Abstract

Many neurons express a multiplicity of GABAA receptor subunit isoforms. Despite having only a single source of inhibitory input, the cerebellar granule cell displays, at various stages of development, more than 10 different GABAA subunit types. This subunit diversity would be expected to result in significant receptor heterogeneity, yet the functional consequences of such heterogeneity remain poorly understood. Here we have used single-channel properties to characterize GABAA receptor types in the synaptic and extrasynaptic membrane of granule cells. In the presence of high concentrations of GABA, which induced receptor desensitization, extrasynaptic receptors in outside-out patches from the soma entered long-lived closed states interrupted by infrequent clusters of openings. Each cluster of openings, which is assumed to result from the repeated activation of a single channel, was to one of three main conductance states (28, 17, or 12 pS), the relative frequency of which differed between patches. Such behavior indicates the presence of at least three different receptor types. This heterogeneity was not replicated by individual recombinant receptors (α1β2γ2S or α1β3γ2S), which gave rise to clusters of a single type only. By contrast, the conductance of synaptic receptors, determined by fluctuation analysis of the synaptic current or direct resolution of channel events, was remarkably uniform and similar to the highest conductance value seen in extrasynaptic patches. These results suggest that granule cells express multiple GABAA receptor types, but only those with a high conductance, most likely containing a γ subunit, are activated at the synapse.

Keywords: cerebellar granule cell, GABAA receptor, synaptic, single channel, subunit heterogeneity, differential targeting

GABA is the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, acting on ionotropic GABAAreceptors and metabotropic GABAB receptors. GABAA receptors are heteropentamers formed from multiple subunit types. To date, nineteen different mammalian subunit genes have been described (α1–6, β1–4, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, and ρ1–3), with further diversity arising from alternative splicing. Except for the ρ subunits, which assemble independently, and the π subunit, which occurs outside the CNS, GABAA receptors can be formed from a pool of some 20 different subunits, inclusive of splice variants (for review, see Barnard et al., 1998). Many neurons express multiple subunit types (Laurie et al., 1992; Wisden et al., 1992) and would be expected to display significant receptor heterogeneity, even allowing for restrictions governing subunit assembly (Connolly et al., 1996a;McKernan and Whiting, 1996). Numerous studies of recombinant receptors have shown that the biophysical and pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors depend critically on their subunit composition (for review, see Macdonald and Olsen, 1994), yet the functional consequences of receptor multiplicity remain poorly understood. For a number of transmitters, it has been suggested that distinct receptor subtypes may be targeted to specific regions of the neuronal membrane, possibly enabling cells to respond in different ways to the same transmitter. For GABAA receptors, specific targeting mechanisms have been proposed (Connolly et al., 1996b;Fritschy et al., 1998). Furthermore, immunohistochemical studies have provided direct evidence for segregation of subunit proteins within individual neurons (Koulen et al., 1996; Nusser et al., 1996, 1998;Fritschy et al., 1998).

Cerebellar granule cells express a particularly wide range of GABAA subunits, despite having a relatively simple morphology and receiving most of their inhibitory input from one cell type. Granule cells originate from progenitors in the external germinal layer, from where they migrate through the molecular layer, past the Purkinje cells, to take up their final positions in the internal granule cell layer. Here they receive GABA-mediated inhibitory input from Golgi cells (Eccles et al., 1967; Bisti et al., 1971; Hámori and Takács, 1989). In the rat, these processes take place during the first 3 postnatal weeks. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical data indicate that granule cells express, at various developmental stages, more than 10 different GABAAsubunits (for review, see Wisden et al., 1996). Indeed, even before synapse formation, granule cells in the external germinal layer contain mRNA for five subunits (α2, α3, β3, γ1, and γ2) (Laurie et al., 1992; Zdilar et al., 1992), and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings have shown that they express functional GABAA receptors (Farrant et al., 1995). In this study, we have sought to determine whether this diversity of subunit expression is reflected in the functional properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. Specifically, we have examined the single-channel properties of GABAA receptors in granule cells before and immediately after synapse formation. Our results suggest that granule cells express multiple GABAA receptor types, but possess mechanisms capable of differentially targeting these receptors, such that only a selected subset is incorporated into the postsynaptic membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cerebellar slices. Recordings were made from both premigratory and postmigratory cerebellar granule cells (external germinal layer and internal granular layer, respectively) in parasagittal slices (250 μm) obtained from 7-d-old (P7) Sprague Dawley rats. Slices were prepared and maintained as described previously (Farrant and Cull-Candy, 1991; Farrant et al., 1994). In brief, the animal was decapitated, and the brain was rapidly removed and placed in ice cold “slicing” solution composed of (in mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 4, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, glucose 25, pH 7.4, when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Slices were cut from the cerebellar vermis with a moving blade microtome (DTK-1000; Dosaka EM, Kyoto, Japan) and incubated at 30°C for ∼1 hr before being transferred to the recording chamber of a fixed-stage microscope (Axioskop-FS; Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Expression of recombinant GABAA receptors. Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK-293 cells; ATCC CRL 1573) were cultured in DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfections of murine α1, β2, β3, and γ2S GABAAreceptor subunit cDNAs (within a cytomegalovirus promotor-based mammalian expression vector) were performed using a standard electroporation procedure (Gene Electropulser II; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with 10 μg of total plasmid DNA. The subunits were tagged with the 10 amino acid 9E10 epitope from c-myc to allow independent verification of surface expression by means of antibody staining (Connolly et al., 1996a). Receptors incorporating 9E10-tagged subunits produce GABA-activated responses, which are indistinguishable from receptors composed of wild-type subunits (Connolly et al., 1996a;McDonald et al., 1998). Cells were co-transfected with cDNA for the cell-surface marker protein CD8 and used for recording 24 hr after transfection. Approximately 10 min before recording, cells were exposed to polystyrene beads coated with an antibody to CD8 (Dynal, Great Neck, NY) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, allowing visual detection of transfected cells.

Solutions and drugs. During recording, cerebellar slices and HEK-293 cells were continuously perfused at room temperature (23–25°C) with a solution containing (in mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, NaHCO326, NaH2PO4 1.25, glucose 25, pH 7.4 when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. For whole-cell and outside-out patch recording, the pipette solution (intracellular solution) contained (in mm): CsCl 140, NaCl 4, CaCl2 0.5, HEPES 10, EGTA 5, Mg-ATP 2, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH. The following drugs were added to the external solution as indicated: d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5; Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), bicuculline methobromide (Research Biochemicals, Natick, MA), SR-95531 (Research Biochemicals), strychnine (Sigma, Poole, UK), tetrodotoxin (TTX; Sigma), and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Tocris Cookson).

Recording procedures. Standard whole-cell and outside-out voltage-clamp recordings were made using Axopatch-1D and Axopatch-200A amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Cells were visualized with Nomarski differential interference optics (40× water-immersion objective, total magnification 320–1000×). Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (GC-150F; Clark Electromedical, Pangbourne, UK), coated with Sylgard resin (Dow Corning 184), and fire-polished to a resistance of ∼10 MΩ.

Data acquisition and analysis. Granule cell capacitance (3.7 ± 0 0.4 pF), input resistance (9.9 ± 1.8 GΩ), and series resistance (39.9 ± 6.0 MΩ) were determined in a subset of cells (n = 14) from current transients recorded in response to 10 mV hyperpolarizing voltage steps. These currents were low-pass-filtered at 20 kHz (−3 dB, eight-pole Bessel-type filter) and digitized at 200 kHz (Intel 80486-based personal computer, Digidata 1200 interface and pCLAMP 6.1 software; Axon Instruments). In other recordings, cell parameters were determined directly from the amplifier settings; no series resistance compensation was used. All other data were recorded on digital audio tape [DTR-1204; BioLogic, Claix, France (DC to 20 kHz)] with the amplifier filter (four-pole Bessel type) set at 10 kHz.

Single-channel currents in outside-out patches.GABA-activated single-channel currents recorded from outside-out patches were replayed from tape filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. To determine the slope conductance of the channels, recordings were made at three to five potentials between −40 and −80 mV; all-point amplitude histograms were constructed from openings at each potential (Fetchan; pCLAMP 6.1). The mean single-channel current, determined from Gaussian fits to these amplitude distributions, was plotted against voltage, and the data were fitted by linear regression. In the case of multiple conductance levels within a single patch, all current–voltage data were fitted simultaneously with the constraint of a common reversal potential.

Individual clusters of openings, separated by at least 1 sec, were extracted from the digitized record for further analysis. The probability of the channel being open during each cluster (Po) was calculated according toPo = cluster integral/(cluster length × cluster main amplitude), where the main amplitude for each cluster was calculated from the all-point amplitude histogram (Colquhoun and Ogden, 1988; Newland et al., 1991). The baseline was taken as the mean of the current value at the beginning and end of each cluster.

Single-channel currents were also analyzed using the method of time course fitting (Colquhoun and Sigworth, 1995) (EKDIST;http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Pharmacology/dc.html). Currents were replayed from tape, filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 20 kHz (CED 1401+ interface; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Individual openings were fitted by the step response function of the recording system; only openings longer than two filter rise times (reaching 98.8% of their full amplitude) were included. The mean amplitude levels of single-channel currents were determined from fits of Gaussian distributions to the cursor-fitted amplitudes. Channel open periods are given as the weighted time constants of exponential functions fitted to the distributions of open periods. Distributions were fitted by the method of maximum likelihood (Colquhoun and Sigworth, 1995). Conductance values for single-channel events are given as slope conductance where measured, or as chord conductances (γchord) at single potentials, determined according to γchord =i/(Vcmd −Erev), where i is the observed single-channel current, Vcmd the command voltage, and Erev the reversal potential.Erev was taken as +0.94 mV, the mean value measured from current–voltage relationships in 13 outside-out patches from internal granule cells.

Spontaneous IPSCs. For analysis of IPSCs, currents were replayed from tape and filtered at 5 or 2 kHz before digitization at 40 or 10 kHz, for measurement of rise and decay times, respectively. IPSCs were identified by eye from the digitized records and were analyzed using software (“N” v1.0) written by Stephen Traynelis (Emory University, Atlanta, GA). Current decays were fitted using either “N” or Origin 4.10 (Microcal, Northampton, MA).

Nonstationary fluctuation analysis. To determine the conductance of synaptic GABAA channels, IPSCs were analyzed by nonstationary fluctuation analysis. To isolate fluctuations in the current decay attributable to stochastic channel gating, the mean waveform was scaled to the peak of individual IPSCs (Traynelis et al., 1993; Silver et al., 1996). The requirements for such analysis include the stability of current decay time course throughout the recording and the absence of any correlation between decay time course and peak amplitude. The relationship between the peak-scaled variance and the mean current is given by ρPS2 = i − 2/NP + ρB2, where ρPS2 is the peak-scaled variance, is the mean current, i is the weighted-mean single-channel current, NP is the number of channels open at the peak of the IPSC, and ρB2 is the background variance. In these experiments IPSCs were analyzed from selected epochs in each of 10 cells (25–214 IPSCs) in which the peak amplitude was stable over time and in which there was no correlation between current decay (62% decay time) and peak amplitude (p > 0.05, Spearman rank-order correlation test). Although the relationship between ρPS2 and can be skewed if channels open for the first time after the peak of the IPSC, meaningful values for the weighted-mean single-channel current (i) can be obtained by analyzing the variance of the tail of the IPSC (Traynelis et al., 1993; Nusser et al., 1997; Traynelis and Jaramillo, 1998). However, in this case, the ρPS2 − relationships were parabolic, and there was no significant difference (p = 0.69; paired Student’s t test) between the estimate of i obtained from fitting the full parabola or its initial 50%, corresponding to the tail of the IPSC. The values reported are those from the full fit. When pooling the current–variance data across cells, we plotted normalized variance (ρPS2 − ρB2/Imax) against normalized current (/Imax), whereImax is the peak synaptic current for each cell.

Direct resolution of synaptic channels. For analysis of channel openings directly resolved in the IPSC decay, all-point amplitude histograms were constructed from individual IPSCs (filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz). A mixture of Gaussian distributions was fitted to the resulting histograms using a maximum likelihood fitting procedure. The amplitudes of steps in the tail of IPSCs were calculated from the inter-peak intervals in each all-point histogram. The presence of additional conductance states within the synaptic channel openings was investigated using a variant of the sublevel detection method of Patlak (1988). In this case, the digitized record was scanned with a rolling window of 9–15 points and for all positions of the window in which the variance was below an arbitrarily defined limit (typically one to two times the baseline variance), median values were calculated (Mathcad; MathSoft, Cambridge, MA) and used to construct the amplitude histogram. All results are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed with STATISTICA 5.1 (StatSoft, Tulsa OK). Differences between groups were tested using either the Student’s t test (when measures were normally distributed; Shapiro–Wilk test) or the Mann–Whitney U test and considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in internal granule cells are heterogeneous

The single-channel properties of cerebellar granule cell GABAA receptors have been studied previously for neurons in culture and in slices (Kilic et al., 1993; Kaneda et al., 1995; Amico et al., 1998). Although multiple conductance states have been observed in both preparations, it remains unclear whether the openings result from multiple states of a single receptor type or from different receptor types (Kaneda et al., 1995). To answer this question, we examined currents evoked by high concentrations of GABA (in a total of 22 patches recorded from 11 different animals) that were sufficient to induce marked receptor desensitization. Under these conditions, GABAA receptors enter long-lived closed states, and channel openings occur in infrequent clusters, each assumed to result from the repeated activation of a single receptor (Sakmann et al., 1980, Hamill et al., 1983; Colquhoun and Ogden, 1988; Newland et al., 1991). Therefore, if different conductance states arise from different receptor types, then their activation should give rise to distinct cluster types.

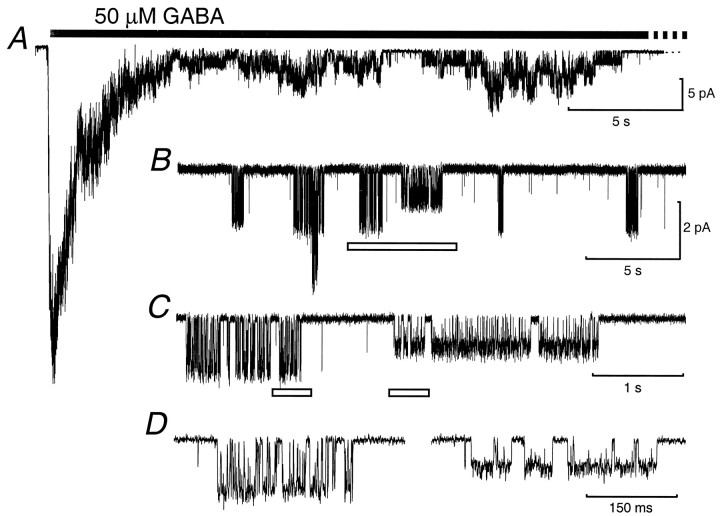

In the presence of 10 μm AP5, 5 μm CNQX, and 200 nm strychnine, to block NMDA, non-NMDA, and glycine receptors, respectively, the application of 50 μm GABA to outside-out patches from granule cells in the internal granular layer resulted in a large inward current (Fig.1A). In the continued presence of GABA, the current slowly decayed until it was possible to resolve openings and closures of single channels (Fig.1B). Channel openings occurred in prolonged but infrequent clusters. However, each cluster did not necessarily open to the same main conductance state; although not always present in each patch, three distinct cluster types were observed overall. In the example shown in Figure 1, the openings within individual clusters were to one of two levels, corresponding to what we term “high-conductance” and “low-conductance” events (Fig.1C,D). Clusters of high-conductance openings were observed in all 13 patches analyzed. These had a mean slope conductance of 27.6 ± 0.7 pS (Fig. 2). A “mid-conductance” cluster-type, with a mean slope conductance of 16.9 ± 0.5 pS, was present in 10 of the patches. Low-conductance clusters were present in four patches and had a mean slope conductance of 11.6 ± 1.2 pS.

Fig. 1.

Activation of extrasynaptic GABAAreceptors by a high concentration of GABA evokes clusters of channel openings. A, Application of 50 μm GABA (solid bar) to an outside-out patch from the somatic membrane of a P7 internal granule cell caused a large inward current that rapidly desensitized in the continued presence of agonist (holding potential −60 mV). B, Discrete single-channel clusters were separated by prolonged closed periods. C, Expansion of trace in B (open bar) showing two types of single-channel clusters that differ in their main conductances. D, Further expansion oftrace in C (open bars) showing more clearly the conductance difference between the two clusters and highlighting an apparent difference in kinetic behavior. For display, records were filtered at 1 kHz.

Fig. 2.

Patches from somatic membrane display different proportions of channel openings to three main conductance states.A, Current–voltage relationships from channels in three different patches. The left-hand panel illustrates data from a patch that exhibited clusters of one type, giving a slope conductance of 28 pS. The middle panel shows data from a patch in which clusters opened to one of two current levels, giving slope conductances of 28 and 17 pS. The right-hand panelshows data from a third patch in which clusters exhibited openings to one of three current levels, giving slope conductances of 26, 18, and 12 pS. B, The distribution of different cluster types between patches. High-conductance clusters (●) were recorded in all 13 patches and had a mean single-channel conductance of 27.6 pS, shown by the solid line (dotted lines indicate ±1 SEM). Ten of 13 patches also contained clusters of openings that had a mid conductance (■; 16.9 pS). Four patches displayed clusters of openings that had a low conductance (▴; 11.6 pS). Filled bars indicate the four different combinations of cluster types recorded in different patches and their relative frequency (as a percentage).

Patches could be divided into four groups according to the cluster types present (Fig. 2). The majority of patches (n = 7) displayed high- and mid-conductance cluster types, three patches contained all three cluster types, and two patches exhibited only high-conductance clusters, whereas high- and low-conductance clusters were seen in only one patch (Fig. 2B). Although the total length of recording for each patch differed (∼1–15 min), the likelihood of observing clusters of different conductance within a given patch did not reflect any underlying difference in the frequency of opening. Thus, when present, the various cluster types occurred with similar mean frequencies (∼0.06, 0.05, and 0.05 Hz, for high-, mid-, and low-conductance clusters, respectively).

To test for the presence of channel subconductance states within clusters and to determine any kinetic differences between the three cluster types, we reexamined clusters of openings by the method of time course fitting (Colquhoun and Sigworth, 1995). This approach revealed that high-conductance clusters (n = 9 patches) contained openings with a main chord conductance of 28.5 ± 0.8 pS and a subconductance state of 17.4 ± 1.0 pS. This lower conductance state was present in each cluster and accounted for a consistent but relatively minor fraction of openings (10.1 ± 2.6%). In all patches tested, direct transitions were observed between the main and lower conductance states. Time course fitting of the mid-conductance clusters (main state 19.9 ± 1.9 pS;n = 4) also revealed a subconductance of 10.6 pS in two patches (11.2% of openings). Low-conductance clusters were analyzed in five patches and had a single-channel conductance of 14.4 ± 0.4 pS, with no apparent subconductance states. In some recordings, high-conductance clusters appeared to display briefer openings than the mid- or low-conductance clusters (Fig. 1D). Indeed, time course fitting revealed shorter contiguous open periods in the high-conductance clusters (5.2 ± 0.9 msec) compared with the mid- (6.5 ± 1.2 msec) and low-conductance clusters (9.9 ± 2.9 msec). This difference between high- and low-conductance openings was significant (p < 0.05, Mann–WhitneyU test). Together, the subconductance and open period data emphasize the different properties of the three cluster types.

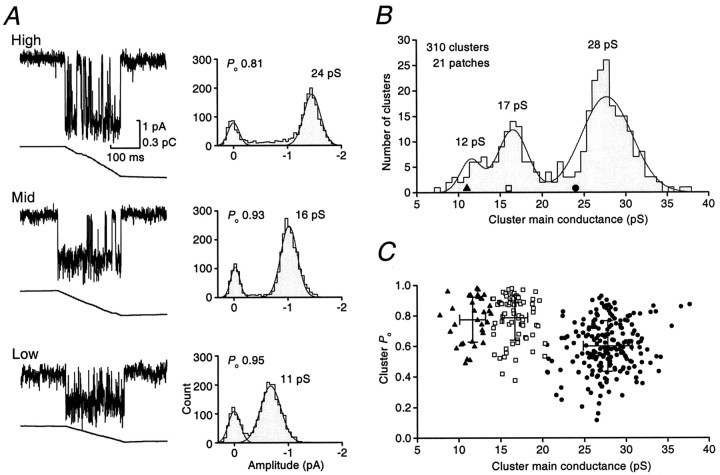

To examine the variation between clusters, we next studied all clusters individually, measuring both the main cluster conductance and the proportion of time for which the channel was open during a cluster (Po) (Colquhoun and Ogden, 1988; Newland et al., 1991). The main conductance state for individual clusters was obtained from the largest Gaussian component in fits to individual all-point histograms and Po values calculated after the integration of each cluster (see Materials and Methods). The clusters illustrated in Figure3A are from a single patch that exhibited all three cluster types. The distribution of these three clusters among the entire sample is shown by the symbols in Figure3B. As shown in Figure 3C, the high-conductance clusters exhibited a lower mean Po than the mid- and low-conductance clusters. The Po calculated for 224 high-conductance clusters (chord conductance 27.9 ± 2.7 pS) was 0.6 ± 0.2, whereas the mid-conductance (16.7 ± 1.6 pS, n = 92) and low-conductance (11.7 ± 1.5 pS,n = 37) clusters had identicalPo values of 0.8 ± 0.1. ThePo value for high-conductance clusters was significantly lower that those for mid- and low-conductance clusters (p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney Utest).

Fig. 3.

Extrasynaptic receptors exhibit channel clusters that fall into distinct classes with different main conductance states and open probabilities. A, Examples of high-, mid-, and low-conductance channel clusters recorded from a single somatic patch from a P7 internal granule cell (−60 mV; for display, records were filtered at 1 kHz). The integral is plotted below each current record. Shown to the right of each cluster is its corresponding all-point amplitude histogram with the calculated chord conductance and Po (see Materials and Methods). B, The distribution of all chord-conductance estimates from 310 individual clusters recorded from a total of 21 patches. The histogram was fitted with the sum of three Gaussian distributions, with peaks at 12, 17, and 28 pS (compare with the slope conductance estimates in Fig. 2). The symbolssuperimposed on the distribution indicate the conductance for each of the three clusters shown in A. C, The relationship between cluster main conductance and clusterPo. The distinction between low-conductance (▴), mid-conductance (■), and high-conductance clusters (●) is based on the distribution in B and calculated by the method of minimum misclassification (Colquhoun and Sigworth, 1995).Superimposed bars indicate the mean and SD of main conductance and Po for each cluster type.

Multiple receptor types are present before synapse formation

One interpretation of these observations is that the clusters of openings represent activity of individual channels and the different types of clusters arise from three or more distinct receptor types with different main conductance states. Granule cells at P7 are in the early stages of synapse formation. GABA-positive Golgi axon terminals are first seen in the internal granular layer at P2–P3 (Meinecke and Rakic, 1990), whereas spontaneous IPSCs can be recorded at P4 and are present in ∼70–80% of cells by P7 (Brickley et al., 1996; this study). The heterogeneous properties of GABAA channels that we observe at this age could therefore reflect developmental differences between cells. Indeed, it has been suggested that activation of GABAA receptors themselves, for example after synaptogenesis, may be responsible for triggering the expression of different GABAA receptor types (for review, see Carlson et al., 1998). To examine the properties of GABAA receptors before synapse formation, we recorded from premigratory cells in the external granule cell layer at P7. In patches from these cells there were also three distinct cluster types, similar to those present in postmigratory granule cells. Clusters of high-conductance openings (chord conductance 25.2 ± 0.9 pS) were observed in eight of nine patches examined, mid-conductance clusters (17.0 ± 0.6 pS) were present in four patches, and low-conductance clusters (12.2 ± 1.4 pS) were present in three patches. A single patch contained clusters of the mid-conductance type (17 pS) alone and lacked any high-conductance clusters. These results suggest, therefore, that heterogeneity of channel conductance is not solely the result of developmental differences between cells.

The simplest explanation for our observations is that the three different cluster types arise from distinct receptor types that differ in their main conductance states. It is also possible, however, that all openings arise from a single receptor type that undergoes some form of “modal” gating to preferred conductance states that are segregated within different clusters. However, intracellular modulation of GABAA receptor activity, for example by phosphorylation, is known to influence channel kinetics but does not affect single-channel conductance (Jones and Westbrook, 1997; Amico et al., 1998). The variable frequency of occurrence of different cluster types between patches also argues against the possibility that a single receptor type is responsible for all three cluster types. However, we tested this possibility further by recording from a homogenous population of GABAA receptors in HEK-293 cells. These were transiently transfected with α1, β2, and γ2S subunits, which, given their preferential coassembly, are thought to form only a single type of GABAA receptor (Angelotti and Macdonald, 1993; Tretter et al., 1997). If each cluster type in granule cells reflects a different “mode” of the same receptor rather than different receptors, then one might also expect to record clusters with different main conductance states from a “pure” receptor population.

Recombinant GABAA receptors

When patches from HEK-293 cells expressing α1, β2, and γ2Ssubunits were initially exposed to 50 μm GABA, a large inward current was elicited that rapidly declined until single-channel openings could be observed. This pattern of activity was broadly similar to that seen with native receptors, and the overall cluster frequency (0.17 ± 0.03 Hz, n = 12; after four separate transfections) was not significantly different from that observed in patches from internal granule cells (0.11 ± 0.02 Hz,n = 17; p > 0.05, unpaired Student’st test). However, unlike native receptors, each cluster of openings from recombinant receptors appeared to be to the same main conductance state (compare Fig.4A with 1B).

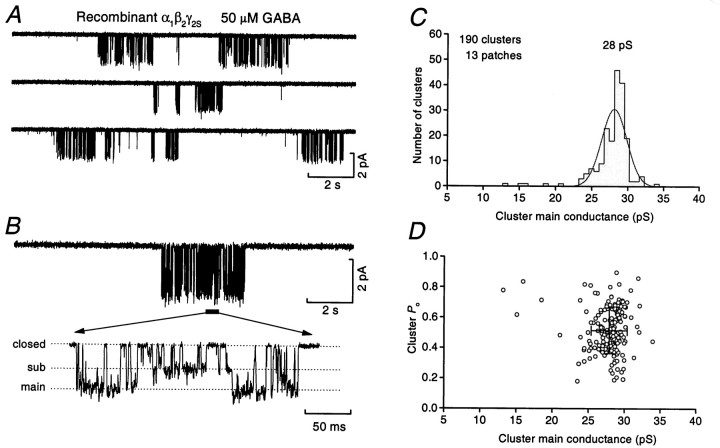

Fig. 4.

Recombinant α1β2γ2S receptors exhibit a single type of channel cluster. A, Clusters of channel openings recorded in an outside-out patch from an HEK-293 cell transiently transfected with α1, β2, and γ2S subunits in the continued presence of 50 μm GABA (−60 mV). All clusters contain high-conductance openings. B, An individual cluster recorded from the same patch. Inset shows an expanded view of part of the cluster (solid bar) illustrating the presence of clear sub-level transitions (for display, records were filtered at 1 kHz). The dotted linesindicate the closed, sub, and main conductance states, as determined from fits to an all-point histogram constructed for this patch (data not shown). C, The distribution of all chord-conductance estimates (main conductance) from 190 individual clusters recorded from a total of 13 patches. Most of the clusters are of the high-conductance type such that a single Gaussian adequately describes this distribution. Five cluster measurements lay outside the single Gaussian distribution. In three of these, high-conductance openings were present within the clusters, but most of the openings were to the subconductance state. D, The relationship between the cluster main conductance and the cluster Posuggests the existence of a single main population of cluster types for this recombinant GABAA receptor.

In 13 patches a sufficient number of clusters was recorded to allow construction of all-point amplitude histograms, yielding a main chord conductance of 25.9 ± 0.3 pS. Clear transitions to a lower conductance state were also evident during these high-conductance clusters (Fig. 4B). In four patches this subconductance state was sufficiently frequent to be discernible from the all-point amplitude histograms (data not shown), giving a conductance of 14.6 ± 1.1 pS. We next analyzed each cluster independently (as for native receptors; see above). For 190 clusters from 13 patches, the main conductance state (the largest component of the all-point histogram) was 27.9 ± 0.2 pS, and thePo value was 0.50 ± 0.01 (n = 190 clusters). These values were similar to those for the native high-conductance clusters (compare Fig. 4C,Dwith Fig. 3B,C).

This relatively simple channel behavior was also seen with a second combination of subunits. Thus, when a transfection was performed with a β3 subunit rather than the β2 subunit, the resulting receptors also gave rise to clusters of an apparently uniform type, with a main single-channel conductance of 28.0 ± 1.0 pS, a subconductance state of 17.4 ± 1.9 pS (n = 4), and a Po of 0.40 ± 0.02 (89 clusters). In agreement with the impression of uniform cluster type for both α1β2γ2S and α1β3γ2S receptors, 286 of the 289 clusters analyzed (∼99%) contained openings to the high-conductance state (Fig. 4). This is clearly different from the situation in native receptors (internal granule cells) where 107 of 310 clusters (35%) were of a mid- or low-conductance type.

Taken together, these results support the idea that, for native receptors, clusters of openings with different main conductance states represent the activity of different receptor types, each having a distinct main conductance and, in the case of high- and mid-conductance types at least, a less frequently occurring subconductance state. Because recombinant GABAA receptors containing different subunits can give rise to channels with similar conductances (see above) (Macdonald and Olsen, 1994), each cluster type seen in granule cells could arise from receptors with several molecular compositions. Thus, we conclude that at least three receptor types are present in the somatic membrane of both premigratory and postmigratory granule cells. Given this diversity of extrasynaptic receptors, we next asked whether such diversity occurred at the synapse.

GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs in cerebellar granule cells

In the presence of 5 μm CNQX and 10 μmAP5, >70% of cells (86/110, from 34 animals) exhibited spontaneous IPSCs (Fig. 5A). The reversal potential for IPSCs (+8.4 ± 0.6 mV, n = 10) was close to the expected Cl− ion equilibrium potential of +2 mV given the near symmetrical Cl− ion distribution. The IPSCs were reversibly blocked by the competitive GABAA receptor antagonists bicuculline methobromide (10 μm) and SR-95531 (100 nm) but were unaffected by the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (200 nm) (data not shown) (Kaneda et al., 1995). As previously reported, the IPSCs were greatly reduced in frequency by 200 nmtetrodotoxin (from ∼1 Hz to <0.1 Hz), indicating that most events result from action potentials in presynaptic Golgi cells (Kaneda et al., 1995; Brickley et al., 1996; Rossi and Hamann, 1998).

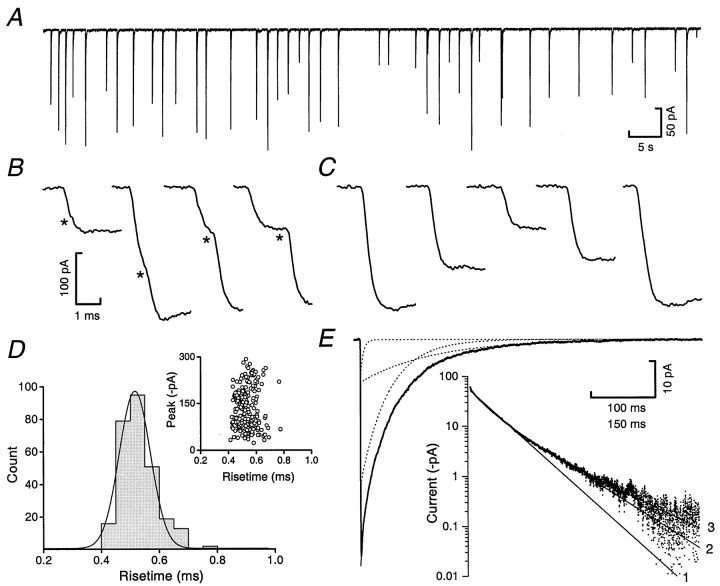

Fig. 5.

Spontaneous IPSCs display a rapid rise and slow, multi-exponential decay. A, Continuous record showing spontaneous IPSCs recorded from a P7 internal granule cell in the presence of 5 μm CNQX, 10 μm AP5, and 200 nm strychnine (−70 mV; 2 kHz filtering). B, The initial phase of some IPSCs shows obvious inflections caused by superimposition of events (asterisks; 5 kHz filtering).C, Most IPSCs exhibit monotonic rises with no obvious inflections. Only IPSCs that exhibited such a monotonic rise were included in any further analysis. D, The distribution of the resulting 10–90% rise times is well described by a single Gaussian. The inset illustrates the lack of relationship between rise time and peak amplitude for IPSCs recorded in one cell.E, An example of an averaged IPSC with its decay fitted by the sum (solid line) of three exponentials (dotted lines). The inset shows the average waveform (dots) and single (1), double (2), or triple (3) exponential fits (solid lines) displayed with current on a log scale; only the triple exponential fit adequately describes the current decay (2 kHz filtering).

For each cell, an average IPSC waveform was generated from >50 events aligned on their rising phase. Superimposed events were excluded from analysis, and we included only those IPSCs that had a monotonic rising phase lacking inflections (Fig. 5B,C) and that returned to baseline without contamination from subsequent events. As expected from the electrically compact nature of the granule cell (Silver et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1997), the majority of IPSCs had a rapid rising phase (Fig. 5C) with a 10–90% rise time that was not correlated with peak amplitude (Fig. 5D). The average IPSC waveforms from 14 cells had a 10–90% rise time of 372 ± 19 μsec and a decay best described by the sum of three exponentials (τ1 = 8.0 ± 1.1 msec, 22%; τ2 = 33.5 ± 2.4 msec, 58%; τ3 = 102.9 ± 8.2 msec) (Fig. 5E).

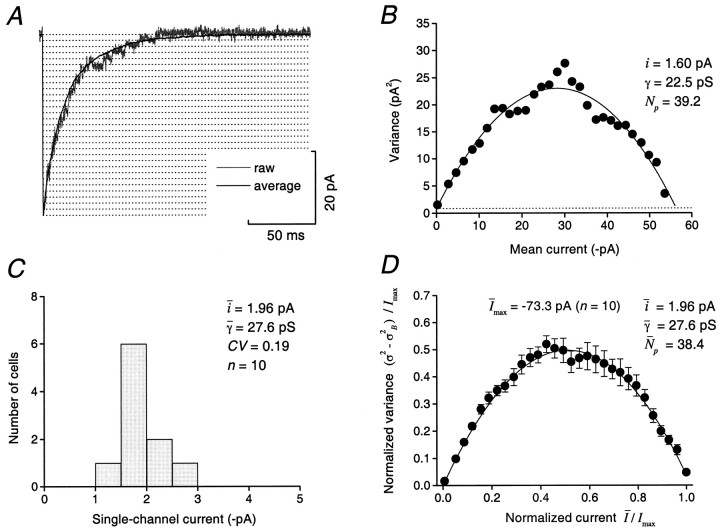

Single-channel properties of synaptic GABAA receptors estimated from fluctuation analysis

To obtain an estimate of the single-channel conductance for receptors underlying the IPSC we used the method of peak-scaled nonstationary fluctuation analysis (Traynelis et al., 1993; DeKoninck and Mody, 1994; Silver et al., 1996; Traynelis and Jaramello, 1998). This approach enables channel conductance to be determined from the variance of individual synaptic events about the mean synaptic waveform. For each of 10 cells, the mean waveform was scaled to the peak of each IPSC, and the mean current and its variance were determined for 30 bins of equal amplitude (Fig.6A). In all cases, plotting the mean current against the variance yielded a characteristic parabolic relationship. For the example shown in Figure6B, fitting the current–variance relationship (see Materials and Methods) gave a weighted-mean single-channel current of 1.60 pA (corresponding to a chord conductance of 22.5 pS) and a mean of 39 channels open at the peak of the IPSC. The single-channel current values from 10 cells were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test), with a mean of 1.96 ± 0.13 pA, corresponding to a conductance of 27.6 ± 1.8 pS (Fig. 6C). Plotting the normalized variance against the normalized current (see Materials and Methods) for data pooled from all 10 cells confirmed the almost perfect parabolic relationship between mean current and variance (Fig.6D), suggesting that the weighted-mean conductance is the same for channels contributing to different phases of the IPSC decay.

Fig. 6.

Peak-scaled nonstationary fluctuation analysis of IPSCs reveals uniform weighted-mean single-channel conductance of synaptic receptors. A, The average waveform of 74 IPSCs (solid line) is shown scaled to the peak of an individual IPSC (gray line; 2 kHz filtering). Thehorizontal dotted lines represent the 30 amplitude bins used to determine values of mean current and variance.B, A plot of mean current against variance for the cell shown in A. The plot is fitted with a parabolic relationship to give the weighted-mean single-channel current (i; also given as conductance, γ) and the number of channels open at the peak (Np). Thedotted line indicates the baseline variance.C, Histogram of weighted-mean single-channel current obtained from a total of 10 cells illustrating the uniform distribution of conductance. D, A plot of normalized current against normalized variance with data pooled from all 10 cells (error bars represent SEM).

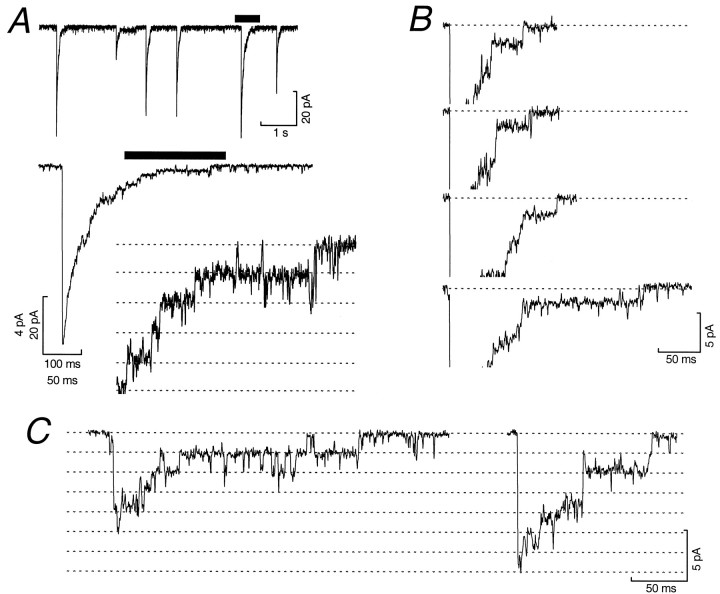

Direct resolution of synaptic channel events

In the most favorable whole-cell recordings (baseline current–variance <330 fA2; mean 252 ± 22 fA2; n = 8; 1 kHz filter), the high input resistance and electrical compactness of cerebellar granule cells allowed us to resolve individual channel closures in the tail of IPSCs. This is illustrated in Figure7A, which shows successive enlargements of the tail of an individual IPSC. For each of eight cells examined, channel-like steps could be clearly identified in the decay phase of all IPSCs, regardless of the IPSC peak amplitude (Fig.7B). Moreover, for each of the smallest IPSCs observed, their peak was an integer multiple of the last resolvable current step. For example, in the case of the two IPSCs shown in Figure7C, the waveforms could be divided into five and seven steps of equal amplitude.

Fig. 7.

Unitary current steps can be resolved in the decay of spontaneous IPSCs. A, Successive enlargements (solid bars) of the decay phase of a spontaneous IPSC recorded from a P7 internal granule cell (−70 mV). The second enlargement clearly shows the stepped nature of the IPSC decay (theequally spaced dashed lines illustrate the approximate amplitude levels of the steps). B, Four representative IPSCs showing the consistent presence of a channel-like step at the end of each IPSC. The peaks of the IPSCs have been truncated for display, and the dotted line indicates the pre-event baseline current. C, Two selected IPSCs, representative of the smallest events recorded. In each case the peak amplitude is an integer multiple (5 and 7) of the last step amplitude (dotted lines). For display, records were filtered at 1 kHz.

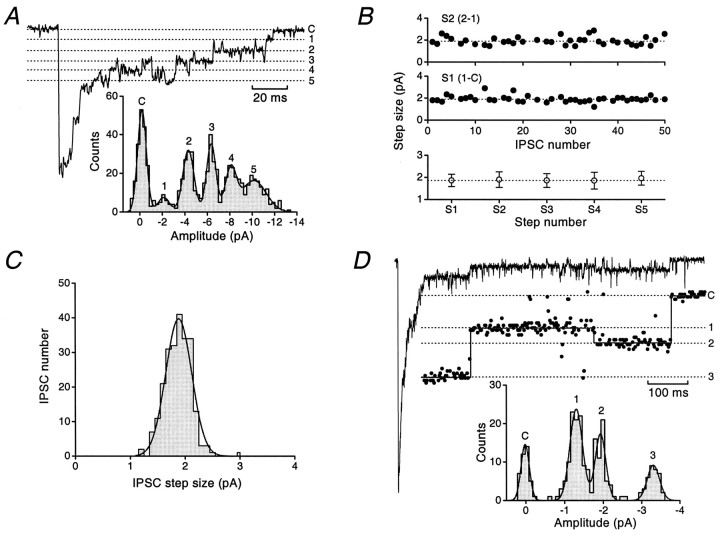

To quantify the size of the current steps, all-point amplitude histograms were constructed from individual IPSCs (Borst et al., 1994). For the IPSC shown in Figure8A, this revealed a series of six equally spaced peaks (inset). The first peak in the histogram corresponds to the closed level (C), and the five subsequent peaks result from steps in the tail of the IPSC. The histogram was fitted with the sum of six Gaussian distributions, and step sizes were determined from the inter-peak intervals (1.7, 2.2, 1.9, 1.8, and 2.1 pA). In the cell from which this IPSC was recorded, the average step size determined from 47 steps in 27 individual IPSCs was 2.04 ± 0.04 pA, corresponding to a single-channel chord conductance of 28.7 pS. The amplitude of these steps appeared consistent within individual IPSCs. Furthermore, the step size was consistent for different IPSCs in the same cell and for IPSCs in different cells. Figure 8B shows data from one cell in which the step size for the final two resolvable closures (S1 and S2) was determined for 50 consecutive IPSCs. Because these spontaneous IPSCs arise from an unknown number of different synapses, it is clear that the conductance of the underlying receptors is similar not only at individual synapses but also at different synapses on the same cell. As is also apparent from Figure 8B, the amplitudes of the last five steps (S1–S5) determined from all events were remarkably consistent. Finally, as shown in Figure8C, the IPSC step size (calculated as a single value for each IPSC; taking a mean value when multiple steps were resolved) was normally distributed, with a low coefficient of variation (CV) (mean 1.87 ± 0.02 pA, n = 234 IPSCs, corresponding to a conductance of 26.4 pS; CV = 0.13). A similar distribution (data not shown) was obtained when all resolved steps (n = 480) were considered individually and had a CV of 0.17.

Fig. 8.

Analysis of resolvable current steps in IPSCs reveals a uniform single-channel conductance and a rare lower conductance state. A, Quantitative analysis of a stepped IPSC waveform recorded from a P7 internal granule cell (1 kHz filtering). The IPSC has five steps in its decay, seen as clearly resolved peaks in its all-point amplitude histogram (inset). The positions of the baseline (C) and the numbered dashed lines(1–5) are taken from the fit of six Gaussian components to the amplitude histogram. B, Plots of the inter-peak step size for the last two steps (S1 andS2) calculated for 50 consecutive IPSCs recorded in the same cell as A. The bottom panelillustrates the consistency of the step size for the last five channel closures (S1–S5) recorded from a total of eight cells. The mean step sizes (open symbols) and the SD are plotted for each step. The dotted line shows the mean value for S1. C, A histogram of IPSC step size (calculated as a single value for each of 234 IPSCs recorded from 8 cells) fitted with a single Gaussian. D, A single IPSC in which different sized steps were observed in the decay (1 kHz filtering). The inset was obtained after smoothing of the trace (see Materials and Methods) to better illustrate the steps in the waveform. The dotted lines superimposed on the trace show current levels obtained from peaks of the fit to the all-point histogram. C indicates the final closed state, and the dashed lines 1–3 represent the values of the three open levels observed in the decay. The final step size was calculated from the inter-peak interval between C and2, and the preceding smaller step size was calculated between C and 1.

Together these observations suggest that GABAA receptors in the synaptic membrane of granule cells have a uniform single-channel conductance, similar to the high-conductance channels identified in the extrasynaptic membrane. As noted above, one feature of the high-conductance extrasynaptic receptors is the occasional presence of a subconductance state. If synaptic receptors are similar to these extrasynaptic receptors, then they too might be expected to display a subconductance state. Indeed, in a small number of IPSCs, channel openings of an apparently lower conductance were detected in conjunction with the high-conductance events. To increase the resolution of channel openings and minimize the contribution of background noise, we applied a smoothing procedure to these selected IPSCs (see Materials and Methods). This confirmed that a very small proportion of resolvable synaptic channel openings (∼2%; 9 out of the total of 480) were to a distinct lower conductance level. One particularly clear example is illustrated in Figure8D. In the tail of this IPSC it is possible to discern a prolonged opening of lower amplitude before the final full-amplitude channel closure. This is made clearer in the smoothed waveform and its associated amplitude histogram (Fig.8D, insets). Openings of this type could be resolved in nine IPSCs and had a mean amplitude of 1.07 ± 0.06 pA (15.1 pS), significantly lower (p < 0.05, paired Student’s t test) than the main conductance state determined in the same IPSCs (1.78 ± 0.06 pA; 25.1 pS). The temporal resolution afforded by whole-cell recordings makes it difficult to say whether these openings represent true subconductance states or whether this lower level results from the opening of a separate mid-conductance GABAA receptor. Regardless of its origins, the lower conductance state contributes very little to total charge transfer during a single IPSC.

Finally, it is interesting to note that individual channel openings as well as the more obvious channel closures could also be seen during the IPSC decay (Figs. 7C, 8A). The lack of skew in the parabolic current–variance relationship (Fig. 6) suggests that few, if any, channels open for the first time after the peak of the IPSC (Traynelis et al., 1993). It would thus appear that these events reflect the reopening of GABAA receptors after their synchronous opening at the peak of the synaptic current. This delayed reopening is thought to occur on exit from desensitized states, entered after the brief exposure to high concentrations of transmitter in the cleft, and has been suggested to prolong the decay of the IPSC (Jones and Westbrook, 1995).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have examined the single-channel properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in developing cerebellar granule cells. On the basis of differences in channel conductance, we suggest that GABAA receptors in premigratory granule cells before synapse formation are heterogeneous, with at least three receptor types present. This heterogeneity is maintained in granule cells that have recently migrated and whose extrasynaptic GABAA receptors display very similar properties. By contrast, receptors at newly formed synapses open, almost exclusively, to a single, high-conductance state.

Subunit diversity and channel heterogeneity

In granule cells the pattern of GABAA receptor subunit expression is developmentally regulated. In situhybridization studies have shown that premigratory cells express α2, α3, β3, γ1, and γ2subunit mRNA (Laurie et al., 1992). After migration, levels of α2, α3, and γ1mRNA decline, whereas levels of α1 and γ2mRNA increase dramatically. After the first postnatal week, α6 and δ subunit expression become significant (Laurie et al., 1992; Jones et al., 1997), leading to the predominance of α1, α6, β2, β3, γ2, and δ subunit mRNAs in the adult. Immunohistochemical studies of adult tissue have confirmed the presence of the corresponding proteins (Zimprich et al., 1991; Fritschy et al., 1992; Nusser et al., 1998), and a combination of techniques have suggested that at least four receptor types may be present (α1β2/3γ2, α6β2/3γ2, α6β2/3δ, and α1α6β2/3γ2) (Nusser et al., 1998). At the age we have examined (P7) it is likely that α6 and δ proteins are not yet expressed; nevertheless, multiple α, β, and γ subunits will be present. Thus the potential for receptor heterogeneity exists at all stages of granule cell development (for review, see Wisden et al., 1996; Carlson et al., 1998).

How does this subunit diversity relate to the heterogeneity of channel conductance? The ion selectivity and conductance of GABAAreceptors is determined by the presence of charged residues close to and within the second transmembrane domain (TM2) of each subunit (Smith and Olsen, 1995). To assess the possible influence of different subunits on single-channel conductance, the primary structure of GABAA receptor subunits was compared, and the net charge for the region encompassing TM2 (between the intracellular end of TM1 and the extracellular end of TM3) was calculated for all α, β, γ, and δ subunits [after the approach of Fisher and Macdonald (1997)]. The γ and δ subunits contribute a greater net positive charge (γ1, γ2, δ +4; γ3 +5) to this region than do any of the α or β subunits (+3 and +2, respectively). It has been suggested (Fisher and Macdonald, 1997) that this difference may account for the consistent observation of a higher main conductance state for αβγ or αβδ combinations when compared directly with αβ heterodimers (26–32 pS vs 11–20 pS) (Puia et al., 1990; Verdoorn et al., 1990;Angelotti and Macdonald, 1993; Fisher and Macdonald, 1997; S. Brickley and M. Farrant, unpublished observations). Our single-channel conductance data indicate the presence of at least three different receptor types in granule cells at P7. Although we cannot equate the high-, mid-, and low-conductance channels (28, 17, and 12 pS) with specific subunit combinations, it seems likely that at P7 the high-conductance openings result from receptors composed of α, β, and γ subunits, whereas the lower conductance events result from receptors lacking a γ subunit. The significantly lowerPo values and briefer open periods of the high-conductance clusters further distinguish these receptors from those giving rise to clusters of lower conductance openings.

Not only does the γ subunit influence channel conductance, but it is also essential for allosteric modulation by benzodiazepines (for review, see Barnard et al., 1998). Consistent with the presence of γ-containing receptors, GABA-induced currents in premigratory and postmigratory granule cells (Farrant et al., 1995), as well as those in cultured granule cells (Mathews et al., 1994; Mellor and Randall, 1997), are potentiated by benzodiazepines. Most neurons express γ subunits, and heteromeric assemblies of α, β, and γ subunits are considered to be the most common form of native GABAAreceptor (McKernan and Whiting, 1996). Nevertheless, it is clear that, in expression systems at least, combinations of α and β subunits can form functional receptors (Connolly et al., 1996a,b; Gorrie et al., 1997; Tretter et al., 1997). However, because of evidence for preferential coassembly of α, β, and γ subunits (Angelotti and Macdonald, 1993; Tretter et al., 1997), the possible existence of native receptors formed from α and β subunits has been largely overlooked. Our data, showing the presence of both low- and high-conductance receptors in developing cerebellar granule cells, suggests an ability of neurons to independently assemble either αβ- or αβγ-containing receptors. Moreover, these receptors appear to be targeted to different regions of the neuronal membrane.

Targeting of GABAA receptors

At least three receptor types are present in the extrasynaptic membrane of granule cells, but only a high-conductance type is found at the synapse. The conductance of synaptically activated GABAA receptors was calculated by peak-scaled nonstationary fluctuation analysis and from direct resolution of channel closures in the tail of IPSCs. For several reasons, we believe that the synaptic channel is of a single type. There was a remarkable correspondence between the weighted-mean single-channel conductance obtained with fluctuation analysis and the unitary conductance determined from directly resolved channel openings. Moreover, the parabolic relationship between mean current and variance indicates that there is no difference in the weighted-mean conductance of channels contributing to different phases of the IPSC decay. This was supported by the consistency of step size throughout the IPSC and by the fact that the smallest IPSCs had peak amplitudes that were integer multiples of the unitary step size. It is important to note that a single conductance state does not establish the presence of a single GABAAreceptor population. In studies of recombinant receptors, all αβγ combinations examined so far give rise to similar high-conductance channels. For example, in this study, the substitution of a β3 for a β2 subunit did not significantly alter single-channel conductance. Nevertheless, the high conductance of the synaptic receptors (Table 1) clearly indicates that they contain a γ subunit. This conclusion is supported by the fact that IPSCs at P7 are prolonged by benzodiazepines (Farrant and Brickley, unpublished observation) in a manner similar to that reported for granule cells in slightly older animals (Rossi and Haman, 1998).

Table 1.

Single-channel chord conductance values for synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in internal granule cells at P7

| Extrasynaptic | Synaptic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High conductance | Mid conductance | Low conductance | Nonstationary fluctuation analysis | Direct resolution |

| 27.9 ± 2.7 | 16.7 ± 1.6 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 27.6 ± 1.8 | 26.4 ± 0.2 |

| (n = 224) | (n = 92) | (n = 37) | (n = 10) | (n = 480) |

Conductance values are given in pS (mean ± SEM). Data for extrasynaptic channels were obtained from analysis of individual clusters of openings (n = 21 somatic patches). For each cluster type, the number of clusters is indicated in parentheses. The conductance value from nonstationary fluctuation analysis is from estimates of weighted-mean conductance in 10 cells. The conductance value from direct resolution of synaptic channel events is the mean of all resolvable steps in 234 IPSCs from eight cells.

Potential mechanisms of receptor targeting

It has been known for some time that the γ subunits are concentrated at many GABAA synapses (Somogyi et al., 1996). The most novel aspect of our results is the suggestion that GABAA receptors lacking a γ subunit are specificallyexcluded from the synapse. In this context it is interesting to note that in adult granule cells the γ subunit is found in both synaptic and extrasynaptic membrane, whereas the δ subunit, which is thought to substitute for the γ in some heteromeric assemblies, is found only extrasynaptically (Nusser et al., 1998). Recently, several mechanisms have been identified that may account for the differential targeting of receptors containing a γ subunit. A novel microtubule-associated protein GABARAP (GABAA-receptor-associated protein) has been identified and shown to interact preferentially with the γ2 subunit, linking it to the cytoskeleton and promoting receptor clustering (Wang et al., 1999). The protein gephyrin has also been implicated in the clustering of GABAA receptors at synaptic sites (Craig et al., 1996; Giustetto et al., 1998), and in neurons from mice lacking the γ2 subunit, both GABAA receptor and gephyrin clusters are disrupted (Essrich et al., 1998). Whether either of these interactions accounts for the preferential incorporation of γ-containing receptors at granule cell synapses remains to be determined.

Although differential targeting of receptors is an attractive explanation for our observations, other interpretations of the data need to be considered. Recent studies suggest that the conductance of certain ligand-gated ion channels may be influenced by agonist concentration (Eghbali et al., 1998; Rosenmund et al., 1998). If this were the case, the difference in conductance of extrasynaptic and synaptic GABAA receptors could simply reflect the difference between steady-state activation of receptors in the presence of 50 μm GABA and the activation of synaptic receptors by a brief pulse of transmitter of much higher concentration. We think this is unlikely. Brief application (1 msec) of 1 mm GABA to outside-out patches from internal granule cells (P7) results in the activation of GABAA receptors with a range of conductances similar to those seen in the present steady-state experiments (our unpublished observation). As in the steady-state experiments, most of the openings are of a high-conductance type (∼30 pS), but lower conductance openings are also present. Moreover, channels activated by low micromolar concentrations of GABA also display similar conductances (Kaneda et al., 1995; Amico et al., 1998). Thus, for GABAAreceptors in cerebellar granule cells at least, the concentration of transmitter does not affect single-channel conductance. Because our experiments identify only functional receptors, we cannot of course exclude the possibility that multiple receptor types are present in the postsynaptic membrane, with a specific subset being nonfunctional or “silent” (Lewis et al., 1990; Poisbeau et al., 1997).

Functional consequences of differential receptor localization

Although granule cells receive synaptic input only on their distal dendrites, most of the GABAA receptor subunits are localized to proximal dendritic and somatic membrane (Nusser et al., 1995). The significance of these extrasynaptic GABAAreceptors remains unclear. However, in older animals, extrasynaptic α6β2/3γ2 or α6β2/3δ GABAA receptors may be involved in generating a tonic conductance attributable to their activation after spillover of GABA from the synaptic cleft (Kaneda et al., 1995; Brickley et al., 1996; Tia et al., 1996; Wall and Usowicz, 1997; Nusser et al., 1998; Rossi and Haman, 1998). More speculatively, in immature cells the extrasynaptic receptors could be important in some aspects of the migration and differentiation of cerebellar granule cells. The depolarizing action of GABA in developing cerebellar granule cells (Brickley et al., 1996) could underlie possible trophic roles for this transmitter system that precede its more conventional inhibitory actions (Carlson et al., 1998).

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council. We thank Stephen Traynelis, David Colquhoun, and Ioana Vais for providing software; Christopher Connolly, Bernie McDonald, and Stephen Moss for providing GABAA subunit clones and transfected HEK-293 cells; and Michael Häusser, Zoltan Nusser, Angus Silver, Geoff Swanson, and David Wyllie for comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Mark Farrant, Department of Pharmacology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amico C, Cupello A, Fossati C, Robello M. Involvement of phosphatase activities in the run-down of GABAA receptor function in rat cerebellar granule cells in culture. Neuroscience. 1998;84:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelotti TP, Macdonald RL. Assembly of GABAA receptor subunits: α1β1 and α1β1γ2S subunits produce unique ion channels with dissimilar single-channel properties. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1429–1440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01429.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisti S, Iosif G, Marchesi GF, Strata P. Pharmacological properties of inhibitions in the cerebellar cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1971;14:24–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00234908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borst JG, Lodder JC, Kits KS. Large amplitude variability of GABAergic IPSCs in melanotropes from Xenopus laevis: evidence that quantal size differs between synapses. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:639–655. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brickley SG, Cull-Candy SG, Farrant M. Development of a tonic form of synaptic inhibition in rat cerebellar granule cells resulting from persistent activation of GABAA receptors. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;497:753–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson BX, Elster L, Schousboe A. Pharmacological and functional implications of developmentally-regulated changes in GABAA receptor subunit expression in the cerebellum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;352:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark BA, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. A direct comparison of the single-channel properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:107–116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colquhoun D, Ogden D. Activation of ion channels in the frog end-plate by high concentrations of acetylcholine. J Physiol (Lond) 1988;395:131–159. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun D, Sigworth F. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel recording. Plenum; New York: 1995. pp. 483–587. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connolly CN, Krishek BJ, McDonald BJ, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Assembly and cell surface expression of heteromeric and homomeric γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996a;271:89–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly CN, Wooltorton JR, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Subcellular localization of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors is determined by receptor β subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996b;93:9899–9904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig AM, Banker G, Chang W, McGrath ME, Serpinskaya AS. Clustering of gephyrin at GABAergic but not glutamatergic synapses in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3166–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03166.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKoninck Y, Mody I. Noise analysis of miniature IPSCs in adult rat brain slices: properties and modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor channels. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1318–1335. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eccles JC, Ito M, Szentágothai J. The cerebellum as a neuronal machine. Springer; Berlin: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eghbali M, Curmi JP, Birnir B, Gage PW. Hippocampal GABAA channel conductance increased by diazepam. Nature. 1998;388:71–75. doi: 10.1038/40404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essrich C, Lorez M, Benson JA, Fritschy JM, Lüscher B. Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the γ2 subunit and gephyrin. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:563–571. doi: 10.1038/2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Excitatory amino acid receptor-channels in Purkinje cells in thin cerebellar slices. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;244:179–184. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrant M, Feldmeyer D, Takahashi T, Cull-Candy SG. NMDA-receptor channel diversity in the developing cerebellum. Nature. 1994;368:335–339. doi: 10.1038/368335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrant M, Kaneda M, Cull-Candy SG. Benzodiazepine modulation of GABA-activated currents in granule cells of the rat cerebellum. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;498P:17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JL, Macdonald RL. Single channel properties of recombinant GABAA receptors containing γ2 or δ subtypes expressed with α1 and β3 subtypes in mouse L929 cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;505:283–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.283bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritschy JM, Benke D, Mertens S, Oertel WH, Bachi T, Mohler H. Five subtypes of type A γ-aminobutyric acid receptors identified in neurons by double and triple immunofluorescence staining with subunit-specific antibodies. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6726–6730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritschy JM, Johnson DK, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Independent assembly and subcellular targeting of GABAA receptor subtypes demonstrated in mouse hippocampal and olfactory neurons in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giustetto M, Kirsch J, Fritschy JM, Cantino D, Sassoè-Pognetto M. Localization of the clustering protein gephyrin at GABAergic synapses in the main olfactory bulb of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:231–244. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980601)395:2<231::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorrie GH, Vallis Y, Stephenson A, Whitfield J, Browning B, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Assembly of GABAA receptors composed of α1 and β2 subunits in both cultured neurons and fibroblasts. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6587–6596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamill OP, Bormann J, Sakmann B. Activation of multiple-conductance state chloride channels in spinal neurones by glycine and GABA. Nature. 1983;305:805–808. doi: 10.1038/305805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hámori J, Takács J. Two types of GABA-containing axon terminals in cerebellar glomeruli of cat: an immunogold-EM study. Exp Brain Res. 1989;74:471–479. doi: 10.1007/BF00247349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones A, Korpi ER, McKernan RM, Pelz R, Nusser Z, Mäkelä R, Mellor JR, Pollard S, Bahn S, Stephenson FA, Randall AD, Sieghart W, Somogyi P, Smith AJH, Wisden W. Ligand-gated ion channel subunit partnerships: GABAA receptor α6 subunit gene inactivation inhibits δ subunit expression. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1350–1362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01350.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones MV, Westbrook GL. Desensitized states prolong GABAA channel responses to brief agonist pulses. Neuron. 1995;15:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones MV, Westbrook GL. Shaping of IPSCs by endogenous calcineurin activity. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7626–7633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07626.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneda M, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Whole-cell and single-channel currents activated by GABA and glycine in granule cells of the rat cerebellum. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;485:419–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kilic G, Moran O, Cherubini E. Currents activated by GABA and their modulation by Zn2+ in cerebellar granule cells in culture. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koulen P, Sassoè-Pognetto M, Grünert U, Wässle H. Selective clustering of GABAA and glycine receptors in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2127–2140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02127.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laurie DJ, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. II. Olfactory bulb and cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1063–1076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01063.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis CA, Ahmed Z, Faber DS. Developmental changes in the regulation of glycine-activated Cl- channels of cultured medullary neurons. Dev Brain Res. 1990;51:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90288-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews GC, Bolos-Sy AM, Holland KD, Isenberg KE, Covey DF, Ferrendelli JA, Rothman SM. Developmental alteration in GABAA receptor structure and physiological properties in cultured granule neurons. Neuron. 1994;13:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald BJ, Amato A, Connolly CN, Benke D, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Adjacent phosphorylation sites on GABAA receptor β subunits determine regulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:23–28. doi: 10.1038/223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKernan RM, Whiting PJ. Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meinecke DL, Rakic P. Developmental expression of GABA and subunits of the GABAA receptor complex in an inhibitory synaptic circuit in the rat cerebellum. Dev Brain Res. 1990;55:73–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90107-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellor JR, Randall AD. Frequency-dependent actions of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors in cultured murine cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;503:353–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.353bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newland CF, Colquhoun D, Cull-Candy SG. Single channels activated by high concentrations of GABA in superior cervical ganglion neurones of the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 1991;432:203–233. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nusser Z, Roberts JDB, Baude A, Richards JG, Somogyi P. Relative densities of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors on cerebellar granule cells as determined by a quantitative immunogold method. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2948–2960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02948.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Somogyi P. Differential synaptic localization of two major γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha subunits on hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11939–11944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nusser Z, Cull-Candy S, Farrant M. Differences in synaptic GABAA receptor number underlie variation in GABA mini amplitude. Neuron. 1997;19:697–709. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Segregation of different GABAA receptors to synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes of cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patlak JB. Sodium-channel subconductance levels measured with a new variance-mean analysis. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:413–430. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poisbeau P, Williams SR, Mody I. Silent GABAA synapses during flurazepam withdrawal are region-specific in the hippocampal formation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3467–3475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03467.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puia G, Santi MR, Vicini S, Pritchett DB, Purdy RH, Paul SM, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuron. 1990;4:759–765. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenmund C, Stern-Bach Y, Stevens CF. The tetrameric structure of a glutamate receptor channel. Science. 1998;280:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi DJ, Hamann M. Spillover-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses promoted by high affinity α6 subunit GABAA receptors and glomerular geometry. Neuron. 1998;20:783–795. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakmann B, Patlak J, Neher E. Single acetylcholine-activated channels show burst-kinetics in presence of desensitizing concentrations of agonist. Nature. 1980;286:71–73. doi: 10.1038/286071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silver RA, Traynelis SF, Cull-Candy SG. Rapid-time-course miniature and evoked excitatory currents at cerebellar synapses in situ. Nature. 1992;355:163–166. doi: 10.1038/355163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silver RA, Cull-Candy SG, Takahashi T. Non-NMDA glutamate receptor occupancy and open probability at a rat cerebellar synapse with single and multiple release sites. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;494:231–250. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith GB, Olsen RW. Functional domains of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Somogyi P, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Roberts JD, Sieghart W. The γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor is concentrated in synaptic junctions containing the α1 and β2/3 subunits in hippocampus, cerebellum and globus pallidus. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1425–1444. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tia S, Wang JF, Kotchabhakdi N, Vicini S. Developmental changes of inhibitory synaptic currents in cerebellar granule neurons: role of GABAA receptor α6 subunit. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3630–3640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Traynelis SF, Jaramillo F. Getting the most out of noise in the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Traynelis SF, Silver RA, Cull-Candy SG. Estimated conductance of glutamate receptor channels activated during EPSCs at the cerebellar mossy fiber-granule cell synapse. Neuron. 1993;11:279–289. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90184-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tretter V, Ehya N, Fuchs K, Sieghart W. Stoichiometry and assembly of a recombinant GABAA receptor subtype. J Neurosci. 1997;15:2728–2737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verdoorn TA, Draguhn A, Ymer S, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Functional properties of recombinant rat GABAA receptors depend upon subunit composition. Neuron. 1990;4:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wall MJ, Usowicz MM. Development of action potential-dependent and independent spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated currents in granule cells of postnatal rat cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang H, Bedford FK, Brandon NJ, Moss SJ, Olsen RW. GABAA-receptor-associated protein links GABAA receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 1999;397:69–72. doi: 10.1038/16264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wisden W, Korpi ER, Bahn S. The cerebellum: a model system for studying GABAA receptor diversity. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1139–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zdilar D, Luntz-Leybman V, Frostholm A, Rotter A. Differential expression of GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor β1, β2 and β3 subunit messenger-RNAs in the developing mouse cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1992;326:580–594. doi: 10.1002/cne.903260407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimprich F, Zezula J, Sieghart W, Lassmann H. Immunohistochemical localization of the α1, α2 and α3 subunit of the GABAA receptor in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1991;127:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90910-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]