Abstract

A physiological role for cannabinoids in the CNS is indicated by the presence of endogenous cannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors. However, the cellular mechanisms of cannabinoid actions in the CNS have yet to be fully defined. In the current study, we identified a novel action of cannabinoids to enhance intracellular Ca2+responses in CNS neurons. Acute application of the cannabinoid receptor agonists R(+)-methanandamide, R(+)-WIN, and HU-210 (1–50 nm) dose-dependently enhanced the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ response elicited by stimulation of the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptors (NMDARs) in cerebellar granule neurons. The cannabinoid effect was blocked by the cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716A and the Gi/Go protein inhibitor pertussis toxin but was not mimicked by the inactive cannabinoid analogS(−)-WIN, indicating the involvement of cannabinoid receptors. In current-clamp studies neither R(+)-WIN norR(+)-methanandamide altered the membrane response to NMDA or passive membrane properties of granule neurons, suggesting that NMDARs are not the primary sites of cannabinoid action. Additional Ca2+ imaging studies showed that cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA did not involve N-, P-, or L-type Ca2+ channels but was dependent on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Moreover, the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor antagonist xestospongin C blocked the cannabinoid effect, suggesting that the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals results from enhanced release from IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores. These data suggest that the CNS cannabinoid system could serve a critical modulatory role in CNS neurons through the regulation of intracellular Ca2+signaling.

Keywords: cannabinoid, methanandamide, WIN, HU-210, cerebellum, granule neuron, NMDA, intracellular calcium

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the major psychoactive compound in marijuana (Cannabis sativa), is the prototypic agonist for the newly discovered class of cannabinoid receptors (Martin et al., 1994; Pertwee, 1997). The CB1 subtype of cannabinoid receptors was cloned from the CNS (Matsuda et al., 1990) and found to be highly expressed in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and basal ganglia of the adult rat brain (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992; Matsuda et al., 1993; Tsou et al., 1998), a distribution consistent with many of the psychopharmacological actions of marijuana such as impaired memory, altered time perception, and loss of motor coordination (Adams and Martin, 1996). Moreover, endogenous biochemicals such asN-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol have been isolated from the CNS and found to reproduce many of the behavioral effects of Δ9-THC (Di Marzo, 1998). The presence of neuronal receptors and endogenous ligands indicates that an endogenous cannabinoid system for interneuronal communication exists in the CNS. However, the physiological role of this system and the cellular mechanisms of cannabinoid actions in the CNS have yet to be fully elucidated.

Results from pharmacological studies suggest that cannabinoids produce many of their CNS effects by depressing Ca2+ channel activity (Caulfield and Brown, 1992; Mackie and Hille, 1992; Felder et al., 1993; Mackie et al., 1995; Pan et al., 1996; Twitchell et al., 1997; Shen and Thayer, 1998) or enhancing K+ channel activity (Deadwyler et al., 1993; Henry and Chavkin, 1995; Mackie et al., 1995). Consistent with actions on voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (VSCCs), cannabinoids reduce synaptically evoked intracellular Ca2+signals (Shen et al., 1996) and inhibit presynaptic glutamate release (Shen et al., 1996; Lévénès et al., 1998). Cannabinoid effects on intracellular Ca2+signals such as occurs with inhibition of VSCCs could have important implications for other cellular functions, because Ca2+ is an important intracellular second messenger. However, outside of inhibition of VSCCs, little is known about cannabinoid effects on neuronal Ca2+signaling pathways. An important pathway for Ca2+ entry into CNS neurons is the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptors (NMDARs) (Mori and Mishina, 1995). NMDARs play an important role in synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the CNS, mediate trophic effects of glutamate in the developing nervous system, and help define many aspects of neuronal structure and function during the developmental program. Ca2+ signaling is a critical component of these neuronal functions.

In the current study, we used fura-2 Ca2+imaging to examine the effects of cannabinoids on Ca2+ signals elicited by stimulation of NMDARs in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Ca2+ signaling involving NMDARs is a complex cellular event involving numerous processes, including Ca2+ influx through NMDARs and VSCCs and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Simpson et al., 1995). Our results show that cannabinoids enhance NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals and that enhanced Ca2+ release appears to be the primary mechanism mediating this action of the cannabinoids. These results suggest that in addition to effects on ion channels, cannabinoid regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling may be an important mechanism through which cannabinoids modulate neuronal function in the CNS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cerebellar cultures. Primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons were prepared using a standard enzyme treatment protocol (Trenkner, 1991; Qiu et al., 1995). Briefly, postnatal rat pups (8 d, Sprague Dawley; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with halothane, the were brains removed, and the cerebella were isolated. Tissue was dissociated in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free saline containing trypsin (0.5%) and DNase I (2400 U/ml). The neurons were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in DMEM and F-12 supplemented with 10% horse serum (heat-inactivated), 20 mm KCl, 30 mm glucose, 2 mml-glutamine, and penicillin (20 U/ml)-streptomycin (20 μg/ml). Neurons were plated at 1–4 × 106 cells/ml onto Matrigel-coated cover glass (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA; catalog #NC9351417) in tissue culture dishes. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere for up to 15 d. Serum-free medium (0.5 ml) was added every 7 d. Contamination by astrocytes was minimized by treatment with 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (20 μg/ml) on the first and fourth days after plating.

Modified organotypic cultures of cerebellar neurons were prepared from the cerebella of embryonic day 20 rat pups and maintained in vitro as described previously (Gruol and Franklin, 1987). In brief, cerebellar cortices were minced and triturated without enzymatic treatment in physiological saline and plated on cover glass coated with Matrigel. The plating medium contained minimal essential medium with Earle’s salts and l-glutamine (MEM), 10% horse serum (heat-inactivated), 10% fetal calf serum (heat-inactivated) and 5.0 gm/l d-glucose. Brief treatment with 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (20 μg/ml, days 4–6 in vitro) minimized the growth of non-neuronal neurons. No antibiotics were used. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Acutely isolated cerebellar granule neurons. The method for preparing the acutely isolated granule neurons was similar to that used by Mermelstein et al. (1996). Rat pups (5 d postnatal) were decapitated, and the cerebella were removed. Sagittal slices (350–450 μm) were prepared from the vermis in ice-cold oxygenated artificial CSF containing (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 0.2 CaCl2, 5 MgSO4, and 10 glucose, pH 7.3. The white matter was removed, and the slices were minced in isethionate buffer containing 140 mm sodium isethionate, 2 mm KCl, 4 mm MgCl2,, 23 mmglucose, 15 mm HEPES, 5 μm glutathione, 1 mmN-ω-nitro-l-arginine, and 10 mm kynurenic acid, pH 7.4 (room temperature). The tissue was incubated 45 min (at room temperature) in Earle’s balanced salt solution supplemented with 5 μm glutathione, 1 mmN-ω-nitro-l-arginine, 10 mm kynurenic acid, and 1 mmpyruvate. The tissue was then incubated for 30 min (at 37°C) in 0.1% papain in HBSS supplemented with 5 μmglutathione, 1 mmN-ω-nitro-l-arginine, and 10 mm kynurenic acid. The tissue was washed three times in isethionate buffer and gently triturated. The neurons were plated on coated glass coverslips for experimental use.

Ca2+ imaging. Granule neurons 4–15 din vitro were used for experiments. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured in the somatic region of individual granule neurons using standard microscopic fura-2 digital imaging techniques (Qiu et al., 1995) based on the methods ofGrynkiewicz et al. (1985). In brief, cells were incubated (30 min, room temperature) with the Ca2+-sensitive dye fura-2 AM (1.5 μm) and pluronic F-127 (0.02%) in balanced salt solution (BSS) containing (in mm): 137 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 0.33 Na2HPO4, 2.2 CaCl2, 2.0 MgSO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.3. The neurons were then incubated for 45 min in BSS to allow for cleavage of the AM from the fura-2 AM.

The cover glass with the granule neurons was mounted in a chamber attached to the stage of an inverted microscope equipped for phase-contrast and bright-field optics and fura-2 video imaging. The cultures were bathed in Mg2+-free BSS containing glycine (5 μm), a coagonist for NMDARs. Mg2+ was omitted to relieve Mg2+-dependent block of the NMDAR (Mori and Mishina, 1995). All recordings were made at room temperature (21–23°C).

Live video images of individual neurons were acquired at 3 sec intervals with a SIT-66 video camera (Dage–MTI, Michigan City, IN) at 340 and 380 nm and digitized for real-time display under the control of MicroComputer Imaging Device imaging software (Imaging Research Inc., St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada). Fluorescence ratios (340:380 nm) were converted to intracellular Ca2+concentrations using the following formula: [Ca2+]i =Kd[(R −Rmin)/(Rmax−R)]Fo/Fs, where R is the ratio value,Rmin is the ratio for a Ca2+-free solution,Rmax is the ratio for a saturated Ca2+ solution,Kd = 135 (the dissociation constant for fura-2), Fo is the intensity of a Ca2+-free solution at 380 nm, andFs is the intensity of a saturated Ca2+ solution at 380 nm. Calibration was performed using fura salt (100 μm) in solutions of known Ca2+ concentration (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; kit C-3009). TypicalRmax,Rmin, andFo/Fsvalues were 0.61, 2.85, and 2.5, respectively. Cell calibration methods gave variable results and were not used. In the current study, the intracellular Ca2+ measurements are used to identify relative changes in intracellular Ca2+ attributable to cannabinoid exposure and are not meant to provide information about absolute intracellular Ca2+ levels. Cellular autofluorescence and non-cell-associated background fluorescence (e.g., from the cover glass) were very low; therefore, background subtraction methods to correct for such fluorescence sources were not used.

Experimental paradigm. Granule neurons were stimulated with NMDA, a selective agonist for NMDARs. NMDA was dissolved in the bath saline (i.e., BSS) and applied by brief microperfusion from glass micropipettes (1–3 μm tip diameter) placed near the neurons of interest. The concentration (25–200 μm) and duration (≤1.0 sec) of NMDA application were adjusted under control conditions for each experiment to produce Ca2+signals with a peak amplitude (50–200 nm) that could be easily quantified. The cannabinoid receptor agonists produced similar actions regardless of the dose of NMDA used. Neurons were stimulated with 50 mm K+ in one group of experiments. For these studies, 50 mm KCl was substituted for an equivalent amount of NaCl in BSS and applied by micropipettes as described above. Fast green (0.003%) was included in NMDA and K+ solutions to monitor exposure of neurons to the test agent. Fast green by itself had no effect on neuronal firing, baseline Ca2+ levels, or the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. The time course of dye exposure indicated that the onset of neuronal exposure to the stimulant was relatively fast, occurring during the initial phase of the application period, whereas the clearance of the dye from the neuron (by diffusion) was slower, taking ∼5–10 sec. Bath saline was exchanged between stimulations.

All pharmacological agents other than NMDA and K+ were applied to the cultures by bath replacement. Responses in the presence of cannabinoids were typically made 5–30 min after the initial cannabinoid exposure. Cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists were prepared as stock (10 mm) solutions in DMSO or ethanol and diluted in BSS immediately before use. For the majority of experiments, the bath saline used during control recordings contained an amount of DMSO or ethanol equivalent to that used in the presence of cannabinoid agents. Separate vehicle control experiments showed that DMSO (≤0.005%) or ethanol (≤0.02 mm) did not affect the measurements under study.

Typically, individual Ca2+ levels (resting and the response to NMDA) were measured simultaneously for 15–20 granule neurons within a microscopic field, with three to five microscopic fields measured per condition in each culture dish. Control and cannabinoid-treated neurons were recorded from the same culture dish, although each cell was tested under only one condition. Resting Ca2+ levels were subtracted from amplitude measurements (in response to NMDA) on an individual cell basis to yield peak Ca2+ values. Unless stated otherwise, results were normalized within a culture dish for better comparison of data obtained from different culture sets.

Electrophysiology. Parallel electrophysiological experiments were performed under conditions similar to those used for Ca2+ imaging (see above). Nystatin-patch recordings were made in the somatic region of granule neurons according to methods described previously (Netzeband et al., 1997). Patch pipettes (4–5 mΩ) were filled with a solution containing 6 mm NaCl, 154 mmK+-gluconate, 2 mmMgCl2, 0.5 mmCaCl2, 10 mm HEPES-KOH, 10 mm glucose, 1 mm BAPTA, and 200 μg/ml nystatin, pH 7.3. Stock solutions of nystatin (50 mg/ml DMSO) were prepared daily. Current-clamp recordings were made at the resting potential of the neuron under study using an Axopatch-1C amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). pCLAMP software and the Labmaster interface (Axon Instruments) were used for acquisition and analysis of current-evoked responses. All recordings were monitored on a polygraph and oscilloscope, and selected data were recorded on FM tape (Racal Recorders, Inc., Irvine, CA). Polygraph records were used for manual measurement of NMDA-evoked membrane responses.

Immunohistochemistry. The CB1 receptor-specific antibody was generously provided by Dr. Ken Mackie (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). The antibody has been characterized elsewhere (Twitchell et al., 1997; Tsou et al., 1998). CB1 immunostaining was performed with some modifications according to techniques reported previously (Gruol and Franklin, 1987). In brief, cultures were fixed with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS (100 mm), pH 7.3, for 15 min. Cultures were pretreated for 30 min with PBS containing 0.05% saponin and 10% nonfat dry milk (to block nonspecific staining) and then incubated overnight (4°C) with primary antibody (1:750 dilution) in PBS containing 10% nonfat dry milk and 0.05% BSA. Immunoreactivity was detected the next day by an immunoperoxidase reaction using the materials and procedures provided in the Vectastain Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). No immunoreactivity was detected when staining was performed in the absence of primary antibody.

Analyses. A between-cell comparison was used for determining the effects of cannabinoids on response measurements. For each group of studies, data from at least three individual culture dishes representing two or more culture sets were pooled for summary analysis. Averages are reported as the mean ± SEM, and the number of neurons and/or cultures studied is given. Raw data were analyzed with appropriate parametric tests: paired or unpaired t test or ANOVA. Normalized data were analyzed using the Mann–WhitneyU test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, nonparametric equivalents of the unpaired t test and ANOVA, respectively. In cases in which ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test was used,post hoc analysis for group differences was performed using Scheffé’s F test or Dunn’s test for unequal sample sizes, respectively. Statistical significance was determined at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Materials. Medium, serum, trypsin, and penicillin-streptomycin for use in tissue culture were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). DNase I was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN), and Matrigel was purchased from Becton Dickinson Labware (Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Additional chemicals were purchased from the following companies: fura-2 AM, pluronic F-127, and thapsigargin from Molecular Probes; [3-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)-(−)-11-hydroxy-delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol] (HU-210), 6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX), (S)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG),d-(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (D-AP5), and verapamil from Tocris Neuramin (Ballwin, MO);R(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazin-yl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate [R(+)-WIN] andS(−)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(4-morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazin-yl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate [S(−)-WIN] from Research Biochemicals (RBI, Natick, MA); R(+)-arachidonyl-1′-hydroxy-2′-propylamide [R(+)-methanandamide] from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI) or RBI (Natick, MA); ω-agatoxin IVA, 8-bromo-cAMP, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1-[6-((17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl]-1H- pyrrole-2,5-dione (U-73122), 1-[6-((17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)- trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl]-2,5-pyrrolidine-dione (U-73343), pertussis toxin, Rp-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate triethylamine (Rp-cAMPS), 9-(tetrahydro-2′-furyl)adenine (SQ 22536), and xestospongin C from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); and ω-conotoxin GVIA from Peptides International (Louisville, KY) or Calbiochem.N-(Piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxyamide (SR141716A) was obtained courtesy of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD). CGP55845A was a gift from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). All other chemicals and drugs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Cannabinoids dose-dependently enhance NMDA-elicited intracellular Ca2+ signals

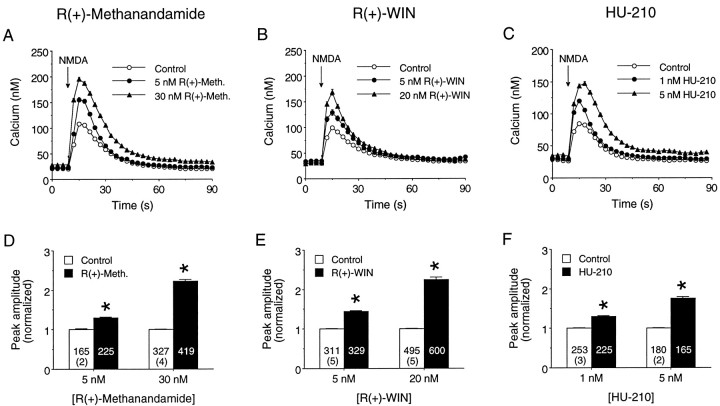

Intracellular Ca2+ was measured in the somatic region of individual granule neurons at 4–15 d in vitro (DIV). The granule neurons showed steady resting Ca2+ levels (see below) before NMDA application (Fig.1A–C). NMDA (25–200 μm) was applied by brief microperfusion (≤1 sec) and elicited a Ca2+ signal in these neurons characterized by an initial relatively rapid rise in intracellular Ca2+ to a peak amplitude of 50–200 nm followed by a slower recovery to baseline Ca2+ levels (Fig.1A–C). Similar application of NMDA in electrophysiological experiments produced depolarizations of 10–20 mV from resting membrane potentials of approximately −70 mV (see below). The peak amplitude of the NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signal (minus the resting Ca2+ level) was used as a relative measure of the size of the Ca2+ response.

Fig. 1.

Cannabinoid receptor agonists enhance Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA. A–C, Effects of acute application of R(+)-methanandamide (A), R(+)-WIN (B), and HU-210 (C) on the intracellular Ca2+ signals elicited by exogenous NMDA application. NMDA (50 or 200 μm; see Materials and Methods) was applied at the arrows by a short (≤1 sec) microperfusion pulse. Graphs depict averaged NMDA-elicited Ca2+ responses for individual fields of granule neurons under control conditions or in the presence of the specified concentration of cannabinoid agonist. Each tracerepresents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ response of 20 granule neurons measured individually in a microscopic field; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in many cases. Different microscopic fields were used for each response, although all results for a particular cannabinoid are from the same culture set.D–F, Mean ± SEM effects ofR(+)-methanandamide (D),R(+)-WIN (E), and HU-210 (F) on the peak amplitude of the intracellular Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA application.Numbers in each bar represent the total number of neurons measured; the values in parenthesesindicate the number of culture sets used for each condition. In this and all other figures resting Ca2+ levels were subtracted from amplitude measurements on an individual cell basis. The peak amplitude of the Ca2+ response in each neuron was normalized to the mean peak control response for the culture and then data from different cultures combined. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, Mann–WhitneyU test). R(+)-Meth,R(+)-methanandamide.

The effect of cannabinoid receptor activation on NMDA-elicited intracellular Ca2+ signals was studied by bath application of cannabinoids. Three cannabinoid receptor agonists were tested: R(+)-methanandamide (an unsaturated fatty acid ethanolamide and a metabolically stable analog of the presumed endogenous CB1 ligand anandamide; Abadji et al., 1994),R(+)-WIN (a cannabimimetic aminoalkylindole), and HU-210 (a tetrahydrocannabinol similar in structure to Δ9-THC). Different populations of neurons were used for the control and cannabinoid conditions. Each cannabinoid was tested on at least five different culture sets, and two doses of each cannabinoid were used. Only a single cannabinoid at one dose was tested per individual culture. Cannabinoid actions on NMDA-elicited intracellular Ca2+ signals in the granule neurons were observed at all culture ages studied (4–15 DIV). However, for the majority of experiments, 6–8 DIV cultures were used.

R(+)-Methanandamide (5 and 30 nm),R(+)-WIN (5 and 20 nm), and HU-210 (1 and 5 nm) all enhanced the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig. 1). The extent of this enhancement showed some variation between culture sets, but the higher dose of each cannabinoid consistently produced a larger enhancement of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal than the lower dose, indicating that cannabinoid modulation was dose-dependent. Cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA was evident within 5–10 min of cannabinoid application (the earliest time point that data were obtained) and could be observed during the entire 30 min period used for data collection. However, after ∼20 min of exposure the effectiveness of the cannabinoid started to decline, possibly because of desensitization (Howlett et al., 1991), inactivation (Garcia et al., 1998), or internalization (Hsieh et al., 1999) of the cannabinoid receptor. This aspect of cannabinoid action was noted but not studied further. The cannabinoids did not alter the general form of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig.1A–C).

Resting Ca2+ levels in the granule neurons were fairly consistent within and between culture sets and typically ranged from 20 to 50 nm. These values are similar to resting Ca2+ levels observed by others in cultured granule neurons (Courtney et al., 1990; Beani et al., 1994). Although the cannabinoids produced small increases or decreases in resting Ca2+ levels in individual cultures, there was no consistent effect between cultures. For example, in one set of experiments resting Ca2+levels averaged 45 ± 4 nm under control conditions and 47 ± 6 nm in the presence of 10 nmR(+)-WIN (p > 0.05, pairedt test; six cultures).

In an additional set of control experiments, we determined whether alterations in synaptically driven events were responsible for the cannabinoid modulation of the NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals. Granule neurons are the only excitatory neurons intrinsic to the cerebellum and use glutamate as a neurotransmitter. The granule neurons constitute >95% of the neurons in culture, although a few GABA-containing neurons are present as well. Therefore, studies were performed in the presence of the AMPA and kainate receptor antagonist NBQX (5 μm) and a GABAA receptor antagonist, either picrotoxin (100 μm; two cultures) or bicuculline (30 μm, three cultures), to block possible excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) inputs to the granule neurons. Results were comparable for studies using R(+)-WIN (5–10 nm; three culture sets) orR(+)-methanandamide (10 nm; two culture sets), so data were pooled. The mean peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (25 or 50 μm) was enhanced in the presence of the cannabinoid agonists to 160 ± 2% of the control value (p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test;n = 356 neurons in control; n = 299 neurons in cannabinoid; five culture sets). This increase was similar to that observed in the absence of receptor antagonists (see Fig. 1). These results indicate that an alteration in synaptic events is unlikely to account for the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals.

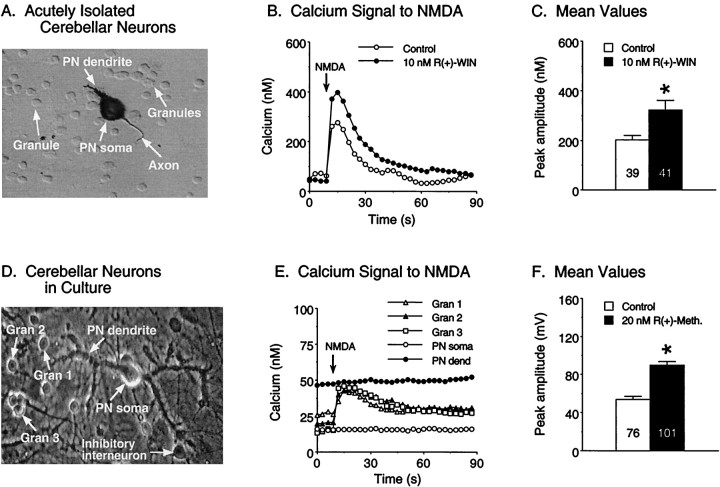

The granule neuron culture system has been extensively used as a model to investigate a variety of neuronal functions. However, questions could arise concerning the potential for the culture environment to alter granule neuron function. To address this issue, we tested the effects of R(+)-WIN on the Ca2+signal to NMDA in granule neurons acutely isolated from rat pups at 5 d postnatal, an age when cannabinoid receptors are known to be expressed in the cerebellum (Romero et al., 1997). NMDA applied to the acutely isolated granule neurons in the same manner as for the cultured granule neurons elicited a Ca2+ signal that was comparable with that observed in the cultured granule neurons (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the Ca2+ signal to NMDA in the acutely isolated granule neurons was potentiated by R(+)-WIN (Fig.2A), consistent with results from the cultured granule neurons.

Fig. 2.

Cannabinoids enhance the Ca2+signal to NMDA in acutely isolated granule neurons and granule neurons in cerebellar culture. A-C, Effect ofR(+)-WIN on the Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA in acutely isolated granule neurons. A, Photomicrograph (Hoffman optics) of granule neurons acutely isolated from a postnatal day 5 rat cerebellum. Also shown in the picture is a Purkinje neuron (PN) showing immunostaining for calbindin, a cellular marker for Purkinje neurons. The emerging apical dendrite and axon of the immature Purkinje neuron are evident.B, Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA in granule neurons under control conditions and in the presence of 10 nmR(+)-WIN. Each traceis from a single granule neuron. NMDA was applied as in Figure 1.C, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA in all granule neurons studied in three different acutely isolated preparations.Numbers in the bars represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. D–F, Effect ofR(+)-methanandamide on the Ca2+signals elicited by NMDA in granule neurons in cerebellar culture.D, Phase-contrast photomicrograph of granule neurons (gran) and a Purkinje neuron (PN) in cerebellar culture. E, Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA under control conditions in the granule neurons and Purkinje neuron depicted in D. Ca2+ signals were measured in both the somatic (PN soma) and dendritic (PN dend) regions of the Purkinje neuron; Purkinje neurons did not respond to the NMDA application. NMDA was applied as in Figure 1.F, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals evoked by NMDA in all granule neurons studied in two culture sets. Numbers in thebars represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney Utest).

Another issue of concern is that the relative lack of normal target neurons for the cultured or acutely isolated granule neurons (e.g., Purkinje neurons) could alter the functional properties of the granule neurons. To address this issue, we tested the cannabinoid sensitivity of granule neurons in modified organotypic cultures of cerebellar neurons that contain all neuronal types present in the cortical region of the cerebellum in vivo and express synaptic connections between granule neurons and their target neurons (Gruol and Franklin, 1987). The cultures were prepared from embryonic rat cerebellum and maintained in vitro for 3 weeks; the neurons are considered mature at this developmental age (Gruol and Franklin, 1987). In these cultures, granule neurons responded to exogenously applied NMDA, whereas nearby Purkinje neurons did not (Fig. 2B), consistent with the known expression of NMDARs (Monyer et al., 1994) and sensitivity to exogenous NMDA (Garthwaite et al., 1987) in these neuronal types in vivo for the ages tested. Ca2+ signals to NMDA in the granule neurons of the modified organotypic cultures were similar to that observed in the granule neuron cultures. Bath application ofR(+)-WIN enhanced the Ca2+signal to NMDA in the granule neurons in the organotypic cultures (Fig.2B), as was observed for granule neurons in the granule neuron cultures. Taken together, these results indicate that cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA represents a physiological response of granule neurons and not a response that is induced by the culture conditions.

Cannabinoid actions on NMDA-induced Ca2+ signals are mediated through a cannabinoid receptor

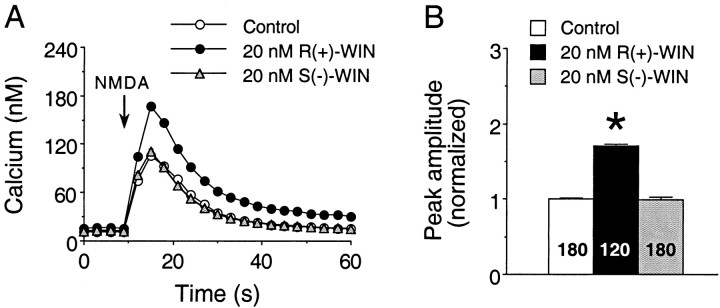

The observation that three structurally distinct cannabinoid receptor agonists [R(+)-methanandamide,R(+)-WIN, and HU-210] augment NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals in a dose-dependent manner provides evidence that these effects are mediated through a cannabinoid receptor. To obtain additional support for receptor involvement in the cannabinoid modulation of NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals, we determined the stereoselectivity of R(+)-WIN actions and tested the ability of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A to block the cannabinoid actions.

In the first set of studies, the inactive cannabinoid enantiomerS(−)-WIN (5–20 nm) was tested on the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals. For comparison, parallel studies involving identical concentrations ofR(+)-WIN were performed on additional cultures from the same culture sets. Typical results are shown in Figure3. Normalized data from three culture sets showed that the mean peak amplitude of the NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals was augmented byR(+)-WIN to 160 ± 2% of the control value [p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test;n = 209 neurons in control; n = 239 neurons in R(+)-WIN]. In contrast, application ofS(−)-WIN to the same culture sets resulted in NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals that had a mean peak amplitude of 108 ± 2% of control [p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test; n = 240 neurons in control; n = 284 neurons in S(−)-WIN]. Although the effect of S(−)-WIN was statistically significant, it was considerably less than that of R(+)-WIN. It is likely that the small effect of S(−)-WIN represents a nonspecific action of the WIN compounds. Overall, these data are consistent with the stereoselectivity of the actions ofR(+)-WIN on the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals.

Fig. 3.

The inactive cannabinoid S(−)-WIN does not mimic the actions of R(+)-WIN on NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals. A, Representative Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA in fields of granule neurons under control, 20 nmR(+)-WIN, and 20 nmS(−)-WIN conditions. NMDA (200 μm) was applied at the arrow by a 1 sec microperfusion pulse. Each trace is from a different microscopic field of neurons and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 20 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in most cases. B, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the NMDA-induced Ca2+ signals elicited by all granule neurons studied in a single experiment. Individual responses were normalized as described in the legend for Figure 1. Results represent data from three culture dishes from the same culture set; two dishes were treated with S(−)-WIN, and one dish was treated with R(+)-WIN. Numbers in thebars represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test followed bypost hoc analysis using Dunn’s test).

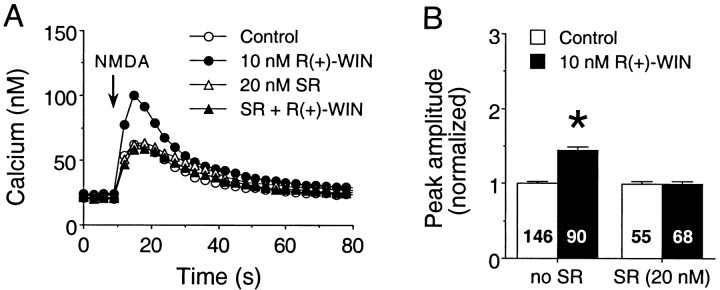

In the second set of experiments, the ability of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A to block the actions of R(+)-WIN was tested. Treatment of cultures with 20 nmSR141716A had no effect on the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA but blocked the modulatory action of 10 nmR(+)-WIN to enhance the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal. Normalized data from two culture sets showed that the mean peak amplitudes of the Ca2+ signals to NMDA were 101 ± 2% of control in the presence of SR141716A and 88 ± 2% of control value in the presence of SR141716A plusR(+)-WIN [p > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test;n = 223 neurons in control; n = 231 neurons in SR141716A; n = 246 neurons in SR141716A +R(+)-WIN]. To demonstrate the effectiveness ofR(+)-WIN, parallel studies were performed on additional cultures from the same culture sets in the absence of SR141716A. In these experiments, R(+)-WIN (10 nm) enhanced the mean peak amplitude of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal to 146 ± 2% of the control value [p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney Utest; n = 252 neurons in control; n = 253 neurons in R(+)-WIN]. Representative results from one culture set are shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

The cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716A blocks the R(+)-WIN-mediated enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. A, Representative Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA (50 μm, 600 msec application at the arrow) in fields of granule neurons under control conditions or in the presence of 10 nmR(+)-WIN, 20 nmSR141716A, or R(+)-WIN plus SR141716A.R(+)-WIN by itself enhanced the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, and these effects were blocked by SR141716A. Each response is from a different microscopic field and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 20 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in most cases. Data are from two different dishes from the same culture set; one culture was untreated, and the second culture was treated with SR141716A. B, Mean ± SEM peak amplitudes of the NMDA-induced Ca2+ signals elicited by all granule neurons studied in a single experiment. Individual responses were normalized as described in the legend for Figure 1. Numbers in the bars represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test followed by post hoc analysis using Dunn’s test). SR, SR141716A.

Gi/Go proteins are involved in the cannabinoid modulation of NMDA-mediated Ca2+signals

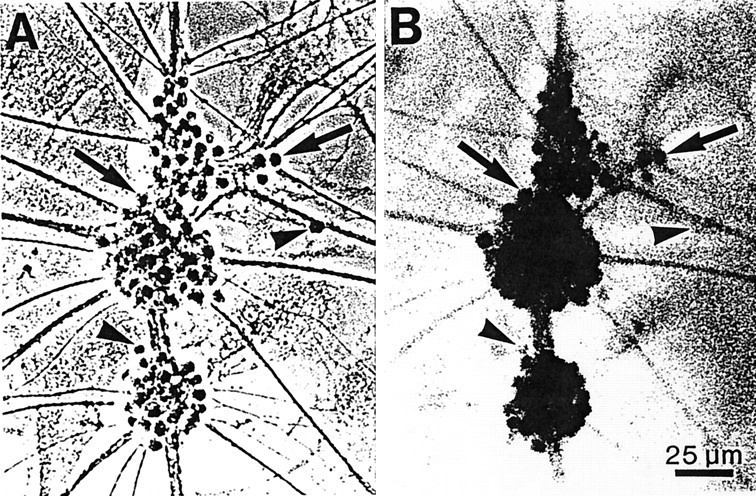

Cerebellar granule neurons in vivo express both mRNA (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992) and protein (Tsou et al., 1998) for CB1, a receptor that has been characterized to couple negatively to adenylyl cyclase via Gi/Goproteins (Martin et al., 1994). We found that the CB1 phenotype is retained in culture as demonstrated by intense immunostaining of cultured granule neurons with an antibody to the CB1 receptor (Fig.5). Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether a G-protein was involved in the cannabinoid regulation of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals in our studies.

Fig. 5.

Granule neurons in culture express CB1 receptors. Photomicrographs are shown of granule neurons (12 DIV) immunostained with an antibody to the CB1 receptor and visualized using phase-contrast (A) or bright-field (B) optics. Antibody binding was detected using a peroxidase reaction and is seen best under Hoffman optics (B). The majority of granule neuron somata were immunoreactive for CB1 receptors (arrows). However, a few granule neurons showed little or no CB1 receptor immunostaining (arrowheads). Only background levels of immunostaining were observed in the astrocyte layer underlying the granule neurons. Photomicrographs are of the same microscopic field.

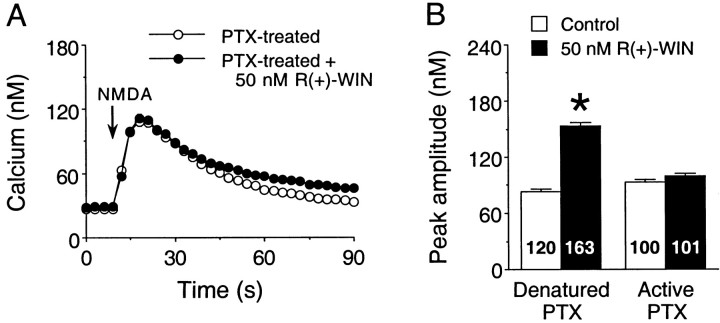

Inactivation of G-proteins by pertussis toxin was used to test for the involvement of Gi/Go in the cannabinoid modulation of NMDA Ca2+signals. Overnight treatment with pertussis toxin (200 ng/ml), an inhibitor of Gi/Goproteins, blocked the R(+)-WIN (10–50 nm) enhancement of the Ca2+ response to NMDA compared with neurons treated with heat-denatured (25 min, 100°C) pertussis toxin. Representative results from one culture set are shown in Figure6. Overall (two culture sets),R(+)-WIN increased the mean peak amplitude of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal to 170 ± 3% of the control value in cultures treated with denatured pertussis toxin [p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test;n = 214 neurons in control; n = 268 neurons in R(+)-WIN]. The modulatory effect ofR(+)-WIN observed in cultures treated with denatured pertussis toxin was similar to effects observed under control conditions (compare Figs. 1, 3, 4), indicating that the denatured toxin did not alter the modulatory actions of the cannabinoid. In contrast to the denatured toxin, the modulatory actions of R(+)-WIN were completely blocked by active pertussis toxin. In pertussis toxin-treated cultures (two culture sets), the mean peak amplitude of the NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signal in the presence of R(+)-WIN was 95 ± 2% of the control value in pertussis toxin alone [p > 0.05, Mann–WhitneyU test; n = 187 neurons in control;n = 186 neurons in R(+)-WIN]. Treatment of cultures with pertussis toxin (100 ng/ml; 5 d) was also found to inhibit the actions of 20 nmR(+)-methanandamide (data not shown). The overnight and 5 d treatments with pertussis toxin did not appear to alter the morphological features of the neurons or other aspects of the cultures. In addition, in electrophysiological experiments, pertussis toxin did not affect the amplitude of the membrane depolarization to NMDA (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

The Gi/Go inhibitor pertussis toxin blocks the R(+)-WIN-mediated enhancement of Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA. A, Representative Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA (200 μm, 1 sec application at the arrows) in fields of granule neurons in cultures treated overnight with active pertussis toxin (PTX; 200 ng/ml). Responses to NMDA are shown for both control and R(+)-WIN (50 nm) conditions. Each response is from a different microscopic field and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 20 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in many cases. B, Mean ± SEM peak amplitudes of the Ca2+ signals to NMDA in control and R(+)-WIN-treated granule neurons exposed to denatured or active pertussis toxin. The denatured pertussis toxin did not block the R(+)-WIN-induced enhancement of the peak amplitude of the NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signal, whereas treatment with active pertussis toxin blocked the modulatory actions of R(+)-WIN. Results are from a single experiment. Numbers in each bar represent the total number of neurons measured for that condition. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, unpairedt test).

As a positive control for the effectiveness of pertussis toxin in blocking Gi/Go, the membrane response of cerebellar granule neurons to the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen was tested under current-clamp conditions on cultures from the same culture sets used for the Ca2+ imaging studies. The GABAB receptor in these neurons is known to be coupled to potassium channel through a pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/Go protein (Slesinger et al., 1997). Cultures were treated overnight with either active or denatured pertussis toxin (200 ng/ml). The response to baclofen (100 μm; 1 sec application) was measured at a holding potential of −100 mV. Baclofen elicited a membrane depolarization of 5 ± 1 mV (n = 4 neurons) in neurons treated with denatured pertussis toxin. In contrast, the response to baclofen was completely abolished by active pertussis toxin (five of five neurons).

Cannabinoids do not alter membrane properties or the membrane response to NMDA

Cannabinoid receptor activation could enhance NMDA-mediated Ca2+ signals in a number of ways. One mechanism would be to alter resting membrane potential or the input resistance of the neurons in such a way as to enhance Ca2+ influx mediated by NMDAR channels or VSCCs activated by the membrane depolarization to NMDA. To investigate this possibility, we used current-clamp recordings (nystatin perforated patch method) from the granule neurons to test the effects of cannabinoids on electrophysiological measures. There was no effect ofR(+)-methanandamide (30 nm) orR(+)-WIN (30 nm) on resting membrane potential or input resistance of the granule neurons. Summarized results from these experiments are shown in Table1. These results suggest that the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals is not caused by changes in the passive membrane properties of the granule neurons.

Table 1.

Summary of cannabinoid actions on membrane properties and the membrane response to NMDA

| Control [mean ± SEM (n)] | 30 nmR(+)-Methanandamide [mean ± SEM (n)] | Control [mean ± SEM (n)] | 30 nmR(+)-WIN [mean ± SEM (n)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane properties | ||||

| Resting potential (mV) | −73 ± 1 (27) | −74 ± 1 (21) | −74 ± 1 (20) | −75 ± 1 (21) |

| Rin-hyperpol (GΩ) | 1.88 ± 0.16 (26) | 1.94 ± 0.11 (19) | 1.10 ± 0.13 (20) | 1.27 ± 0.16 (21) |

| Rin-depol (GΩ) | 1.44 ± 0.12 (26) | 1.39 ± 0.11 (19) | 0.81 ± 0.11 (20) | 1.07 ± 0.15 (21) |

| Peak response to NMDA | ||||

| 25 μm NMDA (mV) | 14 ± 3 (11) | 16 ± 2 (17) | 11 ± 3 (10) | 13 ± 3 (10) |

| 200 μm NMDA (mV) | 20 ± 2 (19) | 20 ± 2 (14) | 17 ± 2 (20) | 16 ± 2 (20) |

There was no difference between the control and cannabinoid groups for any of the parameters measured (p > 0.05, unpaired t test). Rin-hyperpol and Rin-depol are the input resistance calculated for the cells for membrane potentials hyperpolarized (Rin-hyperpol) or depolarized (Rin-depol) to resting membrane potential. Values for input resistance are taken from the slopes of input–output curves of the sustained voltage responses elicited by constant current (500 msec duration) hyperpolarizing (Rin-hyperpol) or depolarizing (Rin-depol) current injections. For Rin-depol, input resistance was determined only over the membrane potential range at which NMDA-elicited responses were observed (i.e., resting membrane potential to approximately −40 mV).

Another mechanism by which cannabinoids could alter NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals would be to directly alter the function of NMDARs, perhaps through changes in the phosphorylation state of the NMDAR, such that the membrane depolarization is increased. To address this possibility, we measured the amplitude of the membrane depolarization to NMDA under control conditions or in the presence ofR(+)-methanandamide or R(+)-WIN. The electrophysiological experiments were run in parallel with the Ca2+ imaging studies. Under control conditions, NMDA (25 or 200 μm; 1 sec application) elicited a rapid dose-dependent membrane depolarization followed by a slow recovery to the resting membrane potential. Neither R(+)-methanandamide (30 nm) nor R(+)-WIN (20–30 nm) altered the peak of the NMDA-induced depolarization (Fig. 7, Table 1). Higher concentrations of R(+)-WIN (300–500 nm) were also tested without significant effect on the peak of the NMDA-induced depolarization, resting membrane potential, or input resistance (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Cannabinoids enhance the calcium signal to NMDA without effects on the membrane response. A,B, Comparison of the membrane response (A) and Ca2+ signal (B) to NMDA in granule neurons under control conditions and in the presence of 20 μmR(+)-WIN. NMDA (200 μm) was applied at thearrows by a 1 sec microperfusion pulse. The four responses are from four different neurons at 6 DIV. The resting membrane potentials of the control and R(+)-WIN-treated neurons in the top panels were −74 and −77 mV, respectively.

Involvement of VSCCs and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in cannabinoid augmentation of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA

The absence of a cannabinoid action on the NMDA-evoked membrane response suggests that cannabinoid modulation of intracellular Ca2+ signal to NMDA is not attributable to effects of cannabinoids or cannabinoid receptor activation directed at the NMDAR itself. Activation of NMDARs in granule neurons increases intracellular Ca2+ through several pathways, including Ca2+ influx through NMDAR-channels, Ca2+ influx through VSCCs activated by the membrane depolarization to NMDA, and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Qiu et al., 1995; Qiu et al., 1998). Thus, cannabinoids could influence the Ca2+ signals to NMDA by actions on other pathways such as Ca2+influx through VSCCs activated by the membrane depolarization to NMDA or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Several types of experiments were performed to determine whether these pathways contributed to the cannabinoid-induced enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA.

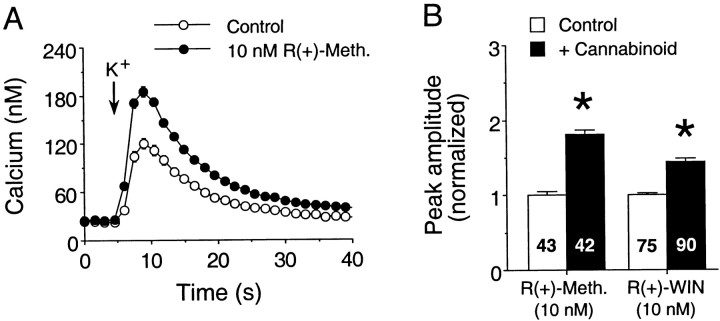

In the first series of experiments we examined the effect of cannabinoids on K+ depolarization, a stimulation paradigm known to evoke Ca2+influx through VSCCs and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in the cultured granule neurons (Qiu et al., 1995; Qiu et al., 1998). Granule neurons were stimulated with 50 mmK+ (see Materials and Methods) to produce a Ca2+ signal of similar magnitude to that produced by NMDA. In most experiments, antagonists for AMPA receptors (5 μm NBQX), NMDARs (50 μmd-APV), GABAA receptors (30 μm bicuculline or 100 μm picrotoxin), or GABAB receptors (1 μm CGP55845A) were included in the bath saline. In electrophysiological experiments, similar application of 50 mmK+ produced depolarizations of 30–40 mV from resting membrane potentials of approximately −70 mV.

Both R(+)-methanandamide and R(+)-WIN enhanced the K+-evoked Ca2+ signals. As for the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals, cannabinoids produced a similar enhancement of Ca2+ signals elicited by K+ regardless of the presence or absence of glutamate and GABA receptor antagonists. Results from typical experiments involving R(+)-methanandamide andR(+)-WIN are summarized in Figure8. Overall (data from five culture sets), K+ (50 mm) evoked an intracellular Ca2+ signal with a mean peak amplitude of 66 ± 2 nm (n = 358 neurons) under control conditions. In the presence ofR(+)-methanandamide (10 nm), the normalized mean peak amplitude of K+-elicited Ca2+ signals was enhanced to 150 ± 3% of the control value [p < 0.05, Mann–WhitneyU test; n = 131 neurons in control;n = 132 neurons in R(+)-methanandamide; three culture sets] Similarly, R(+)-WIN (10 nm) augmented the normalized peak amplitude of K+-evoked Ca2+ signals to 143 ± 3% of control values [p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test;n = 178 neurons in control; n = 180 neurons in R(+)-WIN; two culture sets].

Fig. 8.

Cannabinoids enhance Ca2+signals in response to K+ depolarization.A, Representative Ca2+ signals elicited by K+ stimulation (50 mm, 800 msec application at the arrows) in fields of granule neurons under control conditions or in the presence of 10 nmR(+)-methanandamide. Each response is from a different microscopic field and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 15 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in many cases. B, Mean ± SEM peak amplitudes of the Ca2+ signals to K+ in control and cannabinoid-treated neurons. Individual responses were normalized as described in the legend for Figure 1. Results for each cannabinoid are from a single culture set. Numbers in eachbar represent the total number of neurons measured for that condition. *Significant difference from control (p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney Utest). R(+)-Meth,R(+)-methanandamide.

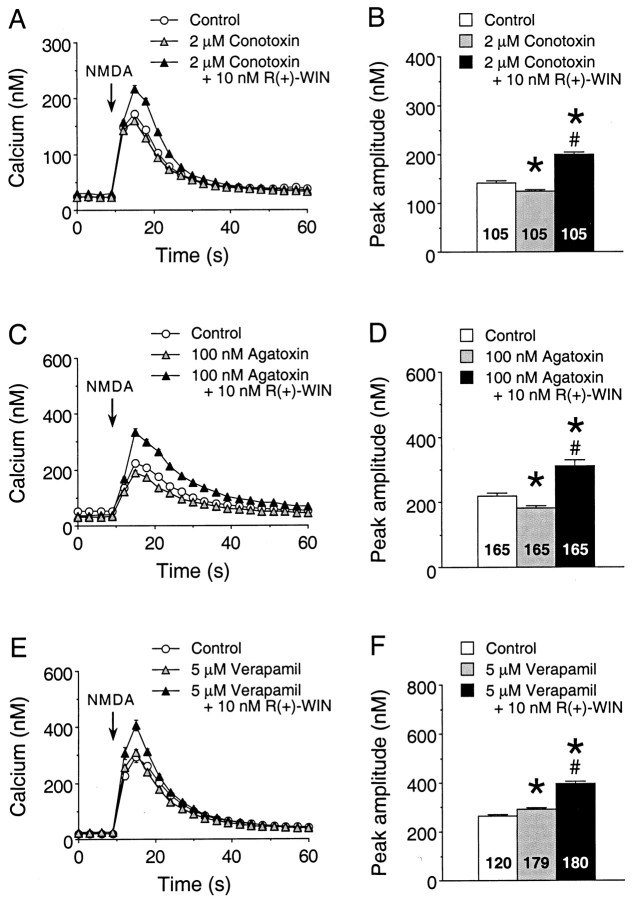

The ability of cannabinoids to enhance the K+-evoked Ca2+ signals is consistent with an effect of cannabinoids on VSCCs or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores triggered by the Ca2+ influx. Cannabinoids are known to inhibit VSCCs, and this regulation appears to be selective for the N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (Mackie and Hille, 1992; Pan et al., 1996; Twitchell et al., 1997). To determine whether cannabinoid-sensitive VSCCs are involved in cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, we tested the ability of the N-type Ca2+channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA (2 μm) to block the effect of R(+)-WIN on the Ca2+signal to NMDA. ω-Conotoxin GVIA produced a small depression of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA under baseline control conditions (Fig. 9A), consistent with our previous studies showing that VSCCs make a small contribution to the Ca2+ signal to NMDA at the culture ages used for the cannabinoid studies (Qiu et al., 1998). The presence of ω-conotoxin GVIA did not block theR(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, indicating that N-type VSCCs were not involved in the effect of R(+)-WIN on the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig.9A). Similar results were obtained with the P-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-agatoxin IVA (Fig. 9B) and the L-type Ca2+channel blockers verapamil (Fig. 9C) and calcicludine (results not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that N-, P-, and L-type VSCCs are not involved in the effect ofR(+)-WIN on the Ca2+ signal to NMDA.

Fig. 9.

Voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels are not involved in cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. A,B, Representative Ca2+ signals (A) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (B) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons under control conditions, in the presence of the N-type Ca2+ channel antagonist ω-conotoxin GVIA (2 μm) and in the presence of ω-conotoxin GVIA plus 10 nmR(+)-WIN. NMDA (50 μm) was applied at the arrow by a 400 msec microperfusion pulse. Each trace in A is from a different microscopic field of neurons in the same culture dish and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 15 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in many cases. The mean values inB are from all granule neurons studied in two culture sets. C, D, Representative Ca2+ signals (C) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (D) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons in studies using the P-type Ca2+ channel antagonist ω-agatoxin IVA. Results are from two culture sets; studies were performed similarly to those in A and B.E, F, Representative Ca2+ signals (E) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (F) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons in studies using the L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist verapamil. Results are from two culture sets; studies were performed similarly to those in A and B. Numbersin the bargraphs (B,D, F) represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from control; #significant difference compared with the presence of the respective Ca2+ channel antagonist (p < 0.05, ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using Scheffé’s Ftest).

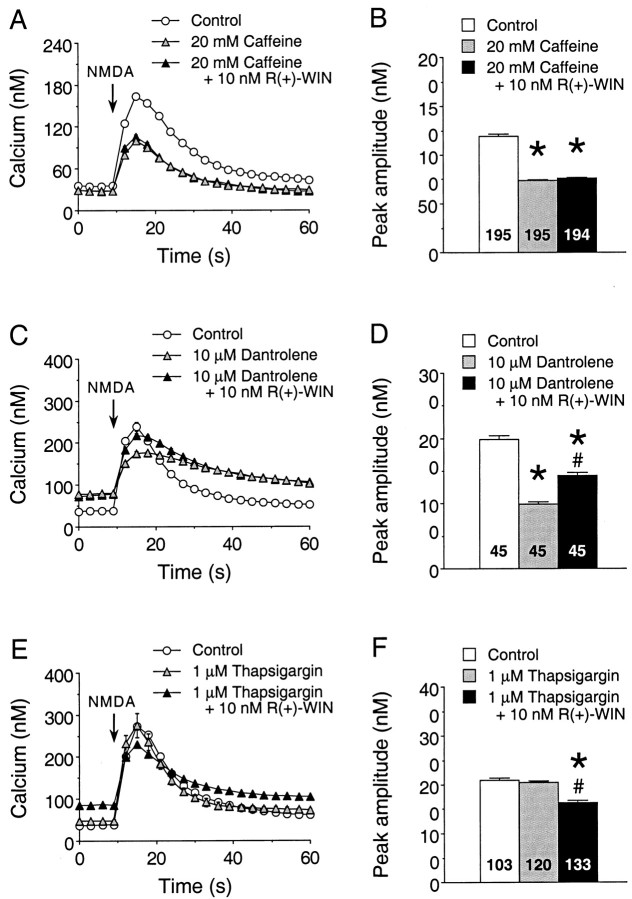

Ca2+ influx through NMDARs triggers Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. To determine whether cannabinoids alter this aspect of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, we tested the effects of several pharmacological agents that alter Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, including caffeine, thapsigargin, and dantrolene. R(+)-WIN (10 nm) was used for all of these studies. Caffeine is known to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores controlled by the ryanodine receptor and can block release from stores controlled by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (Simpson et al., 1995). Treatment of the granule neurons with caffeine (20 mm, 30 min) significantly reduced the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, consistent with a contribution of Ca2+release from intracellular stores to the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig.10A). Moreover, caffeine treatment blocked the R(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. Dantrolene selectively blocks release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores controlled by the ryanodine receptor, which mediates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (Simpson et al., 1995). Treatment of the granule neurons with dantrolene (10 μm, 30 min) reduced the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig.10B), as was observed for caffeine (Fig.10A). However, dantrolene did not block theR(+)-WIN-induced enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig.10B), suggesting that stores controlled by the ryanodine receptor are not involved in cannabinoid regulation of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. Thapsigargin is a Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor (Simpson et al., 1995) and will prevent Ca2+ uptake into stores. If the stores are leaky, thapsigargin treatment will result in depletion of Ca2+ from the stores. Treatment of the granule neurons with thapsigargin (1 μm, 30 min) did not alter the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. However, thapsigargin blocked the R(+)-WIN-mediated enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA and revealed a cannabinoid-induced inhibition (Fig. 10C), perhaps because of R(+)-WIN-mediated depression of VSCCs. Taken together, these data indicate that Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores is involved in the cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+signal to NMDA.

Fig. 10.

Involvement of Ca2+ stores in the cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. A, B, Representative Ca2+ signals (A) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (B) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons under control conditions, in the presence of the caffeine (20 mm) and in the presence of caffeine plus 10 nmR(+)-WIN. NMDA (50 μm) was applied at thearrow by a 400 msec microperfusion pulse. Each trace inA is from a different microscopic field of neurons in the same culture dish and represents the mean ± SEM Ca2+ signal for 15 granule neurons measured individually; error bars are smaller than the corresponding symbol in many cases. The mean values in B are from all granule neurons studied in four culture sets. C,D, Representative Ca2+ signals (C) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (D) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons in studies using dantrolene (10 μm). Results are representative data from one culture set; similar results were obtained in an additional three culture sets. Studies were performed similarly to those in A andB. E, F, Representative Ca2+ signals (E) and the mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals (F) evoked by NMDA in granule neurons in studies using thapsigargin (1 μm). Results are from two culture sets; studies were performed similarly to those in A andB. Numbers in the bar graphs (B, D,F) represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from control;#significant difference compared with the presence of the respective pharmacological agent (p < 0.05, ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using Scheffé’s F test).

Involvement of the IP3-controlled stores in cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA

The data above suggest that intracellular Ca2+ stores are the target of cannabinoid modulation to enhance NMDA-evoked Ca2+signals. However, dantrolene did not block the cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, indicating that ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores (i.e., the stores involved in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release) are not involved with the cannabinoid effect. This suggests that IP3-gated Ca2+ stores may be involved in the effects of cannabinoids on granule neurons. To examine this possibility, we tested the IP3 receptor antagonist xestospongin C on the cannabinoid modulation of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals. Bath application of xestospongin C (1 μm) blocked the R(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA (Fig. 11A), supporting the involvement of IP3-gated Ca2+ stores in the cannabinoid modulation.

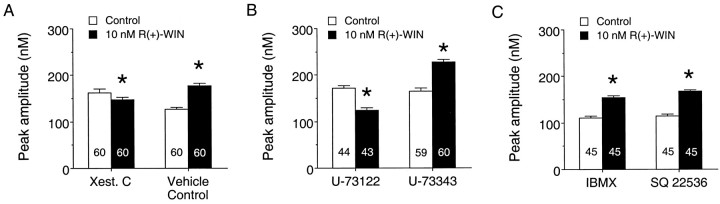

Fig. 11.

IP3-gated stores and phospholipase C contribute to the cannabinoid enhancement of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal. A, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA before and after application of 10 nmR(+)-WIN in cultures treated with the IP3receptor antagonist xestospongin C (1 μm) or the vehicle control (DMSO). Xestospongin C dramatically reduced theR(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+signal to NMDA. Results are from a single culture set; similar results were obtained in an additional three culture sets. B, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA before and after application of 10 nmR(+)-WIN in cultures treated with the phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 (2 μm) or its inactive analog U-73343 (2 μm). The R(+)-WIN enhancement of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal was blocked by U-73122. Results are from a single culture set; similar results were obtained in an additional two culture sets. C, Mean ± SEM peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals elicited by NMDA before and after application of 10 nmR(+)-WIN in cultures treated with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX (200 μm) or the adenylyl cyclase inhibitor SQ 22536 (200 μm). Neither agent blocked theR(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+signal to NMDA. Each set of results is from a single culture set; similar results were obtained in an additional four culture sets for IBMX and two culture sets for SQ 22536. Numbers in thebars represent the number of neurons measured for each condition. *Significant difference from the respective control condition (p < 0.05, Mann–WhitneyU test).

Ca2+ release from IP3-gated stores is commonly associated with Gq-coupled receptors that activate phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, an enzyme that hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate into IP3 and diacylglycerol. Although cannabinoid receptors are not known to be coupled to Gq, the βγ subunit of Gi/Go can activate phospholipase C (Exton, 1996), providing a pathway by which cannabinoids could modulate Ca2+ release from IP3-gated Ca2+stores in the granule neurons. To evaluate this possibility, we tested the effect of the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 on the cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. Bath application of U-73122 (1–2 μm) blocked the action of R(+)-WIN on the Ca2+ signal to NMDA, whereas the inactive analog U-73343 (1–2 μm) was without effect (Fig.11B), indicating that the phospholipase C transduction pathway is involved in the cannabinoid enhancement of Ca2+ signals. Together, the ability of both U-73122 and xestospongin C to block the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals indicates the involvement of the phospholipase C–IP3transduction pathway in this modulatory action of the cannabinoids.

We also examined whether the adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–protein kinase A signal cascade downstream from Gi/Go was involved in mediating the cannabinoid enhancement of intracellular Ca2+ signals, because cannabinoids are known to inhibit this transduction pathway through a pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/Goprotein (Martin et al., 1994; Pertwee, 1997). To address this question, we tested several agents known to act on components of the adenylyl cyclase cascade on the R(+)-WIN (10 μm) enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. In the first series of experiments, we examined agents that inhibit steps in the adenylyl cyclase cascade. Pre-exposure of the neurons to either the adenylyl cyclase inhibitor SQ 22536 (200 μm; Fig.11C) or the protein kinase A inhibitor Rp-cAMPS (200 μm; data not shown) did not block theR(+)-WIN enhancement of the Ca2+ signal to NMDA. In the second series of experiments, we tested agents that increase cAMP levels. Bath application of IBMX (200 μm; Fig.11C), an inhibitor of the phosphodiesterase that inactivates cAMP, or 8-bromo-cAMP (200 μm; data not shown), a membrane-permeable analog of cAMP, did not block theR(+)-WIN enhancement of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal. Thus, in contrast to our findings with the phospholipase C antagonist, pharmacological agents that interact with the adenylyl cyclase cascade did not block the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, we identified a novel action of cannabinoids in CNS neurons, namely that acute exposure to cannabinoid receptor agonists enhances the intracellular Ca2+signal produced by NMDA in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. A similar effect of cannabinoids was observed in acutely dissociated cerebellar granule neurons. This action of cannabinoids appears to be mediated through the brain cannabinoid receptor (CB1) for several reasons. First, the effects on the NMDA-mediated Ca2+ signal were produced by nanomolar concentrations and in a dose-dependent manner by three chemically distinct cannabinoids: R(+)-methanandamide,R(+)-WIN, and HU-210. In addition, the cannabinoid effects were stereoselective for R(+)-WIN versus the inactive analogS(−)-WIN, and the cannabinoid actions were blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A. Moreover, the block of cannabinoid action by the Gi/Go inhibitor pertussis toxin further indicates the involvement of a cannabinoid receptor as has been described for other actions of cannabinoids (Pertwee, 1997).

Activation of NMDARs in granule neurons increases intracellular Ca2+ through several pathways including Ca2+ influx through NMDAR channels, Ca2+ influx through VSCCs activated by the membrane depolarization to NMDA, and Ca2+release from intracellular stores (Qiu et al., 1995; Qiu et al., 1998). Thus, cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+signal to NMDA could result from cannabinoid modulation of one or more of these sites. However, our data suggest that the cannabinoid effect does not involve actions on NMDARs. First, the cannabinoids did not alter the membrane depolarization to NMDA in electrophysiological studies. Moreover, the cannabinoids augmented the Ca2+ signals elicited by K+ stimulation, indicating that the cannabinoid enhancement of Ca2+ signals is independent of NMDA receptor activation. In addition, it appears unlikely that VSCCs are involved in the cannabinoid effect. All studies to date have shown that cannabinoids reduce Ca2+ currents (Caulfield and Brown, 1992;Mackie and Hille, 1992; Felder et al., 1993; Mackie et al., 1995; Pan et al., 1996; Twitchell et al., 1997; Shen and Thayer, 1998), an effect that would be expected to reduce Ca2+signals. Our current demonstration that N-, P-, and L-type Ca2+ channel antagonists did not prevent the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals provides further evidence that Ca2+ channels do not play a prominent role in this action of cannabinoids.

In contrast to the above findings, caffeine and thapsigargin blocked the cannabinoid enhancement of the NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signal, suggesting that Ca2+ release from intracellular stores contributes to the cannabinoid effect. CNS neurons typically express two types of intracellular Ca2+ stores, those gated by ryanodine receptors and those gated by IP3 receptors (Simpson et al., 1995). We found that the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals was blocked in the presence of the IP3 receptor antagonist xestospongin C, whereas the cannabinoid modulation was unaffected by the ryanodine receptor antagonist dantrolene. Furthermore, we found that the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 blocked the cannabinoid enhancement of the Ca2+ signals to NMDA. Activation of phospholipase C generates the intracellular messenger IP3 leading to Ca2+release from IP3-gated Ca2+ stores (Bezprozvanny and Ehrlich, 1995). Thus, our results with xestospongin C and U-73122 suggest that cannabinoids modulate NMDA-evoked Ca2+signals in the granule neurons by enhancing Ca2+ release from IP3-gated stores and that this effect involves a phospholipase C-sensitive mechanism.

Studies by others are consistent with an action of cannabinoids on Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. For example, Δ9-THC elicited Ca2+ release from thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ stores in DDT1MF-2 smooth muscle cells (Filipeanu et al., 1997), a cell type that does not express VSCCs. In those studies, the cannabinoid effect on Ca2+ release was sensitive to blockade by SR141716A, indicating the involvement of the CB1 receptor. In another group of studies, the CB1 receptor ligandsR(+)-WIN, 2-arachidonoylglycerol, Δ9-THC, and anandamide induced elevations in intracellular Ca2+ in neuroblastoma (NG108–15) cells via an SR141716A-sensitive cannabinoid receptor (Sugiura et al., 1996, 1997), an effect that was partially attributable to release of Ca2+ from stores (Sugiura et al., 1996). Interestingly, the cannabinoid-evoked Ca2+ signals in the neuroblastoma cells were also sensitive to blockade by the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 (Sugiura et al., 1997), suggesting that the cannabinoid effect involved IP3-gated Ca2+ stores as observed in our studies. Release of Ca2+ from IP3-regulated stores is known to be modulated by intracellular Ca2+ levels (Bezprozvanny and Ehrlich, 1995). Thus, Ca2+ influx through NMDARs or VSCCs activated by membrane depolarization could interact with cannabinoid regulation of IP3-controlled Ca2+stores, resulting in greater Ca2+ release during NMDA or K+ stimulations.

A large number of in vitro studies have shown that cannabinoids inhibit basal, forskolin-stimulated, or hormone-stimulated cAMP accumulation in brain membrane preparations, cultured neurons, and cell lines expressing the CB1 receptor (Martin et al., 1994; Pertwee, 1997). In general, these actions of the cannabinoids are sensitive to blockade by pertussis toxin, suggesting that cannabinoid receptors couple to Gi/Go. In cerebellar membranes prepared from rat whole cerebellum or cultured granule neurons, several cannabinoids have been found to inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity, GTPase activity, and basal and forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in a pertussis toxin-sensitive manner (Pacheco et al., 1991, 1993, 1994; Childers et al., 1994). Our finding that cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals is blocked by pertussis toxin is consistent with this mode of action. However, pharmacological agents that interact with the adenylyl cyclase transduction pathway did not block the cannabinoid effect in our studies. In fact, our studies suggest the involvement of phospholipase C, a pathway typically associated with Gq (Exton, 1996). This apparent discrepancy may reflect activation of phospholipase C through an alternative pathway.

Studies performed in expression systems have shown that βγ subunits of Gi/Go proteins activate phospholipase C (Exton, 1996), suggesting that Gi/Go-coupled receptors such as the cannabinoid receptors could enhance Ca2+ release from IP3-gated Ca2+stores by stimulating the production of IP3 by phospholipase C. Other Gi/Go-protein-coupled receptors have been shown to induce intracellular Ca2+ release from IP3-gated Ca2+stores. Most notably, opiate-evoked increases in intracellular Ca2+ in NG108-15 cells are sensitive to blockade by the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 and depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin (Jin et al., 1994).

In a recent study, Hampson et al. (1998) found that Δ9-THC and anandamide (0.1–1 μm) depressed NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals measured spectrophotometrically in rat brain cerebellar and cortical slices. This cannabinoid action was attributed to decreased P-type Ca2+ channel activity via cannabinoid receptor activation because the effects were blocked by SR141716A, pertussis toxin, and the P-type Ca2+channel antagonist ω-agatoxin IVA. In another study, CB1 receptor ligands [CP55,940, R(+)-WIN, anandamide] were reported to reduce Ca2+ signals evoked by bath application of K+ in cultured granule neurons studied with microfluorimetry, an effect also attributed to cannabinoid regulation of VSCCs (Nogueron et al., 1998). These results are in agreement with studies showing that cannabinoids inhibit N- and P-type Ca2+ currents (Caulfield and Brown, 1992; Mackie and Hille, 1992; Felder et al., 1993; Mackie et al., 1995;Pan et al., 1996; Twitchell et al., 1997; Shen and Thayer, 1998). These inhibitory effects were not evident in our studies under normal conditions, perhaps because of a stronger contribution of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores to the Ca2+ signal to NMDA and K+ under the conditions of our experiments in which the stimulants were applied only briefly. In contrast, in studies in which a depressive action of cannabinoids was observed, longer-duration bath application of the NMDA and K+ was used (Hampson et al., 1998;Nogueron et al., 1998).

Although the inhibitory effect of cannabinoids on intracellular Ca2+ levels was not evident in our studies under normal conditions, a cannabinoid depression of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals was unmasked under conditions in which the cannabinoid enhancement of NMDA-evoked Ca2+ signals was blocked (e.g., in the presence of thapsigargin, U-73122, or xestospongin C). Thus, cannabinoids may increase or decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels depending on the physiological conditions. For example, the inhibitory effects of cannabinoids on Ca2+ signaling may be more prominent under conditions of strong stimulation that result in a high level of VSCC activity. In contrast, cannabinoid enhancement of Ca2+ release from stores may be more evident during periods of low stimulation, during which Ca2+ release from stores may make a larger contribution than VSCCs to the overall Ca2+ signal. In addition, our results may be more applicable to the young developmental age of the neurons used in our studies or to regulatory mechanisms involved in the control of somatic Ca2+ signaling. Interestingly, cannabinoids do not regulate L-type Ca2+channels, a VSCC type that is prominent in the somatic region of CNS neurons (Hell et al., 1993), the cellular region measured in our studies.

Taken together, our studies show that intracellular Ca2+ signaling is another important neuronal function that is regulated by cannabinoids. Ca2+ is an important intracellular second messenger that controls the activity of numerous enzymes (e.g., protein kinase C, MAP kinase, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase) important for a variety of cellular processes, including growth and gene transcription. Thus, our data further support a neuromodulatory role of the endogenous cannabinoid system in CNS neuronal function.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DA10187 to D.L.G. We are grateful to Dr. Ken Mackie (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) for the gift of the CB1 receptor antibody that was developed with support from National Institutes of Health Grants DA08934 and DA00286. We thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse for SR141716A and Novartis for CGP55845A. We thank Dr. Gilles Martin for helpful suggestions concerning the acutely isolated preparation, Jodilyn Caguioa for the preparation of cultures, Chandra Gullette and Carol Trotter for technical assistance, and Floriska Chizer for secretarial assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Donna L. Gruol, Department of Neuropharmacology, CVN 11, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abadji V, Lin S, Taha G, Griffin G, Stevenson LA, Pertwee RG, Makriyannis A. R-Methanandamide: a chiral novel anandamide possessing higher potency and metabolic stability. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1889–1893. doi: 10.1021/jm00038a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams IB, Martin BR. Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction. 1996;91:1585–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beani L, Tomasini C, Govoni BM, Bianchi C. Fluorimetric determination of electrically evoked increase in intracellular calcium in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;51:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bezprozvanny I, Ehrlich BE. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor. J Membr Biol. 1995;145:205–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00232713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caulfield MP, Brown DA. Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit Ca current in NG108–15 neuroblastoma cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:231–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Childers SR, Sexton T, Roy MB. Effects of anandamide on cannabinoid receptors in rat brain membranes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:711–715. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney MJ, Lambert JJ, Nicholls DG. The interactions between plasma membrane depolarization and glutamate receptor activation in the regulation of cytoplasmic free calcium in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3873–3879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03873.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Bennett BA, Edwards TA, Mu J, Pacheco MA, Ward SJ, Childers SR. Cannabinoids modulate potassium current in cultured hippocampal neurons. Receptors Channels. 1993;1:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Marzo V. “Endocannabinoids” and other fatty acid derivatives with cannabimimetic properties: biochemistry and possible physiopathological relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1392:153–175. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Exton JH. Regulation of phosphoinositide phospholipases by hormones, neurotransmitters, and other agonists linked to G proteins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:481–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felder CC, Briley EM, Axelrod J, Simpson JT, Mackie K, Devane WA. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabimimetic eicosanoid, binds to the cloned human cannabinoid receptor and stimulates receptor-mediated signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7656–7660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipeanu CM, de Zeeuw D, Nelemans SA. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol activates [Ca2+]i increases partly sensitive to capacitative store refilling. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;336:R1–R3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia DE, Brown S, Hille B, Mackie K. Protein kinase C disrupts cannabinoid actions by phosphorylation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2834–2841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02834.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garthwaite G, Yamini B, Jr, Garthwaite J. Selective loss of Purkinje and granule cell responsiveness to N-methyl-d-aspartate in rat cerebellum during development. Dev Brain Res. 1987;36:288–292. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruol DL, Franklin CL. Morphological and physiological differentiation of Purkinje neurons in cultures of rat cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1271–1293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-05-01271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampson AJ, Bornheim LM, Scanziani M, Yost CS, Gray AT, Hansen BM, Leonoudakis DJ, Bickler PE. Dual effects of anandamide on NMDA receptor-mediated responses and neurotransmission. J Neurochem. 1998;70:671–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hell JW, Westenbroek RE, Warner C, Ahlijanian MK, Prystay W, Gilbert MM, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Identification and differential subcellular localization of the neuronal class C and class D L-type calcium channel α1 subunits. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:949–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry DJ, Chavkin C. Activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK1) by co-expressed rat brain cannabinoid receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci Lett. 1995;186:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howlett AC, Champion-Dorow TM, McMahon LL, Westlake TM. The cannabinoid receptor: biochemical and cellular properties in neuroblastoma cells. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:565–569. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh C, Brown S, Derleth C, Mackie K. Internalization and recycling of the CB1 receptor. J Neurochem. 1999;73:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin W, Lee NM, Loh HH, Thayer SA. Opioids mobilize calcium from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive stores in NG108–15 cells. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1920–1929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01920.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lévénès C, Daniel H, Soubrié P, Crépel F. Cannabinoids decrease excitatory synaptic transmission and impair long-term depression in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;510:867–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.867bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackie K, Hille B. Cannabinoids inhibit N-type calcium channels in neuroblastoma-glioma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3825–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackie K, Lai Y, Westenbroek R, Mitchel R. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in AtT20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6552–6561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen J-J. Distribution of neuronal cannabinoid receptor in the adult rat brain: a comparative receptor binding radioautography and in situ hybridization histochemistry. Neuroscience. 1992;48:655–668. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90409-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin BR, Welch SP, Abood ME. Progress toward understanding the cannabinoid receptor and its second messenger systems. Adv Pharmacol. 1994;25:341–397. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda LA, Bonner TI, Lolait SJ. Localization of cannabinoid receptor mRNA in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1993;327:535–550. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mermelstein PG, Becker JB, Surmeier DJ. Estradiol reduces calcium currents in rat neostriatal neurons via a membrane receptor. J Neurosci. 1996;16:595–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00595.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori H, Mishina M. Structure and function of the NMDA receptor channel. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1219–1237. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Netzeband JG, Parsons KL, Sweeney DD, Gruol DL. Metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists alter neuronal excitability and Ca2+ levels via the phospholipase C transduction pathway in cultured Purkinje neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:63–75. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]