Abstract

In the globalized and rapidly evolving work environment, deficiencies in job design are a common reason that employees must sometimes complete tasks that are not directly connected to their occupational role. Individuals with a clear vision of their occupational role and duties in particular, such as psychologists, might consider such tasks as an offense to self. According to the “Stress-as-Offense-to-Self” (SOS) concept, so-called “illegitimate tasks” do not respect a person’s occupational identity—threatening the self through disrespect. We investigated perceived appreciation as an underlying mechanism mediating between illegitimate tasks and reduced job satisfaction after one year through three studies conducted in two European countries. Using data from 50 psychologists who graduated from a German university, Study 1 revealed that perceived appreciation explained the relationship between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction after one year. Studies 2 and 3 confirmed this finding using data from 67 and 183 Swiss employees working in fields of psychology. In particular, illegitimate tasks affected the perception of appreciation immediately and in the long term, which in turn affected the psychologists’ job satisfaction (contagion model). Our results illustrate the importance of perceived appreciation as a mechanism that mediates between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction of psychologists.

Keywords: Psychosocial stress, Job satisfaction, Interpersonal relations, Workplace health, Social stressors, Appreciation

Introduction

If we examine the factors that shape our daily experiences and behavior, it becomes clear that work is a crucial factor for many people. Besides maintaining and developing our skills and giving us structure, work fosters social contact and appreciation and is often an important part of an individual’s identity1, 2). In this paper, we focus on the role of perceived appreciation by attempting to shed light on its function in the relationship between task assignment and psychologists’ job satisfaction. Otto et al. reflect on the specific relevance of social interactions for psychologists who work mostly with people either individually (e.g., in therapy, coaching, or personnel selection) or as part of a group (e.g., in conflict mediation or team intervention). Hence, it can be assumed that psychologists in particular build the meaning of their work through social interactions with clients and patients3, 4). In this research, based on the “Stress-as-Offense-to-Self” (SOS) concept5, 6), we assume illegitimate tasks impair job satisfaction by lowering a person’s perceived appreciation in the workplace.

Maintaining a positive sense of self—enhancing or protecting it—is a strong motivator for most people. As such, people exert great effort to protect or enhance their self-worth5, 7, 8). It is plausible that threats to this sense of self-worth or self-esteem induce experiences of stress, and the SOS concept was developed based on this assumption. Self-esteem is comprised of one’s personal evaluation of the self (personal self-esteem) as well as the evaluation of others (social esteem). Thus, the behavior of others or the characteristics of a situation can shape a person’s self-esteem in addition to the individual’s self-evaluation5, 6). According to the SOS concept, in a positive sense, “appreciation implies recognition of one’s individuality, achievements, and qualities”5). It signals acceptance and esteem and thus responds to the need to belong9). Conversely, social esteem can be threatened by signals of a lack of appreciation by others (stress as disrespect)5). These signals are stressors that trigger individual strain responses (stress). Such signals of disrespect can be directly expressed through the social behavior of others, such as launching verbal attacks, providing rude and reckless feedback, undermining others’ success, belittling others, and other similar actions. However, there also exist rather indirect ways to express disrespect and a lack of appreciation, such as being responsible for stress-inducing work conditions or even by assigning so-called illegitimate tasks.

Over the last decade, Semmer et al.5, 6, 10) have introduced illegitimate tasks as a new concept of stressors. These tasks violate norms about what one can legitimately expect from a person in a certain occupational role. Just imagine about working as a clinical psychologist with an additional therapeutic qualification and then being only allowed to distribute and analyze standardized questionnaires that patients complete. Or imagine spending an entire day completing health insurance forms as if they were a typist. Assigning such illegitimate tasks is an indirect way of expressing disrespect or a lack of appreciation.

People belong to social groups and fulfill social roles, such as an occupational role5). In line with Roberts and Donahue11), social contexts, such as roles, prescribe and facilitate behaviors through norms and scripted relationships. Moreover, social roles that include behavioral expectations often become part of the incumbents’ identity12, 13). Semmer et al.5, 6, 10) argue that by violating these occupational roles, illegitimate tasks disrespect a person’s occupational identity and therefore constitute an offense to the self. As illustrated in the examples above, the perceived illegitimacy does not result from performing immoral or illegal acts, which should commonly be avoided by all, but rather from the tasks being perceived as unreasonable or unnecessary. Unreasonable tasks should be done by someone else, because they do not correspond to the person’s occupational role, as seen in the case of the psychotherapist mentioned above who feels like a “typist”. Unreasonable tasks may also include tasks that do not correspond to a person’s skill set or competence level, such as the psychotherapist who is only allowed to disseminate and analyze standardized questionnaires.

An unnecessary task is one that could have been (at least partly) avoided or that does not make any sense to complete at all. Thus, unnecessary tasks are those tasks that are perceived to be a waste of time6), such as having to record things that are never read and never need to be read. Of course, there are cases in which unnecessary and unreasonable tasks might overlap. In the example of the psychotherapist feeling like a typist, he or she might find it unreasonable to invest his/her time in record-keeping instead of taking care of his/her clients. In addition, he/she also might perceive at least some of these records to be unnecessary. In summary, illegitimate tasks are those that include a threat to one’s occupational role as defined by aspects such as status and/or by the occupation itself.

Previous research has found illegitimate tasks to be associated with adverse outcomes on different levels, including behavioral outcomes (e.g., counterproductive work behavior, controlling for effort-reward imbalance, organizational justice, conscientiousness and agreeableness14)), physiological outcomes (e.g., increased cortisol while controlling for social stressors, work interruptions, and emotional stability15)), psychosomatic outcomes (e.g., decreased sleep quality, controlling for time pressure, social stressors (at work and at home) and state negative affect16)) indicators of stress reactions as well as indicators of impaired subjective well-being6, 17,18,19) (over and above other stressors, e.g., role conflict, social stressors, lack of fairness6)), and recovery (detachment20)).

Illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction

One of the most frequently studied outcomes of job stressors is job satisfaction21,22,23). Job satisfaction has been seen as a component of psychological well-being24) that relates to the extent to which a person likes or dislikes his or her job25). Job satisfaction contains a number of distinct facets26). In general, low job satisfaction has been found to be associated with deleterious effects on physical and mental health22), and decreased job satisfaction was found to predict psychologists’ intent to change careers26). Prior research confirmed the link between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction, and more specifically, illegitimate tasks were found to be associated with lower satisfaction with work performance in a sample of Swedish local government operations managers17). Another study analyzing the impact of perceived appreciation at work among military professionals found a negative impact of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction19). Apart from these studies, which used cross-sectional designs, Eatough et al.18) demonstrated the effects of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction in both a Swiss and a U.S. diary study that included participants from a wide variety of professions (e.g., staff of a local university, a local Fortune 500 company, or a hospital). However, all of these studies focused on a short or relatively short period of time.

The question of time, however27,28,29), i.e., how long it takes for (social) stressors to reveal their negative influence on (occupational) well-being, remains unanswered. To obtain a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms, a longer time frame must be examined. Ford and colleagues30) found lagged effects on psychological strain by mean time lag of one year. However, the question of time refers to a complex interplay between type of stressor, type of well-being, and confounding processes. Job satisfaction appears to be rather stable when measured across longer time periods21, 28, 31). Sonnentag and Frese29) summarized 73 studies examining the interplay between stressors and well-being. The authors found that the percentage of significant relationships between stressor and well-being tend to decrease with time lags longer than one year. Based on previous findings, in our attempt to find an answer to the time frame question we expect illegitimate tasks to be related to reduced job satisfaction in psychologists after one year (Hypothesis 1).

Illegitimate tasks and appreciation

As mentioned above, the SOS concept assumes the assignment of illegitimate tasks to be an indirect way of expressing a lack of respect and appreciation. Being appreciated refers to an evaluation by others i.e., the person assigning these tasks, which contributes to social esteem5, 19). Expressing appreciation shows an interest in the person and his or her concerns5, 32). Accordingly, a lack of appreciation is more than not praising somebody: Feedback and social support may, but do not have to express appreciation5). Tasks that are perceived to be unreasonable or unnecessary should not be expected to be completed by the individual based on the task’s content, as this person has certain roles, achievements, and qualities. Ultimately, expressing a lack of appreciation is not necessarily tied to a social interaction nor does it have to be intentional, but assigning illegitimate tasks reflects a lack of consideration for the interests of the person the task is assigned to5, 6). Thus, we expect illegitimate tasks to be related to perceived reduced appreciation (Hypothesis 2) both immediately (H2a) as well as in the long term (H2b).

Appreciation and job satisfaction

Appreciation is regarded as a powerful resource provided by others5, 19). In general, job resources are known to contribute to well-being29). Specifically, perceived appreciation involves being noticed and acknowledged as a valued individual5, 32) boosting self-esteem and therefore leading to well-being5, 19). Moreover, appreciation plays a role in motivational processes, thus increasing job satisfaction33, 34). In addition, appreciation is an important tool to establish good leadership33). In line with this consideration, Stocker et al.19) found perceived appreciation to be positively correlated to job satisfaction. Previous research conducted with young workers just starting their job found that high levels of perceived appreciation over the course of four years enhanced employees’ job satisfaction35, 36). We hypothesized perceived appreciation to be positively related to job satisfaction (Hypothesis 3) both immediately (H3a) and in the long term (H3b).

Appreciation as a mechanism linking illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction

According to the SOS concept, the proposed mechanism by which illegitimate tasks reduce job satisfaction is a lack of respect or appreciation leading to an offense to the social self5, 6, 10). While Stocker et al.19) cross-sectionally found perceived appreciation to mediate the relationship between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction, results of cross-sectional studies do allow for many alternative explanations for the observed effects, as reverse causation cannot be precluded37). To rule out possible alternative explanations regarding the timeline, we tested the impact of perceived appreciation (immediately and after one year) on the association between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction after one year. We expect perceived appreciation to mediate the relationship between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction after one year (Hypothesis 4), both immediately (H4a) and in the long term (H4b).

Illegitimacy and psychologists’ job satisfaction

We assume that the effect of illegitimate tasks on perceived appreciation and the effect of perceived appreciation on job satisfaction are especially strong for people working in social jobs, like psychologists. Most German psychologists work in clinical psychology, with the second-largest group working in the field of work and organizational psychology38). Their core activities are mainly executed in social contexts, i.e., working with people as individuals and as group members, whether in a therapy setting or in relation to human resource management. As part of a qualitative study, Sobiraj et al.39) asked psychologists according to which criteria they would consider themselves successful in their profession. Contrasting prior career research focusing on salary, positions, or career satisfaction, receiving appreciation (from patients or superiors, etc.) was reported as the most important point by far. Thus, they should be more sensitive to meanings of social behavior, like a lack of appreciation. In addition, as psychologists’ everyday work is characterized by interpersonal interactions, for these individuals such relationships at work should be more important than for those in non-social jobs. Therefore, the perception of a lack of appreciation by others should have a strong impact on the job satisfaction of psychologists. Hence, the indirect effect of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction through perceived appreciation should be especially strong for psychologists.

The role of time in the illegitimate tasks/job satisfaction relationship

Beyond testing for a generally mediating effect of perceived appreciation in the illegitimate tasks/job satisfaction relationship, we want to explore this process in more detail, as this knowledge can help to identify for protecting factors. We expect illegitimacy of task assignment to be immediately related to perceived appreciation. If this perceived lack of appreciation resulting from the assignment of illegitimate tasks is related to long-lasting consequences for job satisfaction (i.e., a widely used outcome in organizations known to be related to behavioral and health-related outcomes22)), then protecting factors should draw on task assignment and communication early on in this process. However, if the assignment of illegitimate tasks shapes the perception of future appreciation, then protecting factors, such as post-incident social support, might also prevent dissatisfaction resulting from illegitimate tasks.

Ultimately, there are three different pathways that could be imagined for explaining the underlying mechanism of appreciation. First, illegitimate tasks could have immediate consequences for an individual’s perceived appreciation, leading to impaired job satisfaction after one year (immediate-release model). Second, illegitimate tasks could also have immediate consequences for perceived appreciation that could also impact perceived appreciation one year later, shaping job satisfaction at that time (contagion model). Third and finally, illegitimate tasks could have long-term consequences for perceived appreciation after one year, and begin shaping job satisfaction at that point (delayed-release model).

Methods

We investigated the research questions in three independent samples. Study 1 investigated associations between illegitimate tasks and psychologists’ job satisfaction one year later. Data were collected through an online psychology graduate survey distributed at a German university. Studies 2 and 3 also investigated associations between illegitimate tasks and psychologists’ job satisfaction (one year later) and incorporated two variations: the participants in these studies were comparably older and came from a different cultural context.

Procedure and sample

Study 1

Data from 52 psychologists who had participated in both the initial survey (t1) and the follow-up survey with a time lag of one year (t2) could be matched. Taking into consideration that on average, 60 psychologists graduated each year from the university at which the survey was conducted, the return rate (using cohorts of alumni over a time frame of six years) seems to reasonably account for the fact that not all graduates maintained their old e-mail accounts.

Data from two participants were excluded because they were currently unemployed. The resulting sample thus consisted of 50 participants (Table 1), 80% of whom were female. Their ages varied between 24 and 40 yr, and the mean age was 30.2 yr (SD=4.24). Except for two participants, all the respondents worked as a psychologists. Among these, 29% worked in the specialization area of clinical psychology, 25% worked as researchers, 21% worked in the area of educational psychology, 6% worked in the sector of work and organizational psychology, and another 6% practiced in forensic psychology at the beginning of the study. Professional tenure ranged from 1.83 to 11.25 yr, and average tenure was 4.86 yr (SD=2.10).

Table 1. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), scale ranges, and zero-order correlations of all study variables.

| M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sexa | 0–1 | - | |||||||

| 2 | Age (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 30.18 | 4.24 | 24–40 | –0.25 (–0.55, 0.08) | - | |||||

| Study 2 | 49.72 | 11.86 | 31–80 | –0.10 (–0.16, 0.35) | - | |||||

| Study 3 | 45.66 | 9.88 | 22–64 | –0.09 (–0.23, 0.05) | - | |||||

| 3 | Job satisfaction (t1) (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 4.28 | 0.96 | 1–6 | –0.28 (–0.47, –0.09) | 0.28 (0.00, 0.54) | - | ||||

| Study 2 | 5.90 | 1.03 | 1–7 | –0.01 (–0.24, 0.23) | 0.08 (–0.16, 0.31) | - | ||||

| Study 3 | 5.33 | 1.11 | 1–7 | –0.14 (–0.24, –0.03) | 0.12 (–0.02, 0.25) | - | ||||

| 4 | Job satisfaction (t2) (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 4.53 | 0.75 | 1–6 | –0.09 (–0.36, 0.20) | 0.23 (–0.02, 0.46) | 0.52 (0.28, 0.69) | - | |||

| Study 2 | 5.75 | 1.22 | 1–7 | 0.04 (–0.32, 0.27) | 0.17 (–0.05, 0.37) | 0.59 (0.40, 0.75) | - | |||

| Study 3 | 5.57 | 0.89 | 1–7 | –0.07 (–0.20, 0.06) | 0.04 (–0.11, 0.19) | 0.42 (0.26, 0.57) | - | |||

| 5 | Appreciation (t1) (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 4.74 | 0.71 | 1–6 | –0.27 (–0.50, 0.01) | 0.27 (–0.03, 0.51) | 0.38 (0.10, 0.60) | 0.44 (0.17, 0.66) | - | ||

| Study 2 | 6.02 | 1.13 | 1–7 | –0.08 (–0.14, 0.27) | –0.03 (–0.24, 0.17) | 0.48 (0.22, 0.70) | 0.31 (0.12, 0.49) | - | ||

| Study 3 | 5.79 | 1.02 | 1–7 | –0.13 (–0.25, –0.01) | 0.03 (–0.13, 0.18) | 0.60 (0.48, 0.71) | 0.36 (0.23, 0.50) | - | ||

| 6 | Appreciation (t2) (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 4.63 | 0.75 | 1–6 | –0.13 (–0.42, 0.18) | 0.28 (0.03, 0.51) | 0.25 (–0.04, 0.48) | 0.58 (0.32, 0.75) | 0.62 (0.39, 0.79) | - | |

| Study 2 | 5.88 | 1.02 | 1–7 | –0.08 (–0.15, 0.28) | 0.06 (–0.21, 0.31) | 0.43 (0.21, 0.63) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.74) | 0.49 (0.30, 0.66) | - | |

| Study 3 | 5.79 | 1.02 | 1–7 | –0.03 (–0.18, 0.12) | –0.01 (–0.16, 0.14) | 0.27 (0.11, 0.42) | 0.56 (0.42, 0.69) | 0.53 (0.41, 0.64) | - | |

| 7 | Illegitimate tasks (t1) (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Study 1 | 2.06 | 0.62 | 1–5 | 0.09 (–0.24, 0.40) | –0.35 (–0.58, –0.10) | –0.24 (–0.46, –0.02) | –0.46 (–0.64, –0.19) | –0.35 (–0.56, –0.13) | –0.47 (–0.66, –0.22) | |

| Study 2 | 2.49 | 1.12 | 1–7 | –0.08 (–0.15, –0.30) | –0.02 (–0.27, 0.23) | –0.58 (–0.74, –0.37) | –0.49 (–0.67, –0.26) | –0.59 (–0.76, –0.36) | –0.42 (–0.62, –0.16) | |

| Study 3 | 2.52 | 0.73 | 1–5 | –0.06 (–0.21, 0.08) | –0.10 (–0.26, 0.06) | –0.55 (–0.64, –0.45) | –0.32 (–0.44, –0.19) | –0.45 (–0.55, –0.33) | –0.21 (–0.35, –0.07) | |

Pearson correlation coefficients. 95%CI bootstrapped confidence intervals, bootstrap sample size=10,000. a0: male, 1: female.

Ethics. The university did not require institutional review board approval of the study (an online psychology graduate survey) based on its nature and university standards. Our study was performed in agreement with all requirements defined by the German Society of Psychology, including giving participants information about their rights and guaranteeing anonymity. The participation of each employee in our questionnaire study was voluntarily. Nevertheless, a written informed consent form was not obtained explicitly from participants due to the online assessment technique employed, as this approach would have endangered participant’s anonymity.

Study 2

Data were based on a subsample of a population-based survey of health and the prevalence of back pain in Switzerland (N=16,674, sampling procedure and flow of participants was described previously40)). Altogether, 2,507 employees (of the 2,860 employees who were sampled from pre-stratified groups) reported a baseline for illegitimate tasks, appreciation, and job satisfaction. For this study, we investigated data from participants employed in typical psychology fields (social professions).

Out of the 2,507 returned questionnaires, 85 participants were employed in the field of psychology (e.g., teaching at a university, organizational consulting, or working as a psychotherapist). Data from 83 participants could be matched with data from those who had participated both in the baseline (t1) and the follow-up of this study with a time lag of one year (t2). Data from 16 participants were excluded due to missing data. The resulting sample consisted of 67 participants (Table 1), 69% of whom were female. Participants age varied between 31 and 80 yr, and the mean age was 49.7 yr (SD=11.86). Twenty-six of the participants were employed full time and 40 of these participants were employed part time.

Ethics. This study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee. The participation of each employee in our questionnaire study was voluntary.

Study 3

Regarding the third study, participants were representative of the Swiss working population in terms of sex, age, education, and industry (N=3,062, sampling procedure and flow of participants was described previously41)). For this study, we investigated data from participants employed in typical psychology fields (social professions).

Out of the 2,535 returned questionnaires, 183 participants were employed in the field of psychology and could be matched to both the baseline (t1) and the follow-up of the study with a time lag of one year (t2; Table 1). Among these respondents, 73% were female. Their age varied between 22 and 64 yr, and the mean age was 45.66 yr (SD=9.88).

Ethics. The university did not require institutional review board approval of the study based on its nature and university standards. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the code of the Swiss Association of Psychology.

Measures

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations and scale ranges for the study variables for each of the three studies.

Study 1

Illegitimate tasks. Illegitimate tasks were assessed using the Bern Illegitimate Tasks Scale (BITS)14). The BITS consists of eight items (e.g., “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which you believe should be done by someone else?” or “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which keep you wondering if they make sense at all?”). Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very rarely/never) to 5 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Appreciation. Perceived appreciation was measured using four items. Two of them refer to the scale of esteem reward developed by Siegrist et al.42) (ERI-K; “I receive the respect I deserve from my…” i) “superiors,” ii) “colleagues”). In addition, we added items for iii) “clients” and iv) “family and friends” as sources of appreciation. All items were answered on a 6-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The mean inter-item correlations were 0.31 (t1) and 0.33 (t2), respectively. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.64 for t1 and 0.66 for t2.

Job satisfaction. Job satisfaction was measured using six (out of seven, due to item-total correlation) items from Neuberger and Allerbeck’s43) Job Description Form developed based on the Job Descriptive Index44). This instrument refers to an employee’s satisfaction with various facets of their work (satisfaction with the job, working conditions, relationships, promotion opportunities, organization and management, as well as benefits and payment). A sample item is “All in all, I am satisfied with my working conditions”. The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.78 at t1 and 0.73 at t2.

Construct validity. We tested the construct validity of our measures with confirmatory factor analyses using AMOS 24. First, a three-factor model (illegitimate tasks, appreciation, job satisfaction at the first measurement point) with all items loading on their respective factors was tested (χ2=274.65, df=132, p<0.01, AIC=388.65). Next, a one-factor model with all items loading on a general factor (χ2=364.30, df=132, p<0.01, AIC=454.39) was tested. Between both models, the three-factor model fit the data better than the alternative model and was preferred45). Furthermore, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to assess whether common method variance exists. We calculated a CFA with all study variables (including both measurement points) loading on a single latent factor. Results suggest that common method variance can be neglected in further analyses (R2=0.05)46).

Studies 2 and 3

Illegitimate tasks. In Studies 2 and 3, illegitimate tasks were assessed using two items from BITS14). One item was used with respect to unreasonable tasks (“Do you have work tasks to take care of, which you believe are going too far, and should not be expected from you?”) and one item was used for unnecessary tasks (“Do you have work tasks to take care of, which keep you wondering if they have to be done at all?”). In Study 2, participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Both items correlated to 0.56 (p<0.01). In Study 3, both items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Items correlated to 0.49 (p<0.01).

Appreciation. In Study 2, perceived appreciation was measured by a single-item measure (“When you consider the situation at work in general, how much would you agree with the following statement: My effort is appreciated.”). The item was answered on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In Study 3, we measured appreciation using a single item47) (“In general, I feel appreciated at work.”; 1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree).

Job satisfaction. In Studies 2 and 3, job satisfaction was measured by a single-item measure of global job satisfaction (“Overall, how satisfied are you with your work?”). The response scale ranged from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied). Single-item measures of global job satisfaction are as reliable and valid as measures containing different facets48).

Data analysis

The analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software package, version 2349). First, we calculated mean, standard deviation and zero-order correlations. Second, to test hypotheses one to three we conducted hierarchical regression analyses including variables in two different blocks: In step one, control variables (including sex, age, and job satisfaction at t1) were considered, and in step two the respective variables were entered. Finally, to test the longitudinal mediation, we used Hayes’ bootstrap test for estimation of indirect effects (PROCESS macro for SPSS)50), controlling for sex, age, and the outcome variable and job satisfaction at tl. As a consequence, the dependent variable represented the deviation of job satisfaction at t2 from the value that was expected based on job satisfaction at t1. The number of bootstrapped samples was 5,000.

Results

Study 1

In line with Hypotheses 1 and 2 (Table 2), illegitimate tasks were negatively associated with job satisfaction and perceived appreciation (immediately and after one year). In addition, perceived appreciation was positively associated with job satisfaction (immediately and after one year), confirming Hypothesis 3.

Table 2. Summary of multiple regression analysis predicting job satisfaction and appreciation (Study 1).

| Variable | Job satisfaction | Appreciation t1 | Appreciation t2 | Job satisfaction | Job satisfaction | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | |

| Step 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.14 | 0.31 | −0.44, 0.80 | −0.4 | 0.28 | −0.91, 0.20 | 0 | 0.35 | −0.65, 0.71 | 0.14 | 0.31 | −0.44, 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.31 | −0.33, 0.68 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04, 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03, 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01, 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04, 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03, 0.07 |

| Job satisfaction t1 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.10, 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.67 | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Illegitimate tasks | −0.44 | 0.15 | −0.73, −015 | −0.37 | 0.18 | −0.73, −0.01 | −0.51 | 0.21 | −0.95, −0.10 | ||||||

| Appreciation t1 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.06, 0.59 | ||||||||||||

| Appreciation t2 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.22, 0.72 | ||||||||||||

| R2 step 1 (Adj R2) | 0.28 (0.23)** | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.23)** | 0.28 (0.23)** | ||||||||||

| R2 step 2 (Adj R2) | 0.39 (0.33)** | 0.19 (0.13)* | 0.23 (0.18)* | 0.35 (0.29)** | 0.50 (0.44)** | ||||||||||

| ∆R2 | 0.12* | 0.09* | 0.15** | 0.08* | 0.22** | ||||||||||

N≤50. B: unstandardized regression coefficient; SEB: standard error; t: t-value; 95%CI bootstrapped confidence intervals: bootstrap sample size=5,000. a0: male, 1: female. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (two-tailed). t1/t2: first/second time of survey.

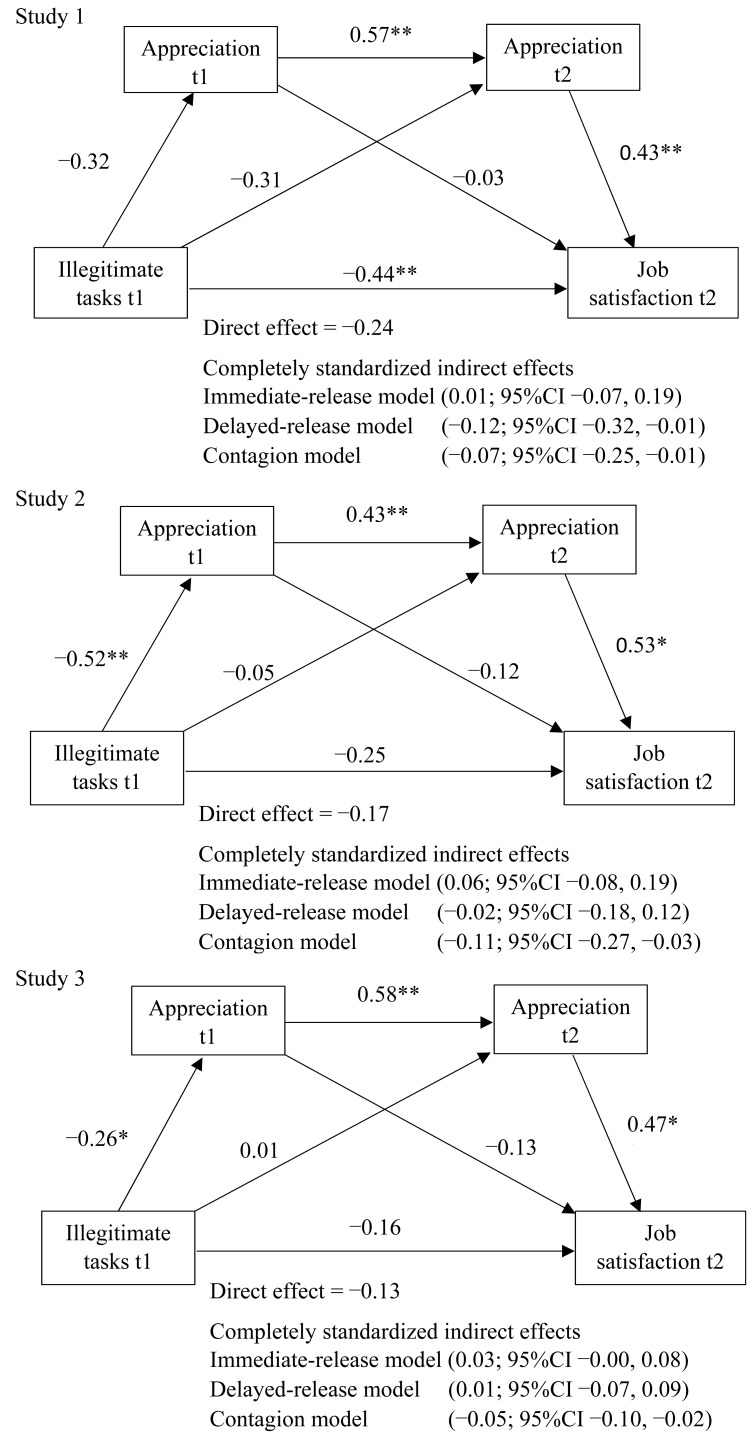

The mediation is displayed in Fig. 1. There is evidence of a negative indirect effect of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction one year later, confirming our fourth hypothesis. A distinction between three indirect paths can be made. Path 1: illegitimate tasks t1, perceived appreciation t1, and job satisfaction t2 one year later (immediate-release model); path 2: illegitimate tasks t1, perceived appreciation t1, perceived appreciation t2, and job satisfaction t2 one year later (contagion model); path 3: illegitimate tasks t1, perceived appreciation t2, and job satisfaction t2 one year later (delayed-release model). The results for the different paths are also presented in Fig. 1. The immediate-release path was not significant, whereas the delayed-release and contagion paths were.

Fig. 1.

Double mediation of appreciation between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 (two-tailed). Bootstrapp sample size=5,000. t1/t2: first/second time of survey.

Studies 2 and 3

Results of regression analyses regarding Study 2 are shown in Table 3 and those relating to Study 3 are shown in Table 4. Across both studies, illegitimate tasks were negatively associated with job satisfaction, although this effect marginally failed to reach significance (H1). Regarding Hypotheses 2, illegitimate tasks were negatively correlated with perceived appreciation (immediately and one year later). In Study 2, perceived appreciation was positively associated with job satisfaction in the long-term (H3b) but not immediately (H3a), partially confirming Hypothesis 3 (Table 3). Similar to the first study, in Study 3 perceived appreciation was positively associated with job satisfaction (immediately and after one year), confirming Hypothesis 3.

Table 3. Summary of multiple regression analysis predicting job satisfaction and appreciation (Study 2).

| Variable | Job satisfaction | Appreciation t1 | Appreciation t2 | Job satisfaction | Job satisfaction | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | |

| Step 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Sexa | −0.16 | 0.26 | −0.69, 0.37 | 0.2 | 0.3 | −0.41, 0.80 | 0.17 | 0.28 | −0.50, 0.72 | −0.19 | 0.25 | −0.69, 0.32 | −0.23 | 0.26 | −0.75, 0.30 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 |

| Job satisfaction t1 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.45, 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.38, 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.12 | 0.42, 0.89 | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Illegitimate tasks | −0.25 | 0.13 | −0.51, 0.01 | −0.61 | 0.1 | −0.82, −0.41 | −0.39 | 0.11 | −0.80, −0.38 | ||||||

| Appreciation t1 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.17, 0.32 | ||||||||||||

| Appreciation t2 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.23, 0.70 | ||||||||||||

| R2 step 1 (Adj R2) | 0.37 (0.34)** | 0.01 (−0.02) | 0.01 (−0.02) | 0.34 (0.31)** | 0.36 (0.33)** | ||||||||||

| R2 step 2 (Adj R2) | 0.40 (0.36)** | 0.37 (0.34)** | 0.19 (0.15)** | 0.35 (0.30)** | 0.49 (0.45)** | ||||||||||

| ∆R2 | 0.03† | 0.36** | 0.18** | 0 | 0.13** | ||||||||||

N=67. B: unstandardized regression coefficient; SEB: standard error; t: t-value, 95%CI bootstrapped confidence intervals: bootstrap sample size=5,000. a0: male 1: female. †p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (two-tailed). t1/t2: first/second time of survey.

Table 4. Summary of multiple regression analysis predicting job satisfaction and appreciation (Study 3).

| Variable | Job satisfaction | Appreciation t1 | Appreciation t2 | Job satisfaction | Job satisfaction | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | B | SEB | 95%CI | |

| Step 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Sexa | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.27, 0.21 | −0.29 | 0.17 | −0.58, −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.17 | −0.39, 0.30 | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.30, 0.24 | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.26, 0.20 |

| Age | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.02 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 |

| Job satisfaction t1 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.17, 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.23, 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.18, 0.52 | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Illegitimate tasks | −0.16 | 0.1 | −0.35, −0.01 | −0.64 | 0.09 | −0.84, −0.46 | −0.31 | 0.12 | −0.55, −0.09 | ||||||

| Appreciation t1 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.01, 0.30 | ||||||||||||

| Appreciation t2 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.27, 0.61 | ||||||||||||

| R2 step 1 (Adj R2) | 0.17 (0.16)** | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.00 (−0.01) | 0.17 (0.16)** | 0.17 (0.16)** | ||||||||||

| R2 step 2 (Adj R2) | 0.19 (0.17)** | 0.23 (0.21)** | 0.05 (0.03)* | 0.19 (0.18)** | 0.39 (0.38)** | ||||||||||

| ∆R2 | 0.01† | 0.21** | 0.05** | 0.02* | 0.22** | ||||||||||

N=183. B: unstandardized regression coefficient; SEB: standard error; t: t-value; 95%CI bootstrapped confidence intervals: bootstrap sample size=5,000. a0: male, 1: female. †p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (two-tailed). t1/t2: first/second time of survey.

Despite the lack of the initial relationship between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction (controlling for the autoregressor), the mediation analyses was conducted to allow potential suppressor influences of control variables on postulated mediation. The mediation and results for the different paths are displayed in Fig. 1. Again, in both Studies 2 and 3, there is evidence of a negative indirect effect of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction after one year, confirming our fourth hypothesis. In both studies, the immediate-release and the delayed-release paths were not significant, while the contagion path was significant.

General Discussion

This study explored the link between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction by considering perceived appreciation as the underlying mechanism. This paper addresses illegitimate tasks as a specific, task-related stressor that is assumed to lead to stress because such tasks do not align with a person’s occupational role6). As proposed by the SOS concept, we therefore hypothesized illegitimate tasks to damage job satisfaction by lowering a person’s perceived appreciation.

While boosting one’s role identity (e.g., by being successful in a task) is an important source of pride and satisfaction, in line with the concept of SOS, threats to one’s role identity are likely to induce stress51,52,53). It can be argued that not only social interactions, but also task assignment include a social message about the respect paid to the individual. Illegitimate tasks act as work stressors because they constitute a threat to the social self.

Across three studies, we found illegitimate tasks to be negatively associated to job satisfaction after one year, although in Study 2 and 3 the effect marginally failed to reach significance (Hypothesis 1). In addition, in all three studies the relationship between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction appears to be mediated by the appreciation perceived by the person (Hypothesis 4). In Studies 1 and 3, illegitimate tasks were negatively associated with perceived appreciation and perceived appreciation was positively associated with job satisfaction at both measurement points, confirming Hypothesis 2 and 3. Regarding Hypothesis 3, in the second study, only perceived appreciation one year later, not immediately, was positively associated with job satisfaction (H3b, but not H3a).

According to Study 1, mediation was found for two of the three possible indirect paths. Our pattern of results confirms both the delayed-release as well as the contagion models. Specifically, illegitimate tasks directly affected the perception of appreciation after one year as well as indirectly through the immediate perception of appreciation. The perception of appreciation one year later in turn affected job satisfaction at that time. Results do not support the immediate-release model. Perceived appreciation at the first measurement point did not mediate job satisfaction one year on. This is logical, since felt appreciation might have a more immediate effect rather than long-lasting benefits. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies to date that have tested this. Considering the example of being praised by one’s boss for a job well done, this praise might have a beneficial effect on how a person feels in the moment but it is doubtful whether the individual will remember this particular episode one year later and still benefit from it.

On the contrary, illegitimate tasks were shown to have long-lasting effects on job satisfaction one year later as well as on felt appreciation both immediately and after one year. This can be explained by the fact that “bad things” carry more weight than “good things”54, 55). A person is immediately offended by the lack of appreciation perceived as communicated by the assignment of illegitimate tasks. Although this initial offense fades over time, it might affect the perception of long-term appreciation (e.g., a person might become suspicious of how he/she is perceived by others because he or she is the one who must always do things that nobody else is willing to do), shaping job satisfaction after one year. The second and third study both confirmed this pattern with respect to the contagion but not the delayed-release model.

Disrespect refers to an interpersonal rejection undermining the basic need to belong to groups and to maintain good interpersonal relationships56). Conversely, receiving appreciation is very important with respect to well-being36). Appreciation relates to evaluation by others32) and is closely connected to self-esteem57, 58). It implies recognition of one’s individuality, achievements, and qualities, thereby boosting self-esteem. Appreciation signals acceptance and esteem, and thus responds to the need to belong9).

Focusing specifically on our sample of psychologists, there are several sources likely to provide appreciation that should be considered59). When working as a psychotherapist in a hospital, as a consultant in an organization, or as a research assistant at a university, psychologists might be a part of a (interdisciplinary) team, including colleagues or supervisors. Even when self-employed, psychologists have patients, clients, or interns who can be seen as “customers” who potentially provide support and appreciation. Both social support and appreciation satisfy the need to belong, but while social support is the perceived amount of support received from others, appreciation is an evaluation by others that when given, boosts self-esteem, which is important for well-being32). Instrumental social support (i.e., assistance with problem solving through tangible or informational support) is often valued as an inherent expression of appreciation60). Moreover, social support must convey appreciation—otherwise it might become a stressor61). In the same way, tasks convey an inherent social message of respect and appreciation. Our results illustrate the importance of this appreciation for the job satisfaction of psychologists. The results are in line with Stocker and colleagues19), who investigated the intervening role of perceived appreciation between illegitimate tasks and job satisfaction within the Swiss armed forces. The question arises as to what behavioral expectations are associated with being a psychologist. Psychologists in Germany and Switzerland are a highly qualified sample. More specifically, giving appreciation is supposed to be a central element of the occupational role of psychologists (not only for clinical psychotherapists). They are trained over a period of several years, both during their studies and afterwards, to take an appreciative attitude towards other individuals. A lack of appreciation in relation to one’s own work might therefore be particularly offensive. This lack of appreciation is, in this case, expressed by the way other people (supervisors, colleagues, clients, or customers) treat the person. This can be interpreted through personal questions such as: “Do I receive interesting and challenging tasks?” “Do they respect me, not only as a person, but also as an incumbent of my occupational role?” In addition, providing good justification for the necessity of tasks that might not directly correspond to an individual’s occupational role is essential. Helping employees to understand the situation can be key for giving a token of appreciation and thus countering declining job satisfaction.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, especially with respect to the first and second study, our sample size was rather small. Small sample sizes cause limited power and therefore an extended risk of missing a significant effect. Based on previous research, we expected moderately sized effects on the outcomes. Power analyses using G*Power62) indicated that a total sample size of 81 participants was required for an 80% chance of detecting a moderately sized indirect (double mediation) effect of f=0.15 with an alpha of 0.05. However, this method seems to be rather conservative, as we calculated mediation using Hayes’ bootstrap test for estimation of indirect effects. The causal step approach63), which has been very helpful in guiding researchers who study mediational models over many years64), has been heavily criticized recently65). One of the main points of criticism is the fact that this approach is among the lowest in power66). An alternative and well-recognized method to test for mediation is true bootstrapping65). Simulation research has shown that this method has the best Type I error control and has the highest power65).

Second, all measures were based on self-reports by participants for illegitimate tasks as well as for job satisfaction and perceived appreciation. This might increase the danger of overestimating results due to common method biases46, 67, 68). However, all of our concepts seem to be best assessed by self-reported data.

Third, all studies were conducted online. In particular, Study 1 focused on psychologists who graduated from university. The online approach allowed us easy access to graduates of the university, however, it prevented us from gathering a representative sample of psychologists. In addition, for Study 1 the sample might be biased if those psychologists who are satisfied with their career development and their working conditions participated in the study in higher numbers than those who are not.

Replication of findings is known to be very important. Three independent samples yielded results conforming to hypotheses, arguing against an explanation in terms of selection bias69,70,71). However, there are differences in these three studies with respect to measures, populations and context that also might account for differences in the results. Whereas the first study is based on psychologists who graduated from university, the second and third studies were based on a broader sample of Swiss employees working in fields of psychology. Replication in different contexts despite the use of slightly different measures underline the robustness of findings.

Moreover, in our second and third study we assessed central variables using single-item measures. Relying on single-item measures can be criticized for a lack of reliability in measurement. Single items can be appropriate when measuring constructs that might be one-dimensional and ask for an “overall” judgement, such as job satisfaction48), but might be different with respect to appreciation.

Finally, while the longitudinal design of this research eliminates several alternative explanations regarding the timeline, it does not allow for causal conclusions37). A recent intervention study72) found that an organizational-level workplace intervention focusing on core job tasks did not decrease the level of illegitimate tasks but rather protected against an increase in these tasks during a two yr follow-up period. Future studies might take into account an experimental setting on illegitimate tasks and well-being to prove causality by manipulating the perceived illegitimacy of tasks (e.g., by designing vignettes). However, manipulating the perceived illegitimacy of tasks might not be appropriate in every type of context. Moreover, these tasks are linked to the role identity of the given person, place, time, and situation5); a more precise view of the wide occupational range of working as a psychologist might be needed.

It should also be considered that we used a longitudinal design with a time lag of one year, and more knowledge might still be gained if longer time periods are taken into account. It should be noted that while Ford and colleagues30) found lagged effects on psychological strain by mean time lag of one year, which we chose as the lag between both times of assessment, the authors also demonstrated that the effects might increase up to a period of approximately three year. Hence, it might be interesting in our case to determine whether job satisfaction further declines after the one-year period following the assignment of illegitimate tasks, whether other reactions occur (such as an increase in turnover or intentions to leave the situation), or whether instead of behavioral reactions, a cognitive adaptation to the circumstances occurs, which could be reflected in higher resigned job satisfaction, for example27).

Theoretical implications

Demonstrating that illegitimate tasks are related to job satisfaction through threatened appreciation is only the beginning. Future studies should investigate this process in daily life in detail. Future work should also specify the assumption that a lack of appreciation is transformed into lower self-esteem5, 6).

Theoretical assumptions from the SOS concept and prior research suggest that the more elaborated (or narrow) a person’s occupational role is, the more likely the person will be able to perceive illegitimacy regarding the tasks or duties they are asked to fulfill36, 73). In this paper, we focused on a profession that has only been investigated in very few studies thus far and seems to be characterized by a quite comprehensive occupational image, i.e. psychologists37). At first glance, the psychology profession appears to be extremely diversified. According to the work context, serving as a therapist in a clinical setting, for example, suggests skill sets quite different from those applied by a change manager in a consulting company. There are, however, certain similarities across the various work settings of psychologists because the specific nature of the psychological profession is “to render professional services to clients, based on psychological principles, knowledge, models and methods which are applied in an ethical and scientific way”74).

Moreover, people studying psychology appear to have a very clear conception of their motives and thus their professional choice already (“working and helping people”; “to understand mental processes”)75). Accordingly, we assume that the occupational self-concept for these individuals is strongly developed, making them an ideal sample for studying illegitimate tasks. However, this argument must be proven by further research and future studies might account for differences within the field of psychology. In addition, cultural differences between our Swiss and German samples might be a plausible area of study.

The assumption of linking illegitimate tasks to a decrease in job satisfaction through the expression of a lack of appreciation is not bound to the psychological profession. Future research should address these hypotheses in additional samples that include various occupations (e.g., higher-skilled professionals and lower-skilled, non-professionals) and sectors.

Furthermore, it could be expected that being assigned illegitimate tasks decreases as an individual’s age increases. Interestingly, previous research did not find the perception of illegitimate tasks to correlate with age in any way6, 14). On the other hand, it is plausible that for younger employees, an occupational role concept must be developed first to be threatened by perceived illegitimacy of tasks. However, recent research indicates that the perception of illegitimate tasks is possible even during professional training—i.e., before entering the job76). In addition, it is also plausible that stressor-strain relationships (e.g., socio-emotional selectivity hypothesis77)) differ between younger and older people. Especially for older and more experienced employees, the perception of illegitimate tasks might be perceived as a lack of respect that threatens the self. Although the first study contained a rather young sample (M=30.18 yr), the second and third studies are based on comparably older samples (Study 2: M=49.72 yr; Study 3: M=45.66 yr). Our results suggest that the observed patterns is similar across all three samples. Future research should also consider age as a moderator in the stressor-strain relationship.

Practical implications

As mentioned above, giving appreciation appears to be a core element of the occupational role of psychologists. In general, increasing demands on the flexibility of employees also increases the risk of contracting authorities (supervisors or colleagues) having to assign tasks that are not directly connected to an employee’s core activities. Confirming our hypothesis, illegitimate task assignment is immediately related to perceived appreciation. Although this immediately perceived lack of appreciation is not directly related to long-lasting consequences for job satisfaction, it shapes the perception of future appreciation and thereby job satisfaction one year later. Thus, supervisors (even if they are not the only source of task assignment) should be trained to recognize such tasks as illegitimate at an early stage and, if it is necessary to allocate tasks perceived as illegitimate, how to communicate them in an appropriate way that explains their necessity to the person they are assigned to. In this way, illegitimate tasks might become legitimate to the person because they are perceived as necessary and reasonable.

The social meaning of task assignment seems to be the first step within the process of perceived appreciation. Yet, our results reveal delayed effects of illegitimate tasks on appreciation as well as contagion of a lack of appreciation shaping job satisfaction. This is important, as it opens up new opportunities for intervening factors later in this process. The initial lack of appreciation due to illegitimate tasks had no direct long-term effects on job satisfaction. Thus, one possible intervening factor is providing appreciation through other sources, such as adequate social support60). This would counteract the detrimental long-term effects of illegitimate tasks on appreciation and would therefore reduce the negative long-term effects of illegitimate tasks on job satisfaction. However, a chronic climate of illegitimate task assignment might impair the social climate in the long run.

Stress prevention is also part of a supervisor’s role and requires that supervisors not only possess (social) skills and sufficient resources (e.g., a reasonable span of control), but also have the necessary support from the organization and their own supervisors. Creating a culture that prevents stress and fostering well-being through appreciation starts from the top and is not achieved in the course of only a few days. Considering the question of stress as a threat to the self thus opens up new perspectives and approaches in the work context.

Conclusion

Psychologists have known that appreciation is a powerful instrument in social interactions for a long time. However, it is also important that experts in giving appreciation are appreciated themselves. Aspects of working conditions or even tasks that must be completed can appear in different lights based on their inherent social message. Behavior or assigned tasks that indicate disrespect or lack of appreciation as their social message constitute a threat to the person by offending the self and thus impair well-being.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in Study 2 was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation, National Research Program NRP53 “Health—Chronic Pain” entitled “Defining norm values on the natural history of acute and chronic low back pain in the Swiss population and prognostic indicators for chronic low back pain” (Project 405340-104826/1). The research reported in Study 3 was supported by the Swiss Health Promotion Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation (P2BEPI_158962).

References

- 1.Jahoda M .(1983) Wieviel Arbeit braucht der Mensch? Arbeit und Arbeitslosigkeit im 20 Jahrhundert [How much work does man need? Employment and unemployment in the 20th century]. Beltz, Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semmer NK, Meier LL .(2014) Bedeutung und Wirkung von Arbeit [Meaning and outcomes of work]. In: Lehrbuch Organisationspsychologie, Schuler H and Moser K (Eds.), 559–604, Huber, Bern. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otto K, Roe R, Sobiraj S, Baluku M, Garrido Vásquez ME. (2017) The impact of career ambition on psychologists’ extrinsic and intrinsic career success: the less they want, the more they get. Career Dev Int 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto K, Sobiraj S, Schladitz S, Garrido Vásquez ME, Roe R, Baluku M.Do social skills shape career success in the psychological profession? A mixed-method approach. Z Arb Organpsychol (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL, Elfering A .(2007) Occupational stress research: The ‘stress-as-offense-to-self’ perspective. In: Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice, Houdmont J and McIntyre S (Eds.), 43–60, ISMAI Publishing, Castelo da Maia. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL, Elfering A, Beehr TA, Kälin W, Tschan F. (2015) Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work Stress 29, 32–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leary MR, Baumeister RF. (2000) The nature and function of self-esteem: sociometer theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 32, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedikides C, Strube MJ .(1997) Self-evaluation: To thine own self to be good, to thine own self to be sure, to thine own self to be true, and to thine own self to be better. In: Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Zanna MP (Ed.), 209–69. Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leary MR. (1999) Making sense of self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 8, 32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL, Elfering A, Kälin W, Tschan F .(2013) Psychische Beanspruchung durch ilegitime Aufgaben [Strain resulting from illegitimate tasks]. In: Immer schneller, immer mehr: Psychische Belastungen und Gestaltungsperspektiven bei Wissens- und Dienstleistungsarbeit, Junghanns G and Morschhäuser M (Eds.), 97–112, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts BW, Donahue EM. (1994) One personality, multiple selves: integrating personality and social roles. J Pers 62, 199–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashforth BE, Kreiner GE. (1999) ‘How can you do it?’: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Acad Manage Rev 24, 413–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, Haslam C. (2009) Social identity, health and well being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Appl Psychol 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semmer NK, Tschan F, Meier LL, Facchin S, Jacobshagen N. (2010) Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behaviour. Appl Psychol 59, 70–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kottwitz MU, Meier LL, Jacobshagen N, Kälin W, Elfering A, Hennig J, Semmer NK. (2013) Illegitimate tasks associated with higher cortisol levels among male employees when subjective health is relatively low: an intra-individual analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 39, 310–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira D, Semmer NK, Elfering A. (2014) Illegitimate tasks and sleep quality: an ambulatory study. Stress Health 30, 209–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Björk L, Bejerot E, Jacobshagen N, Härenstam A. (2013) I shouldn’t have to do this: illegitimate tasks as a stressor in relation to organizational control and resource deficits. Work Stress 27, 262–77. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eatough EM, Meier LL, Igic I, Elfering A, Spector PE, Semmer NK. (2015) You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well being. J Organ Behav 37, 108–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stocker D, Jacobshagen N, Semmer NK, Annen H. (2010) Appreciation at work in the Swiss armed forces. Swiss J Psychol 69, 117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnentag S, Lischetzke T. (2018) Illegitimate tasks reach into afterwork hours: a multilevel study. J Occup Health Psychol 23, 248–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dormann C, Zapf D. (2001) Job satisfaction: a meta-analysis of stabilities. J Organ Behav 22, 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. (2005) The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 62, 105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin MA, Clarke S .(2011) Stress and well-being at work. In: APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Zedeck S (Ed.), 359–397, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. (2003) Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu Rev Psychol 54, 403–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector PE .(1997) Job satisfaction, Sage, Thousand Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carless SA, Bernath L. (2007) Antecedents of intent to change careers among psychologists. J Career Dev 33, 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frese M, Zapf D .(1988) Methodological issues in the study of work stress: objective vs. subjective measurement of work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In: Causes, coping, and consequences of stress at work, Cooper CL, Payne R (Eds.), 375–411, Wiley, Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roe RA. (2008) Time in applied psychology: the study of ‘what happens’ rather than ‘what is’. Eur Psychol 13, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonnentag S, Frese M .(2012) Stress in organization. In: Handbook of Psychology (Vol. 12: Industrial and Organizational Psychology), Schmitt NW, Highhouse S (Eds.), 560–92, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford MT, Matthews RA, Wooldridge JD, Mishra V, Kakar UM, Strahan SR. (2014) How do occupational stressor-strain effects vary with time? A review and meta-analysis of the relevance of time lags in longitudinal studies. Work Stress 28, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elfering A, Semmer NK, Kälin W. (2000) Stability and change in job satisfaction at the transition from vocational training into ‘real work’. Swiss J Psychol 59, 256–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N .(2003) Selbstwert und Wertschätzung als Themen der arbeitspsychologischen Stressforschung [Self-worth and appreciation as topics in work psychological stress research]. In: Innovative personal- und Organisationsentwicklung, Hamborg KC, Hollig H (Eds.), 131–55, Hogrefe, Göttingen. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stocker D, Jacobshagen N, Krings R, Pfister IB, Semmer NK. (2014) Appreciative leadership and employee well-being in everyday working life. Ger J Res Hum Resour Manage 28, 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzberg F .(1974) Work and the nature of man, Staples, London. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elfering A, Semmer N, Tschan F, Kälin W, Bucher A. (2007) First years in job: a three-wave analysis of work experiences. J Vocat Behav 70, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL. (2006) Arbeit und (mangelnde) Wertschätzung. Wirtschaftspsychologie 8, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zapf D, Dormann C, Frese M. (1996) Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: a review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. J Occup Health Psychol 1, 145–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margraf J. (2015) Zur Lage der Psychologie. Psychol Rundsch 66, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobiraj S, Schladitz S, Otto K. (2016) Defining and explaining career success in psychologists using person and job based resources. Psychol Educ J 53, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elfering A, Kottwitz MU, Tamcan Ö, Müller U, Mannion AF. (2018) Impaired sleep predicts onset of low back pain and burnout symptoms: evidence from a three-wave study. Psychol Health Med 23, 1196–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller AC, Igic I, Meier LL, Semmer NK, Schaubroeck JM, Brunner B, Elfering A. (2017) Testing job typologies and identifying at-risk subpopulations using factor mixture models. J Occup Health Psychol 22, 503–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, Godin I, Marmot M, Niedhammer I, Peter R. (2004) The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med 58, 1483–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neuberger O, Allerbeck M .(1978) Messung und Analyse von Arbeitszufriedenheit [Measurement and analysis of job satisfaction], Huber, Stuttgart. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith PC, Kendall LM, Hulin C .(1969) The measurement of satisfaction in work and behavior, Raud McNally, Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. (2003) Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88, 879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce JL, Gardner DG, Dunham RB, Cummings LL. (1989) Organizations-based self-esteem: construct definition, measurement, and validation. Acad Manage J 32, 622–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ. (1997) Overall job satisfaction: how good are single-item measures? J Appl Psychol 82, 247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corp IBM .Released (2013) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, IBM Corp, Armonk. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayes AF .(2013) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis, Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegrist J. (2000) Place, social exchange and health: proposed sociological framework. Soc Sci Med 51, 1283–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stets JE. (2005) Examining emotions in identity theory. Soc Psychol Q 68, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warr P .(2007) Work, happiness, and unhappiness. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. (2001) Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol 5, 323–70. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rozin P, Royzman EB. (2001) Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 5, 296–320. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117, 497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harter S .(1993) Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In: Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard, Baumeister RF (Ed.), 87–116, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leary MR. (2007) Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annu Rev Psychol 58, 317–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacobshagen N, Semmer NK. (2009) Wer schätzt eigentlich wen? Kunden als Quelle der Wertschätzung am Arbeitsplatz. Wirtschaftspsychologie 11, 11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Semmer NK, Elfering A, Jacobshagen N, Perrot T, Beehr TA, Boos N. (2008) The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. Int J Stress Manag 15, 235–51. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Semmer NK, Tschan F, Elfering A, Kälin W, Grebner S .(2005). Young adults entering the workforce in Switzerland: Working conditions and well-being. In: Contemporary Switzerland: Revisiting the special case, Kriesi H, Farago P, Kohli M, Zarin M (Eds.), 163–89, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41, 1149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baron RM, Kenny DA. (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51, 1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cole DA, Maxwell SE. (2003) Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol 112, 558–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayes AF. (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76, 408–20. [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. (2002) A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 7, 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semmer NK, Zapf D, Greif S. (1996) ‘Shared job strain’: a new approach for assessing the validity of job stress measurements. J Occup Organ Psychol 69, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spector PE. (2006) Method variance in organizational research: truth or urban legend? Organ Res Methods 9, 221–32. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cumming G, Williams J, Fidler F. (2004) Replication and researchers’ understanding of confidence intervals and standard error bars. Underst Stat 3, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moonesinghe R, Khoury MJ, Janssens ACJ. (2007) Most published research findings are false-but a little replication goes a long way. PLoS Med 4, e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer WD. (2001) Replication: a design principle for field research. Pract Assess, Res Eval 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Framke E, Sørensen OH, Pedersen J, Rugulies R. (2018) Can illegitimate job tasks be reduced by a participatory organizational-level workplace intervention? Results of a cluster randomized controlled trial in Danish pre-schools. Scand J Work Environ Health 44, 219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morrison EW. (1994) Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: the importance of the employee’s perspective. Acad Manage J 37, 1543–67. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bartram D, Roe RA. (2005) Definition and assessment of competences in the context of the European diploma in psychology. Eur Psychol 10, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sobiraj S, Schladitz S, Küchler R, Otto K. (2017) Die Bedeutung von Motiven der Studienfachwahl Psychologie für den Berufserfolg von Frauen und Männern. Psychol Everyday Act 10, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Faupel S, Otto K, Krug H, Kottwitz MU. (2016) Stress at school? A qualitative study on illegitimate tasks during teacher training. Front Psychol 7, 1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zacher H, Schmitt A. (2016) Work characteristics and occupational well-being: the role of age. Front Psychol 7, 1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]