Abstract

Objective.

Syndemic theory posits that co-occurring problems (e.g., substance use, depression, and trauma) synergistically increase HIV risk in men who have sex with men (MSM). However, most investigations have assessed these problems additively using self-report.

Methods.

In a sample of HIV-negative MSM with trauma histories (n=290), we test bivariate relationships between four clinical diagnoses (substance use disorder (SUD); major depressive disorder (MDD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders) and their additive and interactive effects on three health indicators (i.e., high-risk sex, visiting the emergency room (ER), and sexually transmitted infections (STIs)).

Results.

We found significant bivariate relationships between SUD and MDD (χ2 = 4.85 p=0.028) and between PTSD and MDD (χ2 = 35.38 p=0.028, p<.001), but did not find a significant relationship between SUD and PTSD (χ2 = 3.64 p=0.056). Number of diagnoses were associated with episodes of high-risk sex (IRR=1.14, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.26, p=.009) and visiting the ER (OR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.60, p= .040) but not with STIs. No interactions were found between diagnoses and health-related indicators.

Conclusions.

This is the first study to demonstrate additive effects of clinical diagnoses on risk behavior and health care utilization among MSM with developmental trauma histories. Results indicate the need to prioritize empirically supported treatments for SUD and MDD, in addition to trauma treatment, for this population.

TRIAL REGISTRATION:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

Keywords: HIV, syndemics, men who have sex with men (MSM), mental health, comorbidity

While gay and bisexual men account for an estimated 2% of the US population, they account for 70% of new HIV infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Currently, approximately 492,000 sexually active gay and bisexual men are at high risk for HIV acquisition (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Syndemic theory, as applied to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), posits that co-occurring problems such as substance use, depression, and trauma, synergistically increase HIV risk and acquisition. Starting with Stall’s seminal work (Stall et al., 2003), syndemic theory research has identified additive influences of co-occurring psychosocial problems, ranging from early life adversities to current psychological and behavioral challenges, in relation to health-related outcomes such as HIV risk behavior, HIV acquisition, HIV viral load, medication adherence, and healthcare utilization among MSM (Dyer et al., 2012; Friedman et al., 2015; Herrick et al., 2013; Mimiaga et al., 2015; Mustanski, Andrews, Herrick, Stall, & Schnarrs, 2014; Stall, Friedman, & Catania, 2008), as well as women (e.g., Batchelder et al., 2016).

However, there are several limitations with the current state of the syndemic literature. First, the measurement of syndemic psychosocial problems often involves brief self-report items, which do not evaluate clinically significant thresholds of severity consistent with psychiatric diagnoses. Relatedly, the psychosocial problems included in syndemic investigation often range from distal experiences of events (such as childhood sexual abuse) to recent states (such as substance use or self-reported depressive symptoms) likely impacting individuals to varying extents. Finally, the majority of this work has investigated additive, rather than interactive or synergistic, relationships between syndemic psychosocial problems, risk, and health outcomes, despite interactive relationships being more consistent with the synergy described in syndemic theory (Singer, 2000, 2006; Tsai, Mendenhall, Trostle, & Kawachi, 2017).

To date, investigations of syndemics, or co-occurring psychosocial problems, include epidemiologically-oriented conceptualizations of psychosocial problems using self-report, and in some cases single self-reported items (Halkitis et al., 2015; Mustanski et al., 2014; Stall et al., 2003). These self-report measures are often conceptualized as proxy measures of psychiatric diagnoses, thus equating self-reported symptoms or events with clinician-assessed diagnostic thresholds of clinically meaningful severity. However, self-reported symptoms or endorsement of historical events are not equivalent to a clinical diagnostic assessment in that individuals can easily under- or over-estimate severity and impairment with limited opportunity for clarification. Specifically, previous studies have found clinically assessed depression to be associated with medication nonadherence while self-reported depressive symptoms were not (Gonzalez et al., 2011). Clinician-administered assessment of psychiatric diagnoses enables the clarification of severity, clinically significant impairment, and the ability to differentiate attribution of symptoms that may overlap across diagnoses (e.g., a clinician can clarify whether disrupted sleep is attributable to post-traumatic stress disorder , depression, or both). Further, psychiatric diagnoses have been associated with health indicators including sexual risk behaviors, acquiring a sexually transmitted infection (STI), and health care utilization, including emergency room (ER) visits (Joyce, Chan, Orlando, & Burnam, 2005; O’Cleirigh, Skeer, Mayer, & Safren, 2009). Additionally, in primary care settings, psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders have been additively negatively associated with health indicators including health-related quality of life, functioning, and more sick days used (Rapaport, Clary, Fayyad, & Endicott, 2005; Stein et al., 2005) and specifically generalized anxiety disorder has been associated with ER visits (Buccelletti et al., 2013; Demiryoguran et al., 2006). Further, co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses have been associated with higher rates of sexual risk behavior (Bishop, Maisto, & Spinola, 2016), ER visits (Minassian, Vilke, & Wilson, 2013), and sexually transmitted diseases (Meade, 2006), consistent with syndemic theory. To date, we are not aware of any syndemic investigations that have used clinically evaluated psychiatric diagnoses in populations at-risk for HIV.

In addition to the aforementioned challenges, previously used self-report measures have assessed psychosocial problems of varying retrospective timeframes, which may inaccurately capture relative influences on current health outcomes. For example, syndemic investigation often involves questions about exposure to childhood sexual abuse (CSA) or intimate partner violence. While exposure to a specific traumatic event provides information about an individual’s lived experience, the variability of impact on individuals’ current functioning is not captured, including whether the individual’s symptoms meet diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder or another anxiety disorder. The inclusion of CSA as a syndemic problem is particularly challenging given the potential developmental implications and the length of time since the abuse. Further, conceptualizing the influence of CSA as equivalent to that of more recent syndemic problems (e.g., current depression and substance use) raises challenges for interpretation. Given the prevalence of CSA among MSM (Lenderking et al., 1997), and relationships to engagement in high risk sex (Banducci, Hoffman, Lejuez, & Koenen, 2014; Boroughs et al., 2015), investigation of current psychiatric diagnoses among a sample of MSM who have experienced CSA is needed to better understand how current syndemic comorbidities contribute to health outcomes.

Finally, while over 40 studies have investigated the co-occurrence of psychosocial syndemic problems in relation to HIV, few have compared the additive versus interactive, or multiplicative, relationships (Tsai & Burns, 2015), despite being more consistent with syndemic theory’s description of the “synergistic” effects of syndemic problems (Singer, 2000, 2006; Tsai et al., 2017). One study compared additive versus interactive effects of five syndemic problems (i.e., substance use, self-reported depressive symptoms, endorsed intimate partner violence, history of childhood sexual abuse, and perceived financial hardship) in predicting high-risk sex among women with and at-risk for HIV (Batchelder et al., 2016). This work identified that endorsing both substance use and violence was associated with more sexual risk. Internationally, several researchers have indentified additive and, more inconsistently, interactive associations beteween syndemic problems and health-related outcomes (e.g., Okafor et al., 2018; Pitpitan et al., 2013; Tomori et al., 2018). However, we are not aware of any studies that have compared additive versus interactive relationships between syndemic psychiatric diagnoses and sexual risk or healthcare utilization among MSM with histories of CSA. Investigation comparing additive versus interactive relationships of current comorbid psychiatric diagnoses among MSM with histories of CSA may have specific public health implications. Specifically, it is not known whether the number of specific comorbid psychiatric diagnoses are additively or interactively associated with sexual risk behavior or healthcare utilization among MSM with trauma histories.

To date, syndemic investigation has assessed the cumulative impact of epidemiologically-oriented self-reported problems, which limits the accurate assessment and impact of these problems, including whether they additively and interactively contribute to health indicators. Together, this results in limited information about which problem(s) should be prioritized clinically to improve health outcomes. A better understanding of how clinically significant current psychiatric comorbidities are related to health indicators is needed to inform public health priorities and strategies for more effectively reducing HIV risk among MSM. This is the first study we are aware of to investigate the co-occurrence of clinical diagnoses in relation to three key health-related indicators (sexual risk behavior, STIs, and visiting the ER) in a sample of MSM who have experienced CSA.

Method

Procedures and Measures

Data were collected as part of a multi-site randomized clinical trial of HIV-uninfected MSM (N=290), located in Boston, Massachusetts and Miami, Florida between 2011–2016. All participants completed a comprehensive baseline assessment that included HIV and other STI testing, a computer-based self-report assessment, and a structured clinical interview conducted by trained clinical staff, including licensed clinical psychologists, doctoral level clinical psychology graduate students, and clinical social workers (further methods described elsewhere; Batchelder et al., 2017; Boroughs et al., 2015). Eligibility criteria included: (1) being HIV-uninfected, confirmed via rapid testing, (2) a report of sexual contact before the age of 13 with an adult or person 5 years older, or sexual contact between the ages of 13–16 with a person 10 years older, or any age if threat of force or harm, and (3) a report of more than one episode of unprotected anal or vaginal sex within the past 3 months. Participants were recruited through advertising and outreach to bars, clubs, cruising areas, and community venues in addition to a variety of social media (e.g., Grindr, Growler, Scruff, Craigslist, and Facebook). Recruitment efforts were combined with other ongoing studies and health promotion initiatives (e.g., community health fairs, local Pride events, etc.) to prevent initial and potentially public endorsement of experienced CSA, thereby protecting individuals’ privacy and minimizing stigma associated with endorsing a history of CSA. All procedures were IRB approved by the institutional review boards of Fenway Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the University of Miami.

Clinical interviews used the MINI Clinical Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) to assess substance use dependence (SUD, inclusive of alcohol dependence), major depressive disorder (MDD), and anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, and social phobia) based on the DSM-IV and the SCID-IV Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) based on the DSM-IV. We aggregated anxiety disorders into one diagnostic category given our sample size and related power limitations. Participants answered questions regarding number of condomless sex episodes, and emergency room (ER) visits in the past 3 months. High risk sex was operationalized as number of self-reported episodes of condomless anal sex, not including those prescribed and ≥80% adherent to PrEP, treated as a count variable. Emergency room visits were dichomotized as 0 versus ≥1 visit given the distribution. Participants also completed sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing for syphilis, urethral and rectal gonorrhea, urethral chlamydia, and rectal chlamydia. Testing included serological testing for syphilis, using a nontreponemal antibody test with reactive serologies confirmed by treponemal-specific testing and nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) screening for urine and rectal swabs for chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. This health indicator was dichotomized resulting in testing positive for any of the tested STIs versus not testing positive for any.

Participants

Our sample (Table 1) of 290 MSM with histories of childhood sexual abuse were 68% white and 10% Hispanic. Over half reported an annual income of $20,000 or less and a quarter had a high school education or less. In the final sample, 9 participants from Boston and 4 from Miami reported being on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In relation to our health indicators, approximately half of the participants reported having 4 or more condomless sex encounters in the past 3 months. Close to 13% tested positive for one or more STI in the past 3 months (including syphilis, gonorrhea, urethral chlamydia, or rector chlamydia) and 21% reported 1 or more ER visits in the past 3 months.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Health Indicators (N=290)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age Mean (SD), Range | 37.95 (11.68), 18–67 |

| Race | |

| White | 201 (67.9%) |

| Black/African American | 66 (22.3%) |

| Asian | 9 (3.0%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 7 (2.4%) |

| Other (including missing and unknown) | 13 (4.4%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 87 (29.4%) |

| Annual Income | |

| ≤ $10,000 | 88 (30.3%) |

| $10,001–20,000 | 66 (22.3%) |

| $20,001-$40,000 | 53 (18.3%) |

| ≥$40,001 | 83 (28.6%) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High school diploma or GED | 73 (25.3%) |

| Some college | 106 (35.8%) |

| College degree (BA/BS)-some grad school | 71 (24.0%) |

| Graduate degree | 39 (13.2%) |

| Condomless sex episode quartiles in the past 3 months | |

| 0–1 episodes of high risk sex | 65 (22.6%) |

| 2–3 episodes of high risk sex | 84 (29.2%) |

| 4–7 episodes of high risk sex | 65 (22.6%) |

| ≥8 episodes of high risk sex | 74 (25.7%) |

| Any STI positive test (syphilis, gonorrhea, urethral chlamydia, rectal chlamydia) | 25 (12.8%) |

| Number of ER visits in the past 3 months | |

| 0 | 231 (79.4%) |

| 1 | 39 (13.4%) |

| 2 ≥3 |

16 (5.5%) |

| ≥3 | 5 (1.7%) |

To further characterize the sample, we present the frequencies of diagnoses and comorbidities in Table 2. One-third of the sample met criteria for SUD (n=97) and 31.3% (n=89) met current criteria for MDD. Forty-four percent met current criteria for PTSD (n=125). Approximately half of the sample (49.7%; n=147) met criteria for a current anxiety disorder, including: panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (16.1%; n=46), social phobia (18.5%; n=52), and GAD (29.7%; n=84). We also explored the extent diagnoses co-occurred and found that 28% of the sample met criteria for both PTSD and other anxiety disorders (n=83). Substance dependence (SUD) and PTSD co-occurred in 10.6% of the sample (n=15), and MDD and anxiety disorders co-occurred in 6.1% (n=18) of the sample. The other comorbidities occurred in less than 5% of the sample.

Table 2.

Participants’ Current Diagnoses and Comorbidities (N=290)

| Current Diagnoses | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Any Substance Use Disorder (including alcohol) | 133 (46.3%) |

| Any Substance Dependence (including alcohol) | 97 (32.8%) |

| Major Depressive Disorder diagnosis past 2 weeks | 89 (31.3%) |

| PTSD diagnosis, past 30 days | 125 (43.9%) |

| Any Anxiety Disorder (PD, PDA, Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, & GAD) | 147 (49.7%) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder, current | 84 (29.7%) |

| Any Panic Disorder (with and without Agoraphobia), current | 46 (16.1%) |

| Social Phobia, current | 52 (18.5%) |

| Current Comorbidities | n (%) |

| Any Substance Dependence (including alcohol) & Major Depressive Disorder | 3 (1.0%) |

| Any Substance Dependence (including alcohol) & PSTD | 15 (10.6%) |

| Any Substance Dependence (including alcohol) & Any Anxiety Disorder | 13 (4.4%) |

| Major Depressive Disorder & PSTD | 10 (3.4%) |

| Major Depressive Disorder & Any Anxiety Disorder | 18 (6.1%) |

| PTSD & Any Anxiety Disorder | 83 (28.0%) |

Analyses

We conducted descriptive statistics to describe the sample demographically and in regards to frequency of psychiatric diagnoses, comorbidities, and health indicators. We used chi-squares to assess bivariate relationships between current clinical diagnoses of SUD, MDD, PTSD, and anxiety disorders. We then used generalized linear and logistic regression to assess the additive and interactive relationships between a cumulative summary score (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) of the current clinical diagnoses current diagnoses and the three health-related indicators in the past 3 months. Given the over dispersion of the high risk sex variable, we used negative binomial regression accounting for deviance, rather than Poisson regression, to assess the additive relationship between clinical diagnoses and episodes of condomless anal sex. To investigate the potential interactive relationships between diagnoses, we conducted moderation analyses using both the PROCESS v3.1 macro (Hayes, 2017), which uses ordinary least square (OLS) regression, and Aiken & West’s methods (1991) to examine each bivariate diagnostic interaction (e.g., MDDxPTSD, PTSDxSUD) above and beyond the direct relationships to the three health-related indicators. Signficance level for all analyses was set a priori at 0.05 to balance the likelihood if Type I and Type II error. All models were run with and without four a-priori identified covariates: age, race (White, Black/ African American, and other), ethnicity (primary ethnic identification as Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino), and highest level of education (≤HS diploma, some college, college grad, and ≥some graduate school). Further, as suicidality is one of the most common reasons for ER visits among people with mood disorders (Pompili et al., 2010), to determine whether suicidality accounted for visiting the ER, we re-ran models in which visiting the ER was the dependent variable with a dichotomous current suicidal risk, assessed via clinical interview, as a covariate.

Results

Bivariate relationships were identified between SUD and MDD (χ2 = 4.85 p=0.028 ), MDD and PTSD (χ2 = 35.38 p=0.028, p<.001), MDD and any anxiety disorder (χ2 = 36.35, p<.001), and PTSD and any anxiety disorder (χ2 = 20.51, p<.001). We did not find significant relationships between SUD and PTSD (χ2 = 3.64 p=0.056 ) or between SUD and any anxiety disorder (χ2 =0.34 p=0.563). In our sample, 25.7% (n=76) of the sample did not meet criteria for any of the diagnoses, 26.4% (n=78) met criteria for 1 diagnosis, 21.6% (n=64) met criteria for 2 diagnoses, 20.3% (n=60) met criteria for 3 diagnoses, and 6.1% (n=18) met criteria for 4 diagnoses.

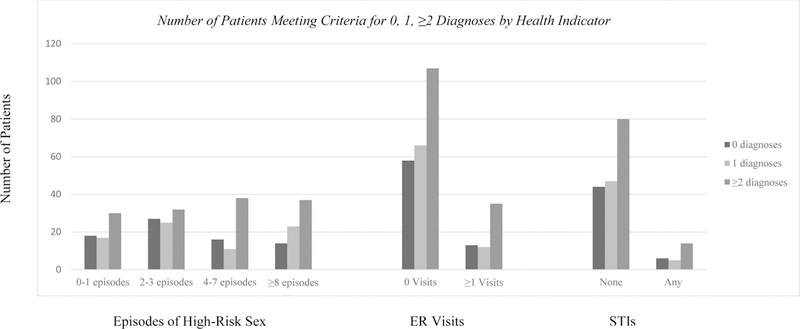

We then assessed the additive relationships between number of diagnoses (0–4) and the health indicators (depicted in Figure 1 and Table 3) as well as the interactions between each pair of diagnoses and three health indicators. We found a signficant effect of number of diagnoses on episodes of condomless sex, such that the percent change in the incident rate of episodes of condomless sex coincides with a 14% increase for every additional diagnoses (IRR=1.14, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.26, p=.009). However, we found no interactions between diagnoses in relation to condomless sex. We also found that number of diagnoses was associated with having gone to the emergency room (ER; OR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.60, p= .040). However, we found no interactions between diagnoses in relation to visiting the ER. We found no additive effect of diagnoses in relation to testing positive for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the past 3 months (0R=0.97; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.38, p= .857). Again, we did not find any interactions between diagnoses and testing positive for an STI. Results across analyses did not differ substantially when we controlled for race, ethnicity, and education, with one exception. Given that we did not find any interactions, to explore the relative relationships between specific diagnoses and health indicators, we ran three post-hoc multiple regression equations with all four diagnoses as independent variables and the health indicators as the three respective dependent variables. Using negative binomial regression, only SUD was associated with episodes of condomless sex (IRR=1.45, 95%CI: 1.07, 1.96, p=0.015), such that the percent change in the incident rate of episodes of condomless sex coincides with a 45% increase for those with SUD. No other diagnoses was significantly associated with condomless sex in the past 3 months. Using logistic regression, only MDD was associated with visiting to the ER (OR=3.00; 95% CI: 1.50, 6.01, p=.002), which we confirmed was not attributable to suicidality. No other diagnosis was significantly associated with visiting the ER in the past 3 months. Further, using logistic regression when all four diagnoses were entered as independent variables into the model, the presence of an anxiety disorder was the only diagnosis significantly associated with testing positive for an STI in the past 3 months (OR=2.94: 95% CI: 1.14, 7.62, p= .026). The post-hoc models predicting visiting the ER and positive STI results did not change significantly when we controlled for age, race (White, Black/African American, and other), ethnicity, and highest level of education (≤HS diploma, some college, college grad, and ≥some graduate school). Specifically, only MDD was significantly associated with going to the ER (OR=2.91; 95% CI: 1.44, 5.84, p= .003) and only the presence of an anxiety disorder was associated with a positive STI result (OR=3.42: 95% CI: 1.25, 9.38, p= .017) when covariates were included. When the model predicting episodes of condomless sex controlled for the aforementioned demographics, SUD was no longer significant (IRR=1.35, 95%CI: 0.99, 1.84, p=0.059). Notably, both education and race were signfiicantly associated with the number of episodes in this model. Specifically, those with some college, college degree-some graduate school, and a graduate degree all had lower incident rates of condomless sex compared to those with a high school education or less (IRR=0.57, 95%CI: 0.39, 0.83, p=0.003; IRR=0.59, 95%CI: 0.39, 0.89, p=0.012; and IRR=0.43, 95%CI: 0.26, .072, p=0.001, respectively). Additionally, those whose identified race was considered “other” in this analyses (neither white nor black/African American) had lower incident rates than white participans (IRR=0.52, 95%CI: 0.31, 0.88, p=0.014).

Figure 1.

Number of Patients Meeting Criteria for 0, 1, ≥2 Diagnoses by Health Indicator

Table 3.

Number of psychiatric diagnoses (0–4) predicting health indicators in the past 3 months (condomless sex episodes accounting for PrEP, STI acquisition, and having visited the ER) using negative binomial and logistic regression (n=290).

| Number of current diagnoses predicting number of sexual episodes without a condom using negative binomial regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesa | 1.14 (1.03,1.26) | .009 | |

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesb | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) | .017 | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | .342 | |

| Race (reference White) | 0.94 (0.68, 1.30) | ||

| Black/African American | 0.73 (0.47, 1.12) | .715 | |

| Other | .144 | ||

| Ethnicity (reference non-Hispanic) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.42) | ||

| Hispanic | .614 | ||

| Education (reference ≤ high school) | 0.75 (0.54, 1.03) | ||

| Some college | 0.75 (0.52, 1.08) | .077 | |

| College graduate | 0.67 (0.44, 1.03) | .119 | |

| Graduate School | .067 | ||

| Number of current diagnoses predicting odds of a positive STI test using logistic regression | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesa | 0.97 (0.682, 1.375) | .857 | |

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesb | 1.07 (0.74, 1.56) | .726 | |

| Age | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | .272 | |

| Race | 1.43 (0.74, 2.77) | .291 | |

| Ethnicity | 2.26 (0.93, 5.52) | .073 | |

| Education | 1.23 (0.79, 1.92) | .363 | |

| Number of current diagnoses predicting one or more ER visits using logistic regression | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesa | 1.27 (1.01, 1.60) | .040 | |

| Number of Syndemic Diagnosesb | 1.28 (1.01, 1.62) | .041 | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | .425 | |

| Race | 1.02 (0.65, 1.58) | .938 | |

| Ethnicity | 1.08 (0.57, 2.05) | .823 | |

| Education | 0.86 (0.64, 1.17) | .337 | |

Results without covariates.

Results with covariates, including age, race (White, Black/ African American, and other), ethnicity, and highest level of education (≤HS diploma, some college, college grad, and ≥some graduate school).

Although we did not specify income as a covariate apriori, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess whether controlling for annual income (≤ $10,000, $10,001–20,000, $20,001-$40,000, and ≥$40,001) affected our results. Income was directly associated with episodes of high risk sex, with those reporting annual income of ≥$40,001 having significantly fewer episodes of high-risk sex than those reporting ≤ $10,000 (reference group; IRR= 0.70, 95% CI: 0.51, 0.97, p=0.030) and lower likelihood of visiting the ER (OR=0.76; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.97, p=.030). Income was not directly associated with testing positive for an STI. Inclusion of income as a covariate did not significantly change the results of any of our presented models.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the additive and interactive relationships between comorbid current clinical psychiatric diagnoses, consistent with syndemic theory, in relation to three key health indicators (episodes of high-risk sex, visiting the ER, and testing positive for an STI) among a sample of MSM with developmental trauma. This study moves beyond measurement of syndemic problems using brief self-report measures (Halkitis et al., 2015; Mustanski et al., 2014; Stall et al., 2003) by investigating the relationships between clinically assessed diagnostic comorbidities in relation to key health indicators. In addition to assessing the prevalence of these psychiatric diagnoses among this high-risk group of MSM with histories of CSA, we also identified clinically meaningful bivariate relationships between syndemically-relevant diagnoses including MDD with SUD, PTSD, and anxiety disorders, as well as the comorbidity of PTSD and anxiety disorders. Consistent with existing syndemic literature, we identified additive relationships between number of syndemic clinical diagnoses and two health indicators: high-risk sex and visiting the ER in the past 3 months. However, we did not identify a relationship between number of diagnoses and testing positive for an STI. Further, we did not find any interactive relationships between diagnoses among this high-risk population and any of the health indicators, inconsistent with the synergistic relationship described in syndemic theory (Singer, 2000, 2006; Tsai et al., 2017). Given our sample size, it is possible that small to moderately sized interaction effects may have been missed; however, these results indicate that among this hard-to-recruit sample of MSM with histories of childhood sexual abuse, large interactive effects between current psychiatric disorders and our health indicators were not identified.

To better understand the results, our post-hoc analyses revealed differential associations of the psychiatric diagnoses with the three indicators. Specifically, with all four diagnoses entered, SUD was the only diagnoses significantly associated with episodes of condomless sex. However, the inclusion of demographic covariates resulted in SUD no longer being significantly associated with condomless sex, which appeared to be accounted for by education level. With all four diagnoses entered, MDD was the only diagnoses significantly associated with visiting the ER. While we confirmed this relationship was not accounted for by suicidality, it is possible that other depressive symptoms may be associated with this relationship or that depression contributes to avoidance of health-related self-care, resulting in utilization of emergency healthcare rather than preventative or early-stage treatments. Notably, despite evidence of people with anxiety disorders visiting the ER at higher than expected rates (Buccelletti et al., 2013; Demiryoguran et al., 2006), anxiety disorders were not significantly associated with visiting the ER in models that included all four diagnoses. Finally, anxiety disorders were the only diagnoses associated with testing positive for an STI, when all diagnoses were included. This is consistent with evidence indicating that anxiety interferes with safe sex practices (Hart & Heimberg, 2005; Hart, James, Purcell, & Farber, 2008), however, more work is needed in relation to other anxiety disorders. Across analyses, while we did not find evidence for specific combinations or diagnostic interactions in relation to our health indicators, which may have been limited by our sample size, we did identify that specific diagnoses were more associated with each of the health indicators. Together, these findings indicate that while a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses are associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in high risk sex and accessing the ER, specific diagnoses rather than comorbidities may be differentially associated with sexual risk and healthcare utilization. Our results also indicate that education may be an important factor in reducing episodes of high risk sex among this population, particularly for those with substance use disorders.

In addition to the contribution made by including clinical diagnoses and evaluating diagnoses both additively and interactively in relation to health indicators, this work offers a contribution to the literature because of the patient population. Developmental trauma, and childhood sexual abuse specifically, has long been conceptualized as a syndemic problem (Stall et al., 2003), that is known to disproportionately impact MSM compared to straight men (Lenderking et al., 1997). However, unlike the other syndemic problems, it involves a distal event(s) with developmental implications and variable impacts on individuals current functioning, ranging from minimally affecting an adult survivor to experiencing ongoing PTSD (Batchelder et al., in press). This investigation of current psychiatric diagnoses among a sample of MSM who have all experienced developmental trauma provides unique insight into the relationships between current psychiatric diagnoses and health indicators among this patient population at elevated risk for HIV acquisition (Banducci et al., 2014; Boroughs et al., 2015).

While this study contributes to the literature by demonstrating additive, but not interactive, relationships between clinical diagnoses and health indicators, this study has several limitations. First, although this sample is highly unique in that all participants have experienced CSA, as Stall has noted (Stall, Coulter, & Plankey, 2015), sample size may limit the ability to test interaction effects in many assessments of syndemics. However, Tsai and colleagues emphasize that the negative implications of type II error in relation to testing interaction effects in relation to syndemics are overstated (Tsai & Burns, 2015; Tsai & Venkataramani, 2016; Tsai et al., 2017). In this sample, it is possible that the lack of interactive findings may be due to the limited number of participants with specific comorbidities (e.g., only 3.4% of the sample met criteria for both PTSD and MDD). While our results do not rule out the presence of interaction effects between the tested psychiatric diagnoses and our three health indicators, our results are consistent with emerging literature where multiplicative relationships between syndemic problems and health-related outcomes have not been observed (e.g., Tomori et al., 2018; Tsai, 2018). It is possible that the use of diagnoses, rather than self-report assessments of syndemic risk, may have contributed to our lack of interactions in relation to health indicators, however, more work is needed. Further, all participants reported histories of developmental trauma, limiting the generalizability beyond this population. Notably, this was also a strength of the study, as it enabled the evaluation of PTSD, as well as other psychiatric diagnoses, among a sample of MSM with histories of developmental trauma. Additionally, the high levels of trauma across the sample may have limited the identification of the role of trauma on the health indicators. Further, this study was designed and initiated when the DSM-IV was in primary use, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the prevalence of depression, given the removal of the bereavement exclusion in the DSM-V. Furthermore, while this study involved testing for syphilis, urethral and rectal gonorrhea, urethral chlamydia, and rectal chlamydia, it did not involve testing for pharyngeal gonorrhea, which may have underestimated the rates of STIs in this sample. Finally, this study was cross-sectional, limiting the implications of the results, as establishing temporal precedence would support a more robust relationship between diagnoses and health care utilization. Ultimately, to better understand syndemics, replication of these findings is needed in similar and distinct patient populations, including those experiencing other psychiatric diagnoses, in relation to these and other health indicators.

Our results have several clinical implications that extend to population-level health management. First, consistent with other syndemic assessments, individuals with more problems, in this case psychiatric diagnoses, have a higher likelihood of engaging in high risk sex and utilizing costly emergency health care (O’Cleirigh et al., 2018). These results indicate that clinicians should be aware of the higher need for intervention among patients grappling with comorbid diagnoses, including encouraging engagement in preventative and early-stage healthcare. Further, while we did not find that specific diagnostic interactions were associated with our three health indicators, we did find that specific diagnoses were more associated with specific health indicators. Therefore, in addition to trauma treatment for MSM with developmental trauma histories, clinicians should prioritize empirically supported treatments for substance use disorders in relation to sexual risk reduction, empirically supported treatments for depression in relation to healthcare utilization, and empirically supported treatments for anxiety disorders in relation to STI prevention.

Conclusions

This study goes beyond syndemic investigations to date, which have assessed the additive relationships between brief self-reported psychosocial problems, by assessing both additive and interactive relationships between clinically assessed current psychiatric diagnoses and three health indicators among a unique sample of MSM with histories of developmental trauma. Using clinical psychiatric diagnoses, we found additive relationships between clinical diagnoses and condomless sex as well as visiting the ER, but not testing positive for a STI in the past 3 months. Notably, we did not find any interactive relationships between diagnoses in relation to our health indicators among this population at high risk for HIV acquisition. A larger sample is needed to assess multiple interactions. Further, longitudinal research is needed to investigate the relationships between comorbid psychiatric diagnoses over time in relation to high risk sex and health care utilization among this population. Ultimately, among MSM with histories of trauma, this work demonstrates that living with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses is additively associated with sexual risk taking and healthcare utilization. Continued work is needed to better understand how best to implement empirically supported interventions for comorbidities among this high need patient population.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank co-principle investigators Dr. Steven Safren (Boston site) and Dr. Gail Ironson (principle investigator at the Miami site) for their work on the larger study.

Disclosure: Funding was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health, R01MH095624 (PI O’Cleirigh); Author time (Batchelder) was supported, in part, by National Institute on Drug Abuse K23DA043418.

References

- Aiken LS & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, London, Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Hoffman EM, Lejuez CW, & Koenen KC (2014). The impact of childhood abuse on inpatient substance users: Specific links with risky sex, aggression, and emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(5), 928–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder A, Lounsbury DW, Palma A, Carrico A, Pachankis J, Schoenbaum E, & Gonzalez JS (2016). Importance of substance use and violence in psychosocial syndemics among women with and at-risk for HIV. AIDS Care, 28(10), 1316–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder AW, Ehlinger PP, Boroughs MS, Shipherd JC, Safren SA, Ironson GH, & O’Cleirigh C. (2017). Psychological and behavioral moderators of the relationship between trauma severity and HIV transmission risk behavior among MSM with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40(5), 794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder AW, Safren S, Coleman JN, Boroughs MS, Thiim A, Ironson G, Shipherd JC, & O’Cleirigh C. (in press). Indirect effects from childhood sexual abuse severity to PTSD: The role of avoidance coping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop TM, Maisto SA, & Spinola S. (2016). Cocaine use and sexual risk among individuals with severe mental illness. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 12(3–4), 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs MS, Valentine SE, Ironson GH, Shipherd JC, Safren SA, Taylor SW,… O’Cleirigh C. (2015). Complexity of childhood sexual abuse: predictors of current post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among adult men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1891–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccelletti F, Ojetti V, Merra G, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, Mangiola F, … Franceschi F. (2013). Recurrent use of the emergency department in patients with anxiety disorder. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 17 (1), 100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men, HIV AIDS, HIV by Group (Fact Sheet) (pp. 1–2). National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Demiryoguran NS, Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, Kiyan S, Ozbay D, Onur D, … Demir OF (2006). Anxiety disorder in patients with non-specific chest pain in emergency setting. Emergency Medicine Journal, 23, 99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer TP, Shoptaw S, Guadamuz TE, Plankey M, Kao U, Ostrow D, … Stall R. (2002). Application of syndemic theory to black men who have sex with men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of Urban Health, 89(4), 697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MR, Stall R, Plankey M, Wei C, Shoptaw S, Herrick A, … Silvestre AJ (2015). Effects of syndemics on HIV viral load and medication adherence in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS (London, England), 29(9), 1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Psaros C, Batchelder A, Applebaum A, Newville H, & Safren SA (2011). Clinician-assessed depression and HAART adherence in HIV-infected individuals in methadone maintenance treatment. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(1), 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Bub KL, Barton S, Moreira AD, & Stults CB (2015). A longitudinal investigation of syndemic conditions among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM: the P18 Cohort Study. AIDS and Behavior, 19(6), 970–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, & Heimberg RG (2005). Social anxiety as a risk factor for unprotected intercourse among gay and bisexual male youth. AIDS and Behavior, 9(4), 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, James CA, Purcell DW, & Farber E. (2008). Social anxiety and HIV transmission risk among HIV-seropositive male patients. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 22(11), 879–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis second edition a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Lim SH, Plankey MW, Chmiel JS, Guadamuz TT, Kao U, … Stall R. (2013). Adversity and syndemic production among men participating in the multicenter AIDS cohort study: a life-course approach. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce GF, Chan KS, Orlando M, & Burnam MA (2005). Mental health status and use of general medical services for persons with human immunodeficiency virus. Medical Care, 43(8), 834–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenderking WR, Wold C, Mayer KH, Goldstein R, Losina E, & Seage GR (1997). Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12(4), 250–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, (2006). Sexaul risk behavior among persons dually diagnosed with severe mental illness and substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(2), 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Safren SA, Coates TJ, … Stall RD (2015). The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 68(3), 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian A, Vilke GM, & Wilson MP (2013). Frequent emergency department visits are more prevalent in psychiatric, alcohol abuse, and dual diagnosis conditions than in chronic viral illnesses such as hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 45(4), 520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, Herrick A, Stall R, & Schnarrs PW (2014). A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Pantalone DW, Batchelder AW, Hatzenbuehler ML, Marquez SM, Grasso C, … Mayer KH (2018). Co-occurring psychosocial problems predict HIV status and increased health care costs and utilization among sexual minority men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Skeer M, Mayer KH, & Safren SA (2009). Functional impairment and health care utilization among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: the relationship with depression and post-traumatic stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(5), 466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okafor CN, Christodoulou J, Bantjes J, Qodela T, Stewart J, Shoptaw S, … Rotherman-Borus MJ (2018). Understanding HIV risk behavioral among young men in South Africa: A syndemic approach. AIDS & Behavior, https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1007/s10461-018-2227-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Cain D, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, … Pieterse D. (2013). Co-occurring psychosocial problems and HIV risk among women attending drinking venues in a South African township: A syndemic approach. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Giupponi G, Pycha R, Serafini G, Del Casale A, … Tatarelli R. (2010). Patients with mood disorders admitted for a suicide attempt to an emergency ward. Neuropsychiatrie, 24(1), 56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, & Endicott J. (2005). Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(6), 1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. (2000). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 28(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. (2006). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS, part 2: Further conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 34(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Coulter RWS, Friedman MR, & Plankey MW (2015). Commentary on “Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept” by A. Tsai and B. Burns. Social Science & Medicine, 145(1), 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Friedman M, & Catania JA (2008). Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. Unequal Opportunity: Health Disparities Affecting Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States, 1, 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, … Catania JA (2003). Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 939–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Bystritsky A, Sullivan G, Pyne JM, …Sherbourne CD (2005). Functional impact and health utility of anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Medical Care, 43(12), 1164–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomori C, McFall AM, Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Anand S, Balakrishnan P … Celentano DD (2018). Is there synergy in syndemics? Psychosocial conditions and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in India. Social Science & Medicine. 206, 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, (2018). Syndemics: A theory in search of data or data in search of a theory? Social Science & Medicine, 206, 117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, & Burns BF (2015). Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: a systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Mendenhall E, Trostle JA, & Kawachi I. (2017). Co-occurring epidemics, syndemics, and population health. The Lancet, 389(10072), 978–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A,C. & Venkataramani AS. (2016). Syndemics and Health Disparities: A Methodological Note. AIDS & Behavior, 20 423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]