Abstract

Wnt signaling is one of the key regulators of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor progression. In addition to the classical receptor frizzled (FZD), various co-receptors including heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are involved in Wnt activation. Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a HSPG that is overexpressed in HCC and functions as a Wnt co-receptor that modulates HCC cell proliferation. These features make GPC3 an attractive target for liver cancer therapy. However, the precise interaction of GPC3 and Wnt, and how GPC3, Wnt and FZD cooperate with each other, are poorly understood. In this study, we established a structural model of GPC3 containing a putative FZD-like cysteine-rich-domain (CRD) at its N-terminal lobe. We found that F41 and its surrounding residues in GPC3 formed a Wnt-binding groove that interacted with the middle region located between the lipid thumb domain and the index finger domain of Wnt3a. Mutating residues in this groove significantly inhibited Wnt3a binding, β-catenin activation, and the transcriptional activation of Wnt-dependent genes. In contrast with the heparan sulfate (HS) chains, the Wnt-binding groove that we identified in the protein core of GPC3 seemed to promote Wnt signaling in conditions when FZD was not abundant. Specifically, blocking this domain using an antibody inhibited Wnt activation. In HCC cells, mutating residue F41 on GPC3 inhibited activation of β-catenin in vitro and reduced xenograft tumor growth in nude mice compared with cells expressing wild-type GPC3. Conclusion: Our investigation demonstrates a detailed interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a, reveals the precise mechanism of GPC3 acting as a Wnt co-receptor, and provides a potential target site on GPC3 for Wnt blocking and HCC therapy.

Keywords: Liver cancer, Wnt co-receptor, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, β-catenin

Introduction

Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and second most lethal malignancy worldwide. The majority of liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which accounts for 85–90% of primary liver cancer cases (1). Multiple chronic liver diseases caused by hepatitis virus infection, alcohol consumption, obesity and other risks frequently lead to the development of HCC and accelerate the heterogeneity (2). Unfortunately, due to the lack of curative treatments, HCC exhibits the greatest increase on both new cases and mortality rates among all cancers in the past decade (3). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop effective strategies for HCC therapy.

Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a cell-surface glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein that belongs to the heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) family (4, 5). GPC3 is highly expressed in at least 70% of HCC patients, but not in normal adult tissues. Moreover, the expression of GPC3 is correlated with poor clinical prognosis for HCC survival (6). Many studies have demonstrated that GPC3 is actively involved in regulating HCC tumor growth (7–9). These characteristics make GPC3 a promising target for HCC therapy (5). Currently, various strategies targeting GPC3 have been developed or evaluated in HCC patients, including therapeutic antibodies (10–13), immunotoxins (14), vaccines (15), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells (16–18).

GPC3 is an oncofetal protein that functions during the processes of embryonic development and tumorigenesis (4). In normal hepatocytes, GPC3 negatively regulates cell growth by interacting with CD81 (19, 20). A possible mechanism involves the interaction of GPC3 and CD81 which activates Hippo signaling and suppresses Yap activation (21). However, 70% of HCCs lack CD81 expression (21). In HCC, GPC3 might function as a Wnt co-receptor to recruit and concentrate Wnt at the cell surface, facilitate the interaction of Wnt with their receptor frizzled (FZD), and reduce the threshold for Wnt activation (7, 8). Both the core protein and the heparan sulfate (HS) chains of GPC3 mediate Wnt activation. Our previous work identified a specific Wnt-binding motif on the HS chains contributing to Wnt activation (22). Other studies also found that the HS chains are important for FZD binding (23), suggesting its dual regulation on both the ligand and receptor of Wnt signaling. Although the interaction of Wnt and GPC3 core protein has been known for many years, their precise mechanism still remains unknown.

Wnt signaling plays pivotal roles in many physiological processes, including embryonic development, cell fate determination, stem cell maintenance, organ regeneration and tumorigenesis (24, 25). The activation of Wnt signaling is mainly triggered by the interaction between Wnt ligands with various FZD receptors. Many Wnt co-receptors, such as LRP5/6, ROR1, and HSPGs, also contribute to Wnt ligand-receptor complex formation and the initiation of Wnt activation (26). Currently, 19 Wnt ligands and 10 FZD receptors have been identified in humans. Wnt ligands are conserved, secreted, and highly hydrophobic cysteine-rich proteins (27). FZD receptors belong to the seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family and mainly function as Wnt receptors via their extracellular cysteine-rich-domain (CRD) (28). The crystal structure of the X. laevis Wnt8 and the mouse FZD8-CRD complex illustrates the precise interaction between Wnt and FZD showing that xWnt8 exhibits two conserved protruding finger-like domains that can grasp the FZD-CRD (29).

Currently, six glypican proteins (GPC1 to GPC6) and two glypican homolog proteins (Dally and Dally-like protein (Dlp)) have been identified in mammals and Drosophila, respectively (4). Among them, the crystal structures of Dlp (30) and human GPC1 (31) have been resolved. Although the sequence identity between these two proteins are approximately 25%, their crystal structures are similar due to the 14 conserved cysteines which are present in all glypicans to form 7 intra-molecular disulfide bonds to maintain a stable structure.

In the current study, we established a structural model of GPC3 and identified a Wnt-binding groove located in a CRD domain at the N-lobe of GPC3. This groove interacted with the middle region of Wnt3a between the two finger-like domains. Mutation of the Wnt-binding groove significantly reduced Wnt binding, attenuated Wnt activation, and inhibited HCC tumor growth in mice. This work reveals the precise interaction between GPC3 and Wnt, provides direct evidence to support GPC3 as a Wnt co-receptor, and identifies a promising target site on GPC3 to block interactions with Wnt, which could be applied towards HCC therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

HEK293T and Hep3B cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Huh-7 cells were obtained from Dr. Xin-Wei Wang at the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. The HEK293 Topflash stable cell line was a gift from Dr. Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins Medical School (32). The L-Wnt3a cell line was provided by Dr. Yingzi Yang, NHGRI, NIH (currently at Harvard University). GPC3 knockout Hep3B and Huh-7 cell lines were constructed using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. Two sgRNAs targeted the promoter region of endogenous GPC3. GPC3 KO cells were obtained by single-clone selection. All the cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (VACCA, St. Louis, MO), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Hyclone, Logan, UT). All cell lines were evaluated and validated by their morphology and growth rate. All the cell lines were confirmed free of mycoplasma contamination by PCR using specific primers.

Plasmids and antibodies.

All Wnt plasmids were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). The sequence of full-length GPC3 was cloned into the pLVX vector. The mutant of GPC3 lacking the HS chains (GPC3ΔHS) was produced by introducing point mutations (S495A and S509A) using the overlapping PCR method (5, 13). All point mutations of GPC3 (F41E, L66A, L92E, A96L, W260R, Y264K, L268E, M269S, Y277A, Y408D, L421E, W423A, L428R and Y432A) and Wnt3a (C77A, C77A&S209A, G99K, D103R, S209A, P278A, P283A, P285A, W333A, W333D and W333S) reported in the current study were generated by overlapping PCR. For the CRISPR-Cas9 vector, sgRNA pairs were designed using the website (http://crispr.mit.edu/). The two sgRNAs were treated with T4 PNK (NEB, Ipswich, MA) and then linked to the CrisprV2 backbone digested by Esp3I enzymes (Thermo, Waltham, MA). The antibodies targeting different epitopes on GPC3 were generated in the lab by mouse hybridoma (YP7(12)) or phage display (HN3(13)). Other antibodies: anti-Wnt3a (CST, Danvers, MA), anti-V5 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), anti-β-catenin (CST, Danvers, MA), anti-active β-catenin (CST, Danvers, MA) (33–35), anti-β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and anti-Ki67 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Sequence processing and structural modeling.

The human GPC3 sequence (NCBI Gene ID: 2719) with the signal peptide and heparan sulfate binding sites removed (remaining part: residues 32–483) was submitted to the protein structure homologous modeling web server SWISS-MODEL. Because the YP7 antibody was generated by immunizing mice with the C-terminal peptide (residues 511–560), we also modeled full-length GPC3 using the Phyre2 protein fold recognition server. The human Wnt3a sequence (NCBI Gene ID: 89780) with signal peptide deletion was submitted to SWISS-MODEL. All homolog template sequences and structure files (GPC1 PDB ID: 4YWT, xWnt8 PDB ID: 4F0A) were selected and downloaded from the RCSB protein data bank. ZDOCK SERVER was used to predict the epitope of HN3. PyMOL was used to analyze and render structure models.

Animal testing.

Four to six-week-old female BALB/c nu/nu nude mice were purchased from Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. All mice received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health. All mice were treated under the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Animal Core Facility of Nanjing Medical University. Five million WT, KO, KO-GPC3WT and KO-GPC3F41E Hep3B cells were re-suspended in 250 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and inoculated subcutaneously into mice. Tumor size was determined using calipers, and tumor volume (mm3) was calculated using the formula V = ab2/2, where a and b represent tumor length and width, respectively. When the average tumor size reached 1000 mm3~1500 mm3 (WT vs KO on day 30, KO-GPC3WT vs KO-GPC3F41E on day 44), the blood of each mouse was collected by cheek bleeding to measure alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). For survival comparison, mouse was considered at end point when the tumor size reached 2500 mm3.

Results

GPC3 interacts with Wnt and promotes activation of Wnt signaling

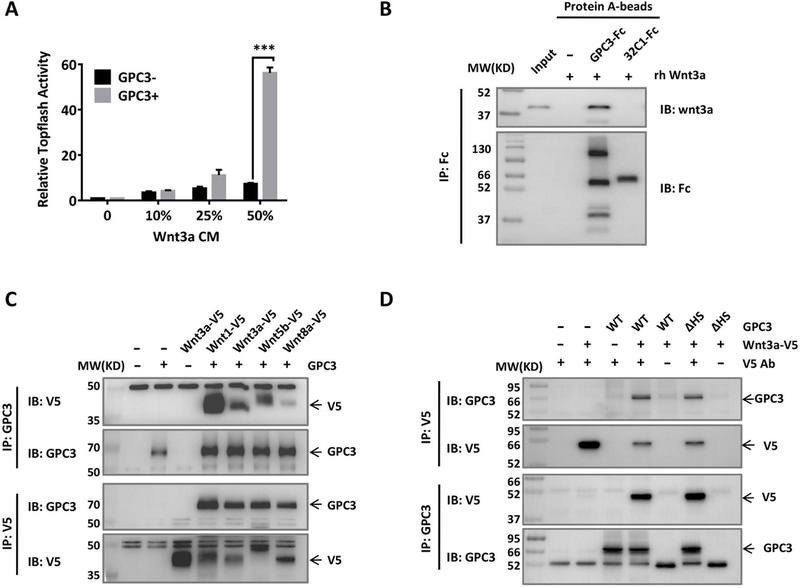

To evaluate the function of GPC3 in Wnt activation, we overexpressed GPC3 in HEK293 Topflash cells, a cell line stably expressing a luciferase reporter of β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation (32). After stimulating the cells with increasing concentrations of Wnt3a CM, we found that overexpression of GPC3 dramatically promoted Wnt activation (Fig. 1A). To determine whether this elevated activation was mediated by a direct interaction between GPC3 and Wnt3a, we incubated purified hFc-tagged GPC3 protein with recombinant human Wnt3a and performed an in vitro pull-down assay. Purified GPC3 protein bound Wnt3a specifically, indicating a direct interaction between GPC3 and Wnt3a (Fig. 1B). We then co-transfected GPC3 with several V5-tagged Wnt proteins in HEK293T cells. In addition to Wnt3a, Co-IP assays indicated that GPC3 also interacted with Wnt1, Wnt5b and Wnt8a (Fig. 1C). Given that Wnt proteins are highly conserved, our data implies that GPC3 might interact with different Wnt through a conserved structure. We also co-transfected wild-type GPC3 or a mutant GPC3 lacking HS chains (GPC3ΔHS) (13) with Wnt3a. Co-IP analysis showed that removing the HS chains of GPC3 did not influence Wnt3a binding (Fig. 1D). Altogether, our data show that GPC3 promotes Wnt activation through a conserved, HS-independent interaction with Wnt.

Fig. 1. GPC3 interacted with Wnt and promoted Wnt activation.

A. Topflash assay to evaluate the effect of GPC3 on Wnt activation. Different amounts of Wnt3a CM were added to HEK293 Topflash cells transfected with or without GPC3. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h later. The data represent the mean ± SD (***P<0.001). B. Pull-down assays to detect the interaction of GPC3-Fc and recombinant human Wnt3a (rhWnt3a) in vitro. 32C1-Fc was used as an Fc control protein. The immunoprecipitated complex was detected with an anti-Wnt3a antibody or an anti-Fc antibody. C. Co-IP assay to detect the interactions of GPC3 with different Wnt ligands. HEK293T cells were transfected with various V5-tagged Wnt and full-length GPC3. Lysates from the cells were used for immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 or anti-GPC3 antibodies. D. Co-IP assay to detect the effect of HS chains on the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a. Wild-type GPC3 or GPC3ΔHS was co-transfected with V5-tagged Wnt3a. Lysates from the cells were used for immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 and anti-GPC3 antibodies.

Prediction of a FZD-like CRD domain in a GPC3 structure model

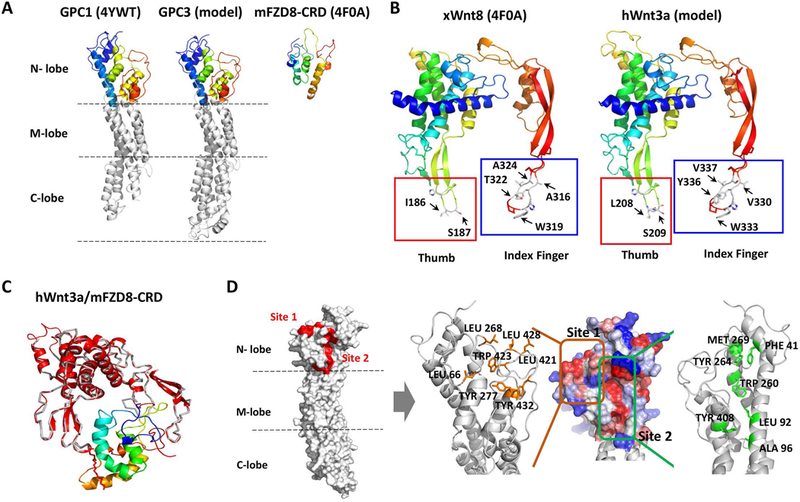

Using homology modeling based human GPC1 structure, we established a structural model of human GPC3 (SWISS-MODEL). The modeled structure of GPC3 exhibited similarity to GPC1. The modeled GPC3 had a cylinder shape with an N-terminal lobe containing six of seven disulfide bonds (also called the cysteine-rich lobe), a central or middle lobe, and a C-terminal lobe carrying the last disulfide bond (Fig. 2A). We also performed negative staining electron microscopy on purified recombinant wild-type GPC3 and GPC3ΔHS proteins. The average 2D classes of GPC3 appeared similar to those of our modeled GPC3. The presence or absence of HS chains had no effect on the overall structure of the core protein of GPC3 suggesting the reliability of our GPC3 model (Fig. S1). Interestingly, a segment of the cysteine-rich lobe was predicted to be a homolog of FZD-CRD by the Phyre2 online protein Homology/analog Recognition Engine (Fig. 2A). Since the CRD domain of FZD directly mediates Wnt/FZD binding, we suspected that the analogous N-terminal lobe of GPC3 might be relevant to Wnt binding.

Fig. 2. Prediction of the potential Wnt-binding site on GPC3.

A. Comparison of GPC1 (PDB: 4YWT), GPC3 (model) and mFZD8-CRD (PDB: 4F0A). The GPC3 modeled structure was predicted by SWISS-MODEL. N-lobe: amino-terminal lobe; M-lobe: middle lobe; C-lobe: carboxy-terminal lobe. B. Modeled human Wnt3a structure. Left: X. laevis Wnt8 (PDB: 4F0A); right: modeled hWnt3a (predicted by SWISS-MODEL). The thumb sites were labeled with red squares, and the index finger sites were labeled with blue squares. C. The superimposed model for hWnt3a/mFZD8-CRD. The gray ribbon was the xWnt8 crystal structure, with lipid shown as red sticks. The red cartoon was the modeled hWnt3a, which was superimposed on xWnt8 in the crystal structure of xWnt8/mFZD8-CRD. mFZD8-CRD was shown in a rainbow-colored schematic. D. Two predicted regions with exposed hydrophobic surface in modeled GPC3. Left: Position of the two predicted hydrophobic regions (red) on the N-lobe of modeled GPC3. Right: A close-up view of the GPC3 N-lobe model. The surface was colored to indicate the hydrophobicity of each amino acid (red, most hydrophobic; blue, most hydrophilic). Site 1 (orange square) indicated the hydrophobic patch; site 2 (green square) indicated the region of the hydrophobic groove. Residues selected for mutation were labeled in orange and green, respectively (right).

The hydrophobic groove on the putative CRD of GPC3 mediates Wnt binding and activation of Wnt signaling

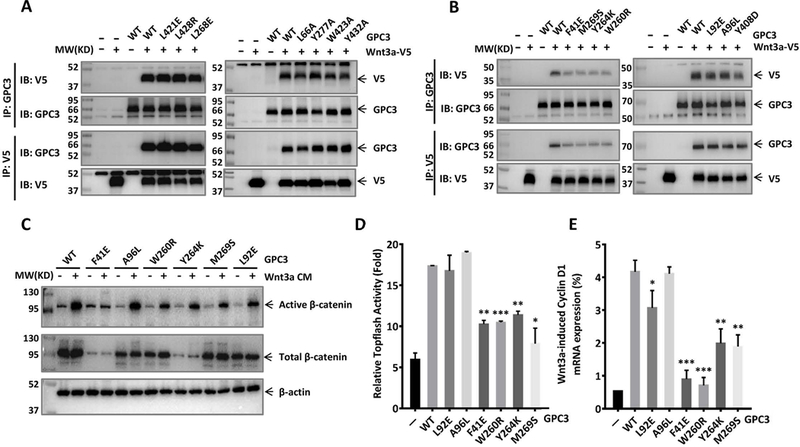

To verify our hypothesis that GPC3-CRD is relevant to Wnt binding, we tried to establish a Wnt/GPC3 complex model to investigate the interaction between GPC3 and Wnt. Since Wnt3a is one of the classical Wnt ligands and either commercial human Wnt3a (hWnt3a) protein or its conditioned media can be obtained, we modeled the hWnt3a structure using SWISS-MODEL. Overall, the predicted hWnt3a structure was similar to the known xWnt8 structure, especially at the two-finger tips of hWnt3a which shared high sequence similarity with xWnt8 (Fig. 2B). After hWnt3a was superimposed on xWnt8 in the xWnt8/mFZD8-CRD complex, the mFZD8-CRD was docked with hWnt3a (Fig. 2C). We hypothesized that hWnt3a would bind similarly to GPC3-CRD through the thumb and index finger domains, as shown in xWnt8 binding to mFZD8-CRD. However, the similarity between FZD-CRD and GPC3-CRD was not sufficient enough to build a useful model by simply superimposing their CRDs (data not shown). As an alternative, we examined the CRD within the GPC3 model for hydrophobic grooves and patches, which might provide an interacting surface for the hydrophobic region of Wnt3a, such as the palmitoleic acid moiety. Using this approach, we proposed two hydrophobic regions (site 1 and site 2) in the CRD domain of GPC3 as the potential Wnt-binding area (Fig. 2D). We selected several amino acids within our predicted areas and constructed point mutations of these residues by reducing the hydrophobicity of site 1 or site 2. For site 1, four exposed residues were mutated to reduce the surface hydrophobicity (L66A, L268E, L421E and L428R). In addition, three buried residues were mutated into alanine (Y277A, W423A and Y432A). For site 2, six point mutations (F41E, L92E, W260R, Y264K, M269S, and Y408D) in the hydrophobic groove (site 2) were made in order to reduce the exposed hydrophobic area. A96L was made to increase the surface hydrophobicity of site 2. The mutation of each residue was validated by structure modeling to confirm that it might not affect the conformation of GPC3 (Fig. S2). We co-transfected all mutant GPC3 constructs with Wnt3a and analyzed their interactions. We found that mutations in site 1 did not affect the binding of Wnt3a (Fig. 3A), whereas mutations in site 2, especially F41 and its surrounding residues (W260, Y264 and M269), significantly abolished Wnt3a binding (Fig. 3B), indicating the importance of this site for Wnt3a recognition.

Fig. 3. Identification of the Wnt-binding area of GPC3.

Wild-type or mutant GPC3 were co-transfected with V5-tagged Wnt3a in HEK293T cells. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were lysed and incubated with GPC3 antibody or V5 antibody to detect the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a by Co-IP assay. A. Co-IP assay to detect the effect of site 1 on the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a. B. Co-IP assay to detect the effect of site 2 on the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a. C. HEK293 Topflash cells were transfected with indicated mutant GPC3. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, the cells were starved for 12 h and then stimulated with 50% Wnt3a CM. Twelve hours later, the expression levels of active β-catenin (C), Topflash reporter activity (D), and mRNA expression level of Cyclin D1 (E) were measured. The results are represented at least three independent experiments. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001).

We then overexpressed those mutations in HEK293 Topflash cells and then treated the cells with Wnt3a CM. As expected, the mutations around the F41 area significantly inhibited β-catenin activation (Fig. 3C). Consistently, Wnt3a-induced Topflash activity, as well as the mRNA expression of Cyclin D1, a representative target gene of Wnt signaling, were both impaired in cells transfected to express proteins with mutations around F41 (Fig. 3D and Fig. 3E). Overall, these data show that F41 and its surrounding residues in GPC3 form an important area for Wnt binding and activation.

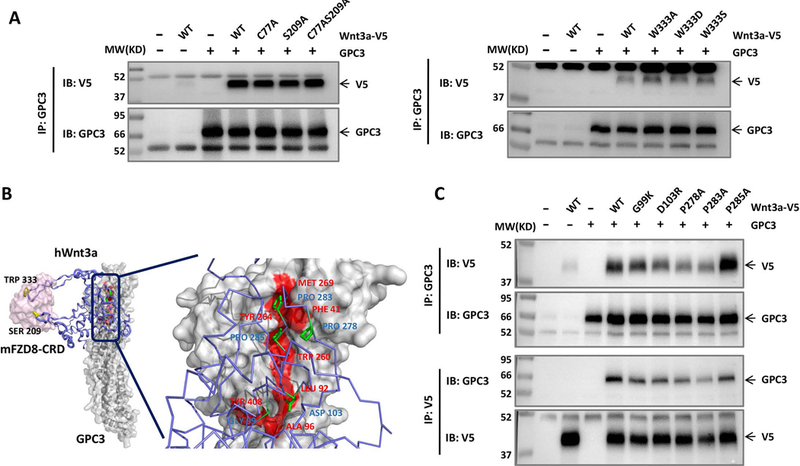

Wnt3a interacts with GPC3 through the middle region between its two finger-like domains

To identify the exact GPC3 binding region on Wnt3a, point mutations were made at S209 and W333, which mediates the lipid thumb domain-FZD interaction and index finger domain-FZD interaction, respectively (36, 37). We also made the mutation of residue C77, another palmitoylated modification site of Wnt3a (36). Neither of these mutations influenced GPC3 binding (Fig. 4A), indicating that Wnt3a does not bind to GPC3 through its lipid thumb domain or index finger domain. We next designated the identified hydrophobic groove (site 2) to be the interactive interface of GPC3 and Wnt3a, and docked Wnt3a with GPC3 using the ZDOCK SERVER. From our predicted model, we suspected that two separate small loops (G99 to D103; P278 to P285) located at the middle region of Wnt3a would be important for the interaction with GPC3 (Fig. 4B). Point mutations were created in those regions and their interactions with GPC3 were detected. As expected, mutations in these two loops caused a dramatic decrease in Wnt3a binding, indicating that these two regions of Wnt3a were responsible for the binding of GPC3 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Identification of the GPC3-binding area of Wnt3a.

A. Co-IP assay to detect the effect of two finger-like domains of Wnt3a on GPC3 interaction. V5-tagged Wnt3a with a point mutation in the lipid thumb domain (S209) or in the index finger domain (W333) was co-transfected with GPC3 in HEK293T cells. Residue C77 is another palmitoylated modification site of Wnt3a(36). Twenty-four hours later, the cells were lysed and incubated with GPC3 antibody or V5 antibody to detect the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a. B. The predicted model of mFZD8-CRD/hWnt3a/GPC3 complex. GPC3 and mFZD8-CRD were shown in surface representation (mFZD8-CRD in pink and GPC3 in gray), and hWnt3a was shown with the purple cartoon/stick representation. The residues in Wnt3a essential for GPC3 binding were labeled in blue. The residues in the region of the hydrophobic groove (site 2) for Wnt binding were labeled in red. C. V5-tagged Wnt3a with the point mutations shown in B was co-transfected with GPC3 in HEK293T cells. The interaction of GPC3 and Wnt3a was detected by Co-IP with the method described in A.

The Wnt-binding area of the GPC3 core protein regulates Wnt signaling when FZD is not abundant

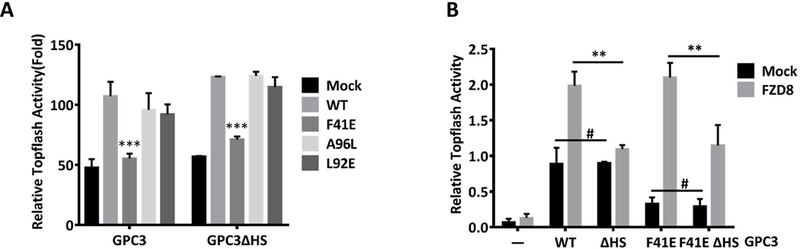

Our previous work demonstrated that the HS chains of GPC3 played important roles in Wnt activation. After we identified that the core protein of GPC3 mediated the activation of Wnt signaling through a hydrophobic groove area (site 2), we decided to determine whether the HS chains of GPC3 were involved in this process. We selected F41E as a representative mutation for further evaluation due to its significant inhibitory effect on Wnt activation. Topflash assay showed that the HS chains of GPC3 had no influence on the effects caused by either F41E or control mutations (L92E and A96L) (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, when we introduced mFZD8 into the assay, an altered Wnt activation pattern appeared. Overexpression of GPC3 alone promoted Wnt3a-induced Topflash activity, which could be reduced by the F41E mutation, but not by removing HS chains. In contrast, co-transfection of GPC3 and mFZD8 caused a synergistic activation of Topflash activity. This synergistic effect could be abolished by removing the HS chains of GPC3, but the F41E mutation did not show any impact (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the core protein and the HS chains of GPC3 regulate Wnt signaling via different mechanisms: GPC3 promotes Wnt activation through its core protein (site 2) when FZD is not abundant, but when FZD is abundant, GPC3 exhibits a HS-dependent pattern of increasing Wnt activation.

Fig. 5. The influence of HS chains of GPC3 on F41-mediated Wnt activation.

A. Topflash reporter assay to detect the effect of the mutation F41E with or without HS chains on Wnt activation. HEK293 Topflash cells were transfected with wild-type GPC3 or GPC3ΔHS carrying the indicated point mutation. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, the cells were starved for 12 h and luciferase activity was measure after stimulation with 50% Wnt3a CM for 12h. The data represent the mean ± SD (***P<0.001). B. Topflash assay to compare the effect of HS chain-mediated and F41-mediated Wnt activation with or without mFZD8. HEK293 Topflash cells were co-transfected with the indicated mutant GPC3 and mFZD8. The cells were then treated as described in A. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P<0.01, #P>0.05).

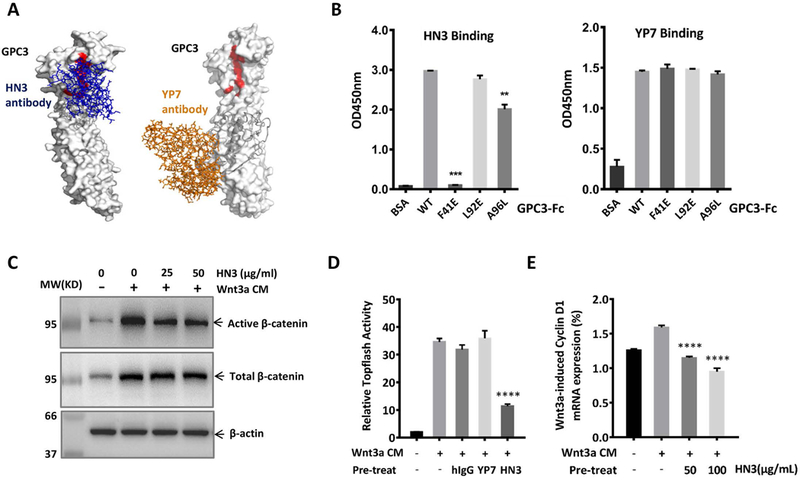

Blocking the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 by an antibody inhibits the activation of Wnt signaling

After identifying site 2 as the Wnt-binding area on the protein core of GPC3, we suspected that blocking this area would disturb Wnt signaling. In our previous studies, we developed HN3, a single-domain human antibody recognizing the N-terminal cryptic conformational epitope of GPC3 (13). HN3-toxin conjugate exhibited significant inhibition on the activation of Wnt signaling (14). Therefore, we predicted that the epitope of HN3 might cover or partially overlap with site 2 area of GPC3. To confirm it, we designated the three complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of HN3 as the interactive interface and docked HN3 to the modeled GPC3. Interestingly, the predicted region recognized by HN3 covered the site 2 area (Fig. S3 and Fig. 6A). Consistently, HN3 completely lost binding to GPC3 when F41 was mutated, and partially lost when A96 was mutated (Fig. 6B). These observations were not caused by conformation changes induced by the point mutations according to our computational analysis (Fig. S2) and experimental analysis using the YP7 antibody. YP7 is a mouse monoclonal antibody produced via immunization with a C-terminal peptide of GPC3 (residues 511–560) (12) and shows equal binding activity on both wild-type GPC3 and mutant GPC3 (Fig. 6A and Fig. 6B), indicating no significant conformational change of these GPC3 mutants. Therefore, HN3 would theoretically compete with Wnt3a for GPC3 binding by blocking the site 2 area. To test this, we pretreated HEK293 Topflash-GPC3 cells with HN3, and then detected the activation of Wnt signaling. The pretreatment of HN3 significantly reduced Wnt3a-induced activation of β-catenin (Fig. 6C), inhibited Wnt3a-induced Topflash reporter activity (Fig. 6D) and reduced the mRNA expression of Cyclin D1 (Fig. 6E). Altogether, our results prove that targeting the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 by an antibody can block Wnt signaling.

Fig. 6. Antibody HN3 recognized the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 and blocked Wnt activation.

A. Putative binding of HN3 and YP7 on modeled GPC3. The Wnt-binding area (site 2) was labeled in red. Left: HN3 (blue stick) was docked on the modeled GPC3 by setting its three CDRs as the interactive interface. Right: YP7 (orange stick) was docked on the modeled full-length GPC3 (by Phyre2) by setting its six CDRs as the interface. The sequence corresponding to the peptide used to immunize mice for generating YP7 was labeled in grey. B. ELISA to detect HN3 and YP7 binding activity on wild type and site 2 mutant GPC3. Purified wild-type GPC3 or the indicated GPC3 mutant proteins were coated on ELISA plates. After blocking, HN3 or YP7 were added to detect the binding activity at OD450 nm. The results are represented at least three independent experiments. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001). C. Western blot to detect the blocking effect of HN3 on Wnt3a-induced β-catenin activation. HEK293 Topflash-GPC3 stable cells were starved overnight and pre-treated with HN3 for 30 minutes. Then 50% Wnt3a CM were added. Six hours later, cells were harvested to detect the expression of active β-catenin (C), Topflash reporter activity (D) and mRNA expression of Cyclin D1 (E). The results are represented at least three independent experiments. The data represent the mean ± SD (**P<0.01).

Mutation of the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 impairs Wnt activation in HCC cells

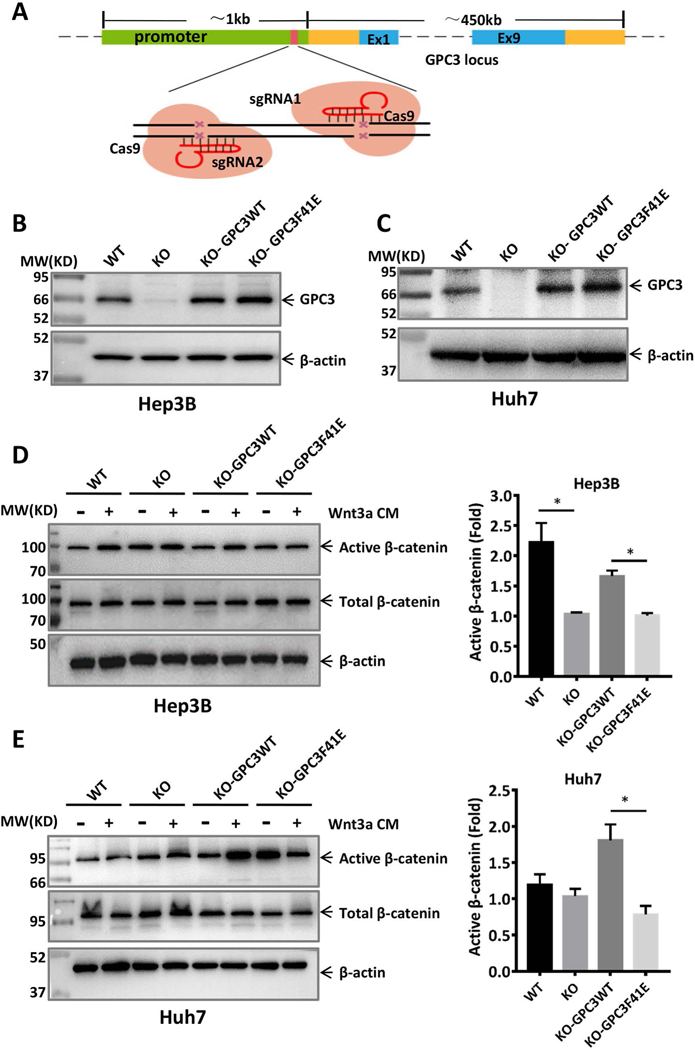

To investigate whether the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 also plays a role in HCC, we constructed GPC3WT- and GPC3F41E-overexpressing HCC cell lines. In Hep3B and Huh-7 cell models, we eliminated endogenous GPC3 using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. We designed several sgRNAs targeting the promoter region of GPC3 to ensure that the coding sequence of re-introduced GPC3 would not be targeted (Fig. 7A). After successful GPC3 knockout in Hep3B and Huh-7 cells (Fig. S4), we re-expressed GPC3WT and GPC3F41E into knockout cells (Fig. 7B and Fig. 7C). In both HCC cell models, Wnt3a induced activation of β-catenin when GPC3WT was overexpressed, but no obvious activation of β-catenin was observed when GPC3F41E was expressed (Fig. 7D and Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7. GPC3F41E caused impaired Wnt activation in HCC cells.

A. Schematic for constructing GPC3 knockout cell lines using CRISPR-Cas9. Two sgRNAs were designed to target the promoter of the GPC3 gene. B. Re-expression of GPC3WT and GPC3F41E in GPC3 knockout Hep3B cells (clone 12). C. Re-expression of GPC3WT and GPC3F41E in GPC3 knockout Huh-7 cells (clone 15). WT: wild type, KO: knockout. Cells constructed in B and C were starved overnight and then treated with or without 50% Wnt3a CM for 12 h. Western blot to show the expression of active β-catenin in D and E, respectively. The statistical analyses were shown as fold change by density calculating from three independent experiments. The data represent the mean ± SD (*P<0.05).

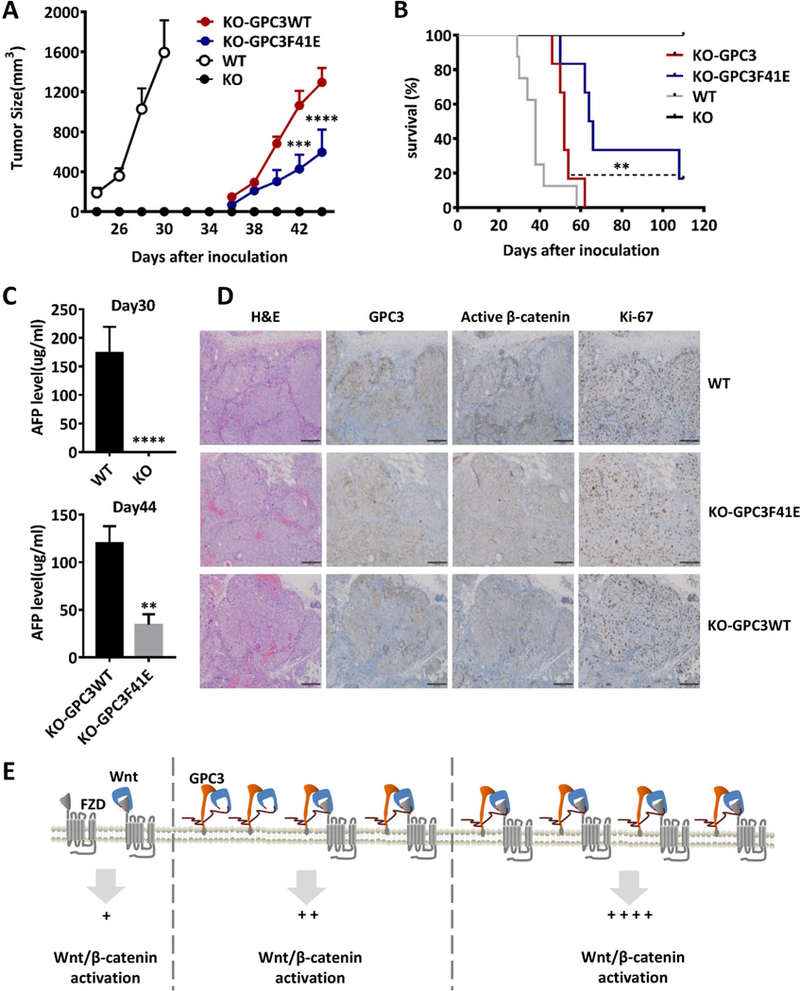

We next inoculated four Hep3B cell lines subcutaneously into nude mice. In contrast to the rapid tumor growth observed in the wild-type Hep3B group, GPC3 knockout cells could not form xenograft tumors in mice (Fig. 8A). We previously demonstrated that GPC3 knockdown (13) or recombinant soluble GPC3 (GPC3ΔGPI) (38), functioning as a dominant-negative form, could inhibit HCC cell proliferation in vitro. Our current GPC3 knockout data further validates the proliferative role for GPC3 in HCC tumorigenesis. Interestingly, the KO-GPC3WT cells and KO-GPC3F41E cells both formed xenograft tumors with delayed initiation. This phenomenon most likely occurred because we used a GPC3 knockout single cell clone (clone 12) to construct the KO-GPC3WT cells and KO-GPC3F41E cells.

Fig. 8. GPC3F41E inhibited HCC tumor growth in mice.

BALB/c nu/nu mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5×106 WT, KO, KO-GPC3WT, and KO-GPC3F41E Hep3B cells. A. Tumor growth curve. WT n=11; KO n=9; KO-GPC3WT n=9; KO-GPC3F41E n=8. The data represent the mean ± SE (***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001). B. Survival curve. WT n=8; KO n=9; KO-GPC3WT n=6; KO-GPC3F41E n=6 (**P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001). C. AFP level of mice at day 30 (WT n=11; KO n=9) and day 44 (KO-GPC3WT n=7; KO-GPC3F41E n=6). The data represent the mean ± SE (**P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001). D. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry staining for GPC3, active β-catenin and Ki-67 in the tumors from A. Scale bar, 200 μm. E. The working model of GPC3 regulating Wnt activation in HCC cells.

Compared to wild-type Hep3B cells, these two cell lines had similar expression level of GPC3, but might have clonal variation and low heterogeneity. As expected, the xenograft tumor growth in the KO-GPC3F41E group was significantly slower than that of the KO-GPC3WT group (Fig. 8A). These data showed that re-introducing GPC3 into GPC3 knockout cells could rescue GPC3-mediated HCC tumor growth. Disrupting the Wnt-binding area of GPC3 attenuated the re-emergence of tumor growth and dramatically extended mouse survival (Fig. 8B). We also measured the expression level of AFP in each group and observed a similar trend (Fig. 8C). Ki-67 staining showed that the tumors in the KO-GPC3F41E group had fewer proliferative cells than both the WT-Hep3B tumors and KO-GPC3WT tumors. Moreover, the staining of active β-catenin in the KO-GPC3F41E tumors did not show apparent differences with KO-GPC3 tumor, but both were significantly weaker than wild type Hep3B tumors (Fig. 8D).

Overall, we observed that GPC3 interacted with the middle section of Wnt3a through a hydrophobic groove near residue F41. This Wnt-binding area of GPC3 mediated Wnt activation in vitro and regulated HCC tumor growth in mice. Our results demonstrate a novel mechanism in which the core protein of GPC3 functions as a Wnt co-receptor (Fig. 8E), suggesting a precise targeting site for blocking Wnt signaling in HCC cells.

Discussion

In the current study, we identified a Wnt-binding area located in a predicted CRD region of GPC3 and revealed a detailed binding pattern of the Wnt3a and GPC3 core protein. Our findings illustrated a novel mechanism by which GPC3 functions as a Wnt co-receptor in HCC beyond previously reported HS chain-mediated regulation.

The predicted GPC3-CRD contains six disulfide bonds, whereas the typical FZD-CRD contains only five. Interestingly, a previous study performed a computational analysis to expand homologs of FZD-CRDs and the related domains, HFN-CRDs. By rigorous structure and sequence comparisons, the authors found that glypicans belonged to the HFN-CRD family, but not the FZD-CRD family (39). Due to larger size caused by the extra disulfide bond, GPC3-CRD could not be docked to Wnt3a in a FZD-CRD-like pattern. Neither the lipid thumb domain nor the index finger domain of Wnt3a was found to interact with GPC3. We found that GPC3 interacted with the middle region of Wnt3a. Similarly, a recent study uncovered that Wnt7 specifically interacted with its co-receptor Reck through its linker region located between the lipid thumb domain and the index finger domain (40). Considering that both Reck and GPC3 are GPI-anchored proteins containing CRD, both function as Wnt co-receptors, and both interact with Wnt with low affinity, we suspect that interacting with the linker/middle region of Wnt might be a representative binding pattern for many Wnt co-receptors.

In our cell models containing sufficient Wnt3a, GPC3 induced different patterns of Wnt activation that depend on the abundance of FZD. It seems that the activation of Wnt signaling relies on the core protein rather than the HS chains only when endogenous levels of FZD are present. Although exhibiting weak Wnt binding, GPC3 could work as an alternative Wnt receptor and thus recruit and store Wnt on the cell surface to promote Wnt activation. Therefore, it is not surprising that such activation occurs moderately because those GPC3-recruited Wnt still need to access FZD. When FZD is expressed abundantly, GPC3 drives synergistic activation of Wnt signaling. This effect is mainly caused by the interaction of GPC3 and FZD through the HS chains. Based on our model in which GPC3, Wnt and FZD form a triple-complex, we suspect that GPC3 might function as a bridge to stabilize the interaction of Wnt and FZD instead of being an alternative Wnt receptor. Due to the complicated expression profiles of Wnt and FZD in HCC tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment, GPC3 might perform flexible regulation through either mechanism described above or a combination of mechanisms.

In our animal model, re-expression of GPC3 in GPC3 knockout Hep3B cells led to the re-emergence of tumors in mice. We observed a delay in tumor initiation in the GPC3 rescued groups as compared to the wild-type Hep3B group. Studies have shown that intra-tumor clonal heterogeneity plays essential roles in tumor progression. Due to the enriched genetic and epigenetic diversities, different subsets of tumor cells cooperate with each other, contribute to the malignant phenotype of tumor, and gain a selective growth advantage in cancer (41, 42). The KO-GPC3WT and KO-GPC3F41E cells are constructed based on the single cell-cloned GPC3 knockout line. The heterogeneity in wild-type Hep3B cells might be partially lost during the single cell cloning. In addition, we cannot rule out the individual clonal variation as a result of the exogenous GPC3 genomic integration site may play a role in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Additionally, the KO-GPC3F41E cells exhibited slower tumor growth compared to KO-GPC3WT cells, and the active β-catenin level between these two groups was not significantly different. Multiple reasons underlie this phenomenon. First, F41 is one of the critical amino acids located in the Wnt-binding area, and mutation of F41 may significantly reduce, but not completely abolish Wnt binding. Therefore, we expect that KO-GPC3F41E could still partially rescue tumorigenesis. Second, as discussed above, GPC3 regulates Wnt activation through dual mechanisms, thus the core protein-mediated Wnt activation might switch to HS chain-mediated activation when F41 is mutated. In addition, other signaling pathways like HGF/c-Met and Yap modulated by GPC3 might also compensate for Wnt signaling at the β-catenin level in this circumstance (14, 43, 44).

HCC patients frequently exhibit up-regulation of Wnt and FZD or down-regulation of the Wnt inhibitory molecule like sFRP1 (45). Therefore, developing specific antibodies against Wnt or FZD is a potential approach for HCC therapy (46, 47). However, both Wnt and FZD are universally expressed, so targeting either Wnt or FZD would lead to uncertain on-target and off-tumor effects. Therefore, targeting a tumor-specific Wnt co-receptor like GPC3 in HCC represents an alternative strategy. Our previous work demonstrated that functional blocking of GPC3 using the single-domain antibody HN3 worked better in an antibody-toxin format for treating HCC tumors because HN3-based immunotoxin mediated dual-mechanism killing, including toxin cytotoxicity and Wnt blocking (13, 14). The current study extends the previous investigation by revealing mechanism by which HN3 blocks Wnt signaling at the structural level. With recent approval of an immunotoxin against CD22 by the FDA for hairy cell leukemia (48), we are looking forward to seeing the potential clinical application of a GPC3-targeted HN3-derived immunotoxin for HCC therapy.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a detailed interaction between GPC3 and Wnt3a by structural analysis and functional evaluation. These findings improve our understanding of the mechanisms by which GPC3 cooperates with the Wnt/FZD complex to promote HCC tumor growth. Moreover, we present a feasible example of blocking Wnt signaling by targeting the functional area of GPC3. Therefore, our findings reveal an essential biological function of GPC3, illustrate a novel GPC3-mediated Wnt activation mechanism, and provide a functional target for HCC therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH Fellows Editorial Board for editorial assistance, and Jessica Hong (NCI) and Aarti Kolluri (NCI) for proofreading the manuscript. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) holds patent rights to anti-GPC3 antibodies including HN3, YP7 and HS20 in many jurisdictions, including the USA (e.g., US Patent 9409994, US Patent 9206257, US Patent 9304364, US Patent 9932406, US Patent Application 62/716169, US Patent Application 62/369861), China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Europe. Claims cover the antibodies themselves as well as conjugates that utilize the antibodies, such as recombinant immunotoxins (RITs), antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies, and modified T cell receptors (TCRs)/chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) and vectors expressing these constructs. Anyone interested in licensing these antibodies can contact Dr Mitchell Ho (NCI) for additional information.

Financial Support:

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81773260), National Natural Science Foundation Youth Project of Jiangsu, China (No. BK20171047), and by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research (Z01 BC010891 and ZIA BC010891) to M.H.

List of Abbreviations:

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- GPC3

Glypican-3

- GPI

glycophosphatidylinositol

- HSPG

heparan sulfate proteoglycans

- FZD

frizzled

- GPCRs

G-protein coupled receptors

- CRD

cysteine-rich-domain

- Dlp

Dally-like protein

- KO

knockout

- CM

conditioned medium

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- CDR

complementarity-determining region

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Contributor Information

Na Li, Email: lina0707@njmu.edu.cn.

Liwen Wei, Email: hzauwlw@163.com.

Xiaoyu Liu, Email: lxy@njmu.edu.cn.

Hongjun Bai, Email: hbai@hivresearch.org.

Yvonne Ye, Email: yy373@cornell.edu.

Dan Li, Email: dan.li2@nih.gov.

Nan Li, Email: nan.li@nih.gov.

Ulrich Baxa, Email: baxau@mail.nih.gov.

Qun Wang, Email: qun_300@hotmail.com.

Ling Lv, Email: lvling@njmu.edu.cn.

Yun Chen, Email: chenyun@njmu.edu.cn.

Mingqian Feng, Email: fengmingqian@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Byungkook Lee, Email: bk7lee@yahoo.com.

Wei Gao, Email: gao@njmu.edu.cn.

Mitchell Ho, Email: homi@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer C, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol 2008;9:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho M, Kim H. Glypican-3: a new target for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirakawa H, Suzuki H, Shimomura M, Kojima M, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, Nakagohri T, et al. Glypican-3 expression is correlated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2009;100:1403–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res 2005;65:6245–6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai JP, Oseini AM, Moser CD, Yu C, Elsawa SF, Hu C, Nakamura I, et al. The oncogenic effect of sulfatase 2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated in part by glypican 3-dependent Wnt activation. Hepatology 2010;52:1680–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao W, Kim H, Feng M, Phung Y, Xavier CP, Rubin JS, Ho M. Inactivation of Wnt signaling by a human antibody that recognizes the heparan sulfate chains of glypican-3 for liver cancer therapy. Hepatology 2014;60:576–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu AX, Gold PJ, El-Khoueiry AB, Abrams TA, Morikawa H, Ohishi N, Ohtomo T, et al. First-in-man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican-3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Okusaka T, Mitsunaga S, Kobayashi S, Morizane C, Suzuki I, et al. Japanese phase I study of GC33, a humanized antibody against glypican-3 for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2014;105:455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phung Y, Gao W, Man YG, Nagata S, Ho M. High-affinity monoclonal antibodies to cell surface tumor antigen glypican-3 generated through a combination of peptide immunization and flow cytometry screening. MAbs 2012;4:592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng M, Gao W, Wang R, Chen W, Man YG, Figg WD, Wang XW, et al. Therapeutically targeting glypican-3 via a conformation-specific single-domain antibody in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E1083–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao W, Tang Z, Zhang YF, Feng M, Qian M, Dimitrov DS, Ho M. Immunotoxin targeting glypican-3 regresses liver cancer via dual inhibition of Wnt signalling and protein synthesis. Nat Commun 2015;6:6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawada Y, Yoshikawa T, Ofuji K, Yoshimura M, Tsuchiya N, Takahashi M, Nobuoka D, et al. Phase II study of the GPC3-derived peptide vaccine as an adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1129483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao H, Li K, Tu H, Pan X, Jiang H, Shi B, Kong J, et al. Development of T cells redirected to glypican-3 for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:6418–6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan Z, Di S, Shi B, Jiang H, Shi Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Increased antitumor activities of glypican-3-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells by coexpression of a soluble PD1-CH3 fusion protein. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018;67:1621–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Guo L, Rathi P, Marinova E, Gao X, Wu MF, Liu H, et al. Redirecting T Cells to Glypican-3 with 4–1BB Zeta Chimeric Antigen Receptors Results in Th1 Polarization and Potent Antitumor Activity. Hum Gene Ther 2017;28:437–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu B, Bell AW, Paranjpe S, Bowen WC, Khillan JS, Luo JH, Mars WM, et al. Suppression of liver regeneration and hepatocyte proliferation in hepatocyte-targeted glypican 3 transgenic mice. Hepatology 2010;52:1060–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhave VS, Mars W, Donthamsetty S, Zhang X, Tan L, Luo J, Bowen WC, et al. Regulation of liver growth by glypican 3, CD81, hedgehog, and Hhex. Am J Pathol 2013;183:153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue Y, Mars WM, Bowen W, Singhi AD, Stoops J, Michalopoulos GK. Hepatitis C Virus Mimics Effects of Glypican-3 on CD81 and Promotes Development of Hepatocellular Carcinomas via Activation of Hippo Pathway in Hepatocytes. Am J Pathol 2018;188:1469–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao W, Xu Y, Liu J, Ho M. Epitope mapping by a Wnt-blocking antibody: evidence of the Wnt binding domain in heparan sulfate. Sci Rep 2016;6:26245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capurro M, Martin T, Shi W, Filmus J. Glypican-3 binds to Frizzled and plays a direct role in the stimulation of canonical Wnt signaling. J Cell Sci 2014;127:1565–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loh KM, van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Generating Cellular Diversity and Spatial Form: Wnt Signaling and the Evolution of Multicellular Animals. Dev Cell 2016;38:643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2016;36:1461–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Amerongen R Alternative Wnt pathways and receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller JR. The Wnts. Genome Biol 2002;3:REVIEWS3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malbon CC. Frizzleds: new members of the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors. Front Biosci 2004;9:1048–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science 2012;337:59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MS, Saunders AM, Hamaoka BY, Beachy PA, Leahy DJ. Structure of the protein core of the glypican Dally-like and localization of a region important for hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:13112–13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awad W, Adamczyk B, Ornros J, Karlsson NG, Mani K, Logan DT. Structural Aspects of N-Glycosylations and the C-terminal Region in Human Glypican-1. J Biol Chem 2015;290:22991–23008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Q, Wang Y, Dabdoub A, Smallwood PM, Williams J, Woods C, Kelley MW, et al. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell 2004;116:883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Wnt signaling in vertebrate axis specification. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013;5:a007955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yost C, Torres M, Miller JR, Huang E, Kimelman D, Moon RT. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev 1996;10:1443–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science 1997;275:1787–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR 3rd, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature 2003;423:448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takada R, Satomi Y, Kurata T, Ueno N, Norioka S, Kondoh H, Takao T, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev Cell 2006;11:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng M, Kim H, Phung Y, Ho M. Recombinant soluble glypican 3 protein inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Int J Cancer 2011;128:2246–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pei J, Grishin NV. Cysteine-rich domains related to Frizzled receptors and Hedgehog-interacting proteins. Protein Sci 2012;21:1172–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eubelen M, Bostaille N, Cabochette P, Gauquier A, Tebabi P, Dumitru AC, Koehler M, et al. A molecular mechanism for Wnt ligand-specific signaling. Science 2018;361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calbo J, van Montfort E, Proost N, van Drunen E, Beverloo HB, Meuwissen R, Berns A. A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2011;19:244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleary AS, Leonard TL, Gestl SA, Gunther EJ. Tumour cell heterogeneity maintained by cooperating subclones in Wnt-driven mammary cancers. Nature 2014;508:113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao W, Kim H, Ho M. Human Monoclonal Antibody Targeting the Heparan Sulfate Chains of Glypican-3 Inhibits HGF-Mediated Migration and Motility of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monga SP, Mars WM, Pediaditakis P, Bell A, Mule K, Bowen WC, Wang X, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces Wnt-independent nuclear translocation of beta-catenin after Met-beta-catenin dissociation in hepatocytes. Cancer Res 2002;62:2064–2071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bengochea A, de Souza MM, Lefrancois L, Le Roux E, Galy O, Chemin I, Kim M, et al. Common dysregulation of Wnt/Frizzled receptor elements in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2008;99:143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurney A, Axelrod F, Bond CJ, Cain J, Chartier C, Donigan L, Fischer M, et al. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:11717–11722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagayama S, Fukukawa C, Katagiri T, Okamoto T, Aoyama T, Oyaizu N, Imamura M, et al. Therapeutic potential of antibodies against FZD 10, a cell-surface protein, for synovial sarcomas. Oncogene 2005;24:6201–6212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreitman RJ, Tallman MS, Robak T, Coutre S, Wilson WH, Stetler-Stevenson M, Fitzgerald DJ, et al. Phase I trial of anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin moxetumomab pasudotox (CAT-8015 or HA22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1822–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.