Abstract

Background

Self-harm and suicide are major public health concerns. Self-harm is the strongest risk factor for suicide, with the highest suicide rates reported in older populations. Little is known about how older adults access care following self-harm, but they are in frequent contact with primary care.

Aim

To identify and explore barriers and facilitators to accessing care within primary care for older adults who self-harm.

Design and setting

An exploratory qualitative methods study using semi-structured interviews with older adults and third-sector workers in England. Older adults were invited to participate in one follow-up interview.

Method

Interviews occurred between September 2017 and September 2018. These were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and data analysed thematically. A patient and public involvement and engagement group contributed to the study design, data analysis, and interpretation.

Results

A total of 24 interviews with nine older adults and seven support workers, including eight follow-up interviews with older adults, were conducted. Three themes emerged: help-seeking decision factors; sources of support; and barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care.

Conclusion

Despite older adults’ frequent contact with GPs, barriers to primary care existed, which included stigma, previous negative experiences, and practical barriers such as mobility restrictions. Older adults’ help-seeking behaviour was facilitated by previous positive experiences. Primary care is a potential avenue for delivering effective self-harm support, management, and suicide prevention in older adults. Given the complex nature of self-harm, there is a need for primary care to work with other sectors to provide comprehensive support to older adults who self-harm.

Keywords: deliberate self-harm, frail older adults, primary care, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Self-harm is a major public health concern and the leading risk factor for suicide.1 Defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as ‘… any act of self-poisoning or self-injury … irrespective of motivation’,1 self-harm prevention and management are NHS priorities.2 While self-harm rates among older populations are not as high when compared with younger populations, the subsequent risk of suicide is higher.3,4 Furthermore, increased treatment costs exist when treating older adults who self-harm owing to complications caused by comorbidities.5 The authors’ previous work6 suggests self-harm holds several functions for older adults and suicidal intent is not the only reason they engage in such behaviour, as traditionally reported.4 Accounts of older adults using self-harm as a coping mechanism throughout the life course suggest the need for a more nuanced approach to intervening and providing support than one principally focused on suicide prevention.

Older adults are in frequent contact with primary care owing to comorbid health conditions, and thus GPs may potentially offer support and management to older adults with self-harm behaviour.3–4 NICE guidance suggests multiagency approaches to self-harm management,1 including support from the health sector and liaison with other agencies such as the social and third sector. Yet little is known about the avenues older adults find acceptable and/or take when asking for self-harm support. In addition to older adults’ contact with primary care, individuals also access the third sector in order to receive mental health care, including for self-harm behaviour.7 Moreover, there is evidence that the third sector has a potential role in providing care coordination for older adults.8

Existing literature exploring self-harm in older adults is mostly limited to quantitative designs,4 yet accounts of lived experiences are essential to understand complex behaviours such as help-seeking among older populations. This study will explore access to care for older adults who self-harm and the implications for primary care. The authors intend to identify and explore the barriers and facilitators to primary care from the perspectives of older adults with self-harm history and from third-sector support workers with experiences of working with them.

How this fits in

| Self-harm is the leading risk factor for suicide, with suicide being an increasing concern among older populations given the high suicide rates reported. Though research has shown that older adults who self-harm are in frequent contact with primary care owing to complex health conditions, to the authors’ knowledge, no research has explored the role of primary care in supporting this group. Using a qualitative approach, the presented study’s findings confirm that primary care is a potential avenue for effective self-harm management in older adults, and GPs are in a good position to manage and support older adults who self-harm. However, given the complex nature of self-harm, primary care may wish to work with other sectors (health, social, and third sectors) to comprehensively support older adults who self-harm, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. |

METHOD

This study had a qualitative methods approach, using in-depth semi-structured interviews to explore self-harm in older adults. It was carried out in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).

Setting and participants

Research participants were older adults (aged ≥60 years) who disclosed recent self-harm acts as defined by NICE,1 and third-sector support workers (defined as support workers working at a third-sector organisation: either self-harm or older adults support group) with experience of supporting older adults who self-harm.

Recruitment

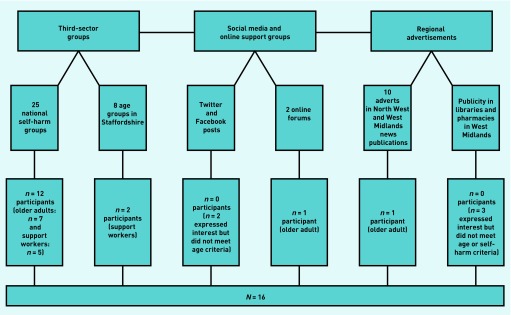

Participants were recruited in England using various strategies including: third-sector groups, social media, online support groups, and regional advertisement. Purposive sampling was applied. For older adults contacted through the third sector, initial contact was made with the group’s manager to inform them about the study and ascertain if they would be willing to share the study’s information with members. Where the group’s manager found it appropriate, one author, a mental health doctoral researcher, visited the third-sector group to provide details of the study in person. The same process was followed for support workers contacted through third-sector groups. Contact with older adults and support workers through social media, online support groups, and regional advertisement was made by posting study recruitment posters as summarised in Figure 1. After confirming eligibility criteria, participants were supplied with information sheets explaining study details. Face-to-face interviews were arranged at a time and venue preferred by participants (Keele University, third-sector venue, or participants’ home) with the option of telephone interviews.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment methods.

Data collection

Interviews took place between September 2017 and September 2018, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Alongside collection of field notes, an interview topic guide, developed from the literature and with the advice of the patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) group, was used. A separate topic guide was used for older adults and support workers, but they both collected participant sociodemographic data, information about self-harm history (of either older adult participants or older adults supported by support workers), motivations, and access to care. Participants were encouraged to elaborate as extensively as possible in their accounts.9–11 Follow-up interviews were offered to older adults given the sensitive nature of the topic. In doing so, participants had time to reflect on their initial interview and make decisions on whether or not they wished to expand or amend anything they might have referred to. It was also intended as a means to allow time to establish rapport11 as well as to further explore emerging themes. One author conducted all interviews.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of each interview and checked again at the end. All participants had the opportunity to ask questions before signing the consent form. Participants’ informed consent was again separately obtained for follow-up interviews.

Analysis

Thematic analysis using principles of constant comparison was used to analyse data following an inductive approach.12–13 NVivo (version 11) software was used to facilitate data analysis. Initial analysis was conducted within each participant group, with separate coding themes and categories created for each. After coding, creating, and revising the initial themes, they were compared and contrasted across both datasets in order to integrate the overall findings. Analysis followed an iterative process, where each interview was coded before new data generation. Initial codes were further explored in subsequent interviews. Data saturation14 was reached when analysis indicated no new themes from both participant groups and thus recruitment ceased.

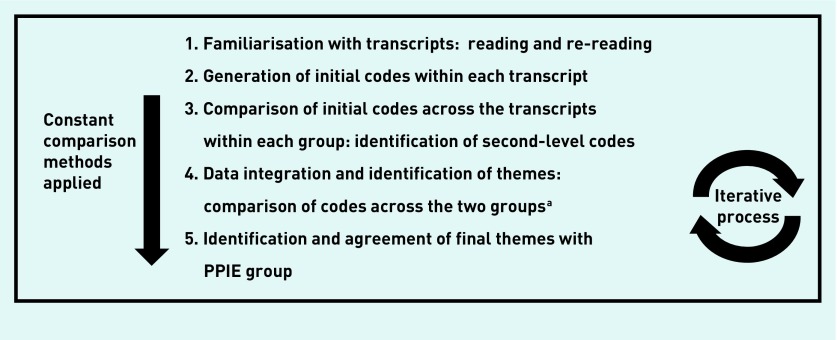

Figure 2 provides a summary of data analysis. One author led the process, with all transcripts independently coded by at least two authors. Coding and emerging themes were then discussed among five authors, each contributing their disciplinary perspectives to deepen the interpretation. This multidisciplinary process, alongside input from the PPIE group described later, contributed to trustworthiness of data.15–16

Figure 2.

Summary of data analysis process.

aThe research team discussed interpretation if adjustment of analysis was needed when data were inconsistent with initial analysis. PPIE = patient and public involvement and engagement.

Patient and public involvement and engagement group

This study was conducted in collaboration with a PPIE group that contributed to the development and refinement of recruitment strategies, analysis of data, and dissemination plan.17 All PPIE members were aged ≥60 years and included older adults with self-harm history, carers, and third-sector workers. The group was consulted on five occasions throughout the 3-year duration of the research.

RESULTS

A total of 24 interviews were conducted with 16 participants: nine older adults and seven support workers. Eight older adults consented to a follow-up interview. All interviews lasted from 28 to 129 minutes. Tables 1 and 2 provide a summary of participant sociodemographic and other characteristics. All older adults had comorbid physical and mental health problems, and over half (n = 4) of the support workers had previous self-harm history. Three major themes were identified throughout participants’ accounts: help-seeking decision factors; sources of support; and barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care. The following illustrative quotations are used to present details of the theme, before turning to look at the implications for intervention, management, and support.

Table 1.

Characteristics of older adults

| Patient ID | Sex | Ethnicity | Age, years | Health conditionsa | Psychosocial contexta | Start of self-harm | Supporta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F | White British | 62 |

|

|

Early teens |

|

| F2 | F | White British | 72 |

|

|

Early childhood |

|

| F3 | F | White British | 60 |

|

|

Early teens |

|

| M1 | M | White British | 67 |

|

|

40s |

|

| F4 | F | White British | 65 |

|

|

40s |

|

| F5 | F | White British | 62 |

|

|

60s |

|

| M2 | M | White British | 61 |

|

|

40s |

|

| F6 | F | Ethnic minority British | 62 |

|

|

Early childhood |

|

| M3 | M | White American | 60 |

|

|

Early childhood |

|

As reported by participants. CPN = community psychiatric nurse. F = female. ID = identifier. M = male.

Table 2.

Characteristics of support workers

| Participant ID | Sex | Age, years | Rolea | Personal background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F7 | F | 46 | Volunteer lead at self-harm charity |

|

| F8 | F | 36 | Support worker at self-harm third-sector group |

|

| F9 | F | 52 | Support worker at self-harm third-sector group |

|

| F10 | F | 49 | Main facilitator at self-harm third-sector group |

|

| F11 | F | 40 | Support worker at older adults’ third-sector group |

|

| M4 | M | 42 | Support worker at older adults third-sector group |

|

| M5 | M | 50 | Main facilitator at self-harm third-sector group |

|

As identified by participants. ID = identifier. F = female. M = male.

Help-seeking decision factors

Older adults experienced self-harm throughout different stages of the life course. However, it was often hidden:

‘Obviously, it [self-harm in older adults] does happen, but it’s hidden.’

(Male older adult [MOA], aged 60 years, M3 [patient identifier])

Both participant groups mentioned older adults deciding to seek help during different periods in the life course. However, these decisions were seen as difficult, sometimes occurring months or years after starting self-harm behaviour. Experiencing shame due to self-harm was seen by both groups as a key deterrent in accessing support, and they linked it to the stigma associated with mental health and self-harm, which they perceived as accentuated further among older adults:

‘It’s harder for older people to talk about their mental health. You can imagine more so with self-harm.’

(Female support worker [FSW], aged 40 years, F11)

‘It’s just that you are ashamed of some of it [self-harm], so it’s harder to talk about it and ask for help.’

(Female older adult [FOA], aged 60 years, F3)

However, older adults and support worker participants identified self-harm behaviour as reaching a point where it was out of control and was no longer serving as a coping mechanism. Once this point was reached, older adults made the decision to seek help, recognising they needed support:

‘I think a lot of people only turn to help if it’s sorta uh, when it gets out of control, so that I suppose, eventually, they just reach out for some help.’

(FSW, aged 49 years, F10)

‘It wasn’t that I wanted help, I needed [emphasis] help, I couldn’t deal with it any longer.’

(FOA, aged 72 years, F2)

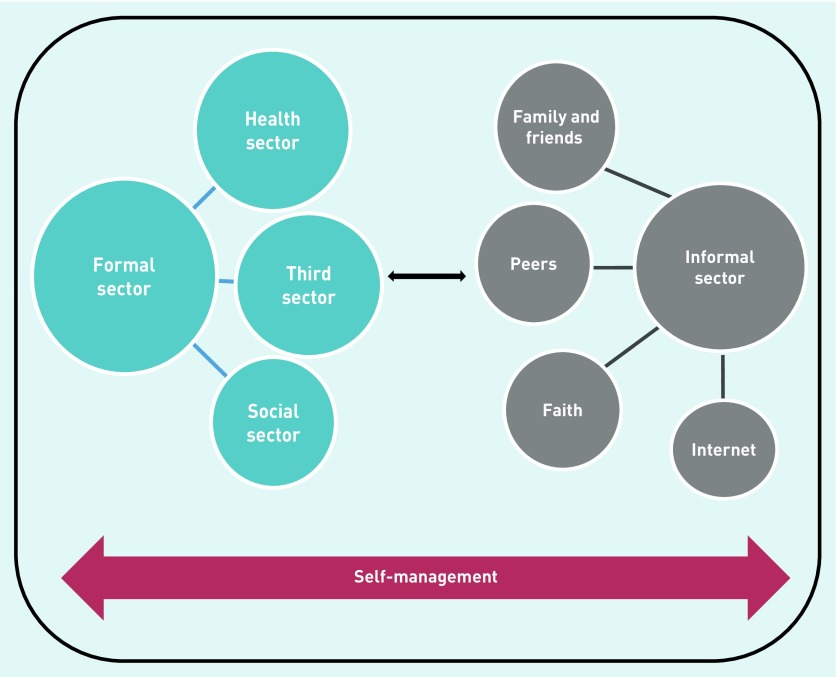

Sources of support

Older adults used different avenues to access support for their self-harm, both in the formal and informal sector as summarised in Figure 3, though there were periods when older adults lived with self-harm behaviour without accessing support. These avenues were interconnected and used interchangeably through different stages of the help-seeking process, depending on needs at particular moments. Furthermore, older adults relied on self-management strategies when waiting to receive care.

Figure 3.

Support avenues for older adults with self-harm behaviour.

Both participant groups mentioned the third sector as a commonly used source of support, particularly self-harm support groups, where they could access peer support as well as help from support workers. Over half of the support workers reported self-harm history that made the support given to and experienced by older adults more valuable:

‘ [Support worker] is brilliant cause you can contact him anytime, and he’s always there. You can talk to him, he understands as he’s experienced it himself. All members say that, it’s real support. I only met the group via [organisation], otherwise you’re on your own.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F6)

The majority of older adults recounted how they were referred to the third sector by healthcare professionals. Similarly, support workers narrated how the majority of people accessing support from the third sector had been referred by GPs:

‘GPs have rung me in the past so they could refer their patients to our group.’

(Male support worker [MSW], aged 50 years, M5)

Primary care was also commonly mentioned as an avenue for self-harm support, with participants explaining that GPs offered support and, in some instances, helped them manage their self-harm. However, this support was not only exclusive to self-harm management but also focused on treating comorbid conditions. The complex nature of the consultations and its implications for help-seeking can be seen within the context of both barriers and facilitators.

Barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care support

Different barriers to accessing primary care support existed for older adults who self-harm.

As noted previously, feelings of shame and stigma were commonly described, leading older people to live with self-harm in secret, prolonging or delaying the process of help-seeking:

‘They’ll [older adults] mention the physical health to the GP but won’t always mention their self-harm or mental health.’

(FSW, aged 40 years, F11)

Stigma associated with self-harm could still be present and act as a barrier to accessing care even after older adults had made the decision to seek help:

‘I felt embarrassed because of me age, I didn’t wanna ask for help. I’m thinking it’s girls that do it, 16, 17-year-olds you know and they’re self-harming and here is me you know, I should know better.’

(MOA, aged 67 years, M1)

Furthermore, older adults described GPs’ lack of interest to self-harm in older adults, reflecting stigma associated with self-harm by clinicians:

‘You tell them [doctors] and they’re not interested about self-harm. I’ve seen it myself, anyone that comes in with mental health problems they’re just dismissed. It’s still something not taken seriously, like it will go away or grow out of it. When the truth is, you don’t grow out of it if you don’t receive the help.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F6)

For some older adults, this reflected a lack of trust in their GPs’ ability to help:

‘Most GPs don’t know how to deal with it, much less from an older adult, and much less from a functioning adult.’

(MOA, aged 60 years, M3)

In addition to perceptions that GPs lack expertise, older adults often felt their encounters with GPs were superficial, and described support as mostly pharmacological, with provision of psychological therapies not common practice. This was despite the high level of GP involvement reflected in frequent and regular consultations:

‘Well, I got the medication from my GP and it was a case of seeing him once a week to see how it was affecting me. Now I get a review every 6 months.’

(FOA, aged 72 years, F2)

Such treatments were viewed as insufficient to deal with the complexities of self-harm:

‘There are lots of doctors that just want to pill pop [snaps fingers], here have a pill. That just masks it. You’re just skimming over it, you’re not talking to them. There’s things in people’s heads that a pill doesn’t take. And you know some doctors don’t understand mental health, don’t understand self-harm. And there is people out there that take overdoses and they’re not given the correct support.’

(FSW, aged 46 years, F7)

This sense of superficial engagement on the part of GPs could deepen feelings of personal inadequacy and illegitimacy:

‘You’re just a number. Once you’re out of the bed or consultation room, someone else is gonna come, so to the nurses and doctors you’re just a number.’

(MOA, aged 67 years, M1)

Linked to this, some older adults’ accounts of their experiences with GPs had a predominant focus on treating physical wounds resulting from self-harm, and their overall physical health, reflecting a prioritisation of the physical over mental health:

‘He [GP] just kept looking at his watch. I thought, I don’t want that doctor again, because all he was interested was his watch. He was interested in my physical ability. He was interested in mending me physically but not mentally. And I’ve found that with a lot of the doctors. You try and tell them you need help mentally but all they see and care is your physical abilities.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F6)

This prioritisation of the physical over the mental could also be on the part of the older person themselves:

M2: ‘I do see me GP frequently but it’s mainly for other things like blood tests and these sorts of things.’

Interviewer: ‘Is there any reason why you don’t talk about it with your GP?’

M2: ‘I’ve got so many other things that need to be checked, there just wouldn’t be time.’

(MOA, aged 61 years, M2)

Furthermore, this could be deepened by sex attitudes to health-seeking more generally:

‘As a male I tend to not go to the GP. It’s kind of being very appreciative of the NHS. I’m not someone to call the GP all the time and kinda go like, oh I wanna tell you this.’

(MOA, aged 60 years, M3)

When offered referrals by GPs, older adults described the support and treatment received consisting of short-term interventions, which left them feeling frustrated and discouraged them from seeking further help:

‘They’ll do something like 6-week counselling. But if at the end of the 6 weeks you still feel you’re struggling, then surely they should do something, have another source of support. I remember being told, well we’ve done the course, there’s nothing else we can do, uhm if you’re not feeling better, that’s your problem.’

(FOA, aged 65 years, F4)

Furthermore, support for self-harm was described as difficult to access as it was not seen as an urgent priority. Although some older adults spoke of an overemphasis on their physical health, some also experienced difficulties in accessing help at crisis points:

‘I cut my stomach and it was really quite bad. I phoned my GP, and nobody would see me, even though I had a priority plan. They said, come here tomorrow. I said, I need to see somebody now and they said, well we’ve got no appointments. So I phoned my CPN [community psychiatric nurse] and she said, well this priority care planning isn’t working, and she phoned them, and they called me straight away.’

(FOA, aged 65 years, F4)

According to older adults, mental health care was only provided for those who were very ill, as opposed to those who were not but were still in need of care:

‘I can’t see the point in it. They turn up and then they don’t do it. They don’t do anything that [it] says on the letter unless you’re absolutely completely and utterly mentally ill. Which is fair enough for those who are like that. Because they’re so stretched, they don’t do much for you unless you’re absolutely crawling up the walls.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F1)

Finally, older adults described practical barriers such as difficulties in travelling. Where people had mobility difficulties, it was not easy for them to travel independently, particularly in bad weather, which could have cost implications:

‘It costs me 20 pounds [GBP] to get there, which is a lot of money. So yeah, I just have to have to sit tight and wait for the snow to go. And then of course, you’ve got hospital appointments.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F1)

These barriers to accessing support often resulted in older people seeking support elsewhere:

‘He [older adult] was looking for some support because the GP basically didn’t know what to do, as is the case with many health professionals.’

(MSW, aged 50 years, M5)

Older adults encountered several barriers to obtaining support for managing their self-harm, including feelings of shame, sex and age attitudes, perceptions of competency on the part of GPs, prioritisation of physical over mental health needs, legitimacy in help-seeking, and physical barriers such as transport. Worries about stigma were an overarching barrier to accessing help.

Both participant groups also identified facilitators when receiving self-harm support in primary care. Empathy was one of the most frequently mentioned facilitators as well as reliability and continuity given by healthcare professionals, which could legitimise people’s help-seeking:

‘She [GP] was real for start. I felt as I was gonna see somebody I could talk to, as opposed as to somebody that was going to sit behind a desk and talk to me. As well, I didn’t feel like a burden.’

(FOA, aged 65 years, F4)

Taking the condition seriously conveyed respect:

‘You could see how they treated her, and they were absolutely amazing they just treated her so well. She was treated so respectfully.’

(FSW, aged 49 years, F10)

Linked to this, some older adults described the high impact from positive experiences of support from their GP:

‘I have to say my GP has been fantastic, she’s very good. Very caring, she listens. Which is, you know, some of them don’t, but she’s been fantastic. She’s given me all the literature for [local self-harm support group]. The last time when I went off, that’s when she said we need to change your medication, you’ve been on them too long. She’s very thorough. I couldn’t have asked for anything better.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F5)

Furthermore, older adults identified the importance of having regular and ongoing support as a facilitator to receiving care:

‘It’s the ongoing support. You’ve always got somebody you can contact. This ongoing support is really, really helpful.’

(FOA, aged 62 years, F5)

Finally, availability of accessible facilities made it easier for older adults to access support for their self-harm. Boxes 1 and 2 summarise the different barriers and facilitators to accessing primary care support for older adults with self-harm behaviour.

Box 1.

Barriers to accessing primary care for self-harm in older adults

| External factors |

|

| Practical barriers |

|

| Internal factors |

|

Box 2.

Facilitators to accessing primary care for self-harm in older adults

| External factors |

|

| Structural factors |

|

| Internal factors |

|

DISCUSSION

Summary

Older adults who self-harm may have comorbid and complex health conditions, which result in contact with primary care. However, help-seeking was often delayed because of feelings of shame caused by stigma associated with self-harm. Older adults and support workers identified continuity, regular support, and empathetic healthcare professionals as facilitators for accessing primary care. Alongside shame and stigma experiences, older adults’ own attitudes to primary care acted as barriers to accessing care. In addition, mobility restrictions and transport difficulties were also common barriers. Lastly, participants experienced an overmedicalised perspective of self-harm management and support, and reported a predominant GP interest in supporting physical health over a combined physical–mental health approach. However, this was often driven by older adults’ own expectations, formed partly as a result of their previous experiences.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study exploring older adults’ experiences accessing care for self-harm behaviour. Using qualitative methods, this study provides first-hand lived-experience accounts of older adults who self-harm. Through an ongoing collaboration and consultation with a PPIE group, this study included patient perspectives in the elaboration of the study design, data analysis, and interpretation, a further strength of this study.

This study has limitations. First, the small number of participants included may be considered a limitation. However, diverse perspectives were provided across participants’ accounts, and data collection ceased when no new themes emerged from each participant group. Future research could explore the perspectives of GPs on older adults’ self-harm to see whether the present findings are reflected in GPs’ experiences.

Finally, despite efforts to include a diverse sample, older adults from this study were confined to a younger age group (mean age 63.4 years; age range 60–72 years) and were mostly white British. The authors recognise that these findings may not be applicable to later life cohorts or ethnic minority groups.

Comparison with existing literature

Existing literature suggests primary care as a possible avenue for supporting and managing individuals who self-harm and preventing suicide.18–24 However, little is known about how primary care might support older adults who self-harm. A recent qualitative study conducted with Australian GPs found that GPs did not see a role for themselves in supporting older adults who self-harm given the complex contributing factors to self-harm.25 Complexities leading to self-harm in older adults include a range of social, health, and interpersonal problems, as identified in previous research.4,25 Research conducted with other populations engaging in self-harm suggests using alternative sources to support individuals who self-harm, including the third sector,8 and other agencies from the health sector. Though this study did not include GPs’ perspectives, findings emerging from older adults and third-sector workers confirm existing literature. Findings are congruent with the NICE guideline’s suggestion of multiagency partnerships between the health, social, and third sector,26 in order to offer comprehensive support to older adults who self-harm.

Similar barriers in accessing health care were found when compared with younger populations who self-harm.8,27–28 Reluctance to seek help in people who self-harm seems to be universal across all ages, with stigma primarily affecting help-seeking. However, when compared with younger populations, older adults contact primary care more often owing to their complex health conditions, making this frequent contact an opportunity for self-harm intervention, management, and support. Yet ageism among healthcare practitioners is an encountered problem that has shown to have a significant negative impact on mental health outcomes in older patients.29–30 Older participants expressed feeling unheard, and their self-harm and overall mental health was not considered in the consultation room.

In addition, their own expectations around physical and mental health and help-seeking in later life may also act as a further barrier to older people.28,31 Previous literature has explored how patients’ expectations and attitudes towards medical consultations can have an impact and influence the encounter.32–33 Findings from this study suggest this is also the case in older adults who self-harm. Some participants reported not seeking support from their GPs because they did not view them as having the expertise or time to respond to their self-harm. Findings also suggest participants held certain expectations of what would be appropriate support, with time-limited or pharmacological support described as superficial, and psychological interventions preferred.

In addition, the notion of candidacy emerged,34 in terms of the extent to which people identified conditions or symptoms as a legitimate reason for consulting. It was only when older adults identified their self-harm as requiring a legitimate need for support that they explored avenues of help. The authors’ findings argue that older adults face the double jeopardy of the stigma of self-harm and ageism.35

Implications for research and practice

Taking into account the frequent contact of older adults who self-harm with GPs, and GPs’ capacity to support this population, further research is needed to explore the feasibility of potential self-harm interventions for older adults in primary care.

NICE suggests multi-agency partnerships for self-harm management,26 therefore primary care may wish to work with other sectors (health, social, and third sector), to comprehensively support older adults who self-harm.

As mentioned previously, future research could explore the perspectives of GPs on older adults’ self-harm to see whether the present findings are reflected in GPs’ experiences

Primary care is a potential avenue for effective self-harm management in older adults, and GPs can manage and support older adults who self-harm. Box 3 provides a list of recommendations for GPs supporting older people who self-harm, based on the results from this study, in combination with NICE guidance.1,26 These recommendations are not intended as a comprehensive list. Rather, in combination with GP training, they may provide guidance to GPs supporting older adults who self-harm.

Box 3.

Recommendations to GPs working with older people who self-harm

|

GPs can help legitimise self-harm as a reason for consultation and support patients in a variety of ways, ensuring patients understand their condition is taken seriously and that the language used is one of affirmation and thoughtfulness. This may improve future help-seeking and healthcare access in older adults, and thus reduce repeated self-harm and suicidal risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank PPIE group members for their contribution to this manuscript. They would also like to thank all participants of the study.

Funding

M Isabela Troya is funded by a Keele University ACORN studentship. Additional funding has been granted to M Isabela Troya by Santander Bank and the Allan and Nesta Ferguson Charitable Trust (reference number: LPG/CXP/FERGUSON/006779–00018). Faraz Mughal is funded through a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in-practice fellowship (reference number: IPF–2017–11–002). Carolyn Chew-Graham is partly funded by West Midlands Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. Lisa Dikomitis was awarded a senior fellowship by the Higher Education Academy. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and final responsibility for publication submission. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Ethics Review Panel at Keele University (reference number: ERP1333).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Self-harm in over 8s: long-term management CG133. London: NICE; 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg133 (accessed 20 Sep 2019) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Social Care. Preventing suicide in England: third progress report on the cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-third-annual-report (accessed 20 Sep 2019)

- 3.Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, et al. Self-harm in a primary care cohort of older people: incidence, clinical management, and risk of suicide and other causes of death. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(11):905–912. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30348-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troya MI, Babatunde O, Polidano K, et al. Self-harm in older adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214(4):186–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czernin S, Vogel M, Flückiger M, et al. Cost of attempted suicide: a retrospective study of extent and associated factors. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13648. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troya MI, Dikomitis L, Babatunde OO, et al. Understanding self-harm in older adults: a qualitative study. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;12:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McManus S, Lubian K, Bennett C, et al. Suicide and self-harm in Britain — researching risk and resilience using UK surveys. 2019. http://www.natcen.ac.uk/media/1704167/Suicide-and-self-harm-in-Britain-Main-report.pdf (accessed 20 Sep 2019)

- 8.Abendstern M, Hughes J, Jasper R, et al. Care co-ordination for older people in the third sector: scoping the evidence. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(3):314–329. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th edn. London: Sage Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason J. Researching your own practice: the discipline of noticing. Abingdon: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saldaña J. Longitudinal qualitative research: analyzing change through time. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denzin NK. Triangulation 2.0. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6(2):80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Troya MI, Chew-Graham CA, Babatunde O, et al. Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement in a doctoral research project exploring self-harm in older adults. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):617–631. doi: 10.1111/hex.12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owens C, Lambert H, Donovan J, Lloyd KR. A qualitative study of help seeking and primary care consultation prior to suicide. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(516):503–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandler A, King C, Burton C, Platt S. General practitioners’ accounts of patients who have self-harmed. Crisis. 2016;37(1):42–50. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox F, Stallard P, Cooney G. GPs role identifying young people who self-harm: a mixed methods study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):415–419. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimholt TK, Haavet OR, Jacobsen D, et al. Perceived competence and attitudes towards patients with suicidal behaviour: a survey of general practitioners, psychiatrists and internists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:208. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michail M, Tait L. Exploring general practitioners’ views and experiences on suicide risk assessment and management of young people in primary care: a qualitative study in the UK. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009654. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ, Hetler J, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: a training priority for primary care providers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(3):250–261. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saini P, Chantler K, Kapur N. General practitioners’ perspectives on primary care consultations for suicidal patients. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;24(3):260–269. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wand AP, Peisah C, Draper B, Brodaty H. How do general practitioners conceptualise self-harm in their older patients? A qualitative study. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018;47(3):146–151. doi: 10.31128/AFP-08-17-4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Preventing suicide in community and custodial settings NG105. London: NICE; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng105 (accessed 20 Sep 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor TL, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(2):104–110. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minichiello V, Browne J, Kendig H. Perceptions and consequences of ageism: views of older people. Ageing Soc. 2000;20(3):253–278. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyons A, Alba B, Heywood W, et al. Experiences of ageism and the mental health of older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2017;22(11):1456–1464. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1364347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmore E. Ageism comes of age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(6):873–875. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, et al. A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: description of the research domain. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(10):1573–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene JY, Weinberger M, Mamlin JJ. Patient attitudes toward health care: expectations of primary care in a clinic setting. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1980;14A(2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bodner E, Palgi Y, Wyman MF. Ageism in mental health assessment and treatment of older adults. In: Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C, editors. Contemporary perspectives on ageism. New York, NY: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]