Abstract

The three α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes have distinct tissue distributions, desensitization properties, and, in some cell types, subtype-specific subcellular localization and trafficking properties. The subtypes also differ in their neuronal physiology. Therefore, we have investigated the localization and targeting of human α2-adrenoceptors (α2-AR) in PC12 cells, which were transfected to express the α2-AR subtypes A, B, and C. Inspection of the receptors by indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy showed that α2A-AR were mainly targeted to the tips of the neurites, α2B-AR were evenly distributed in the plasma membrane, and α2C-AR were mostly located in an intracellular perinuclear compartment. After agonist treatment, α2A- and α2B-AR were internalized into partly overlapping populations of intracellular vesicles. Receptor subtype-specific changes in PC12 cell morphology were also discovered: expression of α2A-AR, but not of α2B- or α2C-AR, induced differentiation-like changes in cells not treated with NGF. Also α2B-AR were targeted to the tips of neurites when they were coexpressed in the same cells with α2A-AR, indicating that the targeting of receptors to the tips of neurites is a consequence of a change in PC12 cell membrane protein trafficking that the α2A-subtype induces. The marked agonist-induced internalization of α2A-AR observed in both nondifferentiated and differentiated PC12 cells contrasts with earlier results from non-neuronal cells and points out the importance of the cellular environment for receptor endocytosis and trafficking. The targeting of α2A-AR to nerve terminals in PC12 cells is in line with the putative physiological role of this receptor subtype as a presynaptic autoreceptor.

Keywords: α2-adrenoceptors, endocytosis, internalization, differentiation, PC12 cells, immunocytochemistry, targeting

Three genes encoding adrenergic α2-receptors (α2-AR) have been cloned (α2A/D, α2B, and α2C) in human and rodents (Kobilka et al., 1987; Regan et al., 1988; Lomasney et al., 1990; Zeng et al., 1990; Lanier et al., 1991; Chruscinski et al., 1992;Link et al., 1992). The α2-AR are G-protein-coupled receptors and mediate effects of endogenous catecholamines and many therapeutic drugs via G-proteins to a variety of effectors, including adenylyl cyclases and ion channels (MacDonald et al., 1997). The three α2-AR subtypes have quite similar ligand binding properties but different desensitization properties, as well as distinct subcellular and tissue distributions.

In the rodent brain, α2A-AR expression is widely distributed in noradrenergic projection areas but is also abundant in the locus ceruleus and other noradrenergic nuclei, in line with the presynaptic autoreceptor function of this subtype (Nicholas et al., 1993; Scheinin et al., 1994; Talley et al., 1996;Wang et al., 1996; MacDonald et al., 1997). α2A-AR are also present in the medulla and spinal cord in areas involved in control of autonomic functions and nociception (Rosin et al., 1993; Nicholas et al., 1996). In studies on genetically engineered mice, the α2A-AR has been shown to be crucial in the central hypotensive (MacMillan et al., 1996), sedative (Lakhlani et al., 1997; Sallinen et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997), and analgesic effects (Lakhlani et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997) of α2-AR agonists. In the CNS, α2B-AR are only expressed in the thalamus (McCune et al., 1993; Nicholas et al., 1993; Scheinin et al., 1994;Winzer-Serhan and Leslie, 1997), but they are present in many tissues outside the CNS, and their physiological significance has been clearly established in the regulation of peripheral blood vessel tone (Link et al., 1996). α2C-AR are mainly localized in the basal ganglia, olfactory tubercle, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex (Nicholas et al., 1996; Rosin et al., 1996), and behavioral studies with transgenic mice suggest that α2C-ARs may serve important functions in sensorimotor integration (Sallinen et al., 1998a,b).

Differences in receptor regulation have been described for the three α2-AR subtypes. Long-term desensitization has been observed in fibroblast cell lines for all α2-AR subtypes, but the extent of desensitization is greater for the α2A- and α2B-AR subtypes compared with α2C-AR (Eason and Liggett, 1992, 1993). The subtypes also show distinct subcellular localization and targeting patterns in some non-neuronal cell types (von Zastrow et al., 1993;Daunt et al., 1997). Because the α2-AR have fundamental functions in neuronal physiology and pharmacology, we decided to examine their subcellular distributions and the effects of agonist activation on their trafficking within a neuronal cell type. As a model, we used the rat pheochromocytoma cell line PC12, which has many similarities with postganglionic sympathetic neurons (Lee et al., 1977, 1980), especially after differentiation (Greene and Tischler, 1976). Our hypothesis was that the α2A-AR subtype would be specifically targeted to nerve terminals, as expected for an autoreceptor, and that the localization of α2A-AR would thus differ from the other two α2-AR subtypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and chemicals. Rabbit polyclonal antisera against the C termini of α2A- and α2C-AR (Daunt et al., 1997) were kindly provided by Dr. B. K. Kobilka (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). A monoclonal antibody against α2B-AR (Liitti et al., 1997) was kindly provided by S. Liitti and H. Frang (Center for Biotechnology, Turku, Finland). Hygromycin B was from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN), FITC-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG, (−)norepinephrine, and the neomycin analog G418 were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and the FITC-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit IgG was from Silenius Laboratories (Victoria, Australia). The anti-neurofilament (NF) 160 kDa antibody and the radioligand [3H]RX821002 [2-(2-methoxy-1,4-benzodioxan-2-yl)-2-imidazoline] were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Buckinghamshire, UK). RX821002 was from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA), atipamezole and dexmedetomidine were gifts from Orion Pharma (Turku, Finland), and rauwolscine was from Carl Roth KG (Karlsruhe, Germany). Cell culture reagents were from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD) unless mentioned otherwise. Nerve growth factor (NGF) was from Promega (Madison, WI). Other chemicals were of analytical or reagent grade and were purchased from commercial suppliers.

Cell culture. PC12 cells (American Type Culture Collection, CRL 1721) were grown in collagen-coated [1% Vitrogen 100 (Collagen Corporation, Fremont, CA) and 0.1% BSA] 25 and 75 cm2 cell culture flasks (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Meylan, France) in DMEM supplemented with 2.5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 12.5% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS) (Kraeber GmbH & Co., Hamburg, Germany), 292 mg/ll-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 20 mm NaHCO3, in water-saturated 5% CO2 at 37°C. Two-thirds of the growth medium was changed every third day, and cells were replated every 5–6 d. Passages 4–20 of stable transfected clones were used. Before plating the cells onto glass coverslips, the cells were trypsinized, because harvesting with a rubber policeman altered the microscopic morphology and slowed the differentiation of PC12 cells. A rubber policeman was used for harvesting cells for radioligand binding studies. Differentiation was induced by incubating cells with 50–100 nm 2.5S NGF in DMEM plus 1–3% HS on collagen or 0.1 mg/ml poly-l-lysine-coated (Sigma) glass coverslips or cell culture plastics. Non-transfected PC12 cells did not express endogenous α2-AR as evidenced by immunocytochemistry and radioligand binding.

Stable expression of human α2-ARs.The cDNAs encoding human α2-AR subtypes were a gift from Dr. R. J. Lefkowitz (Duke University, Durham, NC) (Kobilka et al., 1987; Regan et al., 1988; Lomasney et al., 1990). The construction of the pMAMneo- and pREP-based (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) expression vectors for stable or semistable expression, respectively, of human α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-AR (Marjamäki et al., 1992, 1993) was performed with standard methods. The PC12 cells were plated onto collagen-coated tissue culture dishes and transfected 24 hr later by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Chen and Okayama, 1987,1988). The selection of stable or semistable transfectants was performed with 500 μg/ml the neomycin analog G418 (Greene et al., 1991) or Hygromycin B, respectively. Resultant clones were screened for α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-AR expression by immunofluorescent staining and radioligand binding. Only weak immunostaining was observed in clones expressing <500–800 fmol α2-AR/mg protein. Stable clones expressing receptor densities of 1.0–2.5 pmol/mg total cellular protein were chosen for further studies. The double transfections for colocalization studies were done by pREP-mediated transfection of stable PC12α2Acells with α2B-cDNA and of stable PC12α2B cells with α2A-cDNA. The coexpression of α2A- and α2B-AR was detected by double-staining with subtype-specific antibodies.

Preparation of cell homogenates and saturation binding assays. Cells were harvested into chilled PBS, pelleted, and frozen at −70°C. Saturation binding assays with cell homogenates and [3H]RX821002 were performed in K+-phosphate buffer as described previously (Halme et al., 1995).

Receptor activation. Cells were plated on collagen- or poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips at 1–2 × 104cells/cm2. After 4–6 d of culture, the differentiated and nondifferentiated cells were treated with serum-free DMEM containing 10 μm norepinephrine or 10 nm dexmedetomidine for 30 min at 37°C, in 5% CO2. The medium was then aspirated, and the cells were rinsed once with 4°C PBS and fixed.

Immunocytochemistry. Cultures of PC12 cells on glass coverslips were fixed for 20 min at room temperature or for 5 min at 4°C and 15 min at room temperature (for agonist-treated cells) with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After fixation, the cells were either stained immediately or stored in PBS at 4°C for later staining. The staining was performed at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating the cells for 45 min with blocking buffer containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) as permeabilizing agent (not added in all experiments) and 5% non-fat dry milk in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6. The cells were incubated for 45 min with primary antibodies or antisera diluted in the same buffer (anti-α2A and -α2C, 1:500; anti-α2B, 10 μg/ml, anti-NF, 1:100). After incubation, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS, followed by 5 min blocking and incubation with secondary antibody diluted 1:500 [FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and FITC- or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG] in the blocking buffer (for 30 min) in darkness. After rinsing three times with PBS, the coverslips were mounted for fluorescent microscopy onto a drop of anti-fade mounting medium containing 50% glycerol, 100 mg/ml 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2.]octane (Sigma) and 0.05% sodium azide in PBS on microscope slides. As negative controls, transfected PC12 cells were stained in a similar manner but without the primary antibody, or nontransfected PC12 cells were stained as above. Stained cells were not observed under these conditions. The specificity of the receptor antibodies was verified by cross-staining the α2-AR subtypes in PC12 cells. Single- and double-labeled immunofluorescent microscopy was performed using a conventional fluorescence microscope (Olympus BHS, Olympus 100×/D Plan Apo, 100 UV, 1.30 objective; Olympus Opticals, Tokyo, Japan) and a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica DM RXA, 100×/1.4 oil ICT:D objective; Leica, Nussloch, Germany).

Immunocytochemistry of cells expressing both α2A- and α2B-AR was performed using simultaneously the above described rabbit polyclonal antibody against α2A-AR and the mouse monoclonal antibody against α2B-AR. Anti-rabbit TRITC and anti-mouse FITC were used for visualization.

Electron microscopy. PC12 cells were cultured and fixed as described above and post-fixed with potassium ferrocyanide-osmium fixative (Karnovsky, 1971). The cells were embedded in epoxy-resin (Glycidether 100; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and then sectioned for electron microscopy. Ultrathin sections were stained with 12.5% uranyl acetate (Stempak and Ward, 1964) and 0.25% lead citrate (Venable and Coggeshall, 1965) and examined in a Jeol JEM-100SX electron microscope (Jeol, Akishima, Japan).

RESULTS

α2A-AR are distinctly targeted in differentiating PC12 cells

During NGF-induced differentiation, neurites were seen as soon as after 2 d treatment in α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-AR-transfected PC12 cells. Growth cones were seen on plasma membranes of transfected and untransfected PC12 cells as soon as after the first day of NGF treatment. During differentiation, the cells flattened out, and there was an increase in the number of growth cones and in the number and length of neurites.

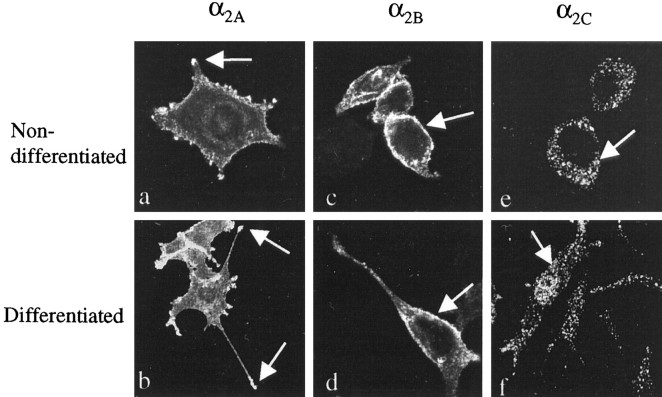

PC12 cells transfected with the α2A-AR plasmid acquired an altered phenotype also without NGF treatment (see below). In PC12α2A cells not treated with NGF, α2A-AR staining was observed on plasma membranes all over the cell (Fig.1a). Abundant α2A-AR staining was present in the filopodia and the growth cones of PC12α2A cells, which remained brightly stained during the entire course of differentiation. After 5–6 d of NGF-induced differentiation and neurite outgrowth, the distal segments of the neurites stained more brightly compared with the weaker staining of the plasma membrane over the cell body, suggesting that the receptors are clustered to the tips of neurites (Fig.1b).

Fig. 1.

Scanning confocal images of nondifferentiated (a, c, e) (100×) and differentiated (b, d,f) (50×) PC12 cells expressing human α2-AR subtypes, immunostained with α2-AR subtype-specific antibodies. The images are summations of 12 midsections of permeabilized cells. In nondifferentiated PC12α2A cells, α2A-AR staining is seen on plasma membranes all over the cells, and clusters of α2A-AR are seen on filopodia and growth cones (a, arrow). After NGF-treatment, clustering of the α2A-AR staining to the tips (arrows) of the neural extensions is seen (b). α2B-AR staining is localized evenly on plasma membranes (arrows) in nondifferentiated (c) and differentiated (d) cells, and α2C-AR staining is localized mainly intracellularly (arrows) before (e) and after (f) differentiation.

α2B-AR were localized evenly on plasma membranes in undifferentiated (Fig. 1c) and differentiated (Fig. 1d) PC12 cells, and there was no enrichment of α2B-AR staining in growth cones or neurites during NGF-induced differentiation (Fig. 1d). α2C-AR staining was found mainly intracellularly and perinuclearly in undifferentiated (Fig.1e) and differentiated (Fig. 1f) PC12 cells, and the plasma membrane staining was weaker compared with the α2A- and α2B-AR subtypes.

α2A- and α2B-AR internalize after agonist activation

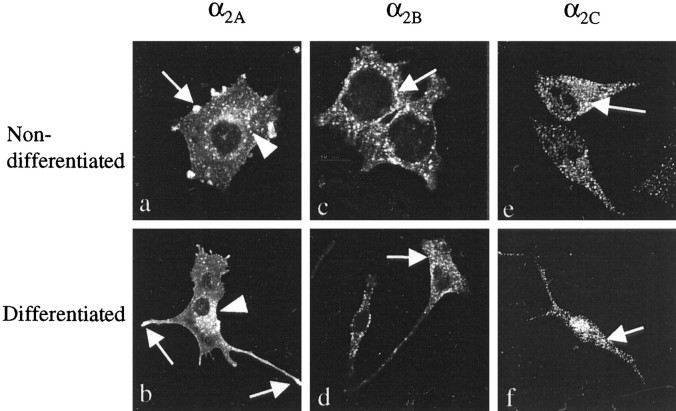

Receptor activation was induced with the α2-AR agonists norepinephrine (10 μm, 30 min) and dexmedetomidine (10 nm, 30 min), in both undifferentiated and differentiated cells. Clear intracellular punctate staining (Fig.2a) could be seen in agonist-treated PC12α2A cells; this was not observed in cells not treated with α2-AR agonists. These clustered immunoreactive puncta were considered to represent internalized receptors in some intracellular compartment of the cells, because no punctate staining was observed in nonpermeabilized cells. Also, confocal microscopy showed clusters of immunoreactive material in the midsections of the cells, confirming their intracellular nature. The growth cones and the filopodia of PC12α2A cells remained brightly stained after agonist treatment (Fig. 2a,b).

Fig. 2.

Scanning confocal images of nondifferentiated (a, c, e) (100×) and differentiated (b, d,f) (50×) PC12 cells expressing human α2-AR subtypes after norepinephrine (10 μm) treatment. The images are summations of 12 midsections of permeabilized cells. The cells were immunostained with α2-AR subtype-specific antibodies. Similar receptor trafficking is observed in nondifferentiated and differentiated cells: α2A- and α2B-AR are internalized into intracellular vesicles (arrowheads) after norepinephrine-induced receptor activation (a–d), although the growth cones and neural tips of PC12α2A cells remain brightly stained (a, b, arrows). The localization of α2C-AR is not changed by agonist treatment (e, f). More numerous and brighter intracellular vesicles are seen in PC12α2Bcells (c, d) than in PC12α2A cells (a, b), suggesting that internalization of α2B-AR is stronger than that of α2A-AR.

The agonist treatment also induced internalization of α2B-AR, which was stronger than that of α2A-AR; in confocal microscopy, most of the receptor staining of agonist-treated PC12α2Bcells was observed intracellularly, and plasma membrane staining was almost invisible (Fig. 2c). No change was observed in the localization of agonist-activated α2C-AR compared with cells not treated with α2-AR agonists (Fig. 2e). There was no difference in the agonist-induced internalization in nondifferentiated versus differentiated PC12α2B and PC12α2C cells (Fig.2d,f). All differentiation and receptor activation experiments have been repeated with 2–4 independent clones of the three different human α2-AR subtypes, 3–30 times per clone.

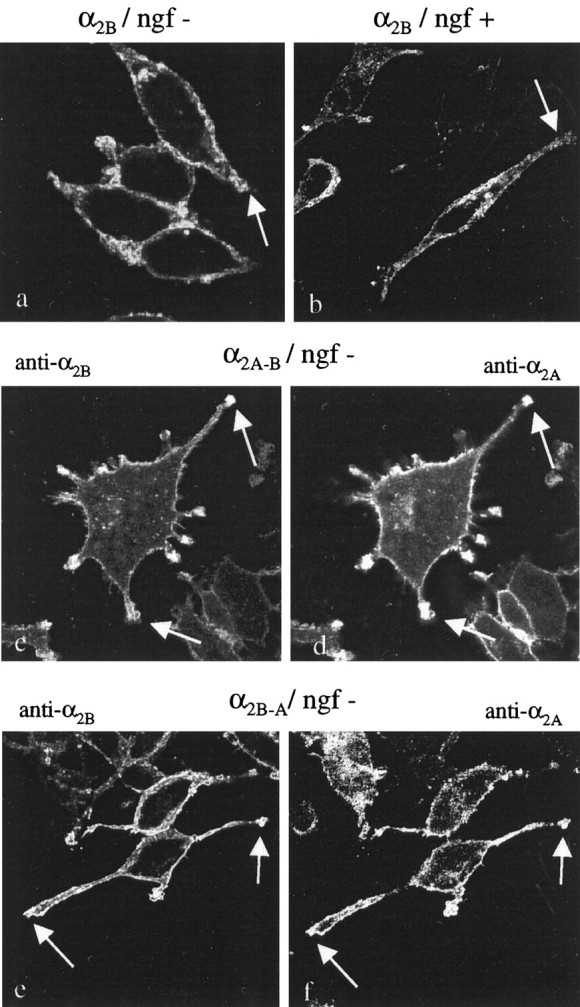

α2A-and α2B-AR internalize into partly separate intracellular vesicles

Immunostaining and scanning confocal microscopy of agonist-treated double-transfected PC12α2A-B cells showed that α2A- and α2B-AR are colocalized in plasma membrane and neural tips before agonist treatment (Fig. 3a,c). After agonist treatment, clear internalized vesicles of both α2A- and α2B-AR were seen in 0.16 μm slice thin images (Fig. 3b,d). Intracellular staining of vesicles containing these two internalized receptor subtypes was partly overlapping (yellow in confocal images) and partly distinct (red andgreen, respectively), suggesting that α2A- and α2B-AR would be internalized into partly distinct populations of intracellular vesicles. However, both receptor subtypes remained in neural tips after agonist treatment (Fig. 3b,d).

Fig. 3.

Scanning confocal images of PC12α2A-B cells coexpressing α2A- and α2B-AR immunostained with subtype-specific rabbit anti-α2A antiserum–anti-rabbit TRITC (red) and mouse anti-α2Bantibody–anti-mouse FITC (green). Images (a, b, 100×; c,d, 50×) represent single 0.16 μm thin midsections from scanned cells. Overlapping α2A- and α2B-AR staining (yellow) is seen on the plasma membrane and in the tips (arrows) of neural extensions (a–d), indicating colocalization of α2A- and α2B-AR in these locations. After agonist treatment (b, d), α2A- and α2B-AR are internalized into partly separate (separate red and greenpuncta) (arrowheads) and partly shared (yellow puncta) intracellular vesicles. The tips of the neurites remain yellow (b,d) (arrows), indicating that the two subtypes are still colocalized and not redistributed by agonist treatment in these parts of the cells.

Expression of α2A-AR induces differentiation of PC12 cells

The culture of PC12 cells was performed according to Greene and Tischler (1976), using collagen-coated Falcon cell culture flasks after selection of the transfected clones. The morphology of the cells was not changed during 3–20 passages when the cells were replated every 5–6 d and divided 1:4–6.

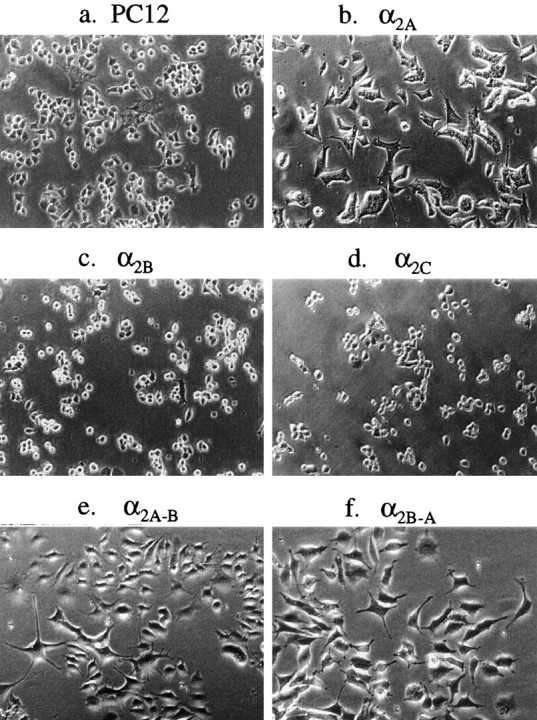

Receptor subtype-specific changes in PC12 cell shape and growth type were discovered after the selection of the transfected clones. The shape of PC12α2A cells was clearly different from clones expressing α2B- and α2C-AR. The PC12α2Acells flattened out, and their cytoplasm was thinner compared with the other clones. The cells tended to differentiate without NGF, and they developed growth cones and short neurites (Fig.4b). The extent of this tendency to differentiate was proportional to the receptor expression level of individual α2A-AR-expressing clones (n = 5) (data not shown). To examine the possibility that activation of α2A-AR by endogenous norepinephrine produced by the PC12α2A cells would induce this morphological change, we cultured the cells in medium supplemented with selected α2-AR antagonists to block α2A-AR. Treatment of PC12α2A cells with the α2-AR antagonists atipamezole, rauwolscine, or RX821002 (5 μm) did not influence the tendency of PC12α2A cells to undergo morphological differentiation. The shape of PC12α2B and PC12α2C cells (Fig. 4c,d) remained similar to that of untransfected PC12 cells. Both untransfected and transfected PC12 cells were successfully stained with an anti-neurofilament antibody to confirm the preserved neuronal phenotype of the cells (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Phase-contrast microscopic images (10×) of living nontransfected (a) and α2-AR expressing (b–f) PC12 cells in collagen-coated Falcon cell culture flasks. Compared with nontransfected PC12 cells (a), the α2A-AR expressing cells (b) showed morphological changes under normal culturing conditions during the first few (1–3) passages after transfection; the PC12α2A cells flattened out and their cytoplasm was thinner compared with clones expressing other α2-AR subtypes, and they developed growth cones and short neurites without NGF-treatment (b). The morphology of PC12α2B and PC12α2C cells remained similar to the nontransfected cells (c,d). The different morphology of PC12α2Acells (α2A-B) did not change by the coexpression of α2B-AR (e), but expression of α2A-AR in PC12α2B(α2B-A) cells induced similar morphological changes (f) as after transfection of PC12 cells with α2A-AR alone (b). Culture from passage 3 to passage 20 did not change the acquired morphology of the clones.

The α2A -AR-induced differentiation allows targeting of α2A- and α2B-AR to the tips of neural extensions of PC12 cells

To explore whether the targeting of α2A-AR to the tips of neural extensions of differentiated PC12 cells would be secondary to the changes induced by expression of the α2A-subtype, cotransfection studies were performed. Expression of α2A-AR in PC12α2B cells (PC12α2B-A cells) induced similar differentiation-like morphological changes, as seen after transfection with α2A-AR alone. The morphological changes were obvious as soon as during the first passage (Fig.4f). Expression of α2B-AR in PC12α2A cells (PC12α2A-B cells) did not change the α2A-induced differentiated phenotype of the cells (Fig. 4e). Immunostaining of cotransfected PC12α2A-B and PC12α2B-Acells, visualized by conventional fluorescent microscopy and scanning confocal microscopy, showed overlapping α2A- and α2B-specific immunoreactivity in the tips of neural extensions (Figs. 3,5c–f). This indicates that expression of α2A-AR permits targeting of α2B-AR also to neurite tips in PC12 cells. The different distribution of α2B-AR in PC12α2B cells differentiated with NGF and in PC12α2A-B/α2B-A cells expressing both α2A- and α2B-AR is illustrated in Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Scanning confocal images (50–100×) of non-NGF-differentiated (a, c,d, e, f) and NGF-differentiated (b) PC12 cells expressing human α2B-AR alone (a, b) and coexpressing human α2A- and α2B-AR (c–f), immunostained with monoclonal anti-human α2B-AR antibody (a, b,c, e) and polyclonal α2A-AR antiserum (d, f). The images are summations of 12 midsections of permeabilized cells. When expressed alone, α2B-AR are localized evenly on plasma membranes in nondifferentiated (a) and differentiated (b) PC12α2B cells, and no concentration of staining into the tips of neural processes is seen (arrows). When α2B-AR are expressed in PC12α2A cells (PC12α2A-B), the α2B-AR are targeted into the growth cones and neural processes (c) (arrows), and overlapping staining can be seen with α2A-AR (d). The expression of α2A-AR in PC12α2B cells (PC12α2B-A) induced differentiation-like morphological changes and similar targeting of α2B-AR (e) and α2A-AR (f) into the tips (arrows) of developed neural processes.

To examine the possibility that extensive membrane ruffling in neural extensions of PC12 cells would create the image of receptor concentration, we prepared electron microscopic samples of PC12 cell neural extensions. Prominent membrane ruffling was seen in many growth cones and shorter extensions (average length in slice, 5.8 μm), but in longer extensions (average length in slice, 18.8 μm), similar to the neurite tips in which receptor concentration was observed, no apparent membrane ruffling was seen, indicating that the concentration of α2-AR-specific staining in the tips of neural extensions was not an artifact induced by membrane ruffling.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the subcellular distribution of human α2-AR subtypes in neuronal cells, because α2-ARs are widely distributed in the brain and spinal cord and in peripheral sympathetic nerve cells and because the elucidation of their targeting and trafficking properties might provide important information about their function and regulation (Nicholas et al., 1996; Koenig and Edwardson, 1997). As a neuronal cell type, we used PC12 cells, which are derived from a rat pheochromocytoma tumor (Greene and Tischler, 1976) and are often used as a model of postganglionic sympathetic neurons (Lee et al., 1977; Youdim et al., 1986).

Receptor subtype-specific differences were demonstrated in the subcellular localization of transfected human α2-AR subtypes in differentiating neuronal cells; α2A-AR were distinctly targeted to the tips of the neural extensions, and both α2A- and α2B-AR were internalized after receptor activation. The results also show that expression of α2A-AR induced differentiation-like changes in PC12 cell morphology and growth type, which also permitted targeting of α2B-AR to the tips of the neural extensions.

The predominant α2-AR subtype in the brain and spinal cord is the α2A-AR (MacDonald et al., 1997; Lawhead et al., 1992; Nicholas et al., 1993), which mediates the hypnotic, sedative, sympatholytic, as well as analgesic, effects of α2-AR activation (MacMillan et al., 1996;Lakhlani et al., 1997; Sallinen et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997). In major noradrenergic nuclei of the rat brain, α2A-mRNA is present in the cell bodies, which suggests that α2A-AR are presynaptic autoreceptors, mediating inhibition of synaptic norepinephrine release (Scheinin et al., 1994). The α2A-AR immunoreactivity in the brain is found on presynaptic axons and also in perikarya in which it is localized within intracellular structures involved in synthesis and trafficking of receptors (Milner et al., 1999). The CNS functions of α2B-AR are still unknown (MacDonald et al., 1997) and α2C-AR are thought to have modulatory effects on several different brain functions, e.g., sensorimotor integration (MacDonald et al., 1997;Sallinen et al., 1997, 1998a,b).

This study shows that, during PC12 cell differentiation, α2A-AR are targeted to the developing neurites, concentrating into their tips, directed by functional changes induced by this receptor. This indicates that α2A-AR have properties that enable the intracellular machinery of the cell to induce differentiation and to allow membrane-bound receptors to be transported along the neurites to the site of autoreceptor action. The targeting of α2A-AR to the tips of the neurites during neuronal differentiation resembles that of the G-protein isoform Go, which mediates α2-adrenergic inhibition of neurotransmitter release. Also, Go-proteins are targeted to the growth cones, filopodia, and the tips of neurites during NGF-induced differentiation of PC12 cells (Zubiaur and Neer, 1993). On the contrary, in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, transfected α2A-AR have been shown to be targeted to the basolateral surface, which is thought to correspond to the somatodendritic parts of neuronal cells (Keefer et al., 1994). It was, however, recently shown that trafficking of α2A-AR in neurons could be predicted based on the trafficking of the endogenous apically expressed α2A-AR in MDCK cells (Okusa et al., 1994). All α2-AR subtypes were localized in the cell bodies and along neurites when transfected into cultured primary spinal cord neurons (Wozniak and Limbird, 1998). In our study, using a model of peripheral postganglionic neurons, the distinct targeting of α2-AR subtypes in PC12 cells was found to be secondary to the functional changes induced by α2A-AR in these cells. The distinct targeting of α2A-AR gives evidence of the neuronal autoreceptor-like character of human α2A-AR in peripheral sympathetic neurons, because α2B-AR were evenly distributed in the plasma membrane and α2C-AR were mainly intracellular when expressed in PC12 cells without α2A-AR. This is in line with previous studies on non-neuronal cell types; in nonpolarized fibroblasts (von Zastrow et al., 1993; Daunt et al., 1997) and in polarized epithelial cells (Wozniak and Limbird, 1996), α2A- and α2B-AR resided primarily in the plasma membrane, whereas a large proportion of α2C-AR was found in the endoplasmic reticulum and in cis/medial Golgi.

The mechanisms mediating targeting of receptors and other membrane-associated proteins in nerve cells are not fully understood. Mutagenesis studies of α2A-AR have shown that the direct delivery of this receptor to the basolateral membrane in polarized MDCK cells most likely involves transmembranous structures and that the third cytoplasmic loop of the receptor probably contains structural elements important for the stabilization of the receptor in its subcellular locus (Keefer et al., 1994; Saunders et al., 1998). Synaptic proteins, e.g., postsynaptic density-95/synapse-associated protein 90 (PSD-95/SAP90), participate in targeting of many membrane-associated neuronal proteins (Kim et al., 1995; Kornau et al., 1995). The roles of these and other proteins in targeting the adrenergic α2-receptors remain to be demonstrated.

Subtype-specific desensitization properties of α2-AR have been reported. In Chinese hamster ovary and COS cells, both α2A- and α2B-AR are effectively desensitized by phosphorylation, whereas α2C-AR are not (Eason and Liggett 1992, 1993; Kurose and Lefkowitz, 1994). In a study on transfected human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK-293) cells, extensive agonist-induced internalization of mouse α2B-AR was observed, whereas very limited internalization of mouse α2A-AR was detected by ELISA but not by immunofluorescent methods (Daunt et al., 1997). This suggested that α2A-AR internalization may occur by a nonendosomal mechanism, different from α2B-AR internalization. In this study, we could visualize extensive internalization of human α2A-AR after agonist-induced activation of the receptors in both nondifferentiated and differentiated PC12 cells. This emphasizes the importance of the cellular environment for receptor function. The neuronal, adrenergic PC12 cells contain an as yet unknown machinery that makes the rapid agonist-induced internalization of α2A-AR possible. Internalization of this α2-AR subtype may subserve some important regulatory function in neuronal cells not observed in some other types of cells. The extensive internalization of α2B-AR observed in this study has also been reported in other cell types (Daunt et al., 1997). No α2C-AR internalization was visualized in this study, because this receptor was mainly localized intracellularly already at baseline, and a further reduction in the small plasma membrane α2C-AR population would not have been detectable.

A recent study of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors coexpressed in HEK-293 cells showed receptor subtype-specific endocytosis by distinct mechanisms (Vickery and von Zastrow, 1999). When coexpressing α2A- and α2B-AR in the same PC12 cells, the receptor subtypes were seen in partly separate populations of intracellular vesicles (Fig. 3), indicating partly distinct endocytotic mechanisms. The intracellular vesicles containing α2-AR subtypes could also be in different stages of the endocytotic cycle, suggesting that the kinetics of internalization would differ between the α2-subtypes.

In the present study, PC12 cells acquired morphological features dependent on the transfected α2-AR subtype; especially expression of the α2A-AR subtype clearly altered their morphology. The human α2A-AR is known to control actin polymerization and focal adhesion assembly in preadipocytes but only after agonist stimulation of overexpressed α2A-AR or by constitutively active α2A-AR (Betuing et al., 1996). Overexpression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II has also resulted in altered PC12 cell growth and morphology (Masse and Kelly, 1997). Morphological changes of PC12 cells will not, however, happen along with expression of any protein at densities above physiological levels because, in this study, only PC12α2A cells presented marked morphological differentiation-like changes, despite similar receptor densities. The morphological changes induced by α2A-AR expression were not inhibited by α2-AR antagonist treatment, which indicates that the change is not induced by α2A-AR activation by norepinephrine produced and released by the cells. The morphological changes were seen in all PC12α2A clones expressing α2A-AR above the level of 500 fmol/mg protein, and the changes were more pronounced in cell clones with higher receptor densities. Therefore, it seems unlikely that our results were attributable to selecting G418-resistant PC12 clones that simply were more efficient in differentiation. The differentiating effect of α2A-AR could be repeated with the expression of α2A-AR in PC12α2Bcells; the morphology of these PC12α2B-A cells became similar to that of PC12α2A cells. The mechanism of subtype-specific morphological change of PC12α2A cells remains unclear, but constitutive activity of the transfected α2A-AR is one possible mechanism mediating this effect.

The human α2A-AR was described to induce membrane ruffling of preadipocytes (Betuing et al., 1996). To avoid misinterpretations of receptor localization induced by immunocytochemical staining of the ruffled plasma membrane, electron microscopy of PC12α2A-Band PC12α2B-A cells was performed. Membrane ruffling was detected in growth cones and short neural extensions but not in longer extensions. The concentration of α2A-specific immunocytochemical staining seen in the long neural extensions is therefore not induced by membrane ruffling. Also, the concentrated staining of the neural tips in thin slices of confocal images in Figure 3 confirms this observation.

The specific targeting of α2A-AR to developing nerve terminals indicates that its localization is appropriate for an autoreceptor. Extensive internalization of α2A-AR was observed in nondifferentiated and differentiated sympathetic neuron-like cells, which indicated different sequestration of this receptor in PC12 cells compared with some non-neuronal cell types. The significance of this difference for functional α2A-AR desensitization is still unknown. These present results point out the importance of the cellular environment for receptor endocytosis and trafficking.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, Turku Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Turku University Hospital, and the Technology Development Centre of Finland. We thank Brian Kobilka for antibodies, Thomas Bymark for expert assistance with confocal microscopy, Anne Marjamäki and Katariina Pohjanoksa for help with the expression constructs of human α2-AR, Lauri Pelliniemi for guidance in electron microscopy, Eero Castrén for valuable comments regarding this manuscript, and Anna-Mari Pekuri, Annele Sainio, and Ulla Uoti for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Mika Scheinin, Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Turku, FIN-20520 Turku, Finland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betuing S, Daviaud D, Valet P, Bouloumie A, Lafontan M, Saulnier-Blache JS. α2-Adrenoceptor stimulation promotes actin polymerization and focal adhesion in 3T3F442A and BFC-1β preadipocytes. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5220–5229. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CA, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CA, Okayama H. Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer: a highly efficient transfection system for stably transforming cells with plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 1988;6:632–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chruscinski AJ, Link RE, Daunt DA, Barsh GS, Kobilka BK. Cloning and expression of the mouse homolog of the human α2-C2 adrenergic receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:1280–1287. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daunt AD, Hurt C, Hein L, Kallio J, Feng F, Kobilka BK. Subtype-specific intracellular trafficking of α2-adrenergic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:711–720. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eason MG, Liggett SB. Subtype-selective desensitization of α2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25473–25479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eason MG, Liggett SB. Functional α2-adrenergic receptor-Gs coupling undergoes agonist-promoted desensitization in a subtype-selective manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:318–323. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene LA, Tischler AS. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene LA, Sobeih MM, Teng KK. Methodologies for the culture and experimental use of the PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cell line. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing nerve cells. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1991. pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halme M, Sjöholm B, Savola J-M, Scheinin M. Recombinant human α2-adrenoceptor subtypes: comparison of [3H]rauwolscine, [3H]atipamezole and [3H]RX821002 as radioligands. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1266:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(95)90410-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karnovsky MJ. Use of ferrocyanide-reduced osmium tetroxide in electron microscopy. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Cell Biology. 1971.

- 12.Keefer JR, Kennedy ME, Limbird LE. Unique structural features important for stabilization versus polarization of the α2A-adrenergic receptor on the basolateral membrane of Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16425–16433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim E, Niethammer M, Rothschild A, Jan YN, Sheng M. Clustering of Shaker-type K+ channels by interaction with a family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. Nature. 1995;378:85–88. doi: 10.1038/378085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobilka BK, Matsui H, Kobilka TS, Yang-Feng TL, Francke U, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Regan JW. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene coding for the human platelet α2-adrenergic receptor. Science. 1987;238:650–656. doi: 10.1126/science.2823383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Endocytosis and recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:276–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science. 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurose H, Lefkowitz RJ. Differential desensitization and phosphorylation of three cloned and transfected α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10093–10099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakhlani PP, MacMillan LB, Guo TZ, McCool BA, Lovinger DM, Maze M, Limbird LE. Substitution of a mutant α2a-adrenergic receptor via “hit and run” gene targeting reveals the role of this subtype in sedative, analgesic, and anesthetic-sparing responses in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanier SM, Downing S, Duzic E, Homcy CJ. Isolation of rat genomic clones encoding subtypes of the α2-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10470–10478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawhead RG, Blaxall HS, Bylund DB. α2A is the predominant α2 adrenergic receptor subtype in human spinal cord. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:983–991. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199211000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee V, Shelanski ML, Greene LA. Specific neural and adrenal medullary antigens detected by antisera to clonal PC12 and pheochromocytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5021–5025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee VM, Shelanski ML, Greene LA. Characterization of antisera raised against cultured rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1980;5:2239–2245. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liitti S, Närvä H, Marjamäki A, Hellman J, Kallio J, Jalkanen M, Matikainen MT. Subtype specific recognition of human alpha2C2 adrenergic receptor using monoclonal antibodies against the third intracellular loop. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:166–172. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Link R, Daunt D, Barsh G, Chruscinski A, Kobilka BK. Cloning of two mouse genes encoding α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes and identification of a single amino acid in the mouse α2C10 homolog responsible for an interspecies variation in antagonist binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:16–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Link RE, Desai K, Hein L, Stevens ME, Chruscinski A, Bernstein D, Barsh GS, Kobilka BK. Cardiovascular regulation in mice lacking α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes B and C. Science. 1996;273:803–805. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomasney JW, Lorenz W, Allen LF, King K, Regan JW, Yang-Feng TL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Expansion of the α2-adrenergic receptor family: cloning and characterization of a human α2-adrenergic receptor subtype, the gene for which is located on chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5094–5098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacDonald E, Kobilka BK, Scheinin M. Gene targeting—homing in on α2-adrenoceptor subtype function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:211–219. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacMillan LB, Hein L, Smith MS, Piascik MT, Limbird LE. Central hypotensive effects of the α2a-adrenergic receptor subtype. Science. 1996;373:801–803. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marjamäki A, Ala-Uotila S, Luomala K, Perälä M, Jansson C, Jalkanen M, Regan JW, Scheinin M. Stable expression of recombinant human α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in two mammalian cell lines: characterization with [3H]rauwolscine binding, inhibition of adenylate cyclase and RNase protection assay. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1134:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marjamäki A, Luomala K, Ala-Uotila S, Scheinin M. Use of recombinant human α2-adrenoceptors to characterize subtype selectivity of antagonist binding. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;246:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masse T, Kelly PT. Overexpression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in PC12 cells alters cell growth, morphology, and nerve growth factor-induced differentiation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:924–931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00924.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCune SK, Voigt MM, Hill JM. Expression of multiple alpha adrenergic receptor subtype messenger RNAs in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 1993;57:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90116-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milner TA, Rosin DL, Lee A, Aicher SA. Alpha2A-adrenergic receptors are primarily presynaptic heteroreceptors in the C1 area of the rat rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Res. 1999;821:200–211. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholas AP, Pieribone V, Hökfelt T. Distributions of mRNAs for alpha-2 adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1993;328:575–594. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholas AP, Hökfelt T, Pieribone VA. The distribution and significance of CNS adrenoceptors examined with in situ hybridization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okusa MD, Lynch KR, Rosin DL, Huang L, Wei YY. Apical membrane and intracellular distribution of endogenous alpha2A-adrenergic receptors in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F347–F353. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.3.F347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regan JW, Kobilka TS, Yang-Feng TL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Kobilka BK. Cloning and expression of human kidney cDNA for an adrenergic receptor subtype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6301–6305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosin DL, Zeng D, Stornetta RL, Norton FR, Riley T, Okusa MD, Guyenet PG, Lynch KRN. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha2A-adrenergic receptors in catecholaminergic and other brainstem neurons in the rat. Neuroscience. 1993;56:139–155. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosin DL, Talley EM, Lee A, Stornetta RL, Gaylinn BD, Guyenet PG, Lynch KR. Distribution of α2C-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:135–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960812)372:1<135::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sallinen J, Link RE, Haapalinna A, Viitamaa T, Kulatunga M, Sjöholm B, MacDonald E, Pelto-Huikko M, Leino T, Barsh GS, Kobilka BK, Scheinin M. Genetic alteration of alpha 2C-adrenoceptor expression in mice: influence on locomotor, hypothermic, and neurochemical effects of dexmedetomidine, a subtype-nonselective alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:36–46. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallinen J, Haapalinna A, Viitamaa T, Kobilka BK, Scheinin M. d-Amphetamine and l-5-hydroxytryptophan-induced behaviours in mice with genetically altered expression of the α2C-adrenergic receptor subtype. Neuroscience. 1998a;86:959–965. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallinen J, Haapalinna A, Viitamaa T, Kobilka BK, Scheinin M. Adrenergic α2C-receptors modulate the acoustic startle reflex, prepulse inhibition and aggression in mice. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:3035–3042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03035.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders C, Keefer JR, Bonner CA, Limbird LE. Targeting of G-protein-coupled receptors to the basolateral surface of polarized renal epithelial cells involves multiple, non-contiguous structural signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24196–24206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheinin M, Lomasney JW, Hayden-Hixson DM, Schambra UB, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Fremeau RT., Jr Distribution of α2-adrenergic receptor subtype gene expression in rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;21:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stempak JG, Ward RT. An improved staining method for electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1964;22:697–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.22.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stone LS, MacMillan LB, Kitto KF, Limbird LE, Wilcox GL. The α2a adrenergic receptor subtype mediates spinal analgesia evoked by α2 agonists and is necessary for spinal adrenergic-opioid synergy. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7157–7165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07157.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talley EM, Rosin DL, Lee A, Guyenet PG, Lynch KR. Distribution of alpha 2A-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:111–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960812)372:1<111::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venable JH, Coggeshall R. A simplified lead citrate stain for use in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1965;25:407–408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.25.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vickery RG, von Zastrow M. Distinct dynamin-dependent and -independent mechanisms target structurally homologous dopamine receptors to different endocytic membranes. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:31–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Zastrow M, Link R, Daunt D, Barsh D, Kobilka B. Subtype-specific differences in the intracellular sorting of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:763–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang RX, MacMillan LB, Fremeau RT, Jr, Magnuson MA, Linder J, Limbird LE. Expression of alpha2-adrenergic receptor in the mouse brain: evaluation of spatial and temporal information imported the 3 kb of 5′ regulatory sequence for the α2-adrenergic receptor gene in transgenic animals. Neuroscience. 1996;74:199–218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winzer-Serhan UH, Leslie FM. Alpha 2B adrenoceptor mRNA expression during rat brain development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;100:90–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wozniak M, Limbird LE. The three α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes achieve basolateral localization in Madin-Darby canine kidney II cells via different targeting mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5017–5024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wozniak M, Limbird LE. Trafficking itineraries of G protein-coupled receptors in epithelial cells do not predict receptor localization in neurons. Brain Res. 1998;780:311–322. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youdim MB, Heldman E, Pollard HB, Fleming P, McHugh E. Contrasting monoamine oxidase activity and tyramine induced catecholamine release in PC12 and chromaffin cells. Neuroscience. 1986;19:1311–1318. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng DW, Harrison JK, D'Angelo DD, Barber CM, Tucker AL, Lu ZH, Lynch KR. Molecular characterization of a rat α2B-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3102–3106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zubiaur M, Neer EJ. Nerve growth factor changes G protein levels and localization in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:207–217. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]