Abstract

Background/Aims:

The available studies on Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence among healthy asymptomatic population across Saudi Arabia suffers from significant limitations. We conducted this large population-based study to estimate the H. pylori seropositivity rate among apparently healthy children in Saudi Arabia, using anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG serology tests, and to study the influence of H. pylori infection on growth.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study to screen apparently healthy school aged Saudi children (aged 6–15 years), attending primary and intermediate schools in Riyadh between 2014 and 2016, for H. pylori seropositivity by checking for the presence of anti-H. pylori IgG and IgA antibodies in serum specimens.

Results:

Out of 3551 serum specimens, 1413 cases tested seropositive for H. pylori organism (40%): 430 (12.2%) were both IgG and IgA positive, 212 (6%) and 771 (21.7%) cases showed isolated positivity for IgG or IgA, respectively. Male gender, older age, lower levels of socioeconomic status (SES), and family members >10 were significantly associated with H. pylori seropositivity. The proportion of participants with short stature was significantly more in the H. pylori seropositive group than the seronegative group (OR1.249, confidence interval [1.020–1.531], P = 0.033). There was no significant association between H. pylori seropositivity and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity among apparently healthy Saudi children (40%) is intermediate compared with that in developed and developing countries. The Saudi pediatric population shows a predominant IgA-type immunological response to H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Helicobacter pylori, prevalence, Riyadh, short stature, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection vary from country to country depending on socioeconomic status (SES) and development stage. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is approximately 50% worldwide and is as high as 80–90% in developing countries.[1] The cumulative life-time risk of developing a peptic ulcer is 10% to 15% and 0.5% to 1% risk of developing gastric carcinoma (GC).[2] Acquisition of the infection occurs mostly in early childhood;[3] therefore, a better understanding of the epidemiology and the risk factors associated with H. pylori infection in the pediatric population is important in clarifying the natural history and complications of the infection, and programming eradication strategies.

The prevalence rate of H. pylori in Saudi Arabia was reported to be in the range of 50–80% among symptomatic patients with dyspepsia, abdominal pain or in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] The available information on H. pylori prevalence among apparently healthy populations across Saudi Arabia is vastly inadequate. Few “community”-based studies were conducted in the healthy Saudi population from the different regions of the country and most of these studies were among adults,[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] reporting a prevalence rate that ranged between 23 and 67%. The single study from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, was conducted in 1989 and included 134 children only.[11] These studies suffered from several major limitations related to small sample size, nonrandom selection of the study population, and inappropriate study settings. These limitations led to significant selection bias and inadequately powered studies that affected the precision of the results and made these studies nonrepresentative of the general Saudi population.

These facts prompted us to design a large population -based study to determine the prevalence rate of H. pylori seropositivity among apparently healthy Saudi pediatric population via serologic screening of a large randomly selected study sample of school-aged children in Riyadh city. In addition, we aimed to study some aspects of H. pylori infection during childhood that were not investigated before in Saudi Arabia, like the influence of H. pylori infection on growth and the utility of the combined use of anti-H. pylori IgA and anti-H. pylori IgG antibodies (Abs) in screening for H. pylori infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional population-based study to screen apparently healthy school aged Saudi children (aged 6–15 years) of both sexes, attending primary and intermediate schools in Riyadh between 2014 and 2016, for H. pylori seropositivity by checking for the presence of anti-H. pylori IgG and IgA Abs in serum specimens. Riyadh is a new and well developed city that, in less than 5 decades, expanded from a population of 5,000 to almost 5 million people with Saudis constituting 75% of the population. The Saudi community is tribal but belong to Arab ethnicity. Saudi Arabia has shown significant industrial and educational development over the past decades. Riyadh is the most representative city of all Saudi population because of its high rate of immigration from different parts of the country which make its inhabitants share similar demographic and sociocultural lifestyles, and dietary characteristics with those of whole population of Saudi Arabia.

Study population

The details of the methodology of the celiac mass screening study, from which the study population for the present study was selected, has been described elsewhere.[19] In brief, a total of 104 schools (61 primary schools and 43 intermediate schools; 53 male schools and 51 female schools) were randomly selected from the five “administrative” geographic regions of Riyadh city (North, South, East, West, and Center) using probability proportionate sampling procedure. Parents of 7930 students (mean age 11.22 ± 2.62 years) signed the informed consents and accepted to participate in the mass screening study. The 5 mL blood specimen collected from each student was centrifuged at 2000 RPM for 10 minutes and plasma was separated, given a code number from 1 to 7930, and stored at -80°C until analysis. Out of the 7930 serum specimens, we selected the odd-numbered specimens for H. pylori serology testing.

Study procedures

Data collection

A health advocator in each school distributed envelopes to all students. Each envelop contained the following: 1) an informed consent form, and 2) a questionnaire to collect data on demographics, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, and SES. All students whose parents signed the informed consent underwent measurement of growth parameters prior to blood collection. The SES of students was measured by collecting data on four main indicators: parents' educational level, family income, habitation, and parents' jobs. We used a point scale of 1–20 as follows: educational level, 6 points; family income monthly, 6 points; type of residence, 4 points; type of work, 4 points. An overall score of ≤5 from a maximum of 20 defined the low SES, 6–10 as lower middle SES, and 11–15 as higher middle SES, and >15 as high SES. Participants were categorized into six educational levels: postgraduate degree (6 points), university graduate (5 points), high school graduate (4 points), intermediate school graduate (3 points), primary school graduate (2 points), and illiterate (1 point). Monthly family income was graded as follows: US $ >8000 (6 points), US $ 5000 - 8000 (5 points), US $ 2500 - 5000 (4 points), US $ 1500 - 2500 (3 points), US $ <1500 (2 points), and no income (1 point). The habitation was categorized into four types: Palace (4 points), Villa (3 points), apartment (2 points), small traditional house (1 point). Occupation of parents was classified as: trader/businessman/professional (4 points), office clerk (3 points), worker (2 points), and unemployed (1 point).

Serology evaluation

The serum specimens were analyzed for the presence of anti-H. pylori IgG and IgA antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This method has been validated and extensively used in research on H. pylori infection in children.[20,21] The ELISA test used was QUANTA Lite H. pylori IgA and the QUANTA Lite H. pylori IgG kit (Inova Diagnostics, Inc., USA) with a sensitivity and specificity of over 90%. The cutoff value for positive IgA or IgG antibody to H. pylori was set at ≥25 units, negative at ≤20 units, and equivocal if the value ranges between 20.1 and 24.9 units. If the value remained equivocal after repeat testing, the result was reported as equivocal. A specimen with positive H. pylori IgA and/or IgG was reported as positive for H. pylori infection. A negative result indicated no IgA or IgG antibodies to H. pylori.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the institutional review board (number 11-066) and the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia. All study participants, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables, such as gender, region, SES, and other variables are presented in frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables such as age, weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). Independent sample t-test was used to test mean significant differences between positive and negative H. pylori group with study characteristics. Chi-square/Fisher's exact test was used when the cell expected frequency was less than five and was applied to determine the significant relationship between categorical variables. A binary logistic regression was used to ascertain the most important significant risk factors/predictors between positive and negative H. pylori patients. A P–value <0.05 two-tailed was considered as statistically significant. All data was analyzed through statistical package SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

General characteristics of the study cohort

We used a representative sample of 3965 serum specimens from an existing population-based biorepository of archived 7930 serum samples. Among these, 3953 were suitable for serology testing and 12 samples were inadequate. Out of the 3953 samples, 402 showed equivocal results (36 were equivocal for both IgG/IgA H. pylori, 296 equivocal for IgA-H. pylori only, and 70 equivocal for IgG-H. pylori only) and were excluded from the analysis. Thus, a total of 3551 samples showed seropositive or seronegative results and constituted our study cohort [11.25 ± 2.5 years; females = 1834 (51.6%) and males = 1717 (48.4%]. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the 3551 participants including their demographics, distribution among the five geographic regions of Riyadh, distribution among the 4 levels of SES, number of family members, frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms, and age groups.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population (n=3551)

| Variable | Study cohort (total number=3551) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender F:M† | 1834 (51.6%)/1717 (48.4%) | |

| Age (Mean±SD) | 11.25±2.589 | |

| Region | ||

| Center | 421 (11.9%) | |

| East | 1108 (31.2%) | |

| North | 738 (20.8%) | |

| South | 464 (13.1%) | |

| West | 794 (22.4%) | |

| Unknown | 26 (0.7%) | |

| Symptoms | ||

| Poor appetite | 752 (21.2%) | |

| Abdominal distension | 278 (7.8%) | |

| Diarrhea | 220 (6.2%) | |

| Constipation | 350 (9.9%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 877 (24.7%) | |

| Vomiting | 193 (5.4%) | |

| Socioeconomic class | ||

| Low socioeconomic status | 279 (7.9%) | |

| Lower middle socioeconomic status | 1320 (37.2%) | |

| Higher middle socioeconomic status | 1604 (45.2%) | |

| Higher socioeconomic status | 348 (9.8%) | |

| Socioeconomic indicators | ||

| Father's Education | ||

| Unknown | 52 (1.5%) | |

| Illiterate | 231 (6.5%) | |

| Primary | 499 (14.1%) | |

| Intermediate | 543 (15.3%) | |

| High school | 1071 (30.2%) | |

| Bachelor | 916 (25.8%) | |

| Doctorate/Master | 239 (6.7%) | |

| Mother's Education | ||

| Unknown | 59 (1.7%) | |

| Illiterate | 428 (12.1%) | |

| Primary | 567 (16.0%) | |

| Intermediate | 564 (15.9%) | |

| High school | 911 (25.7%) | |

| Bachelor | 972 (27.4%) | |

| Doctorate/Master | 50 (1.4%) | |

| Family income ($) | ||

| Unknown | 160 (4.5%) | |

| No income | 181 (5.1%) | |

| <1,500 | 611 (17.2%) | |

| 1,500-2,500 | 1037 (29.2%) | |

| 2,500-5,000 | 1067 (30.0%) | |

| 5,000-8,000 | 327 (9.2%) | |

| >8,000 | 168 (4.7%) | |

| Type of residence | ||

| Unknown | 56 (1.6%) | |

| Traditional house | 430 (12.1%) | |

| Apartment | 1153 (32.5%) | |

| Villa | 1891 (53.3%) | |

| Palace | 21 (0.6%) | |

| Number of family members | ||

| ≤5 | 887 (25.0%) | |

| 6-10 | 2282 (64.3%) | |

| ≥11 | 382 (10.8%) | |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| 6 yrs | 89 (2.5%) | |

| 7 yrs | 202 (5.7%) | |

| 8 yrs | 330 (9.3%) | |

| 9 yrs | 364 (10.3%) | |

| 10 yrs | 418 (11.8%) | |

| 11 yrs | 454 (12.8%) | |

| 12 yrs | 470 (13.2%) | |

| 13 yrs | 414 (11.7%) | |

| 14 yrs | 413 (11.6%) | |

| 15 yrs | 397 (11.1%) | |

| H. Pylori serology results | ||

| IgG positive and IgA negative | 122 | |

| IgG positive and IgA weakly positive | 90 | |

| IgG negative and IgA positive | 645 | 35% |

| Both IgG + IgA positive | 430 | |

| IgA positive and IgG weak positive | 126 | |

| IgG weak positive | 70 | |

| IgA weak positive | 306 | 10.4% |

| Both IgA + IgG weak positive | 36 | |

| Both IgA + IgG negative | 2138 (54%) |

†M=male, F=female

Seroprevalence of H. pylori infection

The overall seropositivity of H. pylori in this cohort was 40% (1413 H. pylori +ve specimens): 212 samples (6%) were anti-H. pylori IgG+/IgA–, 771 (21.7%) were H. pylori IgG–/IgA+, and 430 (12.2%) were both IgG+/IgA+. The overall H. pylori IgG +ve was 18.2%. The uninfected participants (n = 2138) constituted the control group. In the H. pylori IgG+/IgA+ group, the titer of H. pylori IgA was significantly higher than the titer of IgG Abs across all age groups except at age 10 years [Supplementary Table 1]. The mean level of IgA-Abs titer in the H. pylori IgG+/IgA+ group was 53.96 ± 36.24 units versus a titer of 43.10 ± 23.07 units of IgG-Abs in the isolated H. pylori IgA+ group. Comparison of the two isolated H. pylori positive groups (Isolated IgG+ versus isolated IgA+) [Supplementary Table 2] revealed no gender difference but significantly younger age of the isolated IgA+ group. Although the IgG and IgA Abs were detected in all ages, the rate of IgA seropositivity was significantly greater at ages 8 and 9 years, while the IgG seropositivity was significantly greater at age 14 years.

Supplementary Table 1.

Mean level of H. pylori IgG and IgA titer according to age in the 430 positive H. pylori cases with combined positivity of IgG and IgA

| Age | Mean level of IgG titer±SD | Mean level of IgA titer±SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 yr, n (%) | 31.43±5.1 | 50.52±21.99 | <0.001 |

| 7 yr, n (%) | 42.14±12.34 | 47.47±19.59 | <0.001 |

| 8 yr, n (%) | 41.52±17.36 | 57.63±41.14 | <0.001 |

| 9 yr, n (%) | 36.36±11.16 | 55.91±32.52 | <0.001 |

| 10 yr, n (%) | 41.32±19.62 | 47.96±27.94 | <0.001 |

| 11 yr, n (%) | 49.29±22.11 | 45.53±26.51 | 0.024 |

| 12 yr, n (%) | 44.86±17.12 | 50.32±33.9 | 0.003 |

| 13 yr, n (%) | 42.57±16.2 | 53.7±29.88 | <0.001 |

| 14 yr, n (%) | 45.47±18.89 | 57.54±43.45 | <0.001 |

| 15 yr, n (%) | 46.95±20.64 | 61.1±48.12 | <0.001 |

Supplementary Table 2.

Comparison of the rate of isolated IgG-H. pylori positivity versus isolated IgA-H. pylori positivity across age groups

| Variable | Isolated IgG H. pylori positive (n=212) | Isolated IgA H. pylori positive (n=771) | OR 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen der F: M | 105 (49.5%)/107 (50.5%) | 374 (48.5%)/397 (51.5%) | 0.960 [0.708-1.301] | 0.792 | ||

| Age (Mean±SD) | 11.87±2.34 | 11.28±2.54 | 0.910 [0.855-0.968] | 0.002 | ||

| 6 yr, n (%) | 4 | (1.9%) | 9 | (1.2%) | 1.63 [0.496-5.34] | 0.417 |

| 7 yr, n (%) | 7 | (3.3%) | 47 | (6.1%) | 0.53 [0.234-1.181] | 0.114 |

| 8 yr, n (%) | 8 | (3.8%) | 72 | (9.3%) | 0.38 [0.18-0.803] | 0.009 |

| 9 yr, n (%) | 15 | (7.1%) | 85 | (11.0%) | 0.61 [0.347-1.088] | 0.092 |

| 10 yr, n (%) | 19 | (9.0%) | 93 | (12.1%) | 0.72 [0.427-1.206] | 0.208 |

| 11 yr, n (%) | 36 | (17.0%) | 102 | (13.2%) | 1.34 [0.886-2.031] | 0.164 |

| 12 yr, n (%) | 36 | (17.0%) | 98 | (12.7%) | 1.4 [0.926-2.13] | 0.109 |

| 13 yr, n (%) | 25 | (11.8%) | 86 | (11.2%) | 1.06 [0.663-1.71] | 0.795 |

| 14 yr, n (%) | 37 | (17.5%) | 89 | (11.5%) | 1.62 [1.067-2.46] | 0.023 |

| 15 yr, n (%) | 25 | (11.8%) | 90 | (11.7%) | 1.01 [0.631-1.621] | 0.962 |

Risk factors for H. pylori seropositivity

The grades of the socioeconomic status of the total study cohort (n = 3551) in each region in Riyadh city are shown in Table 2. The low and lower middle SES predominated in the center and south of Riyadh (85.7% and 60%, respectively) as compared to the east and north of Riyadh (40% and 17.5%, respectively) [P value <0.001]. This pattern of distribution was also maintained among the 1413 H. pylori positive cases [Table 3].

Table 2.

Stratification of the socioeconomic status by the region in the study cohort (n=3551)

| Socioeconomic status | Study cohort (n=3551)† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center (n=421) | South (n=464) | West (n=794) | East (n=1108) | North (n=738) | P | |

| Low socioeconomic status (n, %) | 112 (26.6%) | 59 (12.7%) | 57 (7.2%) | 43 (3.9%) | 7 (0.9%) | <0.001 |

| Lower middle socioeconomic status (n, %) | 249 (59.1%) | 217 (46.8%) | 343 (43.3%) | 377 (34%) | 123 (16.7%) | <0.001 |

| Higher middle socioeconomic status (n, %) | 55 (13.1%) | 171 (36.9%) | 369 (46.5%) | 552 (49.8%) | 444 (60.2%) | <0.001 |

| Higher socioeconomic status (n, %) | 5 (1.2%) | 17 (3.7%) | 24 (3.0%) | 136 (12.3%) | 164 (22.2%) | <0.001 |

†26 Participants had unknown region

Table 3.

Stratification of the socioeconomic status by the region in the H. pylori positive cases (n=1413)

| Socioeconomic status |

H. pylori positive cases (n=1413)† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center (n=224) | South (n=225) | West (n=309) | North (n=245) | East (n=399) | P | |

| Low socioeconomic status (n, %) | 63 (28.1%) | 30 (13.3%) | 25 (8.1%) | 2 (0.8%) | 24 (6.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Lower middle socioeconomic status (n, %) | 136 (60.7%) | 113 (50.2%) | 147 (47.6%) | 56 (22.9%) | 139 (34.8%) | <0.001 |

| Higher middle socioeconomic status (n, %) | 24 (10.7%) | 76 (33.8%) | 132 (42.7%) | 141 (57.6%) | 190 (47.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Higher socioeconomic status (n, %) | 1 (0.4%) | 6 (2.7%) | 5 (1.6%) | 46 (18.8%) | 46 (11.5%) | < 0.001 |

†26 Participants had unknown region

Table 4 shows the comparison of the H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative groups. No significant association was observed between gastrointestinal symptoms and seropositivity status. Male gender, older age, central and southern regions of Riyadh, lower levels of SES, and family members >10 were significantly associated with H. pylori seropositivity. Subanalysis of the SES indicators revealed that parents with educational level below high school, monthly family income US $ <2500, living in traditional house with limited space were risk factors for H. pylori seropositivity, while participants with higher income, higher education levels had significantly lower likelihood of having H. pylori seropositivity.

Table 4.

Comparison of the H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative groups

| Variable | H. pylori positive (n=1415) | H. pylori Negative (n=2138) | OR [95% C.I] | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender F:M† | 682 (48.3%)/731 (51.7%) | 1152 (53.9%)/986 (46.1%) | 1.252 [1.095-1.433] | 0.001 |

| Age (Mean±SD) | 11.70 2.56 | 10.96 2.56 | 0.894 [0.870-0.918] | < 0.001 |

| Region | ||||

| Center | 224 (15.9%) | 197 (9.2%) | 1.86 [1.513-2.278] | < 0.001 |

| East | 399 (28.2%) | 709 (33.2%) | 0.79 [0.685-0.918] | 0.002 |

| North | 245 (17.3%) | 493 (23.1%) | 0.7 [0.59-0.83] | < 0.001 |

| South | 225 (15.9%) | 239 (11.2%) | 1.5 [1.237-1.831] | <0.001 |

| West | 309 (21.9%) | 484 (22.6%) | 0.96 [0.814-1.124] | 0.575 |

| Unknown | 11 (0.8%) | 1.11 [0.509-2.425] | 0.795 | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Poor appetite | 284 (20.1%) | 468 (21.9%) | 0.9 [0.761-1.059] | 0.194 |

| Abdominal distension | 108 (7.6%) | 170 (8.0%) | 0.96 [0.745-1.232] | 0.721 |

| Diarrhea | 97 (6.9%) | 123 (5.8%) | 1.21 [0.917-1.59] | 0.182 |

| Constipation | 128 (9.1%) | 222 (10.4%) | 0.86 [0.684-1.081] | 0.190 |

| Abdominal pain | 340 (24.1%) | 537 (25.1%) | 0.94 [0.808-1.105] | 0.461 |

| Vomiting | 76 (5.4%) | 117 (5.5%) | 0.98 [0.73-1.321] | 0.896 |

| Socioeconomic class | ||||

| Low socioeconomic status | 145 (10.3%) | 134 (6.3%) | 1.71 [1.338-2.185] | 0.001 |

| Lower middle socioeconomic status | 598 (42.3%) | 722 (33.7%) | 1.44 [1.253-1.653] | <0.001 |

| Higher middle socioeconomic status | 564 (39.9%) | 1040 (48.6%) | 0.7 [0.612-0.804] | < 0.001 |

| Higher socioeconomic status | 106 (7.5%) | 242 (11.3%) | 0.64 [0.5-0.807] | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic indicators | ||||

| Education level (both parents) | ||||

| Empty | 14 (1.0%) | 16 (0.7%) | 1.33 [0.646-2.728] | 0.442 |

| Illiterate | 85 (6.0%) | 72 (3.4%) | 1.84 [1.332-2.533] | <0.001 |

| Primary | 197 (13.9%) | 174 (8.1%) | 1.83 [1.473-2.27] | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 214 (15.1%) | 264 (12.3%) | 1.27 [1.043-1.539] | 0.018 |

| High school | 399 (28.2%) | 583 (27.3%) | 1.05 [0.903-1.219] | 0.544 |

| Bachelor | 410 (29.0%) | 857 (40.1%) | 0.61 [0.529-0.706] | <0.001 |

| Doctorate/Master | 94 (6.7%) | 172 (8.0%) | 0.81 [0.628-1.057] | 0.120 |

| Family income ($) | ||||

| Empty | 57 (4.0%) | 103 (4.8%) | 0.83 [0.597-1.156] | 0.267 |

| No income | 84 (5.9%) | 97 (4.5%) | 1.33 [0.985-1.796] | 0.063 |

| <1500 | 293 (20.7%) | 318 (14.9%) | 1.5 [1.256-1.784] | <0.001 |

| 1500-2500 | 452 (32.0%) | 585 (27.4%) | 1.25 [1.078-1.446] | 0.003 |

| 2500-5000 | 354 (25.1%) | 713 (33.3%) | 0.67 [0.575-0.776] | <0.001 |

| 5000-8000 | 114 (8.1%) | 213 (10.0%) | 0.79 [0.625-1.006] | 0.054 |

| >8000 | 59 (4.2%) | 109 (5.1%) | 0.81 [0.587-1.122] | 0.202 |

| Residential | ||||

| Empty | 27 (1.9%) | 29 (1.4%) | 1.42 [0.835-2.403] | 0.196 |

| Traditional small house | 234 (16.6%) | 196 (9.2%) | 1.97 [1.605-2.409] | <0.001 |

| Apartment | 461 (32.6%) | 692 (32.4%) | 1.01 [0.877-1.168] | 0.894 |

| Villa | 684 (48.4%) | 1207 (56.5%) | 0.72 [0.632-0.828] | <0.001 |

| Palace | 7 (0.5%) | 14 (0.7%) | 0.76 [0.304-1.876] | 0.542 |

| Number of family members | ||||

| ≤5 | 323 (22.9%) | 564 (26.4%) | 0.83 [0.707-0.968] | 0.017 |

| 6-10 | 899 (63.6%) | 1383 (64.7%) | 0.95 [0.83-1.098] | 0.483 |

| ≥11 | 191 (13.5%) | 191 (8.9%) | 1.59 [1.288-1.971] | <0.001 |

| Growth parameters | ||||

| Weight <3rd percentiles (Underweight) % | 172 (12.2%) | 258 (12.1%) | 1.010 [0.822-1.241] | 0.937 |

| Height <3rd percentile (short stature) % | 192 (13.6%) | 239 (11.2%) | 1.249 [1.020-1.531] | 0.033* |

| BMI <3rd percentile (%) | 171 (12.1%) | 244 (11.4%) | 1.069 [0.868-1.316] | 0.557 |

| Weight Z-score (Mean±S.D) | -0.165±1.500 | -0.135±1.448 | 0.954 [0.822-1.108] | 0.537 |

| BMI Z-score (Mean±S.D) | -0.0182±1.77 | -0.0186±1.694 | 1.074 [0.975-1.183] | 0.148 |

| Height Z-score (Mean±S.D) | -0.484±1.300 | -0.410±1.278 | 1.027 [0.924-1.141] | 0.622 |

| Age (yrs) | ||||

| ≤6 yrs | 19 (1.3%) | 70 (3.3%) | 0.4 [0.241-0.672] | < 0.001 |

| 7 yrs | 59 (4.2%) | 143 (6.7%) | 0.61 [0.445-0.83] | 0.002 |

| 8 yrs | 104 (7.4%) | 226 (10.6%) | 0.67 [0.527-0.857] | 0.448 |

| 9 yrs | 132 (9.3%) | 232 (10.9%) | 0.85 [0.676-1.06] | 0.143 |

| 10 yrs | 153 (10.8%) | 265 (12.4%) | 0.86 [0.695-1.06] | 0.152 |

| 11 yrs | 181 (12.8%) | 273 (12.8%) | 1.0 [0.821-1.227] | 0.984 |

| 12 yrs | 201 (14.2%) | 269 (12.6%) | 1.15 [0.947-1.402] | 0.162 |

| 13 yrs | 164 (11.6%) | 250 (11.7%) | 0.99 [0.804-1.223] | 0.925 |

| 14 yrs | 186 (13.2%) | 227 (10.6%) | 1.28 [1.038-1.569] | 0.021 |

| >15 yrs | 214 (15.2%) | 183 (8.5%) | 1.91 [1.546-2.352] | < 0.001 |

M=male; F=female; *After controlling for sociodemographic status, we did not find significant differences in the H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative groups (P=0.151, OR [95% CI] = 1.162 [0.946-1.428])

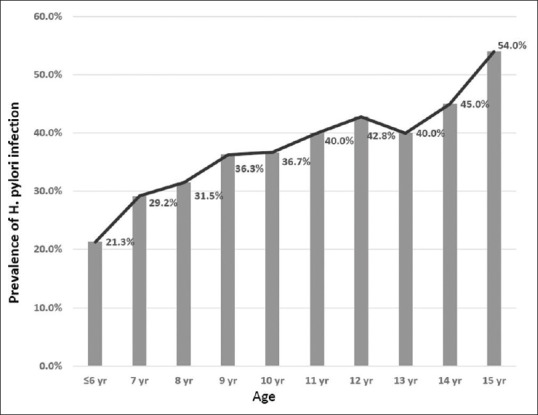

Table 5 shows the distribution of the 1413 H. pylori positive individuals stratified according to the geographic area in Riyadh, SES, and age of participants. The H. pylori positivity was significantly higher in the central region of Riyadh (53.2%) where the majority of the residents belong to a low or lower middle SES (85.7%) [Table 2], followed by the Southern region. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence was significantly affected by SES; the highest seroprevalence (52%) was observed among participants from the low SES and was lowest (30.5%) among high SES participants. Multiple regression analysis revealed that lower family income US $ <2,500; 1.5 [1.256–1.784] P < 0.001) and low educational level below intermediate school [OR = 1.83, P < 0.001] were the two most important contributing factors to seropositivity of H. pylori organism. By age, H. pylori positivity increased in a nearly linear fashion from 21% at age 6 years to 54% at 15 years of age [Figure 1] and the average increase per year was 3.3%. This linear increasing pattern of distribution was also maintained among the 642 H. pylori IgG positive cases when the prevalence of H. pylori increased from 11.2% at age 6 years to 31.2% at 15 years of age.

Table 5.

Effect of region, socioeconomic class, age, and number of family members on distribution of H. pylori positive cases among Saudi Children (6-15 years)

| Variable | Study cohort | H. pylori positive | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| number % | ||||

| 3551 | 1413 | 40% | ||

| Region | ||||

| Center | 421 | 224 | 53.2% | <0.001 |

| South | 464 | 225 | 48.5% | 0.058 |

| West | 794 | 309 | 39% | 0.707 |

| East | 1108 | 399 | 30.5% | 0.040 |

| North | 738 | 245 | 33.2% | 0.006 |

| Socioeconomic class | ||||

| Low socioeconomic status | 279 | 145 | 52% | 0.006 |

| Lower middle socioeconomic status | 1320 | 598 | 45.3% | 0.001 |

| Higher middle socioeconomic status | 1604 | 564 | 35.2% | 0.001 |

| Higher socioeconomic status | 348 | 106 | 30.5% | 0.011 |

| Age group | ||||

| ≤ 6 yrs | 89 | 19 | 21.3% | 0.011 |

| 7 yrs | 202 | 59 | 29.2% | 0.031 |

| 8 yrs | 330 | 104 | 31.5% | 0.030 |

| 9 yrs | 364 | 132 | 36.3% | 0.335 |

| 10 yrs | 418 | 153 | 36.7% | 0.347 |

| 11 yrs | 454 | 181 | 40% | 0.981 |

| 12 yrs | 470 | 201 | 42.8% | 0.358 |

| 13 yrs | 414 | 164 | 40% | 0.959 |

| 14 yrs | 413 | 186 | 45% | 0.135 |

| >15 yrs | 397 | 214 | 54% | <0.001 |

| Number of family members | ||||

| ≤5 | 887 | 323 | 36.4% | 0.116 |

| 6-10 | 2282 | 899 | 39.4% | 0.671 |

| ≥11 | 382 | 191 | 50% | 0.006 |

Figure 1.

H. pylori positivity among the total study participants (=3551) according to age

Impact of H. pylori seropositivity on growth

The proportion of participants with short stature was significantly more in the H. pylori seropositive group than the seronegative group (13.6% versus 11.2%, OR 1.249, CI [1.020–1.531], P = 0.033). After controlling for SES, we did not find significant differences in the H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative groups (P value = 0.151, OR [95% CI] = 1.162 [0.946 – 1.428]). The frequency of underweight (<3rd percentile), BMI (<3rd percentile), and the mean weight, height, and BMI for age z-scores were not different between the infected and uninfected groups.

DISCUSSION

Our study is important for two main reasons: (a) the sample size was very wide and the study was properly designed allowing a more precise estimate of H. pylori seroprevalence, and (b) it provides further insight on the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, an area that has shown significant modernization over the past few decades. We report several important findings. The sero-prevalence of H. pylori among apparently healthy Saudi children (40%) demonstrated here, using both IGA and IgG serology tests, is intermediate compared with that in developed (<30%) and developing countries (>50%).[22,23,24] Considering only the H. pylori IgG Abs testing, which was the only serology method used in the previous seroepidemiology studies in Saudi Arabia, the seroprevalence of H. pylori organism among apparently healthy Saudi children has dropped significantly from 40 - 50% in 1989 to 18.2% in the present study which is relatively a low rate compared with developing countries.[11] Another important and unique finding was the large percentage of H. pylori infected apparently healthy Saudi children (54% of the total 1413 cases) who have shown isolated IgA-immune response against H. pylori organism as compared to 0–7% in different ethnicities.[22,25,26,27,28]

Our study confirms and extends evidence obtained from several studies worldwide that H. pylori is strongly associated with lower SES, measured as a lower family income, lower educational level, and poor housing leading to poor living conditions and sanitation, and crowding of family members.[23] Furthermore, the H. pylori infection rate varies in Riyadh city based on the region studied, the Central and Southern regions with the highest proportion of lower SES had significantly the highest rates of H. pylori seropositivity (48–53%) as compared to the north and east regions (30–33%) where higher levels of SES predominate (P < 0.001). The epidemiology of H. pylori has been changing over the last decades in many countries with a decline in the prevalence of the infection in parallel to improvement in SES.[23] The drop of H. pylori infection seroprevalence rate among healthy Saudi children to an intermediate range between developed and developing countries is mainly attributed to a combination of various factors including rapid economic growth, better education, improved housing and living conditions, and improved hygiene. Also, the widespread abuse of antibiotics to treat infectious during early childhood, when H. pylori infection is commonly acquired, could explain the decreasing H. pylori seropositivity levels in older children and adolescents. As Saudi Arabia is in a dynamic state of progression from a developing country into a developed country, it is anticipated that the pattern of prevalence of infection in Saudi Arabia will change further and each successive generation will experience a progressively lower rate of acquisition. It is important that preventive public health services be devoted to low SES communities via educational awareness campaigns, facilitating grant programs for wider housing with improved sanitation, and creating jobs for the poor jobless people to improve their income. Attainment of higher SES does not immediately change the epidemiology of H. pylori as it requires several generations for the pattern of acquisition of infection to change from that of a developing country to a developed industrialized country. Based on our data, in comparison to a seroepidemiology data from Riyadh in 1989, it took 30 years for the H. pylori-IgG seropositivity in children to drop from 40% to 18%. Therefore, it may be valuable to study the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection every 2–3 decades to monitor prevalence trends and re-evaluate risk factors for H. pylori infection. Despite the significant drop in H. pylori seroprevalence rate among Saudi children, we still reserve two characteristics of developing countries: 1) Majority of the infected children had acquired the H. pylori infection during early childhood (20% are H. pylori infected by age 6 years), and 2) rapid increase of prevalence of H. pylori infection in older children and adolescents (Average of 3% increase in prevalence rate/year from 20% at age 6 years to 40% at age 15 years). In contrast, in developed countries H. pylori infection is low in childhood and slowly increases with age at a rate of less than 0.5–1% a year.[23] Long-term follow-up studies suggest that the age-dependent increase of H. pylori seropositivity is mainly attributable to a birth cohort phenomenon and a constant rate of new infections at all ages especially during childhood and adolescence that level off by 40–50 years of age.[27,29,30,31,32] These results support our assumption that a remarkable drop in H. pylori infection among Saudi Adults will probably follow the presently identified drop of H. pylori in children.

Variation in the prevalence of H. pylori infection reported across the world depends to a great extent on the SES, developmental stage of the country, and age of the studied population; however it could to some extent reflect differences in methodology of the studies, particularly the diagnostic method used. Large epidemiological studies using methods that directly detect the pathogen (stool antigen or urea breath test) over prolonged time-periods are considered the gold standard; however, these studies are logistically difficult to conduct and expensive compared to seroprevalence studies, and thus very infrequently conducted. An obvious limitation of the serology tests is that a positive result only indicates previous immunological exposure to H. pylori but cannot distinguish an active from an inactive H. pylori infection. Also another limitation is that a positive test result only indicates the presence of antibody to H. pylori and does not necessarily indicate that gastrointestinal disease is present. It is therefore recommended that serology tests are not used for diagnosis of H. pylori infection in clinical practice.[33] However, these tests have the advantages of being easy to perform, inexpensive, and the results are not affected by use of antibiotics or proton pump inhibitor within 1 month of testing. Also, several studies using H. pylori serology test demonstrated sensitivities over 90% when compared to culture or histopathology-based studies.[21,22,23,26] These features made H. pylori serology test the most suited method for population-based H. pylori mass screening studies among healthy individuals, like our study. In a systematic review of the pediatric literature on population-based studies of the prevalence of H. pylori infection conducted during the period 2011–2016, the prevalence estimates from direct H. pylori detection studies and seroprevalence estimates in asymptomatic individuals did not differ significantly (30%–44% for direct detection versus 27%–38% for seroprevalence).[24] Also in the same systematic review, on analysis of the studies that tested for both seroprevalence and direct detection of infection in the same children, serology tended to find that about 10% of children had past infection and that about 10% of actively infected children were seronegative, indicating that serology results should be similar to those of direct detection methods, regardless of whether children were healthy or symptomatic. The authors concluded that the probability that overall seroprevalence represents true active H. pylori persistence rates in a large community appears to be high in childhood, considering the nearly 10% nonconcordance for both persistent and noninfected children. This may be a reflection of the observation that the majority of infections acquired early in childhood are persistent; follow-up data on H. pylori antibodies of same individuals showed that antibodies persisted in a great majority of those who had them 10–21 years earlier.[34,35] These data support that the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection reported in our study is very close to the true prevalence in the healthy Saudi pediatric population.

Majority of individuals infected with H. pylori produce a measurable systemic immune response, composed primarily of IgG Abs. Very few studies evaluated host immunological responses of IgA type against H. pylori. Data from these studies suggest that host immunological responses to H. pylori may vary in different populations; IgA-H. pylori Abs were usually detected in combination with elevated IgG antibodies in approximately two-thirds of infected subjects; however, isolated IgA response to H. pylori (negative IgG Abs) was detected in 2% of the population in Finland,[28]4.9% of the population in Serbia,[22] and 7% of the population in the United States,[26] but not detected in Burkina Faso and Sweden.[25,27] The finding of high proportion of isolated anti-H. pylori IgA Abs production in response to H. pylori infection (≈55% of all H. pylori positive cases) is an interesting and unique finding in the Saudi Arabian population; the mechanisms behind this phenomenon remain to be studied. Therefore, measurement of only IgG Abs in the previous local population-based studies might have missed some cases of H. pylori infection and subsequently underestimated the true prevalence in the pediatric Saudi population.

The causal link between H. pylori and GC is now well established and the incidence of GC is generally in direct proportion to the prevalence of H. pylori infection. Over the past 2 decades, the age standardized incidence rate for GC among Saudis dropped from 3.7/100,000 population in 1994 to 2.1/100,000 population in 2014,[36] in parallel to the decline in H. pylori prevalence by 50% among Saudi children, as shown in the present study during the same time period. Similarly, in Japan, China, Korea, and throughout Europe, there has been a progressive and rapid decline in the prevalence of H. pylori infection as well as a fall in GC incidence.[37,38,39,40,41,42] However, from the global perspective, a lower incidence of GC is found in Saudi Arabia than in East Asia, some European countries, and Middle East countries despite the high prevalence and early childhood acquisition of H. pylori infection in the Saudi population over the past few decades.[36] Does the predominant IgA-type immunological response to H. pylori infection in the Saudi population offer protection against progression to peptic ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis, and GC? Some researchers reported that IgA anti-H. pylori antibodies can play a protective role against progression to severe H. pylori gastritis and atrophy[43] which legitimizes our question and provide a scientific plausibility to speculate on the low incidence of GC in Saudi Arabia.

Our data is in agreement with results from large epidemiologic studies on H. pylori infection, showing lack of relationship between H. pylori infection and gastrointestinal symptoms, including recurrent abdominal pains.[33,44,45] This emphasizes that gastrointestinal symptoms are unreliable for suggesting H. pylori infection. As the prevalence of H. pylori infection among Saudi children is becoming lower, pediatricians and family physicians need to re-evaluate when to test for and whether to treat H. pylori. Also, our data showed no association between H. pylori infection and growth impairment. Conflicting data were reported on the association between H. pylori infection and short stature. Several observational studies demonstrated that H. pylori infection may be associated with diminished growth of children; however after controlling for SES, the association between H. pylori infection and height was attenuated and was no longer statistically significant,[46,47] suggesting that H. pylori might be an indicator of living in suboptimal healthy and nutritional conditions. While the most updated consensus guidelines from the European and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition recommend against diagnostic testing for H pylori infection when investigating causes of short stature,[33] a recent systematic review proposed a weak recommendation to test and treat H. pylori infection in children with diminished growth.[48] Whether H. pylori eradication can be beneficial to children's growth is unclear, and evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials is lacking.

There are several limitations which should be acknowledged in this study. First, the relationship between H. pylori infection and its risk factors in the cross-sectional study could not be proven conclusively. However, this is an unavoidable limitation in the cross-sectional design of any study. Our current study was not designed to assess several important factors like lifestyle, living conditions, and dietary habits of the participants and their families, and whether there was previous H. pylori treatment or family history of H. pylori infection, peptic ulcer disease, and GC.

In conclusion, the prevalence of H. pylori infection among apparently healthy Saudi children has dropped by 50% over the past 3 decades to lay in the intermediate range between developed and developing countries. The Saudi pediatric population shows a predominant IgA-type immunological response to H. pylori infection. Further research is needed to uncover the clinical implication of this unique phenomenon and its impact on the outcome of H. pylori infection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the research center in King Fahad Medical City for funding this work through a research Grant number 016-007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruce MG, Maaroos HI. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2008;13(Suppl 1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung J, Kuipers E, El-Serag H. Systematic review: The global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:938–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellicano R, Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Astegiano M, Saracco GM, Megraud F. A 2016 panorama of Helicobacter pylori infection: Key messages for clinicians. Panminerva Med. 2016;58:304–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satti MB, Twum-Danso K, al-Freihi HM, Ibrahim EM, al-Gindan Y, al-Quorain A, et al. Helicobacter pylori-associated upper gastrointestinal disease in Saudi Arabia: A pathologic evaluation of 298 endoscopic biopsies from 201 consecutive patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashed RS, Ayoola EA, Mofleh IA, Chowdhury MN, Mahmood K, Faleh FZ. Helicobacter pylori and dyspepsia in an Arab population. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan AR. An age- and gender-specific analysis of H. Pylori infection. Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18:6–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1998.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmood K, Chowdhury MN, Ayoola EA, Mofleh IA, Rashed RS, Faleh FZ. Helicobacter pylori; histological and cultural correlation in chronic gastritis. Trop Gastroenterol. 1991;12:188–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Mouzan MI, Abdullah AM, Al-Mofleh IA. Gastritis in Saudi Arab children. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:576–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marie MA. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in large series of patients in an urban area of Saudi Arabia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;52:226–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasosah M, Satti M, Shehzad A, Alsahafi A, Sukkar G, Alzaben A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Saudi children: A three-year prospective controlled study. Helicobacter. 2015;20:56–63. doi: 10.1111/hel.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Moagel MA, Evans DG, Abdulghani ME, Adam E, Evans DJ, Jr, Malaty HM, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter (formerly Campylobacter) pylori infection in Saudia Arabia, and comparison of those with and without upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:944–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Knawy BA, Ahmed ME, Mirdad S, ElMekki A, AlAmmari O. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection in Saudi Arabia. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:772–4. doi: 10.1155/2000/952965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan MA, Ghazi HO. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:114–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaber S. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in children with chronic disease in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2006;21:21–6. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.27740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Faleh FZ, Ali S, Aljebreen AM, Alhammad E, Abdo AA. Seroprevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori and viral hepatitis A among adolescents in three regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Is there any correlation? Helicobacter. 2010;15:532–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telmesani AM. Helicobacter pylori: Prevalence and relationship with abdominal pain in school children in Makkah City, western Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:100–3. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.45359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanafi MI, Mohamed AM. Helicobacter pylori infection: Seroprevalence and predictors among healthy individuals in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:40–5. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000427043.99834.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habib SH, Hegazi M, Murad H, Amir E, Halawa T, El-Deek B. Unique features and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection at the main children's intermediate school in Rabigh, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hussaini A, Troncone R, Khormi M, AlTuraiki M, Alkhamis W, Alrajhi M, et al. Mass screening for celiac disease among school-aged children: Toward exploring celiac iceberg in Saudi Arabia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:646–51. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourke B, Jones N, Sherman P. Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease in children. Ped Infect Dis J. 1996;15:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel P, Khulusi S, Mendall MA, Lloyd R, Jazrawi R, Maxwell JD, et al. Prospective screening of dyspeptic patients by Helicobacter pylori serology. Lancet. 1995;346:1315–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinic M, Tasic G, Stankovic-Dordevic D, Otasevic L, Tasic M, Karanikolic A. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgA and IgG antibodies in asymptomatic children in Serbia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:303307. doi: 10.1080/00365540601034741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Helicobacter. 2013;19(Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/hel.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrres BZ, Lucero Y, Lagomarcino AJ, Orellana-Manzano A, George S, Torres JP, et al. Review: Prevalence and dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection during childhood. Helicobacter. 2017;22:1–18. doi: 10.1111/hel.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cataldo F, Simporè J, Greco P, Ilboudo D, Musumeci S. Helicobacter pylori infection in Burkina Faso: An enigma within an enigma. Dig Liv Dis. 2004;36:589–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaskowski TD, Martins TB, Hill HR, Litwin CM. Immunoglobulin A antibodies to helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2999–3000. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2999-3000.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granstrom M, Tindberg Y, Blennow M. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori Infection in a Cohort of Children Monitored from 6 Months to 11 Years of Age. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:468–70. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.468-470.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosunen TU, Seppailai K, Sarna S, Sipponen P. Diagnostic value of decreasing IgG, IgA and IgM antibody titres after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1992;339:893–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90929-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsonnet J, Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Hargrett-Bean N, Tauxe RV. Symptoms and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of epidemiologists. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:41–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91782-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuipers EJ, Pena AS, van Kamp G, Uyterlinde AM, Pals G, Pels NF, et al. Seroconversion for Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:328–31. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91473-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Pollak PT, Best LM, Bezanson GS, Marrie T. Increasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with age: Continuous risk of infection in adults rather than cohort effect. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:434–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashorn M, Maki M, M.Hallstrom M, Uhari M, Akerblom HK, Viikari J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in Finnish children and adolescents. A serologic cross-sectional and follow-up study. Scand JGastroenterol. 1995;30:876–9. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, Bontems P, Cadranel S, Casswall T, et al. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:991–1003. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosunen TU, Aromaa A, Knekt P, Salomaa A, Rautelin H, Lohi P, et al. Helicobacter antibodies in 1973 and 1994 in the adult population of Vammala, Finland. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:29–34. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones DM, Eldridge J, Fox AJ, Sethi P, Whorwell PJ. Antibody to the gastric campylobacter-like organism ('Campylobacter pyloridis') – Clinical correlations and distribution in the normal population. J Med Microbiol. 1986;22:57–62. doi: 10.1099/00222615-22-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 15]. Available from: https://nhic.gov.sa/eServices/Pages/TumorRegistration.aspx .

- 37.Lee JH, Choi KD, Jung H-Y, Baik GH, Park JK, Kim SS, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Korea: A multicenter, nationwide study conducted in 2015 and 2016. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12463. doi: 10.1111/hel.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakayama Y, Lin Y, Hongo M, Hidaka H, Kikuchi S. Helicobacter pylori infection and its related factors in junior high school students in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12363. doi: 10.1111/hel.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagy P, Johansson S, Molloy-Bland M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China and the USA. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:8. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0091-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki H, Mori H. World trends for H. pylori eradication therapy and gastric cancer prevention strategy by H. pylori test-and-treat. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:354–61. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuda M, Asaka M, Kato M, Matsushima R, Fujimori K, Akino K, et al. Effect on Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy against gastric cancer in Japan. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12415. doi: 10.1111/hel.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts SE, Morrison-Rees S, Samuel DG, Thorne K, Akbari A, Williams JG. Review article: The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer across Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Thera. 2016;43:334–45. doi: 10.1111/apt.13474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Futagami S, Takahashi H, Norose Y, Kobayashi M. Systemic and local immune responses against Helicobacter pylori urease in patients with chronic gastritis: Distinct IgA and IgG productive sites. Gut. 1998;43:168–75. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spee LA, Madderom MB, Pijpers M, van Leeuwen Y, Berger MY. Association between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal symptoms in children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e651–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bode G, Brenner H, Adler G, Rothenbacher D. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: Evidence from a population-based study that social and familial factors play a major role but not Helicobacter pylori infection. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:417–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinonez JM, Chew F, Torres O, Bégué RE. Nutritional status of Helicobacter pylori infected children in Guatemala as compared with uninfected peers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:395–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sood MR, Joshi S, Akobeng AK, Mitchell J, Thomas AG. Growth in children with Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:1025–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.066803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dror G, Muhsen K. Helicobacter pylori infection and children's growth- an overview. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:48–59. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]