Abstract

Recovery of burn patients may be impeded by mental health problems. By gaining a better understanding of the impact that psychological factors may have on hospital length of stay, providers may be better informed to address the complex needs of burn survivors through effective and efficient practices. This systematic review summarizes existing data on the adverse psychological factors for the length of burn patients’ hospitalization, and assesses the methodological quality of the extant literature on mental health conditions of burn survivors. A literature search was conducted in four electronic databases: PubMed, PsychINFO, Science Direct, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Results yielded reports published between 1980 and 2016. Methodological quality was assessed by using an 11-item methodological quality score system. Seventy-four studies were identified by search; 19 articles were eligible for analysis. Findings demonstrate paucity of evidence in the area. Reports indicate longer hospital stay among burn patients with mental health problems. Substance use was the most consistent mental-health predictor of longer hospital stay. Heterogeneity in data on mental health conditions rendered impossible estimation of effect sizes of individual psychological factors on length of hospitalization. Many studies over-relied on retrospective designs, and crude indicators of psychological factors. Findings indicate that mental health problems do have an impact on the trajectory of burn recovery by increasing the length of hospital stay for burn survivors. Inpatient mental health services for burn patients are critically needed. Prospective designs, and more sensitive psychological indicators are needed for future studies.

While the incidence of burn injuries has decreased in past decades, more people are surviving traumatic burn injuries than ever before.1 With survival rates on the rise, more people are experiencing the devastating physical and psychological aftermath of burn recovery. Of the estimated 486,000 burn survivors receiving medical care in the United States annually, about 40,000 require hospitalization.2 Psychological problems affecting hospitalized burn survivors, including psychosis, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use, have been sporadically shown to impede recovery and increase the length of hospital stay.3–5 There is a need for a systematic review of the existing data on the role that adverse psychological factors have on the length of burn survivors’ hospitalization to inform innovations in the field, including a possible justification of screening and treatment for psychological adversities in all hospitalized burn patients.

HOW ADVERSE MENTAL HEALTH FACTORS CAN IMPEDE BURN RECOVERY

Mechanisms impeding burn recovery among psychologically impaired patients may range from decreased hope or motivation to participate in one’s recovery or rehabilitation process to maladaptive behaviors including aggressive acts and agitated movements that may disrupt treatment. Independent of that, physiological effects of distress, such as the suppression of immune function, that can increase risk for infection, intensified pain, and delayed functional gains.6,7 Additionally, physiological responses to the burn trauma may include the release of stress hormones, thereby exacerbating psychological distress and increasing anxiety among acute care burn patients.8 During the “fight-or-flight” response to stress, epinephrine and norepinephrine are released causing vasoconstriction and inhibited digestion.9 These effects, along with a delayed initial inflammatory phase of wound healing, may increase healing times.6,10

Distress and Burn Recovery: A Knowledge Gap

Psychological problems among burn survivors include preburn mental health conditions and adverse psychological reactions to burn injuries.8 The latter include depression and anxiety; phobias; sleep disturbances; maladaptive/disruptive behaviors such as aggression or dissociation; psychosis related to drug/alcohol withdrawal; and the exacerbation of preexisting psychopathology.8 Postburn distress may predict longer and more difficult recovery5 as well as greater levels of physical and psychological impairment, slower rate of wound healing, and more surgeries.5,11 Furthermore, patients’ perception of burn severity has been found to predict wound healing rates.12 In essence, several studies implicate psychological distress as a factor that may extend and compromise the burn recovery process. No research to date has systematically reviewed extant evidence regarding the impact of psychological adversities on burn recovery and the mechanisms affecting length of stay (LOS). Such research is necessary, among other reasons, because burns are among the costliest health conditions to treat due to extended hospital stays, numerous operations, and the expense of burn care equipment and supplies.13 While significant variability in practice and cost of care may exist between burn units in different hospitals, the average hospital charge for burn survivors is $94,131, with daily charges ranging from $6,318 to $9,032.14

The Goal of the Present Study

This systematic review seeks to summarize and evaluate the extent of existing evidence regarding the impact of psychological adversities on hospital LOS of burn survivors. This study’s primary question is as follows: How do various psychological adversities influence burn inpatients’ LOS? Secondarily, this study assesses the methodological quality of existing research to inform future studies and promote best practices of burn care.

This study is timely given the rapid transformation of the U.S. health care system. Current legislation under the Affordable Care Act aims to reduce costs, increase access, and provide high quality medical care.15 While new directions may be taken in U.S. health care policy, the reduction of treatment costs is likely to remain an essential aspect of reform. A better understanding of the impact that psychological factors have on burn patients’ LOS is likely to further promote the integration of clinical mental health services as a standard concomitant practice to medical care on burn units. As a result, LOS could potentially be decreased by mediating the effects that stress has on wound healing and improving functional outcomes by way of enhanced treatment adherence.

METHODS

Search Selection and Criteria

Data Sources.

A computer-based search of the literature was conducted via four databases: PubMed, PsychINFO, Science Direct, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The following Boolean phrases were used: 1) “burn injury” AND “length of stay,” 2) “burn injury” AND “length of hospital stay” 3) “burn rehabilitation” AND “length of stay,” 4) “burn injury” OR “burn rehabilitation” AND “length of stay” AND psychological, and 5) “burn injury” AND “length of hospital stay.”

Inclusion Criteria.

Studies were included that 1) were quantitative research published in English, 2) targeted burn survivors who required hospitalization, 3) examined preburn psychiatric diagnoses, and/or postburn psychological problems measured at the onset of the hospitalization as an independent variable, and 4) reported hospital LOS as a dependent variable. Substance use-related disorders and self-inflicted injuries were considered relevant to one’s mental health and were included in this study. Given the lack of research in this area, inclusion criteria related to patient age, TBSA, and minimum baseline for LOS were not applied to the search.

Data Abstraction.

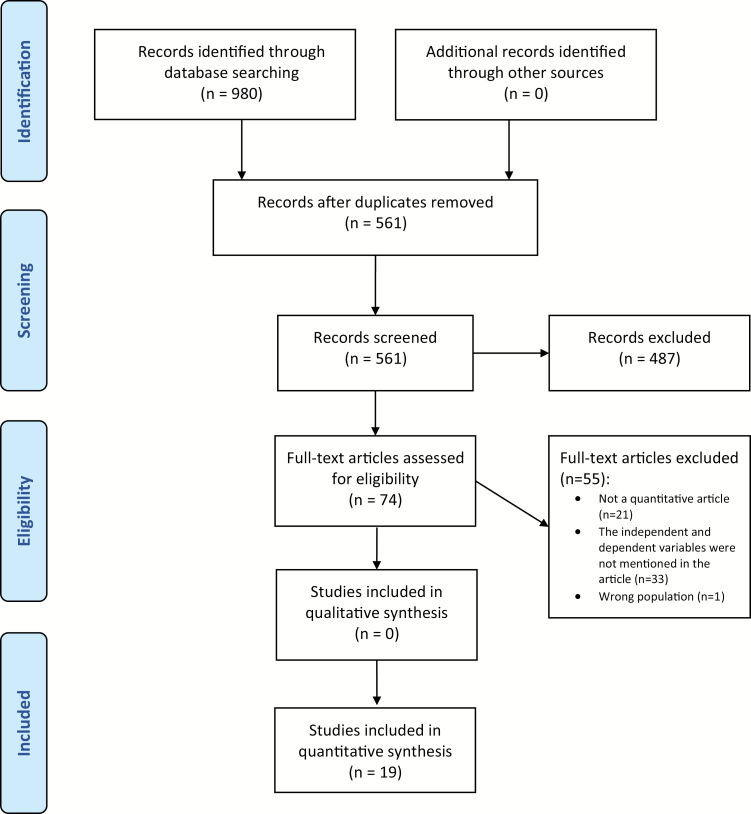

A structured review protocol was followed and articles that met the inclusion criteria were identified (Figure 1). The following information was abstracted from eligible articles: sample characteristics, psychological diagnoses or factors studied, and LOS. Psychological factors were then organized into the following thematic groups: 1) psychiatric conditions; 2) substance use disorders; and 3) self-inflicted injuries. Given the limited amount of existing literature, controlled and uncontrolled findings were abstracted.

Figure 1.

PRISMA structured review protocol diagram.

Outcome of Search Strategy

The search yielded a total of 980 articles. Duplicates removed, 561 articles remained and were screened by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies between reviewers were reconciled, resulting in 74 articles for independent full-text review by the two authors of this study. Of these articles, 55 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 21 articles were not quantitative research studies, 33 articles did not contain the variables of interest, and 1 article did not examine burn survivors. The remaining 19 articles that met study inclusion criteria were found to be published between 1984 and 2015; however, no date restrictions were applied for study inclusion. Given heterogeneity in data on psychological adversities, and on their impact on the LOS, it was not possible to estimate effect sizes of each type of mental health condition on hospital LOS. The empirical approaches and variables were too varied to conduct quantitative data synthesis. Lastly, methodological quality of each study was assessed by using an 11-item methodological quality score system presented as Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for assessing methodological quality and frequency distributions for each criterion

| Methodological Characteristic | Scoring Options (Maximum Total Score = 20 Points) | Distribution of Characteristics Among Included Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency n (%) | Reference No(s). | ||

| (A) Specification of psychological factors | Not specified/collapsed: 1 | 0 (0%) | – |

| At least one factor specified (with or without more factors collapsed): 2 | 13 (68%) | 5, 18, 21–24, 26–32 | |

| Multiple factors specified independently: 3 | 6 (32%) | 4, 16, 17, 19, 20, 25 | |

| (B) Diagnostic criteria for psychological factors | Not specified: 0 | 5 (26%) | 21, 28–31 |

| Specified diagnostic criteria, or measurement protocol: 1 | 14 (74%) | 4, 5, 16–20, 22–27, 32 | |

| (C) Validity/reliability of psychological measures reported | Not reported: 0 | 17 (89%) | 4, 16–19, 21–32 |

| Only validity or only reliability reported: 1 | 0 | – | |

| Both validity and reliability reported: 2 | 2 (11%) | 5, 20 | |

| (D) Theoretically informed research study | Not presented: 0 | 14 (74%) | 16–19, 21–26, 29–32 |

| Presented: 1 | 5 (26%) | 4, 5, 20, 27, 28 | |

| (E) Control group presence and assignment method | No control group: 0 | 6 (32%) | 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29 |

| Nonrandomized control condition: 1 | 8 (42%) | 5, 16–18, 21, 25, 30, 32 | |

| Randomized control group or matched controls: 2 | 5 (26%) | 4, 19, 23, 28, 31 | |

| (F) Sample size | Undetermined: 0 | 0 (0%) | – |

| <100: 1 | 5 (26%) | 4, 20, 26, 28, 30 | |

| ≥100 to <300: 2 | 6 (32%) | 5, 19, 21, 23–25 | |

| ≥300: 3 | 8 (42%) | 16–18, 22, 27, 29, 31, 32 | |

| (G) Sample design | Convenience/nonprobability: 0 | 19 (100%) | 4, 5, 16–32 |

| Random/probability but not population-representative: 1 | 0 (0%) | – | |

| Random/probability and population-representative: 2 | 0 (0%) | – | |

| (H) Sample demographics presented | Not presented: 0 | 0 (0%) | – |

| Only one demographic characteristic presented: 1 | 2 (11%) | 19, 26 | |

| Multiple demographic characteristics presented: 2 | 17 (89%) | 4, 5, 16–18, 20–25, 27–32 | |

| (I) Data analysis | Univariate/descriptive/unspecified: 1 | 2 (11%) | 18, 30 |

| Bivariate/ANOVA: 2 | 12 (63%) | 4, 21–29, 31, 32 | |

| Multiple/logistic regression/multivariate/ANCOVA: 3 | 5 (26%) | 5, 16, 17, 19, 20 | |

| (J) Statistically controlled for effects of demographics and/or medical confounds on length of stay or other outcomes | No controls: 0 | 9 (47%) | 18, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32 |

| Controlled only for demographics (age, gender, etc.): 1 | 0 (0%) | – | |

| Controlled for demographics and medical confounds (eg, TBSA, inhalation injury, etc.): 2 | 10 (53%) | 4, 5, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 28, 31 | |

| (K) Design type | Retrospective: 1 | 17 (89%) | 4, 16–19, 21–32 |

| Prospective: 2 | 2 (11%) | 5, 20 | |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

RESULTS

Alcohol and drug use were the most commonly studied factors in 10 studies, followed by self-inflicted injuries and/or suicidal intent in eight studies. Four studies reported psychiatric disorders/diagnoses as an aggregate term inclusive of multiple mental health conditions. Two studies demonstrated the significance of impact of “any psychiatric disorder” by aggregating all diagnoses that were also individually reported. Of the individual diagnoses that were examined, two articles studied depression and two studied psychosis. The remaining conditions were each examined once among the 19 articles: psychological problems of somatic etiology, mental retardation, character disorder, schizophrenia, senility, PTSD, high psychological distress, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. A summary of these results is presented in Table 2. Table 3 presents the scoring results for the methodological quality of each study using the 11-item methodological quality score system presented in Table 1.

Table 2.

The impact of psychological factors on burn length of stay

| Psychological Factor | No. of Articles | Number of Additional Days Spent in Hospital Due to Psychological Factor | Freq. of Factor | N Size | Admissions | Reference No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological diagnoses | |||||||

| Psychiatric condition of somatic etiology | 1 | NS | – | 15 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Mental retardation | 1 | NS | – | 7 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Character disorder | 1 | * | +16.2a,b,f | 33 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Depression | 2 | NS | – | 24 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| NS | –a,b,c,d | 8 | 51 | 190 | 4 | ||

| Sociopathy | 1 | NS | – | 10 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Schizophrenia | 1 | * | +26.3a,b,f | 9 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Psychosis | 2 | NS | – | 2 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| * | +20.5a,b,c,d,g | 9 | 51 | 190 | 4 | ||

| Senility | 1 | * | +24.7a,b,f | 10 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1 | * | Increased LOS but length unreporteda | 8 | 95 | 274 | 20 |

| High psychological distress | 1 | * | +18a,b,f | 9 | 100 | 107 | 5 |

| Undiagnosed disorder | 1 | NS | – | 6 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| ADHD | 1 | * | +4a,b,c,d,g | 35 | 278 | 278 | 21 |

| Psychiatric disorders or diagnoses as a defined aggregate term inclusive of multiple diagnoses | 4 | * | +10a,b,f | 126 | 311 | 2,123 | 17 |

| * | +14.85a,b,f | 29 | 100 | 107 | 5 | ||

| * | +42% increasea,b,c,e,f | 896 | 31,338 | 31,338 | 16 | ||

| NR | +17.1f | 24 | 1,524 | 1,524 | 18 | ||

| “Any Psychiatric Problem (or Diagnosis)” all disorders combined | 2 | * | Aggregate LOS impact not reported in study, only individual differences which are reported above | 104 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| 18 | 51 | 190 | 4 | ||||

| Substance use disorders | |||||||

| Substance dependence | 1 | * | Increased but LOS unreporteda,b | 56 | 311 | 2,123 | 17 |

| Alcohol at injury | 1 | NS | – | 38 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Alcohol-related burns | 1 | * | +4.6a,b,c,d,f | 182 | 1,293 | 1,538 | 22 |

| Positive blood alcohol levels | 1 | NS | – | 70 | 225 | 24 | |

| Elevated BAC | 4 | * | +13.27a,b,c,d,e,f | 24 | 146 | 258 | 23 |

| NS | – | 16 | 200 | 854 | 19 | ||

| * | +36% increasea,b,c,e,f | 1,814 | 31,338 | 31,338 | 16 | ||

| NS | – | 61 | 218 | 624 | 25 | ||

| Alcoholism | 2 | * | +9.9f | 70 | 225 | 24 | |

| * | +1 day for each 1% increase of TBSAa,f | 30 | 81 | 108 | 26 | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 1 | NR | +9f | 50 | 442 | 442 | 27 |

| Drug abuse | 2 | * | +20% increasea,b,c,e,f | 1,021 | 31,338 | 31,338 | 16 |

| * | +10.8a,b,c,f | 42 | 218 | 624 | 25 | ||

| Cannabis | 1 | NS | – | 2,586 | 17,080 | 112,000 | 32 |

| Heroin addiction | 1 | NS | – | 20 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Drug and alcohol abusers | 1 | NS | – | 11 | 218 | 624 | 25 |

| Other substance abuse | 1 | NS | – | 3 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Self-inflicted injuries | |||||||

| Suicidal intent | 1 | NS | – | 16 | 200 | 854 | 19 |

| Self-inflicted injury | 7 | NS | – | 123 | 311 | 2,123 | 17 |

| NR | +26 or 3× as many daysf | 65 | 2,275 | 2,275 | 30 | ||

| * | +75.5a,b,c,d,g | 8 | 51 | 190 | 4 | ||

| * | +6.7f | 35 | 96 | 2,996 | 29 | ||

| NS | – | 593 | 30,382 | 30,382 | 31 | ||

| NR | +39.7f | 33 | 1,524 | 1,524 | 18 | ||

| * | +6a,b,c,g | 36 | 72 | 782 | 28 | ||

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BAC, blood alcohol content; LOS, length of stay; NS, no significant results; NR, significance not reported.

The following notation is used throughout the above chart:

*Significant results.

aControlled for burn size and/or severity.

bControlled for age.

cControlled for gender.

dControlled for type of burn.

eControlled for inhalation injury.

fMean comparison.

gMedian comparison.

Table 3.

Methodological quality scores for each study

| Study | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | MQS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry et al., 1984 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Fauerbach et al., 1997 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Haum et al., 1995* | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0* | 1 | 10 |

| Holmes et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Horner et al., 2005 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 13 |

| Jehle et al., 2015* | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0* | 1 | 12 |

| Jones et al., 1991 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Mangus et al., 2004* | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0* | 1 | 10 |

| Powers et al., 1994* | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0* | 1 | 12 |

| Reiland et al., 2006* | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0* | 1 | 10 |

| Silver et al., 2008 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Swenson et al., 1991 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Tarrier et al., 2005 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Thombs and Bresnick, 2008 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Thombs et al., 2007 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| van der Does et al., 1997 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Wallace and Pegg, 1999* | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0* | 1 | 8 |

| Wisely et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Wood et al., 2014* | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0* | 1 | 11 |

LOS, length of stay; MQS, methodological quality score.

A, specification of psychological factors; B, diagnostic criteria for psychological factors; C, validity/reliability of psychological measures reported; D, theoretical framework presented; E, control group (no psychological factors), assignment method; F, sample size; G, sample design; H, sample demographics presented; I, data analysis; J, controlled/adjusted for the effects of demographics and/or medical confounds; K, design type.

*Presents relevant adjustment characteristics, eg, age and TBSA; however, the analyses (bivariate) do not use them to adjust the effects of conditions on LOS.

Psychiatric Diagnoses and Psychological Adversities

Eight studies reported the impact of mental health disorders on burn patients’ hospital LOS. One prospective5 and three retrospective studies16–18 found that multiple psychiatric disorders defined as an aggregate term have a statistically significant impact on LOS. Specifically, Thombs et al16 controlled for burn size, inhalation injury, age, and gender, and found that patients with psychiatric diagnoses had an average LOS 42% longer than those without. van der Does et al17 and Wisely et al5 controlled for burn size and age and found that mental health diagnoses increase hospital LOS by an average of 10 and 14.85 days, respectively. Wood18 reported that mean LOS among burn survivors with a psychiatric diagnosis was 17.1 days greater, although statistical significance was not reported. None of these articles reported the effects of individual psychiatric disorders on LOS, and none of the articles discussed the relationship between number of psychiatric disorders and LOS.

Berry et al19 reported that individual diagnoses, including psychological problems of somatic etiology, mental retardation, undiagnosed but suspected disorders, depression, sociopathy, and psychosis, taken individually, had no statistically significant impact on LOS. Tarrier et al4 controlled for burn size, age, gender, and the type of burn and like Berry et al,19 found that depression alone did not have a statistically significant impact on LOS; however, patients with psychosis were hospitalized 20.5 days longer, on average, compared with matched controls; the difference was statistically significant. According to Berry et al,19 patients with character disorder, senility, and schizophrenia stayed in hospital significantly longer by 16.2, 24.7, and 26.3 days, respectively, with burn size and age controlled for. PTSD was also found to have a statistically significant impact on LOS in a prospective study.20 Another prospective study found that high levels of psychological distress demonstrated a statistically significant effect on LOS by an additional 18 days, on average, controlling for burn size and age.5 Lastly, in a study done on the pediatric population, burn patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder were in the hospital approximately 4 days longer, controlling for burn severity, age, gender, and burn type.21

Alcohol and Drug Use

Ten retrospective studies reported impacts of alcohol and/or drug use on burn patients’ LOS. Patients identified as “substance-dependent” had an increase in LOS compared with controls; however, the difference in days was not reported.17 Alcohol use at time of injury did not show statistical significance with differences in LOS19; however, patients with alcohol-related burns spent, on average, 4.6 additional days in the hospital.22 Studies that examined blood alcohol content at time of admission found mixed results, one study found a statistically significant difference of 13.27 days in the hospital,23 while another did not find a significant difference.24 Two studies identifying patients who “abuse alcohol” did not find patients staying in the hospital longer19,25; however, a third article did find that burn patients who abused alcohol had a 36% increase in average LOS when controlling for burn size, age, and gender.16 Patients with “alcoholism” were found to have statistically significant increases in hospital stay, 9.9 days in one article24 and one additional day for each 1% increase in TBSA in another.26 Jones et al26 add that patients with alcohol disorders use more hospital resources than those without, staying in the hospital for nearly twice as long when burn size was controlled. Lastly, Powers et al27 found patients with an alcohol use disorder to stay in the hospital for nine additional days, on average; however, significance was not reported.

Two of five studies that examined drug use on LOS reported significant differences. Silver et al23 reported a 20% average increase in LOS among patients who abused drugs, controlling for burn severity, age, gender, burn type, and inhalation injury. Swenson et al25 found an average increase of 10.8 days. Other studies that examined the impact of cannabis, heroin, drug and alcohol abuse combined, and other substance abuse did not find significant LOS differences.

Self-inflicted Injuries

Eight retrospective studies reported LOS among patients whose burn injuries were self-inflicted. Findings varied among three studies that had significant results, with patients staying 6, 6.7, and 75.5 more days in the hospital, on average, compared with burn patients who did not self-inflict their injuries.4,28,29 Two studies that did not report statistical significance found LOS increased by 26 days30 and 39.7 days.18 The remaining three articles did not find significant differences in LOS among self-inflicted injured patients.

Theoretical Framework

Of 19 articles, only 5 specified a theoretical framework to guide their empirical investigation. The remaining articles were atheoretical.

Research Paradigm and Study Design

All studies in this review used a quantitative research paradigm. Nearly all relied on a retrospective study design (n = 17) and medical chart abstraction. Two studies used a prospective design (Table 4).

Table 4.

Research design among included studies

| Distribution of Studies by Research Design | ||

|---|---|---|

| Research Design | Frequency, n (%) | Reference No. |

| Retrospective | 17 (89%) | 4, 16–19, 21–32 |

| Prospective | 2 (11%) | 5, 20 |

Sample Size, Sampling Methods, and Sample Description

The sample size varied among the 19 studies ranging from nationally represented data sets with samples over 30,00016,31 to samples of 100 patients. Twelve retrospective studies had large initial sample sizes (n > 300), three of which used the American Burn Association National Burn Repository (ABA-NBR) with a sample of over 30,000 patients from 70 burn units across the United States.16,31,32 The two prospective studies used nonprobability convenience samples with sizes of 27420 and 100.5 The most common sampling method in the retrospective studies was a nonprobability homogenous purposive sampling strategy by medical chart abstraction.

Across the reviewed articles, sample mean age of included patients ranged from 34 to 51, and the overall patient age range across the study samples was 16 to 89. None of the included studies presented specific data on pediatric or geriatric patient populations. The majority of patients in the included studies was male (57–72%, across the articles). Studies did not report nationality of patients, or which proportion was comprised of U.S. citizens. Across studies, reported mean LOS within patient subgroups ranged from 10 to 47 days, on average, and mean TBSA across study samples ranged from 4% to 12%.

Data Analytic Methods

Most of the reviewed articles (12 of 19) relied on bivariate data analytic methods, such as Mann–Whitney U test, t-test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Five studies used more advanced analytic methods such as logistic regression, multiple regression, or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). One article reported a descriptive account of average LOS among patients with self-inflicted and accidental burns without statistically testing the significance of the difference. None of the articles used causal modeling approaches, such as structural equation modeling, capable of explaining more complex mechanisms resulting in prolonged hospital stay among patients with psychological adversities.

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to assess the general impact of psychological factors on hospital LOS for burn survivors. The studies which aggregated across psychological diagnoses produced the most consistent, statistically significant results indicating that adverse psychological factors, as a whole, do increase LOS.5,16–18 Among the individual psychological factors studied, substance use, reported in 10 of 19 reviewed studies, consistently resulted in extended hospital LOS. However, the reviewed studies stopped short of specifying substance use-related mechanisms responsible for increased LOS. Hospital LOS is often associated with the amount of time it takes for wounds to heal4; therefore, one must consider specific causal chains involving biological, behavioral, and psychological factors that conjointly affect the speed of wound healing. The immunosuppressive effect of substance use is known in the literature,7,26,33 and can have a direct, negative influence on wound healing.34 Combined findings from reviewed studies tentatively suggest that substance use among burn survivors may affect wound healing in conjunction with mental health problems. Alternatively, substance use may operate as a maladaptive coping strategy secondary to mental health problems. Further research should test more elaborate causal models that could uncover specific mechanisms by which psychological problems and substance use affect hospital LOS.

Studies of self-inflicted burn injuries found significantly greater LOS among patients with self-inflicted burns, controlling for burn size, age, gender, and type/etiology of burn.4 Two authors additionally controlled the effect of “self-inflictedness” for mental health disorders, and discovered that a self-inflicted nature of injury alone does not account for extended LOS.17,31 It is, therefore, critical to carefully assess and address mental health problems among all the patients whose burns are possibly self-inflicted. Also important is the fact that self-inflicted injuries tend to result in larger burn sizes compared with accidental injuries,30 which would additionally account for longer wound healing times, over and above the mental health-related mechanisms.

Reviewed studies relied on a variety of data analytic methods and control variables. Studies that used regression models (5 of 19) controlled for factors including age, gender, type and size of burn, and inhalation injury, each of which influence LOS. Given that medical comorbidities, such as diabetes,26 can play a major role in wound healing times and could ultimately influence LOS, future research should consider controlling for such factors. One study found that the psychology team responsible for capturing data failed to collect key biological information such as medical comorbidities or inhalation injury.5 This introduces potential confounding effects and left-out variable error. Future studies should consistently control for potentially confounding variables including medical conditions that may influence both recovery and patients’ psychological stability.

Methodological Limitations

The majority of reviewed articles relied on retrospective data abstraction from medical records. Such approach may introduce errors and problems of missing/incomplete data.29 Moreover, data in medical charts may be collected using measurement protocols that are not sensitive enough to allow for meaningful data analysis.17,19 Additionally, interpretation of data from medical charts may bring in subjective perspectives of chart reviewers.19 All of the above are likely factors contributing to the considerable disparity of outcome results observed across the reviewed studies.35 Future studies examining psychological aspects of burn recovery should use prospective designs. Those projects still relying on retrospective chart abstraction should engage at least two independent clinicians in data abstraction, to assure interrater reliability.

The broad variety, and overall crudeness, of the measurement approaches to psychological conditions across reviewed studies limits the potential for quantitative comparison of the effects of psychological adversities on hospital LOS; therefore, this review did not employ meta-analytic approach. Future studies of psychological adversities among burn survivors should use more uniform and sensitive measurement strategies, including those that document not only the presence of the mental health diagnoses but also the intensity of psychological symptoms.

While many reviewed studies had large overall sample sizes, much smaller fractions of these samples had data on psychological problems. Of 19 studies, 5 analyzed subsamples with data on psychological problems that were smaller than 100, and 6 with less than 300. Even smaller subsamples, some smaller than 10, represented subgroups of patients with specific mental health conditions.4,19 This limited the possibility to compare effects of various psychological adversities on hospital LOS.19 Two studies used large samples (N > 30,000) from the ABA-NBR. However, one study suspected that the ABA-NBR underreports psychiatric diagnoses: Only 23% of patients with self-inflicted burns were listed with mental health adversities, which is well below the rate reported in any other single study.31 Furthermore, while these data represent 70 burn units across the United States, the ABA-NBR does not account for potential differences among burn care and management/practices among different hospitals. Consequently, generalizability of this review’s findings must be taken with caution.20

Another limitation and important area for future research noted among several studies is the need for identifying and understanding the specific, psychologically determined mechanisms that affect LOS. The following potential mechanisms representing proximal consequences of psychological problems emerged across the reviewed studies: 1) self-destructive behavior including agitated movements that may disrupt skin grafts, pulling out intravenous lines, fighting the respirator, or refusing to eat; 2) time needed to treat psychological disorders; 3) diminished mental capacity for self-care; and 4) noncompliance with nursing or rehabilitation regimens. Frequently, reviewed studies also highlighted additional factors that can lead to longer LOS that should also be considered in future research. These include 1) decreased social support to assist with care; 2) greater TBSA burns resulting in additional surgeries or complications with infections; 3) inhalation injury; 4) poor nutrition and lack of sleep which are necessary components for healing; and 5) preexisting poor health.19,20,26,30,36 One study that did examine mechanisms for extended LOS found that patients with low treatment adherence and patients who required more levels of psychological treatment had longer LOS. It was also found that eight of nine delayed discharges due to social factors were accounted for by patients with a psychiatric diagnosis.5 Additionally, it is important to note that all but five articles were atheoretical. Given that theory considers what is already known to explain existing behavior or predict future behavior, its use to predict causal relationships between predictor variables on outcomes can strengthen the design of future research.37

Lastly, because of the cross-sectional nature of most findings, there is reduced ability to make causal inference between psychological adversities and the characteristics of burn recovery that contribute toward LOS. The dearth of extant research did not allow for grouping studies by types of psychological adversities and pursuing between-group analyses. Despite these limitations, this review provides clear evidence that psychiatric conditions among burn patients do consistently increase LOS and therefore, integrated clinical solutions must be considered to address the mental health needs of burn survivors.

Implications for Practice

Given that survival rates of burn injuries have significantly improved in the United States, the need for an emphasis on rehabilitation and recovery is paramount.38 The devastating physical and emotional effects of burn injuries demand integrated models for care that provide concomitant physical and mental health treatment39 to promote patient outcomes, specifically wound healing and maximized functional gains, that together, can ultimately prevent extended hospital LOS. Such integrated care models would involve health care professionals, including surgeons; occupational, physical, and respiratory therapists; speech and language pathologists; nurses; and nutritionists; licensed mental health professionals, including clinical social workers; psychiatrists, and psychologists; and spiritual care providers, including chaplains. Such models of integrated care should also consider the value in other staff who provide direct patient care, including nursing and rehab aides, who can be trained to provide psychosocial support toward patients when assisting with patients’ health care. While such interventions would not be clinical in nature, training all medical and direct care staff in basic attending skills and providing a supportive presence toward patients can help achieve positive patient outcomes. Patients who receive coordinated medical and psychological care from medical and mental health professionals, respectively, have the potential to increase their ability to cope with a burn experience and sustained injuries. Additionally, there is a potential for an increase in one’s level of hope or motivation which can affect the ability to participate and engage in the recovery and rehabilitation process.

Burns are among the costliest disorders to treat13 and when psychological factors delay recovery, patients require disproportionately more resources.4 The provision of an integrated care model on burn units would not only benefit the recovery of burn survivors by improving care quality, but such improved outcomes could also be economically beneficial to patients, insurance providers, and health care institutions.

CONCLUSIONS

This review indicates the need for additional research regarding the impact that psychological factors have on burn recovery. Future research should strengthen theoretical frameworks in this area. Such research can inform burn units of best practices for assessing and addressing problematic psychological factors. While some studies have made the connection between psychological adversities and direct determinants of LOS, the precise mechanisms contributing to longer LOS remain unclear.17 Future research is needed to include larger homogenous samples of specific psychological diagnoses while controlling for known contributing factors for longer LOS. Burn units offer an opportunity for promising psychosomatic research17 and with such research, future studies may test intervention models for this unique population. Efforts to screen, assess, and treat potential psychological needs of burn patients, therefore, should be considered a standard practice during the acute and recovery phases of burn rehabilitation.

REFERENCES

- 1. McKibben JB, Ekselius L, Girasek DC et al. Epidemiology of burn injuries II: psychiatric and behavioural perspectives. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009;21:512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Burn Association. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2016 fact sheet 2016, accessed 11 Feb. 2017; available from http://www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php; Internet.

- 3. Dissanaike S, Rahimi M. Epidemiology of burn injuries: highlighting cultural and sociodemographic aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009;21:505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tarrier N, Gregg L, Edwards J, Dunn K. The influence of pre-existing psychiatric illness on recovery in burn injury patients: the impact of psychosis and depression. Burns 2005;31:45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wisely JA, Wilson E, Duncan RT, Tarrier N. Pre-existing psychiatric disorders, psychological reactions to stress and the recovery of burn survivors. Burns 2010;36:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gouin J, Kiecolt-Glaser J. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and mechanisms. Immunology Allergy Clin North Am 2011;31:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wisely J. The impact of psychological distress on the healing of burns. Wounds UK 2013;9:14–7; available from http://www.wounds-uk.com/pdf/content_10941.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klinge K, Chamberlain DJ, Redden M, King L. Psychological adjustments made by postburn injury patients: an integrative literature review. J Adv Nur 2009;65:2274–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freberg LA. Discovering behavioral neuroscience, an introduction to biological psychology. 3rd ed. Boston (MA): Cengage Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nature Rev Immunol 2005;5:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fauerbach JA, Lezotte D, Hills RA et al. Burden of burn: a norm-based inquiry into the influence of burn size and distress on recovery of physical and psychosocial function. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26:21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson ER, Wisely JA, Wearden AJ, Dunn KW, Edwards J, Tarrier N. Do illness perceptions and mood predict healing time for burn wounds? A prospective, preliminary study. J Psychosom Res 2011;71:364–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sahin I, Ozturk S, Alhan D, Acikel C, Isik S. Cost analysis of acute burn patients treated in a burn centre: the Gulhane experience. Annals Burns Fire Disasters 2011;24:9–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Burn Association. National burn repository: report of data from 2006–2015 2016, accessed 11 Feb. 2017; available from http://www.ameriburn.org/2016%20ABA%20Full.pdf; Internet.

- 15. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affairs 2008;27:759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, Diallo A, Milner SM. The effects of preexisting medical comorbidities on mortality and length of hospital stay in acute burn injury. Annals Surg 2007;245:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Does AJ, Hinderink EM, Vloemans AF, Spinhoven P. Burn injuries, psychiatric disorders and length of hospitalization. J Psychosom Res 1997;43:431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wood R. Self-inflicted burn injuries in the Australian context. Australas Psychiatry 2014;22:393–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berry CC, Patterson TL, Wachtel TL, Frank HA. Behavioural factors in burn mortality and length of stay in hospital. Burns 1984;10:409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fauerbach JA, Lawrence J, Haythornthwaite J et al. Preburn psychiatric history affects posttrauma morbidity. Psychosomatics 1997;38:374–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mangus RS, Bergman D, Zieger M, Coleman JJ. Burn injuries in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Burns 2004;30:148–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmes WJ, Hold P, James MI. The increasing trend in alcohol-related burns: it’s impact on a tertiary burn centre. Burns 2010;36:938–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silver GM, Albright JM, Schermer CR et al. Adverse clinical outcomes associated with elevated blood alcohol levels at the time of burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2008;29:784–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haum A, Perbix W, Häck HJ, Stark GB, Spilker G, Doehn M. Alcohol and drug abuse in burn injuries. Burns 1995;21:194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swenson JR, Dimsdale JE, Rockwell E, Carroll W, Hansbrough J. Drug and alcohol abuse in patients with acute burn injuries. Psychosomatics 1991;32:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones JD, Barber B, Engrav L, Heimbach D. Alcohol use and burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1991;12:148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powers PS, Stevens B, Arias F, Cruse CW, Krizek T, Daniels S. Alcohol disorders among patients with burns: crisis and opportunity. J Burn Care Rehabil 1994;15:386–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Horner BM, Ahmadi H, Mulholland R, Myers SR, Catalan J. Case-controlled study of patients with self-inflicted burns. Burns 2005;31:471–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reiland A, Hovater M, McGwin G, Rue LW, Cross JM. The epidemiology of intentional burns. J Burn Care Res 2006;27:276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wallace KL, Pegg SP. Self-inflicted burn injuries: an 11-year retrospective study. J Burn Care Rehabil 1999;20:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thombs BD, Bresnick MG. Mortality risk and length of stay associated with self-inflicted burn injury: evidence from a national sample of 30,382 adult patients. Critical Care Med 2008;36:118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jehle CC Jr, Nazir N, Bhavsar D. The rapidly increasing trend of cannabis use in burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2015;36:e12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Friedman H, Newton C, Klein TW. Microbial infections, immunomodulation, and drugs of abuse. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16:209–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res 2010;89:219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wisely JA, Hoyle E, Tarrier N, Edwards J. Where to start? Attempting to meet the psychological needs of burned patients. Burns 2007;33:736–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kamolz LP, Andel H, Schmidtke A, Valentini D, Meissl G, Frey M. Treatment of patients with severe burn injuries: the impact of schizophrenia. Burns 2003;29:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunn DS, Elliott TR. The place and promise of theory in rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychology 2008;53:254–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stoddard FJ Jr, Ryan CM, Schneider JC. Physical and psychiatric recovery from burns. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2015;38:105–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Network for Burn Care. National burn care standards 2013, accessed 11 Feb. 2017; available from http://www.britishburnassociation.org/downloads/National_Burn_Care_Standards_2013.pdf; Internet.