Abstract

The weaver (wv) gene has been identified as a glycine to serine substitution at residue 156 in the H5 region of inwardly rectifying K+ channel, GIRK2. The mutation is permissive for the expression of homotetrameric channels that are nonselective for cations and G-protein-independent. Coexpression of GIRK2wv with GIRK1, GIRK2, or GIRK3 inXenopus oocytes along with expression of subunit combinations linked as dimers and tetramers was used to investigate the effects of the pore mutation on channel selectivity and gating as a function of relative subunit position and number within a heterotetrameric complex. GIRK1 formed functional, K+ selective channels with GIRK2 and GIRK3. Coexpression of GIRK2wv with GIRK1 gave rise to a component of K+-selective, G-protein-dependent current. Currents resulting from coexpression of GIRK2wvwith GIRK2 or GIRK3 were weaver-like. Current from dimers of GIRK1-GIRK2wv, GIRK2-GIRK2wv, and GIRK3-GIRK2wv was phenotypically similar to that obtained from coexpression of monomers. Linked tetramers containing GIRK1 and GIRK2wv in an alternating array gave rise to wild-type, K+-selective currents. When two mutant subunits were arranged adjacently in a tetramer, currents wereweaver-like. These results support the hypothesis that in specific channel stoichiometries, GIRK1 rescues theweaver phenotype and suggests a basis for the selective neuronal vulnerability that is observed in the weavermouse.

Keywords: K+ channels, weaver mice, G-proteins, Xenopusoocytes, voltage clamp, neurons

Members of the family of G-protein activated, inwardly rectifying K+channels, GIRK1–5, have been cloned and characterized in a number of heterologous expression systems (Kubo et al., 1993a; Dascal, 1997; Jan and Jan, 1997a) where their activity is similar to that characterized in native heart and nerve cells (Dascal et al., 1993; Kofuji et al., 1995; Krapivinsky et al., 1995; Lesage et al., 1995). Functional recombinant channels are assumed to assemble as heterotetrameric polypeptides usually formed through the interaction of GIRK1 with either GIRK2 or GIRK3 in the brain, or GIRK4 in the atrium of the heart (Lesage et al., 1994; Kofuji et al., 1995; Krapivinsky et al., 1995;Lesage et al., 1995). The single amino acid mutation in the K+ channel signature sequence in the P region of GIRK2 (G156S) identified in the weaver mouse (Patil et al., 1995) has been shown to result in a constitutive Na+ conductance after heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes (Kofuji et al., 1996; Navarro et al., 1996; Slesinger et al., 1996) and mammalian cells (Navarro et al., 1996).

The weaver phenotype has provided a classic paradigm for developmental neurobiology and also serves as a model system for studying neurodegenerative disease (Rakic and Sidman, 1973; Schmidt et al., 1982; Hatten et al., 1984; Goldowitz, 1989; Smeyne and Goldowitz, 1989; Graybiel et al., 1990; Gao and Hatten, 1993; Bayer et al., 1995;Goldowitz and Smeyne, 1995; Patil et al., 1995; Hess, 1996; Migheli et al., 1997). In this study, we demonstrate that rescue of theweaver phenotype may involve formation of heteromultimeric channels between mutant GIRK2wv subunits and wild-type GIRK1 subunits that function normally. Heteromultimeric channels between mutant GIRK2wv subunits and GIRK2 or 3 retain theirweaver phenotype. Therefore, susceptibility to cell death among different populations of neurons in the brain may result from differences in expression of GIRK subunit isoforms among the different neuronal populations.

We undertook these studies in an attempt to explore the functional relationships between GIRK channel subunits. Because GIRK2 is ubiquitously expressed in the brain, we reasoned that insight into interaction of both the wild-type GIRK2 and the mutant GIRK2wv subunit might suggest a mechanistic basis for the selective loss of a subset of cerebellar as well as substantia nigra neurons in the weaver mouse (Surmeier et al., 1996). GIRK1/GIRK2wv heteromultimeric currents are G-protein-dependent and K+-selective in contrast to GIRK2/GIRK2wv or GIRK3/GIRK2wvheteromultimeric channels, which retain the characteristic nonselective, G-protein-independent weaver phenotype. Tandem-linked tetramers containing GIRK1 and GIRK2wvsubunits in an alternating array formed functional K+-selective, G-protein-dependent channels. When two mutant subunits were arranged adjacent in a tetramer, resultant expressed currents were weaver-like. In summary, these data suggest that susceptibility to cell death among different types of neurons may result from differences in expression of GIRK subunit isoforms available for heteromultimer formation among the different neuronal populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA clone. GIRK1 was cloned from a rat insulinoma tumor cell (RIN) library and has a predicted amino acid sequence identical to the cardiac clone originally described (Kubo et al., 1993b); GIRK2 and GIRK2wv, GIRK3, and GIRK5, were generous gifts from Drs. P. Kofuji (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), A. Karschin (Max-Planck-Institute, Göttingen, Germany), and D. Clapham (Children’s Hospital/Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston, MA), respectively. The m2 muscarinic receptor was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) in the pGEM3Z vector. All GIRK constructs were subcloned into the pMXT vector, obtained from Dr. P. Kofuji (California Institute of Technology). The m2 receptor was linearized with HindIII, and cRNA was transcribed using the T7 polymerase mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). All GIRK constructs were linearized with SalI, and cRNA was transcribed using T3 polymerase mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). The cRNA concentration was determined by UV absorption (A260) and confirmed by intensity on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels.

Multimeric GIRK constructs. To allow simple construction of a variety of multimers, we followed an approach previously described bySilverman et al. (1996b). Two new unique restriction enzyme sites were introduced by PCR in GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 at both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the coding sequences, such that digestion with appropriate restriction enzymes would provide compatible overhangs between the 3′ end of one coding sequence and the 5′ end of the other. GIRK1, with 5′ClaI and 3′ XbaI sites, was ligated to GIRK2 or GIRK2wv with 5′ XbaI and 3′ NotI sites, which allowed construction of the GIRK1–2 and GIRK1–GIRK2wv dimer sequences. Ligation of GIRK2 or GIRK3 with 5′ ClaI and 3′ XbaI sites to GIRK2wv with 5′ XbaI and 3′ NotI sites resulted in GIRK2-GIRK2wv or GIRK3-GIRK2wv dimer sequences. Two new residues (serine and arginine) were introduced at the junctions within all the dimers. The dimer sequences were subcloned into pMXT vector at the ClaI and NotI multiple cloning sites. The primers were synthesized at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL). Primer sequences were as follows: GIRK1, 5′ ClaI, GCGCATCGATATGTCTGCACTCCGAAGG; GIRK1, 3′ XbaI, TGC TCTAGACTGCAGGGACCCCTC; GIRK2, 5′ ClaI, GCGCGCATCGATATGACAATGGCCAA; GIRK2, 3′ XbaI, TGCTGCTCTAGACCCATTCCTCTCC; GIRK2, 5′ XbaI, CGCGGCTCTAGAATGACAATGGCCAA; GIRK2, 3′ NotI, AATATTGCGGCCGCTCACCCATTAATC; GIRK2wv, 5′ XbaI, CGCGGCTCTAGAATGACAATGGCCAA; GIRK2wv, 3′ NotI, AATATTGCGGCCGCTCACCCATTAATC; GIRK3, 5′ ClaI, GCGCATCGATATGGCGCAGGAGAACGC; and GIRK3, 3′ AvrII, TATATACCTAGGGCTCCATCTCCTGCG.

The linked heterotetramers, GIRK1-GIRK2wv-GIRK1-GIRK2wv(1-wv-1-wv) and GIRK1-GIRK1-GIRK2wv-GIRK2wv(1–1-wv-wv), were constructed by removing the stop codons of the dimeric constructs GIRK1-GIRK2wv(1-wv) and GIRK1-GIRK1 (1–1) in pMXT vector using site-directed mutagenesis (Promega, Madison, WI) while introducing a new NarI restriction enzyme site. The 1-wv orwv-wv dimers with and 3′ NotI sites were linked to 1-wv or 1–1 dimers at NarIand NotI sites. The primers were synthesized at Operon (Alameda, CA). Primer sequences were as follows: 1-wv NarI, GGCGGCGGCGCCCCCATTCCTCTCCGTCAGTTCTT; and 1–1 NarI, TAACCAGATCCGCGGTGGCGGCGGCGCCCTGCAGGGA.

The junction sequences of all linked constructs were verified by automated fluorescent cycle sequencing (DNA Sequencing Facility at The University of Chicago Cancer Research Center).

Oocyte preparation and injection. Oocytes were removed fromXenopus laevis as described (Yoshii and Kurihara, 1989) and maintained at 18°C in OR-2+ solution that was changed once daily. The OR-2+ solution contained (in mm) 90 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, and 5 HEPES, supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamycin and 5 mm pyruvate, pH 7.6. Oocytes injected with GIRK2wv cRNA were incubated in Ca2+-free OR-2+ solution, which has been shown to enhance cellular survival by preventing possible swelling and Ca2+ overload (Silverman et al., 1996a). In those experiments investigating the effects of free Gβγ on basal current activity, oocytes were maintained in a high glucose (5 mm)-containing solution. Oocytes were injected with 50 nl containing constant amounts of each single subunit cRNA (∼5 ng), m2 receptor (∼2.5 ng) together with 12.5 ng of fully phosphothiolated GIRK5 antisense oligonucleotide KHA1 (5′-CTGAGGACTTGGTGCCATTCT-3′) prepared at HHMI.

Electrophysiology. Two-electrode voltage recordings were performed 2–3 d after injection at room temperature using a TURBO TEC-10C amplifier (NPI, Tamm, Germany), ITC-16 interface (Instrutech, Great Neck, NY), and IBM-compatible PC. Microelectrodes were filled with 3 m KCl and had resistances of 0.5–2 MΩ. Oocytes were continuously superfused with a bath solution of 90 mm NaCl or KCl, 1 mmMgCl2, and 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, with NaOH/KOH. G-protein-dependent currents were induced with the addition of 5 μm carbachol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to the bath solution. In all experiments, the holding potential was −80 mV; test potentials were delivered once every second and stepped between −150 and 50 mV in intervals. Data collection and analysis were performed using Pulse/Pulse Fit (Heka, Lambrecht, Germany), and data were plotted using the integrated graphics package Igor (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Data are presented as mean ± SEM with the number of oocytes in parentheses. All experiments were conducted at room temperature.

Gsα protein purification. Expression of the N-terminal hexohistidine-tagged short form of Gsα was performed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) that carried pUBS520 and H6-pQE60-Gsα grown to cell density of OD 600 = 0.4 at 30°C and induced by adding IPTG and chloramphenical to a final concentration of 30 and 1 μm, respectively. The expression of dna Y from pUBS520 enhanced Gsα expression threefold to fourfold. After a 19 hr induction period, E. coli were harvested and lysed; Gsα was purified using the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) and FPLC Q-Sepharose column as described (Lee et al., 1994). Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE was used to determine the protein peak in the fractions eluted from the Q-Sepharose column. The purified Gsα was concentrated by pressure filtration using an Amicon 30 filter and centricon, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford reagent and bovine serum albumin as a standard (Bradford, 1976).

RESULTS

Coexpression of monomeric GIRK subunits inXenopus oocytes

Expression of recombinant GIRK channels was studied inXenopus oocytes after injection of GIRK1, GIRK2, GIRK3, and GIRK5 subunit cRNA or combinations of two isoforms along with m2, muscarinic receptor cRNA. In all experiments, G-protein-independent (basal) as well as G-protein-dependent (carbachol-induced) currents were recorded in solutions containing 90 mmK+. Currents were recorded at 36–72 hr after injection. Experiments were replicated in at least three batches of oocytes.

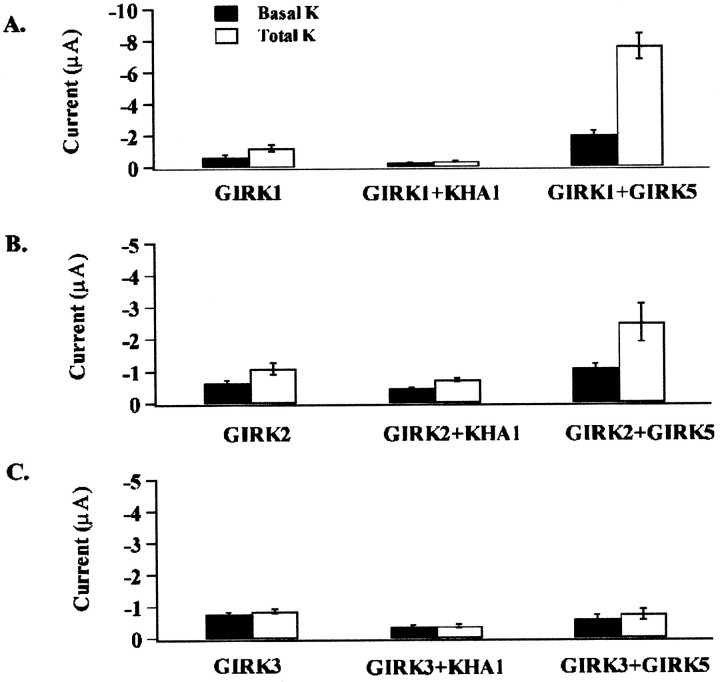

Recombinant GIRK subunits coassemble with endogenous XenopusGIRK5 subunits to form functional channels (Hedin et al., 1996). Antisense against GIRK5 (KHA1) has been previously reported to knock out endogenous GIRK5 expression in oocytes (Silverman et al., 1996b). We conducted experiments to compare levels of homomeric GIRK subunit expression in the presence and absence of coinjected antisense against GIRK5. In addition, we examined the synergistic enhancement of homomeric GIRK subunit expression in the presence of coexpressed GIRK5. Data comparing carbachol-induced current amplitude to basal current amplitude in high K+ solutions for GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 are summarized in Table1. Current expression is synergistically enhanced for GIRK1 and GIRK2 isoforms in the presence of the endogenousXenopus subunit GIRK5 and reduced in the presence of antisense against GIRK5 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Homomeric expression of GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 is inhibited in the presence of antisense to GIRK5 and synergistically enhanced when coexpressed with cloned GIRK5

| Coexpression experiment | Homomultimeric current expression at −150 mV (in μA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIRK1 | GIRK2 | GIRK3 | ||||

| Basal | Icarb | Basal | Icarb | Basal | Icarb | |

| Control | 0.64 ± 0.15 (8) | 0.53 ± 0.09 (8) | 0.66 ± 0.07 (10) | 0.44 ± 0.13 (10) | 0.76 ± 0.07 (15) | 0.09 ± 0.04 (15) |

| GIRK5 antisense | 0.24 ± 0.02 (6) | 0.10 ± 0.02 (6) | 0.46 ± 0.03 (5) | 0.28 ± 0.03 (5) | 0.35 ± 0.06 (6) | 0.02 ± 0.02 (6) |

| GIRK5 | 1.95 ± 0.26 (8) | 5.64 ± 0.79 (8) | 1.07 ± 0.14 (11) | 1.50 ± 0.54 (11) | 0.55 ± 0.12 (7) | 0.19 ± 0.1 (7) |

All oocytes were coinjected with the muscarinic receptor m2 as described in Materials and Methods. Peak currents were measured at −150 mV and averaged. The G-protein-dependent current was determined as the difference between the current determined in the presence of 5 μm carbachol added to the bath solution minus the current determined in the absence of carbachol stimulation. The number of oocytes for each experimental condition is given in parentheses. Currents were recorded in solutions in which all the Na+was osmotically replaced with K+.

Fig. 1.

G-protein-dependent and independent K+ current activation in oocytes injected with cRNA for GIRK1, 2, and 3 as well as combinations of GIRK1, GIRK2, or GIRK3 with GIRK5 or antisense for GIRK5. Currents were recorded using a two-microelectrode voltage clamp from oocytes injected with cRNA for the m2 muscarinic receptor, GIRK1, 2, 3, and 5, and GIRK5 antisense oligonucleotide KHA1, as described in Materials and Methods. Currents were recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV in response to step voltages between −150 and 50 mV in 20 mV increments, the interval between steps was 1 sec. The basal current was determined in a solution in which all the Na+ was isosmotically replaced with K+; G-protein current activation was determined in response to 5 μm carbachol added to the extracellular solution. Bars represent a summary of current data at −150 mV for all subunit combinations recorded 72 hr after injection for both basal K+ and total current (basal plus carbachol-induced in high K+ solutions). Bars represent mean ± SEM measure at −150 mV.

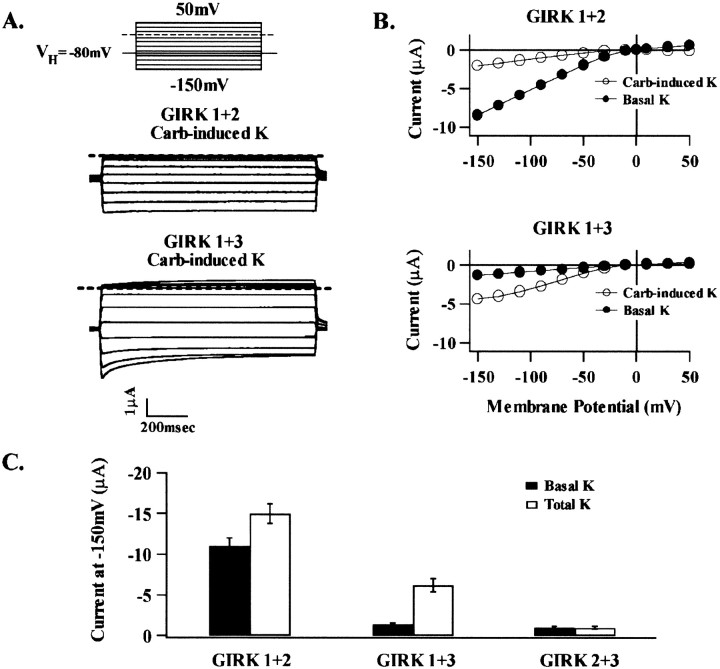

Comparative current amplitudes recorded after coexpression of GIRK1 with GIRK2 or GIRK3 are summarized in Figure2. Coexpression of GIRK2 and GIRK3 failed to result in the formation of functional heteromultimeric channels. Expression of recombinant GIRK1 + GIRK2 and GIRK1 + GIRK3 resulted in both agonist-independent and carbachol-induced currents in high K+ solutions.

Fig. 2.

G-protein-dependent and independent K+ current activation in oocytes injected with cRNA for combinations of GIRK1 + GIRK2 or GIRK 3. Currents in this figure and all succeeding figures were recorded as in Figure 1. The basal current recorded in a solution in which all the Na+was isosmotically replaced with K+; the total current (G-protein-dependent plus independent current) was determined in response to 5 μm carbachol added to the extracellular solution. A, Representative carbachol-induced K+ current from oocytes injected with either GIRK1 + 2 or GIRK 1 + 3, as indicated. B, The corresponding current–voltage (I–V) relationships for the G-protein-independent (Basal) and G-protein-dependent (Carb-induced) currents seen inA. C, Summary of current data at −150 mV for all subunit combinations determined 72 hr after injection for both basal K+ (solid bars) and total current (white bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM based on recordings from 10–40 oocytes taken from at least three batches.

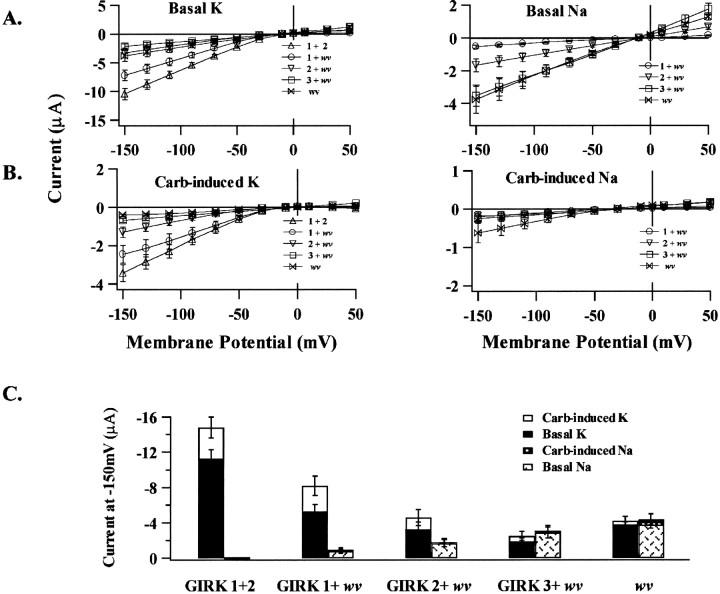

Selectivity of heteromultimeric GIRK2wv channel is controlled by GIRK1 subunit association

To determine whether GIRK2wv forms functional heterooligomers, we performed coexpression experiments with wild-type GIRK1, 2, or 3. GIRK2wv was coinjected at a ratio of 1:1 with wild-type cRNA. The selectivity of both the basal as well as the carbachol-induced current is compared for each of the coexpression studies in Figure 3. When GIRK1 was coexpressed with GIRK2wv, currents resembled those obtained after coexpression of GIRK1 with GIRK2 in that (1) the G-protein-independent current was K+-selective and (2) there was a significant amount of K+-selective carbachol-induced current. When GIRK2 was coexpressed with GIRK2wv, both basal- and carbachol-induced K+ currents were significantly reduced as compared to GIRK1 + GIRK2wv expression. GIRK3 coexpression with GIRK2wv resembled GIRK2wv homomeric currents in that the G-protein-independent component was nonselective, and the carbachol-sensitive component was absent. Data for the GIRK2wv coexpression studies are compared and summarized in Figure 3C.

Fig. 3.

The selectivity of heteromultimeric channels in coexpression experiments using wild-type cRNA for GIRK1, GIRK2, or GIRK3 with GIRK2 wv (wv) is determined by the wild-type coexpressed species. Currents were recorded as in Figure1. A, B, Averaged I–Vrelationships determined for basal- and carbachol-induced currents. Current amplitude was determined 92 msec after the initiation of the voltage pulse. C, Summary of the average current data taken from the experiments in A and B. A total of 10–40 oocytes taken from at least three batches were used for each experimental condition.

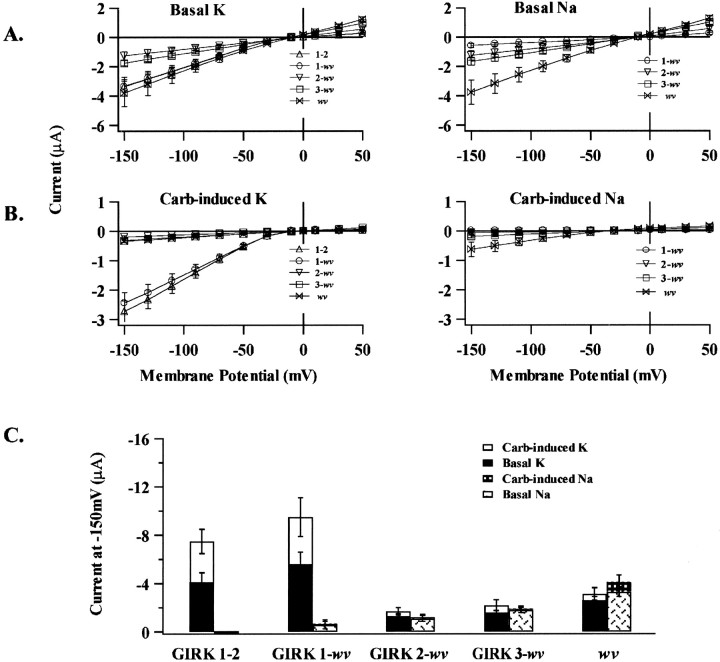

The presence of GIRK1, not the number of wv subunits, determines channel phenotype

The family of GIRK channels appears to form functional tetramers (Dascal, 1997; Jan and Jan, 1997b; Corey et al., 1998). Therefore, functional channels in coexpression experiments may exist in several possible channel stoichiometries. To constrain the possible functional combinations, we constructed and expressed heterodimers containing a GIRK2wv subunit. The selectivity of the heterodimer recombinant currents is shown in Figure4. A comparison of the basal as well as the carbachol-induced current for the dimeric constructs was compared to that obtained for expression of GIRK2wv monomers. We found that the GIRK1-wv dimer showed a phenotypic profile that resembled the wild-type GIRK1–2 dimer currents with respect to (1) an insignificant basal Na+permeability and (2) an equivalent basal- and carbachol-induced K+ current. However, more importantly, both GIRK2-wv and GIRK3-wv dimer constructs gave rise to a basal or G-protein independent Na+ current and no carbachol-induced K+ current, a phenotypic profile that was identical to the GIRK2wv monomeric currents. Each of the dimeric constructs presumably gave rise to tetrameric channels containing two GIRK2wv subunits with two possible stoichiometries where identical subunits were positioned either across from or adjacent to each other. Current phenotypes determined by selectivity as well as G-protein dependence differed according to the wild-type subunit linked to GIRK2wv subunit as summarized in Figure 4C.

Fig. 4.

Expression of dimeric constructs containing wild-type GIRK1, GIRK2, or GIRK3 subunits linked to GIRK2wv (wv) leads to functional channel expression. The presence of GIRK1 in functional channels determined channel selectivity and G-protein dependence. Currents were recorded as in Figure 1. A, B, TheI–V relationships for recombinant channel currents determined 92 msec after the initiation of the voltage pulse for 8–22 oocytes pooled from three batches for each experimental condition.C, Summary of mean current amplitude of the basal- and carbachol-induced currents measured at −150 mV in oocytes expressing indicated dimers.

GIRK2wv subunit stoichiometry and positional effects

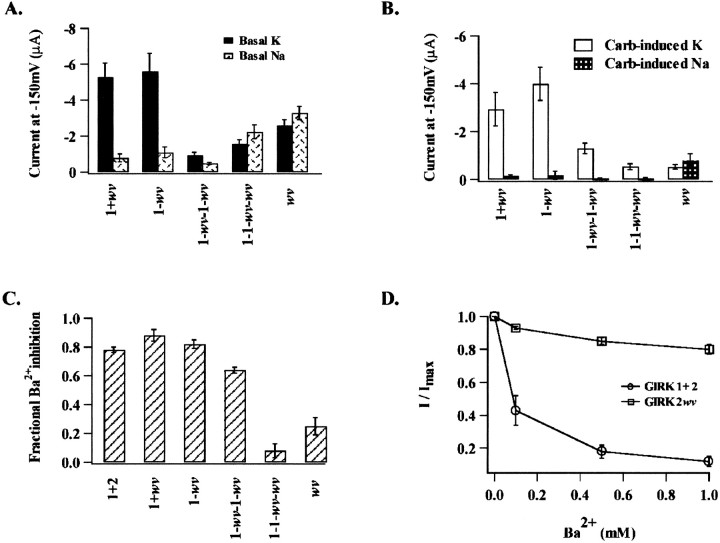

The selectivity and G-protein dependence of the currents obtained from the dimer expression experiments strongly resembled data obtained in the coexpression studies. This may reflect that subunit coassembly may not be random but involve a preferred arrangement around the pore. To date, studies on the stoichiometry of GIRK channels have relied on the formation of multimeric concatemers. This approach has been successfully used to constrain the stoichiometry and relative position of both voltage-gated and inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunits (Liman et al., 1992;Yang et al., 1995; Silverman et al., 1996b; Tucker et al., 1996). Following this approach, we linked GIRK1 and GIRK2wvsubunits into tetrameric constructs. The positional effect of the GIRK2wv subunit was investigated using tetramers that contained two mutant subunits in one of two alternate patterns. Identical subunits were either adjacent (1–1-wv-wv) or linked as an alternating array (1-wv-1-wv). Data obtained from the expression of the tetrameric constructs are compared with data from expression of dimers and coexpression of monomers in Figure5. The basal current for the 1-wv-1-wv tetramer was K+-selective and resembled that obtained for GIRK1 + GIRK2wv coexpression and GIRK1-wvdimer expression. In contrast, the 1–1-wv-wvbasal currents were nonselective and were similar to monomeric GIRK2wv currents (Fig. 5A). The relative amplitude of the carbachol-induced currents in Na+ versus K+containing solutions for all the aforementioned constructs is compared in Figure 5B. The expression of 1-wv-1-wv resulted in a significant G-protein-dependent K+-selective current (−1.3 ± 0.2 μA at −150 mV; n = 16) when compared to that obtained for the 1–1-wv-wvtetramer (-0.6 ± 0.12 μA at −150 mV; n = 12) as seen in Figure 5B. Overall, the expression levels of 1–1-wv-wv were comparable to that obtained for the GIRK2wv homomultimeric current.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of current amplitude for expression of dimeric versus tetrameric constructs. In these experiments, the arrangement of the mutant subunit around the central pore appeared to determine channel selectivity, G-protein dependence, as well as Ba2+ sensitivity. Current means represent an average of >10 oocytes for each experimental condition as indicated in each panel. A, Summary of mean basal current amplitude at −150 mV for each of the experimental conditions as indicated.B, Summary of the mean carbachol-induced current in high Na+ versus high K+ solutions.C, Summary of the fraction the total current in high K+ inhibited by 500 μmBa2+; GIRK1+2 was 0.84 ± 0.02 (15); 1+wv, 0.78 ± 0.01 (10); 1-wv,0.83 ± 0.04 (10); 1-wv-1-wv,0.53 ± 0.03 (16); 1–1-wv-wv,0.11 ± 0.05 (12); and wv, 0.11 ± 0.1 (18).D, Comparison of the fraction of total current in high K+ solutions inhibited at increasing concentrations of external Ba2+ for coexpression of GIRK1 + GIRK2 and GIRK2wv.

The pharmacological sensitivity to block by 500 μmexternal Ba2+ for both concatameric as well as monomeric constructs is compared in Figure 5, C andD. Ba2+ sensitivity is expressed as the fraction of the total current in high K+ solutions (carbachol-sensitive plus insensitive K+-selective current) inhibited after exposure to 500 μmBa2+. Currents obtained after coexpression of GIRK1 with GIRK2wv and the 1-wv-1-wv tetramer maintained their Ba2+ sensitivity. The tetrameric 1–1-wv-wv currents were insensitive to 500 μm Ba2+, similar to GIRK2wv homomultimeric channels. A comparison of the Ba2+ sensitivity for wild-type heteromultimeric GIRK1/GIRK2 and homomultimeric GIRK2wvchannels is given in Figure 5D in which the Ba2+-sensitive current is expressed as a fraction of the total current in high K+solutions.

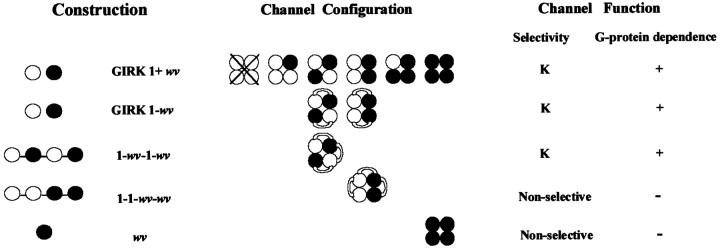

The possible channel stoichiometries in each of the GIRK2wvexpression experiments summarized in Figure 5 are depicted graphically in Figure 6. Note that dimeric GIRK1-GIRK2wv expression could yield two theoretically possible tetrameric stoichiometries. Expression of the linked tetramers, which would give rise to both of the possible stoichiometries, gives currents that are separable on the basis of their G-protein sensitivity and basal Na+conductance. Thus, the sum of the tetrameric currents does not give rise to a current that resembles the currents obtained by expression of the GIRK1-GIRK2wv heterodimer. These results suggest that the tetramer with two adjacent GIRK2wv subunits is not the preferred stoichiometry in the expression of heterodimers.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the possible channel stoichiometries in the coexpression of monomeric subunit cRNA as compared to expression of linked dimers and tetramers. A table summarizing the resultant current selectivity and G-protein dependence for the expressed currents is given to the right of the representative functional channel configurations. The open circles represent the GIRK1 subunit, and the filled circles represent the GIRK2 wv subunit. The abbreviations used in the text to describe the recombinant channel constructs are given to the left of the schematized channels.

Comparative basal activation in high K+ for wild-type GIRK1/GIRK2 channels versus GIRK1-GIRK2wv dimers

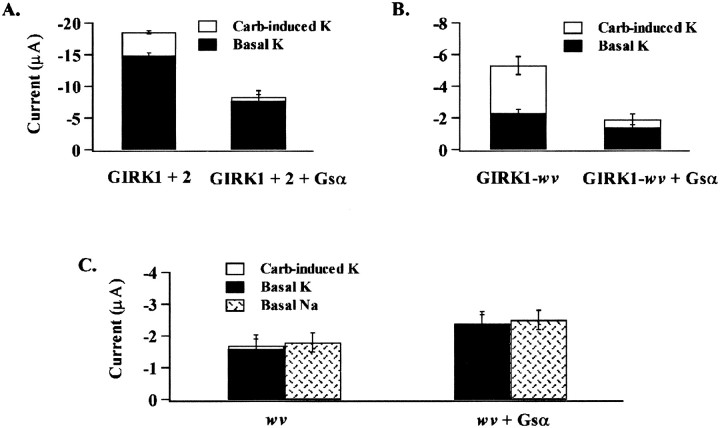

The basal current in high K+solutions was elevated for GIRK1 + GIRK2 heteromultimers (Figs.2C, 3C), for GIRK1 + GIRK2wv (Fig.3C), and for the dimeric construct GIRK1-GIRK2wv(Fig. 4). Such high levels of basal current activation does not occur in isolated neurons expressing GIRK channels (Surmeier et al., 1996;Slesinger et al., 1997; Rossi et al., 1998). It has been proposed that the high levels of basal activation seen with GIRK expression in theXenopus oocyte expression system is a result of high levels of intracellular Na+ (Silverman et al., 1996a) or high levels of free Gβγ (Vivaudou et al., 1997). In that the K+ over Na+ selectivity of the GIRK1/GIRK2wv heteromultimers served as an indicator of wild-type GIRK current, we performed experiments to determine if basal K+ current of channels containing the mutant subunit were differentially sensitive to free Gβγ. Oocytes expressing either GIRK1 + GIRK2, the dimer GIRK1-GIRK2wv, or GIRK2wv were examined for current expression 36 hr after cRNA injection. Oocytes were maintained in solutions in high glucose (5 mm), low K+ (2.5 mm) solutions. Recordings were made in solutions in which all the Na+ was replaced with either the large impermeant cation N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) or 90 mm K+. Approximately 30 min before recording, half of the oocytes were injected with 50 nl of purified Gsα (40 μg/μl) to serve as a Gβγ sink. The amplitude of the basal- and carbachol-induced current amplitude was compared for all the constructs and is summarized in Figure7. Na+-selective currents were also determined for the GIRK2wv homomultimeric currents. The GIRK2wv homomultimeric currents were unchanged in the presence of Gsα. The GIRK1 + GIRK2 currents as well GIRK1-GIRK2wv dimer currents responded to injection of the Gsα by a significant decrease in the carbachol-induced current and a more modest decrease in the basal current. Thus, the two heteromultimeric channel constructs were indistinguishable based on their sensitivity of the basal K+ current to free circulating Gβγ.

Fig. 7.

Comparative regulation of G-protein-independent current for wild-type GIRK1/GIRK2, GIRK1-GIRK2wv dimers and GIRK2wv homomeric channels by circulating intracellular levels of free Gβγ. Oocytes were incubated in glucose-containing solutions (see Materials and Methods) and injected with purified Gsα 20 min before recording, as described in Materials and Methods. Relative current amplitudes of basal- and carbachol-induced currents were under conditions of low intracellular-free Gβγ and compared to currents recorded under control conditions. Mean peak current was determined at −150 mV in high K+ solutions for six to eight oocytes pooled from two batches for each of the experimental conditions as indicated.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that GIRK1 is capable of forming heteromultimeric channels with GIRK2wv in monomer coexpression studies as well as in linked concatemers. The presence of GIRK1 in a tetrameric GIRK1/GIRK2wv channel rescued the wild-type GIRK1/GIRK2 heteromultimeric phenotype, restoring K+ selectivity and G-protein-dependent current activation. Furthermore, the position of two GIRK2wvsubunits within linked concatemers appears to determine current selectivity and G-protein dependence. GIRK2 and GIRK3 formed functional heteromultimeric channels with GIRK2wv; however, the heteromultimeric complexes retained GIRK2wv homomultimeric channel properties.

Our studies differ from those of Slesinger et al. (1996), who reported that expression of monomeric GIRK1 and GIRK2wv gave rise to a significant decrease in the amplitude of the agonist-independent basal Na+ as well as K+ currents over that observed for oocytes expressing GIRK2wv alone. In their studies, a GIRK2wv construct was used in which the first nine amino acids were deleted. The truncation of the first nine amino acids in GIRK2wv may have reduced the mutant subunit affinity for heteromultimer formation, thereby, giving rise to the difference in current expression between the two studies. In addition, our studies, unlike those of Slesinger et al. (1996), included antisense against the endogenous GIRK5. The presence of GIRK5 in their studies may have also contributed to heteromultimer formation with GIRK2wv,thereby competing with GIRK1 as a companion subunit.

In our studies, GIRK1, GIRK2, and GIRK3 failed to form functional homomeric channels when expressed either as monomers (Fig. 1) or dimers (data not shown). The apparent discrepancy between our data and the data reported in previous investigations in which expression of homomultimeric GIRK1 and GIRK2 was obtained may be caused by significant amounts of coassembly with the endogenousXenopus GIRK5 (Kofuji et al., 1995, 1996; Slesinger et al., 1996) or coexpression with Gβγ,which has been reported to increase current levels 16-fold above activation through the m2 receptor alone (Velimirovic et al., 1996). The small but detectable (280 ± 30 nA) carbachol-sensitive current that we observed for GIRK2 coexpressed with GIRK5 antisense may represent GIRK2 homomultimeric current in our experiments.

GIRK1 appears to be necessary but not sufficient for channel formation. The other interacting subunits, GIRK2, GIRK3, and GIRK4, appear to lend subtle differences in conductance or open state probability to the functional channel depending on number or position within the heterotetrameric complex. Data in support of this hypothesis come from studies of GIRK1 and GIRK4 in which current expressed from linked concatemers was maximized when channels were comprised of alternating subunits within the tetramers (Silverman et al., 1996b; Tucker et al., 1996; Corey et al., 1998). The positional studies of GIRK1 and GIRK4 in linked concatemers (Silverman et al., 1996b; Tucker et al., 1996; Corey et al., 1998) suggested that the position of multiple subunits of GIRK2wv within a heterotetramer might play a similar role in the determination of channel selectivity and G-protein dependence.

Unlike GIRK1, GIRK3 does not enhance either GIRK2 or GIRK2wvcurrent expression. In addition, GIRK3 does not seem to form functional heterotetramers with GIRK5 (Table 1). Therefore, GIRK3 seems to form heterotetramers exclusively with GIRK1.

Positional effects of GIRK2wv on channel selectivity and G-protein dependence within a tetramer

Expression of the GIRK1 and GIRK2wv tetrameric constructs yielded currents with biophysical signatures dependent on the position of the mutant subunits in the tetramer. The 1-wv-1-wv tetramer currents were G-protein-dependent and K+-selective. On the other hand, 1–1-wv-wv tetramer currents were associated with a high basal Na+ current and only a modest G-protein-dependent current in high K+ solutions (Fig. 5A,B).

The most parsimonious explanation for the current data obtained from the tetrameric constructs relies on the assumption that when subunit DNA is fixed in a concatameric array, subunit proteins will align in the same manner in the membrane. Although highly likely, one could imagine an alternative scenario, whereby, the concatenated 1–1-wv-wv sequence of cDNAs could give rise to subunits that arrange 1-wv-1-wv with the long cytoplasmic segments connecting C to N termini twisted and interwoven. The abnormal arrangement of the C- and N-termini could provide an alternate explanation for the aberrant channel behavior observed with the 1–1-wv-wv construct.

Tetramers containing at least two nonweaver subunits restore K+ selectivity and G-protein sensitivity

Previous coexpression studies of GIRK1 and GIRK2wvmonomers in oocytes have yielded conflicting results that could possibly be accounted for, in part, by subtle experimental differences in relative subunit concentrations. Kofuji et al. (1996) found that oocyte coexpression of GIRK1 with GIRK2wv gave rise to currents that were similar in selectivity and G-protein sensitivity to GIRK2wv homomultimeric currents. In other studies, coexpression of GIRK2wv with GIRK1 at a ratio of coinjected cRNA of 1:1 led to a reduction in both basal- and carbachol-induced currents, compared to oocytes expressing GIRK1 + GIRK2 (Slesinger et al., 1996). In contrast, our coexpression studies of GIRK2wvwith GIRK1 at 1:1 ratio of injected cRNA gave rise to basal- and carbachol-induced K+ currents with negligible Na+ permeability (Fig.3C), and expression of GIRK1-GIRK2wv dimer showed current selectivity and G-protein dependence similar to expression of the GIRK1-GIRK2 dimer and the coexpression of monomers (Fig.4C).

Correlation between cell survival and GIRK1 expression in theweaver mouse brain

It is our hypothesis that susceptibility to cell death among populations of neurons in the weaver mouse may result from differential isoform expression and, therefore, the availability of GIRK subunits to form functional channels. In that the homomultimeric GIRK2wv channel is the most pathological, our hypothesis would predict that cell death would be highest in those neurons that demonstrate the highest levels of GIRK2 expression. Substantia nigra (SN) is the primary target for cellular degeneration in theweaver mouse (Table 2), in which GIRK2 protein expression is highest and in which there is a considerable reduction in both GIRK2-positive cells as well as cell number with increasing age (Liao et al., 1996). Within the SN, the strongest GIRK2 expression was seen in the pars compacta, the region most vulnerable to cell death. The more laterally placed neurons in SN pars lateralis, which do not stain for GIRK2 protein expression, are for the most part spared in weaver homozygotes (Graybiel et al., 1990; Liao et al., 1996; Roffler-Tarlov et al., 1996; Wei et al., 1997; Schein et al., 1998). Thus, in the SN there is a direct correlation between the magnitude of GIRK2 expression and cell death.

Table 2.

Anatomical correlation between GIRK subunit expression and cell survival in the weavermouse

| Region | Age | GIRK1 protein | GIRK2 protein | Cell fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory bulb | P7 | +a | +a,c | Survival |

| Adult | +b | +a,c | Survival | |

| Cerebral cortex | Adult | +++a | +++a | Survival |

| Caudate putamen | P7 | −b | Survival | |

| Adult | +a | −a | Survival | |

| Hippocampus | Adult | ++a | ++a | Survival |

| Thalamus | +++a | −a | Survival | |

| Midbrain | ||||

| Ventral tegmental area | P7 | −a,b,c | −c | Survival |

| Adult lateral | −a,b,c | +a,c | Death | |

| Adult medial | −a,b,c | −c | Survival | |

| Substantia nigra | P7 | −a,b,c | +++a,c | Survival |

| pars compacta | Adult | −a,b,c | +++a,c | Death |

| pars reticulata | Adult | −a,b,c | +++a,c | Death |

| pars lateralis | Adult | −a,b,c | −c | Survival |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| External germinal layer | P7 | +++b | +++c | Death |

| Adult | +++a,b | +++a,b,c | Death | |

| Purkinje cells | P7 midline | −a,b | ++b | Death |

| Adult midline | −a,b | +++a,b,c | Death | |

| Purkinje cells | P7 lateral | −c | −c | Survival |

| Adult lateral | −a,b | −a,b,c | Survival | |

| Internal granular layer | Adult | ++b | ++b,c | Death |

| Deep cerebellar nuclei | Adult | +++a,c | +++a,c | Death |

Staining intensities: +++, strong; ++, moderate; +, light; −, little to no background levels.

The early cytoarchitectural studies of the weaver mouse cerebellum conducted by Herrup and Trenkner (1987) revealed an apparent gradient in cell death with the selective loss of granule cells only in the medial cerebellum with a substantial number surviving in the lateral cerebellar cortex. Patterns of protein expression for the mutant GIRK2 protein in the weaver mouse have since provided an explanation for their initial observations. Schein et al. (1998)observed that Purkinje cells of the lateral cerebellum expressed little GIRK2 and were also spared. However, there was selective loss of Purkinje cells in the midline, which correlated with enhanced an expression of GIRK2. Corroborating studies carried out by Schlesinger et al. (1996) on the highly vulnerable, developing weavermouse cerebellar Purkinje cells also demonstrated expression of GIRK2 but not GIRK1.

The loss of granule cells in the external germinal layer, the internal granular layer, and the deep cerebellar nuclei of the cerebellum in theweaver mouse that express both GIRK1 and GIRK2 would, at first examination, appear to be an exception to our hypothesis, i.e., that elevated levels of GIRK1/GIRK2wv expression might spare neurons through the formation of functional heteromultimeric channels. The apparent inconsistency could be accounted for on a number of levels. The weaver mutation could quantitatively exert variable toxicity in different neuronal populations depending on relative levels of protein expression with respect to wild-type isoforms e.g., GIRK1 (Liao et al., 1996; Roffler-Tarlov et al., 1996;Wei et al., 1997; Schein et al., 1998). The mutant toxicity could also be a function of the splice variant of GIRK2 which is expressed within a given region. To date, five splice variants of GIRK2 have been reported: GIRK2–1, GIRK2A (A1 and A2), GIRK2B, and GIRK2C (Isomoto et al., 1996; Wei et al., 1998). Wei et al (1998) detected strong expression of GIRK2B and GIRK2C in the cerebellum and suggested that their respective proteins may play prominent roles in the mutation-induced pathology of the weaver mice. Isomoto et al. (1996) demonstrated that GIRK2B forms functional homomultimers. By analogy, GIRK2C may also form a functional channel. Based on their observations, we speculate that the weaver mutant forms of GIRK2B and 2C strongly expressed in the cerebellar granule cells may have a higher affinity for the formation of homomultimeric mutant channels than heterooligomers with GIRK1, thereby giving rise to enhanced cell death.

In summary, our study addresses the issue of stoichiometric and functional relationships between GIRK channel subunits. Our results constitute strong evidence that GIRK1 forms heteromultimeric channels with GIRK2wv, restoring G-protein sensitivity and K+ selectivity and thereby suppressing the lethal weaver phenotype. Thus, different susceptibilities to cell death among different populations of neurons may result from differences in ratio of expression of GIRK subunit isoforms among the different neuronal populations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 GM36823 and RO1 GM 54266. We thank Drs. Aaron P. Fox, Henry A. Lester, Anke Di, and Dorothy A. Hanck for many helpful discussions as well as Clark Lin and Boris Krupa for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Deborah J. Nelson, The University of Chicago, Department of Neurobiology, Pharmacology, and Physiology, 947 East 58th Street, MC 0926, Chicago, IL 60637.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer SA, Wills KV, Triarhou LC, Verina T, Thomas JD, Ghetti B. Selective vulnerability of late-generated dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra in weaver mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9137–9140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey S, Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. Number and stoichiometry of subunits in the native atrial G-protein-gated K+ channel, IKACh. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5271–5278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dascal N. Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cell Signal. 1997;9:551–573. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dascal N, Schreibmayer W, Lim NF, Wang W, Chavkin C, DiMagno L, Labarca C, Kieffer BL, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Trollinger D, Lester HA, Davidson N. Atrial G protein-activated K+ channel: expression cloning and molecular properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10235–10239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao W-Q, Hatten ME. Neuronal differentiation rescued by implantation of weaver granule cell precursors into wild-type cerebellar cortex. Science. 1993;260:367–369. doi: 10.1126/science.8469990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldowitz D. The weaver granuloprival phenotype is due to intrinsic action of the mutant locus in granule cells: evidence from homozygous weaver chimeras. Neuron. 1989;2:1565–1575. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldowitz D, Smeyne RJ. Tune into the weaver channel. Nat Genet. 1995;11:107–109. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graybiel AM, Ohta K, Roffler-Tarlov S. Patterns of cell and fiber vulnerability in the mesostriatal system of the mutant mouse weaver. I. Gradients and compartments. J Neurosci. 1990;10:720–733. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00720.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatten ME, Liem RKH, Mason CA. Defects in specific associations between astroglia and neurons occur in microcultures of weaver mouse cerebellar cells. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1163–1172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-04-01163.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedin KE, Lim NF, Clapham DE. Cloning of a Xenopus laevis inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunit that permits GIRK1 expression of IKACh currents in oocytes. Neuron. 1996;16:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrup K, Trenkner E. Regional differences in cytoarchitecture of the weaver cerebellum suggest a new model for weaver gene action. Neuroscience. 1987;23:871–885. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess EJ. Identification of the weaver mouse mutation: the end of the beginning. Neuron. 1996;16:1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isomoto S, Kondo C, Takkahashi N, Matsumoto S, Yamada M, Takumi T, Horio Y, Kurachi Y. A novel ubiquitously distributed isoform of GIRK2 (GIRK2B) enhances GIRK1 expression of the G-protein-gated K+ current in Xenopus oocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:286–291. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jan LY, Jan YN. Cloned potassium channels from eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997a;20:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan LY, Jan YN. Voltage-gated and inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J Physiol (Lond) 1997b;505:267–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.267bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kofuji P, Davidson N, Lester HA. Evidence that neuronal G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels are activated by Gβγ subunits and function as heteromultimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6542–6546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kofuji P, Hofer M, Millen KJ, Millonig JH, Davidson N, Lester HA, Hatten ME. Functional analysis of the weaver mutant GIRK2 K+ channel and rescue of weaver granule cells. Neuron. 1996;16:941–952. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krapivinsky G, Gordon EA, Wickman K, Velimirovic B, Krapivinsky L, Clapman DE. The G-protein-gated atrial K+ channel IKACh is a heteromultimer of two inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins. Nature. 1995;374:135–141. doi: 10.1038/374135a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo Y, Baldwin TJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 1993a;362:127–133. doi: 10.1038/362127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo Y, Reuveny E, Slesinger PA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a rat G-protein-coupled muscarinic potassium channel. Nature. 1993b;364:802–806. doi: 10.1038/364802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E, Linder ME, Gilman AG. Expression of G-protein alpha subunits in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1994;237:146–164. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)37059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lesage F, Duprat F, Fink M, Guillemare E, Coppola T, Lazdunski M, Hugnot J-P. Cloning provides evidence for a family of inward rectifier and G-protein coupled K+ channels in the brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Fosset M, Romey G, Barhanin J, Lazdunski M. Molecular properties of neuronal G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28660–28667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Heteromultimerization of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins GIRK1 and GIRK2 and their altered expression in weaver brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7137–7150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07137.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Migheli A, Piva R, Wei J, Attanasio A, Casolino S, Hodes ME, Dlouhy SR, Bayer SA, Ghetti B. Diverse cell death pathways result from a single missense mutation in weaver mouse. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1629–1638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarro B, Kennedy ME, Velimirovic B, Bhat D, Peterson AS, Clapham DE. Nonselective and Gβγ -insensitive weaver K+ channels. Science. 1996;272:1950–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patil N, Cox DR, Bhat D, Faham M, Myers RM, Peterson AS. A potassium channel mutation in weaver mice implicates membrane excitability in granule cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 1995;11:126–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakic P, Sidman RL. Sequence of developmental abnormalities leading to granule cell deficit in cerebellar cortex of weaver mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 1973;152:103–132. doi: 10.1002/cne.901520202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roffler-Tarlov S, Martin B, Graybiel AM, Kauer JS. Cell death in the midbrain of the murine mutation weaver. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1819–1826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01819.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi P, De Filippi G, Armano S, Taglietti V, D’Angelo E. The weaver mutation causes a loss of inward rectifier current regulation in premigratory granule cells of the mouse cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3537–3547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03537.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schein JC, Hunter DD, Roffler-Tarlov S. GIRK2 expression in the ventral midbrain, cerebellum, and olfactory bulb and its relationship to the murine mutation weaver. Dev Biol. 1998;204:432–450. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt MJ, Sawyer BD, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Foreman MM, Ghetti B. Dopamine deficiency in the weaver mutant mouse. J Neurosci. 1982;2:376–380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00376.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman SK, Kofuji P, Dougherty DA, Davidson N, Lester HA. A regenerative link in the ionic fluxes through the weaver potassium channel underlies the pathophysiology of the mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996a;93:15429–15434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverman SK, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Subunit stoichiometry of a heteromultimeric G protein-coupled inward-rectifier K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 1996b;271:30524–30528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slesinger PA, Patil N, Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY, Cox DR. Functional effects of the mouse weaver mutation on g protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:321–331. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slesinger PA, Stoffel M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Defective γ-aminobutyric acid type B receptor-activated inwardly rectifying K+ currents in cerebellar granule cells isolated from weaver and Girk2 null mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12210–12217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smeyne RJ, Goldowitz D. Development and death of external granular layer cells in the weaver mouse cerebellum: a quantitative study. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1608–1620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surmeier DJ, Mermelstein PG, Goldowitz D. The weaver mutation of GIRK2 results in a loss of inwardly rectifying K+ current in cerebellar granule cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tucker SJ, Pessia M, Adelman JP. Muscarine-gated K+ channel: subunit stiochiometry and structural domains essential for G protein stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H379–H385. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.1.H379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velimirovic BM, Gordon EA, Lim NF, Navarro B, Clapham DE. The K+ channel inward rectifier subunits form a channel similar to neuronal G protein-gated K+ channel. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01465-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vivaudou M, Chan KW, Sui J-L, Jan LY, Reuveny E, Logothetis DE. Probing the G-protein regulation of GIRK1 and GIRK4, the two subunits of the KACh channel, using functional homomeric mutants. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31553–31560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei J, Dlouhy SR, Bayer S, Piva R, Verina T, Wang Y, Feng Y, Dupree B, Hodes ME, Ghetti B. In situ hybridization analysis of GIRK2 expression in the developing central nervous system in normal and weaver mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:762–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei J, Hodes ME, Piva R, Feng Y, Wang Y, Ghetti B, Dlouhy SR. Characterization of murine GIRK2 transcript isoforms: Structure and differential expression. Genomics. 1998;51:379–390. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J, Jan YN, Jan LY. Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Neuron. 1995;15:1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshii K, Kurihara K. Inward rectifier produced by Xenopus oocytes injected with mRNA extracted from carp olfactory epithelium. Synapse. 1989;3:234–238. doi: 10.1002/syn.890030309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]