Abstract

Objective:

It has been shown that men with a longstanding psychotic disorder have worse clinical and functional outcomes than women. Our objectives were to examine whether these sex differences are also present among patients treated in an early intervention service (EIS) for psychosis and to determine if these differences are related to risk factors other than sex.

Method:

Patients (N = 569) were assessed for demographic/clinical characteristics at entry and for symptoms/functioning over 2 years of treatment. Clinical outcomes included remission of positive, negative, and total symptoms. Functional outcomes included good functioning and functional remission. Logistic regression models examined the relationship between sex and outcomes after 1 and 2 years of treatment while controlling for the influence of other risk factors.

Results:

Men reported to be less educated and have a longer duration of untreated psychosis, poorer childhood and early adolescent premorbid functioning, higher rates of substance abuse/dependence disorders, greater severity of baseline negative symptoms, and poorer baseline social/occupational functioning than women. Women were more likely to achieve symptom remission than men after 2 years of treatment (negative odds ratio [OR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 2.78; total OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.98). Women were also more likely than men to exhibit good functioning (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.49) after 1 but not after 2 years of treatment. These results did not persist after controlling for other risk factors that could confound these associations (i.e., childhood premorbid functioning and age at onset of psychosis).

Conclusions:

Sex differences seen in outcomes among patients treated in an EIS for psychosis may be largely influenced by the disparity of other risk factors that exist between the 2 sexes.

Keywords: sex difference, schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, early intervention service

Abstract

Objectif:

Il a été démontré que les hommes souffrant d’un trouble psychotique de longue date ont de plus mauvais résultats cliniques et fonctionnels que les femmes. Nos objectifs consistaient à examiner si ces différences entre les sexes sont aussi présentes chez des patients traités dans un service d’intervention précoce (SIP) pour psychose et à déterminer si ces différences sont liées à des facteurs de risque autres que le sexe.

Méthode:

Les patients (N = 569) ont été évalués relativement aux caractéristiques démographiques/cliniques au départ, et aux symptômes et au fonctionnement à 2 ans de traitement. Les résultats cliniques comprenaient la rémission des symptômes positifs, négatifs et généraux. Les résultats fonctionnels comprenaient un bon fonctionnement et une rémission fonctionnelle. Les modèles de régression logistique ont examiné la relation entre le sexe et les résultats après 1 an et 2 ans de traitement, tout en contrôlant l’influence des autres facteurs de risque.

Résultats:

Relativement aux femmes, les hommes ont déclaré avoir moins d’instruction, une durée plus longue de psychose non traitée, une enfance plus défavorisée et un fonctionnement pré-morbide au début de l’adolescence, des taux plus élevés de troubles d’abus et de dépendance à une substance, une gravité plus marquée des symptômes négatifs de base, et un fonctionnement social/professionnel de base plus mauvais. Les femmes étaient plus susceptibles que les hommes d’atteindre la rémission des symptômes après 2 ans de traitement (rapport de cotes [RC] négatif 1,69; IC à 95% 1,02 à 2,78; total-RC 1,79; IC à 95% 1,08 à 2,98). Les femmes étaient également plus susceptibles que les hommes d’afficher un bon fonctionnement (RC 1,61; IC à 95% 1,04 à 2,49) après 1 an de traitement, mais non après 2 ans. Ces résultats n’ont pas persisté après contrôle pour d’autres facteurs de risque qui pourraient confondre ces associations (c.-à-d., le fonctionnement pré-morbide dans l’enfance et l’âge à l’apparition de la psychose).

Conclusions:

Les différences entre les sexes observées dans les résultats de patients traités dans un SIP pour psychose peuvent être largement influencées par la disparité d’autres facteurs de risque qui existent entre les deux sexes.

It is generally accepted that men with a longstanding psychotic disorder have worse clinical and functional outcomes than women.1–3 Men often demonstrate poorer negative symptom outcomes than women,4,5 which typically contributes to experiencing poor functional outcomes.6,7 The worse outcomes seen in men may be attributed to sex-related differences in biology8,9 as well as behavioural and social risk factors that predominate among men. Indeed, men generally exhibit an earlier age at onset of psychosis,10 poorer premorbid functioning,11 lower global functioning,12 higher substance abuse rates,13 and poorer cognition,8 all known risk factors for poor outcomes. Furthermore, men show lower treatment response rates2 and higher disengagement rates with psychiatric services.14

Like those with a longstanding psychotic disorder, past reports suggest that men are less likely to achieve good outcomes than women in early intervention services (EIS) for psychosis.4,5,15,16 However, these past findings may be limited for several reasons. First, most of these studies examined symptom severity as a measure of clinical outcomes rather than symptom remission.4,5,15,16 The latter is often more desirable because of its stronger relationship with functional recovery.7 Second, most of these reports examined functional outcomes as level of functioning,4,5,15,16 which is less clinically meaningful than identifying those who are exhibiting good functioning17 or are in functional remission.18,19 Third, none of these studies controlled for important risk factors that have the potential to confound their results (e.g., age at onset of psychosis).4,5,15,16,20 Finally, the generalizability of some of these findings is low given that some of these samples were derived from randomized controlled trials5 (RCTs) and had experienced lengthy treatment delays (i.e., long durations of untreated psychosis [DUPs]).4,5,20

In this report, we examine whether there are any sex differences in clinical and functional outcomes in a catchment area-based sample of patients treated in an EIS for psychosis. We also explore whether any of the observed sex differences in outcomes would persist after controlling for risk factors that could potentially confound our results. We hypothesize that any sex difference seen in outcomes will be largely affected by the disparity of other risk factors between the 2 sexes.

Methods

Participants and Settings

Data on patients receiving treatment in an EIS for psychosis (Prevention and Early Intervention Program [PEPP-Montreal]) between 2003 and 2016 and who had consented to participate in research were used in this study. PEPP-Montreal serves a French/English-speaking population of 300,000 inhabitants in southwest Montreal, Canada. The inclusion criteria for these services are age 14 to 35 years, diagnosis of nonaffective or affective psychosis, prior treatment with antipsychotics not >30 days, and an IQ ≥70 based on the short-form Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.21 The exclusion criteria are major medical disorders that can explain the psychosis (e.g., traumatic brain injury) or substance-induced psychosis. Patients with concurrent substance abuse/dependence disorders are included.

The EIS offers lowest effective dose pharmacotherapy, assertive case management (ratio 20:1), family intervention, psychological therapies, psychosocial programs, crisis interventions, and interventions to reduce treatment delays.22,23 At baseline, patients are approached to participate in a research protocol where trained research staff assesses demographic, clinical, and functional measures. Assessment of clinical and functional measures is repeated throughout the 2 years of treatment. Men and women who had completed at least 1 year of treatment and had functional measures data at baseline and at 1 year of treatment were selected for this study.

Assessment of Variables

Positive and negative symptoms were assessed using the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)24 and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).25 Depression and anxiety were measured with the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS)26 and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS).27

Functioning was assessed using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)28 and the Strauss Carpenter Scale (SC).29,30 The SOFAS provides a global rating of social/occupational functioning in the past year, while the SC examines the degree of social contact (i.e., frequency of seeing friends/family) and education/vocation (i.e., amount of time spent in school or at work) of patients in the past year.

Age at onset of psychosis and DUP were determined from the Circumstance of Onset and Relapse Schedule30 (CORS). CORS is a semistructured interview that is supplemented with information from families and educational/medical records. Age at onset of psychosis was defined as the age when the patient first exhibited a threshold level of psychotic symptoms. DUP was defined as the time (weeks) between the onset of threshold-level psychotic symptoms and the start of 30 days of continuous antipsychotic medication, consistent with previous reccomendations.31 Premorbid functioning was assessed with the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS),32 which provides scores for social and academic functioning during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Given that the age at onset of psychosis often overlaps with late adolescence and early adulthood,33 we considered only the PAS scores for childhood and early adolescence.

Antipsychotic medication adherence rates were calculated from assessments conducted 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months into treatment with the use of a validated method that included information obtained from patients and their families, case managers, and clinical notes.34 Patients taking 75% to 100% of their antipsychotic medication at each assessment were considered adherent, while those taking 0% to 74% at any point during treatment were considered nonadherent. Diagnoses for the psychotic disorder and concurrent substance abuse/dependence disorders were determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.35 Diagnoses for psychotic disorders were clustered as nonaffective (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, psychosis not otherwise specified [NOS]) and affective psychosis (bipolar or depressive disorders with psychotic symptoms). Additional variables analyzed for this study (e.g., relationship status) were self-reported by patients at baseline.

Definitions for Clinical and Functional Outcomes

Clinical outcomes

Remission of symptoms was examined after 1 and 2 years of treatment. We defined patients to be in remission of symptoms if they had a symptom severity of mild or less at each assessment in the past 6 months, consistent with the recommendations from the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.36 Patients scoring ≤2 on all global items on the SAPS at each assessment in the past 6 months were in remission for positive symptoms, while those scoring ≤2 on all global items on the SANS at each assessment in the past 6 months were in remission for negative symptoms. Those who achieved remission of positive and negative symptoms concurrently at each assessment in the past 6 months were in remission for total symptoms.

Functional outcomes

Functional outcomes were examined after 1 and 2 years of treatment. Scoring >60 on SOFAS was considered exhibiting good functioning.17 Those displaying good functioning and in school/working full- or part-time in the past year (SC educational/vocational subscale score ≥2) were in functional remission.18,19

Data Analysis

We examined sex differences in variables at baseline as well as after 1 and 2 years of treatment for clinical and functional outcomes. Independent t tests were used to explore for differences in continuous variables, while chi-square tests were conducted to examine for differences in binary variables. Continuous variables were described as unadjusted means with standard deviations, and binary variables were reported as percentages.

Bivariate logistic regression models were used to examine associations between sex and outcomes after 1 and 2 years of treatment. For significant bivariate models, we then adjusted for variables that may potentially confound the relationship between sex and outcomes. To identify potential confounds, we first examined the literature for previous reports that have linked variables independently to both sex and outcomes, respectively. We then examined whether any of these theoretical confounds from the literature may mediate the association between sex and the outcome via PROCESS37 in SPSS (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL). Each mediation model conducted 1000 bootstrapped samples. The theoretical confound was identified to be a significant mediator if the indirect effect of sex predicting the outcome did not contain 0 between its upper and lower bootstrapped confidence interval. For the theoretical confounds that were not found to mediate the association between sex and the outcome, we then adjusted for them in our multivariate models. All statistical tests in this study were conducted in SPSS version 23.0, and significance was set at α < 0.05.

Ethical and Consent Considerations

We assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of the Douglas Institute Research Ethics Board and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Douglas Institute Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Results

Study Population and Sample

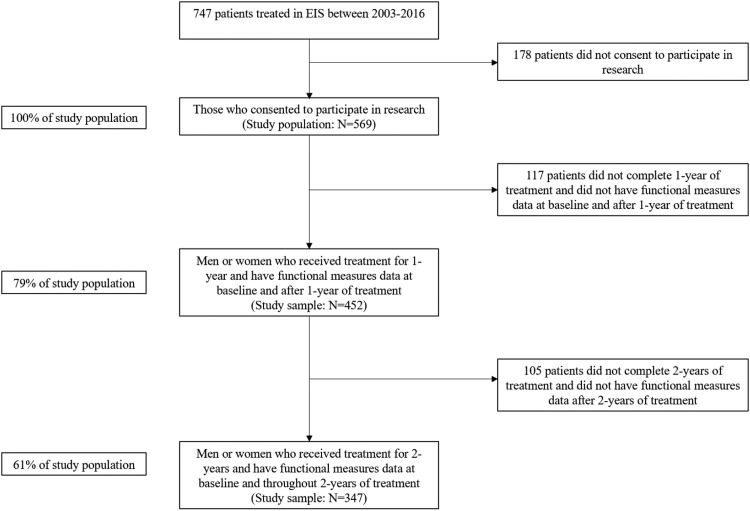

Of the 747 patients accepted for treatment in this EIS from 2003 to 2016, 569 consented to research (i.e., the study population) while 178 of these did not (Figure 1). Since these 178 patients did not consent to research, we cannot compare them with our study population as we were unable to collect any relevant data on them. Based on our selection criteria, 452 patients from our study population were eligible for analysis (79% of the study population). Those who were eligible had a significantly lower childhood total PAS score than those who were not eligible (0.21 ± 0.14 vs. 0.26 ± 0.15, P = 0.04) (Suppl. Table S1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study population and sample. EIS, early intervention service for psychotic disorders.

Among our study sample (N = 452), 347 of these completed 2 years of treatment and had functional measures data throughout 2 years of treatment (61% of the total study population) (Figure 1). Women reported a significantly higher attrition rate than men (30% vs. 20%, P = 0.03). Those who completed 2 years of treatment (N = 347) were more adherent to antipsychotic medications during the first year of treatment than those who only completed 1 year of treatment (N = 105) (64% vs. 45%, P < 0.01). No other variable significantly differed between these 2 groups (Suppl. Table S2).

Sex Differences over 2 Years of Treatment

In our study population (N = 569), men (n 1 = 391) and women (n 2 = 177) differ significantly in their education status, DUP, total PAS score and academic PAS subscore during both childhood and early adolescence, substance abuse/dependence disorder rates, and SANS, CDSS, and SOFAS scores (Table 1). The sex difference in the age at onset of psychosis was borderline significant (Table 1). There were no significant sex differences in antipsychotic medication adherence rates during the first year of treatment (N = 452; 60% vs. 62%, P = 0.80) or throughout 2 years of treatment (N = 347; 52% vs. 61%, P = 0.21).

Table 1.

Differences in Demographics and Clinical Variables between Men and Women at Baseline from Study Population (N = 569).

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N = 569)a | Men (n 1 = 391) | Women (n 2 = 177) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry, y | 23.63 ± 4.62 | 23.49 ± 4.48 | 23.96 ± 4.90 | 0.26b |

| Relationship status (single) | 495 (90) | 350 (91) | 144 (86) | 0.08c |

| Education status (completed high school or more) | 356 (66) | 234 (63) | 121 (72) | 0.03c |

| Mode of entry (outpatients) | 305 (54) | 210 (54) | 94 (53) | 0.87c |

| Age at onset of psychosis, y | 22.73 ± 4.75 | 22.50 ± 4.50 | 23.34 ± 5.07 | 0.05b |

| DUP, wk | 54.78 ± 113.27 (Median: 15.00) | 61.18 ± 123.11 (Median: 16.00) | 36.01 ± 68.04 (Median: 12.00) | <0.01b |

| Childhood total PAS score | 0.21 ± 0.14 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.13 | 0.02b |

| Early adolescence total PAS score | 0.27 ± 0.16 | 0.29 ± 0.16 | 0.22 ± 0.14 | <0.01b |

| Childhood social PAS subscore | 0.19 ± 0.21 | 0.19 ± 0.20 | 0.20 ± 0.22 | 0.70b |

| Childhood academic PAS subscore | 0.24 ± 0.19 | 0.27 ± 0.19 | 0.18 ± 0.15 | <0.01b |

| Early adolescence social PAS subscore | 0.23 ± 0.22 | 0.23 ± 0.21 | 0.22 ± 0.23 | 0.82b |

| Early adolescence academic PAS subscore | 0.34 ± 0.24 | 0.39 ± 0.24 | 0.22 ± 0.19 | <0.01 b |

| Diagnosis of nonaffective psychotic disorder | 395 (71) | 279 (73) | 115 (66) | 0.10c |

| Diagnosis of substance abuse/dependence | 279 (54) | 218 (61) | 61 (37) | <0.01c |

| SAPS total score | 34.24 ± 15.05 | 34.04 ± 14.35 | 34.63 ± 16.62 | 0.68b |

| SANS total score | 24.62 ± 13.61 | 25.64 ± 13.73 | 22.39 ± 13.07 | 0.01b |

| CDSS total score | 5.02 ± 4.75 | 4.68 ± 4.72 | 5.77 ± 4.75 | 0.01b |

| HARS total score | 10.21 ± 7.59 | 10.14 ± 7.76 | 10.37 ± 7.22 | 0.76b |

| SOFAS score | 41.25 ± 13.22 | 39.98 ± 12.79 | 44.04 ± 13.79 | <0.01b |

| Good functioning | 45 (9) | 26 (7) | 19 (12) | 0.09c |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). Bold values refer to statistical significance α < 0.05.

CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PAS, Premorbid Adjustment Scale; SANS, Scale for Assessment for Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment for Positive Symptoms; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale.

aOne patient did not identify as either man or woman.

bTwo-sided t test comparing unadjusted means between men and women.

cChi-square test comparing proportions between men and women. Significance was set at α < 0.05.

Clinical outcomes

There were no significant sex differences in symptom remission rates after 1 year of treatment (Tables 2 and 3). After 2 years of treatment, women were more likely than men to be in remission of negative (odds ratio [OR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-2.78) and total symptoms (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.08-2.98).

Table 2.

Differences in Outcomes between Men and Women following 1 and 2 Years of Treatment.

| Characteristic | After 1 Year of Treatment (N = 452) | After 2 Years of Treatment (N = 347) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n 1 = 307), n (%) | Females (n 2 = 145), n (%) | P Value | Males (n 1 = 245), n (%) | Females (n 2 = 102), n (%) | P Value | |

| Remission of positive symptoms | 147 (57) | 72 (60) | 0.58a | 126 (58) | 64 (70) | 0.06a |

| Remission of negative symptoms | 61 (24) | 39 (32) | 0.08a | 70 (32) | 41 (45) | 0.04 a |

| Remission of total symptom | 55 (21) | 34 (28) | 0.14a | 61 (28) | 38 (41) | 0.03 a |

| Good functioning | 123 (48) | 74 (60) | 0.03a | 98 (52) | 45 (63) | 0.14a |

| Functional remission | 84 (36) | 49 (46) | 0.10a | 61 (43) | 26 (50) | 0.40a |

Bold values refer to statistical significance α < 0.05.

aChi-square test comparing proportions between men and women. Significance was set at α < 0.05.

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multivariate Analyses Comparing Sex Differences and Outcomes following 1 and 2 Years of Treatment.

| Characteristic | After 1 Year of Treatment (N = 452) | After 2 Years of Treatment (N = 347) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate Model, OR (95% CI) | Multivariate Model, Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Bivariate Model, OR (95% CI) | Multivariate Model, Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Positive symptom remission | 1.13 (0.73 to 1.76) | — | 1.65 (0.98 to 2.78) | — |

| Negative symptom remissiona | 1.54 (0.95 to 2.48) | — | 1.69 (1.02 to 2.78) | 1.28 (0.70 to 2.34) |

| Total symptom remissionb | 1.45 (0.88 to 2.39) | — | 1.79 (1.07 to 2.98) | 1.60 (0.88 to 2.90) |

| Good functioningc | 1.61 (1.04 to 2.49) | 1.54 (0.89 to 2.65) | 1.51 (0.87 to 2.64) | — |

| Functional remission | 1.48 (0.93 to 2.35) | — | 1.31 (0.69 to 2.48) | — |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

aMultivariate model adjusted for childhood PAS score, early adolescent PAS score, and age at onset of psychosis.

bMultivariate model adjusted for childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis.

cMultivariate model adjusted for childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis.

Our literature review suggested that childhood premorbid functioning,11,38–40 early adolescent premorbid functioning,11,38–40 age at onset of psychosis,10,41 and global functioning prior to treatment7,12,15,20,38 may have the potential to confound the observed associations between sex and symptom remission. Mediation models indicated that only baseline SOFAS score produced a significant indirect effect on sex predicting negative symptom remission after 2 years of treatment (β = 0.0959 [Boot SE = 0.0618]; Boot CI, 0.0040 to 0.2478) (Suppl. Figure S1). However, total childhood PAS score, total early adolescent PAS score, and age at onset of psychosis did not demonstrate such significant results (Suppl. Figures S2-S4). Total early adolescent PAS score (β = 0.1658 [Boot SE = 0.1011]; Boot CI, 0.0016 to 0.4041) and baseline SOFAS score (β = 0.1105 [Boot SE = 0.0628]; Boot CI, 0.0119 to 0.2578) each produced a significant indirect effect on sex predicting total symptom remission following 2 years of treatment (Suppl. Figures S5-S6). However, total childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis did not exhibit such significant findings (Suppl. Figures S7-S8).

After controlling for potential confounds (total childhood PAS score, early adolescent PAS score, and age at onset of psychosis), sex no longer significantly predicted negative symptom remission after 2 years of treatment (adjusted OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.70 to 2.34). Sex also no longer significantly predicted total symptom remission after 2 years of treatment (adjusted OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 0.88 to 2.90) following the adjustment of potential confounds (total childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis).

Functional outcomes

After 1 year of treatment, women were significantly more likely than men to exhibit good functioning (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.49) (Table 3). There was no significant sex difference in achieving functional remission after 1 year of treatment (Tables 2 and 3). Also, there were no significant sex differences in either of the 2 functional outcomes after 2 years of treatment.

Past reports suggest that childhood premorbid functioning,7,11,38,39 early adolescent premorbid functioning,7,11,38,39 age at onset of psychosis,10,41 and the severity of negative symptoms prior to treatment5,7,16 may potentially confound relationships between sex and functional outcomes. Our mediation model demonstrated that total early adolescent PAS score (β = 0.2312 [Boot SE = 0.0965]; Boot CI, 0.0772 to 0.4588) and baseline SANS score (β = 0.1098 [Boot SE = 0.0596]; Boot CI, 0.0066 to 0.2386) each had a significant indirect effect on sex predicting good functioning after 1 year of treatment (Suppl. Figures S9-S10). However, total childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis did not produce such significant findings (Suppl. Figures S11-S12).

After adjusting for potential confounds (total childhood PAS score and age at onset of psychosis), sex no longer significantly predicted good functioning after 1 year of treatment (adjusted OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 0.89 to 2.65) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this large and well-characterized sample of patients from an EIS for psychosis, we examined whether there were any sex differences in clinical and functional outcomes. Our results from unadjusted models showed that women were more likely than men to be in good functioning following 1 year of treatment (Tables 2 and 3). After 2 years of treatment, while women were more likely to have better clinical outcomes, there were no sex differences in any of the functional outcomes (Tables 2 and 3). After controlling for risk factors that could potentially confound our results, the observed sex differences in clinical and functional outcomes did not persist (Table 3). Therefore, our findings support our hypothesis that the sex differences seen in outcomes from an EIS for psychosis may be largely affected by the disparity of other risk factors between the 2 sexes.

The observed sex differences in functional outcomes were rather nuanced. Despite more women significantly exhibiting good functioning after 1 year of treatment, this sex difference was not present following 2 years of treatment (Table 2). Moreover, there were no significant sex differences in functional remission rates throughout 2 years of treatment. These findings suggest that EIS may require more than 1 year to effectively improve the overall functioning of men. This may be partially related to men in our sample presenting with poorer early adolescent premorbid functioning than women as we report that this variable was a significant mediator in the relationship between sex and good functioning after 1 year of treatment (Suppl. Figure S9). In addition, it is possible that the greater severity of negative symptoms seen among men may have limited their ability to engage with the psychosocial interventions aimed at improving their functional outcomes (e.g., employment/educational supported programs) during their first year of treatment.42 Indeed, this is supported by the observed mediation of baseline negative symptoms on sex predicting good functioning after 1 year of treatment (Suppl. Figure S10). Therefore, reducing negative symptoms during the first year of treatment may be critical in improving functional outcomes. Patients may benefit from more frequent and intensive psychological therapies during their first year in EIS as multiple meta-analyses have suggested that these interventions are effective in reducing negative symptoms.43,44 Furthermore, 1 meta-analysis has suggested that pharmacological options such as antidepressants or glutamatergic agents may also be helpful in reducing negative symptoms.43

After 2 years of treatment, more women significantly reported to be in remission of negative and total symptoms (Table 2). These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that women may experience better clinical outcomes than men after 2 years of treatment in EIS.4,5 Given our results and these past reports, some men may need more than 2 years of EIS to achieve good clinical outcomes. This is particularly important for negative symptoms as only one-third of men achieved negative symptom remission after 2 years of treatment (Table 2). Recent evidence has shown that patients receiving EIS care beyond 2 years may continue to experience further reductions in negative symptoms, specifically those related to expressivity (e.g., affect flattening or alogia).45 Such improvements are likely related to patients continuing to receive psychological interventions in EIS care.43,44 However, the study indicated that the severity of motivational-based negative symptoms (e.g., anhedonia or avolition) remained stable during the additional years of treatment in EIS.45 Regardless, transferring men to regular care (i.e., primary care or non-EIS psychiatric clinics) after completing 2 years of EIS may increase their risk of experiencing poorer clinical outcomes given that they still exhibit severe negative symptoms (Table 2), and this may lead them to disengage with treatment42 in regular care. In a recent RCT in which all patients who completed 2 years of EIS were randomized to receiving a 3-year extension of EIS (EEIS) or 3 years of regular care, patients receiving EEIS remained in treatment longer and engaged in more interventions than those receiving regular care.46 Furthermore, the EEIS produced longer lengths of positive, negative, and total symptom remission than regular care.46 As previously reported,46,47 patients in EEIS are more likely to continue to engage in treatment compared to regular care because the assertive case management model employed by EIS ensures that case managers regularly contact patients (at least twice a month) and actively support them in completing their treatment plans. Thus, the continuation of receiving assertive case management from EEIS may help men to continue to engage in treatment and subsequently yield better clinical outcomes.

While it may be expected that premorbid functioning may mediate the effects of sex on outcomes, our mediation models suggest that premorbid functioning during early adolescence (Suppl. Figures S5 and S9) and not during childhood (Suppl. Figures S2, S7, and S11) may act as a mediator in these associations. Although men may generally exhibit poorer premorbid functioning than women during childhood,11,39 there is the possibility that some men may experience functional improvements once they reach early adolescence. Indeed, past evidence has shown that some patients display a positive trajectory in which premorbid functioning improves from childhood to early adolescence.48 However, the poorer premorbid functioning generally found among men during early adolescence11,39 is likely to be a mediator because their first episode of psychosis and the treatment for it in an EIS typically occur between late adolescence and early adulthood.33 Given this implication, we removed early adolescent premorbid functioning from our multivariate model examining sex and negative symptom remission after 2 years of treatment and only adjusted for childhood premorbid functioning and age at onset of psychosis. The association remained nonsignificant (adjusted OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.82 to 2.60).

Age at onset of psychosis is also thought to mediate the effects of sex on outcomes as the earlier age of onset commonly found among men may lead them to experience poorer psychosocial development and therefore poorer outcomes. However, we did not identify age at onset of psychosis as a mediator in the associations between sex and outcomes (Suppl. Figures S4, S8, and S12). Despite bordering on statistical significance, the sex difference in the age at onset in our study is rather minor, with men developing psychosis nearly 1 year earlier than women (Table 1). Our findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating that men may generally develop psychosis approximately 1 year earlier than women.10 Thus, age at onset of psychosis may only mediate these associations if men experience a far earlier onset that would substantially impair their psychosocial development.

It is possible that the results seen after 2 years of treatment may be affected by the higher attrition rate among women. To explore this, we compared baseline variables and 1-year outcomes between women who completed only 1 year of treatment with women who completed 2 years of treatment (Suppl. Table S3). There were no significant differences between these 2 groups for any variable. Hence, it is not likely that the higher attrition rate among women affected our results after 2 years of treatment. Women may have had a higher attrition rate because more of them exhibited good functioning than men after 1 year of treatment (Table 2). Hence, some women may have felt that they did not require more help after completing 1 year of treatment. In addition, the higher attrition rate among women may be related to their smaller sample size (31% of study population). Despite these limited data, we examined whether weight gain during the first year of treatment and severity of extrapyramidal symptoms49 at the end of the first year of treatment may have contributed to the observed sex difference in attrition rates (Suppl. Table S4). We found no significant sex differences in these side effects.

Limitations

Unfortunately, our study does have some limitations. First, we were unable to examine the influence of factors that may vary during treatment (e.g., quantity and frequency of substance abuse). Second, our final study sample is 61% of our study population (Figure 1). This 39% attrition rate is a combination of patients dropping out of treatment and missing data on functional measures. The attrition rate seen in our study is comparable to other cohort studies consisting of patients being treated for 2 years in an EIS for psychosis (e.g., OPUS trial: 33% attrition rate).5 Furthermore, we conducted a supplementary analysis comparing baseline variables between our final study sample (N = 347) and those that were not apart of it (N = 222) (Suppl. Table S5). The final study sample reported only a significantly shorter length of DUP than those who were not part of it. Third, we did not examine rates of antipsychotic-induced amenorrhea as this may have contributed to the higher attrition rate seen among women. Furthermore, it may have also affected our results after 2 years of treatment given that women developing amenorrhea would lose the beneficial effects that estrogen has in psychotic disorders.50 Although all patients were treated with a low-dose second-generation antipsychotic and side effects were carefully monitored, if serious side effects had arisen (e.g., amenorrhea), medications would have been changed immediately. Regardless, future research examining sex differences in longitudinal outcomes in psychotic disorders should measure rates of antipsychotic-induced amenorrhea to examine if it affects attrition and any observed sex difference in outcomes. Last, we were unable to understand the role that gender identification may have had in our study. Gender may exist as a spectrum of different phenotypes (cis-man, cis-woman, trans-man, trans-woman, etc.), and classifying it as simply man or woman may not be valid. Only 1 patient in the study population did not identify as either a man or woman, and we excluded this person from our statistical analyses. Future studies examining the wide spectrum of gender and its role on outcomes in psychotic disorders are needed.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings suggest that it may take men more time than women to achieve good clinical and functional outcomes in EIS for psychosis. Furthermore, our results suggest that sex differences seen in outcomes may be largely driven by the disparity of other risk factors between the 2 sexes. Overall, it is it is hoped that this report will alert clinicians in developing treatment plans that might need to be adjusted for men given that they often present with several risk factors for poor clinical and functional outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, 854069_Supplementary_Material for Sex Differences in Clinical and Functional Outcomes among Patients Treated in an Early Intervention Service for Psychotic Disorders: An Observational Study by Manish Dama, Franz Veru, Norbert Schmitz, Jai Shah, Srividya Iyer, Ridha Joober and Ashok Malla in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their families as well as the PEPP-Montreal research staff.

Footnotes

Data Access: Please contact ashok.malla@mcgill.ca for more detail on accessing the data used in this report.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.D. has nothing to disclose. F.V. reports he is supported through a doctoral training award granted by the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé. N.S. has nothing to disclose. J.S. has nothing to disclose. S.I. reports she has received salary awards from Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, as well as grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. R.J. reports that he sits on the advisory board and speakers bureaus of Pfizer, Janssen Ortho, BMS, Sunovion, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Perdue, and Myelin. He has also received grant funding from them and from Astra Zeneca and HLS. He has also received honoraria from Janssen Canada, Shire, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Perdue for CME presentations and royalties from a Henry Stewart talk. None of these are related to the study reported here. A.M. reports receiving research funding for an investigator-initiated project, unrelated to the present article, from BMS Canada and honoraria for lectures and consulting activities (e.g., advisory board participation) with Otsuka and Lundbeck, all unrelated to the present article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Manish Dama, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6429-6187

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6429-6187

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Usall J, Ochoa S, Araya S. et al. NEDES Group (Assessment Research Group in Schizophrenia). Gender differences and outcome in schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up study in a large community sample. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(6):282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Usall J, Suarez D, Haro JM; SOHO Study Group. Gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153(3):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C, et al. Sex differences in outcome and recovery for schizophrenia and other psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koster A, Lajer M, Lindhart A, et al. Gender differences in first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(12):940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thorup A, Albert N, Bertelsen M, et al. Gender differences in first-episode psychosis at 5-year follow-up—two different courses of disease? Results from the OPUS study at 5-year follow-up. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(1):44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan G, Lutgens D, Joober R, et al. The relative contribution of cognition and symptomatic remission to functional outcome following treatment of a first episode of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):e566–e572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santesteban-Echarri O, Paino M, Rice S, et al. Predictors of functional recovery in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:59–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendrek A, Mancini-Marie A. Sex/gender differences in the brain and cognition in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;67:57–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Silva TL, Ravindran AV. Contribution of sex hormones to gender differences in schizophrenia: a review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;18:2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eranti SV, MacCabe JH, Bundy H, et al. Gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43(1):155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allen DN, Strauss GP, Barchard KA, et al. Differences in developmental changes in academic and social premorbid adjustment between males and females with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1-3):132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Usall J, Haro JM, Ochoa S. et al. Needs of Patients with Schizophrenia Group. Influence of gender on social outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(5):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, et al. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990-2017: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:234–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nose M, Barbui C, Tansella M. How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes? A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cotton SM, Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, et al. Gender differences in premorbid, entry, treatment, and outcome characteristics in a treated epidemiological sample of 661 patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;114(1-3):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang WC, Tang JY, Hui CL, et al. Gender differences in patients presenting with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong: a three-year follow up study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2011;45(3):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cassidy CM, Norman R, Manchanda R, et al. Testing definitions of symptom remission in first-episode psychosis for prediction of functional outcome at 2 years. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(5):1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang WC, Tang JY, Hui CL, et al. Prediction of remission and recovery in young people presenting with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong: a 3-year follow-up study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2012;46(2):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verma S, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, et al. Symptomatic and functional remission in patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(4):282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pang S, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, et al. Gender differences in patients with first-episode psychosis in the Singapore Early Psychosis Intervention Programme. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(6):528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christensen BK, Girard TA, Bagby RM. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition short form for index and IQ scores in a psychiatric population. Psychol Assess. 2007;19(2):236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iyer S, Jordan G, MacDonald K, et al. Early intervention for psychosis: a Canadian perspective. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malla A, Jordan G, Joober R, et al. A controlled evaluation of a target early case detection intervention for reducing delay in treatment of first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(11):1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(9):1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT., Jr The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: II. Relationships between predictor and outcome variables: a report from the WHO International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;31(1):37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT., Jr Prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: III. Five-year outcome and its predictors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(2):159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Compton MT, Carter T, Bergner E, et al. Defining, operationalizing and measuring the duration of untreated psychosis: advances, limitations and future directions. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1(3):236–250. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8(3):470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hafner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, et al. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cassidy CM, Rabinovitch M, Schmitz N, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to antipsychotic medication in first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, et al. Gender differences in young adults with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders at baseline in the Danish OPUS study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(5):396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bertani M, Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, et al. The influence of gender on clinical and social characteristics of patients at psychosis onset: a report from the Psychosis Incident Cohort Outcome Study (PICOS). Psychol Med. 2012;42(4):769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. MacBeth A, Gumley A. Premorbid adjustment, symptom development and quality of life in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and critical reappraisal. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(2):85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Immonen J, Jaaskelainen E, Korpela H, et al. Age at onset and the outcomes of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;11(6):453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Macbeth A, Gumley A, Schwannauer M, et al. Service engagement in first episode psychosis: clinical and premorbid correlates. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(5):359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatments of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):892–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lutgens D, Gariepy G, Malla A. Psychological and psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms in psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lutgens D, Joober R, Iyer S, et al. Progress of negative symptoms over the initial 5 years of a first-episode of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Malla A, Joober R, Iyer S, et al. Comparing three-year extension of early intervention service to regular care following two years of early intervention service in first-episode psychosis: a randomized single blind clinical trial. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dama M, Shah J, Norman R, et al. Short duration of untreated psychosis enhances negative symptom remission in extended early interventions service for psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. April 9 [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1111/acps.13033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cole VT, Apud JA, Weinberger DR, et al. Using latent class growth analysis to form trajectories of premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(2):388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chounard G, Margolese HC. Manual for the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS). Schizophrenia Res. 2005;76(2-3):247–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hafner H. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psycchoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(suppl 2):17–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, 854069_Supplementary_Material for Sex Differences in Clinical and Functional Outcomes among Patients Treated in an Early Intervention Service for Psychotic Disorders: An Observational Study by Manish Dama, Franz Veru, Norbert Schmitz, Jai Shah, Srividya Iyer, Ridha Joober and Ashok Malla in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry