Abstract

Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) release is regulated by both glucocorticoids and androgens; however, the precise interactions are unclear. We have controlled circulating corticosterone (B) and testosterone (T) by adrenalectomy (ADX) ± B replacement and gonadectomy (GDX) ± T replacement, comparing these to sham-operated groups. We hoped to reveal how and where these neuroendocrine systems interact to affect resting and stress-induced ACTH secretion.

ADX responses. In gonadal-intact rats, ADX increased corticotropin-releasing factor (CRH) and vasopressin (AVP) mRNA in hypothalamic parvocellular paraventricular nuclei (PVN) and ACTH in pituitary and plasma. B restored these toward normal. GDX blocked the increase in AVP but not CRH mRNA and reduced plasma, but not pituitary ACTH in ADX rats. GDX+T restored increased AVP mRNA in ADX rats, although plasma ACTH remained decreased.

Stress responses. Restraint-induced ACTH responses were elevated in ADX gonadally intact rats, and B reduced these toward normal. GDX in adrenal-intact and ADX+B rats increased ACTH responses. Without B, T did not affect ACTH; together with B, T restored ACTH responses to normal. The magnitude of ACTH responses to stress was paralleled by similar effects on the number of c-fos staining neurons in the hypophysiotropic PVN.

We conclude that gonadal regulation of ACTH responses to ADX is determined by T dependent effects on AVP biosynthesis, whereas CRH biosynthesis is B-dependent. Stress-induced ACTH release is not explained by B and T interactions at the PVN, but is determined by B- and T-dependent changes in drive to PVN motorneurons.

Keywords: corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), arginine vasopressin (AVP), paraventricular nucleus, c-fos, adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), restraint, adrenalectomy, gonadectomy

Considerable cross-talk exists between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and gonadal (HPG) neuroendocrine systems. Stress-induced activation of the HPA axis disrupts reproductive function and behavior, whereas the HPG axis, in turn, exerts considerable effects on basal and stress-induced HPA activity. This is readily illustrated by gender differences in basal and stimulated adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and glucocorticoid [corticosterone (B) in the rat and cortisol in humans and nonhuman primates] release which is higher in females (for review, see Patchev and Almeida 1988; Handa et al., 1994; Young, 1995).

Existing evidence suggests that gonadal influences on pituitary responses to stress are exerted centrally, on the two principle ACTH cosecretagogues in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). This is reflected by inhibitory and stimulatory effects of testosterone (T) and estrogen, respectively, on CRH and AVP synthesis and release (Watts and Swanson, 1989; Bohler et al., 1990;Viau and Meaney, 1991, 1996; Bingaman et al., 1994). Both direct and indirect (transynaptic) gonadal influences on CRH and AVP expression in the PVH have been suggested (Viau and Meaney, 1996). However, considering the power with which basal and stimulated ACTH release are regulated by circulating glucocorticoids (for review, see in Dallman et al., 1993), it is difficult to determine whether sex steroid actions on HPA activity are direct or indirect, perhaps mediated by alterations in glucocorticoid negative feedback mechanisms. Moreover, central to this problem is that manipulation of one neuroendocrine system is not without effects on the other. Both adrenalectomy (ADX) and dexamethasone (DEX; a synthetic glucocorticoid) administration have been shown to decrease circulating T levels (Lescoat et al., 1984;Urban et al., 1991). Conversely, gonadectomy (GDX) has been shown to disrupt the normal daily rhythm in circulating glucocorticoids (Smith and Norman, 1987). Thus, many of the documented inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on CRH and AVP mRNA expression and ACTH release assumed to be independent of the gonadal axis could be mediated by secondary effects on gonadal steroid release, and vice versa. This potential is illustrated by evidence that DEX inhibition of AVP expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial amygdala is mediated by the secondary suppression of plasma T levels (Urban et al., 1991). Moreover, combined GDX–ADX exert effects on CRH and glucocorticoid receptor mRNA expression distinct from ADX alone (Patchev and Almeida, 1996).

Whereas shared inhibitory characteristics of B and T regulation on HPA function are perhaps suggestive, at least in males, of potential overlap in their signaling pathways controlling ACTH release, the central basis for this remains undefined. Without direct, within experiment, comparison of the effects of GDX and ADX with and without appropriate hormone replacement, the nature of the interaction between the gonadal and adrenal endocrine systems at the level of the PVN remains difficult to interpret. In the present study we manipulated both the adrenal and gonadal endocrine systems simultaneously in the male rat to unmask how T and B regulate basal and stress-induced HPA function. The results show that ADX and B dominate CRH mRNA in the PVN and pituitary ACTH synthesis, whereas GDX and T act primarily on AVP mRNA and ACTH secretory responses to ADX. In contrast, the magnitude of the plasma ACTH response to stress is determined by interactive effects of B and T at the level of stimulatory input or drive to the PVN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Bantin-Kingman, Fremont, CA) weighing 200–300 gm at arrival, were used in all experiments. Animals were group housed (three per cage) under controlled temperature and lighting conditions (12 hr light/dark cycle; lights on at 6:30 A.M.), with food and water available ad libitum. All testing was performed during the light phase of the cycle between 10:00 A.M. and 12:00 P.M., sampling one animal per cage per day. Experimental protocols were approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Animal Research.

Treatment. To make proper comparisons between the effects of GDX and ADX, with and without specific hormone replacement on basal and stress-related HPA function, male rats were divided into nine groups (six animals per group) representing sham endocrinectomy, INTACT.INTACT; gonadal intact, adrenalectomized animals, with or without corticosterone (B) replacement: INTACT.ADX+B, INTACT.ADX; adrenal intact, gonadectomized animals with or without testosterone (T) replacement: GDX.INTACT, GDX+T.INTACT, or combined endocrinectomy, with or without T or B replacement: GDX+T.ADX+B, GDX+T.ADX, GDX.ADX+B, and GDX.ADX animals (see Table1 for design).

Table 1.

B and T replacement

| HPG.HPA | T (ng/ml)1-a | B (μg/dL)1-a | Thymus (mg/100 g BW)1-b |

|---|---|---|---|

| INT.INT | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 164 ± 12 |

| INT.ADX | 0.9 ± 0.1* | 1-c | 227 ± 9* |

| INT.ADX+B | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 156 ± 9 |

| GDX.INT | 1-c | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 248 ± 6** |

| GDX.ADX | 1-c | 1-c | 269 ± 14** |

| GDX.ADX+B | 1-c | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 229 ± 8* |

| GDX+T.INT | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 141 ± 8 |

| GDX+T.ADX | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 1-c | 156 ± 10 |

| GDX+T.ADX+B | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 147 ± 11 |

n = 15 per group; basal and prestress samples from experiments 1 and 2–3, respectively.

n = 6 per group; experiment 1.

Below detection.

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 versus INT.INT, INT.ADX+B, and GDX+T values.

Bilateral GDX and ADX surgeries were performed using a rodent cocktail of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine (77:1.5:1.5 mg/ml, respectively; 1 ml/kg i.p.). Testosterone replacement was performed at the same time using two subcutaneous SILASTIC capsules (2.5 cm length; 0.062 inner diameter, 0.125 outer diameter) filled with crystalline testosterone designed to provide T levels comparable to the physiological range seen in gonadal-intact adult males (Viau and Meaney, 1996). Corticosterone (B) replacement was performed at the same time using subcutaneous 100 mg pellets (40% B w/w, 60% cholesterol) designed to mimic plasma B levels achieved over the diurnal cycle in adrenal-intact animals (Akana et al., 1988; Viau et al., 1993). Sham endocrinectomy surgeries, in which the gland was not removed) were performed under anesthesia using cholesterol-filled SILASTIC capsules and 100% cholesterol pellets, where appropriate. Basal and stress testing were performed within 2 weeks of surgery and hormone replacement, during which time animals were handled daily.

Experiment 1: basal ACTH responses. Two weeks after surgery, animals were killed by decapitation. Blood samples were collected into ice-chilled EDTA-treated tubes, centrifuged at 3000 ×g for 10 min, and stored at −20°C until assayed for verification of B and T replacement levels, as well as basal ACTH responses. Pituitaries were also removed, quickly washed in ice-chilled RIA buffer (see below) and stored at −20°C until assayed for ACTH content.

Experiment 2: stress ACTH responses. In a separate study, animals were subjected to 30 min of restraint stress. Blood samples were obtained via the tail vein immediately after removal from the home cage (time 0), and at 15 and 30 min during restraint. After collecting the final (30 min) blood sample, animals were removed from the restrainer and returned to their home cages. Thirty minutes after the termination of stress, animals were anesthetized with 35% chloral hydrate (500 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused via the ascending aorta with physiological saline and 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 9.5. Brains were then post-fixed for 5 hr and cryoprotected overnight with 10% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Multiple series of frozen coronal sections throughout the length of the hypothalamus were collected and stored at −20°C in cryoprotectant (30% ethylene glycol and 20% glycerol in 0.5 m phosphate buffer) until processing.

Experiment 3: stress Fos responses. An additional study was performed under conditions better suited for characterizing restraint-sensitive, Fos-responding neurons in the PVN of rats, free from repeated blood sampling. In this case, rats were anesthetized for perfusion either immediately after removal from the home cage or 30 min after the termination of restraint. This poststress interval was chosen on the basis of our earlier time course studies, in which the amplitude of ACTH responses was most reliably associated with PVN Fos-ir profiles gathered 30 min after restraint (Viau and Sawchenko, 1997; Bhatnagar and Dallman, 1998). Brains were processed, as described above, and stored until immunohistochemical (Fos-IR) and hybridization (AVP mRNA) analyses.

Radioimmunoassays. Plasma T (25 μl) was measured using the RIA kit of ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, CA) with [125I]T as tracer. The T antibody (liquid phase) cross-reacts 100% with T, slightly with 5a-DHT (3.40%), 5a-androstane-3β, 17β-diol (2.2%), and 11-oxotestosterone (2%), but does not cross-react with progesterone, estrogen, or the glucocorticoids (all <0.01%). The detection limit of the assay was 0.1 ng/ml.

Plasma B (5 μl) was measured using the RIA kit of ICN Biomedicals with [125I]B as tracer. The B antibody cross-reacts 100% with B, slightly with desoxycorticosterone (0.34%), testosterone, and cortisol (0.10%), but does not cross-react with the progestins or estrogens (<0.01%). The detection limit of the assay was 0.2 μg/dl.

Plasma ACTH levels were determined by RIA as previously described (Viau et al., 1993; Akana and Dallman, 1997). Briefly, plasma (intact, 50 μl; ADX, 12.5 μl) was first incubated overnight at 4°C with a specific ACTH antiserum (Dr. W. C. Engeland, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) at a final dilution of 1:120,000. The ACTH antibody cross-reacts 100% with ACTH1–39, ACTH 1–18, and ACTH 1–24, but not with ACTH1–16, β-endorphin, a- and β-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or a- and β-lipotropin (all <1%). After an additional 24 hr incubation with [125I]ACTH trace (5000 cpm/tube; Incstar, Stillwater, MN), precipitation serum (Peninusula Laboratories, Belmont, CA) was added, and bound peptide was obtained by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 45 min. The detection limit of the assay was 10 pg/ml.

Pituitary ACTH content was measured by RIA in tissue first homogenized in 0.1 N HCl, and then diluted 1:2500 in RIA buffer. A separate aliquot of the pituitary homogenate was taken for the determination of protein concentrations using the method of Bradford (1976) and commercial dye reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Pituitary ACTH stores are expressed as nanograms per mimlligram of protein.

Fos immunohistochemistry. Fos-immunoreactivity (Fos-IR) was detected using a conventional avidin–biotin–immunoperoxidase (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) procedure (Sawchenko et al., 1990) to localize a primary antiserum (0.04 μg/ml working concentration) raised against the N-terminal portion of the human Fos protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), as previously described (Choi et al., 1998; Li and Sawchenko, 1998). The Fos antibody does not cross-react with Fos B, Fra-1, or Fra-2. Fos-IR profiles in different compartments of the PVH were counted using a Leitz optical system coupled to Macintosh-driven, NIH Image software. Profile counts, taken at regularly spaced (120 μm) intervals, were determined over the extent of the cell group (two to three sections), and corrected for double-counting error using the method of Abercrombie (1946). Discrete localization of Fos profiles within the PVH was defined by redirected sampling of Nissl staining patterns aligned to bright-field images. Based on cell size, orientation, and density criteria, the medial parvocellular (mp) neurosecretory portion of the PVH was defined once having identified the adjacent boundaries of the posterior magnocellular, periventricular, and lateral and dorsal parvocellular parts (Swanson and Kuypers, 1980; Swanson and Simmons, 1989). Fos responses to stress were determined by subtracting the group means of the number of Fos-IR profiles displayed during stress from those encountered under basal conditions.

In situ hybridization. Hybridization histochemical localization was performed using a 35S-labeled antisense cRNA probe transcribed from a full-length (1.2 kb) cDNA-encoding CRH mRNA (Dr. K. Mayo, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL), and a33P-labeled antisense cRNA probe transcribed from a 230 bp cDNA fragment encoding the vasopressin-specific 3′ end (exon C) of AVP (Dr. D Richter, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany). Techniques for riboprobe synthesis, hybridization, and autoradiographic localization of mRNA signal were adapted according to Simmons et al. (1989) and Chan et al. (1993). Briefly, free-floating sections were first rinsed in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, to remove cryoprotectant, then mounted and vacuum-dried on glass slides overnight. After post-fixation with 10% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, sections were digested in proteinase K (10 mg/ml, 37°C), acetylated for 10 min (2.5 mm acetic anhydride, 0.1 m triethanolamine, pH 8.0), rapidly dehydrated in ascending ethanol concentrations (50–100%), and then vacuum-dried. Radionucleotide cRNA probes were used at concentrations approximating 107 cpm/ml in a solution of 50% formamide, 0.3m NaCl, 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mmEDTA, 0.05% tRNA, and 10 mm dithiothreitol, 1× Denhardt’s soloution, and 10% dextran sulfate, and applied to individual slides containing six sections through the extent of the PVN of each animal, verified from Nissl staining patterns of adjacent sections. Slides were coverslipped, and then incubated overnight at 60°C, after which the coverslips were removed, and the sections were washed three times in 4× SSC (0.15 m NaCl, 15 mm citric acid, pH 7.0) at room temperature, treated with ribonuclease A (20 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C, desalted in descending SSC concentrations (2–0.1× SSC), washed in 0.1× SSC for 30 min at 70°C, and dehydrated in ascending ethanol concentrations. Sections hybridized with the 35S-labeled CRH and33P-labeled cRNAs were then exposed to x-ray film (β-max, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 24 and 6 hr, respectively, defatted in xylenes, and subsequently coated with Kodak (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) NTB2 liquid autoradiographic emulsion, and exposed at 4°C in the dark with desiccant, for 10 d and 36 hr, respectively, determined by the strength of signal on the x-ray film. Slides were developed with Kodak D-19 for 3.5 min at 14°C, briefly rinsed in distilled water (14°C) for 15 sec, fixed in Kodak fixer for 6.5 min at 14°C, and then washed in running water for 45 min at room temperature. Semiquantitative densitometric analysis of the relative levels of CRH and AVP mRNAs was performed using Macintosh-driven NIH Image software (version 1.61) within the medial parvocellular subdivision of the PVH by redirected sampling of dark-field autoradiographic images aligned to corresponding Nissl-stained sections. Given the presence of two functionally distinct subpopulations of AVP-expressing and AVP-deficient CRH neurosecretory neurons showing distinct dorsal and ventral patterns of distribution and sensitivities to B (Whitnall, 1988), examination of AVP expression levels in ADX animals was further extended with respect to the dorsal and ventral components of the PVN. This was achieved by simple spatial division of the mp at its dorsoventral midextent.

Statistical analysis. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVAs where appropriate. ACTH responses to stress were analyzed using two-way and three-way repeated measures ANOVA with time being the repeated measure. Post hoc analysis was performed by Scheffé’s test for multiple pairwise comparisons. ANOVA results are shown in Table 2. Post hoc findings are discussed in Results.

Table 2.

ANOVA results

| Basal variable | Plasma ACTH | Pituitary ACTH | CRH | AVP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonadal | ||||

| p | <0.0001 | 0.239 | 0.484 | 0.001 |

| F (df) | 46.5 (2,45) | 1.5 (2,45) | 0.7 (2,45) | 8.0 (2,45) |

| Adrenal | ||||

| p | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| F (df) | 115.3 (2,45) | 25.2 (2,45) | 23.7 (2,45) | 20.6 (2,45) |

| Interaction | ||||

| p | <0.0001 | 0.622 | 0.332 | 0.011 |

| F (df) | 46.5 (4,45) | 1.5 (4,45) | 0.7 (4,45) | 8.0 (4,45) |

| Stress variable | Plasma ACTH | Delta ACTH | Fos-IR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gonadal | |||

| p | 0.625 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| F (df) | 0.5 (2,45) | 7.9 (2,45) | 28.9 (2,18) |

| Adrenal | |||

| p | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| F (df) | 115.3 (2,45) | 25.2 (2,45) | 23.7 (2,18) |

| Interaction | |||

| p | <0.0001 | 0.038 | 0.002 |

| F (df) | 7.7 (4,45) | 2.7 (4,45) | 6.1 (4,18) |

| Time | |||

| p | <0.0001 | ||

| F (df) | 138.4 (2,90) | ||

| Gonadal × time | |||

| p | <0.0001 | ||

| F (df) | 10.1 (4,90) | ||

| Adrenal × time | |||

| p | <0.0001 | ||

| F (df) | 16.4 (4,90) | ||

| Interaction | |||

| p | 0.0005 | ||

| F (df) | 3.9 (8,90) |

RESULTS

Plasma B and T replacement

The 40% B pellets provided plasma B levels (4–5 μg/dl) comparable to the mean achieved over the diurnal cycle (Dallman et al., 1987), which normalized basal plasma ACTH levels (Table 1; Fig.1, top). Moreover, this concentration range of B replacement sustains glucocorticoid (in addition to mineralocorticoid) receptor occupancy, as shown by the effects of ADX and B replacement on the thymus gland, a glucocorticoid target devoid of mineralocorticoid receptors (Table 1). GDX animals replaced with SILASTIC T implants showed circulating T levels comparable to adrenal-intact and ADX+B-replaced animals only. Note that ADX caused a significant decrease in plasma T levels (p < 0.05) that was reversed by B replacement. There is clearly a gonadal influence on thymic weight in ADX ± B animals.

Fig. 1.

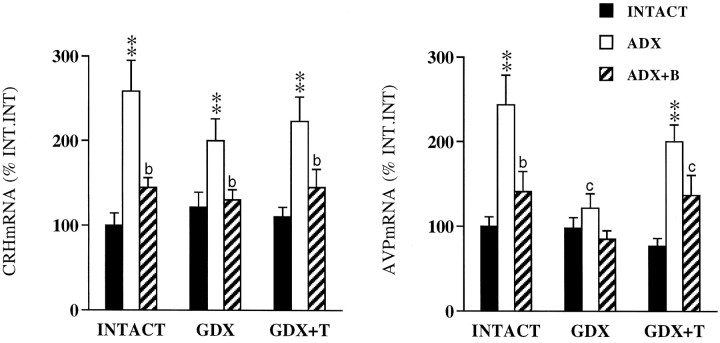

Mean ± SEM plasma (top) and pituitary (bottom) ACTH levels in adrenal-intact, ADX, and ADX+B rats as a function of gonadal status (n = 6 per group). **p < 0.01 versus INTACT; †p < 0.01 versus INTACT. ADX,ap < 0.01;bp > 0.05 versus ADX.

ACTH responses to ADX

Basal ACTH levels differed significantly as a function of gonadal and adrenal status (p < 0.001), and there was a significant interactive effect (p < 0.001). ADX produced marked increases in plasma ACTH levels (p < 0.01) in all groups of animals (Fig. 1,top). However, relative to INTACT.ADX animals, ACTH responses to ADX were significantly lower (p < 0.01) in GDX and GDX+T animals. While B replacement effectively reversed ACTH hypersecretion in gonadal-intact animals, this was less evident in GDX and GDX+T animals.

Pituitary ACTH stores differed significantly in response to ADX ± B (p < 0.001), with no significant effects of gonadal status (p = 0.239) or an interactive (p = 0.622) effect. Thus, despite the inhibitory effects of GDX ± T on plasma ACTH responses to ADX, pituitary ACTH content (Fig. 1, bottom) was elevated (p < 0.01) in all groups of ADX animals regardless of T status. This indicates that gonadal regulation of ACTH release operates above the pituitary level. B replacement reversed the effects of ADX on pituitary ACTH stores in all animals. Thus, whereas ADX ± B regulation of pituitary ACTH synthesis occurs independently of gonadal status, ACTH secretory responses to ADX are responsive to gonadal influences.

CRH and AVP mRNA responses to ADX

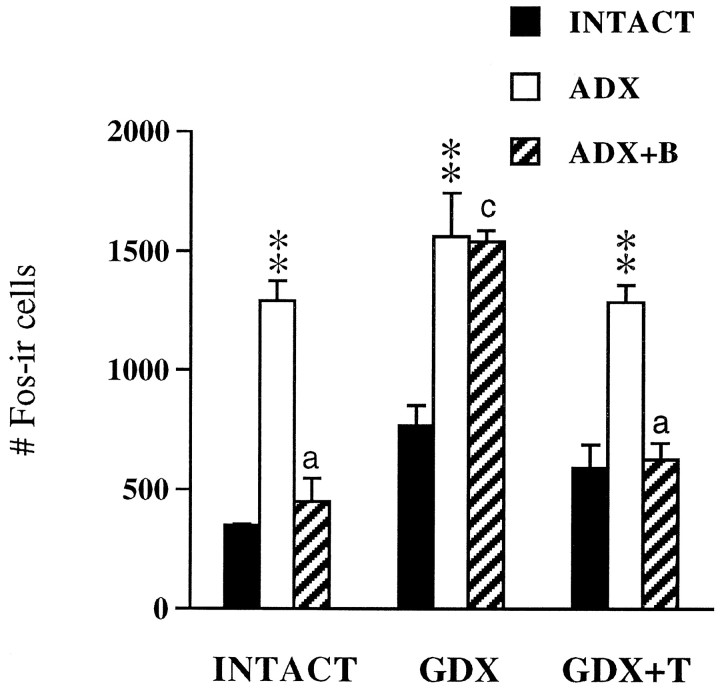

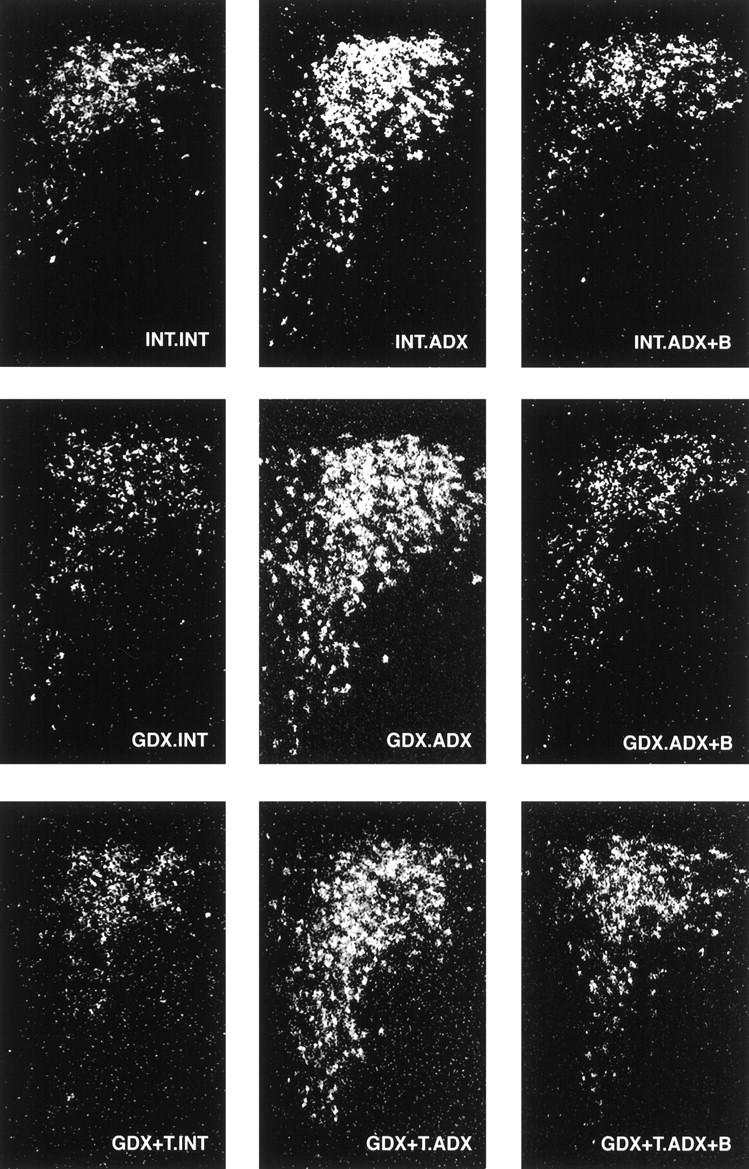

In gonadal-intact animals, ADX increased CRH mRNA levels throughout the dorsoventral extent of the PVN (Fig.2). Similar response patterns were also seen in GDX and GDX+T-replaced animals. Quantitative densitometric analysis restricted to the mp part of the PVN (mpPVN) revealed major effects of ADX ± B (p < 0.001) only, and no interactive (p = 0.332) effects. There were no major effects of GDX ± T replacement (p= 0.484) on ADX-induced elevations in CRH mRNA, nor its inhibition by B (see Fig. 4, left). Although the data were derived from tissues obtained 30 min after restraint stress in experiment 2, we and several others have shown that the expression levels and distribution of the CRH transcript are not affected by acute ether or restraint exposure (see Kovács and Sawchenko, 1996; Akana and Dallman, 1997, respectively). Thus, these results represent ADX ± B effects on basal, rather than stress-related CRH expression.

Fig. 2.

CRH expression in the PVH is dominated by ADX and B. Dark-field photomicrographs of CRH mRNA through a common level of the PVH comparing the effects of ADX ± B and GDX ± T. ADX produced reliable increases in CRH mRNA levels, reversible with B replacement (left to right). Similar response patterns were also seen in GDX and GDX+T-replaced animals (top to bottom).

Fig. 4.

Mean ± SEM medial parvocellular CRH (left) and AVP mRNA (right) responses to ADX and B-replacement as a function of gonadal status. Data are expressed as a percentage of INT. INT values (n = 6 per group). **p < 0.01 versus INTACT;bp < 0.05;cp > 0.05 versus ADX.

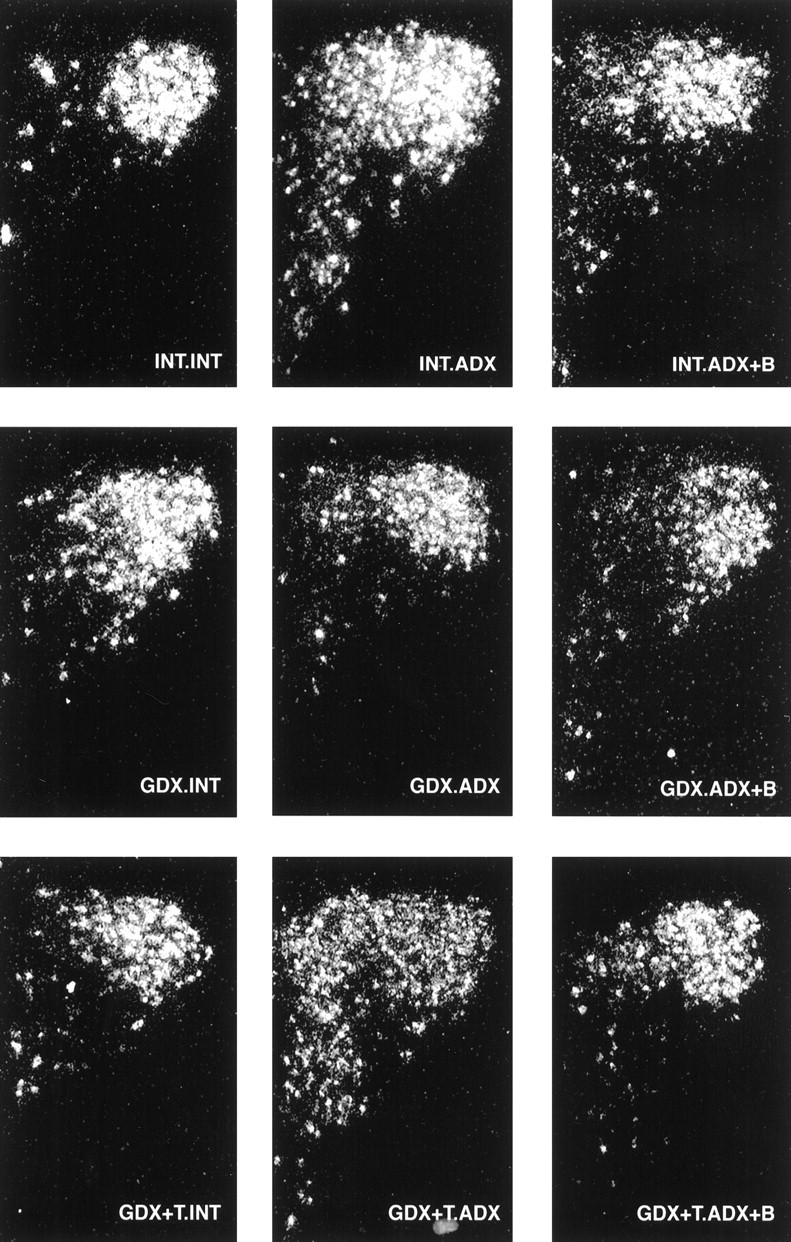

ADX similarly increased AVP mRNA expression levels in the PVH of gonadal-intact animals, yielding a pattern that mimics the broader expression of parvocellular CRH (compare Figs.2 and 3). Densitometric analysis of AVP expression showed significant adrenal (p < 0.001), gonadal (p= 0.001), and interactive (p = 0.012) effects. Thus, unlike CRH, the AVP response to ADX was altered by GDX: ADX-induced increases in AVP expression in the mpPVH were abolished in GDX animals and reinstated with T replacement (Fig. 3,middle, bottom panels; Fig.4, right). GDX exerted similar inhibitory effects on AVP expression in dorsal versus ventral mp neurons, indicated by comparable ratios of AVP mRNA levels in all groups of ADX rats (dorsal:ventral AVP = 2.0, 2.4, and 2.0 in INT.ADX, GDX.ADX, and GDX+T-ADX animals, respectively). B replacement effectively inhibited the AVP response to ADX in gonadal-intact and GDX T-replaced rats (Fig. 4, right).

Fig. 3.

AVP mRNA responses to ADX vary as a function of gonadal status. Dark-field photomicrographs of AVP mRNA in the PVH illustrating the effects of GDX and T replacement on ADX-induced elevations in AVP expression. ADX increased AVP mRNA levels in gonadal intact animals (top). This response was abolished in GDX rats (middle), and reversed by T replacement (bottom).

It is important to note that the data derived here (experiment 3) were composed of tissues pooled from basal and poststress conditions. However, we found no effects of stress on the distribution and level of AVP expression in the mpPVH (data not shown), consistent with a previous study by Herman (1995) under identical conditions. In addition, the data also confirm our preliminary report (Viau and Dallman, 1998) of an inhibitory effect of GDX on AVP transcriptional responses to ADX, as determined by autoradiographic densitometric measurements of 33P-hybridized tissue collected in experiment 2 (data not shown).

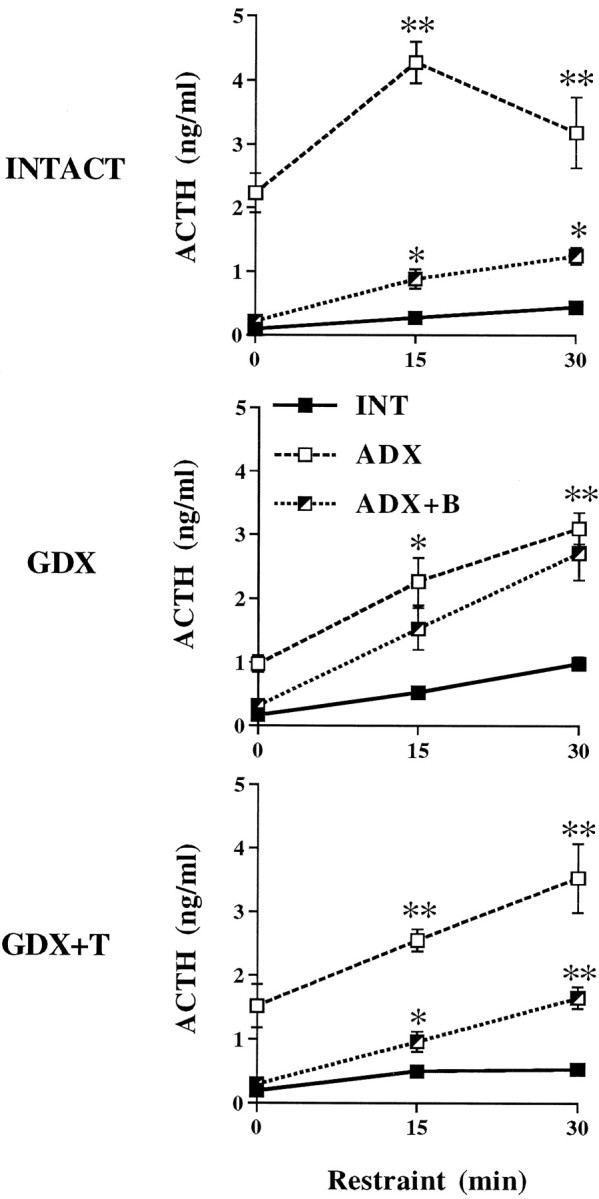

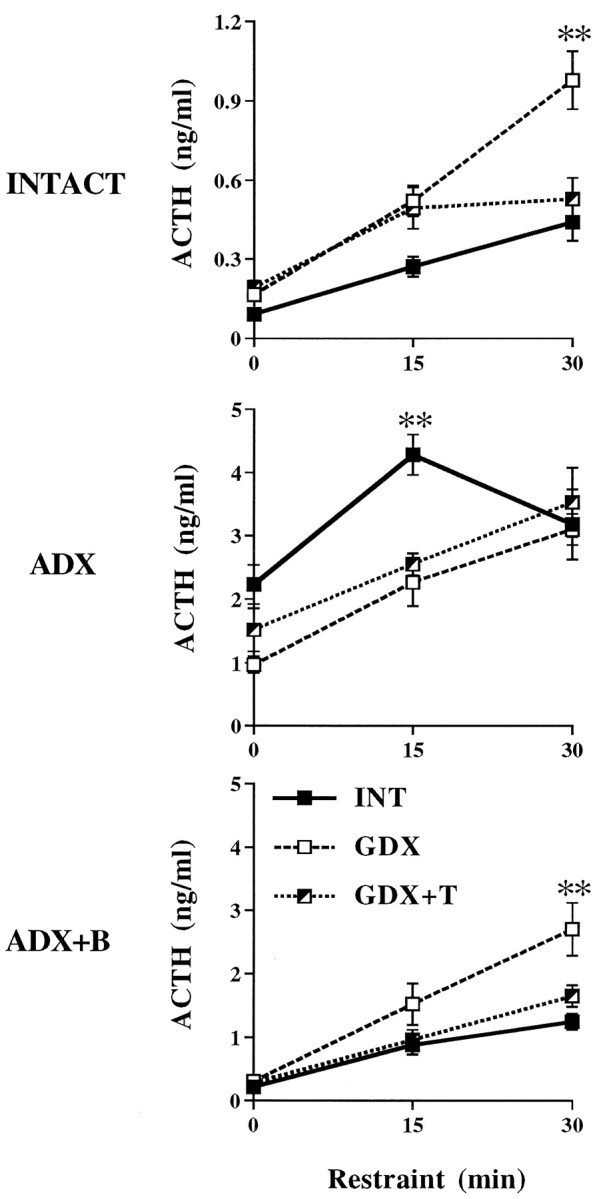

ACTH responses to restraint stress

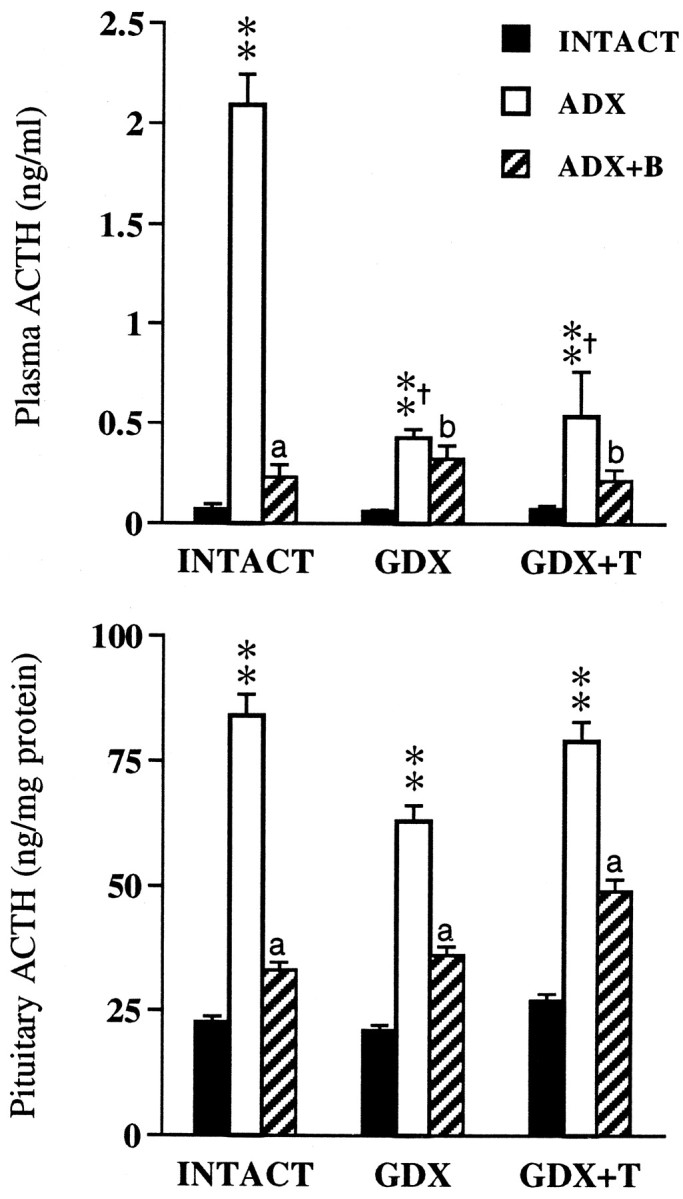

Because there were major adrenal (p < 0.0001), gonadal by adrenal (p < 0.0001), and gonadal by time of stress (p < 0.0001) interactive effects (Table 2), we assessed the effects of endocrinectomy and steroid replacement on plasma ACTH hormone responses to restraint within each gonadal and adrenal subgroup. ACTH responses to 30 min of restraint in adrenal-intact, ADX, and ADX+B-replaced animals as a function of gonadal status indicated that inhibition of stress-induced ACTH release by B is dependent, in part, on the presence of T (Fig. 5). Thus, whereas the magnitude of the ACTH response to stress in ADX animals was significantly (p < 0.01) reduced by B replacement (Fig. 5, top), this effect of B on ACTH was absent in GDX animals. GDX.ADX and GDX.ADX+B animals showed comparable ACTH levels during restraint (Fig. 5, middle). B inhibition of stress-induced ACTH release, however, was reinstated by T replacement, indicated by smaller (p < 0.01) ACTH responses in GDX+T.ADX+B versus GDX+T.ADX animals (Fig. 5,bottom).

Fig. 5.

Mean ± SEM plasma ACTH responses to 30 min restraint in adrenal-INTACT, ADX, and ADX+B animals as a function of gonadal status (n = 6 per group). **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05 versus INTACT.

Adrenal–gonadal interactions were further demonstrated by examination of ACTH release in gonadal-intact, GDX, and GDX+T animals as a function of adrenal status. Plasma ACTH responses to restraint stress were increased by GDX (p < 0.01) and decreased by T replacement in adrenal-intact animals (Fig.6, top). This effect of GDX was not apparent in ADX rats. In fact, GDX.ADX and GDX+T.ADX animals showed lower (p < 0.01) plasma ACTH levels than INT.ADX rats at 15 min of restraint, and comparable (p > 0.05) levels at 30 min restraint. T-related inhibition of stress-induced ACTH release reappeared in ADX+B animals (Fig. 6, bottom). Thus, ACTH responses to restraint were once again decreased (p < 0.01) in GDX+T versus GDX animals, however, this only occurred in the presence of B (compare Fig. 6, middle and bottom panels). Finally, consistent with plasma ACTH levels obtained by decapitation above (Fig. 1, left), blood samples obtained by tail nick revealed no effect of GDX ± T on prestress ACTH values.

Fig. 6.

Mean ± SEM plasma ACTH responses to 30 min restraint in gonadal-INTACT, GDX, and GDX+T animals as a function of adrenal status (n = 6 per group). **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05 versus INTACT.

PVH Fos responses to restraint stress

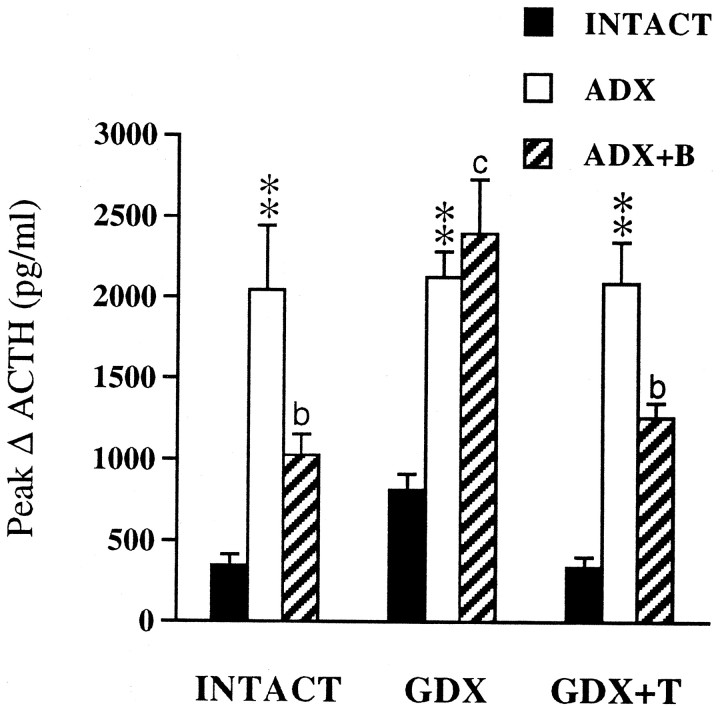

Restraint preferentially stimulated mp neurons to express Fos protein, although responsive neurons were also noted among magnocellular- and autonomic-related regions of the PVH (data not shown). Control rats that were never restrained expressed few, if any, Fos-IR neurons in the PVH under basal conditions, regardless of treatment (data not shown). Quantitative assessment of Fos-IR profiles induced by restraint showed significant gonadal and adrenal influences (both p < 0.001), as well as interactive (p = 0.003) effects, indicating that gonadal status contributes to the B inhibition of stress-induced Fos expression. Fos responses to restraint in gonadal-intact animals were significantly increased (p < 0.01) by ADX, and decreased to INTACT response levels with B replacement (Fig.7). Whereas ADX ± B exerted similar effects on Fos-IR responses to stress in GDX+T-replaced animals, B inhibition of Fos induction did not occur in GDX animals without T replacement. Thus, restraint stimulated a similar number of Fos-expressing cells in GDX.ADX and GDX.ADX+B animals. As indicated by the relationship between peak changes in ACTH responses to stress as a function of gonadal status (Fig. 8), the effects of GDX on B inhibition of Fos induction resembles the effects of GDX on stress-induced ACTH release.

Fig. 7.

Mean ± SEM number of Fos-IR cells in the mpPVH induced by 30 min restraint as a function of gonadal and adrenal status (n = 3 per group; experiment 3). **p < 0.01 versus INTACT;ap < 0.01;cp > 0.05 versus ADX (see Table 2). Note the parallel effects of B and T on plasma ACTH responses in Figure8.

Fig. 8.

Mean ± SEM peak change in ACTH responses to restraint as a function of gonadal and adrenal status (n = 6 per group; experiment 2). Peak Δs were derived from ACTH values in Figures 5 and 6. **p < 0.01 versus INTACT; bp < 0.05;cp > 0.05 versus ADX (see Table2).

DISCUSSION

In the current study we used nine groups encompassing sham endocrinectomy and endocrinectomy with or without steroid replacement. This design unmasked individual, as well as interactive gonadal and adrenal influences on basal and stress-related HPA function. Our results indicate that B and T regulate the HPA axis through different mechanisms. This is revealed by the dissimilar effects of the two endocrine systems on CRH and AVP expression in the PVN in response to ADX. By contrast, acute stress-induced ACTH secretion appears to be determined by interactive effects of B and T at a site upstream from the PVN.

Gonadal-intact animals typically hypersecreted ACTH in response to ADX, an effect reversed with B replacement. This response failed to occur in GDX.ADX animal regardless of T exposure (Fig. 1), suggesting the possibility of a B-independent, gonadal influence on ACTH release (see below). Examination of pituitary ACTH content further revealed, however, comparable effects of ADX on ACTH stores across groups (Fig.2). Whereas ADX elicited an increase in pituitary ACTH content, high ACTH content also occurred in GDX ± T.ADX animals despite lower plasma ACTH levels. Thus, in response to ADX, GDX ± T appears to inhibit pituitary ACTH release, but not ACTH synthesis.

The effects of our manipulations on CRH and AVP expression within the mp hypophysiotropic zone of the PVH were revealing. In response to ADX, CRH mRNA levels increased within mp PVN neurons; this was reversed with B replacement (Figs. 2, 4). This response pattern was seen across all unreplaced ADX groups, independent of gonadal status (GDX ± T). ADX-induced elevations in AVP expression were abolished by GDX (Figs.3, 4). AVP mRNA levels in GDX.ADX animals were comparable to those of adrenal-intact animals. T replacement reversed the inhibitory effect of GDX-ADX on AVP mRNA induction, suggesting a direct permissive role for T on AVP transcription that is revealed in the absence of B.

The extent to which these effects are shared by alterations in AVP stores and release remains to be determined. However, our findings are consistent with respect to the selective effects of GDX ± T on AVP-IR, but not CRH-IR, content in the median eminence, and the lack of GDX effects on CRH-IR and mRNA, with respect to short term (1–2 weeks) ADX (Almeida et al., 1992; Viau and Meaney, 1996, but see Bingaman et al., 1994). Anterior pituitary corticotrophs do not contain androgen receptors and express minimal aromatase activity (McEwen, 1980;Thieulant and Duvall, 1985). Thus, decreased plasma ACTH responses to ADX in GDX ± T animals are least explainable by direct effects of T on pituitary CRH and AVP receptor levels, but rather reflect gonadal influences on CRH or AVP secretion.

In gonadal-intact animals, circulating T levels were significantly decreased by ADX (Table 1), consistent with previous reports of decreased luteinizing hormone and T levels in ADX animals (Lescoat et al., 1984). Our T-replacement regimen produced plasma T levels similar to INT.INT but higher than those in ADX rats (Table 1). The role of decreased T replacement levels on ACTH secretory responses to ADX remains to be examined, however, the normal decline in T levels in gonadal-intact animals appears to play a significant role in mediating AVP transcriptional and ACTH secretory responses to ADX. Our present findings in the ADX animal clearly unmask B-independent, gonadal effects on HPA function.

In contrast, cross-talk between gonadal and adrenal steroid regulation of ACTH release was evident under acute stress conditions (Figs. 5, 6). B replacement sufficient to normalize, at least in part, the ACTH response to restraint in gonadal-intact animals did not normalize ACTH in GDX males. This GDX effect on stress-induced ACTH release was reversed with T replacement, indicating that the inhibitory effects of B on stress-related HPA function require T. Conversely, the inhibitory effects of T on stress-induced ACTH release were similarly offset in GDX+T.ADX without B replacement. Quantative analyses of the number of restraint-sensitive Fos-IR neurons within mp neurons of the PVN revealed a strong parallel between the effects of our manipulations on stress-induced Fos and the magnitude of the ACTH response (compare Figs. 7 and 8). This suggests that the amplitude of the ACTH response to stress is determined by gonadal and adrenal steroid actions at the level of stimulatory input or drive to the PVN.

In models of chronic social stress, subordinate males show increases in AVP-IR, but not CRH-IR, within the external (hypophysiotropic) zone of the median eminence (De Goeij et al., 1992). Whereas subordinates show a selective depletion of AVP from the median eminence and increased ACTH and B levels after exposure to a dominant male in a novel surrounding, these responses fail to occur in a familiar environment (De Goeij et al., 1992; Romero et al., 1995). Thus, the amplitude of the ACTH response to stress cannot be predicted on the basis of ACTH secretagogue synthesis and stores alone. By analogy, GDX animals showed decreased ACTH responses to ADX associated with decreased AVP expression in the PVN; no such deficits in ACTH release were seen during restraint. Stress-induced ACTH release may be determined, in larger part, by the degree to which B and T modulate neurogenic drive to the mpPVN, rather than by effects on CRH and AVP synthesis.

A wealth of studies has indicated that the feedback effects of glucocorticoids on ACTH release are neurogenic in nature, mediated upstream from the PVN (Herman et al., 1990; Herman and Cullinan, 1997). Similarly, it is likely that B and T interactions on stress-induced ACTH also occur upstream from the PVN. This is consistent with the fact that androgen receptors are restricted to autonomic-related neurons of the PVN (Simerly et al., 1990; Zhou et al., 1994), and our own findings in which T implants into the medial preoptic area (MPOA) decrease resting-state levels of AVP, but not CRH, in the median eminence (Viau and Meaney, 1996). Moreover, ACTH responses to restraint are inhibited by both B and T implants in MPOA (Viau and Meaney, 1996). Thus, this brain region could represent a site of the interactive effects of B and T on stress-induced ACTH release. In addition to the MPOA, the septum and amygdala must be considered, given their spheres of influence on reproduction and social behavior, HPA function, and concentrations of glucocorticoid and androgen receptors (Landgraf et al., 1995;Sánchez et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1996; Gray and Bingaman, 1996).

In conclusion, B and T heavily interact to regulate HPA activity by several different mechanisms. The importance of gonadal status in HPA function is underscored by the extent to which GDX affects ACTH responses to ADX, as well as B inhibition of stress-induced ACTH release. Finally, our design provides a useful model with which to ascribe individual and interactive roles for B and T on resting-state ACTH secretagogue expression levels in the PVN, and extend these findings to other brain regions supplying basal and stress-related information to the PVN.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK 28172.

Correspondence should be addressed to M. F. Dallman, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143-0444.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear populations from microtome populations from microtome sections. Anat Rec. 1946;94:239–247. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akana SF, Dallman MF. Chronic cold in adrenalectomized, corticosterone (B)-treated rats: facilitated corticotropin responses to acute restraint emerge as B increases. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3249–3258. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akana SF, Jacobson L, Cascio CS, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Constant corticosterone replacement normalizes basal adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) but permits sustained ACTH hypersecretion after stress in adrenalectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1337–1342. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida OFX, Hassan AHS, Harbuz MS, Linton EA, Lightman SL. Hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone and opioid peptide neurons: functional changes after adrenalectomy and/or castration. Brain Res. 1992;571:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90654-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatnagar S, Dallman M. Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience. 1998;84:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingaman EW, Magnuson DJ, Gray TS, Handa RJ. Androgen inhibits the increases in hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and CRH-immunoreactivity following gonadectomy. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;59:228–234. doi: 10.1159/000126663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohler HCL, Zoeller RT, King JC, Rubin BS, Weber R, Merriam GR. Corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA is elevated on the afternoon of proestrous in the parvocellular paraventricular nuclei of the female rat. Mol Brain Res. 1990;8:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan RK, Brown ER, Ericsson A, Kovács KJ, Sawchenko PE. A comparison of two immediate-early genes, c-fos and NGFI-B, as markers for functional activation in stress-related neuroendocrine circuitry. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5126–5138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05126.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi S, Wong LS, Yamat C, Dallman MF. Hypothalamic ventromedial nuclei amplify circadian rhythms: do they contain a food-entrained endogenous oscillator? J Neurosci. 1998;18:3843–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Cascio CS, Darlington DN, Jacobson L, Levin N. Regulation of ACTH secretion: variations on a theme of B. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1987;43:113–73. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571143-2.50010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Scribner KA, Bradbury MJ, Walker C-D, Strack AM, Cascio CS. Stress, feedback and facilitation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neuroendocrinology. 1993;4:517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1992.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Goeij DC, Dijkstra H, Tilders FJ. Chronic psychosocial stress enhances vasopressin, but not corticotropin-releasing factor, in the external zone of the median eminence of male rats: relationship to subordinate status. Endocrinology. 1992;131:847–53. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1322285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein LE, Rasmusson AM, Bunney BS, Roth RH. Role of the amygdala in the coordination of behavioral, neuroendocrine, and prefrontal cortical monoamine responses to psychological stress in the rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4787–4798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04787.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray TS, Bingaman EW. The amygdala: corticotropin-releasing factor, steroids, and stress. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:155–68. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handa RJ, Burgess LH, Kerr JE, O’Keefe JA. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav. 1994;28:464–476. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman JP. In situ hybridization analysis of vasopressin gene transcription in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the rat: regulation by stress and glucocorticoids. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:15–27. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herman JP, Wiegand SJ, Watson SJ. Regulation of basal corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the paraventricular nucleus: effects of selective hypothalamic deafferentations. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2408–2417. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-5-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovács KJ, Sawchenko PE. Sequence of stress-induced alterations in indices of synaptic and transcriptional activation in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:262–273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landgraf R, Gerstberger R, Montkowski A, Probst JC, Wotjak CT, Holsboer F, Engelmann M. V1 vasopressin receptor antisense oligodeoxynucleotide into septum reduces vasopressin binding, social discrimination abilities, and anxiety-related behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4250–4258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lescoat G, Lescoat D, Garnier D. Dynamic changes in plasma luteinizing hormone and testosterone after stress in the male rat. Influence of adrenalectomy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1984;62:1231–1233. doi: 10.1139/y84-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li HY, Sawchenko PE. Hypothalamic effector neurons and extended circuitries activated in “neurogenic” stress: a comparison of footshock effects exerted acutely, chronically, and in animals with controlled glucocorticoid levels. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:244–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McEwen BS. Binding and metabolism of sex steroids by the hypothalamic-pituitary unit: physiological implications. Annu Rev Physiol. 1980;42:97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.42.030180.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patchev VK, Almeida OF. Gender specificity in the neural regulation of the response to stress: new leads from classical paradigms. Mol Neurobiol. 1988;16:63–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02740603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patchev VK, Almeida OF. Gonadal steroids exert facilitating and “buffering” effects on glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone and corticosteroid receptor genes in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7077–7084. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-07077.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero LM, Levine S, Sapolsky RM. Patterns of adrenocorticotropin secretagogue release in response to social interactions and various degrees of novelty. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00052-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez MM, Aguado F, Sánchez-Toscano F, Saphier D. Effects of prolonged social isolation on responses of neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, preoptic area, and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to stimulation of the medial amygdala. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:525–541. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00083-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawchenko PE, Arias C, Bittencourt JC. Inhibin beta, somatostatin, and enkephalin immunoreactivities coexist in caudal medullary neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;291:269–280. doi: 10.1002/cne.902910209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simerly RB, Chang C, Muramatsu M, Swanson LW. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmons DM, Arriza JL, Swanson LW. A complete protocol for in situ hybridization of messenger RNAs in brain and other tissues with radiolabeled single-stranded RNA probes. J Histotechnol. 1989;12:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith CJ, Norman RL. Circadian periodicity in circulating cortisol is absent after orchidectomy in rhesus macques. Endocrinology. 1987;121:2186–2191. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-6-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swanson LW, Kuypers HGJM. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and organization of projections to the pituitary, dorsal vagal complex, and spinal cord as demonstrated by retrograde fluorescence double-labeling methods. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:555–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanson LW, Simmons DM. Differential steroid hormone and neural influences on peptide mRNA levels in CRH cells of the paraventricular nucleus: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:413–435. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thieulant ML, Duvall J. Differential distribution of androgen and estrogen receptors in rat pituitary cell populations separated by centrifugal elutriation. Endocrinology. 1985;116:1299–1303. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-4-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urban JH, Miller MA, Dorsa DM. Dexamethasone-induced suppression of vasopressin gene expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial amygdala is mediated by changes in testosterone. Endocrinology. 1991;129:109–116. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-1-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viau V, Dallman MF. Corticosterone inhibition of stress-, but not adrenalectomy-induced ACTH release requires testosterone. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1998;24:1375. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viau V, Meaney MJ. Variations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress during the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology. 1991;129:2503–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viau V, Meaney MJ. The inhibitory effect of testosterone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress is mediated by the medial preoptic area. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1866–1876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01866.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viau V, Sawchenko PE. Acute and repeated restraint differentially activate subsets of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) expressing neurosecretory neurons in the paraventricular nucleus. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:990. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viau V, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Increased plasma ACTH responses to stress in nonhandled compared with handled rats require basal levels of corticosterone and are associated with increased levels of ACTH secretagogues in the median eminence. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1097–1105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01097.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watts AG, Swanson LW. Diurnal variations in the content of preprocorticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acids in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of rats of both sexes as measured by in situ hybridization. Endocrinology. 1989;125:1734–1738. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-3-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitnall MH. Distributions of pro-vasopressin expressing and pro-vasopressin deficient CRH neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus of colchicine-treated normal and adrenalectomized rats. J Comp Neurol. 1988;275:13–28. doi: 10.1002/cne.902750103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young EA. The role of gonadal steroids in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1995;9:371–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou L, Blaustein JD, De Vries GJ. Distribution of androgen receptor immunoreactivity in vasopressin- and oxytocin-immunoreactive neurons in the male rat brain. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2622–2627. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.6.8194487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]