAs, brassinosteroids, auxin, and strigolactones (SLs) [8]. Relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms controlling the growth of intercalary meristems, but this process is triggered by ET and promoted by GA [9]. In the case of deepwater rice, GA induces internode growth by promoting both cell division and cell elongation [10]. Oscen1 and Oscen2, which are members of the TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1)/CENTRORADIALIS (CEN) gene family in rice, exhibit distinct expression patterns mainly in secondary meristems. Overexpression of Oscen1 and Oscen2 in transgenic rice plants results in increased numbers of shorter internodes, suggesting that these genes regulate the development of basic structures by stimulating the activities of secondary meristems in the uppermost phytomers [11]. The downregulation of GA biosynthesis-related genes in cotton inhibits cell elongation, reduces plant height and shortens internode lengths, which indicates that GA has an important effect on internode elongation of the main stem in cotton plants [1].

In terms of shoot architecture, the SAM determines plant phyllotaxy and impacts axillary meristem (AM) formation. During leaf development, an AM can develop in the axil and subsequently give rise to a secondary shoot. Lateral shoot outgrowth is fundamentally important for controlling shoot architecture [8]. By locating and cloning the GbAF gene (which controls the axillary flowering phenotype) of Gossypium barbadense L. and the GhCB gene (which controls the clustered boll phenotype) of Gossypium hirsutum L., researchers observed that different phenotypes were caused by mutations at different SNP loci at the same locus, which is homologous with SELF-PRUNING (SP) in tomato; moreover, silencing GoSP in Gossypium barbadense L. and Gossypium hirsutum L. transformed the plant architecture such that plant growth was limited [12]. The above mentioned studies focused mainly on the elongation of the internode of both the main stem and zero-type fruiting branches. No studies have investigated the physiological and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that govern the internode elongation of indefinite fruiting branches of cotton.

In this study, two cotton plant varieties whose fruiting branch lengths significantly differ but whose heights do not significantly differ were used to identify and analyze the genes and related metabolic pathways involved in internode elongation via RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) techniques. The endogenous hormone contents and analysis of both transcription factors (TFs) and related genes revealed the molecular mechanism of internode elongation of cotton fruiting branches. Together, the results provide a valuable resource for further identification of genes related to internode elongation of cotton branches.

Results

Differences in the internode lengths of fruiting branches between genotypes

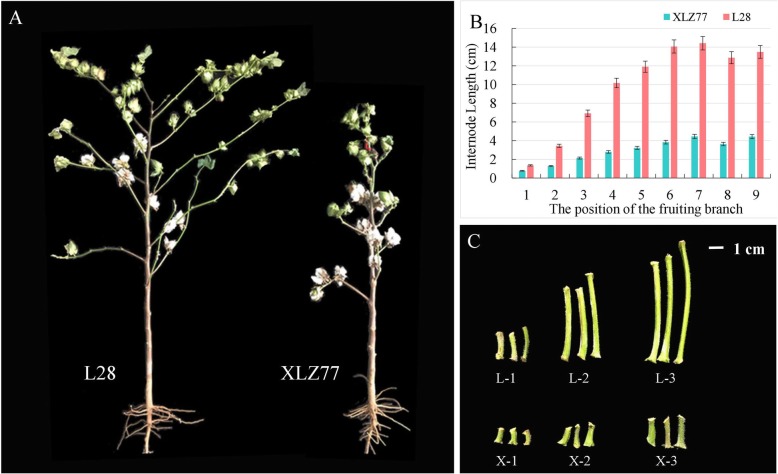

The differences in plant architecture were very significant between the two varieties (Fig. 1a). The L28 variety had longer fruiting branch internodes and loose plant architecture; the XLZ77 variety had shorter fruiting branch internodes and compact plant architecture. However, there was no significant difference in plant height between the two varieties. We measured the length of the first internode of each branch of both varieties (Fig. 1b); the internode of L28 gradually elongated until reaching the sixth branch, after which the length essentially stabilized at approximately 14 cm. On the other hand, the internode length of XLZ77 was stabilized at approximately 3 cm at the fourth branch. To explain the differences in internode lengths of the fruiting branches, we selected the first internode of the first, second and third branches from the top for transcriptome sequencing (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic difference between XLZ77 and L28. a. Whole-plant phenotypic differences between XLZ77 and L28. b. The first internode length of the fruiting branch of the two genotypes; the position of the fruiting branch is counted from the top of the plant. c. Sample differences between XLZ77 and L28. L, L28. X, XLZ77. The numbers represent the position of the fruiting branch

RNA-Seq analysis and gene annotation

Approximately 1.05 × 109 raw reads of 150 bp paired-end reads were generated from the eighteen samples via RNA-Seq. After 0.42% adaptor deletion, 1.30% low-quality read filtering and 0.001% N-containing read filtering, > 98.27% of the sequences were confirmed as clean reads. Detailed information about the obtained reads is listed in Additional file 1. By anchoring the clean reads to the cotton reference genome, we obtained the expression data of 76,331 genes among the 18 samples (Additional file 2). The BLAST algorithm was then used to identify Arabidopsis thaliana transcripts to determine the functional annotations in cotton.

Screening and identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

To identify DEGs between the two genotypes, the edgeR package (http://www.rproject.org/) was used. We identified genes fold change (FC) was ≥2 and whose false discovery rate (FDR) was < 0.05 in a comparison as significantly differentially expressed. The number of DEGs between each pair of compared groups is shown in Additional file 3. When the different internodes of the same variety were compared, the numbers of upregulated and downregulated DEGs in L-1 vs L-2 and in L-1 vs L-3 were nearly identical. The fewest DEGs occurred in the X-1 vs X-2 comparison, but in the X-1 vs X-3 comparison, the number of upregulated DEGs in X-1 was 1.8 times as high as that of downregulated DEGs. However, when the same internodes of the different varieties were compared, the number of upregulated DEGs in X-1 was 3.5 times as high as that of the downregulated DEGs in the X-1 vs L-1 comparison. In the X-2 vs L-2 comparison, the number of upregulated DEGs in X-1 was 3.1 times as high as that of the downregulated DEGs.

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis showed that plant hormones played important roles in internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton

To understand the DEGs functions, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed in accordance with a p-value of 0.05 adjusted by the FDR as the cutoff. The analysis results are shown in Additional file 4. Plant hormone signal transduction pathways were significantly enriched in the X-1 vs L-1, X-3 vs L-3, L-1 vs L-2 and L-1 vs L-3 comparisons, which suggests that plant hormone signal transduction pathways may play important roles in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton.

To identify the contributions of hormone-mediated transcriptional regulation to the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton, we mapped the DEG transcripts to eight hormone-related pathways in the Arabidopsis Hormone Database; 1009 genes associated with various aspects of hormone homeostasis were enriched (Additional file 5). The genes whose expression significantly differed the most were related to auxin, ET, CK and jasmonic acid (JA).

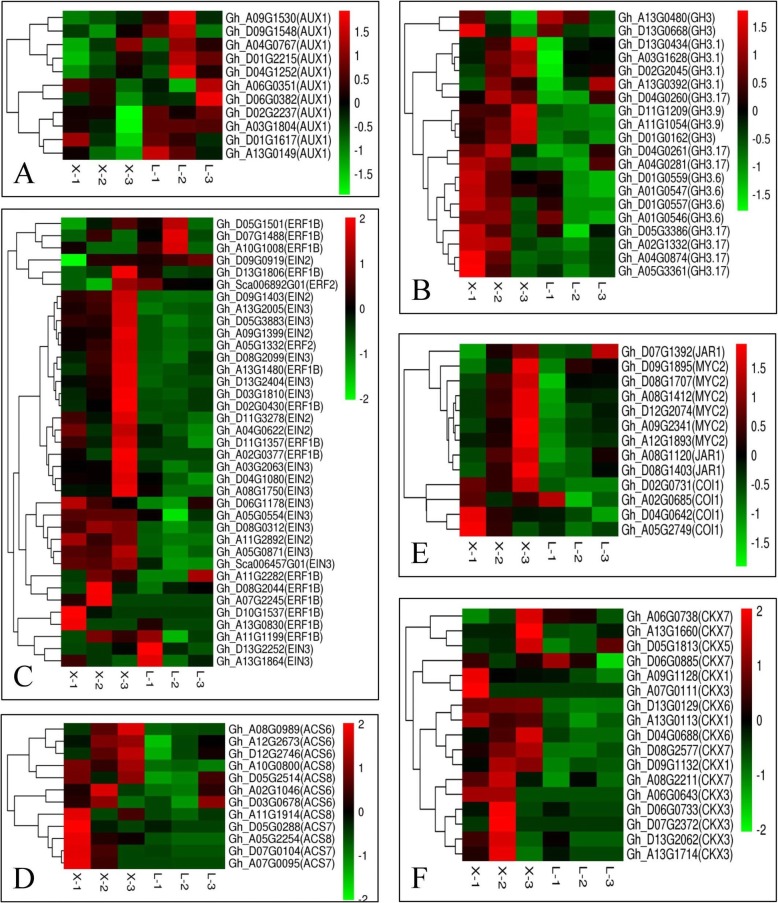

Auxin influx carrier (AUX1) is a high-affinity indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) importer. In the present study, a total of 18 AUX1-related genes were differentially expressed in the two varieties. Eleven of these genes were highly expressed in L28 (Fig. 2a). GH3 is a negative regulator of auxin signal transduction. A total of 49 DEGs between both varieties were annotated as GH3, 20 of which were highly expressed in XLZ77 (Fig. 2b); we excluded 29 genes with FPKM < 1.

Fig. 2.

Cluster heat map of plant hormone-related genes. a. AUX1; b. GH3; c. EIN2/3 and ERF1/2; d. ACS; e. JAR1, MYC2, COI1; f. CKX. The expression of all the genes listed in these maps is shown in Additional file 6

In the ET signal transduction pathway, a total of 7 DEGs between the varieties were annotated as ethylene-insensitive protein (EIN2), 20 DEGs were annotated as EIN3 and 35 DEGs were annotated as ethylene response factor (ERF)1/2. All of the EIN2-related and 14 of the EIN3-related DEGs were highly expressed in XLZ77, while most of the ERF1/2-related genes were also highly expressed in XLZ77 (Fig. 2c). In addition, ACC synthase (ACS) is the most important enzyme in the ET synthesis pathway. There were 26 DEGs related to ACS between the two varieties, excluding unexpressed genes, 12 of which were highly expressed in XLZ77 (Fig. 2d). All of the above results indicate that the genes involved in ET synthesis and signal transduction were highly expressed in XLZ77.

Jasmonate synthetase (JAR1), insensitive mutant of coronatine, jasmonate SCF-COI1 receptor complex (COI1) and MYC2 are all positive regulators of the JA signal transduction pathway. In our results, a total of 8 DEGs between the varieties were annotated as JAR1, 10 DEGs were annotated as COI1 and 13 DEGs were annotated as MYC2. The majority of these genes were highly expressed in XLZ77 (Fig. 2e), and we excluded the genes with FPKM < 1 and newly annotated genes.

Degradation of the GK plant hormones is catalyzed by the cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX) enzymes. In the present study, 27 DEGs related to CKX were significantly enriched between the two varieties, the majority of which were highly expressed in XLZ77 (Fig. 2f).

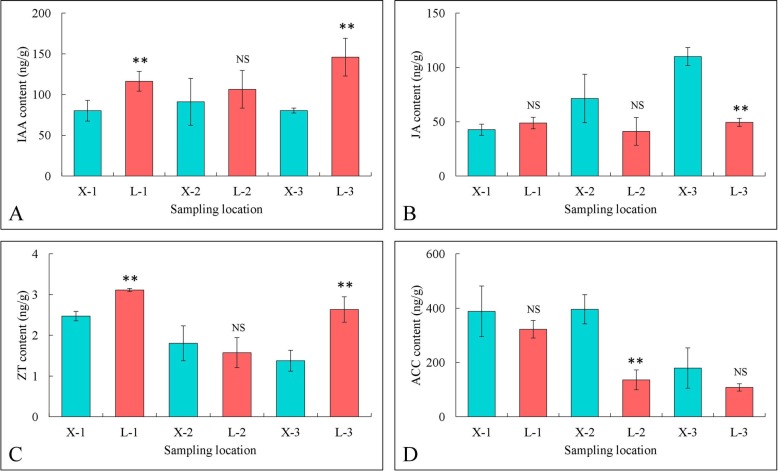

Endogenous hormone contents in the two genotypes.

To compare the roles of endogenous hormones in internode elongation between different internodes of cotton fruiting branches, the contents of IAA, zeatin (ZT) and JA were measured. Independent samples collected from the first internodes of the first, second and third branches from the top were used for endogenous hormone measurements. As shown in Fig. 3, the content of IAA between the two varieties significantly differed at the inverted 1 and 3 internodes. The content of JA in the inverted 3 internode of XLZ77 was significantly higher than that in L28 and reached 107.75 ng/g. Furthermore, compared with that in XLZ77, ZT content in L28 increased by 0.64 ng/g and 1.26 ng/g in inverted 1 and 3 internodes, respectively; these differences were significant. In addition, we measured the content of the ET precursor ACC, which was higher in all three internodes of XLZ77 relative to L28, and the difference was significant at the inverted 2 internode.

Fig. 3.

Endogenous hormone contents in XLZ77 and L28. a. IAA; b. JA; c. ZT; d. ACC. The data were analyzed by three independent repeats, and standard deviations are shown with error bars. The internodes in the same position act as a comparison group. Significant differences are indicated by “*”, “NS” represents no significant difference

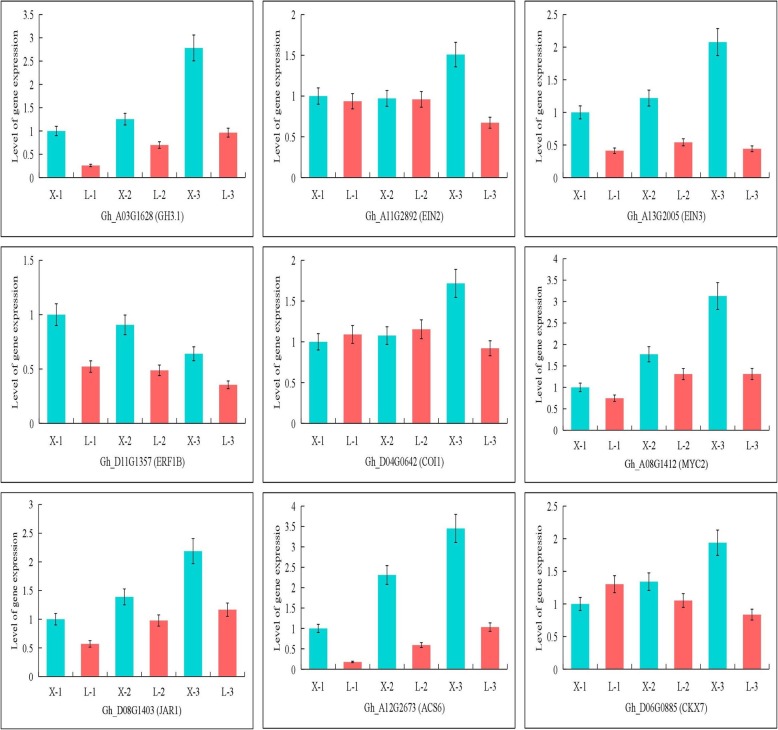

Validation of genes related to plant hormone signal transduction by qRT-PCR

To further verify the correctness of the RNA-Seq analysis results, twelve genes whose expression was relatively high were selected for real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). The qRT-PCR results for these genes were highly consistent with the RNA-Seq data (Fig. 4). With the exception of AUX1, all other genes were highly expressed in the short-internode variety XLZ77. Here, we show only nine pictures, and the other three pictures are shown in Additional file 7. The validation experiments support the accuracy of the relative values provided by the RNA-Seq analysis.

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR validation of genes related to plant hormone signal transduction. Expression levels of 12 plant hormone signal transduction-related genes in the two varieties were validated by qRT-PCR. All data are based on the analysis of three independent biological repeats

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of DEGs

GO category enrichment analysis was performed using the DEGs identified from each comparison. Here, our analysis includes only the majority of the GO terms associated with biological processes (Additional file 8).

With respect to the X-1 vs L-1 comparison group, DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of nucleosome assembly, chromatin assembly and nucleosome organization. With respect to the X-2 vs L-2 comparison group, DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of nucleosome assembly, phospholipid metabolic process and membrane lipid metabolic process. In the X-3 vs L-3 comparison group, DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of mitotic cell cycle process, cell cycle, cell division, the secondary metabolic process and cell wall organization. With respect to the L-1 vs L-2 comparison group, the DEGs were significantly enriched in the xyloglucan metabolic process, cell wall organization, cell wall organization or biogenesis and cell wall polysaccharide metabolic process GO categories. With respect to the L-1 vs L-3 comparison group, DEGs were also significantly enriched in the GO categories of cell wall organization or biogenesis, xylan biosynthetic process, xylan metabolic process and plant-type cell wall loosening. With respect to the X-1 vs X-2 comparison group, DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of plant-type cell wall organization or biogenesis, xyloglucan metabolic process, cell wall modification and plant-type cell wall loosening. In addition, the majority of genes related to these GO categories were highly expressed in X-2. However, with respect to the X-1 vs X-3 comparison group, DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of cell cycle, regulation of cell cycle, cell division, cell wall biogenesis and secondary metabolic process.

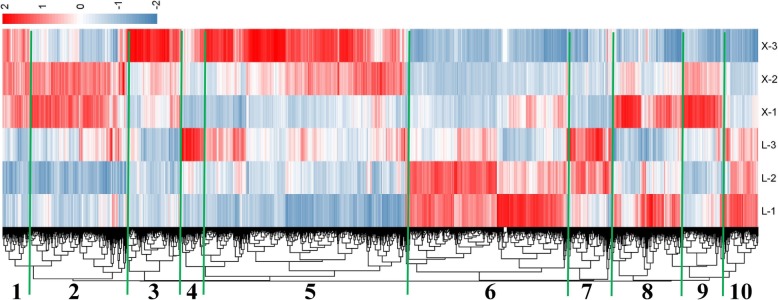

Cluster analysis of DEGs and GO category enrichment analysis of each module

In accordance with the condition of FPKM ≥10 for at least one sample, we screened 7330 DEGs in the comparison groups X-1 vs L-1, X-2 vs L-2, X-3 vs L-3, etc., for cluster analysis (Fig. 5). Based on the differences in the expression trends shown in the cluster heat map, the 7330 DEGs were divided into 10 modules, each with a unique expression trend. GO category enrichment analysis was performed on the DEGs in each module. According to the enrichment analysis and gene annotation results, we identified important GO terms for each module. The number of genes in each module and information for selected important GO terms are shown in Table 1, and the expression of the genes in each module is shown in Additional file 9. Here, we analyzed only the majority of GO terms based on biological processes (Additional file 10).

Fig. 5.

Cluster analysis of 7330 DEGs. According to the gene expression trends, the cluster heat map was divided into 10 modules to further explore the biological significance of each module. The number in the figure represents the name of each module

Table 1.

Number of genes in each module and related GO term information

| Module Name | Number of Genes | Related GO ID | Description | Number of GO Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module1 | 263 | GO:0006629 | lipid metabolic process | 23 |

| Module2 | 987 | GO:0043624 | cellular protein complex disassembly | 14 |

| GO:0006665 | sphingolipid metabolic process | 8 | ||

| Module3 | 502 | GO:0009809 | lignin biosynthetic process | 14 |

| Module4 | 175 | GO:0046271 | phenylpropanoid catabolic process | 13 |

| Module5 | 2003 | GO:0009873 | ethylene-activated signaling pathway | 76 |

| Module6 | 1533 | GO:0006334 | nucleosome assembly | 28 |

| Module7 | 454 | GO:0071555 | cell wall organization | 51 |

| Module8 | 633 | – | – | – |

| Module9 | 440 | – | – | – |

| Module10 | 340 | GO:0010410 | hemicellulose metabolic process | 10 |

With respect to module 1, the expression of genes was higher in XLZ77 than in L28. The DEGs were significantly enriched in the lipid metabolic process GO category. The genes Gh_A03G0871 and Gh_D02G1254 were mapped to AT1G14290, which encodes sphingoid base hydroxylase 2 (SBH2) and is involved in sphingolipid trihydroxy long-chain base (4-hydroxysphinganine) biosynthesis.

With respect to module 2, the gene expression in X-2 and X-3 was higher in XLZ77 than in L28. DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO categories of cellular protein complex disassembly, protein complex disassembly, cell wall biogenesis and sphingolipid metabolic process. The gene Gh_D09G0602 was significantly enriched in the above GO categories, was expressed more than the other genes, it was mapped to AT3G16630, which encodes KINESIN-13A. There are two important genes in the metabolic process of sphingolipids category: Gh_D02G1253 and Gh_A11G3137. The gene Gh_D02G1253 was mapped to AT1G14290, which encodes the sphingosine hydroxylase SBH2. The gene Gh_A11G3137 was mapped to AT5G10480, which encodes the protein tyrosine phosphatase PAS2.

With respect to module 3, gene expression was highest in X-3. The first GO category enriched was the lignin biosynthetic pathway, which included 14 genes: Gh_D11G2151 and Gh_D12G0788 were mapped to AT2G22420, which encodes a peroxidase superfamily protein (POX); Gh_D10G2466 and XLOC_076267 were mapped to AT2G38080, which encodes a laccase/diphenol oxidase family protein (LAC4); Gh_A10G1518 and Gh_D10G1769 were mapped to chitinase-like protein 2 (CTL2); Gh_A04G1032 was mapped to AT4G34050, which encodes an S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase superfamily protein (CCOAOMT1); Gh_A05G1579 was mapped to AT4G39330, which encodes cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 9 (CAD); and Gh_A11G1648, Gh_D11G1805 and Gh_Sca004990G01 were mapped to AT4G36220, which encodes ferulic acid 5-hydroxylase 1 (F5H). All of the above proteins (enzymes) are important in the biosynthesis of lignin.

Regarding module 4, the expression of genes was highest in L-3. The first GO category enriched was phenylpropanoid catabolic process, which contrasts with the GO category results obtained for module 3. A total of 13 genes were enriched in this module, and all of these genes were related to LAC: LAC2, LAC4, LAC5 and LAC17. The results showed that lignin was degraded more in L28 than in XLZ77; but decomposed and was metabolized to a lesser degree in the latter. This finding explains the differences in internode length.

With respect to module 5, the majority of genes were highly expressed in X-3. The DEGs were significantly enriched in the ET-activated signaling pathway GO category. A total of 76 genes were enriched in this module; most of these genes were related to ERFs. In addition, 8 genes in the pathway were mapped to AT3G51550, which encodes a FERONIA protein, a member of a family of receptor-like protein kinases.

Regarding module 6, gene expression in the three internodes was higher in L28 than in XLZ77. Moreover, the expression of these genes decreased as the internodes of fruiting branches elongated for the same variety. The DEGs were significantly enriched in the nucleosome assembly GO category. A total of 28 genes were enriched in this module; 19 of these genes were mapped to AT5G65360, which encodes a histone superfamily protein. In addition, most of the GO categories in module 6 were related to nucleosome assembly, chromatin assembly, DNA replication, mitosis, etc. It can be inferred that the genes were mainly enriched in the pathway of cell division.

With respect to module 7, the gene expression of the three internodes was higher in L28 than in XLZ77. In addition, the expression of these genes increased in L28 as the internodes of the fruiting branches elongated. The first GO category enriched was cell wall organization, which included 51 genes, 9 of which were mapped to EXP-related genes encoding expansins. In our samples, 107 EXP-related genes were screened from among all DEGs, and the expression of the majority of these genes was higher in L28 than in XLZ77. In addition, three genes were mapped to the AT1G75500 gene, which encodes the WALLS ARE THIN 1 (WAT1) gene.

With respect to module 10, gene expression in the three internodes was higher in L28 than in XLZ77. The expression of most of these genes was relatively high in L-1. DEGs were significantly enriched in the hemicellulose metabolic process GO category. A total of 10 genes were enriched in this category; 8 of the genes were mapped to xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH)-related genes. Three genes mapped to AT4G03210, which encodes XTH9. It can be inferred that the high expression of XTH genes in L28 leads to cell expansion and elongation.

Important genes and their predicted functions in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton are shown in Table 2. These genes could be used to genetically improve internode length in cotton.

Table 2.

Important genes and their predicted functions in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton

| Gene ID | L-1_fpkm | L-2_fpkm | L-3_fpkm | X-1_fpkm | X-2_fpkm | X-3_fpkm | Description | Predicted Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gh_A03G0871 | 140.59 | 123.31 | 174.71 | 288.19 | 307.84 | 312.05 | Sphingoid base hydroxylase 2 | Inhibition of growth, Promote apoptosis | Chen M et al., 2008 [13] |

| Gh_D02G1254 | 51.05 | 42.47 | 73.17 | 193.67 | 193.92 | 168.60 | Sphingoid base hydroxylase 2 | Inhibition of growth, Promote apoptosis | Chen M et al., 2008 [13] |

| Gh_D02G1253 | 26.06 | 4.56 | 3.80 | 64.51 | 24.95 | 22.93 | Sphingoid base hydroxylase 2 | Inhibition of growth, Promote apoptosis | Chen M et al., 2008 [13] |

| Gh_D09G0602 | 56.28 | 47.55 | 51.27 | 109.19 | 97.56 | 71.71 | Kinase-13A | Inhibition of cell expansion | Fujikura U et al., 2014 [14] |

| Gh_D09G0602 | 56.28 | 47.55 | 51.27 | 109.19 | 97.56 | 71.71 | Kinase-13A | Inhibition of cell cell size | Li YJ et al., 2017 [15] |

| Gh_A11G3137 | 4.98 | 2.37 | 7.81 | 10.01 | 10.12 | 3.79 | Protein-tyrosine phosphatase-like, PTPLA | Inhibition of cell division | Bach L et al., 2008 [16] |

| Gh_A05G1579 | 23.01 | 28.32 | 29.73 | 24.85 | 28.62 | 57.19 | Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 9 | Lignin accumulation | Mansell RL et al., 2014 [17] |

| Gh_A10G1518 | 14.25 | 16.39 | 79.99 | 12.18 | 20.41 | 209.74 | Chitinase-like protein 2 | Accelerate secondary metabolism | Hossain MA et al., 2010 [18] |

| Gh_D10G1769 | 11.60 | 13.33 | 67.11 | 7.79 | 14.97 | 144.79 | Chitinase-like protein 2 | Accelerate secondary metabolism | Hossain MA et al., 2010 [18] |

| Gh_A11G2936 | 14.46 | 20.28 | 55.22 | 7.95 | 9.54 | 40.63 | Laccase/diphenol oxidase family protein | Promotion of lignin decomposition | Berthet S et al., 2011 [19] |

| Gh_D03G1128 | 19.76 | 29.29 | 52.91 | 20.38 | 28.83 | 47.27 | Laccase/diphenol oxidase family protein | Promotion of lignin decomposition | Zhao Q et al., 2013 [20] |

| Gh_D09G2057 | 21.45 | 62.35 | 73.01 | 33.54 | 70.74 | 107.94 | Malectin/receptor-like protein Kinase family protein | Protoplast alkalization | Barbez E et al., 2017 [21] |

| Gh_D10G0981 | 237.30 | 215.92 | 111.36 | 116.78 | 90.66 | 36.42 | Histone superfamily protein | Promoting cell division | Günesdogan U et al., 2014 [22] |

| Gh_A08G2114 | 202.08 | 170.28 | 81.50 | 94.56 | 62.85 | 30.06 | Histone superfamily protein | Promoting cell proliferation | Günesdogan U et al., 2014 [22] |

| Gh_A13G0050 | 127.76 | 214.03 | 257.34 | 121.15 | 156.57 | 118.64 | Expansin A8 | Promote cell loosening and expansion | Nardi CF et al., 2014 [23] |

| Gh_D13G0060 | 196.61 | 288.97 | 352.52 | 199.21 | 232.59 | 172.40 | Expansin A8 | Promote cell loosening and expansion | Nardi CF et al., 2014 [23] |

| Gh_D01G0964 | 47.14 | 51.81 | 75.14 | 36.00 | 37.19 | 32.03 | Walls Are Thin 1 | Promoting cell elongation | Ranocha P et al., 2010 [24] |

| Gh_A01G0922 | 36.58 | 39.66 | 58.01 | 24.81 | 25.32 | 28.10 | Walls Are Thin 1 | Promoting cell elongation | Ranocha P et al., 2010 [24] |

| Gh_A03G1432 | 102.22 | 86.74 | 92.84 | 53.86 | 58.35 | 44.55 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 9 | Promoting cell proliferation and elongation | Shin YK et al., 2006 [25] |

| Gh_A13G0500 | 39.81 | 26.30 | 26.26 | 13.99 | 14.66 | 12.00 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 9 | Promoting cell proliferation and elongation | Shin YK et al., 2006 [25] |

Cluster analyses of differentially expressed TFs

TFs are key regulatory proteins that are essential for the regulation of gene expression. There were significant differences in the expression of 2067 TFs between the two varieties (Additional file 11). The WRKY, ERF and bHLH families were the top three largest families of TFs. As shown in Table 3, 224 genes in the WRKY family, 256 genes in the bHLH family and 399 genes in the ERF family were enriched between the two varieties; most of them were upregulated in XLZ77. The high expression of these TF families in XLZ77 could be the main reason for the shorter internodes of the fruiting branches.

Table 3.

Number of TFs

| TF | Number | Upregulated | Downregulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| bHLH | 256 | 158 | 98 |

| WRKY | 224 | 176 | 48 |

| ERF | 399 | 230 | 169 |

Discussion

Regulation of plant hormone involved in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton

Higher plants develop their plant architecture by regulating the activity of the apical meristem and side meristem. The activity of the meristems is regulated by environmental signals, developmental stages and genetic factors. The comprehensive regulation of these factors confers developmental plasticity to plants and their adaptability to the environment. Plant hormones are at the center of a network system that governs many regulatory signals. These hormones play an important role in plant architecture formation [26]. Specifically, the phytohormones auxin and CK can promote cell expansion and division, whereas ET and JA inhibit organ growth by affecting cell expansion [27].

The plant hormone IAA controls growth and developmental responses throughout the life of a plant; specifically, IAA is involved in cell expansion and division, tissue differentiation, organ development and a variety of physiological responses [28]. The content and distribution of auxin play important roles in plant morphogenesis [29]. Auxin is a weak acid that protonates in a low-pH environment outside the cell and enters the cell by infiltration or mediation by an input vector. After auxin enters a cell, the increased pH of the cytoplasm causes the auxin to remain in the cell in an ionic state, whereas auxin is transported out of the cell depending on specific output carrier. The AUX1 gene encodes a component of the auxin influx carrier, and mutations within AUX1 selectively impair the action of auxins that require carrier-mediated uptake [30]. The accumulation of auxin in the root apex clearly decreases when AUX1 is mutated [31]. The Gretchen Hagen-3 (GH3) gene family encodes a class of luciferase [32] that can catalyze the formation of an inactive form of auxin by binding IAA and amino acid molecules in vitro [33]; this luciferase is a negative regulator of auxin signal transduction. Overexpression of GH3.2, GH3.5 or GH3.6 can result in plant dwarfism, inhibition of hypocotyl elongation of seedlings, reduction in lateral roots, loss of apical dominance and endogenous auxin deficiency [34]. Our RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR results indicate that the expression levels of the key genes related to IAA signal transduction, including AUX1, were significantly upregulated in L28, and the expression levels of the GH3 family protein genes were significantly upregulated in XLZ77. These findings indicate that auxin signal transduction is positively regulated in L28 but negatively regulated in XLZ77. Furthermore, IAA content is higher in L28 than in XLZ77. Together, these results show that auxin promotes the elongation of fruiting branches in cotton. Therefore, we predicted that IAA, when maintained at a certain level and experiencing upregulated signaling, may be a hormone trigger of internode elongation.

The phytohormone ET plays roles in various physiological processes throughout the life cycle of a plant [35]. Ethephon has highly significant effects on plant height [36], ear height [37, 38] and internode length [39]. Reduced plant height might be due to decreased internode length in response to the application of ethephon [40]. Moreover, elevated tissue ET concentrations inhibit longitudinal cell extension and thus stem growth [41, 42]. ET inhibits the elongation of maize internodes by inhibiting the longitudinal elongation of cells [43]. ET signal transduction supposedly follows a “linear” pathway, with membrane-bound receptors at the beginning, multiple positive and negative regulators in between, and TFs at the end of the chain [44]. EIN2 is a positive regulator of the pathway, which plays a major role in the ET response [45]. Members of the EIN3 family are involved in a regulatory cascade and stimulate the transcription of other TFs such as ERF1 [46], which is a member of the ERF family of TFs [47]. These TFs have been shown to act as activators or repressors of additional downstream ET-responsive genes [48]. Our RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR results indicate that the genes related to EIN2, EIN3 and ERF1/2 were significantly highly expressed in XLZ77. This finding indicates that ET signal transduction is positively regulated in XLZ77. In addition, the content of ACC (the precursor of ET) in XLZ77 is higher than that in L28. Together, these data suggest that ET may act as a negative regulator of the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton.

The phytohormone JA plays essential roles in plant growth and development [49]. Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) inhibits root growth in some plant species. High concentrations of JA (25 μmol/L) can also inhibit plant growth [50]. JA inhibits the expression of cell cycle-related proteins and thus inhibits cell division [51]. JA inhibits the growth of the main roots of Arabidopsis thaliana by inhibiting cell division activity of the root meristem [52]. Our RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR results showed that positively regulated factors of JA signal transduction, including JAR1, COI1 and MYC2, were significantly upregulated in XLZ77. This indicates that JA signal transduction is positively regulated in XLZ77 but negatively regulated in L28. Furthermore, the JA content in XLZ77 was higher than that in L28. Together, these results indicate that JA can inhibit the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton.

CKs affect many processes in plants, the most important of which are probably cell division and proliferation in the SAM, which are responsible for the production of all aboveground organs [53, 54]. Within the context of plant development, the CK phytohormone play key regulatory roles in the meristems (stem cell centers) and generally positively regulate the SAM by stimulating cell division [55]. CK oxidative decomposition catalyzed by CKX is an important mechanism for regulating the dynamic balance of CK content [56]. Our RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR results indicate that the expression of CKX-related genes (CK inactivating genes) was higher in XLZ77 than in L28. Because of the low level of CKs, the cell division process was suppressed in XLZ77. Furthermore, the content of ZT was higher in L28 than in XLZ77. Taken together, these data suggested that CK may act as a positive regulator in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton.

In summary, we propose a hypothetical model to explain the role of phytohormones in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton (Fig. 6). In XLZ77, upregulated ET and JA can inhibited the elongation and division of cells, resulting in fewer cells and a slow increase in size, thus leading to a relatively short internode length of the fruiting branches. However, the content and signal transduction of both auxin and CK were downregulated, which resulted in slowed cell elongation, expansion and cell division; thus, the number and volume of cells increased slowly, eventually inhibiting the internode elongation of the cotton fruiting branches.

Fig. 6.

Suggested model for plant hormone-mediated regulation of internode elongation in cotton

Regulatory role of TFs in the internode elongation of cotton fruiting branches

TFs are regulatory proteins that can activate or repress the transcription of multiple target genes in living organisms, and TF-mediated gene expression regulatory networks play important roles in plant growth and development. Plant growth and development can be regulated by regulating a series of TFs. In the present study, 2067 TFs were significantly enriched among all genes between the two genotypes. Among the various TFs, the TFs WRKY, ERF and bHLH constituted the top three largest families who members were active between these two genotypes. In addition, most of the TFs were significantly upregulated in XLZ77.

WRKY proteins compose a large superfamily of transcriptional regulators that are involved primarily in various plant physiological programs. Members of the WRKY TF family play an indispensable role in plant root, stem and leaf formation and development. OsWRKY78 can regulate both stem elongation and seed development [57]. Similarly, AtWRKY71 regulates branching development in Arabidopsis thaliana [58]. GhWRKY15 not only contributes to the alteration of defense resistance to both viral and fungal infections but also affects plant growth and development, especially stem elongation [59]. Our results showed that most of the 224 WRKY-related genes were upregulated in XLZ77. These findings indicate that WRKY TFs may play negative regulatory roles in the internode elongation of cotton branches.

The typical biological effect of ET is the inhibition of both the elongation and growth of stems and roots and the promotion of stem and root lateral growth. The ERF family of TFs, which is present only in the plant kingdom, is characterized by the presence of a highly conserved DNA-binding domain [60] that can positively regulate the signal transduction pathway of ET. Moreover, some rice ERFs have been reported to plays roles in regulating internode elongation [61]. Another ERF gene, SUB1A, restricts plant elongation at the seedling stage during flash floods [62]. The rice AP2/ERF protein OsEATB restricts internode elongation by downregulating a GA biosynthesis gene [63]. Our data showed that 399 genes related to ERF TFs were enriched, and approximately 2/3 of these genes were highly expressed in XLZ77. Thus, ERF TFs may play a negative role in the internode elongation of fruiting branches in cotton.

bHLH TFs compose a large family within the plant genome. These TFs play important roles in plant growth and development, nutrient absorption, biosynthesis, signal transduction, etc. [64]. ILI1 and PRE1 interact with the bHLH protein IBH1 (ILI1 binding bHLH), whose overexpression causes erect leaves in rice and dwarfism in Arabidopsis [65]. The LAX (OsHLH164) gene is expressed at the boundary between the SAM and the region of new meristem formation; LAX genes have been identified as the main regulators of axillary meristem formation in rice [66]. Our results showed that 256 genes related to bHLH TFs were significantly enriched, and approximately 3/4 of these genes were highly expressed in XLZ77. These findings indicate that bHLH TFs may play a negative regulatory role in fruiting branch internode elongation in cotton.

In summary, we can assume that the WRKY, bHLH and ERF TFs mainly inhibit the internode elongation of cotton fruiting branches. The upregulation of these TFs in XLZ77 may be the primary reason for the relatively short internodes in that variety. The differences in endogenous hormone content may be caused by mutations in TFs. In the future, we will attempt to locate these mutation sites by map-based cloning to further explore the mechanism of internode elongation.

Conclusions

In this study, we selected the fruiting branch internodes at three different stages from two cotton cultivars whose fruiting branch internode lengths significantly differed. A total of 76,331 genes were detected by transcriptome sequencing. The potential roles of a series of DEGs involved in the internode elongation of cotton were identified and analyzed by GO category and KEGG pathway analyses, qRT-PCR verification and hormone content determination. We found that auxin and CK are the positive regulators of internode elongation in cotton branches. In contrast, ET and JA may act as negative regulators of internode elongation in cotton branches. Furthermore, the WRKY, ERF and bHLH TFs were identified as important inhibitors of the elongation of internodes in cotton. In XLZ77 (a short-internode variety), the mass synthesis of ET and the amino acid conjugation of auxin led to the inhibition of plant cell elongation, while the increase in JA content and the degradation of CKs led to a slow rate of cell division, which eventually resulted in a phenotype that included relatively short internodes of fruiting branches. The results of this study not only provide gene resources for the genetic improvement of cotton plant architecture but also lay a foundation for improved understanding of the molecular mechanism of the internode elongation of cotton branches.

Methods

Plant material and sampling

In our study, two cotton genotypes—a short-internode cultivar (Xinluzhong77, XLZ77) and a long-internode cultivar (Lumianyan28, L28) —were used. The two genotypes were planted at the experimental station of the Institute of Cotton Research of the CAAS in Anyang City (Henan Province, China) on April 20, 2017, after which the plants were subjected to routine field management. The first internodes of the first, second and third branches from the top of the plants were collected at the cotton bud stage (July 6, 2017). A schematic diagram of the cotton sampling positions is shown in Additional file 12. Three biological replicates were included; the samples of each biological replicate were pooled from 10 plants, which were randomly selected to avoid any potential effects of position in the field. The three biological replicates were mixed together and then divided into two groups; one group was used for RNA isolation via Illumina sequencing and qRT-PCR analysis, and the other was used for endogenous hormone measurements. The samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C until use.

RNA isolation, library construction and RNA-Seq

Total RNA was extracted using a Plant RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity and quantity were verified by RNase-free agarose gel electrophoresis and with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Subsequent experiments were carried out with qualified RNA samples.

A sequencing library was constructed with a NEBNext1 Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, the total mRNA was isolated with oligo (dT) beads. All of the mRNA was cut into short fragments (200 nt) by adding a fragmentation buffer. First-strand cDNA was generated using random hexamer-primed reverse transcription. Second-strand cDNA was then synthesized by DNA polymerase I and RNase H. Afterward, the synthesized cDNA fragments were purified and then subjected to end pairing, the addition of a single “A” base, and ligation with Illumina adapters. The ligation products were subsequently size-fractioned by agarose gel electrophoresis, after which the fragments were excised for PCR amplification. The amplified fragments were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq™ 4000 by Gene Denovo Co. (Guangzhou, China).

Sequencing analysis and differential expression analysis

After sequencing, the reads with adapter sequences were removed. Reads with more than 10% N bases and low-quality (Q ≤ 20) reads with more than 50% bases were then removed from each data set to gain more reliable results. The alignment software TopHat2 (v2.1.1) was used to map the reads to the Gossypium hirsutum L. genome [67]. The number of mapped clean reads for each gene was then counted and normalized into reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) for calculating gene expression. When comparing two groups, edgeR was used to analyze DEGs to correct for multiple testing, and the FDR was calculated to adjust the threshold of the p-value. Genes with a minimum 2-fold difference in expression, |log2FC| ≥ 1 and FDR ≤ 0.05 were considered DEGs.

GO classification was performed via WEGO (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/cgi-bin/wego/index.pl), and the GO categorization results were expressed as 3 independent hierarchies for molecular function, biological process and cellular component. For each KEGG pathway, the numbers of DEGs were compared to the entire reference gene set by hypergeometric tests to determine the pathways enriched for differentially regulated genes. The p-values of the GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction, and a corrected p-value ≤0.05 was chosen as the threshold value for determining significantly enriched GO terms. With respect to KEGG enrichment analysis, pathways with an FDR value≤0.05 were considered enriched.

Real-time PCR validation

Twelve genes that exhibited different expression patterns as revealed by RNA-Seq were selected for validation by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from the same samples that were used for sequencing. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a Primer Script RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). The primer sequences used were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The specific primers for the selected genes and the internal control gene (UBQ) are listed in Additional file 13. qRT-PCR was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, StepOnePlus, USA) using BCS® Wiz Universal SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China). The cotton UBQ gene was used as an internal standard to calculate relative fold differences based on comparative cycle threshold (2-ΔΔCt) values [68]. Then, ddH2O was then used as a nontemplate control. The qRT-PCR procedure was as follows: 2 μL of a 1/8 dilution of cDNA in H2O was added to 10 μL of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix; 0.4 μL of each primer and 7.2 μL of H2O were then added, and the final volume was brought to 20 μL. The qPCR program was as follows: 50 °C for 2 min; 95 °C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s in 96-well optical reaction plates. Each real-time PCR was performed three times.

Measurements of various hormones

To analyze the endogenous hormone contents, independent samples from XLZ77 and L28 were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C for further determination. Each sample was prepared in triplicate. Endogenous IAA, ZT, JA and ACC contents were determined using an ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS/MS) system [69].

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between values were determined using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey test at a significance level of α = 0.01 in Excel software. All expression analyses were performed for three biological replicates. All reported values represent the arithmetic averages of three replicates, and the data are expressed as the mean plus or minus standard deviation (means ± SD).

Additional files

Detailed information on the obtained reads via RNA-Seq. (XLS 20 kb)

Expression of all genes in the 18 samples. (XLS 64722 kb)

Detailed information on the number of DEGs between each pair of compared groups. (JPG 275 kb)

List of KEGG pathways enriched in each comparison. (XLS 163 kb)

List of genes associated with various aspects of hormone homeostasis. (XLS 1631 kb)

List of genes related to hormone signal transduction in Fig. 2. (XLS 305 kb)

Additional figure showing the RT-PCR validation of three genes related to plant hormone signal transduction. (JPG 173 kb)

List of enriched GO categories in each comparison. (XLS 12995 kb)

List of the DEGs expressed in 10 modules. (XLS 9181 kb)

List of enriched GO categories in 10 modules. (XLS 2393 kb)

List of the expressed TF genes. (XLS 4511 kb)

Schematic diagram of the sampling position of cotton. (JPG 38 kb)

List of primers used for qRT-PCR. (DOC 44 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Gene Denovo Co. (Guangzhou, China) for assistance with sequencing and original data processing. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD0100406).

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- AUX1

auxin influx carrier

- bHLH

basic helix-loop-helix

- CAD

cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase

- CCOAOMT1

S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase superfamily protein

- CK

cytokinin

- CKX

cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase

- COI1

an insensitive mutant of coronatine, jasmonate SCF-COI1 receptor complex

- CTL2

chitinase-like protein 2

- CTR1

serine/threonine protein kinase

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- EIN2/3

ethylene-insensitive protein

- ERF

ethylene response factor

- ET

ethylene

- ETR

ethylene receptor

- EXP

expansion

- F5H

ferulic acid 5-hydroxylase

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GA

gibberellin

- GH3

gretchenhagen-3

- GO

Gene Ontology

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- JA

jasmonic acid

- JAR1

jasmonate synthetase

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LAC

laccase/diphenol oxidase family protein

- LOF

loss of function

- MAPKKK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase

- NCBI

National Center of Biotechnology Information

- RNA-Seq

RNA Sequencing

- RPKM

reads per kilobase per million reads

- SAM

shoot apical meristem

- SBH2

sphingoid base hydroxylase 2

- TF

transcription factor

- WAT1

the walls are thin1

- XTH

xyloglucan endotransglucosylase /hydrolase

- ZIM

ZIM domain protein

- ZT

zeatin

Author’ contributions

CP, YZ and XZ designed and oversaw the research. FJ and SL performed the research. FJ and CP analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. XZ and YZ provided helpful suggestions during the data analysis. SZ, JC and QS provided suggestions during the article writing. HM provided help with cotton field management. CG and XZ provided helpful suggestions during qRT-PCR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD0100406). Founding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Feiyan Ju and Shaodong Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Feiyan Ju, Email: jvfeiyan0610@163.com.

Shaodong Liu, Email: mrliusd@163.com.

Siping Zhang, Email: zhsp5337@163.com.

Huijuan Ma, Email: binghan1201@163.com.

Jing Chen, Email: chenjing123sky@163.com.

Changwei Ge, Email: Zhugechangwei@126.com.

Qian Shen, Email: shenqian429@126.com.

Xiaomeng Zhang, Email: 18738237057@163.com.

Xinhua Zhao, Email: zhaoxinhua1968@126.com.

Yongjiang Zhang, Email: yongjiangzh@sina.com.

Chaoyou Pang, Email: chypang@163.com.

References

- 1.Wang L, Mu C, Du M, Chen Y, Tian X, Zhang M, et al. The effect of mepiquat chloride on elongation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) internode is associated with low concentration of gibberellic acid. Plant Sci. 2014;225(8):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukino N, Ohara T, Sugiyama M, Kubo N, Hirai M, Sakata Y, et al. Mapping of a gene that confers short lateral branching (slb) in melon (Cucumis melo L.) Euphytica. 2012;187(1):133–143. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0667-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McSteen P, Leyser O. Shoot branching. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:353–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaggwa-Asiimwe R, Andrade-Sanchez P, Wang G. Plant architecture influences growth and yield response of upland cotton to population density. Field Crop Res. 2013;145(4):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marois JJ, Wright DL, Wiatrak PJ, Vargas MA. Effect of row width and nitrogen on cotton morphology and canopy microclimate. Crop Sci. 2004;44(3):870–877. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2004.8700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kir G, Ye H, Nelissen H, Neelakandan AK, Kusnandar AS, Luo A, et al. RNA interference knockdown of BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 in maize reveals novel functions for brassinosteroid signaling in controlling plant architecture. Plant Physiol. 2015;169(1):826. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leiboff S, Li X, Hu HC, Todt N, Yang J, Li X, et al. Genetic control of morphometric diversity in the maize shoot apical meristem. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8974. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B, Smith SM, Li J. Genetic regulation of shoot architecture. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69:437–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Knaap E, Kim JH, Kende H. A novel gibberellin-induced gene from rice and its potential regulatory role in stem growth. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(3):695–704. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayano M, Kani T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kitaoka T, Kuroha T, et al. Gibberellin biosynthesis and signal transduction is essential for internode elongation in Deepwater rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37(10):2313–2324. doi: 10.1111/pce.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Hu W, Wang L, Lin C, Cong B, Sun C, et al. TFL1/CEN-like genes control intercalary meristem activity and phase transition in rice. Plant Sci. 2005;168(6):1393–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Si Z, Liu H, Zhu J, Chen J, Wang Q, Fang L, et al. Mutation of SELF-PRUNING homologs in cotton promotes short-branching plant architecture. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(10):2543–2553. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen M, Markham JE, Dietrich CR, Jaworski JG, Cahoon EB. Sphingolipid long-chain base hydroxylation is important for growth and regulation of sphingolipid content and composition in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20(7):1862–1878. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujikura U, Elsaesser L, Breuninger H, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Ivakov A, Laux T, et al. Atkinesin-13A modulates cell-wall synthesis and cell expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana via the THESEUS1 pathway. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YJ, Zhu SH, Zhang XY, Liu YC, Xue F, Zhao LJ, et al. Expression and functional analyses of a Kinesin gene GhKIS13A1 from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber. BMC Biotechnol. 2017;17(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12896-017-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach L, Michaelson LV, Haslam R, Bellec Y, Gissot L, Marion J, et al. The very-long-chain hydroxy fatty acyl-CoA dehydratase PASTICCINO2 is essential and limiting for plant development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14727–14731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805089105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansell RL, Babbel GR, Zenk MH. Multiple forms and specificity of coniferyl alcohol from cambial e-hydrogenase regions of higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1976;15(12):1849–1853. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)88829-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hossain MA, Noh HN, Kim KI, Koh EJ, Wi SG, Bae HJ, et al. Mutation of the chitinase-like protein-encoding AtCTL2 gene enhances lignin accumulation in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167(8):650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berthet S, Demont-Caulet N, Pollet B, Bidzinski P, Cézard L, Le Bris P, et al. Disruption of LACCASE4 and 17 results in tissue-specific alterations to lignification of Arabidopsis thaliana stems. Plant Cell. 2011;23(3):1124–1137. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Q, Nakashima J, Chen F, Yin Y, Fu C, Yun J, et al. LACCASE is necessary and nonredundant with PEROXIDASE for lignin polymerization during vascular development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3976–3987. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbez E, Dünser K, Gaidora A, Lendl T, Busch W. Auxin steers root cell expansion via apoplastic pH regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(24):E4884–E4893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613499114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Günesdogan U, Jäckle H, Herzig A. Histone supply regulates S phase timing and cell cycle progression. eLife,3,(2014-08-11), 2014, 3(3):e02443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Nardi CF, Villarreal NM, Rossi FR, Martínez S, Martínez GA, Civello PM. Overexpression of the carbohydrate binding module of strawberry expansin2 in Arabidopsis thaliana modifies plant growth and cell wall metabolism. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;88(1–2):101–117. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranocha P, Denancé N, Vanholme R, Freydier A, Martinez Y, Hoffmann L, et al. Walls are thin 1 (WAT1), an Arabidopsis homolog of Medicago truncatula NODULIN21, is a tonoplast-localized protein required for secondary wall formation in fibers. Plant J. 2010;63(3):469–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin YK, Yum H, Kim ES, Cho H, Gothandam KM, Hyun J, et al. BcXTH1, a Brassica campestris homologue of Arabidopsis XTH9, is associated with cell expansion. Planta. 2006;224(1):32–41. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little CHA, Pharis RP. 13-hormonal control of radial and longitudinal growth in the tree stem. Plant Stems. 1995;4:281–319. doi: 10.1016/B978-012276460-8/50015-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolters H, Jürgens G. Survival of the flexible: hormonal growth control and adaptation in plant development. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(5):305–317. doi: 10.1038/nrg2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagen G. Auxin signal transduction. Essays in Biochemistry volume. 2015;58:1–12. doi: 10.1042/bse0580001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot. 2005;95(5):707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchant A, Kargul J, May ST, Muller P, Delbarre A, Perrot-Rechenmann C, et al. AUX1 regulates root gravitropism in Arabidopsis by facilitating auxin uptake within root apical tissues. EMBO J. 1999;18(8):2066–2073. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swarup R, Friml J, Marchant A, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Palme K, et al. Localization of the auxin permease AUX1 suggests two functionally distinct hormone transport pathways operate in the Arabidopsis root apex. Genes Dev. 2001;15(20):2648–2653. doi: 10.1101/gad.210501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding X, Cao Y, Huang L, Zhao J, Xu C, Li X, et al. Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid amido synthetase GH.8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell. 2008;20(1):228–240. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staswick PE, Serban B, Rowe M, Tiryaki I, Maldonado MT, Maldonado MC, et al. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell. 2005;17(2):616–627. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JE, Park JY, Kim YS, Staswick PE, Jeon J, Yun J, et al. GH3-mediated auxin homeostasis links growth regulation with stress adaptation response in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):10036–10046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattoo AK, Suttle JC, Eds. The plant hormone ethylene. Boca Raton, FA: CRC Press, Inc. 1991.

- 36.Cox WJ, Andrade HF. Growth yield and yield components of maize as influenced by ethephon. Crop Sci. 1988;28(3):536–542. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800030023x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasele IN, Nyirenda F, Shanahan JF, Nielsen DC, D’Andria R. Ethephon alters corn growth, water use, and grain yield under drought stress. Agron J. 1994;86(2):283–288. doi: 10.2134/agronj1994.00021962008600020014x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Andria R, Quaglietta CF, Lavini A, Mori M. Grain yield and water consumption of ethephon-treated corn under different irrigation regimes. Agron J. 1997;89(1):104–112. doi: 10.2134/agronj1997.00021962008900010016x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Earley EB, Slife FW. Effect of ethylene on growth and yield of corn. Agron J. 1969;61(5):821–823. doi: 10.2134/agronj1969.00021962006100050053x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norberg OS, Mason SC, Lowry SR. Ethephon influence on harvestable yield, grain quality, and lodging of corn. Agron J. 1988;80(5):768–772. doi: 10.2134/agronj1988.00021962008000050015x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodward EJ, Marshall C. Effects of plant growth regulators and nutrient supply on tiller bud outgrowth in barley (Hordeum distichum L.) Ann Bot. 1988;61(3):347–354. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson MB. Ethylene in root growth and development. Plant Hormone Ethylene, 1991.

- 43.Wei X, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Sun P, Li Z, Zhang M, et al. Analysis of differential expression of genes induced by ethephon in elongating internodes of maize plants. Front Agr Sci Eng. 2016;3(3):263–282. doi: 10.15302/J-FASE-2016103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin M, Pang C, Fan S, Song M, Wei H, Yu S. Global analysis of the Gossypium hirsutum L transcriptome during leaf senescence by RNA-Seq. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0433-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR. EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284(5423):2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 1998;12(23):3703–3714. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell. 2000;12(3):393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell. 1995;7(2):173–182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Susheng, Qi Tiancong, Wasternack Claus, Xie Daoxin. Jasmonate signaling and crosstalk with gibberellin and ethylene. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2014;21:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staswick PE, Su W, Howell SH. Methyl jasmonate inhibition of root growth and induction of a leaf protein are decreased in an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(15):6837–6840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pauwels L, Morreel K, De Witte E, Lammertyn F, Van Montagu M, Boerjan W, et al. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(4):1380–1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Q, Sun J, Zhai Q, Zhou W, Qi L, Xu L, et al. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MYC2 directly represses P LETHORA expressionduring jasmonate-mediated modulation of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23(9):3335–3352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keshishian EA, Rashotte AM. Plant cytokinin signalling. Essays in Biochemistry volume. 2015;58:13–27. doi: 10.1042/bse0580013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Köllmer I, Novák O, Strnad M, Schmülling T, Werner T. Overexpression of the cytosolic cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX7) from Arabidopsis causes specific changes in root growth and xylem differentiation. Plant J. 2014;78(3):359–371. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schaller GE, Street IH, Kieber JJ. Cytokinin and the cell cycle. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;21(21C):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmülling T, Werner T, Riefler M, Krupková E, Bartrina y Manns I. Structure and function of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase genes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis and other species. J Plant Res. 2003;116(3):241–252. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang C, Xu Y, Lu Y, Yu H, Gu M, Liu Q. The WRKY transcription factor OsWRKY78 regulates stem elongation and seed development in rice. Planta. 2011;234(3):541–554. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1423-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu Y, Liu Z, Wang L, Kim SG, Seo PJ, Qiao M, et al. WRKY71 accelerates flowering via the direct activation of FLOWERING LOCUS T and LEAFY in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2016;85(1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu F, Huaxia Y, Lu W, Wu C, Cao X, Guo X. GhWRKY15, a member of the WRKY transcription factor family identified from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), is involved in disease resistance and plant development. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM. The AP2/EREBP family of plant transcription factors. Biol Chem. 1998;379(6):633–646. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hattori Y, Nagai K, Furukawa S, Song X, Kawano R, Sakakibara H, et al. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature. 2009;460(7258):1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/nature08258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu K, Xu X, Fukao T, Canlas P, Maghirang-Rodriguez R, Heuer S, et al. Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature. 2006;442:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature04920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qi W, Sun F, Wang Q, Chen M, Huang Y, Feng Y, et al. Rice ethylene-response AP2/ERF factor OsEATB restricts internode elongation by down-regulating a gibberellin biosynthetic gene. Plant Physiol. 2011;157(1):216–228. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1749–1770. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang L, Bai M, Wu J, Zhu J, Wang H, Zhang Z, et al. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(12):3767–3780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komatsu K, Maekawa M, Ujiie S, Satake Y, Furutani I, Okamoto H, et al. LAX and SPA: major regulators of shoot branching in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11765–11770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932414100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang T, Hu Y, Jiang W, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):531–537. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pan X, Welti R, Wang X. Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(6):986–992. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed information on the obtained reads via RNA-Seq. (XLS 20 kb)

Expression of all genes in the 18 samples. (XLS 64722 kb)

Detailed information on the number of DEGs between each pair of compared groups. (JPG 275 kb)

List of KEGG pathways enriched in each comparison. (XLS 163 kb)

List of genes associated with various aspects of hormone homeostasis. (XLS 1631 kb)

List of genes related to hormone signal transduction in Fig. 2. (XLS 305 kb)

Additional figure showing the RT-PCR validation of three genes related to plant hormone signal transduction. (JPG 173 kb)

List of enriched GO categories in each comparison. (XLS 12995 kb)

List of the DEGs expressed in 10 modules. (XLS 9181 kb)

List of enriched GO categories in 10 modules. (XLS 2393 kb)

List of the expressed TF genes. (XLS 4511 kb)

Schematic diagram of the sampling position of cotton. (JPG 38 kb)

List of primers used for qRT-PCR. (DOC 44 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.