Abstract

The spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) poses a serious threat to clinical practice and public health. These bacteria are present both in clinical settings and non-clinical environments. The presence of CPE in food stuffs has been reported, but sporadically so. Here, we screened for CPE in meat, seafood, and vegetable samples from local markets of Yangon, Myanmar. We obtained 27 CPE isolates from 93 food samples and identified 13 as Escherichia coli, six as Klebsiella pneumoniae, seven as Enterobacter cloacae complex, and one as Serratia marcescens. All except the E. cloacae complex harboured the carbapenemase genes blaNDM-1 or blaNDM-5, while all Enterobacter isolates carried the carbapenemase gene blaIMI-1. The blaIMI-1 gene was located in putative mobile elements EcloIMEX-2, -3, or -8. Using multi-locus sequence typing, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. cloacae complex isolates were classified into 10, six, and five different sequence types, respectively. Our results demonstrate that diverse organisms with various carbapenemase genes are widespread in the market foods in Yangon, highlighting the need for promoting proper food hygiene and effective measures to prevent further dissemination.

Subject terms: Antimicrobial resistance, Bacterial infection

Introduction

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae have become a global public-health concern because these bacteria cause high mortality and are multidrug-resistant1. This resistance is mainly due to the production of carbapenemases, which hydrolyse carbapenem antibiotics. Carbapenemase genes such as blaNDM are often in transmissible plasmids and thus spread readily among Enterobacteriaceae species2. Currently, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are found in both clinical and non-clinical settings, including sewage systems3,4. Alarmingly, CPE have been isolated from imported food stuffs (vegetables and seafood) originating in southeast Asian countries5,6. Despite the potential danger, thorough food surveillance is not performed on retail foods in CPE-endemic regions, with a few exceptions in China7,8.

Previously, we identified genetically diverse Enterobacteriaceae isolates with blaNDM-harbouring plasmids in a hospital of Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city9,10. We then found closely related strains in sewage water outside the hospital10, implying that CPE in clinical settings could reach the external environment. These findings prompted us to investigate the extent of CPE dissemination in local communities. Here, we focused on the spread of CPE in local markets.

Results

Diverse E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates harbouring blaNDM from market foods

Of the 93 food samples from eight markets, we identified 20 CPE-positive samples (21.5%). Within each food category (meat, seafood, and vegetables), the percentage of CPE-positive samples was 25.0% (8/32), 10.3% (3/29), and 28.1% (9/32), respectively (Table 1). We obtained 27 CPE isolates from the 20 samples, with 16 (59.3%) derived from vegetables. Water spinach exhibited the highest CPE-positive rate (4/8, 50%) and yielded eight CPE isolates. Of the 27 CPE isolates, 20 carried blaNDM, including 13 Escherichia coli, six Klebsiella pneumoniae, and one Serratia marcescens. All but one E. coli, along with four of six K. pneumoniae, possessed blaNDM-5; the remaining carried blaNDM-1 (Fig. 1). Every blaNDM-carrying isolate was resistant to imipenem. Those harbouring blaNDM-5 were also resistant to meropenem, but blaNDM-1 did not confer resistance to this antibiotic. All isolates were resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporin and oxacephem antibiotics, such as ceftazidime and moxalactam, and the minimum inhibitory concentration for these antibiotics was >64 µg/mL and ≥128 µg/mL, respectively. Additionally, 80% (16/20), 55% (11/20), and 70% (14/20) of isolates were resistant to gentamycin, amikacin, and levofloxacin, respectively.

Table 1.

Isolation of CPE from food samples in the markets of Yangon, Myanmar. ECC, E. cloacae complex; Sm, S. marcescens.

| Source | No. of samples | No. of CPE-positive samples (%) | No. of Isolates | Species (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 2 | E. coli |

| Chicken | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 3 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, ECC |

| Mutton | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 | ECC |

| Pork | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 2 | E. coli |

| Clam | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 1 | E. coli |

| Fish | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 | ECC |

| Squid | 8 | 0 (0) | 0 | − |

| Prawn | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 | K. pneumoniae |

| Chinese cabbage | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 4 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, ECC, Sm |

| Lettuce | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 | E. coli |

| Roselle | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 3 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, ECC |

| Water spinach | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 8 | E. coli (4), K. pneumoniae (2), ECC (2) |

| Total | 93 | 20 (21.5) | 27 |

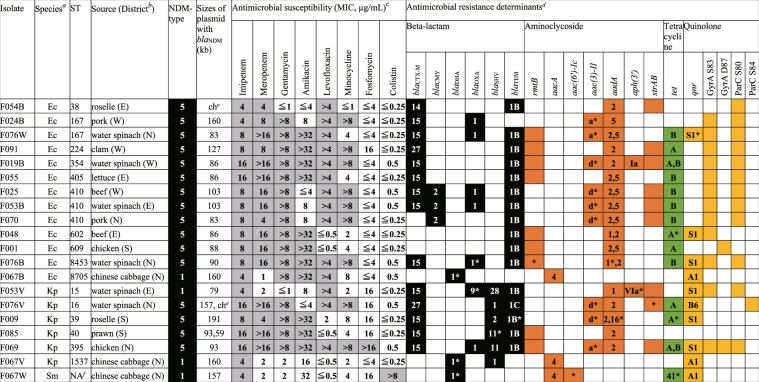

Figure 1.

Phenotypic and genetic characteristics of CPE isolates harbouring blaNDM. aEc, Escherichia coli; Kp, Klebsiella pneumoniae; Sm, Serratia marcescens. bFood samples were obtained from southern (S), western (W), eastern (E), and northern (N) districts of Yangon. cGrey cells indicate isolates resistant to the indicated antimicrobials. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration. dNumbers and alphabets in columns denote variant types. For GyrA and ParC, presence of amino acid substitution in the indicated residues are marked in dark yellow. Genes with nucleotide substitution(s) compared with sequences in the ResFinder database are marked with asterisks. eSouthern blots identified blaNDM-5 gene on chromosomes. fNA, not applicable.

Resistant isolates possessed multiple genes encoding aminoglycoside modification enzymes, chromosomal point mutation in quinolone-resistance-determining regions of gyrA and parC, as well as plasmid-mediated quinolone-resistance determinants. Notably, we found the 16S rRNA methylase gene rmtB in nine isolates resistant to gentamycin and amikacin. In contrast, all isolates except one were susceptible to fosfomycin and colistin. The only isolate resistant to the latter antibiotic was classified as Serratia, known to be intrinsically colistin-resistant11. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) classified 13 E. coli isolates into 10 sequence types (STs) and six K. pneumoniae isolates each into a different ST (Fig. 1). Further evidence of isolate diversity includes blaNDM presence in differently sized plasmids or chromosomes (Fig. 1).

Carbapenemase-producing E. cloacae complex possesses blaIMI-1

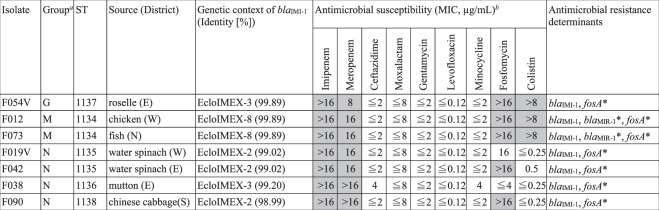

Using the carbapenem-inactivation method (CIM), we identified seven carbapenemase-positive isolates of Enterobacter cloacae complex that are negative for blaNDM, blaKPC, blaIMP, or blaOXA-48 according to a PCR-dipstick test. Instead, whole genome sequencing revealed that they all possessed blaIMI-1, a chromosomally encoded Ambler class A serine β-lactamase gene. In accordance with an earlier report12, blaIMI-1 presence conferred high resistance to imipenem and meropenem, but not to extended-spectrum cephalosporin and oxacephem antibiotics, such as ceftazidime and moxalactam (Fig. 2). These bacteria were also susceptible to gentamycin, minocycline, and levofloxacin. Five isolates out of seven were resistant to fosfomycin, and three were resistant to colistin, a last-resort antibiotic for treating CPE infections.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic and genetic characteristics of E. cloacae complex isolates harbouring blaIMI-1. aPhylogenetic groups were classified according to Chavda et al.13. bIsolates resistant to the indicated antimicrobials are represented as grey shaded cells. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration. *Genes with nucleotide substitutions compared with sequences in ResFinder.

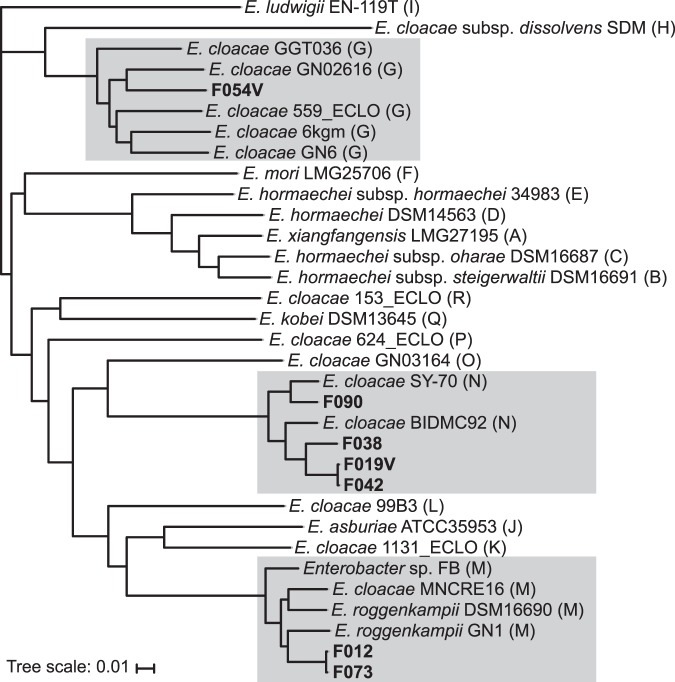

These six isolates were newly assigned to five STs representing previously undetected populations. We used whole-genome sequencing data of these isolates and those from the GenBank database to generate a core-genome single-nucleotide-polymorphism-based phylogenetic tree of the E. cloacae complex (Fig. 3). This tree grouped the newly assigned isolates into three clusters (G, M, and N)13. Each isolate carried blaIMI-1 between setB and yeiP; the gene was encoded on an integrative mobile element designated as EcloIMEX14. We identified three mobile elements, EcloIMEX-2 (GenBank accession number KR057494.1), -3 (KU870977.1), and -8 (MG547711.1). Of these, EcloIMEX-3 was found in phylogenetically different isolates, F038 and F054V.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis based on core-genome SNPs separates market-food-derived IMI-1-producing isolates into groups G, M, and N of the E. cloacae complex. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the genome of E. cloacae ATCC13047 (GenBank accession number NC_014121.1) as a reference. Genomic sequences of other E. cloacae complex strains were retrieved from NCBI and included in the analysis. The food isolates acquired in this study are in bold; strains belonging to groups G, M, and N are marked in grey.

Discussion

This study found diverse CPE in local market foods with higher isolation rates than previously reported (2.4%)8. Vegetables were the most contaminated, exhibiting the highest CPE-positive rate (28.1%) and containing approximately 60% of isolates identified. Following vegetables, meat samples had high isolation rates (25.0%).

Carbapenem-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates exhibited multidrug resistance because they harboured blaNDM-1 or blaNDM-5, along with other antimicrobial-resistance determinants. Worryingly, most isolates possessed blaNDM-5, which confers higher resistance against carbapenems than blaNDM-115. Furthermore, we found evidence that E. coli isolates harbouring blaNDM have clinical links; five of the 10 STs identified had been previously detected in a tertiary-care hospital of Yangon10. In contrast, NDM-producing K. pneumoniae isolates belonged to STs that have not been detected thus far from Yangon clinical specimens, although four (ST15, 16, 39, 395) have been found in clinical isolates from other countries16,17. Notably, we identified isolate F069 in chicken and showed that it was resistant to all tested antibiotics except colistin. This strain belongs to ST395, a constituent of worldwide epidemic clonal group 25818.

Isolation of IMI-type carbapenemase is relatively rare. Here, we provided valuable empirical evidence of diverse IMI-producing E. cloacae complexes existing outside hospitals, confirming previous long-term clinical observations that suggested that these bacteria are present in local communities14,19. Moreover, we confirmed the presence of IMI-type carbapenemase in Myanmar, suspected ever since blaIMI-2 was detected in a Dutch individual travelling to the country20.

We linked blaIMI-1 to a putative mobile element EcloIMEX in all isolates containing the gene. Among the three EcloIMEX detected, EcloIMEX-3 was found in genetically different group N (F038) and G (F054V) isolates, suggesting independent acquisition of the element. Thus, EcloIMEX is probably responsible for mobilizing blaIMI-type genes to E. cloacae complex14,19.

We isolated a blaIMI-1-harbouring E. coloacae complex from fish and water spinach, which is usually cultivated in water-rich regions, corroborating previous reports that associated these bacteria with aquatic environments6,21,22. Of note, we isolated two water spinach isolates of the same ST and EcloIMEX type from different districts, suggesting the existence of a shared reservoir of blaIMI-1 dissemination. Other sources are also likely, given the presence of blaIMI-1-harbouring isolates in other vegetables, as well as chicken and mutton, across all four surveyed districts.

Overall, our results demonstrate widespread dissemination of blaIMI-1-harbouring E. coloacae complex in Yangon. These organisms are susceptible to several common antibiotics, meaning that multiple treatment options are available in the event of infection such as reported previously23,24. However, they may sporadically become more resistant to drugs through acquiring multidrug-resistance plasmids in local communities. We therefore strongly recommend vigorous countermeasures to prevent pathogen spread through daily consumption of food stuffs in regions heavily contaminated by CPE and other multidrug-resistant microbes.

In conclusion, this study provided evidence that local market foods in Yangon, Myanmar frequently harboured diverse CPE isolates, some with highly drug-resistant phenotypes. We note two important limitations of our study: the small sample size and the possible existence of multiple sources for CPE spread. These factors prevented us from tracking exact CPE dissemination profiles in market food samples. Thus, further study is necessary to fully understand the extent of CPE dissemination in this region and to identify the major source(s) of their spread. Such knowledge will enable the development of effective countermeasures against contamination of food with CPE. Nevertheless, our research highlights the immediate need to take corrective action against the current situation of CPE contamination in food.

Methods

Isolation of carbapenemase-producing organisms from market food

Food sampling and bacterial isolation were conducted as previously described25. From November to December 2017, chicken, pork, beef, fish, clam, and assorted vegetables were collected from eight street stalls in Yangon. Samples were placed in an ice box and transported to the laboratory at the Department of Medical Research, Yangon, where they were either examined immediately or stored at 4 °C until further analysis. For sample processing, 25 g of flesh was mixed with 225 mL buffered peptone water in a stomacher bag and incubated at 35 °C for 18 ± 2 h. Subsequently, a loopful of enrichment culture was streaked onto CHROMagar ECC (CHROMagar, Paris, France), supplemented with 0.25 μg/mL meropenem and 70 μg/mL ZnSO426, then cultured at 35 °C for 24 ± 2 h.

Bacterial identification, antimicrobial-susceptibility tests, and PCR for carbapenemase genes

Bacteria were identified with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics, Germany). Antimicrobial susceptibility was measured using a MicroScan WalkAway 96 Plus (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and dry plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), then classified based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guidelines (M100-S24). For colistin, resistance was defined according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing criteria. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates were screened for carbapenemase production using CIM27. In addition, PCR-dipstick chromatography was performed to detect four major carbapenemase genes (blaNDM, blaKPC, blaIMP, and blaOXA-48)28.

Whole-genome sequencing and plasmid analysis

Bacterial isolates were cultured overnight in brain-heart infusion broth (BD Bacto, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 0.25 μg/mL meropenem. Genomic DNA was then prepared using a PowerSoil DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Library preparation was performed as described previously9 or using KAPA Hyper Plus Kits (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA, USA). Paired-end sequencing with 250 bp reads was performed in MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Reads were then de novo-assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench 11.0.1 (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark) for subsequent analyses.

Multilocus sequence typing for E. coli and K. pneumoniae were performed using EnteroBase (http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/) and the Institute Pasteur’s MLST database (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html), respectively. Existing methods29 were followed for MLST of the E. cloacae complex. Resistance-gene identification was performed in ResFinder 2.130. Evolutionary relatedness of isolates was assessed using CSI Phylogeny 1.431, and iTOL was used to construct the phylogenetic tree32. To classify EcloIMEX, local BLAST searches were performed on sequences around blaIMI-1, which contain setB and yeiP genes.

To determine the blaNDM-harbouring plasmid size, pulsed-field electrophoresis (PFGE) plugs prepared from isolates were treated with S1 nuclease (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and subjected to PFGE in the CHEF Mapper XA system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Separated DNA was then transferred to a nylon membrane and probed with a digoxigenin-labelled (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), blaNDM-specific DNA probe for Southern hybridization.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the NGS core facility of the Genome Information Research Center at the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University for their support during DNA sequencing. We are grateful to Dr. Ryuji Kawahara for his helpful comments on bacterial isolation from food. We thank Yumi Sasaki and Kazuhiro Maeda for their technical assistance during antimicrobial susceptibility testing. This work was supported by the Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases (J-GRID) from Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Author Contributions

H.H., Y.A., M.M.A., M.M.H., K.T. and S.H. conceived and designed this study. H.H., M.M.A. and H.P.M.W. collected and phenotypically characterised the bacterial isolates. Y.S., H.H., N.S., R.K.S. and D.T. performed screening for carbapenemase genes and whole genome sequencing. I.N. and U.A. conducted bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Y.S. analysed the sequence data. Y.S., H.H., Y.A. and S.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approve of the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The sequence data were submitted to the DDBJ/GenBank/ENA database under BioProject number PRJDB5126.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yo Sugawara and Hideharu Hagiya contributed equally.

References

- 1.Temkin E, Adler A, Lerner A, Carmeli Y. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: biology, epidemiology, and management. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014;1323:22–42. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonomo RA, et al. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:1290–1297. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, Toleman MA. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:355–362. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam MA, et al. Environmental spread of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1-producing multidrug-resistant bacteria in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e00793–17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00793-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zurfluh K, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Klumpp J, Stephan R. First detection of Klebsiella variicola producing OXA-181 carbapenemase in fresh vegetable imported from Asia to Switzerland. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2015;4:38. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0080-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janecko N, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter spp. in retail seafood imported from Southeast Asia to Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:1675–1677. doi: 10.3201/eid2209.160305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:16260. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu BT, et al. Characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in ready-to-eat vegetables in China. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1147. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugawara Y, et al. Genetic characterization of blaNDM-harboring plasmids in carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli from Myanmar. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugawara Y, et al. Spreading patterns of NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae in clinical and environmental settings in Yangon, Myanmar. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e01924–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01924-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gales AC, Jones RN, Sader HS. Global assessment of the antimicrobial activity of polymyxin B against 54 731 clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacilli: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme (2001-2004) Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006;12:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen BA, et al. Characterization of IMI-1 beta-lactamase, a class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme from Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2080–2086. doi: 10.1128/AAC.40.9.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chavda KD, et al. Comprehensive genome analysis of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter spp.: new insights into phylogeny, population structure, and resistance mechanisms. MBio. 2016;7:e02093–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02093-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd DA, et al. Enterobacter cloacae complex isolates harboring blaNMC-A or blaIMI-type class A carbapenemase genes on novel chromosomal integrative elements and plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02578–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02578-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornsey M, Phee L, Wareham DW. A novel variant, NDM-5, of the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST648 isolate recovered from a patient in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5952–5954. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05108-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4178–4182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potron A, Kalpoe J, Poirel L, Nordmann P. European dissemination of a single OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clone. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:E24–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyres KL, et al. Extensive capsule locus variation and large-scale genomic recombination within the Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal group 258. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015;7:1267–1279. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh TH, et al. Putative integrative mobile elements that exploit the Xer recombination machinery carrying blaIMI-type carbapenemase genes in Enterobacter cloacae complex isolates in Singapore. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01542–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01542-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Hattem JM, et al. Prolonged carriage and potential onward transmission of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Dutch travelers. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:857–864. doi: 10.2217/fmb.16.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aubron C, Poirel L, Ash RJ, Nordmann P. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, U.S. rivers. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:260–264. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brouwer MSM, et al. Enterobacter cloacae complex isolated from shrimps from Vietnam carrying blaIMI-1 resistant to carbapenems but not cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e00398–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00398-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naas T, Cattoen C, Bernusset S, Cuzon G, Nordmann P. First identification of blaIMI-1 in an Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate from France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1664–1665. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teo JW, et al. Enterobacter cloacae producing an uncommon class A carbapenemase, IMI-1, from Singapore. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;62:1086–1088. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.053363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le QP, et al. Characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in retail meats and shrimp at a local market in Vietnam. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:719–725. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2015.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto N, et al. Development of selective medium for IMP-type carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in stool specimens. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17:229. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2312-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Zwaluw K, et al. The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), a simple and low-cost alternative for the Carba NP test to assess phenotypic carbapenemase activity in gram-negative rods. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanmugakani RK, et al. PCR-Dipstick chromatography for differential detection of carbapenemase genes directly in stool specimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00067–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00067-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for characterization of Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaas RS, Leekitcharoenphon P, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. Solving the problem of comparing whole bacterial genomes across different sequencing platforms. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:127–128. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data were submitted to the DDBJ/GenBank/ENA database under BioProject number PRJDB5126.