Abstract

Background

Substantial efforts are required to limit global warming to under 2 °C, with 1.5 °C as the target (Paris Agreement goal). We set out to project future temperature-related myocardial infarction (MI) events in Augsburg, Germany, at increases in warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C.

Methods

Using daily time series of MI cases and temperature projections under two climate scenarios, we projected changes in temperature-related MIs at different increases in warming, assuming no changes in population structure or level of adaptation.

Results

In a low-emission scenario that limits warming to below 2 °C throughout the 21st century, temperature-related MI cases will decrease slightly by –6 (confidence interval -60; 50) per decade at 1.5 °C of warming. In a high-emission scenario going beyond the Paris Agreement goals, temperature-related MI cases will increase by 18 (-64; 117) and 63 (-83; 257) per decade with warming of 2 °C and 3 °C, respectively.

Conclusion

The future burden of temperature-related MI events in Augsburg at 2 °C and 3 °C of warming will be greater than at 1.5 °C. Fulfilling the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to no more than 1.5 °C is therefore essential to avoid additional MI events due to climate change.

Climate change is the biggest global health threat, and tackling it could be the greatest global health opportunity of the 21st century (1). To reduce the health risks of climate change, in 2015 the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted the Paris Agreement, which aims at holding global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C (2). However, little is known about the difference in health impacts between the 1.5 °C and 2 °C warming targets (3, 4). Although emerging evidence from regional, national, and global studies shows a potential increase in temperature-related mortality as a result of climate change (5– 9), nearly all these studies have focused on a certain future period but not on a specific warming target (3). Thus, it remains unclear whether limiting global warming to 1.5 °C instead of 2 °C will avoid temperature-related health impacts (3, 10).

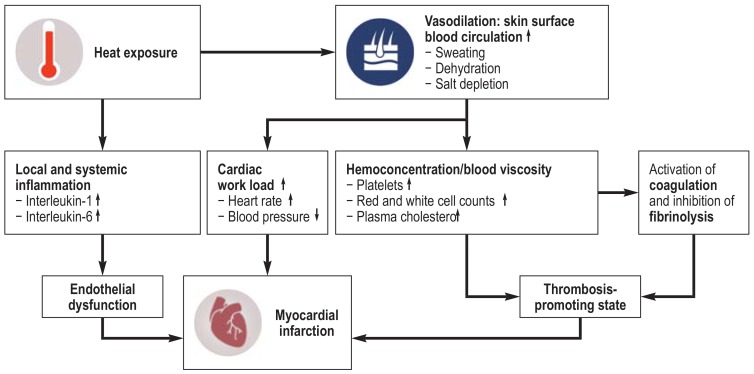

In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C (SR15) and concluded with very high confidence that heat-related health impacts will be greater at 2 °C of warming than at 1.5 °C (11). However, cold-related mortality is projected to decrease with warming winters in some regions (11), and it remains unclear to which extent heat-related impacts may offset this decrease, leading to an uncertain overall impact of temperature on health (12). Moreover, most of the previous projection studies have focused on mortality rather than morbidity (13), leading to limited evidence regarding climate change impacts on heat-related morbidity. Cold exposure has been reported as a trigger of MI events (14), and a recent study of ours found that heat exposure is also a potential trigger (15). Plausible pathophysiological mechanisms are shown in Figure 1. In the study described here, we aimed to project future temperature-related myocardial infarction (MI) events in Augsburg, Germany, at levels of warming consistent with the Paris Agreement goals (1.5 °C and 2 °C) and higher (3 °C). This information may help health professionals and policy makers to better understand the potential health threat of climate change.

Figure 1.

Plausible pathophysiological mechanisms linking heat exposure to myocardial infarction.

Heat exposure may lead to the onset of myocardial infarction through:

– Vasodilation and increased surface blood circulation, which may increase cardiac work load and result in hemoconcentration and thrombosis promotion

– Release of interleukins that cause local and systemic inflammation and result in endothelial dysfunction (25, 26).

↑, Increasing; ↓, decreasing

Methods

Study population

We used data from the population-based Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) MI registry. The study area comprises the city of Augsburg and the two adjacent counties (Augsburg and Aichach-Friedberg). All recorded cases of MI and coronary deaths among residents aged 25 to 74 years (about 400,000 inhabitants) from 1 January 2001, to 31 December 2014 were included in analysis. We also evaluated subtypes of MI events, including ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) and non-ST segment elevation MI (NSTEMI). Details of this registry are given in the eMethods. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Bavarian Chamber of Physicians and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Temperature projections

We obtained daily mean temperatures for the period 2010 to 2099 from four global climate models under the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project Phase 2b (ISIMIP2b) (16). We used two climate change scenarios under the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP), RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, corresponding to low and high warming and emissions, respectively (Box 2). We applied the method described in Ebi et al. (2018) (3) to determine the decade in which 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C of warming above pre-industrial levels will be reached, using the decade 2010 to 2019 as baseline (eMethods).

Key Messages.

Any increase in global warming will increase heat-related MIs but decrease cold-related MIs.

The net temperature impact on MI will remain largely unchanged in a low-emission scenario limiting global warming to 1.5 °C.

In a high-emission scenario (“business as usual”), the number of temperature-related MIs will increase when global warming reaches 2 °C or 3 °C.

Failure to meet the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 °C will result in a substantial increase in temperature-related MIs, especially for NSTEMI events.

Health impact assessment

We estimated the number and fraction of MI cases attributable to heat, cold, and net change (the summed impacts of heat and cold) for different levels of warming based on the assumption of no changes in population structure or level of adaptation, using a recently developed approach (17). Briefly, we used the previously estimated exposure–response functions between daily mean temperature and daily MI events (eFigure 1) (15), the temperature projections, and baseline MI cases to calculate the daily attributable number of MI events. The baseline MI cases were calculated as the average observed number of cases for each day of the year during the period 2001 to 2014. Finally, we computed the future changes as the differences between the future decades in which different levels of warming will be reached and the baseline period for each RCP. We used Monte Carlo simulations to estimate empirical confidence intervals (eCI) to address the uncertainty in exposure–response functions and the variability across global climate models. Key elements in the assessment are provided in the eBox. Details of the health impact assessment can be found in the eMethods.

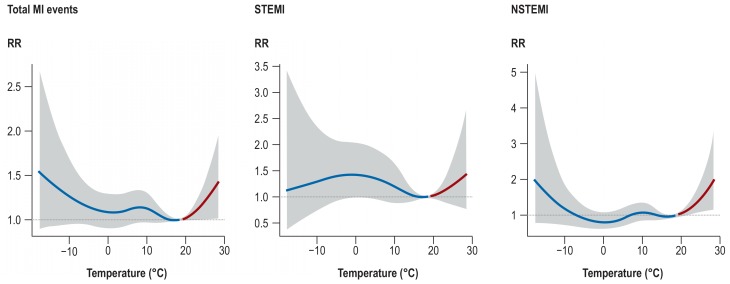

eFigure.

Cumulative exposure–response functions between air temperature and myocardial infarction (with 95% confidence intervals) in Augsburg, Germany in the period 2001 to 2014. The exposure–response functions were obtained from Chen et al. (2019) (15). The red lines represent the effect of heat (temperature above 18.4 °C), while the blue lines show the effect of cold (temperature below 18.4 °C).

eBOX. Key elements in the assessment of climate change impact.

The exposure–response curves were obtained from a previous study (15).

We assume a constant population (size, age structure, and lifestyle).

We assume constant incidence for the total number and subtypes of MI.

The temperature projections for the Augsburg region were obtained from four global climate models based on two <<Autor: Sie schrieben “3">> different climate change scenarios.

Sources of potential uncertainty regarding the projections includes the uncertainty of exposure–response curves and the variability across the four climate models.

Results

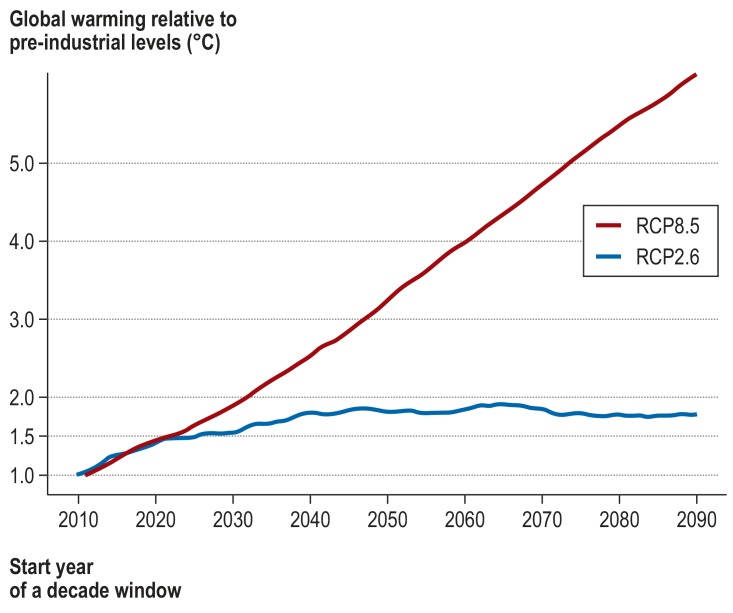

Figure 2 shows the 10-year moving global mean temperature projections from the average of four global climate models in two RCP scenarios relative to pre-industrial levels. Global mean temperature in RCP8.5 exceeds 3 °C relative to pre-industrial levels by the end of the 21st century, whereas it remains below 2 °C in RCP2.6. Thus, we used RCP2.6 for the scenario fulfilling the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 °C and RCP8.5 for warming of 2 °C and 3 °C. Based on these scenarios, warming of 1.5 °C will be reached around 2031 (table 1). Warming of 2 °C and 3 °C will be reached around 2037 and 2052, respectively.

Figure 2.

Time-series of the moving average of change in annual global mean near-surface air temperature over a period of 10 years relative to pre-industrial levels in different climate scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathway, RCP; see Box). RCP8.5 assumes no further measures to reduce emissions; RCP2.6 aims at limiting global warming to less than 2 °C. The x-axis shows the start year of a 10-year moving average.

Table 1. Scenarios for global warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C.

| RCP | Decade | Global warming |

| RCP2.6 | 2031 ± 5 years | 1.5°C |

| RCP8.5 | 2037 ± 5 years | 2°C |

| RCP8.5 | 2052 ± 5 years | 3°C |

RCP, Representative Concentration Pathway: a greenhouse gas concentration trajectory that reflects the effect of greenhouse gases and aerosols on the energybalance of the earth. RCP2.6 aims to keep global warming below 2 °C; RCP8.5 assumes no additional mitigation efforts to reduce emissions (“business-as-usual” scenario).

From 2001 to 2014, there were on average 967 coronary events per year, of which 235 were STEMI and 331 were NSTEMI. Relative to the baseline period, heat-related MIs will increase in all warming scenarios, whereas cold-related MIs will decrease (table 2). If the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5 °C is met, temperature-related MI cases per decade in Augsburg will decrease slightly overall (–6 [-60; 50]). Warming of 2 °C yields larger increases in heat-related MIs than reductions in cold-related MIs, leading to a net increase of 18 [-64; 117] MI cases per decade. At 3 °C of warming, beyond the Paris Agreement target, temperature-related MIs are projected to increase by 63 [-83; 257] per decade, which corresponds to an increase of about 0.7% in the burden of MI events.

Table 2. Changes in attributable number and fraction (95% eCI)* of temperature-related MI cases per decade in Augsburg assuming global warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C.

| Global warming | Attributable number | Attributable fraction (%) | ||||

| Heat | Cold | Net change | Heat | Cold | Net change | |

| 1.5 °C | 17 [−1; 46] | −24 [−87; 32] | −6 [−60; 50] | 0.2 [0; 0.5] | −0.2 [−0.9; 0.3] | −0.1 [−0.6; 0.5] |

| 2 °C | 54 [1; 124] | −36 [−101; 43] | 18 [−64; 117] | 0.6 [0; 1.3] | −0.4 [−1.0; 0.4] | 0.2 [−0.7; 1.2] |

| 3 °C | 109 [4; 313] | −46 [−142; 56] | 63 [−83; 257] | 1.1 [0; 3.2] | −0.5 [−1.5; 0.6] | 0.7 [−0.9; 2.7] |

*The 95% eCI (empirical confidence interval) was obtained by considering the uncertainty of concentration–response function using 5000 Monte Carlo simulations and four global climate models.

Explanation: Global warming of 2 °C, for example, is associated with 54 additional heat-related events and 36 fewer cold-related events, resulting in a net change of 18 additional temperature-related events per decade. Thus, 0.2% of all MI cases can be attributed to global warming.

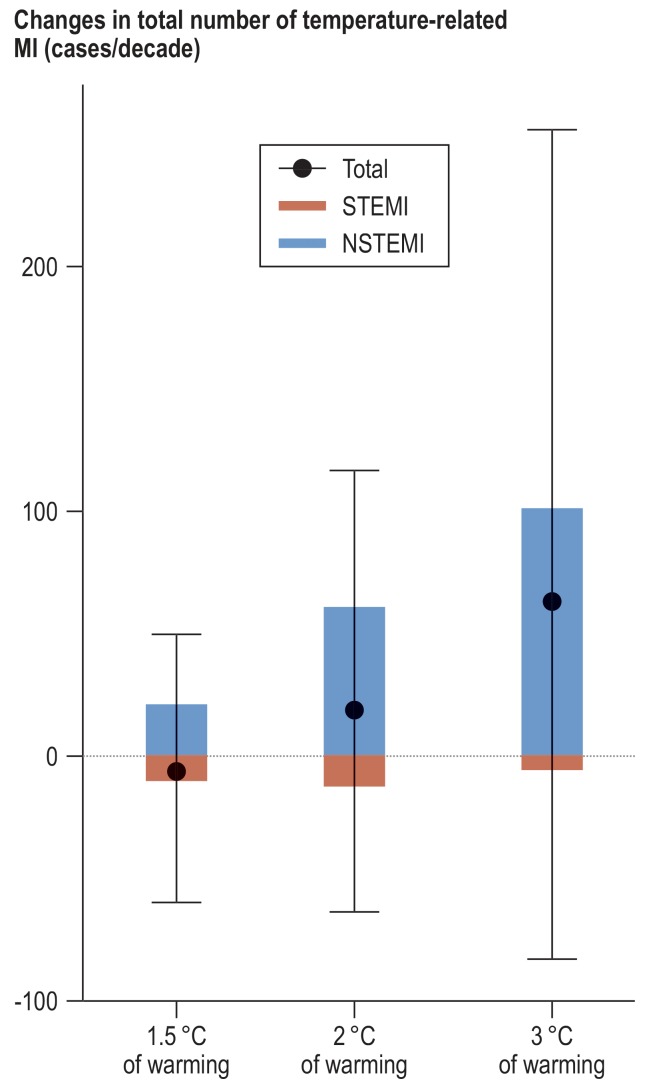

Figure 3 summarizes the net changes in temperature-related MIs in the different warming scenarios overall and for the subtypes of MI. Total and NSTEMI events are generally projected to increase with increasing level of warming. Conversely, STEMI events are projected to decrease because the decrease in cold-related cases will exceed the rise in heat-related events. Most of the increased temperature-related MIs will be NSTEMI events, with the increase ranging from 21 [-13: 63] at 1.5 °C of warming to 102 [21; 201] at 3 °C of warming.

Figure 3.

Changes in temperature-related MI cases per decade projected for 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C of warming by MI type. Red and blue bars represent changes in the temperature-related number of STEMI and NSTEMI events in future decades relative to 2010–2019. Black dots and vertical lines denote changes and 95% empirical confidence intervals in the temperature-related total number of MI events

Discussion

Our analyses show that all of our projected increases in global warming will increase heat-related MIs but reduce cold-related MIs in Augsburg, Germany. Holding warming to 1.5 °C instead of 2 °C or 3 °C will avoid a substantial number of temperature-related MIs. In the low-emission scenario RCP2.6, warming will be kept below 2 °C right up to 2100, resulting in a negligible net change in the number of MIs. In contrast, warming will exceed 3 °C by 2100 in the high-emission scenario RCP8.5, leading to a considerable increase in the burden of MIs.

Very few studies have directly estimated the regional health impacts of stabilizing climate warming at 1.5 °C instead of 2 °C (3). Our finding of greater heat-related impacts for warming at 2 °C than at 1.5 °C is consistent with the conclusion of IPCC Special Report 15 (11) and the findings of two recent multicenter European studies (10, 12). We also found a much lower total number of heat-related total MIs at 2 °C than at 3 °C in Augsburg for the high-emission scenario RCP8.5. A recent worldwide study found a net increase in temperature-related mortality in central and southern European cities (12), suggesting that emission reductions in line with the Paris Agreement goals can avoid heat-related impacts on MI burden.

The climate scenario RCP2.6 meets the Paris Agreement target of keeping warming well below 2 °C (Figure 1, Table 1), confirming a previous review (3), and yields a negligible change (-0.1%) in MI burden if warming is limited to 1.5 °C. In comparison, temperature-related MIs in scenario RCP8.5 will increase by 0.2% at 2 °C of warming and by 0.7% at 3 °C of warming (table 2). Similarly, a previous study also estimated a much smaller temperature-related mortality burden for RCP2.6 than for RCP8.5 in central and southern European cities over the course of the 21st century (5).

According to the Federal Statistical Office, 135 218 MI events occurred in patients aged between 25 and 74 years in Germany in 2015 (including both acute MI and deaths from cardiac arrest) (18). Assuming our projected changes in attributable fractions in the Augsburg region could be applied to the whole of Germany, a rough calculation shows that holding warming at 1.5 °C, compared with 3 °C, would prevent 1 082 MI cases each year. This is likely to be an underestimate, as we only considered patients aged below 75, whereas the elderly have been demonstrated to be more vulnerable to heat-related mortality and morbidity (19, 20). Our findings suggest that ambitious greenhouse gas emission reductions are required to achieve the Paris Agreement targets and to prevent adverse temperature-related health impacts.

Implications for healthcare professionals

Healthcare professionals have vital roles in accelerating progress to tackle climate change. They are trained to educate patients about health threats, may be trusted more than environmentalists, and can better communicate the health risks posed by climate change and thus potentially also convince politicians that emissions of greenhouse gases must be reduced (1, 21). With the ability to effectively highlight the associated health threats, healthcare professionals should be at the forefront of the battle against climate change (22). To encourage primary care physicians and other health professionals to lead on tackling climate change, it is important to understand how climate change can impact health outcomes (23). The results of this study suggests that global warming higher than 1.5 °C will lead to increasing temperature-related MI cases. We therefore appeal to healthcare professionals to inform the public and policymakers about the potential health threats of climate change and the benefits of climate protection measures.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study project the effects on heat-related MIs of global temperature increases below and above the goals set by the Paris Agreement. Our estimates are based on a validated, complete, and detailed registration of all MIs and coronary deaths in Augsburg, in combination with an established advanced approach to account for uncertainty in exposure–response functions and variability across climate models (5). Our estimates can be interpreted as the changes in heat-related MI events if the current Augsburg population were exposed to future temperatures resulting from global warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C. Thus, our projections allow isolation of the effects of a changing climate from other factors such as demographic change and population adaptation (5).

Our study has several limitations. First, our projections of the health impacts focus on specific Paris Agreement targets rather than consistent future periods. This approach uses different periods for different warming targets, which limits our ability to consider impacts of future population changes such as size, age structure, lifestyle, and underlying MI rates. As we expect more NSTEMI events but fewer STEMI events in Augsburg in the future (15), the future changes in total temperature-related MI burden may be underestimated. Moreover, the temperature projections we used have a relatively coarse spatial resolution (˜ 50 km). Future studies using higher resolution temperature projections, such as those from COSMO-CLM developed by the German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst), are needed to enable estimation of the regional health impact of climate change. Furthermore, we did not consider population adaptation to heat (24). However, heat-related vulnerability may further increase in Augsburg (15), resulting in increased future temperature-related impacts.

Conclusion

The higher the increase in global temperature (1.5 °C, 2 °C, or 3 °C), the greater will be the burden of temperature-related MIs in Augsburg, Germany. Compared with inaction on climate change in a high-emission scenario, limiting global warming to 1.5 °C in a low-emission scenario will avoid additional MI events, suggesting that climate change mitigation policies are needed to fulfill the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 °C.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Study population

Our research was based on data from the population-based Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) MI registry. The Augsburg region includes the city of Augsburg (with an area of 147 km2) and the two adjacent rural districts Augsburg and Aichach-Friedberg (1,854 km2). The MONICA/KORA MI registry was founded in 1984 as part of the WHO MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) project and since 1996 has been continued as part of the KORA research program. Since 1984, all cases of MI in eight hospitals in the study area and coronary deaths occurring among residents aged 25 to 74 years old (about 400,000 inhabitants) have been documented in the MONICA/KORA MI registry. In addition, all cases of fatal MI including sudden cardiac death are recorded. Following the MONICA protocol, MI patients who survive at least 24 hours after hospitalization are questioned about the event, demographic information, comorbidities, medication, and family history. If a patient survives the 28th day after hospital admission, the MI is identified as nonfatal, otherwise as fatal. Coronary fatalities are deaths outside the hospital setting or within 24 hours after admission to a hospital. All coronary deaths (ICD-9 codes: 410–414) were identified through checks of all death certificates by the regional health departments and on the basis of information from the last treating physician and/or coroner.

In this study, we investigated all recorded cases of MI and coronary deaths among residents aged 25 to 74 years between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2014. We further analyzed subtypes of MI events, including ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) events. Bundle branch block was not included in this analysis due to its small sample size (38.6 cases/year). More details of the MONICA/KORA registry can be found elsewhere ((30, (31).

Exposure–response functions and baseline MI

We applied estimates of the exposure–response functions (ERFs) between daily mean temperature and daily MI events from our previous work for the period 2001 to 2014 (15). In that earlier research, we conducted a time-stratified case-crossover study and used a nonlinear distributed lag model with a maximum lag of 10 days to estimate the ERFs. Temperature and MI cases generally showed U-shaped associations, with a significantly increasing risk for heat (temperatures above the minimum MI temperature [MMIT; reference temperature, 18.4 °C]) but a nonsignificantly increasing risk for cold (temperatures below the MMIT) (eFigure 1). The baseline MI cases were calculated as the average observed number of cases for each day of the year during the period 2001 to 2014.

Temperature projections

We obtained daily mean temperature projections for the years 2010 to 2099 from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project Phase 2b (ISIMIP2b) (32). We used two climate change scenarios under the Representative Concentration Pathways RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, corresponding to low and high warming and emissions, respectively. We obtained daily temperature simulations at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° from all four global climate models (GCMs) included in ISIMIP2b (i.e., GFDL-ESM2M, HadGEM2-ES, IPSL-CM5A-LR, and MIROC5). These temperature simulations were bias-corrected based on the EWEMBI dataset (33). As in previous studies (5, 13), we obtained daily temperatures for the baseline and future periods by extracting the temperature projections in one grid cell that covers the geographical center of the Augsburg area.

To determine the period when 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C of warming above pre-industrial levels will be reached, we applied the method described in Ebi et al. (2018) (3) in support of the IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C. We first defined the baseline period as the decade 2010 to 2019, because its center year 2015 was the first year in which warming of 1 °C above pre-industrial levels (defined as the average between 1850 and 1900) was attained (3). We then created a series of 10-year moving average projection windows, starting from the decade 2011 to 2020, with 1-year steps. We thus selected decade windows for each RCP when the GCM-ensemble average of global mean near-surface air temperature reached 0.5 °C, 1 °C, and 2 °C above the 2010 to 2019 baseline.

Health impact assessment

We estimated the number and fraction of MI cases attributable to heat, cold, and net change (the summed impacts of heat and cold) under the assumption of no future changes in population and adaptation, using a recently developed approach (17). Briefly, we applied the previously estimated ERFs (15) and the modeled daily series of temperature and MI cases to calculate the daily attributable number of MI cases. We then calculated the total attributable number by summing the contributions from all the days of the series and calculated the attributable fraction as the ratio of the total attributable number to the total number of MI cases. Finally, we computed the future changes as the differences between the future periods and the baseline period for each GCM and each RCP.

We computed the GCM-ensemble average total attributable number and fractions of MI cases by combinations of RCPs and future periods corresponding to warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C. We used Monte Carlo simulations to estimate empirical confidence intervals (eCI) to address the uncertainty in ERF and the variability across GCMs. We obtained eCI from the empirical distribution across 5,000 samples of random parameter sets that describe the ERF in the distributed lag nonlinear model and the four GCMs, as described in more detail elsewhere (5, 17). Briefly, we quantified the uncertainty in ERF by using Monte Carlo simulations to generate 5,000 samples for the estimated coefficients from the distributed lag nonlinear model which estimated the ERF. We then generated results for each of the four GCMs. We obtained the 95% eCI, defined as the 2.5 to 97.5 percentiles of empirical distribution across ERF coefficients and GCMs. Thus, the 95% eCI account for both the ERF and GCM sources of uncertainty.

BOX. Climate change scenarios.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) to describe different 21st century trajectories of greenhouse gas emissions and atmospheric concentrations, air pollution emissions, and land use (27). The numbers in the names of the RCPs correspond to different target levels of radiative forcing in 2100. Radiative forcing reflects the effect of greenhouse gases and aerosols on the Earth’s energy balance. Two RCPs were used in this study: a stringent emission mitigation scenario (RCP2.6) and a scenario with very high greenhouse gas emissions (RCP8.5).

- RCP2.6 aims to limit global warming to below 2 °C and requires substantial net negative emissions by 2100, with an average of about 2 Gt/year for CO2 emissions (28).

- RCP8.5 assumes no additional mitigation efforts to reduce emissions (or the so-called business-as-usual scenario), with average CO2 emissions of 73 Gt/year over the 21st century (29).

Relative to the period 1986 to 2005, global mean sea level rise in 2081 to 2100 will likely be 0.40 m and 0.63 m under RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, respectively.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

Kai Chen PhD acknowledges support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for the Humboldt Research Fellowship. The KORA research platform was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Technology and by the state of Bavaria. Since 2000, the MI data collection has been co-financed by the German Federal Ministry of Health and Social Security to provide population-based MI morbidity data for the official German Health Report (see www.gbe-bund.de).

References

- 1.Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet. 2015;386:1861–1914. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNFCC. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Report No FCCC/CP/2015/L9/Rev12015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebi KL, Hasegawa T, Hayes K, Monaghan A, Paz S, Berry P. Health risks of warming of 15. °C, 2 °C, and higher, above pre-industrial temperatures. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13 063007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shindell D, Faluvegi G, Seltzer K, Shindell C. Quantified, localized health benefits of accelerated carbon dioxide emissions reductions. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:291–295. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0108-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Sera F, et al. Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e360–e367. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberger KR, Haykin L, Eliot MN, Schwartz JD, Gasparrini A, Wellenius GA. Projected temperature-related deaths in ten large US. metropolitan areas under different climate change scenarios. Environ Int. 2017;107:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Horton RM, Bader DA, et al. Impact of climate change on heat-related mortality in Jiangsu Province, China. Environ Pollut. 2017;224:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y, Gasparrini A, Li S, et al. Quantifying excess deaths related to heatwaves under climate change scenarios: a multicountry time series modelling study. PLoS Med. 2018;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002629. e1002629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T, Horton RM, Kinney PL. Projections of seasonal patterns in temperature-related deaths for Manhattan, New York. Nat Clim Chang. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/nclimate1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell D, Heaviside C, Schaller N, et al. Extreme heat-related mortality avoided under Paris Agreement goals. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:551–553. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jacob D, Taylor M, et al. Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, et al., editors. Impacts of 15 °C global warming on natural and human systems Global warming of 15 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 15 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Guo Y, Sera F, et al. Temperature-related mortality impacts under and beyond Paris Agreement climate change scenarios. Clim Change. 2018;150:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s10584-018-2274-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinberger KR, Kirwa K, Eliot MN, Gold J, Suh HH, Wellenius GA. Projected changes in temperature-related morbidity and mortality in Southern New England. Epidemiology. 2018;29:473–481. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claeys MJ, Rajagopalan S, Nawrot TS, Brook RD. Climate and environmental triggers of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:955–960. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen K, Breitner S, Wolf K, et al. Temporal variations in the triggering of myocardial infarction by air temperature in Augsburg, Germany, 1987-2014. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1600–1608. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frieler K, Lange S, Piontek F, et al. Assessing the impacts of 15 °C global warming - simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP2b) Geosci Model Dev. 2017;10:4321–4345. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasparrini A, Leone M. Attributable risk from distributed lag models. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.German Federal Statistical Office. Diagnoses of hospital patients. www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/data (last accessed on 7 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality: a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environ Health. 2009;8 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell ML, O’Neill MS, Ranjit N, Borja-Aburto VH, Cifuentes LA, Gouveia NC. Vulnerability to heat-related mortality in Latin America: a case-crossover study in São Paulo, Brazil, Santiago, Chile and Mexico City, Mexico. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:796–804. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy D, Hoskins B. The science of anthropogenic climate change: what every doctor should know. BMJ. 2014;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5178. g5178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramanathan V, Haines A. Healthcare professionals must lead on climate change. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5245. i5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patz JA, Frumkin H, Holloway T, Vimont DJ, Haines A. Climate change: challenges and opportunities for global health. JAMA. 2014;312:1565–1580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petkova EP, Vink JK, Horton RM, et al. Towards more comprehensive projections of urban heat-related mortality: estimates for New York City under multiple population, adaptation, and climate scenarios. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:47–55. doi: 10.1289/EHP166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider A, Rückerl R, Breitner S, Wolf K, Peters A. Thermal control, weather, and aging. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2017;4:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s40572-017-0129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Breitner S, Pan X, et al. Associations between air temperature and cardio-respiratory mortality in the urban area of Beijing, China: a time-series analysis. Environ Health. 2011;10 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.IPCC. IPCC. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Climate Change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Vuuren DP, Stehfest E, den Elzen MGJ, et al. RCP2.6: exploring the possibility to keep global mean temperature increase below 2 °C. Clim Change. 2011;109:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riahi K, Rao S, Krey V, et al. RCP 85. —A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim Change. 2011;109:33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löwel H, Meisinger C, Heier M, Hörmann A. The population-based acute myocardial infarction (AMI) registry of the MONICA/KORA study region of Augsburg. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:31–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuch B, Heier M, Von Scheidt W, Kling B, Hoermann A, Meisinger C. 20-year trends in clinical characteristics, therapy and short-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction according to presenting electrocardiogram: the MONICA / KORA AMI Registry (1985-2004) J Intern Med. 2008;264:254–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frieler K, Lange S, Piontek F, et al. Assessing the impacts of 15 °C global warming - simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP2b) Geosci Model Dev. 2017;10:4321–4345. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lange S. Bias correction of surface downwelling longwave and shortwave radiation for the EWEMBI dataset. Earth Syst Dynam. 2018;9:627–645. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Study population

Our research was based on data from the population-based Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) MI registry. The Augsburg region includes the city of Augsburg (with an area of 147 km2) and the two adjacent rural districts Augsburg and Aichach-Friedberg (1,854 km2). The MONICA/KORA MI registry was founded in 1984 as part of the WHO MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) project and since 1996 has been continued as part of the KORA research program. Since 1984, all cases of MI in eight hospitals in the study area and coronary deaths occurring among residents aged 25 to 74 years old (about 400,000 inhabitants) have been documented in the MONICA/KORA MI registry. In addition, all cases of fatal MI including sudden cardiac death are recorded. Following the MONICA protocol, MI patients who survive at least 24 hours after hospitalization are questioned about the event, demographic information, comorbidities, medication, and family history. If a patient survives the 28th day after hospital admission, the MI is identified as nonfatal, otherwise as fatal. Coronary fatalities are deaths outside the hospital setting or within 24 hours after admission to a hospital. All coronary deaths (ICD-9 codes: 410–414) were identified through checks of all death certificates by the regional health departments and on the basis of information from the last treating physician and/or coroner.

In this study, we investigated all recorded cases of MI and coronary deaths among residents aged 25 to 74 years between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2014. We further analyzed subtypes of MI events, including ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) events. Bundle branch block was not included in this analysis due to its small sample size (38.6 cases/year). More details of the MONICA/KORA registry can be found elsewhere ((30, (31).

Exposure–response functions and baseline MI

We applied estimates of the exposure–response functions (ERFs) between daily mean temperature and daily MI events from our previous work for the period 2001 to 2014 (15). In that earlier research, we conducted a time-stratified case-crossover study and used a nonlinear distributed lag model with a maximum lag of 10 days to estimate the ERFs. Temperature and MI cases generally showed U-shaped associations, with a significantly increasing risk for heat (temperatures above the minimum MI temperature [MMIT; reference temperature, 18.4 °C]) but a nonsignificantly increasing risk for cold (temperatures below the MMIT) (eFigure 1). The baseline MI cases were calculated as the average observed number of cases for each day of the year during the period 2001 to 2014.

Temperature projections

We obtained daily mean temperature projections for the years 2010 to 2099 from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project Phase 2b (ISIMIP2b) (32). We used two climate change scenarios under the Representative Concentration Pathways RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, corresponding to low and high warming and emissions, respectively. We obtained daily temperature simulations at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° from all four global climate models (GCMs) included in ISIMIP2b (i.e., GFDL-ESM2M, HadGEM2-ES, IPSL-CM5A-LR, and MIROC5). These temperature simulations were bias-corrected based on the EWEMBI dataset (33). As in previous studies (5, 13), we obtained daily temperatures for the baseline and future periods by extracting the temperature projections in one grid cell that covers the geographical center of the Augsburg area.

To determine the period when 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C of warming above pre-industrial levels will be reached, we applied the method described in Ebi et al. (2018) (3) in support of the IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C. We first defined the baseline period as the decade 2010 to 2019, because its center year 2015 was the first year in which warming of 1 °C above pre-industrial levels (defined as the average between 1850 and 1900) was attained (3). We then created a series of 10-year moving average projection windows, starting from the decade 2011 to 2020, with 1-year steps. We thus selected decade windows for each RCP when the GCM-ensemble average of global mean near-surface air temperature reached 0.5 °C, 1 °C, and 2 °C above the 2010 to 2019 baseline.

Health impact assessment

We estimated the number and fraction of MI cases attributable to heat, cold, and net change (the summed impacts of heat and cold) under the assumption of no future changes in population and adaptation, using a recently developed approach (17). Briefly, we applied the previously estimated ERFs (15) and the modeled daily series of temperature and MI cases to calculate the daily attributable number of MI cases. We then calculated the total attributable number by summing the contributions from all the days of the series and calculated the attributable fraction as the ratio of the total attributable number to the total number of MI cases. Finally, we computed the future changes as the differences between the future periods and the baseline period for each GCM and each RCP.

We computed the GCM-ensemble average total attributable number and fractions of MI cases by combinations of RCPs and future periods corresponding to warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and 3 °C. We used Monte Carlo simulations to estimate empirical confidence intervals (eCI) to address the uncertainty in ERF and the variability across GCMs. We obtained eCI from the empirical distribution across 5,000 samples of random parameter sets that describe the ERF in the distributed lag nonlinear model and the four GCMs, as described in more detail elsewhere (5, 17). Briefly, we quantified the uncertainty in ERF by using Monte Carlo simulations to generate 5,000 samples for the estimated coefficients from the distributed lag nonlinear model which estimated the ERF. We then generated results for each of the four GCMs. We obtained the 95% eCI, defined as the 2.5 to 97.5 percentiles of empirical distribution across ERF coefficients and GCMs. Thus, the 95% eCI account for both the ERF and GCM sources of uncertainty.