Abstract

Repetitive activation of corticostriatal fibers produces long-term depression (LTD) of excitatory synaptic potentials recorded from striatal spiny neurons. This form of synaptic plasticity might be considered the possible neural basis of some forms of motor learning and memory. In the present study, intracellular recordings were performed from rat corticostriatal slice preparations to study the role of glutamate and other critical factors underlying striatal LTD. In current-clamp, but not in voltage-clamp experiments, brief focal applications of glutamate, as well as high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of corticostriatal fibers, induced LTD. This pharmacological LTD and the HFS-induced LTD were mutually occlusive, suggesting that both forms of synaptic plasticity share common induction mechanisms. Isolated activation of either non-NMDA-ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), respectively by AMPA and t-ACPD failed to produce significant long-term changes of corticostriatal synaptic transmission. Conversely, LTD was obtained after the simultaneous application of AMPA plust-ACPD. Moreover, also quisqualate, a compound that activates both iGluRs and group I mGluRs, was able to induce this form of pharmacological LTD. Electrical depolarization of the recorded neurons either alone or in the presence of t-ACPD and dopamine (DA) failed to mimic the effects of the activation of glutamate receptors in inducing LTD. However, electrical depolarization was able to induce LTD when preceded by coadministration oft-ACPD, DA, and a low dose of hydroxylamine, a compound generating nitric oxide (NO) in the tissue. None of these compounds alone produced LTD. Glutamate-induced LTD, as well as the HFS-induced LTD, was blocked by l-sulpiride, a D2 DA receptor antagonist, and by 7-nitroindazole monosodium salt, a NO synthase inhibitor. The present study indicates that four main factors are required to induce corticostriatal LTD: (1) membrane depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron; (2) activation of mGluRs; (3) activation of DA receptors; and (4) release of NO from striatal interneurons.

Keywords: dopamine, excitatory amino acids, nitric oxide, metabotropic glutamate receptors, motor learning, striatum

Long-term changes in the efficacy of excitatory synaptic transmission have been proposed as possible cellular substrates underlying learning and memory (Teyler and Discenna, 1984; Ito, 1989). Two different forms of synaptic plasticity have been described at corticostriatal glutamatergic synapses: long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP) (Calabresi et al., 1992a,b, 1994, 1996, 1998; Lovinger et al., 1993; Walsh, 1993;Choi and Lovinger, 1997). These events might represent a possible cellular mechanism for the storage of motor skills (Calabresi et al., 1992a,b, 1996, 1998). High-frequency stimulation (HFS) of corticostriatal fibers is the common experimental protocol used to induce corticostriatal LTD. Moreover, we have recently reported that this form of synaptic plasticity can be obtained after pharmacological stimulation of the nitric oxide (NO)/cGMP pathway (Calabresi et al., 1999). Several physiological and biochemical events are supposed to be crucial for the induction of LTD at corticostriatal glutamatergic synapses: depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron, activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), activation of dopamine (DA) receptors, and release of NO from striatal interneurons (Calabresi et al., 1999). However, how these various factors interact to generate and maintain striatal LTD has not been clarified yet. Various experimental approaches have been used to study the contribution of the different neurotransmitter receptors and postreceptor mechanisms in this form of synaptic plasticity: application of pharmacological antagonists, anatomical lesions of specific neuronal pathways, and genetic disruptions. Accordingly, the role of endogenous DA in striatal LTD has been supported by the use of pharmacological antagonists (acting on D1-like and D2-like DA receptors), unilateral nigral lesions, and genetic disruption of D2 receptors (Calabresi et al., 1992a, 1997; Choi and Lovinger, 1997). Moreover, striatal LTD is blocked by antagonists acting at mGluRs but not by NMDA receptor antagonists (Calabresi et al., 1992a; Lovinger et al., 1993). Finally, the evidence that blockers of L-type high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels abolish striatal LTD supports the idea that postsynaptic membrane depolarization is critical because of the subsequent elevation of intracellular Ca2+ (Calabresi et al., 1994).

In the present study we have tried to dissect the role of each single factor involved in the generation of striatal LTD. As an alternative approach to the HFS of glutamatergic corticostriatal fibers, we have focally applied exogenous glutamate agonists acting on iGluRs, mGluRs, or both. These agonists have been applied either alone or in combination with DA and a NO-generating drug (hydroxylamine). In some experiments, we have replaced the postsynaptic membrane depolarization induced by either HFS or glutamate with positive current injections into the postsynaptic neuron.

It is generally assumed that HFS of corticostriatal terminals solely results in a massive and transient release of glutamate from these fibers. However, other additional and glutamate-independent events might occur during this stimulation and cooperate in inducing LTD. For example, the massive release of DA observed after HFS, considered as a result of the activation of glutamate receptors located on DAergic presynaptic terminals (Calabresi et al., 1995a), may conversely depend on the spread of electrical stimulation in the slice. Thus, the focal application of glutamate and glutamatergic agonists provides conclusive evidence concerning the postulated primary role of glutamate in triggering the ligand- and voltage-dependent events required in the induction of corticostriatal LTD. In the present study, we demonstrate that glutamate triggers a complex interplay between membrane depolarization, activation of both DA and mGlu receptors, and NO production to generate LTD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and maintenance of the slices. Adult male Wistar rats (150–250 gm) were used for all the experiments. The preparation and maintenance of coronal slices have been described previously (Calabresi et al., 1990a,b, 1995b). Briefly, corticostriatal coronal slices (200–300 μm) were prepared from tissue blocks of the brain with the use of a vibratome. A single slice was transferred to a recording chamber and submerged in a continuously flowing Krebs’ solution (35°C, 2–3 ml/min) gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The composition of the control solution was (in mm): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 11 glucose, and 25 NaHCO3.

Recording technique. In all the experiments, the intracellular recording electrodes were filled with 2 m KCl (30–60 MΩ). An Axoclamp 2B amplifier was used for recordings either in current-clamp or in voltage-clamp mode. In single-electrode voltage-clamp mode, the switching frequency was 3 kHz. The headstage signal was continuously monitored on a separate oscilloscope. Traces were displayed on an oscilloscope and stored in a digital system. For synaptic stimulation, bipolar electrodes were used. These stimulating electrodes were located either in the cortical areas close to the recording electrode or in the white matter between the cortex and the striatum to activate corticostriatal fibers. As conditioning tetanus (HFS), we used three trains (3 sec duration, 100 Hz frequency, at 20 sec intervals). During tetanic stimulation, the intensity was increased to suprathreshold levels. Quantitative data on EPSP modifications induced by tetanic stimulation are expressed as a percentage of the controls, the latter representing the mean of responses recorded during a stable period (15–20 min) before the tetanus. In some experiments the induction of LTD was obtained by three intracellular injections of depolarizing current (1–1.5 nA for 3 sec, at 20 sec interval). During the depolarization the cells fired action potentials, at least in the early phase of the depolarization (250–500 msec). After 3 sec of current injection, the amount of the depolarizing current was progressively (within 5–10 sec) reduced to mimic the time course of the HFS-induced depolarization.

Morphological identification of the recorded cells. In some experiments biocytin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used in the intracellular electrode to stain the neurons. In these cases, biocytin at concentration of 2–4% was added to a 0.5 m KCl pipette solution. Slices containing neurons stained with biocytin were fixed in paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 m phosphate buffer at pH 7.4) overnight and processed according to published protocols (Horikawa and Armstrong, 1988). In several cases, sections were further processed to make permanent staining of biocytin-loaded cells.

Data analysis and drug applications. Values given in the text and in the figures are mean ± SEM of changes in the respective cell populations. Student’s t test (for paired and unpaired observations) was used to compare the means. Drugs were applied by dissolving them to the desired final concentration and by ejecting (pressure ejection; Picospritzer; General Valve, Fairfield, NJ) a few nanoliters from the tip of a blunt pipette beneath the surface of the superfusing solution and just above the tissue slice. In some experiments, l-sulpiride was bath-applied by switching the perfusion from control saline to drug-containing saline. Drug solutions entered the recording chamber within 40 sec after a three ways tap had been turned on. AMPA, glutamate, quisqualate, 7-nitroindazole monosodium salt (7-NINA), 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ),t-ACPD, andS-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine were from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). DA and l-sulpiride were from Sigma-RBI (Milano, Italy). Hydroxylamine was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

RESULTS

Properties of the recorded neurons

Conventional sharp microelectrode intracellular recordings were obtained from 150 electrophysiologically identified “principal” spiny cells. The main characteristics of these cells have been described in detail previously both in vivo (Wilson and Groves, 1980; Calabresi et al., 1990c) and in vitro (Kita et al., 1984; Calabresi et al., 1990a,b, 1996; Cepeda et al., 1994). These cells had high resting membrane potential (−84 ± 5 mV), relatively low apparent input resistance (38 ± 8 MΩ) when measured at the resting potentials from the amplitude of small (<10 mV) hyperpolarizing electrotonic potentials, action potentials of short duration (1.1 ± 0.3 msec), and high amplitude (102 ± 4 mV). They were silent at rest and showed membrane rectification and tonic firing activity during depolarizing current pulses. In 20 of the 120 recorded spiny neurons, the electrophysiological identification was confirmed by a morphological analysis obtained by using biocytin staining (data not shown).

Effects of focal application of glutamate on corticostriatal transmission

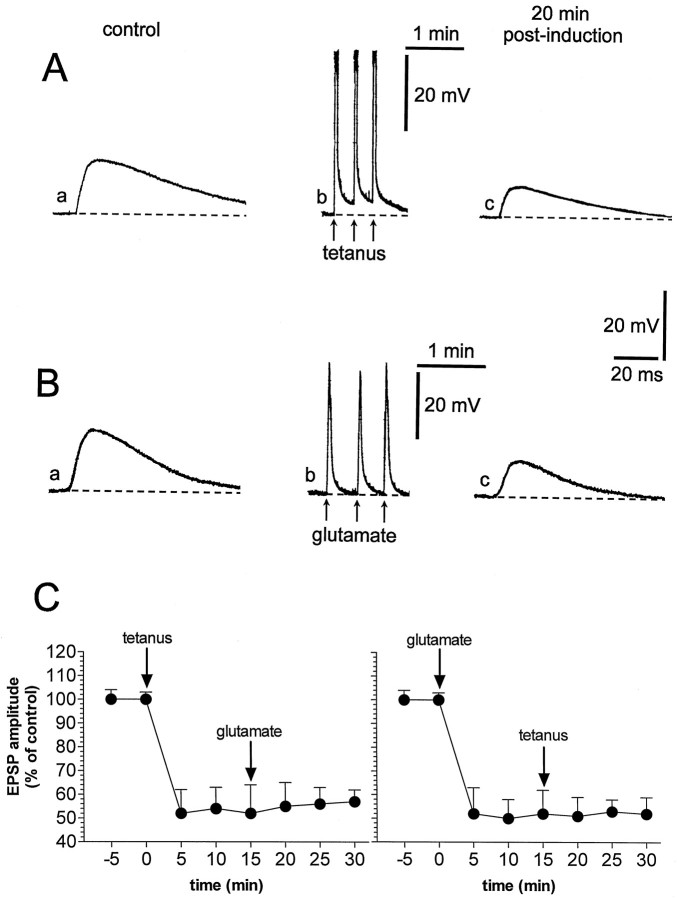

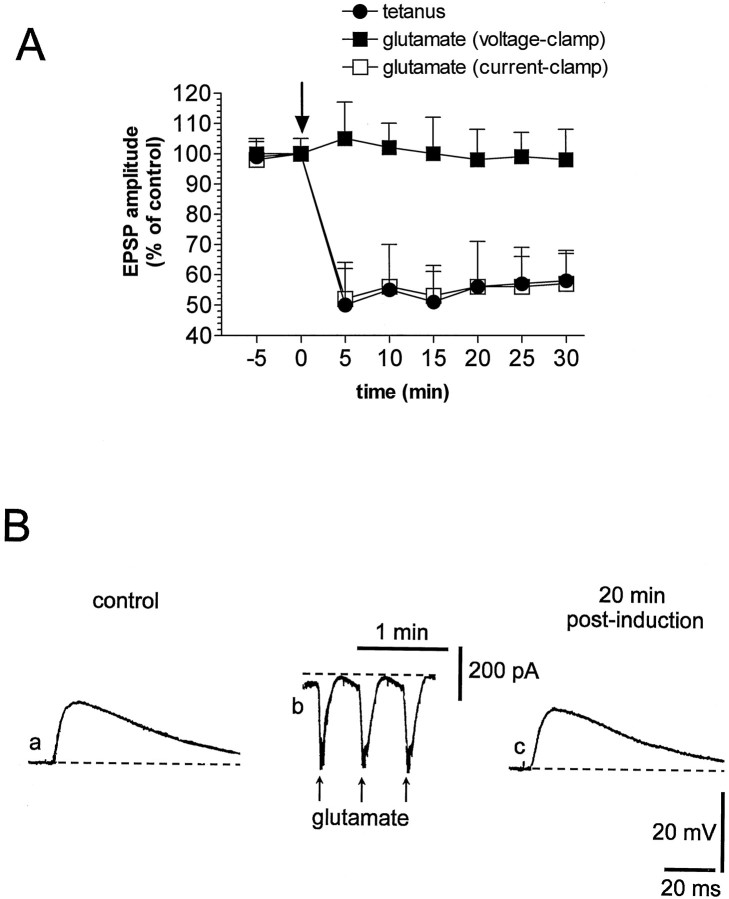

In current-clamp experiments, three brief applications (0.5 sec) of glutamate (0.3–1 mm), obtained by pressure injection of this agonist near the recording electrode (30–300 μm), produced fast and reversible membrane depolarizations and caused a long-lasting depression of corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission (n = 23; p < 0.01). The amplitude and the duration of the membrane depolarizations induced by the applications of glutamate (35 ± 7 mV amplitude, 9.6 ± 3 sec duration) mimicked in magnitude and duration the membrane depolarizations obtained by the three tetanic stimulations of corticostriatal fibers (40 ± 6 mV amplitude, 8 ± 1.8 sec duration) that were required to induce LTD (Calabresi et al., 1992a,1994, 1997) (Fig.1A,B). Furthermore, the depression of synaptic transmission induced by exogenous glutamate was similar to the depression induced by HFS and lasted >1 hr. This pharmacological LTD, as well as the HFS-induced LTD, was not coupled with changes of intrinsic membrane properties (membrane potential, input resistance, and current-induced firing discharge) of the recorded neurons (data not shown). In eight of eight experiments, the LTD induced by brief applications of glutamate occluded the LTD caused by HFS and vice versa (n = 7), suggesting that these forms of synaptic plasticity share common induction mechanisms (Fig. 1C). We also studied the effects of pressure application of glutamate on corticostriatal synaptic transmission in voltage-clamp experiments. In these experiments (n = 9), during the applications of exogenous glutamate, the membrane potential of the recorded cells was clamped close to the resting potential (−83 ± 4 mV); thus, under this experimental condition, the focal administrations of this agonist produced inward currents in the recorded striatal neurons. Corticostriatal EPSPs, measured before and after the applications of glutamate, were recorded in current-clamp mode. In this set of experiments glutamate failed to produce stable changes of the amplitude of recorded EPSPs, confirming the major role of the membrane depolarization of striatal neurons in the glutamate-induced LTD (p > 0.05) (Fig.2).

Fig. 1.

Brief glutamate applications mimic HFS-induced LTD. A, A corticostriatal EPSP evoked in control condition from a striatal spiny neuron (a) is reduced 20 min after (c) three tetanic stimulations (b). B, In a different cell, the EPSP observed under control condition (a) is reduced 20 min after (c) three brief focal applications of glutamate (b). In both experiments, the dotted line represents the resting membrane potential (RMP = −85 mV in A and −86 mV in B). Ina and c, averages of four single sweeps are shown; calibration in c applies also toa. The traces shown in b represent slower membrane potential changes during the induction phase of LTD (note the difference in the time scale). C, Left, Plot of the data obtained from several experiments showing that the induction of LTD by the tetanic stimulation occludes further depression by the glutamate application. Right, Plot of the data showing that the induction of LTD by glutamate occludes further depression by tetanic stimulation. In Ab andBb the action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

Fig. 2.

Glutamate-induced LTD is blocked by voltage clamp of the membrane during the induction phase. A, The plot shows data obtained from several experiments in which corticostriatal LTD was induced either by the tetanic stimulation (filled circles) or by glutamate applications under the current-clamp condition (open squares). The plot also shows that the voltage clamp of the membrane during glutamate applications prevents the induction of LTD (filled squares). Thearrow represents the two induction stimuli (HFS or focal glutamate application). B, Traces represent a single experiment in which the EPSP amplitude measured under control condition (a) was not affected 20 min after (c) the focal application of glutamate in the voltage-clamp mode (b). Note thatb shows inward current measured at the holding potential (dotted line = −84 mV). The dotted line in a and c represents the RMP (−84 mV). Calibration in c applies also toa.

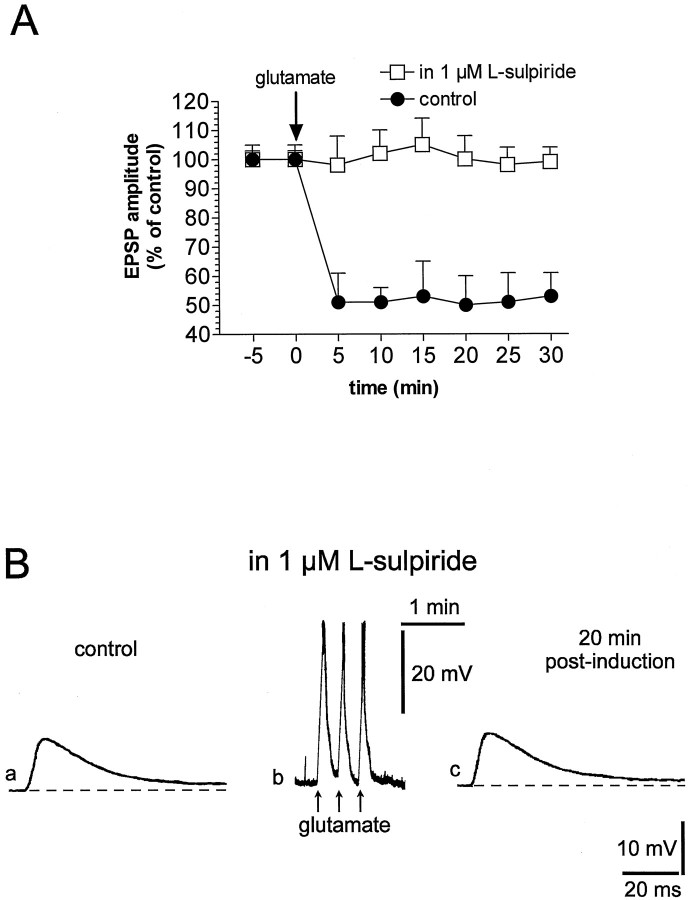

Effects of isolated and simultaneous iGluR and mGluR activation on corticostriatal transmission

We also studied the effects of isolated and simultaneous activation of iGluRs and mGluRs on corticostriatal synaptic transmission obtained by the application of three different glutamatergic agonists: AMPA, an iGluR agonist for the non-NMDA receptors, t-ACPD, a broad spectrum agonist of mGluRs, and quisqualate, a compound that activates both non-NMDA iGluRs and mGluRs of the group I (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995). Focal applications of AMPA (30 μm) by pressure injection produced reversible membrane depolarizations of striatal neurons. AMPA failed to induce significant changes of corticostriatal synaptic transmission, although this compound produced membrane depolarizations similar to those caused by HFS and exogenous glutamate (n = 7; p> 0.05) (Fig. 3A). It has already been reported that the activation of mGluRs by bath application of t-ACPD produces a reduction of the amplitude of cortically evoked EPSPs (Calabresi et al., 1993a; Pisani et al., 1997a). Pressure injection of t-ACPD (50 μm) near the recorded neurons did not cause membrane depolarizations but produced a depression of the EPSPs. This effect, however, was not long-lasting and was quickly reversible after 5–7 min wash-out (n = 5) (Fig. 3A). Conversely, long-lasting depression of corticostriatal synaptic transmission was obtained by coactivating iGluRs and mGluRs after the focal application of AMPA plust-ACPD (n = 10) (Fig. 3A) or quisqualate (n = 10) (Fig. 3B). In fact, pressure applications of both quisqualate (50 μm) and AMPA (30 μm) plus t-ACPD (50 μm) produced fast membrane depolarizations of the recorded neurons and caused a stable reduction of the amplitude of corticostriatal EPSPs, which was not associated with changes of neuronal intrinsic membrane properties. Similarly to the findings obtained for glutamate, the quisqualate- and AMPA plus t-ACPD-induced LTD were occluded by the HFS-induced LTD (n = 8) and were prevented when the applications of these agonists were performed in the voltage-clamp mode (n = 7; p > 0.05) (Fig.3B).

Fig. 3.

Activation of both iGluRs and mGluRs is required for corticostriatal LTD. A, The plot on theleft shows that neither AMPA alone (open triangles) nor t-ACPD alone (open squares) is sufficient to induce corticostriatal LTD, whereas this form of synaptic plasticity is induced by coadministration of both these drugs (filled circles). The top traces on the right show that an EPSP recorded under control condition (a) is not affected 20 min after focal application of AMPA alone (b) (dotted line indicates RMP = −85 mV). Thebottom traces on the right show that an EPSP recorded under control condition (c) is reduced 20 min after the focal application of AMPA plust-ACPD (d) (dotted line indicates RMP = −86 mV). B, The plot on the left shows that the focal application of quisqualate under the current-clamp mode induces LTD (open triangles), whereas this form of synaptic plasticity is prevented by the voltage clamp of the membrane during the application of quisqualate (filled triangles). Traces on theright show a single experiment in which the EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) is reduced 20 min after (c) the focal application of quisqualate in the current-clamp mode (b). Thedotted line represents the RMP (−85 mV). InBb the action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

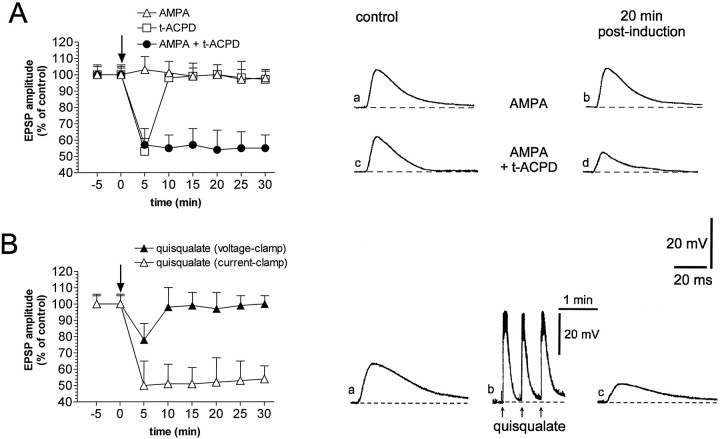

Effects of l-sulpiride on glutamate-induced LTD

Activation of DA receptors is required for the induction of LTD after HFS of corticostriatal fibers (Calabresi et al., 1992a; Choi and Lovinger, 1997a). To further investigate the role of these receptors in the long-term modulation of the efficacy of corticostriatal synaptic transmission, we tested the selective D2 DA receptor antagonistl-sulpiride on glutamate-induced LTD. In previous reports this pharmacological agent fully prevented LTD induced by HFS (Calabresi et al., 1992a). In the presence of l-sulpiride (1 μm, 7–10 min), the amplitude and the duration of the membrane depolarizations induced by the focal applications of glutamate (39 ± 4 mV amplitude, 10 ± 4 sec duration) were similar to those obtained in control solution and required for the induction of LTD. However, no significant changes in the EPSP amplitude were observed after the application of glutamate, suggesting that DA D2 receptor activation plays a major role also in this pharmacological LTD (n = 10; p > 0.05) (Fig.4).

Fig. 4.

Endogenous DA acting on D2-like DA receptors is required for the induction of glutamate-induced LTD. A, The plot shows that glutamate-induced LTD recorded under control condition (filled circles) is prevented by the incubation of the slice (10 min before the induction) in 1 μml-sulpiride (open squares).B, Traces represent a single experiment in which the EPSP amplitude measured in 1 μml-sulpiride (a) was not affected 20 min after (c) the focal application of glutamate (b). The dotted line ina and c represents the RMP (−84 mV). Calibration in c applies also to a. InBb the action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

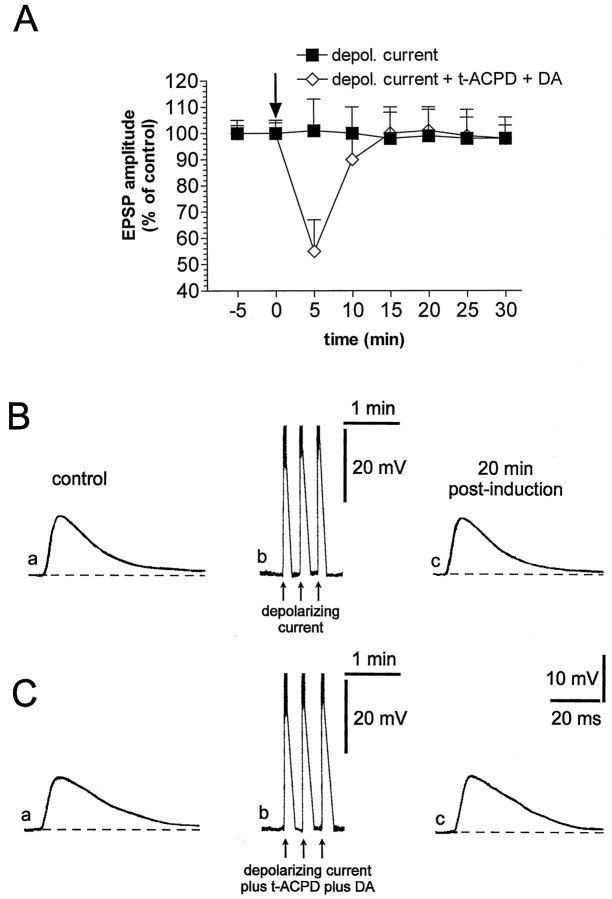

Effects of membrane depolarization on the induction of corticostriatal LTD

We also studied the effects of electrical depolarization on corticostriatal synaptic transmission. In control solution, the injection of three pulses of positive current (1–1.5 nA; 3 sec duration; 42 ± 6 mV amplitude) through the recording electrode mimicked the large and transient depolarization produced by both HFS and focal application of glutamate but failed to induce short- or long-term changes in the amplitude of cortically evoked EPSPs (n = 5) (Fig.5A,B). Because the membrane depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron alone was not sufficient to induce LTD, we also studied the effects of the simultaneous electrical depolarization and the focal application oft-ACPD (50 μm) plus DA (200 μm) on corticostriatal synaptic transmission. As shown in Figure 5,A and C, in these sets of experiments only a short-term depression of the amplitude of the EPSPs was observed (n = 11; p > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Depolarizing current injections alone or in combination with t-ACPD plus DA are not sufficient to induce corticostriatal LTD. A, The plot shows that the depolarizing current alone (filled squares) did not induce LTD. This experimental protocol in association with the focal application of t-ACPD plus DA only induced a short-term depression of corticostriatal EPSPs (open diamonds). B, Traces represent a single experiment showing that EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) was not altered 20 min after (c) the depolarization of the neuron by positive current injection (b). The dotted line indicates the RMP (−85 mV). C, Traces represent a single experiment showing that EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) was not altered 20 min after (c) the depolarization of the neuron by positive current injection in association with focal application oft-ACPD plus DA (b). Thedotted line indicates the RMP (−86 mV). Calibrations inc apply also to a. In Bband Cb the action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

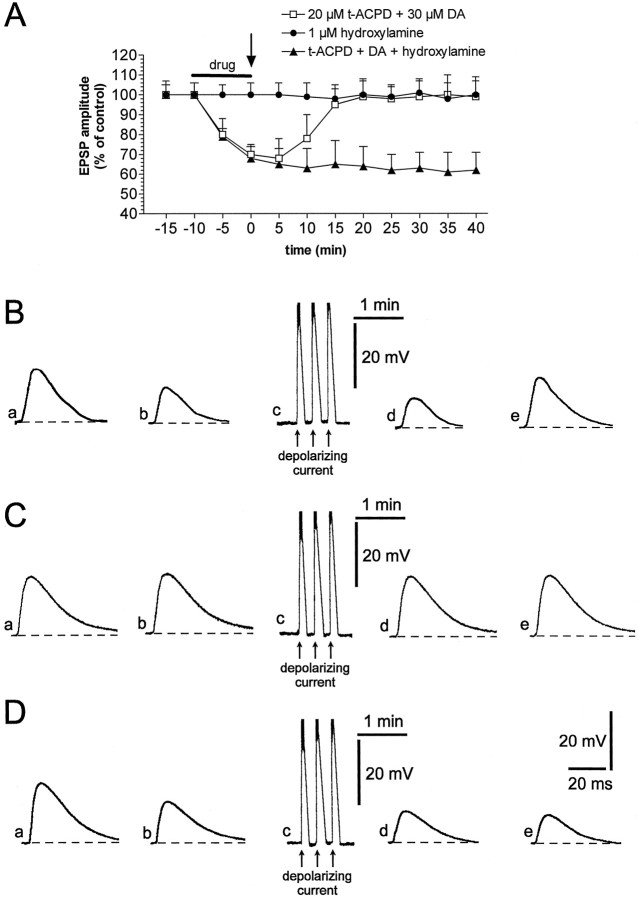

Effects of membrane depolarization combined with t-ACPD, DA, and hydroxylamine

It has been shown that focal application of high doses of DA might induce LTP instead of LTD (Wickens et al., 1996). Thus, it is possible that the high concentration of focally applied DA (200 μm) masks the expression of LTD. For this reason, we tested the possibility that lower concentrations of bath-applied DA (30 μm) and t-ACPD (20 μm) in conjunction with membrane depolarization could cause LTD. However, as shown in Figure 6, A andB, also preincubation of the slice with 20 μmt-ACPD plus 30 μm DA failed to induce LTD, but only produced a reversible depression of the EPSPs (n = 5). At this point, we considered the possibility that the induction of this “chemical” LTD, as well as the generation of HFS-induced LTD, also requires NO release from striatal interneurons, in addition to mGluR and DA receptor activation. To test this hypothesis, we applied a low dose (1 μm) of hydroxylamine, a compound that generates NO in the tissue by the action of catalase and other metalloproteins (Southam and Garthwaite, 1991). Hydroxylamine, differently than other NO donors that spontaneously generate NO by hydrolysis (Southam and Garthwaite, 1991), allowed us to achieve dose-related effects. In fact, whereas a high dose of hydroxylamine (100 μm) generates per se LTD at corticostriatal synapses (Calabresi et al., 1999), a low dose of this compound (1 μm; n = 5) did not affect EPSP amplitude. This low concentration of hydroxylamine was unable to produce LTD even when it was coupled with postsynaptic depolarizing current injections (Fig. 6A,C). However, when this low dose was administered in combination with 30 μmDA and 20 μmt-ACPD and followed by current-induced membrane depolarizations, a robust LTD was observed (Fig. 6A,D; n = 9). It is interesting to note, however, that coadministration of 30 μm DA, plus 20 μmt-ACPD and 1 μm hydroxylamine in the absence of current-induced membrane depolarizations produced only a transient reduction of the EPSP amplitude (−31% ± 5; n = 6). This reduction, in fact, was fully reversed after 10 min of the washout of the drugs (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Depolarizing current injections in combination with t-ACPD, DA, and hydroxylamine induce corticostriatal LTD. A, The plot shows that depolarizing current, neither in association with t-ACPD and DA (open squares) nor with hydroxylamine (filled circles) is able to induce LTD. Conversely, when depolarizing pulses were administered in association with t-ACPD, DA, and hydroxylamine (filled triangles), they were able to induce LTD. B, Traces represent a single experiment showing that EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) was depressed 10 min after (b) the application oft-ACPD plus DA; EPSP was not significantly depressed 5 min (d) after depolarizing current (c), and recovered to control level 20 min after the washout of the drugs (e). The dotted line indicates the RMP (−83 mV). C, Traces represent a single experiment, showing that EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) was not affected 10 min after (b) the application of hydroxylamine; EPSP was not depressed 5 min (d) after depolarizing current (c), and remained constant also 40 min after the washout of the drug (e). The dotted line indicates the RMP (−84 mV).D, Traces represent a single experiment showing that EPSP amplitude recorded under control condition (a) was depressed 10 min after (b) the application of t-ACPD, DA, and hydroxylamine; the EPSP was depressed 5 min (d) after the depolarizing current (c), and the depression persisted also 40 min after the washout of the drugs (e). Thedotted line indicates the RMP (−83 mV). Thearrow represents the application of depolarizing current. In Bc, Cc, and Dcthe action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

Intracellular application of ODQ blocks the pharmacological LTD

To show the specificity of hydroxylamine as a NO donor in our slice preparation, we have used intracellular application of ODQ, a selective inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, the enzyme that is stimulated by NO (Garthwaite et al., 1995). In five of five experiments, after 15–20 min of recording with 100 μmODQ-filled electrodes, the coadministration of 30 μm DA, plus 20 μmt-ACPD and 1 μmhydroxylamine in association with current-induced membrane depolarizations was unable to generate LTD (data not shown). ODQ did not alter per se the EPSP amplitude.

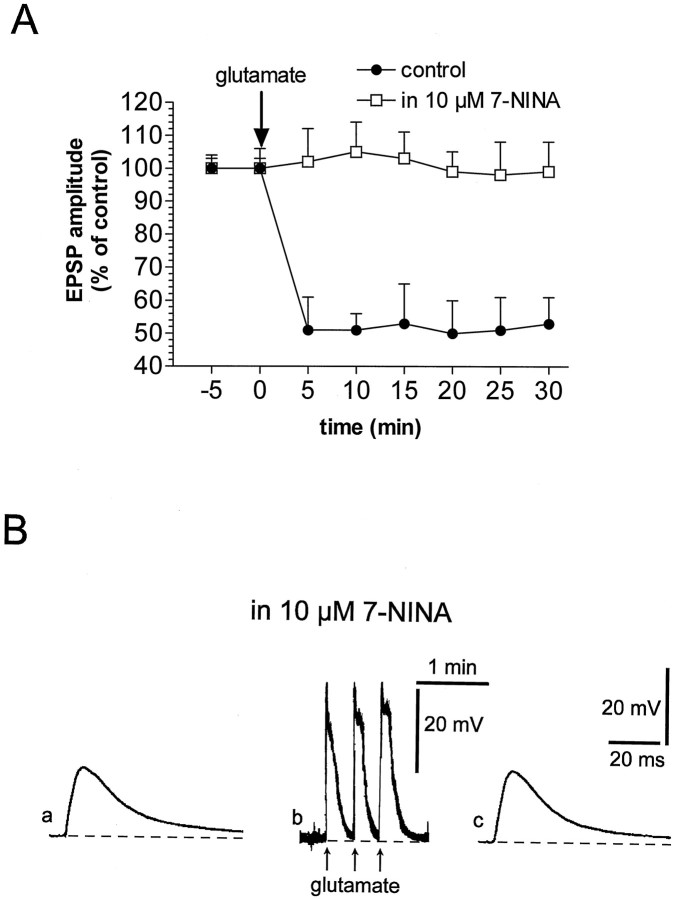

Effect of 7-NINA on glutamate-induced LTD

To demonstrate that the release of NO is required for chemically induced LTD, it is crucial to show that a NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor blocks this form of synaptic plasticity as well as the HFS-induced depression (Calabresi et al., 1999). To address this point we have incubated the slices in the presence of 10 μm 7-NINA, a selective inhibitor of neuronal NOS isoform (Moore and Handy, 1997). This inhibitor induced per se neither changes of EPSP amplitude nor alterations of the intrinsic membrane properties of the recorded neurons (data not shown, n = 10). However, preincubation of the slices in the presence of 10 μm7-NINA fully prevented the induction of LTD by focal application of glutamate (Fig. 7; n = 10). In the presence of 7-NINA (10 μm; 7–10 min), the amplitude and the duration of the membrane depolarizations induced by the focal applications of glutamate (37 ± 5 mV amplitude; 11 ± 5 sec duration; n = 10) were similar to those obtained in control solution and required for the induction of LTD.

Fig. 7.

The NOS inhibitor 7-NINA prevents glutamate-induced LTD. A, The plot shows that, differently than in control condition (filled circles), in the presence of 7-NINA the induction of corticostriatal LTD by focal application of glutamate was prevented (open squares). B, Traces represent a single experiment showing that EPSP amplitude, recorded in the presence of 7-NINA (a), was not affected 30 min after (c) the focal application of glutamate (b). The dotted line indicates the RMP (−86 mV). In Bb the action potentials on the top of the membrane depolarization have been truncated.

Lack of long-term effects of the various pharmacological treatments on intrinsic membrane properties of striatal spiny neurons

We measured the resting membrane potential (Vm) and input resistance (Rm) before and 15 min after the application of the various pharmacological compounds used to characterize the mechanisms underlying corticostriatal LTD. As shown in Table 1, none of these pharmacological treatments induced long-term changes of these measured intrinsic membrane properties.

Table 1.

Lack of long-term effects of various pharmacological treatments on intrinsic membrane properties of striatal spiny neurons

| Drug | Preinduction | 15′ postinduction | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vm(mV) | Rm (MΩ) | Vm(mV) | Rm (MΩ) | ||

| Glutamate | 83 ± 3 | 40 ± 7 | 82 ± 4 | 38 ± 8 | >0.05 |

| Quisqualate | 84 ± 4 | 38 ± 5 | 85 ± 5 | 39 ± 7 | >0.05 |

| AMPA | 84 ± 3 | 38 ± 6 | 83 ± 4 | 39 ± 7 | >0.05 |

| t-ACPD | 83 ± 4 | 40 ± 8 | 81 ± 5 | 41 ± 9 | >0.05 |

| AMPA +t-ACPD | 86 ± 6 | 37 ± 10 | 85 ± 7 | 37 ± 9 | >0.05 |

| l-sulpiride | 85 ± 5 | 37 ± 6 | 85 ± 6 | 38 ± 7 | >0.05 |

| t-ACPD + DA | 84 ± 5 | 38 ± 8 | 85 ± 7 | 39 ± 7 | >0.05 |

| Hydroxylamine | 86 ± 7 | 39 ± 9 | 85 ± 4 | 40 ± 9 | >0.05 |

| t-ACPD + DA + Hydroxylamine | 84 ± 6 | 37 ± 8 | 83 ± 7 | 38 ± 8 | >0.05 |

| Intracellular ODQ | 84 ± 5 | 40 ± 8 | 84 ± 6 | 41 ± 8 | >0.05 |

| 7-NINA | 85 ± 4 | 38 ± 8 | 85 ± 5 | 37 ± 9 | >0.05 |

For each experimental condition, data were collected from at least five single experiments. See text for drug concentrations.

DISCUSSION

Role of glutamate

The main finding of the present study is that corticostriatal LTD can be induced by the focal application of glutamate as well as by the tetanic stimulation of glutamatergic corticostriatal fibers. We have also shown that glutamate-induced LTD and HFS-induced LTD were mutually occlusive, indicating that these two forms of synaptic plasticity share common induction mechanisms. These data are of particular interest because they represent the first direct demonstration that, under physiological conditions, the release of glutamate from corticostriatal terminals is the only necessary and sufficient event for the induction of LTD. Other voltage- and ligand-dependent events are secondary to the action of this transmitter on its receptors. Moreover, we confirmed and extended the previous findings, suggesting that glutamate acts simultaneously on iGluRs and mGluRs to generate corticostriatal LTD. In fact, isolated activation of non-NMDA-iGluRs and mGluRs, respectively, by AMPA and t-ACPD, did not produce significant long-term changes of corticostriatal excitatory transmission, whereas a stable LTD was obtained after the exogenous application of either AMPA plust-ACPD or quisqualate, which is considered to be a mixed iGluR and mGluR agonist (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995).

Role of DA

Similarly to the HFS-induced LTD, glutamate-induced LTD is blocked by the selective DA D2 receptor antagonist l-sulpiride, indicating that the activation of this receptor subtype by endogenous DA plays an important role in both forms of LTD. It is possible that the spontaneous release of DA may be sufficient to activate the D2 receptors that are required for corticostriatal LTD. Alternatively, the data obtained in the present study seem to suggest that the release of DA during the conditioning phase of LTD is secondary to the activation of presynaptic glutamate receptors and not to the simultaneous stimulation of glutamatergic and DAergic fibers by the conditioning tetanus. This is in good agreement with the finding that DAergic fibers bear iGluRs on their terminals, whose activation augments the release of DA within the striatum both in vitro and in vivo studies (Cheramy et al., 1986; Carter et al., 1988; Clow and Jhamandas, 1989; Imperato et al., 1990; Moghaddam et al., 1990;Carrozza et al., 1992; Keefe et al., 1992; Westerink et al., 1992;Morari et al., 1993). In a recent in vivo microdialysis study it has been suggested that also mGluRs augment striatal DA release through presynaptic mechanisms (Verma and Moghaddam, 1998). It is also possible, however, that the major action of mGluR activation in the induction of corticostriatal LTD is not the modulation of DA release from nigral terminals but the stimulation of second messenger formation in striatal cells. Accordingly, postsynaptically located mGluRs leading to the stimulation of phosphoinositide hydrolysis have been demonstrated in striatal neurons (Pisani et al., 1997b) and striatal LTD can be blocked by chronic lithium treatment (Calabresi et al., 1993b), a procedure which is presumed to alter the phosphoinositide cycle (Berridge, 1993). Interestingly, D2 DA receptors and mGluRs may converge on the same postsynaptic metabolic pathway to regulate intracellular Ca2+ levels and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate production (Clapham, 1995).

Role of membrane depolarization

Voltage-clamp experiments showed that a critical membrane depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron, produced by the activation of iGluRs, is a crucial step for the induction of corticostriatal LTD. Accordingly, when glutamate was applied during voltage-clamp recordings, no LTD was detected. Nevertheless, the current-induced depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron alone failed to induce LTD although it triggered a sustained firing activity. This finding indicates that a rise of intracellular Ca2+represents a critical but not a sufficient condition to generate corticostriatal plasticity. Interestingly, current-evoked depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron failed to cause LTD, even when associated with exogenous application of mGluR agonists and DA. The failure of LTD induction after depolarization of the postsynaptic cell in the presence of t-ACPD and DA strongly suggests the participation of an additional factor in the generation of corticostriatal LTD.

Role of NO

In the present study we demonstrate that this additional factor is represented by NO. In fact, a low dose of hydroxylamine, that per se did not modify EPSP amplitude, was able to generate LTD after postsynaptic depolarization when coadministrated with DA andt-ACPD. Accordingly, the inhibition of neuronal NOS by 7-NINA prevented the formation of LTD after focal glutamate application. These findings represent the first functional demonstration that NO, DA, and glutamate act in concert to produce a long-term physiological event in the mammalian brain. In the striatum, this functional interaction is well supported by anatomical observations. NOS-positive aspiny interneurons represent the source of striatal NO (Bredt et al., 1991; Vincent and Kimura, 1992). They receive both cortical glutamatergic afferents (Vuillet et al., 1989) and synaptic contacts from DAergic fibers (Fujiyama and Masuko, 1996). NOS-positive interneurons can release also other neuroactive substances such as somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and GABA, depending on the pathway of firing activity. However, the release of NO seems to occur only during prolonged depolarizations (Kawaguchi et al., 1995). Thus, HFS- and glutamate-induced membrane depolarizations may represent the most effective manner to cause the sustained stimulation required for NO release by these neurons. It has been reported that the endogenous NO facilitates striatal DA and glutamate release in vivo(West and Galloway, 1997). Thus, we can speculate that the exogenous glutamate applications we have used in the present study to induce LTD may also increase the release of DA by an indirect mechanism which involves NO. This positive feedback, in conjunction with postsynaptic membrane depolarization, may lead to the intracellular biochemical changes in the spiny neuron required for LTD formation. We have recently shown that either high concentrations of NO donors or experimental conditions that elevates intracellular postsynaptic cGMP levels in the spiny neuron are able to induce per se LTD even in the absence of HFS or of membrane depolarization of postsynaptic neuron (Calabresi et al., 1999). We hypothesize that these extreme pharmacological conditions may bypass the requirement of the other synergistic factors such as the postsynaptic membrane depolarization, and the activation of both DA receptors and mGluRs. This latter observation suggests that the final step for LTD induction is an elevation of intracellular levels of cGMP.

Our experiments have also shown that the membrane depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron is critical for the induction of LTD even in the presence of the three pharmacological classes of drugs: DA,t-ACPD, and low dose of hydroxylamine. Accordingly, coadministration of these compounds in the absence of membrane depolarization produced only a transient depression of the EPSP. It is possible that activation of both DA receptors and mGluRs as well as the increase of intracellular cGMP levels (achieved by NO production) converge to produce critical intracellular biochemical changes. However, only in the presence of a large rise of intracellular Ca2+ obtained by the membrane depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron these biochemical changes are enabled to generate LTD.

The ability of intracellular ODQ, a selective inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase (Garthwaite et al., 1995), to prevent the formation of LTD induced by current-induced membrane depolarizations in the presence of 30 μm DA, 20 μmt-ACPD, and 1 μm hydroxylamine, supports the specificity of this latter compound as a NO donor. Moreover, it clearly shows that the soluble guanylyl cyclase responsible of the increase in cGMP levels is postsynaptically located in spiny neurons.

Comparison with cerebellar LTD

Corticostriatal and cerebellar LTD share several common induction mechanisms. A rise of intracellular Ca2+ is required for both of them. Accordingly, Ca2+-chelating agents injected into the postsynaptic neuron block both forms of plasticity. Moreover, stimulation of a Ca2+-dependent enzyme such as PKC is critical for both these forms of synaptic plasticity. In the striatum as well as in the cerebellum, activation of mGluRs is supposed to be responsible for PKC activation. Similarly, activation of the NO/cGMP pathway is required for cerebellar and striatal LTD. In both these structures, this pathway leads to the activation of protein kinase G in the postsynaptic recorded neuron (i.e., the striatal spiny neuron and the Purkinje cell) rather than to be involved at a presynaptic level. This mechanism seems to suggest that in the striatal as well as in the cerebellar LTD, NO operates via a feedforward mechanism rather than as a retrograde messenger. Finally, in both forms of LTD, activation of NMDA receptor is not required, and the final postulated mechanism for their expression is the desensitization of AMPA receptor (Daniel et al., 1998; Calabresi et al., 1999). It is worth noting that the distinctive feature of striatal LTD in comparison with cerebellar LTD is the critical participation of DA receptors.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Ministero dell’Universitá e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST Cofinanziamento) grant and a BIOMED grant (BMH4-97-2215) to P.C., and by a MURST-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (legge 95/95) grant to G.B. We thank M. Tolu for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Paolo Calabresi, Clinica Neurologica, Laboratorio di Neuroscienze, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze, Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia, Università degli Studi di Roma, Tor Vergata, Via di Tor Vergata, 135–00133, Roma, Italia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge MJ. A tale of two messengers. Nature. 1993;365:388–389. doi: 10.1038/365388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bredt DS, Glatt CE, Hwang PM, Fotuhi M, Dawson T, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide synthase protein and mRNA are discretely localized in neuronal populations of the mammalian CNS together with NADPH-diaphorase. Neuron. 1991;7:615–624. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabresi P, De Murtas M, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Kainic acid on neostriatal neurons intracellularly recorded in vitro: electrophysiological evidence for differential neuronal sensitivity. J Neurosci. 1990a;10:3960–3969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03960.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabresi P, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Synaptic and intrinsic control of membrane excitability of neostriatal neurons.II. An in vitro analysis. J Neurophysiol. 1990b;63:663–675. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calabresi P, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Synaptic and intrinsic control of membrane excitability of neostriatal neurons.I. An in vivo analysis. J Neurophysiol. 1990c;63:651–662. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calabresi P, Maj R, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Long-term synaptic depression in the striatum: physiological and pharmacological characterization. J Neurosci. 1992a;12:4224–4233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04224.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Long-term potentiation in the striatum is unmasked by removing the voltage-dependent blockade of NMDA receptor channel. Eur J Neurosci. 1992b;4:929–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Heterogeneity of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the striatum: electrophysiological evidence. Eur J Neurosci. 1993a;5:1370–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Lithium treatment blocks long-term synaptic depression in the striatum. Neuron. 1993b;10:955–962. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90210-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Post-receptor mechanisms underlying striatal long-term depression. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4871–4881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04871.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabresi P, Fedele E, Pisani A, Fontana G, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G, Raiteri M. Transmitter release associated with long-term synaptic depression in rat corticostriatal slices. Eur J Neurosci. 1995a;7:1889–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabresi P, De Murtas M, Pisani A, Stefani A, Sancesario G, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Vulnerability of medium spiny striatal neurons to glutamate: role of Na+/K+ ATPase. Eur J Neurosci. 1995b;7:1674–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. The corticostriatal projection: from synaptic plasticity to basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81862-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabresi P, Saiardi A, Pisani A, Baik J-H, Centonze D, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G, Borrelli E. Abnormal synaptic plasticity in the striatum of mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4536–4544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04536.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calabresi P, Centonze D, Gubellini P, Pisani A, Bernardi G. Blockade of M2 muscarinic receptors enhances long-term potentiation at corticostriatal synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3020–3023. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1998.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calabresi P, Gubellini P, Centonze D, Sancesario G, Morello M, Giorgi M, Pisani A, Bernardi G. A critical role of the NO/cGMP pathway in corticostriatal long-term depression. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2489–2499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02489.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrozza DP, Ferraro TN, Golden GT, Reyes PF, Hare TA. In vivo modulation of excitatory amino acid receptors: microdialysis studies on N-methyl-d-aspartate-evoked striatal dopamine release and effects of antagonists. Brain Res. 1992;574:42–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90797-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter CJ, L’Heureux R, Scatton B. Differential control by N-methyl-d-aspartate and kainate of striatal dopamine release in vivo: A trans-striatal dialysis study. J Neurochem. 1988;51:462–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cepeda C, Walsh JP, Peacock W, Buckwald NA, Levine MS. Neurophysiological, pharmacological and morphological properties of human caudate neurons recorded in vitro. Neuroscience. 1994;59:89–103. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheramy A, Romo R, Godeheu G, Baruch P, Glowinski J. In vivo presynaptic control of dopamine release in the cat caudate nucleus-II. Facilitatory or inhibitory influence of l-glutamate. Neuroscience. 1986;19:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S, Lovinger DM. Decreased probability of neurotransmitter release underlies striatal long-term depression and postnatal development of corticostriatal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2665–2670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 1995;80:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clow DW, Jhamandas K. Characterization of l-glutamate action on the release of endogenous dopamine from the rat caudate-putamen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;284:722–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniel H, Levenes C, Crépel F. Cellular mechanisms of cerebellar LTD. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiyama F, Masuko S. Association of dopaminergic terminals releasing nitric oxide in the rat striatum: an electron microscopic study using NADPH-diaphorase histochemistry and tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry. Brain Res Bull. 1996;40:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garthwaite J, Southam E, Boulton CL, Neilsen EB, Schmidt K, Mayer B. Potent and selective inhibition of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase by 1-H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalyn-1-one. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horikawa H, Armstrong WE. A versatile means of intracellular labelling: injection of biocytin and its detection with avidin conjugates. J Neurosci Methods. 1988;25:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(88)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imperato A, Honoré T, Jensen LH. Dopamine release in the striatum and in the nucleus accumbens is under glutamatergic control through non-NMDA receptors: a study in freely moving rats. Brain Res. 1990;530:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91286-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito M. Long-term depression. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:85–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurones: chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keefe KA, Zigmond MJ, Abercrombie ED. Extracellular dopamine in striatum: influence of nerve pulse activity in median forebrain bundle and local glutamatergic input. Neuroscience. 1992;47:325–332. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kita T, Kita H, Kitai ST. Passive electrical membrane properties of rat neostriatal neurons in an in vitro slice preparation. Brain Res. 1984;300:129–139. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovinger DM, Tyler EC, Merrit A. Short- and long-term synaptic depression in the neostriatum. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1937–1949. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moghaddam B, Gruen RJ, Roth RH, Bunney BS, Adams RN. Effect of l-glutamate on the release of striatal dopamine: in vivo dialysis and electrochemical studies. Brain Res. 1990;518:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore PK, Handy RLC. Selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase - is no NOS really good NOS for the nervous system? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:204–211. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morari M, O’Connor WT, Ungerstedt U, Fuxe K. N-methyl-d-aspartic acid differentially regulates extracellular dopamine, GABA and glutamate levels in the dorsolateral neostriatum of the halothane-anesthetized rat: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1884–1893. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pin JP, Duvoisin R. Neurotransmitter receptors I. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pisani A, Calabresi P, Centonze D, Bernardi G. Activation of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors depresses glutamatergic transmission at corticostriatal synapse. Neuropharmacology. 1997a;36:845–851. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisani A, Calabresi P, Centonze D, Bernardi G. Enhancement of NMDA responses by group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in striatal neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1997b;120:1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Southam E, Garthwaite J. Comparative effects of some nitric oxide donors on cyclic GMP levels in rat cerebellar slices. Neurosci Lett. 1991;130:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90239-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teyler TJ, Discenna P. Long-term potentiation as a candidate mnemonic device. Brain Res Rev. 1984;7:15–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma A, Moghaddam B. Regulation of striatal dopamine release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Synapse. 1998;22:220–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199803)28:3<220::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vincent SR, Kimura H. Histochemical mapping of nitric oxide synthase in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 1992;46:755–784. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vuillet J, Kerkerian L, Kachidian P, Bosler O, Nieoullon A. Ultrastructural correlates of functional relationships between nigral dopaminergic or cortical afferent fibers and neuropeptide Y-containing neurons in the rat striatum. Neurosci Lett. 1989;100:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90667-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh JP. Depression of excitatory input in rat striatal neurons. Brain Res. 1993;608:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90782-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West AR, Galloway MP. Endogenous nitric oxide facilitates striatal dopamine and glutamate efflux in vivo: role of ionotropic glutamate receptor-dependent mechanisms. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1571–1581. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westerink BHC, Santiago M, de Vries JB. The release of dopamine from nerve terminals and dendrites of nigrostriatal neurons induced by excitatory amino acids in the rat. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1992;345:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF00168943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wickens JR, Begg AJ, Arbuthnott GW. Dopamine reverses the depression of rat cortico-striatal synapses which normally follows high frequency stimulation of cortex in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;70:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00436-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson CJ, Groves PM. Fine structure and synaptic connections of the common spiny neuron of the rat neostriatum: a study employing intracellular inject of horse-radish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:599–615. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]